Genome-Scale Metabolic Models: A Strategic Framework for Advanced Strain Design and Therapeutic Discovery

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represent powerful computational platforms that bridge genotype to phenotype, enabling the prediction of cellular metabolic behavior.

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models: A Strategic Framework for Advanced Strain Design and Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represent powerful computational platforms that bridge genotype to phenotype, enabling the prediction of cellular metabolic behavior. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing how GEMs guide rational strain design for bioproduction and the identification of novel therapeutic targets. We explore foundational principles, from gene-protein-reaction associations to constraint-based modeling, and delve into advanced methodologies for integrating multi-omics data. The content further addresses critical challenges in model optimization and validation, comparing single-strain versus community-level applications. Through illustrative case studies in metabolic engineering and drug discovery, we demonstrate how GEMs drive biological discovery and the creation of high-performance microbial strains, offering a strategic framework for applications in biotechnology and personalized medicine.

Core Principles of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models and Their Role in Strain Design

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational representations of the metabolic network of an organism, providing a mathematical framework to simulate metabolic fluxes and predict physiological phenotypes [1]. These models quantitatively define the relationship between genotype and phenotype by contextualizing different types of Big Data, including genomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics [1]. GEMs collect all known metabolic information of a biological system, including the genes, enzymes, reactions, associated gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules, and metabolites, forming comprehensive metabolic networks that provide predictive insights into cellular behavior [1].

The reconstruction of GEMs begins with annotating an organism's genome to identify metabolic genes, followed by compiling biochemical reactions associated with these genes and their corresponding metabolites. This network is then converted into a mathematical model that can simulate metabolic fluxes using methods such as Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), 13C-metabolic flux analysis (13C MFA), and dynamic FBA (dFBA) [1]. The development of GEMs represents a paradigm shift in systems biology, enabling researchers to move from descriptive studies to predictive modeling of complex biological systems.

Core Components and Reconstruction of GEMs

Structural Framework of GEMs

The architecture of GEMs is built upon several interconnected components that collectively represent the metabolic capabilities of an organism. The essential elements include:

- Genes: The genetic elements encoded in the organism's genome that potentially code for metabolic enzymes.

- Enzymes: Protein catalysts that facilitate biochemical transformations within the cell.

- Reactions: Biochemical transformations that convert substrates to products, including transport reactions across cellular compartments.

- Metabolites: Chemical compounds that participate as substrates or products in metabolic reactions.

- Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Rules: Boolean relationships that explicitly connect genes to enzymes and enzymes to metabolic reactions, defining essential genetic requirements for metabolic functions [1].

These components are systematically organized into a stoichiometric matrix S, where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions. The coefficients within the matrix indicate the stoichiometric relationship of each metabolite in each reaction, providing the mathematical foundation for constraint-based modeling approaches [1].

Reconstruction Workflow

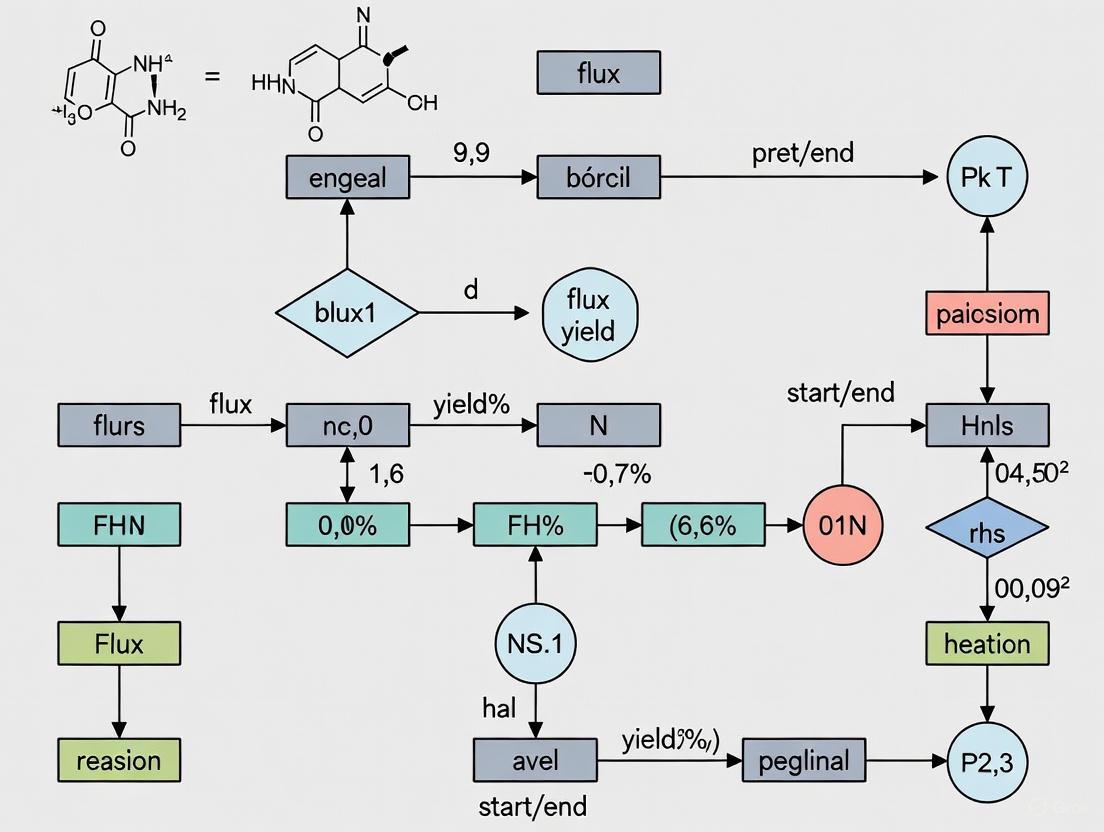

The process of reconstructing high-quality GEMs follows a systematic workflow that integrates genomic, biochemical, and physiological data. Figure 1 illustrates the comprehensive pipeline for GEM reconstruction and validation.

Figure 1. Workflow for GEM Reconstruction and Validation. The process begins with genome annotation and proceeds through draft reconstruction, curation, and mathematical formulation before validation with experimental data. Gap analysis (red) identifies missing metabolic functions, while multi-omics integration (green) enhances predictive capability.

Multi-Strain and Community GEMs

Advances in GEM reconstruction have enabled the development of multi-strain models that capture metabolic diversity across different isolates of the same species. This approach involves creating a "core" model representing metabolic functions shared by all strains and a "pan" model encompassing the union of all metabolic capabilities [1]. For example, researchers have created multi-strain GEMs from 55 individual E. coli strains, 410 Salmonella strains, and 64 S. aureus strains, enabling comparative analysis of strain-specific metabolic traits [1]. These multi-strain reconstructions provide insights into metabolic adaptations and niche specializations, with significant applications in understanding pathogenicity and host-specific interactions.

Quantitative Applications of GEMs in Strain Design

Metabolic Engineering and Bioproduction

GEMs serve as powerful platforms for guiding metabolic engineering strategies to develop microbial cell factories for industrial applications. By simulating metabolic fluxes under different genetic and environmental conditions, GEMs can identify gene knockout, knock-in, and regulatory targets that optimize the production of desired compounds while maintaining cellular growth [2]. Table 1 summarizes key applications of GEMs in metabolic engineering and strain design.

Table 1. Applications of GEMs in Metabolic Engineering and Strain Design

| Application Area | Specific Methodology | Key Outcomes | Representative Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Production | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with product maximization | Identification of gene deletion targets for enhanced product yield | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, C. glutamicum |

| Nutrient Optimization | in silico media design | Development of defined growth media supporting high cell density | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus [3] |

| Pathway Validation | 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) | Experimental validation of predicted flux distributions | E. coli, Bacillus subtilis |

| Growth Coupling | OptKnock, EvolveXGA [4] | Strategies to couple product formation with cellular growth | S. cerevisiae [4] |

| Tolerance Engineering | Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) guided by GEM predictions | Development of strains resistant to inhibitors or extreme conditions | E. coli, S. cerevisiae |

Design of Synthetic Microbial Communities

GEMs facilitate the design and optimization of synthetic microbial communities for biomedical and environmental applications. For live biotherapeutic products (LBPs), GEMs can predict metabolic interactions between exogenous therapeutic strains and resident gut microbes, helping identify strains that produce beneficial metabolites or inhibit pathogens [3]. The AGORA2 resource, which contains curated strain-level GEMs for 7,302 gut microbes, enables systematic screening of potential LBPs based on their metabolic capabilities and interaction profiles [3]. Using GEMs, researchers have identified Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium animalis as promising candidates for colitis alleviation due to their predicted antagonistic activity against pathogenic Escherichia coli [3].

Experimental Protocols for GEM-Guided Strain Design

Protocol 1: Model-Guided Adaptive Laboratory Evolution Using EvolveXGA

Introduction: EvolveXGA is a novel method for genome-scale metabolic model-guided design of strategies combining chemical environments and genetic engineering to enable adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) of desired traits, particularly heterologous production pathways [4]. This protocol describes the implementation of EvolveXGA for coupling heterologous production with cellular fitness in S. cerevisiae.

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model of target organism (e.g., S. cerevisiae)

- Python implementation of EvolveXGA (available at: https://github.com/vttresearch/EvolveXGA)

- Standard microbial culturing equipment

- Analytical instruments for metabolite quantification (HPLC, GC-MS)

Procedure:

Define Objective: Identify the target heterologous compound and reconstruct its biosynthetic pathway within the host metabolic model.

Genetic Algorithm Setup: Configure the genetic algorithm parameters to search for combinations of chemical environments and metabolic network structures that create flux coupling between product formation and biomass production.

Strategy Identification: Run EvolveXGA to identify optimal gene knockout targets and medium compositions that genetically couple target production with growth.

Strain Construction: Implement the identified gene knockouts in the host strain using appropriate genetic engineering techniques (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9).

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution: Cultivate engineered strains in the specified chemical environment under serial transfer or chemostat conditions for multiple generations.

Clone Isolation and Characterization: Isolate individual clones from evolved populations and characterize using whole-genome sequencing and quantitative metabolite analysis.

Validation: In a case study applying this approach to glycolic acid production in S. cerevisiae, three out of six evolved isolates demonstrated improved glycolic acid yield from glucose compared to a non-optimized control strain [4]. The logical workflow for this protocol is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. EvolveXGA Workflow for Coupling Production with Fitness. The method identifies genetic and environmental modifications that force flux coupling between target production and biomass formation, enabling adaptive evolution of production strains.

Protocol 2: GEM-Guided Live Biotherapeutic Product Development

Introduction: This protocol outlines a systematic framework for using GEMs in the screening, evaluation, and design of live biotherapeutic products (LBPs), with applications in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and Parkinson's disease (PD) [3].

Materials:

- AGORA2 database or other repository of strain-level GEMs

- Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) tools

- Metagenomic data from target patient populations

- Anaerobic culturing equipment

Procedure:

Candidate Screening:

- Top-down approach: Retrieve GEMs for microbes isolated from healthy donor microbiomes from AGORA2 database. Simulate production of therapeutic metabolites (e.g., SCFAs) and antagonistic interactions with pathogens.

- Bottom-up approach: Define therapeutic objectives based on omics analysis of disease states. Screen AGORA2 GEMs for strains that address identified metabolic deficiencies.

Quality Assessment:

- Predict growth rates of candidate strains under gastrointestinal conditions using FBA.

- Simulate pH tolerance by incorporating pH-specific reactions (e.g., proton leakage, phosphate transport).

- Evaluate production potential of postbiotics under different dietary conditions.

Safety Evaluation:

- Assess potential for antibiotic resistance gene transfer using pattern analysis.

- Predict drug-metabolite interactions by integrating biotransformation reactions.

- Evaluate potential for detrimental metabolite production under disease conditions.

Multi-Strain Formulation Design:

- Simulate metabolic interactions between candidate strains using community modeling approaches.

- Identify synergistic strains that exhibit cross-feeding or complementary functions.

- Avoid combinations with competitive nutrient uptake patterns.

Personalization:

- Incorporate patient-specific microbiome composition data.

- Account for individual dietary patterns and medication regimens.

- Validate predictions using in vitro models and animal studies.

Validation: This framework has been applied to identify Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium animalis as promising LBP candidates for colitis alleviation based on their predicted antagonistic activity against pathogenic Escherichia coli [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2. Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GEM Research

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Strains | E. coli DH5α | endA1, recA1 mutations for improved plasmid stability | Routine molecular cloning [5] |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | T7 RNA polymerase gene for high-level protein expression | Recombinant protein production [5] | |

| E. coli MDS42 | Reduced genome (15% deletion) with improved genetic stability | Synthetic biology, bioproduction [5] | |

| GenScript Poly(A) Strain V2/V3 | Enhanced stability of poly(A) sequences | mRNA template plasmid propagation [5] | |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Precise genome editing with high efficiency | Gene knockouts/knock-ins in C. glutamicum [5] |

| CRISPR/Cas12a systems | Alternative CRISPR system with different PAM requirements | Gene editing in high GC-content organisms [5] | |

| Computational Resources | AGORA2 | Curated GEMs for 7,302 gut microbes | LBP development, host-microbiome interactions [3] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling | FBA, phenotype simulation [1] | |

| EvolveXGA | Python implementation for ALE strategy design | Coupling production with fitness [4] | |

| Analytical Instruments | HPLC, GC-MS | Quantitative metabolite analysis | Validation of metabolic production [4] |

Genome-scale metabolic models represent a transformative technology in systems biology, providing a comprehensive framework for simulating metabolic behavior and guiding strain design strategies. The integration of GEMs with advanced computational algorithms and experimental methodologies has enabled innovative approaches to metabolic engineering, live biotherapeutic development, and biological discovery. As reconstruction methodologies continue to improve and models incorporate additional cellular processes, GEMs will play an increasingly central role in accelerating the design-build-test-learn cycle for developing high-performance microbial strains for industrial and biomedical applications.

In the field of systems biology and metabolic engineering, Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) serve as mathematical representations of the metabolism of archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotic organisms [1]. These models quantitatively define the relationship between an organism's genotype and its metabolic phenotype [1]. A critical component that enables this connection is the Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) association, a logical rule that describes how genes give rise to proteins (enzymes) that subsequently catalyze metabolic reactions [6] [7]. GPR rules use Boolean logic (AND, OR) to represent the complex relationships between genes and the reactions they enable [7]. Essentially, GPRs provide the mechanistic link that allows researchers to predict how genetic perturbations (e.g., gene deletions) will affect metabolic fluxes and, consequently, cellular phenotypes such as growth rate or chemical production [6] [8]. Within the context of GEMs strain design research, accurate GPR rules are indispensable for in silico prediction of optimal genetic modifications that lead to desired industrial or therapeutic outcomes [9] [10].

The Logical Structure and Annotation of GPR Rules

Fundamental Boolean Operators in GPRs

GPR rules structurally describe how gene products concur to catalyze associated metabolic reactions [7]. The AND operator joins genes encoding for different subunits of the same enzyme complex, indicating that all subunits are necessary for the enzyme's function. The OR operator joins genes encoding for distinct protein isoforms that can catalyze the same reaction, indicating functional redundancy [7].

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationship described by GPR rules from genetic information to metabolic function:

Computational Representation of GPRs

For constraint-based modeling and simulation, the Boolean logic of GPRs must be translated into a computational format. A model transformation exists that encodes GPR associations directly into the stoichiometric matrix, changing Boolean gene states (on/off) to a real-valued representation [6]. In this representation, the enzyme (or enzyme subunit) encoded by each gene becomes a species in the model, and the participation of an enzyme in a reaction is encoded by adding the respective pseudo-species to the reaction [6]. This transformation enables existing constraint-based methods to be applied at the gene level, improving biological insight and prediction accuracy [6].

Quantitative Landscape of GPR-Enabled Metabolic Models

Table 1: Current Landscape of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models Incorporating GPR Rules

| Category | Organism Examples | Number of Models | Notable GEM Versions | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Escherichia coli | >6000 total GEMs across all organisms [1] | iML1515 (1515 genes) [10] | Strain development, bioproduction [10] |

| Bacillus subtilis | Not specified | iBsu1144 [10] | Enzyme and protein production [10] | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Not specified | iEK1101 [10] | Drug target discovery [10] | |

| Archaea | Methanosarcina acetivorans | 9 archaeal GEMs total [1] | iMAC868, iST807 [10] | Understanding extreme environment metabolism [10] |

| Eukarya | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 215 eukaryotic GEMs [10] | Yeast 7 [10] | Biofuel and chemical production [10] |

| Homo sapiens | Not specified | Multiple consensus models [10] | Disease modeling, drug development [10] |

Table 2: GPR Rule Topology Statistics in E. coli iAF1260 Model

| Structural Feature | Percentage of Reactions/Enzymes | Maximum Observed | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Complexes | >16% of enzymes [6] | 13 subunits [6] | Multiple genes required for single functional enzyme |

| Isozymes | 31% of reactions [6] | 7 isozymes [6] | Metabolic redundancy and regulatory flexibility |

| Promiscuous Enzymes | 72% of reactions [6] | 250 reactions (4 genes) [6] | Catalytic versatility and metabolic network connectivity |

Protocols for GPR Rule Reconstruction and Integration

Protocol 1: Automated GPR Rule Reconstruction with GPRuler

Purpose: To fully automate the reconstruction of GPR rules for any organism, starting from either just the organism name or an existing metabolic model [7].

Principles: GPRuler is an open-source Python-based framework that mines text and data from nine different biological databases to reconstruct GPR rules [7]. It uniquely exploits the Complex Portal database, which contains information about protein-protein interactions and protein macromolecular complexes established by given genes [7].

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Provide either the name of the target organism or an existing metabolic model in SBML format or as a reaction list.

- Database Querying: The tool automatically queries MetaCyc, KEGG, Rhea, ChEBI, and TCDB databases to retrieve all data regarding the target organism.

- Gene-Reaction Association: Metabolic genes associated with each metabolic reaction are identified through database mining.

- Complex Identification: Protein complex information is extracted from Complex Portal to determine subunit relationships (AND logic).

- Isozyme Identification: Alternative enzymes catalyzing the same reaction are identified (OR logic).

- Rule Assembly: Boolean GPR rules are automatically assembled using AND operators for complex subunits and OR operators for isozymes.

- Output Generation: Final GPR rules are exported in standardized SBML format for compatibility with constraint-based modeling tools.

Validation: Performance evaluation shows GPRuler can reproduce original GPR rules in manually curated models with high accuracy, and in many cases revealed to be more accurate than the original models upon manual investigation [7].

Protocol 2: Multi-Strain GEM Integration for Pan-Metabolic Analysis

Purpose: To create multi-strain GEMs that capture metabolic diversity across different strains of the same species, enabling identification of strain-specific metabolic capabilities [1].

Principles: Pan-genome analysis unravels variability among genomes of multiple strains, resulting in divergent phenotypes across the strains [1]. Based on this concept, GEMs for a single strain can be expanded to create models for multiple strains of the same species using genomics information [1].

Procedure:

- Strain Selection: Collect genome sequences for multiple strains of the target species.

- Individual Reconstruction: Reconstruct separate GEMs for each strain using standardized tools (e.g., CarveMe, ModelSEED, gapseq).

- Core-Pan Analysis: Create a "core" model containing metabolic reactions present in all strains, and a "pan" model containing the union of all metabolic reactions across strains.

- GPR Integration: Incorporate strain-specific GPR rules that reflect genetic variations between strains.

- Phenotype Prediction: Simulate growth capabilities in different environments to identify strain-specific metabolic traits.

Application Example: This approach has been successfully applied to 55 E. coli strains, 410 Salmonella strains, 64 S. aureus strains, and 22 K. pneumoniae strains, providing strain-specific insights at the network level [1].

Protocol 3: Consensus Model Assembly with GEMsembler

Purpose: To compare, combine, and analyze GEMs built with different reconstruction tools, creating consensus models with improved predictive performance [9].

Principles: GEMsembler is a Python package that assembles consensus models from multiple input GEMs by converting model features to a common nomenclature, tracking the origin of each feature, and generating consensus models containing different combinations of input models' features [9].

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Input Collection: Gather GEMs for the same organism reconstructed using different tools (e.g., CarveMe, ModelSEED, gapseq).

- Feature Conversion: Convert metabolite and reaction IDs to BiGG nomenclature using MetaNetX and other mapping resources.

- Gene Mapping: Map genes to a common reference genome using BLAST if different locus tags are used.

- Supermodel Assembly: Combine all converted models into a single supermodel object that tracks the origin of each feature.

- Consensus Generation: Create consensus models with features present in at least X of the input models (e.g., core4 requires feature presence in 4 models).

- GPR Rule Reconciliation: Compare GPR logical expressions from original models to create new consensus GPR rules based on agreement.

- Performance Validation: Test consensus models for improved prediction accuracy in auxotrophy, gene essentiality, and growth simulations.

Validation: GEMsembler-curated consensus models built from four Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Escherichia coli automatically reconstructed models were shown to outperform gold-standard models in auxotrophy and gene essentiality predictions [9].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GPR Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in GPR Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPRuler | Software Tool | Automated GPR rule reconstruction | De novo inference of Boolean GPR rules from genomic data [7] |

| GEMsembler | Software Package | Consensus model assembly | Combining GEMs from different tools; reconciling conflicting GPR rules [9] |

| Complex Portal | Database | Protein complex information | Defining AND relationships in GPR rules based on experimental evidence [7] |

| MetaNetX | Platform | Database namespace mapping | Converting metabolite/reaction identifiers between different GEM formats [9] |

| COBRApy | Software Toolbox | Constraint-based modeling | Simulating GEMs with integrated GPR rules for phenotype prediction [9] |

| BiGG Models | Database | Curated metabolic reconstructions | Reference GPR rules for model validation and comparison [9] |

| MetNetComp | Database | Gene deletion strategies | Repository of growth-coupled strain designs incorporating GPR logic [8] |

Applications in Strain Design and Therapeutic Development

Predicting Growth-Coupled Gene Deletion Strategies

A critical application of GPR rules in strain design is predicting gene deletion strategies that enforce growth-coupled production, where cell growth and target metabolite synthesis occur simultaneously [8]. The GraphGDel framework constructs graph representations from constraint-based metabolic models and uses deep learning to predict effective gene deletion strategies [8]. This approach has demonstrated performance improvements of 14.04%, 16.26%, and 13.18% in overall accuracy across three metabolic models of varying scale [8]. Accurate GPR rules are essential for this application, as they determine which reaction fluxes will be disrupted by specific gene deletions.

Drug Target Identification in Pathogens

GPR-enabled GEMs have been extensively applied to identify potential drug targets in pathogenic microorganisms [1] [10]. For example, GEMs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis have been used to understand the pathogen's metabolic status under in vivo hypoxic conditions and to evaluate metabolic responses to antibiotic pressures [10]. Multi-strain GEMs of ESKAPPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp., and Escherichia coli) have helped identify potential bacterial two-component systems as drug targets [1]. The GPR rules in these models enable researchers to pinpoint essential genes whose inhibition would disrupt critical metabolic functions in pathogens.

Context-Specific Model Construction for Mammalian Systems

GPR rules enable the construction of context-specific models for mammalian cell systems by integrating transcriptomic, proteomic, and other omics data [11]. These models help understand metabolic alterations in human diseases and identify therapeutic targets [10] [11]. The integration of GPR rules with machine learning approaches enhances their predictive capabilities and facilitates knowledge transfer from microbial to mammalian cell systems [1] [11]. This application is particularly valuable for understanding host-pathogen interactions and developing novel antimicrobial strategies [10].

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have emerged as powerful computational frameworks for understanding cellular metabolism at a systems level. These models represent complex metabolic networks through mathematical representations that connect genomic information to phenotypic behaviors [1]. Constraint-based modeling, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), serves as the principal methodology for simulating metabolic fluxes in GEMs, enabling quantitative predictions of organism behavior under various genetic and environmental conditions [12] [13]. The mathematical backbone of FBA revolves around the stoichiometric matrix, which encodes the fundamental biochemical relationships within metabolic networks. For strain design research, FBA provides an indispensable tool for predicting how genetic modifications will alter metabolic fluxes to achieve desired phenotypes, such as enhanced production of valuable biochemicals or improved growth characteristics [14] [3]. This protocol outlines the fundamental mathematical principles, practical implementation, and advanced applications of FBA within the context of GEM-driven strain design.

Mathematical Foundations: The Stoichiometric Matrix

Structural and Functional Principles

The stoichiometric matrix (S) forms the core mathematical structure of any metabolic model. This m × n matrix quantitatively represents the metabolic network, where m corresponds to the number of metabolites and n to the number of biochemical reactions [12]. Each element Sᵢⱼ within the matrix denotes the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. The sign convention follows: Sᵢⱼ < 0 indicates that metabolite i is consumed (substrate) in reaction j, while Sᵢⱼ > 0 indicates that metabolite i is produced (product) [12].

The stoichiometric matrix enables mass-balance analysis through the fundamental equation:

S ⋅ v = 0

where v is an n-dimensional vector of reaction fluxes [13]. This equation formalizes the assumption of steady-state metabolism, where the production and consumption of each intracellular metabolite are perfectly balanced, and no net accumulation occurs [12] [13]. This steady-state assumption is valid when modeling exponential growth phases in microorganisms.

Constraints and Solution Spaces

The mass-balance constraints defined by the stoichiometric matrix create a solution space containing all possible flux distributions that satisfy the steady-state condition. However, this space is typically underdetermined, as most metabolic networks contain more reactions than metabolites (n > m) [12]. To narrow the solution space, FBA incorporates additional constraints:

- Capacity constraints: Upper and lower bounds (lb ≤ v ≤ ub) on reaction fluxes represent thermodynamic irreversibility, enzyme capacity, or substrate uptake rates [13].

- Environmental constraints: Exchange reactions with the environment are bounded to reflect nutrient availability.

- Objective function: A linear objective function (Z = cᵀv) is defined to identify a single optimal flux distribution from the solution space, typically maximizing biomass production or synthesizing a target metabolite [14] [13].

Table 1: Key Components of the Stoichiometric Matrix in Metabolic Modeling

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation | Role in FBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | m × n matrix | Network topology of metabolic reactions | Defines mass-balance constraints |

| Flux Vector (v) | n-dimensional vector | Rates of metabolic reactions | Variables to be optimized |

| Mass Balance | S⋅v = 0 | Steady-state metabolite concentrations | Eliminates thermodynamically infeasible solutions |

| Flux Bounds | lb ≤ v ≤ ub | Thermodynamic and enzyme capacity limits | Narrows solution space based on physiological constraints |

| Objective Function | Z = cᵀv | Biological objective (e.g., growth) | Identifies optimal flux distribution |

Computational Implementation of FBA

Core Algorithm and Optimization

The complete FBA algorithm can be formalized as a linear programming problem:

Maximize: Z = cᵀv Subject to: S⋅v = 0 and: lb ≤ v ≤ ub

where c is a vector of coefficients defining the biological objective [13]. In practice, the biomass objective function is often represented as a pseudo-reaction that consumes all necessary biomass precursors (amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, etc.) in their appropriate physiological ratios [12].

Table 2: Common Objective Functions in FBA for Strain Design

| Objective Function | Application Context | Typical Use Case | Example Strain Design Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Maximization | Wild-type phenotype prediction | Base case simulation | Reference growth rate determination |

| Product Maximization | Metabolic engineering | Chemical production | Maximize target metabolite yield |

| ATP Maximization | Energy metabolism studies | Maintenance energy estimation | Analyze metabolic energy efficiency |

| Substrate Minimization | Cost-effective bioprocessing | Yield optimization | Reduce nutrient costs for equivalent product output |

| Non-Growth Associated | Two-stage bioprocessing | Production phase simulation | Decouple growth from production phases |

Protocol: Basic FBA Implementation for Strain Design

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Genome-scale metabolic model (JSON/SBML format)

- Computational environment (Python/COBRApy, MATLAB/COBRA Toolbox)

- Linear programming solver (GLPK, CPLEX, Gurobi)

- Optional visualization tools (Escher-FBA [15])

Procedure:

- Model Import and Validation:

Environmental Constraints Specification:

- Define medium composition by setting bounds on exchange reactions

- Set lower bounds of nutrient uptake reactions to negative values (e.g., glucose uptake: -10 mmol/gDW/hr)

- Constrain oxygen uptake for aerobic/anaerobic conditions (e.g., EXo2e: 0 for anaerobic)

- Block uptake of metabolites not present in the medium [14]

Genetic Constraints Implementation:

- Simulate gene knockouts by setting upper and lower bounds of associated reactions to zero

- Implement gene knock-ins by adding new reactions or modifying existing reaction bounds

- Adjust enzyme constraints using workflows like ECMpy to incorporate catalytic constants [14]

Objective Function Definition:

- Set objective reaction (typically biomass for growth simulations)

- For production strains, implement lexicographic optimization: first maximize growth, then constrain growth to a percentage of maximum while maximizing product formation [14]

Problem Solution and Analysis:

- Execute FBA simulation to obtain optimal flux distribution

- Validate growth rate predictions against experimental data

- Analyze flux distributions to identify key pathway usage

- Perform flux variability analysis (FVA) to identify alternate optimal solutions

Figure 1: FBA Workflow for Strain Design. This diagram illustrates the sequential steps for implementing Flux Balance Analysis in metabolic engineering applications.

Advanced FBA Methodologies for Enhanced Prediction

Incorporating Enzyme Constraints

Basic FBA often predicts unrealistically high metabolic fluxes. Enzyme-constrained FBA (ecFBA) addresses this limitation by incorporating proteomic constraints:

- kcat Values: Implement enzyme turnover numbers to constrain flux by catalytic capacity

- Enzyme Mass Balance: Include enzyme synthesis and degradation reactions

- Protein Allocation: Constrain total cellular protein content [14]

The ECMpy workflow provides a standardized approach for integrating enzyme constraints into existing GEMs by splitting reversible reactions, assigning kcat values from databases like BRENDA, and incorporating molecular weights from sources such as EcoCyc [14].

Hybrid Neural-Mechanistic Modeling

Recent advances integrate machine learning with FBA to improve predictive accuracy. NEXT-FBA (Neural-net EXtracellular Trained Flux Balance Analysis) represents a novel hybrid approach that:

- Trains artificial neural networks (ANNs) with exometabolomic data

- Correlates extracellular metabolite measurements with intracellular fluxomic data

- Predicts bounds for intracellular reaction fluxes to constrain GEMs [16]

Similarly, Artificial Metabolic Networks (AMNs) embed FBA within neural networks, enabling gradient backpropagation and enhanced learning from experimental data [17]. These approaches address the critical limitation of converting extracellular concentrations to intracellular uptake fluxes, improving quantitative phenotype predictions while requiring smaller training datasets than classical machine learning methods [17].

Figure 2: NEXT-FBA Hybrid Architecture. This diagram shows the integration of neural networks with constraint-based modeling to improve flux prediction accuracy.

Protocol: Implementing Enzyme-Constrained FBA

Materials:

- Base GEM (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli [14])

- Enzyme kinetic database (BRENDA [14])

- Protein abundance data (PAXdb [14])

- Molecular weights and subunit composition (EcoCyc [14])

- ECMpy Python package [14]

Procedure:

- Reaction Processing:

- Split reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions

- Separate reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into independent reactions

- Assign kcat values for each reaction direction from BRENDA

Enzyme Constraint Implementation:

- Calculate molecular weights of enzyme subunits

- Set the total protein fraction constraint (typically ~0.56 g protein/g biomass [14])

- Incorporate enzyme mass balance constraints

Strain-Specific Modifications:

- Modify kcat values to reflect engineered enzyme kinetics

- Adjust gene abundance values based on promoter strength and copy number

- Implement additional constraints for transport reactions when data available

Simulation and Validation:

- Perform ecFBA simulations with biomass or product formation objectives

- Compare predictions with basic FBA results

- Validate against experimental growth rates and metabolite production data

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for FBA Implementation

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in FBA | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEM Databases | Data Resource | Provides curated metabolic networks | BiGG Models [15], AGORA2 [3] |

| Enzyme Kinetics | Data Resource | kcat values for enzyme constraints | BRENDA [14] |

| Protein Abundance | Data Resource | Proteomic constraints for ecFBA | PAXdb [14] |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software | MATLAB-based FBA implementation | [15] |

| COBRApy | Software | Python-based FBA implementation | [14] [15] |

| Escher-FBA | Software | Web-based interactive FBA visualization | [15] |

| GLPK | Solver | Linear programming optimization | [15] |

Applications in Strain Design and Therapeutic Development

Metabolic Engineering for Bioproduction

FBA has proven instrumental in strain design for biochemical production. A representative case study demonstrates FBA-guided engineering of E. coli for L-cysteine overproduction:

- Model Modifications: The iML1515 GEM was updated with modified kinetic parameters for SerA, CysE, and EamB enzymes to reflect engineered activity [14]

- Pathway Incorporation: Gap-filling methods added missing thiosulfate assimilation pathways for L-cysteine production [14]

- Medium Optimization: Uptake bounds were adjusted to reflect SM1 + LB medium composition with thiosulfate supplementation [14]

- Lexicographic Optimization: The model was first optimized for biomass, then constrained to 30% of maximum growth while maximizing L-cysteine export [14]

This systematic approach enabled identification of optimal flux distributions and key metabolic shifts necessary for enhanced production.

Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) Development

FBA and GEMs are increasingly applied in developing live biotherapeutic products. The AGORA2 resource, containing 7,302 curated GEMs of gut microbes, enables:

- Strain Screening: Identification of therapeutic candidates based on metabolic capabilities

- Interaction Analysis: Prediction of synergistic or antagonistic relationships in microbial communities

- Personalized Formulations: Design of multi-strain consortia based on individual microbiome composition [3]

For example, GEMs have been used to identify bifidobacteria strains antagonistic to pathogenic E. coli through pairwise growth simulations, selecting Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium animalis as promising candidates for colitis alleviation [3].

Protocol: Multi-Strain Community Modeling for LBP Design

Materials:

- AGORA2 database or similar resource of curated GEMs

- Metagenomic data from target population (optional)

- Metabolic objectives for desired therapeutic effect

Procedure:

- Therapeutic Objective Definition:

- Identify target metabolic functions (e.g., SCFA production, pathogen inhibition)

- Define desired interaction profiles with resident microbiome

Candidate Strain Selection:

- Screen GEM database for strains with required metabolic capabilities

- Perform pairwise interaction simulations to identify synergistic combinations

- Eliminate strains with potential safety concerns (pathogenic metabolites, antibiotic resistance)

Community Modeling:

- Construct community GEM incorporating selected strains

- Simulate metabolic cross-feeding and competition

- Optimize strain ratios for community stability and function

Validation and Refinement:

- Compare predictions with in vitro culturing results

- Refine model parameters based on experimental data

- Iterate strain selection and formulation

Limitations and Future Directions

While FBA provides a powerful framework for metabolic modeling, several limitations remain. Key challenges include:

- Uncertainty in Model Reconstruction: Annotation errors, incomplete pathway knowledge, and transport reaction ambiguities introduce uncertainty [18]

- Regulatory Oversimplification: Basic FBA ignores transcriptional, translational, and post-translational regulation [13]

- Condition-Specific Parameters: Difficulty in determining environment-specific flux bounds [17]

Emerging approaches address these limitations through:

- Probabilistic Annotation: Methods like ProbAnnoPy incorporate uncertainty in functional annotation [18]

- Integrated Regulatory Modeling: Methods like rFBA, iFBA, and TRFBA incorporate transcriptional regulatory networks [13]

- Hybrid Neural-Mechanistic Modeling: NEXT-FBA and AMNs improve prediction accuracy through machine learning [16] [17]

Future development will focus on comprehensive integration of multi-omics data, dynamic regulation, and multi-scale modeling to enhance the predictive power of FBA in strain design and therapeutic applications.

In the context of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), objective functions represent mathematical representations of cellular goals that drive computational predictions of metabolic behavior. GEMs provide a structured, mathematical representation of an organism's metabolic network, encompassing the complete set of metabolic reactions, associated genes, and enzymes [19]. Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods utilize these networks to place biological constraints on intracellular fluxes, with flux balance analysis (FBA) serving as a cornerstone technique that assumes metabolite concentrations reach a pseudo steady-state compared to substrate uptake and cell division timescales [20].

The fundamental principle behind objective functions lies in their ability to resolve the underdetermined nature of metabolic networks, where mass balance constraints alone are insufficient to determine unique flux distributions. By assuming a cellular objective—typically biomass maximization for microbial growth—FBA can predict unique flux vectors that correspond to physiological states [20]. The accuracy of these predicted flux values depends significantly on the objective function selected, with some functions demonstrating strong correlation with experimental omics data [20]. This framework enables researchers to simulate metabolic fluxes, identify bottlenecks, and predict genetic interventions to enhance biosynthesis of target compounds, thereby reducing experimental trial-and-error in strain design [21].

Theoretical Foundations: Classes of Objective Functions

Biomass Maximization and Product Synthesis

The most prevalent objective function in microbial GEMs maximizes biomass production, representing cellular growth as the primary evolutionary objective. This biomass objective function typically incorporates biosynthetic demands for all biomass constituents, including amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, and cofactors, weighted according to their cellular abundance [22]. For industrial applications where metabolite production rather than growth is desired, alternative objective functions directly maximize the synthesis rate of target biochemicals. This creates inherent competition between biomass and product formation, necessitating specialized modeling approaches to balance these objectives [23].

Enzymatic and Resource Allocation Constraints

Recent extensions to traditional FBA incorporate enzymatic constraints to address limitations of biomass-maximization assumptions. The GECKO (Enhancement of GEMs with Enzymatic Constraints using Kinetic and Omics data) toolbox enhances GEMs by incorporating enzyme demands for metabolic reactions, accounting for isoenzymes, promiscuous enzymes, and enzymatic complexes [24]. This approach enables more realistic predictions by constraining reaction fluxes based on measured enzyme kinetics and proteomic limitations, explaining phenomena like overflow metabolism in E. coli and S. cerevisiae [24]. Metabolism and gene-expression models (ME-models) further extend this framework by explicitly modeling reactions involved in transcription and translation, building quantitative models of enzyme production and usage [20].

Table 1: Major Classes of Objective Functions in GEMs

| Objective Class | Mathematical Principle | Primary Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Maximization | Maximizes synthesis of biomass components | Simulation of native growth phenotypes | Strong correlation with experimental growth data |

| Product Maximization | Maximizes flux to target metabolite | Strain design for bioproduction | Direct optimization of industrial objectives |

| Enzyme-Limited | Incorporates kcat and enzyme capacity constraints | Prediction of overflow metabolism; proteome allocation | Explains suboptimal growth phenotypes |

| Multi-Objective | Balances competing cellular goals | Analysis of trade-offs between growth and production | Identifies Pareto-optimal strain designs |

Computational Protocols for Strain Design

Flux Balance Analysis with Modified Objectives

The standard FBA framework formulates metabolic flux prediction as a linear programming problem:

Maximize: ( Z = c^{T}v ) Subject to: ( S \cdot v = 0 ) ( v{min} \leq v \leq v{max} )

Where ( c ) is a vector of coefficients weighting reaction contributions to the cellular objective, ( v ) represents flux vectors, and ( S ) is the stoichiometric matrix [25]. For product maximization, ( c ) is defined with a weight of 1 for the output exchange reaction of the target metabolite and 0 for biomass. In practice, this often requires additional constraints to ensure minimal growth, typically implemented through bilevel optimization frameworks like OptKnock that simultaneously optimize for product secretion and biomass formation [23].

Protocol: Implementing Product-Maximizing FBA

- Obtain a validated GEM for your target organism in SBML format

- Define the target product exchange reaction as the objective function

- Constrain substrate uptake rates based on experimental measurements

- Set lower bound for biomass reaction to ensure viability (typically 5-10% of maximum)

- Solve the linear programming problem using COBRA Toolbox or COBRApy

- Validate flux predictions against known metabolic capabilities

Incorporating Kinetic and Omics Constraints

The GECKO methodology enhances GEMs with enzymatic constraints through a systematic protocol. This approach expands the metabolic model to include pseudo-reactions that represent enzyme usage, with constraints derived from enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat values) and total protein mass availability [24]. The parameterization procedure automatically retrieves kinetic parameters from the BRENDA database, implementing hierarchical matching criteria that prioritize organism-specific measurements before incorporating orthologous data [24].

Protocol: Building Enzyme-Constrained GEMs with GECKO 2.0

- Start with a high-quality, manually curated GEM

- Run the

gecko2function to automatically add enzyme constraints - Incorporate proteomics data (if available) to constrain individual enzyme usage

- For reactions without specific kcat values, apply the hierarchical matching algorithm:

- First priority: Organism-specific kcat for the exact enzyme

- Second priority: kcat from closely related species

- Third priority: kcat from any organism for the same EC number

- Final fallback: Apply the database median kcat value

- Constrain the pool of available enzyme based on measured protein content

- Validate model predictions against chemostat data across multiple growth rates

Hybrid Cybernetic Modeling for Dynamic Simulations

The hybrid cybernetic model (HCM) approach integrates enzyme synthesis and activity regulation with metabolic network decomposition. For genome-scale applications, the opt-yield-FBA algorithm calculates optimal yield solutions and yield spaces without the computational burden of elementary flux mode calculation [26]. This enables dynamic modeling of metabolic adaptation to changing substrate conditions, particularly useful for simulating microbial communities and sequential substrate utilization [26].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Hybrid Cybernetic Modeling with opt-yield-FBA

Experimental Workflow for Model-Driven Strain Design

The complete workflow for metabolic model-guided strain design follows a systematic Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, integrating computational predictions with experimental validation [20]. This framework takes advantage of improvements in genetic engineering and high-throughput characterization to efficiently screen libraries of strain modifications.

Diagram 2: Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle for Strain Engineering

Multi-Omics Integration for Model Refinement

Constraint-based methods have expanded to incorporate diverse omics datasets for improved phenotype prediction. Transcriptomic data can block flux through reactions where essential enzyme gene expression is absent [20]. Proteomic data integration through ME-models or GECKO enables direct comparison with protein expression measurements [20] [24]. Metabolomics data incorporate through thermodynamic constraints, with absolute metabolite concentrations enabling thermodynamic metabolic flux analysis to identify irreversible reactions under specific conditions [20].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration in GEMs

| Data Type | Integration Method | Constraint Implementation | Impact on Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics | Gene-protein-reaction rules | Boolean on/off flux constraints | Improved context-specificity |

| Proteomics | Enzyme usage pseudo-reactions | Upper bounds on reaction fluxes | Enhanced prediction of overflow metabolism |

| Metabolomics | Thermodynamic analysis | Directionality constraints on reactions | More accurate flux direction prediction |

| Fluxomics | 13C labeling data | Additional flux constraints | Reduced solution space |

Case Study: Succinic Acid Production in Yarrowia lipolytica

A recent application demonstrating the power of objective function manipulation for bioproduction focused on succinic acid (SA) production in Yarrowia lipolytica [21]. Researchers reconstructed a GEM of the industrially relevant W29 strain, comprising 634 genes, 1130 metabolites, and 1364 reactions across eight cellular compartments. The model achieved 88.9% accuracy in predicting growth phenotypes on 18 carbon sources and demonstrated strong correlation with experimental growth rates (R² = 0.98) [21].

Implementation of Production-Oriented Objectives

For succinic acid overproduction, the objective function was modified to maximize flux through the SA exchange reaction while maintaining a minimum growth rate constraint. In silico strain design algorithms identified key genetic interventions:

- Knockout of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) to prevent SA degradation

- Knockout of acetyl-CoA hydrolase (ACH) to reduce acetate co-production

- Overexpression of pyruvate carboxylase to enhance oxaloacetate supply

- Overexpression of TCA/glyoxylate cycle enzymes to redirect carbon flux

Simulations predicted that these interventions would increase SA flux to 4.36 mmol/gDW/h (0.56 g/g glycerol), aligning with prior experimental observations [21]. The model further predicted that overexpression of anaplerotic and TCA cycle enzymes could enhance SA yields by up to 186%, providing specific targets for future strain engineering.

Experimental Validation

Model predictions were validated through construction of engineered strains, demonstrating the practical utility of model-guided objective function optimization. The close alignment between predicted and experimental results confirmed the GEM as a robust platform for rational strain design, not only for succinic acid but potentially for other bio-based chemicals [21].

Table 3: Computational Tools for Objective Function Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling | FBA, gene knockout simulations, pathway analysis |

| GECKO Toolbox | Enhancement of GEMs with enzymatic constraints | Incorporation of kcat values and proteomics data |

| CarveMe | Automated GEM reconstruction from genome annotations | Rapid draft model generation for novel organisms |

| optFlux | Metabolic engineering workbench with strain design algorithms | OptKnock and other bilevel optimization implementations |

| BRENDA Database | Comprehensive enzyme kinetic parameter repository | kcat value retrieval for enzyme constraints |

| BiGG Models | Curated multiorganism GEM database | High-quality template models for reconstruction |

Objective functions serve as the computational embodiment of cellular goals in genome-scale metabolic modeling, enabling prediction of metabolic behaviors under genetic and environmental perturbations. While biomass maximization remains the standard for simulating native growth phenotypes, product-oriented objective functions have proven invaluable for metabolic engineering applications. Recent advances incorporating enzymatic constraints and multi-omics data have significantly improved model predictive accuracy, moving beyond purely optimality-based assumptions to capture more nuanced cellular behaviors.

Future developments in objective function design will likely focus on dynamic multi-objective optimization that better represents the competing demands faced by industrial production strains. Integration of machine learning approaches with constraint-based models may enable more sophisticated objective functions that adapt based on multi-omics patterns. As the field progresses, standardized protocols for objective function selection and validation will be essential for maximizing the translational impact of GEMs in biotechnology and therapeutic development.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are comprehensive computational reconstructions of the metabolic network of an organism, representing biochemical transformations as a stoichiometric matrix of reactions [27]. These models encapsulate the totality of metabolic functions for a given organism and serve as structured knowledge-bases that abstract pertinent information on biochemical transformations [28]. Traditional GEMs have typically focused on single reference strains, limiting their ability to represent the metabolic diversity present within bacterial species. Pan-genome-scale metabolic modeling addresses this limitation by expanding metabolic reconstructions to represent multiple strains simultaneously, capturing both core metabolic functions shared across strains and accessory functions present in subsets of strains [29].

The genetic diversity within bacterial species can be substantial, leading to ecological niche separation and differences in virulence and antimicrobial susceptibility [27]. Pan-genome models provide a framework for studying this diversity by representing the total gene and reaction repertoire of a species, comprising core components present in virtually all strains and accessory components with variable presence [29]. This approach enables comparative analysis of strain-to-strain differences related to nutrient utilization, fermentation outputs, robustness, and other metabolic aspects that are crucial for both basic science and industrial applications [29].

Construction of Pan-Genome Metabolic Models

Methodological Framework

The construction of pan-genome metabolic models follows a systematic protocol that expands upon established methods for single-strain GEM reconstruction [28]. The general workflow encompasses several stages, beginning with genomic data collection and progressing through model refinement and validation:

Computational Tools and Platforms

Several computational tools have been developed to facilitate the construction of pan-genome metabolic models, each with distinct approaches and advantages:

Table 1: Computational Tools for Pan-Genome Metabolic Model Construction

| Tool | Approach | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| pan-Draft [30] | Pan-reactome-based leveraging genetic evidence | Uses minimum reaction frequency threshold; integrated into gapseq pipeline | Species-representative model reconstruction from MAGs |

| Bactabolize [27] | Reference-based reconstruction | Leverages COBRApy framework and BiGG nomenclature; rapid model generation (<3 minutes/genome) | High-throughput strain-specific model generation |

| createPanModels [30] | Homology-driven from reference | Part of Microbiome Modeling Toolbox 2.0; limited to AGORA collection | Pan-model reconstruction from complete genomes |

| MIGRENE Toolbox [30] | Reference-based from generalized model | Creates reaction profiles using gene presence/absence | Species-level GEMs from pan-genomes |

Quality Control and Validation

Implementing robust quality control measures is essential when building pan-genome models, particularly when working with metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) that may suffer from incompleteness and contamination [30]. The minimum reaction frequency (MRF) threshold approach helps determine the solid core structure of species-level GEMs by exploiting recurrent genetic evidence across multiple genomes [30]. For experimental validation, Biolog Phenotype Microarray systems can be used to test carbon utilization and other growth phenotypes, providing empirical data to refine and validate metabolic predictions [29].

Case Studies and Applications

Bacillus subtilis Pan-Model

A notable example of pan-genome metabolic modeling is the reconstruction for Bacillus subtilis, which expanded previous single-strain models to represent 481 strains [29]. This comprehensive model encompasses 2,315 orthologous gene clusters, 1,874 metabolites, and 2,239 reactions,

representing a significant increase in coverage compared to earlier reconstructions. The B. subtilis pan-genome analysis revealed that while the overall pan-genome contained 20,315 gene families, only 2,367 (11.7%) constituted the core genome present in >99% of strains [29].

Table 2: Statistics of Bacillus subtilis Pan-Genome Metabolic Model

| Feature | Pan-Model | Core (≥99%) | Accessory (<99%) | Average Strain Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactions | 2,239 | 2,067 (92.3%) | 172 (7.7%) | 2,175 (±12) |

| Metabolic Reactions | 1,568 | 1,386 (88.4%) | 182 (11.6%) | 1,514 (±11) |

| Transport Reactions | 321 | 273 (85.0%) | 48 (15.0%) | 310 (±3) |

| Gene Clusters | 2,315 | 697 (30.1%) | 1,618 (69.9%) | 1,108 (±13) |

| Metabolites | 1,847 | 1,741 (94.3%) | 106 (5.7%) | 1,808 (±6) |

Through unsupervised machine learning analysis of metabolic capabilities, the B. subtilis strains could be divided into five distinct groups with unique patterns of metabolic behavior, enabling rapid classification of individual strains and identification of suitable candidates for specific applications [29].

Klebsiella pneumoniae Species Complex

For the priority antimicrobial-resistant pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae, a pan-metabolic reference model was developed from 37 curated strain-specific models [27]. The Bactabolize tool was subsequently created to rapidly generate strain-specific draft models using this pan-reference, demonstrating superior performance compared to other automated approaches across 507 substrate and 2,317 knockout mutant growth predictions [27]. When applied to novel draft genomes passing quality control criteria, Bactabolize generated models with high completeness (≥99% genes and reactions captured compared to models from complete genomes) and high accuracy (mean 0.97) [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Pan-Genome Model Reconstruction

Materials:

- Genomic sequences for multiple strains of target species

- High-performance computing infrastructure

- Biochemical databases (KEGG, BRENDA, ModelSEED)

- Metabolic modeling software (COBRA Toolbox, CellNetAnalyzer)

- Phenotypic validation data (Biolog arrays, growth assays)

Procedure:

Genome Acquisition and Curation

- Collect high-quality genome sequences for multiple strains of the target organism

- Filter genomes based on completeness and contamination estimates using tools like CheckM

- Perform functional annotation using standardized pipelines (e.g., Prokka, RAST)

Orthologous Gene Clustering

- Cluster protein sequences into orthologous groups using tools such as OrthoFinder or PanTools

- Apply a core gene threshold (typically 95-99% of strains) to define core versus accessory genome

- Construct a pan-genome matrix tracking gene presence/absence across strains

Draft Model Reconstruction

- Convert the pan-genome matrix into a pan-reactome using gene-protein-reaction rules

- For each strain, create a draft model containing reactions associated with present genes

- Apply a minimum reaction frequency threshold to define the core reactome

Network Refinement and Gap Filling

- Identify metabolic gaps preventing growth in known conditions

- Iteratively add reactions from the pan-reactome to fill gaps while minimizing additions

- Validate reaction directionality and network connectivity

Model Validation and Testing

- Compare simulated growth phenotypes with experimental data

- Test accuracy of substrate utilization predictions

- Validate essential gene predictions against experimental mutant libraries

Protocol for Strain Classification Based on Metabolic Features

Materials:

- Constrained pan-genome metabolic models for multiple strains

- Phenotypic data (carbon sources, growth rates, metabolic products)

- Statistical computing environment (R, Python)

- Machine learning libraries (scikit-learn, FactoMineR)

Procedure:

Phenotype Simulation

- For each strain model, simulate growth across a defined set of environmental conditions

- Calculate growth rates or binary growth outcomes for each condition

- Generate a metabolic phenotype matrix (strains × conditions)

Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction

- Identify metabolic features with high variability across strains

- Apply principal component analysis to reduce dimensionality

- Select top components that explain majority of variance

Clustering and Group Identification

- Apply clustering algorithms (k-means, hierarchical clustering) to metabolic phenotypes

- Determine optimal number of clusters using silhouette scores or gap statistic

- Assign strains to metabolic groups based on cluster membership

Group Characterization and Validation

- Identify defining metabolic characteristics of each group

- Validate group assignments with experimental data

- Correlate metabolic groups with ecological origins or phenotypic traits

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pan-Genome Metabolic Modeling

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [28] | Software Suite | MATLAB-based tools for constraint-based modeling | Open source |

| CarveMe [27] | Software Tool | Automated metabolic model reconstruction from genome annotations | Open source |

| gapseq [30] [27] | Software Tool | Automated metabolic model reconstruction with pan-Draft integration | Open source |

| Biolog Phenotype MicroArrays [29] | Experimental Platform | High-throughput phenotypic profiling of carbon and nitrogen sources | Commercial |

| BiGG Models [27] | Knowledgebase | Curated metabolic models with standardized nomenclature | Open access |

| KEGG [28] | Database | Reference pathways and reaction information | Mixed access |

| BRENDA [28] | Database | Comprehensive enzyme information | Mixed access |

| AGORA [30] | Model Collection | Curated metabolic models of gut microorganisms | Open access |

Pan-genome-scale metabolic modeling represents a significant advancement in systems biology, enabling researchers to move beyond single reference strains to capture the full metabolic diversity within bacterial species. By integrating genomic data from hundreds of strains, these models provide insights into niche adaptation, metabolic specialization, and strain-specific capabilities with implications for biotechnology, medicine, and fundamental microbiology. The continued development of computational tools like pan-Draft and Bactabolize is making pan-genome modeling increasingly accessible, promising to expand our understanding of microbial metabolism across diverse environments and applications.

Methodologies and Practical Applications in Strain Engineering and Drug Development

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational frameworks that mathematically represent the metabolic network of an organism, enabling the simulation of metabolic fluxes under given constraints [31]. Classical constraint-based methods, such as Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), rely primarily on stoichiometric constraints and mass-balance assumptions to predict flux distributions that optimize a biological objective, such as biomass production [14] [32]. However, these methods often predict physiologically unrealistic fluxes because they do not account for fundamental biological limitations. The integration of thermodynamic constraints, which ensure reactions proceed in energetically favorable directions, and enzyme constraints, which account for the finite catalytic capacity and availability of enzymes, addresses these limitations. By incorporating these additional layers, GEMs achieve significantly improved predictive accuracy and provide more physiologically realistic strategies for metabolic engineering and strain design [33] [34].

Quantitative Improvements from Constraint Integration

The systematic incorporation of thermodynamic and enzyme constraints leads to substantial, quantifiable improvements in model predictions. The ET-OptME framework, which integrates both types of constraints, demonstrates a marked increase in predictive performance compared to traditional methods.

Table 1: Quantitative Improvement in Predictive Performance with ET-OptME

| Comparison Method | Increase in Minimal Precision | Increase in Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Stoichiometric Methods (e.g., OptForce, FSEOF) | At least 292% | At least 106% |

| Thermodynamic-Constrained Methods | At least 161% | At least 97% |

| Enzyme-Constrained Algorithms | At least 70% | At least 47% |

Source: Adapted from [33]

These performance metrics, validated for product targets in Corynebacterium glutamicum, highlight how layered constraints narrow the solution space to eliminate thermodynamically infeasible and enzymatically unsustainable flux distributions, yielding more reliable and precise intervention strategies [33].

Protocols for Integrating Constraints

Protocol 1: Integrating Thermodynamic Constraints

This protocol outlines the procedure for incorporating thermodynamic constraints into a GEM to eliminate thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs), which are sets of reactions that can carry flux without a net change in metabolites, violating the second law of thermodynamics [34].

- Step 1: Identify Thermally Infeasible Cycles (TICs). Utilize an algorithm such as ThermOptEnumerator to efficiently scan the stoichiometric matrix (S) of the model and enumerate all TICs. This tool leverages network topology and does not require prior experimental Gibbs free energy data, offering a significant reduction in computational time compared to earlier methods [34].

- Step 2: Determine Reaction Directionality. Based on the identified TICs, assign thermodynamically feasible directions to the involved reactions. This step involves constraining reversible reactions to proceed only in the direction that results in a negative Gibbs free energy change under physiological conditions.

- Step 3: Identify Blocked Reactions. Apply a method like ThermOptCC to pinpoint reactions that are blocked due to thermodynamic infeasibility or network topology. These reactions cannot carry any flux under the defined constraints and can be removed to refine the model.

- Step 4: Construct a Context-Specific Model (CSM). When building a condition-specific model using transcriptomic data, employ a thermodynamically-aware algorithm such as ThermOptiCS. This ensures that the resulting CSM is not only consistent with omics data but is also thermodynamically feasible and compact, containing fewer TICs than models built with conventional methods like Fastcore [34].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps and tools for integrating thermodynamic constraints:

Protocol 2: Integrating Enzyme Constraints

This protocol describes the process of constraining metabolic fluxes based on enzyme kinetics and abundance, ensuring that predicted fluxes do not exceed the catalytic capacity of the available enzyme pool [14].

- Step 1: Prepare the Metabolic Model. Begin with a high-quality, curated GEM. Modify the model to support enzyme constraints by splitting all reversible reactions into separate forward and reverse reactions to assign distinct turnover numbers (Kcat values). Similarly, split reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into independent reactions [14].

- Step 2: Curbate Kinetic and Abundance Data. Collect enzyme kinetic parameters, primarily Kcat values (turnover numbers), from databases such as BRENDA. Obtain protein abundance data for the organism from resources like PAXdb. The molecular weight of enzyme complexes can be calculated from subunit composition using databases like EcoCyc [14].

- Step 3: Incorporate Genetic Modifications. To model engineered strains, modify the relevant parameters. For instance, to reflect removed feedback inhibition, increase the Kcat value for the target reaction. To model enhanced gene expression from a stronger promoter, increase the corresponding gene's abundance value in the model [14].

- Step 4: Apply the Enzyme Capacity Constraint. Implement a global constraint on the total flux through all reactions, weighted by the enzyme's molecular weight and Kcat value, not to exceed the cell's total proteomic budget allocated to metabolism. This can be achieved using tools like ECMpy, which adds this constraint without altering the GEM's stoichiometric matrix [14].

The workflow for implementing enzyme constraints is highly dependent on the accurate curation and modification of model parameters, as shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the above protocols relies on a suite of computational tools, databases, and software packages.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Constraint-Based Modeling

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| ThermOptCOBRA [34] | Software Suite | Detects TICs and ensures thermodynamic feasibility. | Core of Protocol 1. |

| ET-OptME [33] | Algorithmic Framework | Integrates both enzyme efficiency and thermodynamic constraints. | For combined constraint analysis. |

| ECMpy [14] | Python Package | Adds enzyme usage constraints to GEMs. | Core of Protocol 2. |

| COBRA Toolbox [14] [34] | Software Suite | Provides the core environment for constraint-based modeling and analysis. | Running FBA, FVA, and integrating tools. |

| BRENDA [14] | Database | Repository of enzyme kinetic parameters (Kcat). | Sourcing Kcat values in Protocol 2. |

| PAXdb [14] | Database | Provides protein abundance data for multiple organisms. | Sourcing enzyme abundance data in Protocol 2. |

| EcoCyc [14] | Database | Curated database of E. coli genes and metabolism. | Verifying GPR rules and subunit composition. |

| AGORA / BiGG [32] [35] | Database | Repository of high-quality, curated GEMs. | Sourcing and validating base metabolic models. |

Application in Strain Design and Future Directions

The integration of thermodynamic and enzymatic constraints is transforming strain design for industrial biotechnology. For example, enzyme-constrained models have been used to predict optimal gene knockout and up-regulation targets for overproduction in yeasts and bacteria, leading to more robust and viable engineering strategies [33] [36]. Furthermore, these advanced models are critical for designing efficient microbial cell factories for sustainable biofuel production, such as bioethanol and biodiesel, by providing realistic blueprints for redirecting metabolic flux [37].

Future development lies in the creation of multi-scale models that seamlessly integrate these constraints with other cellular processes. This includes models that combine metabolism with gene expression (ME-models), and the application of artificial intelligence to automate the discovery of enzymatic properties and optimize strain design pipelines [37] [36]. As the field moves toward modeling complex host-microbe and microbial community interactions, the principles of thermodynamic and enzymatic constraint integration will be foundational for generating biologically meaningful simulations [32] [35].

In the field of systems biology and therapeutic development, the precise identification of essential genes and drug targets is paramount. Gene knockout strategies, particularly those powered by CRISPR-Cas9 systems, have revolutionized functional genomics by enabling systematic investigation of gene functions [38]. When integrated with genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), these approaches provide a powerful framework for predicting genetic vulnerabilities and mechanisms of action (MOA) driving drug efficacy [39] [3]. GEMs are computational representations of the complete metabolic network of an organism, based on its annotated genome [40]. They allow for the simulation of metabolic fluxes under different genetic and environmental conditions through constraint-based modeling approaches like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [40] [41]. This integration is particularly valuable for strain design research, where understanding metabolic capabilities and limitations enables rational engineering of microbial cell factories [19] and live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) [3]. This protocol outlines computational and experimental frameworks for leveraging GEM-guided knockout strategies to identify essential genes and therapeutic targets, with applications spanning drug discovery, metabolic engineering, and personalized medicine.

Key Concepts and Definitions

- Essential Genes: Genes critical for cell survival, growth, or proliferation under specific conditions. Their knockout results in significant fitness defects or lethality [42].

- Synthetic Lethality (SL): A genetic interaction where the simultaneous disruption of two genes is lethal, while individual disruption of either gene is not. This concept provides opportunities for targeting non-essential genes in specific genetic contexts, such as cancers with tumor suppressor loss-of-function mutations [42].

- Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM): A computational model encompassing the entire metabolic network of an organism, represented as a stoichiometric matrix of biochemical reactions, genes, and metabolites [40] [9].

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): A constraint-based modeling technique used to simulate metabolic flux distributions in a GEM by optimizing an objective function (e.g., biomass production) under steady-state assumptions and physiological constraints [40] [41].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Screening: A high-throughput functional genomics approach that uses CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing with comprehensive single-guide RNA (sgRNA) libraries to systematically identify genes essential for survival or specific phenotypes [38].

Computational Workflows for Prediction

GEM-Based Essentiality Analysis

Genome-scale metabolic models enable in silico prediction of essential genes by simulating gene knockout effects on metabolic network functionality, typically assessed through impacts on biomass production [40].

Table 1: GEM Tools and Platforms for Essentiality Prediction

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEMsembler [9] | Consensus model assembly & analysis | Combines GEMs from different tools; improves gene essentiality predictions | Microbial systems biology; model curation |

| hiPSCGEM01 [40] | Context-specific metabolic modeling | Tailored to fibroblast-derived human iPSCs; identifies essential genes/metabolites | Stem cell research; regenerative medicine |

| TIDE Algorithm [41] | Inference of pathway activity from gene expression | Infers metabolic task changes from transcriptomic data without full GEM reconstruction | Analysis of drug-induced metabolic changes |