Flux Balance Analysis: A Beginner's Guide to Metabolic Modeling for Biomedical Research

This guide provides a comprehensive introduction to Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a cornerstone computational method in systems biology and metabolic engineering.

Flux Balance Analysis: A Beginner's Guide to Metabolic Modeling for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive introduction to Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a cornerstone computational method in systems biology and metabolic engineering. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, from the core constraints of mass balance and steady-state to the construction of genome-scale metabolic models. Readers will learn the step-by-step methodology for performing FBA, explore its diverse applications in predicting growth rates and identifying drug targets—with a focus on pathogens like *Mycobacterium tuberculosis*—and gain practical insights for troubleshooting and optimizing their models. The content also addresses the critical process of validating model predictions against experimental data and compares FBA with other modeling approaches, equipping beginners with the essential knowledge to apply FBA in biomedical and biotechnological research.

What is Flux Balance Analysis? Core Principles and Concepts for Beginners

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a mathematical computational method used for simulating the metabolism of cells or entire unicellular organisms. This constraint-based approach analyzes the flow of metabolites through metabolic networks, enabling researchers to predict physiological properties of biological systems without requiring extensive kinetic parameter data. By focusing on the steady-state assumption and employing linear programming optimization, FBA has become an indispensable tool in systems biology, bioprocess engineering, and drug discovery. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of FBA's fundamental principles, mathematical foundations, and practical implementations, serving as an essential resource for researchers entering the field of metabolic network analysis.

Flux Balance Analysis represents a cornerstone methodology in systems biology for studying biochemical networks, particularly genome-scale metabolic reconstructions [1]. These network reconstructions encapsulate all known metabolic reactions in an organism and the genes that encode each enzyme. FBA calculates the flow of metabolites through this metabolic network, enabling prediction of an organism's growth rate or the production rate of biotechnologically important metabolites [1]. The method has gained significant traction due to its ability to analyze large-scale networks without requiring difficult-to-measure kinetic parameters [1].

The historical development of FBA dates back to the early 1980s, with Papoutsakis demonstrating the construction of flux balance equations using metabolic maps. Watson subsequently introduced the concept of using linear programming with an objective function to solve for pathway fluxes. The first significant study was published by Fell and Small in 1986, who utilized FBA with elaborate objective functions to study constraints in fat synthesis [2]. Since these early developments, FBA has evolved to become a widely adopted approach for analyzing genome-scale metabolic models, with reconstructions now available for numerous organisms [1].

Compared to traditional modeling approaches based on biophysical equations requiring extensive kinetic parameters, FBA differentiates itself through its constraint-based framework [1]. This fundamental difference allows researchers to simulate metabolic behaviors quickly and efficiently, even for large networks with thousands of reactions. The computational efficiency of FBA enables high-throughput simulations of various genetic and environmental perturbations, making it particularly valuable for exploratory research and hypothesis generation.

Mathematical Foundations

Stoichiometric Matrix Representation

The core mathematical representation in FBA is the stoichiometric matrix (S), which tabulates the stoichiometric coefficients of each metabolic reaction [1]. This m×n matrix, where m represents the number of metabolites and n the number of reactions, systematically encodes the network structure [1]. Each column corresponds to a biochemical reaction, while each row represents a unique metabolite. The entries in each column are the stoichiometric coefficients of the metabolites participating in that reaction, with negative coefficients indicating consumed metabolites and positive coefficients indicating produced metabolites [1].

The mathematical representation of metabolism creates a system of mass balance equations at steady state, expressed as:

Sv = 0

where v is the vector of reaction fluxes (length n), and the steady-state condition (dx/dt = 0) ensures that metabolite concentrations (x) remain constant over time [1] [2]. This equation forms the fundamental constraint in FBA, ensuring that for each metabolite, the total production flux equals the total consumption flux.

Constraints and Solution Space

The stoichiometric balances impose flux constraints on the system, ensuring that the total amount of any compound produced equals the total amount consumed at steady state [1]. In realistic large-scale metabolic models, the number of reactions typically exceeds the number of compounds (n > m), creating an underdetermined system with no unique solution [1]. Additional constraints are represented as inequalities that impose bounds on reaction fluxes:

lowerbound ≤ v ≤ upperbound

These bounds define the maximum and minimum allowable fluxes for each reaction, incorporating physiological limitations [1] [2]. The combination of stoichiometric balances and flux bounds defines the solution space of all possible metabolic flux distributions that satisfy the constraints.

Table 1: Types of Constraints in Flux Balance Analysis

| Constraint Type | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Balance | Sv = 0 | Metabolic intermediates do not accumulate at steady state |

| Capacity Constraints | vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax | Thermodynamic and enzyme capacity limitations |

| Environmental Constraints | vuptake ≤ maximumuptake | Nutrient availability in growth environment |

| Thermodynamic Constraints | vi ≥ 0 or vi ≤ 0 | Directionality of irreversible reactions |

Objective Functions and Linear Programming

To identify a single, meaningful flux distribution from the solution space, FBA introduces an objective function Z = câºv, which represents a linear combination of fluxes [1]. The vector c contains weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the biological objective. In practice, when maximizing a single reaction (such as biomass production), c is typically a vector of zeros with a one at the position of the reaction of interest [1].

The complete FBA problem can be formulated as a linear programming optimization:

maximize câºv subject to Sv = 0 and lowerbound ≤ v ≤ upperbound

This optimization identifies the flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes the objective function while satisfying all constraints [1] [2]. For microbial systems, the objective function is often set to maximize biomass production, simulating evolutionary pressure for growth optimization [1]. Other common objectives include maximizing ATP production or minimizing nutrient uptake.

Computational Implementation

Workflow and Algorithm

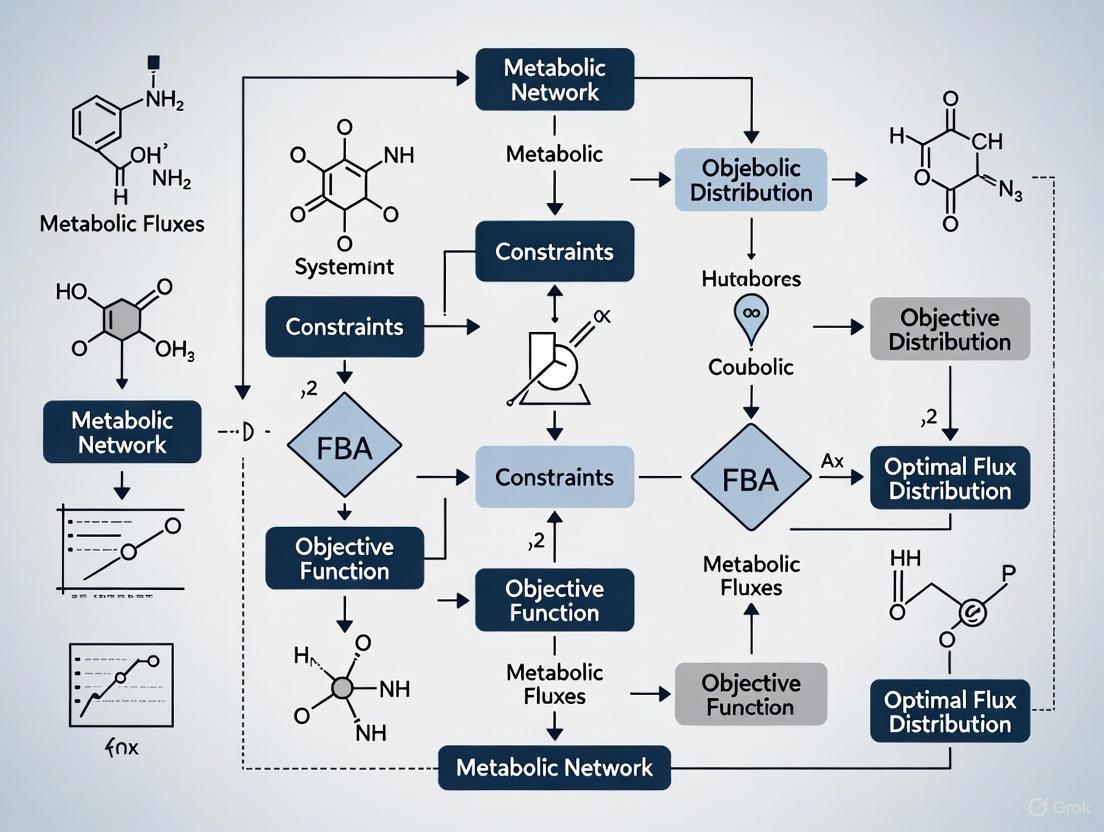

The implementation of FBA follows a systematic workflow that transforms biological knowledge into quantitative flux predictions. The diagram below illustrates this process:

The FBA process begins with genome annotation to identify metabolic genes, followed by network reconstruction to compile all known metabolic reactions [1]. The reconstruction is converted into a stoichiometric matrix, after which physiological constraints are applied to define the solution space [1]. The critical step of objective function definition determines the biological goal of the optimization, which is then solved using linear programming algorithms [2]. The resulting flux distribution must be validated experimentally to ensure biological relevance.

Essential Tools and Software

Several computational tools are available for implementing FBA. The COBRA (Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) Toolbox is a freely available MATLAB toolbox that can perform various FBA-based methods [1]. Models for the COBRA Toolbox are typically saved in Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) format, which has become a standard for model exchange [1]. Additional tools include the RAVEN Toolbox, which requires a linear optimization solver such as Gurobi for operation [3].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for FBA Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB suite for constraint-based modeling | http://systemsbiology.ucsd.edu/Downloads/Cobra_Toolbox [1] |

| SBML Format | Standard format for encoding metabolic models | http://sbml.org [1] |

| RAVEN Toolbox | MATLAB toolbox for genome-scale model reconstruction and simulation | https://sysbiochalmers.github.io/raven [3] |

| Gurobi Optimizer | Linear programming solver for large-scale optimization | Commercial license required [3] |

| KBase Platform | Web-based platform for FBA model import and analysis | https://www.kbase.us [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Predicting Aerobic and Anaerobic Growth in E. coli

A fundamental application of FBA involves predicting microbial growth under different environmental conditions. The following protocol demonstrates how to simulate E. coli growth in aerobic versus anaerobic conditions:

Model Loading: Import a genome-scale metabolic model of E. coli (e.g., the core E. coli model included in the COBRA Toolbox) using the

readCbModelfunction [1].Constraint Configuration:

- For aerobic growth: Set the maximum glucose uptake rate to a physiologically realistic level (e.g., 18.5 mmol glucose gDWâ»Â¹ hrâ»Â¹) using the

changeRxnBoundsfunction, while allowing unlimited oxygen uptake [1]. - For anaerobic growth: Constrain the maximum oxygen uptake rate to zero while maintaining the same glucose uptake constraint [1].

- For aerobic growth: Set the maximum glucose uptake rate to a physiologically realistic level (e.g., 18.5 mmol glucose gDWâ»Â¹ hrâ»Â¹) using the

Objective Definition: Set the objective function to maximize flux through the biomass reaction, which simulates growth optimization [1].

Optimization Execution: Perform FBA using the

optimizeCbModelfunction to calculate the optimal growth rate under each condition [1].

This protocol predicts an aerobic growth rate of 1.65 hrâ»Â¹ and an anaerobic growth rate of 0.47 hrâ»Â¹ for E. coli, values that align well with experimental measurements [1].

Calculating ATP Yield Per Glucose Consumed

FBA can quantify metabolic efficiency by calculating ATP yield from specific substrates. The following methodology demonstrates this application using Human-GEM, a genome-scale model of human metabolism:

Objective redefinition: Change the model objective from biomass production to maximizing flux through the ATP hydrolysis reaction (MAR03964 in Human-GEM), which represents ATP consumption, using the command:

ihuman = setParam(ihuman, 'obj', 'MAR03964', 1);[3].Media constraints: Prevent import of all metabolites except glucose, for which the maximum import flux is set to 1 (mmol/gDW/h) using exchange bounds:

ihuman = setExchangeBounds(ihuman, 'glucose', -1);[3].Anaerobic calculation: Perform FBA using

solveLP(ihuman)to determine the maximum ATP hydrolyzed (ADP phosphorylated) per glucose consumed without oxygen [3].Aerobic calculation: Allow oxygen uptake by modifying exchange constraints:

ihuman = setExchangeBounds(ihuman, {'glucose', 'O2'}, [-1, -1000]);and re-run FBA [3].

This protocol yields theoretical values of 2 mol ATP/mol glucose under anaerobic conditions and 31.5 mol ATP/mol glucose under aerobic conditions, demonstrating the profound metabolic difference between respiratory and fermentative metabolism [3].

Gene Deletion Studies

FBA enables systematic prediction of essential genes and synthetic lethal interactions through in silico deletion studies:

Single gene deletion: For each gene in the network, evaluate its GPR (Gene-Protein-Reaction) expression as a Boolean statement. If the expression evaluates to false, constrain the associated reaction flux to zero [2].

Double gene deletion: Perform pairwise deletion of all possible gene combinations to identify synthetic lethal interactions where simultaneous deletion of two non-essential genes becomes lethal [2].

Growth assessment: For each deletion strain, calculate the predicted growth rate by maximizing the biomass objective function [2].

Essentiality classification: Classify genes as essential if the predicted growth rate falls below a threshold (e.g., <5% of wild-type growth), and non-essential otherwise [2].

This approach successfully identified 136 double gene knockout combinations that are synthetically lethal in E. coli, demonstrating FBA's utility in identifying potential multi-drug targets [1].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships in gene deletion studies:

Advanced Applications and Extensions

Phenotypic Phase Planes (PhPP)

Phenotypic Phase Plane analysis extends FBA by exploring how changes in multiple environmental conditions affect the optimal metabolic phenotype [1]. By repeatedly applying FBA while co-varying nutrient uptake constraints, PhPP generates maps that delineate distinct metabolic phases where different nutrients limit growth or product formation [2]. This approach helps identify optimal culture media compositions for maximizing growth rates or biotechnologically valuable product yields [2].

Metabolic Engineering

FBA provides a computational foundation for rational metabolic engineering through algorithms like OptKnock, which identifies gene knockout strategies that couple cellular growth with production of desirable compounds [1]. By strategically removing metabolic capabilities, these approaches force the metabolic network to redirect carbon flux toward target products while maintaining viability [1] [2]. This methodology has been successfully applied to improve yields of industrially important chemicals such as ethanol and succinic acid [2].

Drug Target Identification

In pharmaceutical applications, FBA enables systematic identification of potential drug targets in pathogens and cancer cells [2]. By simulating single and double gene deletions, researchers can identify metabolic chokepoints that are essential for pathogen survival but absent in human hosts [2]. This approach significantly accelerates the drug discovery process by prioritizing experimental validation toward the most promising targets.

Network Gap Filling

FBA forms the basis for algorithms that identify knowledge gaps in metabolic reconstructions by comparing in silico growth simulations with experimental results [1]. When a model fails to produce biomass precursors known to be essential for growth, these algorithms propose candidate reactions from biochemical databases that, when added to the model, restore growth capability [1]. This application demonstrates how FBA not only utilizes existing knowledge but also contributes to expanding biological knowledge bases.

Limitations and Considerations

Despite its broad utility, FBA has several important limitations that researchers must consider when interpreting results. A significant constraint is FBA's inability to predict metabolite concentrations, as the method focuses exclusively on flux distributions [1]. Additionally, FBA is suitable only for determining fluxes at steady state and cannot directly capture transient metabolic behaviors [1]. Except in some modified implementations, standard FBA does not account for regulatory effects such as enzyme activation by protein kinases or regulation of gene expression, which can lead to discrepancies between predictions and experimental observations [1].

The objective function selection profoundly influences FBA results, and the assumption that metabolism optimizes for a single biological objective represents a simplification of complex evolutionary pressures [1]. Furthermore, FBA predictions depend critically on the completeness and accuracy of the underlying metabolic reconstruction, with missing reactions or incorrect gene-protein-reaction associations potentially leading to erroneous conclusions [1].

Flux Balance Analysis represents a powerful mathematical framework for analyzing metabolic networks that has transformed systems biology and metabolic engineering. By combining stoichiometric constraints with optimization principles, FBA enables quantitative prediction of metabolic behaviors at genome scale. The method's computational efficiency allows high-throughput simulation of genetic and environmental perturbations, making it invaluable for both basic research and biotechnological applications.

As metabolic reconstructions continue to expand and improve, FBA's predictive power and applicability will further increase. Ongoing developments in incorporating regulatory information, kinetic constraints, and multi-scale modeling will address current limitations and extend FBA's utility. For researchers entering the field, mastering FBA provides a foundation for leveraging the growing repository of genome-scale metabolic models to address pressing challenges in biotechnology, medicine, and fundamental biological research.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a powerful mathematical approach for simulating the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, enabling researchers to predict cellular behaviors such as growth rates or biochemical production [1]. As a constraint-based method, FBA differentiates itself from kinetic modeling approaches by relying not on difficult-to-measure kinetic parameters but on physicochemical constraints that bound possible network behaviors [1] [2]. This framework allows for the analysis of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions—comprehensive databases of all known metabolic reactions in an organism and the genes that encode each enzyme [1]. The power of FBA lies in its ability to calculate how metabolites flow through these networks by applying two fundamental constraints: the steady-state assumption and mass balance. These core principles form the foundation upon which FBA builds to predict optimal metabolic flux distributions that align with specific cellular objectives, making it invaluable for fields ranging from metabolic engineering to drug discovery [5] [2].

Mathematical Foundations of FBA

The Stoichiometric Matrix and Mass Balance

At the core of FBA lies the stoichiometric matrix (S), a mathematical representation of the metabolic network where rows correspond to metabolites and columns represent biochemical reactions [1] [2]. Each entry in the matrix indicates the stoichiometric coefficient of a metabolite in a particular reaction, with negative values denoting consumption and positive values indicating production [6]. This matrix formally captures the mass balance relationships within the metabolic system.

The mass balance principle ensures that for each internal metabolite, the total amount produced must equal the total amount consumed when the system is at steady state [1]. This constraint is represented mathematically as:

S · v = 0

Where S is the stoichiometric matrix (of size m × n, for m metabolites and n reactions) and v is the flux vector containing the reaction rates [1] [2]. This equation encapsulates the steady-state assumption, meaning that the concentration of internal metabolites remains constant over time because production and consumption rates are balanced [2]. External metabolites (often denoted with an "X" prefix) are not included in this balance, as they can accumulate or be depleted, effectively defining the inputs and outputs of the network [6].

The Steady-State Assumption

The steady-state assumption is a key simplification that makes FBA computationally tractable for large-scale networks [2]. By assuming that internal metabolite concentrations do not change over time, the complex system of differential equations that would normally describe metabolic dynamics reduces to a system of linear equations [2] [7]. This assumption is biologically reasonable when modeling cellular growth under constant conditions, as the timescale of metabolic reactions is typically much faster than that of cellular growth and environmental changes [6].

The combination of these constraints defines the solution space of all possible flux distributions that satisfy the mass balance conditions [1]. In any realistic large-scale metabolic model, there are more reactions than metabolites (n > m), making the system underdetermined with multiple feasible solutions [1]. The set of all flux vectors v that satisfy S · v = 0 is called the null space of S, representing all metabolic flux distributions that maintain the steady state [6].

Linear Programming Formulation

Objective Functions and Optimization

To identify a biologically meaningful flux distribution from the many possible solutions in the null space, FBA incorporates an objective function representing the presumed evolutionary optimization goal of the organism [2]. Common biological objectives include maximizing biomass production (simulating growth), ATP production, or the synthesis of specific metabolites [1] [7].

Mathematically, this objective function is formulated as a linear combination of fluxes:

Z = c^T · v

Where c is a vector of weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the objective [1]. When optimizing for a single reaction (such as biomass production), c is typically a vector of zeros with a value of 1 at the position of the reaction of interest [1]. The biomass reaction itself is a pseudo-reaction that drains various biomass precursor metabolites (proteins, nucleic acids, lipids) from the system in their appropriate biological ratios [1].

Flux Constraints and Linear Programming

FBA further constrains the solution space by imposing upper and lower bounds on individual reaction fluxes, representing known physiological or environmental limitations [1]. These bounds can incorporate enzyme capacity, substrate availability, or gene knockout constraints [2].

The complete FBA problem is formulated as a linear programming optimization:

Maximize Z = c^T · v Subject to: S · v = 0 LB ≤ v ≤ UB

Where LB and UB represent the lower and upper bounds on reaction fluxes, respectively [2]. Linear programming algorithms efficiently identify the optimal flux distribution that maximizes the objective function while satisfying all constraints [6] [1]. For large metabolic networks, this calculation can be performed in seconds on modern computers, making FBA highly scalable [2].

Table 1: Key Components of the FBA Linear Programming Formulation

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix | S (m × n matrix) | Network structure of metabolic reactions |

| Flux Vector | v = (vâ‚, vâ‚‚, ..., vâ‚™) | Reaction rates in the network |

| Mass Balance | S · v = 0 | Steady-state constraint |

| Flux Bounds | LB ≤ v ≤ UB | Physiological constraints on reactions |

| Objective Function | Z = c^T · v | Cellular optimization goal |

Computational Implementation

Workflow and Algorithm

The practical implementation of FBA follows a systematic workflow that transforms a metabolic network reconstruction into quantitative flux predictions. The process begins with constructing the stoichiometric matrix from known biochemical reactions, followed by applying relevant constraints based on the biological scenario being modeled [6] [1]. The linear programming problem is then solved using specialized algorithms such as the simplex method to identify the optimal flux distribution [6].

Advanced FBA Techniques

Several extensions to basic FBA have been developed to address specific research questions or biological complexities. Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) determines the range of possible flux values for each reaction while maintaining optimal objective function value, identifying reactions with flexible flux levels [7]. Parsimonious FBA (pFBA) identifies the most efficient flux distribution among multiple optima by minimizing total flux through the network while maintaining optimal objective function value, reflecting cellular preference for energy efficiency [8] [7].

Recent methodological advances include frameworks like TIObjFind, which integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to identify context-specific objective functions by calculating Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to cellular objectives under different conditions [5]. This approach helps address one of the key challenges in FBA—selecting appropriate objective functions that accurately represent system performance across different environmental conditions [5].

Table 2: Advanced FBA Techniques and Their Applications

| Technique | Methodology | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | Calculates min/max flux for each reaction while maintaining optimal growth | Identify flexible and rigid reactions in network |

| Parsimonious FBA (pFBA) | Minimizes total flux while maintaining optimal objective | Find most energy-efficient flux distributions |

| Dynamic FBA (dFBA) | Extends FBA to dynamic conditions by coupling with external metabolite changes | Model time-dependent metabolic responses |

| TIObjFind | Integrates pathway analysis with FBA using Coefficients of Importance | Identify context-specific objective functions |

| Regulatory FBA (rFBA) | Incorporates gene regulatory constraints into FBA | Model regulatory effects on metabolism |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core FBA Protocol

Implementing FBA requires specific computational tools and methodologies. The following protocol outlines the key steps for performing basic flux balance analysis:

Model Preparation: Obtain a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction in a standardized format such as Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) [1]. These reconstructions contain all known metabolic reactions for an organism and the associated genes.

Constraint Definition: Apply mass balance constraints (S · v = 0) and set physiologically relevant flux bounds based on environmental conditions (e.g., nutrient availability) [1]. For growth simulations, glucose uptake might be limited to 18.5 mmol/gDW/h while oxygen uptake is set to a high value for aerobic conditions [1].

Objective Selection: Define an appropriate objective function based on the biological question. For growth prediction, this is typically a biomass reaction that converts metabolic precursors into biomass components at their known biological ratios [1].

Problem Solution: Use linear programming to solve the optimization problem. The COBRA Toolbox provides implementations of FBA algorithms in MATLAB, while COBRApy offers Python-based solutions [1] [8].

Result Validation: Compare predicted fluxes with experimental data such as growth rates or metabolic secretion profiles to validate model predictions [1].

Gene Deletion Studies

A common FBA application involves simulating gene knockouts to identify essential genes and potential drug targets:

Identify Target Reactions: Map genes to reactions using Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations, which are Boolean expressions defining how genes encode enzyme subunits or isozymes [2].

Constrain Reaction Fluxes: For single gene deletions, set the flux through associated reactions to zero. For multiple gene deletions, evaluate the GPR relationships to determine which reactions become inactive [2].

Solve Modified Problem: Perform FBA on the constrained network and calculate the resulting objective function (e.g., growth rate) [2].

Classify Gene Essentiality: Genes are classified as essential if the predicted growth rate falls below a threshold (e.g., <10% of wild-type growth) [2].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of FBA requires both computational tools and well-curated metabolic models. The table below outlines essential resources for conducting flux balance analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FBA

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Resources | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software Toolboxes | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB) [1], COBRApy (Python) [8], FlexFlux [5] | Implement FBA algorithms and related constraint-based methods |

| Metabolic Databases | KEGG [5], EcoCyc [5] | Provide curated metabolic pathway information for network reconstruction |

| Model Repositories | UCSD Systems Biology (35+ models) [1], BioModels | Access pre-built genome-scale metabolic models |

| Linear Programming Solvers | GLPK [8], MATLAB Optimization Toolbox | Solve the underlying linear programming optimization problems |

| Visualization Tools | pySankey [5], Escher | Create flux maps and visualize metabolic networks |

Applications in Biotechnology and Medicine

The constraint-based framework of FBA has enabled diverse applications across biological research and biotechnology. In metabolic engineering, FBA identifies gene knockout strategies that optimize production of industrially valuable compounds such as ethanol and succinic acid [2]. OptKnock and similar algorithms use FBA to predict genetic modifications that couple desired product formation with cellular growth [1].

In biomedical research, FBA helps identify potential drug targets by determining essential genes in pathogens [5] [2]. Cancer researchers use FBA to understand metabolic reprogramming in tumor cells and identify cancer-specific dependencies [2]. FBA also models host-pathogen interactions and the human microbiota, simulating metabolic interactions in complex microbial communities [2].

More advanced applications include phenotypic phase plane analysis (PhPP), which maps optimal metabolic phenotypes across different nutrient conditions, and culture media optimization, where FBA identifies minimal media components that support microbial growth [2]. These diverse applications demonstrate how the fundamental constraints of steady-state and mass balance provide a powerful framework for understanding and engineering biological systems.

In the realm of systems biology and metabolic engineering, the stoichiometric matrix (S) serves as the fundamental blueprint for quantifying cellular metabolism. This mathematical construct provides a structured representation of all chemical reactions within a metabolic network, enabling researchers to simulate and analyze metabolic capabilities using constraint-based modeling approaches [6]. The matrix encodes the stoichiometry of biochemical transformations, where rows typically represent metabolites and columns represent reactions [9]. The power of this framework lies in its ability to translate biological knowledge into a mathematical format amenable to computational analysis, particularly through Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which finds an optimal net flow of mass through the metabolic network that follows constraints defined by the user [6].

For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the stoichiometric matrix is essential for investigating metabolic adaptations in diseases, identifying potential drug targets, and optimizing bioproduction strains [6]. The matrix forms the foundation for in silico models that can predict metabolic behaviors under various genetic and environmental conditions, providing a cost-effective alternative to extensive laboratory experimentation.

Mathematical Foundation and Structural Properties

Fundamental Principles and Notation

The stoichiometric matrix represents a set of reactions involving given components within a metabolic network. By convention, entries in the matrix are stoichiometric coefficients that are negative for reactants (substrates consumed) and positive for products (metabolites formed) [9]. This sign convention ensures proper mass balance throughout the system.

Consider a metabolic network with m metabolites and n reactions. The stoichiometric matrix S has dimensions m × n, where each element S[i,j] represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. The mathematical representation of the entire network can be expressed as:

S · v = 0

where v is the flux vector containing the reaction rates [6]. This equation represents the steady-state assumption, a core principle in constraint-based modeling, which states that the quantity of metabolites within the system cannot change over time [6].

Practical Illustrations of Stoichiometric Matrices

To illustrate the structure of stoichiometric matrices, consider a simple network involving hydrogen, oxygen, and their derivatives [9]:

Reaction Set:

- 2H₂ + O₂ ⇄ 2H₂O

- H₂ + O₂ ⇄ H₂O₂

Stoichiometric Matrix S:

| Component | Reaction 1 | Reaction 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | -2 | -1 |

| Oâ‚‚ | -1 | -1 |

| Hâ‚‚O | 2 | 0 |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | 0 | 1 |

Table 1: Stoichiometric matrix for the hydrogen-oxygen reaction system. Negative coefficients indicate consumption, positive coefficients indicate production.

This example demonstrates how the matrix captures the complete stoichiometric information of the network. The first reaction consumes 2 Hâ‚‚ and 1 Oâ‚‚ to produce 2 Hâ‚‚O, while the second reaction consumes 1 Hâ‚‚ and 1 Oâ‚‚ to produce 1 Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚.

Another example involves isomerization and dimerization reactions [9]:

Reaction Set:

- c-Câ‚„H₈ + t-Câ‚„H₈ ⇄ C₈Hâ‚₆

- c-C₄H₈ ⇄ t-C₄H₈

Stoichiometric Matrix:

| Component | Reaction 1 | Reaction 2 |

|---|---|---|

| c-C₄H₈ | -1 | -1 |

| t-C₄H₈ | -1 | 1 |

| C₈Hâ‚₆ | 1 | 0 |

Table 2: Stoichiometric matrix for isomerization and dimerization reactions.

Metabolic Network Visualization

The following diagram illustrates how a metabolic network is translated into a stoichiometric matrix, showing the relationship between metabolites (A, B, C, D) and reactions (v1, v2, v3):

Figure 1: Metabolic network translation to stoichiometric matrix. Yellow nodes represent internal metabolites, green nodes represent external metabolites, and blue circles represent metabolic reactions.

The Stoichiometric Matrix in Flux Balance Analysis

Integration with Constraint-Based Modeling

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) leverages the stoichiometric matrix as its core mathematical framework. FBA is built on a technique called linear programming (LP), a well-established method for solving optimization problems [6]. In this context, the stoichiometric matrix defines the constraints that govern the mass balance of the metabolic system.

The fundamental equation of FBA is:

S · v = 0

subject to: α ≤ v ≤ β

where v is the flux vector representing reaction rates, and α and β are lower and upper bounds on these fluxes, respectively [6]. The equation represents the steady-state assumption, which prevents metabolites from having unrealistic quantities by requiring that their production and consumption rates balance to zero [6].

Mass Balance and Element Conservation

The stoichiometric matrix enables verification of element conservation across all reactions in the network. This is mathematically expressed as:

S · M = 0

where M is the molecular matrix containing element compositions of each metabolite [9]. Each entry in the product matrix expresses the difference in atom counts of a particular element in a specific reaction. A zero matrix confirms that all elements are properly conserved in all reactions.

For the hydrogen-oxygen example, verifying hydrogen conservation in the first reaction involves calculating: (-2)(2) + (-1)(0) + (2)(2) + (0)(2) = 0, where the first set of parentheses contains stoichiometric coefficients from S and the second set contains hydrogen atom counts from M [9].

Key Components and Balances

Reduced Row Echelon Form (RREF) analysis of the stoichiometric matrix reveals important structural properties. The pivots identify key components, while non-pivot columns reveal balances obeyed by non-key components [9]. For the hydrogen-oxygen system, the RREF of the stoichiometric matrix is:

| Component | Reaction 1 | Reaction 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 1 | 0 |

| Oâ‚‚ | 0 | 1 |

| Hâ‚‚O | -2 | 2 |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | 1 | -2 |

Table 3: RREF of the stoichiometric matrix for the hydrogen-oxygen system.

This indicates that Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ are key components, and the relationships for non-key components are [9]:

ΔnH₂O = -2ΔnH₂ + 2ΔnO₂

ΔnH₂O₂ = ΔnH₂ - 2ΔnO₂

where Δ indicates changes in amounts caused by the reactions.

Advanced Matrix Applications and Analysis

The Augmented Stoichiometric Matrix

Augmenting the stoichiometric matrix with additional information enables more sophisticated analyses. When augmented with a unit matrix, the RREF can reveal dependencies between reactions and identify key and non-key reactions [9].

For a system with three reactions (the original two plus 2H₂O + O₂ ⇄ 2H₂O₂), the augmented stoichiometric matrix and its RREF reveal that:

Number of key components = Number of key reactions [9]

This fundamental equality highlights the relationship between the structural components of the network and the independent biochemical processes.

FBA Optimization Process

The following diagram illustrates the complete Flux Balance Analysis workflow, showing how the stoichiometric matrix serves as the foundation for constraint-based modeling:

Figure 2: Flux Balance Analysis workflow incorporating the stoichiometric matrix.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Constructing a Stoichiometric Matrix from Biochemical Data

Objective: Create a stoichiometric matrix from known metabolic pathways of a target organism.

Materials Required:

- Annotated genome data of the target organism

- Biochemical databases (e.g., KEGG, MetaCyc)

- Computational tools (COBRA Toolbox, Python with appropriate libraries)

- Metabolic network reconstruction software

Procedure:

- Identify all metabolic reactions: Compile a complete list of biochemical transformations present in the target organism using genomic annotation and literature data [10].

- List all metabolites: Create a comprehensive inventory of all metabolites participating in these reactions, distinguishing between internal and external metabolites [6].

- Assign stoichiometric coefficients: For each reaction, assign appropriate coefficients to each metabolite (negative for substrates, positive for products).

- Construct the matrix: Create a matrix where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions, filling in the stoichiometric coefficients.

- Verify mass balance: Check that

S · M = 0for the molecular matrixMto ensure element conservation [9]. - Validate network connectivity: Ensure all metabolites are properly connected and no dead-ends exist without transport mechanisms.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If mass balance fails for certain reactions, verify the reaction stoichiometry from multiple databases

- For metabolites that accumulate without consumption, add appropriate transport or exchange reactions

- Ensure reversible reactions are properly annotated with appropriate flux bounds

Protocol: Performing Basic Flux Balance Analysis

Objective: Use the stoichiometric matrix to predict metabolic flux distributions under specific conditions.

Materials Required:

- Stoichiometric matrix for the target organism

- COBRA Toolbox in MATLAB or appropriate Python packages [10]

- Linear programming solver (e.g., GLPK, CPLEX)

- Condition-specific constraint data

Procedure:

- Import the stoichiometric matrix: Load the matrix into your analysis environment.

- Apply flux constraints: Set lower and upper bounds for each reaction based on environmental conditions and enzyme capacities [6].

- Define objective function: Specify the biological objective to optimize (e.g., biomass production, ATP synthesis, or metabolite synthesis) [6].

- Solve the LP problem: Use the simplex method or other LP algorithms to find the flux distribution that optimizes the objective function while satisfying all constraints [6].

- Analyze results: Examine the flux distribution to identify key pathways and potential bottlenecks.

- Validate predictions: Compare with experimental data when available to assess model accuracy.

Research Applications and Implementation Tools

Table 4: Essential tools and resources for stoichiometric matrix-based research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling [10] | Metabolic network analysis, FBA, strain design |

| Python (with cobrapy) | Python implementation of COBRA methods | Custom metabolic modeling, integration with data science workflows |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | Core representation of metabolic network structure [9] | All flux balance analysis applications |

| Linear Programming Solver | Algorithm to solve optimization problems [6] | Finding optimal flux distributions |

| Molecular Matrix (M) | Elemental composition of metabolites [9] | Verifying element conservation in networks |

| RREF Analysis | Matrix decomposition method [9] | Identifying key components and reaction dependencies |

Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

Stoichiometric modeling using FBA has demonstrated significant value in identifying drug targets, particularly in infectious diseases. For example, researchers have used these approaches for rapid countermeasure discovery against pathogens like Francisella tularensis by analyzing essential metabolic functions [10]. Similarly, metabolic network reconstruction and analysis of Yersinia pestis (the causative agent of plague) has identified potential vulnerabilities for antibiotic development [10].

In drug development, these methods enable system-level analysis of bacterial physiology to identify new drug targets that may not be apparent from single-enzyme studies [10]. By simulating gene knockout strategies using approaches like OptKnock, researchers can predict which enzymatic reactions are essential for pathogen survival under specific conditions [10].

The stoichiometric matrix serves as the fundamental blueprint that translates biochemical knowledge into a mathematical framework for metabolic analysis. Its implementation in Flux Balance Analysis enables researchers to predict cellular behaviors, identify critical metabolic pathways, and develop intervention strategies for biomedical and biotechnological applications. As systems biology continues to evolve, the stoichiometric matrix remains a cornerstone technology for understanding complex metabolic networks, with ongoing developments extending its application to microbial communities and multicellular systems [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, proficiency with this mathematical framework provides a powerful approach for investigating metabolic processes and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a powerful mathematical approach for analyzing the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, enabling researchers to predict cellular phenotypes from genomic information [1]. This constraint-based method calculates the flow of metabolites through metabolic networks, making it possible to predict fundamental biological objectives such as the growth rate of an organism or the rate of production of a biotechnologically important metabolite [1]. FBA has become an indispensable tool in systems biology and metabolic engineering, with established metabolic models available for dozens of organisms [1].

The fundamental principle behind FBA is that it operates on steady-state mass balance constraints, differentiating it from kinetic models that require numerous difficult-to-measure parameters [1]. This approach allows for rapid simulation of metabolic capabilities under various environmental and genetic perturbations, providing researchers with testable hypotheses about organism behavior. FBA has found diverse applications in physiological studies, gap-filling efforts, and genome-scale synthetic biology [1], making it particularly valuable for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand and manipulate metabolic systems.

Mathematical Foundation of FBA

Core Mathematical Representation

The first step in FBA is to mathematically represent metabolic reactions using a stoichiometric matrix (S) of size m×n, where m represents the number of unique compounds and n represents the number of reactions in the network [1]. Each column in this matrix represents one reaction, with entries representing the stoichiometric coefficients of the metabolites participating in that reaction. The system of mass balance equations at steady state (dx/dt = 0) is represented by the equation:

Sv = 0

where v is the vector of reaction fluxes and x is the vector of metabolite concentrations [1]. In any realistic large-scale metabolic model, there are more reactions than compounds (n > m), meaning there are more unknown variables than equations, and thus no unique solution to this system.

Constraints and Optimization

FBA incorporates two types of constraints: equality constraints that balance reaction inputs and outputs, and inequality constraints that impose bounds on the system [1]. The matrix of stoichiometries imposes flux balance constraints, ensuring that the total amount of any compound being produced equals the total amount being consumed at steady state. Each reaction can also be assigned upper and lower bounds (vi,max and vi,min), which define the maximum and minimum allowable fluxes.

Table 1: Types of Constraints in Flux Balance Analysis

| Constraint Type | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Balance | Sv = 0 | Total production = total consumption for each metabolite |

| Capacity | vi,min ≤ vi ≤ vi,max | Thermodynamic and enzyme capacity limitations |

| Uptake | vexchange ≤ vexchange,max | Nutrient availability in environment |

FBA identifies optimal points within this constrained solution space by maximizing or minimizing an objective function Z = cTv, which is a linear combination of fluxes [1]. The vector c contains weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the objective function. Optimization of this system is accomplished using linear programming, with the output being a particular flux distribution (v) that maximizes or minimizes the objective function.

Simulating Growth and Metabolite Production

Defining Biological Objectives

The simulation of growth requires defining a biological objective relevant to the problem being studied. For predicting growth, the objective is typically biomass production, representing the rate at which metabolic compounds are converted into biomass constituents such as nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids [1]. Mathematically, this is represented by a 'biomass reaction' that drains precursor metabolites from the system at their relative stoichiometries to simulate biomass production.

This biomass reaction is scaled so that the flux through it equals the exponential growth rate (μ) of the organism [1]. For metabolite production, the objective function may be modified to maximize the output of a specific biotechnologically or therapeutically relevant compound instead of biomass.

Practical Implementation

The following DOT script illustrates the workflow for implementing FBA to simulate growth and metabolite production:

Workflow for FBA Implementation

Implementation of FBA requires specialized computational tools. The COBRA (Constraints-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) Toolbox is a freely available MATLAB toolbox that can perform a variety of FBA-based methods [1]. Models for the COBRA Toolbox are typically saved in the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) format, which enables interoperability between different software platforms [1] [4].

Case Study: Predicting Aerobic and Anaerobic Growth in E. coli

To illustrate growth simulation, consider predicting the growth of E. coli under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. For aerobic growth, the maximum rate of glucose uptake is constrained to a physiologically realistic level (e.g., 18.5 mmol glucose gDW-1 hr-1), while the maximum rate of oxygen uptake is set to a high level so it doesn't constrain growth [1]. Linear programming then determines the flux distribution that maximizes growth rate, typically resulting in a predicted exponential growth rate of 1.65 hr-1.

For anaerobic growth, the maximum uptake of oxygen is constrained to zero, resulting in a significantly lower predicted growth rate of 0.47 hr-1 [1]. These predictions have been experimentally validated, demonstrating FBA's accuracy in simulating growth phenotypes.

Case Study: Calculating ATP Yield per Glucose Consumed

FBA can also simulate metabolite production, such as calculating ATP yield per glucose consumed. This is quantified by the flux through the ATP hydrolysis reaction, with the objective function modified to maximize this flux [3]. When glucose uptake is constrained to 1 mmol/gDW/h and oxygen uptake is prohibited, FBA predicts an ATP yield of 2 mol ATP/mol glucose, consistent with theoretical expectations for anaerobic conditions [3].

When oxygen uptake is allowed, the ATP yield increases dramatically to approximately 31.5 mol ATP/mol glucose, reflecting the much higher energy yield of aerobic respiration [3]. This demonstrates how FBA can capture fundamental metabolic shifts under different environmental conditions.

Table 2: Example FBA Simulations for Biological Objectives

| Simulation Type | Constraints Applied | Objective Function | Typical Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Growth | Glucose uptake ≤ 18.5 mmol/gDW/h; High O2 uptake | Maximize biomass reaction | E. coli growth rate ~1.65 hâ»Â¹ |

| Anaerobic Growth | Glucose uptake ≤ 18.5 mmol/gDW/h; O2 uptake = 0 | Maximize biomass reaction | E. coli growth rate ~0.47 hâ»Â¹ |

| Anaerobic ATP Yield | Glucose uptake = 1 mmol/gDW/h; O2 uptake = 0 | Maximize ATP hydrolysis flux | 2 mol ATP/mol glucose |

| Aerobic ATP Yield | Glucose uptake = 1 mmol/gDW/h; High O2 uptake | Maximize ATP hydrolysis flux | ~31.5 mol ATP/mol glucose |

Advanced FBA Applications in Drug Development

Drug Target Identification

FBA has emerged as a valuable tool for drug target identification, particularly for infectious diseases and metabolic disorders. For pathogenic diseases, the approach typically involves identifying enzymes crucial for the survival and growth of the pathogen through FBA-based growth simulation [11]. The following DOT script illustrates the two-stage FBA approach for drug target identification:

Two-Stage FBA for Drug Targets

This two-stage FBA method first finds the steady optimal fluxes of reactions and mass flows of metabolites in the pathologic state, then determines these values in the medication state with minimal side effects [11]. Drug targets are identified by comparing reaction fluxes in both states and examining which reaction fluxes need to be altered to restore health.

Integration with Machine Learning and Multi-Omics

Recent advances have integrated FBA with complementary approaches to enhance its predictive power. Machine learning techniques have emerged as tools for data reduction and variable selection in large datasets, helping to improve the biological interpretation of FBA results [12]. The integration of multi-omics datasets with genome-scale metabolic models provides a platform for modeling context-specific network behavior and improving genotype-to-phenotype predictions [12].

These integrated approaches are particularly valuable for drug development, as they can account for individual metabolic variations and predict patient-specific responses to therapeutic interventions.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of FBA requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table details key components of the FBA research toolkit:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Flux Balance Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Example/Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Software | MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | optimizeCbModel function [1] |

| RAVEN Toolbox | Software | MATLAB toolbox for FBA and metabolic modeling | solveLP function [3] |

| SBML Format | Data Standard | Model exchange between different software platforms | XML-based format [4] |

| Linear Programming Solver | Software | Optimization engine for solving FBA problems | Gurobi, CPLEX [3] |

| Genome-Scale Models | Data Resource | Metabolic network reconstructions | SystemsBiology.ucsd.edu repositories [1] |

| Stoichiometric Matrix | Data Structure | Mathematical representation of metabolic network | S matrix (m×n) [1] |

| Biomass Reaction | Model Component | Simulates biomass production from precursors | Drain reaction for biomass constituents [1] |

Technical Protocols

Basic FBA Protocol for Growth Simulation

Load Metabolic Model: Import a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction in SBML format using the

readCbModelfunction [1].Set Environmental Constraints: Define upper and lower bounds for exchange reactions to simulate specific environmental conditions (e.g., carbon source availability, oxygen presence) [3]. Use the

changeRxnBoundsfunction to modify these constraints.Define Biological Objective: Set the objective function to maximize biomass production for growth simulations [1]. The

setParamfunction can be used to specify the objective reaction and its coefficient.Solve Linear Programming Problem: Use the

optimizeCbModel(COBRA) orsolveLP(RAVEN) function to find the optimal flux distribution [1] [3].Extract and Interpret Results: Analyze the flux distribution to determine growth rate (biomass flux) and key metabolic fluxes.

Protocol for Metabolite Production Optimization

Load and Constrain Model: Follow steps 1-2 from the basic protocol to set up the base model with appropriate environmental constraints.

Modify Objective Function: Set the objective to maximize flux through the reaction producing the target metabolite using the

setParamfunction [3].Apply Additional Constraints: Optionally constrain biomass to a minimum value to ensure cell viability while maximizing product formation.

Solve and Validate: Perform FBA and check feasibility of the solution. Flux variability analysis can identify alternate optimal solutions [1].

Flux Balance Analysis provides a powerful framework for simulating growth and metabolite production by leveraging genome-scale metabolic models and constraint-based optimization. Its mathematical foundation in stoichiometric modeling and linear programming enables quantitative prediction of metabolic phenotypes under various genetic and environmental conditions. The continued development of more comprehensive metabolic models, coupled with integration of multi-omics data and machine learning approaches, promises to further enhance FBA's utility in basic research and drug development applications. For researchers entering this field, mastering the core principles and protocols outlined in this guide provides a solid foundation for leveraging FBA in their investigations of metabolic systems.

Why Use FBA? Advantages Over Kinetic Modeling Approaches

Constraint-based modeling, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), has emerged as a fundamental tool for analyzing metabolic networks at the genome-scale, enabling researchers to predict organism behavior under various genetic and environmental conditions [13] [14]. This approach stands in contrast to kinetic modeling, which aims to describe the detailed temporal dynamics of metabolic components through differential equations that require extensive mechanistic details and kinetic parameters [13]. While kinetic models provide valuable insights into metabolic dynamics, their application is often limited to small-scale systems due to the scarcity of comprehensive enzyme kinetic data [14].

The fundamental difference between these approaches lies in their core assumptions and data requirements. FBA operates on the principle that metabolic networks reach a steady state, allowing researchers to analyze flux distributions through stoichiometric mass-balance constraints without requiring detailed kinetic information [14]. This methodological distinction creates significant advantages for FBA in applications requiring genome-scale analysis, particularly in drug development and biotechnology where comprehensive cellular modeling is essential [15] [12].

Fundamental Differences Between FBA and Kinetic Modeling

Core Principles and Methodological Frameworks

Flux Balance Analysis employs a constraint-based approach that identifies steady-state flux rates through a metabolic network by satisfying stoichiometric mass-balance constraints and reaction directionality [14]. This methodology focuses on predicting metabolic phenotypes by optimizing an objective function, typically biomass production, within physicochemical constraints [14]. The mathematical foundation of FBA enables the analysis of genome-scale metabolic models comprising thousands of reactions, making it particularly valuable for systems-level investigations [13] [14].

In contrast, kinetic modeling of metabolic networks aims to study the dynamical behavior of metabolic components by describing how these components interact with each other over time [13]. This approach typically employs ordinary differential equations (ODEs) where the state variable is determined by the concentrations of metabolic components, and the system describes the rate of change of these concentrations through functions that incorporate detailed enzymatic mechanisms [13]. The vector of reaction rates in kinetic models is typically highly nonlinear, incorporating mechanisms based on Michaelis-Menten or Hill laws, which significantly contributes to the complexity of system analysis [13].

Table 1: Fundamental Methodological Differences Between FBA and Kinetic Modeling

| Characteristic | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Foundation | Linear programming; Constraint-based optimization | Nonlinear ordinary differential equations |

| Primary Output | Steady-state flux distributions | Temporal concentration profiles |

| Time Consideration | Steady-state assumption | Explicit time dependence |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale (2000+ reactions) | Small-scale subsystems |

| Parameter Requirements | Stoichiometry, reaction directionality | Enzyme kinetic parameters, mechanistic details |

Data Requirements and Scalability

The data requirements for these approaches differ substantially. Kinetic models demand extensive parameter sets including enzyme kinetic constants, mechanistic details of enzymatic reactions, and regulatory information [13] [14]. This creates a fundamental limitation, as noted in research: "Traditional metabolic modeling techniques involve the reconstruction of kinetic models based on detailed knowledge on enzyme kinetic parameters for all enzymes in a certain system. These models are limited to small-scale systems due to lack of sufficient data on kinetic constants and the highly complex nature of these models" [14].

FBA circumvents these limitations by relying primarily on network stoichiometry and directionality constraints [14]. This fundamental difference in data requirements enables FBA to be applied to genome-scale metabolic models of organisms such as Escherichia coli (comprising more than 2000 reactions) and human metabolism (containing more than 13,000 reactions) [13]. The scalability of FBA makes it particularly suitable for analyzing complex biological systems where comprehensive kinetic data remains unavailable.

Key Advantages of FBA for Practical Applications

Scalability to Genome-Level Networks

The most significant advantage of FBA lies in its ability to model genome-scale metabolic networks, which is particularly valuable for drug development professionals seeking to understand system-wide metabolic responses [13] [12]. Where kinetic modeling approaches struggle beyond several dozen reactions due to parameter identifiability issues and computational complexity, FBA successfully analyzes networks comprising thousands of reactions and metabolites [13]. This scalability enables researchers to model complete metabolic systems of microorganisms and human cells, providing comprehensive insights into metabolic capabilities and potential therapeutic targets [13].

This genome-scale capability is especially relevant for predicting the effects of genetic perturbations in industrial microorganisms or identifying potential drug targets in pathogenic organisms [15] [14]. By simulating gene knockouts or enzyme inhibition scenarios across the entire metabolic network, FBA enables systematic identification of essential reactions and potential vulnerabilities – applications that would be computationally prohibitive with kinetic modeling approaches [14].

Minimal Parameter Requirements

FBA requires significantly fewer parameters than kinetic modeling, needing only reaction stoichiometries and directionality constraints rather than detailed kinetic constants [14]. This parameter efficiency is particularly advantageous when modeling poorly characterized systems or organisms where comprehensive kinetic data is unavailable. The method's robustness to parameter uncertainty makes it invaluable for preliminary investigations and hypothesis generation in early-stage research [14].

Advanced FBA extensions like the MetabOlic Modeling with ENzyme kineTics (MOMENT) method incorporate enzyme kinetic parameters when available, demonstrating how FBA can integrate additional data without sacrificing scalability [14]. This hybrid approach utilizes prior data on enzyme turnover rates and enzyme molecular weights to improve flux predictions while maintaining the computational advantages of constraint-based modeling [14].

Table 2: Comparison of Parameter Requirements and Integration Capabilities

| Parameter Type | FBA Requirements | Kinetic Modeling Requirements | FBA Integration Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometry | Essential | Essential | Network reconstruction |

| Reaction Directionality | Essential | Essential | Thermodynamic constraints |

| Enzyme Kinetics | Optional | Essential | MOMENT method [14] |

| Nutrient Uptake Rates | Optional (for growth rate prediction) | Essential | Experimentally constrained FBA |

| Gene Expression | Optional | Not typically used | E-flux method [14] |

Integration with Multi-Omics Data and Machine Learning

FBA provides a robust framework for integrating diverse data types, including transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic measurements [12]. This integration capability is enhanced by the method's compatibility with machine learning approaches, which have emerged as powerful tools for data reduction and variable selection in large biological datasets [12]. The combination of FBA with machine learning enables researchers to overcome interpretation challenges associated with large metabolic models and extensive omics datasets [12].

Research highlights that "the integration of flux balance analysis with complementary data analysis and modeling techniques offers the potential to overcome these challenges. In particular machine learning approaches have emerged as the tool of choice for data reduction and selection of most important variables in big data sets" [12]. This synergy allows for more accurate context-specific modeling of metabolic behavior in different tissues, disease states, or environmental conditions – capabilities that are particularly valuable for drug development applications [15] [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Implementation

Standard FBA Protocol for Metabolic Phenotype Prediction

The following protocol outlines the core methodology for implementing Flux Balance Analysis to predict metabolic phenotypes:

Network Reconstruction: Compile a genome-scale metabolic network reconstruction including all known metabolic reactions, their stoichiometries, and directionality constraints based on biochemical literature and genomic annotations [14].

Stoichiometric Matrix Formation: Construct the stoichiometric matrix S where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions, with elements indicating the stoichiometric coefficients of each metabolite in each reaction [14].

Constraint Definition: Apply mass-balance constraints at steady state (S·v = 0, where v is the flux vector) and capacity constraints (vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax) based on reaction irreversibility and measured uptake rates when available [14].

Objective Function Specification: Define an appropriate biological objective function, typically biomass production representing cellular growth, though other objectives such as ATP production or metabolite synthesis may be used depending on the biological context [14].

Linear Programming Optimization: Solve the linear programming problem to find the flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes the objective function: maximize c^T·v subject to S·v = 0 and vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax, where c is the vector of objective coefficients [14].

Result Validation and Analysis: Compare predicted flux distributions with experimental measurements such as growth rates, nutrient consumption, or product formation rates, and perform additional analyses like flux variability analysis to assess solution space properties [14].

Advanced FBA Protocol: Integrating Enzyme Kinetics (MOMENT Method)

The MOMENT (MetabOlic Modeling with ENzyme kineTics) method enhances standard FBA by incorporating enzyme kinetic constraints while maintaining scalability [14]:

Kinetic Data Compilation: Collect enzyme turnover numbers (k_cat values) and molecular weights for metabolic enzymes from databases such as BRENDA and SABIO-RK [14].

Enzyme Capacity Constraint Formulation: Implement the constraint that the total enzyme concentration required to support metabolic fluxes cannot exceed the measured or estimated cellular protein capacity: Σ (vi / kcati · MWi) ≤ Etotal, where vi is the flux through reaction i, kcati is the turnover number, MWi is the molecular weight, and Etotal is the total enzyme capacity [14].

Multi-enzyme Complex Handling: Account for isozymes, protein complexes, and multi-functional enzymes by appropriately weighting their contributions to the total enzyme budget [14].

Integrated Optimization: Solve the modified optimization problem that maximizes biomass production subject to both stoichiometric constraints and the enzyme capacity constraint [14].

Growth Rate Prediction: Utilize the method to predict absolute growth rates across different media conditions without requiring experimental measurement of nutrient uptake rates, leveraging the identified design principle that enzymes catalyzing high-flux reactions tend to have higher turnover numbers [14].

Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Modeling

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Metabolic Modeling

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Structured representation of metabolic network | Foundation for both FBA and kinetic modeling [14] |

| BRENDA Database | Source of enzyme kinetic parameters (k_cat values) | Enhancing FBA with kinetic constraints (MOMENT method) [14] |

| SABIO-RK Database | Repository for biochemical reaction kinetics | Parameter estimation for kinetic models and advanced FBA [14] |

| Linear Programming Solvers | Optimization algorithms for constraint-based modeling | Core computational engine for FBA [14] |

| ODE Integration Algorithms | Numerical solvers for differential equations | Time-course simulation in kinetic models [13] |

Applications in Drug Development and Biotechnology

FBA provides significant advantages for drug development professionals, particularly through its ability to predict system-level metabolic responses to perturbations [15] [12]. This capability is invaluable for identifying potential drug targets, especially in antimicrobial development where predicting essential genes in pathogenic organisms can guide target selection [14]. The FDA's Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) Science and Research Program has recognized the importance of advanced modeling approaches for generic drug development, particularly for complex products including implants, inhalation, and topical formulations [15].

In biotechnology applications, FBA enables metabolic engineers to predict how genetic modifications will affect product yield and cellular growth [14]. The method's ability to simulate knockouts and overexpression experiments in silico significantly reduces experimental workload by prioritizing the most promising genetic manipulations [14]. Furthermore, FBA's scalability allows for modeling multi-tissue or multi-organism systems, which is particularly valuable for understanding host-pathogen interactions or complex microbiomes [12].

Flux Balance Analysis offers distinct advantages over kinetic modeling approaches, particularly for genome-scale applications in drug development and biotechnology. Its minimal parameter requirements, scalability to complex networks, and compatibility with multi-omics data integration make FBA an indispensable tool for researchers and scientists. While kinetic modeling provides valuable insights into metabolic dynamics for well-characterized subsystems, FBA enables system-level analysis that would be computationally prohibitive with kinetic approaches. The continued development of FBA methodologies, including hybrid approaches that incorporate kinetic constraints while maintaining scalability, promises to further enhance its utility for predicting metabolic behavior and guiding experimental design in biological research and therapeutic development.

How FBA Works: A Step-by-Step Methodology and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are mathematical representations of the entire metabolic network of an organism, constructed from its genomic information [16]. These models consist of a microbe's entire metabolic map, determined from whole-genome sequencing and annotation of the genomic material encoded in its DNA [16]. By placing genome annotation in the context of how biochemical components combine to consume substrates, produce energy, and facilitate growth, GEMs demonstrate the breadth of our understanding of an organism while highlighting knowledge gaps [16]. The process of creating a metabolic model enables researchers to simulate and manipulate cellular growth in silico using techniques like flux balance analysis (FBA), a constraint-based linear optimization approach for predicting flow of compounds through metabolic networks [16] [3]. GEMs have become powerful frameworks for investigating complex biological systems, including host-microbe interactions, at a systems level [17].

Theoretical Foundation of Metabolic Modeling

Fundamental Principles of Constraint-Based Modeling

Constraint-based modeling approaches, including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), rely on the fundamental principle of mass conservation within metabolic networks. FBA is a mathematical approach to finding an optimal net flow of mass through a metabolic network that follows a set of instructions defined by the user [18]. This method uses a linear programming technique that employs metabolic models to predict phenotypic responses imposed by environmental elements and factors [16]. The core mathematical formulation represents the metabolic network as a stoichiometric matrix S, where m × n dimensions correspond to m metabolites and n reactions. The system assumes steady-state conditions, represented by the equation S · v = 0, where v is the flux vector through each reaction. Additional constraints are applied through lower and upper bounds (αi ≤ vi ≤ βi) that define reaction reversibility and capacity.

Optimization in Metabolic Networks

The underdetermined nature of metabolic networks (typically with more reactions than metabolites) means multiple flux distributions can satisfy the stoichiometric constraints [16]. FBA resolves this by optimizing for an objective function, typically formulated as Z = c^T · v, where Z represents the objective to be maximized or minimized (e.g., biomass production or ATP yield) [16] [3]. For example, in FBA, "the optimization is typically to maximize the amount of flux through that equation that represents the objective function" [16]. The system of equations representing the cell must produce a solution that results in flux through the objective function equation [16].

Table 1: Key Components of a Constraint-Based Metabolic Model

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | m × n matrix | Encodes metabolic network connectivity; m metabolites, n reactions |

| Flux Vector (v) | v = (v1, v2, ..., vn)^T | Reaction rates in mmol/gDW/h |

| Mass Balance | S · v = 0 | Steady-state assumption; mass conservation |

| Capacity Constraints | αi ≤ vi ≤ βi | Thermodynamic and enzyme capacity limits |

| Objective Function | Z = c^T · v | Biological objective (e.g., biomass maximization) |

Computational Workflow for GSMM Reconstruction

The process of building a genome-scale metabolic model from genomic data follows a systematic workflow with distinct stages, as illustrated below.

Diagram 1: The GSMM Reconstruction Workflow from DNA to a functional metabolic model capable of running Flux Balance Analysis.

Genome Annotation and Functional Role Identification

The initial step in building a metabolic model involves identifying all genes present in an organism and assigning functional roles to those genes [16]. Multiple tools are available for genome annotation, including RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology), PROKKA, BG7, Blast2GO, and BASys [16]. These tools take unannotated contigs and iterate through steps for accurately identifying protein- and RNA-encoding genes while assigning functional roles. For metabolic modeling purposes, annotations should ideally include Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, which serve as critical connectors between different repositories [16]. The output from these annotation tools typically includes spreadsheets, GenBank files, or GFF files containing the list of functional roles identified in the genome [16].

Converting Functional Roles to Metabolic Reactions

After identifying protein-encoding genes and assigning functions, the next critical step involves converting these functional roles to the enzyme complexes they form and subsequently to the metabolic reactions they catalyze [16]. This process involves navigating complex many-to-many relationships: "Enzyme complexes can be formed by one or several functional roles, and each functional role can be involved in one or more complexes" [16]. Similarly, "each reaction in a cell can require one or more complexes, while each complex can be involved in one or more reactions" [16]. For example, the functional role "Phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase of PTS system (EC 2.7.3.9)" encoded by the ptsI gene in Escherichia coli participates in multiple complexes, each associated with importing different sugars [16]. Databases like the Model SEED provide structured connections between functions, enzyme complexes, reactions, and compounds, facilitating this complex mapping process [16].

Table 2: Common Tools for GSMM Reconstruction and Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyFBA | Metabolic model building and FBA | Extensible Python-based platform; uses Model SEED database | Python [16] |

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | Comprehensive suite of analysis methods; extensive tutorials | MATLAB [19] |

| Model SEED | Automated model reconstruction | Rapid model generation from annotations | Web-based, API [16] |

| RAVEN | Model reconstruction and simulation | Integration with KEGG and MetaCyc; FBA capabilities | MATLAB [3] |

| CarveMe | Automated model reconstruction | Template-based approach; command-line interface | Python |

Network Reconstruction, Gap Filling, and Validation

The converted reactions are assembled into a stoichiometric matrix that forms the mathematical foundation of the model. For example, a Citrobacter model contains "1,399 reactions (columns) and 1,301 compounds (rows)" [16]. This reconstruction process typically reveals gaps in the metabolic network—inability to produce essential biomass components despite annotated genes. Gap filling algorithms address these gaps by adding missing reactions necessary for metabolic functionality, often drawing from universal reaction databases [16]. The final validation phase involves testing whether the model produces biologically realistic predictions under different nutrient conditions, ensuring it can generate appropriate growth yields and byproducts observed in experimental data [16].

Flux Balance Analysis Methodology

Implementing FBA with Genome-Scale Models