Model Validation and Selection in Metabolic Flux Analysis: A Guide for Reliable Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to model validation and selection for metabolic flux analysis (MFA) and flux balance analysis (FBA), critical methodologies in systems biology and metabolic engineering.

Model Validation and Selection in Metabolic Flux Analysis: A Guide for Reliable Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to model validation and selection for metabolic flux analysis (MFA) and flux balance analysis (FBA), critical methodologies in systems biology and metabolic engineering. We explore the foundational principles of constraint-based modeling, including 13C-MFA and FBA, which estimate in vivo metabolic fluxes that cannot be directly measured. The content details established and emerging methodological approaches for testing model reliability, from traditional χ2-tests to advanced validation-based selection frameworks. We address common troubleshooting challenges such as overfitting, underfitting, and measurement uncertainty, while presenting optimization strategies that integrate multi-omics data. Finally, we examine comparative validation techniques and their application in biomedical research, offering scientists and drug development professionals a robust framework for enhancing confidence in metabolic models and their applications in biotechnology and therapeutic development.

Understanding the Core Principles of Metabolic Flux Analysis and Why Validation Matters

A Comparative Guide to Metabolic Flux Analysis Methods

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) are cornerstone computational techniques in constraint-based modeling, enabling researchers to predict intracellular metabolic reaction rates (fluxes) that are impossible to measure directly [1]. While both methods use metabolic network models operating at steady state, their underlying principles, data requirements, and applications differ significantly. This guide provides an objective comparison of their fundamentals, performance, and validation within the critical context of model selection for robust flux analysis [1] [2].

│ Core Principles and Methodologies

13C-MFA and FBA are built on different philosophical approaches to determining metabolic fluxes.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): A Predictive Approach

FBA is a constraint-based approach that predicts flux distributions using linear optimization [1]. It operates on genome-scale stoichiometric models (GSSMs) that incorporate all known metabolic reactions for an organism [3].

- Objective Function: FBA requires the assumption that cellular metabolism is optimized for a biological objective, most commonly maximization of biomass production or growth rate [3] [4]. Alternative objectives include minimization of total flux or ATP production.

- Constraints: The solution is constrained by the stoichiometry of the metabolic network and, optionally, measurements of external fluxes (e.g., substrate uptake rates) [1] [3].

- Output: FBA provides a single flux map or a set of flux maps that optimize the stated objective within the feasible solution space [1].

The following diagram illustrates the linear optimization logic at the core of FBA:

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA): An Estimative Approach

13C-MFA is a data-driven approach that estimates fluxes by fitting a model to experimental data from isotope labeling experiments (ILEs) [1] [5]. It typically uses smaller, core models of central carbon metabolism.

- Experimental Data: Cells are fed with ¹³C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose or glutamine). After isotopic steady state is reached, the labeling patterns (mass isotopomer distributions, MIDs) of intracellular metabolites or proteinogenic amino acids are measured via mass spectrometry (GC-MS or LC-MS) [6] [5].

- Model Fitting: Fluxes are estimated by solving a nonlinear optimization problem that minimizes the difference between the experimentally measured MIDs and those simulated by the model [1] [7].

- Validation: A χ²-test of goodness-of-fit is commonly used for model validation, and confidence intervals for fluxes are determined via statistical methods like Monte Carlo simulation [6] [8].

The workflow for 13C-MFA is more complex and involves both wet-lab and computational steps, as shown below:

│ Direct Comparison: 13C-MFA vs. FBA

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between the two methods.

| Feature | 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Approach | Data-driven estimation [1] [7] | Hypothesis-driven prediction [1] [3] |

| Core Data | ¹³C Isotopic labeling data (MIDs) [1] [5] | Stoichiometric model; optional external fluxes [1] |

| Typical Model Scope | Core metabolic networks (e.g., central carbon) [3] | Genome-scale models (GSSMs) [3] |

| Mathematical Foundation | Nonlinear regression [7] | Linear programming [3] |

| Key Assumption | Metabolic and isotopic steady state [1] | Evolutionarily optimized objective function [3] [4] |

| Flux Validation | Direct via fit to experimental MID data (χ²-test) [1] [8] | Indirect, often by comparison to 13C-MFA data [1] [3] |

| Key Strength | High precision and accuracy for core metabolism [3] | System-wide perspective; predicts all metabolic fluxes [3] |

│ Model Validation and Selection Frameworks

Model validation and selection are critical for ensuring the reliability of flux maps [1].

Validation in 13C-MFA

- The χ²-test: This is the most widely used quantitative validation method. It evaluates whether the difference between measured and simulated data is statistically acceptable given the measurement errors [1] [8].

- Limitations of the χ²-test: This test can be unreliable if measurement errors are inaccurately estimated, which is common when error magnitudes are very low or when biases exist [8]. This may force researchers to either artificially inflate error estimates or over-complicate the model to force a good fit [8].

- Validation-Based Model Selection: A more robust approach uses independent validation data (e.g., from a different tracer experiment) not used for model fitting. The model that best predicts this new data is selected, which is more robust to uncertainties in measurement error estimates [8].

- Parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA): For underdetermined systems, a second optimization can be applied to find the flux map that fits the data with the minimum total flux. This principle can be weighted by gene expression data to ensure biological relevance [7].

Validation in FBA

- Lack of Direct Validation: Unlike 13C-MFA, FBA lacks a built-in mechanism to falsify model predictions against a self-contained dataset [3]. An FBA solution will be produced for almost any input.

- Comparison to 13C-MFA: The most robust validation for FBA predictions is to compare them against fluxes estimated by 13C-MFA, which is considered the gold standard [1] [3]. Discrepancies can reveal flaws in the model's network structure or the chosen objective function [3].

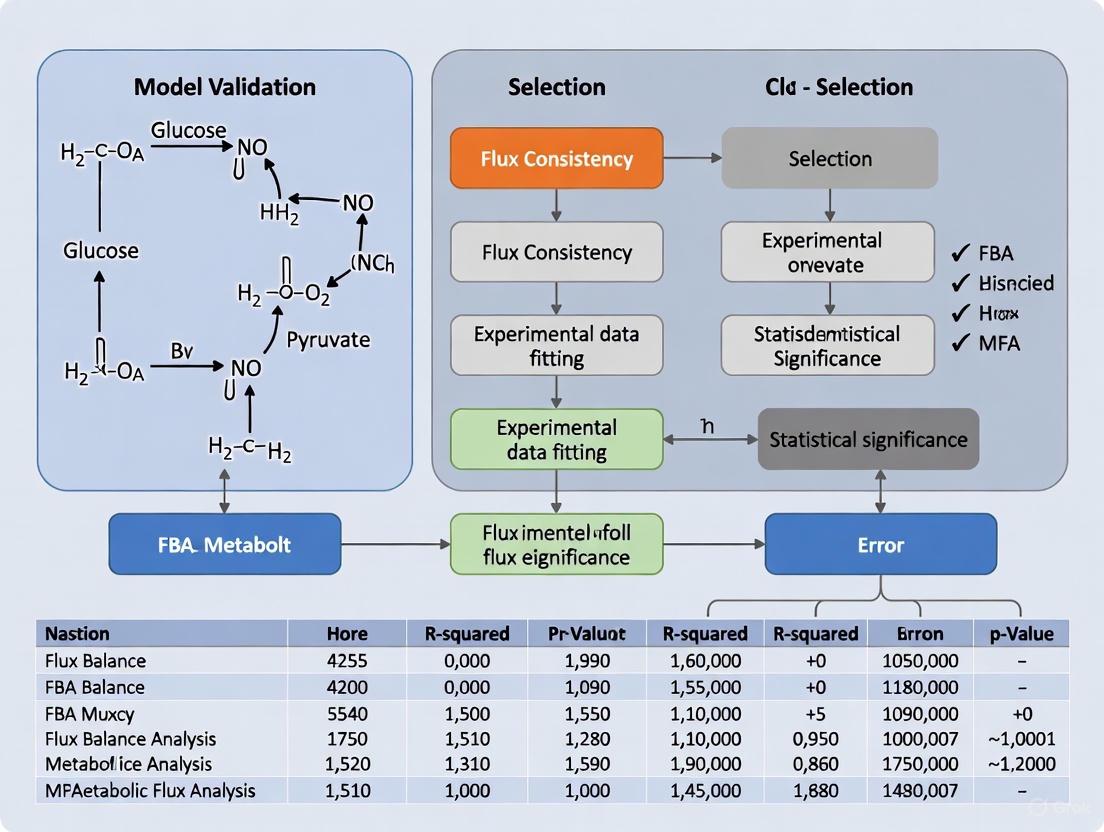

The logical process for model selection, highlighting the modern validation-based approach, is shown below:

│ The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of 13C-MFA and FBA relies on specialized software and reagents.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| ¹³C-Labeled Tracers (e.g., [1-¹³C] glucose, [U-¹³C] glutamine) | Fingerprint downstream metabolites to infer flux through different pathways [5]. |

| Defined Culture Medium | Essential for 13C-MFA to maintain a known and controlled labeling input [6]. |

| Proteinogenic Amino Acids | Proxy metabolites for GC-MS measurement; their labeling patterns reflect central metabolic fluxes [6] [5]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | The workhorse analytical platform for measuring mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) in 13C-MFA [5]. |

Computational Software Platforms

| Software | Primary Function | Key Features & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| WUFlux [6] | 13C-MFA | Open-source MATLAB platform with user-friendly GUI; provides model templates for various microbes. |

| 13CFLUX(v3) [9] | 13C-MFA | High-performance C++ engine with Python interface; supports stationary and non-stationary MFA. |

| Iso2Flux / p13CMFA [7] | 13C-MFA | Implements parsimonious flux minimization and can integrate transcriptomics data. |

| COBRA Toolbox | FBA | A standard suite of MATLAB tools for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) [3]. |

│ Integrated and Advanced Approaches

The distinction between 13C-MFA and FBA is blurring with the development of hybrid methods that leverage the strengths of both.

- Constraining Genome-Scale Models with ¹³C Data: New methods integrate ¹³C labeling data directly into genome-scale models without relying on an assumed evolutionary objective. One approach uses the simple biological assumption that flux flows from core to peripheral metabolism and does not flow back, effectively constraining the solution space with the labeling data [3] [4]. This provides flux estimates for peripheral metabolism with the validation benefit of matching experimental labeling measurements [3].

- Parallel Labeling Experiments (PLEs): Performing multiple tracer experiments in parallel and integrating the data into a single 13C-MFA model significantly improves flux resolution and precision [1] [5].

The Critical Role of Metabolic Fluxes in Systems Biology and Phenotypic Expression

Metabolic fluxes represent the functional phenotype of a biological system, integrating information from the genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome. This review comprehensively compares two primary methodologies for flux analysis—Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)—within the critical context of model validation and selection. We present structured comparisons of their technical capabilities, data requirements, and validation approaches, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols. By framing this analysis around statistical validation frameworks and selection criteria, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with objective guidance for implementing robust flux analysis in metabolic engineering and biomedical research.

Metabolic fluxes, defined as the rates of metabolite conversion through biochemical pathways, constitute an integrated functional phenotype that emerges from multiple layers of biological organization and regulation [10] [11] [12]. The fluxome represents the complete set of metabolic fluxes in a cell and provides a dynamic representation of cellular phenotype that results from interactions between the genome, transcriptome, proteome, post-translational modifications, and environmental factors [12]. Unlike static molecular inventories, fluxes capture the functional outcome of these complex interactions, making them crucial for understanding cellular behavior in both health and disease [10] [13].

The significance of flux analysis extends across multiple domains of biological research. In metabolic engineering, flux measurements have guided the development of high-producing microbial strains, such as lysine hyper-producing Corynebacterium glutamicum [10]. In biomedical research, flux analysis has revealed metabolic rewiring in cancer cells, including the Warburg effect, reductive glutamine metabolism, and altered serine/glycine metabolism [13]. The critical challenge, however, lies in accurately measuring these fluxes, as they cannot be directly observed but must be inferred through mathematical modeling of experimental data [10] [14].

Comparative Analysis of Flux Analysis Methods

Multiple computational approaches have been developed to determine metabolic fluxes, each with distinct theoretical foundations and application domains. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constraint-based approach that uses linear optimization to predict flux distributions that maximize or minimize a specified cellular objective, such as growth rate or ATP production [10] [15]. FBA operates at steady state and can analyze genome-scale metabolic networks incorporating thousands of reactions [10] [12]. In contrast, 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) employs isotopic tracers to experimentally determine fluxes in central carbon metabolism, including glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and TCA cycle [15] [13]. 13C-MFA combines mass balancing with isotope labeling patterns to estimate intracellular fluxes with high precision [10] [13].

Additional specialized methods have evolved to address specific research needs. Isotopically Nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA) extends 13C-MFA by analyzing transient labeling patterns before the system reaches isotopic steady state, significantly reducing experiment time, particularly for slow-labeling systems like mammalian cells [15]. Dynamic MFA (DMFA) determines flux changes in cultures not at metabolic steady state by dividing experiments into time intervals and assuming relatively slow flux transients [15]. COMPLETE-MFA utilizes multiple singly labeled substrates simultaneously to enhance flux resolution [15].

Technical Comparison of FBA and 13C-MFA

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of FBA and 13C-MFA Methodologies

| Characteristic | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Constraint-based optimization using stoichiometric matrix [12] | Mass balance combined with isotopic labeling distribution [13] |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale (1000+ reactions) [15] | Central metabolism (50-100 reactions) [15] |

| Steady-State Requirement | Metabolic steady state only [15] | Metabolic and isotopic steady state [15] |

| Primary Data Input | Stoichiometry, constraints, objective function [10] | Isotopic labeling patterns, extracellular fluxes [13] |

| Measurement Type | Predictive [10] | Estimative [10] |

| Key Software Tools | COBRA Toolbox, cobrapy, FASIMU [10] [12] | INCA, Metran, OpenFLUX [15] [13] |

| Typical Applications | Genome-scale prediction, network discovery, gap filling [10] | Quantitative flux quantification in core metabolism [13] |

| Validation Approaches | Growth/no-growth prediction, growth rate comparison [10] | χ2-test of goodness-of-fit, validation-based selection [10] [14] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Flux Analysis Methods

| Performance Metric | FBA | 13C-MFA | INST-MFA | DMFA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Resolution | Single steady state | Single steady state | Minutes to hours | Multiple time intervals |

| Isotope Experiment Duration | Not applicable | Hours to days (to isotopic steady state) | Minutes to hours | Hours to days |

| Typical Flux Precision | Low to medium | High | Medium to high | Medium |

| Network Coverage | High (genome-scale) | Medium (central metabolism) | Medium (central metabolism) | Medium (central metabolism) |

| Computational Demand | Low to medium | High | Very high | Extremely high |

| Measurement Uncertainty Quantification | Flux variability analysis [10] | Confidence intervals, statistical tests [10] [14] | Confidence intervals | Not standardized |

Experimental Design and Workflow

The experimental workflow for 13C-MFA involves several critical stages, each requiring careful execution to ensure reliable flux estimation [13]. The process begins with cell cultivation under controlled conditions to achieve metabolic steady state, where metabolic fluxes and intermediate concentrations remain constant over time [15]. Next, labeling experiments are performed by introducing 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose) to the system [15] [13]. After sufficient time for isotope incorporation (reaching isotopic steady state for 13C-MFA, or during transient labeling for INST-MFA), samples are quenched and metabolites extracted [15]. Analytical measurement of isotopic labeling patterns is typically performed using mass spectrometry (62.6% of studies) or NMR spectroscopy (35.6% of studies) [15]. Finally, computational modeling integrates the labeling data with network stoichiometry to estimate flux values that best explain the experimental measurements [13].

Diagram 1: 13C-MFA Experimental Workflow. The process begins with cell cultivation at metabolic steady state, proceeds through isotope labeling and analytical measurement, and culminates in computational modeling with validation.

Model Validation and Selection Frameworks

The Critical Importance of Model Selection

Model selection represents a fundamental challenge in metabolic flux analysis, as the choice of model structure directly impacts flux estimates and subsequent biological interpretations [14]. The model selection problem arises because multiple network architectures may potentially explain experimental data, yet selecting an incorrect model can lead to either overfitting (including unnecessary reactions that fit noise rather than signal) or underfitting (excluding essential reactions) [14]. Both scenarios result in inaccurate flux estimates and potentially erroneous biological conclusions.

Traditional approaches to model selection often rely on informal trial-and-error procedures during model development, where models are successively modified until they pass statistical tests based on the same data used for fitting [14]. This practice can introduce bias and overconfidence in selected models. As noted by Sundqvist et al., "Model selection is often done informally during the modelling process, based on the same data that is used for model fitting (estimation data). This can lead to either overly complex models (overfitting) or too simple ones (underfitting), in both cases resulting in poor flux estimates" [14].

Validation Methodologies

The χ2-Test of Goodness-of-Fit

The χ2-test of goodness-of-fit represents the most widely used quantitative validation approach in 13C-MFA [10] [14]. This statistical test evaluates whether the differences between measured and simulated mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) are likely due to random measurement error alone [10]. A model passes the χ2-test when the sum of weighted squared residuals falls below a critical threshold determined by the desired confidence level and degrees of freedom in the data [14].

Despite its widespread use, the χ2-test has significant limitations when used for model selection. Its correctness depends on accurately knowing the number of identifiable parameters, which can be difficult to determine for nonlinear models [14]. More importantly, the test relies on accurate estimates of measurement errors, which are often underestimated in practice due to unaccounted experimental biases and instrumental limitations [14]. When errors are underestimated, even correct models may fail the χ2-test, potentially leading researchers to incorporate unnecessary complexity to improve fit.

Validation-Based Model Selection

Validation-based model selection has emerged as a robust alternative to address limitations of goodness-of-fit tests [14]. This approach utilizes independent validation data—distinct from the data used for model fitting—to evaluate model performance and select the most predictive model structure [14]. The fundamental principle is that a model with appropriate complexity should generalize well to new data not used during parameter estimation.

The implementation of validation-based selection involves dividing experimental data into training and validation sets [14]. Candidate model structures are fitted to the training data, and their predictive performance is evaluated on the validation data. The model with the best predictive performance for the validation set is selected. This approach offers particular advantages when measurement uncertainties are poorly estimated, as it remains robust even when error magnitudes are substantially miscalculated [14].

Diagram 2: Validation-Based Model Selection Workflow. Experimental data is partitioned into estimation and validation sets. Models are fitted to estimation data and evaluated on validation data based on predictive performance before final selection.

Validation in Flux Balance Analysis

Validation approaches for FBA differ significantly from those used in 13C-MFA due to FBA's predictive rather than estimative nature [10]. Quality control checks ensure basic model functionality, such as verifying the inability to generate ATP without an external energy source or synthesize biomass without required substrates [10]. The MEMOTE (MEtabolic MOdel TEsts) pipeline provides standardized tests to ensure stoichiometric consistency and metabolic functionality across different growth conditions [10].

Common FBA validation strategies include comparing predicted versus experimental growth capabilities on different substrates and comparing predicted versus measured growth rates [10]. While growth/no-growth validation provides qualitative assessment of network completeness, growth rate comparison offers quantitative assessment of model accuracy regarding metabolic efficiency [10]. However, these approaches primarily validate overall network function rather than internal flux predictions.

Experimental Protocols for Flux Analysis

Protocol for 13C-MFA in Cancer Cell Lines

Cell Culture and Labeling

- Cell Cultivation: Maintain cancer cells in appropriate medium (e.g., DMEM or RPMI-1640) with 10% fetal bovine serum under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). Passage cells regularly to maintain exponential growth [13].

- Experimental Setup: Seed cells at appropriate density (typically 0.5-1.0 × 10^6 cells per well in 6-well plates) in unlabeled medium and allow to attach for 24 hours [13].

- Tracer Introduction: Replace medium with fresh medium containing 13C-labeled substrates. Common tracers for cancer studies include [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, or [U-13C]glutamine at physiological concentrations (e.g., 5-10 mM glucose, 2-4 mM glutamine) [13].

- Harvesting: Incubate cells until isotopic steady state is reached (typically 24-48 hours for mammalian cells). Harvest cells and medium at multiple time points for extracellular flux analysis and labeling measurements [13].

Metabolic Quenching and Extraction

- Quenching: Rapidly remove medium and quench cellular metabolism by adding cold methanol (-40°C) [15] [13].

- Metabolite Extraction: Extract intracellular metabolites using 80% methanol/water solution at -20°C. Add internal standards for quantification [15].

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge extracts, collect supernatants, and dry under nitrogen gas. Derivatize metabolites for GC-MS analysis using appropriate derivatization agents (e.g., methoxyamine hydrochloride and MTBSTFA for polar metabolites) [15].

Analytical Measurement and Data Processing

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze derivatized samples using GC-MS with electron impact ionization. Monitor appropriate mass fragments for key metabolites from central carbon metabolism [15] [13].

- Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) Calculation: Correct raw mass spectrometry data for natural isotope abundances and calculate mass isotopomer distributions for each metabolite [13].

- External Flux Determination: Measure nutrient consumption (glucose, glutamine) and product secretion (lactate, ammonium) rates using enzyme assays or HPLC. Calculate specific uptake/secretion rates using cell growth data [13].

Protocol for INST-MFA

Isotopically Nonstationary MFA follows a similar experimental approach but with critical modifications for time-course labeling measurements [15]:

- Rapid Sampling: After introducing 13C-labeled substrate, collect samples at multiple early time points (seconds to minutes) before isotopic steady state is reached [15].

- Rapid Quenching: Use specialized quenching techniques to accurately capture transient labeling states [15].

- Computational Modeling: Employ INST-MFA algorithms that solve differential equations for isotopomer dynamics rather than algebraic balance equations used in stationary MFA [15].

The elementary metabolite unit (EMU) modeling framework dramatically reduces computational difficulty in INST-MFA by decomposing the network into smaller fragments [15].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Flux Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine, 13C-NaHCO3 | Serve as metabolic tracers; carbon backbone enables tracking of metabolic pathways through labeling patterns [15] [13] |

| Cell Culture Media | Glucose-free DMEM, glutamine-free RPMI-1640 | Enable precise control of labeled nutrient concentrations; absence of unlabeled components prevents isotopic dilution [13] |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | 13C-labeled internal standards (e.g., U-13C-amino acids) | Enable quantification and correction for instrument variation; ensure accurate mass isotopomer distribution measurements [15] |

| Derivatization Reagents | Methoxyamine hydrochloride, MTBSTFA, N-methyl-N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide | Enhance volatility and detectability of polar metabolites for GC-MS analysis; improve separation and sensitivity [15] |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | Glucose assay kit, lactate assay kit, glutamine/glutamate assay kit | Quantify extracellular metabolite concentrations for determination of uptake/secretion rates [13] |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Rotenone (complex I inhibitor), UK5099 (mitochondrial pyruvate carrier inhibitor) | Perturb specific pathways to test model predictions; provide additional validation of flux estimates [13] |

Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Flux analysis has enabled significant advances in understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets. In cancer biology, 13C-MFA has revealed the critical role of pyruvate carboxylase in supporting anaplerosis and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle function in various cancer types [14] [13]. Flux measurements have demonstrated that many cancer cells rely on both glucose and glutamine metabolism to maintain TCA cycle activity, providing insights into metabolic vulnerabilities that could be therapeutically exploited [13].

In infectious disease research, FBA has identified essential metabolic functions in pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [12]. For example, Rama et al. used FBA to analyze the mycolic acid pathway in M. tuberculosis, identifying multiple potential drug targets through in silico gene deletion studies [12]. Similarly, FBA of S. aureus metabolic networks identified enzymes essential for growth that represent promising antibacterial targets [12].

The integration of flux analysis with other omics technologies represents a powerful approach for identifying metabolic dependencies in disease states. By combining flux measurements with transcriptomic and proteomic data, researchers can distinguish between metabolic regulation at the enzyme abundance level (captured by transcriptomics/proteomics) and enzyme activity level (revealed by fluxomics) [11] [12]. This multi-layered understanding is particularly valuable for identifying nodes where metabolic control is exerted, which often represent the most promising targets for therapeutic intervention.

Metabolic flux analysis provides an unparalleled window into the functional state of cellular metabolism, serving as a crucial integrator of multi-omics data. As we have demonstrated through comparative analysis, both FBA and 13C-MFA offer distinct strengths and limitations, with appropriate application dependent on research goals, network scale, and data availability. The critical advancement in recent years has been the recognition that model validation and selection are not merely technical considerations but fundamental determinants of flux estimation accuracy.

The move toward validation-based model selection frameworks represents significant progress in addressing the limitations of traditional goodness-of-fit tests [14]. By prioritizing predictive performance over descriptive fit, these approaches enhance the reliability of flux estimates and biological conclusions derived from them. Furthermore, the integration of flux data with other omics layers through constraint-based modeling creates opportunities for more comprehensive understanding of metabolic regulation in health and disease.

For researchers implementing flux analysis in drug development and biomedical research, we recommend: (1) adopting validation-based model selection approaches, particularly when measurement uncertainties are poorly characterized; (2) applying multiple complementary flux analysis methods where feasible to leverage their respective strengths; and (3) transparently reporting model selection procedures and validation results to enable critical evaluation of flux estimates. As flux analysis methodologies continue to evolve, robust validation and model selection practices will be essential for maximizing their impact in understanding and manipulating metabolic systems.

Metabolic fluxes represent the dynamic flow of biochemical reactions within living organisms, defining an integrated functional phenotype that emerges from multiple layers of biological organization and regulation [10]. Unlike static molecular entities such as transcripts, proteins, or metabolites, fluxes are rates of conversion that cannot be isolated, amplified, or directly quantified using conventional analytical techniques [10] [16]. This fundamental limitation represents a core challenge in metabolism research, particularly for studies conducted in live organisms (in vivo) where physiological context is preserved. The inability to directly measure metabolic fluxes has necessitated the development of sophisticated indirect methods that combine isotope tracing with mathematical modeling, creating the specialized field of metabolic flux analysis (MFA) [10] [16].

The importance of understanding metabolic flux extends beyond basic scientific curiosity to practical applications in drug development and metabolic engineering. For metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and cancer, alterations in pathway fluxes often precede pathological changes in metabolite concentrations or enzyme expression [17] [16]. Consequently, pharmaceutical researchers increasingly recognize that static "snapshot" measurements of metabolic intermediates (so-called "statomics") frequently fail to reveal actual metabolic status or identify viable drug targets [18]. This article examines the fundamental barriers to direct flux measurement, outlines the established methodological workarounds, and explores how robust model validation practices are essential for generating reliable flux estimates in complex in vivo systems.

The Nature of Metabolic Fluxes

Defining Metabolic Flux in Living Systems

Metabolic flux refers to the in vivo rate of substrate conversion to products through a defined biochemical pathway or network [10]. In a living organism, these fluxes are not isolated to individual cells or tissues but are distributed across organ systems connected by circulating nutrients and hormones [16]. For example, hepatic gluconeogenesis and the mitochondrial citric acid cycle work in concert during fasting to supply glucose to the body, with fluxes through these pathways being tightly regulated by allosteric control, substrate availability, and hormonal signaling [17]. This inter-organ coordination means that fluxes measured in isolated cell systems may not accurately reflect their values in intact organisms, highlighting the necessity of in vivo flux analysis despite its technical challenges [16].

A crucial characteristic of metabolic systems is that they maintain dynamic homeostasis through constant turnover of constituents, with metabolites existing in a state of continuous synthesis and degradation rather than static pools [18]. This means that the absolute concentration of a metabolite represents a balance between its production and consumption, providing no direct information about the rates of these opposing processes [18] [16]. Understanding this dynamic nature is essential for appreciating why fluxes cannot be determined from static measurements alone.

Key Reasons Why Direct Measurement Is Impossible

Table 1: Fundamental Barriers to Direct Flux Measurement

| Barrier | Explanation | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Isolatable Nature | Fluxes are rates, not physical entities that can be isolated or purified | Cannot be amplified, concentrated, or detected with physical instruments |

| Network Embeddedness | Each flux is constrained by multiple interconnected pathways | Changing one flux affects others, preventing independent measurement |

| Dynamic Homeostasis | Metabolite concentrations remain relatively constant despite high flux rates | Static concentration measurements reveal net balance but not unidirectional fluxes |

| Cellular Compartmentalization | Metabolic pathways span multiple intracellular compartments | Creates subcellular flux gradients that cannot be directly sampled |

The non-isolatable nature of reaction rates presents the most fundamental barrier. While metabolites, enzymes, and transcripts can be extracted, quantified, and characterized ex vivo, the rate at which substrates flow through a pathway exists only as a dynamic property of the intact system [16]. This property vanishes when cellular integrity is compromised during sample collection, making it impossible to "capture" a flux for direct measurement in the same way one can isolate a metabolite for mass spectrometric analysis [16].

Additionally, metabolic fluxes exhibit network embeddedness, meaning that each flux is constrained by mass conservation and connectivity with other fluxes in the network [10] [19]. In constraint-based modeling approaches, this is formalized through the stoichiometric matrix (S), which describes how metabolites connect through biochemical reactions [19]. The relationship Sv = 0 (where v is the flux vector) at metabolic steady state means that fluxes are interdependent—measuring one flux directly would require knowing several others, creating a circular problem [19].

The Tracer Methodology: Indirect Flux Inference

Basic Principles of Isotope Tracer Analysis

Stable isotope tracing provides a sophisticated methodological workaround to the direct measurement barrier. By introducing isotopically labeled substrates (e.g., containing heavy isotopes such as ^13^C or ^2^H) into a biological system, researchers can track the fate of atoms through metabolic networks based on the unique labeling patterns that emerge in downstream metabolites [17] [16]. These patterns encode information about the activity of upstream metabolic pathways because enzymes rearrange substrate atoms in specific and predictable ways [16]. The fundamental premise is that the flow of isotopes through metabolic networks mirrors the flow of mass, thereby providing a window into flux distributions that would otherwise remain invisible [16].

The tracer methodology relies on one of four basic model structures or their combinations: (1) tracer dilution in single-pool systems, (2) tracer dilution in multiple-pool systems, (3) tracer incorporation with single precursor, or (4) tracer incorporation with multiple precursors, operating in either steady or non-steady states [18]. The choice of model structure depends on the biological question and system under investigation, with each approach having distinct advantages and limitations for flux inference [18].

Figure 1: The Fundamental Workflow of Metabolic Flux Analysis. Isotope tracers are introduced into a living system, where they undergo metabolic transformations. The resulting isotopomer patterns in metabolites are measured experimentally, and computational models use these patterns to infer metabolic fluxes.

Analytical Platforms for Isotope Detection

The detection and quantification of isotope labeling relies primarily on two analytical platforms: mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [16]. Each platform offers distinct advantages for different applications in flux analysis. MS-based platforms provide exceptional sensitivity, enabling detection of low-abundance metabolites from limited sample volumes, which is particularly valuable for mouse studies and clinical applications where sample availability is constrained [16]. Advancements in gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) have significantly expanded the scope of measurable metabolites, while high-resolution MS and tandem MS (MS/MS) instruments can provide positional labeling information by fragmenting parent metabolites [16].

NMR spectroscopy, despite its inherently lower sensitivity compared to MS, offers unique capabilities for in vivo flux analysis, particularly its ability to assess position-specific isotope enrichments and directly differentiate between ^2^H and ^13^C nuclei without requiring chemical derivatization or separation [16]. Recent developments in hyperpolarized ^13^C magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have improved NMR sensitivity by approximately 10,000-fold, enabling real-time monitoring of metabolic processes in living tissues [16]. This breakthrough has opened new possibilities for characterizing metabolic alterations in cancer, cardiac dysfunction, and neurological diseases, though the short hyperpolarization lifetime currently restricts analysis to initial pathway steps [16].

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies in Flux Analysis

Hepatic Gluconeogenesis and TCA Cycle Fluxes

The liver serves as a key metabolic hub, making it a frequent subject of in vivo flux analysis studies. Research on hepatic metabolism has revealed substantial tracer-dependent discrepancies in flux estimates, particularly for pyruvate cycling fluxes, when using different isotopic tracers. In studies with fasted mice, estimates of liver pyruvate cycling fluxes (V~PC.L~, V~PCK.L~, and V~PK+ME.L~) were significantly higher when using [^13^C~3~]propionate compared to [^13^C~3~]lactate tracers under similar modeling assumptions [17]. This incongruence demonstrates how methodological choices can lead to divergent biological interpretations despite examining the same underlying physiology.

Further investigation revealed that these discrepancies emanate, at least partially, from peripheral tracer recycling and incomplete isotope equilibration within the citric acid cycle [17]. When researchers expanded their models to include additional labeling measurements and relaxed conventional assumptions, they found that labeled lactate and urea (an indicator of circulating bicarbonate) were significantly enriched in plasma following tracer infusion [17]. This recycling of labeled metabolites from peripheral tissues back to the liver artificially influenced flux estimates, particularly for pyruvate cycling, highlighting the complex inter-tissue interactions that complicate in vivo flux analysis [17].

Table 2: Experimental Data Showing Tracer-Dependent Flux Differences in Mouse Liver

| Experimental Condition | Tracer Used | Pyruvate Cycling Flux | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fasted state (base model) | [^13^C~3~]lactate | Lower | Incongruent flux estimates between different tracers |

| Fasted state (base model) | [^13^C~3~]propionate | Higher | Highlighted sensitivity to methodological assumptions |

| Fasted state (expanded model) | [^13^C~3~]lactate | Significant (reconciled) | Accounting for metabolite recycling improved consistency |

| Fasted state (expanded model) | [^13^C~3~]propionate | Significant (reconciled) | Fewer constraining assumptions provided more robust estimates |

Multi-Tracer Approaches for Comprehensive Flux Mapping

Recognition of the limitations inherent in single-tracer experiments has driven the development of multi-tracer approaches that provide more comprehensive flux mapping [16]. Modern in vivo MFA studies frequently infuse cocktails of different isotope tracers specifically tailored to the pathways of interest [16]. For example, combined administration of ^2^H and ^13^C tracers has been used to concurrently assess glycolytic/gluconeogenic fluxes, TCA cycle activity, and anaplerotic fluxes in liver and cardiac tissue [16]. In human subjects, similar approaches have quantified glucose turnover, hepatic TCA cycle activity, and ketone turnover during starvation and obesity [16].

The technical requirements of these multi-tracer experiments have prompted innovations in surgical techniques and experimental design. Implantation of dual arterial-venous catheters now enables simultaneous tracer infusion and plasma sampling in conscious, unrestrained mice, avoiding physiological alterations caused by anesthesia or stress that can obscure experimental effects [16]. These methodological refinements are crucial for generating reliable data for model-based flux estimation, particularly when studying subtle metabolic phenotypes or responses to pharmacological interventions.

Technical and Modeling Challenges

Methodological Complexities in In Vivo Studies

In vivo flux analysis introduces several technical challenges rarely encountered in cell culture studies. The continuous exchange of metabolites between tissues means that isotopes introduced into the circulation are taken up and metabolized by multiple organs simultaneously, with the products of these reactions potentially being released back into circulation and taken up by other tissues [17] [16]. This secondary tracer recycling can profoundly influence labeling patterns and flux estimates if not properly accounted for in models [17]. For instance, studies using [^13^C~3~]propionate found significant enrichment of plasma lactate and urea, demonstrating that recycled metabolites re-enter the liver and influence apparent flux measurements [17].

Another significant challenge involves incomplete isotope equilibration within metabolic compartments. Traditional models often assume complete equilibration of four-carbon intermediates in the citric acid cycle, but evidence suggests this assumption may not hold for all tracers [17]. Specifically, ^13^C tracers that enter the CAC downstream of fumarate (e.g., lactate or alanine) show lesser interconversion with symmetric four-carbon intermediates compared to those entering upstream of succinate (e.g., propionate) [17]. This differential equilibration contributes to the tracer-dependent flux discrepancies observed in experimental studies and must be addressed through more sophisticated modeling approaches.

Mathematical Modeling and Assumption Dependencies

Flux estimation ultimately depends on mathematical models that relate measurable isotope labeling patterns to unobservable metabolic fluxes [10] [16]. Two predominant modeling frameworks have emerged: (1) constraint-based modeling, which incorporates reaction stoichiometry and thermodynamic constraints to define a solution space of possible fluxes, and (2) kinetic modeling, which simulates metabolite concentration changes over time using mechanistic rate laws and kinetic parameters [19]. For in vivo ^13^C-MFA, regression-based approaches that find the best-fit flux solution to experimentally measured isotopomer distributions are most common [16].

A critical challenge in model-based flux estimation is the dependency on underlying assumptions that must be introduced to make the analysis tractable [17]. Common assumptions include complete isotope equilibration in specific metabolic pools, negligible effects of secondary tracer recycling, and steady-state metabolic conditions [17]. The validity of these assumptions varies across biological contexts, and their appropriateness must be rigorously tested. Studies have demonstrated that relaxing conventional assumptions—for example, by including more labeling measurements and accounting for metabolite exchange between tissues—can reconcile apparently divergent flux estimates obtained with different tracers [17]. This highlights how flux values are not purely observational measurements but are instead model-informed estimates that depend on the structural and parametric assumptions of the analytical framework.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for In Vivo Flux Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | [^13^C~3~]lactate, [^13^C~3~]propionate, ^2^H-water | Metabolic labeling for pathway tracing |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS, LC-MS/MS, NMR spectroscopy | Detection and quantification of isotope enrichment |

| Surgical Tools | Arterial-venous catheters for conscious mice | Minimally invasive sampling during tracer infusion |

| Software Platforms | INCA, COBRA Toolbox, MEMOTE | Flux estimation, model validation, and quality control |

| Model Repositories | BiGG Models, BioModels, MetaNetX | Access to curated metabolic reconstructions |

| Validation Standards | MIRIAM, MIASE, SBO terms | Model annotation and simulation standards |

The experimental workflow for in vivo flux analysis requires specialized reagents and tools spanning from isotope administration to computational analysis [16]. Stable isotope tracers represent the fundamental starting point, with selection of appropriate tracers being critical for targeting specific metabolic pathways [16]. For hepatic metabolism studies, [^13^C~3~]lactate and [^13^C~3~]propionate have been particularly valuable, though their differential metabolism requires careful interpretation [17].

Analytical instrumentation for detecting isotope enrichment has seen significant advancements, with GC-MS and LC-MS/MS platforms now capable of measuring low-abundance metabolites from small sample volumes [16]. NMR spectroscopy remains valuable for position-specific enrichment analysis, particularly with the development of hyperpolarization techniques that dramatically enhance sensitivity [16].

Computational tools have become indispensable for flux estimation from complex isotopomer data. Software such as INCA (Isotopomer Network Compartmental Analysis) enables flexible modeling of isotope labeling experiments and statistical evaluation of flux solutions [17] [16]. The COBRA (COnstraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) framework provides tools for constraint-based modeling and flux balance analysis [20]. Quality control resources such as MEMOTE (MEtabolic MOdel TEsts) help standardize model evaluation and ensure biological consistency [20].

Model Validation and Selection Frameworks

Critical Importance of Validation in Flux Analysis

Given the model-dependent nature of flux estimation, validation frameworks are essential for establishing confidence in flux predictions [10] [14]. The traditional approach to model selection in ^13^C-MFA has relied on the χ^2^-test for goodness-of-fit, which evaluates how well a model reproduces the experimental data used for parameter estimation [14]. However, this approach presents several limitations, particularly its sensitivity to errors in measurement uncertainty estimates and its tendency to favor increasingly complex models when applied to the same dataset used for fitting [14].

Validation-based model selection has emerged as a more robust alternative that addresses these limitations [14]. This approach uses independent "validation" data that were not used during model fitting to evaluate model performance, thereby protecting against overfitting and providing a more realistic assessment of predictive capability [14]. Simulation studies demonstrate that validation-based methods consistently select the correct model structure in a way that is independent of errors in measurement uncertainty, unlike χ^2^-test-based approaches whose outcomes vary substantially with assumed measurement error [14].

Figure 2: The Traditional Model Development Cycle in MFA. Models are constructed, fitted to estimation data, and evaluated using a χ²-test. If rejected, the model structure is revised and the process repeats. This approach can lead to overfitting when the same data is used for both fitting and model selection.

Community Standards for Model Quality

The metabolic modeling community has developed community-driven standards to improve model quality, reproducibility, and interoperability [20]. The Minimum Information Required In the Annotation of biochemical Models (MIRIAM) establishes guidelines for model annotation, while the Systems Biology Ontology (SBO) provides standardized terms for classifying model components [20]. For model sharing, the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) has emerged as the de facto standard format, enabling machine-readable encoding of biological models [20].

The MEMOTE suite represents a specialized testing framework for metabolic models, evaluating multiple aspects of model quality including component namespaces, biochemical consistency, network topology, and version control [20]. These tests check for fundamental biochemical principles such as mass and charge balance across reactions while also assessing the comprehensiveness of metabolic coverage and annotation [20]. Adoption of such community-defined standards is increasingly expected for newly published models and enhances the reliability of flux analysis findings.

The fundamental impossibility of directly measuring metabolic fluxes in vivo has driven the development of increasingly sophisticated methodological workarounds that combine isotope tracing with mathematical modeling. While these approaches have proven remarkably powerful for quantifying pathway activities in living organisms, they remain fundamentally model-dependent estimations rather than direct measurements. The resulting flux values are consequently influenced by methodological choices including tracer selection, analytical instrumentation, and modeling assumptions, creating challenges for comparison across studies and biological contexts.

Future advancements in in vivo flux analysis will likely focus on addressing key limitations in current methodologies. Further development of validation-based model selection approaches will improve the robustness of flux estimates, particularly when true measurement uncertainties are difficult to characterize [14]. Multi-tracer protocols that provide complementary information about pathway activities will continue to expand, enabled by analytical platforms capable of deconvoluting complex labeling patterns from multiple isotopic sources [16]. Additionally, community standards for model quality and annotation will play an increasingly important role in ensuring that flux estimates are reproducible and biologically meaningful [20].

For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding the inherent limitations and assumptions of flux measurement approaches is essential for appropriate interpretation of MFA data. Rather than viewing flux estimates as direct measurements, they are more accurately understood as model-informed inferences whose validity depends on both experimental design and analytical choices. This nuanced perspective allows for more critical evaluation of flux data and more informed decisions about targeting metabolic pathways for therapeutic intervention.

Defining Model Validation vs. Model Selection in Metabolic Networks

In the study of cellular metabolism, mathematical models are indispensable for quantifying the integrated functional phenotype of a living system: its metabolic fluxes. Metabolic fluxes represent the rates at which metabolites are converted to other metabolites through biochemical reactions, and they emerge from complex interactions across the genome, transcriptome, and proteome [10]. Since these intracellular reaction rates cannot be measured directly, researchers rely on constraint-based modeling frameworks—primarily 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)—to estimate or predict them [10] [21]. Both methodologies operate on a defined metabolic network model and assume the system is at a metabolic steady state, meaning metabolite concentrations and reaction rates are constant [10]. The accuracy of the resulting flux maps, however, is profoundly dependent on two critical and distinct processes: model validation and model selection. Model validation concerns assessing the reliability and accuracy of flux estimates from a chosen model, while model selection involves choosing the most statistically justified model architecture from among competing alternatives [10] [14]. Despite their importance, these practices have been underappreciated in the flux analysis community, and a lack of standardized approaches can undermine confidence in model-derived biological conclusions [10]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of model validation and model selection, detailing their methodologies, applications, and the experimental data required to perform them robustly.

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is Model Validation?

Model validation is the process of evaluating the goodness-of-fit of a single, chosen metabolic model to experimental data. It tests whether a given model's predictions are consistent with observed measurements, thereby assessing the model's reliability and the accuracy of its flux estimates [10]. In 13C-MFA, validation often involves a χ2-test of goodness-of-fit to compare simulated Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) against experimentally measured MIDs [10] [14]. For FBA, validation can be more qualitative, such as checking if a model correctly predicts the essentiality of nutrients for growth or comparing predicted growth rates against measured ones [10]. The central question of validation is: "Does this specific model adequately explain the data?"

What is Model Selection?

Model selection is the process of discriminating between alternative model architectures to identify the one that is best supported by the data. This involves making choices about which reactions, compartments, and metabolites to include in the metabolic network model itself [10] [14]. Model selection is necessary because different biological hypotheses or network topologies can be represented by different model structures. The process can be informal, based on trial-and-error and the χ2-test, or formalized using approaches like validation-based model selection, which uses an independent dataset to choose the model with the best predictive performance [14]. The central question of model selection is: "Which model structure among several candidates is the most justified?"

Table 1: Conceptual Comparison between Model Validation and Model Selection

| Aspect | Model Validation | Model Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Core Objective | Assess the fit and reliability of a single model | Choose the best model structure from multiple candidates |

| Central Question | "Is this model valid and reliable?" | "Which model is the best?" |

| Typical Methods | χ2-test of goodness-of-fit, growth/no-growth comparison | Validation-based selection, χ2-test with degrees of freedom adjustment |

| Primary Outcome | Confidence in the model's flux estimates | Identification of the most statistically supported network architecture |

| Role in Workflow | Final checking step after model is built and fitted | Upstream structural decision-making process |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The experimental foundation for both validation and selection in 13C-MFA is the isotope labeling experiment. The general workflow begins with cultivating cells on a growth medium containing 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose or glutamine) [21]. After the cells reach a metabolic and isotopic steady state (for stationary MFA), they are quenched and metabolites are extracted [21]. The mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of intracellular metabolites are then measured using techniques like mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [21] [22]. These measured MIDs are the key experimental data used for both fitting and evaluating models.

Workflow for Model Validation and Selection

The following diagram illustrates the integrated iterative process of model development, selection, and validation in metabolic flux analysis.

Protocol for Traditional Model Validation

The most common method for validating a 13C-MFA model is the χ2-test of goodness-of-fit [10] [14].

- Model Fitting: A metabolic network model is fitted to the experimental MID data (the "training" or "estimation" data) by varying the flux values to minimize the sum of squared residuals between measured and simulated MIDs [10] [22].

- Goodness-of-Fit Calculation: The weighted sum of squared residuals (SSR) is calculated. If the model's assumptions are correct and measurement errors are accurately known, this statistic follows a χ2-distribution [14].

- Statistical Testing: The calculated SSR is compared to a critical value from the χ2-distribution. The number of degrees of freedom is typically calculated as the number of data points minus the number of independently fitted parameters [14].

- Interpretation: If the SSR is below the critical value (p-value > 0.05), the model is not statistically rejected and is considered valid. If the SSR is too high (p-value < 0.05), the model is rejected, indicating a poor fit to the data [14].

Protocol for Validation-Based Model Selection

The traditional iterative modeling cycle can lead to overfitting, where a model is tailored to the noise in a single dataset [14]. Validation-based model selection offers a more robust alternative.

- Data Splitting: The experimental MID data is split into two independent sets: a training dataset used for model fitting and a validation dataset held back for testing [14].

- Model Fitting and Comparison: Multiple candidate model structures (e.g., with or without a specific reaction like pyruvate carboxylase) are fitted to the training dataset.

- Prediction and Selection: Each fitted model is used to predict the validation dataset. The model that achieves the best predictive performance (i.e., the smallest prediction error on the validation data) is selected as the most appropriate one [14].

- Uncertainty Quantification (Advanced): Prediction uncertainty can be quantified using methods like prediction profile likelihood to ensure the validation data has an appropriate level of novelty compared to the training data [14].

Table 2: Comparison of Selection and Validation Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2-test Validation | Tests if model-predicted MIDs match measured MIDs within expected error. | Well-established; provides a clear statistical criterion for model rejection. | Highly sensitive to accurate knowledge of measurement errors; can lead to model rejection if errors are underestimated [14]. |

| FBA Growth/No-Growth Validation | Tests if model predicts viability on specific substrates. | Computationally simple; useful for testing network completeness. | Qualitative; does not test accuracy of internal flux values [10]. |

| χ2-test based Selection | Iterative model revision until the first model passes the χ2-test. | Simple to implement and understand. | Informal; prone to overfitting; selection depends on the often-uncertain measurement error magnitude [14]. |

| Validation-based Selection | Chooses the model with the best predictive performance on an independent dataset. | Robust to inaccuracies in measurement error estimates; protects against overfitting [14]. | Requires more experimental data to be split into training and validation sets. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Software

Successful execution of MFA and its associated validation/selection procedures requires a suite of specialized reagents and software tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for MFA

| Item Name | Type | Function in MFA, Validation, and Selection |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Research Reagent | Tracer compounds (e.g., [U-13C]-glucose, [1-13C]-glutamine) fed to cells to generate distinctive mass isotopomer distribution (MID) patterns for flux determination [21] [22]. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Instrument | Primary technology for measuring the MID and concentration of metabolites extracted from cells. Provides the essential quantitative data for model fitting and validation [21]. |

| 13CFLUX2 | Software | A widely used software package for the design, simulation, and evaluation of 13C labeling experiments for flux calculation under metabolic and isotopic steady-state conditions [21]. |

| INCA | Software | The first software capable of performing Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) by simulating transient isotope labeling experiments, useful for systems where achieving isotopic steady state is difficult [21]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software | A MATLAB-based toolkit for performing Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA), including FBA, Flux Variability Analysis, and basic model quality checks [10]. |

| MEMOTE | Software | A test suite for standardized quality assurance and validation of genome-scale metabolic models, checking for thermodynamic consistency and biomass precursor synthesis capability [10]. |

Model validation and model selection are distinct but deeply interconnected processes that are fundamental to building confidence in metabolic flux predictions. Model validation acts as a final quality check on a single model's performance, while model selection is an upstream process of choosing the most plausible network structure from a set of candidates. The traditional reliance on χ2-testing for both purposes is fraught with difficulty, primarily due to its sensitivity to often-uncertain measurement error estimates [14]. The adoption of validation-based model selection, which leverages independent data to test model predictions, represents a more robust framework that is less susceptible to these errors. As the scale and complexity of metabolic models continue to grow, the rigorous application of these advanced statistical frameworks will be paramount. This will enhance the reliability of flux maps in both fundamental biological research and applied biotechnological contexts, such as the rational design of high-yielding microbial strains for therapeutic protein or metabolite production [10].

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) has emerged as a cornerstone technique in systems biology for quantifying intracellular reaction rates (fluxes) that define the metabolic phenotype of cells [15]. At the heart of most MFA methodologies lies the steady-state assumption, a fundamental prerequisite that enables researchers to solve the mathematically underdetermined systems of metabolic networks. The steady-state assumption encompasses two distinct but often interrelated concepts: metabolic steady state and isotopic stationary state [15] [23]. Under metabolic steady state, all metabolic fluxes and metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, while isotopic stationary state describes the condition where isotope incorporation from labeled substrates has reached equilibrium within intracellular metabolite pools [15]. These assumptions form the bedrock upon which different MFA approaches are built, each with specific requirements and implications for experimental design and computational modeling.

The critical importance of these steady-state assumptions extends across multiple research domains, from metabolic engineering and biotechnology to drug discovery and cancer research [15] [24]. In metabolic engineering, MFA has been instrumental in developing high-producing strains for compounds like lysine, while in pharmacology, it helps identify metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer cells and understand mechanisms of drug action and resistance [10] [24]. The reliability of flux estimates in these applications depends heavily on both the validity of the steady-state assumptions during experimentation and the proper selection of mathematical models that represent the underlying metabolism [10] [8]. This guide systematically compares the primary MFA methodologies based on their steady-state requirements, providing experimental protocols, validation frameworks, and analytical tools essential for researchers working at the intersection of metabolism and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of MFA Methods and Steady-State Requirements

Classification of MFA Techniques Based on Steady-State Assumptions

MFA methodologies can be categorized based on their specific requirements for metabolic and isotopic steady states, which directly influence their experimental timelines, computational complexity, and application domains [15]. The table below summarizes the defining characteristics of the predominant MFA approaches:

Table 1: Classification of Metabolic Flux Analysis Methods by Steady-State Requirements

| Flux Method | Abbreviation | Labeled Tracers | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State | Typical Experimental Duration | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis | FBA | No | Yes | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Low |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis | MFA | No | Yes | Not Applicable | Hours to Days | Low |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis | 13C-MFA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Hours to Days (until isotopic steady state) | Medium |

| Isotopic Nonstationary MFA | INST-MFA | Yes | Yes | No | Seconds to Minutes | High |

| Dynamic Metabolic Flux Analysis | DMFA | No | No | Not Applicable | Multiple time intervals | High |

| 13C-Dynamic MFA | 13C-DMFA | Yes | No | No | Multiple time intervals | Very High |

| COMPLETE-MFA | COMPLETE-MFA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Hours to Days | Medium-High |

As illustrated in Table 1, the technical requirements and implementation complexity vary significantly across methods. Traditional 13C-MFA requires both metabolic and isotopic steady states, meaning that cells must be cultivated for sufficient time (typically several hours to a day for mammalian cells) to ensure full incorporation and stabilization of the isotopic label [15]. In contrast, INST-MFA maintains the metabolic steady-state assumption but leverages transient isotopic labeling data collected before the system reaches isotopic stationarity, thereby shortening experimental timelines but increasing computational demands due to the need to solve differential equations rather than algebraic balance equations [15]. The dynamic approaches (DMFA and 13C-DMFA) represent the most complex category, as they forgo both steady-state assumptions and instead divide experiments into multiple time intervals to capture flux transients, resulting in substantial increases in data requirements and computational complexity [15].

Quantitative Comparison of Methodological Capabilities

The choice between MFA methodologies involves trade-offs between resolution, temporal scope, and practical implementation constraints. The following table compares key performance metrics and application considerations:

Table 2: Performance Metrics and Application Considerations for MFA Methods

| Flux Method | Flux Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Network Scale | Data Requirements | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBA | Low (Predictive) | None | Genome-Scale | Growth rates, uptake/secretion rates | Genome-scale prediction, constraint-based modeling |

| MFA | Low (Deterministic) | None | Small-Scale (Central metabolism) | Extracellular fluxes | Initial flux estimation, network validation |

| 13C-MFA | High | Single time point | Small-Scale (Central metabolism) | Extracellular fluxes + Isotopic labeling | Most applications in biotechnology and systems biology |

| INST-MFA | High | Multiple early time points | Small-Scale (Central metabolism) | Time-course isotopic labeling | Systems with slow isotopic stationarity, plant metabolism |

| DMFA | Medium | Multiple time intervals | Small-Scale (Central metabolism) | Time-course extracellular fluxes | Dynamic processes, fermentation optimization |

| 13C-DMFA | High | Multiple time intervals | Small-Scale (Central metabolism) | Time-course extracellular fluxes + isotopic labeling | Dynamic flux analysis with pathway resolution |

| COMPLETE-MFA | Very High | Single time point | Small-Scale (Central metabolism) | Extracellular fluxes + multiple tracer labeling | High-precision flux mapping, network validation |

As evidenced in Table 2, 13C-MFA remains the most widely applied method due to its well-established protocols and robust computational frameworks, making it particularly suitable for routine applications in biotechnology and systems biology [15]. However, INST-MFA offers significant advantages for studying systems where reaching isotopic steady state is impractical due to experimental constraints or slow metabolic turnover, as demonstrated in plant metabolism studies where it has been used to quantify photorespiratory fluxes [25]. The emerging COMPLETE-MFA approach, which utilizes multiple singly labeled tracers simultaneously, provides the highest flux resolution and has been used to generate exceptionally precise flux maps for model organisms like E. coli [15] [26].

Experimental Design and Workflows

Generalized Experimental Protocol for Steady-State MFA

The implementation of MFA under steady-state conditions follows a systematic workflow with specific variations depending on the chosen methodology. The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for steady-state MFA approaches:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for steady-state 13C-MFA illustrating key stages from sample preparation through computational analysis.

The experimental protocol begins with cell cultivation in an unlabeled medium to establish metabolic steady state, followed by transfer to a medium containing 13C-labeled substrates (tracers) [15]. For 13C-MFA, cells are cultivated until isotopic steady state is reached, which can require several hours to days depending on the biological system [15]. For INST-MFA, samples are collected at multiple early time points (seconds to minutes) during the transient labeling period before isotopic steady state is achieved [15]. The quenching and extraction step rapidly halts metabolic activity and extracts intracellular metabolites, preserving the labeling patterns for subsequent analysis [15] [27]. The analytical phase typically employs mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to measure mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs), which represent the fractional abundances of different isotopic isomers of metabolites [15] [14]. Finally, computational modeling uses these MIDs, along with extracellular flux measurements, to estimate intracellular fluxes through fitting procedures that minimize the difference between simulated and experimental labeling patterns [15] [23].

Specialized Protocol: INST-MFA for Plant Metabolism

The application of INST-MFA to plant systems illustrates how methodological adaptations address domain-specific challenges. A recent study investigating the link between photorespiration and one-carbon metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana employed the following specialized protocol [25]:

Plant Growth and Labeling: Arabidopsis thaliana plants were grown under controlled conditions and exposed to 13CO2 labeling at different O2 concentrations (modulating photorespiration) [25].

Time-Course Sampling: Leaf samples were collected at multiple time points (seconds to minutes) after 13CO2 exposure to capture the transient labeling dynamics before isotopic steady state [25].

Metabolite Extraction and Analysis: Metabolites were extracted using rapid quenching methods and analyzed by LC-MS to determine time-dependent MIDs [25].

Flux Estimation: Computational flux estimation was performed using INST-MFA algorithms that simulate the time-course labeling patterns and optimize fluxes to fit the experimental data [25].

This approach revealed that approximately 5.8% of assimilated carbon passes to one-carbon metabolism under ambient photorespiratory conditions, with serine serving as the primary carbon flux from photorespiration to one-carbon metabolism [25]. The successful application demonstrates how INST-MFA enables flux quantification in systems where achieving isotopic steady state is challenging or where dynamic metabolic processes are of interest.

Model Validation and Selection Frameworks

The Critical Role of Model Selection in MFA

The accuracy of flux estimates in MFA depends critically on selecting an appropriate metabolic network model that correctly represents the underlying biochemistry [10] [8]. Model selection involves choosing which compartments, metabolites, and reactions to include in the metabolic network model used for flux estimation [8] [14]. Traditional approaches to model selection often rely on iterative trial-and-error processes, where models are successively modified and evaluated against the same dataset using goodness-of-fit tests, particularly the χ2-test [8] [14]. However, this practice can lead to overfitting (selecting overly complex models) or underfitting (selecting overly simple models), both of which result in poor flux estimates [8]. The problem is compounded by uncertainties in measurement errors, which can significantly influence model selection outcomes when using χ2-based methods [8] [14].

Validation-Based Model Selection Approach

Recent methodological advances have introduced validation-based model selection as a robust alternative to traditional χ2-testing [8] [14]. This approach addresses key limitations of conventional methods by utilizing independent validation data not used during model fitting. The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework of validation-based model selection:

Diagram 2: Validation-based model selection framework showing how independent estimation and validation datasets are used to select models with the best predictive performance.

The validation-based approach partitions experimental data into estimation data (Dest), used for model fitting, and validation data (Dval), used exclusively for model evaluation [8]. This partition is typically done by reserving data from distinct experimental conditions or different tracer inputs for validation [8]. For each candidate model, parameters (fluxes) are estimated using Dest, and then the model's predictive performance is evaluated by calculating the sum of squared residuals (SSR) between the model predictions and the independent Dval [8]. The model achieving the smallest SSR with respect to Dval is selected as the most appropriate [8]. Simulation studies have demonstrated that this method consistently selects the correct metabolic network model despite uncertainties in measurement errors, whereas traditional χ2-testing methods show high sensitivity to error magnitude assumptions [8] [14].

Comparative Performance of Model Selection Methods

The table below compares different model selection approaches based on their statistical properties and practical implementation:

Table 3: Comparison of Model Selection Methods for MFA

| Method | Selection Criteria | Robustness to Error Uncertainty | Risk of Overfitting | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First χ2 | Selects simplest model that passes χ2-test | Low | Low | Low |

| Best χ2 | Selects model passing χ2-test with greatest margin | Low | Medium | Low |

| AIC | Minimizes Akaike Information Criterion | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| BIC | Minimizes Bayesian Information Criterion | Medium | Low | Medium |

| Validation | Minimizes prediction error on independent data | High | Low | High |

As shown in Table 3, validation-based model selection offers superior robustness to uncertainties in measurement errors, which is particularly valuable since estimating true measurement uncertainties can be challenging in practice [8] [14]. The method has been successfully applied in isotope tracing studies on human mammary epithelial cells, where it identified pyruvate carboxylase as a key model component [8]. While validation-based selection requires more experimental data and computational resources, it provides enhanced confidence in flux estimation results and facilitates more reliable biological conclusions [8].

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Successful implementation of MFA under steady-state conditions requires specialized computational tools, analytical instrumentation, and biochemical reagents. The following table catalogues key solutions essential for conducting MFA studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MFA

| Category | Specific Solution | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | 13C-labeled substrates | Create distinct labeling patterns for flux determination | [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, 13C-CO2, 13C-NaHCO3 [15] [25] |

| Analytical Instruments | Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Measure mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) | GC-MS, LC-MS, orbitrap instruments [15] [14] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Measure isotopic labeling patterns | Provides positional labeling information [15] | |

| Computational Tools | Flux Analysis Software | Perform flux calculations and statistical analysis | OpenFLUX, 13CFLUX2, INCA, METRAN [15] [26] |

| Model Validation Tools | Assess model quality and performance | χ2-test, validation-based selection [8] [14] | |

| Biological Materials | Cell Culture Systems | Maintain metabolic steady state during labeling | Microbial, mammalian, or plant systems [15] [25] |

| Quenching Solutions | Rapidly halt metabolic activity | Cold methanol, other organic solvents [15] [27] |