Modular Vector Design for Broad-Host-Range Synthetic Biology: Expanding the Chassis Landscape for Biomedical Innovation

This article explores the paradigm shift in synthetic biology from a narrow focus on traditional model organisms to a broad-host-range approach that treats the microbial chassis as a central, tunable...

Modular Vector Design for Broad-Host-Range Synthetic Biology: Expanding the Chassis Landscape for Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm shift in synthetic biology from a narrow focus on traditional model organisms to a broad-host-range approach that treats the microbial chassis as a central, tunable design parameter. We examine the foundational principles of modular vector systems, such as the Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA), and their application in enabling genetic engineering across diverse bacterial species and chloroplasts. The content details methodological advances in conjugation and cloning, addresses key challenges like the chassis effect and host-circuit interactions, and provides a comparative analysis of vector performance and part functionality across different hosts. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how these tools enhance the functional versatility of engineered biological systems for applications in biomanufacturing, therapeutic discovery, and environmental health.

Beyond E. coli: The Foundational Shift to Broad-Host-Range Systems

Defining Broad-Host-Range Synthetic Biology and Its Core Principles

Broad-host-range synthetic biology is an advanced framework in genetic engineering that redefines the role of microbial hosts in biological design. Unlike traditional synthetic biology that focuses on optimizing genetic constructs within a limited set of well-characterized model organisms, broad-host-range synthetic biology treats host selection as a crucial, tunable design parameter [1]. This approach leverages microbial diversity to enhance the functional versatility of engineered biological systems, enabling a larger design space for biotechnology applications in biomanufacturing, environmental remediation, and therapeutics [1]. The development of shareable, modular genetic tools that function across diverse microbial species is fundamental to this paradigm, allowing researchers to harness unique metabolic capabilities found in non-model organisms.

Core Principles of Broad-Host-Range Synthetic Biology

Host Flexibility and Chassis Selection

The foundational principle of broad-host-range synthetic biology is the treatment of microbial chassis as an active design variable rather than a passive platform [1]. This recognizes that host physiology significantly influences the behavior of engineered genetic devices through resource allocation, metabolic interactions, and regulatory crosstalk. By expanding chassis selection beyond traditional model organisms, researchers can access specialized metabolic pathways, unique environmental adaptations, and industrially relevant capabilities found in non-model microbes. This flexibility enables the matching of host capabilities with specific application requirements, whether for environmental bioremediation, specialized metabolite production, or biosensing.

Standardization and Modularity

Standardized genetic architecture enables the exchange and recombination of genetic parts across different host systems. Modular vector design follows specified standards that allow for the predictable assembly of genetic constructs and their transfer between diverse organisms [2] [3]. The Modular Cloning (MoClo) system exemplifies this principle, using a hierarchical assembly strategy based on Golden Gate cloning with Type IIS restriction enzymes [3]. This creates a standardized syntax where genetic elements with defined four-nucleotide overhangs can be efficiently assembled in precise order and orientation. Such standardization enables the research community to build shareable, reusable genetic toolkits that function across taxonomic boundaries.

Orthogonal Genetic Parts and Systems

Orthogonality ensures that engineered genetic systems function consistently without interfering with host physiology or being compromised by host-specific regulation. This principle requires the identification and engineering of genetic elements that maintain their functions across diverse hosts. Key orthogonal systems include:

- Origin of replication (ori) systems that function across taxonomic groups [4]

- Site-specific integration systems that enable stable chromosomal insertion in non-model hosts [2]

- Promoter and ribosome binding sites with cross-species functionality

- Selection markers effective in diverse microbes [2] [5]

Resource Efficiency and Reduced Metabolic Burden

Effective broad-host-range systems must minimize the metabolic burden on host cells to maintain stability and function. This involves optimizing genetic elements for efficient resource usage, including codon optimization for different hosts, careful selection of origins of replication with appropriate copy numbers, and implementing regulatory systems that precisely control expression levels [2]. Vectors designed with these considerations reduce the fitness cost to host cells, enabling long-term stability of engineered functions without selective pressure.

Essential Genetic Toolkits and Modular Vectors

Vector Architecture and Components

Broad-host-range vectors are typically constructed with standardized modular architecture. A representative vector system for actinobacteria illustrates this design, consisting of five distinct modules [2]:

- E. coli origin of replication and Flp recombination target (FRT) recognition site

- Antibiotic resistance marker with expression functional in both E. coli and the target host

- RP4 origin of transfer (oriT) and a second FRT site

- Integration system cassette (integrases and corresponding attP site) for site-specific chromosomal integration

- Multiple cloning site compatible with various DNA assembly methods

This modular design enables researchers to mix and match components based on the specific requirements of their target host and experimental goals.

Broad-Host-Range Plasmid Systems

Table 1: Common Broad-Host-Range Plasmid Incompatibility Groups and Their Host Range

| Incompatibility Group | Representative Replicon | Gram Staining Compatibility | Example Host Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| IncP | RK2 | Gram-negative | Acinetobacter spp., Pseudomonas spp., Rhizobium spp. [4] |

| IncQ | RSF1010, R300B, R1162 | Gram-negative and Gram-positive | Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, Streptomyces lividans, Mycobacterium smegmatis [4] |

| IncW | pSa, pR388 | Gram-negative | Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas spp. [4] |

| pBBR1-based | pBBR1 | Gram-negative | Bordetella spp., Brucella spp., Rhizobium meliloti [4] |

Advanced Toolkits for Specific Applications

Specialized modular toolkits have been developed for various microbial groups:

Bacterial Systems:

- EcoFlex MoClo Toolkit: 78 plasmids including constitutive promoters, T7 expression systems, RBS strength variants, synthetic terminators, protein purification tags, and fluorescent proteins for E. coli applications [3]

- CIDAR MoClo Parts Kit: 93 modular plasmids for rapid one-pot, multipart assembly, combinatorial design, and expression tuning in E. coli [3]

- OpenCIDAR MoClo Toolkit: Broad-host-range vectors compatible with the CIDAR MoClo standard, including combinatorial constructs for rapid characterization in new organisms [3]

Actinobacterial Systems:

- Modular vectors for actinobacteria: 12 standardized vectors with three different resistance cassettes (apramycin, hygromycin, kanamycin) and four orthogonal integration systems (φBT1, φC31, VWB) [2]

Chloroplast Engineering:

- Chlamydomonas reinhardtii toolkit: >300 genetic parts for plastome manipulation, including 5'UTRs, 3'UTRs, intercistronic expression elements, and integration sites [5]

Application Notes: Implementing Broad-Host-Range Systems

Refactoring Specialized Metabolic Gene Clusters

Objective: Activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters from actinobacteria for the production of novel antimicrobial or anticancer agents [2].

Implementation Workflow:

Key Parameters:

- Vector Selection: Choose appropriate integration system (φBT1, φC31, or VWB) based on target host compatibility [2]

- Resistance Marker: Select marker (apramycin, hygromycin, or kanamycin) appropriate for the host and downstream applications [2]

- Assembly Method: Utilize compatible cloning method (BioBrick, Golden Gate, or ligase chain reaction) based on fragment characteristics [2]

Expected Outcomes: Production of unnatural specialized metabolites or activation of otherwise silent natural biosynthetic gene clusters, potentially yielding novel bioactive compounds with applications in human health [2].

High-Throughput Chloroplast Engineering

Objective: Rapid prototyping of plastid manipulations for improving photosynthetic efficiency or metabolic engineering in photosynthetic organisms [5].

Implementation Workflow:

Key Parameters:

- Regulatory Parts: Select from characterized 5'UTRs (35 options), 3'UTRs (36 options), promoters (59 options), and intercistronic expression elements (16 options) [5]

- Selection Markers: Utilize expanded markers beyond spectinomycin, including new resistance genes for chloroplast transformation [5]

- Reporter Systems: Implement fluorescence and luminescence-based reporters for high-throughput screening [5]

Expected Outcomes: Rapid development of synthetic promoter designs, improved photosynthetic efficiency, and establishment of metabolic pathways in plastids with potential for transfer to higher plants and crops [5].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Broad-Host-Range Synthetic Biology

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Compatible Host Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modular Cloning Toolkits | EcoFlex MoClo Toolkit (78 plasmids) [3] | Provides standardized parts for genetic circuit construction in bacteria | Primarily E. coli with broad-host-range extensions |

| CIDAR MoClo Parts Kit (93 plasmids) [3] | Enables rapid one-pot multipart assembly and combinatorial design | E. coli with broad-host-range variants | |

| Actinobacterial modular vectors (12 vectors) [2] | Facilitates DNA assembly and integration in actinobacterial chromosomes | Streptomyces species and other actinobacteria | |

| Broad-Host-Range Plasmids | pBBR1-based vectors [4] | Replicates in diverse Gram-negative bacteria | Alcaligenes eutrophus, Bordetella spp., Pseudomonas fluorescens [4] |

| IncP (RK2) vectors [4] | Maintains replication in wide Gram-negative range | Acinetobacter spp., Agrobacterium spp., Pseudomonas spp. [4] | |

| IncQ (RSF1010) vectors [4] | Functions in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria | Acinetobacter, Streptomyces, Mycobacterium species [4] | |

| Reporter Systems | Fluorescence proteins (GFP, RFP variants) | Quantitative measurement of gene expression and protein localization | Engineered versions available for diverse hosts |

| Luciferase enzymes | Highly sensitive detection of gene expression with dynamic range | Codon-optimized versions for different hosts | |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance cassettes (apramycin, hygromycin, kanamycin) [2] | Selective maintenance of genetic constructs in target hosts | Varies by resistance mechanism; some function across taxonomic groups |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Modular Assembly of Genetic Constructs Using MoClo System

Purpose: Assemble multiple DNA parts into functional plasmids for expression across diverse bacterial hosts.

Materials:

- MoClo-compatible Level 0, Level 1, and Level 2 vectors [3]

- Type IIS restriction enzymes (BsaI, BpiI/BbsI) and corresponding buffers [3]

- T4 DNA ligase and buffer

- DNA parts with appropriate fusion sites (promoters, UTRs, coding sequences, terminators) [3]

- Chemically competent E. coli cells for assembly

- LB medium with appropriate antibiotics

Procedure:

- Prepare Level 0 Modules (if not using pre-constructed parts):

- Amplify DNA parts (promoters, coding sequences, terminators) with primers adding appropriate fusion sites

- Clone into Level 0 vectors using Golden Gate assembly with BsaI

- Transform into E. coli, select on appropriate antibiotics, and verify by sequencing

Assemble Transcriptional Units (Level 1 Assembly):

- Combine compatible Level 0 parts (e.g., promoter, 5' UTR, coding sequence, terminator) with Level 1 destination vector

- Set up Golden Gate reaction:

- 50-100 ng of each Level 0 plasmid

- 100 ng Level 1 destination vector

- 1 μL BsaI-HFv2 restriction enzyme

- 1 μL T4 DNA ligase

- 1× T4 DNA ligase buffer

- Nuclease-free water to 20 μL

- Run thermocycler program:

- 37°C for 5 minutes (enzyme digestion)

- 16°C for 10 minutes (ligation)

- Repeat cycles 25 times

- 50°C for 5 minutes

- 80°C for 10 minutes (enzyme inactivation)

Assemble Multiple Transcriptional Units (Level 2 Assembly):

- Combine up to six Level 1 plasmids with Level 2 destination vector

- Use BpiI enzyme with similar reaction conditions as Step 2

- Transform into E. coli and verify assembly by colony PCR and restriction digestion

Transfer to Target Host:

- Isolate verified Level 2 plasmid

- Introduce into target bacterial host via conjugation, electroporation, or chemical transformation based on host compatibility

- Select with appropriate antibiotics and verify construct stability

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low assembly efficiency: Optimize DNA concentration ratios and increase number of thermocycler cycles

- Incorrect assemblies: Verify fusion site compatibility and part orientation

- Failed transformation into target host: Check plasmid preparation quality and host transformation efficiency

Protocol 2: Intergeneric Conjugation for Actinobacterial Hosts

Purpose: Transfer broad-host-range vectors from E. coli to actinobacterial hosts for chromosomal integration.

Materials:

- Donor E. coli strain (e.g., ET12567 containing the vector of interest)

- Recipient Streptomyces or other actinobacterial strain

- LB medium with appropriate antibiotics for donor selection

- Actinobacterial-specific growth media (e.g., TSB, SFM)

- Antibiotics for selection in actinobacteria

- 0.22 μm filters or non-selective agar plates for conjugation

Procedure:

- Prepare Donor and Recipient Cells:

- Grow donor E. coli strain overnight in LB with appropriate antibiotics at 37°C

- Grow recipient actinobacterial strain for 24-48 hours until adequate sporulation or vegetative growth

Conjugation Setup:

- Harvest donor cells by centrifugation and wash twice with fresh medium to remove antibiotics

- Mix donor and recipient cells in appropriate ratio (typically 1:1 to 10:1 donor:recipient)

- Spread mixture on appropriate non-selective agar plates

- Incubate at 28-30°C for 16-24 hours

Selection of Exconjugants:

- After conjugation, overlay plates with appropriate antibiotics for selection in actinobacteria

- Include counter-selection antibiotics to inhibit donor E. coli growth (e.g., nalidixic acid)

- Incubate plates at optimal temperature for actinobacterial growth until exconjugants appear (typically 3-7 days)

Verify Integration:

- Screen exconjugants for correct integration using PCR with primers specific to integration sites and inserted DNA

- Verify homoplasmy for integrated constructs by repeated passage without selection

- Confirm expression of integrated genes via RT-PCR or reporter assays

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low conjugation efficiency: Optimize donor:recipient ratio and ensure donor cells are adequately washed

- Contamination with donor E. coli: Adjust counter-selection antibiotic concentration

- No exconjugants: Verify compatibility of integration system with target host [2]

Broad-host-range synthetic biology represents a paradigm shift in genetic engineering, moving beyond the constraints of model organisms to harness the full diversity of microbial capabilities. The core principles of host flexibility, standardization, orthogonality, and resource efficiency provide a framework for designing biological systems that function predictably across diverse organisms. The continued development of modular genetic tools, standardized parts, and high-throughput characterization methods will further expand the applications of this approach in biotechnology, medicine, and environmental sustainability. As the field advances, treating microbial chassis as tunable design components rather than passive platforms will unlock new possibilities for engineering biological systems with enhanced capabilities and broader applications.

The Limitations of Traditional Chassis and the Untapped Potential of Microbial Diversity

Synthetic biology has historically relied on a narrow set of well-characterized model organisms, primarily Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, as platforms for genetic engineering. This preference has been driven by their well-understood genetics, rapid growth rates, and the availability of sophisticated engineering toolkits. While these "workhorse" organisms have proven invaluable for foundational proofs of concept, they represent a limited subset of microbial diversity and may not constitute the optimal chassis for many applied biotechnological goals. This bias toward traditional organisms can be viewed as a design constraint that has left the vast chassis-design space largely unexplored [6].

The inherent limitations of this approach have become increasingly apparent. Model organisms often lack the specialized metabolic capabilities, stress tolerance, or biosynthetic pathways required for advanced applications in biomanufacturing, environmental remediation, and therapeutics. Furthermore, the expression of complex eukaryotic genes or the synthesis of certain natural products can be challenging or inefficient in bacteria like E. coli due to differences in post-translational modifications, codon usage, or metabolic network architecture [6] [7]. The reliance on a limited number of chassis organisms thus constrains the functional versatility and real-world applicability of engineered biological systems.

The Broad-Host-Range Solution: Reconceptualizing the Chassis

Broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology has emerged as a modern subdiscipline that seeks to overcome these limitations by expanding the repertoire of host organisms used in bioengineering. A core principle of BHR synthetic biology is the reconceptualization of the chassis as an integral design variable rather than a passive, default platform. This paradigm shift encourages the rational selection of a host based on its innate biological traits and how these align with the specific application goals [6].

The Chassis as a Functional and Tuning Module

Within the BHR framework, the microbial host can be leveraged in two primary ways: as a functional module or as a tuning module.

As a Functional Module: The innate physiological and metabolic traits of a non-model organism form the foundation of the engineering concept. This approach "hijacks" nature's solutions, retrofitting pre-evolved phenotypes into artificial designs, which is often more efficient than engineering these complex traits from scratch in a model organism [6]. Examples include:

- Using phototrophs (e.g., cyanobacteria, microalgae) for biosynthetic production from carbon dioxide and sunlight [6] [5].

- Leveraging extremophiles (thermophiles, psychrophiles, halophiles) as robust chassis for biosensors or bioremediation in harsh environments [6].

- Employing organisms like Halomonas bluephagenesis for its high-salinity tolerance and natural product accumulation [6].

As a Tuning Module: Here, the function of a genetic circuit is independent of host phenotype, but its performance specifications (e.g., response time, signal strength, growth burden) are influenced by the host's unique cellular environment. Systematic comparisons have shown that host selection can significantly influence these key parameters, providing a spectrum of performance profiles for synthetic biologists to leverage [6].

The "Chassis Effect": A Challenge and an Opportunity

A significant challenge in BHR synthetic biology is the "chassis effect"—the phenomenon where the same genetic construct exhibits different behaviors depending on the host organism. This context dependency arises from host-construct interactions, such as competition for finite cellular resources (e.g., RNA polymerase, ribosomes, nucleotides) and regulatory crosstalk [6].

While the chassis effect can complicate predictive design, it also represents an untapped opportunity. By systematically understanding and characterizing how different host backgrounds influence genetic device performance, the chassis effect can be transformed from a source of unpredictability into a powerful tuning parameter for optimizing system behavior [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Traditional and Non-Traditional Chassis

The table below summarizes key characteristics of traditional and emerging non-traditional chassis, highlighting their distinct advantages and application potentials.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional and Non-Traditional Microbial Chassis

| Chassis Organism | Category | Key Native Traits / Advantages | Exemplary Applications | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli [6] | Traditional Model | Rapid growth, high genetic tractability, extensive toolkit | Foundational genetic circuit testing, protein production | Limited biosynthetic capacity for complex metabolites, poor stress tolerance |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae [7] | Traditional Model | Eukaryotic protein processing, GRAS status* | Protein expression, metabolic engineering for simple plant compounds | Metabolic burden with complex pathways, slower growth than bacteria |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii [5] | Photosynthetic Chassis | Single chloroplast, rapid growth, high-throughput cultivation | Chloroplast synthetic biology, metabolic prototyping for crops | Limited genetic tools, low transgene expression rates (historically) |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris [6] | Metabolically Versatile Chassis | Four modes of metabolism, growth-robust | Biomanufacturing from diverse feedstocks | Less developed genetic system |

| Halomonas bluephagenesis [6] | Halophilic Chassis | High-salinity tolerance, natural product accumulation | Industrial-scale fermentation under non-sterile conditions | Specialized growth requirements |

| Methanotrophs [8] | C1-Utilizing Chassis | Utilizes methane as carbon source | Biotransformation of methane into value-added products | Challenges in gas transfer, genetic tool development |

*GRAS: Generally Recognized As Safe

Experimental Protocols for BHR Synthetic Biology

Advancing BHR synthetic biology requires robust and reproducible methodologies for working with diverse, non-model microbes. The following protocols outline a generalized workflow.

Protocol: A High-Throughput Workflow for Prototyping in Non-Model Chassis

This protocol, adapted from chloroplast engineering efforts in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, provides an automated pipeline for generating and analyzing thousands of transplastomic strains in parallel, a approach that can be modified for other microbial systems [5].

I. Workflow Overview

II. Materials and Reagents

- Modular Genetic Parts Library: A collection of standardized, orthogonal genetic elements (promoters, RBS, terminators, origins of replication) compatible with BHR principles, often assembled in a Modular Cloning (MoClo) framework [6] [5].

- Automated Liquid Handling System: A robotic platform for contactless, high-throughput reagent and culture transfer.

- Rotor Screening Robot: An automated system for colony picking and restreaking on solid media.

- Selection Agents: Antibiotics or other compounds appropriate for the target chassis (e.g., beyond spectinomycin for C. reinhardtii) [5].

- Reporter Genes: A suite of genes for fluorescence (e.g., GFP), luminescence, or other selectable markers for high-throughput screening.

III. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Design & Assembly: Assemble genetic constructs using standardized, modular parts (e.g., via Golden Gate assembly) tailored for the target host(s). The use of BHR parts, such as those from the Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA), is encouraged [6].

- Transformation & Picking: Introduce the assembled constructs into the non-model chassis via electroporation or conjugation. Use the Rotor robot to automatically pick transformants into a standardized 384-array format on solid medium.

- Selection & Homoplasy: Restreak transformants onto fresh selective media to achieve homoplasmy/homogeneity. Screening multiple (e.g., 16) replicate colonies per construct in parallel on plates enhances efficiency and reduces losses.

- High-Throughput Analysis: Organize homoplasmic colonies into a 96-array format. Use the automated liquid handler to transfer biomass to multi-well plates for cell number normalization (OD750 measurement), medium transfer, and reporter gene analysis (e.g., by adding luciferase substrate).

- Data-Driven Learning: Collect and analyze performance data (e.g., growth, expression strength, product yield). Use this data to inform the next DBTL cycle, refining both the genetic construct and chassis selection.

Protocol: Assessing the Chassis Effect on a Genetic Device

This protocol describes a systematic approach to quantify the influence of different host backgrounds on the performance of an identical genetic circuit.

I. Workflow Overview

II. Materials and Reagents

- Standardized Genetic Device: A well-characterized circuit, such as an inducible toggle switch or oscillator, cloned into a BHR vector backbone.

- Panel of Microbial Chassis: A diverse set of 3-5 microbial hosts with varying phylogeny and physiology.

- Controlled Bioreactors or Multi-well Plates: For maintaining consistent growth conditions across all hosts.

- Flow Cytometer / Plate Reader: For quantifying fluorescence output and measuring optical density (growth) at high temporal resolution.

III. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Standardized Circuit Delivery: Transform the identical, standardized genetic construct into each chassis organism using optimized protocols for each host.

- Controlled Cultivation: Grow all transformed strains in biological triplicate under defined and consistent conditions (temperature, medium, aeration).

- Multi-Parameter Measurement: For each strain, measure key performance parameters over the growth curve:

- Device Output: Fluorescence/Luminescence intensity.

- Response Time: Time to reach half-maximal output after induction.

- Leakiness: Basal expression level in the non-induced state.

- Growth Burden: Impact of circuit operation on host growth rate.

- Signal Stability: Variation in output over time.

- Performance Profiling: Analyze the collected data to create a performance profile for each host-chassis combination. This reveals how host context tunes device properties and identifies the optimal chassis for a desired application profile (e.g., high output vs. fast response).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and tools that are fundamental to conducting BHR synthetic biology research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Broad-Host-Range Synthetic Biology

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example / Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Vector Systems | Standardized, interchangeable plasmid backbones with BHR origins of replication. | Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA) facilitates part exchange and host range prediction [6]. |

| Host-Agnostic Genetic Parts | Promoters, RBS, and terminators validated to function across multiple taxonomic groups. | Enables more predictable deployment of genetic devices in new chassis without extensive re-engineering [6]. |

| Compact Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance genes or auxotrophic markers with small footprints for easier delivery. | Expanding beyond spectinomycin (aadA) is critical for engineering chassis like C. reinhardtii [5]. |

| Advanced Reporter Genes | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, YFP) and luciferases for high-throughput screening and sorting. | Essential for quantifying gene expression and circuit performance in automated workflows [5]. |

| Automated Strain Handling | Robotic systems for colony picking, restreaking, and liquid culture management. | Enables parallel management of thousands of microbial strains, making non-model chassis screening feasible [5]. |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The integration of data-driven approaches and artificial intelligence is poised to further accelerate BHR synthetic biology. Machine learning models can analyze multi-omics datasets from diverse microbes to predict host-construct interactions, identify optimal chassis for specific pathways, and guide the design of host-agnostic genetic parts [9]. This represents a move towards a more predictive and rational framework for chassis selection and engineering.

In conclusion, moving beyond the traditional confines of model organism-centric synthetic biology is not merely an expansion of choice but a fundamental rethinking of design principles. By systematically tapping into the vast potential of microbial diversity and treating the chassis as an active, tunable component, researchers can unlock new capabilities in biotechnology. The development and adoption of standardized BHR tools and high-throughput protocols, as outlined in this article, are critical steps toward realizing the full potential of this expanded design space for applications ranging from sustainable manufacturing to precision medicine.

The paradigm in synthetic biology is shifting from treating the host organism as a passive vessel to engineering it as a predictable, programmable functional module within broader biological systems. This reconceptualization is foundational to the development of true broad-host-range synthetic biology, which requires standardized, portable genetic circuits that function reliably across diverse biological chassis. By applying principles of modular vector design—encompassing computational prediction, standardized parts, and adaptive control—we can transform the host into an active participant in synthetic circuit function. This approach mitigates context-dependent effects and enhances the portability and robustness of biological designs, accelerating applications from therapeutic development to sustainable bioproduction. These Application Notes provide the experimental and conceptual toolkit for implementing this paradigm, detailing protocols for host engineering, characterization, and integration into closed-loop functional systems.

Traditional synthetic biology often struggles with unpredictable and inefficient system performance due to the "black box" nature of the host organism. Its complex, dynamic internal environment—including metabolic burden, resource competition, and native regulatory networks—interferes with the function of introduced genetic circuits. The modular vector design framework addresses this by explicitly defining the host's role and interactions. In this model, the host is no longer a passive platform but an Active Functional Module characterized by:

- Standardized Interfaces: Well-characterized genomic safe havens and docking platforms for genetic material.

- Predictable Resource Allocation: Engineered metabolism to minimize burden and crosstalk.

- Sensing and Actuation Capacity: Embedded pathways for perceiving environmental states and executing programmed responses.

- Communicability: The ability to exchange information and materials with other modules in a consortium.

This document outlines the protocols and analytical frameworks for creating and validating such engineered hosts, with a focus on the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model chassis, while providing principles applicable to prokaryotic and other eukaryotic systems.

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Application Note 1: Engineering a Tunable Host Chassis with Reduced Context Dependency

Objective: To mitigate host-circuit interference by creating a chassis with decoupled resource allocation and standardized genomic landing pads.

Background: A major bottleneck in circuit portability is context dependency, where identical genetic constructs behave differently in various hosts or even different genomic locations within the same host. This protocol uses CRISPR-based integration to create a uniform genomic context and introduces a synthetic transcriptional regulator to buffer cellular resources.

Protocol 1.1: Creating Standardized Genomic Safe Havens via CRISPR-Cas9

- Principle: Identify and engineer genomic "safe havens"—transcriptionally active loci with minimal impact on host fitness—to serve as reliable, predictable sites for circuit integration.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Design gRNA Sequences: Using bioinformatics tools (e.g., CHOPCHOP), design two gRNAs that flank a ~1-2 kb region within a pre-validated safe haven locus (e.g., ROX1 or YKU80 in yeast). The gRNAs should be specific to the target locus with minimal off-target sites.

- Prepare the Donor DNA: Synthesize a linear donor DNA fragment containing:

- Homology arms (500-800 bp) matching the sequences upstream and downstream of the gRNA cut sites.

- A "landing pad" sequence between the homology arms, consisting of an attB/attP recombination site, a counter-selectable marker (e.g., URA3), and a fluorophore (e.g., mCherry) under a constitutive promoter.

- Co-transformation: Co-transform the host strain with:

- A plasmid expressing a high-fidelity Cas9 nuclease (e.g., SpCas9-HF1).

- Plasmids expressing the two gRNAs.

- The linear donor DNA fragment.

- Selection and Validation: Plate on media lacking uracil to select for successful integration. Screen colonies via PCR and fluorescence microscopy to confirm precise replacement of the target locus with the landing pad. Sequence the junction sites to verify correctness.

Protocol 1.2: Implementing a Resource Buffer Module

- Principle: Overexpress a synthetic, orthogonal RNA polymerase (e.g., T7 RNAP) to create a dedicated transcription pool for synthetic circuits, reducing competition with host genes.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Vector Construction: Clone a codon-optimized T7 RNAP gene under a tunable promoter (e.g., a tetracycline-responsive promoter, pTet) into an episomal plasmid with a high-copy origin of replication.

- Integration: Transform the plasmid into the engineered host from Protocol 1.1.

- Titration: Grow cultures with varying concentrations of the inducer (e.g., anhydrotetracycline, aTc). Measure host growth rate (OD600) and expression of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) driven by a T7 promoter to map the relationship between resource allocation and circuit output.

Application Note 2: Establishing Inter-Module Communication in a Synthetic Consortium

Objective: To program a multi-strain microbial community where engineered hosts act as coordinated modules, exchanging metabolites to perform a complex function.

Background: Synthetic consortia allow for a division of labor, reducing metabolic burden on individual cells and enabling more complex operations. This protocol recreates a syntrophic system where two auxotrophic yeast strains sustain each other by cross-feeding essential amino acids [10].

Protocol 2.1: Engineering Syntrophic Auxotrophic Pairs

- Principle: Generate two strains, each unable to synthesize a different essential amino acid but engineered to overproduce the amino acid required by its partner.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Strain Engineering:

- Strain A (ADE8-, LYS2+): In a wild-type background, knockout the ADE8 gene (involved in adenine biosynthesis) using CRISPR-Cas9. Introduce a constitutive promoter upstream of the LYS2 gene (involved in lysine biosynthesis) to drive lysine overproduction.

- Strain B (LYS2-, ADE8+): Knockout the LYS2 gene and engineer for overproduction of adenine by modifying the ADE8 gene to remove feedback inhibition.

- Validation of Monocultures: Confirm that each strain fails to grow in minimal medium lacking its essential amino acid (adenine for A, lysine for B) but grows in complete medium.

- Strain Engineering:

Protocol 2.2: Co-culture Dynamics and Analysis

- Principle: Monitor the growth and stability of the co-culture over time, demonstrating emergent community-level behavior.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Inoculation: Inoculate minimal medium with Strain A and Strain B at different initial ratios (e.g., 1:9, 1:1, 9:1). Use flow cytometry to distinguish strains if tagged with different fluorophores.

- Monitoring: Sample the co-culture every 2 hours for 24-48 hours.

- Measure total biomass by OD600.

- Use flow cytometry or plate counting on selective media to determine the population ratio of each strain.

- Quantify extracellular adenine and lysine concentrations via HPLC.

- Data Analysis: Model the growth dynamics to infer cooperation and competition parameters.

Application Note 3: Integrating CRISPR-AI for Adaptive Host Control

Objective: To implement a closed-loop system where an AI model interprets host-state sensors and actuates CRISPR-based interventions to maintain a desired functional output.

Background: Combining CRISPR for precise molecular manipulation with AI for data integration enables real-time, adaptive control of the host module. This is particularly relevant for managing pathological processes like glioblastoma [11].

Protocol 3.1: Developing a Digital Twin for Predictive Control

- Principle: Create a computational model that simulates host (or tumor) behavior under various perturbations.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Data Collection: From in vitro experiments, collect high-dimensional data: single-cell RNA-seq, proteomics, and metabolic flux measurements under different CRISPR knockout/activation conditions.

- Model Training: Use a machine learning framework (e.g., a recurrent neural network) to train a model that predicts future system states (e.g., tumor growth rate, expression of oncogenic pathways) based on current state and applied CRISPR perturbations.

- Validation: Test the model's predictive accuracy on a held-out dataset not used for training.

Protocol 3.2: Closed-Loop Actuation with CRISPRa/i

- Principle: Use the digital twin's predictions to select optimal CRISPR interventions, which are then physically implemented in the host system.

- Detailed Methodology:

- State Sensing: In a glioblastoma model cell line, engineer reporters for key oncogenic pathways (e.g., a GFP reporter under a RAS pathway-responsive promoter).

- Actuation: Pre-program a library of CRISPR activation/interference (CRISPRa/i) constructs targeting nodes in the RAS/MAPK, PI3K, and other relevant pathways.

- The Loop:

- Measure reporter signals (state sensing).

- Input the data into the digital twin.

- The model recommends the optimal CRISPRa/i construct(s) to shift the cells away from a proliferative state.

- Transduce the cells with the recommended AAV-delivered CRISPR construct.

- Repeat the cycle to achieve and maintain the desired therapeutic state.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Syntrophic Consortium Stability

This table summarizes key metrics from Protocol 2.2, demonstrating the functional success of the engineered community.

| Initial Inoculum Ratio (A:B) | Final Population Ratio (A:B) | Total Biomass Yield (OD600) | Extracellular Lysine (μM) | Extracellular Adenine (μM) | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:9 | 1:3.5 | 1.2 | 15.2 | 8.7 | System converges to a stable equilibrium |

| 1:1 | 1:1.2 | 2.1 | 25.5 | 22.1 | Balanced cooperation, highest yield |

| 9:1 | 5:1 | 0.9 | 5.1 | 18.5 | Imbalanced, lower total yield |

Table 2: Statistical Comparison of Host Performance Using T-Test

Following Protocol 1.2, a t-test is used to rigorously determine if the engineered resource buffer module significantly alters host performance compared to a wild-type control [12].

| Parameter | Wild-Type Host (Mean ± SD, n=5) | Engineered Host (Mean ± SD, n=5) | t-Statistic | P-value (Two-tail) | Significant (α=0.05)? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Growth Rate (h⁻¹) | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 1.34 | 0.22 | No |

| Circuit Output (GFP AU) | 1050 ± 150 | 4500 ± 400 | -19.8 | 1.2 x 10⁻⁷ | Yes |

| Plasmid Retention (%) | 92 ± 3 | 88 ± 5 | 1.67 | 0.13 | No |

- Hypothesis: H₀: Mean circuit output is the same between groups; H₁: Means are different.

- Conclusion: The significant p-value (< 0.05) and high t-statistic allow rejection of the null hypothesis, confirming that the resource buffer module significantly enhances synthetic circuit output without critically compromising host growth or plasmid stability [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Modular Host Engineering

| Item Name & Source | Function in Protocol | Key Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Nuclease (e.g., Thermo Fisher) | Protocol 1.1: CRISPR-mediated integration | Reduces off-target editing; crucial for maintaining host genomic integrity. |

| Linear Donor DNA Fragment (Integrated DNA Technologies) | Protocol 1.1: CRISPR-mediated integration | Contains homology arms and landing pad; should be HPLC-purified for high transformation efficiency. |

| pTet-T7 RNAP Plasmid (Addgene) | Protocol 1.2: Resource buffering | Provides a tunable, orthogonal transcription system for decoupled circuit expression. |

| Adenine & Lysine Auxotrophic Yeast Strains (e.g., EUROSCARF) | Protocol 2.1: Syntrophic consortium | Defined genetic backgrounds are essential for reproducible community engineering. |

| AAV-Delivered CRISPRa/i Library (VectorBuilder) | Protocol 3.2: Adaptive control | Enables efficient and multiplexed gene activation/repression in eukaryotic hosts. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

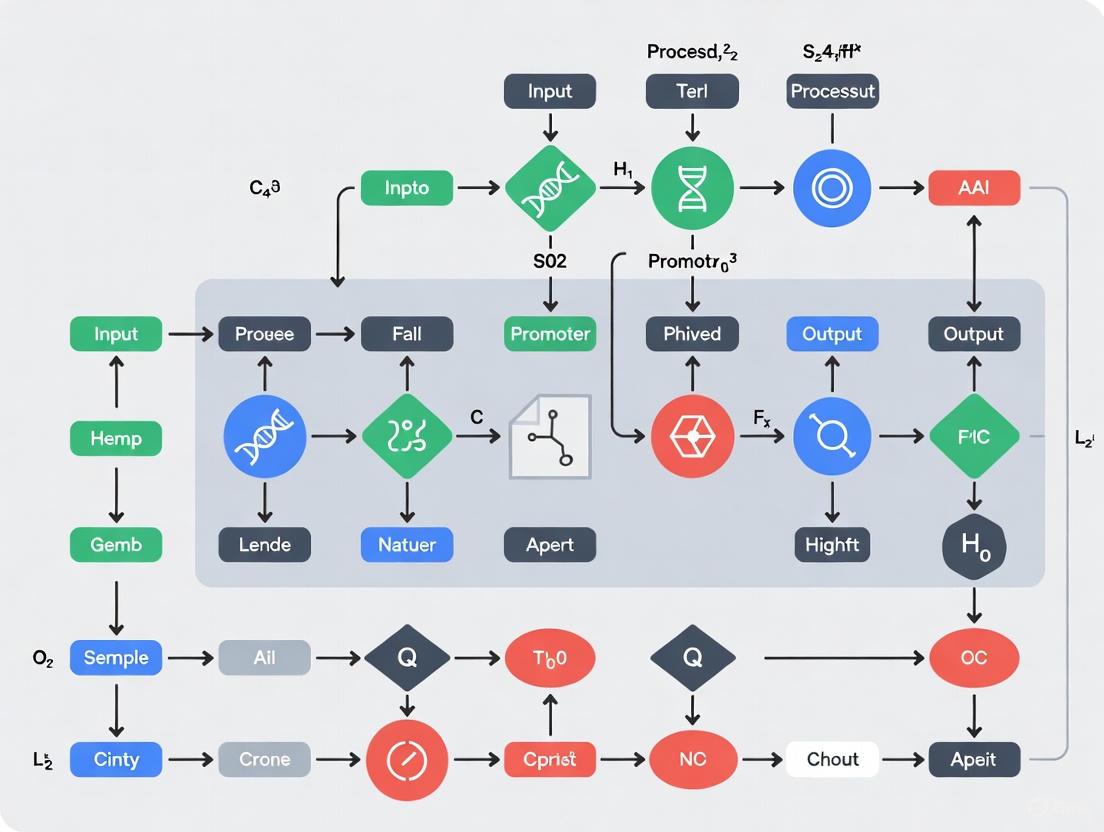

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows described in these Application Notes.

Dot Script 1: Modular Host Engineering Cycle

Dot Script 2: Synthetic Consortium Metabolic Pathway

Dot Script 3: CRISPR-AI Closed-Loop Control System

The field of synthetic biology relies on the precise design and predictable function of genetic circuits across diverse microbial hosts. A significant challenge in this endeavor is the "chassis-effect," where identical genetic circuits perform differently depending on the host organism's unique cellular environment [13]. To address this, broad-host-range (BHR) vector platforms have been developed, enabling genetic engineering across a wide spectrum of bacteria beyond common model organisms like Escherichia coli. The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA) stands as a key historical achievement in this domain, providing a standardized, modular framework for vector design [14]. This article details the SEVA platform, explores modern toolkits that build upon its principles, and provides detailed protocols for their application in synthetic biology and drug development research.

The SEVA Platform: A Historical Cornerstone

The SEVA platform was established to counter the proliferation of non-standard, incompatible plasmid vectors. Its primary innovation was a modular architecture where each plasmid is divided into standardized, interchangeable parts or "modules," facilitating easier engineering and predictability.

Core Modular Design

SEVA vectors are characterized by a tripartite structure [14]:

- Origin of Replication (ORI) Module: Controls plasmid copy number and host range.

- Antibiotic Resistance Marker (ABR) Module: Allows for selection in various hosts.

- Cargo Module: Houses the genetic circuit or gene of interest.

This design is encapsulated by a standardized syntax (e.g., SEVA23g19[g1]), where "23" denotes the ORI, "g19" the ABR, and "[g1]" the cargo location [14].

Key SEVA Vector Components and Examples

Table 1: Key Modules in the SEVA Platform

| Module Type | Specific Examples | Function and Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Origin of Replication (ORI) | p15A, pBBR1, RK2, R6K | Determines plasmid copy number and host range. BHR origins like pBBR1 and RK2 are crucial for function in diverse bacteria [2] [14]. |

| Antibiotic Resistance (ABR) | acc(3)IV (apramycin), aph (kanamycin), aph(7″) (hygromycin), tetA (tetracycline) | Provides selection in both E. coli and the target host. The tetA marker can also be used for negative selection with NiCl₂ [2] [15]. |

| Cargo/Expression Cassette | RhaS/RhaBAD, LacI/Trc, AraC/AraBAD, XylS/Pm | Contains the regulatory elements and gene(s) of interest. Allows for inducible or constitutive expression [14]. |

| Integration System | φBT1, φC31, VWB, TG1 | Enables stable site-specific integration into the host chromosome, which is particularly valuable in actinobacteria like Streptomyces [2]. |

Modern Expansions and Alternative Platforms

The modular principle of SEVA has inspired the development of next-generation toolkits and methodologies that address specific engineering challenges.

The Golden Standard Modular Cloning (GS MoClo)

The GS MoClo system builds directly upon SEVA, using Golden Gate assembly with Type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI, BbsI) to seamlessly assemble genetic parts [14]. It allows for the construction of complex multi-gene circuits from a library of standardized parts. A recent study used GS MoClo to create a set of plasmids with four different inducible systems (RhaBAD, Trc, AraBAD, Pm) for autonomous multi-protein expression in E. coli [14].

Advanced Toolkits for Non-Model Organisms

Specialized toolkits have been developed for specific bacterial genera, overcoming barriers in non-model organisms.

- Stutzerimonas Toolkit: This BHR kit, based on a pBBR1 backbone, enables the introduction of genetic circuits, such as inducible genetic inverters, into various Stutzerimonas species. It allows for the study of chassis effects across closely related hosts [13].

- Actinobacterial Vectors: A set of 12 modular vectors was developed for Streptomyces and other actinobacteria. These incorporate multiple integration systems (φBT1, φC31, VWB), antibiotic resistances, and FLP recombination target (FRT) sites for marker recycling, facilitating the refactoring of silent biosynthetic gene clusters [2].

Innovative Cloning Methodologies

- In Vivo Plasmid Recombineering: A modern methodology bypasses in vitro cloning by using a triple-selection cassette (gfp-tetA-Δcat) in E. coli [15]. This system combines visual screening (loss of GFP), positive selection (reconstitution of chloramphenicol resistance), and negative selection (tetA-mediated sensitivity to NiCl₂) to ensure accurate plasmid modification via λ-Red recombineering, working reliably at any plasmid copy number [15].

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Gene Pathway Assembly using GS MoClo

This protocol describes the assembly of a three-gene expression plasmid for a synthetic photorespiration pathway [5] [14].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Backbone Vectors: pSEVA23g19[g1], [g2], [g3] (Kan⁺) [14].

- Expression Cassettes: pRhaBAD12, pTrc23, pAraBAD_34 (each containing a TF/promoter and fusion sites) [14].

- Genetic Parts: RBS, protein tag, and CDS for each enzyme, flanked by BD fusion sites [14].

- Enzymes: BsaI-HFv2, BbsI-HF, T4 DNA ligase.

- Host Strain: E. coli BL21 (DE3) for protein expression.

Procedure:

- Level 1 Assembly (Transcriptional Unit): For each gene, mix the respective expression cassette plasmid (e.g., pRhaBAD_12) with the corresponding RBS, tag, and CDS parts. Perform a Golden Gate reaction with BsaI and T4 ligase. Transform into E. coli and select for positive clones [14].

- Level 2 Assembly (Multi-Gene Plasmid): Mix the three validated Level 1 plasmids (e.g., from RhaBAD, Trc, and AraBAD systems) with the final destination backbone (e.g., pSEVA23g19). Perform a Golden Gate reaction with BbsI and T4 ligase. The orthogonal fusion sites (12, 23, 34) ensure correct, ordered assembly [14].

- Transformation and Verification: Transform the final assembly into the expression host. Verify the construct by colony PCR and Sanger sequencing.

- Induction and Testing: Induce gene expression with the respective inducers (rhamnose, IPTG, arabinose). Measure enzyme activity and pathway output, which has been shown to result in a threefold increase in biomass production in chloroplast-based pathways [5].

Protocol 2: Assessing Chassis Effect in Stutzerimonas

This protocol uses the Stutzerimonas toolkit to quantify how a genetic circuit's performance varies across different hosts [13].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Genetic Device: pS5 plasmid with a genetic inverter (PBAD and PTet promoters regulating AraC and TetR, with fluorescent reporters) in a pBBR1-KanR backbone [13].

- Host Strains: Six Stutzerimonas species (e.g., S. chloritidismutans, S. perfectomarina).

- Inducers: Anhydrotetracycline (aTc) and L-arabinose (Ara).

Procedure:

- Transformation: Introduce the pS5 inverter plasmid into the six Stutzerimonas hosts via electroporation.

- Growth Conditions: Grow triplicate cultures of each transformed host in a defined minimal medium with kanamycin selection.

- Circuit Toggling: At mid-exponential phase, induce the cultures with different combinations of aTc and Ara to toggle the inverter between its operational states.

- Quantitative Measurement: Use a microplate reader to measure the fluorescence output (e.g., GFP, mCherry) and optical density (OD600) over 24 hours.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the dynamic range and switching characteristics of the inverter for each host. Perform RNA-seq to link differential gene expression of the core genome to the observed performance variations [13].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow for designing and testing broad-host-range systems, from part assembly to chassis effect analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BHR Synthetic Biology

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Kits / Parts |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Cloning Kits | Provide pre-assembled, standardized genetic parts for rapid circuit construction. | EcoFlex Kit (bacteria), CIDAR MoClo (bacteria), Plant Parts Kits, GoldenBraid [16]. |

| Broad-Host-Range Origins | Enable plasmid replication and maintenance in a wide taxonomic range of bacteria. | pBBR1, RK2, RSF1010 origins [13]. |

| Site-Specific Integration Systems | Facilitate stable chromosomal integration in challenging hosts like actinobacteria. | φBT1, φC31, VWB, TG1 integrase and attP sites [2]. |

| Advanced Selection Markers | Enable selection and counter-selection for complex genetic manipulations. | tetA (tetracycline resistance/NiCl₂ sensitivity), truncated cat gene for recombineering [15]. |

| Standardized Genetic Parts | Libraries of characterized promoters, RBSs, and terminators for predictable expression. | Libraries of >140 regulatory parts (UTRs, promoters) for chloroplast engineering [5]. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems | Allow for precise, tunable control of gene expression. | RhaS/RhaBAD, LacI/Trc, AraC/AraBAD, XylS/Pm [14]. |

This application note provides a detailed framework for leveraging native traits of non-model hosts, specifically phototrophs and extremophiles, within a modular synthetic biology workflow. These organisms present a largely untapped reservoir of unique metabolic pathways and stress-resistance mechanisms highly valuable for biomanufacturing and drug development [17]. The protocols herein are designed for researchers aiming to move beyond traditional model systems and are structured around the principles of broad-host-range vector design, facilitating the exchange of standardized genetic parts across diverse microbial chassis [18]. We summarize key quantitative data on extremophile diversity and their bioactive compounds in structured tables and provide visualized workflows for the genetic engineering and functional screening of these promising organisms.

Table 1: Classification and Applications of Major Extremophile Types [19] [20]

| Extremophile Type | Defining Environment | Native Host Traits & Adaptations | Key Biotechnological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermophiles | High temperatures (>40°C) [19] | Thermostable proteins and enzymes; modified membrane lipids [20] | Thermostable polymerases for PCR (e.g., Taq polymerase); high-temperature industrial biocatalysis [20] |

| Psychrophiles | Freezing temperatures (< -17°C) [19] | Anti-freeze proteins (AFPs); cold-active enzymes [19] | Food processing (e.g., cold-active proteases, amylases); cryoprotection; low-temperature laundry detergents [19] |

| Halophiles | High salinity (>3.5% NaCl) [19] | "Salt-in" cytoplasm or compatible solute synthesis; bacteriorhodopsin [20] | Biosynthesis of osmolytes; carotenoid pigments (Bacterioruberin) for antioxidants; biofuel production [20] |

| Acidophiles | Low pH (<5) [19] | Reinforced cell membranes; proton pumps [20] | Bioleaching of ores; bioremediation of acidic mine drainage [20] |

| Radiotolerant | High radiation [19] | Efficient DNA repair mechanisms; protective pigments (e.g., melanin) [20] | Antioxidant development; radioprotective agents; DNA repair studies [20] |

Table 2: Examples of Bioactive Compounds and Industrial Applications from Extremophiles [20]

| Bioactive Compound / Enzyme | Source Organism | Extremophile Type | Application(s) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq Polymerase | Thermus aquaticus | Thermophile | PCR & molecular biology | FDA-approved; Commercial |

| L-Asparaginase | Bacillus subtilis CH11 | Halotolerant | Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia; food processing | FDA-approved; Commercial |

| Halocins | Various Halophiles | Halophile | Novel antimicrobial peptides targeting resistant pathogens | Preclinical R&D |

| Bacterioruberin | Halobacterium salinarum | Halophile | Antioxidant; potential anticancer agent | Preclinical R&D |

| Antifreeze Proteins (AFPs) | Chlamydomonas nivalis [19] | Psychrophile | Cryopreservation; improving freeze-thaw stability in foods | R&D |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Modular Vector Assembly for a Non-Model Halophile Chassis

Objective: To assemble and test a broad-host-range vector for expressing a heterologous gene encoding the antioxidant pigment Bacterioruberin in a halophilic host.

Materials: Refer to Section 5, "The Scientist's Toolkit."

Methodology:

- Vector Design and Assembly:

- Select a broad-host-range origin of replication (e.g., derived from RSF1010) and a halophile-specific promoter (e.g., PmTAC from Halorubrum sp.) [17].

- Using Golden Gate or BioBrick assembly, clone the promoter, the crtB gene (phytoene synthase, a key enzyme in Bacterioruberin synthesis), and a halophile-compatible terminator into the modular vector backbone [18].

- Verify the final plasmid construct (pMOD-Halo-Bacter) by diagnostic restriction digest and Sanger sequencing.

Transformation and Selection:

- Cultivate the halophile host (e.g., Halobacterium salinarum) in a high-salt medium (e.g., 20-25% w/v NaCl) at 37°C to mid-log phase.

- Prepare electrocompetent cells by washing the culture in an ice-cold low-salt osmotically stabilized buffer.

- Transform 100 µL of competent cells with 100-500 ng of pMOD-Halo-Bacter plasmid via electroporation (e.g., 1.25 kV, 200 Ω, 25 µF).

- Allow recovery in 1 mL of rich medium for 6-8 hours at 37°C with shaking.

- Plate cells onto solid high-salt medium containing the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., mevinolin) and incubate for 7-14 days at 37°C.

Functional Phenotypic Screening:

- Inoculate positive transformants into liquid selective medium and cultivate for 96 hours.

- Monitor pigment production by measuring the culture's absorbance at 490 nm and 500 nm, characteristic of Bacterioruberin.

- Extract pigments from cell pellets using acetone-methanol (7:3 v/v) and analyze via HPLC-MS to confirm the identity of Bacterioruberin.

- Assess antioxidant activity of the cell extract using a standard DPPH radical scavenging assay.

Protocol: Functional Screening for Novel Extremozymes from Metagenomic Libraries

Objective: To identify novel extremozymes (e.g., proteases, lipases) from a consortia of extremophiles via activity-based screening of a metagenomic library.

Materials: Refer to Section 5, "The Scientist's Toolkit."

Methodology:

- Metagenomic DNA Extraction and Library Construction:

- Collect biomass from the extreme environment (e.g., hydrothermal sediment, saline lake).

- Extract total environmental DNA using a specialized kit for complex samples, ensuring high molecular weight.

- Fragment the DNA and clone large inserts (>40 kb) into a fosmid or BAC vector suitable for expression in a model host like E. coli.

- Package and transfer the library into the host to create a metagenomic expression library.

High-Throughput Activity Screening:

- Plate the library clones onto LB agar containing the appropriate antibiotic and the enzyme substrate.

- For Proteases: Incorporate 1% (w/v) skim milk. Positive clones will show a clear halo of casein hydrolysis against an opaque background.

- For Lipases: Incorporate 1% (v/v) tributyrin. Positive clones will show a clear zone around the colony.

- Incubate plates at the desired temperature (e.g., 4°C for psychrophiles, 60°C for thermophiles) for 24-48 hours.

- Pick positive clones and restreak for purification.

- Plate the library clones onto LB agar containing the appropriate antibiotic and the enzyme substrate.

Characterization of Putative Extremozymes:

- Isolate the fosmid/BAC from the positive clone and sequence it to identify the open reading frame responsible for the activity.

- Subclone the identified gene into a standard expression vector for overproduction.

- Purify the recombinant enzyme via affinity chromatography and characterize its biochemical properties, including optimal pH and temperature, tolerance to various solvents, and specific activity.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for engineering non-model hosts using modular synthetic biology. The process begins with host selection based on native traits and proceeds through genetic design, transformation, and functional validation to create a optimized production chassis. [17] [18]

Diagram 2: A generic genetic circuit for linking a native sensory module (e.g., light, pH, osmolarity) to the production of a target specialized metabolite in a phototroph or extremophile. [18]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Extremophile Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Broad-Host-Range Cloning Vectors | Plasmid backbones capable of replication in diverse bacterial hosts, essential for modular synthetic biology in non-model systems. | RSF1010 origin-based plasmids; IncP/P-1 group vectors. |

| Host-Specific Promoters | Genetic parts that drive gene expression in a specific extremophile chassis; can be constitutive or inducible. | PmTAC promoter for halophiles [17]; native C1-inducible promoters in methylotrophs [17]. |

| Specialized Growth Media | Culture media formulated to mimic the extreme conditions of the native habitat (pH, salinity, temperature). | High-salt medium for halophiles; low-pH medium for acidophiles; specific C1 substrates (methanol, formate) for methylotrophs [17]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Genome Editing Tools | For precise gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and multiplexed regulation in an expanding range of non-model hosts. | CRISPR-Cas9 systems adapted for Deinococcus radiodurans or cyanobacteria like Chroococcidiopsis [21]. |

| Metagenomic Library Kits | Tools for extracting, cloning, and expressing the collective genome of an extremophile microbial community in a surrogate host. | Fosmid or BAC vector kits for large-insert library construction from environmental DNA. |

| Activity-Based Assay Substrates | Chromogenic or fluorogenic compounds for high-throughput functional screening of enzyme activity from clones. | Skim milk (proteases); tributyrin (lipases); AZCL-linked polysaccharides (amylases, cellulases). |

Building the Toolbox: Modular Vector Design and Conjugation Protocols

The field of synthetic biology is undergoing a paradigm shift, moving beyond a narrow focus on traditional model organisms like Escherichia coli and embracing the vast potential of diverse microbial hosts. This approach, known as broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology, treats the microbial host not as a passive platform but as a crucial, tunable design parameter that significantly influences the performance of engineered genetic systems [6]. The successful implementation of BHR strategies is critically dependent on the availability of flexible genetic engineering tools. Modular vector architectures represent a foundational technology in this endeavor, providing the standardized frameworks necessary for the rapid design and assembly of plasmids capable of functioning across a wide phylogenetic range of bacteria [22] [6].

Platforms such as the Bacterial Expression Vector Archive (BEVA) have pioneered this modular approach. The recent introduction of BEVA2.0 has doubled the system's size, expanding its capacity to produce diverse replicating plasmids and making it amenable to advanced genome-manipulation techniques such as targeted deletions and integrations [22]. These systems rely on standardized biological parts—modules for replication, selection, and cargo—that can be effortlessly assembled using modern cloning techniques like Golden Gate assembly. This paper provides detailed application notes and protocols for leveraging these modular architectures, framed within a broader thesis on designing vectors for BHR synthetic biology research. The subsequent sections offer a quantitative comparison of standardized modules, detailed experimental methodologies for assembly and functional testing, and visualizations of the underlying logical workflows.

Standardized Module Classes and Quantitative Analysis

Modular vector systems are composed of interchangeable, standardized parts that govern key plasmid functions. The quantitative properties of these modules, such as copy number and antibiotic potency, are critical design parameters that directly impact the success of genetic engineering experiments in diverse hosts. The data presented below for the BEVA2.0 system provides a representative overview of available modules [22].

Table 1: Origins of Replication and Copy Number Classes

| Origin of Replication | Host Range | Copy Number (Copies/Cell) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| pBBR1 | Broad | Medium (10-30) | Stable maintenance in diverse Proteobacteria [22] |

| p15A | Narrow | Medium (15-20) | High stability in Enterobacteriaceae |

| ColE1 | Narrow | High (50-100+) | Very high copy number in E. coli |

| RSF1010 | Broad | Low (5-10) | Conjugative mobilization, Gram-negative range |

| pUC | Narrow | Very High (100-300) | Very high copy number in E. coli |

Table 2: Antibiotic Resistance Markers and Selection Conditions

| Resistance Gene | Antibiotic (Common Stock Conc.) | Working Concentration (µg/mL) | Mode of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kanamycin (KanR) | Kanamycin (50 mg/mL) | 25-50 | Protein synthesis inhibitor |

| Ampicillin (AmpR) | Ampicillin (100 mg/mL) | 50-100 | Cell wall synthesis inhibitor |

| Chloramphenicol (CmR) | Chloramphenicol (34 mg/mL in EtOH) | 25-35 | Protein synthesis inhibitor |

| Spectinomycin (SpcR) | Spectinomycin (50 mg/mL) | 50-100 | Protein synthesis inhibitor |

| Tetracycline (TetR) | Tetracycline (10 mg/mL in EtOH) | 10-20 | Protein synthesis inhibitor |

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Golden Gate Assembly of a Modular Broad-Host-Range Vector

This protocol describes the assembly of a functional plasmid from individual BEVA-compatible modules using Golden Gate assembly, which allows for the seamless, one-pot construction of a complete vector [22].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Restriction Enzyme & Ligase: T4 DNA Ligase and a Type IIS restriction enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HFv2 or Esp3I).

- 10x T4 Ligase Buffer: Provides ATP and DTT essential for ligation.

- Plasmid Modules: Purified plasmid DNA for each part (Origin, Resistance, Cargo) in a Golden Gate-compatible format, diluted to 50-100 ng/µL.

- Chemocompetent E. coli: A standard cloning strain such as DH5α or NEB 10-beta.

- LB Agar Plates: Containing the appropriate antibiotic for selection, as specified in Table 2.

Methodology

Reaction Setup: In a sterile 0.2 mL PCR tube, combine the following components on ice:

- 50-100 ng of each plasmid module (Backbone, Resistance, Origin, Cargo).

- 1.0 µL of Type IIS Restriction Enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HFv2, 10,000 U/mL).

- 0.5 µL of T4 DNA Ligase (400,000 U/mL).

- 2.0 µL of 10x T4 DNA Ligase Buffer.

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 µL.

Assembly Cycling: Place the reaction tube in a thermal cycler and run the following program:

- Cycle 1: 25 cycles of (37°C for 2 minutes + 16°C for 5 minutes).

- Cycle 2: 50°C for 5 minutes (final digestion).

- Cycle 3: 80°C for 10 minutes (enzyme heat inactivation).

- Hold: 4°C ∞.

Transformation:

- Thaw 50 µL of chemocompetent E. coli cells on ice.

- Add 5-10 µL of the assembly reaction to the competent cells and incubate on ice for 20-30 minutes.

- Heat-shock at 42°C for 30 seconds, then return to ice for 2 minutes.

- Add 250 µL of pre-warmed SOC or LB medium and recover at 37°C with shaking for 60 minutes.

- Plate the entire volume onto an LB agar plate containing the appropriate antibiotic and incubate overnight at 37°C.

Verification: Pick 3-5 colonies and inoculate into liquid culture with antibiotic. Isolate plasmid DNA and verify correct assembly by analytical restriction digest and/or Sanger sequencing across the assembly junctions.

Diagram 1: A workflow for Golden Gate assembly of modular vectors.

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Assembled Vectors in Non-Model Hosts

Validating the functionality of a modular vector across different hosts is essential for confirming BHR capability. This protocol assesses replication, selection, and cargo maintenance.

Research Reagent Solutions

- Electrocompetent Cells: Prepared for both the E. coli donor strain and the target non-model host (e.g., Pseudomonas putida, Rhodopseudomonas palustris).

- Electroporation Media: 1 mM HEPES or 10% glycerol for washing cells.

- SOC Recovery Medium.

- Selective Agar Plates: As per Table 2, formulated for the target host's specific nutritional requirements.

- Plasmid Isolation Kit: Suitable for the non-model host (e.g., kit with Gram-positive lysis protocols if applicable).

Methodology

Transformation into Non-Model Host:

- Thaw electrocompetent cells of the target non-model host on ice.

- Mix 50-100 ng of the assembled plasmid with 50 µL of cells in a pre-chilled electroporation cuvette (1-2 mm gap).

- Apply a single electrical pulse using host-specific parameters (e.g., 1.8 kV for Pseudomonas).

- Immediately add 1 mL of pre-warmed SOC or rich medium and recover with shaking for 2-4 hours at the host's optimal growth temperature.

Selection and Growth Analysis:

- Plate the recovery culture on selective agar and incubate until colonies appear.

- Pick a single colony to inoculate liquid selective medium.

- Measure the optical density (OD₆₀₀) every 2-4 hours over 24-48 hours to generate a growth curve. Compare to a negative control (wild-type strain without plasmid) to assess any growth burden.

Plasmid Stability Test:

- Inoculate a colony from the selective plate into liquid medium without antibiotic and grow for ~8-10 generations.

- Plate dilutions of this culture onto non-selective agar to obtain single colonies.

- Replica-plate or patch at least 50-100 of these colonies onto both selective and non-selective plates.

- Calculate the plasmid retention rate as: (Number of colonies on selective / Number on non-selective) × 100%.

Cargo Function Verification:

- Isolate plasmid from the non-model host and retransform it into E. coli to confirm its integrity.

- If the cargo is a reporter gene (e.g., GFP), measure fluorescence. If it is a biosynthetic pathway, use HPLC or GC-MS to quantify the end product.

Diagram 2: A workflow for functional validation of modular vectors in non-model hosts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of the protocols relies on a core set of research reagents and materials. The following table details these essential components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Modular Vector Assembly and Testing

| Category | Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes & Buffers | BsaI-HFv2 / Esp3I | Type IIS restriction enzyme for Golden Gate assembly; cuts outside recognition site [22]. |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Joins DNA fragments with compatible overhangs created by Type IIS enzymes. | |

| 10x T4 DNA Ligase Buffer | Provides co-factors (ATP, DTT) and optimal salt conditions for simultaneous restriction and ligation. | |

| Molecular Biology Kits | High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | PCR amplification of modules with minimal error rate. |

| Plasmid Miniprep Kit | Isolation of high-quality plasmid DNA from E. coli and non-model hosts. | |

| Gel Extraction Kit | Purification of DNA fragments from agarose gels. | |

| Strains & Media | Chemocompetent E. coli (e.g., DH5α) | General cloning and plasmid propagation host. |

| Electrocompetent Non-Model Hosts | Strains like P. putida, R. palustris for BHR functional testing [6]. | |

| LB & Selective Media Broth/Agar | Standard microbial growth and selection. | |

| Specialized Materials | Electroporation Cuvettes (1-2 mm) | For introducing DNA into non-model bacterial hosts via electroporation. |

| SOC Outgrowth Medium | Recovery medium for cells post-transformation to ensure cell viability and plasmid expression. |

Modular cloning frameworks, primarily Golden Gate Assembly and its standardized implementation Modular Cloning (MoClo), represent transformative advancements in synthetic biology that enable precise, efficient, and reproducible assembly of complex genetic constructs. These systems utilize Type IIS restriction enzymes that cleave DNA outside their recognition sequences, generating defined overhangs that facilitate the ordered, seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction [23]. The Phytobrick standard extends this concept by establishing a unified syntax for genetic parts, allowing them to be freely shared and recombined between laboratories and systems [5]. For plastid and chloroplast engineering, these standardized approaches address significant technical challenges including limited available genetic tools, low throughput in plant-based systems, and the need for sophisticated multi-gene pathway engineering [5]. The implementation of these frameworks has dramatically accelerated the prototyping of genetic designs for plastid engineering, enabling systematic characterization of regulatory elements and assembly of complex metabolic pathways that were previously impractical with conventional cloning methods.

Technical Foundations of Golden Gate and MoClo Assembly

Core Principles and Mechanism

Golden Gate Assembly operates on the fundamental principle of using Type IIS restriction enzymes in conjunction with DNA ligase in a single-reaction mixture. Unlike traditional Type IIP restriction enzymes that cut within their recognition sites, Type IIS enzymes such as BsaI and BsmBI recognize asymmetric DNA sequences and cleave at a defined distance outside these sequences [23]. This unique property enables the generation of user-defined 4-base overhangs that serve as the assembly instructions for the reaction. The overhang sequences are not determined by the enzyme itself, allowing for the creation of scarless fusions between DNA fragments [23]. During the reaction, cyclical digestion and ligation occur simultaneously, with correctly assembled products losing the restriction sites and thus being protected from further cleavage. This directional assembly allows for the ordered construction of complex genetic circuits from basic standardized parts [24].

The MoClo system builds upon Golden Gate Assembly by establishing a hierarchical framework with clearly defined assembly levels. This framework employs standardized fusion sites (overhangs) for each level and part type, ensuring universal compatibility [25]. The system uses different Type IIS enzymes at different levels to prevent cross-reactivity, with BpiI typically used for Level 0 assembly, and BsaI for Level 1 and beyond [24]. The hierarchical nature of MoClo enables the creation of extensive part libraries that can be readily shared between laboratories, significantly accelerating synthetic biology workflows in plastids and other biological systems [5].

Key Enzymes and Reagents

The efficiency of Golden Gate and MoClo assemblies depends critically on the performance of specialized enzymes and master mixes. Key enzymes include BsaI-HFv2 and BsmBI-v2, which have been specifically optimized for Golden Gate reactions [26]. These enzymes exhibit reduced star activity and improved efficiency in one-pot reactions. T4 DNA ligase is typically employed for its robust activity in connecting DNA fragments with the designed overhangs. To simplify reaction setup, NEBridge Golden Gate Assembly kits provide pre-optimized mixes of restriction enzymes and ligase, while the NEBridge Ligase Master Mix offers a convenient 3X master mix designed for use with various Type IIS enzymes [26].

For specialized applications requiring scarless assembly, SapI represents an alternative Type IIS enzyme that generates 3-nucleotide overhangs, enabling precise fusion at start and stop codon boundaries without additional amino acid linkages [27]. More recently, PaqCI, a Type IIS enzyme with a 7-basepair recognition sequence, has expanded the toolkit, providing greater specificity for complex assemblies [26]. The selection of appropriate enzymes depends on multiple factors including incubation temperature preferences, sequence specificity requirements, and compatibility with existing part libraries.

Figure 1: Golden Gate Assembly Mechanism. Type IIS restriction enzymes bind to recognition sites but cleave DNA at downstream sites, generating specific 4-base overhangs. T4 DNA ligase then joins compatible overhangs, creating seamless assemblies without restriction sites in the final product.

Standardized Syntax and Phytobrick Framework

MoClo Hierarchical Assembly Levels

The MoClo system employs a precise hierarchical structure that enables the stepwise construction of increasingly complex genetic constructs. Each level utilizes specific fusion sites (overhangs) that follow community-established standards to ensure interoperability [25]. Level 0 constitutes the most basic building blocks, consisting of individual genetic elements such as promoters, 5'UTRs, coding sequences, and terminators. These basic parts are domesticated into standard vectors with defined prefix and suffix overhangs, typically ACAT and TTGT, creating a reusable collection of characterized genetic elements [25]. At Level 1, these basic parts are assembled into complete transcriptional units using standardized overhangs including GGAG, TACT, CCAT, AATG, AGGT, TTCG, GCTT, GGTA, and CGCT [25]. This level enables the creation of functional gene expression cassettes with precisely arranged regulatory elements. Level 2 facilitates the combination of multiple transcriptional units into complex multigene constructs using another set of standardized overhangs such as TGCC, GCAA, ACTA, TTAC, CAGA, TGTG, GAGC, and GGGA [25]. This hierarchical approach allows researchers to build complex genetic circuits from standardized, reusable parts while maintaining flexibility and efficiency throughout the assembly process.

Expanded Overhang Standards and Fidelity Considerations