Metabolic Engineering for Alkane to Diol Bioconversion: Pathways, Hosts, and Future Bioproduction

This article explores the cutting-edge metabolic engineering strategies enabling the microbial conversion of alkanes into valuable diols, key building blocks for polymers and pharmaceuticals.

Metabolic Engineering for Alkane to Diol Bioconversion: Pathways, Hosts, and Future Bioproduction

Abstract

This article explores the cutting-edge metabolic engineering strategies enabling the microbial conversion of alkanes into valuable diols, key building blocks for polymers and pharmaceuticals. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it provides a comprehensive analysis spanning foundational principles, advanced CRISPR and pathway engineering methodologies, common troubleshooting challenges, and a comparative evaluation of microbial production hosts. The scope includes recent breakthroughs in yeast and bacterial engineering, platform technologies like polyketide synthases, and future directions for advancing sustainable biomanufacturing.

From Hydrocarbons to Diols: Foundational Pathways and Host Organisms

The Chemical Value of Medium- and Long-Chain α,ω-Diols

Medium- and long-chain α,ω-diols (mcl- and lcl-diols) are aliphatic compounds containing hydroxyl groups at both terminal carbon atoms. These valuable chemical building blocks traditionally derive from fossil-based industrial processes but are increasingly produced via sustainable microbial biosynthesis [1]. The global market for key diols like 1,6-hexanediol is substantial and growing, with an expected value of $1401 million by 2025 and annual growth trends of approximately 8% [1] [2]. This application note details their chemical value, production metrics, and experimental protocols within the context of alkane bioconversion and metabolic engineering research.

Applications and Chemical Value

α,ω-Diols serve as versatile precursors and intermediates across multiple industries. Their value stems from their bifunctional nature, which enables polymerization and chemical modification.

Table 1: Industrial Applications of Medium- and Long-Chain α,ω-Diols

| Application Sector | Specific Uses | Relevant Diol Chain Lengths |

|---|---|---|

| Polymers & Materials | Monomers for polyesters (e.g., PBT) and polyurethanes; building blocks for specialty chemicals [1] [3] [2]. | C6-C12 (medium-chain); >C12 (long-chain) |

| Surfactants & Cosmetics | Ingredients in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals; moisturizers, solubilizers, preservative boosters [4] [2]. | C3-C5 (branched-chain); C6-C12 |

| Specialty Chemicals | Solvents, lubricants, feed additives [4] [5]. | C3-C12 |

Branched-chain diols such as isopentyldiol (IPDO) are particularly appealing for cosmetics due to superior skin feeling, deodorization, and antibacterial properties [4] [6].

Quantitative Production Metrics in Microbial Systems

Significant progress has been made in engineering microbial platforms for diol production. Performance varies considerably based on chassis organism, substrate, and pathway engineering.

Table 2: Production Metrics for Microbial α,ω-Diols

| Chassis Organism | Substrate | Product | Titer | Productivity | Key Engineering Strategy | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Glucose | 1,4-BDO | 18 g/L | - | Well-established, concise biosynthetic pathway from TCA cycle intermediates [3]. | |

| E. coli | 1,12-diacid | 1,12-dodecanediol | 68 g/L | 1.42 g/(L·h) | Expression of carboxylic acid reductase (CAR) and phosphopantetheinyl transferase [7]. | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica (YALI17) | n-Dodecane | 1,12-dodecanediol | 3.2 mM (~0.65 g/L) | - | Systematic knockout of oxidation pathway genes (ADH, FALDH) and overexpression of Alk1 [3]. | |

| E. coli | Glucose | C3-C5 Branched Diols (e.g., IPDO) | - | - | Novel pathway combining oxidative and reductive formation of OH-groups from amino acids [4] [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Diol Production

Protocol 1: De Novo Production of 1,12-Dodecanediol from Alkanes inYarrowia lipolytica

This protocol details the metabolic engineering and biotransformation process for producing 1,12-dodecanediol from n-dodecane, resulting in a 14- to 29-fold increase in titer [3].

Strain Engineering via CRISPR-Cas9

Objective: Block competing over-oxidation pathways to prevent conversion of diol intermediates to carboxylic acids.

- Knockout Genes: Target 10 genes involved in fatty alcohol oxidation (

FADH,ADH1-8,FAO1) and 4 fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase genes (FALDH1-4) [3]. - Tool: CRISPR-Cas9 system for Y. lipolytica.

- Procedure:

- Design sgRNAs with high specificity to target gene sequences.

- Construct a repression vector harboring Cas9 and multiple sgRNA scaffolds.

- Transform the Y. lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ strain.

- Validate gene knockouts via sequencing and phenotypic screening.

Enhancing Alkane Hydroxylation

Objective: Increase flux from alkane to fatty alcohol.

- Overexpression: Introduce the alkane hydroxylase gene

ALK1into the engineered base strain (e.g., YALI17) [3]. - Procedure:

- Clone the

ALK1gene into an appropriate expression vector. - Transform the engineered Y. lipolytica strain.

- Select positive clones and confirm

ALK1expression.

- Clone the

Biotransformation and Fed-Batch Fermentation

Materials:

- Strain: Engineered Y. lipolytica (e.g., YALI17 with

ALK1overexpression). - Media: YPD (20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L peptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, pH 6.5) for pre-culture. Synthetic complete medium without leucine for selection.

- Substrate: 50 mM n-dodecane.

- Bioreactor: 5 L or 50 L system with pH and temperature control.

Procedure:

- Pre-culture: Inoculate a single colony into 20 mL YPD medium. Incubate at 28-30°C with shaking for 48 hours.

- Scale-up: Transfer pre-culture to a larger volume (e.g., 20 mL in a 100 mL flask) of the same medium. Incubate for another 48 hours.

- Bioreactor Fermentation:

- Use a defined medium with controlled pH (optimized to achieve 3.2 mM 1,12-dodecanediol) [3].

- Add 50 mM n-dodecane as the main substrate.

- Maintain optimal dissolved oxygen levels.

- Monitor cell growth and product formation over time.

- Product Extraction & Analysis:

- Centrifuge culture samples to separate cells and supernatant.

- Extract products from the supernatant using an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Analyze diol concentration using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

Protocol 2: Biosynthesis of Branched-Chain Diols from Glucose inE. coli

This protocol describes a general platform for producing structurally diverse C3-C5 diols by expanding amino acid metabolism, demonstrating a novel pathway that combines oxidative and reductive formation of hydroxyl groups [4] [6].

Pathway Design and Plasmid Construction

Objective: Construct a four-step pathway from amino acids to diols.

- Enzymatic Steps:

- Amino Acid Hydroxylase: Oxidative hydroxylation of an amino acid (e.g., L-isoleucine) to form a hydroxyl amino acid. Uses α-ketoglutarate (KG) and O₂ as co-substrates [4] [6].

- L-Amino Acid Deaminase: Deamination of the hydroxyl amino acid to form a hydroxyl α-keto acid.

- α-Keto Acid Decarboxylase: Decarboxylation of the hydroxyl α-keto acid to form a hydroxyl aldehyde.

- Aldehyde Reductase: Reduction of the hydroxyl aldehyde to form the final diol (e.g., IPDO).

Procedure:

- Select appropriate enzymes (e.g., hydroxylase MFL from Methylobacillus flagellatus KT for branched-chain amino acids) [6].

- Codon-optimize genes for expression in E. coli.

- Clone genes into compatible expression plasmids under inducible promoters (e.g., T7 or pBAD).

Strain Cultivation and Diol Production

Materials:

- Strain: Engineered E. coli (e.g., K-12 or BW25113) harboring the diol biosynthetic pathway.

- Media: LB or M9 minimal medium with appropriate antibiotics.

- Inducer: Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) or arabinose, depending on the promoter system.

- Carbon Source: Glucose.

Procedure:

- Strain Cultivation: Grow the engineered E. coli strain in a shake flask or bioreactor with the required carbon source (e.g., glucose) [4].

- Pathway Induction: Add inducer during the mid-exponential growth phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6-0.8) to trigger the expression of the heterologous pathway.

- Process Monitoring: Maintain culture for 24-72 hours post-induction, monitoring cell density and substrate consumption.

- Product Analysis:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation.

- Analyze the culture supernatant for diol production using GC-MS or HPLC. Ten different C3–C5 diols have been successfully synthesized via this route [4].

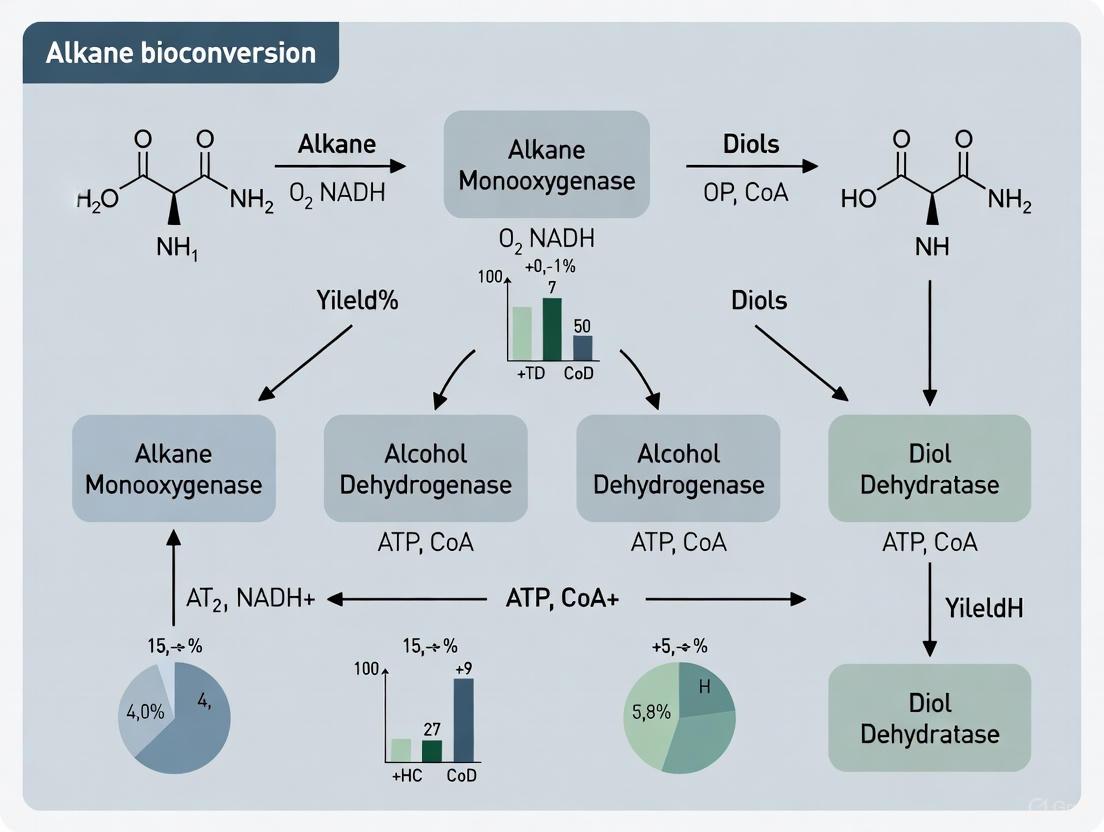

Pathway Visualization and Metabolic Engineering Logic

The microbial production of α,ω-diols from alkanes involves sequential oxidation and protection against over-oxidation. The following diagram illustrates the core metabolic engineering strategy in Yarrowia lipolytica:

Alkane to Diol Bioconversion Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Diol Metabolic Engineering Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted gene knockout in non-model yeasts. | Knocking out ADH and FALDH genes in Y. lipolytica [3]. |

| Alkane Hydroxylase (ALK) | Catalyzes the initial oxidation of alkanes to primary alcohols. | Overexpression of ALK1 in Y. lipolytica to enhance flux from n-dodecane [3]. |

| Carboxylic Acid Reductase (CAR) | Reduces carboxylic acids to aldehydes. | Conversion of 1,12-dodecanedioic acid to 1,12-dodecanediol in E. coli [7]. |

| Amino Acid Hydroxylases | Introduces a hydroxyl group via oxidation of amino acids. | Biosynthesis of branched-chain diols (e.g., IPDO) from amino acids in E. coli [4] [6]. |

| L-Amino Acid Deaminase | Converts L-amino acids to α-keto acids. | Second step in the amino acid-derived diol pathway [4]. |

| α-Keto Acid Decarboxylase | Decarboxylates α-keto acids to aldehydes. | Third step in the amino acid-derived diol pathway [4]. |

| Aldehyde Reductase | Reduces aldehydes to alcohols. | Final step in diol biosynthesis pathways [4] [5]. |

Concluding Remarks

Microbial production of medium- and long-chain α,ω-diols presents a sustainable and economically viable alternative to petrochemical processes. The integration of advanced metabolic engineering strategies—including CRISPR-Cas9, pathway optimization, and the use of robust chassis like Y. lipolytica and P. putida—is key to overcoming challenges such as product toxicity and low titers [1] [3] [2]. Future efforts leveraging synthetic biology, adaptive laboratory evolution, and AI-driven enzyme design are poised to further enhance pathway efficiency and accelerate the commercialization of bio-based diols [1].

Alkane hydroxylases are pivotal biocatalysts that perform the initial and rate-limiting step of alkane activation, inserting a single oxygen atom to convert inert alkanes into primary alcohols. This process transforms abundant hydrocarbon feedstocks into valuable chiral chemicals and polymer precursors, serving as the foundational gateway for downstream bioconversion into high-value products like medium-chain α,ω-diols [3] [8]. These enzymes, including integral membrane di-iron monooxygenases (AlkB) and cytochrome P450 systems, exhibit remarkable regio- and enantioselectivity under mild conditions, a significant advantage over harsh chemical oxidation methods [3] [9]. Their function is critical for sustainable biomanufacturing, enabling the production of biodegradable polyesters and polyurethanes from renewable and waste hydrocarbon resources [3] [6]. This document details the application and characterization of these gatekeeper enzymes within metabolic engineering workflows aimed at diol synthesis.

Performance Metrics of Engineered Alkane Hydroxylase Systems

The efficiency of alkane bioconversion is highly dependent on the host organism, the specific hydroxylase employed, and the metabolic engineering strategy. The table below summarizes recent performance data for diol production from alkanes in various microbial platforms.

Table 1: Performance of microbial platforms for diol production from alkanes

| Host Organism | Engineering Strategy | Key Enzyme(s) | Substrate | Product | Titer | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yarrowia lipolytica YALI17 | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of 14 oxidation pathway genes; ALK1 overexpression | Alk1 (CYP52 P450) | n-Dodecane | 1,12-Dodecanediol | 3.2 mM | [3] |

| Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b | Overexpression of epoxide hydrolase (CcEH) | pMMO/sMMO, CcEH | 1-Propene | (R)-1,2-Propanediol | 251.5 mg/L | [10] |

| Escherichia coli | General oxidative/reductive pathway from amino acids | Amino acid hydroxylase, Decarboxylase, Reductase | Glucose | 10 different C3-C5 diols (e.g., IPDO) | Not Specified | [6] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 33988 | Native system; analysis of gene expression | AlkB1, AlkB2 | Jet fuel (C8-C16) | Fatty Acids (via alcohols) | Growth studies | [11] |

Different alkane hydroxylases possess distinct and sometimes overlapping substrate ranges, which is a critical consideration for pathway design. The following table outlines the substrate specificity of various characterized alkane hydroxylases.

Table 2: Substrate specificity range of different alkane hydroxylases

| Enzyme / System | Source Organism | Reported Substrate Range (Chain Length) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlkB | Pseudomonas putida GPo1 | C5 - C12 | [9] |

| AlkM | Acinetobacter sp. ADP1 | C12 - C16 | [9] |

| CYP52 Family | Yarrowia lipolytica | Broad range (C10-C16) | [3] |

| AlkB1 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 33988 | C12 - C16 | [11] |

| AlkB2 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 33988 | C8 - C16 | [11] |

| LadA | Geobacillus thermodenitrificans | C15 - C36 | [12] |

| AlmA | Acinetobacter sp. | > C32 | [12] |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Engineering Y. lipolytica for 1,12-Dodecanediol Production

This protocol details the metabolic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica to minimize over-oxidation and maximize the flux from n-dodecane to 1,12-dodecanediol [3] [13].

Principle

The native metabolism of Y. lipolytica efficiently oxidizes alkanes to fatty acids via alcohols and aldehydes, preventing diol accumulation. This workflow uses CRISPR-Cas9 to systematically delete genes encoding fatty alcohol oxidase and fatty aldehyde dehydrogenases, thereby blocking the over-oxidation pathway. Concurrently, the native alkane hydroxylase ALK1 is overexpressed to enhance the initial hydroxylation step [3].

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Procedure

Strain Construction

- Knockout of Over-oxidation Genes: Using a CRISPR-Cas9 system for Y. lipolytica (e.g., plasmid pCRISPRyl), sequentially delete the following gene families from the parental Po1g ku70Δ strain [3] [13]:

- Fatty aldehyde dehydrogenases:

FALDH1,FALDH2,FALDH3,FALDH4. - Fatty alcohol oxidase:

FAO1. - Alcohol dehydrogenases:

FADHandADH1throughADH8.

- Fatty aldehyde dehydrogenases:

- This process generates the base engineered strain YALI17 [3].

- Alkane Hydroxylase Overexpression: Clone the ALK1 gene (or other CYP52 genes) into a Y. lipolytica expression vector (e.g., pYl) under a strong constitutive promoter. Transform the construct into the YALI17 strain [13].

- Knockout of Over-oxidation Genes: Using a CRISPR-Cas9 system for Y. lipolytica (e.g., plasmid pCRISPRyl), sequentially delete the following gene families from the parental Po1g ku70Δ strain [3] [13]:

Fermentation and Biotransformation

- Pre-culture: Grow the engineered strain in YPD medium (20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L peptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, pH 6.5) for 2 days [3].

- Production Culture: Scale up the culture in a controlled bioreactor. Use a defined mineral medium with n-dodecane (50 mM) as the sole carbon source. Maintain a controlled pH (optimized to ~6.5) and temperature (28-30°C) [3].

- Monitoring: Sample the culture periodically to monitor cell density and product formation.

Analytical Methods

- Diol Quantification: Analyze culture supernatants using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). Compare retention times and mass spectra with authentic 1,12-dodecanediol standards [3] [12].

- Alkane Consumption: Monitor n-dodecane depletion using GC-MS [12].

Protocol 2: Functional Analysis of Alkane Hydroxylase Substrate Range

This protocol describes a heterologous complementation assay to determine the substrate specificity of novel or engineered alkane hydroxylase genes [9].

Principle

The assay involves expressing a candidate alkB gene in a host strain that possesses the necessary electron transfer proteins (rubredoxin and rubredoxin reductase) but lacks a functional native hydroxylase. The host's ability to grow on alkanes of different chain lengths as the sole carbon source is restored only if the introduced AlkB hydroxylates those specific alkanes [9].

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Procedure

Host and Vector Preparation

- Select a Suitable Host: Use engineered host strains such as E. coli GEc137 or P. putida GPo12 (pGEc47ΔB). These strains contain the alkG (rubredoxin) and alkT (reductase) genes but lack a functional alkB [9].

- Clone the Target Gene: Clone the candidate alkane hydroxylase gene into a compatible expression vector and transform it into the selected host strain. An empty vector serves as a negative control.

Growth Assay

- Plate Preparation: Plate transformed cells on minimal mineral salts medium (e.g., E2 medium) containing no carbon source [9].

- Substrate Provision: Provide n-alkanes of different chain lengths (e.g., C8, C10, C12, C14, C16) as the sole carbon source. For volatile alkanes (C6-C10), place an open container with the alkane inside a sealed container with the plates. For less volatile alkanes (C12+), apply the alkane to a sterile filter disk placed in the lid of the petri dish [9].

- For solid alkanes (C20+), dissolve in a carrier like dioctylphthalate before adding to the medium [9].

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate plates at 30°C for 3-7 days. Observe and score growth compared to the negative control. Robust growth indicates that the AlkB hydroxylase can convert that specific alkane, allowing it to be used as a carbon source.

Protocol 3: Purification of Native AlkB using Liposome Reconstitution

This protocol describes a detergent-free method for partially purifying native, functional AlkB by reconstituting the native membrane of its host organism into liposomes [14].

Principle

Instead of using denaturing detergents, this novel strategy isolates the entire native membrane fraction of the microbe (e.g., Penicillium chrysogenum). The membrane fragments are then reformed into liposomes, which encapsulate AlkB in its native lipid environment, preserving its structure, cofactors, and activity [14].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Membrane Lysate Preparation

- Cell Culture and Harvest: Grow the AlkB-producing strain (e.g., P. chrysogenum SNP5) in a suitable medium with an alkane inducer like hexadecane. Harvest cells by centrifugation [14].

- Lysis and Clarification: Resuspend the cell pellet in lysis buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl with glycerol, PMSF) and disrupt cells using sonication. Remove cell debris and intact cells by low-speed centrifugation. Recover the membrane fraction containing AlkB by ultracentrifugation at high speed (e.g., 7826 g) [14].

Liposome Synthesis via Reverse-Phase Evaporation

- Lipid Extraction: Extract lipids from the membrane pellet using organic solvents like petroleum ether and diethyl ether [14].

- Formation of Water-in-Oil Emulsion: Dissolve the extracted lipids in an organic solvent (e.g., diethyl ether) and mix with the aqueous membrane lysate. Sonicate the mixture to form a stable water-in-oil emulsion [14].

- Liposome Formation: Slowly remove the organic solvent under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator. This process leads to the formation of a lipid gel that subsequently hydrates and forms multilamellar liposomes encapsulating the AlkB enzyme [14].

- Purification: Separate the formed liposomes from non-encapsulated proteins by density gradient centrifugation.

Activity Assay

- Standard Reaction: Set up a reaction mixture containing the liposome preparation, reaction buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 7.5), NADH, and the alkane substrate (e.g., 1-bromooctane) [14].

- Measurement: Monitor the consumption of NADH by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm over time. One unit of AlkB activity is defined as the amount of enzyme required to oxidize 1 μmol of NADH per minute under specified conditions [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and strains for alkane hydroxylase and diol production research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Sources / Strains |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Microbial Hosts | Engineered chassis for pathway expression and bioconversion. | Yarrowia lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ [3]; E. coli GEc137 [9]; P. putida GPo12 [9] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System for Y. lipolytica | Precision genome editing for knocking out competing pathways. | pCRISPRyl vector (Addgene #70007) [13] |

| Alkane Hydroxylase Genes | Key enzymes for the initial activation of alkanes. | ALK1-12 (CYP52) from Y. lipolytica [3]; alkB homologs from P. aeruginosa, A. borkumensis [9] |

| n-Alkane Substrates | Feedstocks for bioconversion; used to test substrate specificity. | n-Octane (C8) to n-Hexadecane (C16) and higher [12] [9] [11] |

| Rubredoxin (AlkG) & Reductase (AlkT) | Essential electron transfer partners for supporting AlkB activity in heterologous hosts. | Co-expressed from the P. putida GPo1 OCT plasmid or similar systems [9] [8] |

| Analytical Standards | Quantification and identification of reaction products. | 1,12-Dodecanediol [3]; (R)-1,2-Propanediol [10]; other diol isomers |

Visualization of the AlkB Enzyme Complex Mechanism

Recent structural insights, particularly from cryo-EM studies of the Fontimonas thermophila AlkB-AlkG fusion complex, have elucidated the molecular mechanism of substrate binding and electron transfer [8].

The diagram illustrates the coordinated mechanism: the alkane substrate (e.g., dodecane, D12) enters AlkB's hydrophobic channel from the lipid bilayer, stabilizing at the di-iron active site. Molecular dynamics simulations show this binding allosterically strengthens the interaction between AlkB and its electron transfer partner, rubredoxin (AlkG), enhancing the efficiency of electron flow from NADH (via AlkT and AlkG) to activate oxygen and catalyze terminal hydroxylation [8]. Key hydrophobic residues (e.g., L263, L264, I267) line the substrate channel and facilitate translocation [8].

In the pursuit of sustainable chemical production, microbial biosynthesis of diols presents a promising alternative to petroleum-based refineries. A critical strategic decision in this field lies in the choice of microbial chassis, pivoting on the fundamental comparison between native and engineered production capabilities. Some microorganisms possess innate metabolic pathways to produce specific diols, while advanced metabolic engineering can equip non-native hosts with entirely new biosynthetic capacities. This application note, framed within broader research on alkane bioconversion to diols, provides a structured comparison of native versus engineered diol production across various microbial hosts. It summarizes key quantitative data and delivers detailed experimental protocols to guide researchers and scientists in selecting and optimizing microbial platforms for efficient diol biosynthesis.

Performance Comparison: Native vs. Engineered Hosts

The table below summarizes the reported production of various diols, highlighting the chassis, its native or engineered status, and key performance metrics.

Table 1: Diol Production in Native and Engineered Microbial Hosts

| Diol Product | Microbial Host | Production Status | Carbon Source | Titer | Yield | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-methylpentane-2,3-diol | Escherichia coli | Engineered | Glucose | 15.3 g/L (129.8 mM) | 72% (theoretical) | [15] |

| 1,12-dodecanediol | Yarrowia lipolytica (YALI17) | Engineered | n-Dodecane | 3.2 mM | 29-fold increase over wild type | [13] [3] |

| 1,12-dodecanediol | Yarrowia lipolytica (Wild Type) | Native | n-Dodecane | 0.05 mM | Not Reported | [13] [3] |

| 1,6-hexanediol | E. coli & P. putida (Co-culture) | Engineered | n-Hexane | 5 mM | 61.5x one-stage process | [16] |

| (R)-1,2-propanediol | Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b | Engineered | 1-Propene | 251.5 mg/L | Not Reported | [10] |

| 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BDO) | Various (e.g., K. pneumoniae) | Native | Glucose | Not Specified | Not Specified | [5] |

| 1,4-butanediol (1,4-BDO) | Escherichia coli | Engineered | Glucose | 18 g/L | Not Specified | [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Engineering Strategies

Protocol 1: Engineering anE. coliPlatform for Branched-Chain β,γ-Diols

This protocol details the creation of an E. coli chassis for de novo production of branched-chain diols from glucose, achieving high-tier production of 4-methylpentane-2,3-diol [15].

- 1. Principle: A recursive carboligation cycle is established in E. coli by integrating the branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism with a promiscuous acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS). The AHAS catalyzes the condensation of branched-chain aldehydes with pyruvate to form α-hydroxyketones, which are subsequently reduced by aldo-keto reductases (AKRs) to yield the target β,γ-diols [15].

- 2. Key Reagents and Strains:

- Host Strain: Escherichia coli chassis (e.g., BL21 or other suitable production strain).

- Plasmids: Expression vectors for genes of the biosynthetic pathway.

- Enzymes: Acetohydroxyacid synthase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Ilv2c, truncated) [15].

- Media: Minimal media with glucose as the primary carbon source.

- 3. Procedure:

- Pathway Design: Construct a biosynthetic pathway that links the BCAA metabolism to diol production. The pathway should start from pyruvate and involve enzymes for aldehyde generation, carboligation, and final reduction.

- Gene Expression: Express the following key elements in the E. coli host:

- Genes for the BCAA pathway to generate branched-chain aldehydes.

- The gene for Ilv2c to catalyze the condensation of aldehydes with pyruvate.

- Genes for aldo-keto reductases (AKRs) or secondary alcohol dehydrogenases (sADHs) to reduce α-hydroxyketones to diols.

- Systematic Optimization: Optimize the BCAA pathway flux by modulating gene expression levels, knocking out competing pathways, and enhancing cofactor supply.

- Fed-Batch Fermentation: Scale up production using fed-batch fermentation conditions. Monitor glucose consumption and product formation over time (e.g., up to 144 hours) [15].

- 4. Analysis: Quantify diol production using methods such as GC-MS or HPLC. Calculate the titer, yield, and specificity of the target diol.

The following diagram illustrates the core metabolic pathway engineered into E. coli for the production of branched-chain β,γ-diols.

(core pathway for branched-chain diol production in e. coli)

Protocol 2: Metabolic Engineering ofY. lipolyticafor α,ω-Diols from Alkanes

This protocol describes the enhancement of Y. lipolytica for the production of medium- to long-chain α,ω-diols directly from alkanes, such as n-dodecane, by blocking competing oxidation pathways [13] [3].

- 1. Principle: The oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica naturally metabolizes hydrophobic substrates like alkanes but possesses efficient oxidation pathways that convert alcohol intermediates to fatty acids, limiting diol accumulation. This strategy uses CRISPR-Cas9 to delete genes responsible for this over-oxidation, thereby redirecting flux toward diol production [13] [3].

- 2. Key Reagents and Strains:

- Host Strain: Yarrowia lipolytica Po1g.

- Plasmids: pCRISPRyl vector or similar for CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in Y. lipolytica [13].

- Media: YPD or synthetic complete medium for routine growth; n-dodecane as a substrate in production phase.

- 3. Procedure:

- Strain Engineering (Gene Deletions):

- Pathway Enhancement (Gene Overexpression):

- To enhance the primary hydroxylation step, overexpress an alkane hydroxylase gene (e.g., ALK1) in the engineered base strain [13].

- Fermentation:

- Cultivate the engineered strain in a bioreactor under pH-controlled conditions.

- Use n-dodecane (e.g., 50 mM) as the primary substrate for biotransformation.

- Monitor diol production over the course of the fermentation.

- 4. Analysis: Quantify 1,12-dodecanediol production using analytical methods like GC or HPLC. Compare the titer with the wild-type strain to calculate the fold improvement.

The workflow below outlines the key steps in engineering Y. lipolytica for enhanced diol production from alkanes.

(engineering workflow for y. lipolytica diol production)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Microbial Diol Production

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| pCRISPRyl Vector | CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in Yarrowia lipolytica [13]. | Enables precise deletion of multiple genes, such as those in fatty alcohol oxidation pathways. |

| Acetohydroxyacid Synthase (AHAS) | Catalyzes C-C bond formation between aldehydes and pyruvate [15]. | Truncated Ilv2c from S. cerevisiae shows high activity for branched-chain aldehydes. |

| Aldo-Keto Reductases (AKRs) | Reduces α-hydroxyketones to form diols [15]. | Used in the final step of the β,γ-diol biosynthetic pathway in E. coli. |

| Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenase | Hydroxylation of alkanes to primary alcohols [13] [3]. | ALK1 from Y. lipolytica is a key enzyme for initiating alkane conversion. |

| Terminal Thioreductase (TR) | Terminates polyketide chains by reductive cleavage to produce aldehydes [17]. | Found in PKS platforms; produces aldehyde intermediates for diol, amino alcohol, and acid production. |

| Epoxide Hydrolase (EH) | Converts epoxides to vicinal diols [10]. | Used in methanotrophs for chiral diol production (e.g., from Caulobacter crescentus). |

The comparative data and protocols presented herein clearly demonstrate that while native producers offer a starting point, strategic metabolic engineering is pivotal for unlocking high-efficiency, scalable diol production. The choice between chassis, such as the versatile E. coli for defined pathway engineering or the inherently robust Y. lipolytica for alkane conversion, depends on the target diol's structure and the desired feedstock. Future advancements will likely involve integrating these strategies with systems metabolic engineering and AI-driven design to further enhance titers, yields, and productivity, fully realizing the potential of microbial cell factories for sustainable diol production.

In the metabolic engineering of microorganisms for alkane bioconversion, over-oxidation represents a critical bottleneck that severely limits the yield of target products, including valuable diols. This process involves the unintended further oxidation of intermediate compounds, diverting metabolic flux away from the desired pathway and reducing overall process efficiency. In native metabolic pathways, endogenous microbial enzymes actively compete for aldehyde intermediates, rapidly converting them to fatty alcohols or carboxylic acids instead of allowing their channeling toward diol synthesis [18] [19]. This challenge is particularly pronounced in engineered E. coli systems, where multiple endogenous aldehyde reductases exhibit high activity toward fatty aldehydes, significantly limiting the substrate pool available for the production of alkanes and subsequently diols [18]. Overcoming this bottleneck requires sophisticated metabolic engineering strategies, including the deletion of competing enzymes, fine-tuning of pathway expression, and implementation of novel pathways to bypass native metabolic constraints.

Quantitative Analysis of Pathway Bottlenecks and Engineering Solutions

Table 1: Key Enzymes Contributing to Over-oxidation in Alkane Bioconversion Pathways

| Enzyme | Source Organism | Function | Effect on Pathway | Kinetic Parameters (if available) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldehyde reductase (YqhD) | E. coli (native) | Converts fatty aldehydes to fatty alcohols | Competes with ADO for aldehydes, reduces alkane yield [18] | Not specified |

| Alkane mono-oxygenase (AlkB) | Pseudomonas putida GPo1 | Oxidizes alkanes to 1-alkanols | Can overoxidize to carboxylic acids, bypassing alcohol dehydrogenase [19] | Not specified |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase (AlkH) | Pseudomonas putida GPo1 | Oxidizes aldehydes to carboxylic acids | Contributes to overoxidation of alcohols to acids [19] | Not specified |

| Acyl-CoA synthetase (AlkK) | Pseudomonas putida GPo1 | Activates fatty acids to acyl-CoAs | Channels products toward β-oxidation, away from diol production [19] | Not specified |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase (PsADH) | Pantoea sp. 7-4 | Oxidizes 1-tetradecanol to tetradecanal | Can help recycle alcohol by-products back toward alkanes [18] | kcat/Km (oxidation): 171 s⁻¹·mM⁻¹; kcat/Km (reduction): 586 s⁻¹·mM⁻¹ |

Table 2: Impact of Gene Deletion on Over-oxidation Byproducts

| Genetic Modification | Substrate | Result | Implication for Diol Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deletion of yqhD (aldehyde reductase) | Fatty aldehydes | ~2-fold increase in alkane titer [18] | Increases aldehyde availability for diol pathways |

| Removal of alkH and alkK from alk operon | n-dodecane | Aldehyde proportion increased from 2% to 10% of oxidized products; carboxylic acids still dominant (77%) [19] | Suggests AlkB may directly produce acids; complete elimination challenging |

| Deletion of 13 aldehyde reductase genes in E. coli | Fatty aldehydes | 90% reduction in endogenous alcohol accumulation [18] | Significant but incomplete reduction in competing reactions |

Experimental Protocols for Studying and Overcoming Over-oxidation

Protocol: Assessing Over-oxidation in Alkane Bioconversion Systems

Purpose: To quantify over-oxidation products and identify key enzymatic bottlenecks in alkane-to-diol conversion pathways.

Materials:

- Engineered E. coli strains expressing alkane oxidation genes

- Minimal medium with appropriate carbon sources

- Alkane substrates (C8-C16)

- GC-MS system for product quantification

- Protein purification system for enzyme characterization

Procedure:

- Cultivate engineered E. coli strains in controlled bioreactors (37°C, pH 7.0) with alkane substrates [19].

- Sample culture broth at regular intervals over 20 hours.

- Extract metabolites using ethyl acetate or other appropriate solvents.

- Analyze extracts by GC-MS to quantify alkane, alcohol, aldehyde, and acid concentrations.

- Calculate specific yields (g product/g dry cell weight) and product distributions.

- Compare product profiles between strains with and without competing enzymes (e.g., ΔalkH, ΔalkK).

- For enzyme-level analysis, purify relevant enzymes and determine kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) for oxidation and reduction reactions [18].

Expected Outcomes: This protocol enables quantification of over-oxidation byproducts and identification of the major enzymatic steps responsible for product loss. The data obtained can guide targeted metabolic engineering interventions.

Protocol: Implementing a Transporter-Enhanced Bioconversion System

Purpose: To overcome substrate uptake limitations that exacerbate over-oxidation issues by ensuring efficient alkane delivery to engineered pathways.

Materials:

- E. coli strains expressing alkane hydroxylase complex (AlkB,F,G,T)

- Plasmids with and without alkL gene

- n-dodecane or other alkane substrates

- Controlled-expression vector for toxic transporters

Procedure:

- Transform E. coli with plasmids containing the minimal alkane oxidation genes (alkB,F,G,T) with and without the alkL transporter gene [19].

- Cultivate strains in appropriate media with inducers for controlled gene expression.

- Incubate with C8-C16 alkane substrates for 20 hours.

- Extract and quantify intracellular alkanes and oxidation products.

- Compare oxidation rates and product profiles between strains with and without AlkL.

- For toxic transporters like AlkL, use controlled induction to balance expression and host fitness.

Expected Outcomes: Strains expressing AlkL should show significantly enhanced uptake of >C12 alkanes and improved oxidation product yields (up to 100-fold improvement reported) [19].

Visualization of Metabolic Bottlenecks and Engineering Solutions

Diagram 1: Metabolic bottlenecks and solutions in alkane to diol conversion.

Diagram 2: Systematic workflow to overcome over-oxidation bottlenecks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Over-oxidation

| Reagent/Component | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| AlkL transporter protein | Enhances uptake of C7-C16 n-alkanes | Improved intracellular alkane availability for oxidation; increased specific yields up to 100-fold for >C12 alkanes [19] |

| PsADH (Alcohol dehydrogenase from Pantoea sp. 7-4) | Oxidizes 1-tetradecanol to tetradecanal | Recycles alcohol byproducts back to aldehydes for alkane production; enables alcohol-to-alkane pathway [18] |

| Aldehyde-deformylating oxygenase (ADO) | Converts fatty aldehydes to alkanes | Key enzyme in alkane production pathway; requires aldehyde substrates competed for by endogenous reductases [18] |

| Controlled-expression vectors | Regulates expression of toxic genes | Enables balanced expression of toxic components like AlkL; 10-fold improvement in oxidation yields reported [19] |

| Alkane hydroxylase complex (AlkB,G,T) | Oxidizes alkanes to 1-alkanols | Initial oxidation step in alkane degradation; potential source of over-oxidation to acids [19] |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Quantifies metabolic intermediates | Essential for analyzing alkane, alcohol, aldehyde, and acid concentrations in engineered strains [18] |

Advanced Engineering Strategies: CRISPR, Pathway Design, and Platform Technologies

CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Genome Editing for Blocking Competing Pathways

In metabolic engineering, the high-flux conversion of substrates into desired products is often hindered by native metabolic pathways that compete for precursors and energy. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing provides a powerful, precise method for disrupting these competing pathways, thereby redirecting metabolic flux toward the target product. Within the context of alkane bioconversion to diols, this approach is particularly valuable. The oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica naturally possesses efficient enzymes for alkane oxidation but also contains multiple pathways that over-oxidize valuable alcohol and aldehyde intermediates into fatty acids, thereby reducing diol yields [3]. This application note details protocols for using CRISPR-Cas9 to systematically block these competing oxidation pathways, enabling the efficient production of medium- to long-chain α,ω-diols from alkane feedstocks.

Strain Engineering and Diol Production Enhancement

Systematic gene knockout of competing oxidative pathways in Yarrowia lipolytica leads to significant improvements in diol production. The following table summarizes the key genotypic modifications and their quantitative impact on 1,12-dodecanediol production from n-dodecane.

Table 1: Engineered Yarrowia lipolytica Strains and Diol Production Performance

| Strain | Genotype Description | Key Genetic Modifications | 1,12-Dodecanediol Production (mM) | Fold Increase vs. Wild Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | Po1g ku70Δ | Parental strain | 0.05 [3] | 1x |

| YALI6 | β-oxidation + fatty aldehyde oxidation blocked | mfe1Δ faa1Δ faldh1-4Δ |

Data not provided [3] | - |

| YALI17 | β-oxidation + full alcohol & aldehyde oxidation blocked | mfe1Δ faa1Δ faldh1-4Δ fao1Δ fadhΔ adh1-8Δ [3] |

0.72 [3] | 14x |

| YALI17 + ALK1 | YALI17 with Alk1 monooxygenase overexpression | YALI17 background + ALK1 overexpression [3] |

1.45 [3] | 29x |

| YALI17 + ALK1 (pH-controlled) | YALI17 with ALK1 under optimized fermentation | Strain YALI17 + ALK1, controlled pH biotransformation [3] |

3.20 [3] | 64x |

Targeted Genes for Blocking Competing Pathways

The efficient synthesis of diols from alkanes requires blocking the over-oxidation of fatty alcohol and fatty aldehyde intermediates. The following table lists the primary gene targets in Y. lipolytica for this purpose.

Table 2: Key Gene Targets for Blocking Competing Oxidation Pathways in Y. lipolytica

| Target Category | Gene(s) | Gene Function | Effect of Deletion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Alcohol Oxidation | FADH |

Fatty alcohol dehydrogenase | Prevents oxidation of fatty alcohols to fatty aldehydes [3] |

ADH1-8 |

Multiple alcohol dehydrogenases | Reduces capacity for alcohol oxidation [3] | |

FAO1 |

Fatty alcohol oxidase | Blocks alternative oxidative route for alcohols [3] | |

| Fatty Aldehyde Oxidation | FALDH1-4 |

Fatty aldehyde dehydrogenases | Prevents oxidation of fatty aldehydes to fatty acids [3] |

| β-Oxidation | mfe1, faa1 |

Key β-oxidation pathway genes | Channels flux away from full degradation of fatty acids [3] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Multiplexed sgRNA Vector Construction for Pathway Engineering

This protocol describes the construction of a CRISPR-Cas9 vector for simultaneous disruption of multiple genes within the fatty alcohol and aldehyde oxidation pathways [3].

1. sgRNA Design and Cloning

- Design: Select 20-base guide sequences targeting the open reading frames of

FADH,ADH1-8,FAO1, andFALDH1-4using online tools (e.g., CHOPCHOP). Ensure each sgRNA has minimal predicted off-target activity [20]. - Cloning: Clone sgRNA sequences into an expression plasmid containing a Cas9 nuclease and a selectable marker (e.g., puromycin resistance) for subsequent selection [20]. Multiple sgRNA scaffolds can be linked within a single vector [3].

2. hPSC Culture and Transfection (Illustrative Example)

- Cell Culture: Maintain and passage human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) in feeder-free conditions. Ensure cells are healthy and at an optimal density (e.g., 50-70% confluent) for transfection [20].

- Delivery: Transfect the constructed plasmid into hPSCs using an appropriate method (e.g., lipofection, electroporation). Include a marker gene (e.g., GFP) to assess transfection efficiency [20].

3. Isolation and Validation of Knockout Clones

- Selection: At 48 hours post-transfection, begin antibiotic selection (e.g., puromycin) to eliminate non-transfected cells. Continue selection for 5-7 days [20].

- Single-Cell Cloning: Isolate single-cell clones and expand them.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells from each clone and extract genomic DNA using a standard silica-column or salt-precipitation method [20].

- Genotype Validation: Perform PCR amplification of the targeted genomic regions and analyze products by Sanger sequencing to confirm the presence of indel mutations that disrupt gene function [20].

Protocol: Precision Genome Editing via RNP Electroporation with ssODN Donor

This protocol utilizes Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for high-efficiency, precise editing with reduced off-target effects, suitable for introducing specific point mutations or small insertions [20].

1. In Vitro Formation of Cas9 RNP Complexes

- Complex Assembly: Combine purified Cas9 protein with synthetically produced, target-specific sgRNA in a molar ratio of 1:2 (Cas9:sgRNA). Incubate at 25°C for 10-30 minutes to form active RNP complexes [20] [21].

2. Design and Preparation of ssODN Repair Template

- Template Design: Synthesize a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) repair template. The template should be at least 60-100 nucleotides long, with the desired edit (e.g., a premature stop codon) flanked by homologous arms (30-50 bases each) complementary to the sequence surrounding the Cas9 cut site [20].

3. Co-delivery of RNP and ssODN via Electroporation

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and resuspend the target cells (e.g., hPSCs) in an electroporation buffer.

- Electroporation: Mix the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complexes and the ssODN repair template. Electroporate the mixture using a manufacturer-optimized program for the specific cell type [20].

4. Screening for Precise Edits

- Initial Screening: Use droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) or restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assays to rapidly screen a pool of edited cells for the presence of the desired edit [20].

- Clone Validation: Isolate single-cell clones and confirm the precise incorporation of the edit via Sanger sequencing of the targeted genomic locus [20].

Metabolic Pathway Engineering Strategy

The following diagram illustrates the competing metabolic pathways in Y. lipolytica and the strategic blocking of oxidation genes to enhance diol production from alkanes.

Experimental Workflow for Strain Development

This workflow outlines the key steps for creating and validating a high-diol-producing strain using CRISPR-Cas9.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for CRISPR-Cas9 Pathway Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example or Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | RNA-guided endonuclease that creates double-strand breaks in target DNA [22]. | Can be delivered as plasmid DNA, mRNA, or purified protein (RNP) [20]. |

| sgRNA | Synthetic guide RNA that directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus [20]. | Can be produced via in vitro transcription or purchased as synthetic RNA [20]. |

| Repair Template | DNA template for introducing specific edits via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [20]. | For small edits: single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN). For large inserts: double-stranded DNA plasmid [20]. |

| Delivery Vehicle | Method for introducing editing components into cells. | Includes electroporation, lipofection, or viral vectors (lentivirus, AAV) [20]. |

| Selection Marker | Allows for enrichment of successfully transfected/transduced cells. | Antibiotic resistance (e.g., Puromycin), fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP) [20]. |

| Cell Culture Media | Supports the growth and maintenance of the target cell line. | Specific to the host organism (e.g., YPD for Y. lipolytica, specialized media for hPSCs) [3] [20]. |

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Minimizing Off-Target Effects: Utilize computational tools for sgRNA design to predict and minimize off-target activity [23]. Employ high-fidelity Cas9 variants or RNP delivery, which has been shown to reduce off-target effects compared to plasmid-based delivery [20] [22].

- Optimizing HDR Efficiency: To enhance the efficiency of precise editing, consider using small molecule modulators of DNA repair pathways (e.g., RS-1 to promote HDR) or synchronizing cells to the S/G2 phases of the cell cycle where HDR is more active [22].

- Addressing Delivery Challenges: For difficult-to-transfect cell types, optimize electroporation parameters or test different viral vector systems. The use of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) is also an emerging and promising delivery method, particularly for in vivo applications [24].

The selective functionalization of inert C-H bonds represents a significant challenge in synthetic chemistry. P450 monooxygenases and hydroxylases have emerged as powerful biocatalysts that perform this transformation with remarkable regio- and stereoselectivity under mild conditions [25] [26]. These enzymes are pivotal in the bioconversion of inexpensive alkane feedstocks into valuable diol precursors for polymers, pharmaceuticals, and fine chemicals [13] [3]. This Application Note details experimental protocols and engineering strategies for enhancing the activity of these enzyme systems within microbial hosts, specifically focusing on alkane bioconversion to diols—a key objective in metabolic engineering research.

Key Engineering Strategies and Performance Data

Table 1: Metabolic engineering strategies for enhanced diol production in microbial systems.

| Host Organism | Engineering Strategy | Key Enzymes Overexpressed | Substrate | Product | Titer | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yarrowia lipolytica (YALI17) | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of 10 ADH and 4 FALDH genes; ALK1 overexpression [13] | Cytochrome P450 ALK1 (CYP52) | n-Dodecane | 1,12-Dodecanediol | 1.45 mM | 29-fold vs. WT [13] |

| Yarrowia lipolytica (YALI17, pH-controlled) | Combined pathway blocking and bioprocess optimization [13] | Cytochrome P450 ALK1 (CYP52) | n-Dodecanedioic acid | 1,12-Dodecanediol | 3.2 mM | 64-fold vs. WT [13] |

| Escherichia coli | General pathway combining oxidative and reductive OH-group formation [6] | Amino acid hydroxylases, decarboxylases, reductases | Glucose | 10 different C3-C5 diols (e.g., IPDO, 2-M-1,3-BDO) | N/A | 6 novel diols [6] |

| Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b | Overexpression of heterologous epoxide hydrolase [10] | Methane Monooxygenase (MMO), Epoxide Hydrolase (CcEH) | 1-Propene | (R)-1,2-Propanediol | 251.5 mg/L | N/A [10] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Microenvironment engineering: CPR co-expression, NADPH supply, ER expansion [27] | Cytochrome P450s for diterpenoid synthesis | Engineered for de novo production | 11,20-Dihydroxyferruginol | 67.69 mg/L | 42.1-fold vs. base strain [27] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for P450 and hydroxylase engineering experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| pCRISPRyl Vector | CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in Y. lipolytica [13] | Addgene #70007; used for multiplexed gene knockouts. |

| Alkane Hydroxylases (ALK1-12) | Primary oxidation of n-alkanes to alcohols [13] | CYP52 family P450s from Y. lipolytica; ALK1 particularly effective. |

| δ-Aminolevulinic acid (δ-ALA) | Heme precursor to enhance P450 expression [28] | Used at 0.1 mM in E. coli fermentations to boost P450 activity. |

| Heterologous Redox Partners (CPR) | Electron transfer to eukaryotic P450s [27] [28] | Co-expression of NADPH-Cytochrome P450 Reductase (CPR) is often essential. |

| NADPH Regeneration System | Sustains P450 catalytic cycle [25] | e.g., Glucose-6-phosphate + G6PDH; critical for in vitro assays. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Multiplexed Gene Knockout inY. lipolytica

Objective: To systematically delete genes involved in the over-oxidation of fatty alcohols and aldehydes to enhance diol accumulation [13] [3].

Materials:

- pCRISPRyl plasmid (Addgene #70007)

- E. coli DH5α for cloning

- Y. lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ strain

- Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with ampicillin (100 mg/L)

- YPD medium (20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L peptone, 10 g/L yeast extract)

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design and Vector Construction:

- Design 20 bp guiding sequences targeting genes of interest (e.g., FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1, FALDH1-4).

- For multiplexed targeting, insert a second sgRNA scaffold sequence downstream of the original site in pCRISPRyl.

- Clone the guiding sequences upstream of each sgRNA scaffold using overlapping PCR.

- Transform the PCR product into E. coli DH5α, then purify and sequence-verify the plasmid.

- Yeast Transformation and Strain Selection:

- Introduce the constructed pCRISPRyl plasmid into competent Y. lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ cells.

- Plate transformations on synthetic complete medium without leucine and incubate at 28-30°C for 2-3 days.

- Select and validate positive clones by colony PCR and sequencing to confirm gene deletions.

Protocol 2: Overexpression of P450 Alkane Monooxygenases

Objective: To enhance the first step of alkane oxidation by overexpressing alkane hydroxylase genes (e.g., ALK1) in engineered Y. lipolytica [13].

Materials:

- pYl yeast expression vector

- Y. lipolytica engineered strain (e.g., YALI17 with oxidation pathways blocked)

Procedure:

- Gene Amplification and Cloning:

- PCR-amplify the ALK1 gene (or other ALK genes) from Y. lipolytica genomic DNA.

- Clone the amplified gene into the pYl expression vector using Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC).

- The pYl vector should contain a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., TEF) with an intron sequence to enhance expression.

- Strain Cultivation and Biotransformation:

- Grow the engineered Y. lipolytica strain in YPD or synthetic complete medium at 28-30°C.

- For biotransformation, scale up cultures to 20 mL in 100 mL flasks.

- Add filter-sterilized n-dodecane (or other alkane substrates) to a final concentration of 50 mM.

- To maximize production, perform biotransformation under automated pH-controlled conditions.

Protocol 3: Whole-Cell Biocatalysis for Chiral Diol Production in Methanotrophs

Objective: To produce enantiomerically pure vicinal diols from alkenes using engineered Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b [10].

Materials:

- Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b strains

- Nitrate mineral salts (NMS) medium

- Methane gas (CH₄)

- Epoxide Hydrolase (EH) gene from Caulobacter crescentus (or other sources)

Procedure:

- Strain Engineering:

- Overexpress the epoxide hydrolase (EH) gene in M. trichosporium OB3b via electroporation.

- The endogenous Methane Monooxygenase (MMO) will convert alkenes to epoxides, which EHs then hydrolyze to diols.

- Biotransformation and Process Optimization:

- Cultivate the recombinant methanotroph in NMS medium under a methane/air (1:1) atmosphere.

- For diol production, add the alkene substrate (e.g., 1-propene) to the culture.

- Optimize key process parameters: maintain pH at 7.0, temperature at 30°C, and provide sufficient copper (10 µM) for MMO activity.

- Monitor product formation via HPLC.

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

Metabolic Pathway for Alkane to Diol Conversion in EngineeredY. lipolytica

The following diagram illustrates the engineered metabolic pathway for the production of 1,12-dodecanediol from n-dodecane in Yarrowia lipolytica, highlighting the key overexpression and knockout targets.

Experimental Workflow for Strain Development and Biotransformation

This workflow outlines the key steps for developing an engineered microbial biocatalyst and performing alkane bioconversion to diols.

The strategic overexpression of P450 monooxygenases and hydroxylases, coupled with the systematic removal of competing metabolic pathways, provides a robust framework for enhancing the microbial production of diols from alkanes. The protocols detailed herein—encompassing CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing, P450 overexpression, and whole-cell biocatalysis—offer researchers a validated roadmap for engineering efficient microbial cell factories. The application of these methods, supported by the accompanying reagent solutions and analytical workflows, can significantly accelerate the development of sustainable bioprocesses for producing high-value diol precursors, aligning with the growing demand for green and sustainable chemical manufacturing.

The sustainable production of industrial chemicals increasingly relies on microbial cell factories. Medium- and branched-chain diols, serving as valuable solvents, polymer building blocks, and pharmaceutical intermediates, are prime candidates for bio-based manufacturing [29]. However, their efficient microbial synthesis, particularly for non-natural structures, remains a significant challenge. This application note explores the development and implementation of polyketide synthase (PKS) platforms as a versatile and powerful solution for the biosynthesis of non-natural diols, framing this emerging technology within the established field of alkane bioconversion to diols.

Traditional metabolic engineering for diol production often struggles with the extensive genetic redesign required for each new target molecule. The PKS platform technology overcomes this limitation by harnessing the modularity of these biological assembly lines. By rearranging defined enzymatic domains, researchers can create a wide array of custom diols and related chemicals from renewable resources, offering a sustainable alternative to petroleum-derived synthesis routes [30].

Engineering Strategies for PKS Diversification

Platform Architecture and Termination Chemistry

The core innovation of modern PKS platforms for diol production lies in their engineered modularity. A platform developed in Streptomyces albus exemplifies this approach, utilizing a versatile loading module from the rimocidin PKS combined with different extension modules [29]. A key engineering feat involves the replacement of the standard terminating thioesterase domain with a thioreductase (TR). This critical swap changes the final output from a carboxylic acid to an aldehyde, a much more flexible intermediate [30].

The resulting aldehyde serves as a central branch point for further functionalization. Expression of specific downstream enzymes enables the selective production of diverse chemical families:

- Diols: Produced via reduction of the aldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenases.

- Amino Alcohols: Generated through transamination of the aldehyde by specific transaminases.

- Hydroxy Acids: Formed by oxidation of the aldehyde [29].

This platform's versatility was demonstrated by the production of at least 17 distinct diols, amino alcohols, and hydroxy acids, 13 of which were new-to-nature molecules [30].

Acyltransferase Swapping for Branching

To access even greater structural diversity, particularly branched-chain molecules, the platform allows for Acyltransferase (AT) domain swapping. Replacing the native malonyl-CoA-specific AT domain with ATs specific for methylmalonyl-CoA or ethylmalonyl-CoA introduces methyl or ethyl branches, respectively, into the growing polyketide chain. This enables the high-titer production of branched-chain diols and amino alcohols, significantly expanding the accessible chemical space from this single biosynthetic system [29].

Table 1: Engineered PKS Platform Outputs and Performance

| Product Class | Example Products | Key Engineering Feature | Titer Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Diols | 1,3-Propanediol, 1,5-Pentanediol | Thioreductase termination + Alcohol Dehydrogenase | High titers reported [29] |

| Branched Diols | 2-Ethyl-1,3-hexanediol | Acyltransferase swapping + Branching | High titers reported [29] |

| Amino Alcohols | 5-Aminopentan-1-ol | Thioreductase termination + Transaminase | High titers reported [29] |

| Hydroxy Acids | 5-Hydroxypentanoic acid | Thioreductase termination + Aldehyde Oxidase | High titers reported [29] |

Protocol: Implementing a PKS Platform for Diol Production

This protocol outlines the key steps for establishing a PKS-based biosynthetic platform for non-natural diols in a microbial host, based on the system developed in Streptomyces albus [30] [29].

Strain and Vector Construction

Materials:

- Host Strain: Streptomyces albus or other suitable host (e.g., Bacillus amyloliquefaciens for other natural products [31]).

- Expression Vector: A high-copy number vector with strong, constitutive promoter (e.g., native ermE promoter).

- PKS Genes: Codon-optimized genes for the desired PKS modules.

- Heterologous Enzymes: Codon-optimized genes for thioreductase, alcohol dehydrogenases, and/or transaminases.

Procedure:

- Design PKS Assembly: Select a loading module (e.g., from rimocidin PKS) and an extension module. For branched chains, incorporate an AT domain specific for methylmalonyl-CoA or ethylmalonyl-CoA.

- Incorporate Termination Domain: Clone a thioreductase (TR) gene in place of the native thioesterase gene at the terminus of the PKS gene cluster to produce an aldehyde intermediate.

- Assemble Pathway Modules: Clone the engineered PKS construct and genes for downstream enzymes (e.g., alcohol dehydrogenase for diols) into the expression vector.

- Note: Use techniques like Golden Gate assembly or transformation-associated recombination (TAR) for large DNA constructs.

- Transform Host Strain: Introduce the final construct into the chosen microbial host via electroporation or conjugation.

Fermentation and Analysis

Materials:

- Fermentation Medium: Suitable rich or defined medium (e.g., YPD for Y. lipolytica [13]).

- Extraction Solvent: Ethyl acetate or chloroform/methanol.

- Analysis: GC-MS or LC-MS system.

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Pick a single colony into 10 mL of medium and incubate with shaking (e.g., 250 rpm) at 30°C for 48 hours.

- Production Fermentation: Transfer the inoculum (1-10% v/v) into fresh medium in a baffled flask. Incubate with shaking for 96-120 hours.

- Sample Extraction:

- Take 1 mL of culture broth and extract with an equal volume of ethyl acetate.

- Vortex vigorously for 1 minute and centrifuge at 13,000 x g for 5 minutes.

- Transfer the organic (upper) layer to a new vial for analysis.

- Product Quantification:

- Analyze samples by GC-MS or LC-MS.

- Use pure commercial standards of the target diols for calibration and retention time identification.

Integration with Alkane Bioconversion Pathways

The PKS platform for diol synthesis presents a complementary strategy to direct alkane bioconversion within the broader metabolic engineering landscape. The oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica has been successfully engineered as a cell factory for converting alkanes like n-dodecane into medium-chain α,ω-dioles, such as 1,12-dodecanediol [13] [3]. This was achieved by blocking over-oxidation pathways using CRISPR-Cas9 to delete genes involved in fatty alcohol and aldehyde oxidation, and simultaneously overexpressing alkane hydroxylase genes like ALK1 [13].

While the Y. lipolytica approach utilizes and optimizes the host's native alkane oxidation machinery, the PKS platform offers a parallel, highly tunable route to a diverse range of diol structures that may be difficult or inefficient to produce via alkane hydroxylation alone. The two approaches can be conceptualized as part of a unified metabolic engineering toolkit for diol production, from simple hydrocarbon feedstocks to complex, branched molecules. Future efforts may focus on integrating these strategies, for example, by using alkane-derived intermediates as primers for engineered PKS systems.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the direct alkane bioconversion pathway and the synthetic PKS platform for diol production.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PKS and Metabolic Engineering of Diols

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Chassis Strains | Host organisms optimized for secondary metabolite production or alkane conversion. | Streptomyces albus [29], Yarrowia lipolytica (Po1g ku70Δ) [13] [3], Bacillus amyloliquefaciens [31]. |

| PKS Genetic Parts | Standardized, codon-optimized DNA elements for modular pathway construction. | Rimocidin PKS loading module [29], Thioreductase (TR) termination domain [30], Branched-chain specific Acyltransferase (AT) domains [29]. |

| Pathway Enzymes | Enzymes for converting PKS aldehyde intermediates into final products. | Alcohol Dehydrogenases (ADHs) [29], Specific Transaminases [29], Alkane Hydroxylases (ALK1) [13]. |

| Gene Editing Systems | Precision tools for gene knockout, repression, and integration. | CRISPR-Cas9 system for Y. lipolytica [13] [3], Plasmid pJOE8999a for B. amyloliquefaciens [31]. |

| Analytical Standards | Reference compounds for accurate identification and quantification of products. | Commercial 1,12-dodecanediol [13], 1,4-butanediol [32], and other target linear/branched diols. |

Process intensification represents a pivotal strategy in bioprocessing for achieving sustainable production goals, enhancing productivity, and reducing environmental impact. Within the context of alkane bioconversion to diols, this approach integrates advanced metabolic engineering with innovative process design to overcome fundamental bottlenecks in yield and efficiency. The oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica serves as a promising platform for these conversions, offering inherent capabilities for metabolizing hydrophobic substrates like alkanes. However, wild-type strains produce only minimal diol quantities (e.g., 0.05 mM 1,12-dodecanediol) due to competing oxidation pathways that divert intermediates to carboxylic acids [13] [3]. This application note details protocols for intensifying these bioprocesses through targeted genetic modifications and optimized fermentation conditions, enabling researchers to significantly enhance diol production from alkane feedstocks.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents and materials for alkane bioconversion to diols

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Yarrowia lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ | Parental strain for metabolic engineering | Deficient in non-homologous end joining to improve gene targeting efficiency [3] |

| n-Dodecane | Alkane substrate for diol production | 50 mM working concentration; other alkanes (C6-C16) can be substituted [13] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precision genome editing | pCRISPRyl vector (Addgene #70007) for gene knockouts [13] [3] |

| ALK1 Overexpression Vector | Enhances primary alkane hydroxylation | pYl-based expression vector with strong promoter [13] |

| YPD Medium | Routine yeast cultivation | 20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L peptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, pH 6.5 [3] |

| Synthetic Complete Medium | Selective cultivation | 20 g/L glucose, 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base, amino acid mix (-Leu) [3] |

Metabolic Engineering Protocol for Enhanced Diol Production

Principle

This protocol describes the rational engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica to redirect metabolic flux from over-oxidation pathways toward the accumulation of medium-chain α,ω-diols from alkanes. By systematically deleting genes involved in fatty alcohol and aldehyde oxidation while simultaneously enhancing alkane hydroxylation capability, researchers can achieve significant improvements in diol yield [13] [3].

Equipment

- Thermal cycler (PCR)

- Electroporation system

- Microcentrifuge

- Incubator shakers (30°C and 37°C)

- Spectrophotometer

- Anaerobic workstation (optional)

Procedure

Step 1: Construction of Multiplexed CRISPR-Cas9 Repression Vectors

- Vector Preparation: Use pCRISPRyl (Addgene #70007) as the cloning template. This vector contains a Cas9 expression cassette and a sgRNA scaffold [13].

- sgRNA Design: Design 20 bp guiding sequences targeting the following genes:

- Fatty alcohol oxidation genes: FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1

- Fatty aldehyde oxidation genes: FALDH1-4 [3]

- Multiplexing: For simultaneous, combinatorial gene targeting, insert additional sgRNA scaffold sequences downstream of the original sgRNA scaffold site.

- Cloning: Insert guiding sequences upstream of each sgRNA scaffold using overlapping PCR.

- Transformation: Transform PCR products into E. coli DH5α and select on LB medium with ampicillin (100 mg/L). Verify plasmids by sequencing [13].

Step 2: Construction of P450 ALK Gene Overexpression Vectors

- Gene Amplification: PCR amplify CYP450 alkane monooxygenase genes (particularly ALK1) from Y. lipolytica genome.

- Vector Assembly: Clone amplified genes into pYl yeast expression vector using Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC).

- Vector Modification: Replace Cas9 ORF in pCRISPRyl with the ALK1 gene and remove sgRNA scaffolds to create pYl-ALK1 [13].

Step 3: Strain Development via CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Deletion

- Preparation of Competent Cells: Grow Y. lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ in YPD medium to mid-exponential phase. Harvest cells and prepare competent cells using standard yeast protocols.

- Transformation: Co-transform competent cells with:

- Multiplexed CRISPR-Cas9 repression vectors targeting oxidation genes

- pYl-ALK1 overexpression vector

- Selection: Plate transformation mixture on synthetic complete medium without leucine and incubate at 30°C for 2-3 days [3].

- Screening: Pick colonies and screen for successful gene deletions using colony PCR and sequencing.

- Strain Validation: Validate engineered strain (designated YALI17) for correct genotype including deletion of 10 fatty alcohol oxidation genes and 4 fatty aldehyde oxidation genes, plus ALK1 overexpression [3].

Analysis

- Confirm gene deletions by PCR amplification and sequencing of target loci

- Verify ALK1 overexpression using RT-qPCR

- Evaluate 1,12-dodecanediol production using HPLC or GC-MS

Process Intensification via Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation

Principle

Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation (SSF) integrates enzymatic hydrolysis with microbial fermentation in a single vessel, offering significant advantages over separate hydrolysis and fermentation (SHF). This approach prevents end-product inhibition of enzymes by continuously consuming released sugars, reduces processing time, and decreases equipment requirements [33]. In the context of alkane bioconversion, this principle can be adapted for co-feeding strategies or complex substrate mixtures.

Quantitative Comparison of SSF vs. SHF

Table 2: Performance comparison of separate hydrolysis and fermentation (SHF) versus simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) for bioethanol production [33]

| Substrate | Process | Ethanol Concentration (g/L) | Increase in SSF | Productivity Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empty fruit bunch | SHF | Data not reported | 27.5% | Factor of ≥1.9 |

| Empty fruit bunch | SSF | Data not reported | - | - |

| Cassava pulp | SHF | Data not reported | 47.7% | Factor of ≥1.9 |

| Cassava pulp | SSF | 34.7 | - | - |

| Corn stover | SHF | Data not reported | 6.0% | Factor of ≥1.9 |

| Corn stover | SSF | Data not reported | - | - |

| Loblolly pine | SHF | Data not reported | 7.3% | Factor of ≥1.9 |

| Loblolly pine | SSF | Data not reported | - | - |

| Wheat straw | SHF | Data not reported | -21.8% | Factor of ≥1.9 |

| Wheat straw | SSF | Data not reported | - | - |

Process Optimization Parameters

- Temperature: Compromise between optimal enzymatic (45-50°C) and microbial (30-37°C) temperatures [33]

- pH: Controlled at 6.0 for butyrate production; may require adjustment for different products [33]

- Substrate loading: Optimize to minimize inhibition while maximizing yield

- Enzyme cocktail: Tailor to specific substrate composition

Intensified Fermentation Protocol for Diol Production

Principle

This protocol leverages the engineered YALI17 strain for enhanced production of 1,12-dodecanediol from n-dodecane under pH-controlled conditions. The combination of blocked oxidation pathways and enhanced alkane hydroxylation enables a 29-fold improvement over wild-type production levels [13] [3].

Equipment

- Bioreactor with pH control system

- Automated sampling system

- HPLC or GC-MS system

- Centrifuge

- Spectrophotometer

Procedure

Step 1: Inoculum Preparation

- Streak engineered YALI17 strain from glycerol stock onto YPD agar plate.

- Incubate at 30°C for 48 hours.

- Pick a single colony and inoculate into 10 mL YPD medium in a 100 mL flask.

- Incubate at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm) for 24 hours.

- Transfer 1 mL of this pre-culture to 20 mL of fresh synthetic complete medium in a 100 mL flask.

- Incubate at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm) for another 48 hours [3].

Step 2: Bioreactor Setup and Operation

- Medium Preparation: Prepare defined medium with n-dodecane (50 mM) as carbon source.

- Bioreactor Inoculation: Transfer seed culture to bioreactor at 10% (v/v) inoculation ratio.

- Process Parameters:

- Temperature: 30°C

- Agitation: 300-500 rpm (maintain oxygen transfer)

- Aeration: 0.5-1.0 vvm

- pH: Automatically controlled at optimal setpoint (determined experimentally) [13]

- Fed-batch Operation: Implement fed-batch strategy with n-dodecane feeding to maintain concentration while minimizing substrate inhibition.

- Process Monitoring: Regularly sample and analyze for:

- Cell density (OD600)

- Substrate consumption (GC)

- Diol production (HPLC or GC-MS)

- By-product formation

Step 3: Product Recovery

- Harvest cells when diol production reaches maximum (typically 120-168 hours).

- Separate cells from broth by centrifugation (5000 × g, 10 min).

- Extract diols from supernatant using organic solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Concentrate extracts under reduced pressure.

- Purify 1,12-dodecanediol using column chromatography or crystallization.

Analysis

- Quantify 1,12-dodecanediol using HPLC with UV detection or GC-MS

- Calculate yield, titer, and productivity

- Compare performance with wild-type and intermediate strains

Visualization of Metabolic Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Figure 1: Metabolic engineering strategy for enhanced diol production in Y. lipolytica

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for intensified diol production

Expected Outcomes and Performance Metrics

Table 3: Performance progression of engineered Y. lipolytica strains for 1,12-dodecanediol production from n-dodecane [13] [3]

| Strain | Genetic Modifications | 1,12-Dodecanediol Production (mM) | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | None | 0.05 | 1x |

| YALI17 | Deletion of 10 alcohol & 4 aldehyde oxidation genes | 0.72 | 14x |

| YALI17 + ALK1 | Oxidation genes deleted + ALK1 overexpression | 1.45 | 29x |

| YALI17 + ALK1 + pH control | Full engineering with process optimization | 3.20 | 64x |

Implementation of these protocols should yield progressively enhanced diol production, with the fully optimized system achieving approximately 3.20 mM 1,12-dodecanediol from 50 mM n-dodecane - a 64-fold improvement over wild-type strains. This demonstrates the powerful synergy between metabolic engineering and process intensification strategies for advancing alkane bioconversion technologies.

Overcoming Production Hurdles: Troubleshooting and Yield Optimization

In the metabolic engineering of microbial cell factories for alkane bioconversion to diols, a paramount challenge is preventing the over-oxidation of valuable intermediate products. Medium- to long-chain α,ω-diols are essential building blocks for polyesters and polyurethanes, yet their microbial synthesis from inexpensive alkane feedstocks remains inefficient due to native metabolic pathways that rapidly degrade fatty alcohols and aldehydes to carboxylic acids [3] [13]. The oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica possesses inherent capabilities for metabolizing hydrophobic substrates but contains extensive oxidation machinery that must be strategically disabled to enable diol accumulation [3]. This Application Note details validated genetic strategies for knocking out alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase (FALDH) genes to prevent over-oxidation during alkane bioconversion, providing researchers with practical protocols for enhancing diol production titers.

Target Identification: The Oxidation Machinery

Yarrowia lipolytica naturally harbors comprehensive alcohol and aldehyde oxidation systems that must be disrupted to prevent over-oxidation of diol precursors. The table below summarizes the key gene targets for metabolic engineering interventions aimed at preventing over-oxidation.

Table 1: Key Gene Targets for Preventing Over-Oxidation in Yarrowia lipolytica

| Gene Category | Gene Symbols | Number of Genes | Function in Oxidation Pathway | Impact of Deletion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Alcohol Oxidation | FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1 | 10 | Conversion of fatty alcohols to fatty aldehydes | Prevents oxidation of ω-hydroxy fatty alcohols to ω-oxo-fatty aldehydes |

| Fatty Aldehyde Oxidation | FALDH1-4 | 4 | Oxidation of fatty aldehydes to fatty acids | Blocks terminal over-oxidation to dicarboxylic acids |

| Alkane Hydroxylase | ALK1 (CYP52 family) | 1 (of 12 endogenous) | Initial oxidation of alkanes to alcohols | Overexpression enhances primary hydroxylation capacity |

The inherent oxidation capacity of wild-type Y. lipolytica results in minimal diol accumulation, with only 0.05 mM of 1,12-dodecanediol produced from n-dodecane without metabolic engineering [3] [13]. Systematic disruption of the identified ADH and FALDH genes is therefore essential for redirecting metabolic flux toward diol accumulation.

Quantitative Performance of Engineered Strains