Overcoming Biomass Recalcitrance: Advanced Strategies for Efficient Biofuel Production

The inherent recalcitrance of lignocellulosic biomass presents a fundamental barrier to the cost-effective production of second-generation biofuels.

Overcoming Biomass Recalcitrance: Advanced Strategies for Efficient Biofuel Production

Abstract

The inherent recalcitrance of lignocellulosic biomass presents a fundamental barrier to the cost-effective production of second-generation biofuels. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists, exploring the structural and chemical basis of biomass recalcitrance, from the protective role of lignin to cellulose crystallinity. It systematically evaluates a spectrum of pretreatment methodologies, including emerging green solvents like ionic liquids and ethanolamine, alongside genetic modification strategies. The review further delves into optimization techniques using machine learning and mechanistic modeling, and offers a critical comparative assessment of pretreatment efficacy based on sugar yield, environmental impact, and economic viability. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications and validation frameworks, this article serves as a strategic guide for developing robust, scalable, and sustainable biorefinery processes.

Deconstructing the Plant Cell Wall: The Multifaceted Nature of Biomass Recalcitrance

Biomass recalcitrance is the inherent resistance of plant cell walls to deconstruction and degradation, posing a significant barrier to cost-effective biofuel production. [1] [2] This natural resistance stems from the complex structural and chemical composition of lignocellulosic biomass, primarily comprising cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which are intricately cross-linked. [1] [3] This robustness, essential for plant survival in nature, becomes a major hurdle in industrial settings because it limits the release of simple sugars needed for fermentation into biofuels. [4] [1] Overcoming this recalcitrance is a central challenge in enabling the emergence of a sustainable, cellulosic biofuels industry. [5]

Technical Support & Troubleshooting FAQs

This section addresses common experimental challenges in biomass deconstruction research.

FAQ 1: Why is my enzymatic hydrolysis yield low even after pretreatment?

Low enzymatic hydrolysis efficiency can be attributed to several factors related to residual biomass recalcitrance.

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate Lignin Removal or Relocation. Lignin acts as a physical barrier and can non-productively bind to enzymes. [4] [1] If pretreatment fails to sufficiently remove or modify lignin, it will continue to block access to cellulose.

- Potential Cause 2: High Cellulose Crystallinity (CrI). Pretreatment may not have effectively disrupted the crystalline structure of cellulose. Crystalline regions are less accessible to enzymes than amorphous regions. [6]

- Potential Cause 3: Inhibitor Formation. Harsh pretreatment conditions can generate fermentation inhibitors like furans and phenolics, which can also inhibit enzymatic activity. [7]

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Characterize Pretreated Solids: Analyze the composition (lignin, carbohydrate content) and structure (crystallinity via XRD) of your solid residue. [6] This data will pinpoint the specific barrier.

- Optimize Pretreatment Severity: Adjust factors like temperature, time, and catalyst concentration to better balance recalcitrance reduction with inhibitor formation.

- Use Enzyme Additives: Supplement your cellulase cocktail with lignin-blocking additives or xylanases to improve access to cellulose. [6]

FAQ 2: How do I select the best pretreatment method for my feedstock?

The optimal pretreatment strategy is highly dependent on the biomass type and the desired conversion pathway.

- Key Consideration: Feedstock Composition. The inherent levels of lignin, hemicellulose, and acetyl groups vary between herbaceous and woody biomass, requiring different approaches. [8]

- Guidance:

- For High-Lignin Biomass (e.g., hardwoods): Consider pretreatments that effectively solubilize lignin, such as alkaline or organosolv methods. [3]

- For High-Hemicellulose Biomass (e.g., agricultural residues): Dilute acid or steam explosion can be effective for hemicellulose hydrolysis. [7]

- For a Balanced Approach: Ionic liquid (IL) pretreatment is tunable and can disrupt both lignin and cellulose crystallinity. [9] Always conduct a compositional analysis before selecting a method.

FAQ 3: My chosen biocatalyst is underperforming on untreated biomass. What are my options?

Native biomass is highly recalcitrant, and most biocatalysts require some form of augmentation.

- Solution 1: Employ Non-Biological Augmentation. This is often necessary to achieve high sugar yields. [8] Options include:

- Solution 2: Choose a Superior Biocatalyst. Some microorganisms are inherently more effective. Thermophilic anaerobes like Clostridium thermocellum have been shown to achieve carbohydrate solubilization yields several-fold higher than industry-standard fungal cellulase on various feedstocks. [5] [8]

- Solution 3: Utilize Genetic Modification. Use genetically engineered feedstocks with reduced recalcitrance (e.g., low-lignin switchgrass). Studies show that combining better plants with better microbes has a cumulative positive effect. [5] [8]

Key Experimental Protocols for Assessing Recalcitrance

Standardized protocols are essential for generating comparable data on biomass deconstruction.

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Saccharification Assay

This protocol is designed for the rapid screening of large numbers of biomass samples (e.g., natural variants or transgenics) for recalcitrance phenotyping. [5]

- Objective: To quantitatively measure the enzymatic digestibility of biomass samples.

- Materials:

- Pre-milled biomass (e.g., pass through a 20-mesh screen)

- Commercial cellulase cocktail (e.g., Novozymes Cellic CTec2)

- Buffer (e.g., 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 4.8)

- Sodium azide (to prevent microbial contamination)

- Microplates or glass tubes

- Heating block or incubator

- DNS reagent or HPLC for sugar analysis

- Method:

- Preparation: Dispense 10-50 mg of biomass (dry weight basis) into each reaction vessel.

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Add buffer and cellulase enzyme (e.g., 20 mg protein per g glucan). Include controls without enzyme and substrate blanks.

- Incubation: Incubate at 50°C with constant mixing for 72 hours.

- Analysis: Terminate the reaction and quantify the released reducing sugars (glucose and xylose) using the DNS method or, for higher accuracy, HPLC.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the sugar release as a percentage of the theoretical maximum based on the biomass's carbohydrate composition.

Protocol 2: Consolidated Bioprocessing (CBP) with Clostridium thermocellum

This protocol uses a potent thermophilic bacterium to simultaneously deconstruct biomass and ferment sugars, providing an integrated measure of recalcitrance. [5] [8]

- Objective: To assess the total carbohydrate solubilization (TCS) of a biomass sample by a microbial catalyst without added enzymes.

- Materials:

- Clostridium thermocellum (e.g., strain DSM 1313)

- Anaerobic chamber for culture handling

- MTC-5 or similar defined medium

- Serum bottles or bioreactors

- Pre-milled and autoclaved biomass

- HPLC for metabolite analysis (ethanol, organic acids, residual sugars)

- Method:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow C. thermocellum on a cellobiose-based medium to mid-log phase.

- Fermentation Setup: Transfer 5% (v/v) inoculum to serum bottles containing medium and biomass (e.g., 5 g/L).

- Incubation: Incubate at 60°C without shaking for 5-7 days.

- Analysis: Measure residual solids (for TCS calculation) and fermentation products via HPLC.

- Data Analysis:

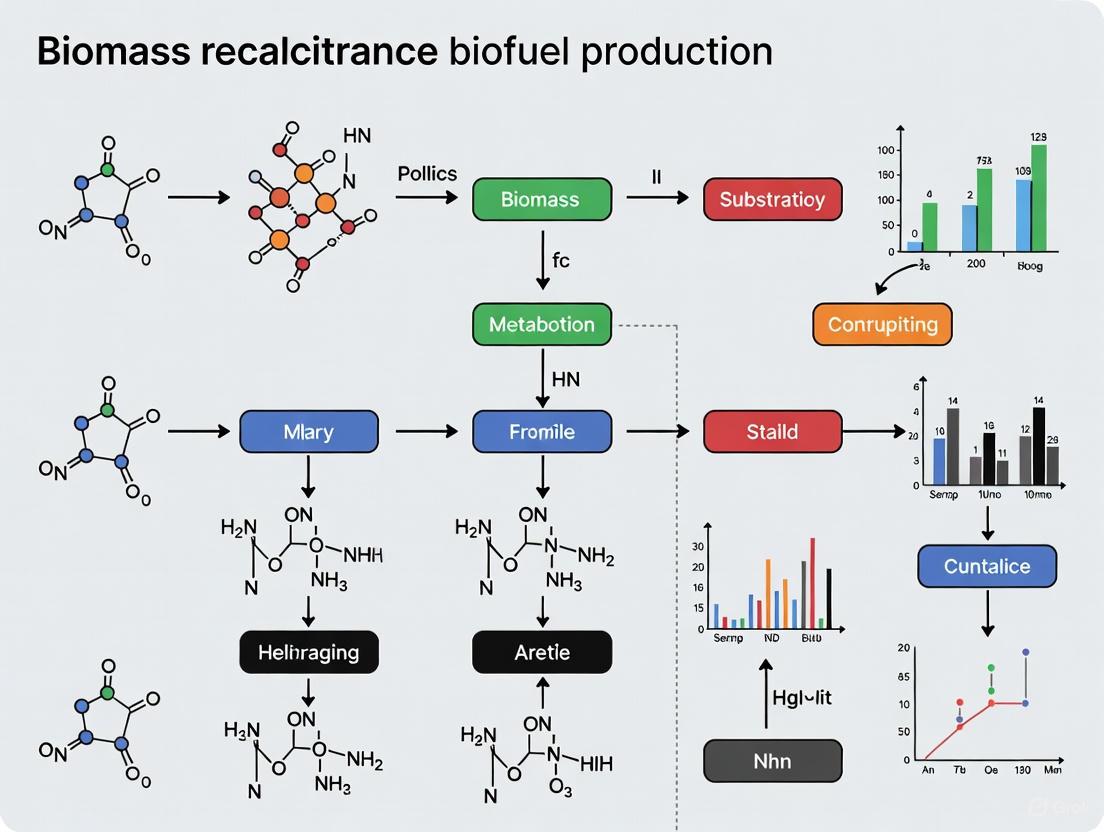

Visualizing Recalcitrance and Deconstruction Strategies

The following diagrams illustrate the multi-scale nature of biomass recalcitrance and a strategic workflow for overcoming it.

Biomass Recalcitrance Factors

Multilevel Strategy to Overcome Recalcitrance

Quantitative Data on Deconstruction Efficiency

The effectiveness of deconstruction strategies varies significantly based on the levers employed. The table below summarizes quantitative data from a combinatoric study investigating these levers. [8]

Table 1: Impact of Multiple Recalcitrance Levers on Total Carbohydrate Solubilization (TCS)

| Recalcitrance Lever | Example | Typical Impact on TCS (Relative Magnitude) | Key Findings & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Biological Augmentation | CELF Pretreatment [8] or Ball Milling Cotreatment [5] [8] | Highest | Enabled TCS >90% for most feedstocks. Often necessary for high yields. [8] |

| Biocatalyst Choice | Clostridium thermocellum vs. fungal cellulase [5] [8] | High | C. thermocellum achieved 2-4 fold higher solubilization than fungal cellulase on recalcitrant feedstocks. [8] |

| Feedstock Choice | Pre-senescent grass vs. woody angiosperms [8] | Medium | Natural variation in cell wall composition dictates baseline recalcitrance. |

| Plant Genetic Modification | COMT-downregulated switchgrass [5] [8] | Medium (without augmentation) | Significant TCS increase for most biocatalyst combinations without augmentation. Effect can be small with augmentation. [8] |

| Natural Variants | Low-recalcitrance Populus line [8] | Low to Medium | Screening natural populations can identify less recalcitrant lines. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Biomass Recalcitrance Research

| Category | Item | Function in Research | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocatalysts | Clostridium thermocellum | A thermophilic, anaerobic bacterium used for Consolidated Bioprocessing (CBP). Highly effective at solubilizing native biomass. [5] [8] | Used to assess inherent biological recalcitrance without added enzymes. |

| Commercial Cellulase Cocktails | Fungal enzyme mixtures for enzymatic hydrolysis/saccharification. | Novozymes Cellic CTec2/HTec2; standard for comparing hydrolyzability of pretreated biomass. [8] | |

| Pretreatment Reagents | Ionic Liquids (ILs) | "Green" solvents that disrupt cellulose crystallinity and dissolve lignin. [9] | e.g., [EMIM][OAc]; tunable properties allow for targeted deconstruction. |

| Cosolvent Systems | Enhances lignin removal during pretreatment. | e.g., Cosolvent-Enhanced Lignocellulosic Fractionation (CELF) using tetrahydrofuran. [5] [8] | |

| Analytical Tools | Glycome Profiling | A high-throughput technique using antibodies to characterize cell wall polymers. [5] | Reveals changes in hemicellulose and pectin structure in modified plants. |

| Raman Spectroscopy / AFM | Advanced imaging to visualize chemical components and cell wall architecture at sub-micron levels. [5] | Tracks changes in lignin and cellulose distribution during deconstruction. |

The plant cell wall is a complex, robust structure designed by nature to protect against microbial and enzymatic deconstruction. This inherent resistance, termed biomass recalcitrance, is the primary barrier to the efficient and cost-effective conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into biofuels and bioproducts [10] [3]. Understanding this "structural fortress" is crucial for advancing biofuel research. The recalcitrance is not due to a single component but emerges from the intricate and synergistic interplay between the three key polymers: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [11] [5]. This guide provides troubleshooting support for researchers grappling with the challenges posed by this robust structure during experimental deconstruction.

FAQ: Understanding the Recalcitrant Structure

Q1: What are the specific roles of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in causing biomass recalcitrance?

- Cellulose: Acts as the primary load-bearing scaffold. Its crystalline structure, where linear chains of glucose are packed tightly via hydrogen bonds, makes it highly resistant to enzymatic attack. The degree of polymerization (DP) and crystallinity are key factors; longer chains and higher crystallinity increase recalcitrance [11].

- Hemicellulose: This branched, amorphous polymer forms a cross-linked matrix that embeds the cellulose microfibrils. It acts as a physical barrier, limiting enzyme access to cellulose. Its acetyl groups can further hinder enzyme activity by causing steric hindrance [11].

- Lignin: This complex, aromatic polymer acts as a waterproof, durable sealant. It provides structural integrity and physically blocks enzyme access to polysaccharides. Furthermore, it can irreversibly adsorb cellulases through hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions, effectively deactivating them [11] [12].

Q2: Which component has the greatest impact on recalcitrance?

The impact is interdependent, but lignin is often considered the most significant contributor due to its dual role as both a physical barrier and an enzyme inhibitor [12] [5]. However, the removal of hemicellulose can be equally critical in certain biomass types, as it dramatically increases porosity and enzyme accessibility [11]. The dominant factor can vary depending on the biomass species and pretreatment method used.

Q3: How does the interaction between these polymers contribute to overall strength?

At the nanoscale, the polymers interact through strong hydrogen bonding and covalent linkages, forming a Lignin-Carbohydrate Complex (LCC). Molecular dynamics simulations, such as those done on coconut endocarp, show that the cellulose-hemicellulose interface exhibits the strongest interaction, primarily due to hydrogen bonding, which facilitates efficient load transfer. While the cellulose-lignin interface is weaker, the lignin matrix itself provides a rigid, cross-linked network that encases the other polymers, contributing significantly to the structural integrity and recalcitrance of the overall assembly [13].

Q4: Can genetic modification of plants reduce biomass recalcitrance?

Yes, genetic engineering is a promising strategy. Research has demonstrated that downregulating genes involved in lignin biosynthesis can lead to transgenic plants with lower recalcitrance without necessarily compromising biomass yield. For example, studies on poplar and switchgrass have shown that reducing lignin content or altering its composition (e.g., the S/G ratio) can significantly improve saccharification efficiency [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Low Sugar Yield in Enzymatic Hydrolysis

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Consistently low glucose release, even after pretreatment. | High Lignin Content: Lignin is physically blocking cellulose and/or non-productively binding enzymes. | - Increase pretreatment severity to remove more lignin [12].- Use surfactant additives to block lignin-enzyme binding sites [11].- Consider biological pretreatments with lignin-degrading fungi. |

| Good hemicellulose sugar release but poor cellulose conversion. | Insufficient Cellulose Accessibility: Pore volume and specific surface area are too low for enzymes to penetrate. | - Optimize pretreatment to remove more hemicellulose, which increases porosity [11] [14].- Incorporate accessory enzymes (e.g., lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases) to disrupt crystalline cellulose. |

| High initial hydrolysis rate that slows down dramatically. | Product Inhibition or Enzyme Inactivation: Accumulating sugars or phenolic compounds from lignin are inhibiting enzymes. | - Use a fed-batch hydrolysis system to lower sugar concentrations.- Employ enzyme blends with β-glucosidase to alleviate cellobiose inhibition.- Remove lignin-derived phenolics via washing or detoxification steps [11]. |

Issues Related to Biomass Physical Structure and Handling

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Irreversible loss of digestibility after drying pretreated biomass. | Drying-Induced Hornification: The process of air-drying or oven-drying causes the cellulose fibers to collapse and fuse, drastically reducing accessibility. | Freeze-dry biomass samples to preserve the porous structure [14]. If freeze-drying is not possible, keep the biomass in a never-dried state for hydrolysis experiments. |

| High variability in hydrolysis results between replicate samples. | Biomass Heterogeneity: The feedstock has not been properly homogenized, leading to inconsistent particle size and composition. | Grind and sieve the biomass to a uniform particle size (e.g., 20-60 mesh) before pretreatment to ensure a representative and consistent sample [15]. |

| Difficulty reproducing published protocols with a new biomass type. | Feedstock-Specific Recalcitrance: The chemical and structural factors contributing to recalcitrance differ significantly between biomass species (e.g., hardwood vs. grass). | - Conduct a full compositional analysis (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) of your feedstock.- Perform a simons' staining or similar assay to quantify cellulose accessibility and tailor the pretreatment accordingly [14]. |

Quantitative Impact of Structural Factors

The following table summarizes key structural and chemical factors and their documented impact on enzymatic hydrolysis efficiency, as identified in the literature.

| Factor | Description | Impact on Enzymatic Hydrolysis |

|---|---|---|

| Lignin Content | Total % of dry weight composed of lignin. | Generally strong negative correlation. Higher lignin content typically leads to lower sugar yields due to physical blocking and non-productive enzyme binding [11] [12]. |

| Cellulose Crystallinity | The proportion of crystalline vs. amorphous cellulose. | High crystallinity is a major contributor to recalcitrance, as enzymes primarily attack amorphous regions [11]. |

| Hemicellulose Content | Total % of dry weight composed of hemicellulose. | Its removal generally has a positive effect on cellulose conversion by increasing porosity and accessibility, though its own digestibility is important for total sugar yield [11]. |

| Acetyl Group Content | Degree of hemicellulose acetylation. | High acetyl content hinders hydrolysis, and its removal improves both hemicellulose and cellulose digestibility [11]. |

| Specific Surface Area | Pore volume and area accessible to enzymes. | A strong positive correlation exists between increased surface area and hydrolysis yield [11] [14]. |

| Biomass Porosity | The pore size and volume of the biomass particle. | A strong positive correlation exists between increased porosity and hydrolysis yield [16]. |

| S/G Ratio | Ratio of syringyl (S) to guaiacyl (G) units in lignin. | A higher S/G ratio is often correlated with improved digestibility, as S-lignin is less condensed and may be easier to remove [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Recalcitrance

Protocol: Large Field-of-View (LFOV) Microscopy for Particle Morphology Analysis

Objective: To visualize and quantify changes in biomass particle morphology and size distribution at different stages of pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis [16].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute pretreated or hydrolyzed biomass samples with distilled water to a low concentration (e.g., 10 μg dry mass/mL) to ensure individual particles are visible. Mount on a microscope slide and cover with a coverslip.

- Image Acquisition: Use a microscope capable of automated image stitching (e.g., Keyence VHX 5000). Acquire a grid of adjacent images (e.g., 17x11 tiles) at 200x magnification with a 30% overlap.

- Image Stitching: Use the microscope's software to automatically stitch all image tiles into a single, high-resolution Large Field-of-View (LFOV) image, typically around 20x10 mm².

- Particle Size Analysis:

- Process the LFOV image with a median filter to reduce noise.

- Apply intensity-based thresholding to segment particles from the background.

- Use particle analysis software (e.g., ImageJ "Analyze Particles" plugin) to measure the cross-sectional area and length of thousands of particles.

- Generate Particle Length Distributions (PLD) to statistically evaluate the effect of pretreatment severity and hydrolysis time.

Troubleshooting Tip: If particles are clumping, further dilute the sample. Ensure even illumination across the entire LFOV to avoid thresholding errors.

Protocol: Simons' Staining for Cellulose Accessibility

Objective: To quantitatively assess the accessibility of cellulose, which can be negatively impacted by drying-induced hornification [14].

Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Use model substrates (e.g., pure cellulose, holocellulose, native biomass) that have been subjected to different drying methods (freeze-dried, air-dried, oven-dried).

- Staining Solution: Prepare a solution of Direct Orange and Direct Blue dyes.

- Staining Process: Incubate a known weight of the substrate with the dye solution for a fixed time under controlled conditions.

- Quantification: Measure the amount of dye adsorbed by the substrate using spectrophotometry. The difference in adsorption between the two dyes provides a relative measure of accessible surface area.

Troubleshooting Tip: This assay can be performed on both "never-dried" and "dried" samples to directly quantify the loss of accessibility due to drying.

Visualizing the Recalcitrance Mechanism and Research Workflow

The Structural Fortress of Plant Cell Walls

This diagram illustrates the multi-scale, interlinked matrix of polymers that creates biomass recalcitrance.

Research Workflow for Overcoming Recalcitrance

This workflow outlines a multidisciplinary research approach to deconstruct the structural fortress.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function in Recalcitrance Research |

|---|---|

| Cellulase & Hemicellulase Enzymes | Multi-enzyme cocktails used in enzymatic hydrolysis to break down cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars. The choice of blend is crucial for conversion efficiency [16]. |

| Direct Orange & Direct Blue Dyes | Used in Simons' Staining to quantitatively assess the accessible surface area of cellulose in biomass samples, crucial for evaluating pretreatment efficacy [14]. |

| Clostridium thermocellum | A thermophilic, anaerobic bacterium capable of Consolidated Bioprocessing (CBP). It is studied for its high efficiency in solubilizing lignocellulose without added enzymes, offering a potential alternative to fungal enzyme systems [5]. |

| Alkaline Solution (e.g., NaOH) | A common chemical pretreatment agent that effectively solubilizes lignin and removes acetyl groups from hemicellulose, thereby reducing recalcitrance and improving enzyme accessibility [3] [17]. |

| Dilute Acid (e.g., H₂SO₄) | A common chemical pretreatment agent that primarily targets and hydrolyzes hemicellulose, increasing the porosity of the biomass structure for subsequent enzymatic attack [16] [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is biomass recalcitrance, and why is lignin a primary contributor? Lignocellulosic biomass is naturally resistant to microbial and enzymatic deconstruction, a property known as recalcitrance. Lignin, a complex aromatic polymer that provides structural integrity to plant cell walls, is a major contributor through two key mechanisms: it acts as a physical barrier, embedding cellulose and hemicelluloses to restrict enzyme access, and it causes non-productive binding, where enzymes irreversibly adsorb onto lignin instead of catalyzing sugar release [18] [11] [19].

Q2: How does the S/G ratio specifically influence enzymatic hydrolysis? The Syringyl (S) to Guaiacyl (G) ratio refers to the relative abundance of the two major monolignol units in lignin. A higher S/G ratio is generally associated with reduced biomass recalcitrance and improved sugar conversion. This is because G-lignin is more branched and forms stronger, more condensed carbon-carbon bonds (like β–5'), creating a robust network. S-lignin, with its methoxylated structure, forms more labile β-O-4' ether linkages, resulting in a less cross-linked and more easily deconstructed polymer [20] [21].

Q3: Can altering lignin composition avoid the yield penalty often seen in low-lignin plants? Yes, research indicates that engineering lignin composition, rather than simply reducing its content, is a promising strategy. Studies on Arabidopsis thaliana show that manipulating genes to create lignin highly enriched in S-subunits and derived from aldehydes can significantly improve cell wall digestibility without causing severe dwarfing, uncoupling the growth defects from desirable digestibility traits [20].

Q4: Besides the S/G ratio, what other lignin characteristics affect recalcitrance? The S/G ratio is one of several critical factors. Others include:

- Linkage Types: The abundance of easily cleaved β-O-4' linkages versus resistant C-C bonds [22] [21].

- Hydrophobicity and Functional Groups: Lignin with more condensed structures from harsh pretreatments is often more hydrophobic and has a greater affinity for non-productively binding enzymes [18] [19].

- Lignin Content: While composition is crucial, higher overall lignin content is still generally correlated with increased recalcitrance, as it enhances the physical barrier effect [12] [11].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Correlation Between S/G Ratio and Hydrolysis Efficiency Potential Cause and Solution: The relationship can be confounded by other cell wall factors. A high S/G ratio might not improve hydrolysis if the biomass also has a very thick fiber cell wall or a high degree of cellulose crystallinity. Actionable Steps:

- Comprehensive Characterization: Do not rely solely on the S/G ratio. Perform parallel analyses on your biomass samples, including measuring cellulose crystallinity index (CrI) via X-ray diffraction and visualizing cell wall morphology using microscopy [12].

- Use Model Systems: To isolate the effect of the S/G ratio, utilize natural genetic variants or engineered lines where the lignin content and other structural factors are similar [21].

Problem: Low Enzymatic Sugar Yield Despite High Delignification Potential Cause and Solution: Harsh pretreatment conditions may have removed lignin but also caused lignin repolymerization or condensation. This creates more hydrophobic lignin with a higher proportion of C-C bonds, which strongly inhibits enzymes. Actionable Steps:

- Analyze Lignin Structure: Use techniques like 2D HSQC NMR to characterize the interunit linkages (β-O-4', β-5', β–β') in the residual lignin after pretreatment [22].

- Employ Additives: Incorporate lignin-blocking additives like bovine serum albumin (BSA) or polyethylene glycol (PEG) into your hydrolysis mixture. These agents can occupy non-productive binding sites on lignin, freeing up cellulases for hydrolysis [19].

Problem: Unexpected Inhibition of Enzymatic Hydrolysis Potential Cause and Solution: The inhibition could stem from phenolic hydroxyl groups in lignin or from fermentation inhibitors (e.g., furfural) generated during pretreatment. Actionable Steps:

- Block Phenolic Groups: Experiment with chemical blocking of free phenolic hydroxyl groups, for example, through hydroxypropylation, which has been shown to significantly reduce the inhibitory effect of lignin [11].

- Assess Water-Soluble Lignins: Be aware that certain water-soluble lignins, like lignosulfonates, can sometimes promote hydrolysis by acting as surfactant-like agents. Test the effect of adding isolated lignins from your process to a pure cellulose hydrolysis assay to understand their role [18] [19].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Relationships

Table 1: Impact of Lignin Traits on Enzymatic Hydrolysis Efficiency

| Lignin Characteristic | Correlation with Glucose Yield | Experimental Basis | Magnitude of Effect Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| S/G Ratio | Generally Positive | Study of 11 Populus trichocarpa variants with similar lignin content showed a positive correlation with ethanol production [21]. | A higher S/G ratio was directly correlated with increased ethanol production. |

| Total Lignin Content | Generally Negative | Study on bamboo variants showed higher lignin content lowered deconstruction efficiency [12]. | H-L (21.0% lignin) vs. L-L (15.3% lignin) showed significantly different deconstruction efficiencies. |

| β-O-4' Linkage Content | Positive | NMR analysis of birch lignins showed this dominant ether linkage is more easily cleaved [22]. | Lignins with higher β-O-4' content are less recalcitrant. |

| Aldehyde-Rich Lignin | Positive | Arabidopsis mutants (cadd C4H-F5H) produced lignin from hydroxycinnamaldehydes, increasing digestibility [20]. | Mutant plants showed increased cellulose-to-glucose conversion. |

Table 2: Common Pretreatment Methods and Their Effects on Lignin

| Pretreatment Method | Primary Effect on Lignin | Impact on Enzymatic Digestibility | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaline (e.g., NaOH) | Efficiently removes lignin by cleaving ether bonds and disrupting structure [19]. | Significantly improves digestibility by removing physical barriers and adsorption sites. | Can generate wastewater; effective on agricultural residues. |

| Organosolv | Fractionates and extracts a relatively pure, often less condensed lignin stream [22]. | Greatly enhanced digestibility due to substantial delignification. | Organic solvent cost and recovery are key economic factors. |

| Sulfite Pretreatment | Sulfonates lignin, making it more hydrophilic and reducing its non-productive binding capacity [19]. | Improves hydrolysis yield by reducing enzyme inhibition. | |

| Extrusion-Biodelignification | Fungal enzymes (e.g., MnP) target lignin, leading to moderate delignification [23]. | Improved sugar recovery (e.g., 44% for corn stover). | Environmentally friendly; can be combined with physical methods like extrusion. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Lignin Content and Composition via NMR This protocol outlines the steps for extracting and analyzing lignin to determine the S/G ratio.

- Lignin Extraction (Organosolv Method):

- Reagent Solution: Prepare a mixture of ethanol and water (e.g., 60:40 v/v), with a small concentration of sulfuric acid (e.g., 0.1-1.0%) as a catalyst [22].

- Reaction: Load biomass powder into a reactor, add the reagent solution (solid-to-liquid ratio ~1:10), and heat to 150-200°C for 1-2 hours.

- Recovery: After cooling, filter the mixture to separate the solid cellulose-rich pulp. Precipitate the dissolved lignin by adding the filtrate to a large volume of cold water. Centrifuge and dry the lignin pellet.

- NMR Analysis (2D HSQC):

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve ~50 mg of the extracted lignin in a deuterated solvent like DMSO-d6.

- Data Acquisition: Run the 1H–13C HSQC NMR experiment on a suitable spectrometer.

- S/G Ratio Quantification: Identify and integrate the characteristic cross-signals: S-unit (C2,6-H2,6) at δC/δH 104/6.7 ppm and G-unit (C2-H2) at δC/δH 111/7.0 ppm. The S/G ratio is calculated from the integrated volumes [22] [21].

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Lignin on Enzymatic Hydrolysis This assay tests the inhibitory effect of isolated lignin on a standard hydrolysis reaction.

- Substrate Preparation: Use a pure cellulose substrate like Avicel PH-101.

- Lignin Introduction: Add isolated lignin (from your biomass or a commercial source) to the hydrolysis reaction at a known concentration (e.g., 10 mg/mL) [18].

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis:

- Buffer: Use sodium acetate buffer (50 mM, pH 4.8).

- Enzymes: Add a commercial cellulase cocktail (e.g., CTec2) at a standard loading (e.g., 10-20 FPU/g cellulose).

- Controls: Run parallel reactions with pure Avicel (positive control) and Avicel with added lignin.

- Conditions: Incubate at 50°C with agitation for 24-72 hours.

- Analysis: Quantify the released glucose using the DNS method or HPLC. Compare glucose yields to determine the percentage inhibition caused by lignin [19].

Visual Workflows and Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Lignin Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol-Water Mixtures | Primary solvent for organosolv pretreatment, effectively fractionates lignin from biomass [22]. | Commonly used in 60-80% ethanol concentration; may be acid-catalyzed with H2SO4. |

| Deuterated Solvents | Essential for NMR spectroscopy to determine lignin structure and S/G ratio [22] [21]. | DMSO-d6 is frequently used for solubilizing lignin samples for 2D HSQC NMR. |

| Lignin-Blocking Additives | Surfactants or proteins that reduce non-productive enzyme binding to lignin, boosting hydrolysis yield [19]. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Tween 80. |

| Commercial Cellulase Cocktails | Enzyme mixtures for enzymatic hydrolysis assays to quantify sugar release and recalcitrance [19] [23]. | CTec2, HTec2; loading is typically in Filter Paper Units (FPU) per gram of cellulose. |

| Manganese Peroxidase (MnP) | Fungal enzyme used in biological pretreatments to depolymerize and remove lignin [23]. | Key enzyme in extrusion-biodelignification processes for sustainable pretreatment. |

Lignocellulosic biomass (LB) serves as a renewable reservoir for biofuel and biobased chemical production, yet its inherent recalcitrance poses a significant economic and technical bottleneck for biorefineries [24]. This recalcitrance is primarily governed by the structural and chemical complexity of the plant cell wall, where cellulose microfibrils are embedded within a matrix of hemicellulose and lignin [25]. Among these factors, the crystallinity of cellulose and its degree of polymerization (DP) are two critical structural parameters that severely limit the enzymatic accessibility of cellulose, thereby reducing the efficiency of saccharification [26] [27]. This technical support article, framed within a thesis on overcoming biomass recalcitrance, provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers optimize their experimental systems for enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis.

Core Concepts: Crystallinity and Degree of Polymerization

What are Cellulose Crystallinity and Degree of Polymerization?

Cellulose Crystallinity refers to the proportion of cellulose that exists in a highly ordered, crystalline structure, as opposed to a disordered, amorphous state. Within cellulose microfibrils, crystalline regions, where cellulose chains are packed tightly via hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces, alternate with less-ordered amorphous regions [28]. The Crystallinity Index (CrI) is a common metric used to quantify this property.

Degree of Polymerization (DP) is the number of anhydroglucose units in a single cellulose polymer chain. Native cellulose can have a DP ranging from approximately 1,000 to 30,000, depending on its source [28] [24].

How Do Crystallinity and DP Impact Enzymatic Hydrolysis?

The tightly packed crystalline regions of cellulose are inaccessible to microbial cellulolytic enzymes. Enzymatic hydrolysis primarily occurs on the surface of the cellulose fibrils, and a high CrI means less accessible surface area for enzymes to bind and act upon [27] [24]. Furthermore, the dense hydrogen-bonding network in crystalline cellulose makes the glycosidic bonds more resistant to enzymatic cleavage.

A high DP implies long cellulose chains with more intra- and inter-chain hydrogen bonds, which are difficult to hydrolyze. Shorter cellulose chains (lower DP) have a weaker hydrogen-bonding network, which is believed to facilitate enzyme accessibility [24]. Research has demonstrated that reducing the DP and CrI of microcrystalline cellulose significantly enhances its digestibility by cellulase enzymes and its fermentability by human fecal microbiota, showcasing the potential of engineering these properties for improved conversion [26].

The following diagram illustrates how the structural properties of cellulose limit enzymatic hydrolysis and how pretreatment strategies can overcome this recalcitrance.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: Addressing Challenges in Measuring and Interpreting Crystallinity

Q1: Why do I get different crystallinity values when using different measurement techniques (e.g., XRD vs. FT-IR)?

- Cause: Different techniques probe different aspects of the "crystalline" and "amorphous" phases, and there is a lack of universal standards for these phases [29]. For instance:

- XRD (X-ray Diffraction): The most common method (e.g., Segal method) provides a rough approximation of CrI but does not account for the actual maximum of the amorphous peak, leading to potential inaccuracies [28].

- FT-IR (Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy): Empirical methods using band ratios (e.g., A1429/A893) are highly sensitive to sample thickness, density, and measurement conditions, and suffer from overlapping spectral contributions [28].

- NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance): While powerful, its accuracy is influenced by the ability to deconvolute overlapping peaks and the lateral size of the crystallites [28].

- Solution:

- Consistency is Key: Use the same technique and sample preparation method for comparative studies.

- Cross-Validation: Where possible, use a secondary technique to validate your trends. For example, a recent study successfully used machine learning with FT-IR data to predict CrI, achieving strong agreement with XRD measurements [28].

- Report Methodology: Always explicitly state the technique and calculation method used when reporting CrI values.

Q2: My pretreatment successfully reduced crystallinity, but the enzymatic hydrolysis yield is still low. What could be the reason?

- Cause 1: Lignin Redeposition. During certain thermochemical pretreatments, lignin can soften and redeposit on the cellulose surface, creating a new physical barrier that blocks enzyme access [30] [24].

- Troubleshooting: Analyze the lignin content and distribution post-pretreatment. Consider adding surfactant additives (e.g., Tween, PEG) or non-catalytic proteins (e.g., BSA, soybean protein) to block non-productive binding of cellulases to lignin [30].

- Cause 2: Inadequate Pore Accessibility. Reducing crystallinity may not be sufficient if the pores within the biomass structure are not large enough to accommodate cellulase enzymes, which are relatively large proteins.

- Troubleshooting: Perform a porosity analysis (e.g., solute exclusion). Ensure your pretreatment effectively increases the cell wall pore size.

- Cause 3: Inadequate Synergy in Enzyme Cocktail. A low CrI increases the number of amorphous regions, which are primary targets for endoglucanases (EGs). If your enzyme cocktail is deficient in EGs, the beneficial effect of reduced crystallinity will not be fully realized.

- Troubleshooting: Optimize the ratio of endoglucanases (EGs), cellobiohydrolases (CBHs), and β-glucosidases (BGLs) in your hydrolysis experiment. Consider adding lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs) that can disrupt crystalline surfaces [25].

FAQ: Addressing Challenges with Degree of Polymerization

Q3: What is the most reliable method to determine the DP of cellulose after a harsh pretreatment?

- Challenge: Harsh pretreatments can functionalize cellulose (e.g., introduce carboxyl groups) or leave behind residual chemicals that interfere with classical viscometric methods.

- Solution:

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): This is a highly effective method for determining molecular weight distribution and average DP. It separates cellulose fragments (often after carboxymethylation to improve solubility) based on hydrodynamic volume [31]. A key advantage is the ability to use absolute detection methods (e.g., with multi-angle light scattering), eliminating the need for calibration with polymer standards that have different structures [31] [32].

- Protocol Summary for SEC: [31]

- Solubilization: Dissolve or derivatize the cellulose sample. For underivatized cellulose, this may require solvents like ionic liquids or cupriethylenediamine.

- Separation: Inject the solution into an SEC system equipped with a suitable column (e.g., Superose 12 HR).

- Detection & Analysis: Use detectors for concentration (e.g., Refractive Index) and molecular weight (e.g., Multi-Angle Light Scattering). The DP is calculated from the molecular weight by dividing by the mass of an anhydroglucose unit (162 g/mol).

Q4: I am observing a reduction in DP after pretreatment, but the hydrolysis rate did not improve. Is this a contradiction?

- Cause: Interplay of Factors. The enzymatic hydrolysis rate is not governed by DP alone. It is possible that your pretreatment reduced the DP but concurrently increased factors that inhibit hydrolysis, such as:

- Lignin Content/Structure: The pretreatment may have increased the exposure of lignin without removing it, leading to higher non-productive enzyme binding [24].

- Particle Size/Aggregation: Larger particle sizes or re-aggregation of cellulose chains can still limit surface area accessibility, negating the benefit of lower DP.

- Inhibition: The pretreatment may have generated fermentation inhibitors (e.g., furans, phenolic compounds) that also inhibit cellulase activity [24].

- Solution: Perform a comprehensive characterization of your pretreated biomass. Analyze lignin content, surface area/porosity, and the presence of inhibitors alongside DP to identify the true limiting factor.

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Impact of Crystallinity and DP on Digestibility and Fermentation

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from a study that engineered cellulose with varying crystallinity and DP, demonstrating their significant impact on biological conversion [26].

Table 1: Impact of Engineered Cellulose Properties on Enzymatic Conversion and Colonic Fermentation [26]

| Cellulose Sample | Average DP | Crystallinity Index (CrI) (%) | Enzymatic Conversion (EC) (%) | SCFA Production (Increase vs. MC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcrystalline Cellulose (MC) | >100 | High | Baseline | Baseline |

| Amorphized Cellulose (AC) | >100 | < 30% | Increased | Not Specified |

| Depolymerized Cellulose (DC) | < 100 | High | Increased | Not Specified |

| Amorphized & Depolymerized Cellulose (ADC) | < 100 | < 30% | Highest | > 8-fold increase |

Standard Protocols for Key Measurements

Protocol 1: Determining Crystallinity Index (CrI) via X-ray Diffraction (XRD) [26] [28]

- Sample Preparation: Grind the cellulose sample to a fine, homogeneous powder. Pack uniformly into a sample holder.

- Data Acquisition: Use an X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation. Scan a 2θ range from about 5° to 40°.

- CrI Calculation (Segal Method):

- Measure the intensity of the 200 lattice diffraction peak (I~200~), typically around 22.5°.

- Measure the intensity of the minimum between the 200 and 110 peaks (I~AM~), typically around 18°.

- Calculate the CrI using the formula: CrI (%) = [(I~200~ - I~AM~) / I~200~] × 100

Protocol 2: Determining Degree of Polymerization (DP) via Viscometry [26]

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve 0.075 g of dry cellulose in 15 mL of 0.5 M bis(ethylenediamine)copper(II) hydroxide solution.

- Viscosity Measurement: Measure the flow time of the solution at 25°C using a capillary viscometer. Also, measure the flow time of the pure solvent.

- DP Calculation:

- Calculate the specific viscosity: η~sp~ = (t~solution~ - t~solvent~) / t~solvent~

- The intrinsic viscosity [η] is determined from η~sp~.

- The average DP is calculated using the Mark-Houwink equation: DP = ([η] / K)^(1/α) where K and α are empirical constants (e.g., K = 7.5 × 10⁻³ and α = 1 for the solvent used above).

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps for preparing and analyzing cellulose samples to overcome recalcitrance, integrating the protocols discussed above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Cellulose Accessibility Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microcrystalline Cellulose | A standard, highly crystalline cellulose substrate for baseline experiments and as a crystalline standard for CrI measurement. | Avicel PH-101 [26] [28] |

| Cellulase Enzyme Cocktail | A mixture of hydrolytic enzymes for saccharification assays. Contains endoglucanases, cellobiohydrolases, and β-glucosidases. | Cellic CTec2 blend [26] |

| Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenase (LPMO) | An accessory enzyme that oxidatively cleaves crystalline cellulose, boosting the activity of classic cellulases. | Often included in advanced commercial cocktails [25] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) / Soybean Protein | Additives used to block the non-productive binding of cellulases to lignin in lignocellulosic substrates. | Reduces enzyme loading requirements; improves hydrolysis yield [30] |

| Non-ionic Surfactants | Additives that reduce surface tension, improve enzyme stability, and prevent unproductive enzyme binding. | Tween 80, PEG [30] |

| Ball Mill | Equipment for mechanical pretreatment to disrupt cellulose crystallinity (amorphization) and reduce particle size. | Planetary ball mill with zirconium oxide balls [26] |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) System | Analytical system for determining the molecular weight distribution and average DP of (derivatized) cellulose. | Requires a suitable column (e.g., Ultra-hydrogel) and detectors (RI, MALS) [31] [32] |

FAQs: Understanding the Role of Hemicellulose and Acetyl Groups

Q1: How do hemicellulose and its acetyl groups contribute to biomass recalcitrance?

Hemicellulose and its acetyl groups are significant contributors to biomass recalcitrance through multiple mechanisms. Hemicellulose forms a cross-linked matrix with cellulose and lignin, creating a physical barrier that blocks cellulase enzymes from accessing cellulose fibers [11] [33]. The acetyl groups attached to hemicellulose chains further exacerbate this problem by sterically hindering enzyme access to glycosidic bonds and increasing the hydrophobicity of the polysaccharide surface, which disrupts productive binding between cellulose and the catalytic domain of cellulases [11] [34]. Studies on corn stover, poplar, and spruce have confirmed that reducing acetyl content improves enzymatic hydrolysis effectiveness [11] [35].

Q2: Why does enzymatic hydrolysis efficiency sometimes decrease after alkaline pretreatment that removes acetyl groups?

This apparent contradiction can be explained by recent research on spruce mannan. While alkaline pretreatment removes acetyl groups (deacetylation), it can sometimes intensify hydrolysis inhibition. One study found that deacetylated galactoglucomannan (DGM) increased hydrolysis inhibition up to 41.95%, while highly acetylated galactoglucomannan (AGM) significantly alleviated inhibition, reducing it by 76.44% [35]. This suggests that a controlled level of acetylation might maintain hemicellulose in a more open or accessible conformation, whereas complete deacetylation may increase non-productive binding between enzymes and the polysaccharide backbone. The optimal level of acetylation appears to depend on biomass source and pretreatment conditions.

Q3: What experimental approaches can distinguish between the physical barrier effect of hemicellulose and the inhibitory effect of acetyl groups?

Researchers can employ several approaches to distinguish these effects:

- Sequential extraction with increasing alkali concentrations to gradually remove hemicelluloses with varying acetylation patterns while monitoring enzymatic hydrolysis rates [33].

- Comparative adsorption studies using native, deacetylated, and highly acetylated hemicellulose polymers to measure their capacity to non-productively adsorb cellulases [35].

- Structural characterization techniques including FTIR and NMR spectroscopy to correlate acetylation levels with enzymatic digestibility [35].

- Use of specific esterases (e.g., acetyl xylan esterases) that remove acetyl groups without significantly altering the hemicellulose backbone, allowing researchers to isolate the acetyl-specific effects [34].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent enzymatic hydrolysis results after hemicellulose-directed pretreatments.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Variable acetyl group retention | FTIR analysis for C=O stretch at 1740 cm⁻¹ [35] | Standardize pretreatment severity and post-washing protocols |

| Incomplete hemicellulose removal | Compositional analysis for monosaccharides [33] | Optimize pretreatment temperature, duration, and catalyst concentration |

| Non-productive enzyme binding | Protein assay on supernatant post-hydrolysis [36] | Add blocking agents (BSA) or surfactants to reduce non-specific binding |

| Lignin-hemicellulose complexes | Immunohistochemistry with specific antibodies | Incorporate mild oxidative steps to disrupt lignin-carbohydrate complexes |

Problem: Poor efficiency of commercial enzyme cocktails on specific biomass feedstocks.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient accessory enzymes | Analyze enzyme cocktail composition | Supplement with hemicellulases (xylanase, mannanase) and carbohydrate esterases [34] |

| Inhibition by solubilized compounds | Measure release of phenolic compounds and organic acids | Incorporate detoxification steps (overliming, adsorption) |

| Suboptimal reaction conditions | pH and temperature profiling | Adjust conditions to optimal ranges for specific enzyme combinations |

| Mass transfer limitations | Particle size analysis and porosity measurements | Implement mechanical pretreatment (e.g., milling) to improve accessibility [36] |

Impact of Acetyl Content on Enzymatic Hydrolysis

| Biomass Type | Acetyl Content (% w/w) | Saccharification Yield (%) | Experimental Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spruce GGM (Natural) | Not specified | Inhibition: 17.66-26.64% | 2-8 mg/mL, Cellulase CTec2 | [35] |

| Spruce GGM (Deacetylated) | Reduced | Inhibition: ↑ to 41.95% | 8 mg/mL, Cellulase CTec2 | [35] |

| Spruce GGM (Highly acetylated) | Increased | Inhibition: ↓ by 76.44% | 2 mg/mL, Cellulase CTec2 | [35] |

| Ryegrass (Alkaline extracted) | Reduced | 72.3-95.3% | Sequential NaOH (0.15-2.5%), Cellulase | [33] |

Effectiveness of Different Pretreatment Methods on Hemicellulose Removal

| Pretreatment Method | Hemicellulose Removal Efficiency | Key Mechanisms | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaline Extraction | High (30.3% to 19.2% content) [33] | Saponification of ester bonds, swelling | Chemical cost, waste stream generation |

| Autohydrolysis | Moderate to High | Acetic acid catalysis from acetyl groups | Equipment corrosion, inhibitor formation |

| Dilute Acid | High | Glycosidic bond hydrolysis | Equipment corrosion, inhibitor formation |

| Metal Salt + Mechanical | Variable [36] | Coordination with hydroxyl groups, hydrogen bond disruption | Milling energy intensity, salt recovery |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Acetyl Group Impact Using Model Hemicelluloses

Purpose: To systematically evaluate how acetylation level affects enzymatic hydrolysis efficiency.

Materials:

- Native hemicellulose (e.g., spruce galactoglucomannan)

- Alkaline solution (0.1M NaOH) for deacetylation

- Acetic anhydride for acetylation

- Microcrystalline cellulose (Avicel PH-101)

- Commercial cellulase (e.g., CellicCTec2)

- DNS reagent for sugar analysis

- FTIR spectrometer

Procedure:

- Prepare hemicellulose variants:

- Native: Use without modification

- Deacetylated (DGM): Treat with 0.1M NaOH at 25°C for 4h, neutralize, dialyze, and lyophilize

- Highly acetylated (AGM): React with acetic anhydride in pyridine (1:1, v/v) at 80°C for 2h, precipitate in ethanol, wash, and dry [35]

Verify acetylation levels:

- Analyze by FTIR: acetyl groups show characteristic C=O stretch at 1740 cm⁻¹

- Confirm by NMR spectroscopy for quantitative assessment [35]

Hydrolysis assays:

- Set up reactions with 2% (w/v) Avicel and hemicellulose variants (2-8 mg/mL)

- Add cellulase (10-20 FPU/g cellulose) in citrate buffer (pH 4.8)

- Incubate at 50°C with shaking (150 rpm) for 72h

- Sample at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72h for sugar analysis by HPLC or DNS method [35]

Adsorption studies:

- Incubate cellulase with hemicellulose variants for 1h at 4°C

- Centrifuge and measure protein in supernatant

- Calculate adsorbed enzyme [35]

Protocol 2: Sequential Alkaline Extraction for Hemicellulose Removal

Purpose: To gradually remove hemicelluloses and correlate removal with enzymatic digestibility.

Materials:

- Delignified biomass (e.g., ryegrass after peroxide treatment)

- Sodium hydroxide solutions (0.15%, 0.3%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0%, 2.5%)

- Ethanol for precipitation

- Centrifuge

- Freeze dryer

Procedure:

- Perform sequential extractions:

- Treat delignified biomass (5g) with 0.15% NaOH (100mL) at 80°C for 2h with stirring

- Filter through sintered glass funnel, collect solid (R0.15%)

- Wash solid with distilled water and dry at 60°C

- Repeat with next higher NaOH concentration on subsequent solid fractions [33]

Recover hemicellulose fractions:

- Neutralize combined filtrates with acetic acid

- Precipitate hemicelluloses by adding 3 volumes ethanol

- Centrifuge, wash precipitate with 70% ethanol

- Freeze-dry for further analysis [33]

Characterize solid fractions:

- Analyze chemical composition for residual hemicellulose

- Determine crystallinity by XRD

- Perform enzymatic hydrolysis to assess digestibility [33]

Characterize hemicellulose fractions:

- Determine monosaccharide composition by acid hydrolysis+HPLC

- Measure molecular weight by SEC-MALLS

- Analyze acetylation level by NMR [33]

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Recalcitrance Research |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Acetyl xylan esterase (CE family) [34] | Specifically removes acetyl groups from hemicellulose without degrading backbone |

| Mannanase [35] | Targets mannan-based hemicelluloses prevalent in softwoods | |

| Xylanase | Hydrolyzes xylan backbone, predominant in hardwoods | |

| Chemical Pretreatment Agents | Sodium hydroxide [33] | Saponifies ester linkages, removes acetyl groups and hemicellulose |

| Metal salts (AlCl₃, FeCl₃) [36] | Disrupts hydrogen bonding networks, synergistic with mechanical action | |

| Analytical Tools | Monoclonal antibodies (LM10, LM11) | Specific detection of hemicellulose epitopes in cell walls |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Rapid assessment of acetyl groups (C=O stretch at 1740 cm⁻¹) [35] | |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Quantitative determination of acetylation patterns [35] |

Experimental and Mechanism Visualizations

Hemicellulose Acetylation Impact

Sequential Alkaline Extraction Workflow

Breaking Down the Walls: A Toolkit of Pretreatment Strategies

Fundamental Concepts & Troubleshooting

FAQ: What is "biomass recalcitrance" and why is it the central challenge in my work? Biomass recalcitrance is the natural resistance of plant cell walls to microbial and enzymatic deconstruction [10]. This property, evolved in plants to protect against pathogens, is the primary reason for the high cost of converting lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars [10]. Your pretreatment aims to overcome this recalcitrance.

FAQ: My enzymatic hydrolysis yields are low after pretreatment. What could be the cause? This is a common issue often traced to two main factors:

- Inadequate Lignin Removal: Lignin acts as a physical barrier and can non-productively adsorb enzymes, preventing them from reaching cellulose. Check if your pretreatment method effectively reduces lignin content [37].

- Inhibitor Formation: Harsh pretreatment conditions can generate fermentation inhibitors like furans and phenolic compounds. Analyze your hydrolysate for these inhibitors and consider optimizing pretreatment severity or introducing a detoxification step [37].

FAQ: How do I choose the best pretreatment method for my specific biomass feedstock? There is no single "best" method. The choice involves trade-offs between efficiency, cost, and environmental impact. Selection should be based on [37] [38]:

- Feedstock Composition: High-lignin biomass may require robust methods like alkali or organosolv, while high-hemicellulose biomass may respond well to dilute acid.

- Downstream Process Compatibility: Consider the sugar stream's purity needs for your fermentation organisms.

- Economic and Environmental Sustainability: Evaluate the method's energy consumption, chemical cost, and waste stream generation.

Pretreatment Methodologies & Data

The table below summarizes the core operational parameters for common pretreatment methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Leading Pretreatment Methodologies

| Pretreatment Method | Core Function | Standard Operating Parameters | Key Advantages | Reported Challenges / Failure Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilute Acid | Hydrolyzes hemicellulose, disrupts lignin structure. | 0.5 - 2.5% H2SO4; 140 - 200°C; 5 - 30 min [38]. | High xylose yield, effective on wide range of biomass. | Equipment corrosion, formation of inhibitory compounds (furfural, HMF) [38]. |

| Steam Explosion | Autohydrolysis through heating and rapid decompression. | 160 - 260°C; 0.69 - 4.83 MPa; 1 - 20 min [38]. | Low environmental impact, no recycling costs. | Partial hemicellulose degradation, generation of inhibitors if conditions are too severe. |

| Ammonia Fiber Explosion (AFEX) | Cleaves lignin-hemicellulose bonds, decrystallizes cellulose. | Liquid ammonia (1-2 kg/kg biomass); 60 - 120°C; 5 - 30 min [37]. | Low inhibitor formation, high sugar recovery. | High ammonia cost and recycling energy. |

| Alkaline (e.g., NaOH) | Solubilizes lignin, disrupts ester bonds. | 0.5 - 4% NaOH; 25 - 120°C; 10 min - 6 hrs. | Effective delignification, operates at lower temperatures. | Long residence times, salt formation requiring washing. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Dissolves lignocellulose by breaking hydrogen bonds. | Varies by IL; 90 - 130°C; 1 - 24 hrs [37]. | High biomass solvation, tunable solvent properties. | High cost, potential toxicity, requires near-complete solvent recovery. |

Common Experimental Failures & Solutions

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Pretreatment Batches

- Potential Cause 1: Inhomogeneous Biomass Particle Size.

- Solution: Implement a standardized milling and sieving protocol. Use a vibratory sieve shaker to obtain a narrow particle size distribution (e.g., 250-500 μm) before pretreatment.

- Potential Cause 2: Fluctuating Reaction Temperature.

- Solution: Regularly calibrate your heating mantles, oil baths, or reactor temperature probes. Use a reactor with a high-quality PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) temperature controller to maintain stability.

Problem: Rapid Equipment Deterioration or Blockage

- Potential Cause: Abrasive Mineral Impurities (e.g., silica) and Corrosive Media.

- Solution: This is a major industrial challenge [38]. Incorporate a biomass washing or cleaning step prior to loading. For lab-scale acidic pretreatments, use reactors lined with Hastelloy or Teflon to resist corrosion.

Problem: Poor Mass Balance Closure After Pretreatment (>10% Loss)

- Potential Cause: Unaccounted Soluble Oligomers or Volatile Compounds.

- Solution: Ensure you are analyzing both the solid pretreated biomass (for glucan, etc.) and the liquid hydrolysate. Perform a post-hydrolysis (e.g., with 4% H2SO4 at 121°C for 1 hour) on the liquid fraction to convert soluble oligomers into monomeric sugars for analysis.

Advanced Techniques & Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Pretreatment |

|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Sustainable solvents, often choline chloride-based, that effectively fractionate lignin and hemicellulose with low volatility and toxicity [37]. |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [EMIM][OAc]) | Powerful solvents that disrupt cellulose crystallinity and dissolve biomass, enabling high-yield enzymatic hydrolysis [37]. |

| Glycosyl Hydrolase Enzymes | Multi-enzyme cocktails (cellulases, xylanases, etc.) used post-pretreatment to hydrolyze polysaccharides into fermentable sugars [37]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational models used to design and optimize microbial strains for the fermentation of complex sugar streams generated from pretreatment [37]. |

Emerging Methodology: Machine Learning for Biomass Analysis Machine learning (ML) models, such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), are now being used to predict the concentrations of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin in biomass based on rapid, low-cost proximate analysis data, reducing reliance on expensive and slow wet chemistry methods [39]. These models have demonstrated high accuracy, with determination coefficients (R²) exceeding 0.96 [39].

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for diagnosing and resolving common pretreatment failures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is biomass recalcitrance, and why is it the central challenge that pretreatment aims to overcome?

Biomass recalcitrance refers to the natural resistance of plant cell walls to being broken down into simpler sugars. This resistance is due to the complex and robust matrix of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [3]. Think of it as a strong, naturally evolved defense mechanism. Lignin acts as a waterproof, durable sealant that physically blocks access to cellulose and hemicellulose and can deactivate enzymes [3] [40]. Effective pretreatment is crucial for disrupting this structure, making cellulose accessible for enzymatic hydrolysis, and enabling efficient biofuel production [41] [42].

FAQ 2: Among Liquid Hot Water (LHW) and Steam Explosion (SE), which is more environmentally friendly?

Both methods are considered greener than many chemical pretreatments, but they have different environmental profiles:

- Liquid Hot Water (LHW): It is highlighted for its eco-friendly nature as it uses only water, no added chemicals, which reduces pollution and production costs [41] [43]. A life cycle assessment indicated that LHW improves long-term energy security and creates a "greener future" [41].

- Steam Explosion (SE): This method is also regarded as environmentally friendly and requires lower energy inputs compared to some processes [41]. However, it can contribute to the formation of toxic compounds like furans and phenolics, which may require additional washing steps [41] [40].

FAQ 3: How do additives like 2-naphthol improve the Steam Explosion pretreatment, especially for recalcitrant feedstocks like softwood?

Additives known as "carbocation scavengers" can significantly enhance SE effectiveness. During pretreatment, acidic conditions lead to the formation of lignin carbocations, which tend to repolymerize into a barrier that is even more recalcitrant and has a high affinity for adsorbing and deactivating enzymes [44]. Additives like 2-naphthol scavenge these carbocations, preventing lignin repolymerization [44]. This results in a modified lignin structure with a reduced potential for enzyme deactivation. Pilot-scale studies have shown that impregnating spruce wood chips with 2-naphthol can dramatically enhance enzymatic cellulose digestibility, making the conversion of challenging softwoods much more efficient [44].

FAQ 4: What are the common inhibitors formed during these pretreatments, and how do they hinder downstream processes?

The high-temperature conditions of LHW and SE can lead to the degradation of sugar polymers and lignin, generating by-products that act as inhibitors [40]. Common inhibitors include:

- Furfural and 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF): Formed from the dehydration of pentose and hexose sugars, respectively [40].

- Acetic Acid: Released from the acetyl groups of hemicellulose [40].

- Phenolic Compounds: Derived from lignin degradation [40]. These inhibitors can suppress enzyme activity during saccharification, disrupt the cell membranes of fermenting microorganisms, and lead to microbial mutation, ultimately reducing the yield of the desired bioresource [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Sugar Yield After Pretreatment and Hydrolysis

| Symptom & Problem | Proposed Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Low glucose yield from cellulose.Problem: Ineffective delignification; lignin barrier remains and non-productively binds enzymes. | Consider incorporating a carbocation scavenger (e.g., 2-naphthol) into the SE process [44]. Alternatively, combine with a mild alkaline wash post-pretreatment to dissolve lignin. | Prevents lignin repolymerization during pretreatment, leading to a modified lignin that adsorbs fewer enzymes [44]. Alkaline solutions are effective at solubilizing lignin [45]. |

| Low xylose yield from hemicellulose.Problem: Hemicellulose not sufficiently hydrolyzed, or severity is too high, degrading sugars into inhibitors. | For LHW, optimize temperature and time toward milder severity (e.g., 160-180°C). Use a controlled pH (4-7) to favor hemicellulose hydrolysis into oligomers over degradation [41]. | Lower severity and controlled pH promote the dissolution of hemicellulose into valuable oligosaccharides like XOS, while minimizing the formation of furfural [41] [43]. |

| High inhibitor concentration (Furfural, HMF, Phenolics).Problem: Pretreatment severity (temperature/time) is too high. | 1. Reduce pretreatment temperature and/or time.2. Implement a detoxification step: Over-liming, adsorption with activated carbon, or enzymatic detoxification [40]. | High temperatures and long residence times promote sugar degradation and lignin decomposition into inhibitory compounds [41] [40]. Detoxification steps remove or transform these inhibitors. |

| Poor hydrolysis despite good composition.Problem: Inadequate particle size reduction or insufficient accessibility for enzymes. | For SE, ensure the explosion step is effective. For LHW, consider a mechanical refining step (e.g., ball milling) after pretreatment to further increase surface area [45]. | The explosive decompression in SE reduces particle size physically. Mechanical pretreatment increases surface area and reduces cellulose crystallinity, enhancing enzyme accessibility [44] [45]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Pretreatment Process Operation

| Symptom & Problem | Proposed Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| High energy consumption.Problem: Process is energy-intensive, affecting economic viability. | Explore a combined pretreatment strategy (e.g., mechanical comminution before LHW/SE) to reduce the severity and energy demand of the main step [45]. Prioritize SE for its generally lower energy input [41]. | Combined methods can have synergistic effects, allowing for less severe conditions in each step while maintaining effectiveness, thus reducing overall energy consumption [45]. |

| Formation of toxic compounds in SE.Problem: Generation of inhibitors hinders fermentation. | Optimize severity factor. As a process solution, introduce a washing step post-pretreatment to remove inhibitors from the solid fraction before enzymatic hydrolysis [41] [40]. | While catalyst-free SE can generate inhibitors, optimizing operational parameters and physically removing soluble inhibitors can mitigate their negative impact on downstream processes [41]. |

| Ineffective pretreatment of softwood (e.g., spruce).Problem: High softwood recalcitrance is not overcome by standard SE. | Impregnate the biomass with a carbocation scavenger like 2-naphthol (using a solvent like ethanol) prior to SE pretreatment [44]. | This approach specifically addresses the unique lignin repolymerization issue in softwoods, drastically improving enzymatic digestibility without requiring an acid catalyst [44]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Liquid Hot Water (LHW) Pretreatment

Objective: To solubilize hemicellulose and disrupt the lignin structure, thereby enhancing the enzymatic digestibility of the cellulose-rich solid residue.

Materials:

- Reactor: High-pressure stainless steel reactor capable of withstanding temperatures up to 240°C and corresponding pressures.

- Biomass: Milled lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn cobs, straw), particle size 1-5 mm.

- Reagent: Deionized water.

Methodology:

- Loading: Charge the reactor with biomass and deionized water at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 to 1:20 (w/v) [41].

- Reaction: Heat the reactor to the target temperature (typical range 160-240°C) and maintain for a specified residence time (typically 5-60 minutes) [41] [43].

- Cooling: Rapidly cool the reactor to room temperature using a cooling loop or ice bath to terminate the reaction.

- Separation: Separate the slurry into a solid fraction (cellulose-rich) and a liquid fraction (hemicellulose-derived sugars and solubilized lignin) via filtration or centrifugation.

- Analysis: Wash the solid fraction and analyze its chemical composition. The solid can then be subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis. The liquid fraction can be analyzed for sugar oligomers, monomers, and inhibitors.

Typical Outcome: For corn cobs treated at 160°C for 10 minutes, one can expect a maximum pentose yield of 58.8% in the liquid fraction, removal of more than 60% of lignin from the solid fraction, and a 73.1% glucose yield during subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis [41].

Protocol 2: Steam Explosion Pretreatment with 2-Naphthol Additive for Softwood

Objective: To overcome the high recalcitrance of softwood by preventing lignin repolymerization, thereby achieving high enzymatic cellulose conversion.

Materials:

- Reactor: Pilot-scale steam explosion reactor (e.g., 5.8 L volume) [44].

- Biomass: Spruce wood chips (approx. 30 mm screen size).

- Reagents: 2-Naphthol (≥98% purity), Ethanol or Acetone (for impregnation).

Methodology:

- Additive Preparation (Impregnation):

- Dissolve 35.36 g of 2-naphthol in 5 L of ethanol to completely cover 1.5 kg of spruce wood chips [44].

- Allow the solvent to evaporate completely at room temperature in a fume hood (may take 3 days for ethanol). Ensure frequent mixing for even impregnation.

- Air-dry the impregnated wood chips for several weeks to ensure total solvent removal.

- Pretreatment:

- Load the 2-naphthol-impregnated wood chips into the steam gun reactor.

- Treat with saturated steam at the desired temperature and pressure (e.g., 215°C for 5 minutes) [44].

- Initiate explosive decompression to discharge the biomass.

- Analysis: Collect the pretreated material. The enzymatic digestibility of the cellulose in the washed solid residue can be tested. This method has been shown to enable a complete enzymatic cellulose conversion for spruce, which is remarkable for a process that does not remove lignin [44].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: This workflow illustrates the parallel paths of LHW and SE pretreatment. The key differentiator is the use of additives like 2-naphthol in SE specifically to tackle the extreme recalcitrance of softwoods, leading to a cellulose-rich solid for sugar production and a liquid stream for valuable co-products.

Diagram 2: This diagram details the chemical mechanism at play. The acidic conditions of pretreatment create reactive lignin carbocations. Without an additive, these repolymerize into a more recalcitrant structure. A scavenger additive intercepts this pathway, yielding a less inhibitory lignin and significantly boosting hydrolysis efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Advanced Pretreatment

| Reagent/Material | Function in Pretreatment | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Naphthol | Functions as a carbocation scavenger. It reacts with reactive lignin intermediates during pretreatment, preventing their repolymerization into a recalcitrant structure [44]. | Critical for enhancing the SE pretreatment of softwoods (e.g., spruce). Best applied via solvent impregnation (using ethanol) for even distribution [44]. |

| Dilute Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | Acts as an acid catalyst to enhance hemicellulose hydrolysis and improve the overall disruption of the lignocellulosic matrix. | Commonly used in catalyzed SE to improve sugar yields. Drawbacks include equipment corrosion and potential for higher inhibitor generation [41] [40]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | An alkaline agent used for delignification. It solubilizes lignin by breaking ester and glycosidic bonds, significantly increasing cellulose accessibility [45]. | Often used in combined pretreatment strategies. Effective on agricultural residues with low lignin content. Can be used in a post-pretreatment wash to remove inhibitors [45]. |

| Liquid Hot Water | The green reaction medium. At high temperatures, it acts as a non-catalytic or "autocatalytic" solvent, as the ionization of water and release of acetic acid from hemicellulose create a mildly acidic environment that facilitates hydrolysis [41] [43]. | The core reagent for LHW pretreatment. Maintaining a controlled pH (4-7) is crucial to maximize hemicellulose oligomer yield and minimize sugar degradation into inhibitors [41]. |

The Biomass Recalcitrance Challenge represents a fundamental obstacle in biofuel production, referring to the natural resistance of plant cell walls to breakdown into simple sugars. This recalcitrance stems from the complex, reinforced structure of lignocellulosic biomass—a robust matrix of cellulose (35-50%), hemicellulose (20-35%), and lignin (10-25%) [46] [47]. Imagine this structure as a fortified wall: cellulose provides strong crystalline fibers, hemicellulose acts as a surrounding cement, and lignin serves as a durable, waterproof sealant that protects the entire structure [3]. Effective deconstruction of this barrier is crucial for accessing the valuable sugars within, enabling their conversion to biofuels and supporting the development of a sustainable bioeconomy [42].

Solvent-based pretreatment has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome this challenge. By disrupting the intricate lignocellulosic matrix, these solvents enhance the accessibility of carbohydrates for subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation [46] [47]. This technical support center focuses on two key solvent approaches: ionic liquids (ILs) and biocompatible alternatives like ethanolamine, providing researchers with practical guidance for their implementation in advanced biofuel research.

Technical FAQs: Ionic Liquid Pretreatment

1. What are the primary mechanisms by which Ionic Liquids deconstruct biomass?

Ionic liquids disrupt biomass through multiple mechanisms that target the structural components of lignocellulose [47]:

- Hydrogen Bond Disruption: The IL anion forms new hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups of cellulose, disrupting the extensive native hydrogen-bonding network that gives cellulose its crystalline structure.

- Lignin Solubilization: ILs, particularly those with strongly basic anions like acetate, effectively solubilize lignin by disrupting the ether and ester linkages that bind it to carbohydrates.

- Reduction of Crystallinity: By penetrating and swelling the cellulose fibrils, ILs reduce the crystallinity of cellulose, making it more accessible to hydrolytic enzymes.

The following diagram illustrates this multi-mechanism deconstruction process:

2. How do I select an appropriate Ionic Liquid for my specific biomass feedstock?

IL selection depends on biomass type and process goals. Key considerations include [46] [47] [48]:

- Anion Choice: Basic anions like acetate ([OAc]⁻) demonstrate high effectiveness for hardwoods and agricultural residues, while chloride ([Cl]⁻) or acidic ILs may be better for softwoods with higher lignin content.

- Cation Choice: Imidazolium-based cations (e.g., [Emim]⁺, [Bmim]⁺) show strong dissolution capability, while cholinium-based cations offer lower toxicity and better biocompatibility.

- Process Objectives: For full dissolution, select ILs with strong dissolving capacity (e.g., [Bmim][Cl]). For fractionation (ionoSolv process), choose ILs that selectively dissolve lignin and hemicellulose.

Table 1: Performance of Selected Ionic Liquids with Different Biomass Types

| Ionic Liquid | Biomass Type | Conditions | Glucose Yield (%) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Bmim][OAc] | Sugarcane Bagasse | 110°C, 30 min | 96.5 [46] | High delignification (22.5%) and xylan removal (33.5%) |

| [Emim][OAc] | Energy Cane Bagasse | 120°C, 30 min | 87.0 [46] | Effective delignification (32%) |

| [Emim][OAc] | Yellow Pine | 140°C, 45 min | 56.0 [46] | Moderate glucan and lignin removal |

| [Bmim][HSO4]/Water | Scots Pine | 170°C, 4 h | 70.0 [46] | High hemicellulose (64%) and lignin (55%) removal |