Metabolic Pathway Reconstruction in Non-Model Organisms: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Clinical Application

The reconstruction of metabolic pathways in non-model organisms is a cornerstone of modern synthetic biology, enabling the development of novel microbial cell factories for drug discovery and biomanufacturing.

Metabolic Pathway Reconstruction in Non-Model Organisms: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Clinical Application

Abstract

The reconstruction of metabolic pathways in non-model organisms is a cornerstone of modern synthetic biology, enabling the development of novel microbial cell factories for drug discovery and biomanufacturing. This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles, computational and experimental methodologies, and advanced optimization techniques required to overcome the challenges associated with these non-canonical systems. We explore the unique metabolic capabilities of non-model organisms like Zymomonas mobilis and Streptococcus pneumoniae, detail the use of tools such as CRISPR, genome-scale models, and databases like KEGG and BioCyc, and present rigorous validation frameworks. By integrating insights from comparative analyses of reconstruction tools and emerging machine learning approaches, this resource aims to equip scientists with the strategies needed to harness the biotechnological potential of non-model organisms for biomedical and clinical breakthroughs.

Unlocking Potential: Why Non-Model Organisms Are Prime Targets for Metabolic Reconstruction

Defining Non-Model Organisms and Their Industrial Merits

In the landscape of biological research and industrial biotechnology, non-model organisms are emerging as pivotal players. Unlike traditional model organisms such as Escherichia coli or Saccharomyces cerevisiae, non-model organisms are species that lack a comprehensive suite of established genetic tools, databases, and standardized protocols for research [1]. The study of these organisms is driven by the recognition that the vast majority of biological diversity and many industrially valuable traits reside outside the narrow spectrum of traditional model systems [2] [1].

The shift towards investigating non-model organisms is fundamentally altering industrial microbiology. These organisms often possess unique physiological traits—such as exceptional stress tolerance, the ability to consume unconventional feedstocks, or the capacity to synthesize novel compounds—that are absent in established model systems [3] [4]. This document, framed within a thesis on metabolic pathway reconstruction, outlines the defining characteristics of non-model organisms, details their industrial advantages, and provides practical protocols for their study.

Defining Non-Model Organisms

Core Concept and Terminology

The term "model organism" has evolved to signify not only an organism that is inherently convenient for studying specific biological questions but also one for which a wealth of tools and resources exists, such as annotated genomes, mutant libraries, and standardized transformation protocols [1]. Consequently, a non-model organism is defined by a relative lack of these research infrastructures. These are often termed "non-model model organisms" (NMMOs) when they are chosen for their exceptional suitability to address a particular biological problem, despite the initial absence of genetic tools [1].

Key Differentiating Features

The primary distinctions between model and non-model organisms are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Differentiating Features of Model vs. Non-Model Organisms

| Feature | Model Organisms | Non-Model Organisms |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Toolkits | Extensive, standardized, and readily available (e.g., CRISPR, libraries of mutants). | Sparse, often need to be developed de novo or adapted from other species. |

| Genomic Resources | High-quality annotated genomes and comprehensive databases (e.g., Ecocyc for E. coli). | Genome sequences may be unavailable, preliminary, or poorly annotated. |

| Physiological Understanding | Well-characterized metabolism and genetics. | Metabolic pathways and genetic regulation are often poorly understood. |

| Research Community | Large, established community facilitating resource sharing. | Often studied by smaller, specialized groups. |

| Inherent Biological Traits | Chosen for convenience and rapid life cycles. | Chosen for unique, extreme, or industrially relevant phenotypes. |

A significant challenge in engineering non-model organisms is recalcitrance, or a natural resistance to genetic manipulation and tissue culture [2] [5]. This can be due to robust defense systems that destroy foreign DNA, complex polyploid genomes, or an inability to regenerate whole plants from single cells in the case of non-model plant species [2] [4].

Industrial Merits of Non-Model Organisms

Non-model organisms are treasure troves of unique biochemistry and robust physiology, making them exceptionally valuable for industrial applications. Their merits span multiple sectors, from the production of sustainable materials to environmental bioremediation.

Unique Physiological and Metabolic Traits

These organisms often exhibit extraordinary capabilities refined by evolution to thrive in niche or extreme environments.

- Robustness: Many non-model industrial microorganisms exhibit high tolerance to environmental stressors such as extreme pH, high temperature, and toxic inhibitors, which are common challenges in industrial fermentation processes [3] [4]. For instance, the non-model yeast Issatchenkia orientalis can grow at pH as low as 2.0, making it an excellent host for producing organic acids like succinic acid without the need for constant pH neutralization [6].

- Unique Metabolic Pathways: They often possess specialized metabolic pathways not found in model systems. The bacterium Zymomonas mobilis utilizes the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway anaerobically, yielding a high flux towards ethanol with fewer by-products compared to traditional yeast fermentation [3] [4].

- Substrate Utilization: Some non-model organisms can efficiently consume low-cost, non-food feedstocks like lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., agricultural residues), glycerol, and waste gases, enabling more sustainable and cost-effective bioprocesses [3].

Applications in Industrial Biotechnology

The unique traits of non-model organisms are being harnessed across various industries, as detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Industrial Applications of Non-Model Organisms

| Application Area | Example Organism(s) | Industrial Merit and Product |

|---|---|---|

| Biofuels & Chemicals | Zymomonas mobilis (bacterium), Oleaginous yeasts | High-yield production of bioethanol and biodiesel from mixed agrowaste hydrolysates [7] [3]. |

| Biomaterials | Corynebacterium glutamicum, Bacillus megaterium | Production of bioplastics such as polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) and amino acids for biopolymers [7]. |

| Environmental Remediation | Pseudomonas putida, Stenotrophomonas sp. | Degradation of pollutants including plastics, pesticides, and oil hydrocarbons; wastewater treatment [7] [2]. |

| Pharmaceuticals & High-Value Compounds | Streptomyces sp., Nannochloropsis | Production of antibiotics (e.g., Adriamycin), immunosuppressants (e.g., Cyclosporin A), and novel molecules discovered from unique metabolic pathways [7] [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Engineering Non-Model Organisms

Overcoming the recalcitrance of non-model organisms requires a systematic approach, from genomic characterization to the development of custom genetic tools. The following workflow and protocols outline this process.

Protocol 1: Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstruction

Objective: To build a computational model that predicts an organism's metabolic capabilities from its genome sequence, guiding metabolic engineering strategies.

Materials:

- Genomic DNA: High-quality, purified DNA from the target non-model organism.

- Software Tools: gapseq [8], CarveMe, or ModelSEED for automated reconstruction; the COBRA Toolbox for model simulation and analysis [9].

- Biochemical Databases: KEGG, BRENDA, UniProt, and TCDB for reaction and enzyme information [9].

- Physiological Data: Experimentally determined data on substrate utilization, growth rates, and by-product secretion for model validation [9] [6].

Method:

- Draft Reconstruction: Use an automated tool like

gapseqwith the genomic FASTA file as input. The software will identify protein-coding sequences and map them to metabolic reactions using homology searches [8]. - Network Assembly: Compile a draft network containing all identified reactions, transport processes, and biomass precursors.

- Manual Curation and Gap-Filling: This is a critical, iterative step.

- Identify metabolic gaps—missing reactions that prevent the synthesis of essential biomass components.

- Use genomic evidence (e.g., homologies to poorly annotated genes) and physiological data (e.g., known secretion products) to propose and add missing reactions.

- Manually curate pathway gaps and correct misannotations based on literature and organism-specific knowledge [9].

- Model Validation: Test the model's predictive power by comparing simulations with experimental data.

- Simulate growth on different carbon sources and compare with phenotyping data.

- Predict gene essentiality and compare with gene knockout results, if available [6].

- Model Application: Use the validated model to predict metabolic engineering targets, such as gene knockouts (e.g., using OptKnock) or additions to overproduce a compound of interest [6].

Protocol 2: Establishing a Genetic Engineering Toolkit

Objective: To develop a functional method for introducing and stably integrating genetic modifications into a recalcitrant non-model organism.

Materials:

- Bioinformatics Pipeline: Software to identify endogenous systems (e.g., http://ZymOmics.cn for R-M, CRISPR-Cas, and T-A systems) [4].

- Cloning Strains: E. coli strains for plasmid construction (e.g., T1) and demethylation (e.g., Trans110) to bypass host restriction systems [4].

- Vector Components: Origins of replication, selectable markers (antibiotic resistance), and inducible promoters functional in the target host.

- Transformation Equipment: Electroporator or equipment for conjugation.

Method:

- Identify and Temper Defense Systems:

- Use a centralized database or custom pipeline to scan the genome for Restriction-Modification (R-M) and Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR-Cas) systems [4].

- To overcome R-M barriers, propagate plasmids in an E. coli strain that mimics the methylation pattern of the target organism or directly delete the genes encoding restriction enzymes [2] [4].

- Develop a Genome-Editing System:

- Implement a Continuous Editing Platform:

- Establish a Genome-Wide Iterative and Continuous Editing (GW-ICE) system. This integrates the identified endogenous CRISPR-Cas and repair systems with a temperature-sensitive plasmid, allowing for multiple, sequential genetic modifications without repeated transformation [4].

- Overcome Recalcitrance in Plants:

- For non-model plants, overcome tissue culture recalcitrance by heterologously expressing transcription factors like Baby Boom to induce shoot production, or use CRISPR to edit repressors of regeneration [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents for working with non-model organisms like Zymomonas mobilis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Engineering Non-Model Microorganisms

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Demethylating E. coli Strain (e.g., Trans110) | Produces plasmids with host-specific methylation patterns, protecting them from degradation by restriction enzymes. | Essential for achieving high transformation efficiency in bacteria with active R-M systems [4]. |

| Endogenous CRISPR-Cas System Components | Provides a host-adapted machinery for programmable DNA cleavage, improving editing efficiency. | Using the native Type I-F system of Z. mobilis for reliable gene knockouts [3] [4]. |

| Temperature-Sensitive Plasmid Backbone | Allows for plasmid replication at a permissive temperature and loss at a non-permissive temperature. | Facilitates marker-free editing and enables multiple rounds of modification in the GW-ICE system [4]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | Serves as a computational blueprint to predict metabolic flux and identify engineering targets. | iIsor850 model for I. orientalis was used to pinpoint gene knockouts for coupling succinate production to growth [6]. |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Donor DNA | Serves as a template for precise gene insertions or corrections during CRISPR-Cas editing. | Used alongside CRISPR to introduce heterologous pathways (e.g., 2,3-butanediol pathway in Z. mobilis) [3]. |

Non-model organisms represent the next frontier in industrial biotechnology. Their vast, untapped metabolic diversity offers sustainable solutions for producing energy, chemicals, and materials, and for addressing environmental pollution. While significant challenges in genetic recalcitrance remain, the protocols and strategies outlined here—centered on robust genomic analysis, sophisticated metabolic modeling, and the development of customized genetic toolkits—provide a clear roadmap for their domestication. Integrating these approaches will accelerate the transformation of these enigmatic organisms into efficient microbial cell factories, paving the way for a circular bioeconomy.

The reconstruction of metabolic pathways in non-model organisms represents a frontier in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. A significant barrier in this field is the presence of dominant native metabolic pathways that effectively compete for central carbon metabolites, severely limiting the flux toward engineered, non-native products. The ethanologenic bacterium Zymomonas mobilis serves as a paradigm for this challenge. This organism possesses an exceptionally efficient native metabolism for ethanol production, where carbon flow through the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway is predominantly directed toward ethanol via the pyruvate decarboxylase (PDC) and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) enzymes [3]. This innate metabolic architecture creates a formidable bottleneck for redirecting carbon toward alternative biochemicals, as the native pathway often constitutes over 97% of theoretical yield efficiency on a carbon basis [10]. Overcoming this dominance is not merely a technical hurdle but a fundamental requirement for transforming organisms with ideal industrial characteristics into versatile biorefinery chassis for a sustainable circular bioeconomy [3].

Core Challenge: Native Pathway Dominance in Zymomonas mobilis

The Entner-Doudoroff Pathway and Ethanol Production

Zymomonas mobilis utilizes the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway anaerobically, a rare characteristic that contributes to its exceptional ethanol production capabilities. The ED pathway generates only one net ATP per glucose molecule, compared to two ATP molecules produced by the more common Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway [10]. This lower energy yield results in reduced biomass formation, thereby directing a greater proportion of carbon toward ethanol production. The metabolic journey from glucose to ethanol in Z. mobilis involves several key steps: glucose is first converted to gluconate by glucose-fructose oxidoreductase, then to 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate (KDPG) by gluconate dehydratase, and finally cleaved into glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) and pyruvate by KDPG aldolase. Pyruvate is subsequently decarboxylated by PDC to acetaldehyde, which is then reduced to ethanol by ADH, regenerating NAD+ for glycolytic continuity [3] [10].

Experimental Evidence of Metabolic Recalcitrance

Attempts to engineer alternative metabolic routes in Z. mobilis have consistently encountered resistance from its native metabolic network. A particularly illustrative example is the failed attempt to implement the complete EMP pathway by expressing E. coli phosphofructokinase (Pfk I), both alone and in combination with fructose bisphosphate aldolase (Fba) and triose phosphate isomerase (Tpi) [10]. Contrary to predictions, this engineering effort did not establish a functional EMP flux but instead resulted in growth inhibition and mutations in the heterologous pfkA gene. Metabolomic analysis revealed that the homeostatic levels of glycolytic intermediates in Z. mobilis were incompatible with EMP flux, demonstrating how the native metabolomic context constrains potential engineering strategies [10].

Table 1: Failed Metabolic Engineering Attempts Against Dominant Pathways in Z. mobilis

| Engineering Strategy | Target Pathway | Experimental Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression of E. coli Pfk I | EMP glycolysis | Growth inhibition; mutation of heterologous gene; no EMP flux established | [10] |

| Co-expression of Pfk I, Fba, and Tpi | EMP glycolysis | Glycerol production as side product; reverse operation of heterologous reactions | [10] |

| PPi-dependent Pfk expression | EMP glycolysis | No significant metabolic changes; excretion of dihydroxyacetone | [10] |

| Promoter replacement of pdc | Ethanol to lactate shift | Partial redirection; incomplete elimination of ethanol pathway | [3] |

Strategic Framework: Overcoming Dominant Metabolism

Dominant-Metabolism Compromised Intermediate-Chassis (DMCI) Strategy

A novel approach termed the Dominant-Metabolism Compromised Intermediate-Chassis (DMCI) strategy has been developed specifically to address the challenge of pathway dominance [3]. Instead of directly engineering the chassis for target biochemical production, this method involves first constructing an intermediate chassis with intentionally compromised dominant metabolism. In Z. mobilis, this was achieved by introducing a low-toxicity but cofactor-imbalanced 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BDO) pathway, which effectively diverted carbon flux from the dominant ethanol production route. This intermediate chassis served as a platform for subsequent engineering, ultimately enabling the construction of a high-efficiency D-lactate producer capable of achieving remarkable titers of >140 g/L from glucose and >104 g/L from corncob residue hydrolysate with yields exceeding 0.97 g/g glucose [3].

Advanced Modeling and Pathway Design

The implementation of sophisticated genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) has proven indispensable for navigating the constraints imposed by dominant native metabolism. The development of enzyme-constrained models like eciZM547 represents a significant advancement over traditional stoichiometric models [3]. By integrating enzyme kinetic parameters and accounting for proteome limitations, these models can more accurately simulate flux distributions and identify potential bottlenecks before experimental implementation. For Z. mobilis, the eciZM547 model successfully predicted the shift from glucose-limited growth to proteome-limited growth at high substrate uptake rates and more accurately simulated carbon distribution between acetate and acetoin under aerobic conditions compared to previous models [3]. This predictive capability is crucial for designing effective strategies to overcome innate metabolic dominance.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: DMCI Strategy Implementation for Carbon Flux Redirection

Principle: Introduce a metabolic pathway with lower toxicity than the target product but sufficient carbon drain to weaken the dominant native pathway, creating an intermediate chassis for further engineering [3].

Materials:

- Z. mobilis wild-type strain (e.g., ZM4)

- Plasmid vector with 2,3-BDO pathway genes (alsS, alsD, bdhA) or similar

- CRISPR-Cas12a or endogenous Type I-F CRISPR-Cas genome editing system [3] [11]

- Anaerobic growth chamber

- ZRMG medium: 1% yeast extract, 2% glucose, 15 mM KH₂PO₄ [10]

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Inoculate Z. mobilis ZM4 in ZRMG medium and grow anaerobically at 30°C to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6-0.8).

- Editing System Delivery: Transform with plasmid encoding CRISPR-Cas system and editing template for integrating 2,3-BDO pathway genes into a neutral site.

- Intermediate Selection: Plate transformed cells on ZRMG agar with appropriate antibiotic and incubate anaerobically at 30°C for 48-72 hours.

- Intermediate Validation: Screen colonies for 2,3-BDO production using HPLC and reduced ethanol yield (expected 20-40% reduction).

- Target Pathway Integration: Introduce target product pathway (e.g., D-lactate dehydrogenase) into validated intermediate chassis using same editing system.

- Final Validation: Screen for high target product titers with minimal ethanol byproduct (expected >95% carbon redirection).

Technical Notes: The 2,3-BDO pathway serves as an effective intermediate due to its NADH/NAD+ cofactor imbalance, which naturally limits its full dominance while sufficiently draining carbon from ethanol production.

Protocol 2: Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Model Simulation for Pathway Design

Principle: Utilize enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) to predict flux distributions and identify proteome limitations before experimental implementation [3] [12].

Materials:

- eciZM547 model or similar enzyme-constrained metabolic model

- COBRA Toolbox v3.0 or similar metabolic modeling software

- MATLAB R2020a or Python 3.8 with appropriate packages

- AutoPACMEN for kcat prediction [3]

Procedure:

- Model Preparation: Load eciZM547 model into modeling environment and set constraints (e.g., glucose uptake = 10 mmol/gDW/h).

- Enzyme Constraints: Assign enzyme usage constraints based on proteomic data or kcat values from AutoPACMEN.

- Pathway Addition: Introduce heterologous reactions for target product with associated enzyme demands.

- Flux Simulation: Perform flux balance analysis (FBA) or parsimonious FBA to predict maximum theoretical yield.

- Proteome Analysis: Identify potential enzyme saturation points and proteome allocation bottlenecks.

- Iterative Design: Modify pathway design or enzyme expression levels in silico to optimize flux.

- Experimental Validation: Compare predictions with experimental results for model refinement.

Technical Notes: The enzyme-constrained model will show proteome-limited growth at high substrate uptake rates (>71 mmol/gDW/h for glucose in Z. mobilis), which is not predicted by traditional GEMs.

Pathway Visualization and Metabolic Engineering Workflows

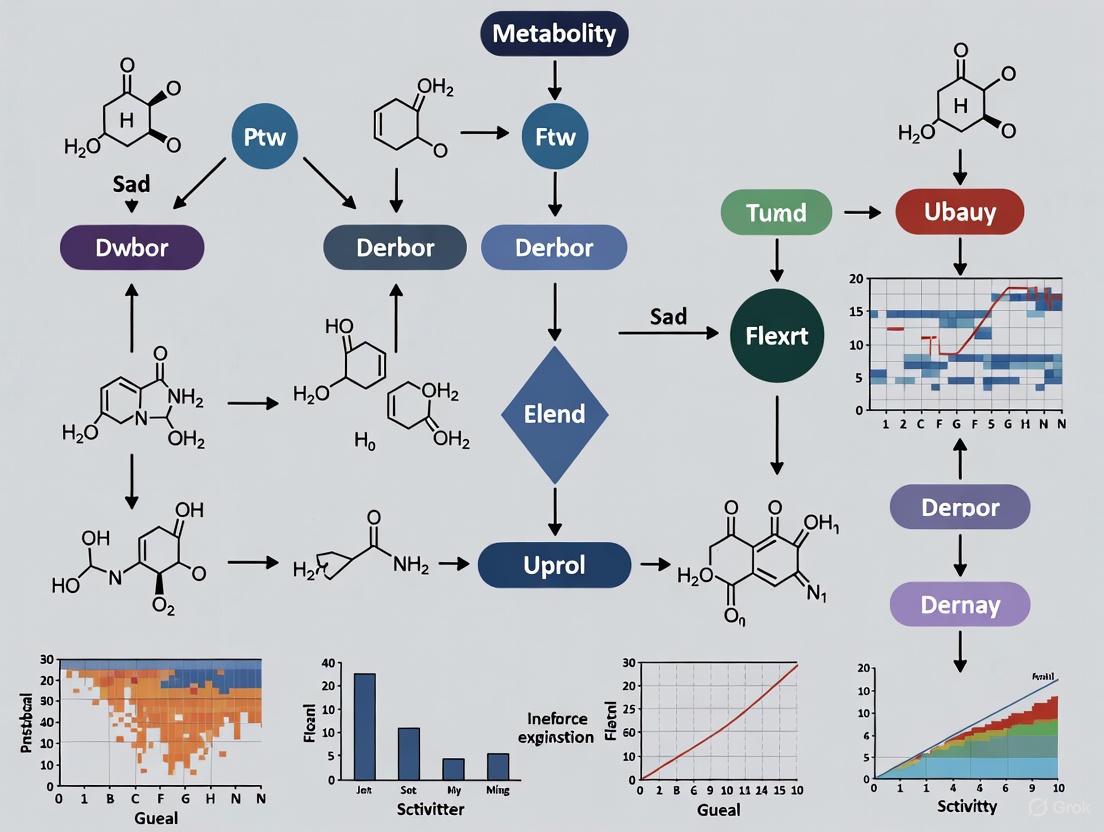

Central Carbon Metabolism and Engineering Targets in Z. mobilis

Diagram 1: Central carbon metabolism and engineering targets in Z. mobilis. The dominant native ethanol pathway (red) competes with engineered pathways (green) for pyruvate. Key enzymes: ZWF (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase), GFOR (glucose-fructose oxidoreductase), GAD (gluconate dehydratase), EDA (KDPG aldolase), PDC (pyruvate decarboxylase), ADH (alcohol dehydrogenase), LDH (lactate dehydrogenase), ALS (acetolactate synthase), ALDC (acetolactate decarboxylase), BDH (butanediol dehydrogenase).

DMCI Strategy Workflow for Overcoming Dominant Metabolism

Diagram 2: DMCI strategy workflow. The approach involves creating an intermediate chassis with compromised dominant metabolism before introducing the target product pathway. ecGEM: enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic model; TEA: techno-economic analysis; LCA: life cycle assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Engineering Non-Model Organisms

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas12a, Endogenous Type I-F CRISPR-Cas, MMEJ repair | Precise genome modification; essential for pathway integration and gene knockout | [3] [11] |

| Metabolic Modeling Software | COBRA Toolbox, AutoPACMEN (kcat prediction), MEMOTE (model evaluation) | Pathway simulation; prediction of flux distributions and enzyme limitations | [3] [12] |

| Analytical Chemistry | HPLC (product quantification), GC-MS (metabolite profiling), RNA-Seq (transcriptomics) | Validation of metabolic changes; systems biology analysis | [3] [13] [14] |

| Specialized Growth Media | ZRMG (standard growth), Modified ZYMM (N2-fixing conditions), CRH (lignocellulosic hydrolysate) | Physiological studies; industrial-relevant condition simulation | [10] [15] |

| Pathway Enzymes | 2,3-BDO pathway (alsS, alsD), D-LDH (D-lactate dehydrogenase), XI (xylose isomerase) | Metabolic pathway reconstruction; substrate utilization expansion | [3] [16] [14] |

The challenge of dominant native metabolism in non-model organisms like Zymomonas mobilis represents a significant but surmountable barrier in metabolic pathway reconstruction. The development of sophisticated strategies such as the DMCI approach, coupled with advanced modeling techniques and precise genome editing tools, has demonstrated that even exceptionally efficient native pathways can be redirected toward alternative products. The successful production of D-lactate at titers exceeding 140 g/L with yields >0.97 g/g glucose from Z. mobilis provides compelling evidence that these strategies can achieve commercial viability, as further supported by techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment [3]. As the field progresses, the integration of multi-omics data, machine learning-assisted pathway design, and dynamic regulation systems will further enhance our ability to engineer non-model organisms with complex metabolic networks, ultimately expanding the repertoire of microbial chassis available for sustainable biochemical production.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a significant global health concern, being a leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia, meningitis, and septicemia [17] [18]. This Gram-positive pathogen poses a substantial threat to young children, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals, with an estimated one million child deaths annually attributed to pneumococcal disease [17]. The challenge in managing S. pneumoniae infections is compounded by the escalating prevalence of antimicrobial resistance, with over 40% of strains exhibiting resistance to penicillin and frequently demonstrating co-resistance to other antibiotics such as macrolides and tetracyclines [17] [19]. The World Health Organization has recognized this threat by adding S. pneumoniae to its updated Bacterial Priority Pathogens List as a medium-priority pathogen [17].

In the context of metabolic pathway reconstruction for non-model organisms, subtractive genomics represents a powerful computational approach for identifying novel therapeutic targets. This methodology leverages the growing availability of genomic data to systematically identify essential pathogen-specific proteins that are absent in the host, thereby facilitating the development of targeted therapies with minimal side effects [17] [20]. By focusing on non-host homologous genes involved in distinct metabolic pathways crucial for pathogen survival, this approach enables researchers to disrupt pathogen function while preserving host biology [17]. This case study details the application of subtractive genomics for identifying potential drug targets in S. pneumoniae, providing a comprehensive protocol for researchers engaged in metabolic pathway reconstruction and drug discovery.

Background and Significance

The complex etiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection poses significant challenges in elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying its pathogenesis [18]. With over 100 recognized serotypes, this pathogen exhibits remarkable genetic variability, with different serotypes demonstrating varying degrees of invasiveness and pathogenicity [17] [21]. Current vaccine strategies, including the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23), target specific capsular polysaccharide serotypes but face limitations due to emerging non-vaccine serotypes and the phenomenon of capsular switching [17] [19].

The genomic plasticity of S. pneumoniae enables rapid adaptation through competence-dependent horizontal gene transfer, facilitating the dissemination of resistance traits and pathogenic factors [17]. Recent genomic surveillance studies in Indian adult populations have revealed a high prevalence of multidrug resistance (observed in 70% of isolates) and the continuous emergence of novel sequence types through recombination events [19]. This dynamic evolutionary landscape underscores the critical need for novel therapeutic strategies that target essential metabolic pathways conserved across diverse strains.

Metabolomic analyses of S. pneumoniae infections have identified significant alterations in host metabolic profiles, with activation of pathways including galactose metabolism, the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) signaling pathway, the citrate cycle, the pentose phosphate pathway, and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis [18]. These pathway perturbations represent potential vulnerabilities that can be exploited through targeted therapeutic interventions.

Methodology: Subtractive Genomics Workflow

The subtractive genomics approach follows a systematic pipeline to filter and identify potential drug targets from the complete proteome of S. pneumoniae. The stepwise methodology is outlined below and visualized in Figure 1.

Proteome Retrieval and Initial Processing

The complete genome assembly of S. pneumoniae (GCF002076835.1ASM207683v1protein.fasta) was retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database [17] [22]. The human proteome (GCF000001405.40GRCh38.p14protein.fasta) was similarly obtained for comparative analysis.

Redundancy elimination was performed using CD-HIT (version 4.8.1) with a 90% sequence identity threshold to cluster and remove duplicate protein sequences, ensuring only unique sequences were retained for subsequent analysis [17].

Non-Homologous Protein Identification

Protein sequences in S. pneumoniae lacking homologs in human proteins were identified using a BLASTp search against the Homo sapiens genome with an E-value cut-off of 10−5 [17] [20]. Sequences with significant similarity to human proteins were excluded to minimize potential cross-reactivity and host toxicity in subsequent drug development stages.

Table 1: Summary of Proteome Filtering Steps in Subtractive Genomics

| Filtering Stage | Proteins Remaining | Reduction Percentage | Tools/Databases Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial S. pneumoniae Proteome | 2,027 | - | NCBI |

| After Redundancy Elimination | ~2,000 | 1.3% | CD-HIT (90% identity) |

| Non-Homologous to Human | ~2,000 | 0% | BLASTp (E-value: 10⁻⁵) |

| Essential Genes | 48 | 97.6% | Database of Essential Genes (DEG) |

| After Gut Microflora Consideration | 21 | 56.3% | BLASTp against gut microbiome |

Essential Gene Identification

Essential genes for S. pneumoniae survival were identified using the Database of Essential Genes (DEG), which catalogs genes indispensable for bacterial survival under laboratory conditions [17] [22]. To further refine target selection and minimize disruption to beneficial microbiota, these essential genes were compared against the human gut microbiome proteome using BLASTp with the same E-value threshold, eliminating those with significant matches [17].

Metabolic Pathway and Subcellular Localization Analysis

The resulting set of potential targets was subjected to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis to identify metabolic pathways critical for bacterial survival [18] [20]. Additionally, subcellular localization predictions were performed to prioritize targets with accessible subcellular locations, particularly focusing on cytoplasmic membrane proteins that may be more readily targetable [23].

Structural Modeling and Virtual Screening

For targets lacking crystal structures, homology modeling was employed to generate three-dimensional structural models [17]. These models were then subjected to structure-based virtual screening of FDA-approved compound libraries to identify potential repurposing candidates, using molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate binding stability and interactions [17] [22].

Figure 1. Workflow for subtractive genomics analysis of S. pneumoniae. The pipeline systematically filters the bacterial proteome to identify potential drug targets that are essential for pathogen survival but absent in the host and beneficial microbiota.

Results and Key Findings

Identification of Potential Drug Targets

Application of the subtractive genomics pipeline to S. pneumoniae yielded promising results for target identification. From an initial proteome of 2,027 proteins, approximately 2,000 were identified as non-homologous to human proteins [17]. Essential gene analysis identified 48 genes crucial for bacterial survival, which was further refined to 21 potential targets after considering preservation of human gut microflora [17] [22].

Key hub genes identified through protein-protein interaction analysis included gpi (glucose-6-phosphate isomerase), fba (fructose-bisphosphate aldolase), rpoD (RNA polymerase sigma factor), and trpS (tryptophan--tRNA ligase) [17]. These targets were associated with 20 distinct metabolic pathways essential for bacterial survival, with particular enrichment in carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid biosynthesis pathways.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Metabolomic studies of S. pneumoniae infections have revealed significant alterations in host metabolic pathways, providing additional context for target prioritization [18]. Comparative analysis of metabolic profiles between infected individuals and normal controls identified 418 metabolites that significantly contributed to group differentiation [18].

Table 2: Key Metabolic Pathways Altered in S. pneumoniae Infection

| Metabolic Pathway | Role in Pathogenesis | Potential for Therapeutic Targeting |

|---|---|---|

| Galactose Metabolism | Energy production and cell wall biosynthesis | High - Essential for bacterial growth |

| HIF-1 Signaling Pathway | Host immune response to infection | Medium - Host-pathogen interaction |

| Citrate Cycle (TCA Cycle) | Central energy metabolism | High - Essential for bacterial survival |

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway | Nucleotide synthesis and antioxidant defense | High - Essential for replication |

| Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | Carbohydrate metabolism and energy production | High - Primary metabolic pathway |

The identified metabolites were categorized into various groups, including amino acids, fatty acids, and phosphatidylcholine, with these metabolic alterations being implicated in the immune response to infection [18]. This comprehensive analysis of the metabolic network provides a foundational framework for targeting pathogen-specific metabolic vulnerabilities.

Drug Repurposing Candidates

Virtual screening of 2,509 FDA-approved compounds against the prioritized targets identified Bromfenac as a leading repurposing candidate [17] [22]. This nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug exhibited a binding energy of -26.335 ± 29.105 kJ/mol against selected targets in molecular docking studies [22]. Bromfenac, particularly when conjugated with AuAgCu2O nanoparticles, has demonstrated antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties against Staphylococcus aureus, suggesting potential efficacy against S. pneumoniae pending experimental validation [17].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Subtractive Genomics Analysis

Objective: To identify essential, non-host homologous proteins in S. pneumoniae as potential drug targets.

Materials:

- Complete proteome of S. pneumoniae (retrieve from NCBI)

- Human proteome (retrieve from NCBI)

- CD-HIT software (version 4.8.1)

- BLAST+ suite (for BLASTp analysis)

- Database of Essential Genes (DEG)

Procedure:

- Data Retrieval: Download the complete proteome of S. pneumoniae (GCF002076835.1ASM207683v1protein.fasta) and human proteome (GCF000001405.40GRCh38.p14protein.fasta) from NCBI.

- Redundancy Elimination: Process the S. pneumoniae proteome using CD-HIT with a 90% identity threshold to remove duplicate sequences.

- Non-Homologous Protein Identification:

- Perform BLASTp search of S. pneumoniae proteins against the human proteome.

- Use an E-value cut-off of 10−5 to exclude sequences with significant homology.

- Retain non-homologous sequences for further analysis.

- Essential Gene Identification:

- Compare non-homologous proteins against the Database of Essential Genes (DEG).

- Identify proteins essential for bacterial survival.

- Gut Microflora Consideration:

- Perform additional BLASTp analysis of essential genes against human gut microbiome proteome.

- Eliminate genes with significant matches to preserve beneficial microbiota.

- Pathway Analysis:

- Submit final candidate targets to KEGG pathway enrichment analysis.

- Identify associated metabolic pathways for target prioritization.

Protocol 2: Molecular Docking and Virtual Screening

Objective: To identify potential repurposing candidates against prioritized targets.

Materials:

- Homology models of target proteins

- Library of FDA-approved compounds (e.g., DrugBank)

- Molecular docking software (AutoDock Vina, GROMACS)

- Hardware capable of parallel computing

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation:

- For targets lacking crystal structures, generate homology models using appropriate templates.

- Perform energy minimization and geometry optimization of protein structures.

- Prepare compound libraries in appropriate formats for docking.

- Molecular Docking:

- Define binding sites based on functional annotations or predicted active sites.

- Perform high-throughput virtual screening using AutoDock Vina.

- Record binding energies and poses for top candidates.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations:

- Subject top complexes to molecular dynamics simulations using GROMACS.

- Assess binding stability and interaction patterns over simulation time.

- Calculate binding free energies using MM-PBSA/GBSA methods.

- ADMET Prediction:

- Predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity profiles.

- Prioritize candidates with favorable pharmacokinetic properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Category | Specific Application | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD-HIT | Bioinformatics Tool | Sequence clustering and redundancy removal | https://github.com/weizhongli/cdhit |

| BLAST+ | Bioinformatics Tool | Sequence homology searches | https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/executables/blast+/ |

| Database of Essential Genes (DEG) | Database | Essential gene identification | http://origin.tubic.org/deg/public/index.php |

| KEGG Pathway | Database | Metabolic pathway analysis and visualization | https://www.genome.jp/kegg/ |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular Docking | Structure-based virtual screening | http://vina.scripps.edu/ |

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics | Simulation of biomolecular interactions | https://www.gromacs.org/ |

| ModelSEED | Metabolic Modeling | Reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models | https://modelseed.org/ |

Metabolic Pathway Reconstruction and Integration

The reconstruction of metabolic networks in non-model organisms like S. pneumoniae provides critical insights for drug target identification. Genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) integrate genes, metabolic reactions, and metabolites to simulate metabolic flux distributions under specific conditions [24]. For Streptococci, these models have been valuable in linking metabolic regulation and pathogenicity [24].

The iNX525 model of Streptococcus suis, a related species, exemplifies this approach, containing 525 genes, 708 metabolites, and 818 reactions [24]. Similar principles can be applied to S. pneumoniae to systematically analyze metabolic genes associated with virulence factor formation and identify targets affecting both virulence and cell growth [24].

Figure 2. Key metabolic pathways and potential drug targets in S. pneumoniae. Essential enzymes identified through subtractive genomics (fba, gpi, trpS) are highlighted in red, showing their positions in central metabolism and connections to virulence factor production.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The application of subtractive genomics to S. pneumoniae has demonstrated considerable promise in identifying novel therapeutic targets. By systematically filtering the pathogen's proteome, this approach addresses the critical challenge of antibiotic resistance by focusing on essential pathogen-specific pathways [17] [20]. The identification of 21 high-priority targets, including key hub genes such as gpi, fba, rpoD, and trpS, provides a foundation for future drug development efforts [17].

The integration of multi-omics data represents the future of target identification in pathogenic bacteria. Combining genomic, metabolomic, and transcriptomic datasets can provide a more comprehensive understanding of pathogen vulnerability [18] [20]. As demonstrated in metabolomic studies of S. pneumoniae infections, the activation of specific metabolic pathways in response to infection provides additional layers of information for target prioritization [18]. Furthermore, the successful identification of Bromfenac as a repurposing candidate highlights the potential for accelerating therapeutic development through computational approaches [17] [22].

Future directions in this field should emphasize the experimental validation of computationally identified targets through in vitro and in vivo studies [20]. Additionally, the incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches will enhance the predictive power of these analyses, enabling more accurate target prioritization and binding affinity predictions [20]. As genomic sequencing technologies continue to advance and become more accessible, subtractive genomics approaches will play an increasingly important role in addressing the global challenge of antimicrobial resistance.

Metabolic pathway reconstruction for non-model organisms is a fundamental challenge in systems biology and metabolic engineering. Without the extensive biochemical characterization available for model organisms, researchers must rely heavily on computational predictions derived from curated reference databases. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), BioCyc, and MetaCyc represent three essential knowledge bases that enable scientists to infer metabolic capabilities from genomic sequences. These databases employ different curation philosophies and provide complementary tools for pathway prediction, analysis, and visualization. Within the context of non-model organism research, understanding the relative strengths and applications of each resource is crucial for accurate metabolic reconstruction, which in turn drives discoveries in synthetic biology, drug target identification, and understanding of microbial ecology. This article provides a detailed comparison of these databases and protocols for their effective application in non-model organism studies.

Database Comparison: Scope, Content, and Curational Approach

Quantitative Database Comparison

Table 1: Comparative analysis of KEGG, MetaCyc, and BioCyc database content and scope.

| Feature | KEGG | MetaCyc | BioCyc Collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Integrated knowledge of biological systems, diseases, and drugs [25] | Reference database of experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways and enzymes [26] | Collection of >20,000 organism-specific Pathway/Genome Databases (PGDBs) [27] |

| Pathway Content | Manually drawn pathway maps (e.g., ko, ec) and modules [28] | 3,264 metabolic pathways (as of 2025) [29] | Varies by organism; includes computationally inferred and curated pathways [27] |

| Reaction Content | 8,692 reactions (2012 data) [30] | 20,039 reactions (as of 2025) [29] | Propagated from MetaCyc and organism-specific curation [31] |

| Compound Content | 16,586 compounds (2012 data) [30] | 20,490 compounds (as of 2025) [29] | Propagated from MetaCyc and organism-specific curation [31] |

| Curation Philosophy | Manual pathway maps with automated genome annotation | Heavy manual curation of individual pathways and reactions [30] | Tiered system (Tier 1: heavily curated, Tier 3: fully computational) [31] |

| Taxonomic Scope | Universal | 3,542 organisms (pathway sources) [29] | 20,080 organisms (as of 2025) [32] |

| Key Strengths | Broad biological scope including diseases and drugs; conserved orthologs (KOs) [28] [25] | High-quality curated metabolic data; supports metabolic engineering [30] [26] | Scalable platform for organism-specific metabolic reconstruction [27] [31] |

Conceptual and Curational Differences

The databases employ fundamentally different conceptualizations of metabolic pathways. A systematic comparison found that KEGG pathways contain 3.3 times as many reactions on average as MetaCyc pathways, reflecting their more inclusive, "map"-like nature [30]. KEGG organizes its content into manually drawn "map" pathways and higher-level "module" pathways, whereas MetaCyc distinguishes between base pathways and super-pathways that combine multiple base pathways [30].

The curation scope also differs significantly. MetaCyc contains a broader set of database attributes than KEGG, including regulatory information, identification of spontaneous reactions, and the expected taxonomic range of metabolic pathways [30]. MetaCyc also includes more balanced reaction equations, facilitating metabolic modeling approaches such as flux-balance analysis [30]. Each database also contains unique pathway content: MetaCyc includes more pathways from plants, fungi, metazoa, and actinobacteria, while KEGG contains more pathways for xenobiotic degradation, glycan metabolism, and metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides [30].

Experimental Protocols for Metabolic Pathway Reconstruction

Protocol 1:De NovoPathway Prediction with PathoLogic

Purpose: To generate an organism-specific Pathway/Genome Database (PGDB) from genomic annotation using the PathoLogic component of Pathway Tools.

Applications: Creation of draft metabolic networks for non-model organisms with sequenced genomes, enabling subsequent analysis and curation [26] [31].

Table 2: Key research reagents and computational tools for pathway reconstruction.

| Research Reagent / Software | Function in Protocol | Access / Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Tools Software | Primary software suite for creating, curating, and analyzing PGDBs [33] [34] | Free academic license; runs on Mac, Windows, Linux [33] |

| Annotated Genome File | Input data containing predicted genes and functional assignments (e.g., EC numbers) [31] | Typically in GenBank format or similar |

| MetaCyc Reference DB | Reference metabolic pathway database used for inference [26] | Included with Pathway Tools [33] |

| BioCyc Data Files | Optional comparative data for related organisms [33] | Requires subscription (except EcoCyc) [33] |

Methodology:

Input Preparation: Obtain the completely sequenced and annotated genome of the target non-model organism in a supported format (e.g., GenBank format). Ensure gene annotations include Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers where possible, as these are primary inputs for pathway prediction [31].

PathoLogic Execution:

- Create a new PGDB using the "Create New PGDB" wizard in Pathway Tools.

- Select the appropriate annotated genome file as input.

- Specify MetaCyc as the reference pathway database for pathway inference.

- PathoLogic will automatically predict the organism's metabolic network by:

- Identifying enzymes in the genome based on EC numbers or gene names.

- Matching these enzymes to reactions in the MetaCyc database.

- Applying an algorithm to assemble these reactions into metabolic pathways that are present in the organism [31].

Output and Validation: The output is a new PGDB containing:

- The imported genome annotation.

- The predicted metabolic network, including pathways, reactions, and compounds.

- Computationally predicted operons (for prokaryotes) [31].

- Manually review the "Pathway Holes" report (reactions that are part of a predicted pathway but lack an associated gene) to identify areas requiring further curation or experimental validation [34].

Figure 1: Workflow for *de novo pathway prediction with PathoLogic.*

Protocol 2: Metabolomics Data Analysis and Interpretation

Purpose: To contextualize metabolomics datasets within the predicted metabolic network of a non-model organism to identify actively used pathways and potential bottlenecks.

Applications: Interpretation of high-throughput metabolomics data; identification of pathway activation under different growth conditions; target identification for metabolic engineering [26].

Methodology:

Data Preparation: Prepare metabolomics data as a tab-delimited file where rows represent metabolites and columns represent experimental conditions or time points. Metabolites should be identified using standard identifiers (e.g., MetaCyc compound IDs, KEGG compound IDs, or standard chemical names) to facilitate mapping.

Data Import and Mapping:

- Within the organism-specific PGDB (created in Protocol 1), use the "Upload Omics Data" functionality in Pathway Tools.

- Load the prepared metabolomics file. The software will attempt to map metabolite identifiers to those in the database.

- Manually resolve any unmapped metabolites to ensure comprehensive data coverage.

Visualization and Analysis:

- Use the Cellular Overview tool (a zoomable, whole-cell metabolic map) to visualize the data. The tool will overlay metabolite abundance measurements directly onto the metabolic network [27].

- Utilize the Omics Dashboard to view data aggregated by metabolic subsystem, enabling high-level identification of affected pathways [34].

- For multi-omics integration, use the Multi-Omics Cellular Overview to simultaneously visualize transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data painted onto the same metabolic map using different visual attributes (color, size) for nodes and edges [34].

Figure 2: Workflow for metabolomics data analysis using a PGDB.

Protocol 3: Comparative Analysis and Pathway Conservation

Purpose: To identify conserved and unique metabolic capabilities across multiple non-model organisms by comparing their PGDBs.

Applications: Pan-genome metabolic analysis; identification of taxonomic markers; guiding experimental design by highlighting core and accessory metabolism.

Methodology:

Dataset Establishment: Generate PGDBs for multiple related non-model organisms using Protocol 1. Alternatively, select existing PGDBs from the BioCyc collection for organisms of interest [27].

Comparative Analysis Execution:

- Use the Comparative Analysis tools within Pathway Tools. This can be accessed via the web interface or desktop application.

- Select the set of organisms for comparison. The software will generate tables and summaries of shared and unique genes, reactions, and pathways.

- Utilize the Comparative Genome Dashboard to visually compare cellular subsystems across multiple organisms, drilling down to specific metabolic differences [34].

Orthology-Based Cross-Referencing with KEGG:

- Annotate the genomes of your non-model organisms with KEGG Orthology (KO) identifiers using tools like BlastKOALA or GhostKOALA [25].

- Map KO assignments to the KEGG Pathway maps to obtain an alternative view of the metabolic network, complementing the BioCyc/MetaCyc-based reconstruction.

- Compare the KEGG-module-completeness scores for specific pathways of interest across your organism set to rapidly assess functional potential.

Table 3: Key databases, software, and tools for metabolic pathway research.

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Tools [33] [34] | Software Suite | Create, edit, analyze, and visualize PGDBs; predict pathways; omics data analysis. | Free academic license |

| KEGG Mapper [25] | Web Tool Suite | Map user data (genes, compounds) onto KEGG pathway maps and BRITE hierarchies. | Subscription/paid |

| MetaCyc [29] [26] | Reference Database | Curated reference for pathway prediction and enzyme information; educational resource. | Free |

| BioCyc Collection [27] | Database Collection | Access thousands of pre-computed PGDBs for comparative analysis. | Subscription (partial free) |

| KEGG Orthology (KO) [25] | Classification System | Standardized annotation of gene functions for pathway mapping across species. | Subscription/paid |

| SmartTables [27] [34] | Analysis Tool | Create, share, and analyze sets of genes, compounds, etc.; perform enrichment analysis. | Via BioCyc/Pathway Tools |

| BlastKOALA [25] | Annotation Service | Automated KEGG Orthology assignment and pathway mapping for nucleotide/protein sequences. | Web service |

The integration of KEGG, BioCyc, and MetaCyc provides a powerful, multi-faceted framework for tackling the complex challenge of metabolic pathway reconstruction in non-model organisms. While KEGG offers a broad, systems-level view integrated with disease and drug data, MetaCyc provides deep, experimentally-validated metabolic information crucial for accurate prediction, and the BioCyc collection enables scalable, organism-specific reconstruction and comparison. The ongoing curation and expansion of these resources—evidenced by MetaCyc's addition of 41 new pathways in its latest release—ensure they remain at the forefront of biological discovery [29]. For researchers investigating non-model organisms, a strategic approach that leverages the complementary strengths of these databases, combined with the experimental protocols outlined herein, will significantly accelerate the elucidation of metabolic networks, thereby enabling advances in fields ranging from synthetic biology to drug discovery.

From Sequence to System: Computational and Experimental Reconstruction Workflows

Metabolic pathway reconstruction is a foundational step in systems biology, enabling researchers to decipher the biochemical capabilities of an organism from its genomic sequence. For researchers working with non-model organisms—species not represented in standard reference databases—this process presents a significant challenge. The choice of computational strategy, primarily between reference-based (alignment) and de novo approaches, directly influences the accuracy, completeness, and biological relevance of the resulting metabolic models [35] [36]. Reference-based methods offer efficiency but can overlook novel biology, whereas de novo methods promise discovery at the cost of greater computational complexity. This application note delineates these strategies, provides quantitative performance comparisons, and outlines detailed protocols for their application, specifically within the context of non-model organism research.

Comparative Analysis of Pathway Prediction Strategies

The two primary strategies for metabolic pathway prediction differ fundamentally in their philosophy and implementation. Reference-based (or alignment-based) prediction relies on mapping sequencing reads or gene calls to pre-existing databases of known genes, pathways, and genomes. In contrast, de novo prediction reconstructs metabolic pathways directly from sequencing data without relying on reference genomes, often through the assembly of reads into contigs and the subsequent annotation of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [35].

A recent large-scale comparison of these methods using human gut microbiota data revealed critical differences in their outputs (Table 1) [35].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Reference-Based and De Novo Approaches for Microbiome Analysis

| Performance Metric | Reference-Based (AL) | De Novo (DN) |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Power | Higher; identified a larger number of statistically significant taxa associated with BMI [35] | Lower; produced a subset of the significant findings from AL [35] |

| Result Sparsity | Lower sparsity of the result matrix [35] | Higher sparsity of the result matrix [35] |

| Sensitivity to Host Factors | Higher explained variance (~8.7%) in PERMANOVA analysis [35] | Lower explained variance in PERMANOVA analysis [35] |

| Archaeal Detection | ~0.4% relative abundance [35] | ~0.9% relative abundance [35] |

| Key Strength | Efficiency and sensitivity for profiling known biology [35] | Discovery of novel taxa, genes, and genomic regions [35] |

| Primary Limitation | Reference database bias; may miss novel elements [35] | High computational resource requirements; expertise needed [35] |

The strategic choice between these methods hinges on the research goal. Reference-based methods are optimal for well-characterized communities or when resources are limited, while de novo approaches are indispensable for exploring true novelty and for generating robust, population-specific genomic resources that serve as a foundation for metabolic reconstruction [35] [36].

Semantic Design: A Novel Paradigm for De Novo Generation

Beyond reconstructing existing pathways, a transformative new approach called semantic design now enables the de novo generation of novel functional genetic elements. This method uses a genomic language model, Evo, which learns the "distributional semantics" of gene function—the principle that a gene's function can be inferred from the functional context of its genomic neighbors [37].

The model is trained on prokaryotic genomes to perform a genomic "autocomplete." When prompted with a DNA sequence encoding a function of interest (e.g., a toxin gene), the model generates novel, functionally related sequences (e.g., its cognate antitoxin) [37]. This process has been experimentally validated to design functional anti-CRISPR proteins and toxin-antitoxin systems, including proteins with no significant sequence similarity to any known natural protein [37]. This approach is particularly powerful for non-model organisms where characterized genetic parts are scarce, as it allows for the computational design of custom, functional genetic systems from first principles.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Reference-Based Pathway Reconstruction Using gapseq

gapseq is a tool that provides informed prediction of bacterial metabolic pathways and reconstructs accurate metabolic models. It combines homology searching with a curated reaction database and a novel gap-filling algorithm [8].

Step 1: Software Installation

Step 2: Database Curation gapseq uses a manually curated database derived from ModelSEED biochemistry, comprising 15,150 reactions and 8,446 metabolites. The tool automatically checks for updates to its reference protein sequences from UniProt and TCDB upon execution [8].

Step 3: Pathway Prediction Run the main gapseq pipeline using a genome assembly in FASTA format.

The

findcommand identifies pathways based on sequence homology to a database of 131,207 unique reference sequences [8].Step 4: Model Reconstruction and Gap-Filling

This step uses a Linear Programming (LP)-based algorithm to resolve network gaps, enabling biomass formation on a specified growth medium. The algorithm also fills gaps for functions supported by sequence homology, reducing medium-specific bias and increasing model versatility [8].

Validation: gapseq has been validated against 14,931 bacterial phenotypes, showing a 53% true positive rate for enzyme activity prediction, outperforming other tools like CarveMe (27%) and ModelSEED (30%) [8].

Protocol 2: De Novo Reconstruction from Metagenomic Data

This protocol outlines the process for reconstructing metabolic pathways directly from metagenomic sequencing reads, culminating in metabolic models for MAGs.

Step 1: Quality Control and Assembly

Step 2: Binning and Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MAG) Curation

Check MAG quality (completeness and contamination) with tools like CheckM.

Step 3: Functional Annotation and Pathway Prediction Annotate the high-quality MAGs using a tool like gapseq, following Protocol 1, but using the MAG as the input genome. This leverages the strength of de novo discovery (MAGs) with the powerful pathway prediction of a reference-based tool [35].

Step 4: Community Metabolic Modeling Reconstruct metabolic models for each MAG and build a community model. The APOLLO resource, for instance, has demonstrated the construction of 14,451 sample-specific microbiome community models to interrogate community-level metabolic capabilities, which can be stratified by body site, age, and disease state [38].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for choosing and applying the appropriate computational strategy for metabolic pathway reconstruction in non-model organisms.

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Databases for Metabolic Reconstruction

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| gapseq [8] | Software Pipeline | Automated metabolic pathway prediction and model reconstruction from a genome. | Uses a curated reaction database and a novel LP-based gap-filling algorithm. Outperforms others in carbon source utilization prediction. |

| Evo Model [37] | Genomic Language Model | De novo generation of functional genes and systems via semantic design. | Leverages genomic context (e.g., operon structure) to generate novel sequences for targeted functions like anti-CRISPRs. |

| APOLLO Resource [38] | Metabolic Model Database | A resource of 247,092 genome-scale metabolic reconstructions for human microbes. | Enables systems-level modeling of personalized host-microbiome co-metabolism across body sites, ages, and geographies. |

| MetaPhlAn4 [35] | Alignment-based Profiler | Taxonomic profiling of metagenomic samples. | Rapidly maps reads to a database of clade-specific marker genes for efficient community composition analysis. |

| HUMAnN3 [35] | Alignment-based Profiler | Profiling of metabolic pathways in metagenomes. | Quantifies abundance of microbial pathways by mapping reads to a curated database of protein families and metabolic modules. |

| UniProt/TCDB [8] | Protein/Transporter Database | Curated source of protein sequences and transporter classifications. | Forms the core reference database for tools like gapseq to identify homologous genes and predict metabolic functions. |

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational representations of the entire metabolic network of an organism, constructed from its annotated genome sequence [39]. These models mathematically describe the gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations for all metabolic genes, enabling researchers to simulate metabolic fluxes and predict phenotypic behaviors under various genetic and environmental conditions [40]. The fundamental component of a GEM is the stoichiometric matrix (S matrix), where columns represent reactions, rows represent metabolites, and entries correspond to stoichiometric coefficients [39]. GEMs have become indispensable tools in systems biology and metabolic engineering, particularly through the application of flux balance analysis (FBA), which uses linear programming to predict optimal flux distributions through metabolic networks under steady-state assumptions [39] [41].

The reconstruction of high-quality GEMs for non-model organisms presents both challenges and significant opportunities. While model organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have well-established, iteratively refined GEMs, non-model organisms often possess unique metabolic capabilities that make them valuable industrial chassis but lack the comprehensive biological data needed for straightforward model reconstruction [42] [43]. The bacterium Zymomonas mobilis exemplifies this scenario—it exhibits extraordinary industrial characteristics including high sugar uptake rate, high ethanol yield, and exceptional ethanol tolerance, making it a promising platform for biomanufacturing [42] [43]. However, its development as a biorefinery chassis has been hampered by its dominant ethanol production pathway, which restricts the titer and rate of other valuable biochemicals [42]. This review examines the construction and application of two successive GEMs for Z. mobilis—iZM516 and its enzyme-constrained successor eciZM547—as paradigmatic cases for metabolic pathway reconstruction in non-model organisms.

Model Reconstruction and Development: From iZM516 to eciZM547

iZM516: A High-Quality Foundation Model

The iZM516 model was developed to address limitations in existing Z. mobilis GEMs, which suffered from issues such as incorrect ATP generation, missing plasmid gene information, and lack of standard format files [43]. This comprehensive model contains 516 genes, 1,389 reactions, 1,437 metabolites, and 3 cell compartments, achieving the highest MEMOTE evaluation score (91%) among all published Z. mobilis models at the time of its publication [43]. The reconstruction process integrated improved genomic annotation including native plasmid information, experimental data from Biolog Phenotype Microarray studies, and manually curated Gene-Protein-Reaction relationships from multiple databases [43].

A critical advancement in iZM516 was the proper representation of Z. mobilis's unique metabolic characteristics, particularly its utilization of the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway under anaerobic conditions—a rare capability among known microorganisms [42] [43]. The model accurately simulates the ATP yield from glucose metabolism, correctly representing the production of 1 mol ATP per 1 mol glucose under anaerobic conditions, unlike previous models that generated biologically implausible amounts [43]. When validated against experimental substrate utilization data, iZM516 demonstrated 79.4% accuracy in predicting cell growth, establishing it as a reliable platform for metabolic engineering design [43].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of iZM516 and eciZM547

| Feature | iZM516 | eciZM547 |

|---|---|---|

| Genes | 516 | 547 |

| Reactions | 1,389 | 1,455 |

| Metabolites | 1,437 | 1,455 |

| Compartments | 3 | 3 |

| Constraints Type | Stoichiometric | Enzyme-constrained |

| MEMOTE Score | 91% | Not specified |

| Key Application | Succinate and 1,4-BDO pathway design | D-lactate production via DMCI strategy |

eciZM547: Integration of Enzyme Constraints

The iZM516 model was subsequently upgraded to eciZM547 through the integration of enzyme constraints that reflect limitations related to protein resources during cell growth [42]. This enzyme-constrained model (ecModel) was developed using ECMpy2 and Kcat values provided by AutoPACMEN, which was determined to be more accurate than other methods such as DLkcat, TurNup, and UniKP [42]. The resulting eciZM547AutoPACMENmean (abbreviated as eciZM547) contains 547 genes, 1,455 metabolites, and represents the enzyme-constrained metabolic network model closest to experimental results [42].

The integration of enzyme constraints fundamentally improved the predictive capabilities of the model. Most notably, eciZM547 revealed a shift from glucose-limited growth to proteome-limited growth when glucose uptake exceeded approximately 71 mmol·gDW⁻¹·h⁻¹ [42]. This constrained simulation predicted a maximum growth rate of 0.50 h⁻¹ and a maximum ethanol production rate of 134.76 mmol·gDW⁻¹·h⁻¹, representing more biologically realistic values than the previous model, which highly overestimated these parameters [42]. Additionally, while iZM516 predicted that most carbon sources would be directed toward acetate based on growth criteria when glucose was the sole carbon source, eciZM547 more accurately simulated carbon flux into both acetate and acetoin, aligning with experimental ¹³C-metabolic flux analysis (MFA) data [42].

Diagram 1: GEM reconstruction workflow from iZM516 to eciZM547

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Base GEM Reconstruction (iZM516)

The reconstruction of a high-quality GEM for a non-model organism like Z. mobilis requires systematic curation and integration of diverse data sources. The following protocol outlines the key steps employed in developing iZM516:

Draft Reconstruction: Utilize the latest genomic information from NCBI (chromosome: NZ_CP023715.1, plasmids: pZM32, pZM33, pZM36, pZM39) with the Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) server and the ModelSEED database to automatically generate a draft model [43].

Annotation and ID Conversion: Convert temporary gene IDs from RAST to specific IDs and names of Z. mobilis ZM4 using BLASTp with thresholds set at e-value ≤10⁻⁵ and identity ≥40% [43].

Biomass Equation Curation: Define biomass composition to include DNA, RNA, proteins, lipids, peptidoglycan, carbohydrates, and small molecules. For Z. mobilis, specifically incorporate the hopane biosynthesis pathway as this is an important membrane component contributing to ethanol tolerance [43].

Manual Curation and Gap Filling: Identify biomass precursors that cannot be synthesized and employ a weight-added pFBA algorithm for gap filling. Set reactions in the draft model with a weight of 1000 and the upper limit of the biomass equation to 0.1 to minimize the number of filling reactions introduced from the ModelSEED database [43].

Validation with Experimental Data: Test the model's predictive accuracy against experimental Biolog Phenotype Microarray results for substrate utilization, with iZM516 achieving 79.4% agreement with experimental growth results [43].

Quality Assessment: Evaluate the model using the standard genome-scale metabolic model test suite MEMOTE, with iZM516 achieving a score of 91% [43].

Protocol for Enzyme-Constrained Model Development (eciZM547)

The transformation of a stoichiometric GEM to an enzyme-constrained model enhances its predictive accuracy by accounting for proteome limitations:

Model Enhancement: Begin with the iZM516 model and incorporate unique genes and reactions from complementary models like iZM4_478 through manual curation to create an enhanced stoichiometric model (iZM547) [42].

Enzyme Constraint Integration: Apply the ECMpy2 computational pipeline to integrate enzyme constraints using Kcat values from the AutoPACMEN tool, which demonstrates superior accuracy compared to alternative methods [42].

Proteome Allocation Modeling: Implement constraints that reflect the trade-off between biomass yield and enzyme usage efficiency, capturing the shift from substrate-limited to proteome-limited growth [42].

Validation with ¹³C-MFA: Compare model predictions with experimental ¹³C-metabolic flux analysis data under relevant conditions (e.g., aerobic growth) to verify accurate prediction of carbon flux distributions [42].

Simulation of Metabolic Phenotypes: Utilize the constrained model to simulate overflow metabolism and identify rate-limiting enzymes in engineered strains [42].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for GEM Reconstruction

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in GEM Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|

| RAST Server | Online Tool | Automated genome annotation and draft model generation |

| ModelSEED Database | Database | Biochemical database for reaction and metabolite information |

| MEMOTE Suite | Software | Quality assessment and validation of model structure |

| Biolog Phenotype Microarray | Experimental Assay | Validation of model predictions against experimental growth data |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Package | MATLAB-based tools for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis |

| ECMpy2 | Computational Pipeline | Integration of enzyme constraints into stoichiometric models |

| AutoPACMEN | Algorithm | Prediction of enzyme Kcat values for constraint implementation |

| MetaCyc Database | Database | Curated database of metabolic pathways and enzymes |

Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Bioprocessing

Metabolic Engineering Strategies Enabled by iZM516

The iZM516 model has served as a powerful computational platform for designing metabolic engineering strategies in Z. mobilis. Through in silico simulations under anaerobic conditions, researchers used iZM516 to design pathways for producing valuable chemicals including succinate and 1,4-butanediol (1,4-BDO) [43]. The model predicted that combinatorial metabolic engineering strategies could achieve yields of 1.68 mol/mol succinate and 1.07 mol/mol 1,4-BDO from glucose, comparable to the performance of established model species like E. coli [43]. These predictions demonstrated the potential of Z. mobilis as a chassis for producing chemicals beyond its native ethanol production.

Additionally, iZM516 enabled the identification of potential endogenous succinate synthesis pathways in Z. mobilis ZM4, providing insights into the native metabolic capabilities of this non-model organism [43]. The model was also used to design and simulate metabolic pathways for various other biochemicals, including 1,3-propanediol (1,3-PDO) from glycerol, butanediol from glucose, xylonic acid, ethylene glycol, glycolic acid, and 1,4-butanediol from xylose [42]. This versatility highlights how high-quality GEMs can expand the biotechnological application range of non-model organisms.

The DMCI Strategy and D-Lactate Production

A groundbreaking application enabled by the eciZM547 model was the development of a dominant-metabolism compromised intermediate-chassis (DMCI) strategy to bypass Z. mobilis's innate dominant ethanol production pathway [42]. This approach involved introducing a low-toxicity but cofactor-imbalanced 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BDO) pathway to create an intermediate chassis, rather than directly engineering the chassis for target biochemicals [42]. The compromised chassis could then be more effectively redirected toward high-yield production of target compounds.

This DMCI strategy, guided by predictions from eciZM547, led to the construction of a recombinant D-lactate producer capable of producing more than 140.92 g/L from glucose and 104.6 g/L from corncob residue hydrolysate, with a remarkable yield exceeding 0.97 g/g glucose [42]. Techno-economic analysis (TEA) and life cycle assessment (LCA) further demonstrated the commercial feasibility and greenhouse gas reduction capability of producing D-lactate from lignocellulosic waste, validating the industrial relevance of this model-guided approach [42].

Diagram 2: DMCI strategy for D-lactate production

The development and refinement of genome-scale metabolic models from iZM516 to eciZM547 exemplify the critical role of computational modeling in advancing metabolic engineering of non-model organisms. The iterative enhancement of these models—from a high-quality stoichiometric foundation to an enzyme-constrained framework capable of predicting proteome-limited growth—demonstrates how GEMs can evolve to incorporate increasing layers of biological complexity. The successful application of these models to guide metabolic engineering strategies, particularly the innovative DMCI approach for bypassing native regulatory networks, highlights the transformative potential of GEMs in enabling non-model organisms like Z. mobilis to serve as efficient biorefinery chassis for sustainable biochemical production.

Future developments in GEM reconstruction for non-model organisms will likely focus on integrating additional cellular constraints beyond metabolism, including transcriptional regulation, signaling networks, and resource allocation across cellular processes. The integration of machine learning approaches with GEMs, as well as the development of multi-strain and community-level models, will further expand the predictive capabilities and application scope of these computational frameworks [41]. As these tools continue to evolve, they will accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle in synthetic biology, enabling more efficient engineering of non-model organisms for circular bioeconomy applications. The iZM516 and eciZM547 models for Z. mobilis thus represent both practical tools for metabolic engineers and paradigmatic cases for GEM development in industrially relevant but genetically recalcitrant microorganisms.

Gene Editing with CRISPR-Cas Systems for Pathway Engineering in Non-Model Bacteria and Fungi

The pursuit of sustainable biomanufacturing has catalyzed the exploration of non-model microorganisms as next-generation cellular factories. Unlike their model counterparts, these organisms possess unique and versatile metabolic characteristics, enabling them to thrive on diverse feedstocks, tolerate extreme fermentation conditions, and synthesize novel high-value compounds [44]. However, the full potential of these microbial chassis has been historically locked behind a significant challenge: the lack of efficient genetic tools for precise pathway engineering. The advent of CRISPR-Cas systems has begun to dismantle this barrier, offering a versatile and powerful platform for domesticating non-model bacteria and fungi. This document details specialized application notes and protocols, framed within the broader thesis of metabolic pathway reconstruction, to equip researchers with the methodologies needed to harness non-model organisms for applied biotechnology and drug development.