Generational Shift: A Sustainability Comparison of First, Second, and Third-Generation Biofuels

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sustainability profiles of first, second, and third-generation biofuels, tailored for researchers and scientists in the bioenergy sector.

Generational Shift: A Sustainability Comparison of First, Second, and Third-Generation Biofuels

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sustainability profiles of first, second, and third-generation biofuels, tailored for researchers and scientists in the bioenergy sector. It explores the foundational definitions and feedstocks of each biofuel generation, delves into the methodological advances in biochemical and thermochemical conversion processes, and addresses key troubleshooting challenges in scaling production. Through a rigorous validation and comparative framework, it evaluates environmental impacts, economic viability, and carbon footprints, offering a critical perspective on the future of sustainable biofuel integration into the energy landscape.

Defining the Generations: Feedstocks, Origins, and Core Concepts

First-generation (1G) biofuels, derived primarily from food crops like corn, sugarcane, and vegetable oils, represent the initial large-scale attempt to transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources for transportation. While they offered a promising alternative and paved the way for advanced biofuels, their sustainability credentials have been intensely debated. This review objectively examines the origins, performance, and environmental footprint of 1G biofuels, contextualizing them within the broader research on biofuel generations. We synthesize quantitative data on their greenhouse gas emissions, land and water footprints, and explore the seminal "food vs. fuel" dilemma. The analysis is supported by detailed methodologies of life cycle assessment (LCA) and a curated toolkit of research reagents, providing a foundational resource for scientists and policymakers engaged in sustainable energy research.

The story of first-generation biofuels is one of initial promise followed by intense controversy. Emerging as a direct response to energy security concerns, rising fossil fuel prices, and early climate change mitigation policies, 1G biofuels were the first to achieve significant commercial production [1] [2]. They are classified as conventional biofuels produced through well-established processes such as fermentation of sugars and starches for bioethanol (from crops like corn and sugarcane) and transesterification of vegetable oils for biodiesel (from oils such as soybean, rapeseed, and palm) [3] [4] [2]. The initial "cornucopian views" of their potential were soon challenged by increasing speculation that their development was "racing ahead of understanding of the range of direct and indirect sustainability impacts" [1]. This review deconstructs these impacts, setting the stage for a comparative understanding of subsequent, more advanced biofuel generations.

Feedstock Origins and Production Pathways

First-generation biofuels are defined by their reliance on food-crop biomass. The production pathways are technologically straightforward, which facilitated their rapid adoption.

- Bioethanol Production: The primary feedstocks are sugarcane (notably in Brazil) and corn (in the United States), followed by wheat, sugar beet, and sorghum [4] [5]. The process involves crushing the plant material to extract sucrose (sugarcane) or hydrolyzing starch into fermentable sugars (corn), followed by microbial fermentation, typically using the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, to produce ethanol [4].

- Biodiesel Production: Common feedstocks include rapeseed, soybean, and palm oil [5]. The production occurs via transesterification, a chemical reaction where triglycerides in the oils react with an alcohol (like methanol) in the presence of a catalyst (such as sodium hydroxide) to produce fatty acid methyl esters (biodiesel) and glycerol [6] [4].

The following diagram illustrates the core production pathways and the central sustainability challenge of first-generation biofuels.

Quantitative Sustainability Performance and Comparative Data

A critical appraisal of 1G biofuels reveals a complex and often mixed environmental record. The following tables synthesize key quantitative data from life cycle assessment (LCA) studies, comparing their performance with fossil fuels and highlighting variations between major feedstocks.

Table 1: Global Resource Footprint of First-Generation Biofuels (2013 Data) [5]

| Biofuel Type | Global Production (Million Tons) | Estimated Arable Land Use (Million Hectares) | Global Water Footprint (Billion m³) | Food Equivalent: Number of People That Could Be Fed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioethanol | 65 | ~27.5 | ~144 | ~200 Million |

| Biodiesel | 21 | ~13.8 | ~72 | ~70 Million |

| Total | 86 | ~41.3 | ~216 | ~270 Million |

Note: The data highlights that 1G biofuels relied on about 2-3% of global agricultural water and 4% of arable land, resources that could otherwise feed a significant portion of the malnourished population.

Table 2: Environmental Impact Comparison of Select Biofuel Feedstocks [5] [2]

| Feedstock | Biofuel Type | Land Footprint (m²/GJ) | Water Footprint (m³/GJ) | GHG Reduction vs. Fossil Fuels (No LUC) | Key Environmental Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugarcane | Bioethanol | ~40 - 60 | ~60 - 90 | ~70-90% | Water use, air pollution from burning |

| Corn | Bioethanol | ~80 - 120 | ~150 - 250 | ~20-50% | High fertilizer use, eutrophication |

| Palm Oil | Biodiesel | ~30 - 50 | ~210 - 350 | >60% (if no peatland use) | Deforestation, biodiversity loss |

| Rapeseed | Biodiesel | ~130 - 180 | ~150 - 300 | ~45-65% | High land-use, fertilizer demand |

| Soybean | Biodiesel | ~200 - 250 | ~1300 - 2200 | ~50-70% | Very high land and water use |

Abbreviation: LUC, Land-Use Change. GHG reduction ranges are highly dependent on cultivation practices and LCA methodologies. Palm oil has high GHG emissions if associated with deforestation or peatland drainage.

Experimental Protocols: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

The quantitative data presented above is primarily derived from Life Cycle Assessment, a standardized methodology crucial for evaluating the environmental footprint of biofuels.

1. Goal and Scope Definition

- Objective: To evaluate the environmental impacts of a biofuel from "cradle-to-grave"—from feedstock cultivation to end-use combustion.

- Functional Unit: The study is normalized to a unit of energy or distance traveled (e.g., 1 Megajoule (MJ) of fuel or 1 vehicle-kilometer) to enable fair comparisons with fossil fuels and other biofuel generations [2].

2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

- Data Collection: This phase involves compiling quantitative input and output data for all processes in the life cycle. For 1G biofuels, this includes:

- Agricultural Phase: Inputs of fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation water, and diesel for farm machinery; outputs like nutrient runoff and CO₂ from soil.

- Feedstock Transport: Energy for transporting raw biomass to processing plants.

- Conversion Phase: Energy and chemicals (e.g., enzymes, catalysts) used in fermentation or transesterification.

- Fuel Distribution & Combustion: Energy for transport and infrastructure, and emissions from burning the fuel [2].

3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

- Impact Categories: The LCI data is translated into potential environmental impacts. Key categories for biofuels are:

- Global Warming Potential (GWP): Calculated in kg CO₂-equivalent, considering CO₂, N₂O, and CH₄ emissions.

- Water Footprint: Total volume of fresh water consumed.

- Land Use: Area and type of land required, often linked to biodiversity impact.

- Eutrophication and Acidification: From nutrient leaching and air emissions [2].

4. Interpretation

- Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis: Given the variability in agricultural practices and data, LCA outcomes are situational. A critical analysis includes addressing direct and indirect land-use change (LUC/iLUC). iLUC occurs when pasture or forest is cleared to create new cropland to replace the food crops diverted to biofuels, leading to potentially large, indirect GHG emissions [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Research into optimizing 1G biofuel production and accurately assessing its impacts relies on a suite of specialized reagents and analytical techniques.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Biofuel Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Biofuel Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Model yeast for ethanol fermentation. | Standard bioethanol production from sucrose and glucose [4]. |

| Lipase Enzymes | Biological catalysts for transesterification. | Enzymatic biodiesel production as an alternative to chemical catalysis [2]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Analytical method for separation and identification of volatile compounds. | Quantifying biofuel purity, analyzing biodiesel (FAME) composition, and detecting contaminants [2]. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Analytical method for separating ions or molecules in a solution. | Measuring sugar content in hydrolysates, organic acids, and glycerol by-products [2]. |

| Stable Isotope Tracing (e.g., ¹³C) | Tracking the fate of specific atoms in biological/chemical processes. | Elucidating metabolic pathways in fermenting microorganisms to improve yield [2]. |

| LCA Software (e.g., SimaPro, GaBi) | Modeling and database tools for conducting life cycle assessments. | Quantifying environmental impacts (GHG, water, land use) across the full biofuel supply chain [2]. |

The Food-Energy-Water Nexus and Broader Implications

The core sustainability challenge of 1G biofuels is their entanglement in the food-energy-water nexus. The diversion of food crops for fuel production creates a direct competition for arable land, water, and agricultural inputs [1] [5]. It is estimated that the crops used for biofuels in 2013 could have fed about 270 million people, underscoring the significant "food vs. fuel" trade-off [5]. Furthermore, the expansion of biofuel plantations has been linked to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and associated increases in GHG emissions, particularly in regions like Southeast Asia due to palm oil cultivation [6] [5]. The following diagram maps the interconnected challenges within this nexus.

First-generation biofuels served as a critical proof-of-concept for renewable liquid transportation fuels but are now widely recognized as a transitional technology due to their inherent sustainability limitations. The controversies surrounding them—primarily the food vs. fuel conflict, substantial land and water footprints, and risks of deforestation—have fundamentally shaped the research agenda for advanced biofuels [1]. These challenges catalyzed the development of second-generation biofuels from non-food lignocellulosic biomass, third-generation biofuels from algae, and fourth-generation biofuels involving synthetic biology [3] [4] [7]. A key lesson from 1G biofuels is that sustainability challenges are complexly interconnected and cannot be solved by focusing on a single metric like GHG reduction alone [1]. Future research and policy must therefore adopt integrated, whole-system approaches that carefully balance energy production with food security, water conservation, and the protection of ecosystems.

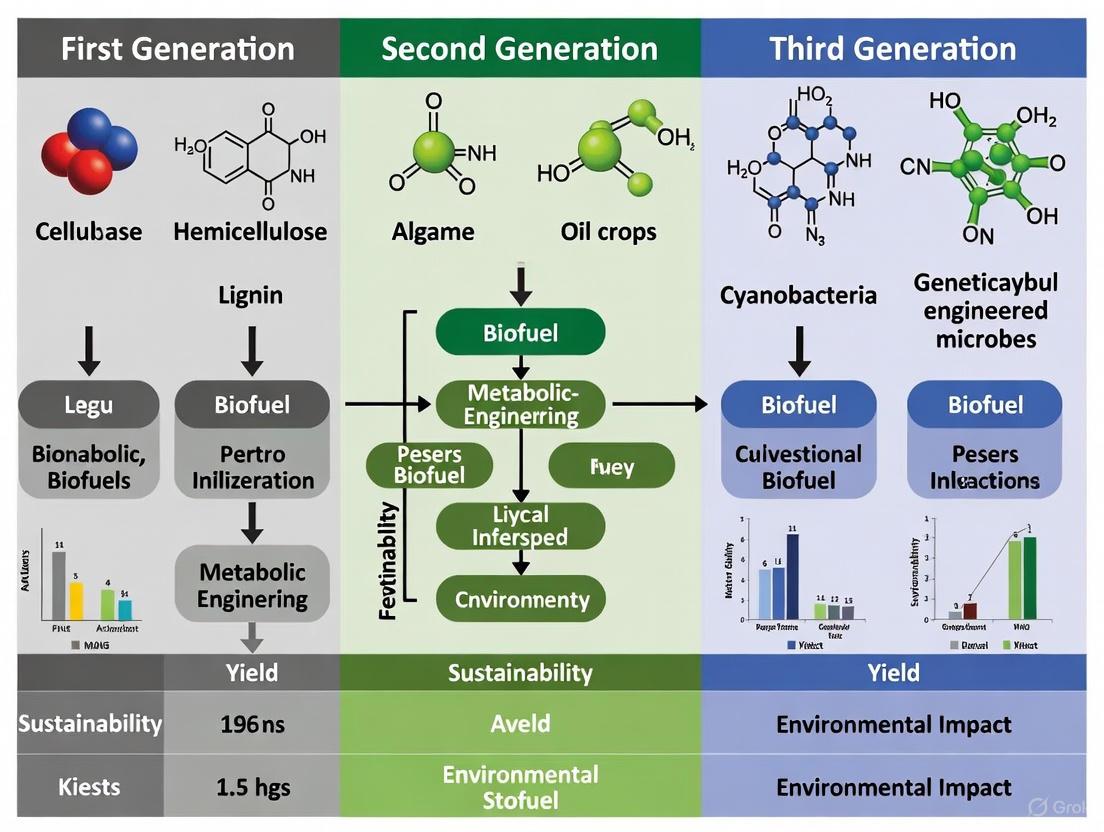

The global quest for sustainable and renewable energy sources has catalyzed the development of biofuels, which are categorized into distinct generations based on their feedstocks and production technologies. First-generation biofuels are derived directly from food crops such as corn, wheat, and sugarcane, raising significant concerns regarding the "food versus fuel" debate, land use changes, and limited greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction benefits [4] [8]. In response to these challenges, second-generation biofuels emerged, utilizing non-food biomass, primarily lignocellulosic materials from agricultural residues, forestry waste, and dedicated energy crops [9] [10]. This advancement avoids competition with food supply and offers a more sustainable pathway. Subsequently, third-generation biofuels, primarily derived from algae, entered the research landscape, promising high yields on non-arable land but facing hurdles related to cost and technological maturity [4] [10]. This guide focuses on objectively comparing the performance of second-generation biofuel technologies against first- and third-generation alternatives, with a particular emphasis on the experimental methodologies and data underpinning the advancements in lignocellulosic biomass utilization.

Comparative Analysis of Biofuel Generations

The following table provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of the key characteristics of first-, second-, and third-generation biofuels.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Biofuel Generations

| Feature | First-Generation Biofuels | Second-Generation Biofuels | Third-Generation Biofuels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedstock | Food crops (e.g., corn, sugarcane, soybean oil) [4] | Non-food lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., wheat straw, rice husk, corn stover, wood chips) [9] [10] | Microalgae and cyanobacteria [4] |

| Primary Conversion Process | Fermentation of sugars (Ethanol), Transesterification (Biodiesel) [4] | Pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis, & fermentation; Pyrolysis; Gasification [9] [11] | Lipid extraction & transesterification, fermentation of algal sugars [4] |

| Land-Use Impact | High (Competes for arable land) [4] | Low (Utilizes marginal land or waste products) [9] | Very Low (Can use non-arable land & wastewater) [4] [10] |

| GHG Reduction Potential | Moderate (~20-60% vs. fossil fuels) | High (Up to 86% vs. fossil fuels) [9] | Potentially Carbon-Negative [4] |

| Technology Maturity | Commercially established [12] | Demonstration & early commercial stage [13] | Predominantly R&D and pilot phase [10] |

| Key Challenge | Food vs. fuel debate, deforestation [4] | Recalcitrance of biomass, high pretreatment cost [9] [11] | High capital and operational costs, energy-intensive harvesting [4] [10] |

| Oil Yield (L/ha/year) | ~172 (Rapeseed), ~636 (Palm Oil) [4] | Not Applicable (Solid feedstock) | Up to 61,000 (Theoretical for algae) [4] |

Quantitative Performance of Second-Generation Feedstocks

The viability of second-generation biofuels hinges on the composition and conversion efficiency of various lignocellulosic feedstocks. The table below summarizes key quantitative data for prominent agricultural residues.

Table 2: Feedstock Composition and Biofuel Yield Data for Common Agricultural Residues

| Feedstock | Global Annual Waste (Million Tons) | Cellulose Content (%) | Hemicellulose Content (%) | Lignin Content (%) | Bioethanol Yield (L/dry ton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat Straw | ~350 [9] | 35-50 [9] | 20-35 [9] | 10-25 [9] | ~100 billion L annually from total waste [9] |

| Sugarcane Bagasse | ~279-300 [9] | 45-52 [9] | 20-35 [9] | 10-25 [9] | Data not specified |

| Corn Stover | ~170 [9] | 35-50 [9] | 20-35 [9] | 10-25 [9] | 223 - 358 [9] |

| Rice Husk | ~101.8 [9] | ~35 [14] | ~25 [14] | ~15 [14] | Energy yield: ~16.72 MJ/kg [9] |

Core Experimental Protocols in Lignocellulosic Biofuel Production

The conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into biofuels is a multi-step process. The following workflow diagram outlines the core experimental pathway, with subsequent sections detailing key protocols.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Lignocellulosic Biofuel Production

Pretreatment Methodologies

Pretreatment is a critical first step to overcome the recalcitrance of lignocellulose by disrupting its complex structure, making cellulose more accessible for enzymatic attack [11] [15]. The table below compares the most prominent pretreatment methods.

Table 3: Comparison of Key Pretreatment Methodologies for Lignocellulosic Biomass

| Method | Process Description | Key Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages/Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermal / Steam Explosion | Biomass is treated with high-pressure saturated steam (160-260°C) for several minutes, then rapidly depressurized [9] [11]. | Hydrolysis of hemicellulose, lignin transformation [9]. | Low environmental impact (only water), no recycling needed, industrially viable [9] [13]. | Formation of furfural and HMF (inhibitors) [11]. |

| Dilute Acid Hydrolysis | Biomass is treated with dilute sulfuric acid (0.5-1.5%) at high temperature (140-200°C) [11]. | Solubilizes hemicellulose into xylose and other sugars. | High xylose yield, effective for wide range of biomass. | Equipment corrosion, formation of fermentation inhibitors (furfural), requires neutralization [11]. |

| Ammonia Fiber Explosion (AFEX) | Biomass is treated with liquid ammonia at moderate temperatures (60-120°C) and high pressure for 10-60 mins, followed by rapid pressure release [9]. | Decrystallizes cellulose, cleaves lignin-hemicellulose bonds, increases porosity. | Low inhibitor formation, high sugar yields, ammonia can be recycled. | Less effective on high-lignin biomass (e.g., wood), cost of ammonia [9]. |

| Ionic Liquid (IL) Pretreatment | Biomass is dissolved in room-temperature molten salts (e.g., 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate) at 90-130°C [11]. | Dissolves cellulose and lignin, disrupts hydrogen bonding network. | High efficiency, tunable properties, can be recycled. | High cost, potential toxicity, need for complete recycling [11] [13]. |

| Biological Pretreatment | Uses lignin-degrading microorganisms (e.g., white-rot fungi like Trametes versicolor) to treat biomass for days to weeks [15]. | Enzymatic degradation of lignin by lignin peroxidases and laccases. | Low energy input, mild conditions, environmentally friendly. | Very slow process, large space requirement, loss of carbohydrates [15]. |

Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Fermentation

Following pretreatment, the biomass undergoes enzymatic hydrolysis. This process uses a cocktail of cellulase enzymes (e.g., endoglucanases, exoglucanases, β-glucosidases) to break down cellulose into fermentable glucose [11]. Key experimental parameters include:

- Enzyme Loading: Typically 5-20 mg enzyme protein per gram of dry biomass [11].

- Conditions: Carried out in buffered solutions (pH 4.5-5.0) at 45-50°C for 24-72 hours with constant agitation to maximize sugar yield, which can reach up to 90% of theoretical yield with optimized pretreatments [9].

The resulting hydrolysate, containing a mix of hexose (C6) and pentose (C5) sugars, is then fermented. Advanced fermentation strategies involve engineered microorganisms, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Zymomonas mobilis, genetically modified to co-ferment both C5 and C6 sugars, thereby maximizing biofuel yields from the complex substrate [9] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in second-generation biofuels relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details these essential components.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lignocellulosic Biofuel Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Feedstocks | Raw material for biofuel production; composition affects process design. | Wheat straw, rice husk, corn stover, sugarcane bagasse, switchgrass [9] [14]. Should be milled to a particle size of 1-2 mm. |

| Cellulolytic Enzyme Cocktails | Hydrolyzes cellulose into fermentable glucose. | Commercial blends from Trichoderma reesei (e.g., Cellic CTec2, CTec3). Contains endoglucanases, exoglucanases, and β-glucosidases [11]. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Highly efficient solvent for biomass pretreatment. | 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([C2C1Im][OAc]); requires recovery and purification for economic viability [11] [13]. |

| Genetically Engineered Microbes | Co-fermentation of C5 and C6 sugars to improve yield. | Engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae or E. coli capable of metabolizing xylose and arabinose [9] [11]. |

| Analytical Standards | Quantification of sugars and inhibitors via HPLC/GC. | Standards for glucose, xylose, arabinose, furfural, Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), and acetic acid [11]. |

| Anaerobic Digestion Inoculum | Source of microbes for biogas production studies. | Granular sludge from operational anaerobic digesters; requires acclimatization to the substrate [15]. |

Second-generation biofuels, derived from non-food lignocellulosic biomass, represent a critical advancement in the pursuit of sustainable energy. They offer a compelling alternative to first-generation biofuels by avoiding the food-versus-fuel dilemma and provide a more immediate and technologically mature pathway compared to third-generation algal biofuels. While challenges in pretreatment efficiency and overall process economics remain, continued research and development—particularly in robust enzyme cocktails, engineered microbial strains, and integrated biorefinery concepts—are steadily enhancing the commercial viability of this renewable energy source. The experimental data and protocols outlined in this guide provide a foundation for researchers to contribute to this vital field.

The quest for sustainable energy solutions has catalyzed the evolution of biofuels across distinct generations, each representing significant advancements in feedstock selection and production technologies. First-generation biofuels, derived from food crops like corn, sugarcane, and vegetable oils, emerged as initial alternatives to fossil fuels but sparked the "food versus fuel" debate due to competition for agricultural land and resources [3] [16]. Their production raised concerns about food security, land use changes, and limited greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction potential [17]. Second-generation biofuels addressed these concerns by utilizing non-food biomass, including agricultural residues (e.g., wheat straw, rice husks), forestry waste, and dedicated energy crops like switchgrass [3] [10]. While this approach mitigated the food competition conflict and offered better GHG reduction potential, it faced challenges related to complex conversion technologies, costly preprocessing of recalcitrant lignocellulosic biomass, and scalability issues [3] [16].

Third-generation biofuels, primarily derived from algal biomass (both microalgae and macroalgae), represent a transformative approach to biofuel production [18]. These biofuels leverage the superior efficiency of photosynthetic microorganisms that can be cultivated on non-arable land or in marine environments, thus eliminating competition with food production [19]. Microalgae, in particular, have emerged as exceptional candidates due to their rapid growth rates, high lipid content, and ability to thrive in diverse environmental conditions while consuming industrial CO₂ emissions and wastewater nutrients [20] [21]. This review comprehensively examines third-generation biofuels within the broader context of biofuel generational sustainability, focusing specifically on algal and aquatic feedstocks through detailed comparative analysis of experimental data, cultivation methodologies, conversion pathways, and sustainability metrics.

Comparative Analysis of Biofuel Generations

The progression from first- to third-generation biofuels reflects a concerted effort to improve sustainability metrics, including GHG emissions, land use efficiency, and resource consumption. Table 1 provides a detailed comparison of key characteristics across biofuel generations.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Biofuel Generations

| Characteristic | First-Generation | Second-Generation | Third-Generation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Examples | Corn, sugarcane, soybean, palm oil [16] | Agricultural residues (wheat straw), forestry waste, energy crops (switchgrass) [3] [10] | Microalgae (Chlorella, Nannochloropsis), macroalgae (seaweed) [20] [19] |

| Land Use Impact | High; requires arable land, leading to potential deforestation [16] | Moderate; utilizes marginal land or waste, but some deforestation concerns remain [3] | Very low; can be cultivated on non-arable land, ponds, or photobioreactors [19] [21] |

| Food Competition | Direct competition, raises food security concerns [3] [17] | Minimal to no competition [10] | No competition [19] |

| GHG Reduction Potential | Limited (13-65% compared to fossil fuels) [17] | Higher than first-generation [16] | Very high; some pathways show net-negative emissions [21] [22] |

| Technical Maturity | Commercially mature [16] | Demonstration and early commercial stage [23] | Pilot-scale and R&D phase [20] [23] |

| Key Challenges | Food vs. fuel, high fertilizer/pesticide use, limited GHG savings [16] [17] | Complex and costly conversion processes, feedstock logistics [3] [16] | High cultivation and processing costs, energy-intensive harvesting [20] [3] |

Life-cycle assessment (LCA) studies provide quantitative environmental impact comparisons across generations. A recent study evaluating biorefinery pathways found that third-generation algal routes exhibited significantly lower emissions compared to second-generation pathways [22]. Specifically, algae hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) demonstrated negative net emissions, while combined algae processing (CAP) also showed very low emissions, in contrast to palm fatty acid distillation (PFAD), a second-generation pathway, which had the highest emissions [22]. This emissions advantage stems from algae's efficient carbon capture during growth, potentially fixing 1.5–1.8 kg of CO₂ per kilogram of dry biomass produced [20].

Third-Generation Feedstock Profiles and Experimental Yields

Microalgae Species and Performance

Microalgae represent the most extensively researched third-generation feedstock, with specific species demonstrating exceptional biofuel potential due to their specialized metabolic characteristics. Table 2 summarizes the biofuel-relevant properties and experimentally measured yields of prominent microalgae species.

Table 2: Microalgae Species and Experimentally Measured Biofuel Potential

| Microalgae Species | Lipid Content (% Dry Weight) | Biomass Productivity | Biofuel Products | Experimental Conditions & Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorella emersonii | 58–63% [20] | Not specified | Biodiesel | Cultivated under low nitrogen conditions [20] |

| Chlorella protothecoides | 55% [20] | Not specified | Biodiesel | Grown under heterotrophic conditions with corn powder hydrolysate under nitrogen limitation [20] |

| Nannochloropsis sp. | Up to 73.3% [20] | Higher with shorter light paths (e.g., ~10 cm) [20] | Biodiesel, Bio-oil | Glycerol concentrations >25–35 g/L slowed growth; at 35 g/L glycerol, lipid content reached 73.3% [20] |

| Botryococcus braunii | 12.71% (w/w) [20] | 2.31 g/L/day [20] | Biodiesel, Hydrocarbons, Biocrude | Highest biomass production at 20% CO₂ concentration with 2% sodium hypochlorite added to photobioreactors [20] |

| Schizochytrium strains | Not specified | 7.3–9.4 g/L/day [20] | Biodiesel, Omega-3 Fatty Acids | Certain strains achieve biomass densities up to 200 g/L within 90–100 hour fermentation cycles with nitrogen and glucose [20] |

The data in Table 2 illustrates how cultivation strategies significantly influence biomass and lipid productivity. For instance, nutrient stress (particularly nitrogen limitation) is a well-established strategy to enhance lipid accumulation in various Chlorella species [20]. Similarly, optimizing CO₂ concentration and light path in photobioreactors can dramatically improve growth rates and hydrocarbon content, as demonstrated with Botryococcus braunii and Nannochloropsis sp., respectively [20].

Macroalgae Potential

Macroalgae (seaweed) represent another promising aquatic feedstock for third-generation biofuels, with advantages including high growth rates, no requirement for freshwater or arable land, and ability to remediate aquatic environments [19]. While macroalgae typically have lower lipid content compared to microalgae, they contain high concentrations of carbohydrates (e.g., alginate, laminarin) suitable for fermentation into bioethanol or biogas through anaerobic digestion [19]. The cultivation of macroalgae for bioenergy is less developed than microalgae systems but offers potential for integrated multi-trophic aquaculture systems that combine energy production with environmental benefits.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Cultivation Systems and Conditions

Advanced cultivation methodologies form the foundation of successful third-generation biofuel production from algal feedstocks. Two primary cultivation systems dominate current research and commercial applications:

Photobioreactors (PBRs): Closed systems offering precise control over environmental parameters including temperature, light intensity, pH, CO₂ concentration, and nutrient delivery [20]. These systems typically achieve higher biomass productivity and prevent contamination but require substantial capital investment and operational costs. Specific experimental parameters include temperature ranges of 25–35°C for most species, light intensity between 150–710 µmol/m²/s, and CO₂ concentrations ranging from 2–20% [20]. For instance, Botryococcus braunii showed optimal growth at 20% CO₂ concentration with biomass productivity reaching 2.31 g/L/day [20].

Open Pond Systems: Raceway ponds, circular ponds, and unstirred ponds represent more economical alternatives, utilizing natural light and atmospheric CO₂ [21]. While cost-effective for large-scale cultivation, they face challenges with contamination, water evaporation, and less controllable growth conditions, potentially leading to lower productivity compared to PBRs.

Experimental optimization of cultivation conditions focuses on maximizing biomass productivity and target compound accumulation (lipids for biodiesel, carbohydrates for bioethanol). Key parameters include nutrient manipulation (particularly nitrogen and phosphorus limitation to induce lipid accumulation), light path optimization (shorter light paths ~10 cm enhance productivity in Nannochloropsis sp.), and carbon source supplementation (e.g., glycerol utilization in Schizochytrium strains) [20].

Downstream Processing and Conversion Pathways

The conversion of algal biomass to biofuels involves multiple downstream processing steps, each with specific experimental protocols:

Harvesting and Dewatering: Microalgae harvesting presents significant technical challenges due to their small size (typically 1–20 µm) and low culture densities (0.5–5 g/L) [3]. Common laboratory and commercial methods include centrifugation (high efficiency but energy-intensive), flocculation (using chemical, organic, or bio-based flocculants), filtration, and floatation. Dewatering typically concentrates biomass from ~0.1% to 5–25% solid content [22].

Lipid Extraction and Transesterification: For biodiesel production, lipids must be extracted from algal biomass and converted to fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) through transesterification. Experimental protocols include:

- Solvent Extraction: Bligh and Dyer method using chloroform-methanol mixtures [19]

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction: Utilizing CO₂ at supercritical conditions for cleaner extraction [20]

- Transesterification: Acid- or base-catalyzed reaction with methanol (typically at 60–70°C for 1–2 hours) with methanol-to-oil molar ratios of 6:1 to 9:1 [19]

Thermochemical Conversion: Alternative pathways include:

- Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL): Converts wet algal biomass (15–20% solid content) to biocrude at moderate temperatures (250–374°C) and high pressure (5–20 MPa), avoiding energy-intensive drying [22]

- Pyrolysis: Thermal decomposition in absence of oxygen at 300–600°C to produce bio-oil, syngas, and biochar [19]

Biochemical Conversion:

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for algal biofuel production, integrating both cultivation and downstream processing pathways:

Diagram Title: Algal Biofuel Production Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Cutting-edge research in third-generation biofuels relies on specialized reagents, equipment, and biological materials. Table 3 catalogues essential components of the experimental toolkit for algal biofuel research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Algal Biofuel Research

| Category | Item | Specific Examples/Models | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivation Systems | Photobioreactors | Stirred-tank, airlift, tubular, flat-panel [20] | Controlled biomass production with optimized light and CO₂ delivery |

| Open Ponds | Raceway ponds, circular ponds | Large-scale, cost-effective cultivation | |

| Growth Media | Nutrient Solutions | BG-11, F/2, Bold's Basal, wastewater [20] | Provide essential macronutrients (N, P, K) and micronutrients |

| Analytical Instruments | Lipid Analysis | GC-MS, GC-FID, Nile red staining | Quantify and characterize lipid content and fatty acid profiles |

| Biomass Assessment | Spectrophotometer, dry weight measurement, cell counters | Monitor growth kinetics and biomass concentration | |

| Carbohydrate Analysis | HPLC, phenol-sulfuric acid method | Quantify carbohydrate content for fermentation potential | |

| Harvesting & Processing | Flocculants | Chitosan, alum, ferric chloride, electroflocculation [3] | Aggregate microalgal cells for efficient harvesting |

| Cell Disruption | Sonication, bead milling, microwave, enzymatic lysis | Break cell walls to enhance lipid/extract recovery | |

| Conversion | Catalysts | Acid/alkali catalysts, nano-catalysts, lipases [20] | Facilitate transesterification for biodiesel production |

| Solvents | Hexane, chloroform-methanol mixtures, supercritical CO₂ [20] | Extract lipids from biomass | |

| Biological Materials | Model Microalgae | Chlorella vulgaris, Nannochloropsis sp., Botryococcus braunii [20] | Reference organisms for fundamental and applied research |

| Genetically Modified Strains | CRISPR-edited high-lipid strains [20] [3] | Enhanced productivity and tailored composition |

The toolkit continues to evolve with emerging technologies, particularly in the realm of genetic engineering. CRISPR-based genome editing tools enable precise modifications to algal strains to enhance lipid productivity, improve growth rates, and tailor fatty acid profiles for specific fuel applications [20] [3]. Additionally, nanomaterial-assisted cultivation strategies are being developed to improve light penetration and nutrient delivery in dense algal cultures [20].

Sustainability Assessment and Future Directions

Environmental Impact and Circular Bioeconomy

Third-generation biofuels offer significant sustainability advantages over their predecessors, particularly through their integration potential with circular economy principles. Life-cycle assessment (LCA) studies demonstrate that algae-based biofuel pathways can achieve substantially lower GHG emissions compared to first- and second-generation alternatives, with some scenarios showing net-negative emissions [22]. A key sustainability feature is algae's ability to utilize wastewater as a nutrient source and industrial flue gases as a carbon source, simultaneously treating waste streams while producing valuable biomass [20] [21]. This dual-function approach transforms environmental liabilities into resources, creating synergistic systems that address multiple sustainability challenges simultaneously.

The carbon sequestration potential of microalgae is particularly noteworthy, with studies indicating that 1.5–1.8 kg of CO₂ can be fixed per kilogram of dry biomass produced [20]. When cultivated using concentrated CO₂ sources like industrial flue gases, algae-based systems can potentially sequester 2.7 tonnes of CO₂ per hectare daily [21]. This exceptional carbon fixation capacity, combined with high areal productivity (algae can yield >100 tons of biomass per hectare annually [20]), positions third-generation biofuels as potentially carbon-negative energy sources when optimized systems are deployed at scale.

Current Challenges and Research Frontiers

Despite their significant promise, third-generation biofuels face substantial challenges that must be addressed to achieve commercial viability:

Economic Hurdles: High production costs remain the primary barrier to commercialization, with cultivation, harvesting, and processing all contributing to economic challenges [20] [16]. Current estimates suggest production costs are 50% higher than first-generation alternatives [17].

Technical Limitations: Scaling up from laboratory to industrial operations presents difficulties in maintaining productivity, with issues including light limitation in dense cultures, contamination control, and energy-intensive harvesting [20] [3].

Resource Management: While algae don't require arable land, they need significant water and nutrient inputs, though these can be supplied through wastewater and flue gases [3].

Active research frontiers addressing these challenges include:

Genetic and Metabolic Engineering: CRISPR-based technologies are being employed to develop strains with enhanced lipid productivity, improved photosynthesis efficiency, and secretion capabilities to simplify downstream processing [20] [3].

Advanced Photobioreactor Design: Innovations in reactor geometry, light delivery systems, and mixing technologies aim to maximize light utilization efficiency and biomass productivity [20].

Integrated Biorefineries: Developing multi-product systems that co-produce biofuels with high-value compounds (e.g., astaxanthin, omega-3 fatty acids, proteins) to improve economic viability [20] [19].

Novel Harvesting Technologies: Exploring electrochemical methods, bio-flocculation, and automated harvesting systems to reduce energy consumption and costs [3].

The following diagram illustrates the classification of biofuels by generation, highlighting the evolutionary trajectory of feedstock development:

Diagram Title: Biofuel Generations Classification

Third-generation biofuels derived from algal and aquatic feedstocks represent a paradigm shift in sustainable fuel production, offering compelling advantages over previous generations through their exceptional productivity, minimal land footprint, and potential for carbon-negative operation. The experimental data comprehensively summarized in this review demonstrates that microalgae species such as Chlorella, Nannochloropsis, and Botryococcus braunii can achieve lipid productivities far exceeding those of terrestrial oil crops, with the additional benefit of utilizing non-arable land and waste resources. While significant challenges in economic viability and scale-up persist, emerging technologies in genetic engineering, photobioreactor design, and integrated biorefining promise to address these limitations.

The comparative analysis presented herein substantiates that third-generation biofuels hold distinctive potential in the portfolio of renewable energy solutions, particularly for applications where electrification remains challenging, such as aviation and heavy transport. As research advances in CRISPR-based strain improvement, nanomaterial-assisted cultivation, and advanced conversion technologies, the commercial prospects for algae-based biofuels continue to strengthen. For the research community, priorities should include developing standardized assessment protocols, advancing fundamental understanding of algal metabolism, and demonstrating integrated systems at pilot scale to bridge the gap between laboratory promise and commercial reality in the global transition toward sustainable energy systems.

The transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy has positioned biofuels as a pivotal component of the global strategy for decarbonizing the transportation sector. Within this context, biofuels are categorized into generations based on their feedstock and technological maturity. First-generation biofuels are derived directly from food crops, such as corn, sugarcane, and vegetable oils [24]. Second-generation biofuels utilize non-food biomass, including agricultural residues (e.g., straw, husks) and dedicated non-food energy crops (e.g., switchgrass), thereby aiming to circumvent the food-fuel conflict [14] [23]. Third-generation biofuels, which often involve algal feedstocks, represent a further technological advancement [23] [24]. While first-generation biofuels benefit from established production technologies and significant policy support, their dependence on food crops has ignited a persistent "Fuel vs. Food" debate [25] [26]. This debate centers on the competition between the use of agricultural resources for energy production versus food security, a challenge that is less pronounced for advanced biofuel generations. This article objectively compares the performance of first-generation biofuels against subsequent generations, with a specific focus on the empirical data and sustainability metrics that underpin this central dilemma.

Quantitative Comparison: Feedstock, Land Use, and Emissions

The following tables synthesize key quantitative data from recent studies and forecasts, providing a direct comparison of the environmental and economic footprints of different biofuel generations.

Table 1: Biofuel Feedstock Composition and Land Use Efficiency (2024-2034 Projections)

| Metric | First-Generation Biofuels | Second-Generation Biofuels |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant Feedstocks | Maize (60%), Sugarcane (22%), Vegetable Oils (e.g., Soybean, Rapeseed, Palm Oil) [12] | Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., agricultural residues, wood, municipal waste) [14] [24] |

| Global Ethanol Feedstock Share (Base Period) | 90% from food-based feedstocks [12] | Cellulosic feedstocks not expected to substantially increase share by 2034 [12] |

| Land Footprint | ~30 million acres of U.S. corn used for ethanol; supplies only ~4% of U.S. transport fuel [25] | Utilizes waste residues; does not directly require new agricultural land [14] [24] |

| Land Use Alternative | Land used for biofuels could feed 1.3 billion people [26] | 3% of land used for biofuel crops could produce equivalent energy via solar panels [26] |

Table 2: Environmental Impact and Economic Performance Indicators

| Indicator | First-Generation Biofuels | Second-Generation & Advanced Biofuels |

|---|---|---|

| GHG Emissions vs. Fossil Fuels | Emit ~16% more CO₂ than the fossil fuels they replace when accounting for land-use change [26]; Corn ethanol has 24% higher emissions intensity than gasoline [25] | Offer lower life-cycle GHG emissions; critical for decarbonizing aviation and shipping [23] [27] |

| Water Consumption | ~3,000 liters of water needed to drive 100 km [26] | Data not explicitly provided in search results, but generally lower due to non-irrigated feedstocks. |

| Market Share & Growth | Dominates current market (~89.5% share in 2024) [27]; Projected CAGR of 7.1% (2025-2035) [28] | Faster growth potential; 2G market CAGR of 26.3% (2026-2035) projected [14] |

| Production Cost | Biodiesel and bioethanol priced 70-130% higher than fossil fuels in Europe [27] | High initial investment costs; government support remains necessary [12] [23] |

Experimental Analysis: Methodologies for Evaluating Biofuel Pathways

Research into the viability of different biofuel generations relies on rigorous experimental protocols to analyze feedstock composition, conversion efficiency, and environmental impact.

Experimental Protocol 1: Compositional Analysis of Feedstocks Using Autohydrolysis

Objective: To determine the compositional changes in lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., millet switchgrass, sludge) before and after autohydrolysis pretreatment, a key step in second-generation biofuel production [14].

Methodology:

- Feedstock Preparation: Raw biomass is dried and milled to a uniform particle size to ensure consistent reactivity.

- Autohydrolysis Pretreatment: The biomass is subjected to hot, compressed water in a reactor. This process hydrolyzes hemicellulose, resulting in a solid residue with an altered composition and a liquid stream containing hemicellulose-derived sugars.

- Compositional Analysis: The original biomass and the solid residue after autohydrolysis are analyzed using standardized methods (e.g., NREL protocols) to determine the percentage composition of:

- Cellulose: The primary target for enzymatic hydrolysis to glucose.

- Hemicellulose: A polysaccharide that is partially solubilized during pretreatment.

- Lignin: A complex polymer that provides structural integrity and is recalcitrant to hydrolysis.

- Ash, Resins, Fats, and Soluble Substances.

Key Findings from Cited Data: Autohydrolysis of millet switchgrass increased cellulose content from 46.7% to 53.9% and reduced hemicellulose from 23.0% to 10.6%, thereby enriching the solid residue for subsequent enzymatic saccharification [14].

Experimental Protocol 2: Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) of Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Objective: To quantify and compare the total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of a biofuel (e.g., corn ethanol) against a fossil fuel baseline (e.g., gasoline) throughout its entire lifecycle [25] [26].

Methodology:

- System Boundary Definition: The assessment includes all stages from "cradle-to-grave":

- Feedstock Production: Agricultural inputs (fertilizer, pesticide production, and application), farm machinery use, and irrigation.

- Land-Use Change (LUC): Direct (conversion of natural landscapes to cropland) and indirect (iLUC) changes triggered by increased crop demand.

- Feedstock Transport: Energy for transporting raw materials to biorefineries.

- Fuel Production: Energy consumption and emissions from the conversion process (e.g., fermentation, distillation).

- Fuel Combustion: Emissions from burning the fuel in an engine.

- Data Inventory: Collecting activity data (e.g., amount of fertilizer used per hectare) and emission factors (e.g., CO₂ emitted per kg of fertilizer).

- Impact Assessment: Calculating the total CO₂-equivalent emissions, giving particular weight to the impact of land-use change, which is a major contributor to the carbon debt of first-generation biofuels [25].

Key Findings from Cited Data: A study incorporating land-use change found that the carbon intensity of corn ethanol from 2005-2019 was 24% higher than that of gasoline [25]. A separate analysis concluded that biofuels, on average, emit 16% more CO₂ than the fossil fuels they replace [26].

The logical relationships and workflow for assessing the core "Fuel vs. Food" debate and its connection to experimental analysis are summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biofuel Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofuel Feedstock Analysis

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Cellulases | Enzyme cocktails that hydrolyze cellulose into fermentable glucose sugars; critical for evaluating second-generation biofuel yield from pretreated biomass [29]. |

| Amylases | Enzymes that catalyze the breakdown of starch into sugars; essential for the production of first-generation bioethanol from corn and other grains [29]. |

| Industrial Lipases | Enzymes used to catalyze the transesterification of vegetable oils or fats into biodiesel, a key process for first-generation biodiesel and HVO production [29]. |

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Non-food feedstock (e.g., switchgrass, rice husks, wheat straw) used in compositional analysis and process optimization for second-generation biofuels [14] [24]. |

| Autohydrolysis Reactor | Equipment used for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass with hot water to solubilize hemicellulose and improve enzymatic accessibility to cellulose [14]. |

The empirical data and comparative analysis presented herein underscore the fundamental sustainability challenge posed by first-generation biofuels: their reliance on food-based feedstocks creates an intractable competition with global food systems, often leading to adverse environmental and socioeconomic outcomes. While second-generation pathways offer a promising alternative by utilizing waste residues and non-food biomass, they currently face significant economic and scalability hurdles [12] [23]. The future of biofuels within a comprehensive sustainable energy strategy hinges on continued research and development aimed at overcoming these barriers. Key directions include the optimization of enzymatic cocktails for lignocellulosic conversion, the integration of AI and data science for supply chain efficiency, and robust policy frameworks that prioritize truly sustainable alternatives, particularly for hard-to-electrify sectors like aviation and shipping [23] [30] [27].

The transition from fossil-based energy to sustainable alternatives is a cornerstone of global decarbonization efforts. Among these alternatives, biofuels have emerged as a promising solution, evolving through distinct generations characterized by their feedstocks and production technologies. First-generation biofuels (1G) utilize food crops, second-generation (2G) rely on non-food lignocellulosic biomass, and third-generation (3G) leverage algae and microbial systems [4] [22]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these generations based on three critical sustainability metrics: greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, land use, and water footprint. The objective is to offer researchers, scientists, and policy makers a data-driven overview of their environmental performance to inform future research, development, and policy decisions.

Comparative Analysis of Sustainability Metrics

The environmental performance of biofuel generations varies significantly, influenced by feedstock cultivation requirements, conversion processes, and technological maturity. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics for a comparative overview.

Table 1: Comparative Sustainability Metrics for Biofuel Generations

| Metric | First-Generation (1G) | Second-Generation (2G) | Third-Generation (3G) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | Moderate to High | Lower than 1G; can be carbon negative [22] | Highly variable; can be very low or negative (e.g., -102 g CO₂eq/MJ [22]) |

| Land Use Impact | High (competes with food, risk of deforestation [31]) | Lower than 1G; uses marginal land or waste [10] | Lowest; does not require arable land [10] [4] |

| Water Footprint (m³/GJ) | High (high blue water footprint [32]) | Lowest (when using residues [32]) | Highest blue water footprint [32]; High total water consumption [33] |

| Feedstock Examples | Corn, sugarcane, soybean oil | Agricultural residues, switchgrass, miscanthus, woody biomass | Microalgae (e.g., Chlorella), macroalgae (e.g., Enteromorpha clathrata) |

| Key Sustainability Challenges | Food vs. fuel debate, land-use change emissions [31] | Techno-economic viability, complex conversion processes [10] | High energy and cost of cultivation and harvesting [10] [4] |

Detailed Metric Analysis

Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions

Life-cycle assessment (LCA) is the standard methodology for evaluating the global warming potential of biofuels, from feedstock cultivation to fuel combustion (well-to-wheel) [22]. First-generation biofuels often exhibit moderate to high GHG emissions, particularly when indirect land-use change (iLUC) from converting forests or grasslands is accounted for [31] [34]. Second-generation biofuels demonstrate a significant improvement; for instance, bio-gasoline from miscanthus can achieve a negative GWP of -102 g CO₂eq/MJ when soil carbon sequestration is considered [34]. Third-generation pathways show the most promise, with some scenarios yielding negative net emissions. For example, algae hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) can achieve very low emissions, and combined algae processing (CAP) can also result in negative net emissions [22]. A study on macroalgae (Enteromorpha clathrata) biofuel reported a GWP of 8,823.73 kg CO₂eq per tonne of biofuel for the most efficient process [33].

Land Use

Land use intensity and associated land-use change (LUC) emissions are critical metrics. First-generation biofuels have the highest land-use impact due to direct competition with food production, which can lead to deforestation and biodiversity loss to bring new land into cultivation [31]. Second-generation biofuels, using agricultural residues or dedicated energy crops on marginal land, drastically reduce this pressure [10]. One study notes that including cropland intensification in modeling reduces land use change and its associated emissions [34]. Third-generation biofuels, particularly those from algae, have a distinct advantage as they do not require arable land and can be cultivated in ponds or photobioreactors on non-productive land [10] [4], virtually eliminating competition with food crops.

Water Footprint

The water footprint (WF) is disaggregated into green water (rainwater), blue water (surface and groundwater), and grey water (required to assimilate pollutants) [32] [35]. First-generation biofuels typically have a high total water footprint, with significant blue water consumption for irrigation. Second-generation biofuels from agricultural residues have the smallest water footprint, as the water is attributed primarily to the food crop production [32]. In contrast, while third-generation algae biofuels do not require freshwater, their cultivation in open ponds or photobioreactors can have the largest blue water footprint due to high evaporation and maintenance of cultures [32]. For example, the water consumption for biofuel from Enteromorpha clathrata ranges from 206 to 258 m³ per tonne of biofuel depending on the process [33].

Experimental Protocols and Life-Cycle Assessment

Robust comparison of biofuel sustainability relies on standardized methodologies, primarily Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) and economic modeling.

Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) Methodology

LCA is a comprehensive framework for evaluating environmental impacts across a product's entire life cycle [22]. The standard protocol involves four stages:

- Goal and Scope Definition: The system boundaries are defined, typically on a well-to-wheel basis for biofuels, encompassing feedstock cultivation, processing, transportation, and combustion [22]. The functional unit (e.g., 1 MJ of energy or 1 km driven) is established.

- Life-Cycle Inventory (LCI): This involves data collection on all energy and material inputs and environmental releases associated with each stage of the life cycle. For biofuels, this includes data on fertilizer use, fuel for farming, electricity for processing, and chemical inputs [33].

- Life-Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): The inventory data is translated into impact categories. Key categories for biofuels are Global Warming Potential (GWP, in kg CO₂ equivalent), water consumption (m³), and land use (m²a crop eq) [33] [22].

- Interpretation: Results are analyzed to draw conclusions, identify hotspots, and assess sensitivity.

Advanced LCA models like the Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation (GREET) model are widely used for such analyses [22]. Furthermore, the GTAP-BIO model is specifically designed to estimate biofuel policy-induced global land-use changes and the consequent GHG emissions, incorporating economic data and trade flows [34].

Key Experimental Setups from Literature

- Objective: To evaluate the environmental impact and water footprint of biofuel production from the macroalgae Enteromorpha clathrata.

- Feedstock Preparation: Enteromorpha clathrata biomass was dried and crushed into powder.

- Pyrolysis Experiments: Three pyrolysis pathways were investigated:

- General Pyrolysis (ENPY): Pyrolysis without a catalyst.

- Catalytic Pyrolysis with ZSM-5 (ENZSM): Using a commercial ZSM-5 zeolite catalyst.

- Self-derived Catalytic Pyrolysis (ENC): Using biochar catalyst produced from the algae itself.

- Analysis: The yields of bio-oil, biochar, and syngas were measured for each pathway. The bio-oil from each process was then upgraded and analyzed in a simulated full-scale production system.

- LCA & WF Assessment: A life-cycle assessment and water footprint analysis were conducted for each pathway, calculating the Global Warming Potential and Water Consumption per tonne of biofuel produced.

- Objective: To compare the environmental impacts of second- and third-generation biorefinery pathways.

- Model: The GREET model was used to simulate energy consumption, GHG emissions, and water requirements.

- Pathways Analyzed:

- Pathway I (3G): Algae Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) to renewable diesel.

- Pathway II (3G): Combined Algae Processing (CAP) to renewable diesel.

- Pathway III (2G): Palm Fatty Acid Distillation (PFAD) to renewable diesel.

- System Boundary: A well-to-wheel framework was applied, and the U.S. electricity grid mix was used as the default energy source for all pathways to ensure consistency.

The logical workflow for such comparative analyses is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental research and life-cycle assessment of biofuels rely on a suite of specific reagents, models, and analytical techniques.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Biofuel Sustainability Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| GREET Model | A specialized LCA model for evaluating energy use and emissions in transportation fuels. [22] | Comparing WTW emissions of different biorefinery pathways. [22] |

| GTAP-BIO Model | A computable general equilibrium model for analyzing economic and land-use change impacts of biofuel policies. [34] | Estimating indirect land-use change (iLUC) emissions from expanded biofuel production. [34] |

| ZSM-5 Zeolite | A heterogeneous acid catalyst used to upgrade pyrolysis vapors, improving bio-oil quality and composition. [33] | Catalytic pyrolysis of microalgae or lignocellulosic biomass to increase oil yield and deoxygenation. [33] |

| Self-derived Biochar | A catalyst produced from the pyrolysis of the biomass feedstock itself, promoting circularity. [33] | Used as a sustainable catalyst in algal pyrolysis, reducing process emissions and waste. [33] |

| Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) Reactor | A system that converts wet biomass into bio-crude using high temperature and pressure, avoiding energy-intensive drying. [22] | Processing wet microalgae or macroalgae into a stable bio-oil intermediate. [22] |

The evolution from first- to third-generation biofuels represents a clear trajectory toward improved sustainability, particularly in reducing land-use impacts and life-cycle GHG emissions. Second-generation biofuels effectively address the food-versus-fuel dilemma and offer lower emissions, while third-generation biofuels, especially from algae, present a paradigm shift with minimal land requirements and potential for carbon-negative pathways. However, this evolution also introduces new challenges, most notably the high blue water footprint associated with large-scale algae cultivation. Future research should prioritize the development of energy- and water-efficient cultivation systems, advanced catalysts for conversion, and the integration of robust LCA with economic modeling to guide the commercialization of the most sustainable biofuel pathways.

Production Pathways: From Biomass to Biofuel through Biochemical and Thermochemical Conversion

The transition from fossil-based fuels to sustainable alternatives has positioned biofuels at the forefront of renewable energy research. Central to biofuel production is biochemical conversion, a process that transforms biomass into liquid fuels through biological catalysts. This process is particularly critical for second-generation biofuels, which utilize non-food lignocellulosic biomass such as agricultural residues, dedicated energy crops, and wood, thereby avoiding the food-versus-fuel debate associated with first-generation biofuels [3] [2]. The biochemical conversion pathway primarily involves three interconnected stages: pretreatment to break down the recalcitrant lignocellulosic structure, enzymatic hydrolysis to depolymerize polysaccharides into fermentable sugars, and fermentation where microorganisms convert these sugars into target products like ethanol or other biofuels [36] [37].

The sustainability and economic viability of different biofuel generations are subjects of extensive research. First-generation biofuels, derived from food crops like corn and sugarcane, face limitations due to their competition with food supply and arable land use [3] [2]. Second-generation biofuels, the focus of this guide, offer a more sustainable profile by converting non-food biomass, though they contend with technical challenges related to biomass recalcitrance [3]. Third-generation biofuels, typically derived from algae, present a promising future alternative but currently face economic and scaling challenges [3] [38]. Within this context, the efficiency of the biochemical conversion process—from pretreatment to fermentation—is a decisive factor in the commercial success and environmental performance of second-generation biofuel technologies [36] [37]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the core operational units, supported by experimental data, to inform research and development in the field.

Comparative Analysis of Pretreatment Strategies

Pretreatment is a critical first step in the biochemical conversion of lignocellulosic biomass. Its primary objective is to disrupt the robust, heterogeneous structure of plant cell walls—comprising cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—to facilitate enzymatic access to cellulose fibers for subsequent hydrolysis [39] [37]. An effective pretreatment method must maximize sugar yield, minimize energy and chemical input, avoid the formation of fermentation inhibitors, and be economically viable at scale.

The following table summarizes the performance of various pretreatment methods based on recent research, highlighting their impact on sugar release and energy efficiency.

Table 1: Comparison of Pretreatment Methods for Lignocellulosic Biomass

| Pretreatment Method | Biomass Tested | Key Operational Parameters | Sugar Yield / Glucose Conversion | Energy Efficiency (kg glucose/kWh) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaline (NaOH) | Barley Straw, Bean Straw [39] | NaOH concentration, Ambient to moderate temperature | Barley: ~140 mg/gTS (48% conversion); Bean: ~171 mg/gTS (86% conversion) [39] | 1.7 (Barley), 1.9 (Bean) [39] | Most energy-efficient; effective lignin and acetyl removal; effluents showed no negative effect on seed germination [39]. |

| Microwave-Assisted Alkaline (MAA) | Coconut Husk [40] | 5% w/v NaOH, 2450 MHz, 20 min | 0.279 g sugar/g substrate [40] | Not specified | Highest sugar yield among methods tested; significantly increased cellulose content from ~20% to ~39%; drastically reduced lignin [40]. |

| Deacetylated Disc-Refining (DDR) | Corn Stover, Poplar, Switchgrass [37] | NaOH (60-100 g/kg biomass), Disc refining (gap: 0.001-0.015 in) | High conversion yields; Varies by feedstock [37] | Not specified | Does not generate inhibitors (HMF, Furfural); removes >90% acetyl and significant lignin; sugar loss is significantly lower than dilute acid pretreatment [37]. |

| Ultrasonication (US) + Alkaline | Bean Straw [39] | Combination of US and NaOH | 171 mg/gTS (86% conversion) [39] | Lower than Alkaline alone [39] | Combined physical/chemical disruption improved sugar release, but energy costs were higher than alkaline pretreatment alone [39]. |

| Dilute Acid | Corn Stover (Benchmark) [37] | Dilute H2SO4, High temperature | High sugar yield, but with significant sugar degradation [37] | Not specified | Produces fermentation inhibitors (HMF, furfural, acetate); leads to significant sugar loss due to degradation [37]. |

Experimental Protocol: Alkaline Pretreatment

The high efficiency and favorable sustainability profile of alkaline pretreatment, as shown in Table 1, make it a benchmark process. The detailed methodology from a comparative study is as follows [39]:

- Feedstock Preparation: Barley and bean straws are knife-milled and sieved to achieve a particle size below 2 mm.

- Alkali Loading: The biomass is treated with a sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution.

- Reaction Conditions: The mixture is incubated, typically at ambient or moderately elevated temperatures (e.g., 40°C) for a defined period (e.g., 24 hours) with agitation (e.g., 150 rpm).

- Solid-Liquid Separation: After treatment, the slurry is filtered to separate the solid fraction (pretreated biomass) from the liquid fraction (black liquor containing dissolved lignin and other components).

- Washing: The solid fraction is washed with distilled water until a neutral pH is reached to remove residual alkali and dissolved compounds.

- Drying: The washed solids are dried in an oven to remove excess moisture before proceeding to enzymatic hydrolysis.

This protocol effectively swells the biomass, severs the linkages between lignin and carbohydrates, and disrupts the lignin structure, thereby increasing the accessible surface area of cellulose for enzymes [39] [40].

Pretreatment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for pretreatment and the subsequent stages of biochemical conversion, highlighting the decision points for different methods.

Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Releasing Fermentable Sugars

Following pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis converts the exposed cellulose and hemicellulose into monomeric sugars, primarily glucose and xylose. This process employs a cocktail of enzymes, including endoglucanases, cellobiohydrolases, and β-glucosidases, which work synergistically to break down cellulose into glucose [36]. A key modern advancement is the inclusion of Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenases (LPMOs). LPMOs are copper-dependent enzymes that perform oxidative cleavage of glycosidic bonds, creating new chain ends for classical cellulases to act upon, thereby significantly boosting saccharification efficiency [36].

However, LPMO activity requires a co-substrate (molecular oxygen) and a reductant to function. The necessity of oxygen for LPMO activity creates a process design challenge, as it can conflict with the anaerobic conditions preferred by many fermentation microorganisms [36]. The choice of enzymatic cocktail and the management of reaction conditions (e.g., temperature, oxygen availability, mixing) are therefore critical for achieving high sugar yields.

Experimental Protocol: Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Pretreated Biomass

A standard protocol for enzymatic hydrolysis, as applied to pretreated solids, involves the following steps [40]:

- Substrate Loading: The washed and pretreated biomass is loaded into a reactor at a defined solids loading (e.g., 1% w/v).

- Buffer Addition: A suitable buffer is added to maintain an optimal pH for the enzymes (typically around pH 5.0 for many commercial cellulase preparations).

- Enzyme Dosing: Commercial enzyme cocktails (e.g., Celluclast 1.5L) are added to the slurry at a specified dosage, often expressed in terms of mg of protein per g of dry substrate or Filter Paper Units (FPU) per g.

- Reaction Conditions: The hydrolysis is carried out in a shaking incubator at an optimal temperature (e.g., 50°C) with agitation (e.g., 150 rpm) for a period of several hours to several days (e.g., 5 days).

- Sampling and Analysis: Samples are withdrawn periodically, centrifuged to remove solids, and the supernatant is analyzed for sugar content using methods like the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) assay for reducing sugars or HPLC for specific sugar identification and quantification [40].

Fermentation Strategies and Process Configuration

The final stage involves microbial fermentation of the sugar hydrolysate into biofuels. The choice of microorganism and the integration of hydrolysis and fermentation steps are pivotal for overall process yield and productivity. Engineered strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that can co-ferment both glucose and xylose are widely used to maximize carbon conversion [36] [37]. Process configuration plays a major role in mitigating challenges such as end-product inhibition of enzymes and fulfilling the oxygen requirements of LPMOs.

Table 2: Comparison of Process Configurations for Saccharification and Fermentation

| Process Configuration | Description | Key Experimental Findings | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separate Hydrolysis and Fermentation (SHF) | Hydrolysis and fermentation are performed in separate reactors sequentially. | Not the primary focus of recent comparative studies. | Allows each step to run at its optimal temperature (~50°C for hydrolysis, ~30°C for fermentation). | Suffers from end-product inhibition of cellulases by accumulating sugars [36]. |

| Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation (SSF) | Enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation occur concurrently in a single reactor. | Faster consumption of hexose sugars; >90% xylose consumption by end of fermentation; better ethanol productivity and initial yield than HHF [36]. | Reduced end-product inhibition as sugars are immediately consumed by the microorganism [36]. | Suboptimal temperature compromise (~35°C); LPMO activity may be limited due to oxygen consumption by yeast [36]. |

| Hybrid Hydrolysis and Fermentation (HHF) | Features a short, initial enzymatic hydrolysis phase (e.g., 24-48h) often with aeration, followed by SSF. | Better glucan conversion than SSF; but poorer ethanol productivity and initial yield; aeration reduced inhibitor levels (e.g., furfural) [36]. | Can boost LPMO activity with aeration in the initial phase; higher sugar levels before fermentation starts. | Aeration and higher initial temperature can complicate the process and potentially impact subsequent fermentation efficiency [36]. |

Experimental Protocol: Demonstration-Scale Fermentation

Large-scale experiments provide critical data for process scale-up. The following protocol outlines a demonstration-scale fermentation process [36]:

- Bioreactor Setup: Experiments are conducted in large-scale stirred-tank bioreactors (e.g., 10 m³ working volume).

- Inoculum Preparation: A xylose-utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain is cultivated to a suitable cell density.

- Process Configuration:

- For SSF: The pretreated lignocellulosic slurry, enzymes (LPMO-containing cellulase preparation), and yeast are added at the beginning. The process runs at ~35°C without aeration.

- For HHF: The initial phase involves adding the pretreated slurry and enzymes, with temperature controlled at a higher level (e.g., 48-50°C) and with mild aeration (e.g., 0.15 vvm) for 24-48 hours to promote LPMO-driven saccharification. The temperature is then lowered to ~35°C, the yeast is inoculated, and aeration is stopped.

- Monitoring: Parameters like pH, temperature, and off-gas are monitored. Samples are taken regularly to track sugar consumption (glucose, mannose, xylose) and product (ethanol) formation via HPLC.

- Analysis of Inhibitors: The liquid fraction is analyzed for inhibitory by-products like furfural, HMF, and aromatic compounds, typically using chromatographic methods, to assess their fate during the process [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in biochemical conversion relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biochemical Conversion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| LPMO-Containing Cellulase Preparations | Commercial enzyme cocktails containing Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenases for oxidative cleavage of cellulose, boosting hydrolysis yield. | Used in demonstration-scale SSF and HHF to enhance saccharification of pretreated softwood [36]. |

| Xylose-Utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Genetically engineered yeast strains capable of fermenting both hexose (glucose) and pentose (xylose) sugars to ethanol. | Critical for maximizing ethanol yield from lignocellulosic hydrolysates containing mixed sugars [36] [37]. |

| Cellulase (e.g., Celluclast 1.5L) | A blend of hydrolytic enzymes (endoglucanases, cellobiohydrolases) that break down cellulose into cellooligosaccharides and cellobiose. | Standard enzyme used in enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated biomass like coconut husk [40]. |

| β-Glucosidase | An enzyme that hydrolyzes cellobiose (a dimer) into glucose, relieving end-product inhibition of other cellulases. | Often used to supplement cellulase cocktails to achieve complete conversion to glucose. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | A strong alkaline chemical used in pretreatment to solubilize lignin and hemicellulose, reducing biomass recalcitrance. | Key reagent in alkaline, MAA, and DDR pretreatments [39] [37] [40]. |

| Dilute Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | A strong acid used in pretreatment to hydrolyze hemicellulose into soluble sugars, but can lead to inhibitor formation. | Used in dilute acid pretreatment, a common benchmark method [37]. |

Integrated View and Sustainability Context

The interconnection between pretreatment efficiency, hydrolysis yield, and fermentation performance is fundamental to the sustainability of second-generation biofuels. Efficient pretreatment directly reduces the enzyme loading required for hydrolysis, which is a major cost driver [36] [39]. Furthermore, pretreatment strategies like Deacetylated Disc-Refining (DDR) that avoid producing microbial inhibitors (furfural, HMF) enable more robust and productive fermentation, leading to higher overall biofuel yields and improved process economics [37].

When placed in the broader context of biofuel generations, the technical advances in biochemical conversion are what make second-generation biofuels a more sustainable alternative. Life cycle assessment (LCA) studies consistently show that second-generation biofuels, when produced without causing land-use change, have significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions than first-generation biofuels and fossil fuels [2]. They also avoid the primary social and ethical concern of competing with food production [3] [2]. While third and fourth-generation biofuels from algae and genetically modified organisms promise even greater sustainability, their current technological and economic challenges highlight that optimized second-generation processes, as detailed in this guide, represent the most viable and sustainable pathway for large-scale biofuel production in the near to mid-term [3] [38] [2]. The continued refinement of pretreatment, hydrolysis, and fermentation is therefore not merely a technical pursuit but a crucial endeavor for achieving a sustainable energy future.

Syngas, a mixture primarily composed of carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H₂), serves as a vital intermediate for power generation and chemical synthesis in the transition toward renewable energy [41]. Within the framework of biofuel generations, thermochemical conversion processes like gasification and pyrolysis represent key technological pathways for producing advanced biofuels from non-food biomass, aligning them primarily with second-generation biofuel production [23] [4]. These processes utilize sustainable feedstocks such as agricultural residues, perennial grasses, and forestry waste, thereby avoiding the food-versus-fuel debate associated with first-generation biofuels [4]. Furthermore, the integration of plastic waste with biomass in co-gasification processes exemplifies the circular economy principles gaining traction in the biofuel sector, offering dual benefits of waste reduction and enhanced syngas production [41] [42].

The global transportation sector accounts for approximately 25% of energy-related CO₂ emissions worldwide, creating an urgent need for decarbonization solutions [23]. While electrification advances in passenger vehicles, sectors like aviation, shipping, and heavy-duty transport face significant challenges in transitioning away from liquid fuels. Drop-in capable sustainable fuels derived from syngas, such as renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), offer a promising solution for these hard-to-abate sectors since they can utilize existing engine technologies and fuel infrastructure without requiring major modifications [23]. This positions thermochemical conversion technologies as critical enablers in the broader landscape of sustainable fuel production.

Gasification Process Fundamentals

Gasification represents a thermochemical process that converts carbonaceous materials into primarily gaseous products through partial oxidation at elevated temperatures, typically ranging from 700°C to 900°C [43]. This process occurs in controlled environments with limited oxygen or steam, producing a synthesis gas (syngas) containing CO, H₂, CH₄, CO₂, and light hydrocarbons (C2-C4) [41]. The resulting syngas serves as a versatile intermediate for various applications, including power generation, chemical synthesis, and biofuel production through subsequent processes like Fischer-Tropsch synthesis [23].