Metabolic Steady State: The Critical Foundation for Accurate Flux Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article explores the indispensable role of metabolic steady state as a foundational assumption in metabolic flux analysis (MFA).

Metabolic Steady State: The Critical Foundation for Accurate Flux Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the indispensable role of metabolic steady state as a foundational assumption in metabolic flux analysis (MFA). Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it examines how steady-state conditions enable reliable quantification of metabolic reaction rates in systems biology. The content covers fundamental principles, methodological applications across various MFA techniques, troubleshooting approaches for experimental challenges, and validation frameworks for comparing steady-state with dynamic methods. By synthesizing current computational and experimental advances, this resource provides practical guidance for implementing robust flux analysis in metabolic engineering, disease mechanism investigation, and therapeutic development.

Understanding Metabolic Steady State: The Bedrock Principle of Flux Analysis

Metabolic steady state describes a fundamental condition in biochemical systems where the influx and efflux of metabolites for a given metabolic pool are balanced, resulting in constant concentrations over time despite ongoing turnover [1]. This concept is not synonymous with thermodynamic equilibrium, as it describes an open system requiring a continuous input of energy and nutrients to maintain homeostasis. The definition and accurate determination of metabolic steady state are foundational to flux analysis research, as it provides the necessary framework for quantitatively describing metabolic phenotypes and understanding cellular functional behavior after environmental or genetic perturbations [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this concept enables the systematic investigation of disease mechanisms, identification of therapeutic targets, and optimization of biotechnological processes through precise metabolic engineering.

Core Conceptual Framework

Fundamental Definitions and Distinctions

- Metabolic Steady State: A condition where all metabolic fluxes and metabolite concentrations remain constant over time [2]. This state allows for continuous metabolic flux without net accumulation or depletion of pathway intermediates.

- Isotopic Steady State: A specific condition where the incorporation of isotopic tracers (e.g., 13C) into metabolic pools has become constant over time [2]. This state may be reached independently of the metabolic steady state and is critical for many flux analysis techniques.

- Maximal Metabolic Steady State: The highest oxidative metabolic rate that can be sustained during continuous exercise without progressive fatigue, representing the boundary between heavy and severe-intensity exercise domains [3].

The distinction between these states is crucial for experimental design. A system can be in metabolic steady state without being in isotopic steady state, particularly during tracer experiments before complete isotope incorporation [2].

Mathematical Representation

The mathematical foundation of metabolic steady state is represented by the balance equation: [ S \cdot v = 0 ] where (S) is the stoichiometric matrix defining the metabolic network structure, and (v) is the vector of metabolic fluxes [4]. This equation forms the basis for constraint-based modeling approaches, including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which enables quantitative predictions of metabolic behavior.

For a simple linear metabolic pathway where metabolite (B) is produced from (A) and converted to (C), the steady state condition is described by: [ \frac{d[B]}{dt} = k1[A] - k2[B] = 0 ] where (k1) and (k2) are rate constants, yielding ([B] = \frac{k1}{k2}[A]) at steady state [1].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Metabolic Steady States

| State Type | Primary Condition | Time Dependency | Experimental Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Steady State | Constant metabolite concentrations and fluxes | Maintained during balanced growth | Enables flux quantification |

| Isotopic Steady State | Constant isotope labeling patterns | Reached after sufficient tracer exposure | Permits 13C-MFA |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary State | Transient isotope labeling patterns | Early time points after tracer introduction | Enables INST-MFA |

| Maximal Metabolic Steady State | Highest sustainable metabolic rate | Boundary condition for endurance | Determines sustainable exercise intensity |

Analytical Frameworks for Steady-State Investigation

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) Techniques

Multiple computational approaches have been developed to investigate metabolism at steady state conditions, each with distinct capabilities and limitations.

Table 2: Comparison of Major Metabolic Flux Analysis Techniques

| Method | Abbreviation | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State | Scale | Temporal Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis | FBA | Required | Not Required | Genome-scale | Static |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis | MFA | Required | Not Required | Central metabolism | Static |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis | 13C-MFA | Required | Required | Central metabolism | Static |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA | INST-MFA | Required | Not Required | Central metabolism | Dynamic (minutes-hours) |

| Dynamic MFA | DMFA | Not Required | Not Required | Central metabolism | Dynamic (hours) |

| COMPLETE-MFA | COMPLETE-MFA | Required | Required | Central metabolism | Static |

Advanced Computational Approaches

Recent methodological advances have enhanced flux analysis capabilities:

Bayesian 13C-MFA: This approach extends traditional flux estimation by incorporating probability distributions, providing a measure of uncertainty in flux predictions [5]. Bayesian methods facilitate multi-model inference, making the analysis robust to model selection uncertainty through techniques like Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA).

Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) Modeling: A computational framework that dramatically reduces the complexity of INST-MFA by decomposing metabolic networks into smaller subunits, enabling efficient simulation of isotopic labeling patterns [2].

Kinetic Modeling: Dynamic models constructed from time series metabolome data can predict metabolic behaviors beyond steady-state conditions, revealing regulatory mechanisms and responses to perturbations [4].

Experimental Methodologies

Establishing Metabolic Steady State in Cell Cultures

The standard protocol for 13C-MFA requires careful preparation and monitoring to ensure proper steady state conditions [2]:

Pre-culture Preparation: Cells are cultivated in non-labeled medium under controlled conditions (constant temperature, pH, oxygen tension) for multiple generations until balanced growth is achieved, indicated by constant biomass composition and metabolic rates.

Labeled Tracer Introduction: Once metabolic steady state is established, the medium is replaced with an identical formulation containing 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [U-13C] glucose, [1,2-13C] glucose).

Isotopic Steady State Monitoring: Cells continue cultivation until isotopic steady state is reached, where isotope incorporation into intracellular metabolites becomes static. This process may require 4 hours to several days depending on the cell type.

Metabolic Quenching: Metabolism is rapidly arrested using cold methanol or other quenching solutions (-40°C) to preserve in vivo metabolite levels.

Metabolite Extraction: Intracellular metabolites are extracted using appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol/water, chloroform/methanol), followed by centrifugation and collection of the aqueous phase.

Analytical Techniques for Steady-State Verification

Mass Spectrometry (MS): Provides high sensitivity for detecting isotopic labeling patterns in metabolic intermediates. LC-MS and GC-MS are widely employed for targeted quantification of metabolite concentrations and isotopic enrichment [2].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Offers structural information about isotopic incorporation and enables absolute quantification without the need for standard curves. Particularly valuable for positional isotopomer analysis [2].

Validation Measurements: Steady state conditions should be verified through multiple parameters, including constant biomass growth rate, stable extracellular nutrient concentrations, and consistent metabolic byproduct secretion rates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Steady-State Investigations

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Carbon sources for tracer studies; enable flux quantification | [U-13C] glucose, [1,2-13C] glucose, 13C-glutamine, 13C-NaHCO3 |

| Quenching Solutions | Rapidly halt metabolism; preserve in vivo metabolite levels | Cold methanol (-40°C), liquid nitrogen |

| Extraction Solvents | Extract intracellular metabolites for analysis | Methanol/water, chloroform/methanol mixtures |

| Internal Standards | Enable absolute quantification of metabolites | Stable isotope-labeled internal standards |

| Cell Culture Media | Defined environment for steady-state maintenance | Custom formulations with precise nutrient composition |

| MS Analysis Columns | Separate metabolites prior to mass spectrometry | HILIC, reverse-phase chromatography columns |

| NMR Reference Standards | Chemical shift calibration and quantification | TSP, DSS, known concentration of reference compounds |

Steady State in Physiological Contexts

Maximal Metabolic Steady State in Exercise Physiology

The maximal lactate steady state (MLSS) represents a critical physiological steady state, defined as the highest exercise intensity at which blood lactate concentration remains stable (increase <1 mmol/L between 10-30 minutes) [3]. This concept has evolved from earlier fixed-threshold models (e.g., 4 mmol/L OBLA) to recognize inter-individual variability. MLSS determination requires multiple 30-minute constant-load exercise tests across different days, identifying the highest power output or running speed that does not exhibit progressive blood lactate accumulation.

Critical power (CP) provides an alternative approach to defining maximal metabolic steady state, derived from the hyperbolic relationship between exercise intensity and tolerance time [3]. While MLSS and CP are conceptually similar, methodological differences typically result in MLSS occurring at slightly lower intensities than CP. Evidence suggests that CP alone represents the genuine boundary between exercise intensity domains where physiological homeostasis can be maintained.

Dynamic Responses to Perturbations

Metabolic systems exhibit characteristic responses when disturbed from steady state:

Linear Responses: Simple synthesis and degradation systems where metabolite concentrations respond proportionally to changes in input signals [1].

Hyperbolic Responses: Enzyme-catalyzed reactions following Michaelis-Menten kinetics, producing hyperbolic relationships between substrate concentration and reaction rate [1].

Sigmoidal Responses: Allosterically regulated systems exhibiting cooperative binding, creating switch-like responses to metabolic signals [1].

Applications in Metabolic Research and Drug Development

Disease Mechanism Elucidation

Metabolic steady state analysis provides critical insights into pathological mechanisms:

Cancer Metabolism: 13C-MFA has revealed how cancer cells reprogram central carbon metabolism to support rapid proliferation, including enhanced glycolytic flux despite oxygen availability (Warburg effect) and redirected TCA cycle intermediates for biosynthetic precursors.

Metabolic Disorders: Flux analysis enables quantification of in vivo metabolic dysregulation in diabetes, obesity, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, identifying key nodal points in metabolic networks that contribute to disease progression.

Neurological Diseases: Alterations in brain energy metabolism and neurotransmitter cycling have been quantified using 13C-MFA in neurodegenerative disorders, providing insights into bioenergetic deficits.

Drug Discovery and Development

The implementation of metabolic steady state concepts in pharmaceutical research includes:

Target Identification: 13C-MFA pinpoints metabolic enzymes whose inhibition would most effectively disrupt pathological fluxes, prioritizing therapeutic targets [2].

Toxicology Assessment: Flux analysis predicts off-target metabolic effects of drug candidates, identifying potential toxicity mechanisms before clinical trials [2].

Therapeutic Efficacy Evaluation: Monitoring metabolic flux changes following treatment provides mechanistic insights into drug action and potential resistance mechanisms.

Personalized Medicine: Individual variations in metabolic network operation can inform patient stratification and treatment selection based on specific metabolic vulnerabilities.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of metabolic flux analysis continues to evolve with several promising directions:

Multi-Omics Integration: Combining fluxomics with genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics data provides a systems-level understanding of metabolic regulation [6].

Single-Cell Flux Analysis: Emerging technologies aim to resolve metabolic heterogeneity within cell populations, moving beyond population-averaged measurements.

Dynamic Flux Mapping: INST-MFA and DMFA techniques are advancing toward comprehensive in vivo flux determination with temporal resolution [2].

Bayesian Framework Adoption: Probabilistic approaches are gaining traction for handling model uncertainty and providing robust flux estimates [5].

Clinical Translation: Standardized protocols for human metabolic flux determination are enabling direct investigation of human diseases and therapeutic interventions [6].

The precise definition and experimental control of metabolic steady state remains fundamental to advancing our understanding of cellular metabolism in health and disease. For research scientists and drug development professionals, mastery of these concepts enables the quantitative dissection of metabolic phenotypes, accelerating both basic discovery and therapeutic innovation.

In the study of cellular metabolism, the principle of dynamic homeostasis is paramount. Within this framework, metabolic flux analysis (MFA) has emerged as a powerful methodology for quantifying the in vivo rates of metabolic reactions, providing insights that static "statomics" (e.g., metabolite concentrations, mRNA levels) cannot offer [7] [8]. The accurate determination of these fluxes relies entirely on a rigorous mathematical foundation built upon two core concepts: mass balance equations and stoichiometric constraints. These principles enforce the conservation of mass and elemental balance within biochemical networks, enabling researchers to resolve intracellular metabolic fluxes that are otherwise impossible to measure directly [7] [9]. This technical guide details the fundamental mathematics, computational methodologies, and experimental protocols that underpin flux analysis, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals working to understand and manipulate cellular metabolism in both physiological and pathological contexts.

Fundamental Principles: Mass Balance and Stoichiometry

The Law of Mass Conservation

The law of conservation of mass states that matter cannot be created or destroyed spontaneously [10]. For any defined system, this law can be expressed through a general mass balance equation:

Input + Generation = Output + Accumulation + Consumption [10]

In the context of metabolic networks analysis, this universal principle is applied with specific constraints. For a system without a chemical reaction, or for the total mass in a system with reactions, the equation simplifies to:

Input = Output + Accumulation

Under the assumption of steady state—a cornerstone of many flux analysis techniques—the accumulation term is zero, meaning the concentration of metabolites within the system does not change over time. This reduces the mass balance equation to:

Input = Output

This steady-state assumption is critical for methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), as it transforms the system into a set of solvable linear equations [10] [9].

Stoichiometry in Biochemical Reactions

Stoichiometry describes the quantitative relationships between reactants and products in chemical reactions [11]. Based on the law of conservation of mass, it requires that for each element, the number of atoms of that element in the reactants must equal the number of atoms in the products. In biochemical reactions, these relationships form integer ratios between the reacting molecules [11].

For example, the complete combustion of methane is described by the balanced equation:

CH₄ (g) + 2O₂ (g) → CO₂ (g) + 2H₂O (l)

This equation reveals a 1:2:1:2 molar ratio between methane, oxygen, carbon dioxide, and water, respectively. These stoichiometric coefficients are fundamental for constructing the mathematical models used in flux analysis [11].

Table 1: Key Principles of Mass Balance and Stoichiometry

| Concept | Mathematical Representation | Application in Metabolic Networks |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Balance | Input = Output + Accumulation |

Accounting for metabolite flows in and out of system boundaries |

| Steady-State Assumption | Input = Output (Accumulation = 0) |

Simplifying system to solvable algebraic equations |

| Stoichiometric Coefficients | Integer ratios in balanced equations | Defining constraints in stoichiometric matrix (S) |

| Elemental Balance | Atoms in reactants = Atoms in products | Ensuring conservation of each element (C, H, O, N, etc.) |

Mathematical Frameworks for Metabolic Networks

The Stoichiometric Matrix and Mass Balance Constraints

In constraint-based modeling, metabolic networks are represented mathematically using a stoichiometric matrix (S), where rows correspond to metabolites and columns represent metabolic reactions [9] [12]. Each element Sᵢⱼ in the matrix contains the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j, with negative coefficients for substrates and positive coefficients for products [13].

The mass balance constraints under steady-state conditions can be compactly represented as a system of linear equations:

S · v = 0

where v is the vector of reaction fluxes (rates) [9] [12]. This equation formalizes that for each internal metabolite, the rate of production equals the rate of consumption, preventing unrealistic accumulation or depletion.

Charge Balance in Aqueous Solutions

In addition to mass balance, aqueous biochemical systems must also maintain charge balance—for every positive charge, there must be a corresponding negative charge [14]. This principle is particularly important when modeling ionized species in cellular environments.

For example, in a solution of sodium acetate which dissociates into Na⁺ and CH₃COO⁻, and where acetate can protonate to acetic acid and water can dissociate into H₃O⁺ and OH⁻, the charge balance is expressed as:

[Na⁺] + [H₃O⁺] = [acetate] + [OH⁻]

For ions with multiple charges, such as Ca²⁺ in a calcium chloride solution, the concentration must be multiplied by the ionic charge:

2[Ca²⁺] + [H₃O⁺] = [Cl⁻] + [OH⁻]

This ensures proper accounting of the total positive and negative charges in the system [14].

Computational Methodologies in Flux Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

Flux Balance Analysis is a constraint-based approach that uses linear programming to predict steady-state metabolic fluxes in genome-scale metabolic networks [9] [12]. The core FBA problem is formulated as:

Maximize: Z = cᵀv Subject to: S · v = 0 and: lb ≤ v ≤ ub

where c is a vector of weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the biological objective function (e.g., biomass production, ATP synthesis), and lb and ub are lower and upper bounds on reaction fluxes, respectively [9] [12]. These bounds incorporate physiological constraints such as substrate uptake rates or enzyme capacities.

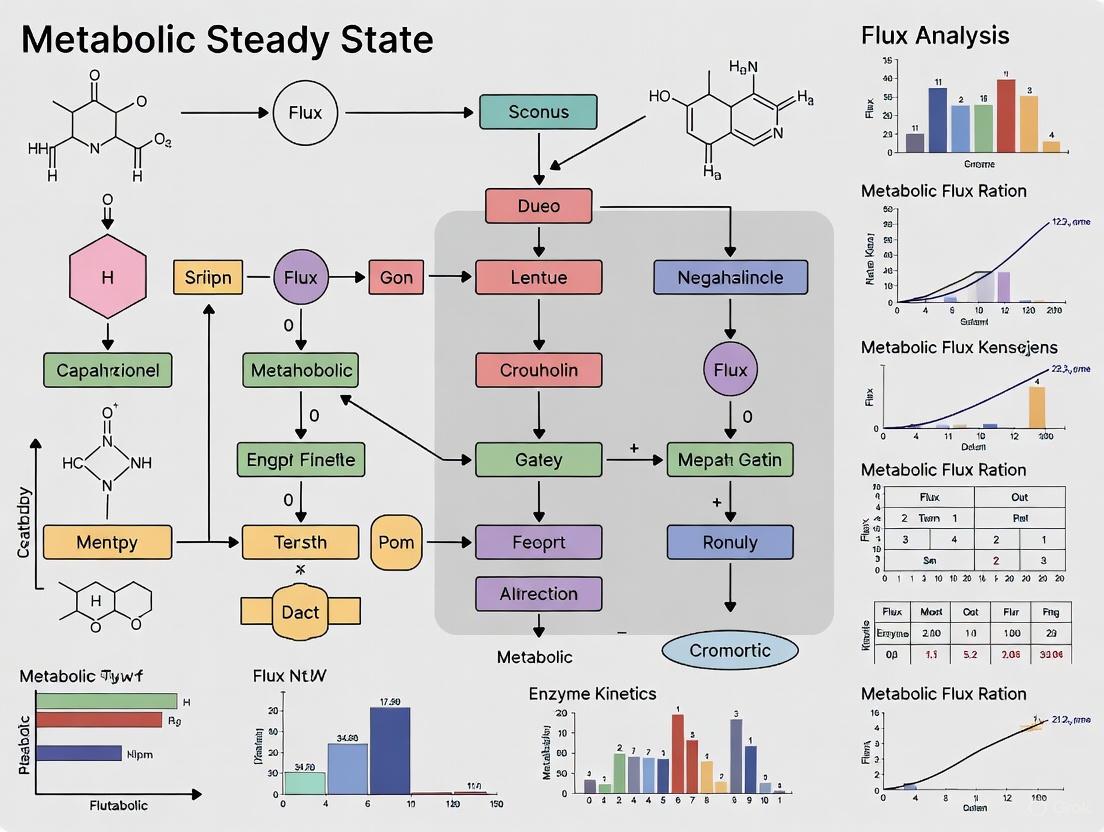

Diagram 1: FBA workflow solving for optimal flux distribution.

FBA does not require kinetic parameters, making it particularly valuable for simulating large-scale metabolic networks where such data are unavailable [9]. The method has been successfully applied to predict microbial growth rates, identify essential genes, and design metabolic engineering strategies for improved chemical production [12].

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis employs stable isotope tracing, typically with 13C-labeled substrates, to determine intracellular fluxes at a finer resolution than FBA [7] [15]. The method leverages both mass balance and isotopic labeling patterns.

At isotopic steady state, the system is described by the isotopomer balance equation:

dMᵢⱼ/dt = Σ₍k∈In(i)₎ vₖ Σ₍Θ∈Gen(k,i,j)₎ Π₍(l,m)ϵΘ₎ rₗₘ - (Σ₍kϵOut(i)₎ vₖ) rᵢⱼ = 0

where Mᵢⱼ is the abundance of the jth isotopomer of metabolite i, In(i) and Out(i) are sets of fluxes producing and consuming metabolite i, vₖ is the flux of reaction k, and rᵢⱼ is the fraction of isotopomer Mᵢⱼ [7].

The fluxes (v) are determined by solving a constrained non-linear least squares problem that minimizes the difference between experimentally measured isotopomer distributions (r_exp) and those simulated from the model (r(v)):

minᵥ ‖r_exp − r(v)‖²

This approach provides quantitative insights into flux partitioning at key metabolic branch points, such as between glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, or between the oxidative and reductive metabolism of glutamine in the TCA cycle [7].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Flux Determination Methods

| Method | Core Constraints | Data Requirements | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Stoichiometric mass balance, Reaction bounds | Network reconstruction, Exchange fluxes | Genome-scale prediction, Growth optimization [9] [12] |

| 13C-MFA | Stoichiometric balance, Isotopomer balance | 13C-labeling patterns, Extracellular fluxes | Central carbon flux resolution, Pathway engineering [7] [15] |

| Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) | Stoichiometric balance, Dynamic labeling | Time-course 13C-labeling data | Rapid kinetic analysis, Non-steady-state systems [7] |

| Flux Ratio Analysis | Mass isotopomer balance at branch points | Mass isotopomer distribution vectors | Relative pathway activities, Qualitative flux evaluation [7] |

Incorporation of Stoichiometry into Path-Finding Approaches

Traditional graph-based path-finding methods often neglect reaction stoichiometry, potentially identifying topologically possible paths that cannot operate in a sustained steady state [13]. The concept of carbon flux paths (CFPs) addresses this limitation by incorporating stoichiometric constraints into path finding via mixed-integer linear programming.

A CFP is defined as a simple path from a source metabolite to a target metabolite that can operate in sustained steady-state [13]. The mathematical formulation ensures that:

- The path follows carbon exchange between metabolites

- A steady-state flux distribution exists that supports the path

- No metabolites are revisited in the path (simple path)

This approach guarantees that identified paths are stoichiometrically feasible, providing more biologically relevant results than purely topological methods [13].

Experimental Protocols for Flux Determination

Protocol for 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

Objective: Quantify intracellular metabolic fluxes in central carbon metabolism.

Principle: Cells are fed with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [U-13C]-glucose), and the resulting labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites are measured at isotopic steady state. These patterns are then used to compute the metabolic flux distribution that best fits the experimental data [7].

Procedure:

Experimental Design

- Select appropriate 13C-labeled tracer based on metabolic pathways of interest

- Design culture system (e.g., bioreactor, multi-well plates) for controlled nutrient delivery

- Ensure metabolic steady state by maintaining constant cell growth and metabolite concentrations

Isotope Labeling Experiment

- Cultivate cells in presence of 13C-labeled substrate until isotopic steady state is reached (typically several hours for mammalian cells)

- Monitor cell growth and extracellular metabolite concentrations

- Quench metabolism rapidly at multiple time points

Sample Processing and Analysis

- Extract intracellular metabolites using appropriate methods (e.g., cold methanol extraction)

- Derivatize metabolites if necessary for analysis

- Measure isotopomer distributions using:

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

Computational Flux Analysis

- Construct stoichiometric model of central metabolism including atom mapping information

- Simulate expected labeling patterns for given flux values

- Solve non-linear least squares problem to find flux distribution that best fits experimental data

- Perform statistical analysis to evaluate flux uncertainties [7]

Diagram 2: 13C-MFA workflow from tracer experiment to flux map.

Protocol for Flux Balance Analysis

Objective: Predict system-level metabolic phenotype from genome-scale metabolic reconstruction.

Principle: Using the stoichiometric matrix and physiological constraints, linear programming is employed to find a flux distribution that maximizes a biological objective function [9] [12].

Procedure:

Model Construction

- Compile genome-scale metabolic reconstruction from annotated genome and biochemical databases

- Formulate stoichiometric matrix (S) with metabolites as rows and reactions as columns

- Define system boundaries (exchange reactions) and compartmentalization if applicable

Constraint Definition

- Apply steady-state mass balance constraint: S · v = 0

- Set reaction flux bounds based on:

- Measured substrate uptake rates

- Known enzyme capacities

- Thermodynamic constraints (irreversibility)

- Define appropriate objective function (e.g., biomass production, ATP synthesis, product formation)

Problem Solution

- Apply linear programming algorithm to solve:

- Maximize Z = cᵀv subject to S · v = 0 and lb ≤ v ≤ ub

- Extract and interpret resulting flux distribution

- Perform sensitivity analysis (e.g., flux variability analysis)

- Apply linear programming algorithm to solve:

Model Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracer for metabolic pathways | >99% isotopic purity; Specific labeling patterns (e.g., [1-13C], [U-13C]) [7] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (2H, 15N, 18O) | Protein/lipid turnover studies, Oxidative metabolism | Non-radioactive; Compatible with living systems [7] [8] |

| Deuterated Water (²H₂O) | In vivo tracer for lipid, DNA, protein synthesis | Administers orally/injectively; Generates multiple metabolic tracers in vivo [8] |

| GC-MS / LC-MS Systems | Measurement of isotopomer distributions | High mass resolution; Quantitative fragmentation patterns [7] [15] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Alternative method for isotopomer analysis | Positional labeling information; Non-destructive [7] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based FBA simulation | Genome-scale modeling; Multiple constraint-based methods [9] |

| Stoichiometric Models | Framework for flux calculations | Organism-specific; Community-curated (e.g., Recon for human metabolism) [9] |

Mass balance equations and stoichiometric constraints form the indispensable mathematical foundation for metabolic flux analysis. These principles enable researchers to move beyond static snapshots of cellular composition to dynamic quantification of metabolic activity—a capability crucial for advancing our understanding of cellular physiology in health and disease. As flux analysis methodologies continue to evolve, particularly with the integration of multi-omics data and more sophisticated computational frameworks, their applications in basic research, biotechnology, and drug development will continue to expand. The rigorous application of these fundamental mathematical principles ensures that predictions of metabolic activity remain grounded in the physicochemical laws that govern all biological systems.

Metabolic flux analysis stands as a cornerstone in systems biology and metabolic engineering, enabling quantitative investigation of cellular physiology. The steady-state assumption—that metabolite concentrations remain constant over time as production and consumption rates balance—provides the foundational constraint that transforms an otherwise intractable biological problem into a computationally feasible one. This technical guide explores the mathematical frameworks, experimental methodologies, and computational tools that leverage steady-state principles to enable precise flux predictions in complex metabolic networks. Within the broader thesis on the importance of metabolic steady state in flux analysis research, we demonstrate how this principle has become indispensable for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to manipulate biological systems for therapeutic and biotechnological applications.

The fundamental challenge in metabolic flux analysis lies in the inherent underdetermination of metabolic networks—most systems contain more reactions than metabolites, creating a situation where infinite flux distributions could theoretically satisfy the basic stoichiometric constraints. The steady-state assumption provides the critical mathematical constraint that makes flux determination computationally tractable. By assuming that intracellular metabolite concentrations remain constant over time (dx/dt = 0), the system can be described by the matrix equation Sv = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the flux vector [9] [12]. This transformation from a dynamic to a static algebraic problem enables the application of powerful computational techniques from linear algebra and optimization.

The steady-state constraint reflects a biological reality where metabolic networks rapidly adjust to maintain homeostasis, particularly in controlled experimental conditions such as continuous cultures or during balanced growth phases in batch cultures. For researchers, this principle enables the prediction of cellular phenotypes from genome-scale metabolic reconstructions, facilitating the identification of drug targets in pathogens [12], the engineering of microbes for biochemical production [16], and the understanding of metabolic dysregulation in diseases such as cancer [17].

Mathematical Foundations: From Stoichiometry to Solution Spaces

The Stoichiometric Matrix and Mass Balance Constraints

At the core of all steady-state flux analysis lies the stoichiometric matrix (S), an m × n mathematical representation where m represents the number of metabolites and n the number of reactions in the network [9]. Each element Sij corresponds to the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j, with negative values indicating consumption and positive values indicating production. The steady-state assumption transforms the system of differential equations that would otherwise describe metabolic dynamics into a homogeneous system of linear equations: Sv = 0 [12].

This matrix formulation imposes mass balance constraints, ensuring that for each metabolite, the combined flux of all producing reactions equals the combined flux of all consuming reactions. For large-scale metabolic networks, this creates a solution space containing all possible flux distributions that satisfy the mass balance constraints. The dimensions of this space are determined by the nullity of S, which corresponds to the number of independent metabolic pathways in the network [9].

Solving Underdetermined Systems Through Optimization

Since metabolic networks typically contain more reactions than metabolites (n > m), the system Sv = 0 is underdetermined, with infinitely many possible flux distributions satisfying the mass balance constraints [9] [12]. To identify biologically relevant flux distributions, constraint-based modeling approaches apply additional constraints:

- Capacity constraints: Upper and lower bounds (vl ≤ v ≤ vu) on reaction fluxes based on enzyme capacity and thermodynamic considerations [18]

- Environmental constraints: Limits on nutrient uptake rates and product secretion [9]

- Biological objectives: Assumptions about evolutionary optimization, such as maximization of biomass production or ATP yield [12]

These constraints collectively define a bounded solution space within which biologically feasible flux distributions must reside. The most common approach to identifying a single solution is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which uses linear programming to find the flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes a specified objective function Z = cTv, where c is a vector of weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the biological objective [9] [12].

Table 1: Key Constraints in Steady-State Flux Analysis

| Constraint Type | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Balance | Sv = 0 | Metabolic intermediates do not accumulate at steady state |

| Capacity Constraints | vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax | Enzyme catalytic limits and thermodynamic feasibility |

| Environmental Constraints | vuptake ≤ vmax_uptake | Nutrient availability in growth medium |

| Optimality Condition | maximize cTv | Evolutionary pressure for metabolic efficiency |

Figure 1: Computational workflow of constraint-based flux analysis under steady-state assumptions

Methodological Approaches: Experimental and Computational Frameworks

Constraint-Based Modeling and Flux Balance Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) represents the most widely used steady-state flux prediction approach, with applications spanning from bioprocess engineering to drug target identification [9] [12]. The FBA workflow begins with a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction, which is converted into a stoichiometric matrix. After applying substrate uptake constraints and defining an objective function (typically biomass production), linear programming identifies the optimal flux distribution. FBA's computational efficiency allows analysis of networks with thousands of reactions in seconds on modern computers, enabling rapid screening of genetic modifications or environmental conditions [12].

The predictive capability of FBA has been extensively validated. For example, FBA predictions of aerobic and anaerobic growth rates in E. coli (1.65 h⁻¹ and 0.47 h⁻¹, respectively) show strong agreement with experimental measurements [9]. This accuracy, combined with minimal parameter requirements, makes FBA particularly valuable for studying poorly characterized systems where kinetic parameters are unavailable.

Isotope-Assisted Metabolic Flux Analysis

While FBA relies solely on stoichiometric constraints, 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) incorporates additional constraints from isotopic labeling patterns to quantify fluxes with higher resolution and accuracy [16] [19]. In 13C-MFA, cells are fed 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose) until isotopic steady state is reached, where the labeling patterns of intracellular metabolites stabilize [16]. Mass spectrometry or NMR then measures these labeling patterns, which provide additional constraints on intracellular fluxes.

The mathematical framework of 13C-MFA extends the basic stoichiometric model by incorporating isotopomer balances, which describe the fate of individual labeled atoms through metabolic networks [19]. This approach is particularly valuable for resolving parallel, cyclic, and reversible pathways that cannot be distinguished using stoichiometric constraints alone [16]. For the past 25 years, 13C-MFA has been considered the gold standard for accurate and precise flux quantification in living cells [16].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for 13C-metabolic flux analysis at isotopic steady state

Advanced and Specialized Flux Analysis Techniques

Several specialized flux analysis methods have been developed to address specific biological questions or experimental constraints:

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): This method identifies the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction while maintaining optimal or suboptimal objective function values [18]. FVA quantifies network flexibility and identifies alternative optimal solutions. Recent computational advances, such as the fastFVA algorithm, have reduced computation times from hours to seconds for genome-scale models [18].

Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA): This approach relaxes the requirement for isotopic steady state, instead using kinetic models of isotopic labeling dynamics to estimate fluxes [16] [19]. INST-MFA is particularly valuable for systems where isotopic steady state is difficult to achieve or for probing transient metabolic states.

Boundary Flux Analysis (BFA): An emerging strategy that focuses on extracellular flux measurements, BFA quantifies nutrient consumption and product secretion rates to infer intracellular pathway activities [20]. This approach is particularly suitable for large-cohort studies due to its relatively simple experimental requirements.

Table 2: Comparison of Steady-State Flux Analysis Methods

| Method | Key Requirements | Computational Demand | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Stoichiometric model, Growth/uptake rates | Low (seconds) | Genome-scale phenotype prediction, Gene essentiality analysis |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) | Isotopic steady state, Labeling measurements | High (hours-days) | Precise central carbon flux determination, Pathway validation |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | FBA solution, Optional suboptimality parameter | Medium (minutes) | Network flexibility assessment, Robustness analysis |

| INST-MFA | Time-course labeling data, Kinetic modeling | Very High (days) | Autotrophic metabolism, Transient state analysis |

| Boundary Flux Analysis (BFA) | Extracellular metabolite measurements | Low (seconds) | Large cohort studies, High-throughput screening |

Successful implementation of steady-state flux analysis requires both experimental reagents and computational tools. Below we detail essential resources for designing flux analysis studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine | Create distinct labeling patterns for pathway resolution; enable 13C-MFA |

| Analytical Instruments | LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry), NMR | Quantify isotopic labeling patterns with atomic resolution |

| Cell Culture Systems | Bioreactors, Chemostats | Maintain metabolic steady state during experimental period |

| Stoichiometric Models | E. coli core model, Human Recon | Provide biochemical reaction networks for constraint-based modeling |

| Computational Tools | COBRA Toolbox, 13CFLUX2, OpenFLUX | Implement FBA, 13C-MFA, and related algorithms |

| Optimization Solvers | GLPK, CPLEX | Solve linear programming problems for FBA and FVA |

Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

The tractability of steady-state flux analysis has enabled transformative applications across biotechnology and medicine. In metabolic engineering, flux analysis guides strain optimization by identifying bottleneck enzymes in biosynthetic pathways and predicting the phenotypic effects of genetic modifications [16] [21]. For example, MFA has been used to optimize biofuel production in engineered microorganisms by quantifying carbon routing through competing pathways and identifying diversion points that limit product yield [19].

In pharmaceutical development, steady-state flux analysis enables drug target identification in pathogens by determining metabolic enzymes essential for growth and survival [12]. Double deletion studies using FBA can identify synthetic lethal gene pairs that represent potential combination therapy targets [12]. Furthermore, the emergence of boundary flux analysis provides a framework for investigating metabolic pathway activities in large patient cohorts, potentially identifying metabolic signatures of disease or treatment response [20].

The steady-state assumption also enables the construction of predictive kinetic models from large-scale 13C-MFA data sets [16]. These models extend beyond flux prediction to simulate metabolite concentration changes in response to genetic or environmental perturbations, providing a more comprehensive understanding of metabolic regulation.

The steady-state assumption provides the mathematical foundation that enables computationally tractable metabolic flux predictions. By transforming dynamic biological systems into constrained algebraic problems, steady-state analysis has allowed researchers to harness powerful computational techniques from linear programming and optimization theory. The continued development of more sophisticated experimental measurements and computational algorithms promises to further expand the applications of steady-state flux analysis in basic research, biotechnology, and medicine. As metabolic modeling increasingly informs therapeutic development and bioprocess optimization, the principles of steady-state analysis will remain essential for converting complex biological networks into quantitatively predictive models.

The comprehensive analysis of metabolic networks necessitates an integrated understanding of their structural topology and functional flux distributions. This whitepaper delineates the critical relationship between network architecture—defined by its stoichiometric connections and modular organization—and the metabolic fluxes that dictate cellular phenotype, with a specific emphasis on the indispensable role of the metabolic steady state as a foundational assumption for quantitative modeling. We present evidence that structural analysis, often leveraging graph-theoretic features, can predict functional capabilities like gene essentiality, sometimes surpassing the predictive power of pure optimization-based functional simulations like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), especially in networks with significant redundancy. This integration is paramount for applications in systems biology and drug discovery, where identifying robust therapeutic targets is a primary objective. The following sections provide a technical guide comparing these methodologies, supported by quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and visual frameworks.

At the core of constraint-based modeling lies the principle of the metabolic steady state. This principle posits that for a system operating at a physiological homeostasis, the concentration of intracellular metabolites remains constant over time. This is mathematically represented as S⋅v = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix of the metabolic network and v is the vector of reaction fluxes [7] [15]. This equation dictates that for any metabolite, the rate of production must equal the rate of consumption, creating a mass balance. The assumption of a steady state is not merely a computational convenience; it is a physiological reality for cells under constant environmental conditions and is the critical enabling constraint that makes the analysis of large-scale metabolic networks tractable [22]. It allows researchers to explore the universe of possible flux distributions that are physically feasible for a given network topology.

The interplay between the static, structural topology of a metabolic network and its dynamic, functional flux distributions is a central theme in systems biology. Structural topology refers to the connectivity of the network—the graph of reactions and metabolites, often analyzed using metrics like centrality and modularity. Functional analysis, in contrast, seeks to determine the actual flow of metabolites through this network (the fluxes) under specific conditions, which represents the phenotypic outcome of the network's operation [23]. The relationship is bidirectional: topology constrains possible fluxes, while functional pressures can influence the evolution of network topology. The metabolic steady state is the essential bridge that connects the permanent structure of the network to its transient functional states.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Network Topology (Structural Analysis)

Structural analysis focuses on the metabolic network as a graph, where nodes are metabolites or reactions, and edges represent biochemical transformations.

- Reaction-Reaction Graph: A directed graph G=(V,E) where vertices V represent metabolic reactions. A directed edge is created from reaction R1 to R2 if a product of R1 is a reactant in R2 [24].

- Currency Metabolite Filtering: To focus on meaningful metabolic transformations, highly connected metabolites like H₂O, ATP, ADP, and NADH are typically excluded from graph construction [24].

- Graph-Theoretic Features: Key metrics used to quantify topological importance include:

- Betweenness Centrality: Measures the number of shortest paths passing through a node, identifying potential bottlenecks [24].

- PageRank: Assesses the relative importance of a node based on the quantity and quality of its connections [24].

- Closeness Centrality: Indicates how close a node is to all other nodes in the network [24].

- Functional Modules: Topological analysis can identify densely connected sets of reactions that often correlate with specific biological functions, such as nucleotide or amino acid synthesis [23].

Flux Distributions (Functional Analysis)

Functional analysis aims to quantify the flow of metabolites through the network, which represents the metabolic phenotype.

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): A constraint-based modeling approach that predicts flux distributions by optimizing a biological objective function (e.g., biomass yield) subject to stoichiometric (S⋅v = 0) and capacity constraints [24] [15]. It provides a simulation of an optimal metabolic state.

- Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA): An umbrella term for techniques that quantify intracellular metabolic fluxes. A key distinction is made between methods that rely on isotopic steady state and those that do not [7] [15].

- 13C-MFA (Isotopic Steady-State): The gold standard for accurate flux quantification. Cells are fed a 13C-labeled substrate until the isotopic labeling of intracellular metabolites reaches a steady state. The distribution of isotopomers is measured via Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and used to compute fluxes [7] [22].

- INST-MFA (Isotopic Non-Steady State): Relaxes the requirement for isotopic steady state, instead using ordinary differential equations to model the dynamics of label incorporation. This is more computationally demanding but allows for the analysis of transient metabolic states [7].

Comparative Analysis: Structural Topology vs. Functional Simulation

A central question is whether a metabolic network's immutable structure or its simulated function is a more robust predictor of core biological properties, such as gene essentiality. A head-to-head comparison reveals distinct strengths and failure modes for each approach.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Topology-Based ML and FBA for Predicting Gene Essentiality in E. coli Core Metabolism [24]

| Metric | Topology-Based Machine Learning Model | Standard FBA (Single-Gene Deletion) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Hypothesis | Essentiality is determined by a gene's structural role in the network. | Essentiality is determined by the simulated impact on an optimized function (e.g., growth). |

| F1-Score | 0.400 | 0.000 |

| Precision | 0.412 | N/A |

| Recall | 0.389 | N/A |

| Key Failure Mode | May overlook genes critical only in specific conditions. | Fails to identify essential genes due to network redundancy; algorithm reroutes flux. |

The data in Table 1 demonstrates a stark contrast. The topology-based model, trained on graph-theoretic features, successfully identified essential genes with moderate accuracy. In profound contrast, the standard FBA approach failed completely, unable to identify any of the known essential genes. This failure is attributed to FBA's inherent reliance on functional optimization in the face of biological redundancy. When a gene is deleted in silico, FBA can readily re-route metabolic flux through alternative pathways or isozymes to maintain the objective function, thereby classifying the gene as non-essential, even when it is critical in a biological context [24]. This suggests that a gene's position in the network topology can be a more reliable indicator of its essentiality than its role in a single, optimized functional state.

Integrative Approaches and Experimental Validation

The most powerful insights often arise from integrating structural and functional analyses with experimental data. This synergy allows for model refinement and validation against real biological systems.

Protocol: 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

This protocol is a benchmark method for experimentally determining intracellular fluxes [7] [22].

Experimental Design:

- Tracer Selection: Choose an appropriate 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose or [U-13C]glutamine). Optimal tracers are often identified via in silico simulation to maximize flux resolution for the pathways of interest.

- Culture & Labeling: Grow cells in a controlled bioreactor under metabolic steady-state conditions (e.g., chemostat culture). Introduce the tracer substrate and allow the system to reach isotopic steady state, where the labeling patterns of intracellular metabolites no longer change.

Sample Processing and Measurement:

- Quenching and Extraction: Rapidly quench cellular metabolism (e.g., using cold methanol) and extract intracellular metabolites.

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the metabolite extract using GC-MS or LC-MS to measure the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of key intermediate metabolites.

Computational Flux Estimation:

- Network Model Construction: Build a stoichiometric model of the central metabolic network, including atom transition information for each reaction.

- Flux Fitting: Solve a large-scale constrained non-linear least squares problem to find the flux map that best reproduces the experimentally measured MIDs. The optimization problem is formally stated as min‖rexp - r(v)‖², subject to S⋅v = 0 and v ≥ 0 [7].

Case Study: Integrating Metabolomics and Modeling to Reveal Modular Activity

A study on Rhizobium etli during nitrogen fixation provides a compelling example of integration. Researchers combined constraint-based modeling with metabolome data (profiling 220 metabolites) to investigate the metabolic phenotype [23].

- Methodology: Metabolite abundances were measured under free-living and nitrogen-fixing conditions using capillary electrophoresis and mass spectrometry (CE-MS). This data was integrated into a genome-scale metabolic model.

- Finding: Topological analysis of the metabolic network identified structural modules. The experimental metabolome data confirmed that these structural modules correlated with functional activity, as metabolites within the same module showed coordinated abundance changes during nitrogen fixation. The study concluded that "the optimal metabolic activity during nitrogen fixation is supported by interacting structural modules" related to nucleic acids, peptides, and lipids [23]. This finding underscores that modular organization, a topological property, is a robust feature of functional metabolic states.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Flux and Topology Analysis

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracer molecules (e.g., [U-13C]-glucose) used to track carbon fate through metabolic pathways. | Essential for 13C-MFA and INST-MFA to resolve intracellular fluxes [7]. |

| Mass Spectrometer (MS) | Analytical instrument for measuring the mass-to-charge ratio of ions to determine isotopomer distributions. | Used in 13C-MFA to measure labeling patterns in metabolites from cellular extracts [7] [22]. |

| Stoichiometric Model (S-matrix) | A mathematical representation of the metabolic network where rows are metabolites and columns are reactions. | The core constraint (S⋅v=0) for both FBA and 13C-MFA [15]. |

| Graph Analysis Software (e.g., NetworkX) | A programming library for creating and analyzing complex networks and calculating graph metrics. | Used to compute topological features like betweenness centrality from a reaction-reaction graph [24]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB/Python software suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) of metabolic models. | Performing FBA, gene deletion studies, and other variants of constraint-based modeling [24]. |

| Equilibrium Dialysis Device | A tool (e.g., 96-well format) for separating unbound molecules from protein-bound molecules across a membrane. | Can be adapted for flux dialysis methods to measure unbound fractions of compounds in protein binding studies [25]. |

Visualizing the Conceptual and Experimental Frameworks

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts and workflows discussed in this guide.

Core Analysis Framework This diagram illustrates the parallel workflows of structural topology analysis (blue) and functional flux analysis (green), both underpinned by the principle of the metabolic steady state (yellow). The dashed red line signifies the critical comparative analysis between the outputs of these two approaches.

13C-MFA Workflow This flowchart details the iterative experimental and computational protocol for 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis, highlighting the critical role of achieving both metabolic and isotopic steady state for accurate flux determination.

This whitepaper delineates the historical trajectory and technical evolution from early isotope tracer studies to the contemporary field of fluxomics, with a particular emphasis on the foundational role of the metabolic steady state. We detail how the principle of isotopic tracing, established in the 1930s, has been integrated with advanced analytical technologies and computational modeling to enable the precise quantification of metabolic fluxes. The critical importance of maintaining and verifying a metabolic steady state for accurate flux determination is highlighted across methodological explanations. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical overview, including structured data, experimental protocols, and key reagent solutions central to flux analysis.

Metabolism is not a static assembly of chemicals but a dynamic network of reactions in constant flux. The inability to inspect these dynamic activities has long been a major barrier to understanding cellular phenotypes [26]. The field of fluxomics has emerged to address this challenge, defined as the study of comprehensive flux within the metabolic network of a cell [27]. Fluxes represent the end outcome of the interaction between gene expression, protein abundance, enzyme kinetics, regulation, and metabolite concentrations, thereby constituting the true metabolic phenotype [27] [28].

The significance of fluxomics lies in its unique position in the omics ontology. Unlike the genome, transcriptome, proteome, or metabolome, which provide static, snapshot information ("statomics"), the fluxome is a dynamic representation of the phenotype [26] [28]. It integrates information from all other 'omics levels, portraying the whole picture of molecular interactions and their functional outputs [29]. This makes fluxomics a powerful tool for investigating metabolic phenotypes in biotechnology, pharmacology, and disease research [29].

Central to all flux determination methods is the concept of the metabolic steady state. Under steady-state conditions, the rates of metabolite production and consumption are balanced, resulting in constant pool sizes over time. This equilibrium is a prerequisite for accurate flux estimation because it simplifies the complex kinetic equations governing metabolic networks. Whether using stoichiometric modeling or isotopic tracer methods, the assumption of a steady state allows researchers to solve for intracellular fluxes that would otherwise be mathematically intractable [27] [28]. The subsequent sections will trace the historical development of the tools that made flux measurement possible, always underpinned by this critical principle.

Historical Foundations: The Isotope Tracer Revolution

The age of the isotope tracer was born in the 1930s following pioneering work by Frederick Soddy, who provided evidence for the existence of isotopes, and Nobel laureates J.J. Thomson and F.W. Aston, who drove forward the development of early mass spectrometers [30]. Rudolf Schoenheimer's seminal experiments using deuterium as an indicator in the study of intermediary metabolism fundamentally shifted the understanding of living matter from static to dynamic; he demonstrated that body constituents are in a constant state of turnover, a process he termed "the dynamic state of body constituents" [26].

The core principle was the use of stable isotopes (e.g., ²H, ¹³C, ¹⁵N, ¹⁸O) to replace atoms in organic compounds. These labeled compounds, or "tracers," are chemically and functionally identical to their endogenous counterparts but differ in mass, making them analytically distinguishable by technologies like mass spectrometry [30]. This allows researchers to introduce a tracer into a biological system and monitor the metabolic fate of the compound over time, providing a dynamic measurement of metabolism [30]. A classic application, detailed in [30], involves introducing a labeled amino acid (e.g., 1,2-¹³C₂ leucine) into a mammalian system via a primed, constant infusion to measure protein turnover rates.

Table 1: Key Stable Isotopes Used in Tracer Studies and Fluxomics

| Isotope | Natural Abundance | Element Replaced | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ¹³C | ~1.1% | Carbon | Carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism; TCA cycle flux |

| ¹⁵N | ~0.4% | Nitrogen | Amino acid and protein turnover; urea cycle flux |

| ²H (D) | ~0.015% | Hydrogen | Lipid synthesis; protein turnover |

| ¹⁸O | ~0.2% | Oxygen | Water flux; energy expenditure |

The subsequent decades saw the refinement of tracer methodologies for monitoring metabolic pathways, probing gene-RNA and protein-metabolite interaction networks in real-time [29]. These techniques became vital for not only biological sciences but also diverse fields like forensics, geology, and art [30]. This progress was almost exclusively driven by the development of new mass spectrometry equipment, from IRMS to GC-MS and LC-MS, which allowed for the accurate quantitation of isotopic abundance in complex samples [30].

Methodological Foundations: From Stoichiometry to Isotopic Labeling

Modern fluxomics relies on two primary technological paradigms: constraint-based stoichiometric modeling and experimental ¹³C-fluxomics. Each has distinct strengths and requirements, particularly regarding the metabolic steady state.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and the Stoichiometric Paradigm

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constraint-based approach that estimates metabolic fluxes by representing the metabolic network as a numerical matrix of stoichiometric coefficients for each reaction [28]. The core principle is to apply mass-balance constraints, assuming the system is at a steady state where the sum of all molar fluxes entering and leaving a metabolite pool is zero [27].

The mathematical formulation is: Sv = 0 Where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the vector of metabolic fluxes. Additional constraints (e.g., reaction reversibility, upper and lower flux boundaries) are applied to reduce the solution space. An objective function (e.g., biomass maximization or ATP production) is then optimized to predict a unique flux distribution [28]. FBA is powerful for genome-scale models and predictive analysis but cannot resolve parallel pathways or enzyme reversibility without additional isotopic data [27].

Diagram 1: The Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) workflow.

¹³C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (¹³C-MFA) and the Experimental Paradigm

¹³C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (¹³C-MFA) is an experimental approach that extends FBA by incorporating data from isotopic tracer experiments. A ¹³C-labeled substrate (e.g., [U-¹³C]-glucose) is introduced to the system, and the resulting isotopic labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites are measured [27]. Under metabolic steady state, these labeling patterns (e.g., mass isotopomer distributions) remain constant, providing extra constraints for the stoichiometric model. This allows ¹³C-MFA to resolve parallel pathways and enzyme reversibilities that FBA cannot [27]. The process involves an iterative computational procedure where simulated labeling patterns are compared to experimental data, and fluxes are adjusted to minimize the difference [27].

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Flux Analysis Methods

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | ¹³C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (¹³C-MFA) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Stoichiometric mass-balance & optimization | Incorporation of isotopic tracer data |

| Steady-State Requirement | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| Isotope Tracer Data | Not required | Required |

| Pathway Resolution | Cannot resolve parallel or reversible pathways | Can resolve parallel & reversible pathways |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale | Smaller, central metabolic networks |

| Primary Output | Predicted flux distribution | Measured & validated flux distribution |

Advanced Frontiers: Spatial Fluxomics and Quantum Computing

Spatial-Fluxomics for Subcellular Compartmentalization

A major recent advancement is the development of spatial-fluxomics, which provides a view of metabolic fluxes within specific subcellular compartments, such as mitochondria and cytosol [31]. This is critical because distinct pools of metabolites and enzymes in organelles allow cells flexibility in adjusting their metabolism.

The spatial-fluxomics approach, as detailed in [31], involves a sophisticated workflow:

- Isotope Tracing in Intact Cells: Cells are fed with ¹³C-labeled nutrients (e.g., [U-¹³C]-glucose or [U-¹³C]-glutamine).

- Rapid Subcellular Fractionation: An optimized protocol using digitonin and centrifugation achieves separation of mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions within 25 seconds. This speed is essential to quench metabolism and prevent changes in metabolite levels and labeling patterns.

- LC-MS Metabolomics: The mass-isotopomer distribution (MID) of metabolites is measured in each fraction.

- Computational Deconvolution: A mathematical model accounts for the ~10% cross-contamination between fractions to infer the true mitochondrial and cytosolic MIDs and pool sizes.

- Compartmentalized Flux Modeling: The deconvoluted data is used to infer metabolic fluxes specifically within the mitochondria and cytosol.

This method revealed, for instance, that in HeLa cells under standard normoxic conditions, reductive glutamine metabolism via IDH1 is the major producer of cytosolic citrate for fatty acid biosynthesis, challenging the canonical view that citrate is primarily derived from glucose oxidation in the mitochondria [31].

Diagram 2: Spatial-fluxomics workflow for subcellular resolution.

The Emergence of Quantum Computational Biology

A nascent but promising frontier is the application of quantum computing to fluxomic problems. A recent study demonstrated that a quantum algorithm can solve the core optimization problem in Flux Balance Analysis [32]. The researchers adapted a quantum interior-point method, using quantum singular value transformation for matrix inversion—a computationally expensive step in classical FBA for very large networks. This approach successfully reproduced classical results for test cases involving glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle [32].

While currently limited to simulations and small models, this quantum approach suggests a potential route to accelerate metabolic simulations as models scale to entire cells or microbial communities, where classical computers face significant bottlenecks [32]. This could one day enable real-time, dynamic flux balance analysis, moving beyond the steady-state constraints of current large-scale models.

Experimental Protocols in Fluxomics

This section provides a detailed methodology for a core fluxomics experiment: the quantification of central metabolic fluxes in cultured mammalian cells using ¹³C tracing and GC-MS.

Protocol: ¹³C-Fluxomic Analysis in Adherent Cell Cultures

Objective: To quantify metabolic fluxes in the central carbon metabolism (glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, TCA cycle) of mammalian cells.

Principle: Cells are cultivated in a steady state with a ¹³C-labeled carbon source (e.g., [U-¹³C]-glucose). The incorporation of the label into proteinogenic amino acids (which reflect the labeling of their precursor metabolites from central metabolism) is measured by GC-MS. These data are used to compute the intracellular flux map using computational software [27].

Workflow:

Experimental Design & Tracer Selection:

- Tracer: [U-¹³C]-Glucose (all six carbon atoms are ¹³C).

- Culture System: Use controlled bioreactors or ensure careful balancing in shake flasks to maintain steady-state conditions (constant nutrient levels and growth rate) throughout the tracer experiment [27].

System Cultivation and Tracer Feeding:

- Grow cells in standard media until the desired cell density is reached.

- Rapidly switch to an identical medium where the sole carbon source is [U-¹³C]-Glucose.

- Maintain cells in exponential growth for a duration sufficient to achieve isotopic steady state in target metabolites (typically 12-24 hours, depending on cell doubling time).

Metabolite Extraction and Hydrolysis:

- Rapid Quenching: At the end of the experiment, rapidly aspirate the medium and quench cell metabolism immediately by adding cold methanol (-40°C or lower) [33] [29].

- Metabolite Extraction: Use a biphasic solvent system (e.g., methanol/chloroform/water) to extract intracellular metabolites. Polar metabolites partition into the methanol/water phase, while lipids partition into the chloroform phase [33].

- Protein Hydrolysis: Isolate the protein pellet from the extraction. Hydrolyze the protein pellet with 6M HCl at 105°C for 24 hours to liber free amino acids.

- Amino Acid Derivatization: Derivatize the hydrolyzed amino acids for GC-MS analysis (e.g., using MTBSTFA to form tert-butyldimethylsilyl derivatives).

Analytical Measurement via GC-MS:

- Inject the derivatized samples into a GC-MS system.

- GC Separation: Separate the amino acids on a non-polar capillary GC column.

- MS Detection: Use electron impact ionization and operate the MS in selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode to accurately quantify the mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of the amino acid fragments.

Flux Estimation and Sensitivity Analysis:

- Stoichiometric Model: Use a comprehensive stoichiometric model of the central metabolic network.

- Software Tool: Utilize dedicated fluxomics software (e.g., OpenFlux, INCA) [27].

- Iterative Fitting: Input the measured MIDs and external flux rates (e.g., glucose uptake, lactate secretion, growth rate). The software performs an iterative fitting procedure, adjusting the network fluxes until the simulated MIDs match the experimental data, resulting in a statistically validated flux map [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Fluxomics

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ¹³C-Labeled Substrates | Serve as the metabolic tracer; enable tracking of carbon fate. | [U-¹³C]-Glucose, [U-¹³C]-Glutamine. Purity >99% atom ¹³C is critical. |

| Quenching Solvent | Instantly halts enzymatic activity, preserving in vivo metabolic state. | Cold methanol (-40°C to -80°C) [33] [29]. |

| Extraction Solvent | Precipitates proteins and extracts metabolites of interest. | Methanol/Chloroform/Water for biphasic extraction of polar & non-polar metabolites [33]. |

| Internal Standards | Correct for variations in extraction efficiency and instrument response. | ¹³C or ²H-labeled metabolite standards added at the start of extraction [33]. |

| Derivatization Reagent | Chemically modifies metabolites for volatility and detection in GC-MS. | MTBSTFA for amino acid analysis. |

| Cell Culture Bioreactor | Maintains cells in a metabolic steady-state, essential for accurate flux estimation. | Systems that control pH, dissolved O₂, and nutrient feeding. |

The evolution from Schoenheimer's early tracer studies to modern spatial-fluxomics represents a century-long quest to measure the dynamic processes of life. Throughout this journey, the metabolic steady state has remained a cornerstone, providing the necessary foundation for accurate flux quantification. The field has matured by integrating sophisticated analytical technologies like high-resolution mass spectrometry with advanced computational modeling. The recent advent of spatial-fluxomics now allows us to deconvolute metabolic activities at the subcellular level, revealing previously unappreciated pathways and regulatory mechanisms. As new computational paradigms like quantum algorithms emerge, the potential to model and understand metabolic networks at unprecedented scale and speed comes into view. For researchers and drug developers, fluxomics offers a quantifiable representation of the functional metabolic phenotype, providing a powerful lens through which to study health, disease, and therapeutic intervention.

Implementing Steady-State Methods: From 13C-MFA to Advanced Computational Frameworks

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as the premier technique for quantitatively mapping intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells. By integrating stable isotope tracing with sophisticated computational modeling, 13C-MFA provides unparalleled insights into metabolic pathway activities under defined physiological conditions. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, methodologies, and applications of 13C-MFA, with particular emphasis on the critical importance of maintaining and verifying metabolic steady state as the foundational requirement for generating reliable flux quantifications. The protocol detailed herein enables quantification of metabolic fluxes with a standard deviation of ≤2%, representing a significant advancement in precision for the field [34].

The Fundamental Role of Metabolic Fluxes

Metabolic flux refers to the in vivo conversion rate of metabolites, encompassing both enzymatic reaction rates and transport rates between different cellular compartments [35]. These fluxes represent the functional output of the metabolic network, providing a direct link between cellular genotype and phenotype. Precise quantification of metabolic pathway fluxes is of major importance for guiding efforts in metabolic engineering, biotechnology, microbiology, and investigations of human health and disease mechanisms [34].

Evolution of 13C-MFA as the Gold Standard

13C-MFA has evolved into the preferred method for flux quantification due to its ability to resolve fluxes through parallel pathways, metabolic cycles, and reversible reactions – capabilities that distinguish it from alternative approaches like flux balance analysis (FBA) and stoichiometric MFA [36]. Where earlier methods provided only relative flux ratios or constraints, 13C-MFA delivers absolute flux values with defined confidence intervals, enabling rigorous statistical evaluation of flux differences between experimental conditions [35] [36].

Fundamental Principles of 13C-MFA

Theoretical Foundation

The core principle underlying 13C-MFA is that the distribution of 13C atoms in intracellular metabolites is determined by both the pattern of the labeled substrate and the configuration of metabolic fluxes through the network [37]. When cells are fed specifically 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose), the enzymatic rearrangement of carbon atoms through metabolic pathways creates unique isotopic labeling patterns in downstream metabolites [37]. These patterns serve as fingerprints of metabolic pathway activities, which can be decoded through computational modeling to extract quantitative flux information [38].

The Critical Importance of Metabolic Steady State

The validity of 13C-MFA results depends critically on establishing and maintaining a metabolic steady state throughout the labeling experiment. This fundamental requirement encompasses three complementary aspects:

Isotopic Steady State: The isotopic labeling patterns of all intracellular metabolite pools must remain constant over time [35]. This is typically achieved by maintaining cells in constant growth conditions for a duration exceeding five residence times to ensure complete turnover of all metabolic pools [38].

Metabolic Steady State: The metabolic fluxes, metabolite pool sizes, and growth rate must remain constant throughout the experiment [35]. In practice, this is most reliably achieved during exponential growth in batch culture or in chemostat cultures where growth rate is controlled by nutrient availability [38].

Physiological Steady State: The broader physiological state of the cells, including gene expression patterns and proteome composition, must remain stable during the labeling period.

Violations of these steady-state assumptions represent one of the most significant sources of error in 13C-MFA studies and can lead to fundamentally incorrect biological interpretations [36].

Experimental Workflow for 13C-MFA

The standard 13C-MFA workflow comprises five interconnected phases that transform experimental design into validated flux maps [38].

Experimental Design and Tracer Selection

Proper experimental design is paramount for ensuring that fluxes can be estimated with high precision. Tracer selection represents one of the most critical decisions, as different tracers provide variable resolution for different metabolic pathways [34]. While early studies often used single tracers such as [1-13C]glucose, current best practices employ parallel labeling experiments with complementary tracers to maximize flux resolution throughout the metabolic network [39]. For example, comprehensive studies in E. coli have demonstrated that tracers optimal for upper glycolysis (e.g., 75% [1-13C]glucose + 25% [U-13C]glucose) differ from those providing optimal resolution for TCA cycle fluxes (e.g., [4,5,6-13C]glucose) [39]. This complementary approach, termed COMPLETE-MFA, significantly improves both flux precision and observability [39].

Culture Conditions and Steady-State Verification

To establish metabolic and isotopic steady state, cells are cultured for extended periods (typically >5 residence times) in the presence of the labeled tracer [38]. For microbial systems, this is often achieved in controlled bioreactors with careful monitoring of growth parameters, while mammalian cells are typically cultured in exponential growth phase with constant environmental conditions [34] [37]. Multiple samples should be collected over time to verify that metabolic states remain constant throughout the labeling period.

Analytical Techniques for Isotopic Labeling Measurement

The accuracy of 13C-MFA depends fundamentally on precise measurement of isotopic labeling patterns. The most common analytical techniques include:

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): The workhorse technique for 13C-MFA, providing high sensitivity and precision for measuring mass isotopomer distributions of proteinogenic amino acids, glycogen-bound glucose, and RNA-bound ribose [34].

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Particularly valuable for analyzing labile or polar metabolites without derivatization, with excellent separation capabilities for complex metabolite mixtures [38].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Provides positional labeling information without fragmentation, but generally offers lower sensitivity than MS-based techniques [35].

Current best practices often combine multiple analytical approaches to maximize the information obtained from precious biological samples [38].

Computational Framework for Flux Estimation

Mathematical Foundation