Optimizing Gene Expression to Minimize Metabolic Burden: Strategies for Next-Generation Therapeutics and Bioproduction

Optimizing gene expression levels is a critical challenge in metabolic engineering and therapeutic development, directly impacting product yield, cellular fitness, and treatment efficacy.

Optimizing Gene Expression to Minimize Metabolic Burden: Strategies for Next-Generation Therapeutics and Bioproduction

Abstract

Optimizing gene expression levels is a critical challenge in metabolic engineering and therapeutic development, directly impacting product yield, cellular fitness, and treatment efficacy. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to minimize metabolic burden for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles of metabolic burden in engineered systems, detail advanced methodological approaches including orthogonal control systems and combinatorial optimization, present troubleshooting frameworks for pathway balancing, and review validation techniques through compelling case studies in both biomanufacturing and clinical gene therapies. The synthesis of these domains highlights how precise expression control enables breakthroughs in producing high-value chemicals and developing personalized treatments for metabolic disorders.

Understanding Metabolic Burden: The Foundation of Efficient Cellular Engineering

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Metabolic Burden

FAQ 1: My bacterial growth rate has plummeted after introducing a recombinant plasmid. What is the primary cause and how can I address it?

A significant drop in growth rate is a classic symptom of metabolic burden, primarily caused by resource competition between your engineered construct and the host's native genes. This burden stems from the consumption of finite cellular resources, including ribosomes, tRNAs, amino acids, and energy [1] [2] [3].

- Confirm the Cause: Measure the growth rate (optical density) and the expression of a constitutive genomic fluorescent reporter, if available. A simultaneous decrease in both confirms resource-based burden [4].

- Immediate Mitigation Strategies:

- Weaken Induction: Reduce the strength or duration of induction for your gene of interest [2] [3].

- Optimize Codon Usage: Re-synthesize your gene to use codons that match the host's tRNA pool, but avoid extreme over-optimization, which can be detrimental [5].

- Switch the Vector: Use a low-copy-number plasmid to decrease the total number of transcription templates [4].

FAQ 2: My protein yield is low despite high initial expression. What might be happening?

Rapid, high-level expression can trigger stress responses that negatively impact long-term yield. This often results from the accumulation of misfolded proteins or the depletion of specific charged tRNAs [1] [3].

- Investigate and Solve:

- Induction Timing: Avoid induction at the time of inoculation. Instead, induce during the mid-log phase (e.g., OD600 ~0.6). This allows the cells to establish a robust metabolic state before burden is applied, leading to more stable production [3].

- Temperature Shift: Lower the incubation temperature post-induction to slow down translation and facilitate proper protein folding.

- Analyze Codon Usage: Check for clusters of rare codons in your sequence that may cause ribosomal stalling and translation errors, leading to misfolded proteins and activation of the heat shock response [1] [5].

FAQ 3: How can I detect metabolic burden before it severely impacts my production run?

Beyond growth rate, specific transcriptional biomarkers can provide an early warning system for load stress.

- Implement a Biosensor: Machine learning analysis of transcriptomic data has identified key biomarker genes for load stress in E. coli. Incorporating promoters for genes like csrA, yciF, or iscR upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) can create a real-time burden sensor [6]. An increase in reporter signal indicates the activation of stress responses, allowing for proactive intervention.

FAQ 4: I need high expression of a multi-gene pathway. How can I balance flux without overburdening the cell?

Balancing expression across multiple genes is crucial to prevent bottlenecks and minimize burden.

- Employ Combinatorial Optimization: Use advanced tools like GEMbLeR (Gene Expression Modification by LoxPsym-Cre Recombination). This method uses Cre recombinase to shuffle a library of promoters and terminators integrated at the genomic loci of your pathway genes. A single round of transformation and selection can generate a vast library of strains, each with unique expression profiles for all genes, allowing you to select the optimal combination that maximizes pathway flux and product titer [7].

- Fine-tune with Gene Attenuation: Instead of complete knockouts, use CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) or tunable promoters to precisely downregulate (attenuate) competing native genes or to balance the levels of pathway enzymes. This provides more granular control than all-or-nothing approaches [8].

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Quantifying Metabolic Burden Using a Genomic Fluorescent Reporter

This method allows for direct, real-time measurement of the burden imposed by a plasmid on the host's transcriptional and translational machinery [4].

Strain Engineering:

- Integrate a single copy of a reporter gene (e.g.,

gfp-lva) into the host genome under a constitutive promoter. The LVA tag ensures rapid protein degradation for dynamic measurement. - The control strain carries only the genomic GFP. The test strain is the same integrant strain transformed with your plasmid of interest.

- Integrate a single copy of a reporter gene (e.g.,

Culture and Measurement:

- Inoculate both control and test strains in duplicate and grow in a microplate reader.

- Measure Optical Density (OD600) and Fluorescence continuously throughout the growth cycle.

Data Analysis:

- The reduction in GFP fluorescence per unit of OD600 in the test strain compared to the control is a direct metric of the metabolic burden. This is a more sensitive measure than growth rate alone [4].

Protocol 2: Proteomic Analysis of Burden-Induced Stress Responses

This protocol provides a system-wide view of how recombinant protein production perturbs host cell physiology [3].

Experimental Design:

- Strains: Use two host strains (e.g., M15 and DH5α) to compare host-specific responses.

- Conditions: Culture each strain in defined (M9) and complex (LB) media.

- Induction: Induce protein expression at both early-log (OD600 ~0.1) and mid-log (OD600 ~0.6) phases.

Sample Processing:

- Harvest cells at mid-log and late-log phases.

- Lyse cells and extract total protein.

- Perform tryptic digestion and analyze peptides via LC-MS/MS.

- Use Label-Free Quantification (LFQ) to compare protein abundance across samples.

Data Interpretation:

- Identify significant changes in proteins involved in transcription, translation, protein folding, and sigma factors.

- Correlate these changes with growth data and product yield to identify key bottlenecks.

The table below summarizes quantitative data from a study expressing Acyl-ACP reductase (AAR) in different E. coli hosts, demonstrating how strain and induction time critically impact the outcome [3].

Table 1: Impact of Host Strain and Induction Time on Metabolic Burden and Protein Yield

| Host Strain | Growth Medium | Induction Point | Max Specific Growth Rate (μmax, h⁻¹) | Dry Cell Weight (g/L) | Recombinant Protein Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli M15 | Defined (M9) | Early-Log | 0.15 | 7.5 | High initially, diminishes by late phase |

| E. coli M15 | Defined (M9) | Mid-Log | 0.23 | 8.5 | Retained into late growth phase |

| E. coli M15 | Complex (LB) | Early-Log | 0.45 | 4.5 | High initially, diminishes by late phase |

| E. coli M15 | Complex (LB) | Mid-Log | 0.50 | 5.0 | Retained into late growth phase |

| E. coli DH5α | Defined (M9) | Early-Log | 0.20 | 6.5 | High initially, diminishes by late phase |

| E. coli DH5α | Defined (M9) | Mid-Log | 0.30 | 7.5 | Retained into late growth phase |

Protocol 3: Optimizing Codon Usage to Alleviate Burden

This strategy focuses on improving translational efficiency to free up limited resources [5].

Gene Design:

- Synthesize your gene of interest with varying levels of codon optimization (e.g., 10%, 50%, 75%, 90% optimal codons).

- Clone these variants into a standard expression vector with a tunable RBS.

Burden Assessment:

- Express each variant in your host and measure the growth rate and protein yield (e.g., via fluorescence).

- Plot the relationship between yield and growth rate inhibition for each variant.

Identification of Optimal Sequence:

- The goal is to identify the variant that delivers the highest protein yield with the smallest negative impact on growth. Note that 100% optimization is not always ideal and can create a new type of burden by skewing the demand for specific tRNAs [5].

Table 2: Relationship Between Codon Optimization, Protein Yield, and Cellular Burden

| Codon Optimization Level (% Optimal Codons) | Key Mechanism | Impact on Protein Yield | Impact on Cellular Growth & Burden |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (e.g., 10-25%) | High usage of rare codons; ribosomal stalling; tRNA depletion [1] [5] | Low | Severe growth inhibition; high burden |

| Moderate / "Harmonized" (e.g., 50-75%) | Matches host's global codon usage and tRNA abundance [5] | High | Lower burden; optimal balance |

| High / "Over-optimized" (e.g., 90-100%) | Over-consumption of a subset of "optimal" tRNAs; can create new imbalances [5] | Can be high, but may lead to aggregation | Can be burdensome, negating benefits |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Burden Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Burden Analysis | Example & Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Reporter Strain | Quantifies host resource status in real-time. | E. coli with genomic GFP-LVA; single-copy, constitutive expression for accurate burden measurement [4]. |

| Tunable Expression Vectors | Enables control over the level of heterologous expression. | Plasmids with inducible promoters (e.g., T7, T5, L-rhamnose) and a range of copy numbers (high, medium, low) [3]. |

| Codon-Variant Libraries | Systematically tests the effect of translational efficiency on burden. | A set of genes (e.g., sfGFP, mCherry) synthesized with defined levels of codon optimization (10%-90% optimal codons) [5]. |

| Combinatorial Assembly System | Optimizes expression of multiple pathway genes simultaneously. | GEMbLeR system: Uses Cre-LoxPsym recombination to shuffle promoter and terminator modules for multiple genes in vivo [7]. |

| Transcriptional Biomarker Kit | Detects general load stress early via specific gene promoters. | Plasmids with burden-sensitive promoters (e.g., PcsrA, PyciF) fused to a rapid-degradation fluorescent reporter [6]. |

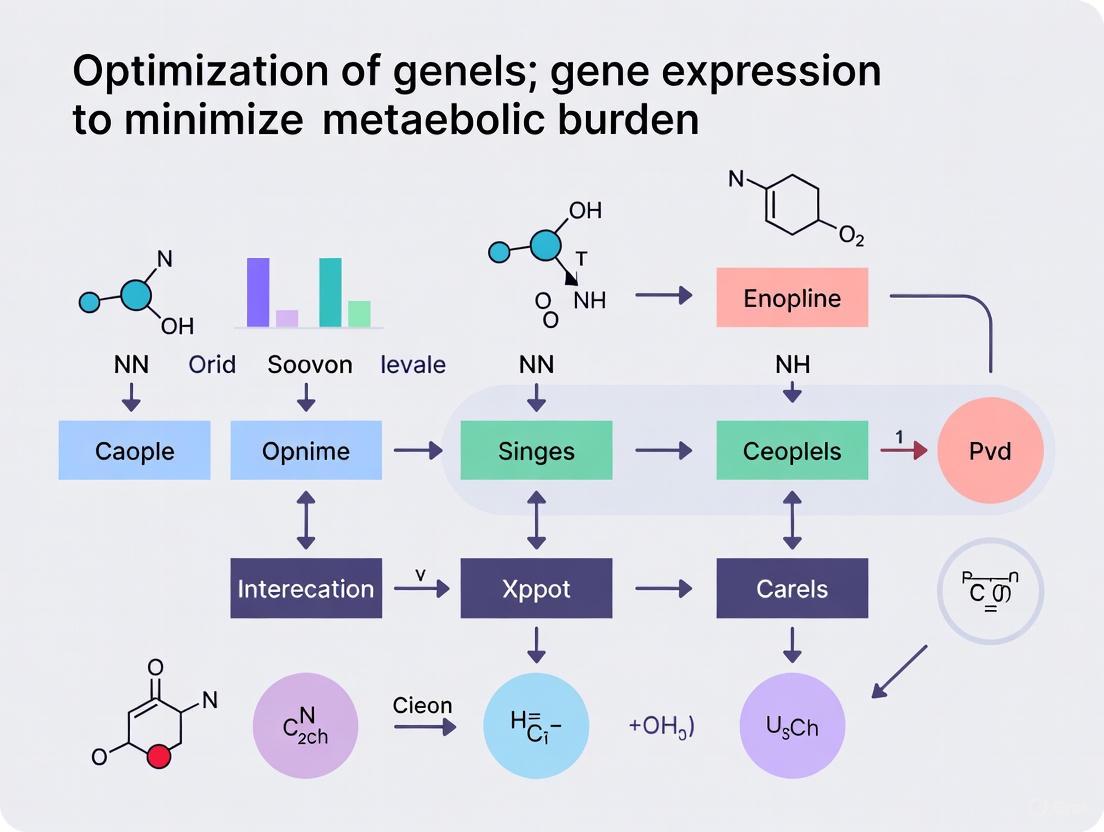

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Cellular Stress Pathways Activated by Metabolic Burden

The following diagram illustrates the key cellular stress responses triggered by the overexpression of heterologous proteins, connecting specific triggers to downstream effects.

Workflow for Systematic Alleviation of Metabolic Burden

This workflow outlines a practical, multi-stage strategy to identify and mitigate metabolic burden in engineered strains.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Addressing Metabolic Flux Bottlenecks

Q: My metabolic pathway is underperforming despite gene overexpression. How can I identify and resolve flux bottlenecks?

A: Flux bottlenecks occur when the expression level of a particular enzyme is insufficient, causing a metabolic intermediate to build up and limiting the final product yield. This is common in iterative pathways where the same set of enzymes acts on multiple, sequentially elongating intermediates.

Diagnosis:

- Method 1: Orthogonal Control Systems. Systematically vary the expression level of each pathway gene independently using an inducible system (e.g., the TriO system). A significant change in product specificity or titer upon changing a single enzyme's expression indicates a bottleneck at that step [9].

- Method 2: Combinatorial Libraries & Design of Experiments (DoE). Create a library of strain variants with different combinations of pathway gene expression levels. Using a statistical DoE approach, such as a Plackett-Burman design, allows you to train a regression model with a minimal number of constructs to identify which genes have the most significant positive or negative impact on product titer [10].

- Method 3: Computational Identification (OMNI). Use computational methods like Optimal Metabolic Network Identification (OMNI) with experimentally measured flux profiles. This bilevel mixed-integer optimization identifies the set of active reactions that results in the best agreement between predicted and measured fluxes, highlighting problematic reactions [11].

Solution:

- Optimize the expression level of the identified bottleneck enzyme. For example, in the shikimate pathway for p-aminobenzoic acid (pABA) production,

aroB(3-dehydroquinate synthase) was pinpointed as a critical bottleneck. Fine-tuning its expression was key to increasing the titer from 2 mg/L to 232.1 mg/L [10].

- Optimize the expression level of the identified bottleneck enzyme. For example, in the shikimate pathway for p-aminobenzoic acid (pABA) production,

Q: How can I prevent toxic intermediate accumulation in my engineered pathway?

A: Accumulation of toxic intermediates can inhibit cell growth, reduce host fitness, and ultimately lower product yields. This is often linked to imbalanced enzyme expression within the pathway.

Diagnosis:

- Observe a sharp decline in cell growth or viability (e.g., a drop in colony-forming units, CFU/mL) following pathway induction, especially when the substrate is present [12].

- Use mathematical modeling that integrates pathway kinetics with population growth dynamics. If model simulations predict population collapse under certain expression conditions, it suggests toxicity exacerbation [12].

Solution:

- Balance Enzyme Expression: Ensure the enzyme that consumes the toxic intermediate is highly expressed relative to the enzyme that produces it. Combinatorial expression libraries are effective for finding the right expression balance to rapidly convert the toxic intermediate [12] [10].

- Consider Host Engineering: Select or engineer a host strain with higher innate tolerance to the toxic compound or its intermediates.

- Modulate Induction: Avoid overly strong, continuous induction. Use milder inducers or lower induction temperatures to slow down the initial flux and prevent a sudden buildup of toxic compounds [13].

Mitigating Reduced Host Fitness and Metabolic Burden

Q: My engineered strain grows very slowly after introducing the metabolic pathway. How can I reduce the metabolic burden?

A: Metabolic burden is the negative impact on host cell metabolism caused by the energy and resource drain of expressing heterologous genes and maintaining plasmids. This manifests as reduced growth rate, lower biomass yield, and decreased protein synthesis capacity.

Diagnosis:

- Compare the growth rate (e.g., OD600 over time) and final biomass yield of the engineered strain to the wild-type host strain or a strain carrying empty plasmids under identical conditions [12] [14].

- Measure the expression of your protein of interest and compare it to expectations. Poor expression can itself be a symptom of burden, as burdened cells cannot support high levels of protein production [13].

Solution:

- Optimize Genetic Parts: Use low-copy number plasmids and avoid overly strong constitutive promoters. Implement inducible systems with tight control to prevent "leaky" expression that burdens the cell during growth phases [13] [10].

- Tune Expression, Don't Maximize: Find the minimum effective expression level for each pathway gene. High-level expression is not always optimal and often comes with a high fitness cost. Use promoter and RBS libraries to find a balance between pathway flux and burden [9] [10].

- Genome Reduction: Consider using a genomically streamlined chassis. Deleting non-essential genomic regions can reduce the genetic load and improve cellular economy, sometimes resulting in higher biomass yield and fitness in a specific niche [14].

- Use Specialized Host Strains: For problematic proteins (e.g., those with rare codons or inherent toxicity), use specialized expression hosts that supply tRNAs for rare codons or contain plasmids like pLysS for tighter control of T7 polymerase systems [13].

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies on overcoming metabolic challenges.

Table 1: Key Experimental Results in Metabolic Pathway Optimization

| Challenge | Host Organism | Method/Strategy | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Bottleneck | Pseudomonas putida | Combinatorial DoE & Linear Modeling | pABA titer increased from 2 mg/L to 232.1 mg/L; identified aroB as key bottleneck [10]. | |

| Flux Bottleneck | Escherichia coli | Orthogonal Control (TriO System) | Achieved 6.3 g/L butyrate, 2.2 g/L butanol, and 4.0 g/L hexanoate from glycerol [9]. | |

| Metabolic Burden & Toxicity | Escherichia coli | Computational Modeling | Model integrated metabolic burden & toxicity exacerbation to predict population dynamics & pathway outcome [12]. | |

| Host Fitness | Escherichia coli | Selection-Driven Genome Reduction (RANDEL) | Generated multiple-deletion strain with 2.5% genome reduction that outcompeted wild-type and showed elevated biomass yield [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying Bottlenecks with a Combinatorial DoE Approach

This protocol is adapted from a study optimizing the shikimate pathway in P. putida [10].

- Define Genetic Variables: Select the genes in the target pathway (e.g., all 9 genes in the shikimate and pABA biosynthesis pathways).

- Choose Expression Levels: For each gene, define a "high" and "low" expression state by selecting corresponding genetic parts:

- Promoters: Choose from a characterized library (e.g., strong promoter JE111111 for high, moderate promoter JE151111 for low).

- RBS: Select a strong RBS (e.g., JER04) for high and a weaker one (e.g., JER10) for low expression.

- Plasmid Backbone: Use a medium-copy plasmid (e.g., pSEVA231) for high and a low-copy plasmid (e.g., pSEVA621) for low expression.

- Design Strain Library: Use a Plackett-Burman statistical design to select a minimal, orthogonal set of strain variants from the full combinatorial library (e.g., 16 strains from a theoretical 512).

- Strain Construction & Screening: Build the selected strains and measure the product titer (e.g., pABA) for each.

- Data Analysis & Modeling: Input the product titer data into a linear regression model. Perform ANOVA to identify which genes have a statistically significant (positive or negative) effect on production.

- Validation & Iteration: Construct new strains predicted by the model to have higher titers and validate experimentally.

Protocol 2: Implementing Orthogonal Expression Control

This protocol is based on the use of the TriO system for iterative pathways in E. coli [9].

- System Design: Employ a plasmid-based inducible system (TriO) that allows for independent, orthogonal control of three pathway genes simultaneously.

- Plug-and-Play Assembly: Use standardized genetic parts to effortlessly construct TriO vectors with different enzyme combinations and inducible promoters.

- Expression Titration: For each pathway variant, systematically vary the concentration of the inducers to scan a wide range of relative expression levels for the involved enzymes.

- Phenotypic Screening: Measure the output of the pathway, specifically noting changes in product specificity (shifts between different products) and titer.

- Identification: Correlate expression levels with performance. An enzyme whose expression level drastically shifts product specificity is a key control node and a potential bottleneck.

- Scale-Up: Take the best-performing strain and optimize production in a bioreactor.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Shikimate Pathway Engineering for pABA

Troubleshooting Metabolic Burden & Toxicity

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Inducible Systems (e.g., TriO) | Independent, parallel control of multiple gene expression levels to identify and resolve flux bottlenecks in iterative pathways [9]. | Enables high-throughput, plug-and-play strain construction without complex cloning. |

| Characterized Promoter & RBS Libraries | A set of genetic parts with known and varying strengths to systematically modulate gene expression [10]. | Crucial for implementing DoE approaches; parts should be pre-characterized in your host organism. |

| Plasmid Vectors with Different Origins of Replication | Vectors with high, medium, and low copy numbers to control gene dosage and reduce metabolic burden [10]. | Low-copy plasmids are often better for balancing burden and pathway performance. |

| Specialized Expression Hosts | Engineered host strains (e.g., supplying rare tRNAs, containing pLysS for tighter T7 control) for expressing difficult proteins [13]. | Helps address issues like codon bias and protein toxicity, which contribute to metabolic burden. |

| Counterselection Systems (e.g., dP-hsvTK) | Powerful selection method to efficiently eliminate cells that have not undergone a desired genetic modification, used in genome streamlining [14]. | Essential for efficient genome editing and reduction strategies with low escape rates. |

| Computational Modeling Software | To build kinetic models that simulate combined effects of metabolic burden and toxicity on population growth and pathway dynamics [12]. | Provides a holistic in silico tool for predicting system behavior before costly experiments. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Product Titer in Microbial Bioproduction

Problem: Low yield of the target metabolite or recombinant protein in your microbial cell factory.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Metabolic Burden | Proteomic analysis to assess ribosomal and stress protein levels; monitor growth rate post-induction [3]. | Implement dynamic induction control; switch to a weaker promoter; use gene attenuation (e.g., CRISPRi) instead of knockout [8] [15]. |

| Inefficient Metabolic Flux | Measure accumulation of metabolic intermediates via HPLC or LC-MS; analyze gene expression of key pathway enzymes. | Attenuate competing metabolic pathways using sRNAs or CRISPRi to redirect carbon flux toward the product [8]. |

| Suboptimal Gene Expression Level | Use qPCR to measure mRNA levels and Western blotting to assess protein levels of key enzymes. | Fine-tune expression of rate-limiting enzymes using RBS libraries or promoter engineering rather than simple overexpression [8]. |

| Inadequate Cofactor Regeneration | Measure intracellular NADH/NAD+ ratios and ATP levels using commercial assay kits. | Engineer more efficient energy modules; replace slow enzymes (e.g., use metal-dependent FDHs with higher kcat) [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Proteomic Analysis for Burden Assessment

- Culture Samples: Grow recombinant and control (parental) strains in appropriate media. Induce recombinant protein expression at both early-log (OD600 ~0.1) and mid-log (OD600 ~0.6) phases [3].

- Harvest Cells: Collect cell pellets at mid-log (OD600 ~0.8) and late-log (12 hours post-inoculation) phases by centrifugation.

- Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction: Lyse cells using a buffer compatible with downstream analysis (e.g., RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors).

- Protein Quantification and Separation: Quantify total protein. Separate 50 µg of protein extract by SDS-PAGE [3].

- Analysis: Use label-free quantification (LFQ) proteomics to compare recombinant and control cells. Focus on changes in ribosomal proteins, stress response proteins, and central metabolism enzymes [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Recombinant Protein Expression

Problem: Low yield or instability of a recombinant protein, especially an Intrinsically Disordered Protein (IDP).

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Instability/ Degradation | Analyze cell lysates by SDS-PAGE at multiple time points post-induction; check for smaller degradation fragments [17]. | Add stabilizing tags (e.g., MBP, GST); lower growth temperature post-induction; use protease-deficient E. coli strains [17]. |

| Codon Usage Bias | Check the codon adaptation index (CAI) of your gene sequence for the expression host. | Re-synthesize the gene with host-optimized codons; use E. coli strains engineered with plasmids encoding rare tRNAs (e.g., Rosetta) [17]. |

| Toxicity to Host Cell | Monitor growth curve of expression strain compared to empty vector control; look for growth arrest upon induction. | Use a tighter expression system (e.g., pBAD with arabinose induction); decrease inducer concentration; induce later in growth phase (mid-log) [3] [17]. |

| Low Yield in Minimal Media (for isotope labeling) | Compare protein yield in rich vs. minimal media. | Use labeled rich media or supplement minimal media (e.g., M9) with a small percentage (5-10%) of labeled rich media [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: High-Yield Isotopic Labeling for NMR

- Pre-culture: Grow expression strain in rich medium (e.g., LB) to high cell density.

- Cell Transfer: Pellet cells via centrifugation and resuspend in labeled minimal medium (e.g., M9 with 15NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen source).

- Metabolic Clearance: Incubate the culture for 1 hour with shaking to allow unlabeled proteins and metabolites to be cleared.

- Induction: Induce protein expression with the appropriate agent (e.g., IPTG) and continue incubation for the optimal duration [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Principles

Q1: What is gene attenuation and why is it preferable to gene knockout in metabolic engineering? Gene attenuation refers to the partial reduction of a gene's expression or function, allowing the gene to retain some activity level while considerably lowering its overall effect [8]. It is often preferable to a complete knockout because it allows for precise control of enzyme activity within metabolic pathways. This is crucial at pathway nodes where a balanced flux is needed. While a full knockout can cause metabolic bottlenecks or the accumulation of unwanted byproducts, attenuation enables an optimized balance, enhancing target metabolite yield and avoiding negative effects on cell growth [8].

Q2: How does recombinant protein production create a "metabolic burden" on the host cell? The metabolic burden is the host cell's stress response to the high energy and resource demand of producing recombinant proteins. Factors contributing to this burden include [3]:

- Plasmid amplification and maintenance.

- Transcription of the recombinant gene.

- Translation and protein folding. This burden drains cellular resources (e.g., nucleotides, amino acids, ATP), leading to observable effects like growth retardation, and can trigger significant global changes in the host's transcriptome and proteome, ultimately undermining production efficiency [3].

Microbial Bioproduction

Q3: What strategies can relieve metabolic burden and improve the robustness of my production strain?

- Dynamic Control: Implement genetic circuits that decouple growth and production phases [15].

- Strain Engineering: Use proteomics to identify burden-related bottlenecks and rationally engineer the host chassis for superior expression [3].

- Process Optimization: Carefully optimize the timing of induction; induction at the mid-log phase often results in a higher growth rate and sustained protein expression compared to early-log induction [3].

- Consortium Engineering: Divide the metabolic pathway between multiple, specialized microbial strains to distribute the burden [15].

Q4: How can I improve the efficiency of a formatotrophic production strain using C1 feedstocks? A key limitation in synthetic formatotrophy (using formate as a carbon source) is often slow energy supply. A proven strategy is to replace a slow, metal-independent formate dehydrogenase (FDH) with a faster, metal-dependent FDH complex (e.g., from C. necator). This enzyme has a much higher turnover rate (kcat) and requires far less proteome allocation, leading to faster growth and higher product titers from formate [16].

Recombinant Protein Expression

Q5: What are the key differences between choosing E. coli strains M15 and DH5⍺ for recombinant protein production? Proteomic studies reveal significant differences between these common host strains [3]:

- E. coli M15: Demonstrates superior expression characteristics for the recombinant protein Acyl-ACP reductase (AAR). It showed significant changes in proteins involved in fatty acid and lipid biosynthesis pathways upon recombinant expression [3].

- E. coli DH5⍺: Showed different metabolic perturbations under the same expression conditions. The optimal host choice depends on the specific protein being expressed, and screening multiple strains is recommended.

Q6: What are the special considerations for expressing and purifying Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs)? IDPs lack a fixed 3D structure and are highly flexible, which leads to unique challenges [17]:

- Protease Sensitivity: IDPs are extremely susceptible to proteolytic cleavage. Use protease-deficient strains and include a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktail during purification.

- Purification: You can often use denaturing conditions (e.g., urea, guanidine HCl) without the concern of refolding the protein later.

- Quantification: Quantifying IDPs can be challenging because they often deviate from standard colorimetric assays (e.g., Bradford assay). Use amino acid analysis for accurate quantification.

Table 1: Comparison of Gene Regulation Strategies in Metabolic Engineering

| Strategy | Description | Key Methods | Impact on Metabolic Burden | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Attenuation | Partial reduction of gene expression or function [8]. | RNAi, CRISPRi, sRNAs, RBS/Promoter tuning [8]. | Lower burden; allows flux balance and maintains cell health [8]. | Fine-tuning competitive pathways, optimizing flux at branch points [8]. |

| Gene Knockout | Complete removal or deactivation of a gene [8]. | CRISPR-Cas9, Homologous recombination [8]. | Can cause high burden, metabolic bottlenecks, or compensatory reactions [8]. | Essential gene function studies, removing non-essential competing pathways [8]. |

| Gene Overexpression | Increasing gene expression to enhance product levels [8]. | Strong promoters, introducing extra gene copies [8]. | High burden; consumes excessive resources (ATP, precursors) [8]. | Boosting the synthesis of a rate-limiting enzyme [8]. |

| Host Strain | Growth Medium | Induction Point | Maximum Specific Growth Rate (µmax, h⁻¹) | Recombinant Protein Expression at Late Growth Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli M15 | Defined (M9) | Early-Log (OD600 ~0.1) | Lower µmax | Expression diminished |

| E. coli M15 | Defined (M9) | Mid-Log (OD600 ~0.6) | Higher µmax | Expression retained |

| E. coli M15 | Complex (LB) | Early-Log (OD600 ~0.1) | Higher µmax (~3x vs. M9) | Varies |

| E. coli M15 | Complex (LB) | Mid-Log (OD600 ~0.6) | Highest µmax | Expression retained |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Protocol: Optimizing Induction Timing for Recombinant Protein

Objective: To determine the optimal induction time point that balances protein yield and host cell health.

Materials:

- Recombinant E. coli strain (e.g., M15 with pQE30-AAR plasmid) [3].

- LB and M9 media with appropriate antibiotics.

- Inducer (e.g., IPTG).

- Spectrophotometer, centrifuge, SDS-PAGE equipment.

Method:

- Inoculation: Prepare a pre-culture by inoculating a single colony into a small volume of LB medium with antibiotic. Grow overnight.

- Main Culture: Dilute the pre-culture into fresh LB and M9 media (in separate flasks) to an OD600 of ~0.05.

- Induction:

- Split each main culture into two flasks at the beginning of the experiment.

- Induce one flask at early-log phase (OD600 ~0.1).

- Induce the other flask at mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6).

- Maintain an uninduced control for each condition.

- Monitoring: Monitor the OD600 of all cultures every hour to generate growth curves and calculate µmax.

- Sampling: Collect cell samples at two time points: mid-log (OD600 ~0.8) and late-log (e.g., 12 hours post-inoculation).

- Analysis:

- Prepare cell lysates from all samples.

- Load equal amounts of total protein (e.g., 50 µg) on an SDS-PAGE gel to compare recombinant protein levels [3].

- Analyze the gel to see which condition (early vs. mid induction) gives the strongest, most stable band, particularly at the late time point.

Diagram: Strategy for Controlling Gene Expression

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Induction Timing

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi System | A "knockdown" tool using a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) to block transcription without cutting DNA [8]. | Fine-tuning gene expression levels to balance metabolic flux and reduce burden [8]. |

| Small Regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) | Short, non-coding RNAs that can bind to target mRNAs to affect their stability or translation [8]. | Attenuating multiple genes in a competitive pathway simultaneously [8]. |

| Metal-dependent FDH | A fast, efficient formate dehydrogenase complex (e.g., from C. necator) for C1 metabolism [16]. | Improving energy generation and growth rate in formatotrophic bioproduction strains [16]. |

| Rosetta E. coli Strains | Host strains containing a plasmid that encodes rare tRNAs [17]. | Improving expression of recombinant proteins whose genes contain codons rarely used in E. coli [17]. |

| Labeled Rich Media | Commercially sourced media (e.g., for 15N/13C labeling) that supports high cell density [17]. | Producing isotopically labeled proteins for NMR studies when yields in minimal media are poor [17]. |

| Proteomics Kits | Kits for label-free quantification (LFQ) proteomic sample preparation and analysis. | Systematically identifying the global proteomic changes and sources of metabolic burden in recombinant hosts [3]. |

FAQs: Understanding Metabolic Burden and System Failure

Q1: What is "metabolic burden" and how does it manifest in my experiments? Metabolic burden refers to the stress imposed on a host cell when it is engineered to express heterologous genes. This burden arises because the cell must divert essential resources—such as energy, nucleotides, and amino acids—away from its normal growth and maintenance functions toward the transcription and translation of non-essential, foreign genes [1]. In practice, you will observe this through several key symptoms:

- Decreased Growth Rate: Engineered cells grow significantly slower than the wild-type strain.

- Impaired Protein Synthesis: Reduced overall capacity to produce proteins, including your target recombinant protein.

- Genetic Instability: Loss of plasmid or accumulation of mutations over time, especially in long fermentation runs.

- Aberrant Cell Morphology: Cells may show an abnormal size or shape [1]. On an industrial scale, these symptoms translate to low production titers and processes that are not economically viable.

Q2: My protein expression is low, but my genetic construct is correct. What are the common system-related causes? Low yield despite a correct construct often points to bottlenecks in the expression system itself. Key factors to investigate include:

- Promoter Strength and Control: The chosen promoter may be too weak or poorly induced. Alternatively, a very strong promoter can create an excessive burden, paradoxically lowering yield [18].

- Plasmid Copy Number: A high-copy-number plasmid can place a significant drain on cellular resources, leading to stress and reduced protein production [18].

- Codon Usage: The heterologous gene may contain codons that are rare in your host organism. This can cause ribosomes to stall, leading to translation errors, low yield, and an increase in misfolded proteins [1].

- Toxic Pathway Intermediates: The product of the heterologous pathway, or an intermediate, may be toxic to the host cell, inhibiting growth and production [7].

Q3: How can I better balance the expression of multiple genes in a pathway? Balancing a multi-gene pathway is a central challenge. Traditional "one-gene-at-a-time" approaches often fail because they do not account for the complex interactions within the pathway. Modern solutions involve:

- Combinatorial Library Approaches: Using tools like GEMbLeR (Gene Expression Modification by LoxPsym-Cre Recombination) to generate vast libraries of promoter and terminator combinations for each gene in a single step. This allows you to screen for optimal expression profiles that maximize flux through the entire pathway [7].

- Gene Attenuation: Instead of completely knocking out competing genes, use CRISPRi or tunable promoters to fine-tune their expression levels. This provides precise control over metabolic flux without creating detrimental bottlenecks or triggering compensatory stress responses [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Metabolic Burden

Problem: Recombinant strain shows poor growth and low product titer.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action & Investigation | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Assess Burden Source | Identify the primary stressor: strong constitutive promoter, high-copy plasmid, or toxic protein/intermediate. | Weaken the promoter, switch to a low-copy plasmid, or use an inducible system to delay expression until high cell density [18]. |

| 2. Evaluate Plasmid & Promoter | Quantify plasmid stability and measure promoter activity directly (e.g., with a reporter gene). Compare different promoter-origin combinations. | Find a balance between plasmid copy number and promoter strength. A medium-strength promoter with a medium-copy plasmid often outperforms a strong promoter with a high-copy plasmid [18]. |

| 3. Optimize Induction | Test different inducer concentrations and induction times. Inducing at a lower cell density or with a sub-maximal inducer concentration can reduce burden. | Use a titratable induction system (e.g., pBAD with L-arabinose) to fine-tune the expression level and minimize stress [18]. |

| 4. Implement Pathway Balancing | For multi-gene pathways, avoid using identical, strong promoters for every gene. | Use a combinatorial method like GEMbLeR to shuffle promoters and terminators, generating a library of expression variants to find the optimal balance [7]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Low Soluble Protein Yield

Problem: Protein is expressed but is insoluble or forms inclusion bodies.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action & Investigation | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Reduce Expression Rate | High expression rates can overwhelm protein folding machinery. Check if the protein is more soluble at lower temperatures or with less induction. | Lower the growth temperature during induction (e.g., to 18-25°C). Reduce inducer concentration to slow down translation [18]. |

| 2. Inspect Codon Usage | Analyze the gene sequence for clusters of rare codons that can cause ribosome stalling and misfolding. | Consider partial codon optimization, but avoid over-optimization as rare codons can sometimes be necessary for proper co-translational folding [1]. |

| 3. Utilize Chaperones | Co-express chaperone proteins (e.g., DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE or GroEL-GroES) to assist with folding. | Transform a plasmid expressing a chaperone team. Induce chaperone expression before or concurrently with your target protein. |

| 4. Test Fusion Tags | Some tags can enhance solubility. | Fuse the target protein to solubility-enhancing tags like MBP (Maltose-Binding Protein) or Trx (Thioredoxin), followed by a cleavage site for removal. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Promoter Strength and Plasmid Copy Number

Objective: To systematically compare the performance of different expression systems and identify the one that minimizes metabolic burden while maximizing soluble yield [18].

Materials:

- E. coli host strain (e.g., BL21(DE3))

- Expression vectors with your gene of interest cloned under different promoters (e.g., PT7lac, Ptac, Ptrc, PBAD) and replication origins (e.g., high-copy pMB1', low-copy p15A).

- Carbon sources: Glucose and glycerol.

- Inducers: IPTG (for lac-based promoters), L-arabinose (for PBAD).

Method:

- Transformation: Transform each expression vector into your host strain.

- Cultivation: Inoculate main cultures in rich medium with both glucose and glycerol as carbon sources. Grow at 37°C to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6).

- Induction: Induce expression with an appropriate concentration of inducer (e.g., 0.1-1.0 mM IPTG).

- Post-Induction: Continue incubation for several hours (e.g., 4-6 hrs at 37°C or overnight at 25°C).

- Analysis:

- Growth Monitoring: Track OD600 before and after induction to calculate growth inhibition.

- Protein Quantification: Harvest cells, lyse, and separate soluble and insoluble fractions. Analyze by SDS-PAGE and quantify yield via densitometry or a fluorescence assay if using a reporter like YFP [18].

- Metabolic Burden Assessment: Compare the specific growth rates and final biomass yields of the different strains.

Protocol 2: Multiplexed Gene Expression Balancing with GEMbLeR

Objective: To rapidly generate a diverse library of yeast strains with varying expression levels for multiple pathway genes and screen for optimized pathway flux [7].

Materials:

- S. cerevisiae strain with your heterologous pathway genes (e.g., astaxanthin pathway) integrated.

- GEMbLeR Constructs: 5' and 3' Gene Expression Modifier (GEM) modules for each pathway gene. Each module contains different promoter/terminator parts flanked by orthogonal LoxPsym sites.

- Cre Recombinase: Plasmid for inducible expression of Cre recombinase.

Method:

- Strain Engineering: Replace the native promoter and terminator of each pathway gene with the corresponding 5' and 3' GEM arrays.

- Library Generation: Introduce the Cre recombinase plasmid into the engineered strain. Induce Cre expression to trigger random recombination (shuffling) within and between GEM arrays, creating a vast library of strains with unique expression profiles.

- Screening: Plate the library and screen for colonies with improved phenotype (e.g., intense color for astaxanthin producers).

- Validation: Isolate top performers, sequence the GEM regions to determine the specific promoter/terminator combination for each gene, and validate production titers in liquid culture [7].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Metabolic Burden Stress Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected stress mechanisms activated by the heterologous expression of proteins, which lead to the symptoms of metabolic burden.

GEMbLeR Experimental Workflow

This flowchart outlines the key steps for optimizing gene expression using the GEMbLeR methodology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Promoters (e.g., PBAD) | Allows precise control of transcription initiation level by varying inducer concentration [18]. | Helps find a balance between high expression and metabolic burden. |

| Vectors with Different Origins of Replication (e.g., p15A, pMB1) | Controls plasmid copy number. A low-copy origin can drastically reduce burden [18]. | Match copy number to promoter strength and protein toxicity. |

| CRISPRi (CRISPR Interference) | Enables gene attenuation without knockout, allowing fine-tuning of native gene expression to redirect metabolic flux [8]. | Ideal for modulating competitive pathways and essential genes. |

| GEMbLeR System | Enables in vivo, multiplexed shuffling of promoters and terminators to create vast expression variant libraries for pathway balancing [7]. | Overcomes the trial-and-error of sequential gene optimization. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Kits | Co-expression of folding helpers (DnaK/J, GroEL/ES) to increase soluble yield of recombinant proteins [1]. | Crucial for expressing complex or aggregation-prone proteins. |

Advanced Tools for Precision Control: From Orthogonal Systems to Combinatorial Optimization

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

Q1: The gene expression output from the TriO system is lower than expected. What could be the cause? Low output can result from several factors. First, verify the functionality of your synthetic transcription factor (sTF). Ensure the transcription-activation domain is appropriate for your desired expression level. Second, check the binding-site modules in your output promoter for proper sTF binding. Finally, confirm that the core promoter module correctly initiates transcription. Using a sub-optimal combination of these three tuning modules is a common cause of low output [19].

Q2: The TriO system shows unexpected expression activity even without the sTF present. How can I resolve this? This indicates a potential lack of orthogonality or system leakiness. Ensure all system components, especially the synthetic promoter and transcription factor, are truly orthogonal and have minimal cross-talk with the host's native regulatory networks. The system's design should use heterologous parts (e.g., a bacterial LexA-DNA-binding domain) to avoid unintended interaction with host transcription machinery. Re-evaluate the specificity of the binding sites used in your output promoter [19].

Q3: How can I achieve different, specific expression levels for multiple genes within the same pathway using TriO? The TriO system's bidirectional architecture is designed for this purpose. You can generate compact expression modules for multiple genes by leveraging the three separate tuning modules: the sTF's activation domain, the binding-site modules, and the core promoter modules. By selecting different combinations for each gene, you can diversify expression levels from negligible to very strong using a single sTF, thus optimizing pathway balance [19].

Q4: My system performance varies significantly between different growth conditions. Is this normal for TriO? No. A key feature of a well-functioning orthogonal system like TriO is minimal interference from standard growth condition changes. The established system was shown to be minimally affected by several tested growth conditions. If you observe significant variance, check for potential host-specific interactions or confirm that your genetic constructs are stable and correctly integrated [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Does the TriO system require an externally added compound for induction? A: No. A major advantage of the TriO system described is that it is independent from externally added compounds, making it highly useful for large-scale biotechnology applications where inducers would be cost-prohibitive [19].

Q: What is the functional principle behind the TriO system? A: The system works as a fixed-gain transcription amplifier. An input signal is transferred via a synthetic transcription factor (sTF) onto a synthetic promoter. This promoter contains a defined core promoter and generates a transcription output signal, allowing for predictable and adjustable expression levels [19].

Q: How do I tune the expression level of my gene of interest using TriO? A: Tuning is achieved through the selection of three separate, modular components:

- The transcription-activation domain of the sTF.

- The binding-site modules in the output promoter.

- The core promoter modules which define the transcription initiation site [19]. By mixing and matching these modules, you can achieve a broad range of expression levels.

Q: In which host organism has the TriO system been demonstrated? A: The development and characterization of the system, as described in the available literature, has been successfully demonstrated in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker's yeast) [19].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: System Assembly and Integration

This protocol outlines the construction of TriO expression cassettes and their stable integration into the host genome, specifically for S. cerevisiae.

Key Steps:

- Construct Assembly: Assemble the expression cassettes for the sTF and the reporter gene(s) using standard molecular biology techniques (e.g., restriction digestion and ligation, Gibson assembly). The sTF typically consists of a bacterial LexA-DNA-binding domain fused to a selected transcription activation domain.

- Vector Linearization: Linearize the integrative plasmids for targeted genomic integration. For example, plasmids based on the pHIS3i backbone can be linearized with NsiI, while pBID-based plasmids can be linearized with EcoRV.

- Host Transformation: Transform the linearized plasmids into the host yeast strain (e.g., CEN.PK113-11C) using a standard lithium acetate protocol.

- Strain Selection: Select for successful transformants on appropriate synthetic complete (SC) agar plates lacking the relevant amino acids (e.g., lacking uracil and histidine for markers URA3 and HIS3) [19].

Protocol 2: Validation of Synthetic Transcription Factor Binding

This method validates the binding of the synthesized sTF to its target DNA binding sites using an Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA).

Key Steps:

- sTF Purification: Express the sTF (e.g., sTF16-6xHIS) in a suitable bacterial system like E. coli BL21(DE3) under IPTG induction. Purify the protein using affinity chromatography, such as Ni-NTA agarose.

- DNA Probe Preparation: Synthesize and label DNA fragments containing the LexA-binding site variants (e.g., B1, B2, B3, B4) with a fluorescent dye like Cy-5.

- Binding Reaction: Assemble binding reactions on ice containing the purified sTF, the labeled DNA probe, poly-dIdC (a non-specific competitor), and reaction buffer.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Incubate the reactions and then load them onto a pre-run, non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 4-20%). Run the gel at a low temperature (6°C) to maintain complex stability.

- Visualization: After electrophoresis, scan the gel using a fluorescence imager (e.g., Typhoon Trio Imager). A shift in the mobility of the DNA probe indicates successful sTF binding [19].

Protocol 3: Characterization of Expression Output

This protocol describes how to measure and characterize the output signal (gene expression) from the TriO system in live cells.

Key Steps:

- Cell Cultivation: Inoculate pre-cultures from single colonies on SCD-HU agar plates. Use these to inoculate liquid cultures (e.g., in SCD-HU medium) in Erlenmeyer flasks to a standard optical density (e.g., OD600 = 0.2).

- Growth and Harvest: Grow the cultures under defined conditions (e.g., temperature, shaking) until they reach the desired growth phase.

- Output Measurement: If using a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP), analyze cell fluorescence directly using flow cytometry or a fluorescence plate reader. The fluorescence intensity serves as a direct measure of the system's transcription output signal [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials used in the establishment and operation of the orthogonal TriO gene expression system.

| Reagent / Component | Function in the System | Key Details / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Transcription Factor (sTF) | Core regulator; binds target promoter to activate transcription. | Composed of a heterologous DNA-binding domain (e.g., bacterial LexA) fused to a transcription activation domain [19]. |

| Synthetic Promoter | Drives expression of the target gene(s). | Contains modular LexA-binding sites and a defined core promoter sequence [19]. |

| Binding-Site Modules | Tune sTF binding affinity and occupancy. | Specific sequences (e.g., B1, B2, B3, B4) within the synthetic promoter that the sTF recognizes [19]. |

| Core Promoter Modules | Define the baseline transcription initiation rate. | Selected sequence that determines the strength of the output signal independently of the sTF [19]. |

| Reporter Genes | Quantify system output and performance. | Fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP) or other easily assayable genes [19]. |

| Host Strain | Chassis for system implementation. | Saccharomyces cerevisiae CEN.PK113-11C [19]. |

System Workflow and Logical Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture and workflow of the TriO orthogonal gene expression system.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ: My pathway expression is causing a high metabolic burden, reducing host cell fitness. What combinatorial strategies can I use to balance expression? Several high-throughput cloning methods are designed specifically to address this issue. COMPASS (COMbinatorial Pathway ASSembly) and GEMbLeR (Gene Expression Modification by LoxPsym-Cre Recombination) are two key technologies. COMPASS uses orthogonal artificial transcription factors (ATFs) and homologous recombination to generate thousands of constructs in parallel, allowing you to rapidly test different expression level combinations for up to ten genes to find a balance that minimizes burden [20]. GEMbLeR uses Cre-LoxPsym recombination to shuffle promoter and terminator modules in vivo, creating libraries where each gene's expression can vary over 120-fold, enabling you to find a profile that optimizes flux and reduces metabolic stress [21].

FAQ: What is the difference between a counter-screen and an orthogonal assay in HTS hit validation? In high-throughput screening (HTS), these assays serve distinct purposes for eliminating false positives:

- A Counter Screen is designed to assess specificity and identify compounds that interfere with the assay technology itself (e.g., autofluorescence, signal quenching, aggregation) rather than the biological target. It often bypasses the actual biological reaction to isolate the compound's effect on the detection system [22].

- An Orthogonal Assay confirms the bioactivity of a primary hit but uses an independent readout technology or assay condition to analyze the same biological outcome. Examples include using luminescence to confirm a fluorescence-based primary readout, or employing biophysical methods like surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [22].

FAQ: Can I optimize a single genetic sequence for high expression in two different host organisms? This depends heavily on the chosen organisms. Dual optimization is not always recommended because the most preferred codons can differ significantly between distantly related hosts. For example, optimization for both E. coli and yeast is not advised, as their codon usage tables are too dissimilar. However, dual optimization can work well for more closely related hosts, such as Pichia and Saccharomyces or human (HEK293) and hamster (CHO) cells [23].

FAQ: How do I verify that a synthetic gene has been constructed correctly? Commercial gene synthesis services typically verify every synthetic gene via double-stranded DNA sequencing by an in-house sequencing service, guaranteeing 100% sequence accuracy for every cloned gene [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Product Titer Despite High Pathway Expression

Symptoms: The host strain shows poor growth or viability, and the desired metabolic product titer is low, indicating potential metabolic burden or imbalanced pathway flux.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Relevant Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Imbalanced expression of pathway genes, leading to bottlenecks and accumulation of intermediate metabolites. | Use combinatorial assembly to systematically vary the expression of each gene. | COMPASS [20], GEMbLeR [21] |

| Overexpression of all genes causing excessive metabolic load. | Employ inducible systems and weaker expression modulators to fine-tune expression downward. | Inducible ATFs in COMPASS [20] |

| The selected genomic integration locus is suboptimal, causing silencing or variegated expression. | Test integrations at different, well-characterized neutral loci in the genome. | COMPASS multi-locus CRISPR/Cas9 integration [20] |

Recommended Experimental Workflow:

- Library Generation: Use a combinatorial method like GEMbLeR to create a vast library of strain variants, each with a unique expression profile for the pathway genes [21].

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Screen the library for improved product output. For colored products like carotenoids, simple color screening can be used. For uncolored products, employ a biosensor or other HCS method [20] [25].

- Hit Validation: Isolate top-performing hits and validate their performance in small-scale cultures. Use analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, MS) to precisely quantify the product titer and intermediate levels [22].

- Characterization: Analyze the genotype (e.g., promoter/termininator combination) of the best-performing strains to understand the optimal expression profile [21].

Problem: High False Positive Rate in Primary HTS

Symptoms: Many active compounds from the primary screen fail to show activity in subsequent confirmation tests.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Assay technology interference (e.g., compound autofluorescence, quenching, aggregation). | Implement a counter-screen that uses the same readout technology but bypasses the biological reaction [22]. |

| Non-specific compound activity (e.g., redox activity, protein alkylation). | Use an orthogonal assay with a different readout technology (e.g., switch from fluorescence to luminescence or a biophysical method) [22]. |

| General cellular toxicity that mimics the desired phenotypic outcome. | Conduct cellular fitness screens (e.g., cell viability, cytotoxicity assays) to exclude generally toxic compounds [22]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: COMPASS for Pathway Assembly

The COMPASS method assembles biochemical pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through three sequential cloning levels [20]:

Level 0: Unit Construction

- Objective: Clone individual genetic elements.

- Procedure:

- ATF/BS Units: Assemble combinations of artificial transcription factors (ATFs) and their binding sites (BS) into an "Entry vector X." This involves PCR-amplifying ATF fragments and BS fragments with homologous primers, followed by overlap-based recombinational cloning.

- CDS Units: Assemble the enzyme coding sequence (CDS), a yeast terminator, and an E. coli selection marker promoter into the PacI-digested Entry vector X.

- Timeline: Approximately 1 week.

Level 1: Module Construction

- Objective: Combinatorially assemble ATF/BS units upstream of CDS units to create complete ATF/BS-CDS modules.

- Procedure: Perform simultaneous cloning reactions using Destination and Acceptor vectors from two different sets (Set 1 and Set 2). Correct assemblies are selected for using appropriate selection media.

- Timeline: Approximately 1 week.

Level 2: Pathway Assembly

- Objective: Combinatorially assemble up to five ATF/BS-CDS modules into a single vector.

- Procedure: Use the assembled modules from Level 1 with the Destination and Acceptor vector system. The final construct can be used plasmid-based or integrated into the genome, facilitated by CRISPR/Cas9 for multi-locus modifications.

- Timeline: Approximately 4 weeks.

Detailed Methodology: GEMbLeR for Expression Tuning

GEMbLeR is an in vivo method for multiplexed gene expression modification in S. cerevisiae [21]:

- Strain Engineering:

- Replace the native promoter and terminator of your target genes with a "Gene Expression Modulator" (GEM) construct.

- The 5' GEM consists of an array of different upstream promoter elements (UPEs), and the 3' GEM consists of an array of different terminator sequences. These blocks are separated by orthogonal LoxPsym recombination sites.

- Library Generation:

- Induce the expression of Cre recombinase in the engineered strain.

- Cre recombinase will catalyze deletion, inversion, and duplication events between the LoxPsym sites, shuffling the UPEs and terminators for each gene.

- This creates a vast library of strain variants, where each target gene's expression is driven by a new, unique combination of promoter and terminator.

- Screening:

- Screen or select the resulting library for clones with improved performance (e.g., higher production of a desired compound).

Quantitative Data from Combinatorial Optimization Studies

Table 1: Expression Ranges of Combinatorial Tools

| Tool / Component | Expression Range | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| COMPASS ATF/BS Library [20] | ~0.4 to 5-fold of TDH3 promoter (~300 to 4000 AU) | 9 plant-derived, inducible ATF/BS combinations. |

| GEMbLeR [21] | Over 120-fold per gene | In vivo shuffling of promoters/terminators via Cre-LoxPsym. |

Table 2: High-Throughput Screening Assay Types

| Assay Type | Primary Readout | Use Case in Pathway Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence-based [22] | Fluorescence intensity | Reporter gene expression, biosensor activity. |

| Luminescence-based [22] | Luminescence intensity | Orthogonal confirmation, viability assays (CellTiter-Glo). |

| Absorbance-based [22] | Absorbance | Screening for colored products (e.g., β-carotene). |

| High-Content Imaging [22] | Multiparametric image analysis | Single-cell analysis, detailed morphology, and fitness. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Combinatorial Optimization |

|---|---|

| Artificial Transcription Factors (ATFs) [20] | Orthogonal, tunable regulators to control gene expression without interfering with native host regulation. |

| LoxPsym Sites [21] | Symmetrical, orthogonal recombination sites that enable predictable DNA shuffling in vivo for library generation. |

| Cre Recombinase [21] | Enzyme that catalyzes recombination at LoxPsym sites, triggering the shuffling of genetic modules in the GEMbLeR system. |

| Codon-Optimized Genes [23] [24] | Gene sequences optimized for the host organism's codon usage to maximize reliable translation and protein yield. |

| Modular Cloning Vectors (Entry, Acceptor, Destination) [20] | A standardized set of plasmids designed for efficient, multi-level, and scarless assembly of multiple genetic parts. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My CRISPR system is editing genes at unintended, off-target sites. How can I improve its specificity?

- Problem: The Cas nuclease cuts DNA at locations other than the intended target, which can lead to unwanted mutations and confound experimental results [26].

- Solutions:

- Optimize gRNA Design: Use highly specific guide RNA (gRNA) sequences. Leverage online design tools that utilize advanced algorithms to predict and minimize potential off-target binding sites [26].

- Use High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Replace the standard Cas9 nuclease with high-fidelity variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9, HypaCas9). These engineered proteins have reduced non-specific DNA contacts, significantly lowering off-target effects [27] [26].

- Employ RNP Delivery: Consider delivering the CRISPR system as a pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex of Cas protein and gRNA. This can shorten the system's activity window in the cell, reducing opportunities for off-target cleavage [28].

- Leverage Cas Orthologs: Explore alternative Cas proteins like Cas12a, which often demonstrate lower off-target rates compared to SpCas9 in certain microalgae and microbes [27].

Q2: I am experiencing low editing efficiency in my microbial host. What factors should I investigate?

- Problem: The proportion of cells that successfully incorporate the desired genetic edit is unacceptably low.

- Solutions:

- Verify gRNA and Promoter: Confirm your gRNA is unique within the host genome and of optimal length. Ensure the promoters driving the expression of both Cas9 and gRNA are strong and functional in your specific host cell type. Codon-optimization of the Cas9 gene for your host organism can also dramatically improve expression and efficiency [27] [26].

- Optimize Delivery Method: The efficiency of delivering CRISPR components is a major bottleneck. Test and optimize physical methods like electroporation or chemical methods like polymer-based transfection for your specific cell type. For stubborn hosts, advanced biological vectors (e.g., engineered viruses) may be necessary [27].

- Manage Cell Toxicity: High concentrations of CRISPR components can cause cell death. Titrate the amounts of gRNA and Cas9 (as DNA, mRNA, or protein) to find a balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [26].

Q3: How can I dynamically control multiple genes in a metabolic pathway without causing excessive metabolic burden?

- Problem: Engineering complex traits requires coordinated expression of multiple genes, but conventional overexpression can overload host cells, slowing growth and reducing productivity.

- Solutions:

- Adopt a Multi-Tool Approach: Move beyond simple gene knock-outs. Use a combination of CRISPR tools for fine control:

- CRISPRi (interference): Uses a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) fused to a repressor domain to precisely down-regulate competitive or inhibitory genes [29].

- CRISPRa (activation): Uses dCas9 fused to an activator domain to up-regrate key biosynthetic genes without the genetic instability sometimes associated with plasmid-based overexpression [30] [29].

- Implement Tunable Systems: Use inducible promoters (e.g., rhamnose-inducible) to control the timing and level of dCas9-effector expression, allowing for dynamic pathway regulation in response to fermentation stages [30].

- Explore Multiplexed Systems: Utilize systems that allow co-expression of multiple gRNAs to target several genes simultaneously, enabling coordinated rewiring of metabolic networks [27] [29].

- Adopt a Multi-Tool Approach: Move beyond simple gene knock-outs. Use a combination of CRISPR tools for fine control:

Q4: What are the major challenges in translating a CRISPR-edited microbial strain from the lab to industrial-scale production?

- Problem: A strain that performs well in small-scale cultures fails to maintain its productivity in a large-scale bioreactor.

- Solutions:

- Ensure Genetic Stability: Edited strains can sometimes revert. Perform long-term serial passaging to confirm that the engineered traits are stable over many generations in the absence of selection pressure.

- Address Scalability: Conditions in a large bioreactor (e.g., nutrient gradients, shear stress) differ from shake flasks. Use adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) or further engineer traits like stress resilience to improve robustness under scale-up conditions [27] [31].

- Plan for Regulatory and Manufacturing Hurdles: For therapies or products for human use, transitioning to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)-grade reagents is essential. This includes sourcing GMP-grade gRNAs and nucleases to ensure purity, safety, and efficacy, which is a critical step for clinical trials [32].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Dual-Mode CRISPRa/i System for Pathway Optimization

This protocol outlines the application of a CRISPR activation and interference (CRISPRa/i) system for coordinated gene regulation in E. coli, based on a 2025 study [30].

System Assembly:

- Construct a plasmid expressing a PAM-flexible dCas9 variant (e.g., dxCas9) fused to an engineered effector domain (e.g., cAMP receptor protein, CRP). Place this under the control of an inducible promoter (e.g., the rhamnose-inducible PrhaBAD).

- Clone guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting your genes of interest into a separate expression plasmid under a constitutive promoter.

Strain Transformation:

- Co-transform the dCas9-effector plasmid and the gRNA plasmid into your production host strain (e.g., E. coli MG1655).

Cultivation and Induction:

- Grow the transformed strain in a suitable medium (e.g., LB) with antibiotics for plasmid maintenance.

- When the culture optical density (OD600) reaches 0.4–0.6, induce the system by adding 1 mM L-rhamnose.

Validation and Analysis:

- Fluorescence Measurement: If using reporter genes, measure fluorescence after 24 hours of induction to confirm transcriptional changes [30].

- Product Titer Measurement: Use HPLC or GC-MS to quantify the target metabolite (e.g., violacein) to assess the impact of the genetic perturbations on pathway flux.

Protocol 2: Multiplexed CRISPRi for Repressing Competitive Pathways

This protocol describes a method for simultaneously knocking down multiple genes to re-route metabolic flux.

gRNA Array Design:

- Design multiple gRNAs targeting genes in competing or redundant pathways.

- Assemble these gRNAs into a single transcriptional unit using a tRNA-processing system or as a scaffold RNA (scRNA) array to enable simultaneous expression.

Delivery and Genotype Validation:

- Deliver the CRISPRi system (dCas9-repressor and multiplexed gRNA array) to the host cells.

- Isolate single-cell clones and use next-generation sequencing to verify the presence of all gRNAs and the integrity of the dCas9 gene.

Phenotypic Screening:

- Screen clones for reduced expression of target genes via RT-qPCR.

- Measure the accumulation of the desired end-product and the intermediates of the enhanced pathway to confirm successful flux rerouting.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their functions for setting up CRISPR-based metabolic engineering experiments.

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 | Reduces off-target editing; crucial for clean experimental outcomes [27] [26]. | SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9 |

| dCas9 Effector Fusions | Serves as a programmable scaffold for transcriptional regulation (CRISPRa/i) or epigenetic modification without DNA cutting [27] [29]. | dCas9-VP64 (activator), dCas9-KRAB (repressor) |

| Alternative Cas Orthologs | Offers different PAM requirements, smaller size for easier delivery, and potentially lower off-target rates [27]. | Cas12a (FnCas12a), CasMINI |

| GMP-Grade gRNA | Essential for clinical development; ensures purity, safety, and consistency for therapeutic applications [32]. | Required for FDA-approved clinical trials. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | An efficient method for in vivo delivery of CRISPR components, particularly effective for targeting liver cells [33]. | Used in clinical trials for hATTR and HAE [33]. |

| Inducible Promoters | Allows precise temporal control over CRISPR system expression, enabling dynamic pathway regulation and managing cellular toxicity [30]. | Rhamnose-inducible (PrhaBAD), ATc-inducible |

Experimental Workflow and System Architecture

The following diagrams illustrate a generalized experimental workflow and the core components of a CRISPRa/i system for metabolic engineering.

CRISPR Metabolic Engineering Workflow

Dual-Mode CRISPRa/i System Function

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core advantage of using a plug-and-play approach in metabolic pathway engineering? A plug-and-play, or modular, approach allows researchers to rapidly assemble and test genetic circuits using standardized, interchangeable parts. This methodology significantly reduces the time required for prototyping by simplifying the replacement and optimization of individual pathway components, thereby accelerating the design-build-test cycle for developing efficient microbial cell factories [34].

Q2: Why is fine-tuned gene attenuation often preferable to complete gene knockout for optimizing metabolic flux? Complete gene knockout can cause metabolic bottlenecks, disrupt essential cellular functions, and trigger compensatory reactions that reduce product yield. Gene attenuation, by contrast, allows for precise reduction of enzyme activity without fully disrupting a pathway. This facilitates balanced metabolic flux, minimizes the accumulation of toxic intermediates, and helps maintain cell viability, which is crucial for high-yield bioproduction [8].

Q3: How can codon usage negatively impact the success of a plug-and-play experiment, and how can this be mitigated? An exogenous gene with codon usage that deviates significantly from the host's tRNA pool can sequester translational resources and create a substantial metabolic burden. This leads to reduced growth rates and lower protein yields. Mitigation strategies include codon optimization to match the host's preferred usage and using specialized host strains engineered to overexpress rare tRNAs [5].

Q4: My pathway expression is causing severe host cell growth impairment. What are the first elements I should check? First, assess the strength of your promoters and ribosome binding sites (RBS), as overly strong constitutive expression can drain cellular resources. Second, analyze the codon adaptation index (CAI) of your heterologous genes. Finally, verify that you are not over-expressing genes in competitive branches that deplete essential precursors needed for central metabolism [8] [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Product Yield Despite High Pathway Expression

This often indicates a high metabolic burden, where resource diversion to the heterologous pathway impairs the host's ability to produce the target compound.

- Potential Cause 1: Overly strong constitutive expression of pathway genes, leading to excessive resource consumption.

- Potential Cause 2: Codon usage mismatch between heterologous genes and the host organism.

- Solution: Recode genes using global codon harmonization strategies that match the host's genomic codon usage bias, rather than simply maximizing optimal codons, to avoid over-optimization and tRNA depletion [5].

- Potential Cause 3: Inefficient sgRNA activity in CRISPR-based systems, leading to incomplete attenuation or editing.

- Solution: Use validated algorithms like Benchling for sgRNA design and employ Western blotting to confirm protein-level knockdown, as high INDEL frequency does not always guarantee loss of protein function [35].

Issue 2: Unstable Expression or Loss of Genetic Constructs

This is typically related to genetic instability or toxicity that selects for cells that have mutated or lost the engineered pathway.

- Potential Cause 1: Toxicity of pathway intermediates or products.

- Solution: Employ dynamic regulation or two-phase fermentation strategies. Use sensors and promoters that respond to metabolic stress to automatically downregulate pathway expression before toxicity becomes lethal.

- Potential Cause 2: Plasmid instability due to high copy number or metabolic burden.

- Solution: Consider switching to genomic integration systems, especially site-specific systems like Bxb1 or FRT, to ensure stable inheritance without the need for antibiotic selection [36].

Issue 3: Inconsistent Performance Between Prototyping and Scale-Up

Results from small-scale cultures often fail to translate to larger bioreactors due to changing environmental conditions.

- Potential Cause 1: Poor performance of genetic parts under scaled-up conditions (e.g., different oxygenation, nutrient gradients).

- Solution: Prototype with genetic parts and circuits known to be robust across diverse conditions. Use synthetic promoters that are less sensitive to physiological changes and validate part performance in micro-bioreactors or mini-fermenters that better mimic production-scale conditions.

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Impact of Codon Optimization Level on Protein Yield and Host Burden

Data derived from expression of sfGFP and mCherry2 in E. coli with varying Fraction of Optimal Codons (FOP) [5].

| Fraction of Optimal Codons (FOP) | Relative Protein Yield (sfGFP) | Relative Growth Rate Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | Low | Moderate |

| 25% | Low to Moderate | Moderate |

| 50% | Moderate | Low |

| 75% | High | Low |

| 90% | High (but potential over-optimization) | Can be High |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Gene Expression Control Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Tools/Methods | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Knockout | Completely removes or deactivates a gene. | CRISPR-Cas9, Homologous Recombination | Studying essential gene function; eliminating competing pathways. |