MS vs NMR in Isotopic Labeling: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comparative analysis of Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for isotopic labeling studies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

MS vs NMR in Isotopic Labeling: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for isotopic labeling studies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, methodological applications across metabolomics, proteomics, and structural biology, and offers practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimization. By synthesizing current methodologies and validation strategies, this guide aims to empower scientists in selecting the appropriate technique for their specific research objectives, from pathway discovery to drug metabolism studies.

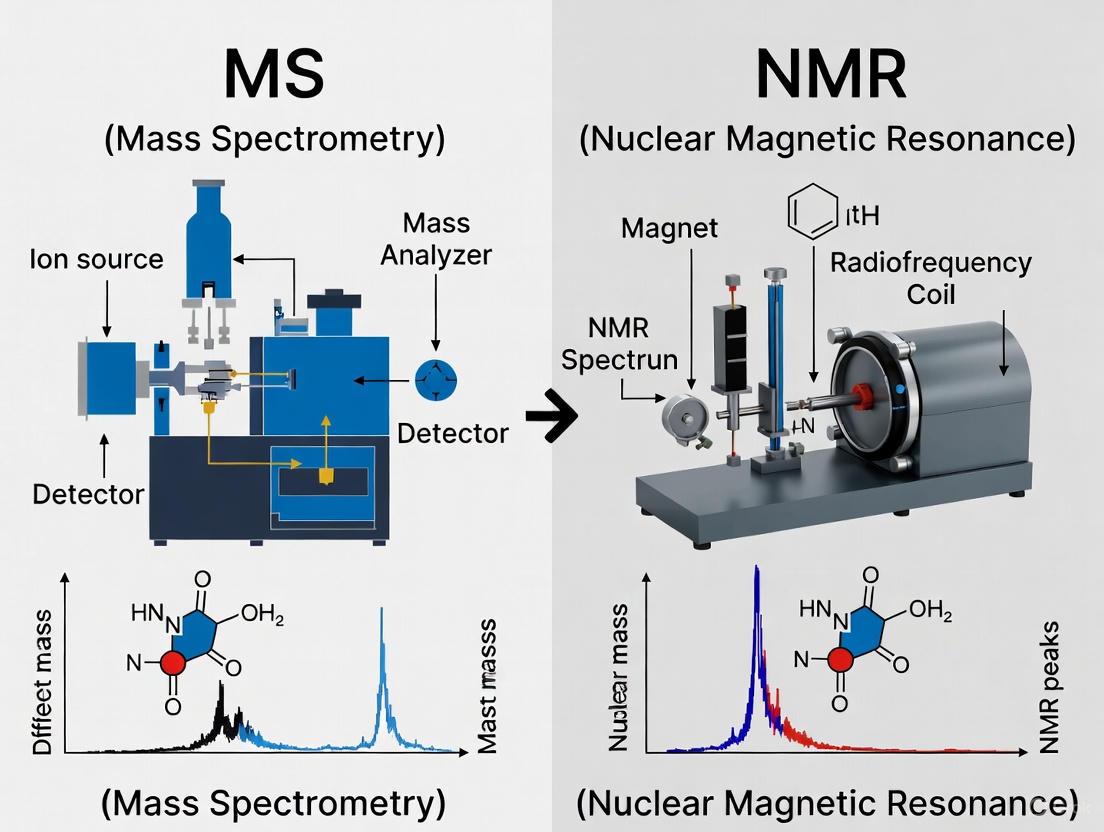

Discovering Core Principles: How MS and NMR Detect Isotopic Labels

In the fields of metabolomics, natural products research, and drug development, accurately measuring the molecular composition of complex biological samples is a fundamental challenge. Two analytical techniques stand as pillars for this task: Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. While both provide invaluable data, their underlying detection mechanisms are fundamentally different. MS separates and identifies ions based on their mass-to-charge ratios (m/z), whereas NMR detects the magnetic properties of specific atomic nuclei, such as ¹H or ¹³C, within a molecule. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two techniques, with a particular focus on their performance in isotopic labeling studies, supported by current experimental data and protocols.

Core Principles and Comparative Strengths

The distinct physical principles behind MS and NMR directly result in complementary strengths and weaknesses.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) relies on the ionization of molecules to generate gas-phase ions, which are then separated by their m/z ratio in an electric or magnetic field. The detection of these ions provides information on molecular mass and, through fragmentation patterns, structural clues.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei. When placed in a strong magnetic field, nuclei with a non-zero spin (like ¹H or ¹³C) can absorb and re-emit radiofrequency energy. The frequency of this resonance is exquisitely sensitive to the local chemical environment, providing direct information on molecular structure, dynamics, and atomic connectivity.

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of both techniques.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of MS and NMR Techniques

| Feature | Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions [1] | Magnetic properties of atomic nuclei (e.g., ¹H, ¹³C) [2] |

| Sensitivity | High (detection of low-abundance metabolites) [3] [4] | Lower, but steadily improving with cryoprobes & high-field magnets [2] [4] |

| Quantification | Requires calibration curves & internal standards; can be semi-quantitative | Inherently quantitative; signal intensity is directly proportional to nucleus count [2] [4] |

| Structural Elucidation | Provides molecular mass & fragment patterns; limited for isomers [4] | Unmatched for determining unknown structures & identifying isomers [2] [4] |

| Isotope Analysis | Quantifies isotopic labeling distributions [2] | Identifies specific atomic positions of isotope labels (e.g., ¹³C, ¹⁵N) [2] [5] |

| Sample Preparation | Often requires separation (LC/GC) and/or derivatization [3] | Minimal preparation; can be non-destructive and applied in vivo [2] [3] |

| Reproducibility | Can vary with ionization efficiency and matrix effects | Highly reproducible and quantitative over a wide dynamic range [2] |

| Key Strength | High sensitivity and throughput | Robust quantification and unambiguous structural analysis |

Quantitative Performance in Isotopic Analysis

Isotopic labeling is a cornerstone technique for tracing metabolic pathways and fluxes. Here, the complementary nature of MS and NMR is particularly evident.

NMR for High-Precision Isotopic Analysis

Quantitative NMR (qNMR) is increasingly recognized for its high precision in isotopic ratio measurement. Advanced software tools like rnmrfit 2.0 have been developed specifically for this purpose. This tool uses semi-global peak fitting with automated peak region selection to achieve high precision, demonstrating performance superior to common commercial NMR analysis software [6].

Table 2: Isotopic Precision Achievable with NMR Spectroscopy

| Isotope | Achievable Precision | Key Technique / Software |

|---|---|---|

| ²H (Deuterium) | 0.26% | rnmrfit 2.0 software for peak fitting [6] |

| ¹³C (Carbon-13) | 0.16% | rnmrfit 2.0 software for peak fitting [6] |

A critical advantage of NMR in isotope analysis is its ability to determine the specific position of a label within a molecule. For example, in a ¹³C-labeled glucose molecule, NMR can distinguish which carbon atom carries the label, providing direct insight into the metabolic pathway that produced it. MS, in contrast, typically quantifies the overall isotopic enrichment but cannot pinpoint the exact atomic position without additional, often indirect, experiments [2].

Experimental Protocol: NMR-Based Isotopic Quantification

The following is a generalized protocol for high-precision isotopic analysis using NMR, based on methodologies described in the literature [6] [7]:

- Sample Preparation: The analyte is dissolved in a deuterated solvent. An internal quantitative standard (e.g., maleic acid) of known concentration is added for absolute quantification [7].

- Data Acquisition: ¹H or ¹³C NMR spectra are acquired on a spectrometer (e.g., Bruker Avance III HD) with a cryoprobe for enhanced sensitivity. Critical acquisition parameters must be optimized:

- Pulse Sequence: A quantitative pulse sequence (e.g., zg) with a flip angle of 90° is used.

- Relaxation Delay (d1): Set to > 10 times the longitudinal relaxation time (T₁) of the slowest-relaxing nucleus of interest to ensure complete relaxation between scans for accurate integration [7].

- Number of Scans (NS): Adjusted to achieve sufficient signal-to-noise ratio (e.g., > 150:1).

- Spectral Processing: The Free Induction Decay (FID) is processed with careful attention to:

- Data Analysis with rnmrfit 2.0:

- Load the processed spectrum into the software.

- Define the spectral regions of interest for the analyte and internal standard.

- Execute the semi-global fitting algorithm, which models the experimental spectrum as a sum of individual peak shapes (e.g., Lorentzian lines).

- The software outputs the integrated area for each peak, which is used to calculate the concentration and isotopic enrichment with high precision [6].

NMR Isotopic Analysis Workflow

Synergistic Applications: Combining MS and NMR

Rather than viewing MS and NMR as competitors, the most powerful approach is to use them synergistically. The combination of both techniques greatly improves the confidence and depth of compound identification in complex mixtures [2] [4].

- MS-Driven Discovery to NMR Validation: A common workflow uses the high throughput and sensitivity of MS to identify potential biomarkers or interesting metabolites in a complex mixture. Subsequently, NMR is employed for the unambiguous structural elucidation of these shortlisted compounds, distinguishing between isomers and confirming atomic connectivity [4].

- Integrated Data Analysis: Advanced methods now exist to simultaneously analyze data from both MS and NMR. One approach filters data from one technique against the other to increase the number of compounds confidently identified. Another method identifies compounds by exploiting the principle that abundance/intensity ratios are relatively constant for the same metabolite in different samples analyzed by both techniques [2].

- Comprehensive Isotope Tracing: In metabolic flux analysis, MS generally quantifies the overall distribution of isotopic labeling, while NMR provides the specific labeling positions within a molecule. Using both techniques offers a complete picture of metabolic pathway dynamics [2].

Complementary MS-NMR Relationship

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of MS and NMR methodologies, especially in isotopic labeling studies, relies on key reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Isotopic Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Precursors (e.g., ¹³C-glucose, ¹⁵N-ammonia) | To trace metabolic pathways and measure flux. | Used in both MS and NMR experiments to introduce a detectable label into metabolic systems [2] [5]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O, CD₃OD) | Provides a lock signal for the NMR spectrometer and minimizes interfering solvent signals. | Essential for high-resolution NMR spectroscopy [7]. |

| Internal Quantitative Standards (e.g., TSP, maleic acid) | A reference compound of known purity and concentration for absolute quantification in qNMR. | Added directly to the NMR sample; its signal is used as a calibrant [7] [8]. |

| Methyltransferases (e.g., Msp, 2Bst) | Enzymes for site-specific installation of ¹³C-methyl labels on DNA or RNA. | Enables NMR studies of large nucleic acids and their complexes via the methyl TROSY effect [5]. |

| Cryoprobes and Microprobes | NMR probe technology that increases sensitivity by reducing thermal noise or optimizing sample volume. | Critical for detecting low-abundance metabolites and analyzing mass-limited samples [2] [4]. |

| rnmrfit 2.0 Software | An open-source tool for high-precision fitting of NMR peaks for isotopic ratio measurement. | Used for quantitative analysis of ¹³C and ²H NMR spectra, offering superior precision over commercial software [6]. |

Both Mass Spectrometry and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy are indispensable tools in the modern scientist's toolkit. The choice between them is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is more appropriate for the specific research question at hand, and more often, how they can be best used together.

MS is the preferred tool for high-throughput screening, detecting low-abundance metabolites, and rapidly determining molecular formulas. NMR is unmatched for unambiguous structural elucidation, distinguishing isomers, performing absolute quantification without specific standards, and identifying the precise positions of isotope labels within a molecule. For advanced isotopic analysis in metabolic flux studies or authenticity testing, NMR, particularly with tools like rnmrfit 2.0, provides a level of precision and positional information that is complementary to the high sensitivity of MS. By leveraging the synergistic power of both mass-based and magnetic property-based detection, researchers can achieve a more complete and robust understanding of complex biological systems.

Natural Abundance and its Impact on Experimental Design

The natural abundance of stable isotopes is a fundamental physical property that profoundly shapes the design and execution of experiments in chemical and pharmaceutical research. For nuclei critical to molecular structure elucidation, such as carbon-13 (∼1.1%) and nitrogen-15 (∼0.05%), their low natural occurrence renders them nearly invisible to routine nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) detection [9]. This limitation is a pivotal factor driving the need for isotopic labeling, a process that introduces enriched isotopes into molecules to make them detectable by analytical techniques like NMR and Mass Spectrometry (MS). Within drug discovery, understanding the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) of compounds is paramount, and isotopic labeling provides the necessary tracers for these studies [10]. The choice between MS and NMR as the primary detection method directly influences the experimental design, from the selection of the isotope to the labeling strategy employed. This guide objectively compares the performance of MS and NMR in the context of isotopic labeling, providing researchers with a framework to select the optimal technique for their investigative goals.

The Fundamental Challenge: Low Natural Abundance of Key Isotopes

The natural abundance of an isotope dictates its baseline detectability. For 1H-NMR, the high (∼99.98%) natural abundance of protons enables the direct acquisition of spectra without enrichment. However, the narrow dispersion of proton chemical shifts leads to significant signal overlap in complex molecules, complicating analysis [9]. This is where the higher chemical shift dispersion of other nuclei, like carbon-13 and nitrogen-15, becomes invaluable. Unfortunately, their low natural abundance means that, in a uniformly unlabeled sample, the probability of a molecule containing even a single 13C or 15N atom at a specific position is exceedingly low. Consequently, the signals from these nuclei are too weak to be practically detected in NMR experiments, creating a fundamental barrier to studying molecular structure and dynamics [9]. This experimental void necessitates the artificial enrichment of these isotopes to raise their concentration to detectable levels, thereby enabling detailed spectroscopic analysis.

Comparative Analysis: MS vs. NMR as Detection Techniques for Isotopic Labels

The selection between Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a critical decision point in experimental design, as each technique has distinct strengths, requirements, and outputs based on the isotopic labels used. The table below provides a structured comparison of these two cornerstone technologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MS and NMR in Isotopic Labeling Analysis

| Feature | Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Detection Principle | Measures mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions [11]. | Detects nuclear spin transitions in a magnetic field [9]. |

| Impact of Natural Abundance | Can complicate spectra with complex isotopologue patterns, but high sensitivity allows detection of low-abundance species. | Low natural abundance of 13C/15N makes detection without enrichment impractical; enrichment is required for detailed study [9]. |

| Primary Isotopes Used | ²H (D), ¹³C, ¹⁵N, ¹⁸O [11]. | ¹³C, ¹⁵N, ²H (for dilution) [12] [9]. |

| Key Strength | High sensitivity; ideal for tracing and quantifying isotopes in complex mixtures (e.g., metabolic flux) [11]. | Provides atomic-resolution structural and dynamic information (e.g., protein-ligand interactions, conformation) [13] [9]. |

| Typical Application | Metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA), ADME studies, quantitative proteomics (SILAC) [11] [10]. | Protein structure determination, fragment-based drug discovery, mapping binding sites [13] [9]. |

| Sample Requirement | Low (picomole to femtomole levels). | High (nanomole to micromole levels). |

| Data Output | Quantification of isotopic incorporation and distribution. | Site-specific assignment of isotopic labels and reporting on local chemical environment. |

Isotopic Labeling Strategies to Overcome Natural Abundance Limitations

To leverage the power of MS and NMR, researchers employ sophisticated labeling strategies that move beyond simple uniform enrichment. These strategies are designed to simplify complex spectra, reduce costs, and provide specific information.

Table 2: Common Isotopic Labeling Strategies and Their Experimental Utility

| Labeling Strategy | Description | Primary Technique | Experimental Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Labeling | Incorporates an isotope (e.g., ¹³C or ¹⁵N) at all possible sites in the molecule [9]. | NMR | Foundation for multi-dimensional NMR experiments; enables comprehensive structural studies [12]. |

| Amino Acid-Specific Labeling | Incorporates isotopes into a single type of amino acid (e.g., [U-¹⁵N]-lysine) [9]. | NMR | Simplifies spectra by turning "on" signals only for selected residues; aids in assignment and analysis of large proteins [9]. |

| Reverse Labeling | Uses unlabeled amino acids or precursors in an otherwise uniformly labeled background, thereby "turning off" selected signals [9]. | NMR | Simplifies crowded regions of NMR spectra by removing signals from abundant residue types (e.g., aliphatic/aromatic in membrane proteins) [9]. |

| Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC) | Incorporates "heavy" ¹³C/¹⁵N-labeled amino acids into proteomes of cultured cells for comparative analysis [11]. | MS | Quantitative proteomics; accurately compares protein expression levels between different samples [11]. |

| Deuteration (²H) | Replaces ¹H with ²H in the protein backbone or sidechains [9]. | NMR | Reduces signal-broadening in large proteins, enabling TROSY-based studies of macromolecular complexes [9]. |

| Hydrogen Isotope Exchange (HIE) | Replaces hydrogen with deuterium (²H) or tritium (³H) via catalytic exchange, often in late-stage synthesis [10]. | MS / Scintillation | Creates labeled compounds for ADME studies; improves metabolic stability via the Kinetic Isotope Effect (deuterium) [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Labeling Workflows

The practical implementation of labeling strategies requires standardized protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for two foundational approaches: one for NMR and one for MS.

Protocol: Residue-Specific Reverse Labeling for NMR Spectroscopy

This protocol is used to simplify crowded regions in a 2D ¹H-¹⁵N HSQC spectrum of a uniformly labeled protein by making specific amino acid types NMR-invisible [9].

- Molecular Biology: Clone the gene of interest into an appropriate expression vector for Escherichia coli (E. coli).

- Media Preparation: Prepare a defined minimal medium using M9 salts. Use ¹⁵NH₄Cl as the sole nitrogen source to ensure uniform ¹⁵N labeling. Supplement this medium with a single, unlabeled (natural abundance) amino acid that you wish to "reverse label" (e.g., unlabeled lysine).

- Protein Expression: Transform the expression plasmid into an E. coli expression strain. Grow the culture in the prepared medium. Induce protein expression with Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at the optimal cell density (OD₆₀₀ ~0.6-0.8). Express the protein for several hours at a temperature conducive to solubility (e.g., 18-37°C).

- Protein Purification: Harvest cells by centrifugation. Lyse the cells using sonication or a French press. Purify the protein using affinity chromatography (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins), followed by size-exclusion chromatography if needed.

- NMR Data Acquisition: Concentrate the purified protein and prepare an NMR sample in an appropriate buffer. Acquire a 2D ¹H-¹⁵N HSQC spectrum. The cross-peaks corresponding to the reverse-labeled amino acid (e.g., lysine) will be absent or significantly diminished, simplifying spectral analysis.

Protocol: Metabolic Flux Analysis with ¹³C-Labeled Glucose

This protocol is a cornerstone of MS-based analysis for tracking carbon flow through metabolic pathways [11].

- Cell Culture and Labeling: Grow cells (e.g., E. coli, yeast, or mammalian cells) in a tightly controlled bioreactor. Once the culture reaches a steady state of growth, rapidly switch the carbon source from unlabeled glucose to an equivalent amount of uniformly labeled ¹³C-glucose.

- Sampling and Quenching: At precise time intervals after the switch, withdraw culture samples and immediately quench metabolism using cold methanol or similar rapid-quench methods to "freeze" the metabolic state.

- Metabolite Extraction: Extract intracellular metabolites from the quenched cell pellets using a solvent system like cold methanol/acetonitrile/water.

- MS Analysis and Isotopomer Modeling: Analyze the extracted metabolites using Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS) or Gas Chromatography-MS (GC-MS). The mass spectra will reveal the distribution of ¹³C atoms (isotopologues) in each metabolite. This data is then fed into computational models (e.g., using software like INCA or OpenFLUX) to calculate the metabolic flux rates through the network.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of the two primary experimental strategies discussed, highlighting the role of isotopic labeling and the divergence towards MS or NMR detection.

Diagram 1: MS vs NMR Experimental Design Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful isotopic labeling experiments depend on specific, high-quality reagents. The table below details key materials and their functions in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Isotopic Labeling Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Isotopologues |

|---|---|---|

| Labeled Amino Acids | Residue-specific labeling in proteins for NMR; essential for SILAC in MS-based proteomics [9] [11]. | [U-¹⁵N]-Lysine, [¹³C₆,¹⁵N₂]-Lysine (for SILAC) |

| ¹³C-Labeled Carbon Sources | Serves as the carbon backbone for microbial growth and uniform ¹³C protein labeling; used as a tracer for Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) in MS [9] [11]. | [U-¹³C]-Glucose, 1-¹³C-Glucose |

| ¹⁵N-Labeled Nitrogen Sources | Provides the nitrogen for uniform ¹⁵N labeling of proteins for NMR, enabling ¹H-¹⁵N correlation experiments [9]. | ¹⁵NH₄Cl |

| α-Ketoacid Precursors | Cost-effective metabolic precursors for selective side-chain (e.g., methyl group) labeling in proteins for NMR, especially in challenging expression systems [14]. | 2-[¹³C]-methyl acetolactate (for Val/Leu) |

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) | Deuterium source for producing deuterated proteins to suppress ¹H-¹H relaxation, crucial for NMR studies of large proteins [9]. | D₂O |

| HIE Catalysts | Facilitate late-stage, direct hydrogen-deuterium/tritium exchange on complex molecules, streamlining the creation of labeled compounds for ADME studies [10]. | Iridium, Ruthenium complexes |

Natural abundance is not merely a statistical footnote but a central factor that dictates the feasibility and design of experiments aimed at understanding molecular structure and function. The low natural abundance of isotopes like 13C and 15N creates a detection threshold that can only be overcome through deliberate isotopic enrichment. The choice between MS and NMR as the core analytical technique leads to divergent experimental pathways: MS excels in high-sensitivity tracing and quantification within complex mixtures, while NMR provides unparalleled atomic-resolution insight into structure and dynamics. By understanding the comparative strengths of these techniques and mastering the associated labeling strategies—from uniform enrichment to residue-specific reverse labeling and metabolic tracing—researchers can design robust experiments that turn the challenge of natural abundance into a powerful tool for scientific discovery and drug development.

Stable isotopic labels, including Carbon-13 (13C), Nitrogen-15 (15N), and Deuterium (2H), serve as powerful, non-radioactive tracers for investigating complex biological systems. These isotopes are incorporated into metabolites, drugs, and biomolecules to track their fate through metabolic pathways, study protein structure and dynamics, and quantify biochemical flux. The choice of isotope and detection technology—either Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy or Mass Spectrometry (MS)—is fundamental to experimental design, as each combination offers distinct advantages and limitations. NMR provides unparalleled structural detail and atom-by-atom tracking within molecules, while MS offers exceptional sensitivity for detecting low-abundance species. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these isotopic labels and detection techniques, empowering researchers to select the optimal approach for their specific applications in pharmaceutical and biochemical research.

Technical Principles and Comparison of Detection Techniques

Fundamental Principles of NMR and MS for Isotope Detection

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei. When placed in a strong magnetic field, nuclei with a non-zero spin, such as 1H, 13C, and 15N, absorb and re-emit electromagnetic radiation. The frequency of this radiation (the chemical shift) is exquisitely sensitive to the local chemical environment, providing detailed structural information. For isotopic labeling studies, NMR directly detects the labeled nuclei (e.g., 13C) or detects their influence on nearby sensitive nuclei (e.g., 1H). A key advantage of NMR is its ability to differentiate isotopomers—molecules that differ in the positional arrangement of isotopes—which is crucial for understanding metabolic pathways [15].

Mass Spectrometry (MS) separates ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). Introducing a stable isotope, such as 13C or 15N, increases the mass of a molecule or fragment, creating a distinct signal that can be resolved from the unlabeled species. MS is exceptionally sensitive and can detect very low concentrations of labeled compounds. However, it typically identifies isotopologues—molecules differing in their total isotopic composition—without directly revealing the specific atomic position of the label within the molecule [15].

Comparative Analysis: NMR vs. MS

The table below summarizes the core technical characteristics of NMR and MS in the context of stable isotope detection.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of NMR and MS for Isotopic Label Detection

| Feature | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Mass Spectrometry (MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Information Obtained | Identifies isotopomers (positional enrichment) [15]. Provides direct structural and stereochemical data. | Identifies isotopologues (total mass enrichment) [15]. Structural inference requires fragmentation (MS/MS). |

| Quantitation | Inherently quantitative; signal intensity is directly proportional to the number of nuclei [15] [16]. | Requires calibration curves for absolute quantitation; relative quantitation is robust [15]. |

| Sensitivity | Historically lower, requiring larger samples or enrichment. Enhanced by hyperpolarization [17] or cryoprobes [18]. | Extremely high sensitivity, capable of detecting metabolites in the nanomolar range or lower [16]. |

| Sample Throughput | Lower throughput; acquisition times can be minutes to hours. | High throughput; rapid analysis times (minutes) [15]. |

| Key Strength | Chemical specificity, atom-by-atom tracking, non-destructive. | Sensitivity, high molecular specificity when coupled with chromatography, suitability for high-throughput workflows. |

| Key Limitation | Lower sensitivity, requires larger sample amounts. | Cannot distinguish positional enrichment without additional experiments (e.g., fragmentation). |

In-Depth Analysis of Individual Isotopic Labels

Carbon-13 (13C) Labeling

13C is one of the most versatile labels due to its presence in all organic compounds. Its relatively low natural abundance (1.1%) makes it an excellent tracer.

- NMR Applications: 13C NMR benefits from a wide chemical shift range (~250 ppm), which minimizes signal overlap compared to 1H NMR [19]. Quantitative 13C NMR (13C qNMR) is used for pharmaceutical analysis, from small molecules to biopolymers [19]. A significant innovation is the use of hyperpolarized 13C, where techniques like dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) can enhance signal by >10,000-fold, enabling real-time tracking of metabolism in living systems [17]. For example, injecting hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate allows monitoring its conversion to lactate, alanine, and bicarbonate in cancer models [17].

- MS Applications: 13C labeling is widely used in fluxomics to track carbon flow through metabolic networks. An advanced application is Single-Cell MS (scMS), which tracks 13C incorporation into specialized metabolites, like alkaloids in plant cells, at single-cell resolution, revealing cell-to-cell heterogeneity in metabolic pathways [20].

- Indirect 1H NMR Detection: To overcome the inherent low sensitivity of direct 13C detection, a high-throughput method uses 1H NMR to indirectly measure 13C enrichment. When a 1H nucleus is attached to a 13C atom, the J-coupling constant changes. By comparing 1H spectra with and without 13C decoupling, researchers can quantify the 13C enrichment fraction, combining the sensitivity of 1H NMR with the tracing power of 13C [15].

Nitrogen-15 (15N) Labeling

15N is primarily used to study nitrogen-containing compounds, such as amino acids, nucleotides, and proteins.

- NMR Applications: 15N is essential for biomolecular NMR, especially for studying protein structure and dynamics. A key challenge is its low natural abundance (0.37%) and sensitivity, which are improved with high-field spectrometers and cryoprobes [18]. Optimal Control (OC) pulses have been developed for 15N at high magnetic fields (e.g., 1.2 GHz) to ensure efficient and uniform spin manipulation, enhancing the sensitivity of 13C-detected experiments for proteins, including intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) [21]. A powerful targeted profiling strategy involves chemically tagging metabolites containing carboxyl groups with a 15N-ethanolamine label. This allows for the detection of over 100 carboxyl-containing metabolites using sensitive 1H-15N 2D NMR experiments, greatly reducing spectral complexity [16].

- MS Applications: 15N-labeled compounds are easily distinguished by MS due to a mass shift. They are routinely used in quantitative proteomics (e.g., SILAC) and metabolomics. The 15N tag from ethanolamine also provides a predictable mass shift for tagged metabolites, facilitating their identification in complex mixtures by MS [16].

Deuterium (2H) Labeling

Deuterium (2H) has a nucleus that is NMR-active, but its low gyromagnetic ratio makes it less sensitive than 1H.

- NMR Applications: Deuterium Metabolic Imaging (DMI) is an emerging in vivo application where 2H-labeled substrates (e.g., 2H-glucose) are administered. The metabolism is then tracked using 2H Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging (MRSI) at high field strengths (e.g., 7 T). This technique maps the production of metabolites like lactate and glutamate in tissues. Due to low signal-to-noise, advanced low-rank denoising methods (e.g., SPIN-SVD, tMPPCA) are employed to enhance data quality, enabling mapping of metabolic fluxes in the brain and tumors [22].

- MS Applications: 2H labeling is very common in MS-based tracing due to the significant mass shift and lower cost compared to 13C. It is extensively used in drug metabolism studies (to track metabolites) and in kinetic studies. As demonstrated in single-cell MS, deuterated precursors (e.g., d5-tryptamine) can be fed to protoplasts to track the synthesis of deuterated alkaloids over time, elucidating biosynthetic pathways with cellular resolution [20].

Table 2: Summary of Isotopic Labels and Their Primary Applications

| Isotope | Natural Abundance | Primary NMR Applications | Primary MS Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C | 1.1% | Hyperpolarized metabolic imaging [17], qNMR for pharmaceuticals [19], structural analysis. | Metabolic flux analysis [20], isotopologue profiling. |

| 15N | 0.37% | Protein structure/dynamics [21], targeted metabolomics via chemical tagging [16]. | Quantitative proteomics (SILAC), identification of N-containing metabolites. |

| 2H | 0.011% | Deuterium Metabolic Imaging (DMI) for in vivo metabolism [22]. | Drug metabolism studies, kinetic profiling, biosynthetic pathway tracing [20]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Indirect Quantification of 13C Enrichment via 1H NMR

This protocol is designed for high-throughput quantification of 13C-labeled metabolites in cell lines and tissue extracts [15].

- Cell Culture and Labeling: Plate cells (e.g., 1 × 10^6 cells per well). Treat according to experimental design. Replace media with media containing either 5 mM natural abundance glucose or 5 mM [1,6-13C]glucose. Incubate for a set period (e.g., 3 hours).

- Metabolite Extraction: Remove media and store at -80°C. Wash cells with cold PBS. Add 2 mL of 80% cold methanol to the cells and incubate at -80°C overnight to extract water-soluble metabolites. Centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. Collect the supernatant and lyophilize.

- Sample Preparation for NMR: Reconstitute the lyophilized extract in 600 μL of buffer containing 10% D2O, 0.5 mM DSS (internal chemical shift and quantitation standard), and 10 mM imidazole (pH indicator). For media samples, first remove proteins using a 3 kDa centrifugal filter.

- 1H NMR Data Acquisition: Acquire 1D 1H NMR spectra with and without 13C decoupling during acquisition.

- Data Analysis: In the 1H spectrum without decoupling, signals from protons bound to 12C appear as singlets, while signals from protons bound to 13C are split into doublets (due to J-coupling). The 13C-decoupled spectrum collapses all signals to singlets. The fractional 13C enrichment for a specific metabolic pool is calculated by measuring the signal intensity loss of the 12C-bound proton singlet in the decoupled spectrum compared to the non-decoupled spectrum.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Indirect ¹³C Quantification via ¹H NMR.

Protocol 2: Targeted Metabolite Profiling Using 15N Tagging

This protocol uses a chemoselective 15N tag to profile carboxyl-containing metabolites with high sensitivity in complex biological samples like serum and urine [16].

- Derivatization Reaction: Mix the biological sample (e.g., serum or urine) with 15N-ethanolamine and the coupling reagent 4-(4,6-Dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMT-MM). Incubate to allow the conjugation of the 15N-tag to the carboxyl groups of metabolites.

- Sample Purification: After the reaction is complete, purify the mixture using a centrifugal filter device (e.g., Centriprep YM-10) to remove excess reagents and buffer exchange.

- 2D 1H-15N NMR Acquisition: Acquire a 2D 1H-15N heteronuclear correlation spectrum (e.g., HSQC or HMQC). The 15N tag creates a new, well-dispersed 1H-15N spin system for every tagged metabolite.

- Metabolite Identification and Quantification: Identify metabolites by matching the observed 1H and 15N chemical shifts to a database of known 15N-ethanolamine derivatives. The signal intensity in the 2D spectrum is directly proportional to metabolite concentration, enabling absolute quantification against an internal standard.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Targeted Profiling with ¹⁵N Tagging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Isotopic Labeling Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| [1,6-13C]Glucose | A common tracer for glycolytic and pentose phosphate pathway flux. | Tracing carbon fate in cell cultures and in vivo models [15]. |

| d5-Tryptamine | Deuterated precursor for alkaloid biosynthesis studies. | Elucidating the monoterpene indole alkaloid pathway in plants at single-cell resolution [20]. |

| 15N-Ethanolamine | Chemoselective tag for carboxyl-group containing metabolites. | Enabling sensitive detection and quantification of >100 carboxylic acids in biofluids via 2D NMR [16]. |

| DSS (4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid) | Internal reference standard for NMR chemical shift and quantitation. | Referencing and quantifying metabolites in 1H NMR experiments [15]. |

| DMT-MM Coupling Reagent | Activates carboxyl groups for amide bond formation with amines. | Facilitating the conjugation of 15N-ethanolamine to metabolites [16]. |

| Hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyruvate | A super-polarized metabolic probe for real-time in vivo spectroscopy. | Monitoring real-time metabolic fluxes to lactate, alanine, and bicarbonate in cancer imaging [17]. |

Comparative Performance Data and Applications

Case Study: Single-Cell Metabolic Tracing

A groundbreaking 2025 study directly compared the capabilities of MS and isotopic labeling at the single-cell level [20]. Researchers used d5-tryptamine and single-cell MS (scMS) to track the synthesis of monoterpene indole alkaloids in individual plant cell protoplasts. They successfully detected and temporally resolved the formation of deuterated intermediates like d4-strictosidine, d4-ajmalicine, and d4-catharanthine. This study highlights MS's superior sensitivity and spatial resolution, capable of detecting metabolites at estimated limits of quantification of 0.02–0.1 nM in single cells, thereby revealing cell-type-specific metabolic routing and transport that would be averaged out in bulk tissue analysis [20].

Case Study: In Vivo Metabolic Imaging

The development of hyperpolarized 13C technology showcases a unique strength of NMR. In preclinical models of prostate cancer, intravenous injection of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate enabled real-time monitoring of its conversion to lactate via 13C MRSI. This conversion, reflecting the upregulated glycolysis in cancer (the Warburg effect), was mapped with high spatial resolution (0.135 cm³) in 10 seconds. This application demonstrates NMR's unique capacity for non-invasive, dynamic monitoring of metabolic fluxes in living organisms, providing functional information that complements anatomical imaging [17].

Case Study: Food Authentication

A 2025 study in Food Chemistry provided a direct, ground-breaking comparison of a targeted isotopic method (MS-based) versus an untargeted chemical fingerprinting method (GC-MS-based) for authenticating virgin olive oil origin [23]. The MS-based method measured bulk δ13C, δ18O, and δ2H stable isotope ratios, achieving a 75% classification accuracy for Italian vs. non-Italian oils. In contrast, the untargeted sesquiterpene fingerprinting method significantly outperformed isotopic ratios, achieving over 90% accuracy and proving more sensitive to differences between closely located Italian regions [23]. This case illustrates how the choice of analytical method and data processing approach can dramatically impact the outcome of a study.

In the field of analytical chemistry, particularly in research involving isotopic labeling for metabolism, drug development, and systems biochemistry, two powerful techniques stand out: Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The data they produce—chromatograms from MS and resonance spectra from NMR—serve as fundamental windows into molecular identity, structure, and dynamics. For researchers investigating complex biological systems using stable isotope tracers, understanding the nature, strengths, and limitations of these data outputs is crucial for experimental design and data interpretation. This guide provides an objective comparison of these outputs, framed within the context of isotopic labeling measurement techniques.

Fundamental Data Outputs: A Direct Comparison

The core data outputs of MS and NMR are fundamentally different in nature and information content. The table below summarizes their key characteristics.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Chromatograms (MS) and Resonance Spectra (NMR)

| Feature | Chromatograms (MS) | Resonance Spectra (NMR) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Type | Ion abundance vs. retention time & mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) | Signal intensity vs. chemical shift (ppm) |

| Key Readouts | Retention time (Rt), m/z values, signal intensity | Chemical shift (δ), signal splitting (J-coupling), signal intensity |

| Information Provided | Molecular mass, fragment patterns, quantity | Molecular structure, atomic environment, dynamics, quantity |

| Isotope Detection | Distinguishes isotopologues (mass difference) | Identifies positional isotopomers (chemical shift) |

| Quantitation | Can require internal standards; linear range can be wide | inherently quantitative; signal area proportional to nucleus count [24] |

| Sensitivity | High (pico- to femtomolar) [25] [24] | Low (micromolar to millimolar) [25] [24] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in how a simple molecule, like labeled ethanol, is traced and identified through each technique's data output.

Performance Comparison in Isotopic Labeling Studies

The choice between MS and NMR often hinges on the specific requirements of the isotopic labeling experiment. The two techniques offer complementary performance profiles.

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Isotopic Labeling Measurement [25] [26] [24]

| Parameter | Mass Spectrometry (MS) | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High | Low |

| Reproducibility | Average | Very High |

| Number of Detectable Metabolites | 300 - 1000+ | 30 - 100 |

| Sample Preparation | Complex (extraction, derivatization) | Minimal |

| Isotope Detection Strength | Isotopologue detection and quantification (number of tracer atoms) | Positional Isotopomer identification (location of tracer atoms) |

| Throughput | Moderate to High (depends on chromatography) | Fast (single measurement, no separation) |

| Instrument Cost & Size | Lower cost, smaller footprint | More expensive, requires significant space |

A key application of both techniques is Stable Isotope-Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM), where a biological system is fed an isotopically enriched precursor (e.g., 13C-glucose), and its fate through metabolic pathways is tracked [26]. In this context:

- MS excels at providing high-sensitivity data on the number of labeled atoms in a pool of metabolites (isotopologue distribution) across hundreds of compounds.

- NMR is unparalleled in determining the exact position of the labeled atoms within the molecular structure (positional isotopomer) without the need for chemical degradation, offering a direct view into metabolic pathway fluxes [26] [27].

Experimental Protocols for Isotopic Labeling

MS-Based Protocol Using Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS)

This protocol is typical for tracking isotopic incorporation in metabolomics studies [26] [28].

- Cell/Tissue Treatment: Incubate cells (e.g., cancer cell lines) or tissue samples in a medium containing a stable isotope tracer (e.g., [U-13C]-glucose or [U-13C,15N]-glutamine) for a defined period.

- Metabolite Extraction: Quench metabolism rapidly (e.g., using liquid nitrogen). Extract metabolites using a solvent system like cold methanol/acetonitrile/water.

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge to remove protein debris. Dry the supernatant under a nitrogen stream and reconstitute in a solvent compatible with the LC mobile phase. Derivatization may be required for some metabolite classes (e.g., for GC-MS).

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Chromatographic Separation: Inject the sample onto a reverse-phase UHPLC column. Elute metabolites using a gradient of water and acetonitrile, often with modifiers like formic acid.

- Mass Spectrometry: The eluent is ionized (e.g., by Electrospray Ionization - ESI) and analyzed by a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF or Orbitrap).

- Data Processing: Use software to align chromatograms, pick peaks, and identify metabolites based on retention time and accurate mass. Isotopologue distributions are calculated from the integrated peak areas for each m/z signal corresponding to the unlabeled and labeled forms of the metabolite.

NMR-Based Protocol for Metabolic Flux Analysis

This protocol describes a common workflow for using NMR in SIRM studies [29] [26].

- Isotope Labeling and Extraction: Treat biological samples with a stable isotope tracer as in the MS protocol. Perform metabolite extraction similarly, often without the need for derivatization.

- Sample Preparation for NMR: Reconstitute the dried extract in a deuterated buffer (e.g., D2O with a phosphate buffer). Transfer the solution to a standard NMR tube.

- NMR Spectroscopy Acquisition:

- Place the sample in a high-field NMR spectrometer (e.g., a 600 MHz Bruker Avance Neo, as used in a recent MS metabolomics study [29]).

- Acquire a 1D 1H NMR spectrum using a standard pulse sequence with water suppression.

- For detailed isotopic analysis, acquire 2D experiments such as 1H-13C Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC) or Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation (HMBC). These experiments correlate proton and carbon chemical shifts, helping to assign the 13C label to specific atomic positions.

- Data Processing and Analysis: Process the Free Induction Decay (FID) by applying Fourier transformation, phase, and baseline correction. Metabolites are identified and quantified by comparing their chemical shifts to reference databases. The 13C labeling pattern is determined by analyzing the multiplet structures in 1H-13C HSQC spectra or the presence of 13C-13C J-couplings in 1D 1H NMR spectra.

The workflow below visualizes the parallel and complementary nature of these protocols in a SIRM study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Successful isotopic labeling studies rely on specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details essential items for such research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Isotopic Labeling Studies

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Precursors(e.g., [U-13C]-Glucose, [U-13C,15N]-Glutamine) | Core reagents for tracing metabolic fate. They are incorporated into downstream metabolites, allowing the mapping of biochemical pathways [26]. |

| Deuterated Solvents(e.g., D2O, CD3OD) | Essential for NMR spectroscopy to provide a lock signal for field frequency stabilization and to avoid overwhelming the solvent signal in 1H NMR [28]. |

| Metabolite Extraction Solvents(e.g., Methanol, Acetonitrile) | Used to rapidly quench metabolic activity and extract a broad range of polar and semi-polar metabolites from biological samples for both MS and NMR analysis [26] [28]. |

| LC-MS Grade Mobile Phase Additives(e.g., Formic Acid, Ammonium Acetate) | Enhance ionization efficiency in MS and help control chromatographic separation (e.g., by modulating pH) in reverse-phase LC, improving peak shape and detection [28]. |

| NMR Reference Standards(e.g., TMS, DSS) | Added to NMR samples to provide a known chemical shift reference point (0 ppm) for accurate metabolite identification and quantification [27]. |

| Chemical Shift and Metabolite Databases(e.g., HMDB, BMRB) | Computational tools containing reference 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts and MS fragmentation patterns of known metabolites, crucial for compound identification [29] [28]. |

Chromatograms from MS and resonance spectra from NMR provide distinct yet highly complementary data for researchers using isotopic labeling techniques. MS offers superior sensitivity and the ability to profile hundreds of metabolites, providing excellent data on the amount of isotopic incorporation. NMR, with its lower sensitivity, provides unparalleled structural detail and direct information on the position of isotopic labels within molecules, without the need for extensive sample preparation or separation. The most robust SIRM studies, therefore, often leverage both techniques in a cross-validating and synergistic manner [26] [28]. The choice between them—or the decision to use both—depends on the specific research question, the required depth of isotopic information, and the available resources.

Strategic Applications: Choosing Between MS and NMR for Your Research Goal

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) has long provided crucial insights into the dynamic functioning of biochemical networks by quantifying metabolite flow through pathways. However, traditional bulk MFA approaches mask critical cellular heterogeneity, a limitation particularly problematic in complex tissues and diseases like cancer where metabolic variation significantly impacts treatment outcomes [30] [31]. The emerging frontier of single-cell MFA represents a paradigm shift, enabling researchers to dissect metabolic heterogeneity and reveal previously obscured cellular behaviors. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the cutting-edge technologies redefining this field, focusing on their capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications for researchers and drug development professionals.

Each method approaches the fundamental challenge of single-cell flux quantification differently: some employ sophisticated instrumentation to physically measure isotope incorporation in individual cells, while others leverage computational power to infer fluxes from genomic data. The choice between these approaches involves careful trade-offs between experimental directness, pathway coverage, technical accessibility, and biological resolution [32] [33] [30]. As we explore these technologies, we will examine their performance characteristics, data requirements, and validation standards to provide a comprehensive framework for selecting appropriate tools based on specific research objectives.

Technological Approaches for Single-Cell Flux Analysis

Experimental Measurement Techniques

Spatial Single-Cell Isotope Tracing technologies physically measure isotope incorporation in individual cells. The 13C-SpaceM method exemplifies this approach by extending spatially resolved mass spectrometry to detect 13C6-glucose-derived carbons in esterified fatty acids at single-cell resolution [30]. This technology integrates matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) with all-ion fragmentation (AIF) and microscopy imaging, allowing correlation of metabolic activity with cellular phenotypes. In practice, cells or tissues are incubated with 13C-labeled nutrients (e.g., U-13C-glucose), followed by imaging MS and computational registration to assign metabolic data to individual cells. The method successfully revealed substantial heterogeneity in lipogenic acetyl-CoA pool labeling within tumors, demonstrating higher glucose-dependent synthesis of saturated fatty acids in cancer cells compared to healthy tissue [30].

FRET Nanosensors offer an alternative optical approach using genetically encoded biosensors. These sensors employ bacterial periplasmic binding proteins fused between cyan and yellow fluorescent proteins. Upon metabolite binding, conformational changes alter FRET efficiency, reporting metabolite concentration dynamics with subcellular resolution [32]. Although FRET sensors monitor only single compounds rather than comprehensive fluxes, they provide unparalleled temporal resolution for tracking rapid metabolic changes within living cells. The technical protocol involves transfection with sensor constructs, followed by live-cell fluorescence ratio imaging before and after environmental perturbations [32].

Computational Inference Methods

Machine Learning-Based Flux Prediction represents a complementary approach that bypasses experimental complexities. ML-Flux employs artificial neural networks trained on known isotope pattern-flux relationships to decipher complex labeling data and predict metabolic fluxes [33]. The framework uses variable-size isotope labeling patterns as input, imputes missing data via partial convolutional neural networks, and outputs mass-balanced fluxes. Validation shows ML-Flux computes fluxes more accurately and rapidly than traditional least-squares MFA software, with >90% accuracy in central carbon metabolism models [33]. Implementation requires feeding GC-MS or LC-MS isotopologue data into pre-trained models available through the metabolicflux.org platform.

Transcriptome-Based Flux Inference methods leverage gene expression data to estimate metabolic activity. scFEA (single-cell flux estimation analysis) utilizes a graph neural network model trained on human metabolic maps to infer cell-wise fluxomes from scRNA-seq data [31]. Similarly, METAFlux applies flux balance analysis to bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data to characterize metabolic heterogeneity and interactions within the tumor microenvironment [34]. These approaches rest on the hypothesis that flux variations correlate nonlinearly with transcriptomic changes in catalyzing enzymes, minimizing total flux imbalance across all cells [31]. Experimental validation of scFEA using matched scRNA-seq and metabolomics data confirmed consistency between predicted fluxes and observed metabolite abundance variations [31].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Single-Cell MFA Methods

| Method | Spatial Resolution | Pathway Coverage | Temporal Resolution | Sample Requirements | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-SpaceM [30] | Single-cell (~μm) | Targeted (e.g., fatty acid synthesis) | End-point measurement | Fixed cells/tissues | Limited to metabolically stable fatty acids |

| FRET Nanosensors [32] | Subcellular | Single metabolites | Real-time (seconds) | Live cell culture | Monitors only one metabolite at a time |

| ML-Flux [33] | Bulk to single-cell* | Comprehensive (central carbon metabolism) | Steady-state | Isotope labeling data | Requires extensive training data |

| scFEA [31] | Single-cell | Genome-scale | Steady-state | scRNA-seq data | Indirect inference from transcriptomics |

Note: ML-Flux can incorporate single-cell data but is not inherently single-cell

Table 2: Application-Based Method Selection Guide

| Research Context | Recommended Method | Key Advantages | Experimental Workflow Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid Metabolism Studies | 13C-SpaceM [30] | Direct measurement of lipid synthesis heterogeneity | High (requires specialized MS expertise) |

| Dynamic Metabolic Tracking | FRET Nanosensors [32] | Real-time subcellular monitoring | Medium (genetic encoding required) |

| High-Throughput Flux Screening | ML-Flux [33] | Rapid, accurate computation for central metabolism | Low (uses standard LC/GC-MS data) |

| Integration with Transcriptomics | scFEA/METAFlux [34] [31] | Correlates gene expression with metabolic activity | Low-medium (requires scRNA-seq data) |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

13C-SpaceM Protocol for Spatial Single-Cell Flux Analysis

The 13C-SpaceM method enables quantification of de novo fatty acid synthesis heterogeneity through the following detailed workflow [30]:

Cell Culture and Labeling:

- Culture cells in standard conditions, then introduce U-13C-glucose tracer for sufficient time to reach isotopic steady-state (typically 72 hours for fatty acids)

- For heterogeneous models, co-culture differentially treated cells (e.g., normoxic GFPneg with hypoxic GFPpos cells) in equal proportions

- Fix cells using appropriate preservation methods compatible with MS imaging

Sample Preparation and Imaging:

- Apply matrix for MALDI imaging to prepared samples

- Perform MALDI-AIF MS in negative ion mode with mass range 600-1000 m/z for lipids and 100-400 m/z for fatty acid fragments

- Acquire microscopy images (brightfield and fluorescence) for cell segmentation

- Register MS images with microscopy data using reference points

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Correct for natural isotope abundance using standard algorithms

- Assign MS pixels to individual cells based on segmentation

- Quantify isotopologue distributions (M+0, M+1, M+2, etc.) for fatty acids in each cell

- Calculate normalized M+0 intensity as indicator of glucose-derived synthesis

- Correlate metabolic heterogeneity with cellular phenotypes using GFP intensity or other markers

Validation studies achieved 87% classification accuracy in distinguishing hypoxic from normoxic cells based solely on palmitate isotopologue profiles, confirming the method's robustness [30].

ML-Flux Protocol for Computational Flux Estimation

ML-Flux provides a machine learning framework for flux quantification from isotope labeling patterns [33]:

Data Preparation:

- Acquire isotope labeling patterns through 13C-glucose, 2H-glucose, or 13C-glutamine tracing experiments

- Measure mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) using GC-MS or LC-MS

- Format MIDs as input vectors, flagging missing values for imputation

Flux Prediction:

- Input MIDs into pre-trained neural network models specific to metabolic network (e.g., central carbon metabolism)

- Apply partial convolutional neural networks to impute missing isotope patterns

- Generate flux predictions through forward propagation in artificial neural networks

- Calculate remaining fluxes using null space basis of the metabolic model

Validation and Quality Control:

- Compare model-predicted MIDs with experimental measurements

- Assess flux prediction accuracy using reserved testing data

- Check statistical acceptability with reduced chi-squared test (R² values typically 0.9-1 for validated predictions)

- Report standard errors for individual flux predictions based on error distributions in test data

The ML-Flux online resource (metabolicflux.org) democratizes implementation, requiring only isotopologue data input without custom model building [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Single-Cell MFA

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope Tracers | U-13C-glucose, 13C-glutamine, 13C15N-glutamine [35] | Metabolic pathway tracing with stable isotopes |

| FRET Nanosensors | FLIPglu, FLIPmal, FLIPrib [32] | Live-cell metabolite concentration monitoring |

| MS Matrix Compounds | α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid [30] | Enables MALDI ionization for spatial metabolomics |

| Computational Tools | SIMPEL R package [35] | Automated processing of HRMS isotopologue data |

| Cell Labeling Reagents | GFP constructs [30] | Cell identification in heterogeneous co-cultures |

Integrated Data Analysis Workflows

SIMPEL for HRMS Data Processing The Stable Isotope-assisted Metabolomics for Pathway ELucidation (SIMPEL) platform addresses critical bottlenecks in processing high-resolution mass spectrometry data from dual-isotope labeling experiments [35]. This R package automates post-processing of isotope-enriched metabolomics datasets by:

- Enumerating isotopologues for given chemical formulas through precise m/z tolerances

- Identifying isotopologues from libraries of chemical formulae and retention times

- Calculating isotopologue distributions and average labeling per compound

- Correcting for natural abundance using IsoCorrectoR

- Enabling global analyses (PCA, clustering) of compounds based on label enrichment

Application of SIMPEL to 13C15N-glutamine labeling in Arabidopsis roots demonstrated improved flux resolution and reduced confidence intervals for active metabolite pool estimates compared to single-isotope approaches [35].

Dual-Isotope Labeling Advantages Combining multiple heavy isotopes (e.g., 13C and 15N) in a single experiment provides several analytical advantages [35]:

- Enables distinction between active metabolite pools and inactive/unlabeled pools

- Provides additional constraints for flux estimation, improving precision

- Allows resolution of bifurcated pathways through element-specific tracing

- Reduces the number of separate experiments required for comprehensive network analysis

Decision Framework for Single-Cell MFA Method Selection

The evolving landscape of single-cell metabolic flux analysis offers researchers diverse technological paths for investigating metabolic heterogeneity. Experimental approaches like 13C-SpaceM provide direct spatial measurement capabilities but require specialized instrumentation, while computational methods like ML-Flux and scFEA offer accessibility and integration with multi-omics data at the cost of direct measurement [33] [30] [31]. The optimal choice depends critically on research priorities: spatial context, pathway coverage, temporal dynamics, and sample availability.

Future methodology development will likely focus on integrating experimental and computational approaches, enhancing spatial resolution, expanding pathway coverage, and improving temporal dynamics. Technologies like SIMPEL that leverage dual-isotope labeling with HRMS demonstrate how innovative data extraction can maximize information from single experiments [35]. As these tools mature, single-cell flux analysis will increasingly illuminate metabolic heterogeneity in cancer, developmental biology, and therapeutic development, providing unprecedented insights into cellular physiology and disease mechanisms.

In structural biology, determining the three-dimensional structures of proteins and their complex interactions is fundamental to understanding cellular mechanisms and advancing drug discovery. For many sophisticated techniques, particularly Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and Mass Spectrometry (MS), this task requires the incorporation of stable isotopes into proteins. These non-radioactive isotopes, such as ²H (Deuterium), ¹³C, and ¹⁵N, serve as sensitive probes that provide atomic-level resolution data without altering the chemical or biological properties of the molecule [36] [37]. This guide objectively compares the two primary analytical platforms—NMR and MS—used to interpret data from isotopic labeling experiments, detailing their respective capabilities, optimal applications, and performance metrics to inform research and development strategies.

The selection between uniform and selective labeling strategies is a critical first step in experimental design. Uniform labeling, where all atoms of a specific element in a protein are replaced with an NMR-active isotope (e.g., uniform ¹³C, ¹⁵N), is the standard starting point for structural studies [12] [38]. Conversely, selective labeling incorporates isotopes only at specific sites or amino acid types, which dramatically simplifies NMR spectra for larger proteins or for studying specific functional regions, such as active sites or binding interfaces [14] [38]. Another powerful approach is segmental labeling, which allows for the isotopic labeling of a specific protein domain rather than the entire molecule. This is particularly valuable for analyzing multi-domain proteins or specific post-translational modifications [37]. The choice of strategy directly impacts the complexity of the data and the type of structural information that can be obtained.

Comparison of Measurement Techniques: MS vs. NMR

Isotopic labeling provides a bridge to atomic-level structural data, but the platform used to detect these labels defines the nature and scope of the information obtained. NMR spectroscopy and Mass Spectrometry offer complementary strengths, making them suitable for different research questions.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy excels at providing detailed information on the local chemical environment, three-dimensional structure, and real-time dynamics of proteins in solution. A key advantage is its ability to distinguish between different isotopomers—molecules that are labeled with isotopes in identical positions [26] [39]. For instance, NMR can determine the specific carbon atom within a glutamate side chain that is ¹³C-labeled, providing direct evidence of the metabolic pathway that produced it. This makes it indispensable for tracking the fate of individual atoms from a labeled precursor through metabolic transformations, an approach known as Stable Isotope-Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM) [26] [39]. Furthermore, NMR's unique isotope-editing capabilities can filter complex mixtures to display only signals from atoms connected to an NMR-active nucleus like ¹³C or ³¹P, leading to significant spectral simplification [26] [39].

Mass Spectrometry (MS), in contrast, is unparalleled in its sensitivity for detecting mass changes and is highly effective at identifying and quantifying different isotopologues—molecules that differ in the total number of tracer atoms, regardless of their position [26] [40]. This capability is central to techniques like Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture (SILAC) for quantitative proteomics and Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) [11]. MS requires much smaller sample quantities than NMR and is easily integrated with separation techniques like liquid chromatography (LC), making it ideal for high-throughput profiling. However, while MS can determine that a metabolite has gained two ¹³C atoms, it typically cannot distinguish which specific carbons are labeled without additional fragmentation experiments (MS/MS) [26] [40].

Table 1: Core Technical Capabilities of NMR and MS

| Feature | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Mass Spectrometry (MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | 3D Structure, Atomic Environment, Dynamics, Isotopomers | Mass, Identity, Quantity, Isotopologues |

| Isotope Detection | Direct (¹³C, ¹⁵N) & indirect via ¹H | Mass shift (e.g., ¹³C vs. ¹²C) |

| Key Strength | Positional isotope analysis; Study of intact complexes | High sensitivity; High throughput |

| Sample Requirement | ~0.1-1 mg, high purity [39] | Nanogram to microgram, can be complex mixtures |

| Throughput | Lower (minutes to hours per sample) | High (minutes per sample with LC) |

Table 2: Performance in Key Structural Biology Applications

| Application | NMR Performance & Role | MS Performance & Role |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Determination | High (for proteins < ~50 kDa); Provides atomic-resolution structures and dynamics in solution. | Low for 3D structure; High for identifying cross-linked peptides to constrain structural models. |

| Protein-Ligand Interaction Studies | High; Can pinpoint binding site and conformational changes via chemical shift perturbations. | Medium; Can detect binding via hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX) or native MS. |

| Metabolic Pathway Tracing (SIRM) | High; Uniquely identifies positional isotopomers for detailed pathway mapping. [26] [39] | High; Excellent for quantifying isotopologue abundances and flux modeling. [26] [40] |

| Analysis of Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) | High with selective labeling; Can determine site-specific structural and dynamic effects of PTMs. [37] | High; Excellent for identifying and mapping PTM sites proteome-wide. |

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the typical experimental processes for structural studies using NMR and interaction studies using MS.

NMR Protein Structure Determination Workflow

MS-Based Protein Interaction Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Site-Specific Isotopic Labeling in Mammalian Cells

Studying proteins that require mammalian expression systems for proper folding and post-translational modifications has been challenging due to the high cost of isotope-labeled amino acids. A recent protocol provides a cost-effective alternative by leveraging endogenous transaminase enzymes to convert labeled α-ketoacid precursors into the corresponding amino acids [14].

Detailed Protocol:

- Medium Preparation: Prepare a custom culture medium (e.g., based on DMEM) that excludes the specific amino acid targeted for labeling (e.g., tyrosine, phenylalanine, leucine) [14].

- Precursor Supplementation: Supplement the medium with the cognate α-ketoacid precursor (e.g., p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate for tyrosine) at a 1:2 molar ratio relative to the standard amino acid concentration. The precursor is synthesized with ¹³C at the desired positions [14].

- Cell Transfection and Expression: Transfect HEK293T cells with the plasmid encoding the target protein using polyethylenimine (PEI) as a transfection reagent. Culture the cells in the custom medium for 48 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [14].

- Validation and Analysis: Harvest the cells and prepare NMR samples. As demonstrated for proteins like carbonic anhydrase II (CA II), this method yields sufficient protein for fast 2D ¹H,¹³C NMR spectra, enabling the study of conformational changes upon ligand binding in cell lysates or even in intact cells [14].

Stable Isotope-Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM) for Pathway Tracing

SIRM is a powerful approach to map the flow of atoms from labeled precursors through metabolic networks, which is crucial for understanding disease mechanisms like cancer [26] [39].

Detailed Protocol:

- Tracer Administration: Incubate cells, tissues, or model organisms with an isotope-enriched precursor. Common tracers include [U-¹³C]-glucose to track glycolysis and Krebs cycle activity, or [U-¹³C,¹⁵N]-glutamine to probe glutaminolysis [26].

- Sample Extraction: At designated time points, extract metabolites using a solvent system like methanol:acetonitrile:water (2:2:1 v/v) to quench metabolism and preserve the labeling patterns.

- Parallel Analysis by NMR and MS:

- NMR Analysis: Redissolve the extract in a buffered D₂O solution. Acquire ¹H-¹³C 2D TOCSY or HSQC spectra. The ¹³C satellite peaks in the TOCSY spectrum reveal the site-specific enrichment (isotopomers), allowing researchers to distinguish between different metabolic pathways [26] [39].

- MS Analysis: Analyze the same extract via LC-MS. Use high-resolution mass spectrometry to detect the mass shifts corresponding to the number of incorporated heavy atoms (isotopologues). Software tools are then used to quantify the relative abundance of each isotopologue for flux modeling [26] [40].

- Data Integration: Combine the positional information from NMR with the high-sensitivity quantification from MS to build a comprehensive, atom-resolved metabolic fate map [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials required for conducting isotopic labeling experiments in structural and chemical biology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Isotopic Labeling

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| ¹³C-Glucose | A universally used labeled carbon source for metabolic flux analysis (MFA) and for producing uniformly ¹³C-labeled proteins in bacterial expression systems [26] [12]. |

| ¹⁵N-Ammonium Salts | A primary nitrogen source for achieving uniform ¹⁵N-labeling of proteins for backbone NMR assignment [12] [11]. |

| Deuterated Water (D₂O) | Used for solvent contrast variation in SAS studies, for buffering NMR samples to avoid strong water signals, and for in vivo labeling of lipids via ²H₂O ingestion [26] [37]. |

| Selective Labeling Kits (e.g., for Methyl groups) | Kits containing precursors like ¹³C-α-ketoisovalerate for specific labeling of Ile, Leu, Val methyl groups in a deuterated background, crucial for NMR studies of large proteins [12] [14]. |

| SILAC Kits (e.g., ¹³C₆-Arg, ¹³C₆-Lys) | Contain heavy isotope-labeled essential amino acids for quantitative proteomics using Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture (SILAC) in mammalian cells [11]. |

| Isotope-Labeled Amino Acids | Used for residue-specific labeling in proteins expressed in any host system, including mammalian cells, or for reverse labeling (unlabeling) to simplify NMR spectra [14] [38]. |

| α-Ketoacid Precursors | Cost-effective precursors for selective isotope labeling of specific amino acid side chains in mammalian expression systems, as an alternative to expensive labeled amino acids [14]. |

Concluding Synthesis

The choice between MS and NMR for analyzing isotopically labeled samples is not a matter of which technique is superior, but rather which is best suited to the specific biological question. The following diagram summarizes the decision-making logic for selecting the appropriate technique.

Technique Selection Logic

For research focused on determining the high-resolution 3D structure and internal dynamics of proteins under 50 kDa, or for characterizing protein-ligand interactions with atomic precision, NMR spectroscopy is the definitive tool, especially when combined with selective labeling strategies [37] [38]. Conversely, when the objective is system-wide profiling, such as mapping metabolic fluxes with high sensitivity or conducting quantitative proteomics on complex samples, Mass Spectrometry is the more powerful and efficient platform [26] [40] [11].

The most robust and informative structural biology studies often leverage the complementary strengths of both NMR and MS. An integrated approach, where MS provides high-throughput identification and quantification of interactions and modifications, and NMR validates these findings and provides detailed mechanistic insights into structure and dynamics, represents the gold standard. As labeling strategies continue to evolve, particularly for challenging targets like membrane proteins and multi-protein complexes, this synergistic use of NMR and MS will be paramount in driving discoveries in basic research and drug development.

In the field of quantitative proteomics, isotopic labeling techniques coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) have become indispensable tools for accurately measuring protein abundance and dynamics. Among the most prominent methods are Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture (SILAC), Tandem Mass Tags (TMT), and Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation (iTRAQ). These techniques enable researchers to perform multiplexed relative and absolute quantification of proteins across different biological states, providing crucial insights into cellular signaling pathways, disease mechanisms, and drug responses. This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of these three foundational technologies, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and applications within modern proteomics research, particularly in comparison to other structural biology techniques like NMR spectroscopy.

Technical Comparison of SILAC, TMT, and iTRAQ

The following table provides a systematic comparison of the three major quantitative proteomics techniques, highlighting their key characteristics, performance metrics, and ideal use cases.

| Feature | SILAC | iTRAQ | TMT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labeling Type | Metabolic incorporation [41] | Chemical (isobaric tags) [41] | Chemical (isobaric tags) [41] |

| Labeling Stage | In vivo, during cell culture [41] | In vitro, post-digestion [41] | In vitro, post-digestion [41] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Typically 2-3 (up to 5 with newer labels) [41] | 4-8 plex [41] [42] | 6-16 plex [41] [42] |

| Quantification Basis | MS1 precursor intensity [41] [43] | MS2/MS3 reporter ions [41] [44] | MS2/MS3 reporter ions [41] [43] |

| Sample Compatibility | Limited to cell cultures and model organisms (SILAM) [41] [42] | Broad (cells, tissues, biofluids) [41] | Broad (cells, tissues, biofluids) [41] |

| Key Advantage | High accuracy; no chemical modification [41] [42] | Comprehensive proteome coverage; PTM analysis [41] | Highest multiplexing; robust quantification [41] |

| Key Limitation | Not suitable for tissue/fluid samples [42] | Ratio compression [41] [44] | Ratio compression; high cost [41] [42] |

| Best For | Dynamic processes in cell cultures (e.g., protein turnover) [41] | Large-scale studies & post-translational modifications [41] | High-throughput screening of multiple conditions [41] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflow

SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture)

The SILAC methodology relies on the metabolic incorporation of stable isotope-labeled "heavy" amino acids (e.g., lysine and/or arginine) into the entire proteome of growing cells [41].

Detailed Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Two or more cell populations are cultured in parallel in media that are identical except for the form of specific essential amino acids. The "light" medium contains normal amino acids, while the "heavy" medium contains isotope-labeled analogs (e.g., (^{13}C6), (^{15}N4)) [41].

- Incorporation: Cells are passaged for several generations (typically 5-7) to ensure complete ((>)97%) incorporation of the labeled amino acids into all newly synthesized proteins [41].

- Sample Mixing: After treatment, cells from different conditions are harvested, and protein extracts are combined in equal ratios. This mixing at the beginning of sample processing minimizes technical variability [41].

- Standard Proteomics Processing: The mixed protein sample is digested with trypsin. The resulting peptides are then analyzed by LC-MS/MS [41].

- Data Analysis: Quantification is achieved by comparing the MS1 precursor ion intensities of the paired "light" and "heavy" peptides, which appear as distinct peaks in the mass spectrum separated by a predictable mass difference [41] [43].

iTRAQ/TMT (Isobaric Chemical Labeling)

iTRAQ and TMT share a nearly identical workflow, relying on isobaric chemical tags that covalently bind to peptide amines post-digestion [41] [44].

Detailed Protocol:

- Individual Sample Processing: Proteins from each experimental condition (e.g., control vs. treated tissues) are extracted and digested individually into peptides [41].

- Chemical Labeling: The peptides from each sample are labeled with a different isobaric tag from the iTRAQ (4-8 plex) or TMT (6-16 plex) reagent set. These tags have the same total mass, ensuring that a given peptide from any sample appears at the same m/z in MS1 scans [41] [44].

- Sample Pooling: All labeled peptide samples are combined into a single mixture for simultaneous analysis [41].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: The pooled sample is analyzed by LC-MS/MS. During tandem MS (MS2), the isobaric tags fragment to produce low-mass reporter ions (e.g., 114-117 Da for iTRAQ 4-plex). The relative intensities of these reporter ions in the MS2 spectrum reflect the relative abundance of the peptide in each original sample [41] [44].