Navigating Alternative Optimal Solutions in Flux Balance Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Validation

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone of constraint-based metabolic modeling, but its predictions are often non-unique, with numerous alternative optimal solutions yielding the same objective value.

Navigating Alternative Optimal Solutions in Flux Balance Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Validation

Abstract

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone of constraint-based metabolic modeling, but its predictions are often non-unique, with numerous alternative optimal solutions yielding the same objective value. This phenomenon presents significant challenges in interpreting results for applications in systems biology, metabolic engineering, and drug development. This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding, analyzing, and validating these alternative solutions. We explore the foundational concepts of optimal solution spaces and their biological implications, detail advanced methodological frameworks like TIObjFind and loopless FBA for solution refinement, discuss troubleshooting strategies to address thermodynamic infeasibility and overfitting, and finally, present rigorous validation and model selection techniques to ensure biological relevance. This integrated approach empowers researchers to move beyond single-solution predictions toward robust, biologically consistent flux distributions.

Understanding the Landscape of Alternative Optimality in Metabolic Networks

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are alternative optimal solutions in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)? In FBA, an alternative optimal solution occurs when multiple different distributions of metabolic fluxes (the rates at which metabolic reactions occur) yield the same optimal value for a biological objective, such as maximal biomass production [1]. The entire set of these optimal flux distributions forms a solution space known as a polyhedron [1].

2. Why do alternative optimal solutions pose a challenge? The existence of numerous alternative optimal solutions complicates the biological interpretation of FBA results [1]. Because thousands to millions of flux patterns can produce the same optimal performance, it can be difficult to identify the one actually used by a cell, which limits the predictive accuracy and practical utility of the model for applications like metabolic engineering or drug development [2] [1].

3. How can I identify if my FBA problem has alternative optimal solutions? Common computational methods to characterize the optimal solution space include:

- Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Determines the minimum and maximum possible flux each reaction can carry while still achieving the optimal objective value [1].

- Comprehensive Polyhedra Enumeration FBA (CoPE-FBA): A method that fully characterizes the optimal solution space by enumerating its vertices, rays, and linealities [1].

4. What is the biological significance of these solutions? Alternative optimal solutions are not just mathematical artifacts; they reflect a cell's inherent metabolic flexibility [1]. Cells can use different pathways to achieve the same physiological goal, allowing them to adapt to various environmental conditions or genetic perturbations [2]. Analyzing these alternatives can reveal critical subnetworks and backup pathways within the metabolic network [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Analyzing Alternative Optimal Solutions

| Problem Description | Symptoms | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Metabolic Flexibility | FVA shows a wide flux range for many reactions, making biological interpretation difficult. | Apply CoPE-FBA to decompose the solution space into its fundamental components (vertices, rays, linealities) to understand the underlying network topology causing the flexibility [1]. |

| Misalignment with Experimental Data | The single flux distribution predicted by a standard FBA does not match experimentally measured flux data. | Use a framework like TIObjFind, which integrates FBA with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) to infer a context-specific objective function that better aligns the model with experimental data [2]. |

| Computational Intractability | The model is too large for a complete enumeration of the optimal solution space. | Exploit the finding that optimal solution spaces are often determined by a few small subnetworks. Use preprocessing to fix invariable fluxes, then focus analysis on the remaining variable subnetwork [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing the Optimal Solution Space with CoPE-FBA

1. Objective: To comprehensively characterize all optimal flux distributions in a genome-scale metabolic model.

2. Background: The CoPE-FBA method describes the entire optimal solution space in terms of three types of vectors [1]:

- Vertices: Represent fundamental pathways through the network that achieve the optimal yield.

- Rays: Represent irreversible thermodynamically infeasible cycles that can operate at any rate without affecting the objective.

- Linealities: Represent reversible internal cycles that can operate in either direction without affecting the objective.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Solve the Base FBA Problem. Maximize your biological objective (e.g., biomass growth) using a linear programming solver to find the optimal objective value.

- Step 2: Fix the Objective. Add a constraint to the model that forces the objective function to equal the optimal value found in Step 1. This defines the "optimal solution space" or polyhedron.

- Step 3: Preprocessing. Identify and fix the values of reactions that have identical fluxes across all optimal solutions. This reduces the problem's complexity [1].

- Step 4: Polyhedra Enumeration. Use a computational tool like Polco to enumerate the vertices, rays, and linealities of the resulting polyhedron [1].

- Step 5: Topological Analysis. Map the computed vertices, rays, and linealities back onto the metabolic network to identify the key subnetworks responsible for the alternative solutions.

4. Expected Outcome: A compact, network-topological understanding of the metabolic flexibility in optimal states, often arising from combinatorial flux patterns in just a few subnetworks [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (e.g., Recon, iJO1366) | A stoichiometric representation of all known metabolic reactions in an organism. Serves as the core computational framework for performing FBA [1]. |

| Linear Programming (LP) Solver (e.g., COBRA Toolbox) | Software that performs the numerical optimization to find the flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes a defined objective function [1]. |

| CoPE-FBA Pipeline | Specialized computational software for the comprehensive enumeration of the optimal flux space, translating mathematical solutions into biologically interpretable subnetworks [1]. |

| TIObjFind Framework (MATLAB) | A data-driven optimization framework that integrates FBA with Metabolic Pathway Analysis to identify objective functions that align model predictions with experimental data [2]. |

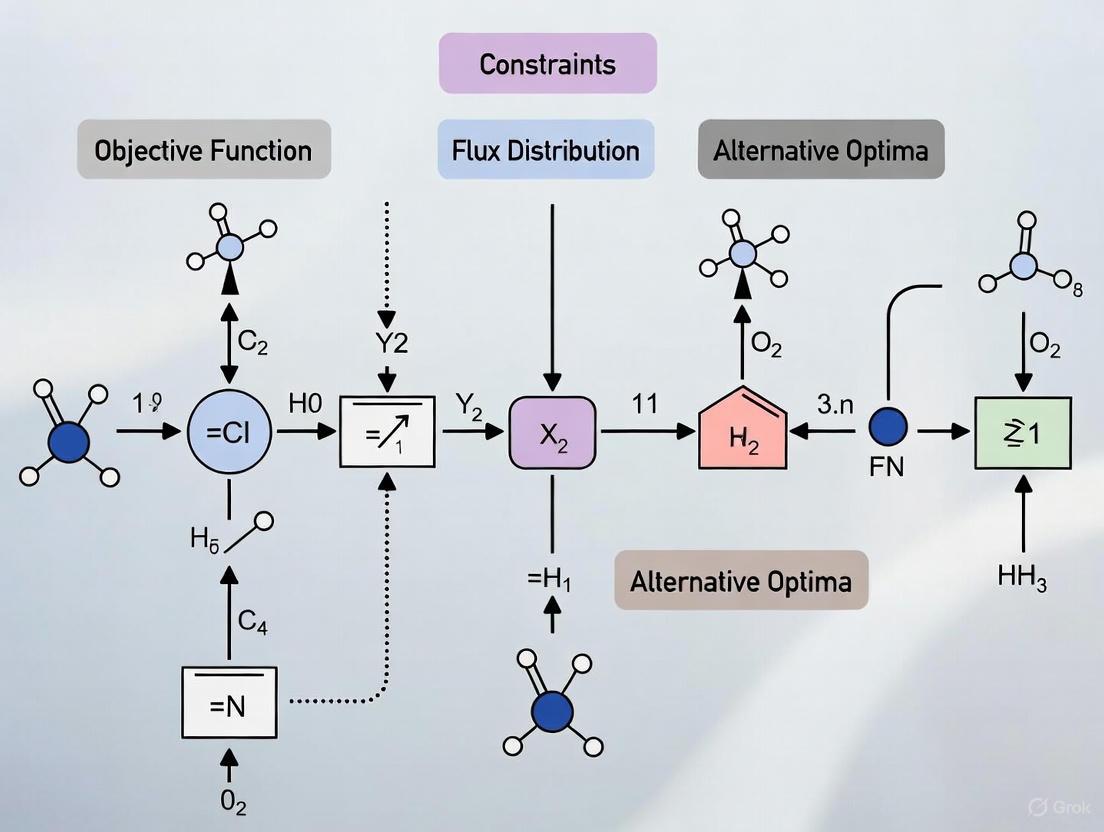

Visualizing the Concepts

The following diagram illustrates the core components of an optimal solution space in FBA, as characterized by methods like CoPE-FBA.

In Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), the set of all possible metabolic flux distributions that satisfy stoichiometric, thermodynamic, and capacity constraints forms a solution space [3] [4]. This space represents all metabolic states available to a cell under given conditions. When an optimality criterion, such as maximizing biomass growth, is applied, this region is more specifically called the optimal solution space (OS) [3]. Understanding the complete geometry of this space is crucial for interpreting FBA results, as the single flux vector returned by a standard FBA calculation represents just one point within a potentially vast set of alternative optimal solutions [3] [1].

The solution space is mathematically defined as a convex polyhedron in a high-dimensional flux space [1] [4]. For realistic genome-scale models, this polyhedron can be enormously complex. Traditional FBA provides limited biological insight because it returns only a single flux vector, typically located at an extreme point (vertex) of the polyhedron [3]. Conversely, exhaustive methods like Elementary Mode or Extreme Pathway analysis generate an intractably large number of basis vectors [3] [1]. This guide explores the polyhedral structure of the solution space—characterized by its vertices, rays, and linealities—and provides methodologies for its analysis and troubleshooting.

Core Concepts: The Building Blocks of the Solution Space

The optimal solution space polyhedron can be described in terms of three fundamental topological features, each with a specific biological and mathematical interpretation [1].

Table 1: Core Components of an FBA Solution Space Polyhedron

| Component | Mathematical Definition | Biological Interpretation | Network Topology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertices | Corner points of the polyhedron; cannot be expressed as a convex combination of other points in the space. | Alternative metabolic pathways or routes that achieve the same optimal objective value (e.g., biomass yield) [1]. | Paths through the metabolic network [1]. |

| Rays | Directions v such that for any point v' in the polyhedron, v' + υv is also in the polyhedron for all υ ≥ 0. |

Irreversible metabolic cycles that can operate at any rate without affecting the objective function. Often correspond to thermodynamically infeasible loops [1]. | Irreversible cycles in the network [1]. |

| Linealities | Directions v such that for any point v' in the polyhedron, v' + µv is also in the polyhedron for all values of µ. |

Reversible metabolic cycles that can operate in either direction at any rate without affecting the objective function [1]. | Reversible cycles in the network [1]. |

Figure 1: The relationship between the mathematical description of a polyhedron and the topology of the underlying metabolic network. Vertices correspond to paths, while linealities and rays correspond to cycles.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

FAQ 1: My FBA solution is not unique. How can I characterize the full range of alternative optimal solutions?

Issue: A single FBA solution often does not represent the complete biological reality, as many alternative flux distributions can achieve the same optimal objective value [1] [4]. Relying on a single solution can lead to incomplete or misleading conclusions.

Solution: Employ methods that characterize the entire optimal solution space rather than a single point. Two advanced methodologies are recommended:

- Comprehensive Polyhedra Enumeration FBA (CoPE-FBA): This method provides a complete description of the optimal solution space by enumerating its vertices, rays, and linealities. It reveals that the vast number of optimal flux patterns often results from a combinatorial explosion within just a few small subnetworks, allowing for a compact, topology-based understanding [1].

- Solution Space Kernel (SSK) Analysis: This approach characterizes the solution space by extracting a bounded, low-dimensional kernel (SSK). It separates fixed fluxes from variable ones and identifies a compact subregion containing the most biologically relevant flux variations, supplemented by rays that describe unbounded directions [3].

Experimental Protocol: CoPE-FBA Workflow

- Model Preparation: Start with a genome-scale stoichiometric model. Avoid using artificially high flux bounds, as this can cause rays and linealities to disappear and lead to a vertex explosion [1].

- Preprocessing: Identify and separate all reaction fluxes that are fixed across the entire optimal solution space. This step reduces the dimensionality of the problem [1].

- Polyhedron Enumeration: Use specialized software (e.g., Polco) to compute the vertices, rays, and linealities of the FBA polyhedron [1].

- Subnetwork Analysis: Analyze the resulting extremities to identify the key subnetworks where flux variability occurs. CoPE-FBA typically shows that the solution space is determined by only a few such subnetworks (often 5-10% of all reactions) [1].

- Interpretation: Biologically interpret the vertices as alternative pathways, and the rays/linealities as thermodynamically infeasible loops or permissible cycles [1].

FAQ 2: The solution space is too large to handle. How can I simplify it for interpretation?

Issue: The complete set of optimal flux distributions can contain millions of points, making it impossible to interpret manually [1] [4].

Solution: Leverage the insight that flux variability is typically confined to a small subset of the network. Both CoPE-FBA and SSK analysis provide simplified representations.

- CoPE-FBA Approach: This method demonstrates that the entire optimal solution space can be compactly described by the topology of a few small subnetworks. The reactions within each subnetwork have correlated fluxes, and the vast number of solutions arises from combinatorial possibilities within these modules [1].

- SSK Approach: This method constructs a bounded "kernel" that captures the core of the biologically relevant flux variations. The kernel is described by a manageable number of parameters and its shape can be delineated by a set of mutually orthogonal, maximal chords. For high-dimensional kernels, a "Peripheral Point Polytope" (PPP) with only ~4N to 6N vertices can approximate the central 80% of the kernel [3].

Table 2: Methods for Characterizing and Simplifying the FBA Solution Space

| Method | Key Principle | Primary Output | Handles Unbounded Spaces? | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoPE-FBA [1] | Decomposes space into vertices, rays, and linealities from a few subnetworks. | Complete list of extremities (vertices, rays, linealities). | Yes, natively. | Topological understanding of all optimal states. |

| SSK Analysis [3] | Defines a bounded kernel and supplemental rays for unbounded directions. | Bounded kernel polytope and a set of ray vectors. | Yes, by separating bounded and unbounded parts. | Focusing on biologically plausible, bounded flux ranges. |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) [4] | Finds min/max possible flux for each reaction individually. | A range for every reaction flux. | Only with artificial bounds. | Quick assessment of flux flexibility per reaction. |

| Random Sampling with FVA Bounds [4] | Fixes variable fluxes to random values within their FVA range and re-optimizes. | A collection of feasible flux distributions. | Depends on implementation. | Probing the space for correlated reactions without full enumeration. |

FAQ 3: My model contains thermodynamically infeasible cycles. How do I identify and remove them?

Issue: The solution space may contain rays and linealities that represent cycles capable of infinite flux without any net substrate consumption or product formation. These are often thermodynamically infeasible and can skew the interpretation of results [1].

Solution:

- Identification: Perform a CoPE-FBA analysis. The output will explicitly list ray and lineality vectors. Biologically, these correspond to the irreversible and reversible cycles, respectively, as shown in Figure 1 [1].

- Prevention during Modeling: A common practice that inadvertently creates these cycles is modeling reversible reactions as a single reaction with negative and positive bounds. Instead, split reversible reactions into separate forward and reverse reactions. This allows for the assignment of distinct catalytic constants (Kcat values) and helps prevent unrealistic flux loops [5].

- Constraining: Use the

SSKernelsoftware package to perform Solution Space Kernel analysis. A key stage in its algorithm is to identify directions in flux space for which the solution space is unbounded and to find the corresponding ray vectors. The kernel is then constructed to be bounded, separating these physically implausible unbounded aspects [3].

Figure 2: An example of an internal cycle (lineality) that can be identified and separated through polyhedral analysis.

FAQ 4: How can I validate that my FBA predictions are reliable given the large solution space?

Issue: The existence of a large solution space means that a single FBA-predicted flux distribution may not be a reliable representation of the in-vivo state [6].

Solution: Adopt a multi-faceted validation strategy that goes beyond reporting a single flux vector.

- Compare against 13C-MFA Data: The most robust validation involves comparing FBA predictions against intracellular fluxes estimated via 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA). This experimental technique uses isotopic labeling data to pin down a more specific flux map within the solution space [6].

- Inspect the Solution Space: Use the methods described above (e.g., CoPE-FBA, SSK, Sampling) to understand the range and correlations of possible optimal fluxes. Report on the robustness of your key predictions—is the flux through a target reaction stable across the entire solution space, or does it vary widely? [4]

- Incorporate Additional Constraints: Integrate experimental data such as transcriptomics, proteomics (enzyme abundance), and exometabolomics to further constrain the solution space and improve the biological relevance of predictions. Hybrid methods like NEXT-FBA use neural networks to relate exometabolomic data to intracellular flux constraints [7] [4].

- Test Multiple Objective Functions: Systematically evaluate alternative biological objective functions to identify those that generate flux predictions best aligned with experimental data [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Resources for Solution Space Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Reference/Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRApy | Software Toolbox | A widely used Python package for constraint-based modeling, including performing FBA and FVA. | [5] |

| SSKernel | Software Package | Publicly available tool for defining and computing the Solution Space Kernel (SSK) of an FBA model. | [3] |

| CoPE-FBA Pipeline | Computational Method | A pipeline for Comprehensive Polyhedra Enumeration in FBA, identifying vertices, rays, and linealities. | [1] |

| Polco | Software Tool | Used for determining Extreme Pathway Analysis and Elementary Flux Modes, which can be applied to FBA polyhedra. | [1] |

| NEXT-FBA | Computational Method | A hybrid approach that uses neural networks trained on exometabolomic data to derive improved constraints for intracellular fluxes. | [7] |

| ECMpy | Software Workflow | A workflow for incorporating enzyme constraints into genome-scale models without altering the stoichiometric matrix. | [5] |

| 13C-MFA | Experimental Technique | Provides estimated intracellular fluxes for validating FBA predictions and constraining solution spaces. | [6] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are alternate optimal solutions in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), and why do they matter? Alternate optimal solutions are distinct flux distributions through a metabolic network that all produce the same optimal biomass yield [8]. They are significant because they reveal the inherent redundancy in metabolic networks, allowing organisms to achieve the same growth outcome using different combinations of reaction fluxes. This redundancy is a key source of metabolic flexibility and robustness [8].

Q2: How does redundancy in metabolic networks contribute to metabolic flexibility? Redundancy, often in the form of alternative metabolic pathways, allows an organism to maintain growth even when a primary reaction is disrupted. For example, in the event of a gene deletion, flux can be "rerouted" through alternative pathways, a process known as metabolic plasticity. This is the basis for synthetic lethal pairs, where only the simultaneous deletion of two reactions abrogates growth [9].

Q3: What is the biological difference between a plastic synthetic lethal (PSL) and a redundant synthetic lethal (RSL)? These are two classes of synthetic lethal pairs that illustrate different redundancy mechanisms [9]:

- PSL (Plastic Synthetic Lethal): In a PSL pair, only one reaction is active at a time. The second reaction becomes active only when the first is deleted, demonstrating a switch-like, plastic response.

- RSL (Redundant Synthetic Lethal): In an RSL pair, both reactions are active simultaneously under normal conditions. The loss of one does not stop growth because the other is already carrying a portion of the flux, showing built-in redundancy.

Q4: My gapfilled metabolic model grows, but the flux distribution looks unusual. Is this an error? Not necessarily. The gapfilling algorithm finds a minimal set of reactions to enable growth but does not always select the most biologically relevant pathway [10]. The solution you see is one of potentially many alternate solutions. You can force the algorithm to find a different solution by manually constraining the flux of the unexpected reaction to zero and re-running the gapfilling process [10].

Q5: What is a high-flux backbone (HFB), and is it conserved across alternate optimal solutions? The high-flux backbone (HFB) is the subnetwork of reactions that carry high flux in a given condition [8]. Research shows that the HFB from one optimal solution is largely conserved across other alternate optimal solutions in E. coli, but only moderately conserved in S. cerevisiae [8]. However, the HFB can vary significantly when considering near-optimal solutions, highlighting the network's plasticity [8].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Gapfilling produces a model that grows, but you suspect it is biologically inaccurate.

- Potential Cause: The gapfilling algorithm uses a cost function that penalizes certain reactions (e.g., transporters, non-KEGG reactions) but may still add them if they provide the shortest path to growth [10]. The solution is mathematically correct but may not reflect the organism's true biology.

- Solution:

- Change the Media: Gapfill on a minimal media instead of the default "complete" media. This forces the model to biosynthesize more compounds and can lead to a more accurate solution [10].

- Manual Curation: Inspect the added reactions. If a reaction's addition is not desired, use the "Custom flux bounds" feature to set its flux to zero and re-run the gapfilling to find an alternative solution [10].

- Stack Gapfillings: First, gapfill on a rich media to establish base growth, then gapfill the same model on your desired condition to add only the minimal set of reactions needed for that specific condition [10].

Problem 2: Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) shows a wide range of possible fluxes for many reactions.

- Potential Cause: This is a classic sign of extensive alternate optimal solutions and redundancy in the network. The model does not have enough constraints to uniquely determine the flux for these reactions [8].

- Solution:

- Add Transcriptomic Data: Integrate gene expression data to constrain the flux bounds of reactions associated with highly or lowly expressed genes.

- Use a Parsimonious FBA (pFBA): Apply an pFBA approach that minimizes the total sum of absolute flux while achieving optimal growth, which can select for a more biologically relevant solution from the set of alternates.

- Apply the minRerouting Algorithm: For synthetic lethal analysis, use a method like

minReroutingwhich finds a flux solution that minimizes the number of reactions with varying flux between wild-type and mutant states, helping to identify the core set of reactions vital for rewiring [9].

Problem 3: Difficulty identifying which reactions are essential for metabolic rewiring in a synthetic lethal pair.

- Potential Cause: Standard FBA may find a solution that achieves growth after a single reaction deletion but does not highlight which specific reaction flux changes are responsible for the rescue [9].

- Solution: Employ a constraint-based optimisation approach that explicitly minimizes the rerouting between the wild-type and mutant states [9]. This pipeline outputs a "synthetic lethal cluster," which is the set of reactions most vital for the metabolic rewiring that allows the organism to survive the single deletion.

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Analyzing a High-Flux Backbone (HFB) from an FBA Solution This protocol is based on the methodology described by Almaas et al. and subsequent analyses [8].

- Run FBA: Perform Flux Balance Analysis on your metabolic model for a specific environmental condition to obtain a reference flux distribution.

- Calculate Net Flux: For each metabolite in the network, identify all producing and consuming reactions.

- Identify Dominant Fluxes: For each metabolite, find the single reaction that maximally produces it and the single reaction that maximally consumes it within the solution.

- Construct the HFB: The High-Flux Backbone is the union of all reactions identified as dominant producers or consumers for all metabolites in the network. This forms a connected subnetwork representing the primary flux routes.

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Classifying Synthetic Lethal Pairs This protocol helps characterize the nature of redundancy in synthetic lethal pairs [9].

- Identify Synthetic Lethals: Use an algorithm like Fast-SL to find all synthetic lethal reaction pairs (SLPs) in your genome-scale metabolic model.

- Simulate Single Deletions: For a given SLP (Reaction A + Reaction B), run FBA on the single deletion mutants (ΔA and ΔB).

- Analyze Flux Distributions: Examine the flux distributions for reactions A and B in the wild-type model and in each single mutant.

- Classify the SLP:

- Plastic Synthetic Lethal (PSL): If, in the wild-type, one reaction has high flux and the other has zero (or negligible) flux.

- Redundant Synthetic Lethal (RSL): If, in the wild-type, both reactions carry significant, simultaneous flux.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and databases essential for research in this field.

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| KBase | An integrated platform that provides apps for reconstructing, gapfilling, and analyzing metabolic models using FBA [10]. |

| Model SEED Biochemistry Database | A curated database that provides a consistent vocabulary of compounds, reactions, and roles used by KBase and other tools for model reconstruction and gapfilling [10]. |

| SCIP & GLPK Solvers | Optimization solvers used internally by tools like KBase to solve the linear and mixed-integer programming problems at the heart of FBA and gapfilling [10]. |

| FlexFlux | A tool that integrates FBA with regulatory network analysis, allowing users to find steady states of the regulatory network and use them as constraints for FBA [11]. |

| minRerouting Algorithm | A constraint-based optimization approach designed to identify the minimal set of flux changes (the synthetic lethal cluster) required for a network to adapt to a reaction deletion [9]. |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | A computational technique used to determine the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction across all alternate optimal solutions, quantifying the network's flexibility [8]. |

Visualizing Core Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: FBA and Alternate Solutions Workflow

Diagram 2: Synthetic Lethal Classification and Rewiring

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constraint-based computational method used to predict the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, typically optimizing for an objective like biomass production [12]. A key challenge in FBA is the prevalence of alternate optimal solutions—different flux distributions that yield the identical optimal objective value [8]. The High-Flux Backbone (HFB) is a concept introduced to address this. It is a subnetwork comprising reactions that carry locally maximal flow for production and consumption of metabolites within a given flux distribution [8]. This technical support center provides guidelines for researchers grappling with the implications of alternate optima on the identification and interpretation of the HFB in their metabolic models.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the High-Flux Backbone (HFB), and why is its conservation significant?

The High-Flux Backbone (HFB) is a subnetwork identified from a specific flux distribution. It contains the primary flow paths where, for most metabolites, one or two reactions dominantly handle production and consumption [8]. Its significance lies in revealing the core, high-activity routes in a metabolic network under specific conditions.

Investigating its conservation across alternate optimal solutions is crucial because it determines whether the HFB is a robust, invariant feature of the network or merely an artifact of a single solution selected by the FBA algorithm. Studies show HFB conservation varies by organism; it is largely conserved across alternate optima in E. coli but only moderately conserved in S. cerevisiae [8]. This variability underscores the need for careful analysis.

2. How do alternate optimal and near-optimal solutions affect the HFB?

- Alternate Optimal Solutions: These are flux distributions with the same optimal objective value (e.g., maximal growth rate). The HFB derived from one optimal solution can vary in other optimal solutions. Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) is a key technique to identify reactions guaranteed to be in the HFB across all alternate optima [8].

- Near-Optimal Solutions: These are flux distributions with a sub-optimal but biologically acceptable objective value. The HFB shows significantly greater variation across near-optima compared to alternate optima, revealing a high degree of redundancy and "flux plasticity" in metabolic networks [8]. This plasticity is a key mechanism for robustness.

3. What computational methods can I use to analyze alternate optima and the HFB?

- Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): This is a fundamental method. FVA determines the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction across all alternate optimal solutions without enumerating them all. Reactions with minimal flux variability are strong candidates for a conserved HFB [8].

- Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP): You can use MILP to explicitly enumerate a set of distinct alternate optimal solutions. A recursive MILP algorithm can systematically generate new solutions by forcing at least one previously high-flux reaction to be removed in subsequent iterations [8].

- Feature Barcoding Analysis (FBA - a different tool): For single-cell RNA-Seq experiments that include feature barcoding (e.g., for CRISPR perturbations or cell hashing), the "FBA" software package is a flexible tool for quantification and demultiplexing [13]. This is distinct from Flux Balance Analysis but can provide data on cellular heterogeneity that informs metabolic models.

4. Which reactions are most likely to be part of a conserved HFB?

Research indicates that the set of HFB reactions conserved across alternate near-optima has a large overlap with essential reactions [8]. Furthermore, reactions that are both the uniquely consuming (UC) and uniquely producing (UP) reaction for a metabolite are strong candidates for inclusion in a conserved backbone [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent HFB Identification

Symptoms: The calculated HFB changes drastically when using different FBA solvers or when the model is perturbed slightly, leading to unreliable biological conclusions.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perform Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | Identifies reactions with invariant fluxes across all alternate optima. A conserved HFB should be rich in these low-variability reactions [8]. |

| 2 | Check for Essential Reactions | Compare your HFB with a list of model-specific essential reactions (determined via in-silico knockouts). A robust HFB should have significant overlap [8]. |

| 3 | Analyze Near-Optimal Space | Instead of focusing only on the absolute optimum, calculate HFBs from a set of near-optimal flux distributions. The core conserved across these is a more robust indicator of critical network structure [8]. |

| 4 | Validate with Experimental Data | Where possible, correlate the predicted conserved HFB with experimental data (e.g., gene essentiality or reaction flux measurements) to confirm its biological relevance. |

Problem: Handling Computational Complexity

Symptoms: The analysis is too slow, or it is computationally infeasible to enumerate all alternate optimal solutions for a large, genome-scale model.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prioritize FVA | Use FVA instead of full enumeration. FVA efficiently characterizes the solution space by providing flux ranges without listing all solutions [8]. | |

| 2 | Use Sampling | If possible, employ metabolic flux sampling techniques to statistically explore the space of optimal and near-optimal solutions and build a probabilistic HFB. | A representative profile of the solution space is obtained. |

| 3 | Focus on a Subsystem | Restrict your HFB analysis to a subsystem of primary interest (e.g., central carbon metabolism) to reduce problem size. | A tractable analysis on a biologically relevant part of the network. |

Key Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to Identify a Conserved HFB

Objective: To find the set of reactions that consistently carry high flux and form a stable HFB across all alternate optimal flux distributions [8].

Methodology:

- Define the Metabolic Model and Medium: Start with a stoichiometric matrix (S) and define the environmental conditions (exchange reaction bounds) [8] [12].

- Solve the Base FBA Problem: Maximize for the objective (e.g., biomass). Record the optimal objective value, Z₀ [8].

- Perform Flux Variability Analysis: For each reaction (i) in the model, solve two Linear Programming (LP) problems:

- Minimize vi, subject to: S∙v = 0, α ≤ v ≤ β, and c(^T)v = Z₀.

- Maximize vi, subject to the same constraints. This yields the flux range [vimin, vimax] for each reaction across alternate optima [8].

- Identify the Conserved HFB:

- Calculate the HFB from a reference optimal flux distribution.

- The conserved HFB reactions are those in the reference HFB that also have consistently high flux values (e.g., |vimin| and |vimax| are both above a high-flux threshold) across the ranges computed by FVA.

Protocol 2: Analyzing HFB Conservation in Near-Optimal Space

Objective: To understand the redundancy and plasticity of metabolic networks by examining HFB variation in sub-optimal states [8].

Methodology:

- Generate Near-Optimal Flux Distributions: Using MILP or other techniques, generate a set of flux distributions where the objective function value is within a small percentage (δ) of the optimum (e.g., c(^T)v ≥ (1-δ)Z₀) [8].

- Calculate HFB for Each Distribution: Compute the HFB for each individual near-optimal flux distribution in the set.

- Determine the Conserved Core: Find the intersection of all HFBs from step 2. This core set of reactions is the conserved HFB across the near-optimal space.

- Correlate with Biological Features: Compare this conserved core to known essential reactions and uniquely consuming/producing (UC/UP) reactions [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and resources essential for conducting HFB and alternate optima research.

| Item | Function in Research | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Model | The foundational network structure for any FBA [12]. | Organism-specific (e.g., E. coli iJO1366, S. cerevisiae iMM904). Must include reaction stoichiometries, bounds, and a biomass objective function. |

| Linear Programming (LP) Solver | Computes the optimal flux distribution in the base FBA problem [8]. | Commercial (e.g., Gurobi, CPLEX) or open-source (e.g., GLPK) solvers integrated via modeling platforms like COBRApy. |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | Determines the range of possible fluxes for each reaction across alternate optima [8]. | A standard function in the COBRA Toolbox. Critical for assessing the uniqueness of a flux solution. |

| Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) Solver | Enumerates distinct alternate optimal solutions [8]. | Used in recursive algorithms to generate new solutions by excluding parts of previous ones. More computationally intensive than LP. |

| Feature Barcoding Analysis (FBA) Package | For single-cell RNA-Seq data with feature barcodes (e.g., CITE-seq, CRISPR screens) [13]. | Note: This is distinct from Flux Balance Analysis. It performs quality control, quantification, and demultiplexing. Available on PyPi. |

The tables below summarize key quantitative findings from research on HFB conservation.

Table 1: HFB Conservation Across Organisms and Solution Types

| Organism | Solution Type | Degree of HFB Conservation | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Alternate Optima | Largely Conserved | The HFB from one optimum is largely maintained in other optimal solutions [8]. |

| S. cerevisiae | Alternate Optima | Moderately Conserved | The HFB shows only moderate conservation across different optimal solutions [8]. |

| E. coli & S. cerevisiae | Near-Optima | Large Variation | The HFB is highly variable, indicating significant flux plasticity and network redundancy [8]. |

Table 2: Performance Metrics from an Example FBA Application

The following data is derived from an example analysis of a single-cell CRISPR screening dataset using the feature barcoding "FBA" package, demonstrating typical outputs from such analytical tools [13].

| Metric | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Read Pairs with Valid Barcodes | ~65% | Indicates good library quality for the CRISPR screen [13]. |

| Average UMIs Detected Per Cell | ~477 | Reflects the sequencing depth and efficiency of perturbation detection [13]. |

| Cells with ≥1 Feature Barcode | ~90% | Shows successful detection of the CRISPR perturbation in most cells [13]. |

| Cells with >1 sgRNA (Multiplets) | ~10% | Indicates the level of co-occurrence of multiple perturbations, which can complicate analysis [13]. |

Technical Support Center

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Troubleshooting

Q: My FBA model has become infeasible after integrating known flux measurements. How can I resolve this?

A: Infeasibility occurs when known flux values violate steady-state or other constraints. You can resolve this using two primary methods to find minimal corrections to the given flux values [14]:

- Linear Programming (LP) Method: Finds the minimal set of flux value corrections using linear constraints to restore feasibility.

- Quadratic Programming (QP) Method: Finds corrections by minimizing the sum of squared deviations from the original measured values, often providing a more balanced solution.

The workflow below outlines the systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving an infeasible FBA problem.

Q: How do I calculate the growth rate of E. coli on different substrates under varying conditions?

A: You can calculate growth rates by setting up the model with specific boundary conditions and solving the optimization problem. Below is a protocol using the E. coli core model [15]:

- Load the Model: Load the stoichiometric model into your analysis environment (e.g., COBRA Toolbox).

- Set Substrate Uptake: Define the sole carbon source by setting its exchange reaction lower bound to a negative value (e.g., -18.5 mmol/gDW/hr for glucose) while setting other carbon exchange reactions to zero.

- Set Environmental Conditions:

- Aerobic: Set the oxygen exchange reaction (

EX_o2(e)) lower bound to a large negative value (e.g., -1000). - Anaerobic: Set the oxygen exchange reaction lower bound to zero.

- Aerobic: Set the oxygen exchange reaction (

- Set the Objective: Define the biomass reaction (e.g.,

Biomass_Ecoli_core_N(w/GAM)-Nmet2) as the linear objective to maximize. - Run FBA: Solve the linear programming problem using an FBA solver. The optimal objective value is the predicted growth rate.

The table below shows sample results from such an analysis [15]:

| Substrate | Condition | Uptake Rate (mmol/gDW/hr) | Predicted Growth Rate (1/hr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Aerobic | -18.5 | 1.65 |

| Glucose | Anaerobic | -18.5 | 0.47 |

| Succinate | Aerobic | -20.0 | 0.84 |

| Succinate | Anaerobic | -20.0 | 0.00 |

Q: What does it mean if my FBA solution is feasible but the objective value is not unique?

A: This indicates the presence of alternative optimal solutions. Your model has multiple flux distributions that achieve the same optimal objective value (e.g., growth rate). This is common in metabolic networks and highlights the network's redundancy and flexibility. To analyze this further, you can [14]:

- Identify the reactions that are uniquely determined versus those with variability.

- Use techniques like Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to determine the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining the optimal objective.

- Analyze the nullspace of the stoichiometric matrix to understand the degrees of freedom in the system.

Strain Engineering Troubleshooting

Q: I have designed a metabolic strain for chemical production, but the yield is lower than predicted by FBA. What could be wrong?

A: Discrepancies between FBA predictions and real-world yields are common. Please investigate the following areas:

- Model Integrity: Ensure your model accurately reflects the genetic modifications (e.g., gene knock-outs). Verify that the Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules are correctly associated and that the intended reactions are indeed inactive.

- Measurement Fidelity: Re-check the measured uptake and secretion rates you use to constrain the model. Inconsistent measured fluxes are a primary cause of model infeasibility and incorrect predictions [14].

- Regulatory Effects: FBA does not account for transcriptional or enzymatic regulation. The cell may be employing regulatory mechanisms that divert flux away from the desired product, which are not captured in the model.

- Objective Function: Verify that the linear objective (e.g., maximizing biomass or product formation) is biologically relevant under your experimental conditions.

Drug Target Identification Troubleshooting

Q: I have a small molecule that shows a promising phenotypic effect in a cell-based assay. How can I identify its direct protein target?

A: Target identification, or deconvolution, is a major challenge. The following table summarizes the three primary, complementary approaches [16]:

| Approach | Description | Key Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Biochemical Methods | Physically isolating the target protein using the small molecule itself. | Affinity purification, photoaffinity labeling, affinity-based protein profiling |

| Genetic Interaction Methods | Using genetic manipulation to see if changes in a presumed target gene alter the cell's sensitivity to the small molecule. | CRISPR-Cas9, RNAi, resistance mutation mapping |

| Computational Inference Methods | Comparing the small molecule's effects or structure to large databases to generate a target hypothesis. | Gene expression profiling, chemical similarity searching, structural bioinformatics |

The following diagram illustrates how these methods can be integrated into a cohesive workflow for robust target identification.

Q: How can I improve the robustness of my target validation process to avoid late-stage failures?

A: The GOT-IT framework provides recommendations to improve target assessment [17]. Focus on these key areas early in research:

- Target Biology: Comprehensively understand the target's role in the disease and normal physiology, including potential safety issues.

- Druggability: Assess the likelihood of finding a small molecule that can effectively modulate the target.

- Assayability: Ensure you can develop robust assays to measure compound activity against the target.

- Differentiation Potential: Evaluate if modulating the target offers a clear advantage over existing therapies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key reagents and tools used in the experiments and methods cited in this guide.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Immobilized Compound Beads | Solid support for affinity purification; used to pull down binding proteins from cell lysates [16]. |

| Photoaffinity Probes | Small molecules equipped with a photo-reactive crosslinker; used for covalent capture of low-affinity or transient protein targets [16]. |

| Inactive Analog Compound | A structurally similar but inactive molecule; serves as a critical negative control in affinity purification experiments to rule out non-specific binding [16]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Library | A pooled collection of guide RNAs for genome-wide screening; used in genetic interaction methods to identify genes that confer sensitivity/resistance to a compound [16]. |

| Gene Expression Microarray/RNA-Seq Kit | Tools for profiling global gene expression; used in computational inference to generate a "fingerprint" for a compound by comparing it to databases of known drug signatures [16]. |

| Stoichiometric Model (e.g., E. coli core) | A computational representation of a metabolic network; the primary tool for performing FBA and predicting phenotypic outcomes [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: In FBA, what is the difference between an underdetermined and a redundant system? A1: These are two key properties of a metabolic system. An underdetermined system has more unknown reaction rates than independent equations, meaning not all fluxes can be uniquely calculated. A redundant system has linear dependencies between the metabolite balances (rows in the stoichiometric matrix), which can lead to inconsistencies when integrating measured fluxes [14].

Q2: Why might a target identified by affinity purification still not be the correct target responsible for the phenotypic effect? A2: A compound can bind to multiple proteins. Affinity purification might identify the most abundant or highest-affinity binder, not the functionally relevant one. This is why using complementary approaches (genetic, computational) is critical for confirmation [16]. Furthermore, the immobilization process can sometimes alter the compound's activity, leading to false positives or negatives [16].

Q3: My FBA solution has a unique optimal growth rate, but the flux through many internal reactions is not unique. Is this a problem? A3: This is a normal and expected occurrence called alternative optimal solutions. It means the cell has multiple metabolic pathways to achieve the same maximum growth yield. This reflects the redundancy and robustness of metabolic networks. To analyze this, use Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to find the range of possible fluxes for each reaction.

Advanced Frameworks and Algorithms for Solution Space Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) and why is it necessary after performing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)?

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is an optimization-based technique that predicts the steady-state fluxes of reactions in a metabolic network at the optimum of a biological objective, such as biomass production [18]. However, the FBA solution is typically not unique; the problem is often degenerate, meaning multiple flux distributions can achieve the same optimal objective value [19]. Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) is a method to determine the range of possible reaction fluxes that still satisfy, within a defined optimality factor, the original FBA problem. It quantifies the feasible ranges of all reaction fluxes, thereby analyzing the flexibility and potential redundancy within the metabolic network [19].

2. My FVA results show a reaction with a range of zero. What does this mean, and how can I investigate further?

A reaction with a minimum and maximum flux of zero is considered a blocked reaction. This means the reaction cannot carry any flux under the given model and environmental conditions. To investigate, you can use the find_blocked_reactions function in COBRApy [20]. First, ensure your exchange reactions (which define nutrient availability) are correctly set. Opening all exchange reactions to high flux ranges (using the open_exchanges parameter) can help determine if the blockage is due to constrained nutrient uptake [20].

3. How does the choice of fraction_of_optimum parameter affect my FVA results?

The fraction_of_optimum parameter (often denoted as μ) requires that the objective value in the FVA constraints is at least a specified fraction (e.g., 0.90 for 90%) of the maximum objective value, Z_0, found by FBA [19] [20]. A value of 1.0 enforces exact optimality, meaning FVA will only explore flux distributions that achieve the absolute maximum growth rate or biomass yield. A value less than 1.0 allows for sub-optimal solutions, which can reveal a wider range of possible fluxes for reactions that are not directly coupled to the objective. This is useful for identifying alternate optimal and sub-optimal pathways.

4. What is the computational cost of FVA, and are there ways to make it faster?

The classic FVA approach requires solving 2n + 1 linear programs (LPs), where n is the number of reactions [19]. This can be computationally expensive for large, genome-scale models. Strategies to improve speed include:

- Algorithmic Improvements: Newer algorithms can reduce the number of LPs that need to be solved by inspecting intermediate solutions to see if flux bounds have already been reached, thus skipping redundant optimizations [19].

- Parallel Processing: COBRApy's

flux_variability_analysisfunction supports theprocessesparameter, which allows the computation to be distributed across multiple CPU cores, significantly reducing real-world computation time [20]. - Loopless FVA: While sometimes biologically necessary, requesting loopless solutions (via the

looplessparameter) leads to a significant increase in computation time (e.g., by a factor of 100) and should only be used when essential [20].

5. What is the difference between pfba_factor and fraction_of_optimum?

These parameters constrain the FVA problem in different ways:

fraction_of_optimum: Constraints the objective function value (e.g., growth) to be at least a fraction of its maximum [20].pfba_factor: Constraints the total sum of absolute fluxes in the network. It requires that the sum must not be larger than a given factor (e.g., 1.1) times the smallest possible sum found by parsimonious FBA (pFBA). This can lead to more realistic predictions by minimizing the total metabolic "cost" [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Infeasible FVA Problems

Problem: The FVA simulation returns an error stating the model is infeasible after adding the optimality constraint.

Solution:

- Verify Initial FBA: First, ensure your base FBA problem is feasible and returns a non-zero objective value (

Z_0). An infeasible FBA indicates a fundamental problem with the model or constraints. - Check Reaction Bounds: Review the lower and upper bounds (

lower_bound,upper_bound) for all reactions, especially exchange reactions, to ensure they allow a feasible solution. - Adjust

fraction_of_optimum: If yourfraction_of_optimumis set to 1.0, try a slightly lower value (e.g., 0.99). Numerical instabilities in the LP solver can sometimes make the exact optimal solution space infeasible.

Issue 2: Interpreting Essential Reactions and Genes

Problem: You need to identify which reactions or genes are critical for your objective function (e.g., growth).

Solution: Use the dedicated functions in COBRApy to perform essentiality analysis.

- Essential Reactions: A reaction is essential if setting its flux to zero reduces the objective function below a defined viability

threshold. Usefind_essential_reactions(model, threshold=0.01)to find them [20]. - Essential Genes: A gene is essential if knocking out all reactions dependent on that gene reduces the objective below the threshold. Use

find_essential_genes(model, threshold=0.01)[20]. By default, a threshold of 1% of the maximum objective is often used.

Issue 3: Implementing FVA in COBRApy

Problem: How to correctly set up and run an FVA simulation using the COBRApy toolbox.

Solution: Follow this detailed protocol and refer to the code example below.

Protocol: Flux Variability Analysis with COBRApy

- Model Loading: Load your model in Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) format.

- FBA Pre-solve: It is good practice to first solve an FBA to verify the model state and obtain the maximum objective value.

- Parameter Configuration:

reaction_list: Specify a list of reactions to analyze. IfNone, FVA runs on all reactions.fraction_of_optimum: Set the desired fraction (default is 1.0 for exact optimality).loopless: Set toTrueor a specific method (e.g., "fastSNP") to enforce loopless solutions. Use with caution due to high computational cost.pfba_factor: Optionally provide a factor (e.g., 1.1) to constrain the total flux sum.processes: Set the number of CPU cores for parallel processing.

- Execution: Call the

flux_variability_analysisfunction. - Result Analysis: The result is a DataFrame with columns for the

maximumandminimumflux for each reaction.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Quantitative Data from FVA

The primary output of FVA is a table of minimum and maximum fluxes. The following table summarizes hypothetical FVA results for a core metabolic model, illustrating key concepts like blocked, essential, and flexible reactions.

Table 1: Example FVA Results for a Core Metabolic Network (Glucose Minimal Media)

| Reaction ID | Reaction Name | Minimum Flux | Maximum Flux | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATPM | Maintenance ATPase | 8.5 | 8.5 | Fixed flux |

| PFK | Phosphofructokinase | 10.2 | 10.2 | Fixed flux |

| GND | Phosphogluconate Dehydrogenase | 0.0 | 0.0 | Blocked reaction |

| BIOMASS | Biomass Reaction | 0.9 | 1.0 | Flexible flux (depends on fraction_of_optimum) |

| PGI | Phosphoglucose Isomerase | -5.1 | 5.1 | Reversible reaction |

| AKGDH | Oxoglutarate Dehydrogenase | 3.5 | 3.5 | Essential reaction |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points in a standard Flux Variability Analysis.

Relationship between FBA and FVA

This diagram illustrates how FBA and FVA work together to characterize the solution space of a metabolic network, especially in the context of dealing with alternative optimal solutions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Software for FVA

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| COBRApy | A Python package for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) of metabolic models. It contains the flux_variability_analysis function. |

Primary software tool for implementation [20]. |

| Metabolic Network Model | A computational reconstruction of an organism's metabolism, typically containing stoichiometric matrix (S), reaction bounds, and a biomass objective. | Models are often available in SBML format from repositories [18]. |

| Linear Programming (LP) Solver | An optimization engine used to solve the FBA and FVA linear programs. | COBRApy often uses the GNU Linear Programming Kit (GLPK) by default, but commercial solvers like CPLEX or Gurobi can be faster for large models. |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | A mathematical matrix representing the metabolic network where rows are metabolites and columns are reactions. Entries are stoichiometric coefficients [18]. | Core data structure for any FBA/FVA calculation. |

| Objective Function (c) | A vector of coefficients defining the biological objective to be optimized, such as biomass production [19] [18]. | Defined in the model. For growth, this is often the biomass reaction. |

| Flux Bounds (lb, ub) | Vectors defining the lower and upper limits for the flux of each reaction in the network [19]. | Critical constraints that define the feasible solution space. |

Foundational Concepts: FBA and MPA

What is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and what are its core limitations?

Answer: Flux Balance Analysis is a constraint-based computational method used to predict the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network. It analyzes biochemical networks by applying mass balance constraints and optimization principles without requiring detailed kinetic parameters [18].

Core FBA Components:

- Stoichiometric Matrix (S): A mathematical representation where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions, with entries showing stoichiometric coefficients [18].

- Constraints: The system is constrained by mass balance (Sv = 0 at steady state) and flux bounds that define minimum and maximum reaction rates [18].

- Objective Function: A linear combination of fluxes (Z = cᵀv) that is maximized or minimized, such as biomass production or ATP synthesis [18].

Key Limitations: Traditional FBA faces challenges in capturing flux variations under different conditions and depends heavily on selecting an appropriate objective function. It may not fully account for metabolic flexibility or regulatory constraints without extensions [2].

What is Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) and how does it complement FBA?

Answer: Metabolic Pathway Analysis comprises methods for functionally interpreting metabolic networks by examining pathway structures, connectivity, and topological properties. It helps unravel network complexity using graph theory concepts [21] [22].

MPA Methodologies:

- Topological Pathway Analysis (TPA): Converts metabolic networks to graphs and scores pathways using various measures, considering metabolite connectivity and betweenness centrality [21].

- Betweenness Centrality: A key metric measuring how often a node appears on shortest paths between other nodes, calculated as BC(v) = Σ(σₐₑ(v)/σₐₑ)/[(N-1)(N-2)] where σₐₑ is the total number of shortest paths and σₐₑ(v) is the subset passing through node v [21].

- Mass Flow Graph (MFG): A directed, weighted graph representation of metabolic fluxes between reactions derived from FBA solutions [2].

MPA complements FBA by providing pathway-centric insights, identifying critical connections, and enhancing interpretability of dense metabolic networks through topological examination [2].

Integration Framework and Implementation

What is the TIObjFind framework and how does it integrate FBA with MPA?

Answer: TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find) is a novel framework that systematically integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis with Flux Balance Analysis to analyze adaptive shifts in cellular responses and identify appropriate objective functions [2].

Table: Key Components of the TIObjFind Framework

| Component | Function | Implementation in TIObjFind |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) | Quantifies each reaction's contribution to objective function | Weights derived through optimization to align with experimental data |

| Mass Flow Graph (MFG) | Represents metabolic fluxes as a directed, weighted graph | Constructed from FBA solutions to visualize flux distributions |

| Minimum Cut Sets (MCs) | Identifies essential pathways for product formation | Applied via max-flow min-cut algorithms (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) |

| Pathway-Specific Weighting | Distributes importance across metabolic pathways | Uses Coefficients of Importance to prioritize critical pathways |

Implementation Workflow:

- Optimization Problem Formulation: Reformulates objective function selection as an optimization problem minimizing differences between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal [2].

- Graph Construction: Maps FBA solutions onto a Mass Flow Graph for pathway-based interpretation of metabolic flux distributions [2].

- Pathway Extraction: Applies a minimum-cut algorithm to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance as pathway-specific weights [2].

What computational tools and algorithms are used in topology-informed FBA-MPA integration?

Answer: Implementation requires specialized computational tools for optimization, graph analysis, and visualization:

Optimization and Solvers:

- Linear Programming (LP): Used for basic FBA computations, typically implemented with GLPK solver [10].

- Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP): Employed for more complex problems with discrete variables, using SCIP solver [10].

- MATLAB Environment: TIObjFind was implemented in MATLAB with custom code for main analysis [2].

Graph Analysis Algorithms:

- Boykov-Kolmogorov Algorithm: Used for minimum cut set calculations due to superior computational efficiency with near-linear performance across graph sizes [2].

- Ford-Fulkerson and Edmonds-Karp: Alternative algorithms for solving max-flow min-cut problems [2].

Visualization Tools:

- Python with pySankey: Used for result visualization in TIObjFind implementation [2].

- Graph Theory Metrics: Betweenness centrality, connectivity analysis, and pathway impact scores [21].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

How can researchers address alternative optimal solutions in FBA?

Answer: Alternative optimal solutions occur when multiple flux distributions yield the same optimal objective value, which is a fundamental challenge in FBA research [18].

Solutions and Methodologies:

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA):

- Purpose: Identifies range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal objective value.

- Implementation: Uses FBA to maximize and minimize every reaction in the network to determine flux ranges [18].

- Application: Helps identify redundant pathways and reactions with flexible flux capacities.

TIObjFind's Coefficient of Importance Approach:

- Mechanism: Introduces Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to the objective function [2].

- Advantage: Distributes weights across multiple reactions rather than assuming a single objective, reducing dependence on one optimal solution.

- Implementation: Uses optimization that minimizes squared deviations from experimental data while maximizing a weighted sum of fluxes [2].

Regulatory Constraints Integration:

What are common pitfalls in metabolic pathway analysis and how to avoid them?

Answer: Based on analysis of current practices in metabolomics research, several common pitfalls affect the reliability of MPA results [21] [23].

Table: Common MPA Pitfalls and Solutions

| Pitfall | Impact | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Background Metabolome | Over-optimistic P-values, false positives | Always upload reference metabolome (all identified metabolites in study) as background set [23] |

| Hub Metabolite Over-emphasis | Central compounds dominate results, masking pathway-specific signals | Implement hub penalization schemes to diminish hub compound effects [21] |

| Poor Pathway Definition | Arbitrary pathway boundaries affect interpretation | Use organism-specific pathways when available; acknowledge pathway arbitrariness [21] [23] |

| Ignoring Multiple Testing | Increased false discovery rates | Apply appropriate multiple testing corrections (FDR, Bonferroni) to pathway results [23] |

| Database Selection Bias | Results vary significantly between databases | Report specific database (KEGG, Reactome, Biocyc) with version information [23] |

Additional Recommendations:

- Connectivity Considerations: Evaluate both disconnected (pathway-independent) and connected (full-network) approaches, as each offers different insights [21].

- Non-Human Native Reactions: Include microbiota-related reactions for comprehensive analysis, particularly in environmental or host-microbiome studies [21].

- Transparency in Parameters: Report all analysis parameters, even default values, including P-value cutoffs, database versions, and organisms used for pathway definitions [23].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

What is the detailed protocol for implementing TIObjFind framework?

Answer: The TIObjFind implementation follows a structured three-step process with specific technical requirements [2].

Step 1: Optimization Problem Formulation

- Objective: Minimize difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing inferred metabolic goal.

- Mathematical Formulation: Solve optimization problem that minimizes Σ(vpredicted - vexperimental)² subject to stoichiometric constraints Sv = 0.

- Implementation: Use single-stage Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) formulation of FBA to evaluate candidate objectives.

- Output: Obtain best-fit FBA solutions that explain experimental flux data.

Step 2: Mass Flow Graph Construction

- Input: FBA solutions from Step 1.

- Graph Construction: Represent metabolic fluxes as directed, weighted graph G(V,E) where:

- Nodes (V) represent metabolic reactions

- Edges (E) represent flux relationships with weights corresponding to flux values

- Visualization: Use appropriate graph visualization tools to examine flux distributions.

Step 3: Metabolic Pathway Analysis with Minimum Cut Sets

- Algorithm Selection: Implement Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm for computational efficiency.

- Pathway Identification: Apply minimum cut sets to identify essential pathways between:

- Start reactions (e.g., glucose uptake as primary metabolic input)

- Target reactions (e.g., product secretion)

- Coefficient Calculation: Compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) as pathway-specific weights.

- Validation: Compare predicted fluxes with experimental data and iterate if necessary.

How to validate topology-informed FBA-MPA integration results?

Answer: Validation requires multiple approaches to ensure biological relevance and predictive accuracy:

Quantitative Validation Metrics:

- Prediction Error Calculation: Compute sum of squared deviations between predicted and experimental fluxes [2].

- Coefficient of Importance Stability: Assess consistency of CoIs across different biological conditions or system states [2].

- Pathway Impact Scores: Calculate using betweenness centrality measures: Impact = Σ(BCsignificant)/Σ(BCtotal) where BC represents betweenness centrality [21].

Biological Validation Approaches:

- Case Study Applications: Implement framework on well-characterized systems like Clostridium acetobutylicum fermentation or multi-species IBE systems [2].

- Stage-Specific Analysis: Examine metabolic shifts across different biological stages (e.g., growth phases, environmental perturbations) [2].

- Comparison with Alternate Methods: Benchmark against traditional FBA, rFBA, and other constraint-based methods [2].

Sensitivity Analysis:

- Parameter Variations: Test sensitivity to objective function choices, constraint bounds, and algorithm parameters.

- Topology Robustness: Evaluate results against variations in network structure or pathway definitions.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Topology-Informed FBA-MPA Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB package for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | Primary tool for FBA implementations; supports SBML model format [18] |

| KEGG Database | Reference pathway database for metabolic network reconstruction | Provides generic and organism-specific pathway definitions [21] |

| ModelSEED | Biochemical database for metabolic model construction | Used in KBase for reaction annotation and model reconstruction [10] |

| SCIP Solver | Optimization solver for mixed-integer linear programming | Used for gapfilling and complex optimization problems [10] |

| GLPK Solver | Linear programming solver for basic FBA computations | Faster for pure-linear optimizations [10] |

| Boykov-Kolmogorov Algorithm | Graph algorithm for minimum cut calculations | Preferred for computational efficiency in pathway analysis [2] |

| Python with pySankey | Visualization package for metabolic flux distributions | Used for result visualization in TIObjFind framework [2] |

| MetaboAnalyst | Web-based suite for metabolomics data analysis | Includes pathway analysis tools but requires careful parameter setting [23] |

Implementation Considerations:

- Software Integration: TIObjFind was implemented in MATLAB with graph analysis using MATLAB's maxflow package [2].

- Data Compatibility: Ensure consistency between metabolic models, experimental data formats, and analysis tool requirements.

- Computational Resources: Large-scale metabolic networks may require significant memory and processing capacity, particularly for iterative optimization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary function of the TIObjFind framework? TIObjFind is a data-driven optimization framework that integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to identify context-specific metabolic objective functions for biological systems. It calculates Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to a cellular objective, enhancing the interpretability of complex metabolic networks and aligning model predictions with experimental flux data [2].

Q2: How does TIObjFind address the challenge of alternative optimal solutions in FBA? Standard FBA can produce multiple, equally optimal flux distributions (alternative optimal solutions) for a given objective, making biological interpretation difficult [24]. TIObjFind addresses this by using experimental data to infer a weighted combination of fluxes as the objective, thereby identifying a single, biologically relevant solution from the set of possibilities and reducing prediction errors [2].

Q3: What are the key inputs required to run a TIObjFind analysis? The framework requires two primary inputs:

- A genome-scale metabolic model for the organism, defining the stoichiometry of all known metabolic reactions.

- Experimental flux data (

vjexp), often obtained from techniques like isotopomer analysis, for the conditions being studied [2].

Q4: In which scenarios is TIObjFind particularly useful? TIObjFind is highly valuable for studying systems where metabolism adapts over time or under varying environmental conditions. This includes:

- Microbial fermentations with distinct metabolic phases (e.g., acidogenesis vs. solventogenesis in Clostridium acetobutylicum).

- Multi-species microbial communities, where each species may have different metabolic priorities.

- Any biological system where the assumption of a single, static objective function like biomass maximization fails to match experimental observations [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Alignment Between FBA Predictions and Experimental Data

Problem: The flux distribution predicted by a standard FBA (e.g., maximizing biomass) shows a significant deviation from your experimental flux data.

Solution:

- Action: Apply the TIObjFind framework to infer a more accurate, data-driven objective function.

- Methodology:

- Formulate the TIObjFind optimization problem to minimize the squared difference between predicted fluxes (

v) and experimental data (vjexp) while maximizing a weighted sum of fluxes (cobj · v). - Use the resulting flux distribution to construct a Mass Flow Graph (MFG).

- Apply a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to this graph to identify critical pathways and compute the Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) for reactions.

- Formulate the TIObjFind optimization problem to minimize the squared difference between predicted fluxes (

- Expected Outcome: The CoIs serve as pathway-specific weights, refining the objective function and leading to flux predictions that are in closer agreement with your experimental data [2].

Interpreting Flux Variability and Alternative Optima

Problem: Your FBA model yields a high degree of flux variability, with many alternate optimal solutions, making it difficult to pinpoint the biologically relevant flux state.

Solution:

- Action: Use TIObjFind to resolve redundancies by leveraging experimental data.

- Background: Alternative optimal solutions arise from network redundancies, where different reaction sets can achieve the same objective value [24]. TIObjFind's CoIs quantify the importance of each reaction within these redundant pathways in the context of your specific experimental data.

- Methodology: The framework's topology-informed analysis prioritizes pathways that are not only stoichiometrically feasible but also consistent with the measured extracellular fluxes, effectively selecting one meaningful solution from the multiple alternatives [2].

Handling Errors in a Multi-Species Community Model

Problem: When modeling a multi-species community (e.g., a co-culture for IBE production), the combined model fails to predict the metabolite secretion profiles observed in the lab.

Solution:

- Action: Use TIObjFind to assign stage-specific or species-specific objective functions.

- Methodology:

- Obtain experimental flux data for each key stage of the co-culture process or for each species in isolation if possible.

- Run TIObjFind independently for each stage or species to derive distinct sets of Coefficients of Importance (CoIs).

- Implement these different objective functions in the community model to simulate the shifting metabolic priorities within the system.

- Expected Outcome: The model will more accurately capture the emergent metabolic behavior of the community, such as cross-feeding and division of labor, leading to better predictions of overall product synthesis [2].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing the TIObjFind Framework

This protocol outlines the steps to infer an objective function using the TIObjFind method [2].

I. Prerequisites and Inputs

- Metabolic Model: A genome-scale metabolic reconstruction in a standard format (e.g., SBML).

- Experimental Data: Experimentally measured extracellular flux data (

vjexp), such as substrate uptake rates and product secretion rates.

II. Procedure

- Single-Stage Optimization:

- Set up and solve an optimization problem that minimizes the squared error between FBA-predicted fluxes (

v) and the experimental data (vjexp). - This step identifies a candidate flux distribution (

vj*) that best fits the data under a hypothesized objective.

- Set up and solve an optimization problem that minimizes the squared error between FBA-predicted fluxes (

Mass Flow Graph (MFG) Construction:

- Map the optimized flux distribution (

vj*) onto a directed, weighted graphG(V,E). - Nodes (V): Represent metabolic reactions.

- Edges (E): Represent metabolic flows between reactions, weighted by the flux value.

- Map the optimized flux distribution (

Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) & Minimum Cut:

- Define a start reaction (e.g., glucose uptake,

s) and a target reaction (e.g., product secretion,t). - Apply a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to the MFG to identify the most critical pathways connecting

stot. - The result of this analysis is used to calculate the Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) for the reactions.

- Define a start reaction (e.g., glucose uptake,

III. Output

- A set of Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that define a weighted objective function (

cobj · v). This function can be used in subsequent FBA simulations to better reflect the cell's metabolic state under the tested conditions.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: TIObjFind Framework Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and data resources essential for conducting research with the TIObjFind framework.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for TIObjFind

| Item Name | Function / Description | Relevance to TIObjFind |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [18] | A MATLAB toolbox for performing constraint-based reconstructions and analysis, including FBA. | Provides the foundational computational environment to set up and solve FBA problems, which is a prerequisite for TIObjFind. |

| Genome-Scale Model | A stoichiometric matrix (S) of all metabolic reactions in an organism. | Serves as the core structural input representing the metabolic network to be analyzed. |

| Experimental Flux Data (vjexp) | Quantified rates of uptake, secretion, and/or intracellular fluxes from experiments. | Critical input used to guide the optimization and infer the correct objective function. |

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracers (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose) used in 13C-MFA to determine intracellular fluxes. | The gold-standard method for generating accurate experimental flux data (vjexp) for TIObjFind [25]. |