Parallel Labeling Experiments for 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of parallel labeling experiments for 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA), a powerful methodology for quantifying intracellular metabolic reaction rates.

Parallel Labeling Experiments for 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of parallel labeling experiments for 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA), a powerful methodology for quantifying intracellular metabolic reaction rates. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles and historical evolution from radioisotopes to stable isotopes. The review details current methodological approaches, experimental workflows, and applications in metabolic engineering and disease research. It further explores advanced strategies for troubleshooting, experimental optimization, and robust model validation and selection. By synthesizing information across these core areas, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design and implement effective parallel labeling studies that yield precise, reliable flux measurements for advancing biomedical research and therapeutic development.

From Radioisotopes to Stable Isotopes: The Foundations of Parallel Labeling

The investigation of cellular metabolism is fundamental to understanding how cells harness nutrients to generate energy, synthesize biomolecules, and support growth. Central to this understanding is the ability to trace the fate of individual atoms as they flow through complex metabolic networks. Isotopic tracers—atoms in which one or more nuclei have been replaced with a different isotope—provide this capability and have revolutionized metabolic research [1]. The use of these tracers has undergone a significant evolution, transitioning from a primary reliance on radioisotopes in the early and mid-20th century to the predominant use of stable isotopes today [1] [2]. This shift was driven by parallel advancements in detection technology, computational power, and a growing emphasis on experimental safety. This article frames this technological evolution within the context of modern parallel labeling experiments, a powerful approach for metabolic flux analysis (MFA) where multiple tracer experiments are conducted simultaneously with different isotopic labels to provide complementary and robust flux measurements [1] [3]. We detail the key experiments and methodologies that have defined this transition, providing a practical guide for researchers engaged in quantifying metabolic phenotypes.

The Radioisotope Era: Foundational Studies

The use of isotopic tracers in biology began in earnest in the 1930s. The seminal work of Schoenheimer and Rittenberg, who used deuterated fatty acids to study lipid metabolism in animals, marked the beginning of a new era in biochemistry, demonstrating the dynamic state of body constituents [1] [4] [5]. However, the simplicity of measuring radioactivity via scintillation counting made radioisotopes like 14C (Carbon-14) and 3H (Tritium) the workhorses of metabolic studies for decades [1].

- Early Applications and Parallel Experiments: Radioisotopes were intensively used to map the metabolic pathways that are now textbook knowledge. A common application involved parallel labeling experiments, where different radioactive tracers were used in separate experiments to target specific pathways. Differences in the incorporation of radioactivity into metabolites like glucose, lactate, or CO2 provided insights into pathway structure and activity [1]. For example, Horecker et al. used this approach to elucidate how pentose sugar phosphates are assembled into hexose phosphates [1].

- Methodological Limitations: While powerful for pathway elucidation, radioisotope experiments had significant constraints. Measurement of total radioactivity for an entire molecule was common, though specific carbon atoms could sometimes be assayed after chemical or enzymatic degradation of metabolites [1]. The inherent safety concerns of working with radioactive materials, combined with the inability to achieve the high-resolution, atom-specific mapping that stable isotopes would later enable, ultimately limited their scope in quantitative flux analysis.

The Transition to Stable Isotopes: A Technical Convergence

The shift from radioisotopes to stable isotopes became feasible in the 1980s, propelled by a convergence of technological and theoretical advances. This transition was critical for the development of sophisticated 13C-metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA).

Driving Forces: The move was motivated by several factors:

- Safety: Stable isotopes are non-radioactive, eliminating radiation hazards [1].

- Analytical Versatility: Stable isotopes can be detected using both Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Mass Spectrometry (MS), techniques that provide rich, atom-specific information [1] [4].

- Computational Modeling: The development of advanced computational frameworks, such as the elementary metabolite units (EMU) model, allowed researchers to efficiently simulate complex isotopic labeling patterns and translate them into precise intracellular flux maps [6] [7]. User-friendly software tools like INCA and Metran later democratized access to 13C-MFA for non-experts [7].

Seminal Technical Advances: Key milestones included the first flux measurements using 13C NMR by Malloy et al. in 1988 to investigate the citric acid cycle in the rat heart, and the establishment of a general mathematical framework for 13C flux analysis by Zupke and Stephanopoulos in the mid-1990s [4].

The following diagram illustrates the major historical and technological drivers that facilitated this pivotal transition.

Current Best Practices: Parallel Labeling Experiments and 13C-MFA

Stable isotopes, particularly 13C, are now the foundation of modern flux analysis. The gold-standard technique is 13C-MFA, which integrates data from tracer experiments, extracellular flux measurements, and a metabolic network model to generate a quantitative flux map [8] [7]. Within this framework, parallel labeling experiments have emerged as a superior approach for robust flux elucidation.

The Principle of Parallel Labeling

In parallel labeling, multiple cultures are started from the same seed culture and grown under identical conditions, with each culture receiving a different 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., [1-13C]glucose in one and [U-13C]glutamine in another) [1]. This design provides several key advantages over single-tracer experiments:

- Enhanced Flux Resolution: Different tracers probe different sections of the metabolic network, providing complementary information that collectively resolves fluxes with higher precision and reduces correlation between fluxes [1] [3].

- Network Model Validation: The ability of a single metabolic model to simultaneously fit data from multiple tracer experiments provides a powerful validation of the model's correctness [3].

- Reduced Experiment Time: Using multiple tracers that introduce isotopes at different entry points can accelerate the achievement of sufficient labeling for analysis, which is particularly beneficial for slow-growing cells [1].

The table below summarizes the main flux analysis techniques used today, highlighting the central role of stable isotopes.

Table 1: Key Methodologies in Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Method | Abbreviation | Use of Isotopic Tracers | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis | FBA | No | Yes | Not Applicable | Genome-scale flux prediction [4] |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis | 13C-MFA | Yes (e.g., 13C) | Yes | Yes | Gold standard for precise flux quantification in central metabolism [4] [8] |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA | INST-MFA | Yes (e.g., 13C) | Yes | No | Systems with a single source atom pool (e.g., autotrophic plants) or for shorter experiments [4] [6] |

| COMPLETE-MFA | COMPLETE-MFA | Yes (multiple tracers) | Yes | Yes | High-resolution flux profiling using complementary tracers [4] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Parallel Labeling Workflow

The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for a parallel labeling experiment using 13C-glucose tracers, adapted from established methodologies [4] [3] [7].

Objective: To quantify intracellular metabolic fluxes in a microbial system (e.g., E. coli or Clostridium) under defined growth conditions.

Step 1: Pre-culture and Inoculation

- Grow the organism in a defined, minimal medium with unlabeled glucose until mid-exponential phase to ensure a metabolically steady state.

- Inoculate multiple (e.g., 4) parallel bioreactors or culture vessels with the same pre-culture to minimize biological variability [1] [3].

Step 2: Parallel Tracer Administration

- Once cultures reach the desired metabolic steady state (e.g., early exponential phase), rapidly add a bolus of the labeled substrate to each culture.

- Critical: Use different, pre-determined tracers for each parallel culture. A classic combination is:

Step 3: Cultivation and Sampling

- Allow growth to continue until isotopic steady state is achieved. This is when the isotopic labeling of intracellular metabolites no longer changes over time. For many microbes, this occurs within 1-2 doublings.

- Harvest cells rapidly using a quenching solution (e.g., cold methanol) to instantly halt metabolism.

- Extract intracellular metabolites using a suitable solvent system (e.g., methanol/water/chloroform) [4].

Step 4: Mass Spectrometry Analysis

- Derivatize metabolites if necessary (e.g., for GC-MS analysis).

- Analyze metabolite extracts using GC-MS or LC-MS to measure the Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) of key intracellular metabolites. The MID represents the fraction of a metabolite pool that is unlabeled (M+0), contains one 13C atom (M+1), two (M+2), etc. [4] [7].

- Simultaneously, measure extracellular fluxes: substrate uptake rates, secretion rates of by-products (e.g., lactate, acetate), and growth rate [7].

Step 5: Computational Flux Analysis

- Use 13C-MFA software (e.g., INCA or Metran) to integrate the measured MIDs and extracellular rates into a stoichiometric metabolic model.

- The software performs a non-linear regression to find the flux map that best simulates the experimental labeling data.

- Employ statistical tests (e.g., chi-squared test) and sensitivity analysis to evaluate the goodness-of-fit and determine confidence intervals for the estimated fluxes [3] [7].

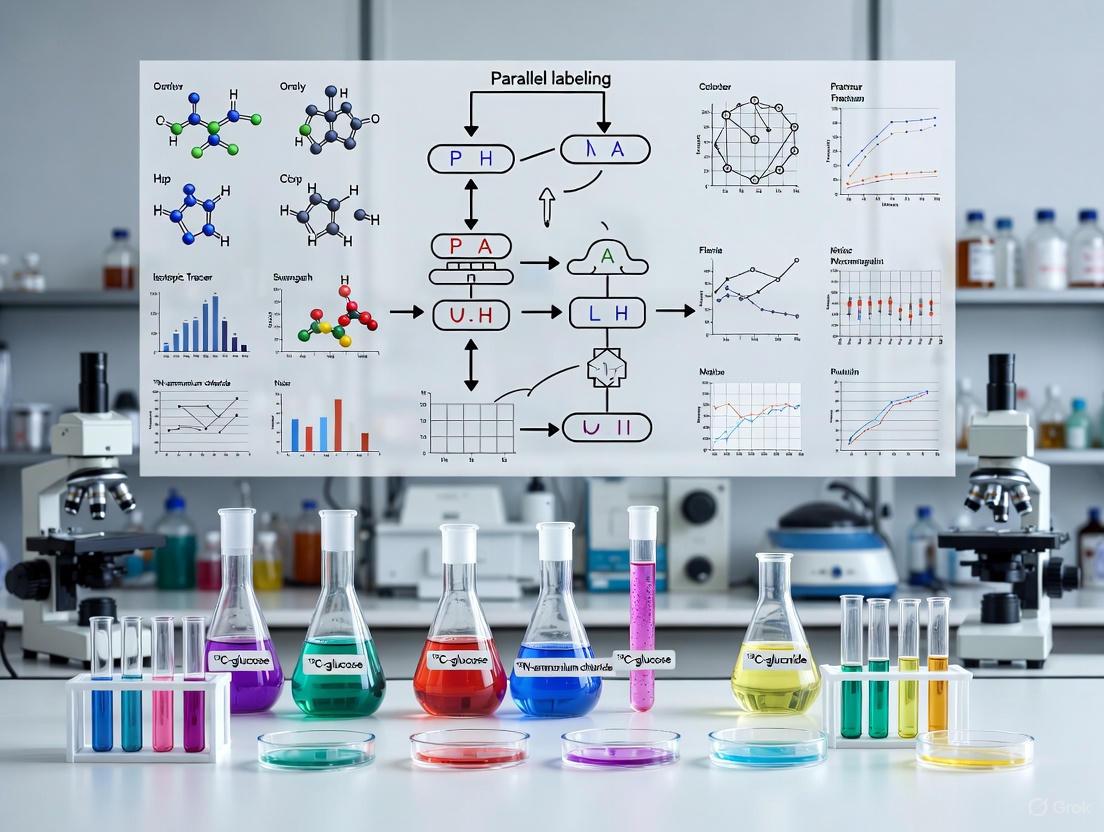

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Chemically defined tracers (e.g., [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine) that introduce the isotopic label into the metabolic network. | The core component of parallel labeling experiments; different tracers provide complementary flux information [1] [3]. |

| Defined Culture Medium | A minimal growth medium with known, precise chemical composition. Essential for controlling substrate input and performing accurate extracellular flux measurements. | Supports cell growth before and during the tracer experiment, ensuring metabolic steady state [3] [7]. |

| Quenching Solution | A cold solution (e.g., -40°C to -80°C aqueous methanol) that instantly halts all metabolic activity upon contact with cells. | Used to rapidly quench metabolism at the precise moment of sampling, preserving the in vivo labeling state [4]. |

| Metabolite Extraction Solvent | A solvent system (e.g., chloroform/methanol/water) that efficiently lyses cells and extracts polar and non-polar intracellular metabolites. | Used after quenching to release and isolate metabolites from cells for subsequent MS analysis [4]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Analytical instrument (GC-MS or LC-MS) for separating, detecting, and quantifying the mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of metabolites. | Used to generate the primary isotopic labeling data from metabolite extracts [1] [7]. |

| 13C-MFA Software (INCA/Metran) | Computational platforms that simulate isotopic labeling in a metabolic network and perform regression to estimate fluxes from experimental MIDs. | Used for data integration, model-based flux estimation, and statistical validation [6] [7]. |

Applications and Future Directions

The evolution from radioisotopes to stable isotopes has unlocked the ability to perform quantitative fluxomics across diverse fields. Parallel labeling experiments are now routinely applied in:

- Metabolic Engineering: Optimizing microbial cell factories for the production of biofuels (e.g., in Clostridium acetobutylicum [3]) and chemicals by identifying flux bottlenecks and validating engineered pathways.

- Cancer Biology: Uncovering metabolic dysregulation in cancer cells, such as aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect), reductive glutamine metabolism, and altered serine/glycine flux, to identify potential therapeutic targets [7] [9].

- Plant Science: Quantifying carbon flux during photosynthesis and understanding the partitioning of resources in crops and specialized metabolism [6] [9].

Future directions in the field include overcoming challenges related to biological variability in parallel experiments, developing improved methods for data integration, and creating rational frameworks for optimal tracer selection [1]. Furthermore, techniques like isotopically non-stationary MFA (INST-MFA) and single-cell MS are pushing the boundaries, allowing flux analysis in dynamic systems and with unprecedented spatial resolution [4] [2]. The continued refinement of these tools, built upon the historical foundation of isotopic tracing, promises to deepen our understanding of metabolic network regulation in health and disease.

Metabolic flux analysis (MFA) represents a cornerstone technique in metabolic engineering and systems biology, providing critical insights into the intracellular flow of carbon, energy, and electrons that cannot be obtained from other omics measurements alone [10]. At the heart of MFA lies the use of isotopic tracers—atoms replaced with a different isotope (e.g., ¹³C, ²H, ¹⁵N)—to probe cellular metabolism and elucidate in vivo metabolic fluxes [1] [11]. The fundamental principle is that metabolic fluxes determine the isotopic labeling patterns of intracellular metabolites; therefore, by measuring these patterns, one can infer the underlying fluxes in the metabolic network [12] [13].

Isotopic labeling experiments can be fundamentally divided into two distinct categories: single labeling experiments and parallel labeling experiments [1] [11]. In a single labeling experiment design, only one experiment is conducted, which may utilize a single labeled substrate, a mixture of tracers of the same compound, or multiple labeled substrates simultaneously [11]. In contrast, a parallel labeling experiment design involves conducting two or more tracer experiments in parallel, where each experiment uses a different tracer or tracer set but is performed under otherwise identical biological conditions, typically starting from the same seed culture to minimize biological variability [1] [11].

This application note provides a comprehensive comparative framework for these two methodological approaches, enabling researchers to make informed decisions tailored to their specific research objectives in metabolic flux analysis.

Defining the Core Methodologies

Single Labeling Experiments

Concept and Design: A single labeling experiment involves a single isotopic tracer intervention to obtain labeling data for metabolic flux analysis. The tracer can be a single isotopically labeled compound (e.g., [1,2-¹³C]glucose), a mixture of differently labeled forms of the same compound (e.g., 80% [1-¹³C]glucose + 20% [U-¹³C]glucose), or multiple labeled substrates provided simultaneously (e.g., [U-¹³C]glucose and [U-¹³C]glutamine) [1] [11].

Typical Workflow: The standard workflow initiates with the introduction of the chosen isotopic tracer to the biological system, such as a microbial batch culture or mammalian cell culture. Sufficient incubation time follows to allow for the incorporation of the tracer into cellular metabolism. Subsequently, labeled metabolites are isolated, often through extraction protocols, and the incorporation of isotopes is measured using techniques like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) or mass spectrometry (MS). The final step involves interpreting the enrichment data, either qualitatively or through quantitative model-based analysis [11].

Parallel Labeling Experiments

Concept and Design: Parallel labeling experiments (PLEs) consist of multiple, separate tracer experiments conducted concurrently. Each experiment within the parallel set utilizes a different tracer substrate or mixture, but all other culture conditions (e.g., medium composition, temperature, pH) are kept identical, and the experiments are initiated from the same seed culture to ensure minimal biological variability [1] [11]. This approach generates complementary labeling information from the different tracer entry points.

Typical Workflow: The workflow for PLEs shares the same fundamental steps as single experiments but is replicated for each tracer condition. The key differentiator lies in the experimental design and the subsequent data analysis. During analysis, labeling measurements from all parallel experiments are integrated and concurrently fitted into a comprehensive metabolic model to determine the flux map [11] [14]. This integrative analysis is a hallmark of the PLE approach.

Comparative Analysis: A Structured Framework

To systematically compare these two approaches, we have evaluated them across multiple critical dimensions relevant to experimental design and research outcomes.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Single vs. Parallel Labeling Experiments

| Evaluation Dimension | Single Labeling Experiments | Parallel Labeling Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Concept | One experiment with one tracer/mixture [11] | Multiple experiments, each with a different tracer, conducted in parallel [1] [11] |

| Information Obtained | Single set of labeling data | Complementary, synergistic labeling information from different isotopic entry points [1] [14] |

| Flux Resolution | Can be limited for specific, parallel, or reversible pathways [12] | Superior for resolving complex network features like parallel pathways and reversible reactions [1] [11] |

| Experimental Duration | Can require long labeling times for full isotope incorporation at steady state [1] | Can reduce required labeling time by introducing multiple isotope entry points [1] |

| Resource Requirements | Lower cost and labor for a single experiment | Higher cost and labor due to multiple parallel cultures and analyses [11] |

| Data Integration | Analysis of a single dataset | Requires concurrent fitting of data from all parallel experiments [11] [14] |

| Tracer Optimization | Tracer selection is critical but may be based on convention [15] | Enables tailored tracer selection to target specific fluxes; optimal tracers can be identified [14] [15] |

| Model Validation | Limited ability to detect model inconsistencies | Powerful tool for validating biochemical network models [1] [11] |

| Handling Biological Variability | Susceptible to inter-experiment variability | Mitigated by using the same seed culture and parallel execution [1] [11] |

Visualizing the Conceptual Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental structural and workflow differences between the two experimental approaches.

Practical Application and Protocols

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of isotopic labeling experiments, whether single or parallel, requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Isotopic Labeling Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ¹³C-Labeled Substrates | Serve as metabolic tracers to follow carbon flow. | [1,2-¹³C]Glucose, [U-¹³C]Glucose, [1,6-¹³C]Glucose, ¹³C-Glutamine. Optimal tracers depend on the network and fluxes of interest [14] [15]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Primary tool for measuring isotopic labeling patterns of metabolites. | GC-MS, LC-MS; provides information on position and number of labeled atoms [1] [11]. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Alternative technique for measuring isotopic enrichment. | Provides positional labeling information; can be used in conjunction with MS [1] [13]. |

| Metabolic Network Model | Computational representation of the metabolic system. | Stoichiometric matrix (S) detailing all reactions and atom transitions [13] [10]. |

| Flux Analysis Software | Computational tools for simulating labeling and estimating fluxes. | 13CFLUX2, INCA, OpenFLUX; essential for data interpretation and model fitting [12] [13]. |

| Quenching/Extraction Solutions | To rapidly halt metabolism and extract intracellular metabolites. | Cold methanol, methanol/water mixtures; critical for capturing metabolic snapshots [13]. |

Protocol for a Parallel Labeling Experiment

The following detailed protocol outlines the steps for conducting a parallel labeling experiment for ¹³C-MFA, highlighting steps that differ from a single experiment approach.

Objective: To quantify central carbon metabolic fluxes in E. coli with high precision.

Step 1: Experimental Design and Tracer Selection

- Rational Tracer Choice: Select tracers that provide complementary information. In silico analysis is highly recommended. For central carbon metabolism, optimal pairs include [1,6-¹³C]glucose and [1,2-¹³C]glucose, which have been shown to significantly improve flux precision compared to conventional tracer mixtures [14].

- Define Parallel Set: Design 2-4 parallel experiments, each with a distinct, optimally chosen glucose tracer.

Step 2: Biological Preparation

- Culture Inoculum: Prepare a single, well-mixed seed culture of the organism (e.g., E. coli BW25113). This is crucial for minimizing biological variability between the parallel experiments [1] [11].

- Medium Formulation: Prepare M9 minimal medium batches, each supplemented with a different ¹³C-labeled glucose tracer (e.g., [1,2-¹³C]glucose, [1,6-¹³C]glucose), but otherwise identical [14].

Step 3: Parallel Cultivation

- Inoculation: Inoculate each tracer-specific medium from the same seed culture flask simultaneously.

- Cultivation: Grow all parallel cultures under identical conditions (temperature, shaker speed, vessel type) to the same metabolic steady-state (e.g., mid-exponential phase).

Step 4: Metabolite Sampling and Quenching

- Harvesting: At the defined time point, rapidly quench the metabolism of all cultures simultaneously (e.g., using cold methanol).

- Extraction: Extract intracellular metabolites from each culture pellet according to standard protocols (e.g., using methanol/water extraction) [13].

Step 5: Analytical Measurement

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Measure the mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of target metabolites (e.g., amino acids, organic acids) from each extract using GC-MS or LC-MS.

Step 6: Data Integration and Flux Analysis

- Concurrent Data Fitting: Input the MIDs from all parallel experiments simultaneously into ¹³C-MFA software (e.g., 13CFLUX2, INCA).

- Flux Estimation: The software will iteratively fit a single flux map that best explains the combined labeling datasets from all tracers [11] [14].

- Validation: Use the complementary data to cross-validate the consistency of the metabolic model and the estimated fluxes.

Single and parallel labeling experiments represent distinct paradigms in the design of tracer-based metabolic studies. The single experiment approach offers a more straightforward and resource-efficient path, suitable for initial characterizations or systems where a well-understood, optimal tracer exists. In contrast, parallel labeling experiments represent a more powerful, albeit complex, strategy that yields superior flux resolution, enables robust model validation, and provides a synergistic information gain that is greater than the sum of its parts.

The choice between these frameworks should be guided by the specific research goals, the complexity of the metabolic network under investigation, and the resources available. As the field of metabolic engineering advances towards more complex systems and demands higher precision in flux quantification, parallel labeling experiments are increasingly becoming the state-of-the-art methodology for high-resolution ¹³C-metabolic flux analysis [1] [14] [10].

In metabolic flux analysis (MFA), accurate quantification of intracellular reaction rates depends critically on two fundamental physiological states: metabolic steady state and isotopic steady state [16] [17]. These parallel concepts form the bedrock of interpretable 13C-labeling experiments, particularly in the context of parallel labeling strategies for comprehensive flux elucidation [1]. Metabolic steady state describes a condition where intracellular metabolite levels and metabolic flux values remain constant over time [16]. Isotopic steady state, in contrast, is achieved when the labeling patterns of intracellular metabolites no longer change with time because the heavy isotope (e.g., 13C) has been fully incorporated throughout the metabolic network [17]. The distinction between these states is crucial—a system can be in metabolic steady state without being in isotopic steady state, but the reverse is rarely true for meaningful flux analysis [16].

For researchers investigating metabolic adaptations in disease contexts such as cancer or during therapeutic interventions, understanding and controlling for these steady states enables reliable interpretation of 13C-labeling data toward flux determination [7]. The strategic application of parallel labeling experiments, where multiple isotopic tracers are applied to the same biological system under identical physiological conditions, further enhances flux resolution by providing complementary labeling constraints that collectively improve the accuracy and precision of estimated fluxes [1].

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Definitions

Metabolic Steady State

Metabolic steady state requires that both intracellular metabolite concentrations (pool sizes) and metabolic fluxes (reaction rates) remain constant over the experimental timeframe [16]. This state is mathematically described by the mass balance equation:

[ \frac{dXi}{dt} = \sum v{production} - \sum v{consumption} - \mu Xi = 0 ]

Where (X_i) represents the concentration of metabolite (i), (v) represents metabolic fluxes, and (\mu) represents the specific growth rate (for proliferating systems) [7]. In practice, true metabolic steady state is most closely approximated in chemostat cultures where cell number and nutrient concentrations are maintained constant [16]. For most mammalian cell cultures, including cancer cell lines, experiments are typically conducted during exponential growth phase under the assumption of metabolic pseudo-steady state, where changes in metabolite levels and fluxes are minimal relative to the measurement timescale [7] [16].

Isotopic Steady State

Isotopic steady state is achieved when the isotopic labeling patterns of all intracellular metabolites become constant over time [17]. This occurs when the heavy isotope from the tracer substrate has fully propagated through the metabolic network. The mathematical condition for isotopic steady state is:

[ \frac{dMID_i}{dt} = 0 ]

Where (MID_i) represents the mass isotopomer distribution vector for metabolite (i) [16]. The time required to reach isotopic steady state varies significantly across different metabolites and depends on both the metabolic fluxes (rate of conversion) and pool sizes of the metabolite and its precursors [16]. For instance, glycolytic intermediates typically reach isotopic steady state within minutes of 13C-glucose introduction, while TCA cycle intermediates and associated amino acids may require several hours [16] [17].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Metabolic and Isotopic Steady States

| Characteristic | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Constant metabolite concentrations and fluxes over time | Constant isotopic labeling patterns over time |

| Primary Requirement | Stable physiological conditions and constant growth rate | Sufficient time for isotope propagation through network |

| Typical Achievement Method | Chemostat or exponential growth phase | Prolonged incubation with isotopic tracer |

| Mathematical Representation | (dX_i/dt = 0) for all metabolites | (dMID_i/dt = 0) for all metabolites |

| Impact on MFA | Enables stoichiometric constraints | Enables isotopic labeling constraints |

Verification Methodologies and Experimental Diagnostics

Assessing Metabolic Steady State

Verification of metabolic steady state requires monitoring key parameters over the proposed experimental timeframe:

Cell Growth Dynamics: For proliferating systems, exponential growth should be confirmed by linearity in a plot of (ln(Nx)) versus time, where (Nx) represents cell count [7]. The growth rate ((\mu)) should remain constant, calculated as:

[ \mu = \frac{\ln(N{x,t2}) - \ln(N{x,t1})}{\Delta t} ]

Nutrient Consumption and Metabolite Secretion: Extracellular flux rates should remain constant when normalized to cell number or biomass [7]. Nutrient uptake and waste secretion rates are calculated as:

[ ri = 1000 \cdot \frac{\mu \cdot V \cdot \Delta Ci}{\Delta N_x} ]

where (ri) is the external rate (nmol/10^6 cells/h), (V) is culture volume (mL), (\Delta Ci) is metabolite concentration change (mmol/L), and (\Delta N_x) is change in cell number (millions of cells) [7].

Intracellular Metabolite Pools: Targeted metabolomics should confirm stable pool sizes for key intermediates across central carbon metabolism [16].

Confirming Isotopic Steady State

Isotopic steady state verification requires time-course monitoring of labeling patterns:

- Mass Isotopomer Distribution Stability: The fractional abundance of each mass isotopomer (M+0, M+1, M+2, etc.) should reach a plateau across successive sampling time points [16]. This is particularly important for metabolites with large pool sizes or distant connectivity from the tracer entry point.

- Amino Acid Considerations: Special attention is required for amino acids that rapidly exchange with extracellular pools, as they may never reach true isotopic steady state in standard culture formats [16].

- Dynamic Sampling Strategy: Initial experiments should include multiple time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours) to establish labeling kinetics for each metabolite class [17].

Table 2: Typical Times to Reach Isotopic Steady State for Common Metabolic Pools with 13C-Glucose Tracers

| Metabolite Class | Typical Time to Isotopic Steady State | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Glycolytic Intermediates | Minutes to 1 hour | Rapid turnover due to high fluxes |

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway | 30 minutes to 2 hours | Dependent on oxidative versus non-oxidative flux partitioning |

| TCA Cycle Intermediates | 2 to 8 hours | Longer due to mitochondrial compartmentalization |

| Amino Acids Derived from TCA | 4 to 12 hours | Glutamate/glutamine labeling depends on tracer position |

| Lipid Backbones | 8 to 24 hours | Slow turnover due to large pool sizes |

Experimental Workflow for Steady State MFA

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for conducting metabolic flux analysis under both metabolic and isotopic steady state conditions:

Experimental Workflow for Steady State MFA

Parallel Labeling Experiments: Enhancing Flux Resolution

Parallel labeling experiments represent a powerful strategy whereby multiple isotopic tracers are applied to identical biological systems under the same metabolic steady state conditions [1]. This approach provides several distinct advantages for flux resolution:

- Complementary Labeling Information: Different tracers produce distinct isotopomer patterns in key metabolites, collectively constraining fluxes more effectively than any single tracer [1].

- Reduced Experimental Time: Multiple entry points for isotopes can accelerate overall labeling, potentially reducing the time required to reach isotopic steady state for specific metabolite classes [1].

- Network Model Validation: Consistent flux estimates across multiple tracer experiments validate the biochemical network model and increase confidence in the results [1].

- Resolution of Parallel Pathways: Differentially labeled substrates can resolve fluxes through parallel pathways that would be indistinguishable with a single tracer [1].

The following diagram illustrates how parallel labeling experiments provide complementary constraints on metabolic fluxes:

Parallel Labeling Enhances Flux Resolution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of steady state MFA requires careful selection of reagents and materials to ensure both metabolic and isotopic steady states are achieved and maintained throughout the experimental timeframe.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Steady State MFA

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in MFA |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Chemical purity >98%; isotopic purity >99% | Introduce measurable label into metabolic networks; common examples: [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine [1] [17] |

| Cell Culture Media | Defined formulation without unlabeled competing carbon sources | Maintain metabolic steady state; prevent dilution of isotopic label [7] |

| Continuous Culture Systems | Chemostat or perfusion bioreactors with precise environmental control | Maintain metabolic steady state over extended periods [16] |

| Quenching Solutions | Cold methanol/acetonitrile or liquid N2 | Rapidly halt metabolic activity without altering labeling patterns [17] |

| Metabolite Extraction Buffers | Methanol/water/chloroform mixtures | Extract intracellular metabolites with high efficiency and minimal degradation [17] |

| Derivatization Reagents | MSTFA, MBTSTFA, or other silylation agents | Enable GC-MS analysis by increasing metabolite volatility and detection [16] |

| Internal Standards | 13C-labeled or deuterated metabolite analogues | Normalize for extraction and analytical variability [16] |

| Mass Spectrometry Instruments | GC-MS, LC-MS, or LC-MS/MS systems with high mass resolution | Quantify isotopic labeling patterns with sufficient precision for flux calculation [7] [17] |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol A: Establishing Metabolic Steady State in Mammalian Cell Cultures

Time Requirement: 3-7 days for adaptation Critical Parameters: Consistent growth rate, stable nutrient availability, constant cell viability >90%

Preparation of Defined Media

- Formulate culture media with precisely defined carbon sources (e.g., 5.5 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine)

- Exclude serum or use dialyzed serum to remove undefined carbon sources

- Supplement with all essential amino acids, vitamins, and growth factors

Culture Adaptation

- Seed cells at appropriate density (typically 0.5-1.0 × 10^5 cells/mL)

- Maintain cells in exponential growth phase through scheduled subculturing

- Monitor growth kinetics through daily cell counting

- Calculate specific growth rate (μ) using: ( \mu = \frac{\ln(N{x,t2}) - \ln(N{x,t1})}{\Delta t} )

- Continue adaptation until growth rate variation is <5% across three consecutive passages

Metabolic Steady State Verification

- Measure nutrient consumption and metabolite secretion rates at 12-hour intervals

- Confirm linearity in semi-log plot of cell growth over 48-72 hours

- Assess intracellular metabolite pool stability via targeted metabolomics

Protocol B: Achieving Isotopic Steady State for 13C-MFA

Time Requirement: 4-24 hours (tracer-dependent) Critical Parameters: Tracer selection, metabolite pool sizes, pathway connectivity

Tracer Introduction

- Rapidly replace existing media with pre-warmed media containing isotopic tracer

- Maintain identical nutrient concentrations and physiological conditions

- Use tracer concentrations that match natural abundance substrate levels (e.g., 5.5 mM [U-13C]glucose)

Time-Course Sampling

- Collect samples at strategic time points (0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 480 minutes post-tracer addition)

- Rapidly quench metabolism using cold methanol (-40°C) or liquid nitrogen

- Extract intracellular metabolites using methanol/water/chloroform system

- Derivatize metabolites for GC-MS analysis when applicable

Isotopic Steady State Determination

- Analyze mass isotopomer distributions for key pathway intermediates

- Identify plateau in labeling kinetics for each metabolite class

- Confirm stable labeling patterns across consecutive time points (variation <2%)

Protocol C: Integrated Steady State MFA Using Parallel Labeling

Time Requirement: 7-14 days complete workflow Critical Parameters: Biological reproducibility, analytical precision, computational validation

Experimental Design

- Select complementary tracers based on target pathway(s)

- Establish identical biological replicates for each tracer condition

- Include natural abundance controls for background correction

Parallel Labeling Execution

- Apply Protocol A to establish metabolic steady state across all conditions

- Apply Protocol B with different tracers to parallel cultures

- Ensure identical sampling protocols and processing across conditions

Data Integration and Flux Analysis

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Even with careful execution, several common challenges may arise during steady state MFA experiments:

- Failure to Reach Metabolic Steady State: Often caused by inconsistent culture conditions or inadequate adaptation time. Solution: Extend adaptation period and rigorously control environmental parameters.

- Prolonged Isotopic Labeling Kinetics: Typically occurs with metabolites having large pool sizes or compartmentalization. Solution: Extend labeling time or select tracers with more direct pathway connectivity.

- Amino Acid Labeling Artifacts: Caused by rapid exchange with unlabeled extracellular pools. Solution: Use tracer mixtures that account for exchange or employ INST-MFA methods [16].

- Inconsistent Flux Estimates Across Parallel Tracers: Suggests network model incompleteness or biological variability. Solution: Verify network model completeness and ensure true biological replication.

Quality control metrics should include: growth rate consistency (<5% variation), labeling measurement precision (<1% coefficient of variation for technical replicates), and flux estimation confidence intervals (<20% relative error for central carbon metabolism fluxes).

The Role of Tracers in Elucidating Pathway Structure and Activity

The use of isotopic tracers represents a foundational methodology for investigating the dynamic nature of metabolic pathways in living systems. Unlike static "snapshot" measurements of metabolite concentrations, tracer techniques enable direct interrogation of metabolic pathway activity by tracking the incorporation of stable or radioactive isotopes into downstream metabolites [18] [5]. This approach has revolutionized our understanding of metabolic flux, revealing that biological compounds exist in a constant state of turnover—a concept elegantly described by Schoenheimer's "The Dynamic State of Body Constituents" [5]. The fundamental principle underlying tracer methodology involves introducing an isotopically labeled substrate into a biological system and monitoring its metabolic fate through analytical techniques such as mass spectrometry or nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Isotope labeling experiments can be conducted as single tracer investigations or as parallel labeling experiments, where multiple experiments are performed under identical conditions using different substrate labeling patterns [1]. Parallel labeling represents a particularly powerful approach in metabolic flux analysis, as it allows researchers to tailor specific isotopic tracers to different parts of metabolism, thereby providing complementary information that enhances flux precision and pathway coverage [1] [14]. This strategic use of multiple tracers has become increasingly important for deciphering complex metabolic networks in various physiological and pathological states, including cancer, diabetes, and microbial fermentation [1] [19].

Fundamental Principles of Tracer Design

Tracer Selection Criteria

The strategic selection of isotopic tracers is paramount for obtaining meaningful flux information in metabolic studies. Optimal tracer design requires careful consideration of several factors, including the specific metabolic pathways of interest, the labeling pattern of the substrate, and the analytical methodology employed for detection. Research has demonstrated that doubly (^{13}\text{C})-labeled glucose tracers, particularly [1,6-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose, [5,6-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose, and [1,2-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose, consistently produce the highest flux precision across diverse metabolic systems [14]. These tracers outperform commonly used tracer mixtures such as 80% [1-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose + 20% [U-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose, with combined analysis of [1,6-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose and [1,2-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose improving flux precision by nearly 20-fold compared to traditional approaches [14].

The performance of different tracers can be evaluated using precision scoring metrics that account for the nonlinear behavior of flux confidence intervals. This scoring system calculates the average of individual flux precision scores for multiple fluxes of interest, with each score representing the squared ratio of the 95% flux confidence interval obtained for a reference tracer experiment relative to the tracer experiment being evaluated [14]. This approach avoids potential biases introduced by flux normalization and provides a robust method for comparing tracer effectiveness.

Tracer Types and Applications

Stable isotopically labeled tracers are molecules with one or more heavier stable isotopes (e.g., (^{13}\text{C}), (^{2}\text{H}), or (^{15}\text{N})) incorporated at specific positions [5]. These tracers can be administered in the chemical form of the tracer itself (e.g., (^{13}\text{C})-glucose) or as precursor molecules like heavy water (deuterium oxide, (^{2}\text{H}_{2}\text{O})) that generate metabolic tracers in vivo [5]. The calculation of substrate kinetics relies on two basic tracer models: (1) tracer dilution and (2) tracer incorporation, which can be further divided into single-pool versus multiple-pool models and single-precursor versus multiple-precursor approaches [5].

Table 1: Common Stable Isotope Tracers and Their Applications

| Tracer | Labeling Pattern | Primary Applications | Key Metabolic Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | [U-(^{13}\text{C})] | Glycolysis, PPP, TCA cycle | General carbon flow through central metabolism |

| Glucose | [1,2-(^{13}\text{C})] | Parallel labeling studies | Complementary flux information |

| Glucose | [1,6-(^{13}\text{C})] | High-resolution MFA | Optimal flux precision in parallel experiments |

| Glutamine | [(^{13}\text{C}{5}), (^{15}\text{N}{2})] | Anaplerosis, TCA cycle, GSH synthesis | Nitrogen and carbon metabolism |

| Aspartate | [(^{13}\text{C}_{4}), (^{15}\text{N})] | Amino acid metabolism, purine synthesis | Aspartate aminotransferase activity |

| Arginine | [(^{13}\text{C}{6}), (^{15}\text{N}{4})] | Nitrogen metabolism, TCA cycle | Arginase activity, urea cycle |

Different labeling patterns provide distinct advantages for investigating specific metabolic pathways. For example, [1,2,3-(^{13}\text{C}{3})]glucose enables differentiation between glycolytic and pentose phosphate pathway flux through analysis of the lactate M+2 to M+3 ratio, as the (^{13}\text{C}) at position one is liberated as (^{13}\text{CO}{2}) during the oxidative phase of the PPP [19]. This specific labeling pattern generates valuable information about pathway interactions that would be difficult to obtain with uniformly labeled substrates.

Experimental Protocols for Parallel Labeling Experiments

Sample Processing and Preparation

Proper sample processing is critical for maintaining biochemical integrity and ensuring accurate metabolite measurement in tracer experiments. The key goals of sample processing include: (1) maintaining biochemical integrity during sampling; (2) efficiently and reproducibly recovering metabolites from biospecimens with high throughput; (3) increasing metabolome coverage from limited sample quantities; (4) determining trace-level or labile metabolites in the presence of stable and abundant species; (5) enabling large-scale metabolite identification and automation; (6) obtaining structural information for unknown metabolites; and (7) facilitating large-scale metabolite quantification without authentic standards [20].

For mammalian cell culture experiments, the following protocol is recommended:

- Tracer Administration: Prepare media containing isotopically labeled substrates at physiological concentrations (e.g., 5-10 mM for glucose, 2-4 mM for glutamine). Use parallel cultures for different tracer conditions to minimize biological variability.

- Incubation: Allow sufficient time for isotopic steady state to be reached (typically 2-3 cell doublings for mammalian cells). For in vivo studies, isotopic steady state should be confirmed through time-course measurements [18].

- Quenching: Rapidly cool cells or tissues to arrest metabolism using pre-cooled saline or specialized quenching solutions.

- Extraction: Use dual-phase extraction with methanol/chloroform/water for comprehensive coverage of polar and non-polar metabolites. For targeted analysis of central carbon metabolites, polar extraction with 80% methanol is sufficient.

- Storage: Maintain samples at -80°C until analysis to prevent degradation.

For tissue samples from animal models, flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen followed by pulverization under continuous cooling ensures homogeneous powder for extraction. In clinical settings, blood samples should be collected in pre-chilled tubes containing enzyme inhibitors, and plasma should be separated immediately by centrifugation at 4°C [20] [19].

Analytical Methodologies

Mass spectrometry-based approaches have become the dominant technology for tracer analysis due to their superior sensitivity, rapid data acquisition, and compatibility with chromatographic separation. The two primary configurations are:

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS):

- Chromatography: Utilize reverse-phase (C18) chromatography for lipid-soluble metabolites and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) for polar metabolites. Ultra-high-performance LC (UHPLC) provides improved resolution and throughput.

- Mass Analysis: High-resolution mass spectrometers (Orbitrap, FT-ICR) enable unambiguous assignment of isotopic enrichment with resolving power >200,000 required for distinguishing (^{13}\text{C}) or (^{15}\text{N}) enrichments [20].

- Data Acquisition: Full-scan MS1 mode for untargeted analysis; parallel reaction monitoring for targeted quantification of specific metabolic pathways.

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS):

- Derivatization: Use N-methyl N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MTBSTFA) to render metabolites volatile and generate a "pseudo-molecular ion" that harbors the entire original metabolite for isotopologue analysis [20].

- Applications: Particularly suitable for central carbon metabolites (organic acids, sugars, amino acids) but limited to metabolites <800 Da.

Spatial Isotope Tracing: Recent advances include ambient mass spectrometry imaging (MSI)-based isotope tracing, which enables in situ metabolic characterization. Tools like MSITracer leverage spatial distribution differences between isotopically labeled metabolites to probe metabolic activity across tissue microenvironments [18]. This approach has been used to characterize fatty acid metabolic crosstalk between liver and heart, as well as glutamine metabolic exchange across kidney, liver, and brain [18].

Data Analysis and Flux Calculation

The analysis of isotopic labeling data requires specialized computational tools to extract meaningful biological information. Key steps in the workflow include:

Isotopologue Extraction: Automated identification of isotopic peaks from raw mass spectrometry data using tools like MSITracer for MSI data or MetTracer for LC-MS data [18]. This involves matching measured and theoretical m/z values within a 5 ppm error range and applying natural isotope abundance corrections.

Metabolic Flux Analysis: Implementation of (^{13}\text{C}) metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) using computational frameworks such as Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU) to model isotopic distributions and estimate intracellular fluxes [14]. This involves solving inverse problems where measured isotopologue distributions are used to compute metabolic reaction rates.

Statistical Evaluation: Application of precision scoring metrics to evaluate flux determination quality. The precision score (P) is calculated as:

(P = \frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n} pi) with (pi = \left( \frac{(UB{95,i} - LB{95,i}){ref}}{(UB{95,i} - LB{95,i})_{exp}} \right)^2)

where (UB{95,i}) and (LB{95,i}) represent the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval for flux i [14].

For parallel labeling experiments, a synergy scoring metric is used to identify optimal tracer combinations that provide complementary information and improve overall flux resolution [14]. This approach has revealed that [1,6-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose and [1,2-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose represent the optimal tracer pair for parallel labeling experiments, offering nearly 20-fold improvement in flux precision compared to traditional single tracer approaches [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Tracer Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | [1,6-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose, [U-(^{13}\text{C})]glutamine, [(^{13}\text{C}{5}),(^{15}\text{N}{2})]glutamine | Metabolic fate mapping, flux quantification | >99% isotopic purity; position-specific labeling critical |

| Chromatography Columns | HILIC, C18 reverse phase, ion pairing | Metabolite separation prior to MS analysis | Column chemistry determines metabolite coverage |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | (^{13}\text{C})-labeled internal standards | Absolute quantification, instrument calibration | Should elute at same time as analytes of interest |

| Extraction Solvents | Methanol, chloroform, acetonitrile | Metabolite extraction from biological matrices | Pre-chilled to -20°C for quenching metabolism |

| Derivatization Reagents | MTBSTFA, MSTFA | Volatilization for GC-MS analysis | Minimize fragmentation for isotopologue analysis |

| Computational Tools | MSITracer, MetTracer, X13CMS | Isotopologue extraction, natural abundance correction | MSI-specific vs. LC-MS/GC-MS tools |

| Flux Analysis Software | INCA, 13C-FLUX, OpenFLUX | Metabolic network modeling, flux calculation | EMU framework reduces computational complexity |

Successful tracer experiments require not only high-quality reagents but also appropriate analytical instrumentation. Fourier-transform class mass spectrometers (FT-ICR, Orbitrap) provide the high resolution (>200,000) necessary to unambiguously analyze stable isotope enrichments such as (^{13}\text{C}) or (^{15}\text{N}), which is particularly important for complex isotopologue analysis [20]. For large-scale metabolite profiling, direct infusion by nanoelectrospray without chromatographic separation may be employed to analyze numerous isotopologues across different metabolite classes in a high-throughput manner [20].

Applications in Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Elucidating Tissue-Specific Metabolism

Spatial isotope tracing approaches have revealed remarkable metabolic heterogeneity across different tissues and organs. Following infusion of U-(^{13}\text{C}) glucose in mice, the liver contained the greatest abundance of (^{13}\text{C}) isotopologues, while muscle contained the least [18]. Cross-organ analysis demonstrated that nearly three-quarters of labeled metabolites were uniquely detected in only one tissue, highlighting the specialized metabolic functions of different organs [18]. This compartmentalized metabolic profiling provides critical insights into inter-tissue metabolic crosstalk, such as fatty acid metabolic exchange between liver and heart, and glutamine metabolic shuttling among kidney, liver, and brain [18].

Investigating Cancer Metabolism

Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM) approaches have uncovered critical metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer. For example, tracking seven isotopic forms of citrate enabled researchers to resolve the contribution of anaplerotic pyruvate carboxylation to the Krebs cycle and uncover a novel Krebs cycle-independent pathway important for MYC oncogene function [20]. Similarly, spatial isotope tracing has demonstrated that tumor burden significantly influences the host's hexosamine biosynthesis pathway, and that glucose-derived glutamine released from the lung serves as a potential source for tumor glutamate synthesis [18]. These findings highlight how tracer methodology can reveal metabolic adaptations in pathological states.

Assessing Dynamic Metabolic Homeostasis

Tracer techniques provide unique insights into the continuous turnover of biological compounds that maintains dynamic homeostasis. For example, in healthy adults, muscle mass remains constant because protein breakdown is balanced by continuous protein synthesis [5]. Different rates of protein turnover can affect tissue quality even when pool sizes remain constant, as demonstrated by the positive relationship between muscle quality (strength normalized to mass) and protein turnover rates [5]. This dynamic perspective explains why static measurements often fail to accurately reflect metabolic status, with documented mismatches between enzyme abundance or activation states and actual metabolic flux rates [5].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The field of tracer methodology continues to evolve with emerging technologies and applications. Spatial metabolomics approaches now enable comprehensive tracing of metabolic fate within tissues, characterizing metabolic crosstalk between organs with unprecedented resolution [18]. The integration of parallel labeling experiments with computational flux analysis has established a new standard for precision in metabolic engineering and systems biology [14]. These advances are particularly valuable for investigating complex metabolic diseases, where multiple pathways interact to produce pathological phenotypes.

Future developments will likely focus on expanding the scope of tracer experiments to include more complex isotopic labeling patterns, improving computational tools for data integration from parallel experiments, and developing novel tracers for emerging areas of metabolism such as epigenetic regulation and immunometabolism. The application of these methodologies in clinical settings holds particular promise for personalized medicine, where individual metabolic phenotypes could inform targeted therapeutic strategies for cancer, metabolic disorders, and other diseases characterized by dysregulated metabolism [19]. As tracer methodology becomes more accessible and comprehensive, it will continue to transform our understanding of metabolic pathway structure and activity in health and disease.

Within the framework of parallel labeling experiments for metabolic flux analysis (MFA), advanced analytical technologies are indispensable for decoding the metabolic state of biological systems. Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy serve as the two cornerstone analytical platforms for measuring stable-isotope incorporation into intracellular metabolites [21] [22]. These techniques transform the raw data from tracer experiments—the isotopic labeling patterns of metabolites—into quantifiable fluxes that describe the in vivo activity of metabolic pathways [23]. The evolution of these technologies, particularly the development of tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) and high-field NMR, has dramatically increased the information content that can be extracted from labeling experiments [23] [1]. This application note details the specific methodologies and protocols for employing MS and NMR within the context of parallel labeling experiments, a approach recognized as the gold standard for high-resolution metabolic flux analysis [24] [25].

The choice between MS and NMR is governed by the specific requirements of the flux analysis project, as each technique offers a distinct set of advantages. The table below provides a structured comparison to guide researchers in selecting and deploying the appropriate technology.

Table 1: Comparison of MS and NMR for 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Feature | Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role in MFA | Measures mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs)—the fractions of a metabolite with different numbers of heavy isotopes [24] [25]. | Determines positional isotopomer distributions—the location of heavy atoms at specific positions within a metabolite molecule [22] [25]. |

| Key Strength | High sensitivity, high throughput, and ability to measure many metabolites simultaneously, even at low concentrations [23]. | Provides direct, non-destructive information on the position of the labeled carbon, which is highly informative for resolving certain fluxes [25]. |

| Throughput | High | Low to Moderate |

| Sample Destruction | Destructive | Non-destructive |

| Quantitative Data | Mass isotopomer Fractions (M+0, M+1, ..., M+n) [24] | Positional Enrichment (e.g., 13C enrichment at C1, C2, etc.) [25] |

| Flux Resolution | Excellent for upper glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathways when using optimal tracers [24]. | Excellent for lower metabolism (TCA cycle, anaplerotic reactions) [24]. |

| Common Interfaces | GC-MS, LC-MS [23] [22] | 1D 1H, 2D 1H-13C HSQC [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Integrated MS/NMR Workflow

This section outlines a standardized protocol for a parallel labeling experiment, from cell culture to data acquisition, integrating both MS and NMR measurements to maximize flux resolution [24] [25].

Phase 1: Design and Execution of Parallel Labeling Experiments

- Tracer Selection: Utilize a set of complementary tracers. For E. coli, a powerful combination includes:

- 75% [1-13C]glucose + 25% [U-13C]glucose (optimal for upper metabolism)

- [4,5,6-13C]glucose (optimal for lower metabolism) [24]

- Biological Replicates: For each tracer condition, prepare a minimum of n=3 parallel cultures inoculated from the same seed culture to minimize biological variability [1].

- Cell Cultivation: Grow cells in controlled bioreactors (e.g., aerated mini-bioreactors at 37°C). For photomixotrophic microbes like Synechocystis, use a two-step labeling protocol to ensure isotopic steady state is achieved: first, a 13C pre-culture, then inoculation into a main 13C culture [25].

- Metabolite Quenching and Extraction:

- Quenching: Rapidly cool culture samples using cold methanol (60%, v/v, at -40°C) to halt metabolic activity instantly.

- Extraction: Use a mixture of chloroform, methanol, and water (1:3:1 ratio) to extract intracellular metabolites. Centrifuge to separate phases; the aqueous phase contains polar metabolites for analysis [26].

Phase 2: Metabolite Analysis via Mass Spectrometry

- Sample Derivatization: For GC-MS analysis, derivatize polar extracts. A common method is to use N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) to form trimethylsilyl (TMS) derivatives, which confer volatility [25].

- GC-MS Analysis:

- Instrument: Gas Chromatograph coupled to a Single Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer.

- GC Column: DB-5MS or equivalent (30 m length, 0.25 mm diameter).

- Method: Use a splitless injection mode and a temperature ramp (e.g., 60°C to 300°C at 10°C/min).

- Data Acquisition: Acquire data in scan mode (e.g., m/z 50-600). Quantify the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) for key proteinogenic amino acids and central metabolites by integrating specific fragment ions [24] [25].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis (for enhanced information):

- Instrument: Liquid Chromatograph coupled to a Tandem Mass Spectrometer.

- Method: Utilize hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) for separation. Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) can be used to obtain MS/MS spectra for structural confirmation and more detailed labeling analysis [23].

Phase 3: Metabolite Analysis via NMR Spectroscopy

- Sample Preparation: Lyophilize the aqueous metabolite extract and resuspend in deuterated buffer (e.g., D2O with 0.25 mM DSS as an internal chemical shift reference) [25].

- 1H NMR Acquisition:

- Instrument: High-field NMR spectrometer (e.g., 600 MHz).

- Experiment: Standard 1D 1H NMR with water suppression (e.g., presat).

- Parameters: 90° pulse, 2-4s relaxation delay, 128-256 scans. This provides labeling information from the 1H satellites of the spectra [25].

- 2D 1H-13C HSQC Acquisition:

- Experiment: 2D Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC) spectroscopy.

- Parameters: Focus on the aliphatic carbon region. This experiment directly correlates 1H and 13C nuclei, providing site-specific 13C enrichment data for metabolites like amino acids, which is crucial for resolving fluxes in the TCA cycle [25].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated protocol from tracer experiment to flux estimation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of parallel labeling MFA relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details the key components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Parallel Labeling MFA

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Carbon sources for parallel labeling experiments to introduce measurable isotopic patterns [24]. | [1-13C]Glucose (99 atom% 13C),\n[U-13C]Glucose (98.5%),\n[4,5,6-13C]Glucose (99.9%) [24]. |

| Stable Growth Medium | Provides defined nutritional environment for reproducible cell culture [24]. | M9 minimal medium for E. coli; BG-11 for cyanobacteria [24] [25]. |

| Quenching Solvent | Rapidly halts metabolic activity to preserve in vivo labeling state [26]. | Cold aqueous methanol (60%, v/v, at -40°C). |

| Extraction Solvent | Disrupts cells and extracts intracellular metabolites for analysis [26]. | Chloroform:MeOH:H2O mixture (1:3:1 ratio). |

| Derivatization Reagent | Chemically modifies metabolites for volatility in GC-MS analysis [25]. | N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA). |

| Deuterated Solvent | Provides a signal for NMR spectrometer lock and enables NMR analysis [25]. | Deuterium oxide (D2O) with 0.25 mM DSS. |

Mass Spectrometry and NMR Spectroscopy are not merely analytical tools but are fundamental pillars that enable the power of parallel labeling experiments in metabolic flux analysis. MS provides high-sensitivity, high-throughput data on the quantitative abundance of mass isotopomers, while NMR delivers unique, unambiguous information on the positional fate of labeled atoms [24] [25]. As demonstrated in studies ranging from E. coli to cancer cell lines, the integration of data from both platforms provides complementary constraints that lead to significantly improved flux precision and observability, especially for complex network models [24] [27]. By adhering to the detailed protocols and leveraging the essential reagents outlined in this document, researchers can robustly apply these advanced analytical techniques to illuminate the functional metabolic phenotype of their biological system.

Designing and Executing Parallel Labeling Experiments: Methods and Real-World Applications

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a forceful tool for quantifying in vivo metabolic pathway activity by tracing the fate of stable isotope-labeled carbon atoms through cellular metabolic networks [22]. In biopharmaceutical development, 13C-MFA provides a comprehensive perspective of host metabolism, enabling researchers to quantify fluxes within intracellular metabolic networks and identify desirable metabolic phenotypes in production cell lines [28]. The emergence of parallel labeling experiments – where multiple tracer studies are conducted simultaneously under identical biological conditions – represents a significant advancement in flux analysis methodology [1] [11]. This COMPLETE-MFA (COMPlementary Parallel Labeling Experiments Technique for Metabolic Flux Analysis) approach synergistically integrates data from multiple tracers to dramatically improve flux resolution, precision, and observability, particularly for challenging metabolic systems [24]. This protocol details the comprehensive workflow for implementing 13C-MFA with a focus on parallel labeling strategies to obtain high-resolution flux maps for industrial cell line optimization and bioprocess development.

The complete 13C-MFA workflow integrates both experimental and computational components to transform raw labeling data into quantitative flux estimates [28]. The process begins with careful experimental design and culminates in statistical validation of flux results, with parallel labeling experiments enhancing every stage of this pipeline.

Figure 1: The comprehensive 13C-MFA workflow, highlighting the sequential steps from experimental design through flux validation. Parallel labeling experiments enhance multiple stages of this pipeline, particularly experimental design, model fitting, and statistical validation.

Experimental Design and Tracer Selection

Principles of Parallel Labeling Design

Parallel labeling experiments involve conducting multiple tracer studies simultaneously using the same biological source material to minimize variability [1]. In this approach, each experiment differs only in the composition of the isotopic tracer(s) used, while maintaining identical culture conditions, growth phase, and environmental parameters [11]. This strategy generates complementary labeling information that collectively constrains the flux solution space more effectively than any single tracer experiment could achieve alone [24].

Rational Tracer Selection

Strategic selection of isotopic tracers is paramount for successful COMPLETE-MFA. Different tracers probe distinct metabolic pathways and network nodes with varying effectiveness, meaning no single tracer optimally resolves all fluxes in a complex network [24]. The table below summarizes tracer performance characteristics for resolving fluxes in different metabolic regions.

Table 1: Performance characteristics of common isotopic tracers for resolving fluxes in different metabolic regions

| Tracer Composition | Glycolysis & PPP Resolution | TCA Cycle Resolution | Anaplerotic Reactions Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C]Glucose | Moderate | Poor | Poor | Glycolytic flux prelimitation |

| [4,5,6-13C]Glucose | Poor | Excellent | Good | Lower glycolysis & TCA cycle |

| [U-13C]Glucose | Good | Good | Moderate | General purpose tracing |

| [1-13C]Glucose + [U-13C]Glucose (4:1) | Excellent | Moderate | Moderate | Upper metabolism focus |

| [1-13C]Glucose + [4,5,6-13C]Glucose (1:1) | Good | Excellent | Good | COMPLETE-MFA applications |

| Multiple 13C-Glutamine tracers | Moderate | Excellent | Good | Anaplerosis & TCA cycle |

Tracer selection should be guided by the specific fluxes of interest and the known limitations of single tracer experiments. For comprehensive flux mapping, combining tracers that optimally probe upper metabolism (e.g., 75% [1-13C]glucose + 25% [U-13C]glucose) with those effective for lower metabolism (e.g., [4,5,6-13C]glucose) provides complementary constraints that significantly enhance overall flux resolution [24].

Materials and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for parallel labeling 13C-MFA experiments

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose, [1,2-13C]Glucose, [4,5,6-13C]Glucose, 13C-Glutamine | Carbon sources with defined labeling patterns to trace metabolic pathways |

| Cell Culture Materials | Defined growth medium (e.g., M9 minimal medium), mini-bioreactor systems, filtration sterilization equipment | Maintain consistent culture conditions across parallel experiments |

| Analytical Standards | Deuterated internal standards, unlabeled metabolite standards | Quantification and retention time calibration for MS analysis |

| Sample Preparation | Methanol, chloroform, water (for metabolite extraction), quenching solutions (cold aqueous methanol) | Rapid metabolism inactivation and metabolite extraction |

| Instrumentation | GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR systems | Measurement of isotopic labeling patterns in metabolites |

Step-by-Step Protocols

Protocol: Parallel Labeling Experiment Setup

Preparation of Tracer Stocks: Prepare 20% (w/v) glucose stock solutions for each isotopic tracer in distilled water. For tracer mixtures, combine appropriate stock solutions at desired ratios. Sterilize all solutions by filtration (0.2 µm) [24].

Inoculum Culture: Start biological replicates from a single homogeneous seed culture to minimize variability. Grow overnight in defined medium with unlabeled carbon source until early exponential phase [24].

Parallel Culture Initiation: Transfer equal aliquots from the seed culture to multiple parallel bioreactors or culture vessels containing glucose-free medium. Add different isotopic tracers to each parallel culture from the prepared stock solutions, maintaining identical initial substrate concentrations across all conditions [1] [24].

Culture Monitoring: Maintain cultures at optimal growth conditions (e.g., 37°C for E. coli, appropriate temperature for mammalian cells) with controlled aeration. Monitor cell growth by measuring optical density (OD600) and substrate consumption throughout the experiment [24].

Protocol: Metabolite Sampling and Extraction

Rapid Sampling: Collect samples during mid-exponential growth phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5-1.0 for microbial cultures) using rapid sampling techniques to ensure metabolic quenching within 1-2 seconds [29].

Metabolic Quenching: Immediately transfer culture aliquots to cold (-40°C) aqueous methanol (60%) for rapid metabolism inactivation. Maintain sample temperature below -20°C throughout processing [29].

Metabolite Extraction:

- Add chloroform and water to achieve final methanol:chloroform:water ratio of 5:2:2

- Vortex vigorously for 30 minutes at 4°C

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C

- Collect polar (upper) phase for central metabolite analysis

- Evaporate solvents under nitrogen stream and reconstitute in appropriate MS-compatible solvent [30]

Protocol: Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Sample Derivatization: For GC-MS analysis, derivative polar metabolites using MSTFA (N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide) at 60°C for 60 minutes to form trimethylsilyl derivatives [30].

Instrument Calibration:

- Analyze natural abundance standards to establish baseline correction factors

- Use internal standards to correct for instrumental drift

- Generate calibration curves for absolute quantification [30]

Data Acquisition:

Protocol: Data Processing and Mass Isotopomer Calculation

Raw Data Preprocessing:

- Extract chromatographic peaks and integrate peak areas

- Correct for naturally occurring isotopes using experimentally determined standards from unlabeled cell extracts [30]

Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) Calculation:

- For each metabolite fragment, extract ion chromatograms for M0, M1, M2, ... Mn isotopomers

- Normalize mass isotopomer distributions by dividing each isotopomer intensity by the sum of all isotopomer intensities (M0 to Mn)

- Apply natural abundance correction using matrix operations [30]

Data Quality Assessment:

- Check that summed normalized MID values approach 1.0 (allowing for measurement error)

- Identify and exclude metabolites with poor signal-to-noise ratio (<10:1) [30]

Metabolic Network Modeling and Flux Estimation

Model Construction

Construct a stoichiometric model of central carbon metabolism including:

- Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis

- Pentose phosphate pathway

- Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle

- Anaplerotic/cataplerotic reactions

- Amino acid biosynthetic pathways

- Transport reactions [28] [22]

The model must include atom transition mappings for each reaction, describing how carbon atoms are rearranged through metabolic transformations, which is essential for simulating isotopic labeling patterns [22].

Computational Flux Estimation

Flux estimation formalizes as an optimization problem:

Where v represents metabolic flux vector, S is the stoichiometric matrix, x is simulated labeling, xM is measured labeling, and Σε is the measurement covariance matrix [22].

The COMPLETE-MFA approach integrates labeling data from all parallel experiments into a single optimization, substantially improving flux resolvability compared to single-tracer analyses [24].

Figure 2: Data integration in COMPLETE-MFA. Labeling data from multiple parallel experiments are simultaneously fitted to estimate fluxes through non-linear optimization, significantly enhancing flux resolution compared to single-tracer analyses.

Data Analysis and Validation

Statistical Validation and Goodness-of-Fit

The χ²-test of goodness-of-fit serves as the primary statistical validation method in 13C-MFA:

- Calculate the residual sum of squares (RSS) between measured and simulated labeling patterns

- Compare RSS to the χ² distribution with appropriate degrees of freedom (number of measurements - number of estimated parameters)

- A p-value > 0.05 indicates the model adequately fits the experimental data within measurement uncertainty [31]

Flux Uncertainty Analysis

Evaluate flux estimation precision using:

- Monte Carlo sampling approaches that propagate measurement uncertainty to flux confidence intervals

- Parameter continuation methods to determine individual flux confidence intervals

- Sensitivity analysis to identify which measurements most strongly constrain each flux [31] [32]

Parallel labeling experiments typically yield substantially narrower flux confidence intervals compared to single-tracer designs, particularly for exchange fluxes and parallel pathway fluxes [24].

Advanced Applications and Methodological Extensions

INST-MFA for Complex Systems

Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) extends the methodology to systems where achieving isotopic steady state is impractical. INST-MFA analyzes the time-course of isotopic labeling immediately after introducing tracers, requiring precise measurement of metabolite pool sizes and rapid sampling protocols [33] [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for:

- Slow-growing cells

- Systems with large metabolite pools

- Transient metabolic states

- Plant and mammalian cell cultures [33]

Bayesian Flux Inference

Recent methodological advances incorporate Bayesian statistical approaches to flux inference, offering several advantages:

- Unified treatment of data and model selection uncertainty

- Capability for multi-model flux inference through Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA)

- More robust handling of bidirectional reaction steps

- Explicit quantification of flux estimation uncertainty [32]

Bayesian methods are particularly valuable when comparing alternative network models or when dealing with limited labeling data, as they avoid overconfidence in single model structures [32].

Concluding Remarks