Gap-Filling Algorithms for Metabolic Models: From Foundations to AI-Driven Applications in Biomedical Research

Genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) are powerful computational tools for predicting cellular phenotypes, but their accuracy is often limited by metabolic gaps resulting from incomplete genomic annotations and knowledge.

Gap-Filling Algorithms for Metabolic Models: From Foundations to AI-Driven Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) are powerful computational tools for predicting cellular phenotypes, but their accuracy is often limited by metabolic gaps resulting from incomplete genomic annotations and knowledge. This article provides a comprehensive overview of gap-filling algorithms, which are essential for correcting these deficiencies and creating functional metabolic networks. We explore the foundational principles behind metabolic gaps and the evolution of gap-filling methodologies, from traditional constraint-based approaches to cutting-edge artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques. The content covers practical applications in drug discovery and microbial community modeling, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges including thermodynamic feasibility and error detection, and provides a comparative analysis of validation frameworks. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review serves as both an educational primer and a technical reference for implementing gap-filling strategies to enhance metabolic model predictive power in biotechnological and biomedical contexts.

Understanding Metabolic Gaps: The Why and What of Gap-Filling in Genome-Scale Models

Defining Metabolic Gaps and Their Impact on Model Predictions

Genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) are mathematical representations of the metabolic capabilities of an organism, inferred primarily from its genome annotations [1]. These models serve as powerful frameworks for predicting biological capabilities, with applications in metabolic engineering, systems medicine, and the study of microbial communities [2]. A fundamental challenge in constructing accurate GSMMs is the presence of metabolic gaps—disconnections in the metabolic network that prevent the model from simulating known biological functions. These gaps arise primarily from incomplete genomic annotations, fragmented genome assemblies, misannotated genes, and undiscovered biochemical pathways [3] [1]. The process of gap-filling has therefore become an indispensable component of metabolic network reconstruction, essential for creating functional models that can reliably predict metabolic behaviors [2].

The presence of metabolic gaps directly compromises the predictive accuracy of GSMMs, leading to false-negative predictions where the model fails to simulate growth on known carbon sources or production of experimentally verified metabolites [1]. When left unfilled, these gaps propagate errors in downstream applications, particularly in modeling microbial communities where metabolic interactions between species are intrinsically connected [3] [1]. This technical guide examines the nature of metabolic gaps, their impact on model predictions, and the computational strategies developed to address them within the broader context of gap-filling algorithm research.

Technical Origins of Metabolic Gaps

Metabolic gaps in genome-scale models originate from several technical and biological sources:

Genome Annotation Limitations: Automated genome annotation tools often fail to identify genes encoding metabolic enzymes due to sequence divergence, domain architecture variations, or incomplete reference databases [1]. This leads to missing reactions in the draft metabolic reconstruction.

Fragmented Genomic Assemblies: Particularly in metagenomic studies, fragmented genome assemblies can result in partial pathway reconstructions where some enzymes are present while others are missing, creating topological gaps in the metabolic network [3].

Database Inconsistencies: Biochemical databases used for reconstruction (e.g., ModelSEED, MetaCyc, KEGG, BiGG) contain imbalanced reactions and thermodynamically infeasible cycles that introduce computational artifacts into the models [1].

Undiscovered Biochemistry: A significant portion of microbial metabolism remains uncharacterized, including promiscuous enzyme activities and underground metabolic pathways that are not captured in standard annotations [2].

Types of Metabolic Gaps

Metabolic gaps manifest in several distinct forms within computational models:

Dead-End Metabolites: These metabolites can be produced but not consumed (or vice versa) in the network, indicating incomplete pathways [2]. Dead-end metabolites prevent realistic flux simulations because they accumulate indefinitely or cannot be synthesized from available nutrients.

Network Disconnections: Isolated network components that cannot connect to the core metabolism or biomass formation reactions, rendering them non-functional in simulations [3].

Energy-Generating Cycles: Thermodyamically infeasible cycles that can generate energy or redox cofactors without substrate input, violating conservation laws and producing physiologically impossible predictions [1].

Table 1: Classification of Metabolic Gaps and Their Characteristics

| Gap Type | Network Manifestation | Impact on Predictions | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dead-End Metabolites | Metabolites with only production or consumption reactions | Prevents metabolite turnover; limits pathway functionality | Topological analysis of network connectivity |

| Blocked Reactions | Reactions that cannot carry flux under any condition | Reduces network capacity; creates false negative phenotypes | Flux variability analysis (FVA) |

| Missing Biomass Precursors | Inability to synthesize essential biomass components | Precludes growth prediction even when nutrients are available | Biomass reaction analysis |

| Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycles | Cyclic reaction pathways that generate energy without input | Produces physiologically impossible flux solutions | Thermodynamic constraint analysis |

Impact of Metabolic Gaps on Model Predictions

Effects on Phenotype Predictions

Metabolic gaps significantly compromise the predictive accuracy of genome-scale models across multiple dimensions:

False Negative Growth Predictions: Models with unresolved gaps fail to predict growth on carbon sources that experimentally support growth. Benchmarking studies have shown that automated reconstruction tools can have false negative rates as high as 32% for enzyme activity predictions and even higher for carbon source utilization [1].

Inaccurate Gene Essentiality Predictions: Missing reactions in essential pathways lead to incorrect identification of essential genes, with knockouts of non-essential genes appearing lethal in silico due to network gaps rather than biological reality [2].

Erroneous Metabolic Interaction Predictions: In microbial community modeling, gaps in individual member models propagate through the system, causing incorrect cross-feeding predictions and misrepresentation of community dynamics [3]. Since metabolic fluxes in multi-species communities are intrinsically connected, an error in one model can affect otherwise correctly functioning models [1].

Implications for Biotechnological and Biomedical Applications

The practical consequences of unfilled metabolic gaps extend beyond academic exercises to real-world applications:

Metabolic Engineering: Gaps in production pathways for valuable chemicals lead to suboptimal strain designs and failed bioprocesses due to inability to identify all possible metabolic routes [2].

Drug Target Identification: In infectious disease research, incomplete metabolic models of pathogens may overlook essential metabolic reactions that could serve as drug targets, reducing the effectiveness of target discovery pipelines [1].

Microbiome Research: When studying host-associated microbial communities, metabolic gaps can obscure understanding of host-microbe interactions and community stability, particularly for difficult-to-culture organisms that rely heavily on genomic inference [3].

Computational Frameworks for Gap Identification

Topological Analysis Methods

Early gap detection approaches primarily relied on network topology to identify metabolic gaps:

Dead-End Metabolite Detection: Algorithms systematically identify metabolites that serve only as reactants or only as products in the network, indicating incomplete pathways [2]. These dead-end metabolites represent locations where reactions are missing from the reconstruction.

Network Compression: Some methods simplify the metabolic network by removing currency metabolites and highly connected compounds to reveal functional gaps in pathways that are obscured in the full network [2].

Growth-Centric Gap Detection

More advanced gap detection methods evaluate model functionality against expected metabolic capabilities:

In Silico Growth Phenotyping: Models are tested for their ability to produce biomass on different nutrient conditions, with failures indicating possible gaps in metabolic pathways [1].

Function-Specific Gap Detection: Algorithms like those implemented in gapseq specifically test for the production of known fermentation products or utilization of specific carbon sources, identifying gaps when these experimentally verified capabilities are missing from the model [1].

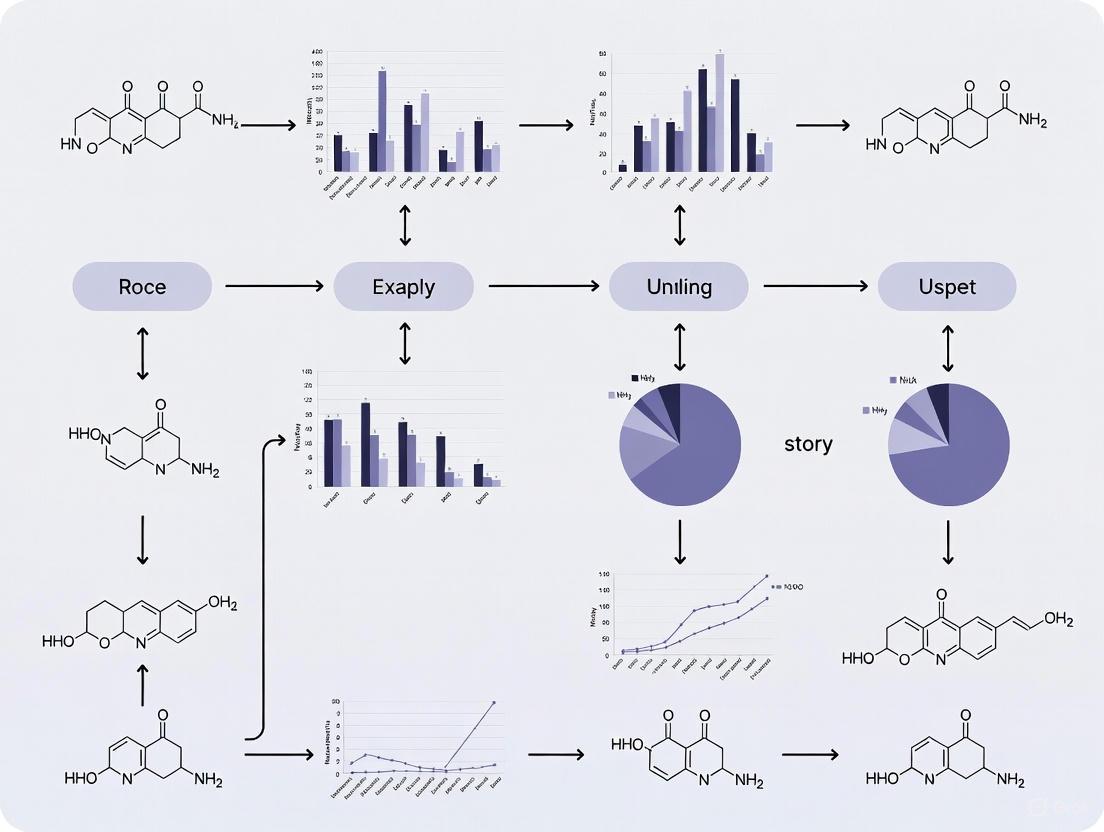

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for identifying metabolic gaps in genome-scale models:

Gap Identification Workflow

Gap-Filling Algorithms and Methodologies

Fundamental Algorithmic Approaches

Gap-filling algorithms resolve metabolic gaps by adding biochemical reactions from reference databases to restore network functionality:

Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP): Early algorithms like GapFill formulated gap-filling as a MILP problem that identified dead-end metabolites and added reactions from databases like MetaCyc to the metabolic network [3]. The objective function typically minimizes the number of added reactions while satisfying biological constraints.

Linear Programming (LP) Formulations: More recent tools like gapseq and AMMEDEUS use computationally efficient LP-based gap-filling that scales better for large metabolic networks [3] [1]. These approaches sacrifice the guarantee of minimal reaction addition for significantly reduced computation time.

Bi-Level Optimization: Methods like GLOBALFIT reformulate gap-filling as a bi-level optimization problem that simultaneously matches both growth and non-growth data sets, improving the biological relevance of added reactions [2].

Advanced Gap-Filling Strategies

Recent algorithmic advances incorporate additional biological knowledge to improve gap-filling accuracy:

Genome-Informed Gap-Filling: Tools like gapseq and CarveMe incorporate genomic context evidence such as gene co-expression, chromosomal proximity, and phylogenetic profiles to prioritize biologically plausible reactions during gap-filling [3] [1].

Community-Aware Gap-Filling: The novel approach of community gap-filling resolves metabolic gaps simultaneously across multiple organisms that coexist in microbial communities, allowing them to interact metabolically during the gap-filling process [3]. This method can predict non-intuitive metabolic interdependencies while filling gaps.

Probabilistic Reaction Addition: Algorithms like GLOBUS employ global probabilistic approaches that integrate multiple data types to assign likelihood scores to potential gap-filling reactions, reducing arbitrary additions [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Gap-Filling Algorithms and Performance Characteristics

| Algorithm | Mathematical Formulation | Key Features | Performance Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| GapFill | Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | Minimal reaction addition; database query | Guarantees minimal set of added reactions |

| FASTGAPFILL | Linear Programming (LP) | Scalable for compartmentalized models | Faster computation for large networks |

| gapseq | Linear Programming (LP) | Genomic evidence integration; pathway-informed | Higher accuracy in enzyme and carbon source prediction |

| Community Gap-Filling | Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | Multi-species gap resolution; interaction prediction | Identifies metabolic interactions in communities |

| GLOBALFIT | Bi-Level Optimization | Simultaneous fitting of multiple data types | Better reconciliation of growth/non-growth data |

The following diagram illustrates the community-level gap-filling approach that leverages metabolic interactions between species:

Community Gap-Filling Approach

Experimental Protocols for Gap Validation

High-Throughput Phenotyping for Gap Identification

Experimental data is essential both for identifying gaps and validating gap-filling solutions:

Carbon Source Utilization Assays: Phenotype microarray systems test growth on hundreds of carbon sources, providing comprehensive data for identifying missing metabolic capabilities in models [1]. Protocol: Inoculate minimal medium with standardized cell density into 96-well plates containing different carbon sources. Monitor growth turbidimetrically over 24-72 hours. Compare observed growth with in silico predictions to identify discrepancies indicating metabolic gaps.

Enzyme Activity Assays: Standardized biochemical assays verify the presence of specific enzymatic activities predicted by gap-filled models [1]. Protocol: Prepare cell-free extracts from cultured organisms. Measure enzyme activity spectrophotometrically by monitoring substrate depletion or product formation at specific wavelengths. Compare with genomic predictions to validate added reactions.

Fermentation Product Profiling: Chromatographic methods (GC-MS, HPLC) identify metabolic end products from various substrates [1]. Protocol: Grow microorganisms in defined media with target substrates. Collect supernatant at multiple growth phases. Analyze metabolite profiles using GC-MS or HPLC with appropriate standards. Identify missing secretion products in models.

Genetic Validation Approaches

Molecular methods provide direct evidence for gap-filling predictions:

Gene Knockout Studies: Targeted gene deletions test whether proposed gap-filling reactions are actually essential for specific metabolic capabilities [2]. Protocol: Design knockout constructs using homologous recombination or CRISPR-Cas9. Verify gene disruption by PCR and sequencing. Test mutants for growth phenotypes on relevant substrates.

Heterologous Expression: Cloning and expressing putative genes in model organisms can confirm their proposed metabolic functions [2]. Protocol: Amplify candidate genes from genomic DNA. Clone into expression vectors with appropriate promoters. Transform into knockout strains or model hosts. Test complementation of metabolic defects.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Gap-Filling Validation

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Validation | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal Media Formulations | Provides defined nutrient conditions for phenotyping | Carbon source utilization assays; auxotrophy testing |

| Phenotype Microarray Plates | High-throughput growth profiling | Systematic gap identification across conditions |

| Gene Knockout Constructs | Validation of essential gene predictions | Testing proposed gap-filling reactions |

| Expression Vectors | Heterologous gene expression | Functional validation of putative enzymes |

| Metabolite Standards | Chromatographic quantification | Fermentation product analysis; metabolic flux validation |

| Cell Lysis Buffers | Enzyme extraction and assay preparation | In vitro enzyme activity measurements |

Current Limitations and Future Directions

Persistent Challenges in Gap-Filling

Despite advances in gap-filling algorithms, significant limitations remain:

False Positive Predictions: Current algorithms struggle with resolving false-positive predictions where models predict growth that does not occur experimentally [2]. This may result from unknown regulatory constraints rather than metabolic capabilities.

Database Quality Issues: Inconsistencies in biochemical databases, including mass-imbalanced reactions and incorrect directionality assignments, propagate errors during gap-filling [1].

Context-Specific Metabolism: Most gap-filling approaches assume universal metabolic capabilities, but actual enzyme expression is condition-dependent and tissue-specific in multicellular organisms [2].

Emerging Approaches and Innovations

Promising research directions are addressing current gap-filling limitations:

Machine Learning Integration: New methods incorporate machine learning approaches including logistic regression, decision trees, and naive Bayes classifiers to identify missing reactions and enzymes with greater accuracy [2].

Multi-Omics Data Integration: Incorporating transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data enables context-specific model reconstruction that reflects actual metabolic states under different conditions [2].

Automated Experimental Design: Algorithms that prioritize the most informative experiments for gap resolution can optimize the trade-off between experimental effort and model improvement [2].

Metabolic gaps present a fundamental challenge in genome-scale metabolic modeling, directly impacting the predictive accuracy and practical utility of these computational frameworks. Through continued development of sophisticated gap-filling algorithms that integrate diverse biological evidence and experimental data, the research community is steadily improving the completeness and reliability of metabolic models. The integration of machine learning approaches, multi-omics data, and automated experimental design promises to further advance gap-filling capabilities, enabling more accurate biological predictions for biotechnology, biomedical research, and fundamental understanding of metabolic systems. As these methods mature, they will increasingly enable researchers to move beyond filling known gaps to discovering truly novel metabolic functions and interactions.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are powerful computational tools for representing cellular metabolism, with critical applications in biotechnology, drug discovery, and fundamental biological research. These models rely on accurate functional annotations to predict metabolic capabilities and physiological behaviors. However, significant knowledge gaps persistently undermine their predictive accuracy and utility. These gaps primarily originate from three interconnected sources: genome misannotation, incomplete databases, and missing enzyme functions. Within the context of gap-filling algorithms for metabolic models research, understanding these sources is paramount for developing effective computational strategies to address metabolic incompleteness. This technical guide examines the nature, impact, and ongoing research efforts targeting these fundamental challenges, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for advancing metabolic model reconstruction and curation.

Genome Misannotation: Propagation of Error

The Misannotation Problem

Genome misannotation represents a critical source of error in metabolic model reconstruction. It occurs when computational predictions incorrectly assign function to gene products, and these errors propagate through databases and subsequent analyses. Unlike manually curated databases like UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, which maintain minimal error rates, automated databases exhibit alarmingly high misannotation levels. One foundational study examining 37 well-characterized enzyme families found that misannotation rates in major public databases ranged from 5% to 63% across different enzyme superfamilies, with some families experiencing rates exceeding 80% [4]. This systematic overprediction of molecular function continues to plague contemporary databases despite advances in annotation methodologies.

Evidence from Experimental Validation

Recent experimental investigations continue to validate concerns regarding misannotation. A 2021 study focusing specifically on the S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase enzyme class (EC 1.1.3.15) employed high-throughput experimental screening of 122 representative sequences. The research revealed that at least 78% of sequences in this enzyme class were misannotated, with researchers confirming four alternative enzymatic activities among the misannotated sequences [5]. This demonstrates that even well-studied enzyme classes of industrial and medical relevance remain significantly affected by functional misannotation. The study further noted that misannotation within this enzyme class has increased over time, coinciding with the rapid expansion of genomic data from sequencing projects.

Table 1: Documented Misannotation Rates Across Enzyme Classes

| Enzyme Class/Superfamily | Misannotation Rate | Database | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haloacid Dehalogenase (HAD) Superfamily | 60-80% | GenBank NR, TrEMBL, KEGG | [4] |

| Enolase Superfamily | 22-24% | GenBank NR, TrEMBL, KEGG | [4] |

| S-2-hydroxyacid oxidases (EC 1.1.3.15) | 78% | BRENDA | [5] |

| Amidohydrolase (AH) Superfamily | 40-50% | GenBank NR, TrEMBL, KEGG | [4] |

Impact on Metabolic Models

In metabolic models, misannotations manifest as incorrect gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations, leading to false predictions of metabolic capabilities. Misannotation can result in both false positives (incorrectly predicting a metabolic function exists) and false negatives (overlooking existing metabolic functions). These errors directly impact essential GEM applications, including drug target identification in pathogens [6], metabolic engineering strategies for industrial biotechnology [6], and essentiality predictions in model organisms [6]. For example, in the well-characterized Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 genome, approximately 35% of genes (∼1,600 genes) lack functional annotations, creating significant gaps in metabolic reconstructions [6].

Incomplete Databases: The Limitation of Knowledge Space

Database Coverage Issues

Public databases capturing metabolic knowledge remain substantially incomplete, creating fundamental limitations for metabolic model reconstruction. NMR-based metabolic profiling studies reveal that 40-45% of spectral peaks have either no or ambiguous database matches, preventing confident metabolite identification [7]. Additionally, different databases contain significant unique content, with studies showing that 9-22% of metabolites are exclusive to individual databases [7]. This lack of consensus and coverage means that metabolic models built from different database sources may yield substantially different predictions, reflecting database-specific biases rather than biological reality.

Statistical and Technical Limitations

The interpretation of metabolic profiling data is further complicated by substantial inconsistencies in statistical analyses. Different significance measures (p-values, VIP scores, AUC values) can yield contradictory results, while data normalization techniques profoundly impact statistical outcomes [7]. These technical challenges compound the fundamental incompleteness of databases, creating additional layers of uncertainty in metabolic model reconstruction. The lack of consistency in statistical analyses of metabolomics data can lead to misleading or inconsistent interpretation of which metabolites and pathways are biologically significant [7].

Annotation Tools and Methodological Challenges

Automated annotation tools frequently rely on sequence similarity measures, which are known to produce significant false positive rates [8]. More sophisticated tools have emerged to address these limitations, such as Architect, which employs an ensemble approach combining multiple enzyme annotation tools (DETECT, EnzDP, CatFam, PRIAM, and EFICAz) to improve prediction accuracy [8]. This method demonstrates both increased precision and recall compared to individual tools, highlighting how methodological improvements can partially mitigate database limitations. Similarly, DeepECtransformer utilizes deep learning with transformer layers to predict Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, covering 5,360 EC numbers and demonstrating superior performance compared to homology-based search tools [9].

Missing Enzyme Functions: The Challenge of Unknown Biochemistry

The Scale of Unknown Biochemistry

A substantial portion of metabolic functionality remains uncharacterized, creating significant gaps in metabolic networks. Even in extensively studied model organisms, many enzymatic activities await discovery. Recent research has begun to systematically explore this unknown biochemical space through computational approaches that generate putative biochemical reactions. The ATLAS of Biochemistry represents one such effort, containing over 150,000 putative reactions between known metabolites that represent possible but not yet experimentally observed biochemistry [6]. This expanding database of hypothetical reactions provides a critical resource for gap-filling algorithms seeking to reconcile discrepancies between model predictions and experimental observations.

Computational Exploration of Missing Functions

Novel computational workflows have been developed to systematically identify and characterize missing metabolic functions. The NICEgame (Network Integrated Computational Explorer for Gap Annotation of Metabolism) workflow leverages the ATLAS of Biochemistry and genome-scale metabolic models to identify metabolic gaps and propose hypothetical biochemistry to resolve them [6]. This approach integrates thermodynamic feasibility assessments and candidate gene identification using the BridgIT tool, providing a comprehensive framework for hypothesizing missing enzyme functions. When applied to the E. coli iML1515 model, NICEgame successfully proposed 77 biochemical reactions linked to 35 candidate genes to fill 47% of identified gaps, significantly enhancing the model's predictive accuracy [6].

Deep Learning Approaches

Recent advances in deep learning have created new opportunities for predicting missing enzyme functions. DeepECtransformer uses transformer neural network architectures to predict EC numbers from amino acid sequences, demonstrating the ability to identify functional motifs and active site regions critical for enzymatic function [9]. When applied to the E. coli K-12 MG1655 genome, this approach predicted EC numbers for 464 previously un-annotated genes [9]. Similarly, the DNNGIOR (Deep Neural Network Guided Imputation of Reactomes) framework uses AI trained on >11,000 bacterial species to impute missing reactions in metabolic models, achieving an average F1 score of 0.85 for reactions present in over 30% of training genomes [10]. These AI-driven approaches represent a paradigm shift in addressing the challenge of missing enzyme functions.

Experimental Protocols for Validation and Discovery

High-Throughput Experimental Validation

Rigorous experimental validation remains essential for confirming enzymatic functions and addressing misannotation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Functional Characterization

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| FMN (Flavin Mononucleotide) | Cofactor for α-hydroxy acid oxidases | Assaying S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase activity [5] |

| S-2-hydroxyacids (e.g., glycolate, lactate) | Substrate for EC 1.1.3.15 enzymes | Functional validation of putative hydroxyacid oxidases [5] |

| Heterologous Expression Systems | Recombinant protein production | Producing uncharacterized enzymes for functional screening [9] [5] |

| LC-MS/NMR Platforms | Metabolite identification and quantification | Verifying reaction products and enzyme activities [9] [11] |

Protocol: High-Throughput Enzyme Screening

- Gene Selection: Identify target sequences from databases based on EC annotations or sequence similarity [5].

- Cloning and Expression: Clone genes into appropriate expression vectors and express in heterologous hosts (e.g., E. coli) [9] [5].

- Protein Purification: Purify recombinant proteins using affinity chromatography tags [9].

- Activity Assays: Incubate purified enzymes with putative substrates under optimized buffer conditions, monitoring product formation spectrophotometrically or via coupled assays [5].

- Substrate Profiling: Test positive enzymes against substrate panels to determine specificity and identify potential alternative functions [5].

- Kinetic Characterization: For confirmed activities, determine kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) to fully characterize enzymatic function [12].

Computational Validation Pipelines

Computational approaches provide essential triage for identifying likely misannotations before experimental validation.

Protocol: Sequence-Based Annotation Validation

- Domain Architecture Analysis: Identify protein domains using tools like Pfam; compare to domain architectures of experimentally characterized enzymes [5].

- Active Site Residue Conservation: Check conservation of catalytically essential residues across multiple sequence alignments [4].

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Construct phylogenetic trees to identify orthologs and contextualize evolutionary relationships [4].

- Similarity Thresholding: Apply stringent sequence identity thresholds (>50% for same function transfer) and evaluate bit scores for homology-based annotations [4].

- Machine Learning Prediction: Utilize tools like DeepECtransformer or Architect to generate independent function predictions for comparison [8] [9].

Diagram Title: Metabolic Gap-Filling Workflow

Integrated Solutions and Future Directions

Advanced Gap-Filling Algorithms

Next-generation gap-filling algorithms have evolved beyond simple database querying to incorporate multiple constraints and community-level metabolic interactions. The NICEgame workflow exemplifies this advanced approach, integrating seven key steps: (1) metabolite annotation harmonization, (2) GEM preprocessing and gap identification, (3) merging GEMs with the ATLAS of Biochemistry, (4) comparative essentiality analysis, (5) systematic identification of alternative biochemistry, (6) thermodynamic evaluation and ranking, and (7) candidate gene identification using BridgIT [6]. This comprehensive workflow enables researchers to systematically address metabolic gaps while prioritizing biologically plausible solutions.

Community-level gap-filling represents another significant advancement, particularly for modeling microbial communities. Traditional gap-filling algorithms resolve metabolic gaps in individual organisms, but community gap-filling approaches leverage metabolic interactions between species to resolve gaps that cannot be filled in isolation [13]. This method has been successfully applied to synthetic E. coli communities, human gut microbiota species (Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii), and environmental microbial communities, demonstrating its utility for predicting metabolic interactions that are difficult to identify experimentally [13].

Database Quality Initiatives

Addressing the fundamental issue of database incompleteness and inaccuracy requires coordinated community efforts. Research indicates that manual curation remains the gold standard for reducing misannotation, with Swiss-Prot maintaining error rates close to 0% for most enzyme families [4]. However, the scalability limitations of manual curation necessitate improved automated methods with higher precision. Ensemble approaches like those implemented in Architect show promise by leveraging the complementary strengths of multiple prediction tools [8]. Additionally, deep learning methods like DeepECtransformer can identify potentially misannotated entries in databases, flagging them for expert review and contributing to more robust knowledgebases [9].

Emerging Technologies and Research Priorities

Future progress in addressing metabolic gaps will depend on several technological and methodological advances:

- Integration of multi-omics data: Combining metabolomics with genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics to provide orthogonal evidence for gene functions [11].

- Automated model curation platforms: Developing tools that continuously update metabolic models as new annotations and evidence become available.

- Expanded biochemical space exploration: Systematically characterizing the reactivity of unassigned enzymes and orphan metabolic activities.

- Machine learning advancements: Refining deep learning architectures to better predict enzyme functions from sequence and structural features.

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of Advanced Gap-Filling Approaches

| Method | Application | Performance/Impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NICEgame | E. coli iML1515 model | Resolved 47% of gaps (77 reactions, 35 genes); 23.6% increase in essentiality prediction accuracy | [6] |

| DeepECtransformer | E. coli K-12 MG1655 | Predicted EC numbers for 464 un-annotated genes | [9] |

| Community Gap-Filling | Synthetic E. coli community | Successfully predicted metabolic interactions and restored growth in silico | [13] |

| DNNGIOR | Bacterial metabolic models | 14x more accurate for draft reconstructions; 2-9x for curated models than unweighted gap-filling | [10] |

Diagram Title: Relationship Between Gap Sources and Solutions

The challenges of genome misannotation, incomplete databases, and missing enzyme functions represent significant but addressable obstacles in metabolic modeling research. Quantitative evidence reveals alarming rates of misannotation in public databases, with some enzyme classes exceeding 80% error rates. Database incompleteness leaves 40-45% of metabolic features unidentifiable in profiling studies. Meanwhile, computational explorations suggest at least 150,000 biochemical reactions may be missing from current metabolic knowledge. Addressing these interconnected issues requires integrated approaches combining rigorous experimental validation, advanced computational methods, and community-wide curation efforts. Deep learning tools like DeepECtransformer, sophisticated gap-filling workflows like NICEgame, and community-aware algorithms demonstrate promising pathways toward more complete and accurate metabolic models. As these methodologies continue to mature, they will enhance our ability to leverage metabolic models for drug discovery, metabolic engineering, and fundamental biological insight, ultimately transforming our understanding of cellular metabolism across the tree of life.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are mathematical representations of an organism's metabolism, constructed from its annotated genome sequence. They serve as powerful tools for predicting metabolic capabilities, physiological states, and responses to genetic or environmental perturbations [14]. The reconstruction process, however, often yields models containing inconsistencies that manifest as dead-end metabolites and blocked reactions, collectively known as "gaps" [14]. These gaps arise from incomplete genomic annotations, unknown enzyme functions, and fragmented biochemical knowledge, preventing the model from achieving a steady state for all metabolites and rendering certain reactions inoperable [14] [2]. Resolving these inconsistencies through gap-filling is an indispensable step in model curation, essential for creating accurate and predictive biological models [2]. This guide details the core concepts of dead-end metabolites, blocked reactions, and the role of network connectivity within the broader context of gap-filling algorithms for metabolic models research.

Defining Dead-End Metabolites and Blocked Reactions

Classification of Dead-End Metabolites

A dead-end metabolite (or gap metabolite) is a chemical compound that, within the model, cannot reach a non-zero steady-state concentration because it is either only produced or only consumed by the network's reactions [14]. These metabolites are typically classified into primary (root) and secondary (downstream/upstream) types based on their connectivity.

Table 1: Classification of Dead-End Metabolites

| Type | Acronym | Definition | Network Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root-Non-Produced | RNP | A metabolite that is only consumed, but never produced, by any reaction in the network [14]. | Blocks all downstream consuming reactions. |

| Root-Non-Consumed | RNC | A metabolite that is only produced, but never consumed, by any reaction in the network [14]. | Blocks all upstream producing reactions. |

| Downstream-Non-Produced | DNP | A metabolite that becomes a gap as a direct consequence of an upstream RNP metabolite [14]. | Becomes blocked due to propagation from an RNP. |

| Upstream-Non-Consumed | UNC | A metabolite that becomes a gap as a direct consequence of a downstream RNC metabolite [14]. | Becomes blocked due to propagation from an RNC. |

The absence of flux through RNP or RNC metabolites can be propagated through the network, leading to secondary blocking phenomena. An RNP metabolite will prevent any reaction that consumes it from carrying flux, which may in turn cause the products of those reactions to become DNP metabolites. Similarly, an RNC metabolite will block the reactions that produce it, potentially creating UNC metabolites upstream [14].

Blocked Reactions

A reaction is defined as blocked if it cannot carry a steady-state flux other than zero under a given set of environmental conditions [14]. In mathematical terms, for a reaction ( j ) in the set of reactions ( J ):

[ j \in J{\text{Blocked}} \Leftrightarrow vj = 0 ]

where ( v_j ) is the flux through reaction ( j ). Blocked reactions are a direct consequence of dead-end metabolites, as any reaction involving a dead-end metabolite will itself be blocked [14]. The identification of these blocked reactions and their connecting gap metabolites forms isolated sets known as Unconnected Modules (UMs), which are key targets for gap-filling procedures [14].

Figure 1: The relationship between different classes of dead-end metabolites and blocked reactions. Root gaps (RNP, RNC) cause flux propagation, leading to secondary gaps (DNP, UNC), which ultimately result in blocked reactions.

Methodologies for Detection and Analysis

Constraint-Based Modeling Framework

The primary framework for analyzing GEMs is Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM). A metabolic network with ( m ) metabolites and ( n ) reactions is represented by its stoichiometric matrix ( \mathbf{N} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n} ). The steady-state mass balance constraint is then expressed as:

[ \mathbf{N} \cdot \mathbf{v} = \mathbf{0} ]

where ( \mathbf{v} ) is the vector of reaction fluxes. Additional thermodynamic and environmental constraints are applied as lower and upper bounds on individual fluxes:

[ vj^{\text{lb}} \leq vj \leq v_j^{\text{ub}} \quad \forall j \in J ]

The space of all feasible flux distributions ( F ) is thus defined as:

[ F = { \mathbf{v} \in \mathbb{R}^{n} : \mathbf{N} \cdot \mathbf{v} = \mathbf{0}, \quad vj^{\text{lb}} \leq vj \leq v_j^{\text{ub}} \ \forall j \in J } ]

A reaction is identified as blocked if its flux ( v_j ) is constrained to zero across all possible solutions within the flux space ( F ) [14].

Protocol for Identifying Dead-End Metabolites and Blocked Reactions

Step 1: Construct the Stoichiometric Matrix

- Build the ( \mathbf{N} ) matrix from the GEM, where rows correspond to metabolites and columns to reactions [14].

- Partition the reaction set ( J ) into internal fluxes ( J{\text{INT}} ) and exchange fluxes ( J{\text{EX}} ) [14].

Step 2: Scan for Root Dead-End Metabolites

- For each metabolite ( i ), examine the non-zero entries in the ( i )-th row of ( \mathbf{N} ).

- Identify RNP Metabolites: Metabolites where all associated internal reactions have non-negative stoichiometric coefficients (indicating only production) and no exchange flux allows consumption [14].

- Identify RNC Metabolites: Metabolites where all associated internal reactions have non-positive stoichiometric coefficients (indicating only consumption) and no exchange flux allows production [14].

Step 3: Propagate Flux Constraints

- For each identified RNP metabolite, set the flux of all consuming reactions to zero. Check if the products of these reactions subsequently become DNP metabolites [14].

- For each identified RNC metabolite, set the flux of all producing reactions to zero. Check if the reactants of these reactions subsequently become UNC metabolites [14].

Step 4: Identify Blocked Reactions and Unconnected Modules (UMs)

- Any reaction with flux constrained to zero after propagation is a blocked reaction [14].

- Group interconnected blocked reactions and gap metabolites into Unconnected Modules (UMs) using connected component algorithms on a bipartite graph of metabolites and reactions [14]. This simplifies visual analysis and guides subsequent gap-filling.

Step 5: Validate with Flux Variability Analysis (FVA)

- Perform FVA to compute the minimum and maximum possible flux (( vj^{\min} ), ( vj^{\max} )) for each reaction ( j ) subject to the constraints.

- A reaction is confirmed blocked if ( vj^{\min} = vj^{\max} = 0 ) [14].

The Role of Network Connectivity

Connectivity and its Impact on Metabolic Function

Network connectivity refers to the intricate web of interactions between metabolites through biochemical reactions. A fundamental property of metabolic networks is the presence of hub metabolites—compounds like ATP, NADH, and coenzyme A that participate in a high number of reactions [15]. These hubs are crucial for transferring specific biochemical groups (e.g., phosphate, redox equivalents) and are essential for the network's overall functionality and robustness [15]. The bow-tie structure is a key global connectivity pattern, where metabolites are classified into a Giant Strongly Connected Component (GSC), input (IN), output (OUT), and isolated (IS) subsets [16]. The GSC, where all metabolites can be interconverted, acts as the network's core.

Connectivity in Gap-Filling and Prediction

Connectivity is not merely a structural feature but a critical constraint in making metabolic models biologically relevant. Traditional Graph-Based Analysis (GBA) often overestimates connectivity by including biologically impossible pathways [16]. In contrast, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) accounts for mass-balance and thermodynamic constraints, yielding a more accurate picture of functional connectivity [16]. This principle is leveraged by advanced gap-filling algorithms.

For instance, machine learning methods like CHESHIRE frame the prediction of missing reactions as a hyperlink prediction task on a hypergraph, where each reaction is a hyperlink connecting all its participant metabolites [17]. The algorithm uses topological features from the network to learn patterns and predict which missing reactions (from a universal database like MetaCyc or KEGG) would best restore connectivity and resolve gaps, all without requiring prior experimental phenotypic data [17].

Figure 2: A generalized workflow for gap-filling algorithms. The process involves identifying gaps in an incomplete model, proposing candidate reactions from a database, and selecting an optimal set to restore network connectivity and function.

Advanced Gap-Filling Algorithms and Experimental Integration

Evolution of Gap-Filling Methodologies

Gap-filling has evolved from simple connectivity checks to sophisticated algorithms that integrate multiple data types and constraints.

Table 2: Comparison of Gap-Filling Approaches

| Approach | Key Principle | Representative Tools | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization-Based | Uses Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) to find the minimal set of reactions from a database that restore network function (e.g., growth) [3] [2]. | GapFill [3], FASTGAPFILL [2] | Ensures functional consistency; finds parsimonious solutions. | Requires a defined objective (e.g., biomass); sensitive to reaction bounds. |

| Topology-Based (ML) | Uses machine learning on hypergraph representations of the network to predict missing reactions purely from topology [17]. | CHESHIRE [17], NHP [17] | Does not require experimental data; can reveal non-intuitive connections. | Relies on the quality and completeness of the training network. |

| Community-Based | Resolves gaps across multiple metabolic models simultaneously, allowing species to interact metabolically to achieve a community objective [3]. | Community Gap-Filling [3] | Ideal for modeling microbial consortia; predicts metabolic interactions. | Complex optimization; requires community context. |

Table 3: Essential Resources for Metabolic Model Gap-Filling

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Function in Gap-Filling | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal Biochemical Database | Reference Knowledgebase | Provides a pool of candidate reactions to add during gap-filling to restore connectivity [3] [2]. | MetaCyc [3], KEGG [17], BiGG [17] |

| Stoichiometric Matrix | Data Structure | The mathematical core of the model, representing all metabolite-reaction relationships. Used for gap detection and FBA [14]. | Model-specific (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli) [16] |

| Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Association | Logical Rules | Links genes to reactions, allowing genomic evidence to guide reaction addition and manual curation [14] [2]. | Model-specific |

| Phenotypic Data (Growth/Secretion) | Experimental Data | Used to validate gap-filling solutions and to constrain optimization-based algorithms [2]. | Laboratory assays (e.g., growth curves) |

| Linear & Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (LP/MILP) Solver | Computational Tool | The computational engine for solving the optimization problems at the heart of many gap-filling algorithms [3] [2]. | CPLEX, Gurobi, GLPK |

Dead-end metabolites and blocked reactions are fundamental concepts in the curation and application of genome-scale metabolic models. Their identification and resolution through gap-filling are critical for developing models that accurately reflect an organism's metabolic capabilities. The process relies heavily on understanding network connectivity, from the local topology around a single metabolite to the global, system-level bow-tie structure. As the field advances, gap-filling methodologies are becoming increasingly sophisticated, integrating machine learning and community modeling approaches to not only improve model quality but also to drive novel metabolic discoveries, such as identifying promiscuous enzyme activities and underground metabolic pathways [2]. A robust understanding of these core concepts provides the foundation for meaningful research in metabolic modeling and its applications in biotechnology, ecology, and medicine.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are mathematical representations of an organism's metabolism, derived from its genomic annotation. They serve as powerful tools for predicting metabolic phenotypes, guiding metabolic engineering, and understanding disease mechanisms. A persistent challenge in their construction is the presence of metabolic gaps—missing reactions that disrupt network connectivity—arising from incomplete genomes, misannotated genes, and undiscovered biochemistry. The gap-filling paradigm is the computational process of systematically identifying these network inconsistencies and proposing biologically plausible solutions to create functional metabolic networks. This guide details the core principles, algorithms, and methodologies that underpin this essential process, providing a framework for researchers to build more accurate and predictive metabolic models.

The process of building a GEM typically begins with an automated draft reconstruction based on genome annotation. This draft model is often incomplete and non-functional, incapable of simulating basic biological functions like biomass production because the metabolic network is disconnected. These disconnections are "gaps" that manifest as dead-end metabolites—metabolites that can only be produced or consumed, but not both—and blocked reactions—reactions that cannot carry any flux in steady-state conditions [2] [18]. Gaps exist for several reasons: many genes remain unannotated or are assigned incorrect functions; database coverage of known biochemical reactions is incomplete; and organisms may utilize non-canonical or underground metabolic pathways involving promiscuous enzyme activities [19] [2].

Consequently, gap-filling has become an indispensable step in the reconstruction of metabolic networks. The fundamental paradigm involves a cycle of (1) detecting gaps in the network, (2) proposing solutions by adding reactions from reference databases, and (3) assigning genes to the added reactions where possible [2]. The following sections deconstruct this paradigm, providing a technical examination of its components.

Core Gap-Filling Workflow and Algorithm Classification

The generalized gap-filling workflow is a multi-stage process that transforms an incomplete draft metabolic model into a functional network. The flowchart below illustrates the key stages and decision points.

Gap-filling algorithms can be classified based on their underlying methodology and the data they utilize. The table below summarizes the main classes of algorithms and their representative examples.

Table 1: Classification of Gap-Filling Algorithms

| Algorithm Class | Core Principle | Representative Tools | Key Inputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parsimony-Based | Finds the minimal set of reactions to enable network functionality [20]. | GapFill [2], fastGapFill [2], GenDev [20] | Stoichiometric model, Reaction database |

| Phenotype-Fitting | Maximizes consistency between model predictions and experimental growth/data [2]. | GrowMatch [2], OMNI [2] | Growth phenotypes, Flux data |

| Likelihood-Based | Incorporates genomic evidence (e.g., sequence homology) to score and select solutions [21]. | KBase workflow [21] | Gene sequences, Homology data |

| Hypothesis-Driven | Uses extensive databases of known and hypothetical reactions to explore novel biochemistry [19]. | NICEgame [19] | ATLAS of Biochemistry |

| Machine Learning | Learns reaction presence/absence patterns from large collections of existing models to predict missing reactions [10]. | DNNGIOR [10] | Pre-trained model on >11k bacterial species |

Quantitative Performance of Gap-Filling Methods

Evaluating the performance of gap-filling algorithms is crucial for selecting the appropriate tool. Performance is typically measured by the accuracy of the added reactions and the functional capacity of the resulting model.

A study comparing automated and manual gap-filling for a Bifidobacterium longum model provides concrete metrics. The automated algorithm (GenDev) proposed 12 reactions, but two were unnecessary, making the true solution set 10 reactions. Manual curation added 13 reactions. The overlap was 8 reactions, resulting in a recall of 61.5% and a precision of 66.6% [20]. This demonstrates that automated methods can propose significant numbers of correct reactions, but also include false positives, necessitating manual review.

Advanced methods show improved performance. The deep learning tool DNNGIOR achieves an average F1 score of 0.85 for reactions present in over 30% of its training genomes. Furthermore, it was shown to be 14 times more accurate for draft reconstructions and 2–9 times more accurate for curated models compared to unweighted gap-filling [10].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Gap-Filling Algorithms

| Algorithm / Study | Key Performance Metric | Result | Context / Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| GenDev [20] | Recall | 61.5% | B. longum model |

| GenDev [20] | Precision | 66.6% | B. longum model |

| DNNGIOR [10] | Average F1 Score | 0.85 | Reactions in >30% of training bacteria |

| NICEgame [19] | Average Solutions per Rescued Reaction | 252.5 (vs. 2.3 for KEGG) | E. coli iML1515 model gap-filling |

| NICEgame [19] | Gene Essentiality Prediction Accuracy | 23.6% increase | Extended E. coli model (iEcoMG1655) |

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The experimental and computational workflow for gap-filling relies on a suite of key resources. The following table details essential "research reagents" for the field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Gap-Filling

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Databases (MetaCyc [20], KEGG [19], ModelSEED [3]) | Reference sets of known biochemical reactions used as pools for potential gap-filling solutions. | Providing candidate reactions to add to a model to connect a dead-end metabolite. |

| ATLAS of Biochemistry [19] | A database of both known and hypothetical biochemical reactions generated from mechanistic enzyme rules. | Exploring novel gap-filling solutions beyond known biochemistry in the NICEgame workflow. |

| BridgIT [19] | A computational tool that identifies possible enzymes for a given biochemical reaction. | Annotating gap-filled reactions with candidate genes in the NICEgame workflow. |

| High-Throughput Phenotyping Data [2] | Experimental data on growth capabilities under different conditions or of gene knockout mutants. | Identifying model-data inconsistencies (false predictions) that reveal metabolic gaps. |

| Thermodynamic Constraints [22] | Data and algorithms used to enforce thermodynamic feasibility on reaction directions and flux loops. | Detecting and removing thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs) during model curation. |

| Context-Specific Data (Transcriptomics) [23] [22] | Omics data used to refine a general model to a specific condition or cell type. | Guiding the construction of context-specific models (CSMs) and identifying condition-specific gaps. |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol for Parsimony-Based Gap-Filling with Growth Requirement

This protocol is based on the core GapFill algorithm and its variants [2] [3].

Input Preparation:

- Incomplete Metabolic Model (S): A stoichiometric matrix of the draft model.

- Universal Reaction Database (U): A stoichiometric matrix of a comprehensive reaction database (e.g., MetaCyc, KEGG).

- Biomass Reaction: A reaction defining the biomass composition of the target organism.

- Nutrient Constraints: Definitions of available extracellular metabolites.

Gap Detection via Flux Balance Analysis (FBA):

- Set the biomass reaction as the objective function.

- Perform FBA. If the predicted growth is zero, a gap-filling problem is confirmed.

- Alternatively, check for the production of each biomass precursor metabolite individually.

Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) Formulation:

- The objective is to minimize the number of reactions added from U to S.

- Let

y_jbe a binary variable indicating whether reactionjfrom U is added to the model. - Objective Function: Minimize

Σ y_j. - Constraints:

- Steady-State Mass Balance:

S_int * v_int + U * v_u = 0, wherev_intare fluxes from the internal model andv_uare fluxes from the universal database. - Flux Constraints:

lower_bound_j <= v_j <= upper_bound_jfor all reactions. - Connection to Binary Variables:

v_u_j <= y_j * M, whereMis a large constant, ensuring that ify_j=0, thenv_u_j=0. - Growth Constraint: The flux through the biomass reaction must be greater than a small positive value (e.g., 0.1).

- Steady-State Mass Balance:

Solution and Model Update:

- Solve the MILP problem using a solver like SCIP or CPLEX.

- Add all reactions

jfor whichy_j = 1in the solution to the draft model S.

Protocol for Likelihood-Based Gene Annotation and Gap-Filling

This protocol leverages genomic information to guide solution selection, as implemented in KBase [21].

Generate Alternative Gene Annotations:

- For each gene in the genome, use sequence homology tools (e.g., BLAST) against multiple databases to identify all potential enzyme annotations above a threshold E-value.

Calculate Annotation Likelihoods:

- Assign a likelihood score to each annotation based on sequence similarity metrics (e.g., E-value, bit score).

- Normalize scores so that the sum of likelihoods for all possible annotations of a single gene equals 1.

Map Annotations to Reactions and Calculate Reaction Likelihoods:

- Map each enzyme annotation to one or more metabolic reactions via Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules.

- The likelihood of a reaction is derived from the likelihoods of the genes and GPR rules associated with it.

Likelihood-Based Gap-Filling MILP Formulation:

- The goal is to find a gap-filling solution that maximizes the total likelihood of the activated reactions, rather than simply minimizing their count.

- Let

y_jbe a binary variable for adding reactionjfrom U. - Let

L_jbe the precomputed likelihood for reactionj. - Objective Function: Maximize

Σ (y_j * log(L_j)). - Constraints: Same as the parsimony-based MILP constraints (steady-state, flux bounds, growth requirement).

Experimental Validation Protocol for Gap-Filled Models

After a model has been gap-filled, its predictions must be experimentally validated [20].

Gene Essentiality Validation:

- In Silico Prediction: For a set of genes in the gap-filled model, predict which gene knockouts would prevent growth (i.e., are essential) under a defined condition (e.g., glucose minimal media).

- In Vivo Experimentation: Perform systematic gene knockout studies in the target organism and assay for growth under the same defined condition.

- Comparison: Calculate the accuracy of the model's predictions by comparing in silico and in vivo essentiality results. A significant increase in accuracy after gap-filling, as seen with NICEgame [19], validates the approach.

Growth Phenotype Profiling (Biolog Assays):

- In Silico Prediction: Simulate growth of the gap-filled model on a wide array of single carbon sources.

- In Vivo Experimentation: Use high-throughput phenotyping platforms (e.g., Biolog plates) to measure actual growth of the organism on the same carbon sources.

- Comparison: Calculate the correlation or accuracy between predicted and measured growth capabilities. This assesses the model's functional predictive power beyond just biomass production [21].

Advanced Topics: Community and Thermodynamic Gap-Filling

Community-Level Gap-Filling

Traditional gap-filling is performed on single organisms, but a novel algorithm extends this concept to microbial communities [3]. This method simultaneously considers multiple incomplete metabolic models of species known to coexist. It allows the models to interact metabolically (e.g., through cross-feeding) during the gap-filling process. This can resolve gaps in one organism by adding a reaction in another organism that produces a required metabolite, leading to more accurate predictions of metabolic interactions and a more biologically realistic community model [3].

Thermodynamically Consistent Gap-Filling

A major challenge in GEMs is the presence of thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs), which are loops of reactions that can sustain flux without a net input of energy, violating the laws of thermodynamics [22]. Advanced tools like ThermOptCOBRA address this by integrating thermodynamic constraints directly into the model construction and analysis pipeline [22]. These tools can identify TICs, determine thermodynamically feasible reaction directions, and construct context-specific models that are free from thermodynamically blocked reactions, leading to more accurate flux predictions.

The construction of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represents a cornerstone of systems biology, enabling researchers to predict metabolic behaviors from genomic information. These computational models simulate the complex biochemical network of reactions within cells, providing insights into cellular functions, nutrient utilization, and byproduct formation. However, incomplete genome annotations and technical limitations in genome sequencing frequently result in metabolic models that contain gaps—missing reactions that disrupt metabolic pathways and compromise predictive accuracy [10] [20]. Gap-filling algorithms have thus emerged as essential computational techniques that propose the addition of biologically plausible reactions to incomplete metabolic networks, enabling the production of all essential biomass components from available nutrients [20].

The fundamental challenge addressed by gap-filling stems from the reality that metabolic networks derived from annotated genomes are often fragmented. Even in well-studied model organisms, approximately 10-20% of metabolic genes may be incorrectly annotated or missed entirely [20]. This problem is particularly acute for uncultured bacteria and organisms derived from metagenome-assembled genomes, where incomplete genomic data leads to substantial gaps in metabolic reconstructions [10]. Without computational intervention to address these deficiencies, metabolic models cannot accurately simulate growth or predict metabolic capabilities, severely limiting their utility in both basic research and applied biotechnology.

The Critical Need for Gap-Filling Algorithms

Metabolic gaps originate from multiple sources throughout the model reconstruction pipeline. Genome annotation errors represent a primary contributor, where genes may be assigned incorrect functions or missed entirely due to limitations in sequence analysis algorithms [3] [20]. This problem is compounded by incomplete biochemical databases that lack full representation of enzymatic diversity across the tree of life [3]. Furthermore, fragmented genome assemblies from metagenomic studies often yield partial gene sequences that resist functional characterization [10]. The cumulative effect of these limitations is the creation of metabolic networks with dead-end metabolites and interrupted pathways that cannot sustain life, thereby necessitating sophisticated gap-filling approaches to restore metabolic functionality.

The practical consequences of unfilled gaps in metabolic models are profound. Models with metabolic gaps fail to produce essential biomass precursors, such as amino acids, nucleotides, and cofactors, making accurate simulation of growth impossible [20]. This limitation cascades into flawed predictions of gene essentiality, nutrient utilization, and metabolic byproduct secretion [22]. In biomedical contexts, such inaccuracies can undermine drug target identification and disease mechanism elucidation. For microbial communities, the inability to accurately model individual members' metabolisms prevents realistic simulation of interspecies interactions that govern community dynamics and function [3]. These implications highlight why gap-filling is not merely a technical refinement but an essential step in creating biologically meaningful metabolic models.

Quantitative Assessment of the Gap-Filling Challenge

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Gap-Filling Algorithms

| Algorithm | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | Key Strengths | Common Errors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GenDev | 61.5 | 66.6 | Minimum-cost solutions; parsimonious | Non-minimal solutions; numerical imprecision |

| Manual Curation | 100 | 100 | Biological expertise incorporation | Time-intensive (months of effort) |

| DNNGIOR | ~85 (F1 score for frequent reactions) | High (fewer false positives) | Phylogenetically-informed; deep learning | Performance decreases for rare reactions |

| Community Gap-Filling | Context-dependent | Context-dependent | Captures metabolic interactions | Complex implementation |

The challenge of accurate gap-filling is quantified by performance comparisons between automated algorithms and manual curation. In one comprehensive evaluation, the GenDev gap-filling algorithm achieved a recall of 61.5% and precision of 66.6% when compared to a manually curated model of Bifidobacterium longum [20]. This comparison revealed that although computational methods successfully identify most essential reactions, approximately one-third of their predictions may be incorrect. These errors stem from various factors, including numerical imprecision in optimization solvers, random selection among functionally equivalent reactions, and inability to incorporate domain-specific biological knowledge [20].

More recently, machine learning approaches have demonstrated enhanced performance for specific gap-filling challenges. The DNNGIOR (Deep Neural Network Guided Imputation of Reactomes) method, trained on over 11,000 bacterial species, achieves an average F1 score of 0.85 for reactions present in at least 30% of training genomes [10]. This performance, however, is strongly influenced by reaction frequency across bacteria and the phylogenetic distance of the target organism to those in the training data [10]. These quantitative assessments underscore both the substantial progress in gap-filling methodology and the continuing need for refinement to approach the accuracy of manual curation.

Methodological Approaches to Gap-Filling

Classical Optimization-Based Algorithms

Traditional gap-filling algorithms employ constraint-based optimization techniques to identify minimal sets of reactions that must be added to a metabolic network to enable specific biological functions, typically biomass production. The foundational GapFill algorithm formulated this challenge as a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem that identified dead-end metabolites and proposed additions from biochemical databases such as MetaCyc [3]. These methods operate on the principle of parsimony, seeking the smallest number of database reactions that resolve all gaps while maintaining network connectivity [20]. The optimization objective typically minimizes the total number of added reactions or a weighted cost function reflecting the likelihood that particular reactions exist in the target organism.

More advanced implementations like gapseq and AMMEDEUS have improved computational efficiency by reformulating the gap-filling problem as a Linear Programming (LP) problem, substantially reducing solution times [3]. These algorithms incorporate taxonomic information and genomic evidence to weight reaction probabilities, favoring the addition of reactions that are phylogenetically widespread or supported by sequence similarity [3]. Despite these refinements, classical approaches remain limited by their dependence on the quality and completeness of reference databases, and their inability to incorporate broader biological context into reaction selection decisions.

Community-Aware Gap-Filling

A significant advancement in gap-filling methodology addresses the unique challenges of microbial community modeling. Traditional single-organism gap-filling may produce metabolically viable models that fail to capture the interactive nature of real microbial ecosystems. Community gap-filling algorithms simultaneously resolve gaps across multiple metabolic models while allowing for metabolic interactions between community members [3]. This approach recognizes that gaps in individual models may reflect specialized metabolic roles within communities rather than reconstruction errors, and that understanding these interactions is essential for accurate modeling of complex microbiomes.

The community gap-filling workflow involves constructing compartmentalized metabolic models that represent different organisms within a community, then applying optimization techniques to identify reaction additions that enable growth of all members through metabolic cross-feeding [3]. This method has proven particularly valuable for studying gut microbiota, where species like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Bifidobacterium adolescentis engage in both competitive and cooperative interactions [3]. By resolving gaps at the community level rather than in isolation, these algorithms can predict non-intuitive metabolic interdependencies that would be missed by single-organism approaches, providing more accurate models of naturally occurring microbial consortia.

Diagram 1: Community gap-filling workflow for predicting metabolic interactions. This approach simultaneously resolves gaps across multiple organisms while accounting for cross-feeding and other interactions.

AI-Enhanced Gap-Filling with DNNGIOR

The emerging frontier in gap-filling methodology leverages deep learning to predict missing reactions based on patterns learned from thousands of complete metabolic reconstructions. DNNGIOR represents this approach, employing a deep neural network trained on the presence and absence patterns of metabolic reactions across diverse bacterial taxa [10]. This method moves beyond the parsimony principle of classical approaches by learning complex, non-linear relationships between reaction sets and phylogenetic context, enabling more biologically informed gap-filling decisions.

A key innovation of DNNGIOR is its ability to incorporate phylogenetic relationships directly into reaction prediction. The performance of the algorithm is strongly influenced by the query organism's similarity to those in the training data, with more accurate predictions for organisms phylogenetically proximate to well-characterized taxa [10]. Additionally, DNNGIOR demonstrates superior performance for frequently occurring reactions (those present in >30% of training genomes) while maintaining reasonable accuracy for less common metabolic functions [10]. This AI-enhanced approach has been shown to produce models with fewer false positives compared to established tools like CarveMe, particularly for draft reconstructions where it demonstrated 14-fold greater accuracy [10].

Experimental Protocols for Gap-Filling Validation

Standardized Gap-Filling Workflow

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Metabolic Gap-Filling

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Databases | MetaCyc, KEGG, ModelSEED, BiGG | Source of candidate reactions | Curated biochemical transformations |

| Reconstruction Tools | Pathway Tools, CarveMe, gapseq | Model construction and gap-filling | Automated pipeline implementation |

| Optimization Solvers | SCIP, CPLEX, Gurobi | Mathematical optimization | MILP/LP problem solving |

| Model Analysis Platforms | COBRA Toolbox, COMETS | Constraint-based analysis | Flux prediction and simulation |

A robust experimental protocol for gap-filling begins with quality assessment of the draft metabolic reconstruction. The initial step involves using flux balance analysis to determine which biomass metabolites cannot be produced from the available nutrients [20]. This identifies the specific gaps requiring resolution. The researcher then selects an appropriate reference database (e.g., MetaCyc, KEGG) from which candidate reactions will be drawn, with consideration for database coverage of the target organism's phylogenetic group [3] [20]. The core gap-filling optimization is performed using tools such as GenDev, gapseq, or DNNGIOR, with algorithm selection depending on available genomic context and performance requirements [10] [3] [20].

Following the initial gap-filling process, essential validation steps must be performed. First, the necessity of each added reaction should be verified through iterative removal and growth simulation [20]. Second, the metabolic network should be analyzed for thermodynamic feasibility using tools like ThermOptCOBRA, which identifies thermodynamically infeasible cycles that violate the second law of thermodynamics [22]. Finally, the model's predictions should be compared to experimental data when available, such as growth capabilities on different substrates or known auxotrophies [20]. This comprehensive protocol ensures that gap-filled models are both computationally sound and biologically plausible.

Community Gap-Filling Implementation

For microbial community models, the gap-filling protocol requires modifications to account for multi-species interactions. The process begins with constructing individual metabolic models for each community member, which are then integrated into a compartmentalized community model with mechanisms for metabolite exchange [3]. Gap-filling is performed simultaneously across all members, with the optimization objective being community growth rather than individual fitness. The algorithm identifies reaction additions that enable cross-feeding relationships, where one species' metabolic byproducts serve as nutrients for others [3].

Validation of community gap-filling presents unique challenges. Researchers should verify that predicted metabolic interactions align with known ecological relationships, such as the production of short-chain fatty acids in gut microbiota [3]. For synthetic communities, experimental validation can include co-culture growth assays and metabolite measurements to confirm predicted exchange processes [3]. Computational checks should include analysis of the community model for thermodynamic consistency and the absence of impossible energy-generating cycles that can arise from incorrect gap-filling assumptions [22].

Diagram 2: Standardized workflow for metabolic model gap-filling, from initial gap identification through final validation.

Applications in Predictive Biology and Biomedicine

Drug Target Identification and Biomarker Discovery

Gap-filled metabolic models have demonstrated significant utility in biomedical research, particularly for drug target identification in pathogens and cancer cells. Context-specific models of pathogenic organisms can predict essential metabolic functions required for growth in host environments, highlighting potential targets for antimicrobial development [24]. Similarly, models of cancer metabolism reconstructed from transcriptomic data can identify metabolic vulnerabilities distinct from normal cells, suggesting targets for selective therapeutic intervention [24]. The accuracy of these predictions is wholly dependent on complete metabolic networks, making gap-filling an essential prerequisite for reliable target identification.

Beyond drug discovery, metabolic models contribute to biomarker discovery by predicting metabolic alterations associated with disease states. Gap-filled models can simulate the metabolic consequences of genetic mutations or environmental perturbations, forecasting changes in metabolite levels that may serve as diagnostic or prognostic indicators [24]. For complex diseases involving host-microbe interactions, such as inflammatory bowel disease, integrated models of human and microbial metabolism can reveal jointly produced metabolites that reflect disease activity [24]. These applications demonstrate how gap-filling transforms metabolic models from academic exercises to practical tools for addressing clinically relevant challenges.

Microbiome Research and Personalized Medicine

The human microbiome represents a particularly promising application for advanced gap-filling methodologies. Models of gut microorganisms like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Bifidobacterium adolescentis, gap-filled using community-aware approaches, have elucidated the metabolic basis for their cooperative interactions, including butyrate production that supports colonic health [3]. These models provide mechanistic insights into how microbiome composition influences host health, suggesting strategies for probiotic interventions and dietary modifications to manage microbiome-associated diseases.

Looking toward personalized medicine, gap-filling enables the construction of patient-specific metabolic models based on individual microbiome profiles or tissue metabolomics. By incorporating omics data into gap-filled reconstructions, researchers can simulate how individual genetic variation or microbiome composition influences metabolic phenotype [24]. This approach lays the foundation for predicting individual responses to drugs or dietary interventions, potentially guiding personalized treatment strategies for metabolic disorders, cancer, and other complex diseases [24].

Current Limitations and Future Directions

Despite substantial methodological progress, significant challenges remain in metabolic gap-filling. Thermodynamic feasibility represents a persistent concern, as algorithms may introduce reactions that create thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs) violating the second law of thermodynamics [22]. Recent tools like ThermOptCOBRA address this limitation by incorporating thermodynamic constraints during model construction and gap-filling, but these approaches increase computational complexity [22]. Additional limitations include database bias toward well-characterized model organisms, inaccurate directionality assignments for reactions, and inability to predict truly novel metabolic functions not present in reference databases [20] [22].