Metabolic Engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for High-Yield Diol Production: Pathways, CRISPR Tools, and Industrial Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of advanced metabolic engineering strategies for producing diols using the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica.

Metabolic Engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for High-Yield Diol Production: Pathways, CRISPR Tools, and Industrial Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of advanced metabolic engineering strategies for producing diols using the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. We explore foundational concepts of native and engineered diol synthesis pathways, detail cutting-edge CRISPR-Cas9 methodologies for pathway optimization, and address critical troubleshooting approaches for overcoming yield limitations. The content validates these strategies through comparative analysis of computational modeling and experimental data, offering researchers and bioengineers a systematic framework for developing efficient Y. lipolytica platforms for sustainable diol production. Recent breakthroughs in alkane-to-diol conversion and high-throughput engineering methods are highlighted, demonstrating significant potential for industrial-scale implementation in pharmaceutical and chemical manufacturing.

Understanding Yarrowia lipolytica's Native Metabolism and Diol Synthesis Potential

Yarrowia lipolytica has emerged as a premier microbial chassis in industrial biotechnology, offering a unique combination of metabolic versatility, robust growth characteristics, and advanced engineering capabilities. This non-conventional, oleaginous yeast possesses inherent traits that make it particularly suitable for white biotechnology applications, including the production of biofuels, biochemicals, nutraceuticals, and recombinant proteins [1] [2]. Its classification as a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) organism by the US Food and Drug Administration facilitates its application in food and pharmaceutical industries [1] [3]. The development of sophisticated synthetic biology tools, particularly CRISPR-Cas9 systems, has enabled precise metabolic engineering of Y. lipolytica, allowing researchers to redesign its metabolic pathways for efficient production of high-value compounds such as medium-chain α,ω-diols from various feedstocks [4] [5] [6]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of Y. lipolytica's biotechnological relevance, with specific protocols for engineering and cultivating this industrially significant yeast.

Fundamental Characteristics of Y. lipolytica

Physiological and Metabolic Traits

Y. lipolytica exhibits several distinctive physiological characteristics that contribute to its industrial value. Unlike many conventional yeasts, it is an obligate aerobe with a temperature optimum between 25-30°C, though some strains can tolerate temperatures up to 37°C [1]. It demonstrates remarkable environmental resilience, growing across a wide pH range (3.5-8.0) and tolerating high salt concentrations up to 15% NaCl for some strains [1]. The yeast is dimorphic, capable of growing in either yeast-like or filamentous forms, a characteristic that requires careful control in bioprocess applications [1] [2].

Metabolically, Y. lipolytica possesses exceptional substrate flexibility, utilizing both hydrophilic carbon sources (glucose, fructose, glycerol) and hydrophobic substrates (fatty acids, triglycerides, alkanes) [1] [4]. This versatility enables the cost-effective valorization of industrial waste streams, particularly crude glycerol from biodiesel production [7] [3]. Two of its most prominent metabolic features are its efficient protein secretion pathway and its outstanding lipid accumulation capacity, making it a model organism for both secretory protein production and oleochemical synthesis [1].

Table 1: Key Physiological Characteristics of Y. lipolytica

| Characteristic | Description | Industrial Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Requirement | Obligate aerobe | High oxygen demand in fermentation |

| Temperature Range | 25-34°C (optimum 25-30°C) | Reduced cooling costs in large-scale processes |

| pH Tolerance | pH 3.5-8.0 (some strains pH 2.0-9.7) | Flexibility in process conditions; contamination resistance |

| Salt Tolerance | Up to 15% NaCl for some strains | Compatibility with industrial waste streams |

| Morphology | Dimorphic (yeast-hyphal transition) | Impacts fermentation rheology and product yield |

| Substrate Range | Wide spectrum (sugars, glycerol, hydrocarbons) | Utilizes low-cost alternative feedstocks |

| Safety Status | GRAS designation | Approved for food and pharmaceutical applications |

Genetic and Metabolic Engineering Landscape

The genetic tractability of Y. lipolytica has been extensively developed, with a comprehensive toolkit now available for strain engineering. Natural isolates are predominantly haploid and heterothallic, with mating types Mat A and Mat B, simplifying genetic manipulation [1]. The establishment of auxotrophic markers (URA3, LEU2, LYS5) and the development of efficient CRISPR-Cas9 systems have enabled precise genome editing [4] [8]. Advanced expression systems include a variety of promoters with different strengths and regulation patterns, notably the erythritol-inducible promoter system that allows high-level, tightly controllable recombinant protein synthesis [8].

Metabolic engineering efforts have leveraged the yeast's naturally high flux toward acetyl-CoA, a key precursor for numerous valuable compounds [6]. Successful engineering strategies include enhancing precursor supply, blocking competing pathways, and implementing subcellular compartmentalization of metabolic pathways [6]. The availability of genome-scale metabolic models integrated with multi-omics data provides powerful resources for identifying engineering targets and predicting metabolic behavior [6].

Y. lipolytica as a Platform for Diol Production

Metabolic Engineering for α,ω-Diol Synthesis

The production of medium- to long-chain α,ω-diols represents a particularly promising application of Y. lipolytica in white biotechnology. These diols serve as valuable building blocks for polyesters and polyurethanes, yet their microbial synthesis from inexpensive feedstocks remains challenging [4] [5]. Y. lipolytica offers distinct advantages for alkane bioconversion compared to bacterial systems, naturally harboring 12 endogenous CYP52 family P450s (Alk1-12) that catalyze the initial hydroxylation of alkanes [4] [5].

A recent breakthrough demonstrated the engineering of Y. lipolytica for enhanced production of 1,12-dodecanediol from n-dodecane [4] [5]. The engineering strategy involved systematic deletion of genes involved in fatty alcohol oxidation (FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1) and fatty aldehyde oxidation (FALDH1-4) to prevent over-oxidation of diol intermediates to carboxylic acids [4] [5]. This generated strain YALI17, which showed dramatically reduced over-oxidation activity. Further enhancement was achieved by overexpressing the alkane hydroxylase gene ALK1, resulting in a combined strain capable of producing 1.12-dodecanediol at 1.45 mM – a 29-fold improvement over wild-type levels [5].

Table 2: Engineered Y. lipolytica Strains for 1,12-Dodecanediol Production from n-Dodecane [5]

| Strain | Genotype | Description | Production (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | Po1g ku70Δ | Parental strain | 0.05 |

| YALI6 | Po1g ku70Δ mfe1Δ faa1Δ faldh1-4Δ | Fatty aldehyde oxidation deletion | Not specified |

| YALI9 | Po1g ku70Δ mfe1Δ faa1Δ faldh1-4Δ fao1Δ fadhΔ | Initial fatty alcohol oxidation deletion | Not specified |

| YALI17 | Po1g ku70Δ mfe1Δ faa1Δ faldh1-4Δ fao1Δ fadhΔ adh1-8Δ | Comprehensive oxidation pathway deletion | 0.72 |

| YALI17 + ALK1 | YALI17 with ALK1 overexpression | Enhanced alkane hydroxylation | 1.45 |

| YALI17 + ALK1 (pH-controlled) | YALI17 with ALK1 under optimized pH | Bioprocess optimization | 3.20 |

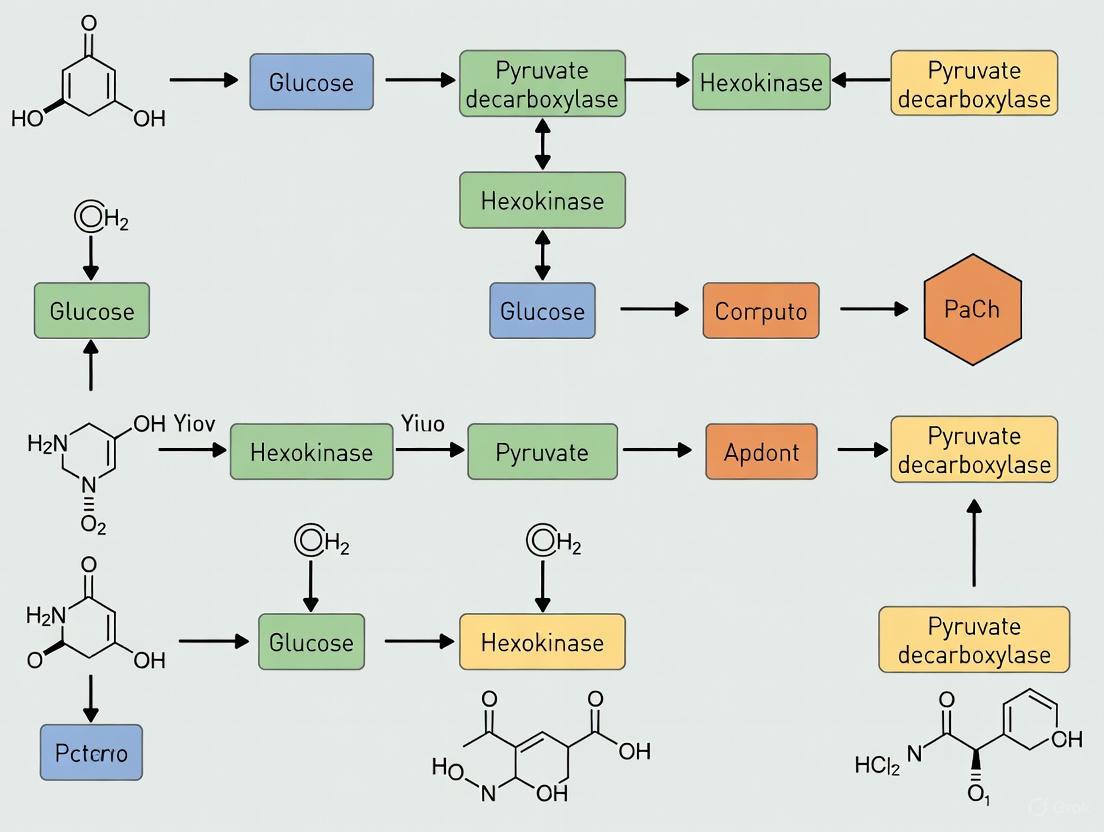

The following diagram illustrates the metabolic engineering strategy for enhanced 1,12-dodecanediol production in Y. lipolytica:

Metabolic Pathway for Diol Production in Engineered Y. lipolytica

Experimental Protocol: Engineering Y. lipolytica for Diol Production

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Deletion of Oxidation Pathway Genes

Objective: Generate Y. lipolytica strain with reduced over-oxidation activity for enhanced diol production.

Materials:

- Y. lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ strain

- pCRISPRyl plasmid (Addgene #70007) or similar CRISPR vector

- E. coli DH5α for plasmid propagation

- YPD medium: 20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L peptone, 10 g/L yeast extract

- Synthetic complete medium: 20 g/L glucose, 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base without amino acids

- Lithium acetate transformation reagents

Procedure:

- Design sgRNAs targeting FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1, and FALDH1-4 genes using CRISPOR tool

- Clone 20-bp target sequences into BsmBI-digested pCRISPRyl vector using Golden Gate assembly

- Transform assembled plasmids into E. coli DH5α, select on LB agar with ampicillin (100 mg/L)

- Verify constructs by colony PCR and sequencing

- Cultivate Y. lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ in YPD medium at 28°C to mid-exponential phase

- Co-transform 500 ng of each sgRNA plasmid with disruption cassettes using lithium acetate method

- Select transformants on synthetic complete medium without appropriate amino acids

- Verify gene deletions by diagnostic PCR and sequencing

- Screen for reduced over-oxidation activity using n-dodecane as substrate

Notes: Sequential deletion of gene families is recommended. Begin with FALDH1-4, followed by FAO1 and FADH, and finally ADH1-8. Confirm each deletion before proceeding [5].

Protocol 2: Alkane Hydroxylase Overexpression

Objective: Enhance alkane hydroxylation capacity in engineered Y. lipolytica strains.

Materials:

- Engineered Y. lipolytica strain (e.g., YALI17)

- pYl expression vector or similar

- ALK1 gene amplified from Y. lipolytica genomic DNA

Procedure:

- Amplify ALK1 coding sequence from Y. lipolytica genomic DNA

- Clone ALK1 into pYl vector under strong constitutive promoter (e.g., TEF) using Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC)

- Transform construct into engineered Y. lipolytica strain

- Select transformants on appropriate selective media

- Validate ALK1 expression by RT-PCR and western blotting

- Evaluate alkane hydroxylation activity using n-dodecane as substrate

Cultivation Strategies and Bioprocess Optimization

Substrate Utilization and Process Parameters

Y. lipolytica demonstrates remarkable flexibility in substrate utilization, enabling the cost-effective use of various industrial byproducts. When grown on crude glycerol from biodiesel production, specific growth rates of approximately 0.30 h⁻¹ have been observed, with substrate uptake rates around 0.02 mol L⁻¹ h⁻¹ [7]. This efficiency extends to high-content volatile fatty acids (VFAs) when cultivated under alkaline conditions (pH 8.0), which alleviate the inhibitory effects of undissociated VFA molecules [9]. Under optimized conditions, biomass concentrations up to 37.14 g/L and lipid production of 10.11 g/L have been achieved using 70 g/L acetic acid as carbon source [9].

The physiological response of Y. lipolytica varies significantly depending on the carbon source. Growth on glycerol is accompanied by higher oxygen uptake rates compared to growth on glucose, suggesting different metabolic routing [7]. This has important implications for process design, particularly in scale-up where oxygen transfer becomes limiting. The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, pH, and oxygen availability significantly influence the metabolic fate of carbon, directing it toward biomass, polyols, citric acid, or storage lipids [7] [3].

Table 3: Performance of Y. lipolytica on Different Carbon Sources

| Carbon Source | Growth Rate (h⁻¹) | Biomass Yield (g/g) | Major Products | Optimal Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 0.24 | 0.4-0.5 | Biomass, CO₂ | pH 4.5-6.5 [7] |

| Glycerol | 0.30 | 0.4-0.6 | Polyols, citric acid | pH 4.5-6.5 [7] |

| Acetic Acid | Not specified | 0.578 | Lipids, biomass | pH 8.0 [9] |

| Butyric Acid | Not specified | 0.570 | Lipids, biomass | pH 8.0 [9] |

| n-Dodecane | Not specified | Not specified | α,ω-diols | pH 6.5 [4] |

Experimental Protocol: Bioprocess Optimization for Polyol Production

Protocol 3: Polyol Production Under Stressful Conditions

Objective: Maximize polyol production from crude glycerol under industrially relevant, non-sterile conditions.

Materials:

- Wild-type Y. lipolytica strains (e.g., ACA-YC 5030, LMBF 20, NRRL Y-323)

- Crude glycerol from biodiesel production

- Mineral medium: (NH₄)₂SO₄ 5.0 g/L, KH₂PO₄ 3.0 g/L, MgSO₄·7H₂O 0.5 g/L

- Trace metal and vitamin solutions

- Bioreactor or shake flasks

Procedure:

- Prepare media with crude glycerol (≈140 g/L) as sole carbon source

- Adjust initial pH to 2.0 ± 0.3 using HCl or H₂SO₄

- Inoculate with pre-cultured Y. lipolytica to initial OD₆₀₀ of 0.2

- Incubate at 20 ± 1°C with agitation (180 rpm for flasks, appropriate aeration for bioreactor)

- Monitor biomass, glycerol consumption, and polyol production over time

- For non-aseptic conditions, operate without sterile media preparation

Notes: Strain selection is critical for performance under stressful conditions. NRRL Y-323 has demonstrated exceptional polyol production (84.2 g/L total polyols) with conversion yield of 62% w/w under these conditions [3]. Low pH provides selective advantage against contaminating microorganisms.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process for strain development and bioprocess optimization:

Integrated Strain and Bioprocess Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Y. lipolytica Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| pCRISPRyl Vector | CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing | Addgene #70007; contains Cas9 and sgRNA scaffold [4] |

| Erythritol-Inducible Promoter | Tightly regulated gene expression | pEYL1-5AB; high-level, titratable expression [8] |

| Auxotrophic Markers | Selection of transformants | URA3, LEU2, LYS5; enable marker recycling [8] |

| YPD Medium | Routine cultivation | 20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L peptone, 10 g/L yeast extract [4] |

| Synthetic Complete Medium | Selection and maintenance | 6.7 g/L YNB, 2% glucose, appropriate amino acid supplements [8] |

| Alkane Substrates | Diol production studies | n-Dodecane (C12), n-octane (C8); 50-100 mM concentrations [4] |

| Crude Glycerol | Low-cost carbon source | Biodiesel-derived; may require pretreatment [3] |

Y. lipolytica represents a robust and versatile platform for industrial biotechnology, with particular promise for the production of valuable diols and other chemical building blocks. The integration of advanced engineering tools with its innate metabolic capabilities enables the redesign of metabolic pathways for efficient conversion of diverse feedstocks to target products. Future developments will likely focus on expanding the substrate range to include pentose sugars and other waste streams, enhancing oxygen utilization efficiency, and implementing dynamic regulatory systems for optimal pathway control. As engineering tools continue to mature and our understanding of Y. lipolytica's metabolic network deepens, this non-conventional yeast is poised to become an increasingly important workhorse for sustainable biomanufacturing.

Native Metabolic Pathways Relevant to Diol Biosynthesis

Yarrowia lipolytica has emerged as a promising microbial chassis for the production of valuable chemicals, including diols, due to its innate capacity to metabolize hydrophobic substrates and its well-developed metabolic engineering toolbox [4]. While this yeast natively possesses metabolic pathways that can be harnessed for diol biosynthesis, its wild-type form produces only trace amounts of these compounds, necessitating strategic genetic interventions [5]. Understanding and engineering the native metabolic pathways of Y. lipolytica is therefore fundamental to developing efficient bioprocesses for diol production. This application note details the native metabolic framework of Y. lipolytica relevant to diol biosynthesis, provides protocols for its engineering, and visualizes the critical pathway interactions.

Native Metabolic Pathways ofY. lipolyticafor Diol Biosynthesis

Y. lipolytica possesses a native metabolic network that can be redirected toward diol synthesis, primarily through its alkane assimilation machinery and central carbon metabolism.

Alkane Hydroxylation System

The most direct native pathway for diol precursor synthesis in Y. lipolytica is the alkane hydroxylation system. This yeast natively harbors 12 endogenous CYP52 family P450 enzymes (Alk1-Alk12) that catalyze the terminal hydroxylation of alkanes to corresponding fatty alcohols [4] [5]. These cytochrome P450 monooxygenases require electron transport partners and molecular oxygen for function, initiating the oxidation cascade from alkanes.

Oxidation Machinery and Competing Pathways

The primary challenge in diol production lies in the yeast's efficient oxidation machinery that rapidly converts intermediates to carboxylic acids, preventing diol accumulation. This competing system includes [4] [5]:

- 9 alcohol dehydrogenases (FADH, ADH1-8)

- 1 fatty alcohol oxidase (FAO1)

- 4 fatty aldehyde dehydrogenases (FALDH1-4)

In wild-type strains, this robust oxidation network efficiently converts fatty alcohols to fatty aldehydes and subsequently to fatty acids, explaining the minimal native diol production of only ~0.05 mM 1,12-dodecanediol [5].

Table 1: Key Native Enzymes in Y. lipolytica Affecting Diol Biosynthesis

| Enzyme Category | Gene Examples | Native Function | Effect on Diol Accumulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkane Hydroxylases | ALK1-ALK12 | ω-hydroxylation of alkanes to fatty alcohols | Positive - generates diol precursors |

| Alcohol Dehydrogenases | FADH, ADH1-ADH8 | Oxidation of fatty alcohols to fatty aldehydes | Negative - consumes intermediates |

| Fatty Alcohol Oxidases | FAO1 | Oxidation of fatty alcohols to fatty aldehydes | Negative - consumes intermediates |

| Aldehyde Dehydrogenases | FALDH1-FALDH4 | Oxidation of fatty aldehydes to fatty acids | Negative - consumes intermediates |

The following diagram illustrates the native metabolic pathways for alkane conversion and the critical engineering targets for enhancing diol production in Y. lipolytica:

Metabolic Engineering Strategy and Protocol

This section provides a detailed methodology for reprogramming Y. lipolytica to enhance diol production by leveraging and modifying its native metabolic pathways.

Strain Engineering Workflow

The following protocol outlines the complete workflow for engineering a high-diol-producing Y. lipolytica strain, from genetic modifications to fermentation and analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.2.1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Multiplex Gene Deletion

Objective: Simultaneously delete 14 genes involved in fatty alcohol oxidation (FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1) and fatty aldehyde oxidation (FALDH1-4) to prevent over-oxidation of diol intermediates [4] [5].

Materials:

- Y. lipolytica PO1g ku70Δ strain

- pCRISPRyl plasmid (Addgene #70007)

- E. coli DH5α competent cells

- Frozen EZ Yeast Transformation II kit (Zymo Research)

- YPD medium: 10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 20 g/L glucose

- YNB plates: 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base, 10 g/L glucose, 2% agar

Procedure:

- Design sgRNAs: Design 20 bp guiding sequences targeting each of the 14 oxidation pathway genes (FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1, FALDH1-4).

- Construct CRISPR vectors: Clone guiding sequences into pCRISPRyl plasmid upstream of sgRNA scaffolds using overlapping PCR.

- Transform E. coli: Introduce constructed plasmids into E. coli DH5α, select on LB plates with ampicillin (100 mg/L).

- Verify plasmids: Purify plasmids from selected colonies and verify by sequencing.

- Transform Y. lipolytica: Transform PO1g ku70Δ strain with verified plasmids using Frozen EZ Yeast Transformation II kit.

- Select transformants: Plate on YNB plates and incubate at 30°C for 2-4 days.

- Validate deletions: Screen transformants via colony PCR to confirm gene deletions.

- Recycle marker: Culture positive transformants on YPD plates containing 5-FOA to recycle the URA3 marker.

Notes: The ku70Δ background enhances homologous recombination efficiency. Include parental strain as control throughout the process.

Protocol 3.2.2: ALK1 Monooxygenase Overexpression

Objective: Enhance the first hydroxylation step of alkane conversion by overexpressing the native ALK1 gene [4].

Materials:

- Engineered YALI17 strain (with oxidation pathways blocked)

- pYl expression vector

- Y. lipolytica codon-optimized ALK1 gene

Procedure:

- Amplify ALK1: PCR amplify ALK1 gene from Y. lipolytica genomic DNA.

- Clone into pYl: Use Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC) to insert ALK1 into pYl expression vector under TEF promoter.

- Transform: Introduce constructed vector into YALI17 strain.

- Validate expression: Confirm ALK1 overexpression via RT-qPCR or Western blot.

Protocol 3.2.3: Fermentation and Diol Production Analysis

Objective: Evaluate diol production performance of engineered strains using n-dodecane as substrate [4] [5].

Materials:

- Engineered Y. lipolytica strains

- YPD medium: 10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 20 g/L glucose

- Fermentation medium: YP with 50 mM n-dodecane

- Bioreactor with pH control system

- GC-MS system (e.g., Agilent 7890-8975C)

Procedure:

- Pre-culture: Inoculate single colonies into 5 mL YPD medium in 25 mL flask, culture at 30°C, 220 rpm for 24 h.

- Seed culture: Transfer to 50 mL YPD in 250 mL flask, adjust to OD600 = 0.5, incubate at 30°C, 220 rpm for 24 h.

- Fermentation: Inoculate seed culture into bioreactor containing fermentation medium with 50 mM n-dodecane.

- pH control: Maintain pH at 6.5 using automated pH control system.

- Monitor growth: Track biomass (OD600) and substrate consumption for 120 h.

- Extract products: Add 10% (v/v) dodecane after 12 h fermentation for in situ extraction.

- Analyze products: Collect organic phase, dilute with dodecane, filter through 0.22 μm membrane, analyze by GC-MS.

- Quantify diols: Use 1,12-dodecanediol standards for calibration and quantification.

Table 2: Performance of Engineered Y. lipolytica Strains for 1,12-Dodecanediol Production

| Strain | Genotype | Substrate | Production (mM) | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | PO1g ku70Δ | 50 mM n-dodecane | 0.05 | 1x |

| YALI17 | PO1g ku70Δ, 14 oxidation gene deletions | 50 mM n-dodecane | 0.72 | 14x |

| YALI17 + ALK1ox | YALI17 with ALK1 overexpression | 50 mM n-dodecane | 1.45 | 29x |

| YALI17 + ALK1ox + pH control | With automated pH control | 50 mM n-dodecane | 3.20 | 64x |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Metabolic Engineering of Y. lipolytica

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function/Application | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCRISPRyl | Plasmid | CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in Y. lipolytica | Addgene #70007 |

| Frozen EZ Yeast Transformation II Kit | Transformation kit | High-efficiency yeast transformation | Zymo Research |

| YPD Medium | Growth medium | Routine cultivation of Y. lipolytica | 10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 20 g/L glucose |

| YNB Plates | Selection medium | Selection of transformants | 6.7 g/L YNB, 10 g/L glucose, 2% agar |

| pYl Expression Vector | Expression plasmid | Heterologous gene expression | Derived from pCRISPRyl |

| ALK Genes | Native enzymes | Alkane hydroxylation | CYP52 family P450s from Y. lipolytica |

| n-dodecane | Substrate | Alkane feedstock for diol production | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 5-Fluoroorotic Acid (5-FOA) | Selection agent | Counterselection for marker recycling | 1 mg/mL in YPD plates |

Concluding Remarks

The native metabolic pathways of Y. lipolytica provide a foundational platform for diol biosynthesis, particularly through its alkane hydroxylation system. However, successful diol production requires substantial metabolic reprogramming to block competing oxidation pathways while enhancing precursor flux. The protocols outlined here have demonstrated remarkable success, achieving a 64-fold improvement in 1,12-dodecanediol production compared to wild-type strains [4] [5]. This engineering framework establishes Y. lipolytica as a promising microbial cell factory for sustainable production of valuable medium- to long-chain diols from alkane feedstocks.

Within metabolic engineering, diols are classified by carbon chain length, which directly correlates with distinct production challenges and technological maturity. Short-chain diols (C2-C5) have achieved industrially relevant production metrics through established microbial processes. In contrast, medium-chain (C6-C12) and long-chain (>C12) diols present significant bottlenecks, with production efficiencies "orders of magnitude lower" than their short-chain counterparts [5] [4]. This application note details these fundamental distinctions within the context of engineering Yarrowia lipolytica for diol production, providing structured data comparisons and actionable protocols for researchers addressing these challenges.

Quantitative Comparison of Diol Production

The disparity between short-chain and medium/long-chain diol production is evident in achieved titers, host systems, and feedstock strategies.

Table 1: Production Metrics for Short-Chain vs. Medium/Long-Chain Diols

| Diol Category | Representative Compound | Maximum Reported Titer | Model Host Organism | Primary Feedstock |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain (< C5) | 1,3-Propanediol | 26 g/L [5] [4] | Clostridium beijerinckii | Glucose [5] [4] |

| 1,4-Butanediol | 18 g/L [5] [4] | Engineered E. coli | Glucose [5] [4] | |

| Medium/Long-Chain (≥ C6) | 1,12-Dodecanediol | 3.2 mM (~0.65 g/L) [5] [4] | Engineered Y. lipolytica | n-Dodecane [5] [4] |

| 1,8-Octanediol | 108 mg/L [5] [4] | Bacterial Systems | n-Octane [5] [4] |

Table 2: Key Challenges in Medium/Long-Chain Diol Production

| Challenge Category | Short-Chain Diols | Medium/Long-Chain Diols |

|---|---|---|

| De Novo Synthesis | Established from simple sugars (e.g., glucose) [5] [4] | No efficient routes from simple carbon sources [5] [4] |

| Primary Production Host | E. coli, Clostridium [5] [4] | E. coli, Pseudomonas, Yarrowia lipolytica [5] [4] [10] |

| Key Technical Hurdle | Pathway optimization [5] [4] | Over-oxidation of intermediates; Heterologous P450 expression [5] [4] |

| Common Feedstock | Renewable sugars [5] [4] | Fatty acids, alkanes [5] [4] [10] |

Protocol: EngineeringYarrowia lipolyticafor 1,12-Dodecanediol Production

This protocol details the metabolic engineering strategy to enhance the production of 1,12-dodecanediol from n-dodecane in Y. lipolytica by blocking competing oxidation pathways and enhancing hydroxylation capacity [5] [4].

Strain and Media Preparation

- Strains: Utilize Yarrowia lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ as the parental strain for genetic manipulations due to its high homologous recombination efficiency [5] [4].

- Media:

- Culture Conditions: Incubate cultures at 28-30°C with shaking. For transformation and selection, use media without L-leucine [5] [4].

CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Gene Deletion to Block Over-Oxidation

The following steps create a base strain (YALI17) with minimized over-oxidation of fatty alcohol and aldehyde intermediates.

sgRNA Design and Vector Construction:

- Design guiding sequences (20 bp) targeting the 5' regions of the following genes involved in oxidative metabolism [5] [4]:

- Clone these target-specific sequences into the 5' end of the sgRNA scaffold in the pCRISPRyl plasmid (Addgene #70007) using standard molecular biology techniques like overlapping PCR and DpnI digestion [4].

Transformation and Selection:

- Transform the constructed CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid into competent Y. lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ cells.

- Select transformants on synthetic complete medium agar plates lacking leucine.

- Isolate single colonies and verify gene deletions via colony PCR and/or sequencing.

Sequential Strain Engineering: The final strain, YALI17, has the genotype: Po1g ku70Δ mfe1Δ faa1Δ faldh1-4Δ fao1Δ fadhΔ adh1-8Δ [5]. Construct intermediate strains (e.g., YALI1 to YALI16) by sequentially adding gene deletions to monitor the improvement in diol production [5].

Overexpression of Alkane Hydroxylase

To enhance the initial hydroxylation of the alkane substrate, overexpress the native alkane hydroxylase gene ALK1.

Vector Construction:

- PCR-amplify the ALK1 gene from the Y. lipolytica genome.

- Clone the amplified gene into a Y. lipolytica expression vector (e.g., pYl, derived from pCRISPRyl by replacing the Cas9 ORF and removing sgRNA scaffolds) using methods like Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC) [4].

- The expression should be driven by a strong constitutive promoter, such as the TEF promoter [4].

Strain Transformation:

- Transform the ALK1 overexpression vector into the engineered base strain YALI17.

- Select and verify transformants as described in Section 3.2.

Biotransformation and Analysis

Fermentation:

Product Quantification:

- Extract metabolites from the culture broth using an appropriate organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Analyze the extracts via Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to identify and quantify 1,12-dodecanediol production [5].

Pathway Engineering Diagram

The following diagram visualizes the metabolic engineering strategy implemented in the protocol to redirect flux in Y. lipolytica from alkane degradation towards diol production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists essential materials and tools used in the featured protocol for engineering Y. lipolytica.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Diol Production in Y. lipolytica

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| pCRISPRyl Vector | CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in Y. lipolytica | Available from Addgene (#70007) [4] |

| Alkane Substrate | Feedstock for diol production | n-Dodecane (C12) used at 50 mM [5] [4] |

| ALK Genes | Native alkane hydroxylases for initial oxidation | ALK1 overexpression shown to enhance production [5] [4] |

| TEF Promoter | Strong constitutive promoter for gene expression | Used in pYl-derived expression vectors [4] |

| Synthetic Complete Medium | Selection and maintenance of engineered strains | Formulation without L-leucine for auxotrophic selection [5] [4] |

The CYP52 P450 family, also known as P450alk, encompasses a specialized group of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases that serve as the primary enzymatic machinery for the initial and rate-limiting step of n-alkane assimilation in various yeast species. These membrane-bound, heme-containing enzymes catalyze the terminal hydroxylation of n-alkanes to corresponding primary alcohols, which are subsequently oxidized to fatty aldehydes and fatty acids through metabolic pathways [11] [12]. This hydroxylation capability extends beyond alkanes to include fatty acids and their derivatives, positioning CYP52 enzymes as critical biocatalysts in both native microbial metabolism and engineered bioprocesses [13] [14].

The CYP52 family demonstrates significant phylogenetic diversity with multiple paralogs found across alkane-assimilating yeasts including Yarrowia lipolytica, Candida tropicalis, Candida maltosa, Candida albicans, and Debaryomyces hansenii [13] [11] [12]. This multiplication and diversification of CYP52 genes enables host organisms to thrive on diverse hydrophobic carbon sources and adapt to various environmental conditions, including contaminated ecosystems [11] [12]. From a biotechnological perspective, CYP52 enzymes provide essential oxidative functions for the conversion of inexpensive alkane feedstocks into valuable bio-based chemicals, including fatty alcohols, dicarboxylic acids, and α,ω-diols [4] [15].

Functional Diversity and Substrate Specificity of CYP52 Enzymes

Comprehensive Classification of Y. lipolytica CYP52 Enzymes

Research has revealed that the twelve CYP52 enzymes in Y. lipolytica exhibit distinct yet sometimes overlapping substrate preferences, allowing them to collectively process a broad spectrum of hydrophobic compounds. Based on extensive functional characterization, these enzymes can be systematically categorized into four major groups according to their substrate specificities [11] [14].

Table 1: Functional Classification of Y. lipolytica CYP52 (ALK) Enzymes

| Group | Enzymes | Primary Substrate Specificity | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alk1p, Alk2p, Alk9p, Alk10p | Significant activities to hydroxylate n-alkanes | Initial alkane activation |

| 2 | Alk4p, Alk5p, Alk7p | Significant activities to hydroxylate ω-terminal end of dodecanoic acid | Fatty acid ω-hydroxylation |

| 3 | Alk3p, Alk6p | Significant activities to hydroxylate both n-alkanes and dodecanoic acid | Dual substrate range |

| 4 | Alk8p, Alk11p, Alk12p | Faint or no activities to oxidize n-alkanes or dodecanoic acid | Specialized/unknown functions |

This functional diversification enables Y. lipolytica to efficiently assimilate various hydrophobic compounds through complementary enzymatic activities. The n-alkane specialists (Group 1) perform the critical first step in alkane metabolism, while the fatty acid ω-hydroxylases (Group 2) contribute to both energy metabolism and the production of dicarboxylic acids [14]. Enzymes with broad substrate ranges (Group 3) provide metabolic flexibility, and those with limited activity on standard substrates (Group 4) may possess specialized functions not yet fully characterized [11].

Structural Basis for Regioselectivity

The regioselectivity of CYP52 enzymes, particularly their ability to preferentially hydroxylate the thermodynamically disfavored terminal methyl group (ω-position) of alkanes and fatty acids, represents a key structural and functional feature. Research on CYP52A21 from Candida albicans indicates that this specificity is achieved through a constricted access channel that positions the substrate terminus near the heme iron active site [13].

This narrow channel mechanism shows interesting parallels with the mammalian CYP4A fatty acid ω-hydroxylases, though with distinct structural implementations. Unlike some CYP4A enzymes that employ covalent heme binding to create rigid substrate channels, CYP52A21 achieves similar regioselectivity without permanent heme-protein covalent linkages [13]. Evidence from studies using terminally-halogenated fatty acid substrates demonstrates that the diameter of this access channel effectively limits oxidation to the terminal atoms, with decreased productivity observed as the size of the terminal halide increases (iodine > bromine > chlorine) [13].

Metabolic Engineering Applications for Diol Production

Engineering Y. lipolytica for α,ω-Diol Production

The strategic manipulation of Yarrowia lipolytica's native alkane hydroxylation machinery enables sustainable microbial production of valuable medium- to long-chain α,ω-diols from alkane feedstocks. These diols serve as essential building blocks for polyesters and polyurethanes, with traditional chemical synthesis often facing challenges in selectivity and sustainability [4] [15]. Recent metabolic engineering breakthroughs have demonstrated the feasibility of direct biotransformation of n-alkanes to α,ω-diols in engineered Y. lipolytica strains.

A landmark study employed CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing to systematically delete ten genes involved in fatty alcohol oxidation (FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1) and four fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase genes (FALDH1-4), creating strain YALI17 with significantly reduced over-oxidation activity [4] [15]. This engineered strain produced 0.72 mM 1,12-dodecanediol from 50 mM n-dodecane, representing a 14-fold increase over the parental strain [4]. Subsequent overexpression of the alkane hydroxylase gene ALK1 further enhanced production to 1.45 mM, and implementation of an automated pH-controlled biotransformation system ultimately achieved 3.2 mM 1,12-dodecanediol production – a 29-fold improvement over wild-type capabilities [4] [15].

Table 2: Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Enhanced α,ω-Diol Production in Y. lipolytica

| Engineering Strategy | Specific Modifications | Impact on 1,12-Dodecanediol Production |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway blocking | Deletion of 10 alcohol oxidation genes (FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1) and 4 aldehyde oxidation genes (FALDH1-4) | 14-fold increase (0.72 mM) |

| Alkane hydroxylation enhancement | Overexpression of ALK1 in YALI17 background | 2-fold further increase (1.45 mM) |

| Bioprocess optimization | Automated pH-controlled fermentation | Final titer of 3.2 mM (29-fold total increase) |

| Host selection | Use of oleaginous yeast Y. lipolytica vs. E. coli | Superior alkane uptake and compartmentalization |

Comparative Host Capabilities

The selection of Yarrowia lipolytica as a production host for alkane-derived diols provides distinct advantages over bacterial systems such as Escherichia coli. As an oleaginous yeast, Y. lipolytica possesses natural capabilities for hydrophobic substrate utilization, including specialized cellular machinery for alkane uptake, transport, and compartmentalization [4]. Furthermore, its native complement of twelve CYP52 family genes provides a robust foundation for engineering without requiring reconstruction of complete heterologous pathways [11] [14].

This intrinsic metabolic capacity contrasts with the limitations observed in E. coli systems, where heterologous CYP450 expression often encounters challenges including codon bias, protein misfolding, and complex electron transport requirements [4]. Additionally, Y. lipolytica offers advanced synthetic biology tools for precise metabolic engineering, well-established GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) status, and exceptional acetyl-CoA flux that supports abundant precursor supply for lipid-derived compounds [4] [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Functional Characterization of CYP52 Enzymes

This protocol describes the heterologous expression, purification, and functional analysis of CYP52 enzymes in E. coli, adapted from established methods for CYP52A21 characterization [13].

Heterologous Expression and Purification

- Gene Optimization and Cloning: Amplify the CYP52 gene open reading frame with a C-terminal 6×His-tag using PCR. Incorporate necessary codon modifications for optimal E. coli expression (e.g., correct Ser residue encoded by CTG leucine codon in Candida species). Clone into pCW(Ori+) vector using NdeI and XbaI restriction sites [13].

- Protein Expression: Transform E. coli DH5α with constructed vector. Inoculate 1L TB medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 1.0 mM IPTG. Grow at 37°C for 3 hours with shaking at 200 rpm, then reduce temperature to 28°C for 24 hours [13].

- Membrane Preparation and Purification: Isolate bacterial inner membrane fractions by centrifugation. Solubilize membranes overnight at 4°C in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 20% glycerol, 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1.5% CHAPS. Purify using Ni²⁺-nitrilotriacetate chromatography with elution using 400 mM imidazole. Dialyze against 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 20% glycerol and 0.1 mM EDTA [13].

Functional and Spectral Characterization

- Spectral Analysis: Record UV-visible spectra of purified P450 (approximately 1-2 μM) in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature. Generate CO-ferrous complex by adding sodium dithionite to reduce ferric P450, then bubbling CO gas through solution. Calculate P450 concentration using extinction coefficient Δε450-490 = 91 mM⁻¹cm⁻¹ [13].

- Heme Staining: Perform SDS-PAGE with purified CYP52 protein. Immerse gel in darkness in 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine (1.5 mg/mL in methanol) and 250 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) in 3:7 ratio for 1-2 hours. Add H₂O₂ to 30 mM final concentration; heme-containing proteins appear as light blue bands within 30 minutes [13].

- Enzyme Activity Assay: Reconstitute purified P450 (100 pmol) with rat NADPH-P450 reductase (250 pmol) and L-α-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (45 μM) in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Initiate reaction with NADPH-generating system. Incubate at 37°C for 10-30 minutes with appropriate substrates (e.g., dodecanoic acid, n-alkanes). Terminate reaction with methylene chloride, derivative with N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide, and analyze products by GC-MS [13].

Protocol 2: Metabolic Engineering for Diol Production

This protocol outlines the construction of engineered Y. lipolytica strains for enhanced α,ω-diol production from alkanes, based on recent successful implementations [4] [15].

CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Deletion

- Strain and Media: Use Y. lipolytica strain CXAU1 or appropriate background. Maintain in YPD medium (20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L peptone, 10 g/L yeast extract) or synthetic complete medium without appropriate auxotrophic markers [14].

- gRNA Vector Construction: Employ pCRISPRyl vector (Addgene #70007) expressing Cas9 and sgRNA scaffold. For multiplexed deletions, insert additional sgRNA scaffold sequences downstream of original site. Insert gene-specific 20 bp guiding sequences upstream of each sgRNA scaffold using overlapping PCR [4].

- Strain Transformation: Transform Y. lipolytica with constructed CRISPR vectors using standard lithium acetate protocol. Select transformations on YNBD agar with appropriate amino acid supplementation. Verify gene deletions by diagnostic PCR and sequencing [4].

Alkane Hydroxylase Overexpression

- Expression Vector Construction: Amplify ALK genes (e.g., ALK1) from Y. lipolytica genomic DNA. Clone into pYl yeast expression vector using Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC). Utilize strong constitutive or inducible promoters (e.g., TEF promoter with intron sequence) [4].

- Strain Transformation and Screening: Introduce expression vectors into engineered Y. lipolytica background strains (e.g., YALI17). Select transformants on appropriate selective media. Validate ALK gene expression by RT-qPCR and/or immunoblotting [4].

Biotransformation and Analysis

- Fermentation Conditions: Inoculate engineered strains in YPD medium and grow for 2 days. Scale up to 20 mL in 100 mL flasks and incubate additional 2 days. For alkane biotransformation, use n-dodecane (50 mM) as substrate. Implement pH-controlled fermentation for optimal production (pH 6.5) [4].

- Product Extraction and Analysis: Extract culture broth with ethyl acetate or dichloromethane. Concentrate organic phase under nitrogen gas. Derivatize with BSTFA if required for GC-MS analysis. Quantify α,ω-diols using GC-MS with selective ion monitoring or authentic standards [4].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for CYP52 and Diol Production Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vector | pCW(Ori+) with NdeI/XbaI sites | Heterologous CYP52 expression in E. coli |

| CRISPR System | pCRISPRyl (Addgene #70007) | Genome editing in Y. lipolytica |

| P450 Reductase | Recombinant rat NADPH-P450 reductase | Electron donation in reconstituted P450 systems |

| Detection Reagent | 3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine | Heme staining on SDS-PAGE gels |

| Substrates | n-Dodecane, dodecanoic acid, 12-halododecanoic acids | Enzyme activity and regioselectivity studies |

| Analytical Method | GC-MS with TMS derivatization | Hydroxylated product quantification |

Diagram 1: Metabolic Engineering Strategy for Diol Production in Y. lipolytica. The native alkane assimilation pathway (red) converts alkanes to fatty acids via multiple oxidation steps. Engineered modifications (green) enhance initial hydroxylation while blocking subsequent oxidation steps to redirect flux toward α,ω-diol accumulation.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Engineered Diol Production. The systematic approach begins with strategic gene deletions to block competing pathways, followed by alkane hydroxylase enhancement and optimized bioprocessing conditions to maximize diol yields.

In the field of microbial biosynthesis, a significant yield disparity exists between short-chain diols (typically less than 5 carbon atoms) and medium-to-long-chain diols (ranging from C6 to C14+). This production gap represents a critical challenge for the sustainable manufacturing of high-value chemical building blocks used in polymer, pharmaceutical, and specialty chemical industries. Short-chain diols such as 1,3-propanediol and 1,4-butanediol have achieved industrial-scale production through microbial fermentation, with engineered strains of Clostridium beijerinckii and Escherichia coli reaching impressive titers of 26 g/L and 18 g/L, respectively [5] [4]. In stark contrast, mid-chain (C6-C12) and long-chain (>C12) diols remain orders of magnitude lower in production efficiency, with no established de novo routes from simple carbon sources and maximum reported titers rarely exceeding 1.4 g/L even from expensive fatty acid precursors [5] [4].

The oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica has emerged as a promising chassis organism to address these production gaps, particularly for medium-to-long-chain diols, due to its innate capacity to metabolize hydrophobic substrates and its robust acetyl-CoA generation [6]. This Application Note examines the current production landscape, identifies key metabolic bottlenecks, and provides detailed protocols for engineering Y. lipolytica to bridge the yield gap through targeted metabolic engineering strategies.

Current Production Landscape & Yield Disparities

Quantitative Analysis of Production Gaps

Table 1: Comparative Production Efficiencies of Short-Chain versus Medium/Long-Chain Diols

| Diol Category | Representative Compounds | Highest Reported Titer | Production Host | Carbon Source | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain ( | 1,3-propanediol | 26 g/L | Clostridium beijerinckii | Glucose | Limited; commercial production achieved |

| Short-chain ( | 1,4-butanediol | 18 g/L | Engineered E. coli | Glucose | Limited; commercial production achieved |

| Mid-chain (C6-C12) | 1,12-dodecanediol | 1.4 g/L | Engineered E. coli | 12-hydroxydodecanoic acid | Requires expensive fatty acid precursors |

| Mid-chain (C6-C12) | 1,8-octanediol | 108 mg/L | Bacterial systems | n-octane | Low efficiency from alkane substrates |

| Long-chain (>C12) | 1,12-dodecanediol (from alkanes) | 3.2 mM (~0.64 g/L) | Engineered Y. lipolytica | n-dodecane | Competing oxidation pathways |

Table 2: Production Improvements in Engineered Yarrowia lipolytica Strains

| Strain | Genetic Modifications | Substrate | 1,12-Dodecanediol Production | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | None | n-dodecane | 0.05 mM | Reference |

| YALI17 | Δfadh, Δadh1-8, Δfao1, Δfaldh1-4 | n-dodecane | 0.72 mM | 14-fold |

| YALI17 + ALK1 | YALI17 background + ALK1 overexpression | n-dodecane | 1.45 mM | 29-fold |

| YALI17 + pH control | YALI17 + ALK1 + automated pH control | n-dodecane | 3.2 mM | 64-fold |

The quantitative data presented in Tables 1 and 2 highlight the dramatic disparity between short-chain and longer-chain diol production. While short-chain diols achieve gram-per-liter scale production, mid- to long-chain diols struggle to reach comparable levels, with the highest reported titer for 1,12-dodecanediol from alkane substrates reaching only 3.2 mM (approximately 0.64 g/L) in the most optimized Y. lipolytica strain [5] [4]. This represents nearly a 40-fold difference in productivity compared to short-chain diols.

Fundamental Challenges in Mid/Long-Chain Diol Production

The yield gap between short-chain and longer-chain diols stems from several fundamental biological challenges:

- Precursor Competition: Mid/long-chain diols require fatty acids or alkanes as precursors, which are also essential for membrane integrity and energy storage, creating inherent metabolic competition [10].

- Oxidation Cascade Control: Unlike short-chain diols, longer chains are susceptible to over-oxidation through native β-oxidation pathways, resulting in terminal carboxylic acids rather than the desired diols [5].

- Cofactor Imbalance: Cytochrome P450 systems required for terminal hydroxylation depend on NADPH and complex electron transport chains, creating cofactor regeneration challenges [5] [17].

- Toxicity and Compartmentalization: Longer-chain diols and their intermediates can be toxic to microbial cells and require sophisticated compartmentalization strategies [10].

Metabolic Engineering Strategies to Bridge the Gap

Pathway Engineering and Oxidation Blocking

Diagram Title: Metabolic Pathway Engineering Strategy in Y. lipolytica

Rational metabolic engineering of Y. lipolytica focuses on two primary strategies: (1) enhancing the flux from alkanes to fatty alcohols through overexpression of alkane hydroxylases, and (2) blocking the competing oxidation pathways that divert intermediates away from diol formation. The most successful approach has involved systematic deletion of genes encoding fatty alcohol oxidases (FAO1), fatty alcohol dehydrogenases (FADH and ADH1-8), and fatty aldehyde dehydrogenases (FALDH1-4) [5] [4]. This prevents over-oxidation of valuable intermediates to carboxylic acids, allowing diols to accumulate.

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Multi-Gene Deletion inY. lipolytica

Objective: Simultaneous deletion of 10 genes involved in fatty alcohol oxidation (FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1) and 4 fatty aldehyde oxidation genes (FALDH1-4) to create strain YALI17.

Materials:

- Y. lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ strain (improved homologous recombination)

- pCRISPRyl plasmid (Addgene #70007) containing Cas9 and sgRNA scaffold

- Donor DNA fragments with 500-bp homology arms

- YPD medium: 20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L peptone, 10 g/L yeast extract

- Synthetic complete medium without leucine

Procedure:

sgRNA Vector Construction:

- Design 20-bp guiding sequences targeting each of the 14 genes (FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1, FALDH1-4)

- Clone guiding sequences upstream of sgRNA scaffold in pCRISPRyl using overlapping PCR

- Transform into E. coli DH5α, select on LB + ampicillin (100 mg/L)

- Verify constructs by sequencing

Strain Transformation:

- Grow Y. lipolytica Po1g ku70Δ in YPD to OD600 = 1.0

- Make competent cells using Frozen-EZ Transformation kit (Zymo Research)

- Co-transform with linearized CRISPR plasmid and donor DNA fragments

- Select transformants on synthetic complete medium without leucine

Screening and Validation:

- Pick 6-8 colonies for each gene deletion

- Screen by colony PCR using gene-specific primers

- Validate successful deletions by sequencing

- Store engineered strains as glycerol stocks at -80°C

Timeline: 4-6 weeks for complete strain construction. The ku70Δ background increases homologous recombination efficiency from 28% to 54%, significantly improving success rates [18].

Advanced Engineering and Process Optimization

Alkane Hydroxylase Engineering and Cofactor Balancing

Protocol: ALK1 Overexpression for Enhanced Alkane Hydroxylation

Objective: Increase conversion of n-alkanes to fatty alcohols through overexpression of alkane monooxygenase ALK1.

Materials:

- Engineered YALI17 strain

- pYl expression vector with TEF promoter

- n-dodecane substrate

- Alk1 gene amplified from Y. lipolytica genome

Procedure:

Vector Construction:

- Amplify ALK1 coding sequence from Y. lipolytica genomic DNA

- Clone into pYl vector using Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC)

- Replace Cas9 ORF with ALK1 expression cassette in pCRISPRyl backbone

- Add intron sequence from TEF promoter at 3' end of promoter

Strain Transformation and Screening:

- Transform ALK1 expression vector into YALI17 strain

- Select on synthetic complete medium without leucine

- Screen for high-expression clones by qRT-PCR

- Validate ALK1 activity by GC-MS analysis of alcohol production from n-dodecane

Fermentation Optimization:

- Inoculate engineered strain in YPD, grow for 2 days

- Scale up to 20 mL production medium in 100 mL flask

- Add 50 mM n-dodecane as substrate

- Implement automated pH control (pH 6.5-7.0)

- Monitor diol production over 5-7 days

Application Notes: ALK1 overexpression in the YALI17 background increases 1,12-dodecanediol production from 0.72 mM to 1.45 mM. Combined with pH-controlled biotransformation, titers reach 3.2 mM [5] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Y. lipolytica Diol Production Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR System | pCRISPRyl (Addgene #70007) | Genome editing and gene deletion | ku70Δ background improves efficiency |

| Expression Vectors | pYl series with TEF promoter | Heterologous gene expression | Strong, constitutive expression |

| Alkane Substrates | n-dodecane, n-octane | Diol precursors | Hydrophobic, requires emulsification |

| Selection Markers | URA3, LEU2 | Transformant selection | Auxotrophic complementation |

| Analytical Standards | 1,12-dodecanediol, 1,8-octanediol | GC-MS/QTOF quantification | Essential for accurate titers |

| Culture Media | YPD, YNB, Synthetic Complete | Strain maintenance/propagation | Defined media for production studies |

| Electron Transport Components | NADPH regeneration systems | P450 monooxygenase support | Critical for ω-hydroxylation |

| Detergents/Solvents | Tergitol, Tween series | Substrate emulsification | Improve alkane bioavailability |

The systematic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica presents a promising approach to bridge the significant production gap between short-chain and medium/long-chain diols. Through coordinated strategies including oxidation pathway blocking, alkane hydroxylase enhancement, and bioprocess optimization, researchers have achieved remarkable 64-fold improvements in 1,12-dodecanediol production compared to wild-type strains [5] [4]. However, significant work remains to reach the gram-per-liter scale production commonly achieved with short-chain diols.

Future directions should focus on dynamic pathway control, compartmentalization of toxic intermediates, and engineering of synthetic P450 systems with improved efficiency and cofactor specificity. The integration of systems biology approaches with machine learning-enabled enzyme design will further accelerate the development of efficient microbial cell factories for medium- and long-chain diol production [10] [6]. As these engineering strategies mature, Y. lipolytica is poised to become a robust biorefinery platform for the sustainable production of valuable diol building blocks from renewable resources.

The oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica presents a superior alternative to bacterial systems for the production of high-value chemicals, particularly medium- to long-chain α,ω-diols. Its innate physiological and metabolic capabilities provide distinct advantages for alkane bioconversion and lipid accumulation, which are challenging to replicate in prokaryotic hosts. This application note details the specific endogenous advantages of Y. lipolytica and provides standardized protocols for leveraging these features in metabolic engineering projects focused on diol production.

The core strength of Y. lipolytica lies in its natural proficiency with hydrophobic substrates. Unlike E. coli, which requires extensive engineering to interact with alkanes, Y. lipolytica possesses native metabolic machinery for alkane uptake, transport, and activation [1] [19]. Furthermore, its high acetyl-CoA flux and oleaginous nature enable efficient conversion of carbon sources into storage lipids and their derivatives, providing an optimal foundation for diol synthesis [6].

Key Advantages ofY. lipolyticaOver Bacterial Systems

Endogenous Alkane Metabolism

Y. lipolytica natively produces a suite of enzymes specialized for hydrocarbon metabolism, eliminating the need for the complex heterologous expression often required in bacterial systems [4] [5].

- Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenases (CYPs): The yeast genome encodes 12 CYP52 family alkane monooxygenases (Alk1-12) that catalyze the terminal oxidation of alkanes to corresponding alcohols, the first committed step in the diol synthesis pathway [4] [5].

- Comprehensive Oxidation Machinery: The native metabolism includes a full set of alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs), fatty alcohol oxidases (FAOs), and fatty aldehyde dehydrogenases (FALDHs) that can be rationally engineered to optimize flux toward diols [4] [5].

- Hydrophobic Substrate Uptake: The yeast has efficient mechanisms for adhering to and taking up alkanes, supported by its ability to form biofilms on oil-water interfaces [19].

Superior Lipid Accumulation Capacity

As an oleaginous yeast, Y. lipolytica can accumulate lipids to over 50% of its dry cell weight under nitrogen-limited conditions [20] [21]. This high lipid content is directly linked to an expanded intracellular pool of acetyl-CoA, the central precursor for fatty acid and lipid biosynthesis [6]. This abundance of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA provides ample building blocks not only for lipids but also for a wide range of acetyl-CoA-derived products, including terpenoids and polyketides [22] [6]. Engineered strains have been reported to achieve lipid contents as high as 67.66% (g/g DCW) [20].

Safety and Industrial Robustness

Y. lipolytica holds a GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) status from the US FDA, facilitating its use in the production of food ingredients and nutraceuticals [1] [19]. It is tolerant to a wide range of pH and osmolarity, and can be cultivated on inexpensive and even waste-based feedstocks, making it suitable for large-scale industrial processes [1] [23].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key performance metrics of engineered Y. lipolytica strains for the production of valuable chemicals, highlighting its efficiency as a microbial cell factory.

Table 1: Production of Lipids and Lipid-Derived Compounds by Engineered Y. lipolytica

| Product | Strain / Engineering Background | Titer / Content | Substrate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids (Total) | yDTY214 (Engineered Po1f) | 67.66% (g/g DCW) | Lipids | [20] |

| Lipids (Total) | ylXYL+Obese (Engineered Po1d) | ~67% (g/g DCW); Titer: 16.5 g/L | Agave Bagasse Hydrolysate | [23] |

| 1,12-Dodecanediol | YALI17 (Engineered Po1g) | 1.45 mM | n-Dodecane | [4] [5] |

| 1,12-Dodecanediol | YALI17 + pH control | 3.2 mM (29-fold increase vs. WT) | n-Dodecane | [4] [5] [15] |

| β-Carotene | yDTY216 (Engineered Po1f) | High yield, 48h earlier peak production | Lipids | [20] |

Table 2: Comparison of Diol Production in Microbial Hosts

| Host Organism | Type of Diol | Maximum Reported Titer | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Medium- to Long-chain (e.g., C12) | 3.2 mM (from alkanes) | Requires pathway blocking to prevent over-oxidation |

| Escherichia coli | Medium- to Long-chain | 79 - 1,400 mg/L (from fatty acids) | Poor heterologous CYP450 expression; reliance on expensive fatty acids |

| Pseudomonas spp. | Medium- to Long-chain | ~108 mg/L (from alkanes) | Low titer; complex enzyme systems |

| Clostridium beijerinckii | Short-chain (1,3-Propanediol) | ~26 g/L (from glucose) | Not applicable for long-chain diols |

| Engineered E. coli | Short-chain (1,4-Butanediol) | ~18 g/L (from glucose) | Not applicable for long-chain diols |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Blocking of Over-Oxidation Pathways

Objective: To generate a Y. lipolytica base strain (e.g., YALI17) with minimized over-oxidation of fatty alcohols and aldehydes to carboxylic acids, thereby maximizing the accumulation of diol intermediates [4] [5].

Materials:

- Y. lipolytica strain Po1g Δku70 (or other strain with repaired Ura3 locus)

- pCRISPRyl plasmid (Addgene #70007) or similar CRISPR vector for Y. lipolytica

- E. coli DH5α for plasmid propagation

- Reagents: YPD medium, Synthetic Complete (SC) medium without leucine, ampicillin, DpnI restriction enzyme, T4 DNA ligase.

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design and Vector Construction:

- Design 20 bp guiding sequences targeting the genes of interest: FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1 (fatty alcohol oxidation), and FALDH1-4 (fatty aldehyde oxidation) [4].

- For multiplexed editing, assemble multiple sgRNA expression cassettes in the pCRISPRyl vector using overlapping PCR and Golden Gate assembly. The plasmid already contains a Cas9 expression cassette [4] [5].

- Transform the final assembled plasmid into E. coli DH5α, select on LB agar with ampicillin (100 mg/L), and verify the construct by sequencing.

Yeast Transformation and Selection:

- Introduce the verified CRISPR plasmid into the Y. lipolytica parental strain via established transformation methods (e.g., lithium acetate).

- Plate cells on SC medium without leucine and incubate at 28-30°C for 2-3 days until colonies form.

Screening and Genotypic Validation:

- Pick individual colonies and perform colony PCR to verify the deletion of target genes.

- Sequence the target loci in candidate strains to confirm frameshift mutations or complete gene deletions.

- The successful strain (YALI17) should show a significant reduction in the conversion of alcohols to acids.

Protocol 2: Alkane Hydroxylase (ALK1) Overexpression

Objective: To enhance the initial oxidation of n-alkanes to ω-hydroxy fatty acids in the engineered YALI17 background [4] [5].

Materials:

- Y. lipolytica strain YALI17

- pYl yeast expression vector (a derivative of pCRISPRyl with Cas9 and sgRNA scaffold removed)

- Genomic DNA from Y. lipolytica (source of ALK1 gene)

Procedure:

- Vector Construction:

- Amplify the coding sequence of the ALK1 gene from Y. lipolytica genomic DNA using high-fidelity PCR.

- Clone the ALK1 CDS into the pYl vector under the control of a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., TEF) using methods like Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC) [4].

- The final overexpression construct is assembled in E. coli and validated by sequencing.

- Strain Engineering:

- Transform the ALK1 overexpression vector into the YALI17 strain.

- Select transformants on appropriate auxotrophic dropout medium.

- Validate ALK1 overexpression by quantitative RT-PCR or Western blotting.

Protocol 3: Biotransformation of n-Dodecane to 1,12-Dodecanediol

Objective: To assess the diol production capability of the engineered strain in a controlled fermentation system [4] [5].

Materials:

- Engineered Y. lipolytica strain (e.g., YALI17 with ALK1 overexpression)

- n-Dodecane (50 mM final concentration)

- Bioreactor with pH and dissolved oxygen control

- Media: YPD for seed culture; Defined fermentation medium (e.g., 20 g/L glucose, 6.7 g/L YNB, necessary supplements, C/N ratio >60 to induce lipogenesis) [4] [23].

Procedure:

- Seed Culture:

- Inoculate a single colony of the engineered strain into 10 mL of YPD medium.

- Incubate at 28°C, 250 rpm for 48 hours.

Fermentation:

- Transfer the seed culture to a bioreactor containing the defined fermentation medium. The initial working volume is 20 mL in a 100 mL flask or scaled up in a larger bioreactor.

- Set fermentation temperature to 28°C, maintain pH at 6.5 (or optimize to 5.7-6.0 for enhanced production), and ensure high aeration [4] [21].

- Add filter-sterilized n-dodecane (50 mM final concentration) as the substrate once the cell density is sufficiently high (e.g., mid-exponential phase).

- Allow the biotransformation to proceed for 3-5 days.

Product Extraction and Analysis:

- Extract the culture broth with an equal volume of ethyl acetate.

- Analyze the organic phase using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to quantify 1,12-dodecanediol production. Compare against authentic standards.

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: Native vs. Engineered Alkane Metabolism in Y. lipolytica

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Diol Production

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Engineering of Y. lipolytica

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| pCRISPRyl Vector | CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in Y. lipolytica; contains Cas9 and sgRNA scaffold. | Addgene #70007 [4] |

| pYl Expression Vector | Protein overexpression; derivative of pCRISPRyl with optimized promoters. | [4] |

| Y. lipolytica Po1g Δku70 | Common parental strain; KU70 deletion improves homologous recombination efficiency. | ATCC/Marka [4] [5] |

| n-Dodecane | Hydrophobic substrate for alkane bioconversion and diol production. | Sigma-Aldrich/Chemical Supplier |

| Defined Fermentation Medium | Controlled environment for biotransformation; high C/N ratio induces product accumulation. | YNB-based media [4] [21] |

| Anti-Foam Agents | Controls foam formation during aerated cultivation with hydrophobic substrates. | Sigma-Aldrich/Chemical Supplier |

Advanced Genetic Tools and Pathway Engineering for Enhanced Diol Production

CRISPR-Cas9 Systems for Precision Genome Editing in Y. lipolytica

The oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica has emerged as a prominent microbial chassis in industrial biotechnology due to its robust metabolism, capacity to utilize diverse carbon sources, and innate ability to produce high-value lipids and chemicals [6]. Within metabolic engineering programs aimed at diol production, precision genome editing is indispensable for redirecting metabolic flux. While CRISPR-Cas9 technology has been adapted for Y. lipolytica, its editing efficiency has been historically limited by challenges such as low homologous recombination (HR) efficiency and variable sgRNA performance [24] [25]. This application note details optimized CRISPR-Cas9 systems that overcome these barriers, enabling high-efficiency genetic manipulations to streamline the development of microbial cell factories for diol synthesis.

Optimized System Components and Performance Metrics

Recent advancements have systematically optimized critical components of the CRISPR-Cas9 system for Y. lipolytica, leading to dramatic improvements in editing efficiency. The table below summarizes key performance data for these optimized components.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Optimized CRISPR-Cas9 Components in Y. lipolytica

| Optimized Component | Specific Innovation | Reported Efficiency | Key Application in Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Expression Architecture [24] [25] | Direct tRNA-sgRNA fusion (using SCR1-tRNA promoter) | 92.5% gene disruption efficiency [25] | Enables reliable gene knock-outs for blocking competing pathways. |

| HR Enhancement (DNA Repair) [25] | KU70 deletion combined with Rad52 and Sae2 overexpression | 92.5% genome integration efficiency [25] | Facilitates high-efficiency gene knock-ins for pathway engineering. |

| Engineered Cas9 Variant [25] | Use of iCas9 (Cas9D147Y, P411T) | Enhanced both gene disruption and integration efficiency [25] | Improves overall success rate of all editing operations. |

| Multiplex Editing Capacity [25] | tRNA-sgRNA architecture for processing multiple guides | 57.5% dual gene disruption efficiency [25] | Allows simultaneous knockout of multiple genes (e.g., ADH, FALDH). |

| Donor Template Design [24] | Optimization of homology arm length | Enabled recombination using donors with 50-bp homology arms [24] | Simplifies and reduces the cost of donor DNA construction. |

The foundational improvement involves the sgRNA expression system. Early designs used tRNA-sgRNA fusions with an unexplained intergenic sequence, which was predicted to form secondary structures that impaired sgRNA function. Its removal created a direct tRNA-sgRNA fusion, which significantly improved editing efficiency at previously recalcitrant genomic loci, achieving efficiencies close to 100% [24]. This architecture also enables efficient multiplexed editing by leveraging the endogenous RNase system to process multiple sgRNAs from a single transcript [25].

Enhancing Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is another critical area. Y. lipolytica has a strong preference for non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) over HDR, which limits gene integration via donor templates. A highly effective strategy involves deleting KU70, a key protein in the NHEJ pathway, which has been shown to increase integration efficiency to 92.5% [25]. Furthermore, overexpressing HR-related genes like Rad52 and Sae2 provides an additional boost to HDR rates [25]. For strains where NHEJ disruption is undesirable, using the engineered iCas9 variant and optimizing donor template homology arms to as short as 50 bp can still yield very high efficiencies [24] [25].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Efficiency Gene Deletion Using Direct tRNA-sgRNA Fusions

This protocol is designed for targeted gene knockout and is adapted from studies that achieved disruption efficiencies over 90% [24] [25].

Research Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Essential Reagents for Gene Deletion

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| pCRISPRyl Vector (Addgene #70007) | Base plasmid for expressing Cas9 and sgRNA in Y. lipolytica [4]. |

| Target-Specific sgRNA Oligos | 20-nt sequences complementary to the target genomic locus, designed with minimal off-target effects. |

| Y. lipolytica Po1f Strain | A common, double-auxotroph, NHEJ-competent host strain [24] [26]. |

| YPD Medium | Rich growth medium: 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose [24] [8]. |

| YNB Selection Medium | Synthetic minimal medium for transformant selection: 0.17% YNB without AA, 0.5% NH₄Cl, 2% glucose, 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) [8]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- sgRNA Cloning:

- Yeast Transformation:

- Cultivate Y. lipolytica Po1f in YPD medium to mid-exponential phase.

- Prepare competent cells and transform with 500 ng of the finalized sgRNA plasmid using the lithium acetate method [8].

- Selection and Screening:

- Plate transformed cells on YNB solid medium lacking the appropriate amino acid to select for the plasmid.

- Incubate plates at 28°C for 2-3 days.

- Screen individual colonies by colony PCR followed by DNA sequencing to verify the intended gene deletion.

Protocol 2: Multiplexed Gene Knockout for Pathway Engineering

This protocol enables the simultaneous disruption of multiple genes, which is essential for blocking competing metabolic pathways, as demonstrated in the engineering of a 1,12-dodecanediol production strain [5] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Essential Reagents for Multiplexed Knockout

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| tRNA-sgRNA Array Plasmid | Plasmid where multiple tRNA-sgRNA units are transcribed as a single transcript and processed intracellularly [25]. |

| Donor DNA Cassettes | Linear DNA fragments containing selection markers flanked by homology arms (50-500 bp) for recycling markers [27]. |

| CRISPR Plasmid with iCas9 | Plasmid expressing the high-efficiency iCas9 variant [25]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Multiplex sgRNA Construct Design:

- Design tRNA-sgRNA units for each target gene (e.g., FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1, FALDH1-4 for diol production) [5].

- Synthesize a construct where these units are arranged in tandem within a single expression cassette on a plasmid.

- Strain Transformation:

- Co-transform the Y. lipolytica host strain (potentially KU70-deficient for higher HDR efficiency) with the multiplex sgRNA plasmid and any donor DNA cassettes for marker recycling.

- Validation of Multiplex Editing:

- Isolate transformants and screen via colony PCR for deletions at all target loci.

- Sanger sequence the edited genomic regions to confirm the knockout of each target gene. In the referenced study, this approach successfully created strain YALI17 with 14 gene deletions [5].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps and genetic components involved in this multiplexed knockout strategy.

Protocol 3: High-Throughput Promoter Replacement (TUNEYALI)

The TUNEYALI method enables high-throughput, scarless promoter swapping to fine-tune gene expression, which is invaluable for optimizing metabolic pathways [27].

Research Reagent Solutions: Table 4: Essential Reagents for TUNEYALI Method

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| TUNEYALI Library Plasmids | Each plasmid contains an sgRNA, homology arms, and a SapI site for promoter insertion. |

| SapI Restriction Enzyme | Used for Golden Gate assembly to insert promoter elements scarlessly. |

| Library of Promoter Parts | A collection of native Y. lipolytica promoters of varying strengths. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Library Construction:

- For each target gene, design a synthetic DNA fragment containing a target-specific sgRNA, upstream and downstream homology arms (62-162 bp), and a double SapI restriction site between them.

- Clone these fragments into a plasmid backbone via Gibson assembly.

- Use SapI-mediated Golden Gate assembly to insert a library of promoter parts into the pooled plasmids.

- Library Transformation and Screening:

- Transform the entire plasmid library into the Y. lipolytica production strain.

- Screen or select for clones exhibiting the desired phenotype (e.g., improved diol production, thermotolerance).

- Identify the successful promoter-gene combinations by sequencing the integrated plasmids from the best-performing clones.

Application in Diol Production: A Case Study

The power of optimized CRISPR-Cas9 systems is exemplified by the engineering of Y. lipolytica for the production of medium- to long-chain α,ω-diols, such as 1,12-dodecanediol, from alkanes [5] [4].

Metabolic Engineering Strategy: The primary challenge is preventing the over-oxidation of fatty alcohol intermediates into fatty acids, which diverts flux away from the desired diol. The engineering strategy involved:

- Blocking Over-oxidation Pathways: Employing multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 to systematically delete ten genes involved in fatty alcohol oxidation (FADH, ADH1-8, FAO1) and four genes involved in fatty aldehyde oxidation (FALDH1-4). This resulted in the base engineered strain YALI17 [5].

- Enhancing Alkane Hydroxylation: Overexpressing the alkane hydroxylase gene ALK1 to increase the primary oxidation of n-dodecane [4].

- Process Optimization: Implementing automated pH-controlled biotransformation to further improve yield.

Results: The engineered strain YALI17 produced 0.72 mM of 1,12-dodecanediol from n-dodecane, a 14-fold increase over the parental strain. With ALK1 overexpression, production rose to 1.45 mM, and pH-controlled fermentation further boosted the titer to 3.2 mM, demonstrating the successful application of precision genome editing for diol production [5] [4].

The diagram below outlines the key stages of this metabolic engineering project.

The CRISPR-Cas9 systems detailed herein, featuring optimized sgRNA architectures, enhanced DNA repair mechanisms, and efficient multiplexing capabilities, provide a robust and precise toolkit for metabolic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica. The successful application of these tools in creating a high-performance diol-producing strain underscores their transformative potential. By enabling rapid and systematic genome manipulation, these protocols empower researchers to accelerate the design-build-test cycles necessary for developing advanced microbial cell factories.

In the metabolic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for the production of valuable chemicals such as diols, a significant challenge lies in preventing the diversion of metabolic intermediates into competing pathways. The native metabolism of this oleaginous yeast contains multiple enzyme systems that efficiently oxidize fatty alcohols and aldehydes, thereby limiting the accumulation of target products like medium-chain α,ω-diols [4] [15]. This application note details targeted gene deletion strategies to block these competing oxidation pathways, enabling significant enhancement of diol production in engineered Y. lipolytica strains.