Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA): A Comprehensive Guide for Predictive Metabolic Engineering and Mutant Strain Design

This article provides a thorough exploration of the Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) framework, a pivotal computational approach in metabolic engineering for predicting mutant strain behavior.

Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA): A Comprehensive Guide for Predictive Metabolic Engineering and Mutant Strain Design

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of the Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) framework, a pivotal computational approach in metabolic engineering for predicting mutant strain behavior. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content spans from foundational principles to advanced applications. It details how MOMA's hypothesis of minimal flux redistribution post-gene knockout offers a more accurate phenotypic prediction compared to optimal growth-based models, enabling the design of microbial cell factories for high-value chemical production. The article further covers methodological implementations, including hybrid algorithms and mixed-integer programming solutions, alongside troubleshooting computational challenges. Finally, it validates MOMA's efficacy through comparative analysis with other strain design approaches and discusses its implications for accelerating therapeutic development and biomanufacturing.

Understanding MOMA: The Foundational Principles of Predictive Metabolic Modeling

FAQs on Predictive Modeling in Metabolic Engineering

Q1: What is Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) and why is it used for mutant strain prediction? MOMA is a computational algorithm used to predict the metabolic flux distribution in mutant strains. When genes are knocked out, microorganisms readjust their metabolic fluxes. MOMA predicts this new state by assuming the cell minimizes the Euclidean distance between the wild-type and mutant flux distributions, providing a more accurate prediction of metabolic behavior after genetic modifications [1].

Q2: What are the common reasons for discrepancies between MOMA predictions and experimental results? Discrepancies often arise from:

- Incomplete Model Annotation: Gaps in knowledge of the full metabolic network or regulatory constraints not captured in the model [1] [2].

- Kinetic Limitations: MOMA and similar constraint-based models often use stoichiometric data but lack enzyme kinetic parameters, which can be major flux determinants [3].

- Measurement Errors: Inaccurate experimental measurements of uptake rates, secretion rates, or biomass composition used to constrain the model [1].

- Unexpected Regulatory Mechanisms: Post-transcriptional or allosteric regulation not accounted for in the genome-scale model [2].

Q3: Which analytical techniques are most critical for validating and refining predictive models? A multi-layered "omics" approach is essential for comprehensive validation.

- Metabolomics: GC-MS or LC-MS to measure intracellular and extracellular metabolite concentrations, providing direct insight into pathway activity [2].

- Fluxomics: ¹³C isotopic labeling experiments coupled with MS to experimentally determine in vivo metabolic reaction fluxes for comparison with model predictions [1].

- Proteomics: Quantifying enzyme abundance levels to identify potential protein-level bottlenecks not predicted by the model [2].

Q4: How can machine learning (ML) complement traditional mechanistic models like MOMA? ML can enhance MOMA by identifying complex, non-linear patterns in large, high-quality datasets that mechanistic models might miss. A hybrid approach uses mechanistic models to pinpoint initial engineering targets and then employs ML, trained on experimental data from designed libraries, to recommend further genetic modifications that significantly improve product titers and productivity [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low Product Titer Despite High Pathway Flux Prediction

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Product or Intermediate Toxicity | - Measure growth inhibition in presence of product/intermediate.- Use microscopy to check for cell membrane damage or morphological changes. | - Implement a product export system.- Engineer host for higher tolerance via adaptive laboratory evolution.- Use in-situ product removal techniques during fermentation [5]. |

| Competing Metabolic Pathways | - Perform gene deletion on suspected competing pathways and measure product yield.- Use ¹³C flux analysis to quantify flux diversion. | - Knock out genes for enzymes in major competing pathways.- Down-regulate competing reactions using CRISPRi or tunable promoters [1]. |

| Insufficient Cofactor or Energy Regeneration | - Measure intracellular levels of key cofactors (e.g., NADPH, ATP).- Analyze transcriptomics/proteomics data for stress responses related to energy depletion. | - Introduce heterologous genes for alternative, higher-energy-yielding pathways.- Engineer enzymes to have altered cofactor specificity (e.g., from NADH to NADPH) [6]. |

Problem: Discrepancy Between In Silico MOMA Prediction and Measured Metabolic Flux

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Biomass Objective Function | - Experimentally determine the biomass composition (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, DNA/RNA) of your specific strain and growth condition. | - Refine the model's biomass equation based on experimental data to more accurately represent the host's metabolic objectives [1]. |

| Inaccurate ATP Maintenance (ATP_m) Value | - Perform chemostat experiments at different dilution rates to measure maintenance energy requirements. | - Re-calculate the ATP_m coefficient for your strain and condition, and update this constraint in the model [1]. |

| Missing or Incorrect Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Associations | - Use gene essentiality studies to validate GPR rules.- Perform enzyme assays to confirm annotated reaction catalysis. | - Manually curate the model based on new literature or experimental evidence to ensure GPR associations are correct and complete [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation and Refinement

Protocol 1: ¹³C Metabolic Flux Analysis (¹³C-MFA) for Experimental Flux Determination

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the in vivo rates of metabolic reactions in a central metabolic network for direct comparison with MOMA predictions [1].

Materials:

- Defined minimal medium with a single carbon source (e.g., [U-¹³C] glucose).

- Bioreactor or controlled fermentation system.

- Sampling setup (syringes, filters, quenching solution).

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) system.

- Software for flux estimation (e.g., INCA, OpenFlux).

Methodology:

- Culture Growth: Grow the engineered strain in a bioreactor with the ¹³C-labeled carbon source until mid-exponential phase.

- Rapid Metabolite Quenching: Rapidly extract samples and quench metabolism immediately using cold methanol or similar solution to capture intracellular metabolite states.

- Metabolite Extraction and Derivatization: Extract intracellular metabolites and derivative them for GC-MS analysis (e.g., silylation for amino acids and organic acids).

- GC-MS Measurement: Analyze the derivatized samples via GC-MS to determine the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of proteinogenic amino acids and other intermediates.

- Flux Calculation: Input the measured MIDs, extracellular uptake/secretion rates, and biomass composition into flux analysis software. The software uses an iterative algorithm to find the flux map that best fits the experimental labeling data.

Protocol 2: Biosensor-Based High-Throughput Screening for Pathway Optimization

Purpose: To rapidly screen thousands of microbial variants for improved production of a target metabolite, enabling efficient strain optimization and generation of data for machine learning models [4] [2].

Materials:

- Library of engineered microbial variants (e.g., with promoter/RNA regulator libraries).

- Microtiter plates (96 or 384-well).

- Fluorescent reporter protein (e.g., GFP).

- Plate reader with fluorescence and OD600 measurement capabilities.

- FACS sorter (if using a FACS-based biosensor).

Methodology:

- Biosensor Integration: Incorporate a genetically encoded biosensor into your host strain. This biosensor should consist of a transcription factor or RNA aptamer that specifically binds the target metabolite, linked to the expression of a fluorescent reporter gene.

- Library Transformation: Transform the library of genetic variants (e.g., pathway enzyme mutants, regulatory parts) into the biosensor-equipped strain.

- Cultivation and Screening: Grow the variants in microtiter plates under production conditions.

- Fluorescence Measurement: Use a plate reader to measure the optical density (cell growth) and fluorescence intensity (correlated to product titer) for each variant.

- Hit Selection: Isolate variants exhibiting the highest fluorescence-to-OD600 ratio for further validation in shake-flask or bioreactor experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational frameworks containing all known metabolic reactions in an organism. Used for in silico prediction of knockout/overexpression effects and for MOMA simulations [1]. | Identifying gene knockout targets for overproduction of succinate in E. coli. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing System | Enables precise, multiplexable gene knockouts, knock-ins, and regulatory element fine-tuning [2]. | Simultaneously knocking out three competing pathways in S. cerevisiae. |

| Fluorescent Biosensors | Provide a high-throughput, real-time readout of intracellular metabolite levels, linking production directly to a fluorescent signal for easy screening [4] [2]. | Screening a library of enzyme variants to identify those that increase tryptophan production in yeast. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Robust analytical platform for separating, identifying, and quantifying metabolites. Essential for ¹³C-MFA and metabolomics [1] [2]. | Measuring the mass isotopomer distribution of metabolites for experimental flux determination. |

| Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) | Allows rapid, targeted diversification of multiple genomic locations simultaneously in a single microbial population, accelerating the DBTL cycle [2]. | Generating a diverse library of promoter strengths for a 5-gene pathway in E. coli. |

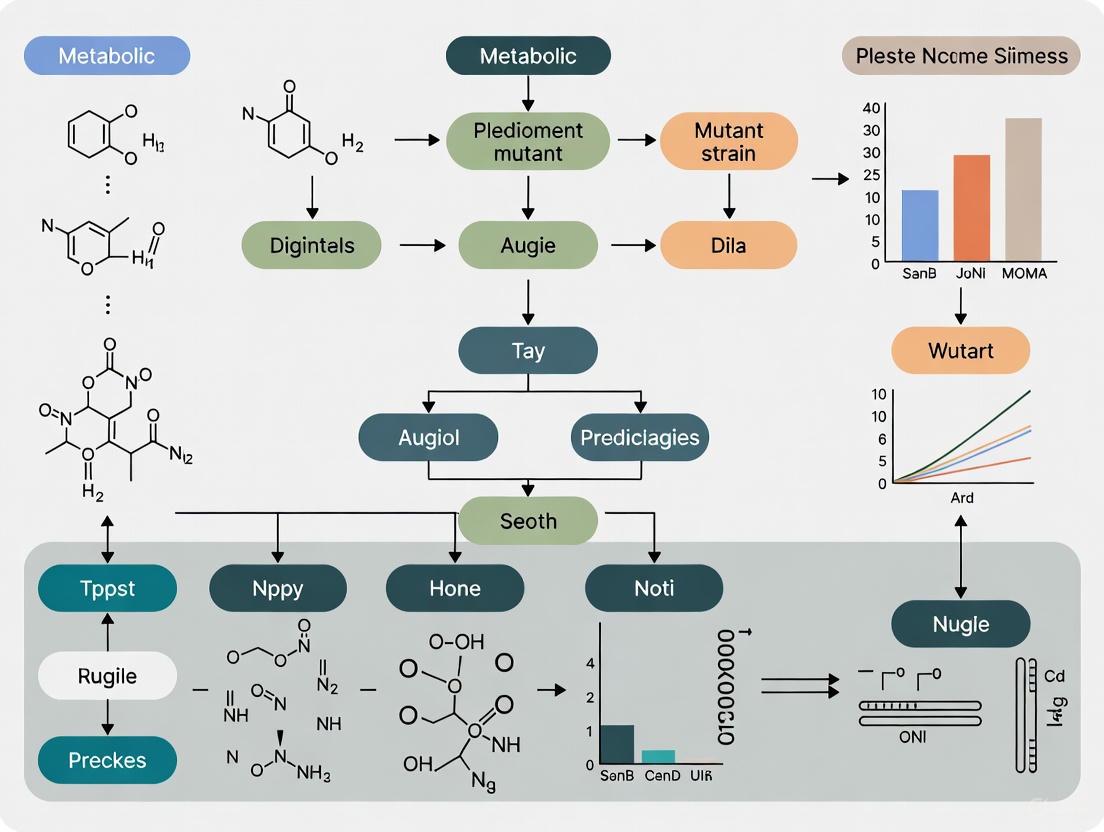

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram Title: MOMA Model Validation and Refinement Cycle

Diagram Title: Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle in Metabolic Engineering

Diagram Title: Combining MOMA and Machine Learning

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core hypothesis of MOMA? MOMA (Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment) operates on the hypothesis that following a genetic perturbation, such as a gene knockout, a mutant strain does not immediately reach a new optimal growth state as predicted by traditional Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). Instead, it posits that the cell's metabolic network undergoes minimal redistribution of metabolic fluxes relative to the wild-type state [7] [8]. The immediate physiological response is to find a feasible flux distribution that is closest to the pre-perterbation state, thus "minimizing metabolic adjustment" [8].

Q2: How does MOMA's prediction differ from FBA for knockout mutants?

FBA assumes that the mutant will re-optimize its metabolism for maximal growth, which can be inaccurate for unevolved mutants. In contrast, MOMA predicts a suboptimal growth state where the flux distribution has the shortest Euclidean distance to the wild-type flux distribution [7] [8]. This often results in more accurate predictions of metabolic behavior for unevolved mutants, such as reduced growth and glucose uptake rates, and the secretion of different byproducts (e.g., pyruvate instead of acetate in a Δpta E. coli mutant) [7].

Q3: What are the different computational variants of MOMA?

The MOMA implementation in tools like psamm.moma provides four main variants for solving the problem [8]:

lin_moma(wt_fluxes): Minimizes the sum of absolute values of flux changes (Linear Programming).lin_moma2(objective, wt_obj): A linear variant that incorporates a wild-type objective flux value.moma(wt_fluxes): Minimizes the Euclidean distance of flux changes (Quadratic Programming).moma2(objective, wt_obj): A quadratic variant that uses a wild-type objective flux value.

Q4: When should I use MOMA over other constraint-based methods? MOMA is particularly well-suited for predicting the phenotype of unevolved gene knockout mutants [7]. Methods like RELATCH suggest that for strains that have undergone adaptive laboratory evolution and are therefore adapted to their new constraints, other methods with relaxed parameters may provide more accurate predictions [7]. For predicting optimal growth states, FBA is more appropriate.

Q5: My MOMA prediction shows no feasible solution for a knockout. What could be wrong?

This often indicates that the gene knockout is lethal under the specified growth conditions. The first step is to verify the model's consistency. Use FBA to simulate the knockout; if FBA also predicts zero growth, this confirms the model's prediction of lethality. If FBA predicts growth but MOMA does not, check the quality and completeness of the reference wild-type flux distribution (wt_fluxes). Ensure that the wild-type flux state provided is a valid and feasible solution for the wild-type model [8].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Error Scenarios and Resolutions

| Issue Description | Possible Causes | Recommended Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| No feasible solution found [8] | Lethal gene knockout, inaccurate wild-type flux reference, or incorrect model constraints. | 1. Use FBA to test knockout lethality.2. Verify the wild-type flux map is physiologically realistic.3. Re-check and relax necessary exchange reaction constraints. |

| Predicted growth rate is zero, but experiments show growth | Missing bypass pathways or regulatory flexibility not captured in the model. | 1. Check for and annotate all isozymes or non-standard metabolic routes.2. Consider using a more comprehensive model or an approach like RELATCH that can account for latent pathway activation [7]. |

| Large quantitative inaccuracies in predicted vs. measured fluxes | Over-reliance on a single, potentially arbitrary, FBA solution for the wild-type reference. | 1. Use get_minimal_fba_flux(objective) to obtain a unique, non-arbitrary wild-type flux distribution for MOMA [8].2. Integrate experimental data (e.g., 13C-MFA, gene expression) to create a more accurate reference flux state [7]. |

| Solver performance issues with quadratic (QP) formulation | The QP problem (moma, moma2) is computationally more intensive than LP. |

1. Switch to a linear MOMA variant (lin_moma, lin_moma2).2. Ensure your solver is configured correctly and supports the problem type. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing MOMA for Mutant Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps to predict the flux distribution of a gene knockout mutant using the psamm.moma Python library [8].

1. Define the Wild-Type Model and Objective:

- Load your genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., in YAML or JSON format).

- Define the objective reaction, typically biomass production.

2. Obtain the Wild-Type Flux Distribution:

- Solve the wild-type model using FBA to get a reference flux distribution.

- For a more robust reference, calculate the flux distribution that minimizes total flux while maintaining optimal growth:

3. Define the Genetic Perturbation:

- Apply the gene knockout constraint to the model. This typically involves setting the bounds of the associated reaction(s) to zero.

4. Solve the MOMA Problem:

- Choose an appropriate MOMA variant and solve for the mutant fluxes.

5. Validate Predictions:

- Compare the predicted growth rate and key exchange fluxes (e.g., substrate uptake, byproduct secretion) against experimental measurements.

- Use statistical measures like Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) per flux or Pearson's correlation coefficient to quantitatively assess the prediction accuracy [7].

Workflow and Logic Diagrams

MOMA Core Workflow

MOMA Variants and Selection Logic

| Item Name | Function / Description | Relevance to MOMA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (e.g., iJO1366 [9], iAF1260 [7]) | A computational representation of an organism's metabolism. Serves as the core framework for all MOMA simulations. | Essential. The accuracy and completeness of the model directly determine the biological relevance of MOMA predictions. |

Wild-Type Flux Data (wt_fluxes) |

A dictionary of flux values for the wild-type strain. Can be obtained from FBA or, preferably, integrated from experimental data like 13C-MFA [7]. | Critical Input. This is the reference state from which minimal adjustment is calculated. Using experimentally determined fluxes greatly improves prediction accuracy [7]. |

| LP/QP Solver (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi) | Software libraries that perform the numerical optimization required to solve the MOMA problem [8]. | Essential. Must be compatible with the chosen modeling environment (e.g., psamm [8]) and capable of handling the specific problem type (Linear or Quadratic Programming). |

| Gene Expression Data (e.g., RNA-Seq) | Transcriptomic data from the wild-type strain under reference conditions. | Highly Useful. While not required for basic MOMA, it can be used to refine the reference flux map or enzyme contribution constraints, as done in advanced methods like RELATCH [7]. |

| psamm.moma Python Library [8] | A specific implementation of the MOMA algorithm within the PSAMM modeling package. | A key tool. Provides the functions (moma(), lin_moma(), etc.) to set up and solve the MOMA problem programmatically. |

Contrasting MOMA with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and Optimal Growth Principles

FBA (Flux Balance Analysis) is a constraint-based method that predicts metabolic fluxes by assuming the network has evolved to achieve optimal biological performance, most commonly by maximizing biomass production or ATP yield [10]. It uses stoichiometric, thermodynamic, and flux capacity constraints to define the possible space of flux distributions, then identifies the specific flux distribution that optimizes a cellular objective [10].

MOMA (Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment) provides an alternative approach by relaxing the optimal growth assumption for mutants [11]. Instead of maximizing biomass, MOMA finds a sub-optimal flux distribution that is nearest to the unperturbed wild-type state using Euclidean distance, effectively minimizing the redistribution of metabolic fluxes after genetic perturbation [11] [12].

ROOM (Regulatory On/Off Minimization), another related algorithm, uses a different norm than MOMA. It minimizes the total number of significant flux changes from the wild-type flux distribution rather than the Euclidean distance [10]. This approach implicitly favors solutions with higher growth rates than MOMA while still maintaining proximity to the wild-type state [10].

Table: Core Algorithm Comparison

| Feature | FBA | MOMA | ROOM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Maximize biomass/growth yield [10] | Minimize Euclidean distance from wild-type fluxes [11] | Minimize number of significant flux changes [10] |

| Underlying Assumption | Optimality: cells operate at maximal growth efficiency [10] | Minimal adjustment: mutant flux distributions are closest to wild-type [11] | Regulatory efficiency: cells minimize significant regulatory changes [10] |

| Mathematical Formulation | Linear Programming (LP) | Quadratic Programming (QP) [11] | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) or Linear Programming [10] |

| Typical Application | Wild-type cells, evolved mutants [10] | Initial transient state after gene knockout [10] | Steady-state after gene knockout [10] |

| Growth Rate Prediction | Higher steady-state growth rates [10] | Lower initial transient growth rates [10] | Near-optimal final growth rates [10] |

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Formulations

FBA Mathematical Framework

FBA is formulated as a linear programming problem: Maximize: ( c^T \cdot v ) (typically biomass reaction) Subject to: ( S \cdot v = 0 ) (mass balance) ( v{min} \leq v \leq v{max} ) (flux capacity constraints)

Where ( S ) is the stoichiometric matrix, ( v ) is the flux vector, and ( c ) is the objective vector [10].

MOMA Mathematical Framework

MOMA solves a quadratic programming problem: [ \min\ ||\mathbf{vw} - \mathbf{vd}||^2 \qquad s.t.\quad \mathbf{S}\cdot\mathbf{vd}=0 ] which simplifies to: [ \min\ \frac{1}{2}\,{\mathbf{vd}}^T\,\mathbf{I}\,\mathbf{vd} + (\mathbf{-vw})\cdot\mathbf{vd} \qquad s.t.\quad \mathbf{S}\cdot\mathbf{vd}=0 ]

Where ( \mathbf{vw} ) represents the wild-type flux distribution and ( \mathbf{vd} ) represents the deletion strain flux distribution to be solved for [11].

Linear MOMA Variant

A linear programming variant of MOMA minimizes the sum of absolute differences rather than Euclidean distance: [ \min \sum |v{wt} - v{del}| ] Subject to: [ S{wt}v{wt} = 0 ] [ lb{wt} \leq v{wt} \leq ub{wt} ] [ c{wt}^T v{wt} = f{wt} ] [ S{del}v{del} = 0 ] [ lb{del} \leq v{del} \leq ub_{del} ] [13]

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol: Performing Standard MOMA Analysis

Wild-Type Flux Determination: First, calculate the wild-type flux distribution (( v_{wt} )) using FBA by maximizing biomass production [12].

Model Perturbation: Constrain the reaction flux(es) corresponding to the gene knockout(s) to zero.

MOMA Optimization: Solve the quadratic optimization problem to find the flux distribution (( v_{mut} )) that minimizes the Euclidean distance to the wild-type flux while satisfying all stoichiometric constraints [11] [12].

Solution Extraction: Extract and analyze the resulting flux distribution, growth rate, and specific pathway fluxes for biological interpretation.

Validation: Compare predictions with experimental growth data or gene expression measurements when available.

Protocol: Linear MOMA Implementation

Wild-Type Reference: Obtain wild-type FBA solution or use experimentally determined flux distribution [12].

Perturbation Application: Implement gene knockout constraints in the mutant model.

Linear Optimization: Solve the linear MOMA problem minimizing the sum of absolute flux changes [13].

Flux Analysis: Examine the resulting flux distribution for biological insights.

MOMA Analysis Workflow

Performance Comparison and Validation Data

Predictive Accuracy for Genetic Interactions

A comprehensive 2019 study evaluated the performance of FBA and MOMA in predicting experimentally observed epistatic interactions in yeast [14]. The results revealed significant limitations:

- For negative epistatic interactions, at 45% precision, FBA/MOMA achieved only 2.8% recall

- For positive epistatic interactions, the methods reached 12.9% recall at approximately 10% precision

- More than two-thirds of experimentally observed epistatic interactions were not detected by any constraint-based method [14]

Table: Experimental Validation of Epistasis Predictions

| Performance Metric | Negative Epistasis | Positive Epistasis |

|---|---|---|

| Recall (percentage of observed interactions correctly predicted) | 2.8% [14] | 12.9% [14] |

| Precision (percentage of predicted interactions that are experimentally observed) | 45% [14] | ~10% [14] |

| Undetected Interactions | >66% of experimentally observed interactions [14] | >66% of experimentally observed interactions [14] |

| Major Limiting Factors | Ignores protein costs, enzyme kinetics, molecular crowding [14] | Ignores protein costs, enzyme kinetics, molecular crowding [14] |

Growth Rate Predictions Across Algorithms

Comparative studies have demonstrated distinct patterns in growth rate predictions:

- FBA predicts higher steady-state growth rates, reflecting optimal performance after adaptation [10]

- MOMA accurately predicts initial transient growth rates observed immediately after perturbation [10]

- ROOM predicts final steady-state growth rates closer to FBA solutions while maintaining realistic flux distributions [10]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: When should I use MOMA instead of FBA for mutant strain prediction?

Use MOMA when modeling the immediate metabolic response to genetic perturbations, before regulatory reconfiguration has occurred. This is particularly relevant for:

- Predicting initial phenotype after gene knockout before adaptive evolution [10]

- Simulating transient states where optimal growth hasn't been restored [10]

- Cases where experimental data shows suboptimal growth in knockout strains [11]

Use FBA when predicting long-term adapted states where optimal growth is expected, or for wild-type cells under standard conditions [10].

FAQ 2: Why does MOMA sometimes predict unrealistic flux distributions with simultaneous flow in opposing directions at branch points?

This occurs because MOMA's Euclidean distance metric favors numerous small flux changes over a few large changes, which can result in non-linear flow patterns [10]. Solution approaches include:

- Using ROOM instead, which minimizes significant flux changes and promotes linear flow [10]

- Applying flux linearity constraints to enforce biologically realistic directional flow at branch points

- Using linear MOMA which minimizes absolute changes rather than Euclidean distance [13]

FAQ 3: How can I improve the poor recall rates of MOMA and FBA for predicting genetic interactions?

The low prediction accuracy (only 20% of negative and 10% of positive interactions confirmed experimentally) stems from fundamental limitations [14]. Consider:

- Incorporating molecular crowding constraints that account for enzyme kinetics and cellular space limitations [14]

- Including protein allocation costs that represent investment of cellular resources

- Using kinetic models where parameter information is available

- Combining predictions with machine learning approaches that integrate additional genomic features

FAQ 4: My MOMA solution shows unexpectedly low growth - is this correct?

Yes, this is expected behavior. MOMA specifically predicts suboptimal growth states immediately following genetic perturbations, before regulatory adaptation occurs [10] [11]. The low growth prediction reflects the metabolic imbalance before the cell has reconfigured its regulatory network to optimize performance under the new constraints.

FAQ 5: How do I handle multiple optimal FBA solutions for the wild-type reference in MOMA?

The non-uniqueness of FBA solutions can significantly impact MOMA results [14]. Address this by:

- Using the lin_moma2() or moma2() functions that explicitly handle this redundancy [12]

- Implementing flux minimization after FBA to find a unique reference solution [12]

- Using experimentally determined flux distributions as reference when available [11]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for MOMA Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based MOMA implementation | Provides MOMA() and linearMOMA() functions for strain prediction [13] |

| PSAMM | Standalone metabolic modeling package | Includes moma(), moma2(), lin_moma(), and lin_moma2() variants [12] |

| OpenMOMA | Open-source reference implementation | Quadratic programming solution for minimal flux adjustment [11] |

| Stoichiometric Models | Network structure and constraints | Organism-specific models (e.g., S. cerevisiae, E. coli) with gene-reaction associations [10] |

Metabolic Network Response to Gene Knockouts

The contrast between MOMA and FBA represents a fundamental dichotomy in constraint-based modeling: immediate suboptimal response versus long-term optimized performance. While FBA successfully predicts final adapted states, MOMA more accurately captures the initial physiological reality following genetic perturbations [10].

Future methodological improvements should address current limitations, particularly the incorporation of enzyme kinetics, protein costs, and spatial constraints to better explain experimental epistasis data [14]. The development of multi-scale models that integrate regulatory constraints with metabolic networks shows particular promise for bridging the gap between current predictions and experimental observations.

For researchers, the choice between MOMA and FBA should be guided by the specific biological question: use MOMA for immediate post-perturbation states and FBA for fully adapted systems, recognizing that ROOM may provide an effective compromise for predicting steady-state fluxes in mutants [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting MOMA Simulations

Problem 1: MOMA simulation fails to find a solution.

- Potential Cause 1: The model is missing critical reactions required for the knockout strain's survival, creating network gaps.

- Solution: Perform a network gap-filling procedure. Use a tool like

gapseq, which employs a Linear Programming (LP)-based gap-filling algorithm to identify and resolve gaps to enable basic metabolic functions, making the model viable for simulation [15]. - Potential Cause 2: The imposed constraints are too restrictive, making the solution space infeasible.

- Solution: Re-examine the environmental constraints (e.g., substrate uptake rates) and the wild-type flux values used as a reference. Gradually relax bounds to identify the conflicting constraint.

Problem 2: MOMA predictions contradict experimental growth data.

- Potential Cause 1: The underlying Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) has incorrect Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations or is missing regulatory information.

- Solution: Manually curate the GPR rules for the reactions surrounding the knockout. For regulatory effects, consider using methods like regulatory FBA (rFBA) or Chemical Organization Theory, which can integrate regulatory constraints with the metabolic network [16] [17].

- Potential Cause 2: The model's biomass objective function is not representative of the actual experimental conditions.

- Solution: Review and adjust the biomass composition (e.g., macromolecular ratios) to reflect the specific strain and growth environment used in your wet-lab experiments.

Problem 3: High computational cost or long solve times for large-scale models.

- Potential Cause: Quadratic MOMA problems are computationally more intensive than their linear counterparts.

- Solution: For an initial analysis, use the linear MOMA (lin_moma) formulation, which minimizes the sum of absolute differences rather than Euclidean distance, to obtain a faster solution [18].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting General Phenotype Predictions

Problem: Low accuracy in predicting gene essentiality.

- Potential Cause: The model does not account for alternative pathways or isozymes that can compensate for the lost gene function.

- Solution: A study assessing the reliability of yeast GEMs found that accuracy for predicting gene knockout phenotypes did not exceed 30% with standard methods [19]. To improve this, systematically check and update GPR rules to include all known isozymes and alternative metabolic routes present in the organism.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between FBA and MOMA? A1: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) assumes natural selection has led to optimal metabolic performance (e.g., maximal growth rate). In contrast, Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) assumes that after a gene knockout, the network undergoes minimal redistribution from the wild-type flux state, which is often a better predictor of the immediate post-perturbation phenotype [18] [20].

Q2: When should I use linear MOMA versus quadratic MOMA?

A2: The choice depends on the biological context and computational resources. Quadratic MOMA ( moma() ) minimizes the Euclidean distance, which is a more natural distance metric but is computationally more demanding. Linear MOMA ( lin_moma() ) minimizes the sum of absolute values, which can be faster and may be preferable for large models or high-throughput screening [18].

Q3: My research aims to overproduce a metabolite. Can MOMA help with this? A3: Yes. MOMA can be integrated with optimization algorithms to identify beneficial gene knockouts. For example, a hybrid of the Artificial Bee Colony algorithm and MOMA (ABCMOMA) has been successfully used to predict gene knockouts in E. coli that optimize the production of succinate and lactate, outperforming previous efforts [9].

Q4: How reliable are genome-scale models for predicting knockout phenotypes? A4: The reliability varies significantly with the quality of the model. A study on yeast models showed that even with advanced simulation methods like MOMA, the accuracy for predicting in vivo phenotypes from single-gene deletions can be low (under 30%) [19]. This highlights the importance of continuous model curation and integration of experimental data to improve predictive power.

Q5: What are "synthetic rescues" in metabolic networks? A5: A synthetic rescue occurs when the deletion of one gene restores the function of a network disrupted by the deletion of another, different gene. This counterintuitive phenomenon, where a second knockout improves network performance, can be predicted using metabolic network analysis and has implications for designing multi-drug therapies that select against resistance [21].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for MOMA-based Prediction of Knockout Phenotypes

This protocol details the steps to predict the phenotypic outcome of a gene knockout using MOMA.

1. Model Preparation:

- Obtain a high-quality, genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) for your organism (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli or Yeast8 for S. cerevisiae).

- Ensure the model is capable of simulating growth under your desired experimental conditions (e.g., minimal glucose medium). Validate the wild-type model against known growth phenotypes.

2. Wild-Type Flux Calculation:

- Perform a Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) on the wild-type model to find the reference flux distribution (

v_wt). - Method: Use the

solve_fba(objective)function in PSAMM or a similar COBRA Toolbox function to maximize for biomass [18]. - Optional: For a more unique reference state, use Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) or find the wild-type flux distribution that minimizes the total flux (

get_minimal_fba_fluxin PSAMM) [18].

3. Implement Gene Knockout:

- Genetically constrain the model by setting the flux through reactions catalyzed exclusively by the target gene to zero.

4. Solve the MOMA Problem:

- Apply the MOMA algorithm to find the flux distribution in the knockout strain (

v_ko) that is closest to the wild-type profile (v_wt). - Method: Use the

moma(wt_fluxes)orlin_moma(wt_fluxes)command, passing the wild-type fluxes from Step 2 [18].

5. Analyze Results:

- The primary output is the predicted growth rate (flux through the biomass reaction) for the knockout strain.

- Compare the

v_kodistribution tov_wtto understand the metabolic rerouting. - Validation: Compare the predicted growth phenotype (viable/lethal) and key secretion product profiles with experimental data.

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

Protocol 2: Workflow for Integrating MOMA in a Strain Optimization Algorithm (e.g., ABCMOMA)

This protocol outlines how MOMA can be embedded within a larger optimization framework for metabolic engineering, as demonstrated with the ABCMOMA hybrid [9].

1. Problem Formulation:

- Define the objective: Maximize the production rate of a target metabolite (e.g., succinate).

- Define the constraints: Maintain a non-zero growth rate and specify the maximum number of gene knockouts allowed.

2. Optimization Loop (Artificial Bee Colony):

- Initialization: Generate a population of candidate solutions (each solution is a set of proposed gene knockouts).

- Evaluation (Fitness Function): For each candidate knockout set:

- a. Apply the knockouts to the model.

- b. Solve the resulting network using MOMA to predict the production rate and growth rate.

- c. Calculate a fitness score based on these outputs (e.g., high production with viable growth).

- Search Iteration: The ABC algorithm uses employed bees, onlooker bees, and scout bees to generate new candidate solutions based on the fitness of existing ones, exploring the combinatorial space of possible knockouts.

3. Solution Output:

- After a stopping criterion is met (e.g., number of iterations), the algorithm returns the optimal set of gene knockouts predicted to maximize the target product.

The following diagram illustrates the ABCMOMA workflow:

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of MOMA Formulations and Applications

| Method | Objective Function | Key Feature | Best Use Case | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Quadratic MOMA (moma) [18] |

Minimize ∑(vwt - vko)² | Uses Euclidean distance; more accurate but computationally intensive. | Predicting immediate metabolic response after knockout. | Predicting growth defects in E. coli knockouts. |

Linear MOMA (lin_moma) [18] |

Minimize ∑|vwt - vko| | Uses linear programming; faster than quadratic MOMA. | High-throughput screening of knockout candidates in large models. | Initial screening for lethal gene knockouts in yeast. |

| ABCMOMA Hybrid [9] | Maximize product yield using MOMA within ABC. | Combines global optimization (ABC) with phenotypic prediction (MOMA). | Metabolic engineering for chemical overproduction. | Optimizing succinate and lactate production in E. coli. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential computational tools and databases for metabolic modeling and MOMA research.

| Item Name | Type | Function | Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSAMM | Software Toolbox | An open-source tool for metabolic model analysis, includes a documented Python API for running MOMA simulations. [18] | https://psamm.readthedocs.io/ |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Toolbox | A widely used MATLAB suite for constraint-based modeling, includes implementations of MOMA and other algorithms. [20] | https://opencobra.github.io/cobratoolbox/ |

| gapseq | Software Tool | An automated tool for predicting metabolic pathways and reconstructing accurate metabolic models, includes advanced gap-filling. [15] | https://github.com/jotech/gapseq |

| BiGG Models | Knowledgebase | A database of curated, genome-scale metabolic models that are high-quality and ready for simulation. [22] | http://bigg.ucsd.edu/ |

| ModelSEED | Web Resource | An online platform for the automated reconstruction, analysis, and curation of genome-scale metabolic models. [22] [15] | https://modelseed.org/ |

| E. coli iML1515 | Metabolic Model | A high-quality GEM of E. coli K-12 MG1655, containing 1515 genes. Serves as a reference for prokaryotic studies. [23] | BiGG Database |

| Yeast 7 | Metabolic Model | A consensus, multi-compartmental GEM of S. cerevisiae. Continuously updated and curated by the community. [23] | https://yeast.sourceforge.net/ |

The Cybernetic View of Metabolism as an Optimal Dynamic Response

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental premise of a cybernetic view of metabolism? The cybernetic framework views metabolic regulation as a goal-oriented control system where cells dynamically adjust enzyme levels and activities to optimize specific objectives, such as growth rate, survival, or response to environmental stimuli. This approach indirectly accounts for complex, often unknown, regulatory processes by introducing cybernetic control variables for enzyme induction (ui) and activation (vi) to modulate metabolic flux toward an optimal state, effectively treating the cell as if it were engineered to maximize a return on investment like biomass production or, in the case of inflammatory response, the production of specific signaling molecules [24].

Q2: How does MOMA differ from FBA in predicting mutant strain behavior? Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) are both constraint-based modeling approaches but operate on different principles. FBA identifies a flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes a specific cellular objective (e.g., biomass yield). In contrast, MOMA finds a flux distribution for a mutant strain that is closest to the wild-type flux distribution, minimizing the extent of metabolic rearrangement required after a genetic perturbation. While FBA often accurately predicts adapted steady-states, MOMA is better suited for predicting the initial transient state immediately after a gene knockout, where large-scale regulatory changes have not yet occurred [10].

Q3: What are the practical differences between quadratic and linear MOMA implementations? The primary difference lies in the objective function used to minimize the distance from the wild-type flux distribution.

- Quadratic MOMA: Minimizes the Euclidean norm (sum of squared differences) between wild-type and mutant fluxes. This approach tends to favor numerous small flux changes over a few large ones [13] [12].

- Linear MOMA: Minimizes the sum of absolute differences between wild-type and mutant fluxes. This method is less restrictive on large changes in individual fluxes and can more easily identify solutions where flux is rerouted through short alternative pathways, such as isoenzymes [13] [10].

Q4: When should I use ROOM instead of MOMA? Regulatory On/Off Minimization (ROOM) is used when predicting the final, adapted steady-state of a mutant strain after regulatory adjustments have occurred. Unlike MOMA, which minimizes the Euclidean distance of all flux changes, ROOM minimizes the number of significant flux changes from the wild-type state. It operates on a more Boolean principle, assuming a fixed cost for each regulatory change regardless of magnitude. ROOM predictions often result in flux distributions with high growth rates, closely matching those predicted by FBA, but with a flux map that is more consistent with experimental observations of adapted strains [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Prediction of Mutant Phenotypes

Problem: Your MOMA or ROOM simulation fails to accurately predict experimentally measured growth rates or essentiality in knockout strains.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Inaccurate Wild-Type Reference.

- Solution: Ensure the wild-type model and its flux distribution (often calculated via FBA) are realistic and validated for your specific growth condition. The solution of

linearMOMAcan be sensitive to the chosen wild-type flux vector [13] [12]. Use theget_minimal_fba_fluxfunction if available to find a non-arbitrary, parsimonious FBA solution as the reference [12].

- Solution: Ensure the wild-type model and its flux distribution (often calculated via FBA) are realistic and validated for your specific growth condition. The solution of

Cause 2: Incorrect Formulation for the Biological Question.

- Solution: Choose the algorithm based on the physiological state you wish to model. Use MOMA for the immediate post-perturbation state before adaptive regulation. Use ROOM or FBA for the fully adapted steady-state [10]. The following table summarizes the core differences:

| Feature | MOMA | ROOM | FBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Minimize Euclidean distance from wild-type flux | Minimize number of significant flux changes | Maximize/Minimize a biological objective (e.g., growth) |

| Typical Use Case | Initial transient state after knockout | Final adapted steady-state | Optimal steady-state behavior |

| Predicted Growth | Lower, non-optimal | Near-optimal | Optimal |

| Flux Linearity | Can be low | Promotes high linearity | Not a direct objective |

- Cause 3: Missing Constraints or Network Gaps.

- Solution: Verify that all relevant transport reactions and pathway alternatives are present in your model. Incorporate additional constraints from kinetic models or regulatory rules (e.g., using tools like k-OptForce) to eliminate physiologically impossible solutions and improve prediction fidelity, especially under non-aerobic conditions [25].

Issue 2: Implementation and Computational Challenges

Problem: Difficulty in setting up or solving the MOMA/ROOM problem using computational tools like the COBRA Toolbox or PSAMM.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Model and Solver Incompatibility.

- Solution: Quadratic MOMA requires a Quadratic Programming (QP) solver, while linear MOMA and ROOM require Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) solvers. Ensure your solver is correctly configured and supports the problem type. For linear MOMA, the problem is formulated as shown in the COBRA Toolbox documentation [13]:

>

min ∑ |v_wt - v_del|subject to: >S_wt * v_wt = 0,lb_wt ≤ v_wt ≤ ub_wt,c_wt^T * v_wt = f_wt>S_del * v_del = 0,lb_del ≤ v_del ≤ ub_del

- Solution: Quadratic MOMA requires a Quadratic Programming (QP) solver, while linear MOMA and ROOM require Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) solvers. Ensure your solver is correctly configured and supports the problem type. For linear MOMA, the problem is formulated as shown in the COBRA Toolbox documentation [13]:

>

Cause 2: Discrepancies Between Model Structures.

- Solution: The

linearMOMAfunction in the COBRA Toolbox is robust to models that do not have identical reaction sets, as long as they share at least one common reaction [13]. Carefully check the reaction identifiers and compartmentalization between your wild-type and mutant models to ensure consistency.

- Solution: The

Experimental Protocol: Integrating Cybernetic Modeling with MOMA Validation

This protocol outlines a methodology for developing a cybernetic model of a metabolic network and using MOMA predictions to validate and refine it, specifically in the context of understanding mutant strain behavior.

1. System Definition and Data Acquisition

- Define the Metabolic Network: Based on databases like KEGG, reconstruct the pathway of interest (e.g., prostaglandin synthesis from arachidonic acid) [24].

- Acquire Time-Course Data: Obtain quantitative data (e.g., transcriptomic, lipidomic) for metabolites and enzymes under the stimuli of interest. Publicly available resources like LIPID MAPS provide such datasets for various cell types and stimulation protocols [24].

2. Kinetic Model Development

- Formulate Rate Equations: For each reaction, establish kinetic rate expressions (

r_kin). These can be linear or non-linear and should include enzyme concentration terms (e_i). For example, a simplified rate for PGH₂ conversion is:r_PGH2→PGi_kin = e_i * k_PGi * [PGH2][24]. - Incorporate Stimulus Effects: Model external stimuli (e.g., ATP, KLA) using piecewise functions that describe their temporal profile, such as a ramp-up followed by exponential decay [24].

3. Cybernetic Control Integration

- Introduce Control Variables: Augment the kinetic model with cybernetic control variables

u_i(for enzyme synthesis induction) andv_i(for enzyme activity modulation) [24]. - Define the Cellular Objective: Hypothesize a measurable cellular goal relevant to your system. In macrophage modeling, this could be the maximization of TNFα production as a proxy for the inflammatory response [24].

- Formulate Regulated Rates: The final flux through a pathway becomes the kinetically determined rate multiplied by the cybernetic control variable:

r_reg = v_i * r_kin[24].

4. Parameter Estimation and Model Validation

- Employ Hybrid Optimization: Use a multi-step optimization to fit model parameters. A common approach is to first use a genetic algorithm to find a population of near-optimal parameters, followed by a gradient-based method to refine them [24].

- Validate with Independent Data: Test the predictive power of the calibrated model against a dataset not used for parameter estimation (e.g., cells primed and stimulated under different conditions) [24].

5. Integration with MOMA for Mutant Analysis

- Generate MOMA Predictions: Create a constraint-based model from your network. For a gene knockout strain, use MOMA to predict the post-perturbation flux distribution.

- Compare and Refine: Compare the MOMA-predicted fluxes with those simulated by your cybernetic model for the same knockout. Discrepancies can highlight areas where the cybernetic model's regulatory assumptions may need refinement, creating a feedback loop for improving model fidelity and biological insight [24] [10].

The workflow for this integrated approach is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Context |

|---|---|

| Constrained Metabolic Model (e.g., iAF1260) | Provides the stoichiometric foundation and flux constraints for performing FBA, MOMA, and ROOM simulations [25]. |

| Computational Toolboxes (COBRA, PSAMM) | Software platforms that implement algorithms like MOMA and ROOM for in silico prediction of mutant strain phenotypes [13] [12]. |

| Kinetic Model Ensemble | A set of parameterized kinetic models, often trained on multi-mutant flux data, used to provide additional thermodynamic and kinetic constraints to stoichiometric models via methods like k-OptForce [25]. |

| Time-Course Metabolomic/Lipidomic Data | Quantitative measurements of metabolite concentrations over time, essential for parameterizing and validating kinetic and cybernetic models [24]. |

| Gene Expression Microarrays/RNA-seq | Used to measure transcriptomic changes in evolved or stressed strains, which can be correlated with cross-resistance/sensitivity phenotypes and used to inform regulatory constraints in models [26]. |

| Genetic Algorithm Optimization Tool | A computational method used for parameter estimation in complex, non-linear models where traditional gradient-based methods may fail to find a global optimum [24]. |

Implementing MOMA: Methodologies, Algorithms, and Practical Applications in Strain Design

What is Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA)? MOMA is a computational methodology used to predict the flux distribution in a genetically perturbed metabolic network, such as a gene knockout mutant. Unlike Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which assumes the mutant organism reaches a new optimal state, MOMA operates on the hypothesis that the metabolic fluxes in the mutant undergo a minimal redistribution from the wild-type flux configuration. This approach is particularly useful for predicting the behavior of knockout strains that have not been under long-term evolutionary pressure to re-optimize their growth [27].

When should I use MOMA over FBA for predicting mutant phenotypes? You should use MOMA when working with single or multiple gene knockout mutants that have not undergone adaptive evolution. FBA often over-predicts the growth rate of such mutants because it assumes optimality, an assumption that is frequently violated in laboratory-engineered strains. MOMA provides more accurate predictions for these sub-optimal, perturbed metabolic states [28] [27].

Mathematical Foundation

What is the core mathematical problem that MOMA solves? MOMA is formulated as a Quadratic Programming (QP) problem. The objective is to minimize the Euclidean distance between the flux vectors of the wild-type and the mutant strain, subject to the constraints of the stoichiometric model. The core formulation is as follows [11]:

[ \min || \mathbf{vw} - \mathbf{vd} ||^2 ] [ \text{subject to } \mathbf{S} \cdot \mathbf{v_d} = 0 ]

Here, ( \mathbf{vw} ) is the flux vector of the wild-type strain, ( \mathbf{vd} ) is the flux vector of the deletion mutant to be solved for, and ( \mathbf{S} ) is the stoichiometric matrix. This simplifies to a standard QP form [11]:

[ \min \frac{1}{2} \, {\mathbf{vd}}^T \, \mathbf{I} \, \mathbf{vd} + (\mathbf{-vw}) \cdot \mathbf{vd} ] [ \text{subject to } \mathbf{S} \cdot \mathbf{v_d} = 0 ]

where ( \mathbf{I} ) is an identity matrix.

How does MOMA's mathematical approach differ from FBA? FBA is a Linear Programming (LP) problem that maximizes a cellular objective, typically biomass growth. In contrast, MOMA is a QP problem that minimizes the change in flux distribution. This key difference allows MOMA to predict sub-optimal states that are more biologically realistic for unevolved mutants, while FBA predicts optimal states [28] [29].

Implementation and Protocols

What are the primary inputs needed to run a MOMA simulation? To implement MOMA, you will need the following core data and reagents:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Inputs

| Item Name | Type/Format | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | Provides a structured representation of all known metabolic reactions in the organism. |

| Wild-Type Flux Vector ((v_w)) | Numerical Vector | Serves as the reference flux distribution from which the mutant's fluxes minimally deviate. |

| Gene/Reaction Deletion List | Text/List | Specifies the genetic perturbations to simulate. |

| Linear Programming (LP) & Quadratic Programming (QP) Solvers | Software (e.g., in Python, MATLAB) | Computes the optimal solution for the MOMA QP problem. |

What is the step-by-step workflow for a basic MOMA simulation?

- Establish a Wild-Type Baseline: First, determine the flux distribution (( \mathbf{v_w} )) for the wild-type strain. This can be done either by performing an FBA simulation to find the theoretical optimum or, preferably, by using an experimentally determined flux distribution [11].

- Define the Perturbation: Specify the gene(s) or reaction(s) to be knocked out. This will define the constraints for the mutant model, typically by setting the flux through the associated reaction(s) to zero.

- Formulate the QP Problem: Set up the MOMA objective function and constraints as shown in the mathematical foundation section.

- Solve the QP: Use a quadratic programming solver to find the flux vector ( \mathbf{vd} ) that minimizes the distance to ( \mathbf{vw} ) while satisfying all constraints.

- Analyze Output: The solution ( \mathbf{v_d} ) provides a prediction of the metabolic flux distribution in the knockout mutant, including the growth rate and production rates of metabolites of interest.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

The MOMA simulation predicts no feasible solution. What could be wrong? This is a common issue, often caused by overly stringent constraints. Follow this diagnostic flowchart to identify and resolve the problem:

- Problem: An essential gene was knocked out. If a reaction essential for growth (e.g., a critical step in biomass synthesis) is removed, no flux distribution can satisfy both the knockout constraint and the requirement to produce biomass.

Solution: Verify the essentiality of your target gene/reaction in your specific model. You may need to choose a different knockout target or simulate supplementation with essential metabolites.

Problem: Infeasible wild-type flux vector. The provided ( \mathbf{vw} ) might not be a steady-state solution for the model ( ( \mathbf{S} \cdot \mathbf{vw} \neq 0 ) ).

- Solution: Always ensure your wild-type flux vector is a valid steady-state solution for the stoichiometric model before applying knockout constraints.

The MOMA-predicted growth rate is zero, but experimental data shows growth. What is the cause? This discrepancy often arises from regulatory or metabolic adaptations not captured by the model.

- Potential Cause 1: The model may lack knowledge of alternative pathways or isoenzymes that can compensate for the lost function in vivo.

- Action: Curate your model to include all known redundant pathways or isozymes for the knocked-out reaction.

- Potential Cause 2: The model's biomass objective function may be too strict or inaccurate for the mutant condition.

- Action: Review and, if necessary, adjust the biomass composition in the model to better reflect the mutant's physiological state.

My MOMA simulation is computationally expensive. How can I improve performance? For large-scale models or when searching for optimal knockout strategies, MOMA can be computationally intensive.

- Strategy 1: Utilize Mixed-Integer Programming (MIP) techniques. Advanced formulations like BiMOMA (Bi-Level MOMA) integrate MOMA with MIP to efficiently search for optimal gene knockout strategies, significantly reducing computation time [29].

- Strategy 2: Employ metaheuristic algorithms. Hybrid methods like PSOMOMA, ABCMOMA, and CSMOMA combine MOMA with swarm intelligence algorithms (Particle Swarm Optimization, Artificial Bee Colony, Cuckoo Search) to identify near-optimal knockout strategies with less computational expense than exhaustive searches [28].

Comparison with Other Methods

How does MOMA compare to other constraint-based methods like ROOM?

Table 2: Comparison of MOMA with FBA and ROOM for Mutant Prediction

| Feature | MOMA | FBA | ROOM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Objective | Minimize Euclidean distance from wild-type flux | Maximize biomass growth | Minimize number of significant flux changes |

| Mathematical Type | Quadratic Programming (QP) | Linear Programming (LP) | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) |

| Prediction Type | Sub-optimal state | Optimal state | Sub-optimal state (parsimonious) |

| Best Use Case | Unevolved knockouts, immediate post-perturbation response | Wild-type or evolved mutants under selection | Mutants where regulatory constraints minimize flux changes |

| Computational Cost | Moderate (QP) | Low (LP) | High (MILP) |

When is MOMA more accurate than FBA? Experimental validations have consistently shown that MOMA outperforms FBA in predicting the phenotypes of single-gene deletion mutants in E. coli. For instance, one study on a pyruvate kinase mutant found that MOMA predictions had a "significantly higher correlation" with experimental flux data than FBA predictions [27]. MOMA is also more accurate at predicting the growth rates of such knockout strains [27].

Advanced Applications & FAQs

Can MOMA be used for multi-objective optimization in strain design? Yes. MOMA can be integrated into multi-objective optimization frameworks that balance competing goals, such as maximizing the production rate of a desired metabolite while maintaining an acceptable growth rate. Methods like GDMO (Genetic Design through Multi-objective Optimisation) use MOMA to evaluate solutions, providing a set of non-dominated strain design strategies for researchers to choose from [28].

What are PSOMOMA, ABCMOMA, and CSMOMA? These are hybrid optimization techniques that combine MOMA with metaheuristic algorithms for more efficient strain design [28]:

- PSOMOMA: Integrates MOMA with Particle Swarm Optimization.

- ABCMOMA: Combines MOMA with the Artificial Bee Colony algorithm.

- CSMOMA: Hybridizes MOMA with Cuckoo Search.

These methods are designed to identify near-optimal sets of gene knockouts to maximize metabolite production (e.g., succinic acid in E. coli) without the prohibitive computational cost of an exhaustive search [28].

We are designing a high-yield strain. Should we use MOMA or OptKnock? The choice depends on your experimental strategy:

- Use MOMA-based approaches (like OptGene or the hybrids above) if you plan to use the engineered strain directly without a long-term adaptive evolution process. MOMA predicts the immediate post-engineering phenotype.

- Use OptKnock if you plan to subject your engineered strain to adaptive evolution to improve growth. OptKnock designs strains where growth is coupled to production, so evolution will naturally drive the strain to higher production, a state predicted by FBA [29].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) for predicting mutant strain behavior? MOMA is a constraint-based algorithm that predicts the metabolic phenotype of a genetically perturbed strain (e.g., a gene knockout) by assuming that the cell's immediate response is to minimize the redistribution of metabolic fluxes relative to the wild-type state. Instead of assuming optimal growth immediately after perturbation, MOMA finds a sub-optimal flux distribution that is closest to the wild-type using a quadratic programming approach [10] [11]. The objective is to minimize the squared Euclidean distance between the wild-type flux vector (vw) and the knockout strain flux vector (vd), subject to stoichiometric constraints [13] [11].

Q2: How does MOMA differ from other prediction algorithms like FBA or ROOM? MOMA, FBA (Flux Balance Analysis), and ROOM (Regulatory ON/OFF Minimization) serve different predictive purposes. The table below compares their core characteristics.

| Algorithm | Primary Objective | Optimization Method | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| FBA | Maximizes biomass growth or another cellular objective [10] | Linear Programming (LP) | Predicts optimal long-term growth of wild-type or evolved strains [10]. |

| MOMA | Minimizes the Euclidean distance of fluxes from the wild-type state [10] [11] | Quadratic Programming (QP) | Predicts immediate metabolic response after gene knockout [10] [30]. |

| ROOM | Minimizes the number of significant flux changes from the wild-type [10] | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | Predicts steady-state flux after regulatory adaptation post-knockout [10]. |

Q3: What are some successful case studies of MOMA in E. coli for biochemical production? MOMA and its hybrid derivatives have successfully identified gene knockout strategies for overproduction in E. coli.

| Target Biochemical | Gene Knockout Strategy | Predicted/Experimental Outcome | Source/Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Succinate | glpC/b2243 knockout |

30% higher succinate flux from glycerol under anaerobic conditions [31]. | Model-driven (OptFlux) [31] |

| Succinate | Multi-gene knockouts identified by a hybrid algorithm | Higher production rate compared to OptKnock and MOMAKnock [32]. | Hybrid (ACO + MOMA) [32] |

| Succinate and Lactate | Multi-gene knockouts identified by Bat Algorithm | Increased production rates of succinate and lactate [30]. | Hybrid (BATMOMA) [30] |

Q4: My model predicts zero growth after a gene knockout. Is the knockout always lethal? Not necessarily. A prediction of zero growth often means the model as constrained cannot produce essential biomass precursors. You should:

- Verify reaction constraints: Check that uptake and excretion rates for key nutrients and metabolites are correctly set.

- Check for alternative pathways: The model might lack annotation for isoenzymes or underground metabolic functions that can compensate for the knockout. ROOM analysis can help identify such short alternative pathways [10].

- Validate experimentally: In silico predictions are a guide. The knockout should be constructed in the lab to confirm phenotypic impact.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Phenotype Predictions with MOMA

Problem: The flux distributions predicted by MOMA do not align with experimental data from your knockout strains.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incorrect Wild-Type Flux.

- Solution: Ensure the wild-type flux distribution (vw) used in the MOMA calculation is physiologically relevant. If available, use an experimentally determined flux distribution instead of one generated by FBA [11].

- Cause: The strain has adapted.

- Solution: MOMA predicts the immediate post-perturbation state. If your experimental data comes from a strain that has undergone adaptive laboratory evolution, the flux distribution may have shifted toward a more optimal state. In this case, FBA or ROOM might be more appropriate for comparison [10].

- Cause: Overly restrictive constraints.

- Solution: Re-examine the flux bounds (lower and upper limits) applied to the model. Incorrect constraints can make the solution space too small or unrealistic.

Issue 2: Implementing MOMA Calculations

Problem: Difficulty in setting up and running a MOMA simulation.

Solution: Follow this standard protocol for a gene knockout simulation:

- Define the Wild-Type Model: Load your genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., E. coli iJO1366).

- Obtain Wild-Type Flux: Calculate the wild-type flux distribution (v_w). This is typically done by performing an FBA simulation to maximize growth.

- Create the Knockout Model: Modify the model to remove the reaction(s) associated with the target gene(s). This is often done by setting the upper and lower flux bounds of the reaction to zero.

- Run MOMA: Solve the MOMA optimization problem using the wild-type flux (vw) and the knockout model. The objective is to find the flux distribution in the knockout model (vd) that minimizes ||vw - vd||² [13] [11].

- Analyze Results: The output is the predicted flux distribution for the knockout strain. Analyze key production and growth rates.

Code Implementation: The COBRA Toolbox provides functions for both quadratic and linear MOMA [13].

Issue 3: Choosing the Right Algorithm for Your Goal

Problem: Uncertainty about whether to use MOMA, ROOM, or FBA.

Solution: Use the decision workflow below to select the appropriate algorithm.

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Hybrid (BATMOMA) for Succinate Production in E. coli

This protocol outlines the steps for the hybrid Bat Algorithm and MOMA (BATMOMA) used to predict gene knockouts for succinate overproduction [30].

1. Algorithm Initialization:

- Representation: Each "bat" in the population represents a potential knockout strategy. It is a binary vector where each bit corresponds to a gene in the metabolic model (1 = present, 0 = knocked out) [30].

- Parameters: Initialize the bat population (e.g., population size n=20). Set parameters for frequency (f), pulse rate (r), and loudness (A) [30].

2. Fitness Evaluation using MOMA:

- For each bat (knockout strategy), create a corresponding metabolic model by constraining reactions of "knocked out" genes to zero.

- Perform a MOMA simulation to predict the metabolic phenotype of this knockout model.

- The fitness function is designed to maximize the succinate production rate. A constraint is applied to ensure the growth rate is above a threshold (e.g., > 0.1 h⁻¹) to guarantee cell viability [30].

3. Bat Algorithm Movement:

- Global Search (Guided Flight): Bats update their velocities and positions based on the current best solution (x).

- Frequency: ( fi = f{min} + \beta (f{max} - f{min}) ) where β ∈ [0,1]

- Velocity: ( vi^{t+1} = vi^t + (xi^t - x^) fi )

- Position: ( xi^{t+1} = xi^t + v_i^{t+1} ) [30]

- Local Search (Random Walk): If a random number is greater than the pulse rate (r_i), a new solution is generated locally around the current best solution.

4. Termination and Output:

- Steps 2 and 3 repeat for a set number of generations (e.g., 50).

- The algorithm outputs a list of optimal gene knockout strategies, along with their predicted growth and succinate production rates [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model | Provides a computational representation of an organism's metabolism for in silico simulations. | E. coli iJO1366 model used for predicting succinate production after glpC knockout [31]. |

| Software Platform | Provides the computational environment to run constraint-based analyses like FBA and MOMA. | OptFlux software platform [31]; COBRA Toolbox in MATLAB [13]. |

| Expression Vector with Intein System | Enables the production of recombinant native proteins without N-terminal affinity tags. | pSB vector with Ssp DnaB mini-intein used for direct expression of native hIFNalpha-4 in E. coli [33]. |

| Specialized E. coli Strain | Serves as a host for protein expression, often engineered to improve disulfide bond formation and protein folding. | E. coli strain Origami B (DE3) used for soluble expression of hIFNalpha-4 [33]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind the BATMOMA hybrid algorithm? BATMOMA combines a nature-inspired optimization algorithm (Bat Algorithm, BA) with a constraint-based metabolic modeling approach (Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment, MOMA) [34]. The BA performs a global search for potential gene knockout strategies, while MOMA predicts the resulting metabolic flux distribution in the engineered mutant, ensuring minimal deviation from the wild-type flux profile and a physiologically viable state [34] [11].

Q2: Which specific microbial host and products was BATMOMA applied to? The BATMOMA algorithm was developed to predict gene knockouts in Escherichia coli (E. coli) to maximize the production rates of two industrially important chemicals: succinate and lactate [34].

Q3: What are the advantages of using BATMOMA over a single optimization method? This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both components. The Bat Algorithm efficiently explores the vast combinatorial space of possible gene knockouts. MOMA then provides a more realistic prediction of the metabolic phenotype after a gene knockout by assuming the cell adjusts its fluxes with minimal change from the wild-type state, rather than immediately achieving optimal growth [34] [10].

Q4: What are common issues if my BATMOMA simulation fails to converge or produces unrealistic fluxes? This is often related to model constraints. Verify that the metabolic network model accurately reflects the microbial host and that the flux bounds (upper and lower limits for reactions) are set correctly. Ensuring that the Bat Algorithm parameters (e.g., population size, frequency) are properly tuned for your specific problem scale can also improve convergence [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Predicted Production Yield in BATMOMA Simulation

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate exploration of the solution space by the Bat Algorithm.

- Solution: Increase the population size or the number of iterations in the BA component. You may also need to fine-tune the algorithm's parameters, such as loudness and pulse rate [34].

- Potential Cause 2: The MOMA prediction may be constrained by unrealistic flux boundaries.

- Solution: Review and adjust the flux capacity constraints (e.g.,

v_max)

- Solution: Review and adjust the flux capacity constraints (e.g.,

in your metabolic model based on recent experimental data, if available [10].

Problem: Simulation Predicts Non-Viable (Lethal) Gene Knockouts

- Potential Cause: The proposed gene knockout disrupts an essential metabolic reaction, leading to no feasible flux distribution that can sustain basic cell functions.

- Solution: Implement a penalty in the BA fitness function for lethal knockouts. Incorporate prior knowledge (e.g., lists of essential genes) to filter out non-viable candidates before the MOMA simulation [34].

Problem: Discrepancy Between Predicted and Experimental Production Yields

- Potential Cause 1: The metabolic model may be missing key reactions or regulatory constraints.

- Solution: Curate and update the genome-scale metabolic model to include the latest annotations and, if possible, incorporate regulatory information [10].

- Potential Cause 2: MOMA predicts sub-optimal states, but during fermentation, strains may adapt and evolve toward higher growth rates.

- Solution: Consider using an alternative algorithm like Regulatory On/Off Minimization (ROOM) or comparing results with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to predict potential evolutionary endpoints [10].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Succinate Production in E. coli The following table summarizes specific genetic modifications, informed by metabolic engineering, that can be used to validate or inform BATMOMA predictions for succinate production [35] [36].

Table 1: Gene Modification Strategies for Optimizing Succinate Production

| Gene | Encoded Enzyme | Modification Type | Physiological Rationale and Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| ptsG | Glucose phosphotransferase | Deletion | Saves phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) consumed in sugar uptake, making more precursor available for succinate synthesis [36]. |

| pykF, pykA | Pyruvate kinase I & II | Deletion / Attenuation | Prevents conversion of PEP to pyruvate, minimizing flux to byproducts like lactate and acetate. Fine-tuning via sRNA is effective [35] [36]. |

| maeA, maeB | Malic enzyme | Deletion | Inhibits decarboxylation of malate to pyruvate, redirecting carbon toward succinate [36]. |

| pck | PEP carboxykinase | Overexpression | Drives carboxylation of PEP to oxaloacetate (a succinate precursor) and generates ATP [35] [36]. |

| sdh | Succinate dehydrogenase | Deletion | Blocks the succinate consumption pathway within the TCA cycle, leading to its accumulation [35] [36]. |

| ppc | PEP carboxylase | Deletion | In a pck-overexpressing strain, this deletion enhances energy status and activates PCK-driven carboxylation [36]. |

Quantitative Impact of Metabolic Engineering on Succinate Yield The effectiveness of sequential genetic modifications can be seen in the increasing yield of succinate from glucose.

Table 2: Progression of Succinate Yield in Engineered E. coli Strains

| Strain Description | Key Genetic Modifications | Succinate Yield (mol/mol glucose) |

|---|---|---|

| Parent Strain | Wildtype E. coli BW25113 | ~0.10 [36] |

| Initial Mutant | ΔptsG | 0.22 [36] |

| Optimized Mutant | ΔptsG, Δppc, ΔpykA, ΔmaeA, ΔmaeB, Δsdh, ΔiclR, overexpressing pck-ecaA | 1.13 [35] [36] |

BATMOMA Workflow and Central Carbon Metabolism

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the BATMOMA algorithm for predicting gene knockouts.

BATMOMA Algorithm Flow

This diagram summarizes key modifications in the central carbon metabolism of E. coli for enhancing succinate production, which serves as a biological context for BATMOMA predictions.

Central Carbon Metabolism Modifications

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for BATMOMA-Guided Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model | A stoichiometric model (e.g., of E. coli) used for in silico flux simulations with MOMA [34]. |

| Bat Algorithm (BA) Code | The metaheuristic component for global optimization of gene knockout combinations; often implemented in MATLAB or Python [34]. |

| MOMA Solver | A quadratic programming solver used to compute flux distributions that minimize metabolic adjustment in mutant strains [12] [11]. |

| Knockout Strain Construction Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems or λ-Red recombinering kits for precise gene deletions in the microbial host [35] [36]. |

| Anaerobic Fermentation Setup | Bioreactors or sealed tubes for cultivating engineered strains under oxygen-free conditions to simulate industrial production [36]. |

| Analytical HPLC/GC-MS | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography or Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry for quantifying metabolite concentrations (succinate, lactate, acetate, glucose) in culture broth [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is BiMOMA and how does it differ from traditional MOMA? BiMOMA is a bi-level optimization approach that integrates the Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) principle into a Mixed-Integer Quadratically Constrained Programming (MIQCP) framework to identify optimal gene knockout strategies for metabolic engineering [29]. While traditional MOMA is a quadratic programming (QP) problem that finds a sub-optimal flux distribution in a mutant by minimizing the Euclidean distance from the wild-type flux distribution [11], BiMOMA formulates this as a bi-level problem where the inner problem is MOMA itself [29]. This bi-level structure is then converted into a single-level MIQCP problem using its optimality conditions, enabling efficient identification of gene deletion strategies without relying on sequential search or heuristic algorithms [29].

Q2: When should I use BiMOMA instead of FBA or OptKnock for strain design? BiMOMA is particularly suitable when designing unevolved mutant strains where you want to predict metabolic states immediately after genetic perturbation without assuming optimal growth recovery [29] [10]. Unlike FBA-based methods like OptKnock that predict evolved mutants with coupled growth and product formation, BiMOMA predicts transient metabolic states that don't require adaptive evolution [29]. Use BiMOMA when your experimental strategy involves characterizing immediate knockout effects rather than evolved strains, or when working with systems where growth and product formation cannot be effectively coupled [29].