Flux Balance Analysis of E. coli Central Carbon Metabolism: A Comprehensive Guide for Systems Biology and Metabolic Engineering

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists on applying Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to Escherichia coli's central carbon metabolism (CCM).

Flux Balance Analysis of E. coli Central Carbon Metabolism: A Comprehensive Guide for Systems Biology and Metabolic Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists on applying Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to Escherichia coli's central carbon metabolism (CCM). It covers foundational principles, including the structure of CCM and its role in energy and precursor synthesis. The guide details core methodological approaches like constraint-based modeling and 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) for experimental flux estimation. It further addresses advanced strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing models, such as integrating regulatory constraints and introducing synthetic pathways. Finally, the article outlines rigorous model validation and comparative analysis techniques to ensure predictive reliability. By synthesizing current methodologies and applications, this resource aims to enhance the use of E. coli in biotechnological and biomedical research, from rational strain design to drug development.

Understanding E. coli Central Carbon Metabolism: Network Structure and Functional Principles

Central carbon metabolism, comprising the core pathways of glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, serves as the fundamental biochemical network for energy production and precursor generation in living organisms. In Escherichia coli, these pathways are not only conserved but have become a model system for quantitative analysis using techniques like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and kinetic modeling [1] [2]. These computational approaches allow researchers to interpret and predict metabolic phenotypes, understand the effects of genetic modifications, and identify critical regulatory nodes under various physiological conditions, including oxidative stress and overflow metabolism [3] [4]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of these core pathways, detailing their reactions, quantitative flux distributions, and the experimental and computational methodologies essential for studying them within the context of E. coli central carbon metabolism.

Glycolysis (Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas Pathway)

Glycolysis is a ten-step metabolic sequence that converts one molecule of glucose into two molecules of pyruvate, yielding a net gain of ATP and NADH [1] [5]. In E. coli, glucose is often transported into the cell via the Phosphotransferase System (PTS), which simultaneously phosphorylates it to Glucose-6-Phosphate (G6P) [1]. The key enzymes include phosphofructokinase (Pfk), a highly regulated step, and pyruvate kinase (Pyk), which catalyzes the final yield of pyruvate [1].

Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP)

The PPP operates in two distinct phases: the oxidative and non-oxidative branches. The oxidative phase, starting with G6P, is a primary source of cellular NADPH, essential for reductive biosynthesis and oxidative stress response [3]. The non-oxidative phase involves a series of carbon-shuffling reactions, catalyzed by transketolases and transaldolases, which generate various sugar phosphates like Ribose-5-Phosphate (R5P) for nucleotide synthesis and link back to glycolytic intermediates [1] [3].

Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle and Associated Pathways

The TCA cycle is the central hub for the aerobic oxidation of acetyl-CoA, derived from pyruvate, producing NADH, FADH2, and GTP, as well as precursor molecules for biosynthesis [1]. In E. coli, the cycle is closely integrated with the glyoxylate shunt and anaplerotic reactions [1]. The glyoxylate shunt, bypassing decarboxylative steps in the TCA cycle, allows for the net assimilation of carbon from two-carbon compounds like acetate [1]. Anaplerotic reactions, such as those catalyzed by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (Ppc) and malic enzyme (Mez), replenish TCA cycle intermediates drawn off for biosynthesis [1] [3].

Table 1: Key Metabolic Reactions in E. coli Central Carbon Metabolism

| Pathway | Reaction/Step Abbreviation | Enzyme | Input | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | Pgi | Phosphoglucose isomerase | Glucose-6-Phosphate (G6P) | Fructose-6-Phosphate (F6P) |

| Pfk | Phosphofructokinase | Fructose-6-Phosphate (F6P) | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FDP) | |

| Pyk | Pyruvate kinase | Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) | Pyruvate (PYR) | |

| PPP | G6pdh | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | Glucose-6-Phosphate (G6P) | NADPH + 6-Phosphogluconolactone |

| Gnd | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 6-Phosphogluconate | NADPH + Ribulose-5-Phosphate | |

| Tkt | Transketolase | Various sugar phosphates | Various sugar phosphates | |

| TCA Cycle | Glta | Citrate synthase | Acetyl-CoA + Oxaloacetate (OAA) | Citrate (CIT) |

| Icd | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | Isocitrate (ICIT) | NADPH + α-Ketoglutarate (AKG) | |

| Akd | α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase | α-Ketoglutarate (AKG) | NADH + Succinyl-CoA | |

| Sdh | Succinate dehydrogenase | Succinate | FADH2 + Fumarate | |

| Mdh | Malate dehydrogenase | Malate | NADH + Oxaloacetate (OAA) | |

| Glyoxylate Shunt | AceA | Isocitrate lyase | Isocitrate (ICIT) | Glyoxylate + Succinate |

| AceB | Malate synthase | Glyoxylate + Acetyl-CoA | Malate | |

| Anaplerotic | Ppc | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) | Oxaloacetate (OAA) |

| Mez | Malic enzyme | Malate | NADPH + Pyruvate (PYR) |

Metabolic Flux Analysis and Quantitative Flux Distributions

Metabolic flux is defined as the in vivo rate of an enzyme reaction, representing the number of converted molecules per unit time per cell (mol hâ»Â¹ cellâ»Â¹) [5]. It is the definitive parameter for investigating cell metabolism because the activation and inactivation of metabolic pathways can be directly evaluated by determining flux levels. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constraint-based modeling approach used to compute the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network [2]. It relies on solving a system of linear equations based on the stoichiometric matrix (S) of all reactions, subject to mass balance constraints (S • v = 0, where v is the flux vector) and capacity constraints (αᵢ ≤ váµ¢ ≤ βᵢ) [2]. FBA can predict optimal flux distributions that maximize a cellular objective, typically biomass production, and has been successfully used to interpret the metabolic phenotypes of wild-type and mutant E. coli strains [2].

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Metabolic Fluxes in E. coli Central Metabolism (mmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹) [3]

| Metabolic Flux | Normal Medium | PQ-containing Medium (Oxidative Stress) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific α-Ketoglutarate Production (Qakg) | 0.84 ± 0.13 | 1.73 ± 0.18 | More than doubles under stress |

| Specific Pyruvate Production (Qpyr) | 0.04 ± 0.005 | 0.02 ± 0.008 | Decreases under stress |

| Specific Lactate Production (Qlac) | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | Decreases under stress |

| Specific Acetate Production (Qace) | - | 4.31 ± 1.2 | Significant production induced |

| Biomass Yield on Glucose (Ybiomass/glc) | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.322 ± 0.023 | Reduced yield under stress |

| NADPH:NADH Ratio | ~0.81 | ~1.15 (Increase of 1.6-1.8x) | Measured and calculated from fluxes |

Quantitative flux analyses have revealed how E. coli redistributes its metabolism in response to environmental challenges. For instance, under paraquat-induced superoxide stress, fluxes are systematically redirected [3]:

- PPP fluxes increase to generate more NADPH for antioxidant defense.

- TCA cycle fluxes (e.g., Icd, Akd) decrease, while the glyoxylate shunt fluxes increase.

- Acetate efflux increases significantly, a phenomenon known as overflow metabolism [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

¹³C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (¹³C-MFA)

¹³C-MFA is a powerful method for estimating the in vivo flux distribution in central carbon metabolism from experimentally measured specific rates and ¹³C-labeling patterns of metabolites under metabolic steady state [5].

Protocol Summary:

- Cultivation: Grow E. coli in a controlled bioreactor (e.g., chemostat) with a defined medium where the sole carbon source (e.g., glucose) is replaced with a ¹³C-labeled variant (e.g., [1-¹³C]-glucose or [U-¹³C]-glucose) [3] [5].

- Metabolite Extraction: At metabolic steady-state, rapidly sample the culture and quench metabolism (e.g., using cold methanol). Intracellular metabolites are extracted [5].

- Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis: Derivatize the metabolite extracts and analyze them using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). The mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of the fragments are measured [5].

- Flux Calculation: Use specialized software (e.g., ¹³C-FLUX) to integrate the measured MIDs with the stoichiometric model of the metabolic network. The software performs parameter fitting to find the flux map that best reproduces the experimental labeling data [3]. Confidence intervals for the estimated fluxes can be calculated using statistical methods like Monte Carlo sampling [3].

Kinetic Model Construction and Parameter Estimation

Kinetic models simulate the dynamic behavior of metabolic pathways by using enzyme rate equations, which require knowledge of kinetic parameters [1].

Protocol Summary:

- Network Definition: Construct a detailed map of the metabolic network, including all relevant reactions, allosteric effectors, and gene regulatory interactions (e.g., by transcription factors like Crp, Cra) [1].

- Rate Equation Formulation: Assign appropriate kinetic rate laws (e.g., Michaelis-Menten, Hill equations) to each enzymatic reaction based on literature [1].

- Parameter Estimation: Use computational optimization algorithms (e.g., genetic algorithms) on high-performance computing systems to estimate the unknown kinetic parameter values. The objective is to minimize the difference between model simulations and experimental time-course data (e.g., biomass, extracellular metabolites, intracellular metabolite concentrations) [1].

- Model Validation: Validate the model by testing its ability to accurately reproduce the dynamic behavior of wild-type E. coli and, crucially, various genetic knockout mutants (e.g., ∆pykF, ∆pgi) in a batch culture [1].

Visualization of Metabolic Networks and Analysis Workflows

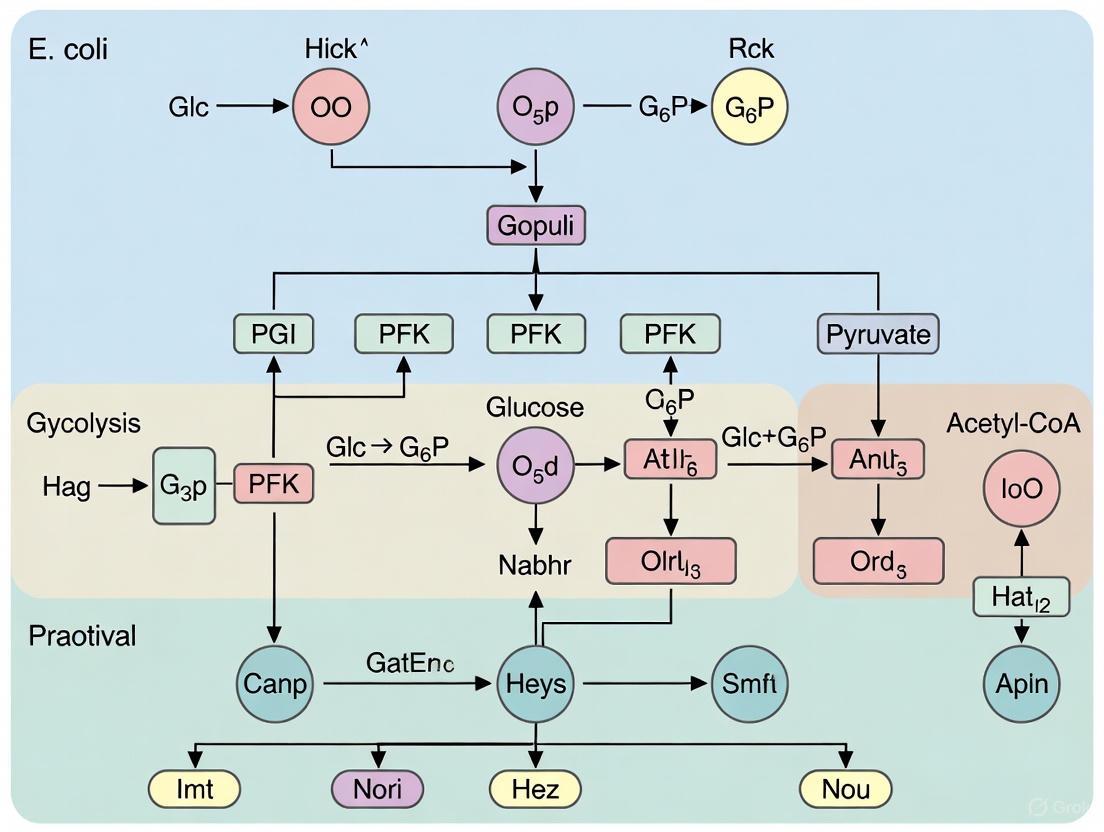

E. coli Central Carbon Metabolic Network

Diagram 1: E. coli Central Carbon Metabolic Network. The diagram shows the integration of glycolysis, PPP, TCA cycle, glyoxylate shunt (green), and anaplerotic reactions (yellow). NADPH-producing reactions are highlighted in red.

¹³C-MFA Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: ¹³C-MFA Experimental Workflow. Key steps from cultivating cells with a labeled carbon source to generating a statistically validated quantitative flux map.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Central Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ¹³C-Labeled Glucose (e.g., [1-¹³C], [U-¹³C]) | Tracer for ¹³C-MFA; allows for the experimental determination of intracellular metabolic fluxes by incorporating a measurable isotopic label into metabolites. | Used in chemostat cultivations to trace the fate of carbon atoms through the metabolic network and quantify flux distributions [3] [5]. |

| Enzyme Activity Assay Kits | In vitro measurement of the maximum catalytic activity (Vmax) of specific enzymes (e.g., G6PDH, AKGDH). | Used to validate changes in enzyme capacity suggested by flux or gene expression data, particularly in response to stressors like paraquat [3]. |

| Metabolite Standards (LC-MS/GC-MS grade) | Absolute quantification of intracellular metabolite concentrations (metabolomics) using mass spectrometry. | Essential for calculating Gibbs free-energy changes (ΔG') of reactions and evaluating the thermodynamic state of pathways [5]. |

| Paraquat (Methyl Viologen) | Chemical inducer of superoxide stress; used to perturb the metabolic network and study the resulting flux adaptations. | Applied in chemostat studies to investigate the redox stress response, including flux rerouting to the PPP [3]. |

| Stoichiometric Model (e.g., iML1515) | A computational matrix (S) representing all known metabolic reactions in E. coli. The core constraint for FBA. | Used in FBA and ¹³C-MFA to simulate metabolic behavior and interpret mutant phenotypes in silico [2]. |

| Kinetic Model Parameters (Kₘ, kcat, Hill coeff.) | Experimentally derived or fitted constants for enzyme rate equations. Enable dynamic simulation of metabolism. | Estimated via optimization algorithms to build predictive kinetic models of the central metabolic network [1]. |

| Icmt-IN-37 | Icmt-IN-37, MF:C22H28ClNO, MW:357.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PROTAC PAPD5 degrader 1 | PROTAC PAPD5 degrader 1, MF:C49H63N5O16, MW:978.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Role of CCM in Energy Production, Redox Balancing, and Biomass Precursor Synthesis

Central Carbon Metabolism (CCM) serves as the biochemical core of Escherichia coli, integrating catabolic and anabolic processes to sustain cellular life. This network encompasses the primary pathways responsible for energy production, redox balancing, and the synthesis of critical biomass precursors. In the context of metabolic engineering and flux balance analysis (FBA) research, a detailed understanding of CCM is paramount for manipulating bacterial physiology for biomedical and biotechnological applications. The recent development of curated metabolic models like iCH360, a manually refined sub-network of the genome-scale iML1515 reconstruction, provides an optimized framework for investigating these processes with enhanced biological accuracy [6]. These models facilitate sophisticated computational analyses, including enzyme-constrained FBA and thermodynamic profiling, enabling researchers to predict intracellular flux distributions and identify key regulatory nodes under various genetic and environmental conditions.

The functional output of CCM is fundamentally governed by its architectural properties. The E. coli metabolic network, as cataloged in foundational resources like EcoCyc, comprises hundreds of interconnected reactions and metabolites [7]. CCM demonstrates remarkable robustness, maintaining flux ratio homeostasis despite significant genetic perturbations, such as the overexpression of key enzymes like phosphofructokinase or pyruvate kinase [8]. This inherent stability underscores the complexity of its regulatory design. For drug development professionals, targeting this metabolic network offers promising avenues for disrupting bacterial viability. This guide provides a technical examination of CCM, consolidating quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visual tools to support advanced research in this field.

Quantitative Architecture ofE. coliCCM

The global properties of the E. coli metabolic network reveal a system optimized for efficiency and connectivity. Computational analyses of the EcoCyc database quantify the network as consisting of 744 reactions catalyzed by 607 enzymes, which act upon 791 distinct chemical substrates [7]. This network is organized into 131 pathways, with pathway lengths ranging from single-step reactions to extended sequences of up to 16 steps, averaging 5.4 reactions per pathway [7].

Key Metabolite Participation Frequencies

The connectivity of the network is underscored by the recurrence of specific metabolites across numerous reactions. The following table lists the most frequently occurring substrates in E. coli small-molecule metabolism, highlighting the central role of energy carriers, redox cofactors, and universal metabolites [7].

Table 1: High-Frequency Metabolites in E. coli Central Carbon Metabolism

| Metabolite | Number of Reactions | Primary Metabolic Role |

|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚O | 205 | Universal solvent, hydrolysis/hydration reactions |

| ATP | 152 | Primary energy currency, phosphorylation |

| ADP | 101 | Energy regeneration, product of ATP hydrolysis |

| Phosphate | 100 | Phosphorylation, energy transfer |

| Pyrophosphate | 89 | Biosynthetic reactions, driving irreversible steps |

| NAD | 66 | Redox cofactor (oxidized form), electron acceptor |

| NADH | 60 | Redox cofactor (reduced form), electron donor |

| COâ‚‚ | 54 | Product of decarboxylation reactions, gas |

| H⺠| 53 | Proton, pH regulation, chemiosmotic energy |

| AMP | 49 | Energy status indicator, allosteric regulation |

Functional Organization of Metabolic Pathways

The pathways of CCM can be categorized based on their primary functional outputs. The table below summarizes the core pathways directly involved in energy production, redox balancing, and the synthesis of biomass precursors.

Table 2: Core Functional Pathways in E. coli Central Carbon Metabolism

| Pathway Name | Primary Function | Key Inputs | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis (Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas) | Glucose catabolism, net ATP/NADH production, precursor generation | Glucose, ATP, NAD⺠| Pyruvate, ATP, NADH, Precursors (G3P, PEP) |

| Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle | Complete oxidation of acetyl-CoA, high-yield NADH/FADHâ‚‚ generation, precursor provision | Acetyl-CoA, Oxaloacetate, NADâº, GDP | COâ‚‚, NADH, FADHâ‚‚, ATP (GTP), Biosynthetic precursors |

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) | NADPH production for biosynthesis, pentose sugars for nucleotides | Glucose-6-P, NADP⺠| Ribose-5-P, NADPH, CO₂ |

| Oxidative Phosphorylation | ATP synthesis via proton motive force, redox balancing (NADH/FADHâ‚‚ oxidation) | NADH, FADHâ‚‚, Oâ‚‚ (terminal eâ» acceptor), ADP + Pi | ATP, Hâ‚‚O, NADâº, FAD |

| Gluconeogenesis | Glucose synthesis from non-carbohydrate precursors | Pyruvate, Oxaloacetate, ATP | Glucose-6-P |

| Glyoxylate Shunt | Anaplerotic pathway for TCA cycle during growth on Câ‚‚ substrates (e.g., acetate) | Acetyl-CoA, Glyoxylate | Succinate, Malate |

Experimental Analysis of Metabolic Flux

Metabolic Flux Ratio (METAFoR) Analysis

Principle: METAFoR analysis is a powerful methodology that determines the relative fluxes of converging metabolic pathways and identifies active routes in central carbon metabolism. It is based on two-dimensional ¹³C-¹H correlation nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy of hydrolyzed cell protein from biomass that has been fractionally labeled with [U-¹³C₆]glucose [8]. The technique leverages the fact that alternative metabolic pathways produce different patterns of intact carbon-carbon bonds from a single glucose molecule, which are then preserved in the amino acids of cellular protein.

Workflow Diagram:

Diagram Title: METAFoR Analysis Experimental Workflow

Detailed Protocol:

Strain and Medium Preparation:

- Utilize E. coli strains such as the wild-type K-12 strain MG1655 or other relevant derivatives (e.g., JM101, PB25) [8].

- Prepare a defined minimal medium. A standard composition per liter includes [8]:

- 5 g Glucose (for batch culture)

- 48 mM Naâ‚‚HPOâ‚„

- 22 mM KHâ‚‚POâ‚„

- 10 mM NaCl

- 30 mM (NHâ‚„)â‚‚SOâ‚„

- 1 mM MgSOâ‚„ (separately sterilized)

- 0.1 mM CaClâ‚‚ (separately sterilized)

- 1 mg Vitamin Bâ‚ (Thiamine) (filter sterilized)

- 10 mL Trace element solution

Fractional Labeling and Cultivation:

- Replace natural abundance glucose in the medium with a mixture of 85-90% natural abundance glucose and 10-15% [U-¹³C₆]glucose (¹³C, >98%) [8].

- Inoculate the medium and grow cells under controlled conditions (e.g., 30°C for aerobic batch cultures in baffled shake flasks at 200 rpm). For chemostat studies, operate at a steady state (e.g., dilution rate D = 0.2 hâ»Â¹) before switching to the labeled feed.

Biomass Harvesting and Processing:

- Harvest biomass during mid-exponential growth phase (or after one volume change in chemostats to ensure ~63% fractional labeling).

- Centrifuge cells, wash, and lyse.

- Hydrolyze the harvested cellular protein using 6 M HCl at 105°C for 24 hours to release free amino acids [8].

NMR Spectroscopy and Data Analysis:

- Analyze the hydrolyzed amino acid mixture using two-dimensional ¹³C-¹H correlation NMR (COSY).

- Quantify the intensities of the multiplet components in the ¹³C fine structure of specific amino acid carbon atoms. These multiplets reflect the relative abundance of intact carbon fragments from the original glucose.

- Apply probabilistic equations to the multiplet data to derive intracellular metabolic flux ratios, such as the fraction of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) molecules derived through transketolase reactions or the relative contribution of anaplerotic PEP carboxylation versus the TCA cycle for oxaloacetate synthesis [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and computational tools essential for experimental and in silico analysis of E. coli CCM.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for CCM Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example & Context |

|---|---|---|

| [U-¹³C₆]glucose | Tracer for METAFoR analysis and ¹³C Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA). | Enables determination of pathway fluxes and ratios via NMR or MS; used at 10-15% labeling fraction [8]. |

| Defined Minimal Medium | Provides controlled nutrient environment for physiological studies. | Essential for chemostat cultures and labeling experiments to avoid unaccounted carbon sources [8]. |

| iCH360 Metabolic Model | A manually curated, medium-scale model for constraint-based modeling of E. coli core and biosynthetic metabolism. | Used for Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), enzyme-constrained simulations, and EFM analysis; a sub-network of iML1515 [6]. |

| EcoCyc Database | Comprehensive, literature-based knowledgebase of E. coli genes, metabolism, and regulation. | Used for pathway information, gene-reaction associations, and biochemical data retrieval [9] [7]. |

| Fluxer Web Application | Tool for automated FBA computation and visualization of genome-scale metabolic models. | Visualizes flux distributions as spanning trees or dendrograms from SBML models; useful for interpreting FBA results [10]. |

Computational Modeling of CCM: Flux Balance Analysis

Fundamentals and Application of FBA

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constraint-based modeling approach used to predict the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network at steady state. It computes reaction rates (fluxes) that optimize a cellular objective, typically the maximization of biomass production, which represents bacterial growth [10]. The iCH360 model is particularly suited for this analysis as it retains the critical pathways for energy and precursor synthesis while being compact enough for advanced analyses like Elementary Flux Mode (EFM) analysis and thermodynamic profiling [6]. FBA can predict the outcome of genetic manipulations, such as gene knockouts, and environmental perturbations, providing testable hypotheses for experimental validation.

FBA Workflow and Pathway Integration

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of FBA and how CCM pathways are integrated to achieve the core functions of energy production, redox balance, and biomass synthesis.

Diagram Title: FBA Logic and CCM Pathway Integration

The central carbon metabolism of E. coli is a highly integrated and robust system that efficiently coordinates energy production, redox homeostasis, and the generation of biomass precursors. The continued development of curated metabolic models like iCH360, coupled with advanced experimental techniques such as METAFoR analysis, provides an increasingly quantitative and mechanistic understanding of this system. The integration of rich biological data—including thermodynamic and kinetic parameters—into these models enhances their predictive power for both basic research and applied fields.

For drug development, targeting the unique aspects of bacterial CCM, especially under infection-relevant conditions like nutrient limitation, presents a promising strategy for novel antimicrobials. Furthermore, the principles of growth-coupled selection, where cell survival is linked to the activity of an engineered pathway, are being leveraged to rewire E. coli CCM for biotechnological applications, including the production of sustainable chemicals and materials [11]. Future research will focus on further refining models to capture regulatory constraints and on using these integrated computational and experimental approaches to precisely control metabolic flux for desired outcomes.

Principles of Constraint-Based Modeling and Steady-State Assumption in FBA

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a mathematical approach for simulating metabolism of cells or entire unicellular organisms using genome-scale metabolic reconstructions [12]. This constraint-based modeling method has become a cornerstone of systems biology, enabling researchers to study metabolic network behavior without requiring extensive kinetic parameter data. FBA operates on the fundamental premise that stoichiometric, thermodynamic, and capacity constraints limit the flux values for biochemical reactions within a cell to a feasible region known as the solution space [13]. The method has found diverse applications in bioprocess engineering, drug target identification, culture media design, and host-pathogen interaction studies [12]. When applied to E. coli central carbon metabolism, FBA provides a powerful framework for predicting how genetic modifications or environmental changes affect metabolic flux distributions, enabling rational design of microbial cell factories for industrial biotechnology.

The steady-state assumption represents the core theoretical foundation of FBA, distinguishing it from dynamic modeling approaches that require detailed kinetic parameters [14] [15]. This principle posits that metabolite concentrations remain constant over the timescale of analysis, with production and consumption rates balanced to achieve no net accumulation or depletion of intracellular metabolites. For E. coli metabolism, this assumption is particularly relevant during balanced exponential growth, where internal metabolite pools remain relatively stable while biomass components are synthesized at constant rates.

Mathematical Foundations of FBA

Core Mathematical Formulation

The mathematical basis of FBA formalizes the system of equations describing metabolic concentration changes as the dot product of a stoichiometric matrix (S) and a flux vector (v), equaling zero at steady state [12]:

S â‹… v = 0

This equation represents the mass balance constraint for all metabolites in the system. The stoichiometric matrix S is an m × n matrix where m represents the number of metabolites and n the number of reactions. Each element Sij corresponds to the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. The flux vector v contains the reaction rates (fluxes) through each metabolic reaction.

The underdetermined nature of this system (typically more reactions than metabolites) necessitates additional constraints to identify meaningful biological solutions:

lowerbound ≤ v ≤ upperbound

These inequality constraints implement reaction reversibility/irreversibility and capacity limits based on enzyme activity or substrate uptake rates.

Optimization Framework

FBA identifies a particular flux distribution from the feasible solution space by optimizing an objective function, typically formulated as a linear programming problem [12]:

where c is a vector of coefficients defining the linear objective function, with typically only one element (corresponding to biomass production) set to 1 and others to 0. For E. coli models, the biomass objective function often incorporates experimentally determined biomass composition data, representing the drain of biosynthetic precursors needed to support cellular growth.

The Steady-State Assumption: Theoretical Basis and Implications

Physiological Basis and Validity

The steady-state assumption in FBA reduces the system to a set of linear equations by asserting that internal metabolite concentrations do not change significantly during the analysis period [12]. This assumption is biologically justified for E. coli central carbon metabolism during mid-exponential growth in batch culture or in continuous culture at steady state, where metabolic fluxes remain relatively constant over time. The material balance model underlying this approach can be summarized as:

Input = Output + Accumulation

With the steady-state assumption, the accumulation term becomes zero, simplifying to:

Input - Output = 0

This simplification makes the analysis tractable for genome-scale models containing thousands of reactions and metabolites. The steady-state formulation has no mechanistic knowledge of chemical reactions beyond their stoichiometry and produces a high-dimensional continuum of steady-state solutions rather than a unique solution [14] [15].

Comparison with Dynamic Formulations

Dynamic models based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs) provide an alternative modeling approach that describes metabolite concentration changes over time using kinetic rate laws [14] [15]. These models contain detailed mechanistic information but require extensive parameter estimation. Comparative studies of E. coli central carbon metabolism have revealed that dynamic and constraint-based formulations describe the same set of steady states when unconstrained [14] [15]. However, incorporating partial kinetic parameter knowledge into dynamic models can generate additional constraints that reduce the solution space below that identified by constraint-based models alone, eliminating infeasible solutions [15].

Diagram 1: Relationship between modeling components showing how additional constraints reduce the feasible solution space.

Solution Space Analysis and Sampling Methods

Characterizing the Feasible Flux Space

The solution space of an FBA model comprises all flux distributions satisfying the stoichiometric and constraint equations [13]. This space forms a convex polyhedron in n-dimensional flux space. For realistic models, this space remains extensively underdetermined even after applying all constraints, resulting in infinite feasible flux distributions. Several approaches have been developed to characterize this space:

- Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Determines the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction while maintaining optimal objective value [13]

- Solution Space Kernel (SSK): Identifies a bounded, low-dimensional kernel that facilitates geometric interpretation of the solution space [13]

- Extreme Pathway/Elementary Mode Analysis: Finds a vector basis that completely spans the solution space [13]

The SSK approach specifically addresses unbounded fluxes common in metabolic models by separating them into ray vectors and focusing on the bounded kernel containing biologically relevant flux ranges [13].

Sampling Methods for Solution Space Characterization

Multiple computational approaches have been developed to map the feasible steady-state flux space:

Hit-and-Run Sampler [14]:

- Starts with a point inside the coordinate space

- Generates new points by iterative steps in random directions

- Projects points into flux space and tests boundary constraints

- Implements variable step size for efficient sampling

Geometric Sampler [14]:

- Identifies flux cone corners using linear programming with randomized objective functions

- Samples along edges between corners to define cone boundaries

- Iteratively samples toward the center of the cone

- Facilitates visualization but lacks statistical meaning in probability distribution

Parameter Sampler for Dynamic Models [14]:

- Samples kinetic parameters and concentrations using log-normal distributions

- Enables mapping of allowed steady states in dynamic formulations

- Allows constrained parameter variation within defined ranges

Extensions and Refinements to Classical FBA

Incorporating Additional Biological Constraints

Table 1: Advanced FBA Formulations and Their Applications

| Method | Key Features | Applications in E. coli Metabolism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| flexFBA | Removes fixed proportion between biomass reactants; allows independent production of process metabolites | Modeling metabolite production in non-wild-type proportions; single-cell modeling | [16] |

| tFBA | Removes fixed proportion between reactants and byproducts; enables transient behavior modeling | Simulating transitions between metabolic steady states; integrated whole-cell modeling | [16] |

| ECMpy | Incorporates enzyme constraints based on availability and catalytic efficiency | Capping unrealistic flux predictions; modeling engineered enzymes | [17] |

| DFBA | Combines FBA with differential equations for extracellular metabolites | Simulating batch processes; dynamic bioprocess optimization | [18] [19] |

| rFBA | Integrates regulatory constraints with metabolic networks | Predicting metabolic responses to genetic perturbations | [20] |

Hybrid Modeling Approaches

Recent advances have integrated machine learning with constraint-based models to enhance predictive power. Neural-mechanistic hybrid models embed FBA within artificial neural networks, enabling learning from flux distributions while respecting mechanistic constraints [21]. These approaches address a critical limitation of classical FBA: the conversion of medium composition to uptake fluxes [21]. The hybrid models require training set sizes orders of magnitude smaller than classical machine learning methods while systematically outperforming standard constraint-based models [21].

Diagram 2: Architecture of neural-mechanistic hybrid models showing integration of machine learning with FBA.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Implementing Enzyme-Constrained FBA

The ECMpy workflow provides a standardized approach for incorporating enzyme constraints into genome-scale metabolic models of E. coli [17]:

Model Preparation:

- Obtain a curated genome-scale model (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli K-12 MG1655)

- Split reversible reactions into forward and reverse reactions to assign direction-specific kcat values

- Separate reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into independent reactions

Parameter Acquisition:

- Calculate molecular weights using protein subunit composition from EcoCyc

- Obtain protein abundance data from PAXdb

- Acquire kcat values from BRENDA database

- Set protein mass fraction constraint (typically 0.56 for E. coli)

Implementation of Enzyme Constraints:

- Add total enzyme capacity constraint based on measured protein fraction

- Incorporate enzyme-specific constraints using kcat values and molecular weights

- Modify kinetic parameters to reflect engineered enzymes (e.g., SerA, CysE for L-cysteine production)

Simulation and Analysis:

- Perform FBA with lexicographic optimization (biomass growth followed by product formation)

- Conduct flux variability analysis to identify flexible reactions

- Compare predictions with experimental data

Protocol for Dynamic FBA Implementation

Dynamic FBA extends standard FBA to simulate time-dependent processes [18] [19]:

Initialization:

- Define initial biomass and extracellular metabolite concentrations

- Set uptake kinetic parameters for extracellular substrates

Time-Stepping Loop:

- Calculate current uptake bounds based on extracellular concentrations

- Solve FBA problem to determine intracellular fluxes and growth rate

- Update biomass using computed growth rate: dB/dt = μ·B

- Update extracellular metabolites using computed exchange fluxes: dC/dt = v_exchange·B

- Advance to next time step

Termination:

- Stop simulation when nutrients depleted or target time reached

- Output time courses of biomass, metabolites, and fluxes

This approach is particularly valuable for modeling E. coli fermentations where changing substrate concentrations significantly impact metabolic fluxes.

Research Reagent Solutions for FBA Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for E. coli FBA

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in FBA Research | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Models | iML1515, EcoCyc-based reconstructions | Provides stoichiometric matrix for E. coli metabolism | [17] |

| Enzyme Kinetic Data | BRENDA database, UniKP predictions | Parameterizes enzyme-constrained models | [17] |

| Protein Abundance Data | PAXdb, experimental proteomics | Constrains total enzyme allocation | [17] |

| Software Tools | COBRApy, ECMpy, SSKernel | Implements FBA and solution space analysis | [13] [17] |

| Experimental Flux Data | 13C metabolic flux analysis | Validates FBA predictions | [14] |

| Media Composition Databases | LB, SM1, M9 minimal media | Defines uptake constraints for simulations | [17] |

Applications to E. coli Central Carbon Metabolism

Constraint-based modeling of E. coli central carbon metabolism has enabled numerous applications in metabolic engineering and basic research. Comparative analyses of dynamic and constraint-based formulations of the same E. coli central carbon model have demonstrated equivalence in their steady-state solution spaces when unconstrained [14] [15]. However, incorporating partial kinetic information allows dynamic models to generate additional constraints that reduce the solution space and eliminate infeasible solutions.

Implementation of enzyme constraints using the ECMpy workflow has proven particularly valuable for modeling engineered E. coli strains for L-cysteine production [17]. By modifying kcat values and gene abundance parameters to reflect mutant enzymes (SerA, CysE, EamB), researchers can more accurately predict metabolic fluxes and optimize production strategies. These approaches successfully address the common FBA limitation of predicting unrealistically high fluxes by accounting for enzyme availability and catalytic capacity.

The steady-state assumption remains central to all these applications, providing a tractable framework for analyzing complex metabolic networks while maintaining biological relevance for E. coli growing under constant conditions. Ongoing development of hybrid dynamic-constraint-based methods continues to expand the applicability of FBA to transient processes and changing environmental conditions.

Key Metabolite Hubs and Their Regulatory Roles in Flux Control

This technical guide examines the critical role of metabolite hubs in controlling metabolic flux within Escherichia coli central carbon metabolism. Metabolites function not merely as passive intermediates but as active regulators of flux through allosteric modulation, post-translational modification, and transcriptional regulation. Understanding these regulatory mechanisms is paramount for rational metabolic engineering and therapeutic intervention. Framed within the context of flux balance analysis (FBA) research, this review synthesizes contemporary insights into metabolite-protein interactions, quantitative flux control analysis, and computational frameworks for predicting flux distributions. We provide detailed methodologies for profiling metabolite interactions, summarize key regulatory metabolites in tabular form, and present essential research tools for investigating flux control.

Cellular metabolism is a dynamic network where metabolic fluxes—the rates at which metabolites are transformed through biochemical reactions—are tightly regulated to maintain homeostasis and optimize fitness. In E. coli central carbon metabolism, flux control emerges from a complex interplay between stoichiometric constraints, enzyme kinetics, and regulatory mechanisms [22]. The directionality and magnitude of metabolic flows are influenced by multiple overlapping layers of control, including gene expression regulating enzyme abundance, post-translational modifications altering enzyme activity, and allosteric regulation through metabolite-protein interactions [23] [22].

Constraint-based modeling approaches, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), have become indispensable for computing metabolic fluxes at genome-scale. FBA employs the stoichiometric matrix of the metabolic network to identify flux distributions that optimize cellular objectives, typically biomass production, under steady-state assumptions [17] [24]. The well-curated E. coli K-12 model iML1515 encompasses 1,515 genes, 2,719 metabolic reactions, and 1,192 metabolites, providing a comprehensive framework for flux analysis [17]. However, traditional FBA often predicts unrealistically high fluxes, necessitating the incorporation of enzyme constraints to cap fluxes based on enzyme availability and catalytic efficiency [17]. Recent advances, such as enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA), demonstrate that flux changes correlate more strongly with pathway-level changes in enzyme levels than with individual enzyme variations, highlighting the systemic nature of flux control [25].

Key Metabolite Hubs in Central Carbon Metabolism

Metabolite hubs are molecules that occupy central positions in metabolic networks and exert disproportionate influence on flux regulation. These hubs often act at branch points, connecting multiple pathways, and serve as allosteric effectors or substrates for modification reactions. Their regulatory function allows cells to rapidly coordinate metabolic activity with environmental and energetic conditions.

Table 1: Key Regulatory Metabolites in E. coli Central Carbon Metabolism

| Metabolite | Pathway Context | Regulatory Role | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate | Glycolysis | Flux sensor; regulates carbon catabolite repression hierarchy [26] | Correlation with total carbon-uptake flux [26] |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) | Calvin cycle, Glycolysis | Feed-forward activator of F/SBPase in reducing conditions; inhibitor under oxidizing conditions [23] | LiP-SMap interaction profiling; in vitro enzyme assays in Synechocystis and Cupriavidus necator [23] |

| α-Ketoglutarate | TCA Cycle | Flux sensor; indicator of nitrogen and carbon status [26] | Correlation analysis of flux and metabolite concentrations [26] |

| Glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) | Glycolysis, Pentose Phosphate Pathway | Allosteric activator of Cupriavidus necator F/SBPase; species-specific regulation [23] | LiP-SMap and enzyme activity assays showing species-specific effects [23] |

| ATP | Energy Metabolism | Inhibitor of cyanobacterial phosphoketolase; regulates dark metabolism [23] | In vitro enzyme characterization [23] |

These metabolite hubs enable fine-tuning of pathway fluxes through multiple mechanisms. For instance, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate exhibits condition-dependent regulation, enhancing F/SBPase activity under reducing conditions while promoting enzyme aggregation and inhibition under oxidizing conditions [23]. This dual role demonstrates how metabolites can integrate redox status with flux control. Similarly, the concentration of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate serves as a proxy for glycolytic flux, influencing the hierarchical utilization of carbon sources through carbon catabolite repression (CCR) [26].

Methodologies for Profiling Metabolite-Regulator Interactions

Limited Proteolysis-Small Molecule Mapping (LiP-SMap)

Limited Proteolysis-Small Molecule Mapping (LiP-SMap) is a high-throughput proteomics technique for identifying metabolite-protein interactions on a proteome-wide scale. This method detects structural changes in proteins upon metabolite binding, revealing potential allosteric regulatory sites [23].

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Cultures are harvested during exponential growth and lysed. Proteomes are extracted and filtered to remove endogenous metabolites (>90% removal), then resuspended in buffer containing 1 mM MgClâ‚‚ [23].

- Metabolite Treatment: The proteome extract is divided into aliquots. Treatment groups receive the metabolite of interest (typically at 1 mM and 10 mM concentrations), while control groups receive buffer only [23].

- Limited Proteolysis: Samples undergo partial digestion with proteinase K, which cleaves accessible regions of proteins. Metabolite binding alters protein conformation and protease accessibility [23].

- Complete Digestion: The reaction is stopped, followed by complete digestion with trypsin and LysC endopeptidases to generate peptides for mass spectrometry analysis [23].

- LC-MS/MS and Data Analysis: Peptides are quantified using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Proteins with significantly altered peptide profiles in metabolite-treated versus control samples are classified as metabolite-interacting [23].

The LiP-SMap technique was successfully applied to four autotrophic bacteria, including Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and Cupriavidus necator, identifying interactions between Calvin cycle enzymes and metabolites such as GAP and G6P. The method typically detects 8,000-15,000 peptides per experiment, with approximately 5 peptides coverage per protein on average. For Calvin cycle enzymes, coverage averages 14 peptides per enzyme with approximately 50% sequence coverage [23].

Constraint-Based Modeling with Enzyme Constraints

Flux Balance Analysis with enzyme constraints incorporates kinetic and proteomic data to improve flux prediction accuracy. The ECMpy workflow for E. coli implements these constraints without altering the stoichiometric matrix of the base metabolic model (e.g., iML1515) [17].

Implementation Protocol:

Model Preparation:

Parameter Incorporation:

- Obtain enzyme molecular weights from EcoCyc based on subunit composition [17].

- Acquire Kcat values from BRENDA database and protein abundance data from PAXdb [17].

- Set the total protein fraction available for metabolic enzymes (e.g., 0.56 in E. coli) [17].

- Modify parameters (Kcat, gene abundance) to reflect engineering manipulations (e.g., removal of feedback inhibition in SerA, CysE) [17].

Flux Optimization:

- Perform lexicographic optimization: first optimize for biomass, then constrain growth to a percentage (e.g., 30%) of optimal before optimizing for product formation (e.g., L-cysteine export) [17].

- Apply constraints on uptake reactions to reflect medium conditions (e.g., SM1 + LB broth with thiosulfate) [17].

This approach significantly enhances flux prediction realism by accounting for enzyme limitation effects. For instance, incorporating enzyme constraints revealed that thiosulfate assimilation pathways were missing from the iML1515 model, necessitating gap-filling to accurately model L-cysteine production [17].

Diagram 1: LiP-SMap workflow for identifying metabolite-protein interactions.

Computational Frameworks for Flux Analysis

Enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA)

Enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA) is an algorithm that predicts relative reaction fluxes by integrating proteomic or transcriptomic data at the pathway level rather than considering individual reactions or the entire network in isolation [25]. The method operates on the principle that flux changes correlate most strongly with pathway-level enzyme expression changes.

Algorithm Implementation:

- Data Integration: Incorporate enzyme expression data (proteomic or transcriptomic) for reactions in the metabolic network.

- Pathway-Level Integration: For each reaction of interest (ROI), aggregate expression data from neighboring reactions within a defined pathway distance.

- Distance Optimization: Employ optimized distance parameters that govern the pathway length over which expression data is integrated, giving greater weight to enzymes catalyzing reactions closer to the ROI.

- Flux Prediction: Compute relative flux levels using the integrated expression values, accounting for network topology and mass balance constraints.

eFPA was validated using Saccharomyces cerevisiae datasets containing simultaneous flux and enzyme measurements across 25 conditions. The method demonstrated superior performance in predicting relative flux levels compared to alternatives that focus solely on individual reactions or entire-network integration [25]. When applied to human tissue data, eFPA generated consistent predictions using either proteomic or transcriptomic datasets and effectively handled the sparsity and noisiness of single-cell RNA-seq data [25].

Flux-Dependent Graph Theory

Flux-dependent graphs provide a network-based framework for analyzing metabolic flux distributions that incorporates reaction directionality and environmental context [27]. Unlike structural metabolic graphs, flux-dependent graphs represent the actual flow of metabolites from source to target reactions under specific conditions.

Graph Construction Methodology:

- Reaction Unfolding: Split each reaction into forward and reverse directions, creating an expanded reaction set.

- Mass Flow Graph (MFG) Definition: Construct a directed graph where:

- Nodes represent reactions (both forward and reverse directions)

- Directed edges connect reactions if a metabolite produced by the source reaction is consumed by the target reaction

- Edge weights correspond to flux values (in mass per time) obtained from FBA simulations [27]

- Contextualization: Incorporate condition-specific flux distributions from FBA solutions for different environmental conditions (e.g., varying carbon sources, genetic perturbations).

The MFG framework successfully revealed systemic changes in network topology and community structure across different growth conditions in E. coli central carbon metabolism. For example, analysis of MFGs under different carbon sources captured the re-routing of metabolic flows and identified reactions that gained importance in specific environments [27].

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Flux Analysis Methods

| Method | Primary Inputs | Key Features | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Stoichiometric matrix, Exchange constraints | Predicts absolute fluxes; optimization-based; steady-state assumption [17] [24] | Genome-scale flux prediction; Gene essentiality analysis [24] | Often predicts unrealistically high fluxes; Requires objective function [17] |

| Enzyme-Constrained FBA | Stoichiometric matrix, Kcat values, Enzyme abundances | Caps fluxes based on enzyme capacity; More realistic flux predictions [17] | Metabolic engineering; Understanding proteome allocation [17] | Limited transporter kinetic data; Parameter uncertainty [17] |

| Enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA) | Proteomic/Transcriptomic data | Pathway-level integration; Predicts relative fluxes; Handles sparse data [25] | Tissue-specific flux prediction; Single-cell flux analysis [25] | Requires training data; Relative rather than absolute fluxes [25] |

| Mass Flow Graphs (MFG) | FBA flux distributions | Directional flow representation; Context-specific connectivity [27] | Analysis of flux rerouting; Community structure identification [27] | Dependent on quality of FBA solution [27] |

Diagram 2: Computational workflow integrating multiple flux analysis methods.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolite Flux Studies

| Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example Source/Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Computational Model | Provides stoichiometric framework for FBA; Catalogs metabolic network components [17] [24] | iML1515 for E. coli K-12 (2,719 reactions, 1,192 metabolites) [17] |

| Enzyme Kinetic Databases | Database | Source of enzyme catalytic constants (Kcat) for constraint-based modeling [17] | BRENDA database [17] |

| Protein Abundance Data | Database | Provides enzyme concentration constraints for ecFBA [17] | PAXdb (protein abundance database) [17] |

| Metabolite-Protein Interaction Mapping | Experimental Method | Identifies allosteric regulatory interactions on proteome-wide scale [23] | LiP-SMap (Limited Proteolysis-Small Molecule Mapping) [23] |

| Pathway Databases | Knowledgebase | Curated information on metabolic pathways, enzymes, and metabolites [17] [24] | EcoCyc for E. coli K-12 metabolism [24] |

| Flux Analysis Software | Computational Tool | Implements FBA, parsimonious FBA, and related algorithms [17] | COBRApy package for Python [17] |

| Enzyme Constraint Modeling Tools | Computational Workflow | Integrates enzyme constraints into metabolic models without altering stoichiometry [17] | ECMpy workflow [17] |

Metabolite hubs serve as critical control points in E. coli central carbon metabolism, integrating thermodynamic, kinetic, and regulatory information to shape metabolic fluxes. The experimental and computational methodologies reviewed—from LiP-SMap for mapping metabolite-protein interactions to enzyme-constrained FBA and flux-dependent graph theory for contextual flux prediction—provide researchers with powerful tools to decipher these complex regulatory networks. As these technologies mature and integrate, they promise to accelerate metabolic engineering efforts and enhance our fundamental understanding of flux control principles. Future directions include developing more sophisticated multi-omic integration frameworks, improving the annotation of transporter kinetics in models, and creating dynamic extensions of constraint-based approaches to capture metabolic transitions.

Building and Reconstructing Core Metabolic Models (CMMs) from Genomic Data

Within the context of E. coli central carbon metabolism flux balance analysis (FBA) research, Core Metabolic Models (CMMs) represent strategically streamlined versions of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) that focus exclusively on central metabolic pathways essential for energy production and biosynthesis of primary building blocks. The reconstruction of CMMs has emerged as a critical methodology for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to overcome the limitations of GEMs, which often contain thousands of reactions that can generate biologically unrealistic predictions and are computationally challenging for advanced analysis techniques [6]. Unlike comprehensive GEMs, CMMs deliberately concentrate on high-flux metabolic pathways that are central to maintaining and reproducing the cell, making them particularly valuable for metabolic engineering applications where interpretability and computational efficiency are paramount.

The "Goldilocks" principle of CMM development—creating models that are "just right" in complexity—has gained substantial traction in systems biology. These intermediate-scale models strike a careful balance between the broad coverage of GEMs and the precision of small-scale kinetic models. For E. coli research specifically, CMMs typically encompass central carbon metabolism, amino acid biosynthesis, nucleotide synthesis, and energy generation pathways, while deliberately excluding peripheral degradation pathways, complex biomass component synthesis, and de novo cofactor biosynthesis [6]. This selective approach enables researchers to perform sophisticated analyses such as enzyme-constrained FBA, elementary flux mode analysis, and thermodynamic profiling that would be computationally prohibitive with full GEMs, thereby accelerating the design and optimization of microbial cell factories for pharmaceutical production.

Computational Framework for CMM Reconstruction

The reconstruction of high-quality Core Metabolic Models begins with the acquisition and meticulous curation of foundational genomic and biochemical data. The process leverages publicly available genome-scale reconstructions as starting templates, with the most recent E. coli K-12 MG1655 GEM (iML1515) serving as an authoritative reference containing 1,877 metabolites and 2,712 reactions mapped to 1,515 genes [6]. Model developers must extract a curated subset of reactions and metabolites representing core metabolic functionality through both algorithmic reduction and manual curation approaches. Essential database annotations must be updated and expanded to include comprehensive links to external biochemical databases, enabling cross-referencing and validation of model components. Additionally, the integration of quantitative biological data—including thermodynamic constants (reaction Gibbs free energies), kinetic parameters (enzyme kcat values), and regulatory information (allosteric regulation, gene regulatory rules)—transforms a basic stoichiometric model into a data-enriched computational framework capable of simulating realistic metabolic behaviors [6].

The manual curation phase represents the most critical step in CMM development, requiring domain expertise to resolve inconsistencies, correct erroneous annotations based on recent literature, and ensure biochemical accuracy throughout the network. This process includes verifying reaction directionality under physiological conditions, confirming gene-protein-reaction associations, and validating cofactor specificity for enzymatic reactions. For E. coli CMMs specifically, special attention must be paid to central carbon metabolism components including glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, TCA cycle, and electron transport chain, as these pathways form the core energy metabolism that drives biosynthetic capacities. The final product of this intensive curation is a compact yet comprehensive metabolic network that faithfully represents the organism's core metabolic capabilities while maintaining computational tractability.

Table 1: Key Data Sources for E. coli Core Metabolic Model Reconstruction

| Data Category | Specific Sources | Application in CMM Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Data | iML1515 GEM, EcoCyc, BioCyc | Template for reaction and gene content; biochemical pathway reference |

| Proteomic Data | Uniprot, PDB, BRENDA | Enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat values); protein complex organization |

| Thermodynamic Data | eQuilibrator, TECRDB | Reaction Gibbs free energy calculations; directionality constraints |

| Metabolomic Data | PubChem, ChEBI, HMDB | Metabolite structure and identity; compartmentalization information |

| Phenotypic Data | literature growth assays | Model validation under different nutrient conditions |

Reconstruction Workflow and Computational Tools

The technical workflow for reconstructing a Core Metabolic Model follows a systematic, iterative process that transforms raw genomic data into a functional, computable metabolic network. The process begins with the definition of model scope—determining which metabolic pathways constitute the "core" metabolism based on the research objectives. For E. coli central carbon metabolism studies, this typically includes pathways essential for growth on minimal media with glucose as the sole carbon source. The subsequent reaction network assembly involves extracting relevant reactions from a template GEM, with tools like COBRApy facilitating this extraction through programmable interfaces [6]. The network refinement stage involves gap-filling (identifying and adding missing reactions necessary for metabolic functionality), mass and charge balancing of all reactions, and defining the biomass objective function that represents cellular growth requirements.

Following network assembly, the model annotation phase enriches the model with extensive metadata, including database identifiers, literature references, and parameter sources. This critical step ensures model reproducibility and interoperability with other systems biology resources. The constraint implementation establishes the mathematical framework for constraint-based modeling, including the stoichiometric matrix (S), flux boundary conditions (vmin, vmax), and gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules that define how gene expression regulates metabolic capabilities. Finally, the model validation employs experimental data to verify predictive accuracy, including comparison of simulated growth rates with experimental measurements, assessment of gene essentiality predictions, and testing of carbon source utilization capabilities. This comprehensive workflow produces a CMM that faithfully represents the organism's core metabolism while maintaining computational efficiency for advanced analysis.

CMM Reconstruction Workflow: Systematic process for building core metabolic models from genome-scale templates.

Experimental Design and Analytical Protocols

Flux Balance Analysis Implementation

Flux Balance Analysis represents the cornerstone analytical technique for interrogating Core Metabolic Models, enabling researchers to predict metabolic flux distributions under steady-state assumptions. The mathematical foundation of FBA derives from mass balance constraints, where the stoichiometric matrix (S) defines the relationship between metabolites and reaction fluxes (v), resulting in the equation S·v = 0. This underdetermined system is solved by optimizing an objective function—typically biomass maximization for microbial growth simulations—subject to additional constraints including reaction reversibility and substrate uptake rates [28]. For E. coli central carbon metabolism studies, FBA implementation begins with defining the physiological constraints, including glucose uptake rate (typically 10 mmol/gDW/hr), oxygen availability (aerobic: 20 mmol/gDW/hr; anaerobic: 0 mmol/gDW/hr), and ATP maintenance requirements (ATPM: 8.39 mmol/gDW/hr) [28].

The practical implementation of FBA requires specialized computational tools that balance usability with analytical power. Escher-FBA provides a web-based interface that allows interactive FBA simulations directly within metabolic pathway visualizations, enabling users to set flux bounds, knock out reactions, and modify objective functions without programming [28]. For more advanced applications, COBRApy offers a Python-based programming environment with extensive functionality for constraint-based modeling, while COBRA Toolbox provides similar capabilities in MATLAB [6]. The experimental workflow involves sequentially testing different environmental conditions—such as varying carbon sources or oxygen availability—and analyzing the resulting flux distributions to identify metabolic bottlenecks, evaluate pathway utilization, and predict gene essentiality. For drug development applications, FBA can simulate the metabolic effects of enzyme inhibition, helping researchers identify potential drug targets and anticipate resistance mechanisms.

Table 2: Standard Constraints for E. coli Central Carbon Metabolism FBA

| Constraint Type | Reaction ID | Aerobic Condition | Anaerobic Condition | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Source | EXglcDe | -10 | -10 | mmol/gDW/hr |

| Oxygen Uptake | EXo2e | -20 | 0 | mmol/gDW/hr |

| ATP Maintenance | ATPM | 8.39 | 8.39 | mmol/gDW/hr |

| Biomass Function | BIOMASSEciML1515core75p37M | Maximize | Maximize | 1/hr |

Advanced Analytical Techniques

Beyond conventional FBA, Core Metabolic Models support a sophisticated suite of advanced analytical techniques that provide deeper insights into metabolic network properties and behaviors. Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) determines the minimum and maximum possible flux through each reaction while maintaining optimal objective function value, identifying reactions with rigidly determined fluxes versus those with operational flexibility. Elementary Flux Mode (EFM) analysis identifies all minimal, genetically independent flux distributions capable of supporting steady-state operation, providing a comprehensive decomposition of network functionality that reveals all potential metabolic routes between substrates and products [6]. For E. coli central carbon metabolism, EFM analysis can elucidate the complex interplay between glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and TCA cycle under different physiological conditions.

Thermodynamic analysis incorporates reaction Gibbs free energy values to determine thermodynamically feasible flux directions and identify potential energy bottlenecks within metabolic networks. This approach adds crucial physical constraints that improve the biological realism of flux predictions. Enzyme-constrained FBA integrates proteomic limitations by incorporating enzyme turnover numbers (kcat values) and molecular weights to account for the metabolic costs of enzyme synthesis, effectively linking metabolic flux capacity to proteomic resource allocation [6]. For drug development applications, context-specific model reconstruction techniques leverage transcriptomic or proteomic data to extract metabolic networks representative of specific physiological states, disease conditions, or environmental perturbations, enabling researchers to build patient-specific or disease-specific models for personalized therapeutic development [29] [30].

CMM Analytical Techniques: Advanced methods for interrogating core metabolic models and their applications.

Visualization and Data Integration Platforms

Escher Metabolic Mapping Tool

The Escher platform represents an essential tool for visualizing and analyzing Core Metabolic Models, providing web-based interactive pathway maps that dramatically enhance model interpretability and communication. Escher's three foundational capabilities include: (1) rapid pathway map design with data-driven suggestions for pathway completion, (2) visualization of multi-omics data directly on associated metabolic reactions and pathways, and (3) leveraging modern web technologies for adaptable, shareable, and embeddable visualizations [31] [32]. For E. coli central carbon metabolism research, Escher provides pre-built maps of core metabolic pathways that can be customized to highlight specific flux distributions, gene expression patterns, or metabolite concentrations. The platform supports multiple data visualization modes, including reaction data (flux distributions), metabolite data (concentration measurements), and gene data (transcriptomic or proteomic measurements), each with customizable color scales and sizing options to represent quantitative values intuitively.

Escher's builder functionality enables researchers to construct custom pathway maps through a semi-automated process that suggests subsequent reactions to add based on loaded model content and experimental data. This feature significantly accelerates the map creation process while ensuring biochemical accuracy. The tool's data integration capabilities include support for CSV and JSON file formats, with special handling of gene reaction rules that define how isozymes (OR rules) and protein complexes (AND rules) translate gene expression data into reaction activity predictions [31]. For publication and presentation purposes, Escher provides multiple export options including SVG (for editable vector graphics), PNG (for quick sharing), and GIF (for animated flux visualizations). The recent integration of animation features using the GreenSock Animation Platform enables dynamic visualization of flux changes over time or across conditions, further enhancing the platform's utility for exploring and communicating metabolic behaviors [31].

Multi-Omics Data Integration Framework

The analytical power of Core Metabolic Models is substantially enhanced through the integration of multi-omics data, which provides contextual constraints and validation benchmarks for model predictions. The multi-omics integration framework combines genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and fluxomic data layers to build a comprehensive representation of cellular physiological states [33]. For E. coli central carbon metabolism studies, transcriptomic data (RNA-Seq) can be used to infer metabolic activity levels through algorithms like GIMME, iMAT, or INIT, while proteomic data provides direct measurement of enzyme abundance constraints. Metabolomic data offers snapshots of intracellular metabolite pool sizes that can inform thermodynamic analyses and identify potential regulatory bottlenecks.

The technical implementation of multi-omics integration involves data normalization to establish comparable units across different measurement platforms, statistical transformation to address platform-specific noise characteristics, and systematic mapping of omics features to model components using standardized identifiers. For gene expression data, this requires mapping transcript IDs to model gene identifiers; for proteomic data, matching protein accessions to enzyme complexes in the model; and for metabolomic data, aligning measured metabolite features with model metabolite IDs using standardized nomenclature systems like BiGG or MetaNetX [30]. The resulting data-integrated models can simulate condition-specific metabolic behaviors, predict metabolic adaptations to genetic or environmental perturbations, and identify key regulatory nodes that control flux distributions. For drug development applications, this approach enables researchers to model the metabolic effects of therapeutic interventions, identify biomarkers of drug efficacy or toxicity, and understand how individual genetic variations might influence treatment responses.

Applications in Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Development

Metabolic Engineering and Strain Design

Core Metabolic Models have become indispensable tools for metabolic engineering, providing a computational framework for designing microbial cell factories with optimized production capabilities. The growth-coupled selection approach represents a particularly powerful application, where production of a target compound is genetically linked to cellular growth through strategic gene knockouts that create auxotrophies or force flux through engineered pathways [11]. For E. coli-based bioproduction, CMMs enable in silico prediction of optimal gene knockout combinations that maximize product yield while maintaining cellular viability. This methodology has been successfully applied to enhance production of numerous high-value compounds including organic acids, amino acids, biofuels, and pharmaceutical precursors. The modular pathway engineering framework extends this approach by dividing metabolic networks into functional modules (e.g., precursor supply, cofactor regeneration, product conversion) that can be independently optimized before reintegration into the production host [34].

The implementation of model-guided metabolic engineering follows an iterative design-build-test-learn cycle that continuously refines strain designs based on experimental validation. In the design phase, CMM simulations identify candidate genetic modifications that theoretically improve product yields. The build phase implements these modifications using advanced genetic engineering tools like CRISPR-Cas9. The test phase characterizes the resulting strains using omics technologies and fermentation studies. Finally, the learn phase integrates experimental data back into the model to improve its predictive accuracy and generate refined designs for the next cycle [34]. For pharmaceutical applications, this approach has been used to engineer E. coli strains for efficient production of antibiotic precursors, therapeutic protein expression, and biosynthesis of complex natural products with medicinal properties. The availability of well-curated E. coli CMMs specifically designed for central carbon metabolism analysis has significantly accelerated these engineering efforts by providing high-confidence predictions for flux redistribution in response to genetic interventions.

Live Biotherapeutic Product Development

The application of Core Metabolic Models in pharmaceutical development has expanded beyond traditional metabolic engineering to include the emerging field of live biotherapeutic products (LBPs)—beneficial live microorganisms administered to prevent or treat human diseases. CMMs provide a powerful computational framework for LBP candidate selection by predicting metabolic capabilities, host compatibility, and therapeutic mechanisms of action [29]. For microbiome-based therapeutics, CMMs can simulate the complex metabolic interactions between LBP candidates, resident gut microbiota, and host cells, helping researchers identify strains with optimal persistence, colonization, and metabolite production profiles. The AGORA2 resource, which contains curated strain-level GEMs for 7,302 human gut microbes, serves as an invaluable starting point for these analyses [29].

The model-guided LBP development pipeline involves multiple stages where CMMs provide critical decision support. During candidate screening, models predict therapeutic potential by simulating production of beneficial metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids for inflammatory bowel disease) or consumption of detrimental metabolites. For quality assessment, models evaluate growth characteristics under manufacturing conditions and gastrointestinal stress tolerance. Safety evaluation involves predicting potential for harmful metabolite production or adverse metabolic interactions with host systems [29]. For personalized LBP development, context-specific models derived from patient-specific microbiome data can identify optimal strain combinations tailored to individual microbial backgrounds. This approach is particularly valuable for conditions like Parkinson's disease where microbiome alterations have been documented, enabling the design of LBPs that specifically address individual metabolic deficiencies [29].

Table 3: CMM Applications in Pharmaceutical Development

| Application Area | CMM Utility | Specific Methodologies |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Target Identification | Essential gene prediction | Single and double gene knockout simulations; synthetic lethality analysis |

| Toxicology Assessment | Prediction of off-target metabolic effects | Simulation of enzyme inhibition; toxicity metabolite screening |

| Personalized Medicine | Patient-specific metabolic modeling | Integration of genomic variants; context-specific model extraction |

| Microbiome Therapeutics | Host-microbe interaction modeling | Community modeling; metabolite exchange prediction |

| Bioprocess Optimization | Prediction of nutrient requirements | Media optimization; growth rate simulation under bioreactor conditions |

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CMM Reconstruction and Analysis

| Research Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| COBRApy | Python package for constraint-based modeling | Primary tool for CMM reconstruction, simulation, and analysis [6] |

| Escher | Web-based pathway visualization | Interactive mapping of flux distributions and omics data [31] |

| Escher-FBA | Interactive FBA simulation environment | Browser-based FBA without programming; ideal for education and prototyping [28] |

| iCH360 E. coli CMM | Manually curated core E. coli metabolic model | Reference model for central carbon metabolism studies [6] |

| AGORA2 | Resource of 7,302 gut microbial GEMs | Reference for LBP development and microbiome studies [29] |

| eQuilibrator | Thermodynamic database for biochemistry | Gibbs free energy calculations for reaction directionality constraints [6] |

| BRENDA | Enzyme kinetic database | kcat values for enzyme-constrained FBA [6] |

| BiGG Models | Knowledgebase of genome-scale metabolic models | Source of standardized biochemical reaction databases [28] |

| OMERO | Data management platform for microscopy | Management and analysis of metabolomics and fluxomics data |

Practical FBA and 13C-MFA: From Model Simulation to Experimental Flux Estimation

Step-by-Step Guide to Performing FBA with Different Objective Functions

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone mathematical approach in systems biology for analyzing the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network. This constraint-based modeling method enables researchers to predict organism behavior, including growth rates and metabolite production, by calculating steady-state flux distributions within biochemical networks [35] [17]. FBA operates on genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) that contain all known metabolic reactions for an organism and the genes encoding each enzyme [36]. The technique has become indispensable for microbial strain improvement, drug discovery, and understanding evolutionary dynamics [20] [37].

The fundamental premise of FBA involves applying mass-balance constraints under steady-state assumptions, where the net production and consumption of each metabolite must balance. This is represented mathematically as Sv = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the flux vector [35]. Additional constraints are applied to define irreversible reactions and nutrient uptake capabilities. Without further refinement, this underdetermined system typically has infinitely many solutions. The selection of an appropriate biological objective function is therefore critical for identifying a physiologically relevant flux distribution from this feasible solution space [38] [36].

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for performing FBA with different objective functions, using Escherichia coli central carbon metabolism as a case study. We will detail computational protocols, present quantitative comparisons of objective functions, and visualize key workflows to equip researchers with practical implementation strategies.

Foundational Concepts and Key Objective Functions

Theoretical Basis of FBA