Methanol Assimilation in Engineered Yeast: A Comparative Analysis of Pathways for Bioproduction and Biomedical Applications

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of methanol assimilation pathways in engineered yeast, a frontier in sustainable bioproduction.

Methanol Assimilation in Engineered Yeast: A Comparative Analysis of Pathways for Bioproduction and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of methanol assimilation pathways in engineered yeast, a frontier in sustainable bioproduction. We explore the foundational biology of native methylotrophs like Komagataella phaffii and the strategic engineering of non-native hosts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The article details methodological advances in pathway construction, from 'copy and paste' to synthetic design, and addresses critical troubleshooting for toxicity and redox imbalance. By comparing the performance, carbon efficiency, and application potential of pathways like XuMP, RuMP, and the reductive glycine pathway, this analysis serves as a guide for researchers and drug development professionals selecting and optimizing yeast platforms for the production of biofuels, biochemicals, and therapeutic proteins from methanol.

Native Pathways and Synthetic Biology Foundations for Methylotrophy

Methylotrophic yeasts are a specialized group of microorganisms capable of utilizing reduced one-carbon (C1) compounds, such as methanol, as their sole carbon and energy source [1]. This ability has garnered significant research interest for sustainable biomanufacturing, as methanol can be produced renewably from carbon dioxide (CO₂), thus contributing to a circular carbon economy [1] [2]. Among the natural pathways for methanol assimilation, the xylulose monophosphate (XuMP) pathway is the sole cyclic route found in methylotrophic yeasts like Komagataella phaffii (formerly Pichia pastoris) and Ogataea polymorpha (formerly Hansenula polymorpha) [3].

The XuMP pathway is distinct from bacterial methanol assimilation routes and is characterized by its unique compartmentalization within peroxisomes and its key role in enabling high-density growth on methanol [1]. Understanding the mechanism and efficiency of this native pathway is crucial for both leveraging native methylotrophs as cell factories and for engineering synthetic methylotrophy in conventional yeast hosts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae [1] [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the XuMP pathway against other assimilation strategies, detailing its operation, experimental study, and its application in industrial biotechnology.

The Mechanism of the Native XuMP Pathway

The XuMP pathway operates as a cyclic mechanism that assimilates formaldehyde, the central intermediate of methanol metabolism, into central carbon metabolism. Its operation can be divided into several key stages:

Key Enzymatic Steps and Compartmentalization

The pathway begins with the oxidation of methanol to formaldehyde, catalyzed by an alcohol oxidase (AOX). This reaction occurs within peroxisomes and uses molecular oxygen as an electron acceptor, producing hydrogen peroxide as a by-product [1]. Formaldehyde then enters the cyclic assimilation steps of the XuMP pathway, which involves the following core reactions:

- Formaldehyde Fixation: A molecule of formaldehyde is condensed with xylulose 5-phosphate (Xu5P), catalyzed by the enzyme dihydroxyacetone synthase (DAS). This reaction produces glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP) and dihydroxyacetone (DHA).

- Phosphorylation: DHA is phosphorylated by a dihydroxyacetone kinase (DAK) to form dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP).

- Carbon Rearrangement: GAP and DHAP, both three-carbon compounds, enter a series of reactions involving transaldolase and transketolase enzymes within the non-oxidative pentose phosphate pathway. These reactions regenerate the formaldehyde acceptor, Xu5P, and ultimately produce fructose 6-phosphate (F6P), which can exit the cycle to fuel biomass and product formation [4] [1] [3].

A critical feature of the yeast XuMP pathway is its peroxisomal compartmentalization. The initial steps—methanol oxidation and formaldehyde fixation—are sequestered within peroxisomes. This serves as a protective mechanism, shielding the cell from the toxic effects of formaldehyde and reactive oxygen species generated during methanol oxidation [1].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in the Native XuMP Pathway of Methylotrophic Yeast

| Enzyme | Abbreviation | Function in the Pathway | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Oxidase | AOX | Oxidizes methanol to formaldehyde and H₂O₂ | Peroxisome |

| Dihydroxyacetone Synthase | DAS | Condenses formaldehyde with Xu5P to form GAP and DHA | Peroxisome |

| Dihydroxyacetone Kinase | DAK | Phosphorylates DHA to form DHAP | Cytosol |

| Transketolase | TKL | Catalyzes carbon rearrangements in the PPP to regenerate Xu5P | Cytosol |

| Transaldolase | TAL | Catalyzes carbon rearrangements in the PPP to regenerate Xu5P | Cytosol |

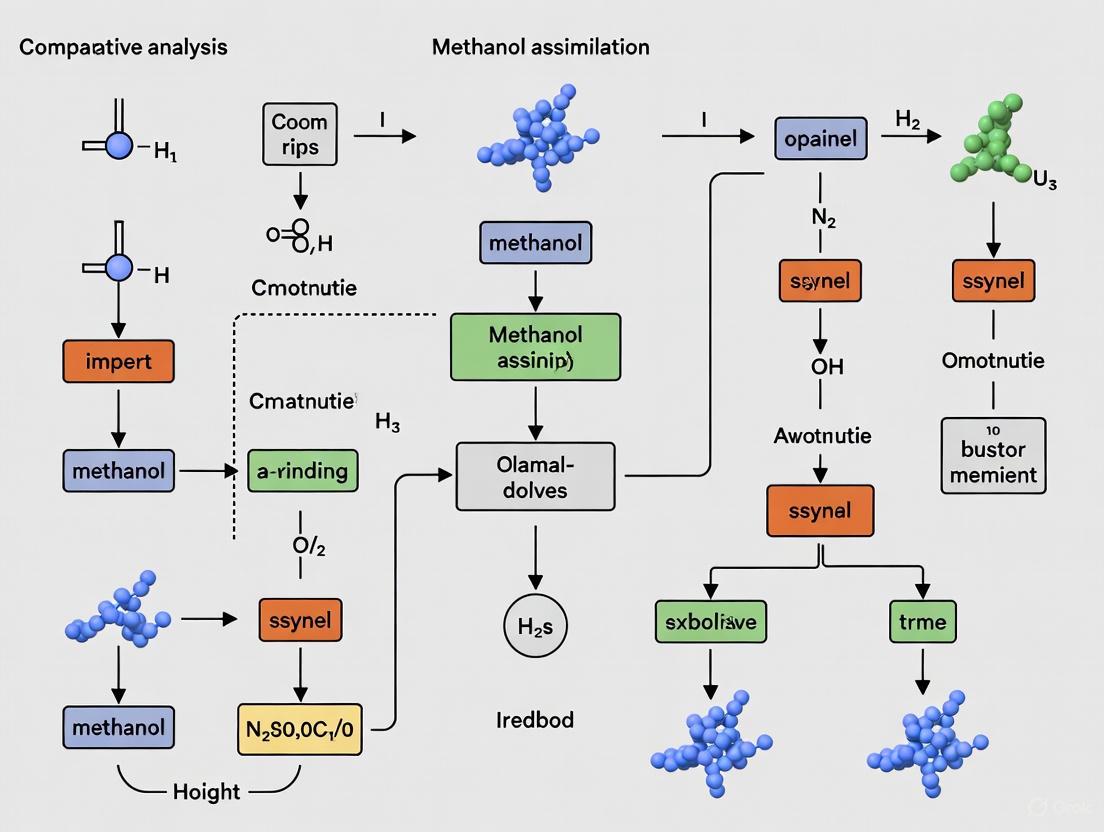

Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the flow of metabolites through the XuMP pathway, highlighting its cyclic nature and key intermediates.

Comparative Analysis of Methanol Assimilation Pathways

While the XuMP pathway is native to yeasts, other natural and synthetic pathways offer different advantages and trade-offs in terms of carbon and energy efficiency. The ribulose monophosphate (RuMP) cycle, native to many methylotrophic bacteria, and the synthetic reductive glycine (rGly) pathway are two key alternatives.

Quantitative Comparison of Pathway Efficiencies

The core difference between these pathways lies in their biochemistry, which directly impacts the ATP requirement and carbon yield for biomass and product formation.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Methanol Assimilation Pathways

| Feature | Native XuMP Pathway (Yeasts) | RuMP Cycle (Bacteria) | Reductive Glycine (rGly) Pathway (Synthetic) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Hosts | Komagataella phaffii, Ogataea polymorpha | Bacillus methanolicus | Engineered E. coli, S. cerevisiae |

| Key Initial Enzyme | Alcohol Oxidase (AOX) | Methanol Dehydrogenase (MDH) | - |

| Formaldehyde Fixation Enzyme | Dihydroxyacetone Synthase (DAS) | 3-Hexulose-6-phosphate Synthase (HPS) | - |

| Energy (ATP) per C3 Unit | 3 ATP [3] | 1 ATP [3] [5] | Higher than RuMP/XuMP [3] |

| Carbon Efficiency | Lower than RuMP due to higher energy cost | Highest among natural pathways [3] [6] | Enables CO₂ co-utilization, reducing carbon loss [7] |

| Compartmentalization | Peroxisomal (detoxification advantage) | Cytosolic | Cytosolic/Mitochondrial |

| Primary Engineering Challenge | Redirecting flux to products [4] | Managing formaldehyde toxicity in non-native hosts [1] | Balancing complex pathway modules and energy demand [7] |

| Suitability for Products | Proteins, organic acids, erythritol [4] [2] | Bulk chemicals, amino acids [6] | Fine chemicals, terpenoids (via mevalonate) [7] |

The RuMP cycle is the most energy-efficient natural pathway, requiring only 1 ATP per glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP) molecule produced, compared to the 3 ATP required by the XuMP pathway [3] [5]. This higher energy cost of the XuMP pathway inherently limits its maximum theoretical carbon yield for biomass and products compared to the RuMP cycle. However, the XuMP pathway's compartmentalization in peroxisomes provides a natural advantage by mitigating formaldehyde toxicity, a significant challenge when engineering the RuMP cycle in non-native hosts [1].

The synthetic reductive glycine pathway (rGly) offers a different value proposition. It is less energy-efficient but provides a linear route for formate and CO₂ assimilation. When integrated with methanol assimilation in engineered S. cerevisiae, it can reassimilate CO₂ lost during metabolism, thereby increasing one-carbon recovery and enabling the co-utilization of methanol and CO₂ for product synthesis [7].

Experimental Analysis of the XuMP Pathway

Studying the XuMP pathway involves a combination of genetic engineering, cultivation techniques, and analytical methods to quantify flux and performance.

Key Experimental Protocols

1. Strain Construction and Cultivation:

- Host Strain: Pichia pastoris (Komagataella phaffii) GS115 is a commonly used background strain [4].

- Cultivation Media: Cells are typically cultivated in defined minimal media with methanol as the sole carbon source. A standard protocol involves growing cells in shake flasks or bioreactors with media containing (per liter): 1-3% (v/v) methanol, 1.34% Yeast Nitrogen Base (YNB), and 4 × 10⁻⁵% biotin [4]. Bioreactors allow for better control of dissolved oxygen and pH, which is critical for high-density cultivations.

- Induction: The expression of genes in the XuMP pathway, such as AOX1 and DAS, is strongly induced by methanol. For experimental strains, this is achieved by shifting the carbon source from glycerol or glucose to methanol [4] [1].

2. Quantifying Methanol Utilization and Pathway Flux:

- Methanol Consumption: Methanol concentration in the culture broth can be tracked over time using gas chromatography (GC) or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [4].

- ¹³C-Tracer Analysis: This is a crucial technique for confirming and quantifying carbon flux through the XuMP pathway. Cells are fed with ¹³C-labeled methanol (e.g., ¹³CH₃OH). The incorporation of the ¹³C label into central metabolites like fructose-6-phosphate, erythrose-4-phosphate, and nucleic acid ribose is then analyzed using LC-MS or GC-MS. The specific labeling patterns confirm active cycling of the XuMP pathway [4] [6].

- Gene Expression Analysis: Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) can be used to measure the transcript levels of key XuMP pathway genes (e.g., AOX1, DAS1, DAK) under different conditions, using the 2−ΔΔCT method for analysis [4].

3. Measuring Product Formation:

- For strains engineered to produce chemicals like erythritol, product titers, yields, and productivities are determined. Extracellular metabolites are quantified using HPLC. Intracellular metabolite pools can be quantified via LC-MS/MS [4].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

A typical experimental workflow for analyzing and engineering the XuMP pathway is structured as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Working with the XuMP pathway requires a specific set of biological and chemical reagents. The following table details essential materials and their applications.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for XuMP Pathway Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Komagataella phaffii GS115 | A standard auxotrophic background strain for genetic engineering. | Serves as the base host for knocking out genes or integrating expression cassettes [4]. |

| Methanol-Inducible Promoters (e.g., P_AOX1) | Drives strong, methanol-specific expression of heterologous genes. | Used to control the expression of pathway enzymes in engineered constructs [1]. |

| Yeast Nitrogen Base (YNB) | Essential components for defined minimal media. | Used in cultivation media to support growth with methanol as the sole carbon source [4]. |

| ¹³C-Labeled Methanol (¹³CH₃OH) | Tracer for tracking carbon fate through the XuMP pathway. | Fed to cultures to quantify metabolic flux and confirm pathway activity via MS analysis [4] [6]. |

| Alcohol Oxidase (AOX) Antibody | Detects and quantifies AOX protein levels. | Used in Western blotting to confirm successful protein expression and induction by methanol. |

| Shikimic Acid & Aromatic Amino Acids | Supplements for E4P auxotrophic strains. | Allows for the growth of engineered strains with blocked native metabolism in experimental setups [5]. |

The native XuMP pathway in methylotrophic yeast represents a sophisticated, compartmentalized system for methanol assimilation. While its higher ATP cost makes it inherently less carbon-efficient than the bacterial RuMP cycle, its natural detoxification capability and the well-developed industrial fermentation processes for yeasts like K. phaffii make it a highly viable platform for bioproduction [4] [2]. Current research successfully leverages this pathway to produce gram-to-deciliter quantities of chemicals, including organic acids and sugar alcohols like erythritol [4].

The future of the XuMP pathway lies in sophisticated metabolic engineering to overcome its limitations. As demonstrated in recent studies, strategies such as rewiring the pathway to create hybrid XuMP/RuMP cycles or integrating it with CO₂-recapturing pathways like the reductive glycine pathway are promising avenues to enhance carbon efficiency and product yield [4] [7]. The choice between using a native methylotroph with the XuMP pathway or engineering a synthetic methylotroph with an alternative pathway ultimately depends on the target product, required yield, and the trade-offs between energy efficiency, toxicity management, and the availability of genetic tools.

In the pursuit of a sustainable bioeconomy, methanol has emerged as a promising alternative feedstock to traditional sugar-based sources for biomanufacturing. This shift is driven by methanol's potential to be produced renewably from biomass or CO₂ hydrogenation, offering a path to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and arable land [2]. Central to the microbial metabolism of methanol is the intermediate formaldehyde, a highly cytotoxic compound that poses a significant challenge for efficient bioconversion. In methylotrophic yeast species like Pichia pastoris (Komagataella phaffii), the dissimilation pathway serves a critical dual role: it functions as a primary mechanism for formaldehyde detoxification while simultaneously generating energy for cellular processes [8] [9]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the dissimilation pathway's function across engineered yeast platforms, supported by experimental data on its indispensability for growth on methanol.

Core Pathways of Methanol Metabolism and Formaldehyde Detoxification

In methylotrophic yeasts, methanol metabolism begins with its oxidation to formaldehyde, which resides at a critical metabolic branch point.

Figure 1. Formaldehyde Metabolism Pathways in Methylotrophic Yeast. Formaldehyde, produced from methanol oxidation by alcohol oxidase (AOX), is processed through either the dissimilation pathway for energy production and detoxification or the assimilation pathway for biomass formation. The dissimilation pathway consists of formaldehyde dehydrogenase (FLD), S-hydroxymethyl glutathione hydrolase (FGH), and formate dehydrogenase (FDH). The assimilation pathway involves condensation with xylulose-5-phosphate by dihydroxyacetone synthase (DAS) to produce glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP). Adapted from [8] [9].

The Critical Role of the Dissimilation Pathway

The dissimilation pathway is essential for managing formaldehyde toxicity. This pathway consists of three key enzymatic steps that oxidize formaldehyde to carbon dioxide, generating reducing equivalents in the process [9]:

- Formaldehyde Dehydrogenase (FLD): Catalyzes the NAD+-dependent oxidation of formaldehyde, captured by glutathione, to S-hydroxymethyl glutathione.

- S-hydroxymethyl Glutathione Hydrolase (FGH): Hydrolyzes S-hydroxymethyl glutathione to formate and glutathione.

- Formate Dehydrogenase (FDH): Oxidizes formate to CO₂, producing a second molecule of NADH.

This pathway is speculated to have two primary physiological functions: formaldehyde detoxification and energy production [9]. The generated NADH can be used for ATP synthesis via oxidative phosphorylation, which is crucial for supporting cellular metabolism during growth on methanol.

Comparative Analysis of Dissimilation Pathway Disruption

To quantitatively assess the functional importance of the dissimilation pathway, researchers have constructed knockout strains of Pichia pastoris lacking key enzymes.

Table 1: Phenotypic Effects of Dissimilation Pathway Gene Knockouts inPichia pastoris

| Gene Knocked Out | Enzyme Disrupted | Biomass Reduction vs. Wild-Type (%) | Key Observed Phenotypes on Methanol |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLD | Formaldehyde Dehydrogenase | 60.98% [9] | Severe growth defect; poor growth on 4% methanol plates [9] |

| FGH | S-hydroxymethyl Glutathione Hydrolase | 23.66% [9] | Reduced growth; poor growth on 4% methanol plates [9] |

| FDH | Formate Dehydrogenase | 5.69% [9] | Minimal growth defect; slightly slower methanol consumption [9] [10] |

Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Profiling of Knockout Strains

Comparative transcriptome analysis of ∆fld, ∆fgh, and ∆fdh strains versus the wild-type (GS115) reveals the systemic impact of disrupting the dissimilation pathway [9].

Table 2: Transcriptomic Changes inP. pastorisDissimilation Pathway Knockout Strains

| Comparison Group | Number of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) | Significantly Downregulated Pathways | Significantly Upregulated Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GS115 vs. ∆fld | 938 Up, 1072 Down [9] | Oxidative Phosphorylation, Glycolysis, TCA Cycle [9] | Alcohol Metabolism, Proteasomes, Autophagy, Peroxisomes [9] |

| GS115 vs. ∆fgh | 943 Up, 587 Down [9] | Oxidative Phosphorylation, Glycolysis, TCA Cycle [9] | Alcohol Metabolism, Proteasomes, Autophagy, Peroxisomes [9] |

| GS115 vs. ∆fdh | 281 Up, 310 Down [9] | Downregulation correlated with knockout order [9] | Stress response pathways [9] |

The data demonstrates that the severity of the transcriptional response is directly correlated with the position of the knocked-out enzyme in the dissimilation pathway, with FLD knockout causing the most profound disruption [9]. The consistent downregulation of oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis, and the TCA cycle indicates a severe energy deficit in the knockout strains, particularly in ∆fld. The upregulation of the proteasome and autophagy is likely a stress response to resolve formaldehyde-induced DNA-protein crosslinking (DPC) [9].

Experimental Protocols for Dissimilation Pathway Analysis

This section outlines key methodologies used to generate the comparative data presented in this guide.

Protocol: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Knockout inP. pastoris

This protocol was used to generate the knockout strains discussed in Section 2 [9].

- Strain and Culture Conditions: Use P. pastoris GS115 as the background strain. Maintain cultures in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) at 30°C.

- gRNA Design and Vector Construction: Design guide RNA (gRNA) sequences targeting the genes of interest (FLD: PASchr31028, FGH: PASchr30867, FDH: PASchr30932). Clone the gRNA expression cassettes and a Cas9 expression cassette into a suitable P. pastoris integration vector.

- Transformation: Transform the constructed plasmid into competent GS115 cells using electroporation.

- Screening and Validation: Screen for successful transformants on appropriate selective media. Validate gene knockout by analytical PCR and DNA sequencing.

Protocol: Phenotypic Analysis of Knockout Strains

This protocol describes the methods for assessing the growth and metabolic phenotypes of the knockout strains [9].

- Culture Conditions: Inoculate wild-type and knockout strains in minimal media with 0.1% yeast extract and 2% methanol as the sole carbon source.

- Biomass Measurement: Monitor cell growth by measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) over 12-24 hours. Calculate the maximum OD and specific growth rate.

- Spot Assay for Methanol Tolerance: Prepare serial dilutions of cultures and spot them onto YPM plates (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 4% methanol). Incubate at 30°C for 2-3 days and document growth differences.

Protocol: Comparative Transcriptomics Workflow

This workflow was used to analyze the global transcriptional changes in response to dissimilation pathway disruption [9].

Figure 2. Transcriptomic Analysis Workflow. The process for comparing gene expression profiles between dissimilation pathway knockout strains and the wild-type P. pastoris [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This section catalogs essential materials and solutions used in the cited experiments for studying formaldehyde dissimilation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Formaldehyde Dissimilation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| P. pastoris GS115 | Wild-type methylotrophic yeast strain; background for genetic engineering. | Chemostat competent cells; His- phenotype for selection [9]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Targeted gene knockout for dissimilation pathway genes (FLD, FGH, FDH). | Plasmid-based system for P. pastoris with gRNA expression cassette [9]. |

| Methanol (HPLC/GC Grade) | Primary carbon source for cultivating methylotrophic yeast; inducer of methanol utilization pathways. | Use at 2% (v/v) for shake flask cultures; 4% for tolerance plates [9]. |

| YPM Medium | Selective medium for growth assays on methanol. | 1% Yeast Extract, 2% Peptone, 4% Methanol [9]. |

| RNA Sequencing Kit | For transcriptome analysis of knockout strains vs. wild-type. | Illumina platform for high-throughput sequencing [9]. |

| NAD+ Cofactor | Essential cofactor for FLD and FDH enzyme activity in the dissimilation pathway. | Critical for in vitro enzyme activity assays. |

| Glutathione | Tripeptide that non-enzymatically binds formaldehyde, forming the substrate for FLD. | Key to the glutathione-dependent formaldehyde detoxification mechanism [9] [10]. |

The dissimilation pathway is not merely an alternative route for carbon flux in methanol-based metabolism; it is an indispensable detoxification and energy-generating system in methylotrophic yeasts. Experimental evidence from gene knockout studies unequivocally demonstrates that disruption of this pathway, particularly the first enzyme FLD, leads to severe growth defects, transcriptional reprogramming, and energy deficiency. The critical balance between formaldehyde assimilation for biomass production and its dissimilation for detoxification and energy must be carefully managed in any engineering strategy aimed at leveraging methylotrophic yeasts for the bioproduction of valuable chemicals. Future efforts to engineer more efficient microbial cell factories on methanol must account for and optimize this essential pathway.

The transition toward a sustainable bioeconomy necessitates a shift from traditional sugar-based feedstocks to alternative, renewable carbon sources. One-carbon (C1) compounds, such as methanol, have emerged as promising substrates for microbial bioproduction, as they can be produced from organic wastes, natural gas, or via CO2 hydrogenation, thereby supporting a circular carbon economy [11] [12]. Methanol is particularly attractive due to its liquid state, compatibility with existing infrastructure, and high energy content [13] [11]. Native methylotrophic organisms possess natural pathways for methanol assimilation, such as the ribulose monophosphate (RuMP) cycle and the serine cycle. However, these organisms often lack the advanced genetic tools and metabolic plasticity required for efficient bioproduction [14] [11]. Consequently, metabolic engineering of model heterotrophic organisms like Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Pseudomonas putida to become synthetic methylotrophs has become a major focus in synthetic biology [6] [15] [16].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the RuMP and serine cycle pathways, detailing their implementation in various bacterial hosts. It summarizes key experimental data, outlines foundational protocols, and visualizes the core metabolic routes, offering researchers a resource for selecting and engineering C1 assimilation pathways.

Pathway Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

The RuMP and serine cycles represent two distinct biological strategies for assimilating methanol-derived carbon into biomass and valuable biochemicals. Their core characteristics, advantages, and challenges are summarized below.

The Ribulose Monophosphate (RuMP) Cycle: This pathway is recognized for its high energy efficiency and rapid kinetics, making it prevalent among fast-growing methylotrophic bacteria [6] [14]. It primarily assimilates formaldehyde, a direct oxidation product of methanol. The cycle involves a fixation phase, where formaldehyde is condensed with ribulose-5-phosphate to form hexose-6-phosphates, followed by cleavage and rearrangement to produce central metabolic intermediates like glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) and acetyl-CoA. A key advantage is its minimal energy requirement, consuming only one ATP per G3P produced, and it can even generate net ATP and NADH when configured for acetyl-CoA production [14]. However, when G3P is converted to acetyl-CoA via pyruvate dehydrogenase, one-third of the carbon is lost as CO2, limiting the theoretical carbon yield of acetyl-CoA-derived products [14] [12].

The Serine Cycle: This pathway is distinguished by its high carbon conservation, enabling the synthesis of acetyl-CoA without carbon loss [14] [12]. It concurrently assimilates formaldehyde (via methylene-H4F) and CO2. The cycle utilizes phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxylase and serine hydroxymethyltransferase to fix bicarbonate and a C1 unit, respectively, ultimately generating glyoxylate. Glyoxylate is then condensed with a second C1 unit to form glycine and subsequently serine, leading to the regeneration of PEP and the output of acetyl-CoA. The main drawback of the native serine cycle is its high energy demand, requiring three ATP and three NAD(P)H to produce one acetyl-CoA from one formate and one bicarbonate [14] [12].

The table below provides a direct comparison of these two core pathways based on thermodynamic, stoichiometric, and performance metrics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of the RuMP Cycle and Serine Cycle

| Feature | RuMP Cycle | Serine Cycle |

|---|---|---|

| Primary C1 Substrate | Formaldehyde | Formaldehyde (as methylene-H4F) & CO2/Bicarbonate |

| Key Product | G3P, Acetyl-CoA (with CO2 loss) | Acetyl-CoA (no carbon loss) |

| Theoretical Carbon Yield for Acetyl-CoA | Lower (2/3 from methanol) [12] | Higher (100% from methanol + CO2) [12] |

| Energy Consumption (per Acetyl-CoA) | Can produce net ATP/NADH [14] | 3 ATP, 3 NAD(P)H [12] |

| In Vivo Doubling Time (Engineered Hosts) | ~4.5 h (E. coli) [6], ~8.5 h (E. coli) [14] | Data less available; generally slower growth [14] |

| Thermodynamic Driving Force (MDF) | 6.12 kJ mol−1 (for a synthetic variant) [6] | Not explicitly quantified in results |

| Common Engineering Hosts | E. coli, B. methanolicus, P. thermoglucosidasius [6] [14] [17] | M. extorquens, E. coli, P. putida [15] [14] [12] |

Key Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Recent engineering breakthroughs have demonstrated the feasibility of both pathways in non-native hosts, with performance data providing critical insights for pathway selection. The following table synthesizes key quantitative results from seminal studies.

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Performance Metrics in Engineered Strains

| Host Organism | Pathway | Key Engineering Strategy | Methanol Assimilation / Growth Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Synthetic Methanol Assimilation (SMA) pathway (RuMP-based) | Rational design & ALE; Alleviated Transcription-Replication Conflicts (TRCs) | Doubling time: 4.5 h (approaching natural methylotrophs) [6] | [6] |

| E. coli | RuMP Cycle | Introduction of HPS & PHI and ALE | Doubling time: 8.5 h on sole methanol [14] | [14] |

| E. coli | Modified Serine Cycle | Implemented cycle for co-utilization; produced ethanol from methanol/CO2 | Conversion of methanol to ethanol demonstrated [12] | [12] |

| S. cerevisiae | Native Capacity & ASrG Pathway | ALE & SCRaMbLE; discovery of endogenous Adh2-Sfa1-rGly (ASrG) pathway | Doubling time: 58.18 h on sole methanol [13] | [13] |

| M. extorquens | Synergistic RuMP + Native Serine | Introduced RuMP cycle (HPS/PHI) to synergize with native serine cycle | ~50% increase in growth rate; 2.5-fold higher 3-HP production [14] | [14] |

| P. thermoglucosidasius | Native RuMP Cycle | ALE to awaken latent native enzyme activity for RuMP core | ~17% of biomass strictly from methanol (partial methylotrophy) [17] | [17] |

Visualizing Core Metabolic Pathways

The DOT language scripts below define the structure and flow of the primary methanol assimilation pathways. Rendering these scripts will produce clear diagrams illustrating the metabolic routes and their key intermediates.

The Ribulose Monophosphate (RuMP) Cycle

Diagram Title: RuMP Cycle Simplified Pathway

The Serine Cycle

Diagram Title: Serine Cycle Simplified Pathway

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues critical enzymes, genetic tools, and experimental strains commonly employed in constructing and optimizing methanol assimilation pathways in bacterial hosts.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Engineering Methylotrophy

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol Dehydrogenase (MDH) | Oxidizes methanol to formaldehyde, the entry point for assimilation. | CnMDH variant CT4-1 [6]; Native AdhT in P. thermoglucosidasius [17]. |

| RuMP Cycle Core Enzymes | Catalyze formaldehyde fixation and sugar phosphate rearrangement. | Hexulose-6-phosphate synthase (HPS) & Phospho-3-hexuloisomerase (PHI) [14]; Fructose-5-phosphate phosphoketolase (FPK) [6]. |

| Serine Cycle Core Enzymes | Enable the condensation of C1 and C2 units and subsequent rearrangements. | Serine-glyoxylate transaminase (SgaA); Serine hydroxymethyltransferase (GlyA); Malyl-CoA lyase (Mcl) [14] [12]. |

| Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) | Uncover adaptive mutations and improve growth on methanol without prior knowledge of all constraints. | Used in E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and P. thermoglucosidasius to achieve significantly reduced doubling times [6] [13] [17]. |

| Genome-Scale Modeling (FBA) | Predicts theoretical growth rates and identifies metabolic bottlenecks in silico. | Used to validate the synergistic effect of adding the RuMP cycle to M. extorquens [14]. |

| Methanol-Utilization Deficient Models | Serve as platform strains for selecting functional pathway variants. | ΔadhP Δrpe P. thermoglucosidasius [17]; M. extorquens models for HPS/PHI screening [14]. |

Foundational Experimental Protocols

This section outlines two critical, widely-used methodologies for developing and analyzing synthetic methylotrophs.

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) for Enhanced Methylotrophy

Objective: To improve a host organism's growth rate and methanol assimilation capability through selective pressure over multiple generations.

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Start with a base strain engineered with a heterologous methanol assimilation pathway (e.g., RuMP or serine cycle).

- Evolution Media: Grow the strain in serial batch cultures or chemostats using a minimal medium with methanol as the sole or primary carbon source. A low concentration of a co-substrate (e.g., 0.1% yeast extract) may be included initially to boost cell density and mutation rates [13] [11].

- Passaging: Regularly transfer a small aliquot of the culture into fresh methanol medium during the mid-exponential or early stationary phase. This process is repeated for dozens to hundreds of generations.

- Monitoring: Track culture optical density (OD600) and methanol concentration over time. The evolution is typically considered successful when a significant reduction in doubling time and an increase in final biomass are observed.

- Isolation and Screening: Plate the evolved population to isolate single colonies. Screen these clones for improved growth in methanol minimal medium.

- Genomic Analysis: Sequence the genomes of the best-performing evolved clones to identify causative mutations (e.g., mutations in topoisomerase I to alleviate TRCs [6] or truncations of transcriptional regulators like Ygr067cp [11]).

13C-Methanol Tracer Analysis for Pathway Validation

Objective: To confirm the in vivo activity of a methanol assimilation pathway and quantify carbon flux.

Procedure:

- Cultivation: Grow the engineered strain in a bioreactor or controlled system with a minimal medium where the sole carbon source is 13C-labeled methanol.

- Sampling: Harvest cells at mid-exponential phase and quench metabolism rapidly (e.g., using cold methanol).

- Metabolite Extraction: Perform intracellular metabolite extraction using appropriate solvent systems (e.g., methanol:water:chloroform).

- LC-MS Analysis: Analyze the extracted metabolites via Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS).

- Data Interpretation: Determine the mass isotopomer distribution of central carbon metabolites (e.g., F6P, acetyl-CoA, amino acids). The detection of 13C-labeled fragments and fully labeled metabolites provides direct evidence of methanol incorporation into biomass [6] [11]. For example, the presence of 13C-fructose-1,6-bisphosphate or fully 13C-labeled acetyl-CoA confirms functional assimilation [11].

The pursuit of sustainable biomanufacturing has intensified the focus on one-carbon (C1) compounds as alternative feedstocks. While engineered synthetic methylotrophy in model microbes often dominates discussions, recent research has uncovered a paradigm-shifting discovery: the innate capacity of the industrial yeast Komagataella phaffii to co-assimilate methanol, formate, and CO₂ via an oxygen-tolerant reductive glycine pathway (rGlyP). This comparative analysis examines the performance of this native pathway against other established and engineered C1-assimilation systems in yeast, providing a robust framework for evaluating its potential in renewable bioproduction.

The transition from sugar-based feedstocks to C1 substrates (methanol, formate, CO₂) represents a cornerstone of sustainable biotechnology. Methylotrophic yeasts like Komagataella phaffii natively possess the xylulose 5-phosphate pathway (XuMP) for methanol assimilation [18] [3]. However, the discovery of a previously overlooked native pathway—the oxygen-tolerant reductive glycine pathway—fundamentally alters our understanding of C1 metabolism in eukaryotes [18] [19]. This pathway operates concurrently with XuMP and enables simultaneous fixation of methanol, formate, and CO₂, a unique capability absent in most engineered systems. This guide provides a comparative analysis of this newly characterized pathway against other native and engineered C1-assimilation strategies in yeast, evaluating performance metrics, experimental validation, and industrial relevance.

Comparative Analysis of C1 Assimilation Pathways in Yeast

Table 1: Performance comparison of C1 assimilation pathways in yeasts

| Host Organism | Pathway | C1 Substrates | Maximum Growth Rate (h⁻¹) | Biomass Yield | Key Engineering Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Komagataella phaffii | Native oxygen-tolerant rGlyP | Methanol, Formate, CO₂ | 0.002 [3] | Limited data | Minimal (native pathway enhancement) [18] |

| Komagataella phaffii | Native XuMP | Methanol | ~0.14 [9] | High | None (native pathway) |

| Komagataella phaffii | Synthetic CBB cycle | CO₂ (with methanol energy) | 0.018 (evolved) [3] | Limited data | Extensive (heterologous expression) [3] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Engineered rGlyP | Formate, CO₂ | ~0.1 (with glucose) [3] | Limited data | Extensive (native enzyme overexpression) [20] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Native methylotrophy (evolved) | Methanol | Limited data | Limited data | Adaptive laboratory evolution [11] |

Table 2: Quantitative 13C-labeling data from rGlyP validation in K. phaffii XuMP knockout strain [18]

| Metabolite | M+0 Fraction (2h) | M+0 Fraction (24h) | M+0 Fraction (72h) | Key Isotopologue Observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serine | ~92% | ~84% | ~78% | M+2 (indicating two labeled carbons) |

| Methionine | ~92% | ~85% | ~80% | M+0 decrease demonstrates C1 incorporation |

| Glycine | ~98% | ~95% | ~90% | M+1 (single labeled carbon) |

| Aspartate Backbone | ~95% | ~90% | ~85% | M+0 decrease confirms pathway activity |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Discovery and Validation

13C-Tracer-Based Metabolomics

Objective: To identify and quantify carbon flux through the reductive glycine pathway in Komagataella phaffii.

Methodology:

- Strain Preparation: Utilize a XuMP pathway knockout strain (das1Δdas2Δ) to eliminate conventional methanol assimilation [18].

- Isotope Labeling: Cultivate strains in minimal medium with 13C-methanol as the sole carbon source.

- Sampling: Collect samples at multiple time points (2h, 24h, 72h) to track temporal label incorporation [18].

- Metabolite Analysis: Employ GC-TOFMS for precise measurement of isotopologue distributions in central carbon metabolites [18].

- Data Interpretation: Monitor decreases in unlabeled (M+0) fractions and increases in specific labeled isotopologues (e.g., M+1, M+2) to trace carbon fate.

Key Findings: Methionine and serine showed the strongest and fastest decrease in M+0 fraction (6-8% after 2h), with serine displaying significant M+2 enrichment, confirming the incorporation of two C1 units via methylene-THF and CO₂ [18].

Metabolic Engineering for Pathway Activation

Objective: To enhance native rGlyP flux to growth-supporting levels through targeted genetic modifications.

Methodology:

- Gene Identification: Identify native enzymes comprising the oxygen-tolerant rGlyP: formate-THF ligase, methylene-THF dehydrogenase, glycine cleavage/synthase system (GCS), and serine hydroxymethyltransferase [18].

- Competition Relief: Delete mitochondrial serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHM1) to reduce competition for methylene-THF, redirecting flux toward glycine synthesis via GCS [18].

- Functional Validation: Test engineered strains on formate or methanol as sole carbon sources with CO₂ supplementation.

- Physiological Assessment: Measure growth rates, biomass accumulation, and additional 13C-tracer analysis to quantify flux improvements.

Key Findings: SHM1 deletion enabled growth on methanol or formate with CO₂, confirming the rGlyP could support cell division when competing reactions were minimized [18].

Pathway Architecture and Metabolic Context

Diagram 1: The oxygen-tolerant reductive glycine pathway in K. phaffii. This native pathway enables concurrent assimilation of methanol, formate, and CO₂ through tetrahydrofolate (THF)-mediated C1 activation and the glycine cleavage system operating in reverse.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key research reagents for investigating C1 assimilation pathways

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Strain Backgrounds | Komagataella phaffii XuMP knockout (das1Δdas2Δ) [18] | Eliminates major methanol assimilation route to reveal alternative pathways |

| Isotopic Tracers | 13C-methanol, 13C-formate, 13C-bicarbonate [18] [20] | Enables precise carbon flux mapping through metabolomics |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-TOFMS, LC-MS [18] [11] | Quantifies isotopologue distributions in intracellular metabolites |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 for gene knockout (e.g., SHM1) [18] | Modifies metabolic network to enhance pathway flux |

| Culture Conditions | High CO2 (e.g., 10%) atmosphere [20] | Thermodynamically drives reversible GCS toward carbon fixation |

Discussion and Comparative Outlook

The discovery of the native oxygen-tolerant rGlyP in K. phaffii represents a significant advancement in C1 metabolism, offering distinct advantages and limitations compared to other assimilation strategies.

Native rGlyP Advantages: This pathway's capacity for concurrent methanol, formate, and CO₂ assimilation is unique among known yeast pathways [18] [19]. Its oxygen tolerance differentiates it from the bacterial reductive glycine pathway and makes it compatible with industrial aerobic fermentation [18]. Furthermore, as a native pathway, it requires minimal heterologous expression compared to fully synthetic pathways like the CBB cycle, potentially reducing metabolic burden.

Performance Limitations: The native rGlyP in K. phaffii currently supports only minimal growth (µ_max = 0.002 h⁻¹) without engineering, significantly slower than the native XuMP pathway [3]. This flux constraint likely reflects natural competition for intermediates and regulatory limitations rather than catalytic incapacity.

Engineering Potential: The successful growth restoration via SHM1 deletion demonstrates the pathway's latent capacity [18]. This suggests substantial headroom for improvement through similar targeted interventions, possibly combining metabolic engineering with adaptive laboratory evolution, as successfully applied to S. cerevisiae [11].

When contextualized within the broader C1 metabolic landscape, the native rGlyP offers a promising foundation for developing polytrophic yeast platforms capable of utilizing diverse C1 feedstocks, potentially exceeding the carbon efficiency of pathways like the CBB cycle, as demonstrated in bacterial systems [21].

The oxygen-tolerant reductive glycine pathway in Komagataella phaffii represents a native, multi-substrate C1 assimilation system with unique potential for sustainable bioprocesses. While its native flux is limited, strategic metabolic engineering can unlock growth-supporting assimilation of methanol, formate, and CO₂. This pathway provides a promising alternative to both native XuMP and fully synthetic assimilation routes, particularly for applications requiring mixed C1 feedstock utilization or CO₂ incorporation. Future efforts should focus on optimizing flux through this pathway via enzyme engineering, regulatory manipulation, and integration with production pathways for value-added chemicals.

Engineering Strategies and Bioproduction Applications in Yeast Chassis

The engineering of non-native metabolic pathways into yeast represents a cornerstone of synthetic biology, enabling the conversion of simple substrates into valuable biofuels and chemicals. Within this field, two distinct strategies for pathway construction have emerged: the 'Copy and Paste' approach, which involves the direct transplantation of complete, natural pathways from donor organisms, and the 'Mix and Match' approach, which entails the careful assembly of individual, optimized genetic elements from diverse sources to create a novel, synthetic pathway. The choice between these strategies is critically important when engineering challenging metabolic traits, such as methanol assimilation, which allows yeast to utilize this simple one-carbon (C1) compound as a carbon source. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two approaches, focusing on their application in constructing methanol utilization pathways in yeasts like S. cerevisiae and P. pastoris, to inform researchers and scientists in their experimental design.

Core Concept Comparison

The table below summarizes the fundamental distinctions between the two pathway transplantation strategies.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of 'Copy and Paste' vs. 'Mix and Match' Approaches

| Feature | 'Copy and Paste' Approach | 'Mix and Match' Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Direct, wholesale transfer of an evolved, natural pathway from a donor organism. | De novo construction of a pathway using standardized, optimized parts from various sources. |

| Key Advantage | Leverages biological efficiency and known functionality of a complete, native system. | Offers flexibility to bypass native regulation, optimize flux, and create novel functionalities. |

| Typical Workflow | Identify pathway in donor → Amplify gene cluster → Express in host. | Design pathway → Select parts (promoters, genes, terminators) → Assemble in host. |

| Host Context Compatibility | Can be low; the pre-evolved pathway may not integrate well with the host's native metabolism. | Potentially high; parts can be chosen and tuned for specific host compatibility and expression. |

| Representative Example | Introducing the entire P. pastoris methanol utilization pathway into S. cerevisiae [13] [22]. | Assembling the synthetic Methanol and Formate Oxidation-Reductive Glycine (MFORG) pathway [22]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

Experimental data from recent studies provide a direct comparison of the performance achievable with each strategy. The following tables summarize key outcomes related to growth and pathway efficiency.

Table 2: Comparison of Growth Performance on Methanol

| Yeast Host | Pathway Strategy | Specific Pathway | Key Growth Performance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae | 'Copy and Paste' | Native P. pastoris XuMP pathway | Limited growth; reliance on co-substrates [13]. | [13] |

| S. cerevisiae SCSA001 | 'Mix and Match' + Evolution | Novel ASrG pathway (via evolution) | Sustained growth on sole methanol; μmax = 0.0153 h⁻¹ [13]. | [13] |

| P. pastoris | 'Mix and Match' | Synthetic MFORG pathway | Enabled co-utilization of methanol and CO₂ [22]. | [22] |

Table 3: Pathway Efficiency and Metabolite Production

| Host & Pathway | Methanol Uptake/Conversion | Product Synthesis | Isotope Tracing Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'Copy and Paste' | Often incomplete, can lead to toxic intermediate (formaldehyde) accumulation [13]. | Limited, as carbon is not fully directed toward biomass/ products [13]. | Not specifically provided in search results. |

| 'Mix and Match' (MFORG) | Designed for concurrent assimilation of methanol and CO₂, converting them to central metabolites [22]. | Demonstrated production of 5-aminolevulinic acid and lactic acid from methanol and CO₂ [22]. | 29.00% ¹³C enrichment in glycine (highest); 11.11% in glutamic acid (lowest) in evolved strain [13]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, this section outlines the core methodologies used to generate the data discussed in this guide.

Protocol for 'Copy and Paste' Pathway Transplantation

This protocol describes the foundational steps for transferring the native methanol assimilation pathway from P. pastoris into a model yeast like S. cerevisiae.

- Pathway Identification and Gene Clustering: Identify the key genes of the xylulose monophosphate (XuMP) cycle in P. pastoris, including methanol oxidase (MOX), dihydroxyacetone synthase (DAS), and other required enzymes.

- Vector Construction: Use classic restriction-ligation or advanced cloning methods like Yeast Recombination-Based Cloning (YRBC) [23] to assemble the complete set of genes into a yeast expression vector. YRBC is particularly efficient as it uses homologous recombination in S. cerevisiae to assemble multiple DNA fragments with 30 bp overlaps in a single step, without reliance on restriction sites [23].

- Host Transformation: Introduce the constructed vector into the target S. cerevisiae host strain using standard transformation techniques such as the lithium acetate method.

- Functional Screening: Screen transformants for the ability to grow on minimal medium with methanol as the sole carbon source. This is often coupled with analytical methods like HPLC to confirm methanol consumption.

Protocol for a 'Mix and Match' Pathway Assembly

This protocol details the construction and optimization of a synthetic pathway, such as the MFORG pathway, designed for co-utilizing methanol and CO₂ [22].

- Pathway Design and Module Definition: Design a synthetic pathway. For the MFORG pathway, this consists of:

- Methanol Oxidation Module: ADH2 and SFA1 from S. cerevisiae for methanol oxidation to formaldehyde and then to formate [13].

- Formate Oxidation Module: FDH for formate oxidation to CO₂.

- CO₂ Fixation Module: The reductive glycine (rGly) pathway genes (GCVT1, SHMT1, etc.) for assimilation of CO₂ and formate into central metabolism [22].

- Part Selection and Optimization: Select strong, regulated promoters and terminators for each gene. Studies in Ogataea polymorpha have shown that pairing different promoters and terminators can lead to a 6-fold difference in gene expression. For instance, the MOX terminator was found to boost expression by stabilizing mRNA [24].

- Combinatorial Assembly and Compartmentalization: Assemble the genetic constructs using the YRBC method [23]. To enhance efficiency, a compartmentalization strategy can be employed by targeting key enzymes, like those in the rGly pathway, to the mitochondria [22].

- Strain Evaluation and Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): Characterize the engineered strain in controlled bioreactors with methanol and CO₂. To improve performance, subject the strain to ALE in media with methanol as the sole carbon source. This can select for mutants with enhanced methanol assimilation and reduced formaldehyde toxicity, potentially leading to the discovery of novel pathways like the Adh2-Sfa1-rGly (ASrG) pathway [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The table below lists essential reagents and tools for conducting research in this field.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Methanol Pathway Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Recombination-Based Cloning (YRBC) | A low-cost, highly efficient cloning method that uses S. cerevisiae's homologous recombination to assemble multiple DNA fragments with short overlaps [23]. | Assembly of complex multi-gene pathways without the constraints of restriction enzymes [23]. |

| Luminex Single Antigen Bead (SAB) Assay | A solid-phase assay using microparticles to detect antibodies with high accuracy and sensitivity; mentioned here as an analogous high-precision detection method [25]. | Can be adapted for high-throughput protein or biomarker quantification in engineered strains. |

| Anti-Thymocyte Globulin (r-ATG) | A polyclonal antibody used in transplantation to suppress T-cell activity; mentioned here as an example of a biological reagent with a specific, targeted function [26]. | Not directly used in yeast engineering, but exemplifies a class of complex biological reagents. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | A genome editing technology that allows for precise gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and modifications. | Inactivation of native competing pathways (e.g., the XuMP cycle in P. pastoris) or integration of synthetic pathways [24] [22]. |

| Short Half-Life GFP (e.g., ubiM-GFP) | A reporter protein with a drastically reduced half-life (~1.5 hours) for precise, time-resolved monitoring of gene expression dynamics [24]. | Characterizing promoter and terminator activity in real-time during batch cultivations on different carbon sources [24]. |

The choice between 'Copy and Paste' and 'Mix and Match' pathway transplantation is not a simple binary decision but a strategic one. The 'Copy and Paste' approach offers a direct route to implementing a known, natural system but often results in suboptimal performance in a new host due to metabolic incompatibility and regulatory mismatches. In contrast, the 'Mix and Match' strategy, while more complex to design and implement, provides unparalleled flexibility to optimize flux, avoid toxic intermediates, and create novel synergies within the host's metabolic network. The emergence of evolved strains with entirely new pathways, such as the ASrG pathway, underscores that evolutionary engineering can be a powerful supplement to both rational design strategies. The future of pathway engineering lies in hybrid models that combine rational 'Mix and Match' design with high-throughput screening and evolutionary methods to achieve efficient, robust, and industrially viable microbial cell factories.

The pursuit of a sustainable, carbon-neutral bioeconomy has driven significant interest in engineering microbes to utilize one-carbon (C1) molecules like methanol and formate as feedstocks. These non-sugar substrates offer a path to reduce reliance on agricultural resources and create a circular carbon economy [3]. Among the various microbial chassis, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has emerged as a prominent platform for engineering C1 assimilation due to its genetic tractability, industrial robustness, and innate metabolic flexibility [13] [3]. This comparative analysis focuses on two principal engineering approaches for establishing C1 metabolism in yeasts: the reductive glycine (rGly) pathway and the synthetic Methanol/FOr mate Utilization via the Recursive Glycine (MFORG) pathway. We objectively evaluate their performance, experimental validation, and implementation requirements to provide researchers with a clear guide for pathway selection and application.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Engineered Yeasts

The table below summarizes key performance metrics and characteristics of yeasts engineered with different C1 assimilation pathways, based on recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Yeasts Engineered with C1 Assimilation Pathways

| Yeast Species | Pathway | C1 Substrate(s) | Maximum Growth Rate (μmax, h⁻¹) | Maximum OD600 | Key Features & Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae SCSA001 | Native ADH2 + rGly (ASrG) | Methanol | 0.0153 | 0.547 | Discovered via evolution; co-assimilates CO₂ | [13] |

| S. cerevisiae SMFORG01 | Synthetic MFORG | Methanol + Formate + CO₂ | ~0.006 | N/R | Mixotrophic; proof-of-concept for chemical production | [3] |

| S. cerevisiae CX01F | Heterologous Modules | Methanol | 0.051 | 2.0 | Rational design; produced flaviolin | [3] |

| Komagataella phaffii PMORG09 | Synthetic MFORG | Methanol + Formate + CO₂ | 0.019 | N/R | Superior performance vs. S. cerevisiae counterpart | [3] |

| K. phaffii (Evolved) | Synthetic CBB Cycle | CO₂ (Methanol for energy) | 0.018 | N/R | Uses methanol as an energy source for CO₂ fixation | [3] |

Table 2: Characteristics of Major C1 Assimilation Pathways in Yeasts

| Pathway | Native in Yeasts? | Primary C1 Input(s) | Key Advantages | Key Challenges | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XuMP Cycle | Yes (e.g., K. phaffii) | Methanol | Natural, efficient pathway in methylotrophs | Limited host range, complex compartmentalization | |

| rGly Pathway | Partially ( endogenous elements exist) | Formate, CO₂ | Linear, less complex; enables direct formate assimilation | Bottlenecks in C1-THF balancing and reducing power | [3] |

| ASrG Pathway | No (emerged in evolved S. cerevisiae) | Methanol, Formate, CO₂ | Discovered via ALE; demonstrates metabolic flexibility | Relies on endogenous enzyme promiscuity | [13] |

| Synthetic MFORG | No | Methanol, Formate, CO₂ | Enables mixotrophic, simultaneous C1 utilization | Requires extensive genetic engineering | [3] |

| Synthetic CBB Cycle | No | CO₂ | Direct CO₂ fixation | Very low efficiency; requires high energy (ATP) input | [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Engineering and Validation

Strain Development via Genome Rearrangement and Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE)

A powerful non-rational approach for generating synthetic methylotrophs involves combining SCRaMbLE (Synthetic Chromosome Rearrangement and Modification by LoxP-mediated Evolution) with subsequent ALE.

- SCRaMbLE Workflow: The process begins with a diploid S. cerevisiae base strain (e.g., SCDM001) carrying synthetic chromosomes and heterologous methanol assimilation genes. The Cre recombinase is activated, inducing genomic rearrangements (deletions, duplications, inversions). Populations are then screened in selective media, typically Delft minimal medium (MM) with 2% methanol, or a more stringent medium containing 6% methanol and 0.1% yeast extract, to isolate variants with improved methanol utilization [13].

- ALE Protocol: Even SCRaMbLEd strains may not achieve robust growth on methanol alone, often due to formaldehyde toxicity. To overcome this, ALE is performed. Evolutions are initiated in Delft MM with uracil (20 mg/L), 2% methanol, and a low concentration of yeast extract (0.1 g/L). After several generations, the yeast extract is removed to impose a stronger selective pressure for methanol-dependent growth. This process can take over 160 days but has proven successful in generating strains capable of using methanol as a sole carbon source [13].

In Vivo Pathway Validation via Isotopic Tracer Analysis

Confirming the operation and flux of engineered C1 pathways requires rigorous analytical methods.

- 13C-Methanol Tracer Assays: Evolved strains are cultivated in a minimal medium with 13C-labeled methanol as the sole carbon source. After a period of growth, cells are harvested, and metabolites are extracted. The 13C enrichment in proteinogenic amino acids is analyzed using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). The labeling patterns indicate the degree of methanol incorporation into central carbon metabolism. For instance, low but significant labeling across all amino acids, with glycine often showing the highest enrichment, suggests methanol assimilation coupled with CO₂ fixation [13].

- Reverse 13C-Bicarbonate Labeling: To confirm CO₂ fixation, assays are performed using 13C-NaHCO3 and 12C-methanol as co-substrates. The subsequent detection of 13C-labeled amino acids demonstrates that CO₂ is being fixed and incorporated into biomass, highlighting its role in supporting growth on methanol [13].

Pathway Architecture and Engineering Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the metabolic logic of key pathways and the experimental workflows used in their development.

MFORG Pathway Architecture

MFORG Pathway Flow - This diagram illustrates the synthetic MFORG pathway, which integrates the oxidation of methanol and the assimilation of formate with CO₂ fixation via the reductive glycine (rGly) module. The pathway funnels these C1 inputs into glycine, which is then converted to serine and pyruvate, ultimately feeding central metabolism for biomass and product formation [3].

ASrG Pathway Discovery Workflow

ASrG Pathway Discovery - This workflow outlines the combinatorial experimental strategy of genome rearrangement (SCRaMbLE) and adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) that led to the emergence of the Adh2-Sfa1-rGly (ASrG) pathway in S. cerevisiae, enabling growth on methanol without reliance on the initial heterologous pathway [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful engineering and analysis of C1 metabolism in yeasts rely on a core set of reagents, strains, and methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Engineering C1 Assimilation in Yeasts

| Category | Reagent / Solution / Method | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain Engineering | SCRaMbLE System | Induces genomic rearrangements in synthetic yeast chromosomes. | Requires strains from the Sc2.0 project with embedded loxP sites [13]. |

| Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) | Generates beneficial mutations for growth on C1 substrates under selective pressure. | Performed in bioreactors or serial batch cultures over months [13]. | |

| Culture Media | Delft Minimal Medium | Defined medium for selection and growth of methylotrophic yeasts. | Used with 2% methanol; uracil (20 mg/L) added for auxotrophic strains [13]. |

| Methanol Feedstock | Primary C1 substrate for methylotrophy studies. | Concentrations from 1-6% (v/v) are typical; filter-sterilized [13] [3]. | |

| Analytical Tools | 13C-Methanol / 13C-NaHCO3 | Isotopic tracers for validating pathway flux and carbon incorporation. | >99% atom purity; used in GC-MS analysis of proteinogenic amino acids [13]. |

| GC-MS | Quantifies 13C-enrichment in metabolites to confirm C1 assimilation. | Standard protocol for analysis of hydrolyzed cellular protein [13]. | |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing | Identifies mutations underlying evolved phenotypes. | Illumina/WGS used to find causal genomic changes in evolved strains [13]. | |

| Key Enzymes/Genes | ADH2 (Alcohol Dehydrogenase 2) | Native S. cerevisiae enzyme capable of oxidizing methanol to formaldehyde. | A key component of the emergent ASrG pathway [13]. |

| SFA1 (Alcohol Dehydrogenase III) | Bifunctional formaldehyde dehydrogenase/glutathione-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase. | Critical for formaldehyde detoxification and dissimilation [13] [3]. | |

| rGly Pathway Genes (e.g., GCV1, SHMT) | Enzymes of the glycine cleavage system and serine hydroxymethyltransferase. | Enable formate and CO₂ assimilation into central metabolism [3]. |

Compartmentalization and Enzyme Complexing to Enhance Metabolic Flux

The engineering of microbial cell factories for efficient bioproduction represents a cornerstone of industrial biotechnology. Central to this endeavor is the optimization of metabolic flux—the directed flow of metabolites through biosynthetic pathways toward desired products. In the specific context of methanol assimilation in engineered yeasts, this challenge is particularly acute. Methanol, a renewable one-carbon (C1) feedstock derived from CO2, offers a sustainable alternative to sugar-based substrates but introduces unique metabolic constraints due to its distinct assimilation pathways and potential toxicity [4] [27].

Traditional metabolic engineering strategies have focused on modulating gene expression, deleting competing pathways, and enzyme engineering. However, these approaches often overlook a fundamental principle of cellular organization: spatial compartmentalization. In eukaryotic cells, metabolism is organized within distinct subcellular compartments—such as mitochondria, peroxisomes, and the endoplasmic reticulum—which create unique physicochemical environments and concentrate specific cofactors and metabolites [28] [29]. This spatial organization is not merely structural but functional, enabling cells to optimize metabolic pathways, isolate toxic intermediates, and regulate flux.

This review provides a comparative analysis of two powerful strategies for enhancing metabolic flux in engineered yeasts: subcellular compartmentalization and enzyme complexing. We objectively evaluate their performance in redirecting methanol assimilation pathways, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to guide researchers in selecting and implementing these advanced metabolic engineering tools.

Compartmentalization Engineering: Harnessing Cellular Architecture

Principles and Strategic Advantages

Compartmentalization engineering involves relocating metabolic pathways from the cytosol into specific organelles to exploit their native biochemical environments. This strategy offers several distinct advantages for methanol-based bioproduction [28]:

- Precursor and Cofactor Access: Organelles often harbor concentrated pools of specific precursors (e.g., acetyl-CoA in mitochondria) and cofactors (e.g., NADH), bypassing cytosolic limitations.

- Toxic Intermediate Sequestration: Membranous organelles can insulate the cytosol from toxic pathway intermediates or products, such as formaldehyde from methanol oxidation.

- Blocking Competing Reactions: Physical separation from cytosolic enzymes minimizes diversion of intermediates into competing, non-productive pathways.

- Enhanced Storage Capacity: Hydrophobic organelles like lipid droplets provide storage environments for non-polar products like terpenoids.

Comparative Performance of Organelle-Targeting Strategies

Research has demonstrated that the choice of organelle significantly impacts production outcomes. The table below summarizes the performance of various compartmentalization strategies in yeast for the production of different chemical classes.

Table 1: Performance of Subcellular Compartmentalization Strategies in Yeast

| Product | Product Class | Strategy | Organism | Compartment | Titer / Yield | Key Genetic Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Humulene [28] | Sesquiterpene | Utilize native acetyl-CoA in peroxisome | Yarrowia lipolytica | Peroxisome | 3.2 g/L | — |

| Squalene [28] | Triterpene | Dual MVA pathway in mitochondria and cytoplasm | S. cerevisiae | Mitochondria & Cytoplasm | 21.1 g/L | — |

| Amorpha-4,11-diene [28] | Sesquiterpene | Harness mitochondria acetyl-CoA; reduce FPP loss to cytosol | S. cerevisiae | Mitochondria | 427 mg/L | — |

| Succinic Acid [29] | Organic Acid | Decompartmentalization of mitochondrial PDH to cytosol | I. orientalis | Cytosol (via decompartmentalization) | 104 g/L, 0.85 g/g glucose | Cytosolic Pyruvate Dehydrogenase (PDH), Glyoxylate Shunt |

| Lycopene [28] | Tetraterpene | Regulate lipid-droplet size to increase storage | S. cerevisiae | Lipid Droplets | — | GPD1, PAH1, DGAT1, SEI1 (to increase LD volume) |

| Ginsenoside [28] | Triterpene | Target pathway to LDs; increase LD volumes | S. cerevisiae | Lipid Droplets | 5 g/L | GPD1, PAH1, DGAT1, SEI1 |

Experimental Protocol: Peroxisomal Compartmentalization for Sesquiterpene Production

The high-level production of α-humulene in Yarrowia lipolytica via peroxisomal targeting serves as an exemplary protocol [28].

- Strain Engineering:

- Vector Construction: Clone genes encoding the mevalonate (MVA) pathway and α-humulene synthase, fused to peroxisomal targeting signal 1 (PTS1) sequences (e.g., -SKL), into an appropriate expression vector.

- Transformation: Introduce the constructed vector into a Y. lipolytica host strain using standard transformation protocols like lithium acetate or electroporation.

- Cultivation and Induction:

- Inoculate engineered strains in a defined medium with glucose as a carbon source for initial growth.

- Induce the expression of the peroxisomal pathway during the mid-exponential phase, typically by adding methanol or switching to a methanol-containing medium if using methanol-inducible promoters.

- Analytical Quantification:

- Product Titer: Extract intracellular terpenoids using organic solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate or hexane) and quantify α-humulene using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

- Metabolite Analysis: Monitor metabolic intermediates and potential byproducts via Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) or HPLC to assess flux rewiring.

Visualizing Compartmentalization and Decompartmentalization Strategies

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts of compartmentalization and the more recent strategy of decompartmentalization for enhancing cytosolic cofactor supply.

Diagram 1: Compartmentalization vs. Decompartmentalization Strategies. Compartmentalization (yellow) involves moving pathways into organelles to exploit their native environment. In contrast, decompartmentalization (green) brings key cofactor-generating enzymes from organelles into the cytosol to augment its metabolic capacity.

Enzyme Complexing: Creating Synthetic Assemblies

Principles and Strategic Advantages

Enzyme complexing is a biomimetic strategy that co-localizes sequential enzymes of a pathway into supramolecular structures, mimicking natural multi-enzyme complexes. This approach enhances metabolic flux through several mechanisms [30]:

- Substrate Channeling: Direct transfer of intermediates between active sites minimizes diffusion loss, reduces intermediate degradation, and shields toxic metabolites.

- Increased Local Concentration: Proximity effect elevates the local concentration of enzymes and substrates, accelerating reaction kinetics.

- Reduced Metabolic Crosstalk: Aggregation of pathway enzymes minimizes unwanted interference with native cellular metabolism.

Comparative Analysis of Enzyme Assembly Scaffolds

Various scaffolding systems have been developed, each with distinct characteristics and performance outcomes.

Table 2: Comparison of Enzyme Assembly and Scaffolding Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Components | Reported Enhancement | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold-Free Peptide Tags [30] | RIAD/RIDD interaction from PKA system | RIAD peptide, RIDD docking domain | 5.7-fold increase in carotenoid production in E. coli | Simple genetic design, self-assembling, tunable stoichiometry | Limited to organizing 2-3 enzymes; efficiency depends on target enzyme oligomerization |

| Protein Interaction Domains [30] | SH3-ligand, PDZ-ligand pairs | SH3 domain, PDZ domain | 97-fold in vitro and 9-fold in vivo increase in F6P from methanol | High-affinity interactions, modular | Potential metabolic burden from large protein domains |

| Synthetic Membraneless Organelles [31] | Phase-separated condensates | DIX, PB1 domains forming living polymers | Boosted human milk oligosaccharide production in E. coli | High enzyme density, can concentrate substrates and cofactors | Relatively new technology; potential pleiotropic effects on cell physiology |

| Active Inclusion Bodies (CatIBs) [30] | Aggregation-prone peptide fusion | Coiled-coil domains (e.g., from MalE31) | 3x higher activity in (R)-benzoins synthesis | Excellent stability and reusability, carrier-free immobilization | Primarily used for in vitro biocatalysis; application in vivo can be challenging |

Experimental Protocol: Scaffold-Free Assembly with RIAD/RIDD

The RIAD/RIDD system provides a robust method for creating scaffold-free enzyme assemblies in vivo [30].

- Plasmid Construction:

- Genetically fuse the short RIAD peptide tag to the C- or N-terminus of one pathway enzyme (e.g., the last enzyme of the mevalonate pathway).

- Fuse the RIDD docking domain to the complementary terminus of the subsequent pathway enzyme (e.g., the first enzyme of the carotenoid pathway).

- Clone the fused gene constructs into a compatible expression vector under a strong promoter.

- Strain Transformation and Validation:

- Transform the constructed plasmid into the host yeast strain (e.g., S. cerevisiae).

- Protein-Protein Interaction Validation: Confirm complex formation in vivo using techniques like Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) or Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC).

- Complex Characterization: Isolate the protein complexes via size-exclusion chromatography or native PAGE and analyze their size and stoichiometry.

- Fermentation and Metabolite Analysis:

- Cultivate the engineered strain in appropriate medium, inducing expression during the exponential phase.

- Monitor cell growth and periodically sample the culture for product analysis via HPLC or GC-MS to quantify the enhancement in target compound titer and yield compared to unassembled controls.

Visualizing Enzyme Complexing for Metabolic Flux

The workflow for implementing and validating enzyme complexing strategies is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Enzyme Complexing. The process begins with the genetic fusion of interaction tags to target enzymes, followed by co-expression in a host organism. The formation of functional complexes must be validated before assessing their impact on metabolic flux and product titer during fermentation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of compartmentalization and enzyme complexing relies on a suite of specialized research reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Flux Enhancement Strategies

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting Signals | PTS1 (e.g., -SKL), Mitochondrial Targeting Signal (MTS), ER retention signal (HDEL) | Directs nuclear-encoded proteins to specific organelles like peroxisomes, mitochondria, or the endoplasmic reticulum [28]. |

| Protein Interaction Modules | RIAD/RIDD peptides, SH3 domain and ligand, PDZ domain and ligand | Mediates specific, high-affinity interactions between engineered enzymes to form scaffold-free complexes [30]. |

| Scaffolding Domains | DIX domains, PB1 domains, Coiled-coil peptides | Forms the structural backbone of synthetic membraneless organelles or protein scaffolds for enzyme co-localization [31]. |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 system for Komagataella phaffii and S. cerevisiae, Golden Gate assembly | Enables precise gene knock-in, knockout, and multiplexed engineering of metabolic pathways and compartmentalization systems [32] [18]. |

| Analytical Techniques | GC-MS, HPLC, LC-MS, 13C-based Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) | Quantifies product titers, yields, and metabolic intermediates; traces carbon flux through engineered pathways [29] [18]. |

The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that both compartmentalization and enzyme complexing are powerful, yet distinct, strategies for overcoming metabolic flux limitations in engineered yeasts. The choice between them depends on the specific bottlenecks of the pathway and the host organism.

Compartmentalization is particularly effective when the goal is to access a unique organellar resource (precursors, cofactors), isolate toxic compounds, or leverage storage capacity. The impressive production of α-humulene (3.2 g/L) and squalene (21.1 g/L) showcases its power for isoprenoid biosynthesis [28]. Conversely, enzyme complexing excels at accelerating linear segments of a pathway by mitigating diffusion limitations and protecting unstable intermediates, as evidenced by the several-fold enhancements in product output [30] [31].

A emerging frontier is the integration of these strategies. For instance, enzyme complexes could be targeted en masse to specific organelles, potentially synergizing the benefits of substrate channeling with those of a specialized organellar environment. Furthermore, the novel concept of decompartmentalization—strategically relocating organellar enzymes to the cytosol to enhance cofactor supply—has proven highly effective for producing highly reduced chemicals like succinic acid, achieving a remarkable titer of 104 g/L and a yield surpassing theoretical cytosolic limits [29]. This approach, along with the discovery and engineering of non-native methanol assimilation routes like the reductive glycine pathway (rGlyP) in K. phaffii [18], opens new avenues for rewiring C1 metabolism.

As synthetic biology tools advance, the precision with which we can re-engineer cellular spatial organization will continue to grow. The development of more orthogonal scaffolding systems, light-inducible compartments, and dynamic regulatory circuits will enable unprecedented control over metabolic flux, further establishing methanol-based yeast biomanufacturing as a pillar of the sustainable bioeconomy.

Within the field of industrial biotechnology, the use of non-conditional carbon sources is paramount for developing sustainable bioprocesses. Methanol, a liquid one-carbon (C1) compound that can be synthesized from CO2, represents a promising feedstock for microbial fermentation [4] [22]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of engineered yeast strains developed for the production of terpenoids and organic acids from sole methanol, focusing on their performance, underlying metabolic pathways, and the experimental methodologies essential for their evaluation. The objective is to offer researchers and scientists a clear comparison of platform technologies based on methanol assimilation pathways, supported by structured experimental data and protocols.

Comparative Performance of Methanol-Based Microbial Cell Factories

The table below summarizes the production performance of various engineered yeasts for synthesizing organic acids and terpenoids from methanol.

Table 1: Production Performance of Engineered Yeasts on Methanol

| Product Category | Specific Product | Host Chassis | Methanol Assimilation Pathway | Maximum Titer | Productivity | Yield | Key Engineering Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Acid | Erythritol [4] | Pichia pastoris | Native XuMP Cycle | 21.1 g/L | 0.22 g/L/h | 0.14 g/g | Rewiring central carbon metabolism via a hybrid XuMP/RuMP pathway. |

| Organic Acid | 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (5-ALA) [22] | Pichia pastoris | Synthetic MFORG Pathway | 67.5 mg/L | Information Not Specified | Information Not Specified | Expression of the hemA gene from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. |

| Organic Acid | Lactic Acid [22] | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Synthetic MFORG Pathway | 1.73 g/L | Information Not Specified | Information Not Specified | Expression of a heterologous lactate dehydrogenase. |

| Terpenoid | Information Not Specified | Ogataea methanolica[ccitation:3] | Native XuMP Cycle | Information Not Specified | Information Not Specified | Information Not Specified | Native methylotroph; studied for metabolic adaptation to high methanol. |

Performance Analysis

- Erythritol Production in P. pastoris: The high titer of 21.1 g/L demonstrates the potential of engineering native methylotrophs by redirecting natural metabolism [4].

- Organic Acid Production via Synthetic Pathways: The synthesis of 5-ALA and lactic acid shows that the synthetic MFORG pathway can successfully support production in both native (P. pastoris) and non-native (S. cerevisiae) methylotrophic hosts [22].

- Terpenoid Production Landscape: Direct case studies reporting high titers of terpenoids from sole methanol are limited in the provided search results. Ogataea methanolica is noted as a potential chassis but without specific production data [33]. Microbial production of terpenoids is well-established, but typically relies on sugar-based feedstocks [34] [35].

Detailed Experimental Protocols