Microbial Cell Factories: Development, Applications, and Future in Sustainable Biomanufacturing

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the development of microbial cell factories (MCFs) for sustainable chemical and therapeutic production.

Microbial Cell Factories: Development, Applications, and Future in Sustainable Biomanufacturing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the development of microbial cell factories (MCFs) for sustainable chemical and therapeutic production. It explores the foundational principles of selecting and engineering microbial chassis, delves into advanced methodological strategies like systems metabolic engineering and synthetic biology, and addresses key challenges in optimization and troubleshooting. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it also presents a comparative analysis of host performance and validation techniques, highlighting the transformative potential of MCFs in creating a sustainable bioeconomy and advancing biomedical research.

What Are Microbial Cell Factories? Exploring Chassis and Core Concepts

Defining Microbial Cell Factories and Their Role in the Bioeconomy

Microbial Cell Factories (MCFs) are engineered microorganisms that serve as living production platforms for a wide array of bioproducts, ranging from pharmaceuticals and biofuels to industrial chemicals and food ingredients [1] [2]. In the context of the emerging bioeconomy—an economic system that leverages renewable biological resources and processes to produce goods and services more sustainably—MCFs are regarded as the fundamental "chips" of biomanufacturing [1]. These biological workhorses are poised to fuel a transformative shift away from fossil resource dependence toward a more circular and sustainable economic model [3] [4]. The development of efficient MCFs integrates advanced disciplines including synthetic biology, systems biology, metabolic engineering, and evolutionary engineering, enabling the redesign of microbial metabolism for optimized production of target compounds [5]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of MCF capabilities, host selection criteria, engineering methodologies, and their integral role within the broader bioeconomy, serving as a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in MCF development research.

Core Principles and Economic Significance

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

At their core, Microbial Cell Factories are chassis cells—model or non-model microorganisms—that have been systematically engineered to function as efficient producers of target compounds. Their development requires a comprehensive understanding of several foundational elements: accurate genome sequences and corresponding annotations; the metabolic and regulatory networks governing substances, energy, physiology, and information flow within the cell; and the similarities and unique characteristics of potential chassis organisms compared to other microorganisms [1]. The engineering process involves the identification and characterization of biological parts, along with the design, synthesis, assembly, editing, and regulation of genes, circuits, and pathways to redirect microbial metabolism toward desired products [1] [2].

Role in the Bioeconomy

The bioeconomy encompasses the production, trade, distribution, management, and consumption of goods, processes, and services derived from biological resources and biological transformation processes [4]. Within this framework, MCFs play a pivotal role in multiple sectors:

- Sustainable Production: MCFs enable the production of chemicals, materials, and energy from renewable biomass instead of fossil resources, reducing environmental impact and enhancing sustainability [5] [3].

- Circular Economy: They contribute to circular economic models by converting waste streams, such as agricultural residues or industrial byproducts, into valuable commodities [6] [4].

- Supply Chain Resilience: By enabling domestic production of essential chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and fuels, MCF-based biomanufacturing strengthens supply chain security and reduces import dependencies [3].

The convergence of MCF technologies with advances in automation and artificial intelligence is further accelerating their industrial adoption, facilitating the development of customized artificial synthetic MCFs and expediting the industrialization process of biomanufacturing [1].

Market Trajectory and Economic Impact

The global market for microbial cell factories demonstrates robust growth, reflecting their increasing economic importance. Table 1 summarizes the market projections and key growth areas.

Table 1: Microbial Cell Factories Market Overview and Projections

| Market Aspect | 2023/2025 Projections | 2033 Projection | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Key Growth Segments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Market | $5 billion (2025) [7] | $12 billion [7] | 12% (2025-2033) [7] | Biopharmaceuticals, Biofuels, Sustainable Chemicals |

| Alternative Estimate | $2.5 billion (2025) [8] | Exceeding $7 billion [8] | 12% (2025-2033) [8] | Pharmaceuticals, Chemicals, Biofuels |

| Segment Analysis | ||||

| Biopharmaceuticals | $150 million (2023) [8] | - | - | Largest market share [7] [8] |

| Industrial Enzymes | $80 million (2023) [8] | - | - | Food, Textile, Biofuel Industries [8] |

| Biofuels & Biomaterials | $50 million (2023) [8] | - | - | Driven by fossil fuel alternative demand [8] |

This market expansion is fueled by rising demand for sustainable biomanufacturing, advancements in genetic engineering tools, and supportive government policies promoting bio-based alternatives to traditional chemical processes [7] [8]. North America and Europe currently hold significant market shares due to established biopharmaceutical industries and advanced infrastructure, while the Asia-Pacific region is experiencing the most rapid growth, driven by increasing industrialization and government support for biotechnology [7] [8].

Host Strain Selection and Capacity Evaluation

Criteria for Host Selection

Selecting an appropriate microbial host is a critical first step in developing an efficient MCF. This decision requires consideration of multiple factors beyond mere genetic tractability [5]:

- Native Metabolic Capacity: The presence of innate biosynthetic pathways for the target chemical or the potential to effectively produce it when heterologous pathways are introduced.

- Production Performance: The microorganism's potential to achieve high titers (product amount per volume), productivity (production rate per unit of biomass or volume), and yield (product per consumed substrate) [5].

- Substrate Utilization: The ability to efficiently consume low-cost, renewable carbon sources, including various sugars, glycerol, or one-carbon compounds like methanol and formate [6] [5].

- Process Compatibility: Resilience to process conditions, including tolerance to the target product and byproducts, as well as oxygen requirements (aerobic, microaerobic, or anaerobic) [5].

- Safety and Regulation: The microorganism's safety profile (Generally Recognized as Safe - GRAS status) and regulatory acceptance for the intended application, particularly in food and pharmaceutical production [5].

Comparative Analysis of Major Industrial Hosts

A comprehensive evaluation of microbial capacities provides critical data for rational host selection. Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of five major industrial microorganisms, highlighting their metabolic capabilities for producing specific chemicals.

Table 2: Metabolic Capacities of Representative Industrial Microorganisms

| Host Microorganism | Exemplary Product | Maximum Theoretical Yield (YT) (mol/mol glucose) | Key Characteristics and Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | L-Lysine | 0.7985 [5] | Versatile metabolism; Extensive genetic toolboxes; Rapid growth [5] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | L-Lysine | 0.8571 [5] | GRAS status; Robust in fermentation; Native resilience to low pH and inhibitors [5] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | L-Lysine | 0.8098 [5] | Industrial workhorse for amino acids; GRAS status; Efficient carbon conversion [5] |

| Bacillus subtilis | L-Lysine | 0.8214 [5] | GRAS status; Efficient protein secretion; Spore formation for resilience [5] |

| Pseudomonas putida | L-Lysine | 0.7680 [5] | Exceptional metabolic versatility and stress tolerance; Can use diverse carbon sources [5] |

This systematic evaluation, facilitated by genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), enables researchers to identify the most suitable host for specific chemical production based on quantitative metrics rather than historical precedent alone [5]. For instance, while S. cerevisiae shows the highest theoretical yield for L-lysine, industry often utilizes C. glutamicum due to its established high production performance and regulatory acceptance [5].

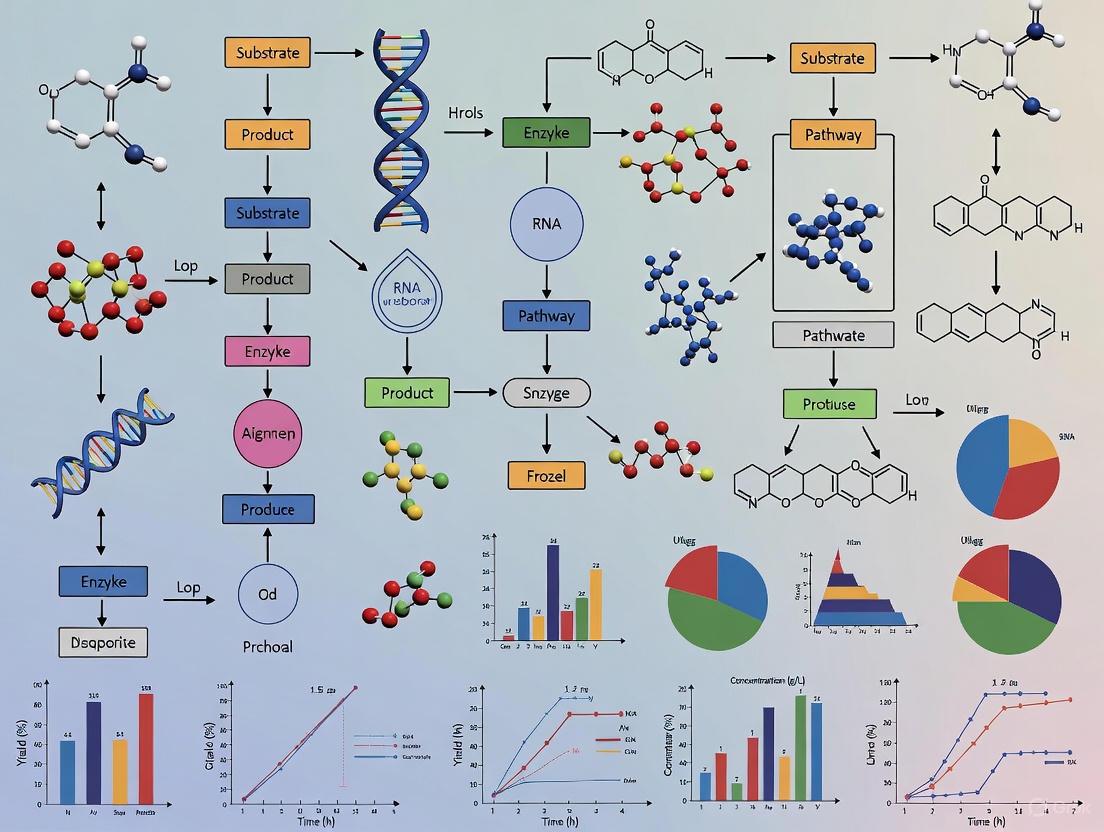

Diagram 1: Logical workflow for selecting a microbial host strain for cell factory development.

Engineering Strategies and Experimental Protocols

Systems Metabolic Engineering Framework

Constructing an efficient MCF requires a systematic engineering approach that integrates multiple disciplines. Systems metabolic engineering combines traditional metabolic engineering with strategies and tools from synthetic biology, systems biology, and evolutionary engineering [5]. This framework encompasses several key phases:

- Project Design: Defining the target product, identifying or designing biosynthetic pathways, and selecting the host strain based on comprehensive criteria [5].

- Metabolic Pathway Reconstruction: Introducing and optimizing heterologous pathways or rewiring native metabolism to direct carbon flux toward the target product [1] [5].

- Metabolic Flux Optimization: Fine-tuning gene expression, regulating enzyme activities, and removing metabolic bottlenecks to maximize yield and productivity [5].

- Strain Performance Validation: Testing engineered strains under controlled laboratory conditions and scaling up to industrial fermentation processes [6].

Case Study: Two-Step Fermentation of Crude Glycerol to Hydrogen

A recent innovative study exemplifies the application of integrated MCF development, creating a two-step fermentation process to convert crude glycerol—a biodiesel production byproduct—into clean hydrogen gas [6]. The detailed experimental protocol and results are presented below.

Experimental Protocol

Step 1: L-Malate Biosynthesis via Engineered E. coli

- Objective: Convert crude glycerol to L-malate using a metabolically engineered E. coli strain.

- Strain Engineering:

- Base Strain: E. coli M4-ΔiclR/pck (previously engineered for efficient C4 dicarboxylic acid production).

- Further Modification: Overexpression of the glycerol kinase gene (glpK) to enhance glycerol uptake and metabolism [6].

- Culture Conditions:

- Medium: Minimal medium supplemented with crude glycerol (19 g/L) as the primary carbon source.

- Bioreactor: 0.5 L miniature bioreactor system.

- Optimized Parameters: Initial OD₅₇₀ of 1.1 (high initial biomass), dissolved oxygen at 20%, temperature 37°C [6].

- Analytical Methods: HPLC for quantification of L-malate and residual glycerol.

- Outcome: The engineered M4-ΔiclR/pck-glpK strain achieved an L-malate titer of 11.41 ± 2.88 g/L in 24 hours, with a molar yield of 0.80 ± 0.09 mol/mol from crude glycerol [6].

Step 2: Photofermentation for Hydrogen Production via Rhodobacter capsulatus

- Objective: Convert the L-malate rich fermentation broth from Step 1 into hydrogen gas.

- Strain: Wild-type Rhodobacter capsulatus, a purple non-sulfur bacterium capable of photofermentation [6].

- Process:

- Substrate: Cell-free supernatant from the E. coli fermentation, containing L-malate and residual organic acids (succinate, acetate) and glycerol.

- Bioreactor: Photobioreactor system with controlled illumination.

- Optimal Substrate Concentration: 3 g/L L-malate [6].

- Conditions: Anaerobic conditions, light intensity 100 W/m², temperature 30°C.

- Gas Analysis: Hydrogen concentration in the evolved gas measured by gas chromatography.

- Outcome: Maximum hydrogen production of 58.0 ± 6.0 mmol H₂/92 h, with a production rate of 0.63 mmol/L·h. The bacterium consumed 87.1% of the total available carbon sources in the broth [6].

Diagram 2: Two-step integrated bioprocess for hydrogen production from crude glycerol.

Key Findings and Innovation

This integrated process demonstrates several advanced MCF concepts:

- Waste-to-Value Transformation: Successfully converts an industrial byproduct (crude glycerol) into a high-value clean energy carrier (hydrogen) [6].

- Metabolic Engineering Impact: Overexpression of a single key gene (glpK) significantly enhanced glycerol consumption rate from 0.21 to 0.46 g/L·h and doubled L-malate production [6].

- Process Integration Advantage: Eliminates the need for costly purification of L-malate before the second fermentation step, reducing overall production costs [6].

- Carbon Efficiency: The two-step process achieved a total carbon source utilization of 87.1%, demonstrating high efficiency in converting waste carbon into product [6].

Enabling Technologies and Research Toolkit

Advanced Genetic and Computational Tools

The development of high-performing MCFs relies on a sophisticated toolkit of enabling technologies. Key tools and their applications include:

- CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing: Enables precise, targeted modifications to microbial genomes for gene knockouts, knock-ins, and regulatory element engineering, significantly accelerating strain development cycles [7] [8].

- Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs): Mathematical representations of metabolic networks that simulate organism physiology. GEMs are used to predict metabolic fluxes, identify engineering targets (gene knockouts), and calculate theoretical maximum yields (Yₜ and Yₐ) for various host-product pairs [5].

- Automation and High-Throughput Screening: Robotic systems and micro-bioreactors facilitate rapid testing of thousands of microbial variants and cultivation conditions, compressing development timelines [1] [3].

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning: AI-powered tools analyze complex biological data to predict optimal genetic designs, fermentation parameters, and enzyme structures, enabling more rational and efficient MCF development [1] [4].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental work in MCF development depends on specialized reagents and materials. Table 3 catalogs key research reagent solutions essential for conducting MCF research and development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Cell Factory Development

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application in MCF R&D |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Microbial Chassis | E. coli M4-ΔiclR/pck-glpK [6], S. cerevisiae strains with heterologous pathways [5] | Production hosts with optimized metabolic pathways for specific target molecules. |

| Specialized Growth Media | Minimal media with defined carbon sources (e.g., crude glycerol, glucose) [6] [5] | Support microbial growth while directing metabolism toward product formation; enable study of substrate utilization. |

| Molecular Biology Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems [7] [8], Expression plasmids, Synthetic genes (e.g., glpK, CYP722A/B) [6] [9] | Genetic modification and pathway engineering to alter or enhance microbial metabolic capabilities. |

| Bioreactor Systems | Miniature bioreactors (0.5 L) [6], Photobioreactors [6] | Provide controlled, scalable environments for optimizing fermentation conditions and monitoring production metrics. |

| Analytical Standards & Kits | L-Malate standard [6], Metabolite quantification kits, Gas chromatography systems [6] | Accurate identification and quantification of target products, substrates, and metabolic intermediates. |

| Computational Resources | Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) for host organisms [5], Pathway prediction software | In silico prediction of metabolic behavior, identification of engineering targets, and calculation of theoretical yields. |

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, MCF development and commercialization face several persistent challenges that drive ongoing research:

- Scalability: Translating laboratory-scale production to industrially relevant volumes remains complex and costly, often encountering unforeseen biological and engineering constraints [7] [8].

- Regulatory Hurdles: Obtaining regulatory approvals for novel bio-based products, particularly in pharmaceutical and food applications, involves lengthy and expensive processes that can hinder market entry [7] [8].

- Economic Viability: High initial investment costs for specialized equipment and the need for further technological advances to enhance cost-effectiveness relative to chemical synthesis routes present significant barriers [7] [8].

- Host Robustness: Engineering strains that maintain high productivity under industrial fermentation conditions, including resistance to inhibitors and product toxicity, remains challenging [5].

Future development in MCF technology is likely to focus on several key areas:

- Integration of Automation and AI: The continued convergence of biotechnology with automation and artificial intelligence will accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle, enabling more rapid development of optimized MCFs [1] [3].

- Expansion to Non-Model Hosts: Increasing capability to engineer non-model microorganisms that possess native abilities to produce valuable compounds or utilize inexpensive feedstocks will expand the range of viable MCF platforms [1] [5].

- Continuous Bioprocessing: Transition from batch to continuous fermentation processes promises to improve efficiency, reduce production costs, and increase overall productivity [7].

- Sustainable Feedstock Utilization: Enhanced focus on using waste carbon streams (e.g., agricultural residues, industrial off-gases, food waste) as feedstocks will improve the sustainability and economic profile of MCF-based bioprocesses [6] [4].

As microbial cell factory technologies continue to mature, they are poised to play an increasingly central role in the transition toward a more sustainable, bio-based economy, enabling the production of diverse goods—from pharmaceuticals to fuels and materials—through biological transformation rather than traditional extractive and chemical processes.

The field of microbial cell factory development is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by both necessity and technological innovation. While model organisms like E. coli and S. cerevisiae have long served as the workhorses of industrial biotechnology, there is growing recognition that their capabilities represent only a fraction of nature's biosynthetic potential. The exploration of microbial biodiversity—spanning extreme environments, unconventional hosts, and previously unculturable taxa—has emerged as a critical frontier for discovering novel metabolic pathways, enzymes, and regulatory mechanisms with applications across pharmaceutical production, bioremediation, and sustainable manufacturing [10] [11]. This paradigm shift is fundamentally redefining microbial cell factory research, moving beyond traditional genetic manipulation of established hosts toward the systematic discovery, characterization, and engineering of non-conventional microbial systems.

The drive toward biodiversity exploration is fueled by several converging factors. First, the limitations of existing platform organisms have become increasingly apparent for specialized chemical production, particularly complex natural products requiring specific cellular compartments, cofactors, or metabolic contexts. Second, advances in sequencing technologies, bioinformatics, and cultivation methods have dramatically reduced the barriers to studying non-model microbes. Finally, the urgent need for sustainable bioprocesses has intensified the search for microorganisms with innate capabilities for valorizing waste streams, degrading pollutants, or performing challenging chemistries under mild conditions [10]. This technical guide examines the methodologies, tools, and strategic approaches enabling researchers to navigate this expanding landscape of microbial biodiversity for cell factory development.

Technological Enablers for Discovering Microbial Diversity

Advanced Sequencing and Genome Resolution

The single most transformative development in microbial biodiversity research has been the advent of genome-resolved long-read sequencing. Traditional short-read sequencing approaches often failed to resolve complex genomic regions, leading to fragmented assemblies that obscured true microbial diversity. The implementation of platforms such as Oxford Nanopore and Pacific Biosciences has enabled researchers to reconstruct near-complete microbial genomes directly from environmental samples without requiring cultivation [11].

A landmark 2025 study published in Nature Microbiology demonstrated the power of this approach by revealing an astonishing wealth of previously unknown microbes across diverse terrestrial habitats. By capturing DNA fragments thousands to millions of bases long, researchers successfully resolved structural variations, repetitive elements, and mobile genetic elements that had previously remained cryptic. This technical advance has not only expanded the known microbial tree of life but has provided the high-quality genomic blueprints essential for understanding metabolic potential and designing engineering strategies [11]. The functional insights gleaned from these complete genomes—particularly regarding roles in carbon fixation, nitrogen transformation, and sulfur metabolism—provide critical starting points for selecting non-conventional hosts with desirable innate capabilities for specific bioproduction applications.

Computational Tools for Data Integration and Visualization

The deluge of data generated by modern biodiversity studies necessitates sophisticated computational tools for integration, analysis, and interpretation. The MINERVA (Microbiome Network Research and Visualization Atlas) platform represents a cutting-edge approach to this challenge, leveraging fine-tuned large language models to systematically map microbe-disease associations across extensive scientific literature [12]. While initially developed for clinical applications, this platform's underlying architecture—which constructs a rich, ontology-driven knowledge graph from processed publications—offers a powerful framework for organizing biodiversity information relevant to cell factory development.

For metabolomic data integration, effective visualization strategies are essential for interpreting complex datasets. Recent reviews have outlined comprehensive approaches for visualizing untargeted metabolomics data throughout the analytical workflow, from data quality assessment to cross-omics integration [13]. These visualization strategies enable researchers to identify patterns, assess analytical quality, and generate hypotheses about metabolic functions across diverse microbial isolates. The combination of computational tools like MINERVA with advanced visualization techniques creates an ecosystem for knowledge synthesis that greatly accelerates the identification of promising non-conventional hosts from complex biodiversity data.

Table 1: Key Analytical Methods for Microbial Biodiversity Exploration

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications in Biodiversity Research | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Sequencing | Genome-resolved long-read sequencing [11] | Reconstruction of near-complete genomes from environmental samples; identification of novel lineages | Reduces assembly ambiguity; reveals structural variations; requires sophisticated bioinformatics |

| Community Interaction Analysis | Dynamic Covariance Mapping (DCM) [14] | Quantification of inter- and intra-species interactions in complex communities | Requires high-resolution abundance time-series data; accounts for ecological and evolutionary timescales |

| Data Integration | Sparse Canonical Correlation Analysis (sCCA), Sparse PLS (sPLS) [15] | Identification of associations between microbial taxa and metabolic profiles | Handles high-dimensional, compositional data; performs feature selection |

| Knowledge Synthesis | LLM-powered knowledge graphs (MINERVA) [12] | Extraction and organization of microbial associations from scientific literature | Mitigates hallucination through verification processes; provides explainable outputs |

Methodologies for Functional Characterization of Microbial Communities

Dynamic Covariance Mapping for Community Interaction Analysis

Understanding the functional dynamics within microbial communities requires moving beyond compositional snapshots to quantify how members influence each other's growth and activity. Dynamic Covariance Mapping (DCM) has emerged as a powerful general approach for inferring microbiome interaction matrices from abundance time-series data [14]. The mathematical foundation of DCM rests on estimating how the covariance between the abundance time series of one member and the growth rate (time derivative) of another reveals their ecological interaction strength.

The DCM methodology, when combined with high-resolution chromosomal barcoding, enables researchers to quantify both inter- and intra-species interactions during colonization or perturbation events. In practice, this approach involves tracking microbial abundances at high temporal resolution, calculating growth rates through numerical differentiation, and computing the covariance structures that reveal interaction patterns. This method has revealed distinct temporal phases during community assembly: initial destabilization upon invasion, partial recolonization of native members, and establishment of a quasi-steady state where lineages coexist with residents through specific interaction networks [14].

The experimental workflow for implementing DCM involves several critical steps. First, researchers must obtain high-resolution abundance data through methods such as barcode sequencing, 16S rRNA profiling, or metagenomic sequencing. Second, time-series measurements must be sufficiently frequent to reliably estimate growth rates through numerical differentiation. Third, statistical validation through bootstrapping or permutation testing is essential to distinguish significant interactions from noise. When properly implemented, DCM provides unprecedented insights into how ecological and evolutionary dynamics jointly shape microbiome structure over time, information critical for designing consortia-based bioprocesses or predicting the stability of engineered functions.

Diagram 1: Dynamic Covariance Mapping Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the key steps in applying DCM to infer microbial interaction networks from time-series abundance data.

Multi-Omics Integration for Functional Insights

The integration of multiple omics layers—particularly metagenomics and metabolomics—has become essential for connecting microbial taxonomy to function in complex communities. A comprehensive 2025 benchmarking study evaluated nineteen integrative methods for disentangling relationships between microorganisms and metabolites, addressing key research goals including global associations, data summarization, individual associations, and feature selection [15].

The study revealed that method performance varies significantly depending on the specific research question and data characteristics. For global association testing between microbiome and metabolome datasets, methods like Procrustes analysis, Mantel test, and MMiRKAT showed robust performance. For data summarization and visualization, canonical correlation analysis (CCA), Partial Least Squares (PLS), and MOFA2 effectively captured shared variance. For identifying specific microbe-metabolite relationships, sparse versions of CCA and PLS, along with regularized regression approaches, provided the best balance between sensitivity and specificity [15].

Critical considerations for implementing these integrative approaches include proper handling of compositionality (often through centered log-ratio or isometric log-ratio transformations), accounting for zero-inflation, and addressing multiple testing burdens. The benchmarking study emphasized that no single method performs optimally across all scenarios, recommending that researchers select analytical strategies based on their specific research questions, data types, and study objectives [15].

Table 2: Comparison of Omics Integration Methods for Microbial Biodiversity Studies

| Research Goal | Recommended Methods | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Association Testing | Procrustes analysis, Mantel test, MMiRKAT [15] | Detects overall correlations between datasets; controls false positives | Does not identify specific relationships between individual features |

| Data Summarization | CCA, PLS, MOFA2 [15] | Captures shared variance between omics layers; facilitates visualization | May lack resolution for pinpointing specific microbe-metabolite relationships |

| Individual Association Detection | Sparse CCA, Sparse PLS, LASSO [15] | Identifies specific pairwise relationships with feature selection | Requires careful parameter tuning; challenged by high collinearity |

| Feature Selection | Regularized regression, stability selection [15] | Identifies stable, non-redundant associated features | Selection stability can vary with data characteristics |

Engineering Non-Conventional Microbial Hosts

CRISPR-Cas Systems for Genome Editing

The adaptation of CRISPR-Cas gene editing technology for non-conventional microbes has dramatically accelerated the engineering of novel microbial cell factories. This platform enables precise modifications of microbial genomes, facilitating the development of high-performing strains for drug production and other applications. In microbial strain engineering, CRISPR-Cas systems have demonstrated remarkable efficiency in producing novel compounds and optimizing existing metabolic pathways, resulting in significantly increased yields and reduced production costs [16].

Recent applications have shown particularly promising results in photosynthetic microorganisms, with one research study demonstrating a more than 60% improvement in lipid production by using CRISPR to prevent degradation and hydrolysis of fatty acids from glycerophospholipids without significantly affecting cell growth [16]. This approach illustrates the power of precise genetic interventions for enhancing inherent capabilities of non-conventional hosts, moving beyond the traditional model of importing heterologous pathways into standard platforms.

Implementing CRISPR systems in newly isolated microbes requires careful consideration of several factors: establishing efficient DNA delivery methods, optimizing expression of CRISPR components, validating repair mechanisms, and developing appropriate selection strategies. Success often depends on adapting protocols from related organisms while accounting for the unique cellular physiology and genetic characteristics of each new host.

Cell-Free Expression Systems for Rapid Prototyping

The emergence of advanced cell-free expression systems represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering and host characterization. Platforms such as ALiCE (Arthrobacter lysates for the cell-free expression of proteins) and Sutro's Xpress CF offer distinct advantages for evaluating and engineering biosynthetic pathways from non-conventional hosts without the constraints of cellular growth and maintenance [16].

ALiCE leverages lysates from the Arthrobacter genus to create a robust and cost-effective system for protein expression that offers a broader range of post-translational modifications and native folding conditions compared to traditional cell-free systems. In parallel, Sutro's Xpress CF system provides high-throughput capabilities for rapid screening of various protein constructs and optimization of expression conditions [16]. These platforms enable researchers to rapidly characterize enzymatic activities from unculturable microbes or validate pathway functionality before undertaking the more resource-intensive process of developing full cellular production hosts.

The methodology for implementing cell-free systems typically involves preparing active lysates, optimizing reaction conditions, designing DNA templates for pathway expression, and developing analytical methods for detecting products. These systems are particularly valuable for expressing pathways involving toxic intermediates, testing multiple enzyme variants in combinatorial assemblies, and prototyping metabolic pathways from microbes that are difficult to culture at industrial scales.

Industrial Applications and Bioprocess Considerations

Bioremediation and Environmental Applications

Non-conventional microbes offer powerful capabilities for environmental restoration and pollution mitigation through biological processes. Microbial bioremediation harnesses the natural capabilities of microorganisms to degrade or transform pollutants into less harmful substances, providing a sustainable approach to environmental management [10].

Research led by Assoc. Prof. Dr. Shafinaz Shahir at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia exemplifies this approach, focusing on microbial solutions for arsenic pollution through biosorption using indigenous bacteria from highly contaminated gold mine environments. This work has isolated numerous arsenic-resistant strains—including Bacillus thuringiensis, Pseudomonas stutzeri, and Microbacterium foliorum—that demonstrate remarkable metal-binding capabilities due to functional groups on their cell walls [10]. More recent investigations have explored bacterial nanocellulose from agro-waste as a highly efficient biopolymer for adsorbing heavy metals and dyes, addressing both wastewater pollution and waste valorization.

Key bioremediation strategies employing non-conventional microbes include:

- Natural attenuation: Relies on native microbial communities to break down pollutants without intervention

- Biostimulation: Adds nutrients to stimulate the growth and activity of indigenous microbes

- Bioaugmentation: Introduces specialized microbial strains to enhance remediation capabilities

- Phytoremediation: Utilizes plant-microbe partnerships to clean up contaminants [10]

Single-Use Bioreactors and Process Scale-Up

The transition from laboratory discovery to industrial implementation of non-conventional microbial hosts requires advanced bioprocess technologies that accommodate diverse physiological characteristics. Single-use bioreactors have emerged as particularly valuable tools for process development with non-standard hosts, offering several distinct advantages for working with novel microbial systems [16].

These systems minimize cross-contamination risks, shorten turnaround times between batches, and reduce cleaning validation requirements—particularly beneficial when working with microbes that may produce persistent compounds or biofilms. The flexibility of single-use equipment allows researchers to test multiple strains or conditions in parallel, accelerating the optimization of cultivation parameters for fastidious organisms. Additionally, the ability to use the same equipment in both process development and production facilitates more straightforward scale-up of processes developed with non-conventional hosts [16].

Recent advancements in microbial biologics production and scale-up have revolutionized manufacturing processes, significantly improving efficiency and accessibility. Refinements in fermentation techniques—including optimized culture conditions and innovative bioreactor designs like single-use systems and continuous fermentation—have led to enhanced microbial growth rates and increased production capacities [16]. These developments are particularly important for non-conventional hosts that may have unique aeration, mixing, or feeding requirements compared to traditional platform organisms.

Diagram 2: Non-Conventional Host Development Pipeline. This flowchart outlines the key stages in developing production processes using non-conventional microbial hosts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Biodiversity Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biodiversity Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequencing Kits | Oxford Nanopore ligation sequencing kits; PacBio SMRTbell preparation kits [11] | Generate long-read sequencing data for metagenome-assembled genomes | Enable reconstruction of near-complete genomes from complex samples; require specialized instrumentation |

| Chromosomal Barcoding Systems | Tn7 transposon-based barcoding systems [14] | Track intraspecific clonal dynamics at high resolution | Allow integration of ~500,000 distinct barcodes into microbial populations; essential for DCM studies |

| Cell-Free Expression Components | ALiCE lysates; Sutro Xpress CF reagents [16] | Enable in vitro characterization of metabolic pathways | Provide broader post-translational modification capabilities; useful for toxic pathway elements |

| Culture Media Supplements | Heavy metal solutions; hydrocarbon mixtures; extreme pH buffers [10] | Selective isolation of microbes with specialized capabilities | Critical for enriching microbes from extreme environments with bioremediation potential |

| Process Analytical Technology | In-line sensors for pH, dissolved oxygen, metabolite profiling [16] | Real-time monitoring of microbial cultivation processes | Enable better process control and reduced variability during bioprocess optimization |

The systematic exploration of microbial biodiversity has evolved from a descriptive exercise to a foundational strategy for developing next-generation microbial cell factories. The integration of advanced sequencing technologies, sophisticated computational tools, and innovative engineering approaches has created a robust pipeline for discovering, characterizing, and deploying non-conventional microbial hosts with unique capabilities. As these methodologies continue to mature, we can anticipate several emerging trends that will further accelerate this field.

The convergence of high-resolution omics technologies with machine learning approaches promises to enhance our ability to predict microbial functions from genomic signatures, guiding more targeted isolation efforts. Similarly, the development of more universal genetic toolkits will reduce the barriers to engineering newly isolated microbes. As synthetic biology advances toward whole-genome engineering and de novo genome design, the distinction between model organisms and non-conventional hosts may increasingly blur, with researchers selecting or designing optimal chassis based on functional requirements rather than historical convenience.

The expanding exploration of microbial biodiversity represents not merely an extension of existing biotechnological paradigms but a fundamental reimagining of how we identify and utilize biological resources. By embracing the full phylogenetic and functional diversity of microorganisms, researchers can develop more sustainable, efficient, and innovative bioprocesses that address pressing challenges in human health, environmental sustainability, and industrial manufacturing.

In the development of microbial cell factories (MCFs) for sustainable chemical production, three core metrics—titer, yield, and productivity—serve as the ultimate benchmarks for evaluating bioprocess performance and economic viability [17] [18]. These parameters collectively determine the commercial success of industrial-scale fermentations, influencing decisions from initial strain design to final process scale-up. The optimization of Titer, Rate, and Yield (TRY) is therefore fundamental to achieving cost-competitive biomanufacturing processes for pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and fine chemicals [18].

Titer, defined as the concentration of the product accumulated in the fermentation broth, directly impacts downstream processing costs. Higher titers reduce the volume that needs to be processed, lowering purification expenses. Yield, expressed as the amount of product formed per unit of substrate consumed, dictates raw material efficiency and is crucial for determining the carbon conversion efficiency of a microbial chassis. Productivity, or the rate of product formation per unit volume per unit time, determines the output capacity of bioreactors and thus capital investment requirements [17]. A comprehensive understanding of the TRY framework and the often complex trade-offs between these metrics enables metabolic engineers and industrial microbiologists to design more efficient and economically sustainable bioprocesses.

Defining the Core Metrics

Formal Definitions and Calculations

The three core metrics provide complementary information about bioprocess performance and are mathematically defined as follows:

- Titer: The concentration of the target product in the fermentation broth at the end of the process, typically expressed in grams per liter (g/L) or milligrams per liter (mg/L) [17]. It represents the accumulation capacity of the microbial system.

- Yield: The efficiency of converting a substrate into the desired product. It is calculated as the amount (or moles) of product formed per amount (or moles) of substrate consumed [5]. Common units include g product/g substrate or mol product/mol substrate. Yield can be further categorized into maximum theoretical yield (YT), determined solely by reaction stoichiometry, and maximum achievable yield (YA), which accounts for resources diverted for cellular growth and maintenance [5].

- Productivity: The rate of product formation, measured as the total product formed per unit volume per unit time (e.g., g/L/h) [17] [19]. Also referred to as the rate in the TRY metrics, it reflects the speed of the bioprocess.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Microbial Cell Factories

| Metric | Definition | Typical Units | Primary Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titer | Concentration of product in fermentation broth | g/L, mg/L | Downstream processing costs |

| Yield | Amount of product per amount of substrate consumed | g/g, mol/mol | Raw material costs |

| Productivity | Rate of product formation per unit volume | g/L/h | Capital investment (bioreactor output) |

Interrelationships and Trade-offs

The relationship between titer, yield, and productivity is rarely linear, and engineers frequently face trade-offs when optimizing these parameters [19] [20]. A fundamental challenge lies in the metabolic competition between biomass formation and product synthesis. Microorganisms naturally allocate resources toward growth and maintenance; redirecting metabolic flux toward a non-essential product often occurs at the expense of growth rate and biomass yield [19].

This creates a critical trade-off: strategies that maximize product yield (such as gene knockouts that eliminate competing pathways) may simultaneously reduce the specific growth rate, resulting in lower biomass concentration and consequently reduced volumetric productivity [20]. Similarly, achieving high titers may require extended fermentation times, which can negatively impact productivity. Understanding and managing these trade-offs is essential for developing balanced strain designs and processes.

Computational frameworks like Dynamic Strain Scanning Optimization (DySScO) have been developed to address these challenges by integrating dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA) with strain-design algorithms, enabling the identification of engineered strains that balance all three metrics rather than optimizing for one at the expense of others [20].

Methodologies for Measurement and Analysis

Experimental Protocols for Metric Quantification

Accurate measurement of TRY metrics requires standardized analytical procedures and cultivation methods. The following protocol outlines a general approach for determining these parameters in microbial systems:

1. Cultivation Setup:

- Inoculate a defined production medium with a standardized preculture. For example, in MK-7 production using Bacillus subtilis, an inoculum size of 2.5% (approximately 2 × 10⁶ CFU/mL) is used [21].

- Conduct fermentations under controlled conditions (temperature, pH, aeration). Common cultivation modes include batch, fed-batch, and continuous systems, with fed-batch often achieving the highest titers for many products [17].

2. Sampling and Analytical Procedures:

- Collect periodic samples throughout the fermentation process to monitor cell density (OD₆₀₀), substrate concentration, and product accumulation.

- For intracellular products or complex matrices, implement appropriate extraction methods. For instance, MK-7 extraction involves sonication of the culture broth followed by centrifugation and liquid-liquid extraction using n-hexane and isopropanol [21].

- Quantify product concentration using validated analytical methods such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). In MK-7 analysis, HPLC with a mobile phase of methanol and acetonitrile (1:1) at 254 nm detection provides reliable quantification [21].

3. Data Calculation:

- Titer: Determine the maximum product concentration from the final fermentation sample or time-course data.

- Yield: Calculate as (total product formed)/(total substrate consumed) over the fermentation period.

- Productivity: Compute as (final titer)/(total process time) for volumetric productivity.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for TRY Analysis

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC System | Product quantification and purity assessment | MK-7 analysis with methanol:acetonitrile mobile phase [21] |

| Defined Production Medium | Supports high-yield production with optimized carbon/nitrogen sources | MK-7 production medium with lactose and glycine [21] |

| Extraction Solvents | Product recovery from culture broth | n-Hexane and isopropanol for MK-7 extraction [21] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico prediction of metabolic capacities and theoretical yields | Analysis of 5 microorganisms for 235 chemicals [5] [22] |

| Fed-Batch Bioreactors | High-density cultivation for enhanced titer and productivity | Industry standard for commodities like 1,3-propanediol [17] |

Computational Approaches for Predictive Analysis

Computational tools play an increasingly crucial role in predicting and optimizing TRY metrics before extensive experimental work:

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) mathematically represent gene-protein-reaction associations within microorganisms, enabling in silico predictions of metabolic capabilities [5] [22]. Researchers at KAIST utilized GEMs to evaluate the metabolic capacities of five industrial microorganisms (Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Bacillus subtilis, Corynebacterium glutamicum, and Pseudomonas putida) for producing 235 bio-based chemicals [5] [22]. This approach calculated both maximum theoretical yields (YT) and maximum achievable yields (YA) under industrial conditions, providing valuable criteria for selecting optimal chassis strains for specific target compounds.

Diagram 1: Computational Workflow for TRY Prediction. This workflow integrates GEMs with FBA and dFBA to predict strain performance before experimental validation.

Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA) integrates classical FBA with bioreactor dynamics, enabling prediction of time-dependent metabolite concentrations, biomass levels, and thus titer and productivity profiles [20]. The DySScO strategy leverages dFBA to simulate the performance of engineered strains in silico, allowing researchers to identify designs that balance yield, titer, and productivity before committing to laborious construction and testing [20].

Optimization Strategies for Enhanced Bioprocess Performance

Strain Design and Metabolic Engineering

Improving TRY metrics begins with strategic strain design at the metabolic level:

Growth-Coupling links product synthesis to cellular growth by making product formation essential for biomass production, creating selective pressure that enhances genetic stability and productivity [19]. This can be achieved by:

- Rewiring central metabolism to create synthetic dependencies (e.g., making anthranilate production essential for pyruvate regeneration in E. coli) [19].

- Eliminating native pathways for essential precursor synthesis and replacing them with product-forming routes [19].

Pathway Optimization enhances innate metabolic capacity through:

- Introduction of heterologous reactions: For more than 80% of 235 bio-based chemicals analyzed, fewer than five heterologous reactions were needed to construct functional biosynthetic pathways in host strains [5].

- Cofactor engineering: Systematically exchanging cofactors in native metabolic reactions can increase yields beyond innate metabolic capacities [5] [22].

- Enzyme engineering: Enhancing the activity of key enzymes through protein engineering to eliminate rate-limiting steps [23].

Process Engineering and Cellular Function Maintenance

Beyond genetic modifications, process-level strategies and maintaining cellular viability are crucial for optimizing TRY metrics:

Fermentation Process Control:

- Fed-batch cultivation: This is often the preferred mode for industrial production, allowing control of substrate concentration to avoid catabolite repression or inhibitor accumulation while achieving high cell densities and product titers [17] [19].

- Dynamic regulation: Implementing genetic circuits that respond to cellular or environmental cues to dynamically shift metabolism from growth phase to production phase [19].

Enhancing Cellular Robustness maintains high metabolic activity under industrial conditions:

- Transcription Factor Engineering: Reprogramming global cellular responses through global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) to enhance tolerance to inhibitors, ethanol, and other stresses [24].

- Membrane Engineering: Modifying membrane composition (e.g., increasing unsaturated fatty acid content) to improve tolerance to organic acids and solvents [24].

- Efflux Transporters: Engineering transporters to actively export toxic products from cells, reducing intracellular inhibition [23].

Diagram 2: TRY Optimization Strategy Framework. Interrelationships between optimization approaches and their primary impacts on core metrics.

The systematic evaluation and optimization of titer, yield, and productivity remain fundamental to advancing microbial cell factories for sustainable chemical production. While these metrics sometimes present engineering trade-offs, integrated approaches combining computational modeling, strategic strain design, and bioprocess optimization can successfully balance all three parameters. The continuing development of tools such as genome-scale models, dynamic flux analysis, and robustness engineering provides a powerful toolkit for researchers to overcome historical limitations in biocatalyst performance. As these technologies mature, they promise to accelerate the development of economically viable bioprocesses that can effectively replace petroleum-derived manufacturing across multiple industries.

Principles of Metabolic Capacity and Host Strain Selection

The development of microbial cell factories (MCFs) represents a cornerstone of modern industrial biotechnology, enabling the sustainable production of fuels, pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and a wide range of industrial chemicals [25]. Metabolic capacity refers to the inherent capability of a microbial system to catalyze the biochemical conversions necessary for transforming substrates into valuable target products. This capacity is determined by the organism's genetic blueprint, enzymatic repertoire, and regulatory networks that collectively govern metabolic flux [26] [27]. Within the context of a broader thesis on microbial cell factory development, understanding and optimizing metabolic capacity is fundamental to achieving economically viable bioprocesses. The selection of an appropriate host strain constitutes a critical initial decision that profoundly impacts the entire development pipeline, from laboratory research to industrial-scale production [28] [29].

The strategic importance of host strain selection stems from its far-reaching implications on process economics, regulatory approval pathways, and technical feasibility. As the global recombinant DNA technology market continues its rapid expansion—projected to reach $1.3 trillion by 2030—the systematic evaluation of microbial hosts has become increasingly crucial for maintaining competitive advantage in the bio-based economy [29]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of the principles governing metabolic capacity and host strain selection, offering researchers and scientists a structured framework for making informed decisions in microbial cell factory development.

Fundamental Principles of Metabolic Capacity

Metabolic capacity encompasses the complete set of biochemical transformations that a microorganism can perform, spanning from central carbon metabolism to specialized biosynthetic pathways. This capacity is fundamentally governed by the organism's genetic endowment and the catalytic properties of its enzymatic machinery [26].

Components of Metabolic Capacity

The metabolic capacity of industrial microorganisms comprises several interconnected components:

Native Metabolic Pathways: Innate biochemical routes encoded within the organism's genome that support growth, maintenance, and reproduction [25]. For example, lactic acid bacteria naturally possess the enzymatic machinery for fermenting sugars to lactic acid, while Saccharomyces cerevisiae inherently excels at ethanol production [25].

Heterologous Pathway Integration: Introduced biosynthetic pathways from other organisms that expand the host's biosynthetic capabilities beyond its native metabolism [25]. The successful production of artemisinin in engineered S. cerevisiae exemplifies how heterologous pathway expression can create novel metabolic capacities [25].

Cofactor Balance and Regeneration: The availability and recycling of essential cofactors (NAD(P)H, ATP, acetyl-CoA) that drive thermodynamically unfavorable reactions and maintain redox homeostasis [27].

Regulatory Network Architecture: Genetic regulatory mechanisms that control metabolic flux in response to environmental cues and intracellular metabolic status [30].

Transport Capabilities: Membrane transport systems that mediate the uptake of substrates and secretion of products, often critical for avoiding feedback inhibition and cytotoxic effects [31].

Quantitative Assessment of Metabolic Capacity

Researchers employ diverse methodological approaches to quantitatively evaluate the metabolic capacities of potential host strains. The table below summarizes key analytical techniques and their applications in metabolic capacity assessment.

Table 1: Methodologies for Assessing Metabolic Capacity

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Measured Parameters | Applications in Strain Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Analysis | extracellular flux analyzer, metabolic flux analysis | Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR), Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR), metabolic flux rates | Mapping carbon fate, identifying rate-limiting steps, evaluating pathway efficiency [32] |

| Omics Technologies | Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Lipidomics, Metabolomics | Gene expression levels, protein abundance, lipid profiles, metabolite concentrations | Comprehensive view of metabolic network operation, identification of regulatory bottlenecks [31] |

| Enzyme Activity Assays | Kinetic assays, enzymatic screens | Enzyme specific activity, catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity | Evaluating key pathway enzyme performance, comparing orthologs from different hosts [32] |

| Pathway Activity Profiling | PAPi algorithm | Metabolic pathway activity scores from metabolomic data | Comparative analysis of pathway performance across multiple strains [30] |

| High-Throughput Screening | Luminescence-based ATP assay, fluorescence-based reporters | ATP levels, pathway-specific precursor abundance | Rapid assessment of energy metabolism, screening strain libraries [32] |

Computational Framework for Metabolic Capacity Evaluation

Advanced computational tools have been developed to systematically evaluate the metabolic capacities of potential host strains. The MESSI (Metabolic Engineering target Selection and best Strain Identification) platform represents one such approach that leverages public metabolomic data to calculate metabolic pathway activities and rank S. cerevisiae strains based on user-defined pathways of interest [30]. The computational pipeline involves:

Pathway Activity Calculation: Application of the Pathway Activity Profiling (PAPi) algorithm to metabolomic data, transforming compound concentrations into pathway activity scores [30].

Strain Ranking: Normalization of pathway activity scores and aggregation through Weighted AddScore Fuse or Weighted Borda Fuse algorithms to generate unified strain rankings [30].

Target Identification: Genome-wide association mapping between pathway activities and natural genetic variation to identify potential metabolic engineering targets [30].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for computational assessment of metabolic capacity:

Figure 1: Computational Workflow for Metabolic Capacity Evaluation

Host Strain Selection Criteria

Selecting an optimal host strain requires a multidimensional evaluation framework that balances metabolic capabilities with practical implementation constraints. The following criteria represent critical considerations in host strain selection.

Metabolic and Physiological Attributes

Native Biosynthetic Capability: Strains with inherent capacity for producing the target compound or close structural analogs typically require less extensive metabolic engineering [25]. For example, Escherichia coli's natural ability to synthesize aromatic amino acids makes it a preferred host for derivatives of these pathways [27].

Precursor and Cofactor Availability: The intracellular abundance of key metabolic precursors (acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, phosphoenolpyruvate) and redox cofactors significantly influences pathway performance [27] [29].

Tolerance to Process Conditions: Robustness against inhibitory products, substrate toxicity, osmotic stress, and fermentation inhibitors is essential for achieving high product titers [31]. For instance, styrene toxicity presents a major challenge in bacterial production systems, necessitating the engineering of tolerant chassis [31].

Carbon Source Utilization: The ability to efficiently consume low-cost, renewable feedstocks (e.g., lignocellulosic hydrolysates, glycerol, C1 gases) directly impacts process economics [28] [25].

Genetic and Operational Considerations

Genetic Manipulability: Availability of well-developed molecular tools for precise genetic modifications, including CRISPR systems, expression vectors, and genome-editing platforms [28] [30].

Regulatory Status: Strains designated as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) by regulatory agencies facilitate approval processes for food, feed, and pharmaceutical applications [28] [25].

Fermentation Characteristics: Growth rate, oxygen requirements, foam formation, and morphology affect scalability and process control in industrial bioreactors [28].

Product Secretion Capability: Native capacity for extracellular product secretion simplifies downstream processing and reduces purification costs [28].

Comparative Analysis of Common Industrial Microbes

The table below provides a comparative analysis of frequently used microbial hosts based on key selection criteria.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Industrial Host Strains

| Host Organism | Metabolic Strengths | Genetic Tools | Regulatory Status | Industrial Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Rapid growth, high protein yield, well-characterized metabolism [29] | Extensive toolbox, high transformation efficiency [30] [25] | Non-GRAS, requires containment [28] | Recombinant proteins, organic acids, amino acids [27] [25] | Limited post-translational modifications, endotoxin concerns [29] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Robust industrial physiology, eukaryotic protein processing [30] [25] | Well-developed genetic system [30] | GRAS status [28] [25] | Bioethanol, pharmaceuticals, recombinant proteins [30] [25] | Limited thermotolerance, tendency to ferment [25] |

| Bacillus subtilis | Efficient protein secretion, sporulation capability [25] | Genetic tools available [25] | GRAS status [25] | Industrial enzymes, antibiotics [25] | Complex regulation, competence development [25] |

| Lactic Acid Bacteria | Acid tolerance, diverse carbohydrate utilization [25] | Specialized tools developing [25] | GRAS status [25] | Lactic acid, fermented foods, probiotics [25] | Fastidious growth requirements, limited product range [25] |

| Aspergillus niger | Strong organic acid production, enzyme secretion [25] | Genetic manipulation challenging [25] | GRAS for certain strains [25] | Citric acid, glucoamylase, heterologous proteins [25] | Slow growth, complex morphology [25] |

Computational Tools for Host Strain Selection

Advanced computational resources have been developed to support systematic host strain selection by leveraging multi-omic data and machine learning approaches.

The MESSI Platform for Strain Identification

The Metabolic Engineering target Selection and best Strain Identification (MESSI) tool represents an integrative platform for predicting efficient chassis and regulatory components for yeast-based production [30]. Key functionalities include:

Strain Ranking: Integration of public metabolomic data from characterized S. cerevisiae strains to compute metabolic pathway activities and generate ranked strain lists based on user-defined pathways of interest [30].

Target Identification: Genome-wide association studies linking natural genetic variation with metabolic pathway activities to prioritize genes and variants as potential metabolic engineering targets [30].

Parameter Customization: User-defined parameters including pathway weight and expectation values, aggregation algorithms, and variant filtering criteria [30].

Multi-Omic Based Production Strain Improvement

The MOBpsi (Multi-Omic Based Production Strain Improvement) strategy employs time-resolved systems analyses of fed-batch fermentations to identify strain engineering targets, particularly for challenging production scenarios such as toxic chemical biosynthesis [31]. This approach integrates:

Time-Series Multi-Omic Data: Transcriptomic, proteomic, and lipidomic profiling across fermentation time courses to capture dynamic system responses [31].

Analytical Validation: Correlation of omic data with analytical measurements of substrate consumption, product formation, and byproduct accumulation [31].

Target Prioritization: Identification of genetic interventions that address pathway bottlenecks and product toxicity simultaneously [31].

The application of MOBpsi to E. coli styrene production identified novel engineering targets (ΔaaeA and cpxPo) that resulted in three-fold production increases compared to previous strains [31].

Experimental Protocols for Metabolic Capacity Evaluation

Rigorous experimental validation is essential for confirming computational predictions and empirically characterizing metabolic capacity. The following protocols provide standardized methodologies for key analytical procedures.

Protocol for Analyzing Energy Metabolic Pathway Dependencies

This protocol enables direct measurement of ATP production from different metabolic pathways, providing a quantitative assessment of energy metabolism dependencies [32].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Luminescent ATP Detection Assay Kit | Quantifies ATP concentration via luminescence | Direct measurement of cellular ATP levels after metabolic inhibition [32] |

| Cell Proliferation Kit II (XTT) | Assesses cell viability based on metabolic activity | Normalization of ATP measurements to viable cell count [32] |

| 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose | Glycolysis inhibitor | Blocks glucose utilization to assess glycolytic dependency [32] |

| Oligomycin A | ATP synthase inhibitor | Inhibits oxidative phosphorylation to evaluate mitochondrial dependency [32] |

| Metformin | Complex I inhibitor | Reduces mitochondrial respiration, modeling metabolic disease states [32] |

Experimental Workflow:

Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Harvest exponentially growing HepG2 cells (or target microbial cells adapted to culture conditions)

- Count cells using a hemocytometer with trypan blue exclusion

- Seed cells in white-walled 96-well plates at optimized density (e.g., 10,000 cells/well for HepG2)

- Incubate for 24 hours under standard conditions to ensure adherence and exponential growth [32]

Metabolic Inhibition:

- Prepare fresh inhibitor stocks in appropriate solvents (e.g., DMSO for oligomycin)

- Treat cells with systematic inhibitor combinations:

- No inhibitor baseline control

- Individual pathway inhibitors (2-deoxy-D-glucose for glycolysis, oligomycin for oxidative phosphorylation)

- Combination inhibitors to assess compensatory pathways

- Include metformin treatment condition to model complex I impairment

- Incubate with inhibitors for predetermined duration (typically 4-24 hours) [32]

Viability and ATP Measurement:

- Perform XTT viability assay according to manufacturer specifications:

- Add XTT reagent to designated wells

- Incubate for 1-4 hours at culture conditions

- Measure absorbance at 475-500 nm with reference at 660 nm

- Conduct ATP measurement using luminescent assay:

- Lyse cells with ATP assay buffer

- Add luciferase substrate solution

- Measure luminescence immediately using plate reader [32]

- Perform XTT viability assay according to manufacturer specifications:

Data Analysis and Metabolic Dependency Calculation:

- Normalize ATP values to viability measurements

- Calculate pathway-specific dependencies:

- Glycolytic capacity = (ATP~no inhibitor~ - ATP~oligomycin~) / ATP~no inhibitor~

- Mitochondrial dependency = (ATP~no inhibitor~ - ATP~2-DG~) / ATP~no inhibitor~

- Fatty acid oxidation capacity = (ATP~no inhibitor~ - ATP~etomoxir~) / ATP~no inhibitor~ [32]

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for metabolic pathway analysis:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Multi-Omic Based Production Strain Improvement Protocol

The MOBpsi protocol employs integrated time-resolved multi-omic analyses to identify strain engineering targets for improved production of toxic chemicals [31].

Experimental Workflow:

Fed-Batch Fermentation Design:

- Establish controlled fed-bbatch fermentation with defined feeding strategy

- Implement online monitoring of key parameters (pH, dissolved oxygen, cell density)

- Collect samples at strategic time points across growth and production phases [31]

Multi-Omic Sample Collection:

- Transcriptomics: Collect cell pellets, stabilize RNA, extract using standardized kits

- Proteomics: Harvest cells, perform protein extraction, digestion, and preparation for LC-MS/MS

- Lipidomics: Extract lipids using methyl-tert-butyl ether/methanol system

- Metabolomics: Quench metabolism, extract intracellular metabolites [31]

Analytical Measurements:

- Quantify substrate consumption and product formation via HPLC or GC-MS

- Measure byproduct accumulation and nutrient depletion

- Assess cell viability and morphology throughout fermentation [31]

Data Integration and Target Identification:

- Perform time-series analysis of omic datasets to identify dynamic patterns

- Correlate molecular features with production metrics and toxicity indicators

- Apply statistical and network analyses to prioritize engineering targets

- Validate candidate targets through genetic manipulation and fermentation studies [31]

Advanced Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Metabolic Capacity

Beyond host selection, sophisticated engineering approaches can expand and optimize the metabolic capacities of chosen production strains.

Systems Metabolic Engineering

Systems metabolic engineering integrates traditional metabolic engineering with systems biology, synthetic biology, and evolutionary engineering to develop high-performing microbial cell factories [27] [25]. Key strategies include:

Pathway Optimization: Fine-tuning expression levels of pathway enzymes using promoter engineering, ribosome binding site modification, and gene copy number control [29] [25].

Cofactor Engineering: Regenerating and balancing redox cofactors (NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+) to drive thermodynamically constrained reactions [27].

Transport Engineering: Modifying substrate uptake and product secretion systems to enhance flux and reduce toxicity [31].

Regulatory Network Engineering: Rewiring native regulatory circuits to eliminate feedback inhibition and redirect flux toward target products [30].

Culture Medium Optimization

Culture medium composition directly influences metabolic capacity by affecting nutrient availability, physicochemical environment, and cellular physiology [29]. Smart medium optimization follows a staged approach:

Planning Stage: Identification of nutritional requirements, component interactions, and critical quality attributes [29]

Screening Stage: Application of Design of Experiments (DoE) methodologies to identify significant factors [29]

Modeling Stage: Development of predictive models linking medium composition to performance metrics [29]

Optimization Stage: Model-based identification of optimal medium formulations [29]

Validation Stage: Experimental verification of predicted optima and model refinement [29]

Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches are increasingly employed to accelerate medium optimization, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional factor spaces [29].

The strategic selection of microbial host strains based on comprehensive metabolic capacity assessment represents a critical foundation for successful microbial cell factory development. By integrating computational prediction tools with rigorous experimental validation, researchers can identify optimal chassis organisms that align with both technical requirements and economic constraints. The continued advancement of multi-omic analytics, machine learning approaches, and synthetic biology tools promises to further enhance our ability to evaluate and engineer microbial metabolic capacities, accelerating the development of sustainable bioprocesses for chemical and material production.

As the field progresses, the integration of standardized protocols like those presented herein will enable more systematic comparison across studies and facilitate the development of robust design principles for host strain selection. This structured approach to understanding and leveraging metabolic capacity will be essential for realizing the full potential of microbial cell factories in the global transition toward bio-based manufacturing.

Building Better Factories: Systems Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology Tools

In the development of microbial cell factories, the construction of efficient biosynthetic pathways is a cornerstone for the sustainable production of valuable chemicals, from pharmaceuticals to biofuels. Pathway construction strategies can be broadly categorized into three paradigms: native pathway optimization, which enhances existing metabolic routes within a host; heterologous pathway expression, which imports pathways from other organisms; and de novo pathway design, which creates novel biochemical routes not found in nature using computational tools and enzyme engineering. Framed within the broader context of microbial cell factories research, this guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these methodologies, detailing their principles, applications, and experimental protocols to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to advance the field.

Heterologous Pathway Expression

Heterologous expression involves the recruitment and assembly of genes from foreign organisms into a microbial host to produce a target compound. This approach vastly expands the chemical space accessible to a single, tractable host organism like E. coli or S. cerevisiae.

Core Principle and Workflow

The fundamental principle is the functional transfer of a biosynthetic pathway from a source organism (often difficult to cultivate or engineer) into a microbial chassis optimized for rapid growth and high-yield production. A standard workflow is summarized in the diagram below:

Detailed Experimental Protocol: High-Titer Naringenin Production inE. coli

The following case study on the de novo production of naringenin, a plant polyphenol with anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities, illustrates a step-by-step optimization of a heterologous pathway [33].

Step 1: Selecting the Tyrosine Ammonia-Lyase (TAL)

- Objective: Identify the most efficient TAL enzyme to convert endogenous L-tyrosine to p-coumaric acid.

- Methodology:

- Clone TAL genes from different microbial sources (e.g., Flavobacterium johnsoniae, FjTAL) into an expression vector.

- Transform constructs into different E. coli strains, including a tyrosine-overproducing strain (e.g., M-PAR-121).

- Cultivate strains in shake flasks, induce gene expression, and quantify p-coumaric acid production via HPLC.

- Outcome: The highest production (2.54 g/L) was obtained using FjTAL expressed in the M-PAR-121 strain, which was subsequently used as the platform strain [33].

Step 2: Assembling the Mid-Pathway (4CL and CHS)

- Objective: Extend the pathway from p-coumaric acid to naringenin chalcone by selecting optimal 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL) and chalcone synthase (CHS) enzymes.

- Methodology:

- Express the chosen FjTAL in combination with different 4CL (e.g., from Arabidopsis thaliana, At4CL) and CHS (e.g., from Cucurbita maxima, CmCHS) genes in the M-PAR-121 strain.

- Monitor the production of naringenin chalcone as the intermediate.

- Outcome: The combination of FjTAL, At4CL, and CmCHS yielded the highest naringenin chalcone production (560.2 mg/L) [33].

Step 3: Completing the Pathway (CHI)

- Objective: Identify the most effective chalcone isomerase (CHI) to convert naringenin chalcone into naringenin.

- Methodology:

- Introduce CHI genes from different sources (e.g., Medicago sativa, MsCHI) into the optimized strain from Step 2.

- Perform production experiments in shake flasks with operational optimizations (e.g., varying carbon source concentration and induction time).

- Quantify final naringenin titers.

- Outcome: The strain expressing MsCHI produced 765.9 mg/L of naringenin, the highest de novo titer reported in E. coli at the time of the study [33].

Table 1: Enzyme Combinations for Heterologous Naringenin Production in E. coli [33]

| Pathway Step | Enzyme | Source Organism | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAL (Step 1) | FjTAL | Flavobacterium johnsoniae | 2.54 g/L p-coumaric acid |

| 4CL (Step 2) | At4CL | Arabidopsis thaliana | |

| CHS (Step 2) | CmCHS | Cucurbita maxima | 560.2 mg/L naringenin chalcone |

| CHI (Step 3) | MsCHI | Medicago sativa | 765.9 mg/L naringenin |

De Novo Pathway Design

De novo pathway design moves beyond the imitation of nature to create entirely new biochemical routes using computational tools. This is essential for producing non-natural compounds or optimizing pathways where no natural, high-yield route exists.

Core Principle and Computational Workflow

Tools like novoStoic use Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) to design mass-balanced biochemical networks that convert a source metabolite into a target compound. These networks can seamlessly blend known enzymatic reactions with putative, novel transformations generated by reaction rule operators (e.g., via the rePrime algorithm) [34]. The overall workflow integrates these components:

Technical Deep Dive: The rePrime and novoStoic Framework

rePrime: Reaction Rule Extraction

- Molecular Signature Encoding: Each metabolite in a database is encoded using a molecular signature vector (C_{mi}^\lambda), which concatenates prime number-based attributes for every molecular moiety m of a given size λ [34].

- Rule Generation: For a known reaction, a reaction rule (T_{mr}^\lambda) is derived by calculating the net change in all moieties m between the substrates and products. This rule captures the structural transformation at the reaction center.

novoStoic: De Novo Pathway Optimization

- MILP Formulation: The pathway design is framed as an optimization problem. Key constraints include:

- Mass Balance: Standard stoichiometric balance for all elements.