Overcoming Substrate Inhibition in Industrial Bioreactors: From Fed-Batch Strategies to Advanced Control Systems

Substrate inhibition presents a major bottleneck in industrial bioprocessing, limiting cell growth, reducing productivity, and impacting the economic viability of producing high-value pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and other biologics.

Overcoming Substrate Inhibition in Industrial Bioreactors: From Fed-Batch Strategies to Advanced Control Systems

Abstract

Substrate inhibition presents a major bottleneck in industrial bioprocessing, limiting cell growth, reducing productivity, and impacting the economic viability of producing high-value pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and other biologics. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing this critical challenge. It explores the fundamental mechanisms of inhibition, details practical operational strategies like fed-batch cultivation, examines advanced model-based and real-time control systems for optimization, and presents case studies and validation methodologies for scaling up robust processes.

Understanding Substrate Inhibition: Mechanisms, Impact, and Diagnostic Signs

Defining Substrate Inhibition vs. Substrate Limitation in Cell Cultures

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental difference between substrate inhibition and substrate limitation? Substrate limitation describes a condition where the rate of microbial growth or a reaction is constrained by the insufficient concentration of an essential nutrient. In contrast, substrate inhibition occurs when the concentration of a substrate exceeds an optimal level and actively reduces the growth rate of cells or the rate of an enzymatic reaction [1] [2].

What are the typical kinetic models used to describe these phenomena? The Monod equation is typically used to model growth under substrate-limited conditions, showing a hyperbolic relationship where the growth rate asymptotically approaches a maximum [1]. Under substrate-inhibiting conditions, the Monod equation is no longer suitable, and derivatives like the Haldane (Andrews) equation are used. This model predicts an increase in the specific growth rate to a peak, followed by a decrease at high substrate concentrations [1] [3] [4].

What are the common causes of substrate inhibition in a bioreactor? High substrate concentrations can lead to inhibition through several mechanisms, including:

What is the most common operational strategy to overcome substrate inhibition? The most common and effective solution is to change the process from a batch to a fed-batch system. This allows for the controlled addition of substrate, maintaining its concentration in the bioreactor at a level that supports growth without causing inhibition [1].

How does scale-up from lab to industrial bioreactors influence these conditions? Bioreactor scale-up can lead to heterogeneity, such as substrate and pH gradients, because mixing times are longer in large tanks [6]. Cells circulating through these gradients are exposed to fluctuating substrate concentrations, potentially moving between zones of limitation and inhibition, which can alter overall culture performance and product quality [6].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem & Symptoms | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased Growth Rate & Bioreactor Output• High substrate concentration• Reduced specific growth rate | • Substrate Inhibition: Concentration exceeds optimal parameters [1].• Osmotic Pressure/Viscosity: High solute concentration causes physiological stress [1]. | • Switch to Fed-Batch: Control substrate addition to maintain low, non-inhibitory levels [1].• Cell Immobilization: Encapsulate cells for a protective barrier [1].• Two-Phase Partitioning Bioreactor: Use a second phase to store and slowly release substrate [1]. |

| Sub-Optimal Product Formation (Growth-Associated Products)• Lower than expected product yield• Reduced final biomass concentration | • Direct Link to Growth Inhibition: For growth-associated products, the specific rate of product formation (qP) is directly proportional to the specific growth rate (μ). When substrate inhibition limits μ, it also limits qP [1]. | • Apply Substrate Inhibition Models: Use the Haldane equation to identify the substrate concentration that maximizes both growth and product formation [1] [4].• Optimize Feed Strategy: In fed-batch, tailor the substrate feed profile to maximize product yield [1]. |

| Incomplete Substrate Utilization• Substrate remains at the end of a batch cycle• Extended lag phases at high initial substrate | • Toxicity at High Concentrations: The initial substrate level is inhibitory, slowing down the onset of active metabolism (lag phase) and subsequent degradation [4]. | • Reduce Initial Substrate Load: Start with a lower, non-inhibitory concentration [4].• Use Two-Phase Kinetic Model: Account for an extended lag phase in your experimental design and modeling [4].• Acclimatize Inoculum: Pre-adapt cells to higher substrate levels. |

Quantitative Data & Kinetic Models

The table below summarizes the key kinetic equations and parameters used to model substrate limitation and inhibition.

| Model Name | Equation | Key Parameters | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monod (Limitation) | μ = μm * [S] / (KS + [S]) [1] |

• μ: Specific growth rate• μm: Max specific growth rate• [S]: Substrate concentration• KS: Saturation constant | Models cell growth under single-substrate limiting conditions; analogous to Michaelis-Menten kinetics [1]. |

| Haldane (Andrews) Inhibition | μ = μm * [S] / (KS + [S] + [S]²/KI) [1] [3] |

• KI: Inhibition constant• Other parameters same as Monod | Most common model for single-substrate inhibition; predicts a peak growth rate followed by decline [1] [4]. |

| Non-Competitive Inhibition Model | μ = μm / [(1 + KS/[S]) * (1 + [S]/KI)] [1] |

• KI: Inhibition constant | A Monod derivative for substrate inhibition. The Haldane model is a special case of this where KI >> KS [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing Substrate Inhibition Kinetics

This protocol outlines a methodology to experimentally determine the kinetic parameters for microbial growth in the presence of a potentially inhibitory substrate, such as phenol.

1. Objective To determine the parameters (μm, KS, KI) of the Haldane model by measuring the growth of Pseudomonas putida at different initial phenol concentrations [4].

2. Materials and Reagents

- Microorganism: Pseudomonas putida [4].

- Growth Medium: Nutrient medium containing beef extract, peptone, and a Mineral Salt Medium (MSM) with phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 [4].

- Inhibitory Substrate: Phenol stock solution.

- Equipment: Shaker incubator, spectrophotometer (for OD600 measurements), centrifuge, sterile flasks.

3. Procedure 1. Inoculum Preparation: Pre-culture P. putida in a medium with a low, non-inhibitory concentration of phenol to acclimate the cells [4]. 2. Batch Experiment Setup: Set up a series of batch cultures in flasks with the growth medium. Spike each flask with a different initial phenol concentration (S0) covering a wide range (e.g., from 50 mg/L to 600 mg/L) [4]. 3. Inoculation: Inoculate each flask with a standard volume of the pre-cultured inoculum. 4. Monitoring: Incubate the flasks under controlled conditions (e.g., 30°C, constant agitation). At regular intervals, sample each flask to measure: * Biomass Concentration (X): Via optical density at 600 nm (OD600). * Substrate Concentration [S]: Phenol concentration, measured using HPLC or colorimetric methods [4]. 5. Data Collection: Continue sampling until the substrate is completely depleted or the growth ceases.

4. Data Analysis

1. Specific Growth Rate (μ): For each initial phenol concentration, plot the natural log of biomass (ln X) versus time. The slope of the linear portion of the curve during the exponential growth phase is the specific growth rate (μ) for that S0 [4].

2. Curve Fitting: Plot the calculated μ values against their corresponding initial substrate concentrations. Fit the Haldane equation (μ = μm * [S] / (KS + [S] + [S]²/KI)) to this data using non-linear regression software to estimate the parameters μm, KS, and KI [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Two-Phase Partitioning Bioreactor (TPPB) | A system designed to reduce aqueous phase substrate concentration by storing the inhibitory substrate in a second, immiscible organic phase. The substrate partitions back into the aqueous phase based on microbial demand, alleviating inhibition [1]. |

| Fed-Batch Bioreactor System | The most common method to overcome substrate inhibition. It allows for the controlled addition of concentrated substrate to the inoculum, preventing the initial high substrate concentrations that cause inhibition [1]. |

| Immobilization Matrix (e.g., Alginate, Chitosan) | Materials used to encapsulate or entrap microbial cells. This creates a protective microenvironment that can reduce the inhibitory effects of toxic substrates and allows for easier cell recovery and reuse [1]. |

| Inhibitory Substrate Models (Phenol) | Phenol is a well-studied model compound representing the behavior of toxic, inhibitory substrates in wastewater and biodegradation studies. It is commonly used to test and validate substrate inhibition kinetics [1] [4]. |

| 2-Chloro-2',4',6'-trimethoxychalcone | 2-Chloro-2',4',6'-trimethoxychalcone, CAS:76554-31-9, MF:C18H17ClO4, MW:332.8g/mol |

| SCOULERIN HCl | SCOULERIN HCl, CAS:20180-95-4, MF:C19H22ClNO4, MW:363.838 |

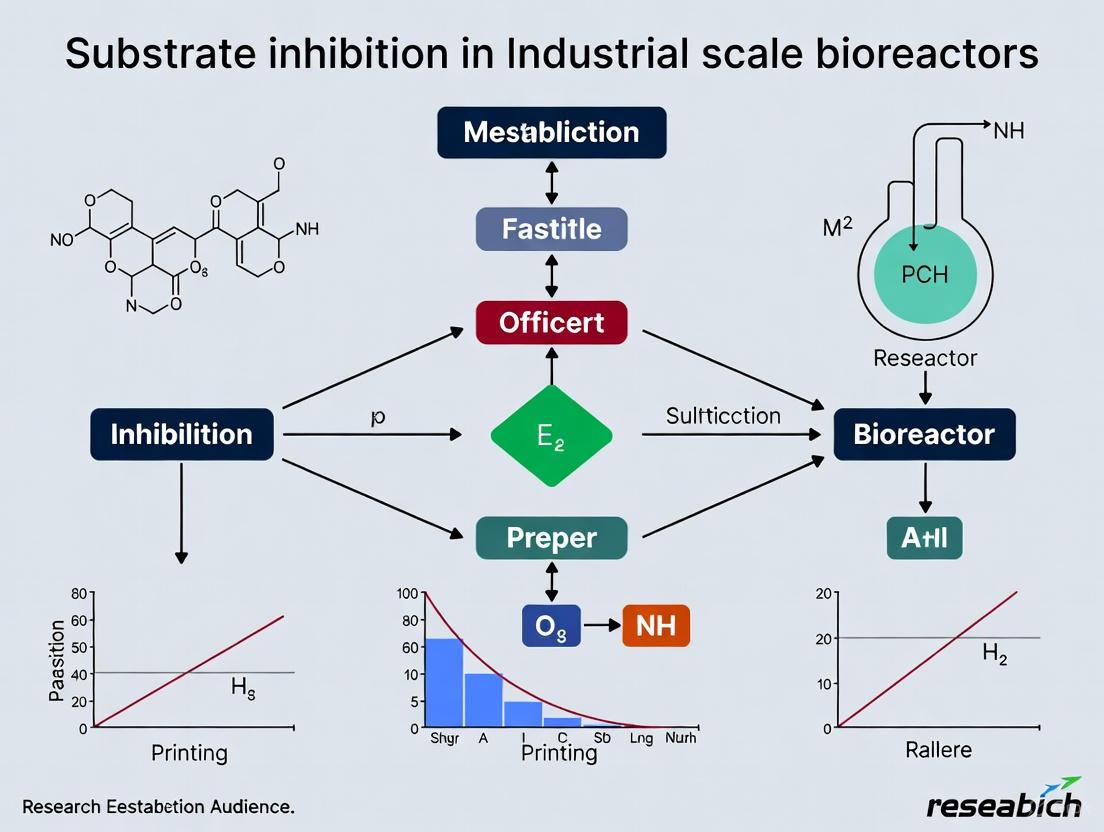

Conceptual Workflow: From Inhibition Identification to Resolution

The following diagram illustrates a logical pathway for diagnosing substrate inhibition and implementing potential solutions in a research or industrial context.

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

Osmotic Stress

Question: What are the immediate signs of osmotic stress in a bacterial fermentation, and what is the primary microbial response? Cells undergoing osmotic stress often show a rapid decline in growth rate and cell productivity. The primary response involves the accumulation of compatible solutes (osmolytes) intracellularly to balance the external osmotic pressure without disrupting metabolic functions. The specific solutes used can depend on the environmental conditions, such as dilution rate and extracellular osmolality [7].

Question: How can I quantify the metabolic impact of osmotic stress to inform process adjustments? Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) is a powerful method for quantifying osmo-induced changes. In a study on Corynebacterium glutamicum, MFA revealed that under osmotic stress, the substrate maintenance coefficient increased 30-fold and the ATP maintenance coefficient increased 5-fold. This demonstrates a critical redistribution of metabolic fluxes, often favoring energy generation (ATP production) over growth. The flexibility at the oxaloacetate (OAA) metabolic node was identified as key to this redistribution [7].

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Metabolic Response to Osmotic Stress

- Objective: To quantify the gradual metabolic changes in a continuous culture subjected to a linear saline gradient.

- Microorganism: Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 21253 (a lysine-overproducing strain) [7].

- Cultivation Conditions:

- Use a defined, growth-limiting medium in a continuous stirred-tank bioreactor.

- Establish a steady state at different dilution rates (e.g., 0.09, 0.13, 0.17, and 0.21 hâ»Â¹).

- Once steady state is reached, initiate a linear osmotic gradient. This is achieved by adding a second feed of the same medium supplemented with 1.2 M NaCl, gradually increasing osmolality from 280 to 1800 mosmol kgâ»Â¹ over 36 hours [7].

- Analytical Techniques:

- Periodically sample the fermentation broth.

- Measure osmolality, dry cell weight, and concentrations of substrates (e.g., glucose), products (e.g., lysine, trehalose), and extracellular by-products (organic acids, amino acids) [7].

- Measure oxygen uptake rate (OUR) and carbon dioxide evolution rate (CER) online [7].

- Extract and analyze intracellular metabolites [7].

- Data Analysis:

Table: Key Quantitative Findings from Osmotic Stress Studies

| Parameter | Organism / System | Observed Change | Experimental Conditions | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Maintenance Coefficient | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Increased 30-fold | Continuous culture with saline gradient (280 to 1800 mosmol kgâ»Â¹) | [7] |

| ATP Maintenance Coefficient | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Increased 5-fold | Continuous culture with saline gradient (280 to 1800 mosmol kgâ»Â¹) | [7] |

| Critical Osmotic Pressure (OP) | Nitrifying sludge in an airlift bioreactor | Performance failure at 18.8–19.2 × 10ⵠPa (≈30 g NaCl/L) | Reactor performance under increasing OP, influent NH₄-N at 420 mg/L | [8] |

| Inhibition Pattern | Nitrifying sludge in an airlift bioreactor | Nitrite oxidizers more sensitive than ammonia oxidizers | Reactor performance under increasing OP | [8] |

Viscosity

Question: Why does assuming a Newtonian fluid model lead to inaccurate shear stress predictions in my cell culture, and what are the consequences? Many cell cultures, especially those with serum or high cell presence, exhibit non-Newtonian, shear-thinning behavior. Assuming Newtonian viscosity (like that of water) underpredicts the actual mean and maximum shear stress in a stirred bioreactor. This is critical because elevated shear stress can alter cell growth kinetics and genetic expression. Accurate quantification requires models like the Sisko model, which can predict shear stresses high enough to impact cells, whereas Newtonian models often do not [9].

Question: Which culture parameters most significantly affect broth rheology? Three key parameters are serum content, cell presence, and culture age. The presence of cells and serum introduces shear-thinning behavior, while conditioned or unconditioned medium without serum is typically Newtonian [9].

Oxygen Transfer Limitations

Question: What are the most critical physiochemical factors that reduce the Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient (kLa) in a stirred-tank bioreactor? The main factors are:

- High Viscosity: Increases the thickness of the liquid film around gas bubbles, dampens turbulence, and reduces gas dispersion efficiency, thereby lowering kLa [10].

- Liquid Coalescence Behavior: Coalescing liquids (like pure water) allow bubbles to merge into larger ones, reducing interfacial area. Cell culture media with salts and organics are non-coalescing, which promotes smaller bubbles and higher kLa [10].

- Sparger and Impeller Design: Inefficient spargers that produce large bubbles or impellers that cause flooding (inability to distribute gas at high flow rates) severely limit oxygen transfer [10].

Question: How does scale-up from lab to production bioreactor specifically exacerbate oxygen transfer limitations? Scale-up dramatically reduces the surface area to volume (SA/V) ratio, making surface aeration negligible. It also increases liquid height, which can increase gas hold-up but also creates longer circulation times and potential for mixing dead zones. Furthermore, maintaining constant power per unit volume (P/V) across scales often leads to higher tip speeds and longer mixing times, changing the hydrodynamic environment and potentially creating dissolved oxygen (DO) gradients that cells experience as they circulate [6].

Experimental Protocol: Determining the Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient (kLa)

- Objective: To measure the kLa, a key parameter representing a bioreactor's oxygen supply capacity [10].

- Method: The dynamic method is commonly used.

- Equilibrate the bioreactor at set process conditions (temperature, agitator speed, air-flow rate) until the dissolved oxygen (DO) level is stable.

- Stop the air supply to the bioreactor. Allow the cells to consume the dissolved oxygen, causing the DO level to drop linearly. Monitor this decrease.

- Once the DO reaches a low level (e.g., 10-20% air saturation), restart the air supply at the same fixed rate.

- Record the DO concentration as it increases over time until it reaches a new steady state [10].

- Data Analysis:

- The kLa is determined by fitting the time-course data of the DO concentration during the re-aeration phase (step 3) to the first-order mass transfer equation [10].

Table: Factors Affecting Oxygen Transfer and kLa

| Factor | Effect on kLa | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Agitator Speed (N) | Increases kLa with higher speed, until impeller flooding | Optimize speed for bubble breakup without cell damage. |

| Air-Flow Rate | Increases kLa to a point; very high rates cause flooding. | Balance gas input with impeller's dispersion capability. |

| Broth Viscosity | Decreases kLa significantly. | Fed-batch processes with high substrate concentration require monitoring. |

| Surface Active Agents (e.g., antifoams) | Can decrease kLa. | Use antifoams judiciously as they can reduce oxygen transfer. |

| Salt Concentration | Increases kLa in water (makes medium non-coalescing). | Understand the coalescence behavior of your medium. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Investigating Bioreactor Stress Mechanisms

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Compatible Solutes (e.g., Betaine, Ectoine, Trehalose) | Studied or added exogenously to help cells counteract osmotic stress by balancing internal and external osmolality without disrupting metabolism [7]. |

| NaCl or Other Salts | Used to create defined osmotic gradients in experimental setups to simulate product or waste accumulation in industrial fermentations [7] [8]. |

| Viscosity Modifiers (e.g., Carboxymethyl Cellulose - CMC) | Used to systematically study the effect of broth rheology on mass transfer (kLa) and mixing in model systems, as they create predictable non-Newtonian fluid behavior [10]. |

| Sisko Model Parameters | A mathematical model for non-Newtonian viscosity that provides a more accurate prediction of shear stress in cell cultures containing serum or high cell densities than Newtonian models [9]. |

| Stoichiometric Metabolic Model | A computational framework used for Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA). It allows for the quantification of metabolic pathway fluxes under stress conditions, revealing shifts in energy and maintenance metabolism [7]. |

| Non-Coalescing Salt Solutions (e.g., 5% Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Used as a model fluid to understand the positive impact of ionic strength on kLa, as it creates smaller bubbles and higher gas hold-up compared to pure water [10]. |

| Haldane (Andrews) Kinetic Model | A growth model (μ = μₘ[S] / (Kₛ + [S] + [S]²/Kᵢ)) used to describe and predict microbial growth when the substrate itself is inhibitory at high concentrations, such as in phenol biodegradation [11] [1]. |

| 4-Azido-n-ethyl-1,8-naphthalimide | 4-Azido-n-ethyl-1,8-naphthalimide, CAS:912921-27-8, MF:C14H10N4O2, MW:266.26 |

| 2-(4-(Dimethylamino)phenyl)acetohydrazide | 2-(4-(Dimethylamino)phenyl)acetohydrazide|CAS 100133-14-0 |

In industrial bioreactor operations, achieving optimal microbial growth and product formation is paramount. A significant challenge in this domain is substrate inhibition, a phenomenon where excessively high concentrations of nutrients, while necessary for growth, paradoxically reduce the cellular growth rate and deteriorate reactor performance [1]. This technical support document provides a structured guide to understanding, diagnosing, and mitigating substrate inhibition using established mathematical models, specifically the transition from Monod to Haldane kinetics.

Core Kinetic Models: Theory and Application

The Monod Model (Substrate-Limited Growth)

Under ideal, non-inhibitory conditions, the specific growth rate of biomass (µ) is described by the Monod equation. This model is analogous to the Michaelis-Menten equation in enzyme kinetics [1].

Model Equation:

μ = μ_m * [S] / (K_S + [S])

Parameter Definitions:

μ: Specific growth rate of the biomass (hâ»Â¹)μ_m: Maximum specific growth rate (hâ»Â¹)[S]: Substrate concentration (g/L or mg/L)K_S: Half-saturation constant; the substrate concentration at which the growth rate is half of µ_m (g/L or mg/L) [1].

The Monod equation accurately predicts microbial growth only in substrate-limiting conditions and fails when substrate concentration becomes inhibitory [1].

The Haldane (Andrews) Model (Substrate-Inhibited Growth)

For systems experiencing substrate inhibition, the Haldane equation is the most common and suitable derivative of the Monod model. It accounts for the decrease in growth rate at high substrate concentrations [1] [3].

Model Equation:

μ = μ_m * [S] / (K_S + [S] + [S]^2 / K_I)

Parameter Definitions (in addition to Monod parameters):

K_I: Substrate inhibition constant (g/L or mg/L). This constant quantifies the sensitivity of the organism to substrate inhibition; a lower K_I value indicates stronger inhibition [1].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in how the specific growth rate (µ) responds to increasing substrate concentration ([S]) under the Monod and Haldane models.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Growth Kinetic Models.

| Parameter | Definition | Unit | Significance in Monod Model | Significance in Haldane Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

μ_m |

Maximum Specific Growth Rate | hâ»Â¹ | The theoretical maximum growth rate achievable. | The theoretical maximum growth rate without inhibition. |

K_S |

Half-Saturation Constant | g/L | Affects the slope at low [S]; lower K_S means faster growth initiation. | Similar role; defines affinity for substrate at non-inhibitory concentrations. |

K_I |

Inhibition Constant | g/L | Not applicable. | Determines the steepness of growth decline; lower K_I indicates stronger inhibition. |

| Optimum [S] | Optimal Substrate Concentration | g/L | Growth rate plateaus at high [S]. | The specific [S] that yields the peak growth rate before inhibition. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing Substrate Inhibition

Problem: A bioreactor process shows declining biomass productivity and growth rates despite an ample supply of the primary substrate.

Step 1: Confirm the Symptoms

Check for these key indicators of substrate inhibition:

- Decreased Growth Rate at High [S]: The specific growth rate (µ) increases with substrate concentration up to a point, then begins to decrease [1].

- Reduced Product Formation for Growth-Associated Products: Since the specific rate of product formation (

q_P) is directly proportional to the specific growth rate (q_P = Y_{P/X} * μ), a decline in growth leads to a direct decline in product generation [1]. - Accumulation of Unconsumed Substrate: The reactor shows high residual substrate concentrations in the medium despite active cells [1].

Step 2: Identify Potential Causes

- Osmotic Stress: High solute concentration creates an osmotic imbalance, stressing the cells [1].

- Increased Viscosity: Concentrated substrate solutions can increase medium viscosity, reducing mass transfer and oxygen diffusivity [1].

- Enzyme-Level Inhibition: The substrate may be inhibiting a critical enzyme in a rate-limiting metabolic pathway, often by binding to an allosteric site or even the enzyme-product complex [1] [5].

Step 3: Model Fitting and Experimental Validation

To conclusively diagnose and quantify inhibition, follow this protocol:

- Design a Batch Experiment: In a controlled lab-scale bioreactor, run a series of batch cultures with identical initial cell density but varying initial substrate concentrations (

[S]_0), including both low and high values. - Monitor Growth: Track biomass concentration (X) and substrate concentration ([S]) over time for each batch.

- Calculate Specific Growth Rates: For each

[S]_0, calculate the maximum specific growth rate (µ) from the slope of the ln(X) vs. time plot during the exponential phase. - Plot µ vs. [S]: Create a plot of the calculated µ values against their corresponding initial substrate concentrations.

- Fit the Models:

Mitigation Strategies and Solutions

Once substrate inhibition is confirmed, several engineering and biological strategies can be implemented.

Strategy 1: Fed-Batch Operation

This is the most common and effective solution for industrial bioreactors [1].

- Concept: Instead of adding all the substrate at the beginning (batch process), the substrate is added incrementally throughout the fermentation.

- Mechanism: This control strategy maintains the substrate concentration in the reactor at a level that is high enough to support rapid growth but below the inhibitory threshold.

- Protocol Outline:

- Start with a low initial substrate concentration.

- Begin feeding a concentrated substrate solution once the growth is established (e.g., after the initial batch phase).

- The feed rate can be pre-programmed (based on the Haldane model) or controlled by online feedback loops (e.g., using pH or dissolved oxygen as a proxy for metabolic activity).

Strategy 2: Microbial Adaptation and Engineering

- Enhanced Tolerance: Recent studies propose exposing a portion of the microbial population to a controlled, non-lethal high-substrate environment in a sidestream unit. This can select for or adapt communities with higher tolerance, which, when returned to the main reactor, enhance the system's overall robustness [13].

- Enzyme Engineering: For specific inhibitory substrates, the mechanism can be tackled at the enzyme level. If inhibition is caused by substrate binding to a specific tunnel or site (as seen in haloalkane dehalogenase LinB), targeted amino acid substitutions can rationally reduce substrate inhibition [5].

Strategy 3: Advanced Bioreactor Design

- Cell Immobilization: Encapsulating cells in a protective matrix (e.g., alginate, biofilms) can create a diffusion barrier, reducing the immediate exposure of cells to high bulk substrate concentrations [1] [14].

- Two-Phase Partitioning Bioreactors (TPPBs): These systems use a non-aqueous phase (e.g., an organic polymer) to absorb and store excess inhibitory substrate. The substrate then partitions back into the aqueous phase containing the cells based on metabolic demand, effectively controlling its concentration [1].

The workflow below summarizes the key steps for diagnosing and mitigating substrate inhibition.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My data shows inhibition, but the Haldane model fit is poor. What are the alternatives? A1: The Haldane model is the most common starting point, but other models exist. You can test non-competitive and competitive substrate inhibition models, which are also derived from enzyme kinetics [1]. Furthermore, extended Monod kinetics that account for combined substrate, product, and cell inhibition are also available and may provide a better fit for complex systems [14] [15].

Q2: How does substrate inhibition differ from product inhibition? A2: While both reduce the growth rate, they involve different mechanisms. Substrate inhibition is caused by an excess of the starting nutrient (reactant). Product inhibition is caused by the accumulation of the metabolic end-product. For example, in anaerobic digestion, the product (volatile fatty acids) can inhibit the process, which is modeled with different kinetic equations [16] [17].

Q3: Can I determine inhibition parameters from a single time-point measurement instead of initial rates?

A3: Yes, recent research indicates that it is possible to estimate V and K_m (and roughly K_I) from measurements taken at a single time-point, even when a large proportion of the substrate has been converted. This is particularly advantageous when substrate is expensive or assays are time-consuming [17]. However, the determination of K_I can be less accurate than with initial rate methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Investigating Substrate Inhibition.

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Defined Growth Medium | Essential for controlled experiments to avoid confounding factors from complex media like yeast extract. Allows precise control of the inhibiting substrate concentration. |

| Inhibitory Substrate Standards | High-purity glucose, salts (e.g., NaCl), phenols, or ammonia/nitrite solutions. Used to create reproducible inhibition conditions for model fitting and validation [1] [13]. |

| Buffers for pH Control | Critical, as pH can fluctuate with metabolism and itself become an inhibitory factor. Necessary to isolate the effect of substrate concentration [16]. |

| Enzymes for Analytics | e.g., Glucose oxidase, HPLC columns. For accurate and frequent measurement of substrate and product concentrations during kinetic experiments. |

| Immobilization Matrix | e.g., Alginate, chitosan, or biofilm support materials. Used for testing mitigation strategies based on cell immobilization [1] [14]. |

| 3-(1H-Imidazol-5-YL)propan-1-amine hcl | 3-(1H-Imidazol-5-YL)propan-1-amine hcl, CAS:111016-57-0, MF:C6H12ClN3, MW:161.633 |

| 2,2-dimethyl-3-oxobutanethioic S-acid | 2,2-dimethyl-3-oxobutanethioic S-acid, CAS:135937-96-1, MF:C6H10O2S, MW:146.204 |

Identifying Tell-Tale Signs of Inhibition in Bioreactor Data

Frequently Asked Questions

What is substrate inhibition and how does it affect my bioreactor process? Substrate inhibition occurs when a high concentration of the substrate itself reduces the growth rate of cells within the bioreactor. This is distinct from low substrate levels limiting growth. In inhibition, elevated substrate levels can cause osmotic issues, increase viscosity, and lead to inefficient oxygen transport, ultimately decreasing bioreactor productivity and final product yields [1].

What are the immediate, observable signs of substrate inhibition in my data? The primary sign is a distinct peak and subsequent decline in the specific growth rate (μ) of your culture as substrate concentration increases, rather than the rate plateauing. You may also observe a sudden, unexpected drop in the dissolved oxygen (% DO) level as contaminating organisms or stressed metabolism increase oxygen demand. Furthermore, the system will no longer fit the standard Monod growth model [1] [18].

Can substrate inhibition occur even if my substrate is not toxic? Yes. Inhibition can be caused by high concentrations of common, non-toxic substrates like glucose due to the resulting osmotic pressure or physical properties like viscosity. It can also occur when a substrate binds to an enzyme-product complex, physically blocking product release and halting the reaction, even if the substrate itself is not inherently toxic [1] [5] [19].

Why does a process that worked at lab-scale show signs of inhibition at industrial scale? At a large scale, mixing is less efficient, leading to longer mixing times and significant concentration gradients. Cells circulating through the bioreactor can be intermittently exposed to very high, inhibitory substrate concentrations near the feed point, even if the average concentration in the tank seems optimal. This scale-dependent heterogeneity can trigger inhibition not seen in well-mixed lab-scale reactors [20].

Troubleshooting Guide

Step 1: Diagnosing the Problem from Process Data

The table below summarizes key data trends that indicate substrate inhibition.

| Parameter to Analyze | Normal Behavior | Behavior Under Substrate Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Growth Rate (μ) | Reaches a stable plateau with increasing [S] | Peaks then decreases with increasing [S] [1] |

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | Stable or predictable decline | Sudden, sharp drop indicating high contaminant/metabolic demand [18] |

| Substrate Consumption | Steady, correlated with growth | Slows or halts despite high residual substrate [1] |

| Model Fit | Fits Monod equation | Requires Haldane equation or other inhibited-growth models [1] |

Actionable Protocol: Estimating Contaminant Growth Rate If a sudden DO drop suggests contamination, you can estimate the growth rate of the contaminating organism to pinpoint the event's timing.

- Once a contamination event is confirmed, terminate aeration and reduce agitation to a low level (to minimize surface aeration but maintain mixing).

- Capture the rate at which DO falls at two different time points (e.g., one hour apart).

- The difference in the rate of decrease is used to estimate the increase in biomass and thus the growth rate. This growth rate can be used to calculate backward to when only a single contaminant cell existed in the bioreactor [18].

Step 2: Understanding the Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the cellular and enzymatic mechanisms that lead to substrate inhibition.

Mechanisms of Substrate Inhibition

Step 3: Implementing Solutions

Summary of Strategies to Overcome Substrate Inhibition

| Strategy | Methodology | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Fed-Batch Operation [1] | Continuous or controlled addition of substrate to the bioreactor instead of adding it all at once (batch). | Maintains substrate concentration below the inhibitory threshold while meeting metabolic demand. |

| Two-Phase Partitioning Bioreactors [1] | Using a second, non-aqueous phase to store excess substrate, which is released into the aqueous phase based on metabolic demand. | Dynamically controls aqueous substrate concentration, particularly useful for toxic substrates. |

| Cell Immobilization [1] | Encapsulating cells within a protective material (e.g., alginate beads). | Creates a physical barrier that can mitigate the effects of inhibitory compounds. |

| Tunnel Engineering [5] [19] | Using protein engineering (e.g., targeted mutations) to modify enzyme access tunnels. | A rational approach to reduce substrate inhibition at the enzymatic level for specific processes. |

| Scale-Down Modeling [20] | Using lab-scale systems that mimic the gradients (e.g., substrate, DO) of large-scale bioreactors. | Identifies and troubleshoots scale-up inhibition problems early in process development. |

Experimental Protocol: Differentiating Inhibition with the Haldane Model To confirm and quantify substrate inhibition, fit your growth data to the Haldane equation for specific growth rate, which is the most common derivative of the Monod equation for inhibiting conditions [1].

Workflow:

- Gather Data: Measure the specific growth rate (μ) of your culture across a wide range of substrate concentrations [S], ensuring you include data points beyond the peak where growth declines.

- Apply the Haldane Model: Use the following equation for kinetic fitting:

μ = (μm * [S]) / (KS + [S] + ([S]^2 / KI)) - Extract Parameters:

- μm: Maximum specific growth rate (hâ»Â¹)

- KS: Substrate affinity constant (g/L) - the concentration at which growth is half of μm

- KI: Substrate inhibition constant (g/L) - indicates the concentration at which inhibition becomes significant; a lower KI means stronger inhibition

The flowchart below outlines the experimental workflow for diagnosing and modeling substrate inhibition.

Inhibition Diagnosis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Key Materials for Investigating Substrate Inhibition

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Haldane Equation Kinetic Model | The primary mathematical model used to quantify the specific growth rate under substrate-inhibiting conditions and extract key parameters (μm, KS, KI) [1]. |

| Scale-Down Bioreactor Systems | Laboratory-scale setups (e.g., multi-compartment reactors, connected STRs) that mimic the substrate and dissolved oxygen gradients of large-scale industrial bioreactors, allowing for pre-emptive troubleshooting [20]. |

| Two-Phase Partitioning Bioreactor | A system that uses a second, immiscible organic phase to sequester toxic or inhibitory substrates, controlling their release into the aqueous phase and mitigating inhibition [1]. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) | Software used to model hydrodynamics and mass transfer in large-scale bioreactors, helping to predict where gradients and potential inhibition zones will form [20]. |

| PTFE-Lined Reactors | Bioreactors with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) linings used when studying corrosive media or organisms, preventing reactor corrosion which could introduce confounding metal ions and affect culture health [21]. |

| 3-Nitro-1-(4-octylphenyl)propan-1-one | 3-Nitro-1-(4-octylphenyl)propan-1-one, CAS:899822-97-0, MF:C17H25NO3, MW:291.391 |

| 1-(2-Methylnicotinoyl)pyrrolidin-2-one | 1-(2-Methylnicotinoyl)pyrrolidin-2-one|Research Chemical |

Direct Impact on Biomass, Product Yields, and Process Economics

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs on Substrate Inhibition in Industrial Bioreactors

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is substrate inhibition and how does it impact my bioreactor process? Substrate inhibition is a phenomenon where the rate of microbial growth or product formation decreases when the concentration of a key substrate exceeds an optimal threshold [1]. This directly reduces biomass accumulation, narrows product formation by limiting cell growth, and negatively impacts process economics through lower yields and prolonged fermentation times [1]. For growth-associated products, the specific rate of product formation is directly proportional to the specific growth rate of the cells ((qP = Y{P/X} \mu)), meaning that inhibition of growth directly reduces product output [1].

What are the common symptoms of substrate inhibition in my culture? Common operational symptoms include:

- A significant decrease in the observed growth rate or substrate consumption rate despite high substrate availability [1].

- Failure to achieve expected final biomass or product titers, even with ample initial nutrients [1].

- Accumulation of unused substrate in the medium when other growth conditions are favorable [1].

Which substrates are commonly associated with inhibition? Glucose, various salts (e.g., NaCl), and toxic compounds like phenols are frequently reported to cause substrate inhibition at high concentrations [1]. In wastewater treatment, high levels of ammonia or nitrite are common inhibitors [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Substrate Inhibition

Problem: Suspected Substrate Inhibition Reducing Biomass and Product Yield

1. Confirm the Diagnosis: Kinetic Analysis

Before implementing solutions, confirm that substrate inhibition is the cause of poor performance.

- Experimental Protocol for Kinetic Characterization:

- Cultivation: Set up a series of small-scale batch cultures (e.g., shake flasks or bench-scale bioreactors) with identical conditions except for the concentration of the suspect substrate. Use a wide range of concentrations, from low to very high [1].

- Monitoring: Monitor cell density (optical density or dry cell weight) and substrate consumption over time for each culture.

- Data Calculation: For each substrate concentration, calculate the specific growth rate ((\mu)) during the exponential phase. This is done using the formula: (\mu = (1/X)(dX/dt)), where (X) is the biomass concentration [1].

- Model Fitting: Plot the specific growth rate ((\mu)) against the initial substrate concentration ([S]). Attempt to fit the data to the Haldane equation, which is a standard model for substrate inhibition kinetics [1] [23]:

[

\mu = \frac{\mum [S]}{KS + [S] + \frac{[S]^2}{KI}}

]

Where:

- (\mum) is the maximum specific growth rate.

- (KS) is the substrate concentration at which the growth rate is half of (\mum).

- (K_I) is the substrate inhibition constant, indicating the concentration at which inhibition becomes significant.

Table 1: Key Kinetic Parameters for Substrate Inhibition Models

| Parameter | Description | Interpretation in Bioprocess Economics |

|---|---|---|

| (\mu_m) | Maximum specific growth rate [1] | Determines the speed of the process; a higher (\mu_m) can lead to shorter fermentation cycles and lower operating costs. |

| (K_S) | Half-saturation constant [1] | Indicates affinity for the substrate; a lower (K_S) means efficient uptake at low concentrations, potentially reducing raw material costs. |

| (K_I) | Substrate inhibition constant [1] | Defines the tolerance to high substrate; a higher (K_I) allows for more concentrated feeds, reducing reactor volume and downstream costs. |

2. Implement Process-Level Solutions

Once confirmed, employ strategies to control the substrate concentration in the bioreactor.

- Solution: Switch to a Fed-Batch Process

- Principle: Instead of adding all substrate at the beginning (batch), substrate is added incrementally throughout the fermentation. This maintains the concentration below the inhibitory threshold while allowing for high final biomass and product titers [1] [24].

- Protocol: Developing a Fed-Batch Strategy:

- Fixed Feeding: Start with a constant feed rate of the substrate solution. This is simple but may not be optimal for all growth phases [24].

- Adapted Feeding: For better performance, use a feedback control system. A 2025 study on ethanol fermentation used evolved gas production (which correlated with glucose consumption) to dynamically adjust the sugar feed rate in real-time [24]. This adaptive strategy improved ethanol productivity by 21% compared to a fixed feeding rate [24].

The following workflow outlines the steps for diagnosing and mitigating substrate inhibition:

- Solution: Enhance Microbial Tolerance

- Principle: Pre-adapt the microbial population to withstand higher substrate levels.

- Protocol: Non-lethal High-Substrate Exposure (Sidestream Treatment):

- A 2024 study on anammox bacteria for wastewater treatment demonstrated this principle. A portion of the sludge was periodically diverted to a separate "sidestream" vessel with a high, but non-lethal, concentration of the inhibitory substrate (nitrite) [22].

- After exposure, the adapted sludge was returned to the main reactor.

- Result: The adapted bacterial community showed a 24.7-fold higher specific activity under high nitrite stress and the overall system exhibited twice the resistance to nitrite shock loads, making the process more robust and stable [22].

Table 2: Comparison of Substrate Inhibition Mitigation Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Implementation Consideration | Reported Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fed-Batch with Adapted Feeding | Controls substrate concentration in the main reactor via real-time feedback [24]. | Requires sensors (e.g., for evolved gas) and control systems. More complex than fixed feeding. | 21% increase in ethanol productivity [24]. |

| Microbial Tolerance Enhancement | Increases the intrinsic resistance of the cells to the inhibitory substrate [22]. | Requires a separate sidestream unit and optimization of adaptation conditions. | 24.7x higher activity under inhibition; 2x greater system stability [22]. |

3. Investigate Biological and Additive Solutions

- Use of Effectors/Additives: Research has shown that certain compounds can modulate enzyme activity to alleviate substrate inhibition. For example, a 2025 study found that β-carotene acted as a competitive inhibitor yet strongly attenuated substrate inhibition in a glycosyltransferase enzyme, leading to increased product formation at high substrate levels [25]. While this is an enzymatic example, it highlights the potential of exploring media additives.

- Cell Immobilization: Encapsulating cells in a protective matrix (e.g., alginate beads) can create a physical barrier that reduces the immediate exposure to high substrate concentrations, thereby mitigating inhibition [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Investigating Substrate Inhibition

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Haldane Equation Model | The primary kinetic model ((\mu = \frac{\mum [S]}{KS + [S] + [S]^2/KI})) used to fit growth data and extract inhibition constants ((KI)) [1] [23]. |

| Fed-Batch Bioreactor System | A bioreactor equipped with pumps and control software for the continuous or intermittent addition of substrate. Essential for implementing feeding strategies [1] [24]. |

| Evolved Gas Analyzer | A sensor used to monitor metabolic activity (e.g., COâ‚‚ production). Can serve as a real-time feedback parameter for adaptive feeding strategies [24]. |

| Sidestream Reactor Unit | A smaller, auxiliary vessel used for the non-lethal high-substrate adaptation of a portion of the microbial inoculum [22]. |

| Inhibitory Substrates | Model compounds like phenols, high concentrations of glucose, or salts (NaCl) used to experimentally induce and study substrate inhibition [1]. |

| N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-d4 | N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-d4, CAS:1160357-16-3, MF:C6H14N2O, MW:134.215 |

| (2S,5R)-5-Ethylpyrrolidine-2-carboxamide | (2S,5R)-5-Ethylpyrrolidine-2-carboxamide|CAS 102734-97-4 |

Operational Strategies and Bioreactor Designs to Mitigate Inhibition

In industrial bioprocessing, achieving high product titers is often hampered by substrate inhibition, a phenomenon where high concentrations of nutrients (like glucose, salts, or phenols) paradoxically reduce microbial growth rates and productivity [1]. This inhibition occurs due to osmotic stress, increased medium viscosity, and inefficient oxygen transport, ultimately limiting the efficiency of batch processes [1]. Fed-batch cultivation has emerged as the industry-preferred strategy to overcome this challenge. By incrementally adding nutrients to the bioreactor instead of providing them all at the beginning, fed-batch processes maintain substrate concentrations below inhibitory thresholds, enabling higher cell densities and significantly improved product yields [26] [1] [27]. This guide provides troubleshooting and best practices for implementing fed-batch strategies to control substrate concentration effectively.

Comparing Cultivation Modes: Why Fed-Batch is the Gold Standard

The choice of cultivation mode profoundly impacts process performance, especially concerning substrate handling. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different bioprocess strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Bioprocess Cultivation Modes

| Cultivation Mode | Substrate Addition | Advantages | Challenges | Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch | All nutrients provided at the start [26] | Short duration; lower contamination risk; easier management [26] | Substrate/product inhibition; lower biomass & product yields [26] | Rapid experiments, strain characterization [26] |

| Continuous | Fresh medium added continuously as harvest is removed [26] | Maximum productivity; steady-state for metabolic studies [26] | High contamination risk; genetic changes; difficult product traceability [26] | Long-term production, metabolic studies [26] |

| Fed-Batch | Nutrients added during cultivation; no harvest until end [26] | Overcomes substrate inhibition; high cell density & product titer; flexible control [26] [1] [27] | Build-up of inhibitory toxins; requires advanced process understanding [26] | Industrial production of recombinant proteins, antibiotics, amino acids [26] [27] |

| Repeated Fed-Batch | Most broth harvested and replaced with fresh medium for the next cycle [26] | Prevents toxin accumulation; constant yields across cycles; segregated batches [26] | Culture density must be monitored and controlled [26] | Single Cell Protein, lipids, fatty acids, penicillin production [26] |

Troubleshooting Fed-Batch Cultivation: FAQs and Solutions

FAQ: How do I choose the right feeding strategy for my process?

Selecting a feeding strategy depends on your organism's kinetics and process goals. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting and optimizing a feeding strategy.

Different feeding strategies offer distinct advantages and limitations, as detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Overview of Fed-Batch Feeding Strategies and Their Applications

| Feeding Strategy | Mechanism | Key Advantage | Key Challenge | Representative Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant Feeding | Substrate added at a fixed rate [28] | Simple implementation; no complex equipment needed [28] | Can lead to substrate accumulation or limitation over time [28] | General-purpose; processes with stable metabolic rates [28] |

| Exponential Feeding | Feed rate increases exponentially to match microbial growth [26] [28] | Maintains constant, optimal specific growth rate; prevents substrate build-up [26] | Requires a priori knowledge of growth kinetics [28] | High-cell density cultivation; recombinant protein production [26] |

| Adaptive/Feedback Feeding | Feed rate adjusted based on real-time sensor data (e.g., dissolved Oâ‚‚, evolved gas) [24] | Responds to actual metabolic activity; mitigates inhibition from fluctuating feeds [24] | Requires sophisticated sensors and control algorithms [24] | Lignocellulosic ethanol fermentation; processes with inhibitor-containing feeds [24] [29] |

| Pulsed Feeding | Specific nutrient amounts added intermittently [24] | Simple cycle; useful for inducing metabolic shifts [26] | Creates spikes in substrate/inhibitor concentration [24] | Triggering recombinant protein expression; lab-scale experiments [26] |

FAQ: I'm still seeing signs of inhibition despite fed-batch operation. What could be wrong?

Inhibition symptoms in a fed-batch process often point to an improperly tuned feeding profile or other accumulating inhibitors.

Problem: Feed rate is too high. Even in fed-batch mode, if the addition rate is excessive, the instantaneous substrate concentration in the bioreactor can rise into the inhibitory zone [1].

- Solution: Reduce the initial feed rate. Use the Haldane equation (µ = µₘ[S] / (Kₛ + [S] + [S]²/Kᵢ)) to model substrate inhibition kinetics and identify a safe operating concentration [1]. Consider switching to an adaptive feeding strategy that uses real-time signals like evolved gas production to adjust the feed rate dynamically, preventing substrate spikes [24].

Problem: Accumulation of toxic by-products. Fed-batch processes are prone to the build-up of metabolic by-products (e.g., alcohols, organic acids, toxins) that can inhibit growth [26] [27].

- Solution: Explore a repeated fed-batch or semi-continuous approach. By periodically replacing a large portion of the broth, you remove these inhibitory metabolites while retaining the cells for the next production cycle [26]. Alternatively, integrate a product removal system (e.g., in-situ extraction, stripping) for severe product inhibition cases.

Problem: Microbial strain is inherently sensitive.

- Solution: Implement strain adaptation. Continuously expose a portion of your cell population to a non-lethal high-substrate environment in a sidestream unit. This "training" enhances the community's tolerance, as demonstrated with anammox bacteria facing nitrite inhibition [22].

FAQ: How can I reliably estimate key parameters like substrate uptake rate in real-time?

Accurate real-time estimation of metabolic parameters like the maximum substrate uptake rate ((qS^{max})) and biomass yield ((Y{XC})) is critical for control but challenging due to microbial adaptation dynamics [30].

- Solution: Employ advanced model-based observers. Standard models like Monod assume instantaneous microbial response, leading to plant-model mismatch. Modern Bayesian estimation frameworks, such as Particle Filters, explicitly model the substrate uptake rate ((q_S)) as a dynamic state variable. This allows the estimator to adapt to the microorganism's changing metabolic capacity throughout the fermentation, providing more reliable estimates for effective process control [30].

Experimental Protocols for Key Fed-Batch Techniques

Protocol: Establishing an Exponential Feed for High Cell Density Cultivation

This protocol is designed to maintain a constant specific growth rate, preventing substrate limitation or inhibition.

- Prerequisite - Kinetic Parameter Determination: Perform initial batch cultures to determine the organism's maximum specific growth rate (µₘ) and yield coefficients (e.g., YX/S).

- Calculate Feed Profile: The feed rate F(t) is calculated to increase exponentially according to the equation:

( F(t) = (µ / Y{X/S}) * (X0 * V0) * (e^{µ * t}) / SF )

where:

- ( F(t) ) = Feed flow rate (L/h)

- ( µ ) = Desired specific growth rate (hâ»Â¹) - typically set slightly below µₘ

- ( Y{X/S} ) = Biomass yield on substrate (g biomass / g substrate)

- ( X0 ) = Initial biomass concentration (g/L)

- ( V0 ) = Initial culture volume (L)

- ( SF ) = Substrate concentration in the feed solution (g/L)

- Bioreactor Setup: Inoculate the bioreactor as per standard batch protocol. Monitor growth (e.g., via optical density).

- Initiate Feeding: Begin the exponential feed once the batch substrate is nearly depleted (typically in late exponential phase). Use a programmable pump to implement the calculated feed profile.

- Monitor and Control: Continuously monitor dissolved oxygen (DO). Implement a DO cascade control (adjusting stirrer speed, gas flow, Oâ‚‚ proportion) to maintain DO above a critical level (e.g., 20-30%) [26]. Control pH with base addition.

- Termination: End the process when the maximum working volume is reached or when productivity declines.

Protocol: Adaptive Fed-Batch Based on Evolved Gas Analysis

This strategy uses real-time metabolic activity to dynamically control feeding, ideal for substrates with inhibitors [24].

- Correlation Phase: In preliminary experiments, establish a positive correlation between the rate of COâ‚‚ or other gas evolution and the glucose consumption rate for your specific strain and conditions [24].

- System Calibration: Set up the bioreactor with a mass flow meter or gas analyzer to measure evolved gas production rates in real-time.

- Fermentation Start: Begin with a batch phase containing an initial, non-inhibitory sugar concentration.

- Implement Adaptive Control: As the batch sugar depletes, initiate feeding. Instead of a fixed profile, the controller adjusts the sugar feed rate proportionally to the measured evolved gas production rate. This ensures that sugar addition matches the culture's real-time metabolic capacity.

- Validation: Periodically take offline samples to validate that residual substrate concentration remains low and that metabolic by-products are within acceptable limits.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Fed-Batch Bioreactor Research

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Medium | Allows precise control over every nutrient; essential for studying metabolic fluxes and for reproducible feeding strategies. | e.g., DeLisa minimal medium for E. coli [30]. |

| Concentrated Feed Solutions | Enables nutrient delivery without excessive dilution of the culture, allowing for high cell densities and product titers. | Glucose feed at 400-600 g/L is common [27] [24]. |

| Acid/Base Solutions | For strict pH control, which is crucial for maintaining optimal enzyme activity and growth kinetics throughout the fermentation. | Ammonium hydroxide (NHâ‚„OH) is common as it also serves as a nitrogen source [27]. |

| Antifoaming Agents | Controls foam formation at high cell densities, which can otherwise interfere with sensors, gas exchange, and lead to contamination. | Use sterile, biocompatible silicone-based emulsions. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Enables real-time monitoring and control for advanced feeding strategies. | Dissolved Oâ‚‚ and pH probes are standard; off-gas analyzers (for Oâ‚‚/COâ‚‚) are key for metabolic rate analysis [24] [30]. |

| Modeling & Estimation Software | For designing feed profiles, simulating processes, and implementing real-time state estimators. | Used with Particle Filters for Bayesian estimation of parameters like (q_S^{max}) [30]. |

| 2-Chloro-4-(4-methylsulfonylphenyl)phenol | 2-Chloro-4-(4-methylsulfonylphenyl)phenol|CAS 1261991-24-5 | High-purity 2-Chloro-4-(4-methylsulfonylphenyl)phenol (CAS 1261991-24-5) for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| 6-(Difluoromethoxy)picolinonitrile | 6-(Difluoromethoxy)picolinonitrile|CAS 1214349-26-4 | 6-(Difluoromethoxy)picolinonitrile is a key building block for medicinal chemistry research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Implementing Model-Based Feeding Strategies for High-Density Cultures

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our high-density culture is experiencing sudden drops in productivity, even with adequate substrate feeding. What could be the cause?

This is a classic symptom of substrate inhibition, where the concentration of the nutrient itself becomes toxic to the cells, suppressing growth and product formation [11] [31]. At an industrial scale, mixing inefficiencies can create localized pockets of high substrate concentration, even if the bulk concentration appears safe [32].

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify Mixing Efficiency: Check the power input and Reynolds number (

Rei) of your bioreactor. Ensure the system is in a turbulent flow regime (Rei > 10^4for stirred tanks) to prevent concentration gradients [32]. - Profile Substrate Concentration: Take frequent, small-volume samples from different locations in the bioreactor to check for heterogeneity.

- Monitor Metabolic Markers: A sudden spike in the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration can indicate that cells have reduced their metabolic activity due to inhibition [11].

- Verify Mixing Efficiency: Check the power input and Reynolds number (

- Solution: Transition from a fixed feeding rate to an adaptive, model-based feeding strategy. Use a kinetic model (e.g., Haldane, Andrews) to determine the inhibitory concentration threshold and design a controller that uses a real-time measured variable (like DO or evolved gas [24]) to adjust the feed rate and maintain substrate below the inhibition level [11] [24] [31].

Q2: How can we precisely estimate substrate inhibition kinetics for our model without an excessive number of experiments?

Traditional methods require multiple substrate and inhibitor concentrations, which is resource-intensive. A recent advanced methodology, the IC50-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA), substantially reduces the experimental burden [33].

- Protocol: Precise Estimation of Inhibition Constants with 50-BOA

- Objective: Accurately determine the inhibition constants (

K_icandK_iu) for a mixed inhibition model with minimal experiments. - Procedure:

- First, estimate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (

IC50) using a single substrate concentration (typically at theK_Mvalue) across a range of inhibitor concentrations [33]. - For the main experiment, use a single inhibitor concentration that is greater than the estimated IC50. Use multiple substrate concentrations around this point [33].

- Measure the initial reaction velocities.

- Fit the mixed inhibition model to the data while incorporating the harmonic mean relationship between the

IC50and the inhibition constants during the fitting process [33].

- First, estimate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (

- Key Benefit: This method reduces the number of required experiments by over 75% while ensuring precision and accuracy, making model development faster [33].

- Objective: Accurately determine the inhibition constants (

Q3: What is the most robust variable to control for stabilizing an unstable, substrate-inhibited process?

Dissolved oxygen (DO) tension has been proven to be a robust controlled variable for this purpose [11]. In a continuous stirred-tank reactor (CSTR) with substrate inhibition, many steady states are inherently unstable. A feedback controller that uses the DO signal to manipulate the medium feeding flow rate (acting as an auxostat) can successfully stabilize the culture [11].

- Rationale: The DO level is a strong, non-invasive indicator of the cellular metabolic activity. A rise in DO signals that substrate consumption has slowed, often due to inhibition, allowing the controller to preemptively reduce the substrate feed rate before toxicity becomes severe [11].

Q4: What are the key differences between classic PID control and advanced model-based adaptive control for feeding?

The table below summarizes the core differences, which are critical for handling nonlinear processes like substrate-inhibited cultures.

Table: Comparison of Bioreactor Control Strategies

| Feature | Classic PID Control | Model-Based Adaptive Linearizing Control |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Reactive; corrects error after it occurs [34]. | Predictive; uses a process model to anticipate and compensate for changes [35]. |

| Handling of Nonlinearity | Poor performance with highly nonlinear processes like substrate inhibition [34]. | Specifically designed for nonlinear processes; linearizes the system around its operating point [35]. |

| Model Requirement | Not required. | Requires a kinetic model of the process (e.g., Haldane model for growth) [35]. |

| Adaptability | Limited; requires manual re-tuning for different process phases [34]. | High; uses software sensors to estimate unknown parameters (e.g., growth rate) in real-time [35]. |

| Best Use Case | Regulating simple, well-defined parameters like temperature and pH [34]. | Controlling complex, time-varying variables like substrate concentration in inhibitory environments [11] [35]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Fed-Batch Process with Adaptive Feeding Based on Evolved Gas

This protocol is adapted from a study on fed-batch ethanol fermentation, where an adapted feeding strategy enhanced productivity by 21% compared to fixed feeding [24].

- Objective: To maintain a low, non-inhibitory substrate level in a high-density culture of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by linking the feed rate to real-time metabolic activity.

- Materials:

- 5-L stirred tank bioreactor

- Feed medium with high glucose concentration

- Evolved gas analyzer (for COâ‚‚ and/or Oâ‚‚)

- Peristaltic pump for feed medium

- Data acquisition and control system

- Procedure:

- Batch Phase: Inoculate the bioreactor and allow the batch culture to proceed until the initial glucose is nearly depleted, indicated by a sharp drop in the evolved COâ‚‚ rate.

- Initiate Feeding: Start the continuous feeding of the concentrated glucose medium.

- Implement Control Logic: Program the controller to adjust the feed pump rate based on the signal from the evolved gas analyzer.

- If the evolved COâ‚‚ rate increases above a set threshold, it indicates high metabolic activity and potential for substrate depletion. The controller should increase the feed rate.

- If the evolved COâ‚‚ rate decreases, it suggests metabolic slowing, potentially due to emerging substrate inhibition. The controller should decrease the feed rate [24].

- Process Termination: Harvest the broth when the product titer reaches the target or when productivity declines significantly at the end of the production phase.

The following workflow diagrams the adaptive control process:

Protocol 2: Developing a Custom Kinetic Model for Substrate Inhibition

This protocol is based on work developing a new kinetic model for the deammonification process, which experiences double-substrate inhibition [31].

- Objective: To create and validate a custom kinetic model that accurately predicts the specific substrate consumption rate under inhibitory conditions.

- Materials:

- Lab-scale bioreactor (e.g., airlift configuration)

- High-density culture

- Automated sampling system

- Analytics (HPLC, spectrophotometer, etc.)

- Statistical software (for model fitting)

- Procedure:

- Batch Kinetic Tests: Conduct a series of batch experiments where the reactor is exposed to a wide range of initial substrate concentrations, from low to severely inhibitory levels (e.g., 60 to 1200 mg/L) [31].

- Data Collection: Frequently sample the broth to measure substrate and product concentrations over time, calculating the specific consumption/production rates.

- Model Fitting: Fit several established empirical models (Monod, Haldane, Edwards, etc.) to the data using non-linear regression.

- Statistical Validation: Use statistical criteria like Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Relative Mean Error (RME), and R² to select the best-fitting model [31].

- Custom Model Development (if needed): If no empirical model provides a statistically sound and physiologically realistic fit, develop a new model. This model should incorporate terms for both affinity and inhibition and be based on the intrinsic characteristics of the process and microorganism consortium [31].

- Model Application: Use the validated model to predict the optimal operating range and to design feeding strategies that maximize the substrate consumption rate while avoiding the inhibitory zone.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Model-Based Feeding Experiments

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Stirred-Tank Bioreactor | Provides a controlled environment (pH, T, DO) and homogeneous mixing, which is critical for avoiding substrate gradients and reliable data collection [36]. | 5-L benchtop system with automated control and data logging [24]. |

| Airlift Bioreactor | Alternative configuration offering efficient mixing with low shear stress, suitable for sensitive cells and processes like deammonification [31]. | NITRAMMOX type with a perforated inner concentric tube [31]. |

| Dissolved Oxygen Probe | Serves as a key state variable for feedback control in substrate-inhibited cultures, indicating metabolic activity shifts [11]. | Amperometric probe with real-time output to controller. |

| Evolved Gas Analyzer | Provides a non-invasive, real-time proxy for metabolic rate (e.g., COâ‚‚ evolution, Oâ‚‚ uptake), enabling adaptive feeding strategies [24]. | Mass spectrometer or off-gas analyzer for COâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚. |

| Software Sensors | Algorithms that estimate unmeasured variables (e.g., growth rate, substrate uptake) in real-time using available sensor data, enabling fully adaptive control [35]. | General Dynamical Model (GDM) approach with estimator tuning [35]. |

| Haldane/Andrews Kinetic Model | A structured kinetic model that describes microbial growth under substrate inhibition, forming the basis for model-based controllers [11] [31]. | µ = µmax * S / (KS + S + S²/K_i) |

| General Dynamical Model (GDM) | A nonlinear operational model used to derive adaptive linearizing control laws for a wide range of bioprocesses in stirred tanks [35]. | dξ/dt = Kφ(ξ) - Dξ + F |

| 2-(2-Aminobut-3-enyl)malonic Acid | 2-(2-Aminobut-3-enyl)malonic Acid, CAS:1378466-25-1, MF:C7H11NO4, MW:173.168 | Chemical Reagent |

| Benzo[g]chrysene-9-carbaldehyde | Benzo[g]chrysene-9-carbaldehyde, CAS:159692-75-8, MF:C23H14O, MW:306.364 | Chemical Reagent |

The following diagram illustrates the structure of a model-based adaptive control system, integrating software sensors:

Leveraging Membrane Bioreactors for Enhanced Mass Transfer and Cell Retention

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common MBR Operational Issues and Solutions

| Problem Symptom | Potential Causes | Recommended Actions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced Permeate Flux | Membrane fouling, channel clogging, or low sludge activity. | Check transmembrane pressure; perform chemical cleaning if pressure is >20 kPa above initial stage. Verify mixed liquor suspended solids (MLSS) concentration and sludge activity. | [37] [38] |

| Poor Effluent Quality | Biocatalyst inhibition, shock loading, or low sludge concentration. | Check influent for toxic inhibitors (e.g., phenols, detergents). Suspend water pump and aerate to restore sludge activity if MLSS is too low. | [38] [39] |

| Uneven Aeration & Poor Mixing | Clogged aerators, insufficient air scour, or faulty blowers. | Inspect and clean aerators; check air supply pipelines for blockages or leaks. Ensure blower is functioning and gas flow rates are adequate. | [37] [38] |

| Excessive Foaming | Surfactants in influent, low organic loading, or sludge age issues. | Increase reactor sludge concentration; use water sprays or compatible defoamer as a last resort. Review and adjust organic loading rate. | [38] |

| dCO2 Accumulation | Poor stripping efficiency at large scale, low surface-to-volume ratio. | Increase gas sparging rate or use microspargers; consider headspace aeration. Model dCO2 accumulation to optimize stripping strategy. | [40] [41] |

| Black Sludge & Foul Odor | Insufficient aeration, leading to anoxic/anaerobic conditions. | Increase aeration rate immediately; suspend permeate withdrawal until sludge color and odor return to normal. | [38] |

Table 2: Membrane Fouling and Cleaning Guide

| Issue Type | Identifying Signs | Cleaning Method & Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Fouling | Gradual, steady increase in TMP. | Maintenance Clean (MC): Chemically Enhanced Backwash (CEB) with Sodium Hypochlorite (NaOCl). Typical frequency: 2 times per week for ~1 hour. [42] |

| Inorganic Fouling | Scaling, particularly with high iron/calcium. | Maintenance Clean (MC): CEB with Citric Acid or Oxalic Acid. Typical frequency: Once per week for ~1 hour. Oxalic acid is gentler on infrastructure. [42] |

| Severe/Irreversible Fouling | High TMP sustained after maintenance cleaning. | Recovery Clean (RC): Soak membranes in NaOCl or acid solution for 6–16 hours. Typical frequency: Twice per year for each chemical. [42] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can we mitigate substrate inhibition in an MBR treating toxic industrial wastewater?

A: Submerged MBRs, particularly anaerobic configurations (SAnMBR), are highly effective for handling inhibitory substrates like phenolic compounds. The key is leveraging high biomass retention to promote microbial acclimation.

- Strategy: Operate at a high Solids Retention Time (SRT) to enrich a specialized microbial consortium capable of degrading the toxic compound. This decouples microbial growth rates from hydraulic washout.

- Evidence: A 189-day study on a SAnMBR treating 2,4-dichlorophenol showed that after initial inhibition upon introducing the toxin, the system quickly recovered, achieving 99.6% removal efficiency for both COD and the phenolic compound. This demonstrates robust acclimation and stability under shock loading [39].

- Protocol: Gradually increase the concentration of the inhibitory substrate in the influent over several weeks to allow for microbial adaptation while continuously monitoring COD removal and sludge viability.

Q2: What are the best strategies for bubble-free aeration to protect sensitive cell lines?

A: For mammalian cell cultures sensitive to shear stress from bursting bubbles, tubular membrane aeration is a preferred bubble-free method.

- Principle: Oxygen diffuses through a gas-permeable membrane (e.g., silicone or PTFE) directly into the liquid, eliminating bubbles and associated cell damage [40].

- Advanced System: The Dynamic Membrane Aeration Bioreactor uses an oscillating rotor wrapped with silicone tubing. This design doubles the gas mass transfer rate at the same shear stress level compared to conventional rotor-stator systems, overcoming previous limitations in scalability and transfer capacity [40].

- Application: This is crucial for producing therapeutic proteins with sensitive cell lines that cannot tolerate shear-protective additives like Pluronic F-68, preventing complications in downstream purification [40].

Q3: Our large-scale bioreactor suffers from dissolved CO2 (dCO2) accumulation. How can we enhance stripping in an MBR?

A: dCO2 accumulation is a common scale-up challenge due to increased liquid height and bubble saturation.

- Problem: In large tanks, bubbles become saturated with CO2 as they rise, reducing the driving force for stripping. The low surface-to-volume ratio also diminishes the contribution of surface aeration [41].

- Solution: Use a mathematical model to design your stripping strategy. The model incorporates factors like:

- Gas Flow Rate (vvm): Higher sparging rates increase stripping.

- Bubble Residence Time: This is a dominant factor at manufacturing scale.

- Surface Aeration: While less effective at large scale, it can be included in models via a surface-exchange coefficient (ksurf) [41].

- Recommendation: Systematically test sparging rates, agitation, and surface aeration using a model medium to determine the volumetric CO2 transfer index (kLaCO2) specific to your reactor geometry, rather than relying solely on oxygen kLa values [41].

Q4: How can we reduce the environmental impact and cost of membrane cleaning?

A: Optimize cleaning protocols by challenging standard chemical regimens.

- Evidence: Long-term pilot trials demonstrated that alternative cleaning strategies can reduce chemical use by up to 75% without sacrificing treatment performance. This can lead to cost reductions of up to 70% and lower environmental impacts by up to 95% for some indicators [42].

- Action:

- Evaluate Cleaning Agents: Test oxalic acid as a substitute for citric acid for inorganic fouling, as it can be equally effective and is often cheaper and gentler on concrete basins [42].

- Optimize Frequency: Extend the intervals between maintenance cleanings (MC) based on Trans-Membrane Pressure (TMP) trends rather than a fixed calendar schedule.

- Prevent Fouling: Ensure fine screening (down to 1 mm) and optimal membrane aeration to reduce the fouling load, thereby reducing the need for aggressive cleaning [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for MBR Research

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hypochlorite (NaOCl) | Chemical cleaning agent for removing organic foulants (proteins, polysaccharides) from membranes. | Primary chemical for maintenance cleaning. Can cause membrane aging over time and lead to formation of toxic byproducts (AOX). [37] [42] |

| Citric Acid / Oxalic Acid | Chemical cleaning agent for removing inorganic scaling (e.g., iron-based precipitants, calcium). | Citric acid is common; oxalic acid is an effective, often gentler alternative. Switching can reduce costs and environmental footprint. [42] |

| Hollow Fiber Membranes | Ultrafiltration membranes for solid-liquid separation and cell/biocatalyst retention. | Provides high surface area. Typical pore size ~0.04 μm. Made from materials like polypropylene. [42] [39] |

| Pluronic F-68 | Shear-protective agent for sensitive cell lines in classical bubble-aerated bioreactors. | Protects cells from hydrodynamic damage. Not always suitable, as it can complicate downstream purification. [40] |

| Silicone or PTFE Tubing | Core component for bubble-free membrane aeration systems. | Allows direct oxygen diffusion without bubble formation, crucial for protecting shear-sensitive cells like mammalian lines. [40] |

| Methyl N-Boc-2-bromo-5-sulfamoylbenzoate | Methyl N-Boc-2-bromo-5-sulfamoylbenzoate | Methyl N-Boc-2-bromo-5-sulfamoylbenzoate is a high-quality building block for pharmaceutical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Methyl 4-bromo-6-chloropicolinate | Methyl 4-bromo-6-chloropicolinate, CAS:1206249-86-6, MF:C7H5BrClNO2, MW:250.476 | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodology: Long-Term SAnMBR Performance for Inhibitory Wastewater

This protocol is adapted from a study evaluating the treatment of synthetic phenolic wastewater [39].

1. Reactor Setup & Configuration:

- Use a bioreactor with two functional zones: a lower anaerobic digestion chamber and an upper filtration zone.

- Submerge hollow fiber ultrafiltration membranes (e.g., polypropylene, 0.045 μm pore size, 0.93 m² surface area) in the upper zone.

- Equip the system with peristaltic pumps for influent feeding and permeate suction, and a gas sparging system for membrane scouring.

2. Startup & Acclimation:

- Seed the reactor with anaerobic digested sludge (e.g., 2L of sludge with VSS ~12,900 mg/L and TSS ~21,100 mg/L).

- Begin with a synthetic wastewater feed using glucose as a carbon source, supplemented with macro- and micronutrients.

- Start at a low Organic Loading Rate (OLR), e.g., 0.125 kg COD/m³·day.

3. Experimental Operation & Inhibition Study:

- Gradually increase the OLR over time (e.g., from 0.125 to 0.798 kg COD/m³·day) to assess system stability.

- On a specified day (e.g., Day 118), introduce the inhibitory substrate (e.g., 2,4-Dichlorophenol).

- Incrementally increase the concentration of the inhibitor from 5 mg/L to 300 mg/L to allow for microbial acclimation.

4. Monitoring & Data Collection:

- Performance: Daily analysis of COD, inhibitor concentration (e.g., 2,4-DCP), pH, and turbidity.