High-Throughput Screening in Metabolic Engineering: Biosensors, Workflows, and Strain Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced high-throughput screening (HTS) methods that are revolutionizing metabolic engineering.

High-Throughput Screening in Metabolic Engineering: Biosensors, Workflows, and Strain Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced high-throughput screening (HTS) methods that are revolutionizing metabolic engineering. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the critical challenge of evaluating vast genetic libraries for improved production of industrially valuable compounds. The content spans from foundational concepts of design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycles and biosensor engineering to practical applications of transcription factor-based biosensors and screening-by-proxy workflows. It further addresses troubleshooting common bottlenecks and validation strategies for translating screening hits into high-performing production strains. By synthesizing recent advances, this review serves as an essential resource for implementing efficient HTS platforms to accelerate strain development for biomedical and industrial applications.

The High-Throughput Imperative: Bridging the Design-Test Gap in Metabolic Engineering

The field of metabolic engineering aims to rewire microbial metabolism to produce high-value chemicals, fuels, and pharmaceuticals from renewable feedstocks [1] [2]. Despite transformative developments in the design-build-test-learn (DBTL) paradigm, a central challenge persists: moving beyond proof-of-concept examples to robust and economically viable production systems [3]. The core of this challenge lies in the combinatorial explosion that occurs when optimizing metabolic pathways. A pathway library containing just a single enzyme with 10 alternative promoters and 10 alternative RBS sequences requires testing approximately 10^2 variants. However, a two-enzyme pathway with all possible single non-synonymous mutations balloons to a theoretical 3.6 × 10^11 variants—a sequence space too vast for conventional methods [1]. This exponential complexity creates a critical strain development bottleneck, making High-Throughput Screening (HTS) not merely beneficial but essential for modern metabolic engineering.

Biosensors as Enabling Tools for HTS

Concept and Mechanism

Genetically encoded biosensors represent a transformative technology for HTS, functioning as genetic devices that convert intracellular metabolite concentrations into detectable output signals, most commonly fluorescence [4] [2]. These biosensors typically rely on metabolite-responsive transcriptional regulators that, upon binding their target molecule, activate or repress the expression of a reporter gene, such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) [4]. This mechanism allows researchers to indirectly quantify metabolite production through fluorescence measurements, enabling rapid assessment of strain performance without time-consuming analytical chemistry.

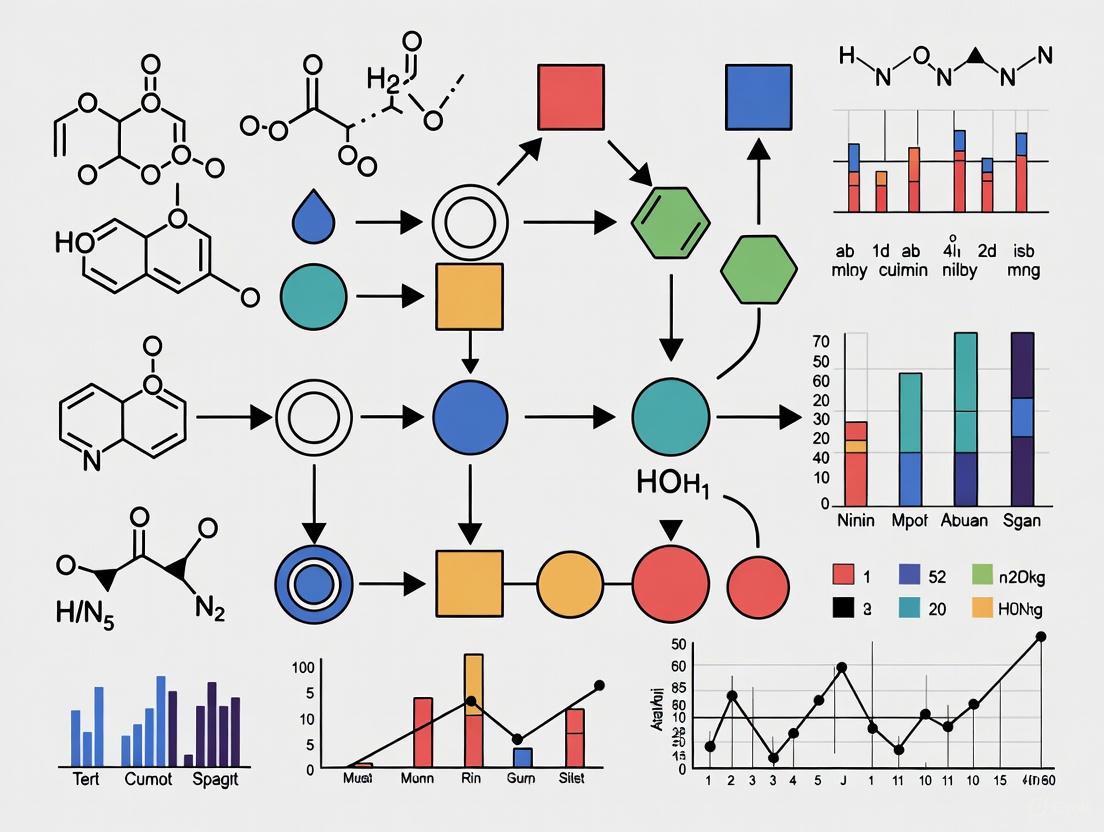

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental working mechanism of a transcription factor-based biosensor:

Case Study: Development of an L-Cysteine Biosensor

A 2022 study exemplifies the development and optimization of a genetically encoded biosensor for L-cysteine overproduction [4]. Researchers utilized the L-cysteine-responsive transcriptional activator CcdR, which specifically interacts with L-cysteine and binds to its regulatory region to induce gene expression. Through multilevel optimization strategies—including semi-rational design of the regulator and systematic optimization of genetic elements by modulating promoter and RBS combinations—they significantly improved the biosensor's dynamic range and sensitivity [4]. The optimized biosensor was then coupled with Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to establish an HTS platform, successfully enabling direct evolution of key enzymes in the L-cysteine biosynthetic pathway and screening of high-producing strains from random mutagenesis libraries [4].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Common HTS Assay Technologies

| Method | Sample Throughput (per day) | Sensitivity (LLOD) | Flexibility | Linear Response | Dynamic Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography | 10–100 | mM | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Direct Mass Spectrometry | 100–1000 | nM | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Biosensors | 1000–10,000 | pM | + | + | + |

| Screens | 1000–10,000 | nM | + | ++ | ++ |

| Selection | 10⁷+ | nM | + | + | + |

Adapted from analytics for metabolic engineering [3]. The optimal method for each criteria is highlighted in bold.

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Implementation

Protocol: Biosensor-Guided Screening for Metabolite Overproducers

Purpose: To identify high-producing metabolite variants from a library of engineered strains using a genetically encoded biosensor and FACS.

Materials:

- Library of engineered microbial strains harboring the biosensor system

- Appropriate growth medium and culture conditions

- Flow cytometer with cell sorting capability

- Microplate reader with fluorescence detection

- Validation equipment (e.g., LC-MS, GC-MS)

Procedure:

Library Cultivation: Inoculate the library variants in deep-well plates containing selective medium. Grow under optimal conditions for metabolite production with appropriate aeration [5].

Biosensor Response Measurement: Harvest cells during mid-to-late exponential growth phase. For fluorescence measurement, transfer aliquots to black-walled clear-bottom microplates and measure fluorescence using appropriate excitation/emission wavelengths [3].

Cell Sorting: Using FACS, sort populations based on fluorescence intensity into high, medium, and low producer categories. Collect at least 10,000 cells per population to ensure adequate diversity [4].

Recovery and Expansion: Plate sorted cells on solid medium and incubate to form isolated colonies. Pick multiple colonies from each sorted population and inoculate into fresh medium for validation studies.

Hit Validation: Cultivate sorted hits in small-scale bioreactors and quantify final product titers using gold-standard analytical methods such as LC-MS or GC-MS to confirm correlation between biosensor signal and actual production [4] [3].

Iterative Cycling: Subject validated hits to further rounds of engineering and screening to accumulate beneficial mutations or expression optimizations.

Protocol: Biosensor-Assisted Directed Evolution of Enzymes

Purpose: To improve catalytic efficiency of rate-limiting enzymes in a metabolic pathway using biosensor-guided screening.

Materials:

- Plasmid-borne biosensor system responsive to the pathway product

- Mutagenized library of the target enzyme gene

- Host strain with deleted native pathway to prevent background interference

- Fluorescence detection capability

Procedure:

Library Construction: Create a mutant library of the target enzyme using error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling, or site-saturation mutagenesis [1] [2].

Transformation: Co-transform the biosensor plasmid and mutant enzyme library into an appropriate host strain.

Screening: Plate transformed cells on solid medium or grow in liquid culture in microplates. Incubate until moderate fluorescence develops.

Selection: Using FACS or fluorescence-activated microplate sorting, isolate cells exhibiting the highest fluorescence signals, indicating superior enzyme activity [4] [2].

Characterization: Isplicate sorted clones, sequence the mutated genes, and characterize enzyme kinetics in vitro to confirm improvements.

Pathway Integration: Incorporate improved enzyme variants into the full metabolic pathway and assess overall impact on product yield and titer.

Combinatorial Pathway Optimization Strategies

Addressing Combinatorial Explosion

Combinatorial pathway optimization involves simultaneously diversifying multiple pathway elements to identify optimal combinations that maximize flux toward the desired product [6]. The primary challenge is the combinatorial explosion—the exponential increase in variant numbers as more pathway components are diversified. Three primary diversification strategies have emerged:

Variation of Coding Sequences: Utilizing different structural or functional gene homologues from various organisms that catalyze the same reaction [6].

Engineering of Expression Levels: Fine-tuning gene expression through promoter engineering, RBS optimization, plasmid copy number variation, and gene dosage adjustments [1] [6].

Combined and Integrated Approaches: Simultaneously integrating different methods for diversity creation to achieve substantial improvements [6].

Table 2: Strategies for Coping with Combinatorial Explosion in Pathway Optimization

| Strategy | Approach | Key Features | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modular Pathway Engineering | Partitioning pathways into functional modules | Reduces dimensionality; enables balanced expression of reaction groups | Taxadiene production [1] |

| Computational Predictions | Using models trained on empirical data | Reduces experimental burden; predicts high-performance variants | Violacein pathway optimization [1] |

| Empirical Heuristics | Applying biological rules to limit library size | Maintains diversity while reducing scale; leverages prior knowledge | Carotenoid pathway engineering [1] |

| Golden Gate Assembly | Standardized DNA assembly method | Enables rapid construction of pathway variants; high efficiency | Nitrogen fixation cluster refactoring [1] |

Experimental Workflow for Combinatorial Pathway Optimization

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for combinatorial pathway optimization, integrating modern DNA assembly methods with HTS:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS in Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Parts | Promoter libraries (e.g., J23100 series), RBS libraries, terminators | Fine-tuning gene expression levels; balancing metabolic flux [1] [6] |

| Biosensor Components | Transcription factors (e.g., CcdR for L-cysteine), riboswitches, aptamers | Connecting metabolite concentration to detectable signals for screening [4] [2] |

| Reporters | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, YFP, RFP), luciferases, chromogenic enzymes | Providing quantitative readouts for HTS campaigns [3] |

| DNA Assembly Systems | Golden Gate assembly, Gibson assembly, SLIC, VEGAS | Enabling rapid construction of pathway variant libraries [1] |

| Mutagenesis Tools | Error-prone PCR kits, MAGE oligo pools, CRISPR mutagens | Creating genetic diversity for directed evolution [1] [2] |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance genes, auxotrophic markers, toxin-antitoxin systems | Enriching for desired variants through growth-based selection [2] |

Scaling Considerations and Fermentation Translation

A critical challenge in HTS for metabolic engineering lies in ensuring that performance improvements detected at the microplate scale translate to industrially relevant bioreactor conditions [5]. Key considerations include:

Physiological Relevance: Miniaturized cultures must accurately mimic large-scale bioreactor conditions, including oxygenation, nutrient gradients, and waste accumulation [5].

Analytical Compatibility: Development of rapid, high-throughput analytical methods that correlate with gold-standard techniques while providing the necessary throughput for screening large libraries [3].

Scale-Down Models: Implementing microbioreactor systems that maintain control parameters similar to production-scale fermentations, enabling better prediction of scale-up performance [5].

Effective HTS strategies must therefore incorporate scale-relevant screening conditions and validation steps to ensure identified hits maintain their advantageous phenotypes in industrial production environments.

High-Throughput Screening has evolved from a complementary technique to an indispensable component of modern metabolic engineering, directly addressing the fundamental strain development bottleneck created by combinatorial complexity. Through genetically encoded biosensors, sophisticated DNA assembly methods, and integrated computational approaches, HTS enables researchers to navigate vast design spaces that would otherwise be intractable. As the field advances, the continued development of more sensitive biosensors, improved scale-down models, and automated screening platforms will further enhance our ability to efficiently design and optimize microbial cell factories for sustainable chemical production.

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a foundational, iterative framework in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering for systematically developing and optimizing microbial cell factories. This engineering paradigm enables researchers to progressively enhance strain performance by iteratively designing genetic modifications, building strains, testing their performance, and learning from the data to inform subsequent cycles [7] [8]. The power of the DBTL framework lies in its recursive nature; each cycle incorporates learning from previous experiments to progressively refine genetic designs and pathway configurations that maximize the production of target compounds [7]. This approach has become central to modern bioprocess development, with automated biofoundries increasingly implementing integrated DBTL workflows to accelerate strain engineering campaigns [9] [10].

Within the context of high-throughput screening methods for metabolic engineering, the DBTL framework provides the structural backbone for managing complex experimental workflows and large datasets. Recent advancements have introduced variations to the traditional cycle, including the knowledge-driven DBTL approach that incorporates upstream in vitro investigations to inform initial designs [10], and the LDBT paradigm that leverages machine learning predictions to generate initial designs before physical testing [8]. These innovations highlight the dynamic evolution of the DBTL framework as new technologies emerge, positioning it as an indispensable methodology for efficient biotech R&D.

Quantitative Performance of DBTL Cycle Strategies

The strategic implementation of DBTL cycles significantly impacts both the efficiency and success of strain engineering projects. Research utilizing mechanistic kinetic model-based frameworks has yielded important quantitative insights into how different approaches affect outcomes, particularly when dealing with combinatorial pathway optimization where testing all possible designs is experimentally infeasible [7].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DBTL Cycle Strategies

| Strategy Parameter | Performance Impact | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Large initial DBTL cycle | Favorable when strain building capacity is limited [7] | Combinatorial pathway optimization with limited build capacity |

| Equal-sized cycles | Less efficient for machine learning recommendation algorithms [7] | Same number of strains built per cycle |

| Gradient Boosting & Random Forest | Outperform other methods in low-data regimes [7] | Machine learning for recommending next-cycle designs |

| Knowledge-driven DBTL | 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over state-of-the-art [10] | Dopamine production in E. coli |

The effectiveness of DBTL cycles is further enhanced through machine learning integration, with specific algorithms demonstrating particular strengths for biological applications. Gradient boosting and random forest models have shown robust performance in low-data regimes common in early DBTL cycles, maintaining predictive accuracy despite training set biases and experimental noise [7]. These capabilities make them particularly valuable for recommending new strain designs in subsequent cycles, especially when the number of strains that can be built is constrained by resources or time.

DBTL Cycle Protocol for Systematic Strain Improvement

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive DBTL cycle workflow for metabolic engineering, incorporating both traditional and emerging approaches:

DBTL Cycle Workflow for Strain Engineering

Phase 1: Design

The Design phase involves planning genetic constructs and identifying metabolic engineering targets based on prior knowledge and project objectives.

Protocol: Knowledge-Driven Pathway Design

Define Engineering Objectives: Clearly specify target metabolite, desired yield/titer/productivity (TYP), and host system constraints [10].

Pathway Selection & Analysis:

- Identify heterologous enzymes and cofactor requirements

- Assess pathway thermodynamics and potential bottlenecks

- Analyze native host metabolism to identify necessary knock-outs or knock-ins

Promoter/RBS Library Design:

Combinatorial Library Strategy:

- Determine which pathway steps to target for multivariate optimization

- Plan library size based on high-throughput screening capacity

- Design DNA assembly strategy (Gibson assembly, Golden Gate) compatible with automated workflows [9]

Phase 2: Build

The Build phase translates genetic designs into physical DNA constructs and viable microbial strains.

Protocol: High-Throughput Strain Construction

DNA Assembly:

Host Transformation:

- Prepare electrocompetent or chemically competent cells of the production host

- Execute high-efficiency transformation protocols

- Plate on selective media and incubate for colony formation

Colony Processing:

- Pick individual colonies using automated colony pickers where available

- Culture in deep-well plates for plasmid verification and sequencing

- Prepare glycerol stocks for long-term storage of library variants

Cell-Free Alternative:

Phase 3: Test

The Test phase involves characterizing strain performance and collecting quantitative data on pathway functionality.

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening & Metabolite Analysis

Cultivation in Microtiter Plates:

- Inoculate from glycerol stocks into 96-well or 384-well deep-well plates

- Cultivate with appropriate media, antibiotics, and inducers

- Monitor growth kinetics via optical density (OD600) measurements

Metabolite Extraction & Analysis:

- Quench metabolism rapidly using cold methanol or other appropriate methods

- Extract intracellular metabolites for comprehensive analysis

- Prepare samples for LC-MS, GC-MS, or HPLC analysis of pathway metabolites

High-Throughput Analytics:

- Utilize automated plate readers (PerkinElmer EnVision, BioTek Synergy) for absorbance/fluorescence assays [9]

- Implement rapid sampling systems coupled to automated analytics

- Apply in situ monitoring techniques where possible to reduce handling

Cell-Free Testing:

- For cell-free prototyping, assay enzyme activities directly in lysates [10]

- Measure substrate consumption and product formation kinetics

- Identify rate-limiting steps and inhibitory effects

Phase 4: Learn

The Learn phase transforms experimental data into actionable insights for the next DBTL cycle.

Protocol: Data Integration & Machine Learning Analysis

Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize experimental data to account for plate-to-plate variation

- Remove outliers based on appropriate statistical criteria

- Integrate genotype-phenotype data into structured databases

Statistical Analysis:

- Perform correlation analysis between genetic modifications and performance metrics

- Identify significant factors influencing product titer/yield/productivity

- Conduct principal component analysis to visualize design space

Machine Learning Modeling:

- Train gradient boosting or random forest models on genotype-phenotype data [7]

- Validate model predictions using cross-validation techniques

- Identify feature importance to guide subsequent engineering targets

Design Recommendation:

- Use trained models to predict performance of untested genetic combinations

- Select designs that balance exploration of new regions with exploitation of promising areas

- Prioritize strains for the next DBTL cycle based on predicted performance and diversity

Advanced DBTL Methodologies

Knowledge-Driven DBTL Cycle

The knowledge-driven DBTL approach incorporates upstream in vitro investigations to inform initial strain designs, reducing reliance on purely statistical design methods. This methodology was successfully applied to optimize dopamine production in E. coli, resulting in a 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over previous state-of-the-art production levels [10].

Protocol: Integrated In Vitro to In Vivo Optimization

Cell-Free Pathway Prototyping:

- Express individual pathway enzymes using cell-free transcription-translation systems [10]

- Combine lysates in different ratios to test pathway functionality in vitro

- Identify optimal enzyme expression ratios before moving to in vivo implementation

RBS Library Implementation:

- Translate optimal expression ratios identified in vitro to RBS variants for in vivo expression

- Focus engineering on Shine-Dalgarno sequence modulation while maintaining constant flanking regions [10]

- Construct combinatorial RBS libraries targeting identified optimal expression windows

High-Throughput Validation:

- Screen RBS library variants for dopamine production in microtiter plates

- Analyze correlation between predicted and actual expression levels

- Select top performers for scale-up and further characterization

LDBT Paradigm: Learning Before Design

An emerging paradigm termed LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test) leverages machine learning and pre-existing datasets to generate initial designs before any physical testing occurs [8]. This approach is particularly powerful when combined with protein language models and structural prediction tools.

Protocol: Zero-Shot Design Using Protein Language Models

Sequence-Function Prediction:

Virtual Screening:

- Generate thousands of virtual enzyme variants computationally

- Rank variants based on predicted stability, activity, and expression

- Select top candidates for synthesis and testing

Experimental Validation:

- Build and test a subset of computationally designed variants

- Use results to refine and validate prediction models

- Iterate with expanded training data

Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Implementation

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for DBTL Cycles

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in DBTL Cycle |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Tecan Freedom EVO, Beckman Coulter Biomek, Hamilton STAR | High-precision pipetting for DNA assembly, PCR setup, and assay preparation [9] |

| DNA Synthesis Providers | Twist Bioscience, IDT, GenScript | Supply of custom DNA sequences and oligonucleotide libraries [9] |

| Cell-Free Systems | E. coli lysates, PURExpress | Rapid prototyping of pathways and enzymes without cellular constraints [8] [11] |

| High-Throughput Analytics | PerkinElmer EnVision, BioTek Synergy HTX | Multi-mode detection for screening thousands of samples [9] |

| DNA Assembly Methods | Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly | Modular, standardized construction of genetic circuits and pathways [9] |

| Machine Learning Platforms | TeselaGen Discover Module, Stability Oracle | Predictive modeling of genotype-phenotype relationships [9] [8] |

| RBS Engineering Tools | UTR Designer, RBS Calculator | Computational design of translation initiation elements for expression tuning [10] |

Integrated DBTL Case Study: Dopamine Production Optimization

A comprehensive example of the knowledge-driven DBTL cycle was demonstrated in the development of an E. coli dopamine production strain [10]. The following diagram illustrates the specific metabolic engineering strategy employed:

Dopamine Biosynthesis Pathway Engineering

Implementation Protocol:

Host Strain Engineering:

Heterologous Pathway Implementation:

RBS Library Screening:

- Construct RBS variants focusing on Shine-Dalgarno sequence modulation [10]

- Screen for dopamine production in minimal medium with controlled tyrosine feeding

- Identify optimal enzyme expression ratios maximizing dopamine yield

Performance Validation:

- Achieve dopamine titers of 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L (34.34 ± 0.59 mg/g biomass) [10]

- Scale up production in bioreactors for process optimization

- Characterize polydopamine production potential for material applications

This case study demonstrates how the structured DBTL framework, enhanced with upstream knowledge and high-throughput engineering, can significantly accelerate the development of efficient microbial production strains for valuable chemical compounds.

In the design–build–test–learn (DBTL) cycle of metabolic engineering, evaluating engineered organisms is a critical step [12]. The "Test" component relies primarily on two strategies for identifying high-performing strains: screening and selection. These methods balance throughput, flexibility, and the type of information gained, yet many researchers apply them interchangeably without a strategic foundation. Screening involves the individual assessment of thousands to millions of variants based on a measurable output, typically using automated systems to assay the target molecule or a correlated reporter [12]. In contrast, selection imposes a growth advantage or survival condition that directly couples the production of the target molecule to viability, powerfully enriching for desired clones from immense populations with minimal intervention [12]. The decision between these paths is consequential, impacting project timeline, resource allocation, and ultimate success. This Application Note delineates the operational boundaries for each method, provides quantitative frameworks for decision-making, and details contemporary protocols to integrate these strategies effectively within a metabolic engineering workflow.

Comparative Analysis: Screening vs. Selection at a Glance

The choice between screening and selection is multifaceted, depending on the target molecule, available assay technology, and project goals. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of each approach, while the subsequent decision tree provides a strategic framework for selection.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Screening and Selection Methodologies

| Feature | Screening | Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Measure a specific, detectable signal from each variant in a library. | Link production of the target molecule to cell survival or growth. |

| Throughput | High (e.g., thousands of variants via microplates) to Ultra-high (e.g., >10⁷ cells via FACS/MOMS [13]) | Very High (theoretically the entire library, often >10⁹ cells) |

| Key Advantage | Provides quantitative data on performance and can be applied to a wide range of molecules. | Powerful for reducing library size and isolating rare, high-performing clones from vast populations. |

| Primary Limitation | Throughput can be limited by assay speed and cost; can generate false positives. | Difficult to implement for many non-essential molecules; selective pressure may not correlate perfectly with production titer. |

| Ideal Use Case | Optimization of pathways and gene expression levels when a rapid, quantitative assay exists. | Initial identification of functional clones from large, diverse libraries (e.g., mutant libraries, biosynthetic pathways). |

| Data Output | Rich, quantitative data (e.g., fluorescence intensity, product titer). | Primarily qualitative/pass-fail data, though can be quantitative with careful design. |

| Resource Intensity | High per-data-point, but lower per-cell-analyzed. | Very low per-cell-analyzed after initial setup. |

Diagram 1: Strategy Selection Decision Tree

Advanced Screening Methodologies and Protocols

High-throughput screening (HTS) has evolved beyond simple absorbance measurements to encompass sophisticated platforms that offer remarkable sensitivity and speed. The core principle remains the rapid measurement of a target molecule or a proxy from thousands to millions of individual variants.

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening Using a Colorimetric Glycosyltransferase Assay

This protocol is adapted from a recent study that enhanced spinosad production in Saccharopolyspora spinosa [14]. It details the use of a broad-substrate glycosyltransferase (OleD) to detect a spinosad precursor (pseudoaglycone, PSA) via a colorimetric reaction.

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Essential Reagents for Colorimetric HTS

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Broad-Substrate Glycosyltransferase (OleD) | Enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of a sugar donor to the pseudoaglycone (PSA) acceptor substrate. |

| UDP-Sugar Donor | Uridine diphosphate-linked sugar molecule (e.g., UDP-glucose) used as a co-substrate by OleD. |

| Pseudoaglycone (PSA) Standard | The direct precursor to spinosad; used for assay calibration and optimization. |

| Chromogenic Substrate | A compound that produces a measurable color change upon glycosylation (specific compound not detailed in source). |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | A non-denaturing buffer to extract intracellular metabolites without inactivating enzymes. |

| 384- or 1536-Well Microplates | Assay platform compatible with automated liquid handling and high-density screening. |

2. Experimental Workflow:

Diagram 2: HTS via Colorimetric Assay Workflow

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Strain Preparation and Cultivation. Generate genetic diversity in your host (e.g., via random mutagenesis or targeted library construction). Culture mutant libraries in a 96- or 384-deep well format for a standardized period.

- Step 2: Metabolite Extraction. Harvest cells by centrifugation. Resuspend cell pellets in a suitable lysis buffer and incubate to release intracellular metabolites. Clarify the lysate by centrifugation to remove cell debris.

- Step 3: In Vitro Reaction Setup.

- Using an automated liquid handler, transfer a small aliquot (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the clarified lysate into a 384-well assay plate.

- Add the reaction master mix containing the glycosyltransferase (OleD), UDP-sugar donor, and the chromogenic substrate.

- Incubate the plate at a defined temperature (e.g., 30°C) for a fixed period to allow the colorimetric reaction to proceed.

- Step 4: Signal Detection and Analysis.

- Measure the absorbance or fluorescence of the reaction product in a plate reader.

- Normalize the signal to cell density (e.g., OD600) to account for variations in growth.

- Identify "hit" strains that show a statistically significant increase in signal compared to the parental control.

- Step 5: Hit Validation.

Emerging Screening Platforms: The MOMS Technology

For ultra-high-throughput screening, platforms like the Molecular Sensors on the Membrane Surface of Mother Yeast Cells (MOMS) represent a significant advancement. This technology uses aptamers selectively anchored to mother yeast cells to capture secreted metabolites directly on the cell surface [13].

- Throughput and Speed: The MOMS platform can analyze over 10⁷ single cells and screen at rates of 3.0 × 10³ cells/second, isolating rare secretory strains (0.05%) from 2.2 × 10⁶ variants in about 12 minutes [13].

- Sensitivity: It offers a high detection sensitivity with a limit of detection (LOD) of 100 nM for target molecules [13].

- Workflow: Yeast cells are biotinylated, then conjugated with streptavidin and biotin-labeled DNA aptamers specific to the target molecule (e.g., vanillin, ATP). During cell division, these sensors remain on the mother cell, creating a high-density sensor coat. When secreted molecules bind to the aptamers, they generate a fluorescent signal detectable via flow cytometry or similar methods, enabling efficient sorting of high-producers [13].

Implementing Selection Strategies

Selection is a powerful tool for isolating desirable phenotypes from extremely large libraries by creating a direct link between production of the target molecule and cell survival. While historically used for essential compounds, advances in biosensor engineering have expanded its application.

Protocol: Dynamic Metabolic Engineering for Growth-Coupled Production

This strategy, often called "dynamic regulation," does not always involve a simple growth selection but rebalances metabolism in response to cellular conditions to manage the trade-off between growth and production [15]. The following protocol outlines the process for implementing a dynamic control system.

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Essential Reagents for Dynamic Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Native Metabolite Sensor | A transcriptional regulator (e.g., one responsive to acetyl-phosphate) that senses an intracellular metabolite [15]. |

| Sensor-Responsive Promoter | A promoter sequence activated or repressed by the chosen sensor. |

| Essential Gene Target | A native essential gene (e.g., gltA for citrate synthase) whose expression can be dynamically controlled [15]. |

| Inducer Molecule | A chemical (e.g., IPTG) or a condition (e.g., nutrient shift) used to trigger the dynamic control system. |

| Fluorescent Protein Reporter | A gene (e.g., GFP) under the control of the sensor-responsive promoter, used to validate sensor activity via flow cytometry. |

2. Experimental Workflow:

Diagram 3: Dynamic Metabolic Engineering Workflow

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Identify Sensor and Metabolic Target.

- Target Identification: Choose a native enzyme central to metabolism (e.g., glucokinase, citrate synthase) whose knockdown or knockout diverts flux toward your product but is detrimental to growth [15].

- Sensor Selection: Identify a native transcriptional regulator that responds to a metabolic cue indicating imbalanced flux, such as acetyl-phosphate (AcP) buildup [15].

- Step 2: Genetic Circuit Construction.

- Place the essential metabolic gene (e.g.,

gltA) under the control of the sensor-responsive promoter. - Alternatively, implement a synthetic toggle switch that allows external induction (e.g., via IPTG) to shut off the essential gene [15].

- Introduce the heterologous production pathway for your target molecule.

- Place the essential metabolic gene (e.g.,

- Step 3: Fermentation and System Induction.

- Inoculate the engineered strain and allow a growth phase where the essential gene is expressed, and biomass accumulates.

- At a predetermined optimal time (e.g., mid-exponential phase), induce the system. This will downregulate the essential gene, redirecting carbon flux from growth to product formation.

- Step 4: Performance Analysis.

- Monitor cell growth (OD600) and product titer over time using HPLC or GC-MS.

- Compare the final yield and titer of the dynamically controlled strain against a constitutively expressing control strain. Studies have reported yield improvements of over two-fold using this approach [15].

Screening and selection are not mutually exclusive strategies; they can be powerfully integrated within a metabolic engineering DBTL cycle. Selection is unparalleled for the initial reduction of vast, complex libraries to a manageable number of candidates. Subsequently, screening provides the quantitative, multi-parametric data necessary to fine-tune and optimize the leading strains. The emergence of more sensitive and robust biosensors is blurring the lines between the two, enabling selection-like strategies for a wider array of molecules and screening assays with much higher throughput and information content [13] [12]. By understanding the principles, capabilities, and limitations of each method, researchers can make informed decisions that accelerate the development of robust microbial cell factories.

High-throughput screening (HTS) technologies serve as indispensable tools in metabolic engineering, enabling researchers to systematically evaluate vast libraries of microbial variants to identify strains with optimized production capabilities for target metabolites. The efficiency of these screening campaigns hinges on three fundamental performance metrics: dynamic range, sensitivity, and throughput. These parameters collectively determine the success of directed evolution and metabolic engineering efforts by balancing detection capabilities with processing speed. Current technological advancements continue to push the boundaries of these metrics, with emerging platforms achieving unprecedented performance levels that accelerate the development of manufacturing-ready strains for pharmaceutical, chemical, and biofuel applications [5].

The integration of HTS within metabolic engineering workflows has transformed the landscape of bioproduction. Where traditional methods struggled with the systematic evaluation of complex metabolic pathways, modern HTS platforms facilitate the rapid assessment of thousands to millions of genetic variants, pinpointing those with enhanced production phenotypes. This application note provides a detailed examination of key performance metrics through the lens of cutting-edge screening technologies, offering standardized protocols and analytical frameworks to guide researchers in selecting, implementing, and optimizing HTS platforms for metabolic engineering applications.

Performance Metrics Comparison of HTS Platforms

The selection of an appropriate HTS platform requires careful consideration of the interdependent relationship between sensitivity, throughput, and dynamic range. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of established and emerging screening technologies based on these critical parameters:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of High-Throughput Screening Platforms

| Screening Technology | Sensitivity (Limit of Detection) | Throughput (Cells per Run) | Screening Speed (Cells per Second) | Dynamic Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOMS [16] | 100 nM | > 10⁷ single cells | 3.0 × 10³ cells/second | > 3 orders of magnitude |

| FADS [16] | ~10 µM for most metabolites | ~10⁶ variants | 10-200 cells/second | ~2 orders of magnitude |

| RAPID [16] | ~260 µM | Limited by droplet encapsulation | < 10 cells/second | Limited by aptamer stability |

| Living-Cell Biosensors [16] | ~70 µM (e.g., for naringenin) | Constrained by co-culture issues | Variable, typically low | Dependent on biosensor response |

| Cell-Based Assays [17] | Variable based on assay design | ~10³-10⁴ cells per assay | Manual processing limitations | Determined by detection method |

| GC-MS/HPLC-MS [16] | High (pM-nM range) | ~1 cell per experiment | Very low (manual processing) | 4-5 orders of magnitude |

The MOMS (Molecular Sensors on the Membrane Surface of Mother Yeast Cells) platform demonstrates particularly advantageous characteristics for metabolic engineering applications, achieving over a 10-fold increase in sensitivity, more than a 2-fold improvement in throughput, and greater than a 30-fold enhancement in processing speed compared to conventional droplet-based screening methods [16]. This performance profile enables researchers to identify rare high-performing secretory strains representing just 0.05% of a population from 2.2 × 10⁶ variants within merely 12 minutes, a task that would require substantially more time with alternative technologies.

Experimental Protocol: MOMS for Single-Yeast Extracellular Secretion Analysis

Principle and Applications

The MOMS platform utilizes aptamers selectively anchored to mother yeast cells that remain confined during cell division, enabling high-sensitivity detection of extracellular secretions. This approach allows for high-density molecular sensor coating (1.4 × 10⁷ sensors/cell) on mother cells, facilitating precise assays of secreted molecules from individual yeast cells [16]. The technology is particularly valuable for directed evolution of yeast strains for enhanced production of valuable metabolites such as vanillin, where it has demonstrated the capability to identify strains with over 2.7 times higher secretion rates compared to parental strains [16].

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for MOMS Platform

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin | Biotinylates proteins on the yeast cell wall | Charged sulfonyl group ensures membrane impermeability |

| Streptavidin | Forms bridge between biotinylated cell surface and biotin-bearing DNA aptamers | High binding affinity for biotin |

| Biotin-bearing DNA Aptamers | Molecular sensors for target metabolites | Designed for specific targets (e.g., ATP, glucose, vanillin, Zn²⁺) |

| Cy5-labeled Aptamers | Visualization of MOMS coating | Excitation: 646 nm, Emission: 664 nm |

| Alexa Fluor 488-Concanavalin A (ConA) | Cell wall staining | Excitation: 495 nm, Emission: 520 nm |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | Viability assessment through esterase activity | Converted to fluorescent signal in live cells |

| Yeast Cells | Producer cells for extracellular secretions | Genetically engineered variants library |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Cell Surface Biotinylation:

- Harvest yeast cells during mid-log phase growth (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.6-0.8) by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 minutes.

- Wash cells twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4).

- Resuspend cells in PBS containing 1 mM sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin and incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation.

- Wash cells three times with PBS to remove excess biotinylation reagent.

Streptavidin Coupling:

- Resuspend biotinylated cells in PBS containing 100 µg/mL streptavidin.

- Incubate for 20 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation.

- Wash three times with PBS to remove unbound streptavidin.

Aptamer Immobilization:

- Resuspend cells in binding buffer appropriate for the selected DNA aptamers.

- Add biotin-bearing DNA aptamers at a concentration of 500 nM and incubate for 45 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation.

- Wash three times with binding buffer to remove unbound aptamers.

Validation and Quality Control:

- For visualization, substitute standard aptamers with Cy5-labeled aptamers during immobilization.

- Counterstain cell walls with Alexa Fluor 488-Concanavalin A (10 µg/mL for 10 minutes).

- Assess coating efficiency and selectivity using confocal laser scanning microscopy.

- Verify cell viability (>93% expected) using fluorescein diacetate staining.

Screening and Analysis:

- Dilute MOMS-coated cells to appropriate density for screening (typically 10⁶ cells/mL).

- Process cells through appropriate detection instrumentation (e.g., flow cytometer with sorting capability).

- Screen at rates up to 3.0 × 10³ cells/second to identify high-secreting variants.

- Collect sorted cells for downstream validation and cultivation.

Workflow Visualization

Performance Validation and Data Analysis

Sensitivity Assessment Protocol

Standard Curve Generation:

- Prepare serial dilutions of target metabolite in appropriate buffer.

- Incubate MOMS-coated cells with each concentration for 30 minutes.

- Measure fluorescence signal intensity using flow cytometry or plate reader.

- Plot signal intensity against metabolite concentration.

- Calculate limit of detection (LOD) using 3σ method (3 × standard deviation of blank / slope of standard curve).

Dynamic Range Determination:

- Identify minimum detectable concentration (LOD) and maximum signal saturation point.

- Calculate dynamic range as the ratio between saturation point and LOD.

- Verify linear range through regression analysis (R² > 0.98 expected).

Throughput Validation:

- Prepare cell library with known ratio of high- and low-secreting variants (e.g., 1:1000).

- Process library through complete MOMS workflow.

- Calculate recovery efficiency: (Number of high-secreting variants identified) / (Total high-secreting variants in library) × 100%.

- Determine false positive rate through follow-up validation of selected clones.

Data Interpretation Guidelines

The MOMS platform typically achieves a detection limit of 100 nM for target metabolites, with dynamic range exceeding three orders of magnitude [16]. Throughput validation should demonstrate processing of >10⁷ single cells per run with maintained viability >90% post-sorting. Data analysis should focus not only on identification of high-secreting variants but also on population distributions that provide insights into library diversity and engineering effectiveness.

Technology Integration in Metabolic Engineering Workflows

The MOMS platform represents a significant advancement in HTS capabilities for metabolic engineering, but its full potential is realized through strategic integration with complementary technologies. For target identification and pathway design, computational tools and genome-scale metabolic models provide essential guidance for library construction [5]. Subsequent to primary screening with MOMS, secondary validation using analytical methods such as GC-MS or HPLC-MS delivers rigorous quantification of strain performance [16]. This integrated approach ensures that the advantages of MOMS—exceptional speed and sensitivity—are coupled with the analytical precision of lower-throughput methods.

Future directions in HTS for metabolic engineering point toward increased integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with screening platforms [17]. These technologies enhance pattern recognition in high-dimensional data, improve hit selection criteria, and enable predictive modeling of strain performance. The continued miniaturization and automation of screening platforms further promises to enhance throughput while reducing reagent costs and experimental timelines, ultimately accelerating the development of robust microbial cell factories for sustainable bioproduction.

Biosensors and Screening Strategies: A Practical Toolkit for Strain Optimization

Transcription factor-based biosensors (TFBs) are genetically encoded devices that leverage the natural specificity of allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) to detect intracellular metabolites and regulate gene expression accordingly [18]. In synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, these biosensors have become indispensable tools for addressing a central challenge: the inability to monitor metabolic fluxes in real-time and the inefficiency of traditional, static strain-engineering methods [19]. By dynamically linking the concentration of a target small molecule to a measurable reporter output, such as fluorescence, TFBs enable high-throughput screening of microbial libraries, allowing for the rapid identification of high-producing cell factories [20] [18]. This application note details the engineering principles, experimental protocols, and key applications of TFBs, providing a framework for their use in accelerating metabolic engineering research.

Biosensor Engineering and Application in High-Throughput Screening

Molecular Architecture and Mechanism of Action

TFBs function through a modular mechanism involving three core steps: analyte recognition, signal transduction, and output generation [18] [19].

- Analyte Recognition: An allosteric transcription factor, acting as the sensor, binds to a specific small-molecule ligand (the analyte).

- Signal Transduction: Ligand binding induces a conformational change in the aTF. This change alters its affinity for a specific DNA operator sequence located within a synthetic promoter.

- Output Generation: The change in DNA binding either activates or represses transcription from the promoter, leading to a quantifiable change in the expression of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) [18].

This mechanism allows TFBs to be configured as either activators or repressors, providing flexibility for different applications [19]. The core components of a TFB system—the transcription factor, its cognate promoter, and the reporter—are genetically tunable, enabling optimization for sensitivity, dynamic range, and specificity [18].

Case Study: High-Yield Caffeic Acid Production

A recent breakthrough demonstrates the power of TFBs for strain engineering. Researchers developed a biosensor for p-coumaric acid (p-CA), a precursor to the valuable compound caffeic acid (CA), by engineering CarR, a transcription factor from Acetobacterium woodii [20].

Application Workflow:

- Biosensor Construction: The optimized p-CA biosensor was coupled with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

- High-Throughput Screening: The platform enabled the rapid selection of an improved enzyme mutant with a 6.85-fold enhancement in catalytic activity and a robust production strain with enhanced tolerance to phenolic acids.

- Strain Performance: Subsequent metabolic engineering in a bioreactor setting achieved a CA titer of 9.61 g L⁻¹, the highest reported to date [20].

This case highlights how TFBs can overcome key bottlenecks in bioproduction, including low enzyme activity and product cytotoxicity.

Advanced Platform: Sensor-seq for De Novo Biosensor Design

A significant limitation in the field has been the scarcity of aTFs for many molecules of interest. The Sensor-seq platform addresses this by enabling the highly multiplexed design of aTFs that sense non-native ligands [21].

Key Features of Sensor-seq:

- High-Throughput Screening: The platform uses RNA barcoding and deep sequencing to quantitatively assess the activity of thousands of aTF variants in response to target ligands simultaneously.

- Overcoming Natural Constraints: In one study, Sensor-seq screened 17,737 variants of the promiscuous aTF TtgR against eight ligands. It successfully identified biosensors for diverse non-native molecules, including the opiate analog naltrexone and the antimalarial drug quinine [21].

- Practical Utility: The engineered biosensors were used to construct cell-free detection systems, demonstrating their immediate application for detecting compounds like opioid contaminants [21].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Featured Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors

| Transcription Factor | Native or Target Ligand | Application / Engineered Ligand | Key Performance Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarR (from A. woodii) | Phenolic Acids | Caffeic Acid / p-Coumaric Acid | Achieved 9.61 g L⁻¹ CA titer; 6.85-fold enzyme improvement | [20] |

| TtgR (from P. putida) | Flavonoids (e.g., Naringenin) | Naltrexone & Quinine (non-native) | Developed functional cell-free biosensors for new ligands | [21] |

| TtgR (from P. putida) | Flavonoids | Resveratrol & Quercetin | Quantified target at 0.01 mM with >90% accuracy | [22] |

| YpItcR (from Y. pseudotuberculosis) | Itaconic Acid | L-Glutamic Acid, L-Lysine, L-Threonine | Created mutants for sensitive AA detection via directed evolution | [23] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a generalized protocol for developing and implementing a TFB for high-throughput screening, synthesizing methodologies from the cited research.

Protocol 1: Biosensor Construction and Initial Characterization

Objective: To clone a genetic circuit into a microbial host and characterize its basic response to a target ligand.

Materials:

- Strains: E. coli BL21(DE3) or DH5α for cloning and initial testing [22].

- Vectors: Standard plasmids (e.g., pCDF-Duet, pET-21a) with compatible origins of replication and antibiotic resistance [22].

- Enzymes & Kits: Restriction enzymes, ligase, high-fidelity DNA polymerase, site-directed mutagenesis kit, genomic DNA extraction kit [22] [23].

Methodology:

- Gene Amplification: Amplify the gene encoding the transcription factor (e.g., ttgR, ypitcR) and its native promoter/operator region from the source organism's genomic DNA [22].

- Plasmid Assembly:

- Clone the transcription factor gene into one plasmid under a constitutive promoter.

- Clone the corresponding operator-promoter sequence, fused to a reporter gene (e.g., egfp), into a second, compatible plasmid [22].

- Transformation: Co-transform both plasmids into the chosen microbial host (e.g., E. coli BL21) to create the full biosensor system.

- Initial Characterization:

- Inoculate biosensor strains in liquid medium with a range of ligand concentrations.

- Measure reporter output (e.g., fluorescence) and cell density (OD₆₀₀) during the log growth phase.

- Calculate the fold-change in output (e.g., fluorescence/OD) between induced and uninduced states to determine the dynamic range [22] [24].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening Using FACS

Objective: To use the constructed biosensor in a FACS-based screen to isolate high-producing clones from a variant library.

Materials:

- Biosensor Strain harboring the production pathway of interest.

- Library: A diverse population of cells (e.g., from random mutagenesis or directed evolution of a pathway enzyme) [20] [25].

- Equipment: Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS).

Methodology:

- Library Preparation: Generate a library of strain variants through mutagenesis or other diversity-generation methods.

- Cultivation: Grow the library under conditions that induce the biosynthetic pathway.

- FACS Sorting:

- Prepare a single-cell suspension of the library.

- Set sorting gates on the FACS instrument to select cells exhibiting the highest fluorescence intensity, which correlates with high intracellular metabolite concentration.

- Sort the top 0.1-1% of the population into recovery media [20].

- Validation: Regrow the sorted populations and re-assay for product titer to confirm enrichment of high-producers. Iterate the sorting process if necessary [25].

Protocol 3: Sensor-seq for Biosensor Engineering

Objective: To screen a vast library of aTF variants for new ligand specificities using the Sensor-seq platform [21].

Materials:

- Library Plasmid: A screening construct where each aTF variant is associated with a unique RNA barcode in the reporter transcript.

- Ligands: Target molecules for screening.

- Equipment & Reagents: Next-generation sequencer, RNA extraction kit, cDNA synthesis kit, PCR reagents.

Methodology:

- Library Creation: Generate a diverse library of aTF mutants, for example, by targeting the ligand-binding pocket of a promiscuous aTF like TtgR [21].

- Pooled Cultivation & Induction: Culture the pooled library and split into aliquots. Treat with either the target ligand or a vehicle control during log-phase growth.

- RNA & DNA Extraction: Harvest cells to isolate both total RNA (for transcript quantification) and plasmid DNA (for normalization).

- Sequencing & Mapping:

- Prepare cDNA from RNA and use PCR to link the barcode in the reporter transcript to the aTF variant sequence from the plasmid DNA.

- Perform deep sequencing on these constructs.

- Data Analysis (F-score calculation):

- For each variant, calculate the F-score: the normalized ratio of its barcode counts in the cDNA (from ligand-treated cells) to its counts in the plasmid DNA.

- Variants with F-scores significantly >1 are considered responsive to the ligand [21].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key experimental stages for developing and applying transcription factor-based biosensors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for TFB Development and Implementation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Allosteric Transcription Factor (aTF) | The core sensing element; binds the target ligand and regulates transcription. | CarR (for phenolic acids) [20], TtgR (promiscuous, for flavonoids/drugs) [22] [21], YpItcR (for itaconic acid/amino acids) [23]. |

| Reporter Gene | Produces a quantifiable signal in response to aTF activation/repression. | egfp (enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein) for FACS [22], rfp (Red Fluorescent Protein), luciferase. |

| Expression Vectors | Plasmids for hosting the genetic circuit; require compatibility for co-expression. | pCDF-Duet, pET-21a(+), pZnt-eGFP [22]. |

| Host Strain | The microbial chassis for biosensor operation and screening. | E. coli BL21(DE3), E. coli DH5α [22]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Platform | Instrumentation for isolating or analyzing high-performing variants. | FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter) [20] [25], Next-Generation Sequencer (for Sensor-seq) [21]. |

| Ligand / Analyte | The target small molecule to be detected. | Caffeic acid, naringenin, naltrexone, quinine, amino acids [20] [22] [23]. |

Transcription factor-based biosensors represent a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, moving beyond static design to dynamic, real-time monitoring and control of microbial cell factories. As demonstrated by their successful application in producing high-value compounds like caffeic acid and in creating sensors for non-native ligands, TFBs are powerful tools for overcoming critical bottlenecks in strain development. The integration of advanced methods like Sensor-seq and FACS with sophisticated computational design is paving the way for a future where bespoke biosensors can be rapidly developed for any molecule of interest, dramatically accelerating the engineering of robust microbial production systems for pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and materials.

A fundamental challenge in metabolic engineering is identifying genetic modifications that enhance the production of industrially valuable small molecules. For many target compounds, direct high-throughput (HTP) screening is not feasible because the molecules lack detectable properties like color or fluorescence, and specific biosensors are often unavailable [26]. Screening-by-Proxy overcomes this bottleneck by leveraging the detection of precursor metabolites that are easier to screen for in a HTP manner. This approach uses a proxy molecule, typically a biosynthetic precursor, as a surrogate to identify genetic targets that improve the flux toward the final compound of interest [26]. The core premise is that genetic perturbations increasing the cellular pool of the precursor are likely to also enhance the production of the target molecule derived from that precursor. This method is particularly valuable for non-canonical compounds where direct screening assays do not exist, enabling the application of vast HTP genetic engineering libraries that would otherwise be impractical to screen.

Conceptual Framework and Key Principles

The conceptual workflow for Screening-by-Proxy rests on several key principles. First, a robust, HTP-compatible assay must be established for a precursor in the biosynthetic pathway of the target compound. This precursor should be a metabolic chokepoint, such that its supply significantly influences the production level of the final product [26]. The proxy molecule must be chosen so that genetic modifications that increase its production are likely to have a correlated, beneficial effect on the target molecule's titer.

This strategy decouples the screening process into two distinct phases:

- An initial HTP screening of a diverse genetic library using the proxy assay to identify a subset of candidate genetic perturbations.

- A subsequent low-throughput (LTP) validation where the top candidates are tested individually for their impact on the actual target compound using precise, but slower, analytical methods like HPLC or LC-MS [26].

This coupled workflow allows researchers to efficiently sift through thousands of potential genetic modifications using a rapid proxy, then focus resources on validating the most promising hits for the true compound of interest.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol details the application of Screening-by-Proxy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the identification of metabolic engineering targets that improve the production of p-coumaric acid (p-CA) and L-DOPA, using fluorescent betaxanthins as a proxy for L-tyrosine precursor supply [26].

Reagent Setup and Strain Construction

Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Reagent/Strain | Function/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | S. cerevisiae base strain | Parental yeast strain for genetic engineering. |

| Betaxanthin Screening Strain (e.g., ST9633) | Engineered strain producing fluorescent betaxanthins from L-tyrosine. Contains feedback-insensitive ARO4K229L and ARO7G141S alleles [26]. | |

| Target Molecule-Producing Strain(s) | Strain(s) engineered to produce the final target molecule(s) (e.g., p-CA, L-DOPA). | |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPRi/a gRNA Library (e.g., dCas9-Mxi1, dCas9-VPR) | Plasmid library for transcriptional repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) of ~1000 metabolic genes [26]. |

| sgRNA Plasmid Library | Array-synthesized gRNA library targeting metabolic genes. | |

| Media & Buffers | Mineral Media | Defined media for cultivation during screening and validation. |

| FACS Buffer | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or similar for cell sorting. | |

| Assay Reagents | Betalamic Acid & Amines | For betaxanthin formation (if not produced endogenously). |

| - | - |

Strain Construction:

- Betaxanthin Screening Strain: Integrate a betaxanthin expression cassette into the yeast genome to ensure uniform expression. The cassette should contain genes for the conversion of L-tyrosine to betalamic acid. Introduce feedback-insensitive alleles of key aromatic amino acid (AAA) pathway genes (e.g., ARO4K229L, ARO7G141S) to deregulate precursor supply [26].

- Target Molecule-Producing Strains: Construct separate strains for the production of your target molecules (e.g., p-CA, L-DOPA). For p-CA, express a tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL). For L-DOPA, express the appropriate biosynthetic enzymes.

Primary HTP Screening with Proxy Metabolite

Library Transformation and Cultivation:

- Transform the betaxanthin screening strain with the CRISPRi/a gRNA library plasmids using a high-efficiency transformation protocol [26].

- Plate the transformed library on solid mineral media and incubate for 2-4 days to obtain single colonies.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS):

- Resuspend colonies from the transformation plates in liquid mineral media.

- Analyze and sort the cell population using a FACS sorter. Set the gating strategy to collect the top 1-3% of the population with the highest fluorescence (excitation: ~463 nm, emission: ~512 nm) [26].

- Collect approximately 8,000-10,000 high-fluorescence events.

Hit Isolation and Primary Validation:

- Allow the sorted cells to recover in mineral media overnight.

- Plate the recovered cells on mineral media agar plates and incubate for 3-4 days to obtain single colonies.

- Visually select several hundred of the most intensely yellow-pigmented colonies.

- Inoculate these hits into a 96-deep-well plate containing mineral media and cultivate for 48 hours.

- Measure the fluorescence of each culture and benchmark it against the parent screening strain to calculate a fold-change in betaxanthin production.

Target Identification:

- Isolate the sgRNA plasmids from the top-performing strains (e.g., those with a normalized fluorescence fold-change >3.5 and statistical significance).

- Sequence the plasmids to identify the genetically perturbed metabolic targets responsible for the increased proxy signal.

Secondary Validation with Target Molecules

Strain Reconstruction and Small-Scale Production:

- Individually reintroduce the identified sgRNAs into fresh betaxanthin, p-CA, and L-DOPA production strains.

- For each reconstructed strain and a control strain, perform small-scale fermentations in shake flasks or deep-well plates.

Quantification of Target Molecules:

- Sample Collection: Collect culture supernatant at appropriate time points.

- LTP Analysis: Analyze the samples for p-CA and L-DOPA concentration using suitable analytical methods (e.g., HPLC or LC-MS). These methods are low-throughput but provide precise quantification of the target molecules [26].

- Data Analysis: Compare the titers of the engineered strains to the control strain to validate which genetic perturbations from the proxy screen successfully improve production of the true target.

Advanced Workflow: Combinatorial Library Screening

Multiplexed Library Construction:

- Create a secondary gRNA library targeting combinations of the most promising validated hits from the initial screen.

Iterative Screening:

- Subject this combinatorial library to the same coupled Screening-by-Proxy workflow (FACS sorting based on betaxanthin fluorescence, followed by LTP validation on target molecules) to identify synergistic genetic interactions that yield additive or multiplicative improvements in titer [26].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Results from a Case Study

The following table summarizes exemplary quantitative data obtained from a Screening-by-Proxy study targeting p-CA and L-DOPA in yeast [26].

Table 1: Summary of Screening Outcomes for p-Coumaric Acid and L-DOPA Production

| Screening Stage | Metric | Value / Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Primary HTP Proxy Screen (Betaxanthins) | Number of initial hits (from FACS) | ~350 colonies selected |

| Fluorescence fold-change range (top hits) | 3.5 - 5.7 fold | |

| Unique gene targets identified | 30 | |

| Secondary LTP Validation (p-CA) | Number of targets increasing p-CA titer | 6 |

| Maximum improvement in secreted p-CA titer | Up to 15% | |

| Secondary LTP Validation (L-DOPA) | Number of targets increasing L-DOPA titer | 10 |

| Maximum improvement in secreted L-DOPA titer | Up to 89% | |

| Combinatorial Screening | Most effective combination (genes) | PYC1 + NTH2 |

| Betaxanthin content improvement (combination) | 3 fold |

Visual Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflow and relevant metabolic pathways for the Screening-by-Proxy approach.

Diagram Title: Screening-by-Proxy Workflow for p-CA & L-DOPA

Diagram Title: Metabolic Pathways for Proxy and Target Molecules

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) has emerged as a cornerstone technology in metabolic engineering, enabling researchers to screen vast libraries of microbial strains with unprecedented speed and precision. This powerful combination of flow cytometry and cell sorting allows for the multiparametric analysis and physical separation of single cells based on specific fluorescence signals, making it ideal for identifying rare, high-producing variants in genetically diverse populations [27] [28]. The integration of intracellular metabolite-responsive biosensors has further revolutionized the field by connecting the production levels of a target molecule to a measurable fluorescence output, thereby creating a direct high-throughput readout of metabolic activity [27] [29]. Within the context of high-throughput screening methods for metabolic engineering research, FACS provides an essential tool for bridging the gap between genetic library generation and the identification of optimized microbial cell factories, significantly accelerating the design-build-test-learn cycle for developing industrial bioprocesses.

Key Applications in Metabolic Engineering

Recombinant Strain Screening

Metabolic engineering of microbial cells focuses on optimizing microbial metabolism to enable and improve the production of target molecules ranging from biofuels and chemical building blocks to high-value pharmaceuticals [27]. The advances in genetic engineering, including CRISPR/Cas9 systems and DNA assembler techniques, have simplified the construction of highly engineered microbial strains and the generation of extensive genetic libraries [27]. FACS completes this pipeline by enabling the isolation of highly fluorescent single cells—and thus genotypes that produce higher levels of the metabolite of interest—from these libraries at an ultra-high-throughput scale [27]. This approach is particularly valuable for screening promoter libraries, gRNA libraries, and other genetic variants where subtle differences in gene expression significantly impact metabolic flux and final product titers.

Dynamic Regulation of Metabolic Fluxes

A significant challenge in metabolic engineering involves balancing the inherent trade-off between cell growth and product synthesis. Genetic circuits with metabolite-responsive elements offer a sophisticated solution for dynamically controlling metabolic pathways [29]. When coupled with FACS, these circuits enable high-throughput screening of strains capable of autonomously adjusting intracellular metabolic flux according to their own metabolic status [29]. For instance, biosensors that respond to intermediate or final pathway metabolites can be linked to fluorescent reporter genes, allowing FACS to identify variants that spontaneously maximize metabolic flux toward the product synthesis pathway without compromising cell viability [29]. This dynamic regulation capability represents a significant advancement over traditional constitutive expression strategies.

Directed Evolution of Enzymes and Biosensors

FACS has proven to be a powerful tool for directed enzyme evolution due to its high sensitivity and ability to analyze up to 10⁸ mutants per day [30]. This ultrahigh-throughput screening capability allows researchers to isolate enzyme variants with significantly improved activities, altered substrate specificities, or even novel catalytic functions [30]. Similarly, FACS-based screening facilitates the development and optimization of genetically encoded biosensors, which are crucial components for connecting metabolite production to fluorescence readouts. For example, through directed evolution of the CysB transcription factor, researchers created a mutant biosensor (CysBT102A) with a 5.6-fold increase in fluorescence responsiveness across a 0–4 g/L L-threonine concentration range [31]. This biosensor improvement was pivotal in screening for high-producing L-threonine strains, ultimately yielding a strain that produced 163.2 g/L in a 5 L bioreactor [31].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of FACS in Metabolic Engineering Applications

| Application Area | Throughput Capacity | Key Performance Metrics | Reference Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Strain Screening | Varies with library size | Isolation of high-producing genotypes from complex libraries | Screening yeast libraries with intracellular biosensors [27] |

| Directed Enzyme Evolution | Up to 10⁸ mutants per day | Identification of variants with improved activity or novel function | Evolution of catalytic antibodies and ribozymes [30] |

| Biosensor-Assisted Screening | Millions of events per session | 5.6-fold increase in biosensor responsiveness | CysBT102A mutant for L-threonine detection [31] |

| Plant Metabolic Engineering | Millions of protoplasts per session | Predictive screening for lipid accumulation traits | Identification of ABI3 role in lipid metabolism [32] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Biosensor-Assisted FACS for Metabolite Overproducer Screening

This protocol details the procedure for identifying metabolite overproducing strains using a biosensor-based FACS approach, as demonstrated for L-threonine overproduction in E. coli [31].

Materials and Reagents

- Biosensor Plasmid: Contains a metabolite-responsive promoter (e.g., PcysK for L-threonine) fused to a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., eGFP) and the corresponding transcription factor (e.g., CysB or evolved CysBT102A) [31].

- Mutant Library: Comprises a diverse population of engineered strains with variations in metabolic pathway regulation, gene expression levels, or enzyme activities.

- Growth Medium: Appropriate selective medium for maintaining plasmid pressure and supporting normal cellular metabolism.

- Reference Strains: Include known high-producing and low-producing strains for setting FACS gates.

- Flow Cytometry Buffer: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or similar isotonic buffer, potentially supplemented with a viability dye to exclude dead cells.

Procedure

Library Transformation and Culture:

- Transform the biosensor plasmid into the mutant library population using standard electroporation or chemical transformation methods.

- Plate transformed cells on selective solid medium and incubate until colonies appear.

- Scrape colonies from plates and inoculate into liquid selective medium. Grow cultures to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5-0.8) under standard conditions (e.g., 37°C with shaking).

Sample Preparation for FACS:

- Dilute cultures to approximately 10⁶ cells/mL in flow cytometry buffer.

- Filter samples through a 35-40 µm cell strainer to remove aggregates and prevent nozzle clogging.

- Keep samples on ice and protected from light until sorting to minimize fluorescence decay and metabolic changes.

FACS Instrument Setup and Sorting:

- Calibrate the flow cytometer using calibration beads and reference strains.

- Establish sorting gates based on fluorescence intensity of reference strains: collect cells with fluorescence signals in the top 0.1-5% of the population.

- Sort cells using a 70-100 µm nozzle at appropriate pressure (typically 30-70 psi) to maintain viability.

- Collect sorted cells into recovery medium supplemented with nutrients to reduce stress.

Post-Sort Processing and Validation:

- Spread sorted cells onto selective solid medium and incubate to form single colonies.

- Pick individual colonies and cultivate in deep-well plates for metabolite quantification.

- Validate production titers using analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS) to confirm correlation with fluorescence intensity.

- Recover biosensor plasmid from top producers to eliminate potential biosensor effects on production and re-test production capability.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for FACS-Based Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolite-Responsive Biosensors | Links intracellular metabolite levels to fluorescence output | PcysK promoter with CysB transcription factor for L-threonine [31] |

| Genetic Libraries | Provides diversity for screening improved producers | Promoter libraries, gRNA libraries, mutant libraries [27] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Generates measurable signal for sorting | eGFP, mCherry, and other fluorescent proteins [27] |

| Selection Markers | Maintains plasmid stability during culture | Antibiotic resistance genes (ampicillin, kanamycin) |

| Cell Viability Dyes | Excludes dead cells from analysis and sorting | Propidium iodide, DAPI (for fixed cells) |

| Flow Cytometry Buffer | Maintains cell integrity during sorting | PBS, supplemented with EDTA or glucose if needed |

Protocol 2: FACS-Based Screening of Plant Protoplasts for Metabolic Traits

This protocol adapts FACS for plant metabolic engineering using protoplast systems, enabling rapid screening without the need for generating stable transgenics [32].

Materials and Reagents

- Plant Material: Fresh tissue from species of interest (e.g., tobacco leaves).

- Protoplast Isolation Solution: Contains cell wall-degrading enzymes (cellulase, macerozyme) in appropriate osmoticum.

- Transformation Reagents: Polyethylene glycol (PEG) solutions or electroporation equipment.

- Fluorescent Probes: Lipid-soluble dyes (e.g., Nile Red, BODIPY) for neutral lipid staining.

- W5 and MMg Solutions: For protoplast washing and transformation.

Procedure

Protoplast Isolation:

- Slice plant tissue into thin strips and immerse in enzyme solution.

- Incubate with gentle shaking (30-50 rpm) for 3-16 hours in the dark until protoplasts release.

- Filter through 40-100 µm mesh to remove undigested debris.

- Wash protoplasts by centrifugation in W5 solution and resuspend in MMg solution at appropriate density (10⁵-10⁶ cells/mL).

Transformation and Trait Development:

- Mix protoplasts with DNA constructs (e.g., transcription factors like ABI3, WRI1 for lipid accumulation).

- Add PEG solution to facilitate DNA uptake and incubate for 15-30 minutes.

- Dilute with W5 solution, wash by gentle centrifugation, and resuspend in culture medium.

- Incubate for 24-72 hours to allow transgene expression and metabolite accumulation.

Staining and FACS Analysis:

- Add fluorescent dye (e.g., Nile Red for lipids) to protoplast suspension and incubate in dark.

- Analyze by flow cytometry to identify high-fluorescence populations.

- Sort high-fluorescence protoplasts into collection medium.

Regeneration and Validation:

- Culture sorted protoplasts in regeneration medium to facilitate cell division and callus formation.

- Transfer developing calli to differentiation medium to regenerate whole plants.

- Analyze regenerated plants for stable metabolic trait inheritance and productivity.

Technological Advances and Integration

Emerging High-Throughput Platforms