Flux Balance Analysis for E. coli Metabolism: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) as a cornerstone constraint-based modeling approach for elucidating Escherichia coli metabolism.

Flux Balance Analysis for E. coli Metabolism: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) as a cornerstone constraint-based modeling approach for elucidating Escherichia coli metabolism. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, methodological workflows, and practical applications, including gene essentiality prediction for antimicrobial discovery. We delve into advanced topics such as model validation, selection frameworks, and the integration of machine learning to overcome traditional FBA limitations. The content also explores troubleshooting common pitfalls and compares FBA with complementary techniques like 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis, offering a holistic guide for employing in silico models to drive innovations in biotechnology and biomedical research.

Understanding the Core Principles and Framework of Flux Balance Analysis in E. coli

Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM) provides a powerful mathematical framework for analyzing metabolic networks without requiring detailed kinetic parameters. By leveraging genomic and biochemical data, CBM enables researchers to predict metabolic behaviors, identify potential drug targets, and engineer microbial strains for biotechnological applications. This technical guide explores the core principles of CBM, with a specific focus on Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and its application to E. coli metabolism research.

Foundational Principles of Constraint-Based Modeling

Constraint-based modeling operates on the fundamental principle that metabolic networks are subject to physical and biochemical constraints that limit their possible behaviors. The most critical constraint is the steady-state condition, which assumes that for each intracellular metabolite, the rate of production equals the rate of consumption, leading to no net accumulation over time [1].

This steady-state condition is mathematically represented using the stoichiometric matrix S, where rows correspond to metabolites and columns represent metabolic reactions. The elements of S are stoichiometric coefficients indicating how many molecules of a metabolite are consumed (negative values) or produced (positive values) in each reaction [1] [2].

The relationship between the stoichiometric matrix and reaction fluxes is described by the equation: d(c)/dt = S · v - μ · c = 0 where c represents metabolite concentrations, v is the vector of metabolic reaction fluxes, and μ is the specific growth rate accounting for dilution by cellular growth [1].

Flux Balance Analysis: Core Methodology

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the most widely used constraint-based approach. FBA calculates the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network by determining feasible flux distributions that optimize a specified cellular objective, typically biomass production [1] [3].

The key steps in implementing FBA include:

- Reconstruction: Compiling all known metabolic reactions for an organism from databases

- Stoichiometric Matrix Construction: Creating the mathematical representation of the network

- Constraint Application: Defining capacity constraints on reaction fluxes

- Objective Optimization: Identifying flux distributions that maximize or minimize a biological objective function [3] [2]

FBA relies on several critical assumptions:

- The system operates at metabolic steady-state

- Metabolic reaction kinetics are not required

- The objective function accurately represents evolutionary pressures

- Enzyme capacities and nutrient uptake rates can be realistically bounded [1]

Metabolic Network Reconstruction forE. coli

E. coli K-12 MG1655 has one of the most extensively curated metabolic reconstructions. The iML1515 genome-scale model includes 1,515 genes, 2,712 metabolic reactions, and 1,192 metabolites, providing a comprehensive representation of E. coli metabolism [4] [3].

For specific applications, reduced models focusing on core metabolism offer advantages in computational efficiency and interpretability. The iCH360 model represents a manually curated "Goldilocks-sized" model of E. coli energy and biosynthesis metabolism, containing all pathways essential for producing energy carriers and biosynthetic precursors [4].

Table: Comparison of E. coli Metabolic Models

| Model Name | Genes | Reactions | Metabolites | Scope | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iML1515 [3] | 1,515 | 2,712 | 1,192 | Genome-scale | Most complete reconstruction; includes all known metabolic genes |

| iCH360 [4] | 360 | 360+ | N/A | Core & biosynthesis | Manually curated; focuses on central energy and biosynthesis pathways |

| ECC2 [4] | N/A | N/A | N/A | Core metabolism | Algorithmically reduced; retains key phenotypic capabilities |

Essential databases for metabolic reconstruction include:

- KEGG: Contains information on genes, proteins, reactions, and pathways [2]

- BioCyc/EcoCyc: Highly detailed databases on E. coli genome and metabolic reconstruction [3] [2]

- BRENDA: Comprehensive enzyme database with kinetic parameters [3]

- BiGG: Knowledge base of biochemically structured genome-scale metabolic reconstructions [2]

Implementation Protocols for FBA

Basic FBA Protocol

The following protocol outlines the steps for implementing Flux Balance Analysis using E. coli metabolic models:

Model Preparation: Obtain a genome-scale metabolic model such as iML1515 or create a context-specific model using tools like COBRApy [3]

Environmental Constraints: Define medium composition by setting bounds on exchange reactions

- Set upper bounds for carbon sources (e.g., glucose: 10 mmol/gDW/h)

- Set lower bounds for essential nutrients (e.g., ammonium, phosphate)

- Constrain oxygen availability for aerobic/anaerobic conditions [3]

Objective Specification: Define the biological objective function

Problem Formulation: Convert to linear programming problem

- Maximize Z = cᵀv (objective function)

- Subject to: S·v = 0 (steady-state constraint)

- And: vlb ≤ v ≤ vub (capacity constraints) [1]

Solution and Analysis: Solve using linear programming algorithms and analyze resulting flux distributions

Advanced Implementation: Enzyme-Constrained FBA

Traditional FBA can predict unrealistically high fluxes. Enzyme-constrained FBA addresses this by incorporating proteomic limitations:

Reaction Splitting: Split reversible reactions into forward and reverse components to assign distinct kcat values [3]

Isoenzyme Handling: Separate reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into independent reactions [3]

Parameter Incorporation:

- Add enzyme molecular weights based on subunit composition from EcoCyc

- Include kcat values from BRENDA database

- Incorporate protein abundance data from PAXdb [3]

Constraint Addition: Implement an overall enzyme mass constraint based on the measured protein fraction of cell mass (e.g., 0.56 for E. coli) [3]

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FBA

| Resource | Type | Function | Application in E. coli Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRApy [3] | Software Package | Python toolbox for constraint-based modeling | Simulating flux distributions; performing FBA |

| ECMpy [3] | Workflow | Adds enzyme constraints to metabolic models | Implementing enzyme-constrained FBA without altering stoichiometric matrix |

| iML1515 [3] | Metabolic Model | Genome-scale reconstruction of E. coli K-12 | Base model for simulating E. coli metabolism |

| BRENDA [3] | Database | Enzyme kinetic parameters | Providing kcat values for enzyme constraints |

| EcoCyc [3] | Database | E. coli genes and metabolism | Curating gene-protein-reaction relationships |

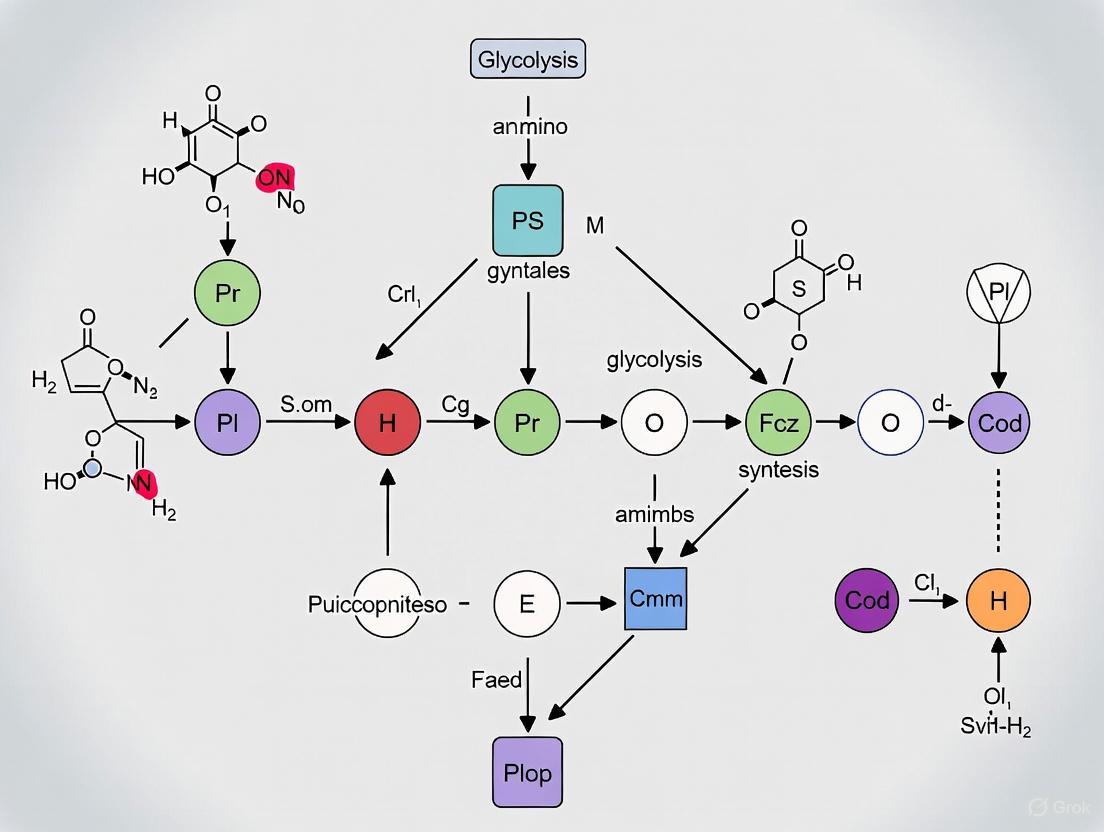

Workflow Visualization: FBA Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for implementing Flux Balance Analysis:

FBA Workflow

Application to Cysteine Overproduction in E. coli

A practical implementation of FBA for metabolic engineering demonstrated the redirection of metabolic flux in E. coli to enhance L-cysteine production [3]. Key modifications to the base iML1515 model included:

Enzyme Kinetic Adjustments:

- Increased kcat value for PGCD reaction from 20/s to 2000/s to reflect removal of feedback inhibition

- Modified SERAT reaction kcat values based on mutant enzyme characteristics

- Added SLCYSS transport reaction with appropriate kcat value [3]

Genetic Modifications:

- Enhanced gene abundance values for SerA and CysE to reflect promoter modifications

- Updated gene-protein-reaction relationships based on EcoCyc database [3]

Medium Optimization:

- Defined specific uptake rates for SM1 + LB medium components

- Included thiosulfate assimilation pathways for enhanced cysteine production

- Blocked serine and cysteine uptake to ensure flux through engineered pathways [3]

The following diagram illustrates the metabolic engineering strategy for cysteine overproduction:

Cysteine Overproduction Pathway

Current Challenges and Emerging Approaches

Despite its widespread application, constraint-based modeling faces several challenges:

Model Quality Dependencies: FBA predictions depend heavily on the quality of metabolic reconstructions, appropriate objective functions, accurate exchange rate constraints, and defined nutrient conditions [1]

Community Modeling Complexities: Extending FBA to microbial communities introduces additional challenges including defining community objective functions and quantifying species-specific exchange rates [1]

Network Complexity: Large metabolic networks often yield underdetermined systems with multiple possible flux distributions, requiring additional constraints to identify biologically relevant solutions [5]

Emerging approaches to address these limitations include:

Integration with Machine Learning: Combining constraint-based models with machine learning to identify patterns in large-scale data and establish causality between genotype and phenotype [6]

Hybrid Modeling: Developing frameworks that incorporate thermodynamic constraints, regulatory networks, and kinetic parameters to refine flux predictions [5]

Condition-Specific Models: Creating context-specific models by integrating transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to tailor networks to particular environmental conditions or genetic backgrounds [7]

These advanced approaches hold promise for enhancing the predictive power of constraint-based models and expanding their applications in basic research and biotechnological engineering.

Defining Mass Balance and Physicochemical Constraints for Metabolic Networks

Constraint-based modeling provides a powerful mathematical framework for analyzing the capabilities and properties of metabolic networks without requiring detailed kinetic parameters. At the heart of this approach lies the application of mass balance and physicochemical constraints to define all possible metabolic behaviors an organism can exhibit. For researchers investigating Escherichia coli metabolism, these constraints enable the simulation of metabolic fluxes under different genetic and environmental conditions, supporting applications from basic physiological research to metabolic engineering and drug development [8]. This technical guide examines the core principles of mass balance and physicochemical constraints, detailing their mathematical formulation and implementation for E. coli metabolism research.

Mathematical Foundation of Mass Balance Constraints

The Stoichiometric Matrix

The fundamental representation of a metabolic network is the stoichiometric matrix S, which mathematically encodes the mass balance relationships for all metabolites in the system. This m × n matrix, where m represents the number of metabolites and n the number of reactions, contains the stoichiometric coefficients of each metabolite in every biochemical reaction [8].

Each column in the stoichiometric matrix represents a biochemical reaction, while each row corresponds to a metabolite. The entries in the matrix are stoichiometric coefficients: negative for metabolites consumed, positive for metabolites produced, and zero for metabolites not involved in a particular reaction [8]. For large-scale metabolic models, S is typically a sparse matrix since most biochemical reactions involve only a few metabolites [8].

Mass Balance Equations

At steady state, the concentration of each metabolite remains constant, meaning the rate of production equals the rate of consumption. This steady-state assumption reduces the system to a set of linear equations represented by the matrix equation:

where v is the vector of metabolic fluxes (reaction rates) through each reaction in the network. This equation formalizes the mass balance constraint, ensuring that for each metabolite, the net sum of its production and consumption across all reactions equals zero [8].

For metabolic networks, the number of reactions (n) typically exceeds the number of metabolites (m), creating an underdetermined system with more variables than equations. Consequently, multiple flux distributions satisfy the mass balance constraints, defining a solution space of possible metabolic behaviors [8] [10].

Flux Bounds and Reaction Reversibility

Additional constraints on the system are implemented as inequalities that define the minimum and maximum allowable fluxes for each reaction:

αᵢ ≤ vᵢ ≤ βᵢ

These bounds incorporate:

- Reaction reversibility: Irreversible reactions are constrained to have non-negative fluxes (αᵢ = 0)

- Transport capabilities: Exchange fluxes with the environment are bounded based on substrate availability and uptake kinetics [9]

- Enzyme capacity: Maximum catalytic rates can be implemented as upper bounds [8]

Table 1: Types of Constraints in Metabolic Models

| Constraint Type | Mathematical Form | Biological Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Balance | Sv = 0 | Conservation of mass; steady-state assumption |

| Reversibility | vᵢ ≥ 0 for irreversible reactions | Thermodynamic feasibility of reaction direction |

| Capacity | vᵢ ≤ vᵢₘₐₓ | Enzyme capacity and substrate availability |

| Thermodynamic | ΔG = ΔG'° + RTlnQ < 0 for forward v | Gibbs free energy relationship for spontaneous direction |

Physicochemical Constraints in Metabolic Networks

Thermodynamic Constraints

While mass balance defines the stoichiometric possibilities, thermodynamic constraints determine the feasible direction of metabolic fluxes. The key thermodynamic quantity is the Gibbs free energy of reaction (ΔG), which must be negative for a reaction to proceed spontaneously in the forward direction [11] [12].

For biochemical reactions, the transformed Gibbs free energy (ΔG') accounts for pH and metal ion binding, calculated as:

ΔG' = ΔG'° + RTlnQ

where ΔG'° is the standard transformed Gibbs free energy, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, and Q is the mass-action ratio (product-to-reactant ratio) [11]. The relationship between thermodynamics and flux direction is formalized through the flux-force relationship:

ΔG' = -RTln(J₊/J₋)

where J₊ and J₋ represent the forward and backward fluxes, respectively [11].

Thermodynamics-Based Flux Analysis (TFA)

Thermodynamics-Based Flux Analysis incorporates thermodynamic constraints directly into flux balance analysis, transforming the problem into a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) formulation [11]. TFA ensures that the predicted flux distribution is thermodynamically feasible by:

- Constraining reaction directions based on Gibbs free energy values

- Incorporating metabolite concentration ranges when available

- Using group contribution methods to estimate standard Gibbs free energies for reactions [11]

Compartmentalization and Transport Thermodynamics

Metabolic networks in organisms like E. coli involve multiple compartments with different physicochemical conditions. The thermodynamic description of cross-membrane transport must account for both concentration gradients and electrochemical potential [12]. For a transport process, the Gibbs free energy includes an electrochemical term:

ΔG_transport = RTln(Cᵢₙ/Cₒᵤₜ) + FΔϕ∑zᵢ

where F is Faraday's constant, Δϕ is the membrane potential, and zᵢ is the charge of the transported species [12]. This formulation is essential for correctly modeling transport processes in genome-scale metabolic networks.

Implementation and Computational Tools

Flux Balance Analysis Methodology

Flux Balance Analysis utilizes linear programming to identify an optimal flux distribution within the constrained solution space. The complete FBA formulation is:

Maximize Z = cᵀv Subject to: Sv = 0 αᵢ ≤ vᵢ ≤ βᵢ

where Z is the objective function, typically representing biomass production, ATP synthesis, or product formation [8] [10]. The vector c contains weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the objective function [8].

Table 2: Common Objective Functions in E. coli FBA

| Objective Function | Biological Interpretation | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Production | Maximize growth rate | Simulating cellular growth in different conditions |

| ATP Production | Maximize energy generation | Analyzing energy metabolism and maintenance |

| Product Synthesis | Maximize metabolite production | Metabolic engineering for chemical production |

| Flux Minimization | Minimize total flux (∑|vᵢ|) | Simulating metabolic efficiency (principle of parsimony) |

Workflow for Metabolic Network Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the sequential process of building and analyzing a constraint-based metabolic model:

Software and Toolkits

Several computational tools implement constraint-based analysis for metabolic networks:

- COBRA Toolbox: A MATLAB-based toolbox for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis [8]

- Escher-FBA: A web application for interactive FBA simulations with visualization capabilities [13]

- matTFA: A MATLAB toolbox for thermodynamics-based flux analysis [11]

These tools enable researchers to simulate gene knockouts, predict growth phenotypes, and identify potential drug targets by systematically manipulating the constraint structure [8] [13].

Experimental Protocols for E. coli Metabolic Studies

Purpose: To predict E. coli growth capabilities on different carbon substrates using FBA [13].

- Load a core E. coli metabolic model (e.g., the core E. coli model from BiGG Models)

- Set the objective function to maximize biomass production

- Constrain the glucose uptake rate to zero (knockout or set lower bound to 0)

- Set the uptake rate for the alternative carbon source (e.g., succinate) to a physiological value (e.g., -10 mmol/gDW/hr)

- Solve the linear programming problem to obtain the optimal growth rate

- Compare the predicted growth rate with the glucose baseline (typically 0.874 h⁻¹ for core models)

Expected Outcome: Prediction of whether growth is possible on the alternative carbon source and the maximum theoretical growth rate [13].

Protocol 2: Simulating Anaerobic Growth Conditions

Purpose: To predict metabolic changes in E. coli under anaerobic conditions [8] [13].

- Load the E. coli metabolic model with aerobic glucose minimal medium conditions

- Set the oxygen exchange reaction lower and upper bounds to zero (EXo2e = 0)

- Maintain glucose uptake at a physiological level (e.g., -10 mmol/gDW/hr)

- Maximize biomass production using linear programming

- Analyze the resulting flux distribution, particularly noting:

- Increased fermentative pathways (e.g., lactate, ethanol, formate production)

- Reduced TCA cycle activity

- Lower predicted growth rate compared to aerobic conditions

Expected Outcome: Prediction of anaerobic growth rate (typically ~0.211 h⁻¹ for core models) and identification of necessary metabolic adaptations [13].

Protocol 3: Gene Essentiality Analysis

Purpose: To identify metabolic genes essential for growth under specific conditions [9].

- Set up the base case simulation with desired medium conditions

- For each gene in the model:

- Constrain all reactions catalyzed by the gene to zero flux

- Solve the FBA problem with biomass maximization

- Record the resulting growth rate

- Classify genes as:

- Essential: Growth rate < threshold (e.g., <5% of wild-type)

- Non-essential: Growth rate ≥ threshold

- Validate predictions with experimental gene essentiality data when available

Expected Outcome: Identification of condition-specific essential genes, potential drug targets, and synthetic lethal interactions [9].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for E. coli Metabolism Research

| Resource | Type | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [8] | Software Toolbox | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling and FBA |

| Escher-FBA [13] | Web Application | Interactive FBA with visualization capabilities, no installation required |

| Core E. coli Model [14] | Metabolic Model | Curated model of central E. coli metabolism for educational and research use |

| BiGG Models Database [13] | Model Repository | Access to curated genome-scale metabolic models for multiple organisms |

| SBML Format [8] | Data Standard | Systems Biology Markup Language for model exchange between tools |

| GLPK Solver [13] | Computational | Linear programming solver used in various FBA implementations |

Advanced Concepts and Applications

Relationships Between Modeling Approaches

The field of fluxomics employs multiple approaches for determining metabolic fluxes, each with distinct capabilities and limitations as shown in the following conceptual relationship diagram:

Phenotypic Phase Planes

Phenotypic Phase Plane (PhPP) analysis explores how optimal metabolic phenotypes change with variations in two environmental parameters (e.g., carbon and oxygen uptake rates) [9]. PhPP analysis identifies regions of constant metabolic pathway utilization separated by sharp phase boundaries, providing insights into optimal metabolic strategies across environmental conditions.

Metabolic Engineering Applications

FBA with mass balance constraints enables metabolic engineering strategies through:

- OptKnock: Identifying gene knockouts that couple growth with product formation [8]

- Robustness Analysis: Determining how objective function values change with variations in reaction fluxes [8]

- Gap-Filling: Predicting missing reactions in metabolic networks by comparing simulations with experimental data [8]

Mass balance and physicochemical constraints provide the foundational principles for constraint-based modeling of metabolic networks. For E. coli researchers, these constraints enable predictive simulations of metabolic behavior under various genetic and environmental conditions. The continuing development of more sophisticated constraint implementations, particularly incorporating thermodynamic and regulatory information, promises to enhance the predictive accuracy and applications of these approaches in basic research and drug development.

The Role of the Biomass Objective Function in Simulating Growth

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has emerged as a powerful mathematical framework for predicting metabolic behavior from genome-scale reconstructions. Central to this constraint-based approach is the Biomass Objective Function (BOF), a pseudo-reaction that quantitatively represents the biosynthetic requirements for cellular growth. This technical guide examines the formulation, implementation, and application of the BOF within the context of Escherichia coli metabolism research. We detail the multi-level process of BOF development from basic macromolecular composition to advanced formulations incorporating cofactors and condition-specific elements. Protocol descriptions for experimental and computational BOF determination are provided, along with analysis of how BOF variations impact flux predictions. For researchers in metabolic engineering and drug development, understanding BOF principles is essential for accurate simulation of microbial growth, prediction of gene essentiality, and identification of potential therapeutic targets.

Flux Balance Analysis is a constraint-based modeling approach that calculates the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network at steady state [8]. FBA has become a cornerstone method for analyzing genome-scale metabolic reconstructions, which contain all known metabolic reactions of an organism and their associated genes [15]. The mathematical foundation of FBA represents metabolic reactions as a stoichiometric matrix S of size m×n, where m represents metabolites and n represents reactions. The system of mass balance equations at steady state is represented as Sv = 0, where v is the vector of reaction fluxes [8].

Because metabolic networks typically contain more reactions than metabolites (n > m), the system is underdetermined, yielding a solution space of possible flux distributions rather than a unique solution [8] [10]. To identify a biologically relevant flux distribution within this space, FBA employs linear programming to optimize an objective function. The Biomass Objective Function serves as this objective in growth simulations, representing the rate at which biomass precursors are converted into cellular constituents in the correct proportions [15]. The BOF is mathematically represented as a drain of necessary metabolic precursors from the system, with the flux through this biomass reaction corresponding to the exponential growth rate (μ) of the organism [8]. The canonical FBA problem with a BOF can be formulated as:

Maximize: c^Tv Subject to: Sv = 0 and: lower bound ≤ v ≤ upper bound

where c is a vector of weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the objective function, typically zeros with a one at the position of the biomass reaction [8] [10].

Fundamental Principles of the Biomass Objective Function

Mathematical and Biological Basis

The Biomass Objective Function is fundamentally a mathematical representation of the metabolic investment required for cellular replication. It encapsulates the stoichiometric requirements for synthesizing all essential cellular components in their appropriate proportions [15]. When FBA computes a flux distribution that maximizes the flux through this BOF, it essentially predicts a metabolic state supporting optimal growth under the specified constraints [8].

The formulation of a detailed BOF requires comprehensive knowledge of cellular composition and the energetic requirements for generating this biomass from metabolic precursors [15]. This includes information about:

- Macromolecular content (proteins, RNA, DNA, lipids, carbohydrates)

- Building block composition (amino acids, nucleotides, fatty acids)

- Cofactors and inorganic ions

- Growth-associated maintenance energy requirements

The BOF allows for computation of both biomass yields (maximum amount of biomass per unit substrate) and actual growth rates when constrained by measured substrate uptake rates and maintenance requirements [15]. The yield calculation lacks a time dimension, while growth rate prediction incorporates time through substrate uptake constraints.

Formulation Levels

Biomass Objective Functions can be formulated at different levels of complexity and resolution:

Basic Level The process begins with defining the macromolecular content of the cell (weight fractions of protein, RNA, lipid, etc.) and then determining the metabolites that constitute each macromolecular class [15]. This information enables calculation of the required amounts of metabolic precursors along with associated carbon, nitrogen, and other elemental requirements.

Intermediate Level At this level, the biosynthetic energy requirements for polymerizing building blocks into macromolecules are incorporated [15]. For example, approximately 2 ATP and 2 GTP molecules are required to drive the polymerization of each amino acid into a protein [15]. The BOF also includes products of macromolecular biosynthesis (e.g., water from protein synthesis and diphosphate from nucleic acid synthesis), which become available to the cell and reduce resource uptake requirements.

Advanced Level Advanced BOF formulations include vitamins, essential elements, cofactors, and other components necessary for growth [15]. Another sophisticated approach involves creating a "core" BOF containing minimally functional cellular content, formulated using experimental data from genetic mutants to improve predictions of gene, reaction, and metabolite essentiality [15].

Table 1: Components of a Comprehensive Biomass Objective Function

| Component Category | Specific Elements | Contribution Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Macromolecules | Proteins, RNA, DNA, Lipids, Carbohydrates | Cellular weight fractions |

| Building Blocks | Amino acids, Nucleotides, Fatty acids, Sugars | Macromolecular composition |

| Cofactors | ATP, NADH, NADPH, Coenzyme A | Polymerization energy requirements |

| Inorganic Ions | Potassium, Phosphate, Ammonia, Sulfate | Elemental composition analysis |

| Species-Specific | Cell wall components, Compatible solutes | Organism-specific literature |

Formulation Methodologies

Workflow for BOF Development

The development of a species-specific Biomass Objective Function follows a systematic workflow that integrates experimental data with computational modeling. BOFdat provides a standardized Python package that divides this process into three modular steps [16]:

- Calculation of major macromolecule coefficients based on experimental measurements of cellular composition

- Identification of coenzymes and inorganic ions with estimation of their stoichiometric coefficients

- Algorithmic extraction of species-specific metabolic precursors from experimental data in an unbiased manner

This data-driven approach represents a significant advancement over traditional methods that often default to copying BOF formulations from well-characterized organisms like E. coli without sufficient species-specific validation [16].

Experimental Determination of Biomass Composition

Accurate BOF formulation requires extensive experimental data on cellular composition. The following protocols describe key methodologies for gathering these essential data:

Protocol 1: Macromolecular Composition Analysis

- Purpose: Determine weight fractions of major macromolecular classes (protein, RNA, DNA, lipids, carbohydrates) in E. coli biomass

- Materials:

- Luria-Bertani (LB) or defined minimal media

- Spectrophotometer for optical density measurements

- Centrifuge for cell harvesting

- Protein assay kit (e.g., Bradford or BCA)

- RNA/DNA extraction kits and quantification methods

- Lipid extraction solvents (chloroform-methanol) and gravimetric analysis

- Procedure:

- Grow E. coli culture to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5)

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and wash with phosphate-buffered saline

- Divide cell pellet into aliquots for different analyses

- Quantify protein content using colorimetric assays against bovine serum albumin standard

- Extract and quantify RNA/DNA using UV spectrophotometry or fluorometric methods

- Extract lipids using Folch method and determine mass gravimetrically

- Calculate carbohydrates as difference or use specific assays

- Normalize all measurements to cellular dry weight

Protocol 2: Building Block Stoichiometry Determination

- Purpose: Establish molar coefficients of amino acids, nucleotides, and fatty acids in biomass

- Materials:

- Acid hydrolysis reagents (6M HCl for amino acids)

- Nuclease enzymes for nucleic acid digestion

- High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system

- Appropriate separation columns and standards

- Procedure:

- Hydrolyze cellular protein with 6M HCl at 110°C for 24 hours

- Derivatize amino acids for detection and separation by HPLC

- Digest nucleic acids with benzonase or similar nuclease

- Separate nucleotides by HPLC with UV detection

- Extract and transesterify fatty acids for gas chromatography analysis

- Calculate molar ratios of all building blocks

- Convert to mmol/gDW for incorporation into BOF

Protocol 3: Growth-Associated Maintenance Energy Determination

- Purpose: Quantify ATP requirements for biomass synthesis beyond precursor formation

- Materials:

- Chemostat culture system

- Substrate limitation media (carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus limited)

- Metabolite analysis kits (ATP, ADP, NADH, etc.)

- Procedure:

- Grow E. coli in chemostat at multiple dilution rates

- Measure substrate consumption and biomass production at steady state

- Calculate maintenance coefficients from linear relationship between substrate consumption and growth rate

- Incorporate as ATP hydrolysis reaction in metabolic model

Computational Implementation

Integration with Metabolic Models

The formulated Biomass Objective Function is integrated into genome-scale metabolic models as a dedicated biomass reaction. For E. coli, this implementation has evolved through successive model generations (iJR904, iAF1260, iJO1366, iML1515), each with refined BOF formulations [17]. The COBRA (Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) Toolbox provides a standardized MATLAB environment for implementing FBA with BOF optimization [8].

The biomass reaction is structured to convert precursors into biomass while accounting for polymerization costs. A key consideration is the difference between biomass yield calculations (maximum biomass per unit substrate) and growth rate predictions (influenced by substrate uptake constraints and maintenance requirements) [15].

Table 2: Comparison of BOF Formulations in E. coli Metabolic Models

| Model | Genes | Reactions | BOF Specificity | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iJR904 | 904 | 931 | Standard | Early genome-scale BOF |

| iAF1260 | 1,260 | 2,077 | Detailed | Includes core and wild-type BOF variants |

| iJO1366 | 1,366 | 2,413 | Condition-responsive | Expanded cofactor coverage |

| iML1515 | 1,515 | 2,712 | Advanced | Gold standard for BOFdat validation [16] |

| iCH360 | 360 | 484 | Compact | Manually curated core metabolism [4] |

Advanced Formulations and Alternatives

While standard BOF formulations assume fixed proportions of biomass components, advanced approaches introduce flexibility to better reflect biological reality:

flexFBA incorporates flexible objectives that remove fixed proportionality between biomass reactants, enabling production of biomass component subsets [18]. This approach is particularly valuable for simulating metabolic states during transitions or stress conditions.

PSEUDO (Perturbed Solution Expected Under Degenerate Optimality) accounts for solution degeneracy in FBA by considering a region of near-optimal flux configurations rather than a single optimal point [19]. This method drives mutant metabolism toward a degenerate optimal region defined by fluxes achieving at least 90% of maximal growth rate, improving prediction accuracy for metabolic mutants.

Core BOF formulations represent the minimal functional cellular content rather than wild-type composition, enhancing predictions of gene essentiality and network vulnerability [15].

Applications in E. coli Research

Metabolic Engineering

The BOF enables computational prediction of growth phenotypes under genetic and environmental perturbations, forming the foundation for model-guided metabolic engineering. In E. coli, BOF-based FBA has successfully guided strain design for overproduction of valuable compounds including [17]:

- Lycopene (2-fold production increase through predicted gene knockouts)

- L-Threonine (industrial titers through optimal enzyme activity tuning)

- Ethanol, succinic acid, and lactic acid

- Amino acids (L-valine, L-threonine)

These applications typically combine FBA with additional algorithms such as OptKnock that identify gene deletion strategies coupling growth with product formation [8].

Gene Essentiality Prediction

BOF formulation critically impacts accuracy in predicting essential genes. When simulating gene knockouts, reactions are constrained to zero flux based on gene-protein-reaction relationships, and the model's ability to maintain biomass production is assessed [10]. The "core" BOF approach has demonstrated improved essentiality predictions by representing minimal rather than typical cellular composition [15].

Drug Target Identification

For drug development, BOF-enabled FBA identifies metabolic vulnerabilities in pathogens. Essential genes predicted through in silico gene deletion studies represent potential drug targets [10]. Double deletion analysis further identifies synthetic lethal gene pairs that represent combinatorial targets with reduced likelihood of resistance development.

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Sensitivity to BOF Composition

Studies examining flux prediction sensitivity to BOF variations reveal that central metabolic fluxes in E. coli remain relatively stable despite changes in biomass composition [20]. However, model structure significantly influences flux predictions, with different Arabidopsis models showing substantial variation despite identical BOF formulations [20]. This highlights the importance of both accurate BOF formulation and correct network reconstruction.

Condition-Specific Variations

Cellular composition varies with growth conditions, growth rate, and nutrient availability [16]. The ratios between DNA, RNA, and proteins change with growth rate and nutrient availability, while cellular volume impacts total cell weight and component proportions [16]. These variations necessitate condition-specific BOF formulations for accurate predictions, achievable through tools like BOFdat that integrate omics datasets [16].

Resolution of Biomass Representation

A fundamental limitation in BOF formulation is the degree of detail in biomass representation. While some models include detailed lipid species and complex macromolecular structures, others employ lumped reactions for biomass synthesis [4]. The iCH360 model, for example, uses a compact biomass-producing reaction while focusing detailed representation on energy and precursor metabolism [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for BOF Development

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Software | MATLAB-based FBA implementation | Simulating growth on different substrates [8] |

| BOFdat | Python package | Data-driven BOF generation | Creating species-specific BOF from omics data [16] |

| SBML | Format | Systems Biology Markup Language | Model exchange between platforms [20] |

| Gurobi Optimizer | Solver | Linear programming solver | Solving FBA optimization problems [20] |

| Defined Media | Reagent | Controlled nutrient environment | Measuring substrate-specific biomass yields |

| HPLC Systems | Instrument | Metabolite separation and quantification | Determining amino acid composition |

| Gene Knockout Collections | Biological | Comprehensive mutant libraries | Validating gene essentiality predictions |

The Biomass Objective Function serves as the crucial link between metabolic network structure and cellular growth predictions in constraint-based modeling. Its careful formulation requires integration of experimental data on cellular composition with computational methods for stoichiometric representation. For E. coli researchers, continued refinement of BOF formulations—incorporating condition-specific variations, flexible objectives, and minimal functional representations—enhances predictive accuracy for metabolic engineering, drug target identification, and fundamental studies of microbial physiology. As metabolic modeling expands to include more complex cellular processes, the BOF will remain foundational for translating genomic information into phenotypic predictions.

Diagram Appendix

Diagram 1: The Core FBA Framework with BOF. This diagram illustrates how the Biomass Objective Function integrates with other components of Flux Balance Analysis to predict growth. Experimental data informs BOF formulation, which then serves as the optimization target within the constraint-based model defined by the stoichiometric matrix and flux boundaries.

Diagram 2: BOF Development Workflow. This workflow outlines the multi-step process for developing and validating a species-specific Biomass Objective Function, showing how diverse experimental data sources contribute to BOF formulation and subsequent model validation.

Linear Programming for Solving and Optimizing Metabolic Flux Distributions

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a mathematical method for simulating metabolism of cells or entire unicellular organisms, such as E. coli, using genome-scale reconstructions of metabolic networks [10]. These reconstructions describe all biochemical reactions in an organism based on its entire genome, modeling metabolism by focusing on interactions between metabolites and the genes that encode enzymes which catalyze these reactions [10]. FBA has become a central tool in systems biology for analyzing cellular metabolism [21] [22], finding applications in bioprocess engineering to systematically identify modifications to metabolic networks that improve product yields of industrially important chemicals [10], as well as in drug target identification [10] and host-pathogen interactions [23] [10].

The fundamental principle of FBA is the application of linear programming to solve underdetermined systems of metabolic equations under the constraints of steady-state metabolism and evolutionary optimality [24] [10]. Unlike traditional kinetic modeling approaches that require extensive parameterization, FBA requires relatively little information in terms of enzyme kinetic parameters and metabolite concentrations, making it particularly valuable for genome-scale simulations [25] [10]. This approach transforms the complex problem of predicting metabolic flux distributions into a tractable linear optimization problem that can be solved efficiently even for large metabolic networks [10].

Mathematical Foundations of FBA

Core Mathematical Framework

The mathematical foundation of FBA begins with the representation of a metabolic network as a stoichiometrically balanced set of equations. The system is formalized through the stoichiometric matrix S, where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions [24] [10]. The steady-state assumption, which states that metabolite concentrations remain constant as rates of production and consumption balance each other, reduces the system to a set of linear equations [10]:

[ S \cdot v = 0 ]

where (v) is the vector of metabolic fluxes [10]. This equation represents the mass balance constraint for each metabolite in the network, ensuring that the net flux producing and consuming each metabolite equals zero at steady state [24] [10].

Metabolic networks typically contain more reactions than metabolites, resulting in an underdetermined system with more variables than equations [10]. To solve this system, FBA applies linear programming with biological constraints and an objective function. The canonical form of the FBA linear programming problem is [10]:

[ \begin{align} \text{maximize } & c^T v \ \text{subject to } & S \cdot v = 0 \ \text{and } & \text{lower bound} \leq v \leq \text{upper bound} \end{align} ]

where (c) is a vector of coefficients defining the objective function, typically representing biomass production or other biological objectives [10]. The constraints on upper and lower bounds for individual fluxes enforce thermodynamic irreversibility and capacity constraints [24].

Key Assumptions in FBA

FBA relies on two fundamental assumptions [10]:

Steady-state metabolism: The model assumes that the cellular system has reached a steady state where metabolite concentrations remain constant over time. This assumption simplifies the system to linear algebra and eliminates the need for kinetic parameters [10].

Optimality principle: The model assumes the organism has been optimized through evolution for a specific biological goal, represented by the objective function. For prokaryotes such as E. coli, maximal growth performance (biomass production) is often selected as the objective [24] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of FBA, from network reconstruction to flux prediction:

FBA Workflow: From Network Reconstruction to Flux Prediction

Table 1: Components of the FBA Linear Programming Problem

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | (S_{m \times n}) | Quantitative relationships between metabolites (m) and reactions (n) |

| Flux Vector (v) | (v = [v1, v2, ..., v_n]^T) | Rates of all metabolic reactions |

| Mass Balance Constraints | (S \cdot v = 0) | Metabolic steady state for all intracellular metabolites |

| Capacity Constraints | (\alphaj \leq vj \leq \beta_j) | Thermodynamic and enzyme capacity limitations |

| Objective Function | (Z = c^T v) | Biological objective (e.g., biomass maximization) |

Practical Implementation forE. coliMetabolism

Model Reconstruction and Constraints

For E. coli metabolism, implementation begins with a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction. The reconstruction by Edwards and Palsson provides a comprehensive model with 436 metabolites and 720 fluxes, encompassing central carbon metabolism, transmembrane transport reactions, carbon source utilization pathways, and metabolic pathways for synthesis and degradation of amino acids, nucleic acids, vitamins, cofactors, and lipids [24].

Implementation requires several key steps [24] [23]:

Stoichiometric matrix formulation: The stoichiometric matrix S is constructed with metabolites as rows and reactions as columns, with stoichiometric coefficients indicating how many molecules of each metabolite are consumed (negative values) or produced (positive values) in each reaction [24].

Flux constraints: Additional constraints are implemented as inequalities ((\alphaj \leq vj \leq \beta_j)) to [24]:

- Limit nutrient uptake based on experimental measurements

- Implement reaction irreversibility ((\alpha_j = 0) for irreversible reactions)

- Include maintenance requirements

Biomass objective function: Biomass production is represented as an additional flux ((v{gro})) with stoichiometric factors ((ci)) representing the proportions of metabolite precursors (Xi) contributing to biomass [24]: [ \sum ci X_i \rightarrow \text{Biomass} ]

Computational Tools and Implementation

FBA implementation typically utilizes linear programming solvers. The GNU Linear Programming Kit (GLPK) provides an open-source option, while commercial alternatives like Gurobi or CPLEX offer enhanced performance for large models [24] [23]. The following table summarizes essential computational tools and resources for FBA implementation:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for FBA Implementation

| Resource Type | Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Databases | KEGG, EcoCyc, BiGG, MetaNetX | Provide curated metabolic pathway information and standardized nomenclature |

| Model Reconstruction Tools | ModelSEED, CarveMe, RAVEN, AuReMe | Generate draft metabolic models from genomic data |

| Linear Programming Solvers | GLPK, Gurobi, IBM CPLEX | Solve the optimization problem to obtain flux distributions |

| E. coli Specific Resources | AGORA, BiGG Models, EcoCyc | Provide organism-specific curated metabolic models |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Suites | COBRA Toolbox, FlexFlux | Offer integrated environments for constraint-based modeling |

Advanced Methodological Extensions

Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA)

For mutant strains that haven't undergone evolutionary optimization, the assumption of optimal growth may not hold. The Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) approach addresses this by identifying a flux distribution in the mutant that is closest to the wild-type configuration rather than optimal for growth [24].

MOMA employs quadratic programming to minimize the Euclidean distance between the wild-type flux vector ((v_{WT})) and the mutant flux vector ((x)) [24]:

[ \begin{align} \text{minimize } & D = \lVert x - v_{WT} \rVert \ \text{subject to } & S \cdot x = 0 \ \text{and } & x_j = 0 \text{ for knockout reaction } j \ \text{and } & \alpha \leq x \leq \beta \end{align} ]

This approach can be reformulated as a standard quadratic programming problem [24]:

[ \text{minimize } \frac{1}{2} x^T Q x + L^T x ]

where (Q) is an (N \times N) identity matrix and (L = -v_{WT}) [24]. Experimental validation has shown that MOMA predictions display significantly higher correlation with experimental flux data than standard FBA for pyruvate kinase mutants in E. coli [24].

The conceptual relationship between FBA and MOMA is illustrated below:

FBA vs. MOMA: Conceptual Approach for Mutant Strains

Dynamic and Regulatory Extensions

Several advanced extensions to basic FBA address its limitations:

Dynamic FBA (dFBA): Extends FBA to dynamic conditions by incorporating time-dependent changes in extracellular metabolites and constraints [25].

Regulatory FBA (rFBA): Integrates Boolean logic-based regulatory rules with metabolic constraints to account for gene regulation effects on metabolic states [21] [22].

Linear Kinetics-Dynamic FBA (LK-DFBA): A recently developed approach that incorporates metabolite dynamics and regulation while maintaining a linear programming structure, enabling integration of metabolomics data without the computational complexity of nonlinear models [25].

Objective Function Identification

Traditional FBA relies on predefined objective functions (typically biomass maximization). The TIObjFind framework addresses this limitation by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to systematically infer metabolic objectives from experimental data [21] [22]. This approach:

- Determines Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to cellular objectives [21] [22]

- Maps FBA solutions onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG) for pathway-based interpretation [21] [22]

- Applies a minimum-cut algorithm to extract critical pathways and compute pathway-specific weights [21] [22]

Experimental Validation through 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis

Principles of 13C-MFA

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is considered the gold standard for experimental validation of FBA predictions [26] [27]. This approach uses stable isotope tracers (specifically 13C-labeled substrates) to empirically determine intracellular metabolic fluxes [28] [26].

The experimental workflow involves [28] [26]:

- Tracer experiment: Growing cells on specifically 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose)

- Mass spectrometry: Measuring the mass isotope distribution of metabolites or proteinogenic amino acids

- Flux estimation: Using computational methods to estimate fluxes that best fit the measured labeling patterns

Computational Approaches in 13C-MFA

Two main computational approaches exist for interpreting 13C labeling data [28]:

Global isotopomer balancing: Estimates fluxes by iteratively generating candidate flux distributions until they fit the experimental 13C labeling data [28]. Implemented in tools like 13C-FLUX and OpenFLUX, this approach is computationally demanding but provides comprehensive flux maps [28].

Metabolic flux ratio analysis (METAFoR): Uses probabilistic equations to constrain flux ratios based on local labeling patterns, implemented in FiatFlux software [28]. This approach is less computationally intensive but cannot calculate exchange fluxes in reversible reactions [28].

Recent advances aim to automate 13C-MFA through workflow systems like Flux-P, enabling high-throughput flux analysis with minimal user intervention [28].

Integration with FBA

13C-MFA and FBA serve complementary roles in metabolic flux analysis [26] [27]:

- FBA predicts metabolic capabilities and optimal flux distributions based on stoichiometric constraints and assumed objectives [26]

- 13C-MFA provides experimental validation and refinement of FBA predictions, with recent advances enabling genome-scale 13C-MFA (GS-MFA) for more comprehensive flux mapping [27]

The integration of these approaches provides a powerful framework for understanding and engineering cellular metabolism, particularly in model organisms like E. coli where extensive experimental validation is possible [26] [27].

Applications inE. coliResearch

FBA and its extensions have been successfully applied to various aspects of E. coli metabolism research:

Gene essentiality prediction: Systematically identifying reactions critical for biomass production through single and double reaction deletion studies [10]

Metabolic engineering: Guiding strain optimization for production of valuable chemicals by predicting gene knockout targets and pathway modifications [26] [10]

Phenotype prediction: Accurately predicting growth capabilities under different nutrient conditions and genetic backgrounds [24] [10]

Host-microbe interactions: Modeling metabolic interactions between E. coli and human hosts, particularly relevant for understanding pathogenic strains [23]

Validation studies have demonstrated excellent agreement between FBA predictions and intracellular flux data for wild-type E. coli JM101, supporting the assumption of optimality in naturally evolved strains [24]. For engineered mutants, MOMA has proven superior to FBA in predicting flux distributions, reflecting the suboptimal metabolic states of strains not subjected to long-term evolutionary pressure [24].

Key Historical Developments and the E. coli In Silico Model

The pursuit of a complete computational model of a living cell represents a grand challenge in systems biology. Over four decades ago, Francis Crick envisioned a coordinated worldwide scientific effort to determine a "complete solution" of Escherichia coli [29]. While such a centralized approach was never fully realized, the scientific community has made significant strides through published measurements characterizing E. coli physiology. A modern interpretation of Crick's vision calls whole-cell simulation a "grand challenge of the 21st century," recognizing that "complex behavior of the cell cannot be determined or predicted unless a computer model of the cell is constructed and computer simulation is undertaken" [29].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has emerged as a cornerstone mathematical framework for modeling metabolic networks at the genome scale [9] [30]. This constraint-based approach enables researchers to simulate metabolic flux distributions by leveraging stoichiometric models of metabolic networks, physicochemical constraints, and optimization principles [31]. The development of E. coli in silico models represents a paradigmatic case study in the evolution of constraint-based modeling, demonstrating how iterative model refinement can enhance predictive accuracy and biological insight [31] [32].

This technical guide examines key historical developments in E. coli metabolic modeling, details core principles of flux balance analysis, provides experimental protocols for model implementation, and explores cutting-edge applications in drug discovery and metabolic engineering.

Historical Development of E. coli Metabolic Models

The construction of constraint-based E. coli models has followed an iterative refinement process over more than thirteen years, with successive generations expanding in scope and predictive capability [31]. This progression mirrors advances in genome annotation, biochemical characterization, and computational methodologies.

Table: Historical Progression of E. coli Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

| Model Name | Publication Year | Number of Metabolic Reactions | Number of Metabolites | Key Advances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majewski and Domach | 1990 | 14 | 17 | Early stoichiometric model |

| Varma and Palsson | 1993-1995 | 146 | 118 | Catabolic and biosynthetic networks |

| Pramanik and Keasling | 1997-1998 | 300 (317) | 289 (305) | Expanded reaction coverage |

| Edwards and Palsson | 2000 | 720 | 436 | Genome-scale coverage |

| Reed and Palsson | 2003 | 929 | 626 | Enhanced gene-protein-reaction associations |

| iJR904 | 2003 | 931 | 625 | Improved phenotypic prediction |

| iAF1260 | 2007 | 1,079 | 783 | Incorporation of thermodynamic data |

| iJO1366 | 2011 | 1,137 | 1,805 | Expanded transport and catabolic pathways |

| iML1515 | 2017 | 1,515 | 1,172 | Updated gene annotations; improved accuracy |

The EcoCyc–18.0–GEM model represents a significant milestone as a constraint-based model automatically generated from the EcoCyc database using MetaFlux software [33]. This model encompasses 1,445 genes, 2,286 unique metabolic reactions, and 1,453 unique metabolites, achieving an accuracy of 95.2% in predicting growth phenotypes of experimental gene knockouts and 80.7% accuracy in predicting nutrient utilization across 431 different conditions [33].

More recently, the E. coli whole-cell modeling project has sought to create the most detailed computational model of an E. coli cell, currently incorporating functions for 43% of characterized genes [29]. This model represents a significant advance beyond earlier whole-cell modeling efforts with Mycoplasma genitalium, featuring parameters derived entirely from E. coli measurements, capabilities for simulation in multiple environments, and progression from parent to daughter cells over multiple division events [29].

Core Principles of Flux Balance Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis is a constraint-based modeling approach that predicts metabolic flux distributions by leveraging stoichiometric models of metabolic networks, physicochemical constraints, and optimization principles [9] [31]. The mathematical foundation of FBA rests on mass balance constraints that can be represented in matrix form as:

S • v = 0

Where S is an m×n stoichiometric matrix (m metabolites and n reactions), and v is a vector of reaction fluxes [9] [31]. This equation formalizes the assumption that metabolic concentrations remain constant at steady state, meaning the total production and consumption of each metabolite must balance.

Additional physiological constraints bound the solution space:

αᵢ ≤ vᵢ ≤ βᵢ

Where αᵢ and βᵢ represent lower and upper bounds respectively for each flux vᵢ [9]. These constraints enforce reaction reversibility/irreversibility and incorporate measured uptake rates or enzyme capacities.

FBA identifies an optimal flux distribution from the feasible solution space using linear programming to maximize or minimize a specified cellular objective [9]. The most common objective function is biomass production, representing cellular growth:

Maximize Z = cᵀv

Where Z represents the objective function, and c is a vector of coefficients that selects a linear combination of metabolic fluxes [9]. For biomass maximization, c is typically a unit vector in the direction of the biomass reaction.

Diagram: The Flux Balance Analysis Workflow. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of constraint-based metabolic modeling, from genome annotation to model validation and refinement.

Experimental Protocols for FBA Implementation

Purpose: To predict whether growth can occur on alternate carbon substrates and calculate maximum growth rates [13].

Methodology:

- Load a core metabolic model of E. coli (e.g., the core model of central glucose metabolism in E. coli K-12 MG1655)

- Identify the exchange reactions for the default carbon source (e.g., D-glucose, EXglce) and the alternative carbon source (e.g., succinate, EXsucce)

- Modify the lower bound of the alternative carbon source exchange reaction to an experimentally realistic uptake rate (e.g., -10 mmol/gDW/hr)

- Constrain the default carbon source exchange reaction by setting its lower bound to zero (effectively knocking out glucose uptake)

- Maintain the objective function as biomass maximization

- Solve the linear programming problem to calculate the maximum growth rate

Expected Results: Growth yield on succinate (0.398 h⁻¹) will be significantly lower than on glucose (0.874 h⁻¹), reflecting the metabolic efficiency differences between these carbon sources [13].

Protocol 2: Simulating Anaerobic Growth Conditions

Purpose: To predict metabolic capabilities and growth rates under anaerobic conditions [13].

Methodology:

- Start with the default model configuration (minimal medium with D-glucose as carbon source)

- Identify the oxygen exchange reaction (EXo2e)

- Constrain oxygen uptake by setting the lower bound of EXo2e to zero

- Maintain biomass maximization as the objective function

- Solve the linear programming problem to determine the maximum growth rate

Expected Results: Under anaerobic conditions with glucose as carbon source, the predicted growth rate should be approximately 0.211 h⁻¹ [13]. Some carbon sources (e.g., succinate) may not support anaerobic growth, resulting in an "Infeasible solution/Dead cell" output.

Protocol 3: Predicting Gene Essentiality

Purpose: To identify metabolic genes essential for growth under specific environmental conditions [9] [32].

Methodology:

- For each gene in the model, simulate a knockout by constraining all reactions catalyzed by that gene to zero flux

- For reactions catalyzed by multiple enzymes, constrain fluxes only if all isozymes are knocked out

- For enzyme complexes, simultaneously constrain all subunit genes

- Calculate the growth rate for each knockout strain using FBA with biomass maximization

- Compare simulated growth rates with experimental fitness data from RB-TnSeq or other high-throughput methods

- Classify genes as essential (growth rate < threshold) or non-essential (growth rate ≥ threshold)

Expected Results: The latest E. coli GEM (iML1515) shows high accuracy in predicting gene essentiality, though errors often involve vitamin/cofactor biosynthesis genes due to cross-feeding or metabolite carryover in experimental systems [32].

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for E. coli Metabolic Modeling

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Package | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling | https://opencobra.github.io/cobratoolbox/ |

| COBRApy | Software Package | Python-based constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | https://opencobra.github.io/cobrapy/ |

| Escher-FBA | Web Application | Interactive FBA simulation with pathway visualization | https://sbrg.github.io/escher-fba |

| BiGG Models | Knowledgebase | Curated multiscale metabolic network reconstruction | http://bigg.ucsd.edu |

| EcoCyc | Database | Encyclopedia of E. coli genes and metabolism | http://ecocyc.org |

| GLPK | Solver | GNU Linear Programming Kit for optimization | https://www.gnu.org/software/glpk/ |

| iML1515 | Metabolic Model | Latest E. coli K-12 MG1655 genome-scale model | BiGG Models |

| RB-TnSeq | Experimental Method | High-throughput mutant fitness profiling | [32] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Predicting Drug Synergies

Flux Balance Analysis has been extended to simulate responses to chemical inhibitors by implementing flux diversion (FBA-div) [34]. This approach models competitive enzyme inhibition by diverting metabolic flux to non-productive waste reactions, enabling prediction of antibiotic synergies between serial metabolic targets. The FBA-div method accurately predicts synergistic drug interactions that cannot be captured by traditional gene knockout simulations [34].

Diagram: Flux Diversion (FBA-div) Mechanism for Simulating Drug Effects. This approach models competitive inhibition by diverting metabolic flux to waste, enabling prediction of antibiotic synergies.

Machine Learning Integration

Recent advances combine neural-mechanistic hybrid models to improve the predictive power of genome-scale metabolic models [35]. These artificial metabolic networks (AMNs) embed FBA within trainable neural networks, overcoming the limitation of traditional FBA in converting extracellular concentrations to uptake flux bounds. AMNs systematically outperform traditional constraint-based models while requiring training set sizes orders of magnitude smaller than classical machine learning methods [35].

Validation and Model Refinement

Rigorous validation of E. coli metabolic models utilizes high-throughput mutant fitness data across multiple growth conditions [32]. Key metrics include:

- Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (AUC): Robust metric for assessing gene essentiality prediction accuracy

- Nutrient Utilization Accuracy: Percentage of correct growth/no-growth predictions across different carbon sources

- Reaction Essentiality Concordance: Agreement between simulated and experimental reaction essentiality

Systematic error analysis has identified vitamin/cofactor biosynthesis pathways as common sources of inaccurate predictions, often due to cross-feeding between mutants or metabolite carryover in experimental systems [32].

The development of E. coli in silico models represents a remarkable success story in systems biology, demonstrating how iterative model refinement coupled with experimental validation can enhance predictive accuracy and biological insight. From early stoichiometric models to current whole-cell simulation efforts, E. coli metabolic modeling has continuously evolved to incorporate new biological knowledge and computational methodologies.

Flux Balance Analysis remains a foundational approach for constraint-based modeling, providing a mathematically rigorous framework for predicting metabolic phenotypes from genomic information. The integration of machine learning techniques, sophisticated visualization tools, and high-throughput experimental validation promises to further enhance model utility and accuracy.

As Francis Crick envisioned decades ago, the pursuit of a "complete solution" for E. coli continues to drive interdisciplinary innovation, with applications spanning basic microbiology, metabolic engineering, and therapeutic development. The historical developments and technical approaches summarized in this guide provide both a foundation for researchers entering the field and a reference for practitioners advancing the state of the art in metabolic modeling.

Implementing FBA: A Step-by-Step Workflow and Key Applications in Research and Development

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a powerful mathematical approach for analyzing the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, serving as a cornerstone technique in systems biology and metabolic engineering [8]. This constraint-based method enables researchers to predict metabolic phenotypes, such as cellular growth rates or the production of valuable biochemicals, by leveraging genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) that contain all known metabolic reactions for an organism [3] [8]. Unlike kinetic modeling approaches that require difficult-to-measure parameters, FBA relies primarily on reaction stoichiometries and flux constraints, making it particularly suitable for large-scale network analysis [8]. For Escherichia coli research, one of the most extensively studied microorganisms, FBA provides an invaluable framework for understanding metabolic capabilities, predicting gene essentiality, and designing engineered strains for biotechnological applications [3] [4]. This guide presents a comprehensive technical framework for implementing FBA, from initial network reconstruction to final flux prediction, with specific examples drawn from E. coli metabolism research.

Theoretical Foundations of FBA

Mathematical Principles and Formulations

The core mathematical foundation of FBA centers on representing metabolism as a stoichiometric matrix S of dimensions m × n, where m represents the number of metabolites and n the number of metabolic reactions in the network [8]. Each element Sᵢⱼ in this matrix corresponds to the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j, with negative coefficients indicating substrate consumption and positive coefficients indicating product formation [8]. The fundamental equation governing metabolic fluxes at steady state is:

Sv = 0

where v is an n-dimensional vector of metabolic reaction fluxes [8]. This mass balance equation ensures that for each metabolite in the system, the total production equals total consumption, preventing unrealistic accumulation or depletion of intracellular metabolites.

FBA extends this framework by incorporating flux constraints and an optimization objective. Each reaction flux vᵢ is constrained by lower and upper bounds:

vᵢᵐⁱⁿ ≤ vᵢ ≤ vᵢᵐᵃˣ

These bounds define the solution space of all possible metabolic flux distributions that satisfy the stoichiometric and capacity constraints [3] [8]. The final element involves defining a biological objective function Z = cᵀv, which represents a linear combination of fluxes that the model will optimize, typically biomass production for cellular growth or synthesis of a target metabolite for biotechnological applications [8].

Key Assumptions and Limitations

FBA operates under several critical assumptions that researchers must acknowledge. The steady-state assumption posits that metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, with production and consumption rates balanced [3] [8]. While mathematically convenient, this assumption limits FBA's ability to capture transient metabolic dynamics. The method also does not incorporate metabolic regulation through gene expression or allosteric regulation unless explicitly modeled through additional constraints [8]. Furthermore, FBA links genotype to phenotype through Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations, but does not account for post-translational modifications or metabolic channeling [3]. A notable limitation is the prediction of unrealistically high fluxes through certain pathways when constraints are insufficient, necessitating additional enzymatic or thermodynamic constraints for improved realism [3].

Computational Workflow for FBA

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for performing Flux Balance Analysis, from initial model preparation to final validation:

Network Reconstruction

The foundation of any FBA study begins with a high-quality metabolic network reconstruction. For E. coli, several curated models are available, with iML1515 representing the most complete reconstruction for the K-12 MG1655 strain, containing 1,515 genes, 2,712 metabolic reactions, and 1,192 metabolites [3] [4]. The reconstruction process involves compiling all known metabolic reactions from databases such as EcoCyc and KEGG, establishing accurate Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations, and identifying knowledge gaps through systematic gap-filling [3] [22]. For researchers interested in central metabolism rather than genome-scale analysis, reduced models such as iCH360 offer a manually curated alternative focusing on energy and biosynthesis metabolism while maintaining connectivity to biomass formation [4].

Defining System Constraints

Constraint definition critically shapes the FBA solution space. The primary constraints include:

Stoichiometric constraints encoded in the S matrix enforce mass balance for all intracellular metabolites [8]. Reaction bounds define the biochemical capacity of each reaction, with irreversible reactions constrained to positive fluxes (0 ≤ vᵢ ≤ vᵢᵐᵃˣ) and reversible reactions allowed negative fluxes (vᵢᵐⁱⁿ ≤ vᵢ ≤ vᵢᵐᵃˣ) [8]. Environmental constraints model nutrient availability by setting upper bounds on substrate uptake reactions, with glucose-limited conditions typically implemented by setting the glucose uptake rate to ~10 mmol/gDW/h [8]. Enzyme constraints incorporate proteomic limitations by calculating enzyme demand based on kcat values and molecular weights, with the total enzyme capacity typically constrained to ~0.56 g protein/gDW [3].

Objective Function Selection and Optimization

The choice of objective function determines the biological behavior predicted by FBA. While biomass maximization effectively simulates exponential growth conditions, biotechnological applications often require multi-objective optimization or lexicographic approaches that balance product formation with cellular growth [3]. The optimization problem is formally expressed as:

Maximize: Z = cᵀv

Subject to: Sv = 0, and vᵢᵐⁱⁿ ≤ vᵢ ≤ vᵢᵐᵃˣ

This linear programming problem is solved computationally using algorithms such as the simplex or interior-point methods, typically implemented through packages like COBRApy [3].

Case Study: FBA for L-Cysteine Overproduction in E. coli

Model Customization and Experimental Setup

Implementing FBA for a specific metabolic engineering application requires careful model customization. In a case study targeting L-cysteine overproduction, researchers began with the iML1515 model and implemented several key modifications [3]. The following table summarizes the critical parameters modified to reflect genetic engineering of the L-cysteine biosynthesis pathways:

Table 1: Model Modifications for L-Cysteine Overproduction in E. coli [3]

| Parameter | Gene/Enzyme/Reaction | Original Value | Modified Value | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kcat_forward | PGCD (SerA) | 20 1/s | 2000 1/s | Removal of feedback inhibition [36] |

| Kcat_reverse | SERAT (CysE) | 15.79 1/s | 42.15 1/s | Increased mutant enzyme activity [3] |

| Kcat_forward | SERAT (CysE) | 38 1/s | 101.46 1/s | Increased mutant enzyme activity [3] |

| Kcat_forward | SLCYSS | None | 24 1/s | Addition of missing transport reaction [37] |

| Gene Abundance | SerA/b2913 | 626 ppm | 5,643,000 ppm | Modified promoter and copy number [38] |

| Gene Abundance | CysE/b3607 | 66.4 ppm | 20,632.5 ppm | Modified promoter and copy number [38] |

Additionally, medium conditions were defined to simulate the bioreactor environment, with uptake bounds set for key nutrients:

Table 2: Medium Component Uptake Bounds for L-Cysteine Production [3]

| Medium Component | Associated Uptake Reaction | Upper Bound (mmol/gDW/h) |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | EXglcDe_reverse | 55.51 |

| Citrate | EXcite_reverse | 5.29 |

| Ammonium Ion | EXnh4e_reverse | 554.32 |

| Phosphate | EXpie_reverse | 157.94 |

| Magnesium | EXmg2e_reverse | 12.34 |

| Sulfate | EXso4e_reverse | 5.75 |

| Thiosulfate | EXtsule_reverse | 44.60 |

Implementation and Validation

The practical implementation of FBA requires specialized computational tools and packages. The following table outlines essential resources for performing FBA with E. coli models:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for FBA Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Models | iML1515, iCH360, E. coli Core Model | Genome-scale and reduced models of E. coli metabolism [3] [8] [4] |

| Software Packages | COBRApy, ECMpy, R Sybil | Python and R packages for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis [3] [34] |

| Reaction Databases | EcoCyc, BRENDA, KEGG | Sources of stoichiometric, kinetic, and thermodynamic data [3] [22] |

| Protein Data | PAXdb, UniProt | Protein abundance and molecular weight information [3] |

| Simulation Algorithms | Linear Programming (FBA), Flux Variability Analysis (FVA), Monte Carlo Sampling | Methods for predicting flux distributions and exploring solution spaces [3] [37] |

Implementation proceeds through several stages: loading the base metabolic model using COBRApy functions, modifying reaction bounds and GPR rules to reflect genetic manipulations, adding enzyme constraints using the ECMpy workflow, setting medium conditions through exchange reaction bounds, and finally performing FBA with appropriate objective functions [3]. Validation involves comparing predictions with experimental data, such as measuring growth rates or product yields from cultured strains under defined conditions [3].

Advanced Applications and Methodological Extensions

Advanced FBA Techniques