Metabolic Flux Analysis in Cancer Research: A Comparative Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

Metabolic reprogramming is a established hallmark of cancer, driving tumor progression and therapy resistance.

Metabolic Flux Analysis in Cancer Research: A Comparative Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

Abstract

Metabolic reprogramming is a established hallmark of cancer, driving tumor progression and therapy resistance. Understanding metabolic fluxes—the dynamic flow of metabolites through biochemical pathways—is therefore crucial for identifying cancer-specific vulnerabilities. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the primary methods for metabolic flux analysis in cancer research, including 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), and emerging computational approaches. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, detailed methodologies, practical troubleshooting, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current best practices and highlighting the complementary strengths of different flux analysis frameworks, this guide aims to empower the design of robust studies that can unravel cancer metabolism and reveal novel therapeutic targets.

Understanding Metabolic Flux: Why It's a Cornerstone of Modern Cancer Biology

Metabolic flux is defined as the rate of metabolic reactions within a biological system, quantitatively describing the flow of carbon, energy, and electrons through metabolic networks [1] [2]. In the context of cancer research, quantifying these fluxes is paramount as it provides functional insights into how cancer cells reprogram their metabolism to support rapid growth, proliferation, and survival [3] [4]. Unlike static molecular measurements, metabolic fluxes capture the dynamic functional phenotype of cancer cells, revealing the operational status of metabolic pathways under various genetic and environmental conditions [1].

The study of metabolic fluxes, or fluxomics, represents the phenotypic outcome of complex cellular regulation and serves as a critical tool for understanding cancer metabolism, identifying therapeutic targets, and explaining mechanisms of drug resistance [1] [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the primary methodologies used for metabolic flux analysis in cancer research.

Comparative Analysis of Metabolic Flux Analysis Methodologies

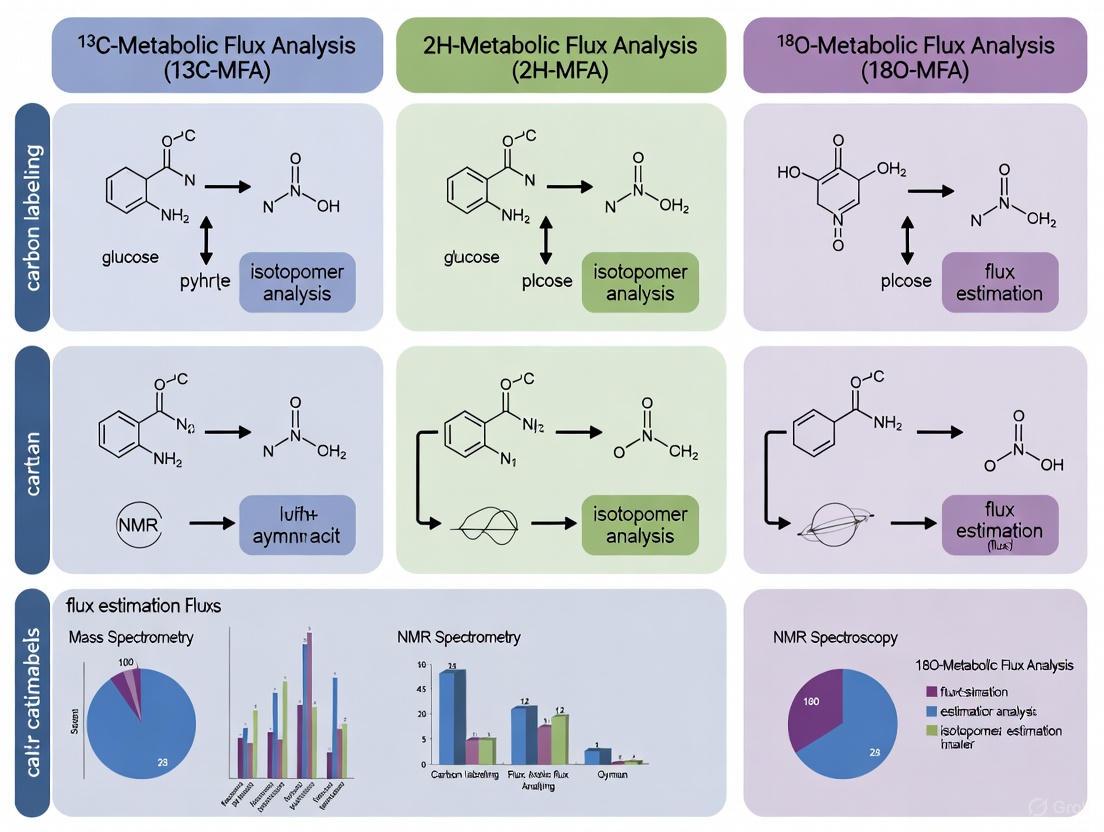

Several computational and experimental techniques have been developed to quantify in vivo metabolic fluxes. The table below compares the core principles, applications, and limitations of the primary methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Metabolic Flux Analysis Methodologies

| Method | Core Principle | Required State | Key Applications in Cancer Research | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [1] [2] | Uses stoichiometric models of metabolic networks and optimization algorithms (e.g., biomass maximization) to predict flux distributions. | Metabolic steady-state. | - Prediction of metabolic capabilities [2]- Exploration of gene knockout effects [5]- Modeling of ATP maximization with thermodynamic constraints [4] | - Predictive, not quantitative [1]- Relies on assumptions of cellular optimality [2] |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) [1] [2] | Quantifies fluxes by feeding cells (^{13})C-labeled substrates and measuring the resulting isotope patterns in intracellular metabolites. | Metabolic and Isotopic Steady-State. | - Gold standard for precise flux quantification in central carbon metabolism [2]- Investigating the Warburg effect/aerobic glycolysis [4]- Identifying metabolic bottlenecks and pathway dysregulation [6] | - Limited to systems that can reach isotopic steady-state [5]- Can be time-consuming for slow-growing cells [1] |

| Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) [1] [5] | Uses transient (^{13})C-labeling data before isotopic equilibrium is reached, solving with ordinary differential equations. | Metabolic Steady-State only. | - Flux analysis in systems with slow labeling dynamics [5]- Studying autotrophic organisms or complex culture conditions [5] | - Computationally intensive [1] [5]- Requires precise, time-resolved sampling [1] |

| Thermodynamics-based MFA (TMFA) [5] | Incorporates linear thermodynamic constraints (e.g., Gibbs free energy) with mass balance to determine feasible fluxes. | Metabolic steady-state. | - Identification of thermodynamically constrained bottleneck reactions [5]- Generating more physiologically relevant flux profiles [5] | - Requires thermodynamic data for reactions and metabolites [5] |

A key application in cancer research involves using these methods to investigate aerobic glycolysis, known as the Warburg effect, where cancer cells preferentially use glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation for energy production even in oxygen-rich conditions [3]. A 2025 study used 13C-MFA on 12 human cancer cell lines and found that the measured flux distribution could be reproduced by maximizing ATP consumption while considering a limitation of metabolic heat dissipation [4]. This suggests an advantage of aerobic glycolysis may be the reduction in metabolic heat generation during ATP regeneration, helping cancer cells maintain thermal homeostasis [4].

Experimental Protocols for Flux Analysis

The following sections detail the standard workflows for the two most common experimental flux analysis techniques.

Protocol for 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis

13C-MFA is considered the gold standard for accurate and precise flux quantification [2]. The experimental workflow is systematic and can be broken down into four key phases, as visualized below.

Diagram 1: 13C-MFA experimental workflow.

Phase 1: Cell Culture and Isotope Labeling

- Pre-culture and Tracer Preparation: Cells are first pre-cultured until they reach a metabolic steady state, where metabolite concentrations remain constant [1]. A (^{13})C-labeled substrate, such as [1,2-(^{13})C]glucose or [U-(^{13})C]glutamine, is prepared and introduced into the culture medium [1] [6].

- Isotopic Steady-State: The cells are cultivated until they reach an isotopic steady state, a point at which the incorporation of the (^{13})C tracer into intracellular metabolites becomes static [1]. For certain mammalian cells, this process can take several hours to a full day [1].

Phase 2: Metabolite Quenching and Extraction

- Rapid Quenching: Cellular metabolism is rapidly halted ("quenched") to preserve the in vivo state of metabolites. This is typically done using cold organic solvents like methanol, which instantly stops all enzymatic activity [3] [5].

- Metabolite Extraction: Intracellular metabolites are then extracted using a mixture of methanol and water [5]. This step is critical for obtaining a representative snapshot of the metabolome for subsequent analysis.

Phase 3: Metabolite Analysis via Mass Spectrometry

- Separation: The complex metabolite extract is often separated using Liquid Chromatography (LC) to reduce complexity and resolve isomers, which have identical mass but different structures [3].

- Detection and Quantification: The separated metabolites are ionized and analyzed by Mass Spectrometry (MS). The MS detects the mass isotopologue distributions (MIDs), which are the relative abundances of different isotopic forms of a metabolite (e.g., M+0, M+1, M+2) [5] [6]. This labeling pattern contains the information needed to infer metabolic fluxes.

Phase 4: Data Integration and Computational Modeling

- Flux Calculation: Experimentally measured MIDs and extracellular flux rates (e.g., glucose uptake, lactate secretion) are integrated into a stoichiometric model of the metabolic network [2] [6]. Software tools like INCA (Isotopomer Network Compartmental Analysis) are used to perform computational simulations that find the most probable set of intracellular fluxes that best fit the experimental data [6]. The result is a quantitative metabolic flux map [2].

Protocol for Inst-Metabolic Flux Analysis

INST-MFA is used when achieving isotopic steady-state is impractical or when studying systems with dynamic label incorporation [1]. Its workflow shares similarities with 13C-MFA but differs crucially in the first and last phases.

Diagram 2: INST-MFA experimental workflow.

- Transient Labeling and Sampling: The (^{13})C-labeled substrate is introduced, and cells are sampled at multiple, early time points (e.g., seconds or minutes) before the system reaches isotopic steady state [1].

- Dynamic Computational Modeling: Instead of using algebraic balance equations, INST-MFA applies ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to model how the isotopic labeling patterns of metabolites change over time [5]. This approach is computationally more demanding but provides flux information much faster than traditional 13C-MFA [1].

Metabolic Pathways and Flux in Cancer

Central carbon metabolism in cancer cells, including glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, is a primary focus of flux analysis. The diagram below illustrates key pathways and fluxes that are commonly reprogrammed.

Diagram 3: Key metabolic pathways and fluxes in cancer cells.

- Aerobic Glycolysis (The Warburg Effect): A classic hallmark of cancer metabolism, where flux from glucose to pyruvate is high, and a significant portion of pyruvate is converted to lactate by LDHA, even in the presence of oxygen [3]. 13C-MFA studies suggest this flux may be advantageous for managing metabolic heat dissipation [4].

- Glutaminolysis: Many cancer cells exhibit high uptake and metabolism of glutamine, which enters the TCA cycle in the mitochondria as alpha-ketoglutarate (AKG) to fuel bioenergetics and biosynthesis [6].

- Citrate Transport and Lipogenesis: Mitochondrial citrate, exported to the cytosol by the Citrate Transport Protein (CTP), is a critical source of acetyl-CoA for de novo fatty acid synthesis, supporting membrane production for rapid cell proliferation [6].

- Reductive Carboxylation: Under certain conditions, such as CTP deficiency or hypoxia, an unconventional flux is enabled where glutamine-derived AKG in the cytosol is converted back to citrate by IDH1 in a reductive reaction, supporting lipid synthesis [6].

- Anaplerosis: Flux through pyruvate carboxylase (PC) replenishes TCA cycle intermediates that are siphoned off for biosynthesis, a crucial anaplerotic reaction in many cancers [6].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of metabolic flux experiments requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table catalogues the essential solutions for the field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application in Flux Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers [1] [6] | [U-(^{13})C]Glucose, [1,2-(^{13})C]Glucose, [U-(^{13})C]Glutamine, [5-(^{13})C]Glutamine | Serves as the metabolic probe; the labeled carbon atoms are followed through metabolic pathways, enabling flux quantification. |

| Analytical Instrumentation [1] [3] | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), Gas Chromatography-MS (GC-MS), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Measures the mass isotopologue distributions (MIDs) of metabolites or their derivatives with high precision and sensitivity. |

| Software for Flux Modeling [1] [5] | INCA, 13CFLUX2, OpenFLUX, MetaboAnalyst | Performs computational modeling, simulates isotopic labeling patterns, and calculates the most probable metabolic flux maps from experimental data. |

| Metabolic Modulators [6] | CTP inhibitors, IDH1 inhibitors (e.g., GSK864) | Pharmacological tools used to perturb specific metabolic pathways, allowing researchers to probe flux flexibility and identify dependencies. |

| Cell Culture Consumables [5] | Ultra-Low Attachment dishes for spheroid culture, specialized culture media | Enables flux analysis in more physiologically relevant in vitro models, such as 3D spheroids, which can mimic tumor microenvironments. |

Metabolic flux analysis provides an indispensable, dynamic perspective on the functional state of cancer cell metabolism. While 13C-MFA remains the gold standard for precise flux quantification in controlled systems, methods like INST-MFA and FBA expand our capabilities to study more complex and dynamic biological questions. The continued refinement of these tools, coupled with advanced mass spectrometry and modeling software, is steadily enhancing our understanding of metabolic dysregulation in cancer. This knowledge is pivotal for identifying novel metabolic vulnerabilities and guiding the development of targeted cancer therapies.

The study of cancer metabolism has progressed significantly since Otto Warburg's seminal observation in the 1920s that tumor cells preferentially metabolize glucose to lactate even in the presence of oxygen—a phenomenon known as aerobic glycolysis or the Warburg effect [7]. This foundational discovery established altered metabolism as a hallmark of cancer, but contemporary research has revealed a far more complex and heterogeneous metabolic landscape than initially appreciated [8]. While the Warburg effect remains a recognized feature of many cancers, it represents just one manifestation of the extensive metabolic reprogramming that supports tumor growth and progression [9].

Modern understanding acknowledges that cancer metabolism is not a single, uniform entity but rather a spectrum of metabolic phenotypes shaped by multiple factors, including the cell of origin, specific genetic alterations, tissue context, and microenvironmental constraints [10] [8]. This review examines the key hallmarks of cancer metabolism through the lens of comparative methodological approaches, with particular emphasis on how advanced metabolic flux analysis techniques have revealed the remarkable plasticity and heterogeneity of tumor metabolism. We will systematically compare experimental methodologies that enable researchers to decode the complex metabolic networks driving cancer progression, providing a framework for selecting appropriate techniques for specific research questions in preclinical and clinical cancer metabolism studies.

Historical Perspective: From Warburg's Observations to Contemporary Metabolic Hallmarks

Warburg's original hypothesis posited that impaired mitochondrial function drove cancer cells toward glycolytic metabolism [7]. However, subsequent research has demonstrated that mitochondrial respiration remains functional—and often essential—in most cancers, with many tumors actively utilizing oxidative phosphorylation alongside glycolysis [7] [11]. The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle is not merely operational but serves critical anaplerotic (refilling) and cataplerotic (effluent) functions that support biosynthetic pathways [12] [8]. This refined understanding has expanded the conceptual framework of cancer metabolism beyond the Warburg effect to include multiple interconnected hallmarks:

- Deregulated uptake of glucose and amino acids driven by oncogenic signaling pathways [9]

- Metabolic flexibility and heterogeneity allowing adaptation to nutrient availability [10]

- Diversion of metabolites into biosynthetic pathways to support biomass production [9]

- Use of electron acceptors beyond oxygen and enhanced oxidative stress protection [9]

- Metabolic cross-talk between tumor cells and their microenvironment [9] [8]

- Integration with whole-body metabolism influencing tumor progression [9]

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and regulatory networks that govern these metabolic adaptations in cancer cells:

Figure 1: Regulatory networks in cancer metabolism. Key oncogenic signaling pathways (yellow) integrate with metabolic processes (blue, green, red) to coordinate metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. Arrowheads indicate activation, while flat ends indicate inhibition.

Comparative Analysis of Metabolic Flux Analysis Methodologies

Understanding cancer metabolism requires more than just measuring metabolite levels; it demands precise quantification of metabolic pathway activities and fluxes. The table below systematically compares the major methodological approaches used in cancer metabolism research:

Table 1: Comparison of Metabolic Flux Analysis Methods in Cancer Research

| Method | Key Measurable Parameters | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C Isotopic Tracing | Pathway fluxes, nutrient contributions, reaction rates | Cellular (can be subcellular with specific probes) | Minutes to hours | Mapping intracellular fluxes, quantifying pathway contributions [12] [11] | Direct measurement of metabolic activity; can resolve pathway branching | Typically requires cell culture or tissue extraction; limited spatial context in vivo |

| Stable Isotope-Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM) | Metabolic fate of specific nutrients, flux distributions | Cellular or tissue level | Hours | Comprehensive mapping of nutrient utilization networks [12] | Provides absolute quantification of nutrient fate | Complex data analysis; requires specialized expertise in modeling |

| Multi-Modality Imaging (PET/MRI/MRS) | Nutrient uptake, metabolite levels, vascular perfusion | Sub-millimeter to centimeter (whole body) | Minutes to hours | Clinical tumor detection, metabolic phenotyping, treatment monitoring [7] | Non-invasive; enables longitudinal studies in same subject; translates to clinical practice | Indirect measurement of metabolism; limited pathway resolution |

| Computational Flux Balance Analysis | Theoretical flux distributions, network capabilities, pathway vulnerabilities | Genome-scale (in silico prediction) | Steady-state predictions | Predicting metabolic vulnerabilities, integrating omics data, hypothesis generation [13] | Can model complete metabolic networks; enables in silico gene knockouts | Based on theoretical constraints; requires validation |

| Functional Genomics + Metabolomics | Gene-metabolite relationships, essential metabolic functions | Cellular | Days (depends on gene modulation) | Identifying genetic determinants of metabolism, synthetic lethality [10] | Directly links genotype to metabolic phenotype | May not account for microenvironmental influences |

Each methodology offers distinct advantages and limitations, with the optimal approach depending on the specific research question. 13C isotopic tracing provides the most direct measurement of metabolic fluxes, enabling researchers to quantify how nutrients are actually processed through various pathways [12]. This approach revealed, for instance, that while all melanoma cell lines exhibit the Warburg effect, they maintain functional TCA cycles and utilize glutamine as a significant anaplerotic substrate [11]. Furthermore, some melanoma lines under hypoxia even employ reverse (reductive) flux in the TCA cycle, allowing them to synthesize fatty acids from glutamine while converting glucose primarily to lactate [11].

Multi-modality imaging approaches, particularly positron emission tomography (PET) with various radiolabeled nutrients, enable non-invasive assessment of tumor metabolism in both preclinical models and clinical settings [7]. Beyond the commonly used [18F]FDG (a glucose analog), probes based on acetate, choline, methionine, and glutamine allow researchers to profile diverse metabolic dependencies across different tumor types [7]. When combined with complementary techniques like mass spectrometry, these imaging methods provide both spatial localization and biochemical specificity in metabolic studies.

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

13C Isotopic Tracing and Flux Analysis

Objective: To quantify metabolic fluxes in central carbon metabolism using stable isotope-labeled nutrients and computational modeling.

Protocol Details:

Cell Culture and Isotope Labeling:

- Culture cells in standard media until 70-80% confluent

- Replace media with identical composition except containing 13C-labeled nutrient (e.g., [U-13C]glucose, [1,2-13C2]glucose, or 13C5-glutamine)

- Typical isotope concentration: 10-25 mM for glucose, 2-4 mM for glutamine

- Incubation time: 1-24 hours (time course recommended for flux determination)

Metabolite Extraction:

- Rapidly wash cells with cold saline (0.9% NaCl) to remove extracellular isotopes

- Extract metabolites using cold methanol/acetonitrile/water mixtures (typically 40:40:20 v/v/v)

- Scrape cells, vortex vigorously, and centrifuge at 14,000×g for 15 minutes at 4°C

- Collect supernatant for analysis, evaporate to dryness, and reconstitute in appropriate solvent

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Analyze extracts using LC-MS or GC-MS systems

- For GC-MS: Derivatize samples using MSTFA or similar silylation reagents

- Monitor mass isotopomer distributions of key metabolites (e.g., lactate, alanine, citrate, malate, glutamate)

- Use extracted ion chromatograms to quantify relative abundances of different mass isotopomers

Flux Computation:

- Utilize software platforms such as Isotopomer Network Compartment Analysis (INCA) for metabolic flux modeling [14]

- Construct stoichiometric model of central carbon metabolism

- Fit simulated mass isotopomer distributions to experimental data using iterative algorithms

- Apply statistical tests (e.g., chi-square) to evaluate goodness of fit

Key Applications: This protocol enabled the discovery that WM35 melanoma cells utilize reductive glutamine metabolism for lipid synthesis under hypoxia [11] and revealed distinct metabolic phenotypes in patient-derived glioblastoma cells under ketogenic conditions [14].

Multi-Modality Metabolic Imaging

Objective: To non-invasively assess tumor metabolism in vivo using complementary imaging techniques.

Protocol Details:

Radiotracer Preparation and Administration:

- Select appropriate radiotracer based on biological question:

- [18F]FDG for glucose uptake

- 11C-acetate for TCA cycle flux and lipid synthesis

- 11C-glutamine for glutaminolysis

- 18F-fluorocholine for phospholipid metabolism

- Administer via intravenous injection at doses of 3.7-7.4 MBq/kg for preclinical studies

- Allow uptake period (typically 45-60 minutes for [18F]FDG)

- Select appropriate radiotracer based on biological question:

Image Acquisition:

- Anesthetize animal and position in scanner

- Acquire PET images with appropriate energy window settings

- Perform CT scan for anatomical co-registration and attenuation correction

- Optional: Acquire simultaneous MR images for improved soft tissue contrast

Image Reconstruction and Analysis:

- Reconstruct PET images using ordered-subset expectation maximization (OSEM) algorithm

- Co-register PET, CT, and/or MR images using rigid or non-rigid transformation

- Define volumes of interest (VOIs) for tumors and reference tissues

- Calculate standardized uptake values (SUVs) and tumor-to-background ratios

Data Interpretation:

- Correlate imaging findings with ex vivo analyses (histology, MS-based metabolomics)

- For longitudinal studies, use PERCIST criteria to assess treatment response

Key Applications: This approach demonstrated that 18F-FDG PET can monitor response to PI3K inhibition in breast cancer patients [7] and that combining HX4-PET (for hypoxia) with contrast-enhanced CT can classify lung tumors as normoxic or hypoxic [7].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for multi-modality metabolic analysis:

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for comprehensive analysis of cancer metabolism. Experimental systems (blue) are analyzed using multiple techniques (green), with computational integration (red) generating research outputs (yellow).

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cancer Metabolism Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functional Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Nutrients | [U-13C]glucose, [1,2-13C2]glucose, 13C5-glutamine, 2H7-glucose [11] [14] | 13C metabolic flux analysis, pathway mapping | Enable tracking of nutrient fate through metabolic networks; quantify pathway fluxes |

| Radiolabeled Tracers for PET | [18F]FDG, 11C-acetate, 11C-glutamine, 18F-fluorocholine [7] | Non-invasive imaging of nutrient uptake in vivo | Visualize and quantify spatial distribution of metabolic activities in tumors |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Oxamate (LDHA inhibitor), AZD3965 (MCT1 inhibitor), CPI-613 (mitochondrial metabolism) [12] [15] | Target validation, synthetic lethality studies | Probe metabolic dependencies; identify therapeutic vulnerabilities |

| Genetically Encoded Sensors | pHluorin (pH), iNAP (NAP+/NADPH), SoNar (NAD+/NADH) | Real-time monitoring of metabolite levels in live cells | Enable dynamic tracking of metabolic parameters with subcellular resolution |

| Cell Culture Media Formulations | Ketogenic media (low glucose, high ketones), plasma-like media [14] | Modeling physiological nutrient conditions | Recreate in vivo nutrient environments; study metabolic adaptation |

| Flux Analysis Software | Isotopomer Network Compartment Analysis (INCA), CellNetAnalyzer, COBRA Toolbox [14] | Computational flux modeling, network analysis | Convert isotopomer data into flux maps; predict network capabilities |

Metabolic Heterogeneity: Implications for Research and Therapy

The application of these diverse methodological approaches has consistently revealed extensive metabolic heterogeneity both between different cancer types and within individual tumors [10] [8]. This heterogeneity manifests at multiple levels:

Intertumoral Heterogeneity

Different cancer types display distinct metabolic preferences shaped by their tissue of origin and driver mutations. For example:

- Melanomas exhibit functional TCA cycles even under hypoxia and can perform reductive glutamine metabolism [11]

- KEAP1-mutant lung cancers demonstrate enhanced glutamine catabolism and resistance to oxidative stress [10]

- KRAS/STK11 co-mutant NSCLC shows addiction to carbamoyl-phosphate synthase-1 (CPS1) for pyrimidine synthesis [10]

- ASCL1-low small cell lung cancers with high MYC expression display enhanced guanosine synthesis and sensitivity to IMPDH inhibitors [10]

Intratumoral Heterogeneity

Within individual tumors, metabolic heterogeneity arises from:

- Regional nutrient gradients (oxygen, glucose, glutamine) [8]

- Stromal-tumor metabolic interactions [8]

- Cycling hypoxia/reoxygenation patterns [8]

- Clonal evolution and cooperation [8]

This spatial and temporal heterogeneity has profound implications for both diagnostic approaches and therapeutic strategies. Metabolic imaging of patient tumors, such as the use of 18F-FDG PET, frequently reveals substantial intra-tumoral heterogeneity in nutrient uptake and utilization [7]. Similarly, analysis of patient-derived xenografts demonstrates that each tumor fragment maintains a unique metabolomic signature, with even common driver mutations like BRAF failing to produce a consistent metabolic fingerprint across genetically diverse tumors [10].

Computational modeling suggests that cancer cells can acquire at least four distinct metabolic phenotypes characterized by different balances between catabolic and anabolic processes [13]:

- A predominantly catabolic phenotype (O) with vigorous oxidative processes

- A predominantly anabolic phenotype (W) with pronounced reductive activities

- A hybrid phenotype (W/O) exhibiting both high catabolic and anabolic activity

- A glutamine-oxidizing phenotype (Q) relying mainly on glutamine oxidation

Strikingly, carcinoma samples exhibiting hybrid metabolic phenotypes are often associated with the worst survival outcomes [13], highlighting the clinical relevance of metabolic heterogeneity.

The field of cancer metabolism has evolved far beyond the original Warburg effect to recognize the remarkable complexity and heterogeneity of tumor metabolic processes. This evolution has been driven by parallel advances in methodological approaches, each contributing unique insights into different aspects of cancer metabolism. No single methodology can fully capture the dynamic, spatially organized, and highly adaptable nature of tumor metabolism. Instead, researchers must strategically combine multiple approaches—from detailed 13C flux analysis in controlled model systems to non-invasive metabolic imaging in clinical settings—to develop a comprehensive understanding of cancer metabolic reprogramming.

The implications of this metabolic heterogeneity extend to both diagnostic approaches and therapeutic development. Metabolic profiling technologies offer promising avenues for improved cancer detection and patient stratification [16]. Furthermore, understanding the specific metabolic dependencies of different tumor subtypes may enable more targeted therapeutic interventions. However, the plasticity of cancer metabolism—the ability of tumor cells to adapt their metabolic strategies in response to therapeutic challenges—represents a significant barrier to successful treatment [13]. Future progress will likely require continued methodological innovation, particularly in techniques that can resolve metabolic heterogeneity at single-cell resolution and monitor metabolic adaptations in real time within relevant physiological contexts.

As methodological capabilities continue to advance, so too will our understanding of the complex metabolic networks that support cancer progression. This expanding knowledge offers the promise of novel diagnostic approaches and therapeutic strategies that exploit the metabolic vulnerabilities of cancer cells while sparing normal tissues, ultimately improving outcomes for cancer patients.

Metabolic flux analysis (MFA) provides a powerful computational framework for quantifying the flow of metabolites through biochemical networks, offering critical insights into the rewired metabolism of cancer cells. Unlike static metabolic measurements, flux analysis captures the dynamic functional state of cellular metabolism, revealing how cancer cells alter pathway utilization to support rapid proliferation, survive in harsh microenvironments, and develop resistance to therapies. In cancer research, these methods help resolve fundamental questions about why cancer cells prefer inefficient aerobic glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation (the Warburg effect), how metabolic dependencies arise in specific tumor types, and which network vulnerabilities might be exploited therapeutically. The integration of flux balance analysis (FBA) with genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) has become indispensable for predicting cellular phenotypes from metabolic reconstructions [17]. This guide compares the leading flux analysis methodologies, their experimental requirements, and their applications in cancer research to help scientists select appropriate approaches for their specific research questions.

Comparative Analysis of Flux Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of Major Flux Analysis Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Data Requirements | Cancer Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Constraint-based optimization of biochemical network fluxes | Genome-scale metabolic model, growth conditions | Prediction of essential genes/reactions, synthetic lethality [18] | Genome-scale coverage, no kinetic parameters needed |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) | Isotope labeling patterns + mathematical modeling | 13C-labeled substrates, LC-MS/GCMs measurements | Quantifying Warburg effect, pathway fluxes in cell lines [4] | Direct experimental validation, absolute flux quantification |

| Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) | Structural analysis of network pathways | Stoichiometric matrix, metabolic model | Pathway identification in adaptive networks [19] | Identifies all possible pathways, reveals network redundancy |

| Dynamic FBA (dFBA) | FBA extended with time-varying constraints | Kinetic parameters, extracellular conditions | Modeling tumor metabolism dynamics [19] | Captures transient metabolic states |

| MALDI-MSI | Spatial mapping of metabolite distributions | Tissue sections, appropriate matrix | Spatial metabolomics, tumor heterogeneity [20] | Preserves spatial context, detects 1000+ metabolites |

| TIObjFind | Integrates MPA with FBA to infer objective functions | Experimental flux data, metabolic model | Identifying metabolic objectives in changing environments [19] | Data-driven objective functions, improved experimental alignment |

Technical Requirements and Outputs

Table 2: Technical Specifications and Output Data

| Method | Software Tools | Measurement Type | Spatial Resolution | Flux Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBA | Fluxer, COBRA Toolbox, OptFlux | Computational predictions | Network-level | Steady-state fluxes [17] |

| 13C-MFA | INCA, OpenFLUX | Experimental + computational | Bulk cellular | Absolute intracellular fluxes [4] |

| MPA | CellNetAnalyzer, TIObjFind | Computational pathway enumeration | Network-level | Elementary flux modes [19] |

| MALDI-MSI | SCiLS, MSiReader | Direct metabolite detection | 10-20 μm (near single-cell) [20] | Relative abundances, spatial distributions |

| minRerouting | Custom algorithms | Computational predictions of rewiring | Network-level | Flux changes in genetic perturbations [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Flux Analyses

13C-MFA Protocol for Cancer Cell Lines

Objective: Quantify central carbon metabolism fluxes in cancer cells under normoxic conditions to investigate aerobic glycolysis [4].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Cell Culture: Grow cancer cell lines in standardized media with uniform 13C-glucose (e.g., [U-13C]glucose)

- Isotope Steady-State: Maintain cells for ≥48 hours to achieve isotopic steady-state in intracellular metabolites

- Metabolite Extraction: Quench metabolism rapidly using cold methanol, extract intracellular metabolites

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze metabolite labeling patterns using LC-MS with appropriate ionization modes

- Flux Calculation: Compute flux distributions using computational platforms (e.g., INCA) that fit simulated to experimental labeling patterns

- Statistical Validation: Assess flux solution quality using Monte Carlo sampling and goodness-of-fit metrics

Key Technical Considerations: Ensure proper isotope propagation time, normalize measurements to cell count/protein content, use multiple tracer substrates (glucose, glutamine) for comprehensive coverage [4].

Genome-Scale FBA with Fluxer

Objective: Predict system-wide metabolic fluxes and identify essential reactions using genome-scale models [17].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Model Selection/Upload: Choose appropriate GEM from BiGG database or upload custom SBML model

- Constraint Definition: Set nutrient availability and environmental conditions matching experimental setup

- Objective Function: Define biological objective (e.g., biomass maximization, ATP production)

- FBA Execution: Run flux balance analysis to obtain optimal flux distribution

- Visualization: Generate spanning trees, dendrograms, or complete graphs of flux networks

- Knock-out Analysis: Simulate reaction deletions to identify synthetic lethal pairs [18] [17]

Key Technical Considerations: Validate predictions with experimental growth data, check for multiple optimal solutions, incorporate transcriptomic data if available for context-specific modeling [17].

MALDI-MSI for Spatial Metabolomics

Objective: Map spatial distributions of metabolites in tumor tissues to characterize metabolic heterogeneity [20].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Tissue Preparation: Flash-freeze fresh tumor biopsies, cryosection at 5-20 μm thickness

- Matrix Application: Spray with appropriate matrix (CHCA for peptides, DHB for lipids/glycans)

- MALDI Analysis: Acquire mass spectra across tissue surface with 10-100 μm spatial resolution

- Data Processing: Normalize spectra, align to histopathological annotations

- Image Generation: Reconstruct ion images for metabolites of interest

- Integration: Correlate metabolic patterns with tumor regions and clinical features

Key Technical Considerations: Optimize matrix crystallization, use internal standards for semi-quantitation, validate metabolite identities with MS/MS [20].

Metabolic Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Aerobic Glycolysis in Cancer Cells - This pathway illustrates the Warburg effect, showing preferential flux of pyruvate to lactate rather than mitochondria, with ATP generation primarily through substrate-level phosphorylation [4].

Diagram 2: Synthetic Lethality Concept - This shows how simultaneous inhibition of two reactions (Reaction 1 and 2) abrogates growth, while single knockouts are viable through metabolic rewiring, revealing potential combination therapy targets [18].

Diagram 3: Integrated Flux Analysis Workflow - This workflow shows how experimental data and computational modeling are integrated to generate predictive flux maps that require biological validation [4] [17] [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Flux Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | [U-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine | 13C-MFA substrate for flux quantification | Ensure isotopic purity >99%, optimize concentration [4] |

| MALDI Matrices | CHCA, DHB, Sinapinic Acid | Enable soft ionization of metabolites | Match matrix to analyte class; CHCA for peptides, DHB for lipids [20] |

| Cell Culture Media | DMEM, RPMI-1640 with defined components | Consistent nutrient availability for FBA | Use dialyzed FBS to control nutrient composition [4] |

| MS Calibration Standards | ProteoMass LTQ/FT-Hybrid | Mass accuracy calibration for metabolomics | Use appropriate mass range standards for small molecules [20] |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | 2-DG, oligomycin, metformin | Experimental validation of flux predictions | Titrate concentration to achieve partial inhibition [18] |

| Genome-Scale Models | BiGG Models, Recon3D | Computational framework for FBA | Curate models for specific cell lines [17] |

Flux analysis methods provide complementary capabilities for dissecting cancer metabolism, from genome-scale predictions to spatially resolved measurements. The optimal method depends on the specific research question, with FBA offering system-wide predictions of network capabilities, 13C-MFA providing quantitative flux measurements, and MALDI-MSI revealing tumor heterogeneity. Integration of multiple approaches through frameworks like TIObjFind offers the most powerful approach for identifying cancer-specific metabolic dependencies. As these technologies advance, particularly with improved spatial resolution and integration with machine learning, flux analysis will continue to uncover novel therapeutic targets for cancer treatment.

In the quest to understand and target cancer metabolism, researchers are equipped with a powerful arsenal of analytical techniques. Among these, metabolomics and metabolic flux analysis (MFA) stand out as complementary approaches that together provide a comprehensive view of cellular metabolic activity [16] [21]. Metabolomics offers a "snapshot" of the metabolic state by measuring the concentrations of small molecules (metabolites) within a biological system at a specific time point [16]. This approach captures the functional readout of cellular processes and can identify metabolic biomarkers indicative of early-stage cancer [16]. However, concentration data alone cannot reveal the rates at which metabolites are produced and consumed through metabolic pathways. This is where metabolic flux analysis provides the "dynamic" perspective, quantifying the in vivo rates of biochemical reactions through metabolic networks [1] [21]. By integrating these complementary approaches, cancer researchers can connect static metabolic profiles to the underlying metabolic dynamics that drive tumor progression and therapeutic resistance.

The importance of this integrated approach stems from the fundamental role of metabolic reprogramming in cancer development and progression. Cancer cells exhibit remarkably altered metabolism compared to normal tissues, characterized by increased nutrient uptake, enhanced glycolysis, and redirected biosynthetic pathways to support rapid proliferation [22] [13]. These adaptations are not merely consequences of transformation but actively contribute to the malignant phenotype. Understanding both the metabolic state (through metabolomics) and the metabolic flux (through MFA) provides critical insights for developing targeted therapies that exploit the metabolic vulnerabilities of cancer cells [22].

Technical Foundations: Core Methodologies and Principles

Metabolomics: Capturing the Metabolic State

Metabolomics involves the comprehensive analysis of metabolites, which are the intermediate and end products of cellular regulatory processes. As such, their concentrations represent the functional manifestation of genetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic regulation [16]. The metabolomics workflow typically involves sample collection, metabolite extraction, data acquisition using analytical platforms, and computational data analysis.

The primary analytical platforms used in metabolomics are mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [16]. MS-based approaches, often coupled with separation techniques like liquid chromatography (LC) or gas chromatography (GC), offer high sensitivity and the ability to detect thousands of metabolites simultaneously. NMR spectroscopy, while generally less sensitive, provides non-destructive analysis, superior structural information, and quantitative capabilities without requiring extensive sample preparation [16]. The choice between these techniques depends on the specific research question, with MS often preferred for comprehensive profiling and NMR favored for targeted analysis or when sample preservation is important.

A key advantage of metabolomics in cancer research is its sensitivity to early metabolic changes that may precede clinical manifestations of disease [16]. Even a single genetic variation can cause significant changes in metabolite levels, earning metabolites the moniker "genomic canaries" [16]. This sensitivity, combined with the potential for non-invasive sample collection from blood, urine, or other biofluids, makes metabolomics particularly promising for early cancer detection and monitoring therapeutic responses.

Metabolic Flux Analysis: Quantifying Metabolic Dynamics

Metabolic flux analysis comprises a suite of computational and experimental methods for quantifying the rates of metabolic reactions in living cells. The most established approach is 13C-MFA, which utilizes stable isotope tracers (typically 13C-labeled substrates) to track the flow of atoms through metabolic networks [1] [21]. When cells are cultured with a labeled substrate such as [1,2-13C]glucose or [U-13C]glutamine, the 13C atoms are incorporated into metabolic intermediates and products in patterns that reflect the activities of different metabolic pathways [21]. These labeling patterns are measured using MS or NMR, and computational models are used to infer the metabolic fluxes that best explain the experimental data.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Flux Analysis Techniques

| Method | Tracers | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Not required | Assumed | Not required | Genome-scale prediction of flux distributions [1] |

| 13C-MFA | 13C-labeled | Assumed | Assumed | Detailed quantification of central carbon metabolism [1] [21] |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) | 13C-labeled | Assumed | Not required | Short-term labeling experiments; systems with slow isotope equilibration [1] |

| Dynamic MFA (DMFA) | Optional | Not assumed | Not assumed | Non-steady state systems; industrial bioprocesses [1] [23] |

The computational framework of 13C-MFA involves formulating a stoichiometric model of the metabolic network and simulating the labeling patterns of metabolites for a given set of fluxes [21] [24]. The model parameters (fluxes) are estimated by minimizing the difference between simulated and measured labeling patterns, typically using least-squares regression [21]. This approach has been greatly facilitated by the development of computational tools such as Metran and INCA, which implement efficient algorithms for simulating isotopic labeling and estimating fluxes [21].

For systems that are not at metabolic steady state, such as fed-batch cultures or rapidly adapting cell populations, dynamic metabolic flux analysis (DMFA) approaches have been developed [23]. DMFA can directly analyze time-series concentration measurements without requiring data smoothing or estimation of average extracellular rates, making it particularly valuable for capturing metabolic transitions during disease progression or therapeutic intervention [23].

Comparative Analysis: Strengths, Limitations, and Complementarity

Capabilities and Constraints of Each Approach

Table 2: Direct Comparison of Metabolomics and Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Feature | Metabolomics | Metabolic Flux Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Output | Metabolite concentrations (snapshots) | Reaction rates (fluxes) through pathways |

| Temporal Resolution | Static (single time point) | Dynamic (integrated over labeling period) |

| Sample Requirements | Diverse samples (tissues, biofluids) | Typically cell cultures or perfused tissues |

| Analytical Platforms | MS, NMR | MS, NMR with isotope tracing |

| Network Coverage | Comprehensive (untargeted) or focused (targeted) | Defined by network model used for flux estimation |

| Key Strengths | Non-invasive potential; biomarker discovery; high sensitivity [16] | Functional insight into pathway activities; quantitation of metabolic fluxes [21] |

| Major Limitations | Does not directly reveal fluxes; influenced by external factors [16] | Experimentally demanding; requires specialized computational tools [1] |

Metabolomics excels at providing comprehensive profiles of metabolic states across diverse sample types, including clinical specimens that may be difficult to obtain. Its non-invasive potential—using blood, urine, or other accessible biofluids—makes it particularly attractive for clinical translation [16]. However, a significant limitation is that metabolite concentrations alone do not directly reveal the fluxes through metabolic pathways. Two different flux states can theoretically result in similar concentration profiles, and concentration changes do not necessarily correlate with flux changes due to complex regulatory mechanisms.

Metabolic flux analysis directly addresses this limitation by quantifying reaction rates, but comes with its own constraints. 13C-MFA experiments require specialized isotopic tracers and controlled culture conditions, typically using cell lines rather than complex tissues [21]. The need for metabolic and isotopic steady state in traditional 13C-MFA limits its application to dynamically changing systems, though INST-MFA and DMFA are extending these boundaries [1] [23]. Additionally, flux estimation depends on having an accurate metabolic network model, and the computational complexity can be a barrier for researchers without specialized expertise.

Synergistic Integration in Cancer Research

The true power of these approaches emerges when they are integrated, leveraging their complementary strengths to overcome their individual limitations. For example, metabolomic profiling can identify metabolites with altered concentrations in cancer cells, pointing to pathways that may be dysregulated. Subsequent flux analysis can then determine whether these concentration changes result from altered production, consumption, or both, providing mechanistic insight into the metabolic reprogramming.

This synergy is particularly valuable for understanding cancer metabolic heterogeneity and plasticity. Cancer cells can dynamically shift between different metabolic phenotypes—such as glycolytic, oxidative, or hybrid states—to adapt to environmental challenges and therapeutic interventions [13]. Combining metabolomic snapshots across time points with flux analysis can capture both the instantaneous metabolic state and the underlying flux dynamics that enable these adaptations. For instance, a study of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in lung cancer cells combined time-course metabolomics with constraint-based modeling to identify dynamic metabolic vulnerabilities, including stage-specific dependencies on glycolytic enzymes and α-ketoglutarate transport [25].

Research Applications in Cancer Biology

Elucidating Metabolic Rewiring in Cancer

The integrated application of metabolomics and flux analysis has dramatically advanced our understanding of how cancer cells reprogram their metabolism to support rapid proliferation, survival, and metastasis. Beyond the well-known Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis), these approaches have revealed numerous other metabolic alterations in cancer, including:

Enhanced glutamine metabolism: Flux analysis has shown that many cancer cells rely on glutamine not only as a nitrogen source but also to replenish TCA cycle intermediates through anaplerosis [22] [21]. In some contexts, particularly under hypoxia, glutamine can undergo reductive carboxylation to support lipid synthesis [22].

Dysregulated serine and glycine metabolism: Metabolomic profiling identified elevated levels of serine and glycine in some cancers, and flux analysis revealed that certain breast cancers and melanomas with amplification of PHGDH (phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase) divert substantial glucose carbon into serine and glycine synthesis [22].

Altered lipid metabolism: Combined metabolomic and flux analyses have demonstrated that cancer cells can enhance both fatty acid synthesis and oxidation, with different subtypes relying on different lipogenic strategies [13].

Oncometabolite accumulation: Metabolomics has identified several "oncometabolites"—metabolites that accumulate due to mutations in metabolic enzymes and contribute to tumorigenesis. These include 2-hydroxyglutarate (from mutant IDH), fumarate (from FH mutations), and succinate (from SDH mutations) [22]. Flux analysis helps elucidate how these accumulations alter broader metabolic networks.

Identifying Metabolic Vulnerabilities and Therapeutic Targets

The integration of metabolomics and flux analysis is proving invaluable for identifying cancer-specific metabolic vulnerabilities that can be exploited therapeutically. For instance:

Targeting glycolytic dependencies: Metabolomic profiling often reveals elevated lactate levels in aggressive cancers, and flux analysis can quantify the extent to which these cells rely on glycolysis versus oxidative phosphorylation. This information guides the use of glycolytic inhibitors, which may be particularly effective against tumors with specific metabolic phenotypes [22] [25].

Exploiting glutamine addiction: Many cancers exhibit enhanced glutamine uptake and metabolism, which can be detected through metabolomics and quantified through flux analysis. This has led to the development of glutaminase inhibitors, which show promise in preclinical models and are being evaluated in clinical trials [22].

Targeting antioxidant systems: Metabolomics can reveal alterations in redox-active metabolites, while flux analysis can quantify flux through pathways that generate NADPH or glutathione. This combined approach has identified dependencies on antioxidant pathways in some cancers, suggesting therapeutic opportunities [13].

Combination therapies: Integrated metabolic analyses can inform rational combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple metabolic vulnerabilities. For example, a study of triple-negative breast cancer predicted that simultaneous inhibition of both OXPHOS and glycolysis would be more effective than targeting either alone, a prediction subsequently validated experimentally [13].

Essential Methodologies and Research Reagents

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

Typical Workflow for 13C-MFA in Cancer Cells [21]:

Cell Culture and Labeling: Culture cancer cells with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [U-13C]glucose, [1,2-13C]glucose, or 13C-glutamine) until isotopic steady state is reached (typically 24-72 hours for mammalian cells).

Sample Collection and Quenching: Rapidly collect cells and quench metabolism, typically using cold methanol or other organic solvents.

Metabolite Extraction: Extract intracellular metabolites using appropriate solvent systems, often methanol:water:chloroform mixtures.

Analysis of Isotopic Labeling: Analyze metabolite labeling patterns using LC-MS or GC-MS. Common targets include glycolytic intermediates, TCA cycle intermediates, amino acids, and nucleotides.

Measurement of External Rates: Quantify nutrient consumption and product secretion rates throughout the experiment.

Flux Estimation: Use computational software (e.g., INCA, Metran) to estimate metabolic fluxes that best fit the measured labeling patterns and external rates.

Statistical Analysis and Validation: Evaluate flux confidence intervals and validate model predictions through independent experiments.

Key Considerations for Experimental Design [21]:

- Selection of appropriate isotopic tracers depends on the metabolic pathways of interest. For central carbon metabolism, [1,2-13C]glucose or [U-13C]glucose are commonly used.

- The duration of labeling must be sufficient to reach isotopic steady state in the metabolites of interest.

- Careful measurement of cell growth rates and external fluxes is critical for accurate flux estimation.

- Experimental replicates are essential for assessing the precision of flux estimates.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Metabolomics and Flux Analysis

| Category | Specific Examples | Purpose/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose, 13C-Glutamine | Track carbon fate through metabolic pathways [1] [21] |

| Analytical Instruments | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR | Measure metabolite concentrations and isotopic labeling [16] [1] |

| Metabolomics Databases | HMDB, Metlin, KEGG | Metabolite identification and pathway annotation [16] |

| Flux Analysis Software | INCA, Metran, OpenFLUX | Estimate metabolic fluxes from isotopic labeling data [1] [21] |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Tools | COBRA Toolbox, CellNetAnalyzer | Predict flux distributions in genome-scale models [24] [25] |

| Genome-Scale Models | Recon3D, iMM904 | Comprehensive maps of human metabolism for constraint-based modeling [26] [25] |

Conceptual Framework and Visualization

The relationship between metabolomics and flux analysis, along with their application in cancer metabolism research, can be visualized through the following conceptual framework:

Conceptual Framework Integrating Metabolomics and Flux Analysis in Cancer Research

This framework illustrates how metabolomics and flux analysis provide complementary data types that, when integrated through multi-omics approaches, yield mechanistic insights into cancer phenotypes. These insights ultimately enable the identification of therapeutic targets that exploit metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

The field of cancer metabolism research continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends promising to enhance the integration of metabolomics and flux analysis:

Single-cell metabolomics and flux analysis: Current methods primarily analyze population averages, masking cellular heterogeneity. Emerging technologies for single-cell metabolomics and flux analysis will enable investigation of metabolic heterogeneity within tumors and its functional consequences [25].

Dynamic flux measurements in complex systems: Advances in INST-MFA and DMFA are extending flux analysis to more physiologically relevant systems, including co-cultures, 3D organoids, and in vivo models [1] [23].

Integration with other omics technologies: Combining metabolomics and flux analysis with genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics provides a more comprehensive view of how genetic alterations translate to functional metabolic phenotypes [16] [25].

Machine learning and advanced computational methods: Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches are being developed to enhance flux estimation, predict metabolic vulnerabilities, and identify novel metabolic biomarkers [24].

Clinical translation: Efforts are underway to develop simplified flux assays that could be applied in clinical settings for cancer diagnosis, stratification, and monitoring of therapeutic responses [16].

In conclusion, metabolomics and metabolic flux analysis offer complementary and powerfully synergistic approaches for investigating cancer metabolism. Metabolomics provides detailed snapshots of metabolic states, while flux analysis reveals the dynamic flows through metabolic pathways. As these technologies continue to advance and become more accessible, their integrated application will undoubtedly yield deeper insights into cancer biology and contribute to the development of novel metabolism-targeted therapies. For cancer researchers, mastering both approaches and their intersection represents a valuable investment in tackling the complexity of cancer metabolism.

A Practical Guide to Key Flux Analysis Methods and Their Cancer Applications

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA): Principles, Workflow, and Required Inputs

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as the gold-standard technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells under metabolic quasi-steady state conditions [21] [27]. In the field of cancer research, it plays a pivotal role in uncovering the metabolic rewiring that enables cancer cells to adapt to their microenvironment, maintain high rates of proliferation, and resist treatments [21]. Unlike methods that merely measure metabolite levels, 13C-MFA quantifies the actual in vivo rates of enzymatic reactions and metabolic transport, providing a functional readout of cellular phenotype [28]. This quantitative capability is crucial for understanding how aggressive cancers, such as glioblastoma, reprogram their metabolism to fuel growth, as demonstrated by recent studies infusing 13C-labelled glucose into patients to map metabolic differences between tumors and healthy cortical tissue [29].

The fundamental principle of 13C-MFA is that feeding cells with 13C-labeled substrates, such as glucose or glutamine, generates unique isotopic patterns in downstream metabolites. These patterns are determined by the activity of the metabolic pathways through which the labeled atoms travel [21] [28]. By measuring these labeling patterns and applying computational models, researchers can infer the precise fluxes through the network of central carbon metabolism, offering an unparalleled view of metabolic function in cancer cells [21] [28].

Core Principles and Comparative Landscape of Metabolic Flux Methods

The Principle of 13C-MFA

13C-MFA is fundamentally a parameter estimation problem where fluxes are determined by finding the values that best fit the simulated isotopic labeling data to the experimental measurements [28]. The relationship between fluxes and labeling patterns is complex and non-intuitive, necessitating sophisticated modeling frameworks. The core mathematical problem can be summarized as an optimization task where the difference between the model-simulated (x) and experimentally measured (xM) isotopic labeling data is minimized, subject to stoichiometric constraints (S·v = 0) that describe the metabolic network [28]. The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework, a key computational innovation, allows for the efficient simulation of isotopic labeling in large-scale metabolic networks by breaking down the problem into smaller, computable subsets, making comprehensive flux analysis feasible [30].

Classification of Metabolic Fluxomics Methods

The field of metabolic fluxomics has evolved into a diverse family of methods, each with distinct applications and capabilities [28]. The table below compares the major types.

Table 1: Classification of Metabolic Fluxomics Methods

| Method | Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Fluxomics (Isotope Tracing) | Deducing pathway activity by comparing isotopic data without full quantitative flux estimation [28]. | Rapid, intuitive assessment of pathway activity changes [28]. |

| 13C Flux Ratio (FR) Analysis | Calculating relative flux fractions at metabolic branch points from isotopic patterns [28]. | Analysis when network topology is unclear or metabolite outflow is hard to measure [28]. |

| 13C Kinetic Flux Profiling (KFP) | Estimating absolute fluxes by modeling the exponential incorporation of label into metabolite pools, requiring pool size measurement [28]. | Quantifying fluxes in sequential linear reactions or small subnetworks [28]. |

| 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) | Determining absolute, global network fluxes by fitting complete labeling data to a metabolic model [28]. | Gold-standard for comprehensive, quantitative flux maps under steady-state conditions [21] [28]. |

| Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) | A version of 13C-MFA that models transient labeling before isotopic steady-state is reached [28]. | Systems with short-lived metabolic states or large, slow-to-label metabolite pools [28]. |

The 13C-MFA Workflow: From Experiment to Flux Map

The process of conducting a 13C-MFA study is a concerted sequence of experimental and computational stages [30]. The workflow can be visualized as follows, showing the pathway from initial cell culture to the final flux map.

Figure 1: The 13C-MFA Workflow. The process integrates wet-lab experiments (blue) to generate data (green), leading to computational analysis (red) and final results (yellow).

Experimental Design and Tracer Experiment

The first step involves designing the experiment, which includes selecting appropriate 13C-labeled substrates (tracers). A solution of uniformly labeled [U-13C]glucose is a common choice, as used in recent human glioblastoma studies [29]. The cells are then cultivated in a controlled environment with this tracer, typically until they reach metabolic steady-state, where both metabolic fluxes and intracellular metabolite concentrations are constant [30].

Analytical Phase: Measuring External Rates and Isotopic Labeling

After the labeling experiment, the process splits into two parallel tracks for data collection:

- Measurement of External Rates: This involves quantifying nutrient uptake (e.g., glucose, glutamine) and product secretion (e.g., lactate, ammonium) rates. These rates provide critical constraints for the flux model. For proliferating cells, these are calculated based on changes in metabolite concentrations and cell growth over time [21].

- Measurement of Isotopic Labeling: Cells are rapidly harvested and metabolism is quenched. Intracellular metabolites are extracted and analyzed using techniques like Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) or Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) to determine the 13C-labeling patterns (isotopomer distributions) of key metabolites [29] [21] [30]. This step generates the rich dataset that informs on intracellular pathway activity.

Computational Phase: Model-Based Flux Estimation

The computational core of 13C-MFA involves several steps [30]:

- Model Definition: A stoichiometric model of the central carbon metabolism is constructed, including atom transitions for each reaction.

- Flux Estimation: Using software tools, an iterative least-squares fitting procedure is performed. The model simulates labeling patterns for a given set of flux values, and these are compared to the experimental data (

E). The fluxes (v) are adjusted until the difference is minimized, subject to the stoichiometric constraints (S·v = 0) and the measured external rates (F) [28] [30]. - Statistical Validation: The goodness-of-fit of the model is evaluated, and confidence intervals for the estimated fluxes are determined, often using statistical methods like Monte Carlo simulation [30]. The final output is a quantitative flux map.

Key Inputs and Reagents for a 13C-MFA Study

Successful execution of 13C-MFA relies on a suite of specific reagents, tools, and data inputs. The table below details the essential components of the "Scientist's Toolkit" for this technique.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Inputs for 13C-MFA

| Item | Function / Description | Example in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Substrates with specific carbon atoms replaced with 13C; the source of the isotopic label. | [U-13C]Glucose, [1,2-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glutamine; used to trace carbon fate [29] [21]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Analytical instrument for measuring the mass-to-charge ratio of ions; used to detect isotopic enrichment in metabolites. | LC-MS or GC-MS systems for quantifying 13C-isotopomer distributions of TCA cycle intermediates and other metabolites [29] [21]. |

| Cell Culture System | A controlled environment for growing cells during the tracer experiment. | 2D monolayers or 3D spheroids; the latter better represent in-vivo tumor microenvironments [31]. |

| Metabolic Network Model | A mathematical representation of the metabolic pathways under investigation, including stoichiometry and atom mapping. | A curated model of central carbon metabolism (glycolysis, TCA cycle, pentose phosphate pathway, etc.) [27]. |

| 13C-MFA Software | Computational tool for simulating isotopic labeling and estimating fluxes from experimental data. | OpenFLUX2, 13CFLUX2, INCA, Metran; used to solve the inverse problem of flux estimation [32] [30]. |

| Extracellular Rate Data | Quantified rates of nutrient consumption and by-product secretion. | Glucose uptake rate, lactate secretion rate; provide constraints for the flux model [21]. |

Software and Modeling: Enabling Flux Quantification

The computational aspect of 13C-MFA is enabled by sophisticated software packages and a move towards standardization. These tools handle the complex tasks of simulating labeling patterns and performing the statistical fitting required for flux estimation.

Table 3: Comparison of 13C-MFA Computational Approaches and Software

| Software / Approach | Type / Description | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| OpenFLUX2 | Open-source software for 13C-MFA [30]. | Supports analysis of both Single (SLE) and Parallel Labeling Experiments (PLEs); uses EMU framework; improves flux precision via PLEs [30]. |

| 13CFLUX2 | High-performance simulation toolbox [32]. | A "headless" framework integrated into service-oriented workflow systems for high-throughput flux analysis [32]. |

| FluxML | A universal, open modeling language for 13C-MFA [27]. | Platform-independent format for unambiguous model definition, exchange, and reproducibility; not software itself but a language standard [27]. |

| Parallel Labeling Experiments (PLEs) | An experimental/computational strategy using multiple tracers simultaneously or in parallel [30]. | Integrates complementary data to significantly improve flux resolution and accuracy compared to single-tracer experiments [30]. |

| Automated Data Pipelines | Integrated software solutions for processing raw MS data [31]. | Tools like Symphony Data Pipeline automate file conversion, peak detection, and data upload, reducing errors and saving time in data pre-processing [31]. |

The drive for better reproducibility and model sharing has led to initiatives like FluxML, an implementation-independent language designed to digitally codify all data required for a 13C-MFA study, ensuring that models are fully documented and reusable [27].

Application in Cancer Research: A Case Study on Brain Tumors

The power of 13C-MFA in revealing cancer-specific metabolism is powerfully illustrated by a recent 2025 study on glioblastoma (GBM) [29]. In this work, researchers infused patients with [U-13C]glucose during surgical resection and also conducted parallel studies in mouse models. By comparing the labeling patterns in healthy cortex and glioma tissues, they uncovered a profound metabolic rewiring. The study demonstrated that while the healthy cortex uses glucose carbon for physiological processes like TCA cycle oxidation and neurotransmitter synthesis, gliomas downregulate these pathways. Instead, the tumors scavenge amino acids from the environment and repurpose glucose carbons to synthesize nucleotides, which are essential for proliferation and invasion [29].

This application highlights the complete 13C-MFA workflow: the use of a specific tracer ([U-13C]glucose), measurement of isotopic patterns via MS, and computational modeling to generate a quantitative flux map that directly compares healthy and diseased tissue. Furthermore, the study showed therapeutic potential by demonstrating that targeting this rewiring through dietary modulation could slow tumor growth and augment standard therapy in mice [29]. The metabolic differences discovered are visualized in the pathway below.

Figure 2: Metabolic Rewiring in Glioblastoma. 13C-MFA reveals GBM shifts glucose use away from energy production and toward biomass generation, while scavenging external nutrients [29].

Metabolic flux analysis (MFA) represents a cornerstone technique in systems biology that enables the quantitative determination of intracellular reaction rates (fluxes) within biochemical networks [33]. By quantifying how metabolites flow through pathways, MFA provides unparalleled insights into the functional metabolic phenotype of cells, tissues, or organisms. This approach has become indispensable for understanding how metabolism is rewired in diseases like cancer and for identifying potential therapeutic targets [21]. The integration of stable isotope tracers, particularly those containing 13C, with advanced computational modeling has transformed MFA from a theoretical concept into a powerful empirical tool that can resolve complex metabolic behaviors in living systems [1] [33].

Two principal methodological frameworks have emerged for conducting 13C-based flux analysis: steady-state metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) and isotopically non-stationary metabolic flux analysis (INST-MFA). While both approaches share the common goal of quantifying metabolic fluxes, they differ fundamentally in their experimental requirements, underlying assumptions, and computational frameworks [1] [34]. The choice between these methods carries significant implications for experimental design, resource allocation, and the biological questions that can be addressed effectively. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of these two powerful methodologies, with particular emphasis on their application in cancer research where understanding metabolic reprogramming has become a major focus [35] [36] [21].

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Steady-State 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

13C-MFA operates under two critical assumptions: metabolic steady state (constant metabolite concentrations and reaction fluxes over time) and isotopic steady state (constant isotopomer distributions in metabolic pools) [1] [33]. In this approach, cells are cultured with 13C-labeled substrates until the isotopic labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites stabilize, which typically requires several hours to days depending on the biological system and growth rate [21]. The resulting steady-state isotopomer distributions provide a "snapshot" of the metabolic network's operation, with different flux distributions producing characteristically different isotopic patterns in downstream metabolites [33].

The computational core of 13C-MFA involves solving a constrained nonlinear optimization problem where fluxes are estimated by minimizing the difference between experimentally measured isotopomer distributions and those simulated by a metabolic network model [33] [21]. This approach relies on detailed knowledge of both reaction stoichiometries and atom transition mappings for each biochemical reaction in the network [33]. The development of the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework has dramatically improved the computational efficiency of 13C-MFA by decomposing large metabolic networks into smaller subnetworks that can be simulated without compromising mathematical rigor [21].

Isotopically Non-Stationary Metabolic Flux Analysis (INST-MFA)

INST-MFA relaxes one of the key assumptions of traditional 13C-MFA by performing flux analysis during the transient labeling period before isotopic steady state is reached [37] [34]. This method still assumes metabolic steady state (constant fluxes) but explicitly models the time-dependent incorporation of labeled atoms into metabolic pools [33] [34]. By capturing the dynamics of isotope propagation through metabolic networks, INST-MFA significantly shortens experimental duration and can provide enhanced flux resolution for certain network configurations [35] [34].

The mathematical foundation of INST-MFA involves solving systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe how isotopomer abundances change over time in response to the underlying metabolic fluxes [37] [33]. This approach generates substantially larger computational problems compared to 13C-MFA, as labeling patterns must be simulated at multiple time points rather than just at steady state [33]. However, the information content per experiment is often higher, potentially leading to improved flux identifiability and precision [34] [38].

Table 1: Core Theoretical Principles and Assumptions

| Characteristic | 13C-MFA | INST-MFA |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic State | Assumes metabolic steady state | Assumes metabolic steady state |

| Isotopic State | Requires isotopic steady state | Analyzes transient isotopic labeling |

| Experimental Duration | Longer (hours to days) | Shorter (minutes to hours) |

| Computational Framework | Algebraic equations | Ordinary differential equations |

| Information Content | Single time point snapshot | Multiple time point dynamics |

| Key Advantage | Established, robust methodology | Enhanced flux resolution for certain systems |

Comparative Analysis: Technical Requirements and Methodological Considerations

Experimental Design and Workflow

The experimental workflow for both 13C-MFA and INST-MFA begins with careful planning of tracer experiments, including selection of appropriate isotopic tracers, determination of optimal labeling time points, and design of sampling protocols [39]. For 13C-MFA, the fundamental requirement is that the system must reach isotopic steady state, which necessitates longer incubation times with labeled substrates—typically until metabolite labeling patterns stabilize [21]. This often means experimental durations must span multiple cell generations, which can be problematic for slow-growing cells or when investigating rapid metabolic responses to perturbations [34].

In contrast, INST-MFA experiments are characterized by high-frequency sampling during the initial period after introducing the labeled substrate, capturing the temporal evolution of isotopic labeling before the system reaches steady state [34]. This approach demands rapid sampling and quenching techniques to preserve metabolic activity at precise time points, sophisticated analytical methods for measuring time-dependent isotopomer distributions, and advanced computational resources for solving the resulting ODE systems [37] [34]. The experimental duration is significantly shorter, making INST-MFA particularly valuable for studying systems where maintaining prolonged metabolic steady state is challenging or when investigating rapid metabolic transitions [35] [38].

Data Requirements and Analytical Techniques

Both 13C-MFA and INST-MFA require precise measurements of extracellular uptake and secretion rates to constrain the possible flux solutions [21]. For 13C-MFA, the primary data consist of isotopomer distributions measured at a single time point after isotopic steady state has been reached [33]. For INST-MFA, the same type of isotopic labeling data must be collected, but at multiple time points throughout the transient labeling period [37] [34].

Mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy represent the two primary analytical platforms for measuring isotopic labeling in both approaches [1] [39]. MS is more sensitive and widely used, typically measuring mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) that represent the relative abundances of metabolites with different numbers of labeled atoms [1]. NMR provides less sensitivity but can determine the exact positions of labeled atoms within molecules, offering additional structural information about labeling patterns [39]. Recent advances in hyperpolarized NMR have enabled real-time monitoring of metabolic fluxes in living systems, potentially bridging the gap between traditional NMR and the temporal resolution requirements of INST-MFA [39].

Table 2: Technical and Analytical Requirements

| Parameter | 13C-MFA | INST-MFA |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Frequency | Single time point at isotopic steady state | Multiple time points during transient period |

| Analytical Sensitivity | Moderate | High (measures low-abundance transient species) |