Precursor Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Secondary Metabolite Production in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to enhance precursor availability for optimizing secondary metabolite production, a critical focus for researchers and drug development professionals.

Precursor Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Secondary Metabolite Production in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to enhance precursor availability for optimizing secondary metabolite production, a critical focus for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biosynthetic pathways and key precursor molecules, details practical methodological approaches including precursor feeding and genetic engineering, addresses common challenges with advanced optimization techniques, and validates strategies through comparative analysis of successful case studies. By synthesizing the latest research, this resource aims to equip scientists with actionable knowledge to overcome yield limitations and accelerate the discovery and production of valuable bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical applications.

Understanding Precursor Molecules and Core Biosynthetic Pathways in Secondary Metabolism

Troubleshooting Guide: Precursor Feeding and Availability

Common Problem 1: Low Yield of Target Secondary Metabolites

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient precursor uptake by plant cells or microbial hosts.

- Solution: Optimize feeding timing; add precursors during the late exponential or early stationary growth phase for microbes, or during the linear growth phase in plant cell cultures [1].

- Cause: Cytotoxicity of the precursor or its metabolites.

- Solution: Test a range of precursor concentrations and use fed-batch feeding strategies to maintain sub-toxic levels in the culture medium [1].

- Cause: Diversion of precursors into competing metabolic pathways.

Common Problem 2: Inconsistent Production Between Batches

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Uncontrolled variations in culture conditions (pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen).

- Solution: Implement strict bioprocess control and use defined growth media. Monitor and log environmental parameters throughout the fermentation [3].

- Cause: Instability of the precursor in the storage solution or culture medium.

- Solution: Prepare fresh precursor stock solutions for each experiment and verify their stability under culture conditions (e.g., temperature, sterility) [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common precursors used to enhance secondary metabolite production? Precursors are typically intermediate compounds from primary metabolism that feed into secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathways. Common examples include:

- Aromatic amino acids (L-phenylalanine, L-tyrosine): Precursors for phenolic compounds and alkaloids via the shikimic acid pathway [2].

- Mevalonic acid (MVA) or Methylerythritol phosphate (MEP): Key intermediates for terpenoid biosynthesis [2] [5].

- Glycerol: Serves as a carbon source that can enhance the production of various reduced compounds like aromatic compounds, polyols, and lipids in microorganisms [3].

Q2: How does the choice of carbon source, like glycerol, influence precursor availability? The carbon source is fundamental as it fuels both primary metabolism and the provision of precursor molecules. Glycerol is a highly reduced carbon source compared to glucose. Its metabolism generates more NADH and NADPH, which can be advantageous for synthesizing reduced secondary metabolites like lipids and polyols [3]. In some microbes, glycerol also directs more carbon flux toward product formation rather than biomass, potentially boosting secondary metabolite yields during the stationary phase [3].

Q3: What role do signalling molecules play in precursor utilization? Signalling molecules act as key regulators that activate the biosynthetic pathways of secondary metabolites. They can enhance the expression of genes encoding critical enzymes in these pathways, thereby increasing the demand for and channeling of precursors [5]. For example:

- Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA): Can trigger the production of terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics by upregulating pathway genes and transcription factors [5].

- Nitric Oxide (NO) and Hydrogen Sulfide (H₂S): Mitigate oxidative stress and can interact with other signalling networks to promote the synthesis of defensive secondary metabolites [5].

Experimental Protocols for Enhancing Precursor Availability

Objective: To enhance the yield of a target secondary metabolite (e.g., a specific alkaloid or flavonoid) by feeding a biosynthetic precursor.

Materials:

- Sterile plant cell suspension culture

- Standard growth medium

- Filter-sterilized precursor stock solution

- Laminar flow hood, shake flasks, orbital shaker

Methodology:

- Culture Establishment: Initiate plant cell suspension cultures in standard medium and grow under controlled conditions (e.g., 25°C, continuous light or dark, agitation at 110-120 rpm).

- Precursor Addition: At the optimal growth phase (determined empirically, often mid-exponential phase), aseptically add the filter-sterilized precursor solution to the culture medium. A range of concentrations (e.g., 0.1 - 2.0 mM) should be tested.

- Harvesting: Harvest cells by filtration or centrifugation during the stationary phase, typically 3-7 days after precursor feeding.

- Analysis: Extract and analyze the target secondary metabolite using techniques like HPLC or LC-MS. Compare yields to control cultures without precursor feeding.

Objective: To leverage glycerol for improved production of reduced secondary metabolites in yeasts like Komagataella phaffii.

Materials:

- Microbial strain (e.g., Komagataella phaffii)

- Glycerol-based fermentation medium (e.g., with yeast extract, peptone, and glycerol as the sole carbon source)

- Bioreactor or shake flasks with controlled aeration

- pH and dissolved oxygen probes

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow a seed culture of the microbe in a glycerol-containing medium to adapt the cells.

- Fermentation: Inoculate the bioreactor containing the defined glycerol medium. Maintain optimal conditions (e.g., 30°C, pH 5.0, high dissolved oxygen).

- Induction/Production Phase: For engineered strains, induce the expression of secondary metabolite pathways (e.g., by switching carbon source or adding an inducer) once high cell density is achieved.

- Monitoring and Harvest: Monitor glycerol consumption, cell growth, and product formation. Harvest the culture broth at the end of the production phase for downstream processing.

Quantitative Data on Precursor Efficacy

Table 1: Effect of Different Precursors on Secondary Metabolite Production in Various Systems

| Precursor / Carbon Source | Target Secondary Metabolite | Experimental System | Reported Enhancement / Yield | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerol | p-Coumarate, Naringenin |

Komagataella phaffii fermentation [3] | Increased titers compared to glucose | Higher degree of reduction in glycerol favors production of aromatic compounds. |

| Glycerol | Citric Acid | Yarrowia lipolytica fermentation [3] | Outperformed glucose as a substrate | Efficiently channeled into lipid and polyol biosynthesis. |

| Aromatic Amino Acids (e.g., Phenylalanine) | Various Phenolics & Alkaloids | Plant in vitro cultures [2] [1] | Concentration-dependent increase | Direct precursors from the shikimate pathway; feeding bypasses regulatory steps. |

| Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) | Rosmarinic Acid, Terpenoids, Indole Alkaloids | Plant in vitro cultures [5] | Significant increase in production | Elicitor that upregulates transcription factors and genes of biosynthetic pathways. |

Table 2: Key Enzymes in Precursor Generation and Their Roles

| Enzyme | Pathway | Primary Function | Impact on Precursor Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase (PAL) | Phenylpropanoid [2] | Converts phenylalanine to cinnamic acid | Gatekeeper enzyme for phenolic compound biosynthesis; regulated by stress. |

| 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR) | Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway [2] | Catalyzes a key rate-limiting step in mevalonate production | Controls flux into sterols and sesquiterpenes. |

| Chalcone Synthase (CHS) | Flavonoid [2] | Catalyzes the first committed step in flavonoid biosynthesis | Channels p-coumaroyl-CoA from general phenylpropanoid metabolism into specific flavonoids. |

| Chorismate Mutase | Shikimate Pathway [2] | Converts chorismate to prephenate | Regulatory node for the synthesis of phenylalanine, tyrosine, and other aromatics. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Precursor-Based Enhancement of Secondary Metabolites

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Elicitors (e.g., MeJA, Salicylic Acid) | Signalling molecules that trigger plant defence responses and activate secondary metabolite pathways [5]. | Concentration and timing of application are critical to avoid toxicity and maximize yield. |

| Specific Enzyme Inhibitors | Used to block competing metabolic pathways, thereby diverting precursors toward the target secondary metabolite [1]. | Requires detailed knowledge of the metabolic network to avoid detrimental effects on cell viability. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Precursors (e.g., ¹³C-Glucose) | Tracer compounds used to elucidate metabolic fluxes and identify bottlenecks in biosynthetic pathways [3]. | Essential for fundamental research but can be costly for large-scale production. |

| Genetic Engineering Tools (CRISPR, plasmids) | To overexpress limiting enzymes in a target pathway or knock out genes in competing pathways [2] [3]. | Host-dependent; requires established genetic transformation protocols for the organism. |

| Adsorbent Resins (e.g., XAD) | Added in situ to culture medium to adsorb lipophilic secondary metabolites, reducing feedback inhibition and/or cytotoxicity [1]. | Can simplify downstream purification and increase total yield by shifting equilibrium toward production. |

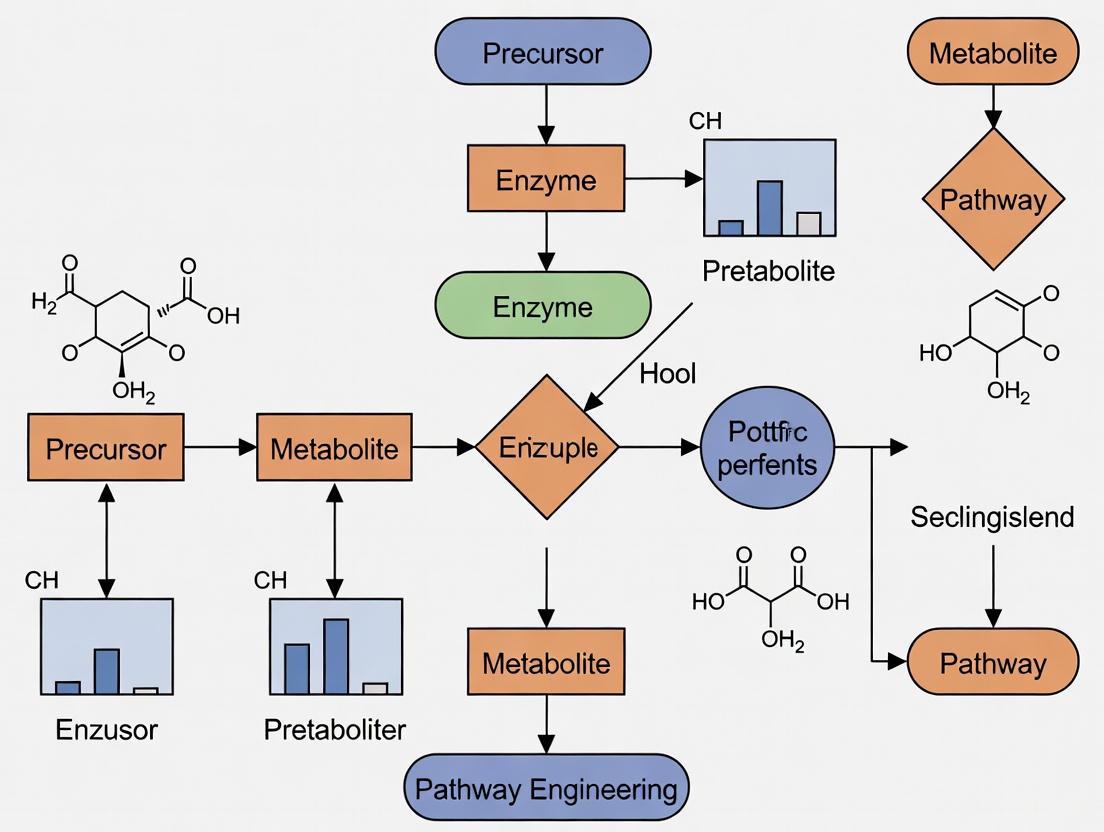

Biosynthetic Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: From Primary Building Blocks to Secondary Metabolites

Diagram 2: Signalling Network Regulating Precursor Utilization

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: My microbial culture for terpenoid production shows poor yield after genetic modifications to the MEP pathway. What could be the cause? A: Imbalanced metabolic flux is a common issue. Overexpressing a single MEP pathway enzyme can lead to the accumulation of toxic intermediates like methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP), causing growth retardation and reduced yield.

- Solution: Implement a balanced modular approach. Co-express multiple genes in the MEP pathway (e.g.,

dxs,idi,ispDF) rather than a single gene. Consider using a tunable promoter system to fine-tune expression levels and avoid toxicity. Monitor cell growth (OD600) and product titers simultaneously.

Q2: I am observing inconsistent shikimate pathway intermediate accumulation in my plant cell cultures. How can I stabilize the flux? A: Inconsistency often stems from feedback inhibition and suboptimal nutrient conditions.

- Solution:

- Address Feedback Inhibition: The key enzyme DAHP synthase is feedback-inhibited by aromatic amino acids. Use a feedback-resistant version (e.g.,

aroG^{fbr}) in your expression system. - Optimize Media: Ensure a sufficient and balanced supply of the primary precursors, Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and Erythrose-4-Phosphate (E4P). This may involve adjusting carbon source feeding (e.g., using a PEP-generating system like pyruvate) and ensuring proper phosphate levels.

- Control Culture Conditions: Maintain strict control over pH, temperature, and light (if phototrophic) to minimize environmental stress-induced flux variations.

- Address Feedback Inhibition: The key enzyme DAHP synthase is feedback-inhibited by aromatic amino acids. Use a feedback-resistant version (e.g.,

Q3: When comparing the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid precursor (IPP/DMAPP) production in a heterologous host, which is generally more efficient? A: The choice is host- and product-dependent. The MVA pathway is often preferred in yeast and other eukaryotes, while the MEP pathway can be more efficient in bacterial systems like E. coli. Key quantitative comparisons are summarized below.

Quantitative Comparison of MVA and MEP Pathways in Model Systems

| Parameter | Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway | Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Hosts | Eukaryotes (e.g., Yeast, Fungi) | Bacteria, Algae, Plastids of Plants |

| Theoretical ATP Cost (per IPP) | 3 ATP | 5 ATP |

| Theoretical Yield (mol IPP / mol Glucose) | Lower (~0.33) | Higher (~0.41) |

| Key Toxic Intermediate | HMG-CoA, Mevalonate-5-P | Methylerythritol Cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP) |

| Advantages in Engineering | Well-established in yeast; easier to compartmentalize. | Higher theoretical carbon yield; avoids acetyl-CoA competition. |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying MEP Pathway Flux using LC-MS/MS

Objective: To measure the intracellular concentrations of MEP pathway intermediates in engineered E. coli.

Cell Cultivation & Quenching:

- Grow engineered E. coli in M9 minimal medium with 2 g/L (^{13})C-Glucose to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ~0.6-0.8).

- Rapidly quench 1 mL of culture by injecting it into 4 mL of 60% methanol (pre-chilled to -40°C). Immediately vortex for 10 seconds.

Metabolite Extraction:

- Centrifuge the quenched sample at 15,000 x g for 5 minutes at -9°C.

- Remove the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in 1 mL of extraction solvent (40:40:20 Acetonitrile:Methanol:Water with 0.1% Formic Acid).

- Sonicate on ice for 5 minutes (10 sec on/off pulses).

- Centrifuge at 15,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer the clear supernatant to a new tube and dry under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Reconstitute the dried extract in 100 µL of water.

- Inject 5 µL onto a HILIC column (e.g., BEH Amide, 2.1 x 100 mm, 1.7 µm) maintained at 40°C.

- Mobile Phase: A) 10 mM Ammonium Acetate in Water, B) 10 mM Ammonium Acetate in 95% Acetonitrile.

- Gradient: 90% B to 50% B over 12 minutes.

- Analyze using a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer in negative MRM mode. Use authentic standards for each MEP intermediate (e.g., DOXP, MEP, MEcPP) to generate calibration curves for quantification.

Pathway and Workflow Diagrams

MEP Pathway to IPP/DMAPP

Shikimate Pathway & Regulation

Metabolic Flux Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| (^{13})C-Labeled Glucose | A stable isotope tracer used in Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) to track carbon atom movement through pathways via LC-MS. |

Feedback-Resistant aroG (aroG(^{fbr})) |

A genetically engineered DAHP synthase enzyme resistant to feedback inhibition by phenylalanine, used to enhance shikimate flux. |

| MEP Pathway Intermediate Standards (DOXP, MEP) | Authentic chemical standards required for developing calibration curves to absolutely quantify intracellular metabolite levels. |

| Tunable Promoter System (e.g., pTet, pBAD) | Allows for precise control of gene expression levels to avoid metabolic burden and toxicity from intermediate accumulation. |

| HILIC Chromatography Column | A hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography column essential for separating highly polar metabolites like MEP pathway intermediates. |

| Quenching Solvent (Cold Methanol) | Rapidly halts all metabolic activity to capture a snapshot of the intracellular metabolome at a specific time point. |

FAQs: Precursor Molecules in Secondary Metabolism

Q1: What are the key precursor molecules for secondary metabolite biosynthesis? The biosynthesis of plant and microbial secondary metabolites primarily relies on a few core precursor molecules derived from central carbon metabolism. The most crucial precursors are:

- Acetyl-CoA and Malonyl-CoA: Serve as the fundamental building blocks for the acetate-malonate pathway, leading to polyketides, fatty acids, and phenolics [6] [7].

- Aromatic Amino Acids (L-Phenylalanine, L-Tyrosine, L-Tryptophan): These are the products of the shikimate pathway and act as precursors for a vast array of nitrogen-containing compounds and phenolics, including alkaloids, flavonoids, and lignin [2] [8] [7].

- Isoprenoid Units (Isopentenyl pyrophosphate - IPP, and Dimethylallyl diphosphate - DMAPP): These five-carbon units are the universal precursors for the mevalonate (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways, which generate all terpenoids and steroids, such as artemisinin, taxol, and carotenoids [2] [5] [7].

Q2: How can I experimentally enhance the flux through a specific precursor pathway to overproduce a target metabolite? A multi-pronged strategy is often most effective:

- Precursor Feeding: Directly supplementing the culture medium with a specific precursor (e.g., shikimic acid for the shikimate pathway, mevalonolactone for the MVA pathway) can bypass regulatory bottlenecks and increase the metabolic flux toward the target compound [8].

- Genetic Engineering of Regulatory Genes: Overexpressing positive pathway-specific regulators (e.g., transcriptional factors like WRKY for artemisinin) or knocking out negative regulators (e.g., some TetR family regulators in Actinomycetes) can powerfully enhance the expression of entire biosynthetic gene clusters [6] [9].

- Elicitation: Using abiotic (e.g., UV light, metal ions) or biotic (e.g., jasmonic acid, yeast extract) elicitors can mimic stress conditions, triggering the plant's or microbe's native defense mechanisms and upregulating secondary metabolite pathways [2] [5] [9].

Q3: What are the common challenges when using precursor feeding in vitro, and how can I troubleshoot them? Common issues and their solutions are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for In Vitro Precursor Feeding

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Low or No Yield Increase | Precursor cytotoxicity; inefficient uptake; feedback inhibition; wrong feeding timing. | Optimize precursor concentration; use esterified or permeable precursor analogs; feed during the stationary production phase; consider split feeding [8]. |

| Production Instability | Somaclonal variation; degradation of precursors in the medium; genetic instability of high-producing cell lines. | Re-select high-producing cell lines regularly; use dark/controlled conditions; test precursor stability in medium; employ organ cultures instead of cell suspensions for better stability [8]. |

| Unexpected By-product Formation | Channeling of the precursor into competing metabolic pathways; low specificity of key enzymes. | Map the metabolic network to identify competing pathways; use enzyme inhibitors for competing routes; co-express pathway-specific regulators to enhance flux toward the desired product [6] [10]. |

Q4: How do environmental factors influence precursor availability and secondary metabolism? Environmental factors significantly modulate the regulatory networks that control precursor pathways.

- Light can repress or induce specific pathways; for example, in Fusarium fujikuroi, light represses fusarin production via white collar proteins but stimulates carotenoid biosynthesis [9].

- Temperature shifts can activate silent gene clusters or optimize pathway efficiency. The optimal temperature for fumonisin biosynthesis in Fusarium verticillioides (20-30°C) is different from that for its growth [9].

- Nutrient Stress, such as nitrogen or phosphate limitation, is a classic strategy to shift metabolism from growth (primary metabolism) to defense (secondary metabolism) by altering the pool of available precursors [2] [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Precursor Feeding for Enhanced Metabolite Production in Plant Cell Cultures

This protocol outlines a standard methodology to boost the yield of high-value secondary metabolites by supplementing the culture medium with biosynthetic precursors [8].

1. Principle: The core idea is to supplement the culture medium with a known intermediate (precursor) from a target biosynthetic pathway. This external supplementation provides additional substrate, helping to overcome natural regulatory bottlenecks and push the metabolic flux toward the overproduction of the desired end product.

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Established plant cell suspension or hairy root culture.

- Standard growth medium (e.g., MS or B5 medium).

- Filter-sterilized precursor stock solution (e.g., phenylalanine, tyrosine, mevalonolactone, shikimic acid).

- Sterile Erlenmeyer flasks.

- Platform shaker.

- Laminar flow hood.

- Vacuum filtration system.

- Solvents for extraction (e.g., methanol, ethanol).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Culture Initiation

- Inoculate the plant cell suspension into fresh liquid medium and grow under standard conditions (e.g., 25°C, continuous dark or light, with agitation) until the late exponential growth phase [8].

- Step 2: Precursor Preparation and Feeding

- Prepare a concentrated, filter-sterilized stock solution of the precursor.

- Aseptically add the precursor to the culture medium to achieve the desired final concentration. A range of concentrations (e.g., 0.1 - 2.0 mM) should be tested in preliminary experiments to identify the optimal level and avoid cytotoxicity [8].

- Include control cultures without precursor supplementation.

- Step 3: Incubation and Harvest

- Return the cultures to the shaker and allow production to continue for a predetermined period (e.g., 24-168 hours).

- Harvest the biomass by vacuum filtration at designated time points to establish a production time-course.

- Step 4: Metabolite Extraction and Analysis

- Lyophilize the harvested biomass.

- Extract metabolites using a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol) via sonication or maceration.

- Concentrate the extracts and analyze the target metabolite using analytical techniques such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or LC-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) [8].

4. Data Analysis:

Compare the yield of the target metabolite in precursor-fed cultures against the control cultures. The yield enhancement can be calculated as: (Yield with precursor - Yield in control) / Yield in control * 100%.

Protocol: Activating Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters via Regulatory Gene Manipulation

This protocol describes a genetic approach to activate silent gene clusters in microorganisms (e.g., Actinomycetes, Fungi) to discover novel secondary metabolites or enhance the production of known ones [6] [9].

1. Principle: Many biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) for secondary metabolites are "silent" under standard laboratory conditions. This method involves genetically manipulating pathway-specific regulatory genes (e.g., by overexpression or deletion) to trigger the expression of the entire silent BGC.

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Microbial strain (e.g., Streptomyces, Fusarium).

- Standard culture media.

- DNA manipulation kits (for PCR, cloning).

- Plasmid vectors for overexpression or gene knockout.

- Host cells for cloning (e.g., E. coli).

- Protoplast transformation or electroporation system.

- Antibiotics for selection.

- LC-MS equipment for metabolite profiling.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Identification of Target

- Use genome mining tools to identify silent BGCs and their associated pathway-specific regulatory genes (e.g., TetR family, SARP family regulators) [6].

- Step 2: Genetic Construct Preparation

- Step 3: Strain Transformation

- Introduce the genetic construct into the wild-type strain via protoplast transformation, conjugation, or electroporation.

- Select for successful transformants using the appropriate antibiotic.

- Step 4: Fermentation and Metabolite Profiling

- Ferment the engineered mutant strain alongside the wild-type strain under identical conditions.

- Extract metabolites from the culture broth and/or mycelium.

- Analyze the metabolic profiles using LC-HRMS to identify newly produced compounds in the mutant strain that are absent in the wild-type [6] [9].

4. Data Analysis: Compare the chromatograms and mass spectra of the mutant and wild-type extracts. New peaks in the mutant extract indicate successfully activated secondary metabolites. Further purification and structural elucidation (e.g., by NMR) are required to identify the novel compounds.

Pathway Diagrams

Core Biosynthetic Pathways for Key Precursors

Experimental Workflow for Enhancing Precursor Availability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Precursor and Pathway Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Shikimic Acid | A key intermediate in the shikimate pathway. Used as a precursor feed to enhance the production of aromatic amino acids and their derivatives [8]. | Overproduction of phenolic compounds, lignins, and alkaloids in plant cell cultures [8]. |

| Mevalonolactone | A hydrolyzed form of mevalonate, the core intermediate of the MVA pathway. Used to supplement the terpenoid backbone biosynthetic pathway [8]. | Enhancing the yield of sesquiterpenes (e.g., artemisinin) and triterpenes in cultured tissues [7]. |

| Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) | A potent signaling molecule and abiotic elicitor. Triggers plant defense responses, upregulating the biosynthesis of various secondary metabolites [5]. | Inducing the production of terpenoid indole alkaloids, rosmarinic acid, and other defense compounds in plant cell and organ cultures [5]. |

| L-Phenylalanine | An aromatic amino acid and direct precursor of the phenylpropanoid pathway. Feeding directly supplies substrate for phenolic compound biosynthesis [2] [8]. | Increasing the yield of flavonoids, anthocyanins, and stilbenes (e.g., resveratrol) in Vitis vinifera cell cultures [8]. |

| Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid (SAHA) | A histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor. Used in epigenetic modulation to activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters in fungi and microbes [6] [9]. | Discovery of novel secondary metabolites from Fusarium and Streptomyces strains by derepressing silent gene clusters [9]. |

| Strong Inducible Promoters (e.g., ermE*) | Genetic tool for controlled gene expression. Used to overexpress pathway-specific positive regulatory genes in heterologous hosts or native strains [6]. | Activating the silent phenazine biosynthetic gene cluster in Streptomyces tendae for antibiotic production [6]. |

In the pursuit of improving precursor availability for secondary metabolite production, understanding transcriptional regulation is paramount. Transcription factors (TFs) are sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins that regulate gene expression by activating or repressing target genes [11]. They form complex gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that act in cooperative or competitive partnerships to precisely control metabolic flux [12]. In secondary metabolism, this regulation occurs at two primary levels: global transcriptional regulators that respond to cellular state and environmental conditions, and pathway-specific transcription factors (PSTFs) that directly control the biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) responsible for producing target metabolites [13].

The hierarchical structure of these regulatory networks allows for flexible control of metabolic pathways. Global TFs often respond to broad cellular indicators like growth state or nutrient availability, while PSTFs provide precise, dedicated control over specific metabolic pathways [14]. This dual regulatory system enables cells to maintain metabolic homeostasis while dynamically allocating precursor resources toward secondary metabolite production when conditions are favorable. For researchers engineering microbial cell factories, manipulating these TF networks offers powerful levers to enhance precursor flux toward valuable secondary metabolites, including pharmaceuticals, antibiotics, and other bio-based compounds [15] [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between global and pathway-specific transcription factors in metabolic regulation?

Global transcription factors coordinate multiple metabolic pathways in response to broad cellular signals and environmental conditions. They regulate numerous genes across the genome, often in response to metabolites that indicate cellular growth state [14]. For example, in E. coli, global TFs like Crp and Cra mediate most specific transcriptional regulation by binding to metabolites such as cyclic AMP and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate [14]. In contrast, pathway-specific transcription factors are dedicated regulators that control individual biosynthetic gene clusters. In fungal systems, PSTFs are frequently located within the BGCs they regulate and specifically activate the expression of genes required for producing particular secondary metabolites [13].

Q2: Why do some pathway-specific transcription factor overexpression experiments fail to activate their target gene clusters?

Several factors can lead to failed PSTF overexpression experiments:

- Insufficient expression levels: The promoter used for overexpression may not generate adequate TF levels to activate the cluster. Switching to a stronger inducible promoter (e.g., the xylP promoter from Penicillium chrysogenum) can significantly improve success rates [15].

- Chromatin repression: Target clusters may be silenced by repressive chromatin structures. Integrating the TF expression construct at a genomic locus not subject to such repression (e.g., the yA locus in Aspergillus nidulans) can overcome this limitation [15].

- Post-translational control: Some TFs require activation through modifications or interaction with co-factors that may be absent under experimental conditions [15] [13].

- Insufficient precursor availability: Even with successful TF overexpression, limited precursor pools can constrain metabolite production, necessitating concurrent engineering of precursor supply pathways [14].

Q3: How can I identify potential pathway-specific transcription factors in a newly discovered biosynthetic gene cluster?

PSTFs can be identified through several approaches:

- Genomic location: PSTF genes are typically located within the BGC they regulate [13].

- DNA-binding domains: They usually contain characteristic DNA-binding domains such as Zn(II)₂Cys₆, C₂H₂ zinc fingers, bZIP, or MYB domains [13].

- Bioinformatic tools: Use cluster annotation tools like SMURF (Secondary Metabolite Unknown Regions Finder) to identify potential regulatory elements within BGCs [15].

- Homology analysis: Compare with known PSTFs from characterized clusters in related organisms [12] [13].

Q4: What strategies can enhance precursor availability for improved secondary metabolite production?

- Dynamic regulation: Implement TF-based biosensors that dynamically regulate precursor pathways in response to metabolite concentrations [16].

- Local flux coordination: Engineer topologically coupled reaction networks in central metabolism to enhance flux toward desired precursors [14].

- Global regulatory manipulation: Modify global TFs that control central carbon metabolism to redirect flux toward secondary metabolite precursors [14].

- Co-culture systems: Utilize microbial consortia where different members specialize in precursor production and final synthesis [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Secondary Metabolite Yields Despite Transcription Factor Overexpression

Problem: Overexpression of a confirmed pathway-specific TF fails to significantly increase target metabolite production.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Table: Troubleshooting Low Metabolite Yields Despite TF Overexpression

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient precursor pool | Measure intracellular precursor concentrations (e.g., acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA); analyze transcript levels of precursor biosynthesis genes | Co-express global regulators of central metabolism; engineer precursor supply pathways; use TF-based biosensors for dynamic precursor regulation [14] |

| Chromatin-mediated repression | Perform chromatin immunoprecipitation for histone modifications; test histone deacetylase inhibitors | Target TF integration to euchromatin regions; use chromatin-modifying enzymes; engineer synthetic gene clusters with minimal epigenetic regulation [15] |

| Inadequate TF expression level | Quantify TF mRNA and protein levels; test different induction conditions | Switch to stronger promoters (e.g., xylP); optimize induction timing and duration; integrate multiple TF copies [15] |

| Missing co-activators or co-factors | Test different growth conditions; perform co-immunoprecipitation for protein partners | Identify and co-express essential co-factors; optimize cultivation media; engineer minimal regulatory circuits [13] |

Experimental Workflow:

- Quantify TF expression at both transcript and protein levels

- Analyze expression of all cluster genes to verify complete activation

- Measure intracellular precursor concentrations

- Test different cultivation conditions and media compositions

- Implement combinatorial engineering addressing multiple limitations simultaneously

Inconsistent Metabolic Pathway Activation Across Experimental Conditions

Problem: Transcription factor-mediated pathway activation shows high variability between replicates or different growth conditions.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Table: Addressing Inconsistent Pathway Activation

| Variability Source | Control Experiments | Stabilization Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous TF expression | Single-cell analysis of TF expression; monitor culture heterogeneity | Use constitutive strong promoters; implement feedback-regulated expression systems; optimize induction parameters [15] |

| Stochastic cluster activation | Time-course analysis of cluster gene expression; single-cell transcriptomics | Pre-condition cells for uniform activation; use synthetic regulatory elements with reduced noise; employ population-based control strategies [14] |

| Environmental fluctuations | Monitor dissolved oxygen, pH, nutrient depletion throughout cultivation | Implement advanced bioreactor control; use defined media with balanced C/N ratio; develop fed-batch protocols with precise nutrient feeding [16] |

| Genetic instability | Serial passage experiments; verify genetic constructs stability | Use stable genomic integration; avoid repetitive sequences; implement selection pressure maintenance [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Systematic Overexpression of Secondary Metabolism Transcription Factors

Purpose: To activate cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters for secondary metabolite discovery and production enhancement.

Materials and Reagents:

- Strong inducible promoter (e.g., xylP from Penicillium chrysogenum)

- Construction vectors for targeted genomic integration

- Appropriate transformation reagents and equipment

- Induction agent (e.g., xylose for xylP promoter)

- Analytical standards for target metabolites

- LC-MS system for metabolite profiling

Procedure:

- TF Identification and Selection:

Expression Construct Design:

- Clone selected TF genes under control of a strong inducible promoter

- Design constructs for integration into specific genomic loci (e.g., yA locus) to avoid chromatin-mediated repression [15]

Strain Generation:

- Transform host organism with expression constructs

- Verify integration by PCR and Southern blotting

- Confirm TF inducibility by Western blotting [15]

Metabolite Production Analysis:

- Grow wild-type and TF-overexpression strains under standard conditions

- Induce TF expression at appropriate growth phase (e.g., add 1% xylose at 48h for A. nidulans) [15]

- Culture for additional period to allow metabolite accumulation (e.g., 3-5 days)

- Extract metabolites from both cells and culture broth

- Analyze extracts using LC-MS with comparative metabolomics approaches [15]

Validation and Scale-up:

- Confirm cluster activation by RT-qPCR of biosynthetic genes

- Isulate and structurally elucidate novel compounds

- Optimize production conditions in bioreactor systems

Construction and Application of Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors

Purpose: To develop genetic circuits that dynamically regulate metabolic pathways in response to precursor availability.

Materials and Reagents:

- Allosteric transcription factors responsive to target metabolites

- Modular plasmid systems for biosensor construction

- Fluorescent reporter genes (e.g., GFP, RFP)

- Flow cytometer or microplate reader for signal detection

- Microfluidic systems for high-throughput screening (optional)

Procedure:

- Biosensor Design:

- Select TF with appropriate ligand specificity or engineer specificity through directed evolution [16]

- Clone TF gene under constitutive promoter

- Place reporter gene under control of TF-regulated promoter

- Include metabolic engineering targets under same regulatory control for dynamic pathway optimization [16]

Biosensor Validation:

- Transform biosensor construct into host strain

- Test response to gradient of target metabolite or precursor

- Determine dynamic range, sensitivity, and specificity

- Optimize ribosome binding sites and promoter strength for desired response characteristics [16]

Application for Strain Engineering:

- Use biosensor-response to screen mutant libraries for enhanced precursor production

- Implement dynamic regulation of pathway genes to balance metabolic flux

- Monitor population heterogeneity and implement strategies to reduce noise [16]

- Combine multiple biosensors for coordinated regulation of complex pathways

Pathway Diagrams and Regulatory Networks

Hierarchical Transcription Factor Network for Metabolic Pathway Control

Transcription Factor-Based Biosensor Mechanism

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Transcription Factor Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inducible Promoters | xylP (from P. chrysogenum), alcA, PcbC* | Controlled TF overexpression; strong, tunable expression | xylP provides stronger induction than alcA; consider promoter compatibility with host [15] |

| DNA-Binding Domain References | Zn(II)₂Cys₆, C₂H2 zinc fingers, bZIP, bHLH, Homeobox | TF classification and functional prediction | Different DBDs have distinct DNA recognition specificities; affects target gene regulation [12] [13] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | SMURF, JASPAR, TRANSFAC, CisBP | BGC identification; TF binding site prediction | SMURF identifies secondary metabolite BGCs; JASPAR/TRANSFAC provide TF binding motifs [15] [11] |

| Analytical Standards | Sterigmatocystin, monodictyphenone, asperfuranone | Metabolite identification and quantification | Use as references for LC-MS analysis; confirm cluster activation and product identity [15] [13] |

| Chromatin Modifiers | Histone deacetylase inhibitors, DNA methyltransferase inhibitors | Overcome epigenetic silencing of BGCs | Can activate cryptic clusters but may have pleiotropic effects; use with appropriate controls [15] |

Table: Quantitative Analysis of Transcription Factor Types in Characterized Fungal BGCs

| Organism | Total Characterized BGCs | BGCs with PSTFs | Most Common PSTF DNA-Binding Domains | Average PSTFs per Regulated Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus nidulans | 28 | 12 (42.9%) | Zn(II)₂Cys₆, C₂H2, Myb-like | 1.33 [13] |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 18 | 10 (55.6%) | Zn(II)₂Cys₆, C₂H2, bZIP | 1.20 [13] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The integration of transcription factor engineering with systems biology approaches is revolutionizing metabolic engineering for enhanced precursor flux. Local flux coordination - the natural tendency of topologically coupled metabolic reactions to be co-regulated - provides engineering targets for enhancing specific precursor pools [14]. By identifying sparse linear basis (SLB) vectors in metabolic networks, researchers can pinpoint reaction groups that function as coordinated units, enabling more precise metabolic engineering strategies [14].

Future advancements will likely focus on multi-dimensional regulation combining global and pathway-specific TFs with synthetic regulatory circuits. The development of TF-based biosensors enables dynamic regulation of metabolic pathways, allowing microbial cell factories to autonomously adjust flux in response to precursor availability [16]. Emerging approaches include:

- Directed evolution of TF specificity to create novel biosensors for target metabolites

- Artificial intelligence-driven prediction of TF-DNA binding specificities

- Cross-species TF engineering to transfer regulatory circuits between organisms

- Multi-input biosensor networks for coordinated regulation of complex pathways

These strategies will ultimately enable more predictable and efficient engineering of microbial systems for enhanced production of valuable secondary metabolites, addressing critical needs in pharmaceutical development, industrial biotechnology, and sustainable manufacturing.

The efficient production of secondary metabolites—complex chemical compounds with widespread applications in pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and flavoring industries—is fundamentally constrained by precursor availability. These metabolites, which are not essential for the immediate survival of the producing organism but often possess valuable bioactive properties, are biosynthesized from simpler primary metabolites through dedicated metabolic pathways. The yield of any target secondary metabolite is therefore intrinsically linked to the flux of precursor molecules through its biosynthetic route. Understanding and optimizing this connection is critical for overcoming the natural low-yield limitations that hamper the commercial viability of many valuable compounds, from antimicrobial agents to anticancer drugs [17] [18].

This technical support center provides a foundational framework and practical troubleshooting guidance for researchers aiming to enhance secondary metabolite production by strategically managing precursor supply. The content is framed within the context of a broader thesis on improving precursor availability, addressing both theoretical principles and common experimental pitfalls encountered during optimization workflows.

Theoretical Foundations: Biosynthetic Pathways and Precursor Origins

Secondary metabolites are synthesized from core primary metabolic pathways. The table below summarizes the major biosynthetic routes and their key precursors.

Table 1: Major Biosynthetic Pathways for Secondary Metabolites

| Biosynthetic Pathway | Key Precursor Molecules | Example Secondary Metabolites |

|---|---|---|

| Shikimate Pathway [17] | Phosphoenolpyruvate, D-erythrose-4-phosphate | Aromatic amino acids (L-phenylalanine, L-tyrosine), gallic acid, shikimic acid, vanillin (via biotransformation) [17] |

| Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway [17] [18] | Acetyl-Coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) | Terpenoids, steroids, lovastatin [17] |

| Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway [17] [18] | Pyruvate, Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate | Terpenoids (in most bacteria and plant plastids) [17] |

| Malonate/Acetate Pathway [18] | Acetyl-Coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) | Phenolic compounds, flavonoids [18] |

| Alkaloid Biosynthesis [18] | Various Amino Acids (e.g., tyrosine, tryptophan) | Harringtonine, homoharringtonine, caffeine, morphine [18] |

The relationship between primary metabolism and the activation of secondary metabolite synthesis is often regulated by elicitors. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of how elicitors trigger the cellular signaling that enhances precursor flow and final yield.

FAQs: Core Principles for Researchers

Q1: Why is precursor supply often a limiting factor in secondary metabolite yield? Secondary metabolites are typically synthesized after the growth phase from primary metabolites like acetyl-CoA and amino acids [17]. The cell's metabolic machinery is primarily geared towards growth and survival, so the flux of carbon and nitrogen toward these secondary pathways is naturally limited. Without intervention, the pools of key precursors can be insufficient to drive high-yield production of the target compound.

Q2: What are the main strategies for enhancing precursor availability? The two primary strategies are (1) internal pathway engineering, which involves optimizing fermentation conditions (media, pH, temperature) to maximize the cell's inherent production of precursors [19] [20], and (2) external precursor feeding, which involves supplying the culture with compounds that are direct or indirect precursors to the target metabolite [17]. A powerful adjunct to these is elicitation, using biotic or abiotic agents to trigger the plant's or microbe's own defense pathways, which often involve the upregulation of secondary metabolite synthesis [18].

Q3: Can I simply add high concentrations of a precursor to the fermentation broth? Not always. The direct addition of precursors can be ineffective or even counterproductive. Some precursors may be toxic to the producing cells at high concentrations, while others might not be efficiently taken up or might be metabolized via different pathways. Strategies like gradual feeding or using volatile precursors that can be slowly supplied via the oxygen stream have been developed to overcome these issues [17].

Q4: How do I identify which precursor to target for my metabolite of interest? The first step is to conduct a thorough literature review to identify the known or putative biosynthetic pathway of your target metabolite. This will reveal the immediate biochemical precursors and the core metabolic pathways from which they are derived (e.g., shikimate, mevalonate) [17] [18]. Genomic and metabolomic analyses can further help in mapping the complete pathway and identifying potential bottlenecks [20] [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting Precursor Feeding and Yield Optimization

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Yield Despite Precursor Feeding | Precursor toxicity; inefficient cellular uptake; degradation of precursor in the medium; metabolic flux diverted to other pathways. | - Test a range of precursor concentrations [17].- Use protected or prodrug forms of the precursor.- Consider fed-batch or continuous feeding to maintain low, non-toxic levels.- Use inhibitors to block competing pathways. |

| High Cell Growth but Low Metabolite Production | Decoupling of growth (trophophase) and production (idiophase); insufficient expression of biosynthetic genes. | - Use elicitors (e.g., Salicylic Acid, Methyl Jasmonate) to trigger secondary metabolism [18].- Optimize culture timing--add precursors/elicitors at the transition to stationary phase.- Manipulate C/N ratio in the media to stress cells and induce production [19]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Batch Cultures | Uncontrolled variations in culture conditions; poor quality or unstable precursors; inconsistent timing of precursor addition. | - Strictly standardize inoculation protocols and media preparation.- Use fresh, properly stored precursor stocks.- Precisely time the addition of precursors based on growth phase (OD) rather than chronological time.- Use statistical design of experiments (DoE) for optimization [19]. |

| Difficulty in Isolating/Purifying the Target Metabolite | The enhanced precursor flux led to a more complex mixture of related metabolites or side-products. | - Optimize extraction solvents and methods (e.g., liquid-liquid extraction, flash chromatography) [20].- Scale up the purification process to handle increased complexity.- Use analytical techniques (HPLC, MS) to guide purification protocol development [20]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Systematic Optimization of Physicochemical Parameters

This is a foundational protocol to establish a baseline for enhancing both biomass and intrinsic precursor synthesis before specific precursor feeding is initiated [19] [20].

Initial Screening (One-Factor-at-a-Time):

- Media: Test different standard culture media (e.g., LB, ISP2) to identify the one that maximizes growth and initial metabolite yield [19] [20].

- Incubation Time: Determine the optimal incubation period by tracking growth and metabolite production over time. The point where metabolite production peaks is often at the end of the exponential or start of the stationary phase [19].

- pH & Temperature: Screen a physiologically relevant range (e.g., pH 5-8, temperature 25-37°C) to identify initial optimal conditions [20].

Advanced Optimization (Statistical Design):

- Once key factors are identified (e.g., temperature, pH, agitation), employ a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design like Box-Behnken to model their interactive effects [19].

- The model will predict the precise combination of factors that simultaneously maximizes biomass and metabolite yield. Note that the optimal conditions for growth and production may differ slightly [19].

Elicitor-Mediated Enhancement of Precursor Flux

This protocol uses signaling molecules to trigger the organism's native defense responses, which often involve upregulating entire biosynthetic pathways, thereby naturally enhancing precursor availability [18].

- Elicitor Selection: Choose appropriate elicitors. Common and effective chemical elicitors include Salicylic Acid (SA) and Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) [18].

- Stock Solution Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of the elicitors. MeJA is often dissolved in ethanol, and SA in water or a mild solvent, and then filter-sterilized.

- Treatment:

- Grow the microbial culture or plant cell suspension under pre-optimized conditions from Protocol 5.1.

- At the transition to the stationary phase (or a predetermined optimal time), add the elicitor to the culture medium.

- Include a control treatment that receives an equal volume of the solvent used for the elicitor.

- Dosage and Duration Testing: Perform a dose-response experiment. Test a range of concentrations (e.g., SA from 50-200 µM) and various exposure times (e.g., 24-96 hours) to find the optimal treatment that maximizes yield without significantly compromising viability [18].

- Harvest and Analysis: Harvest cells and/or medium at the end of the treatment period. Extract metabolites and quantify the yield of your target secondary metabolite using analytical methods like HPLC or LC-MS [20].

The following workflow diagram integrates these two protocols into a coherent experimental strategy for systematic yield enhancement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Metabolic Optimization Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Elicitors | Activate plant defense signaling pathways, leading to upregulation of genes in secondary metabolite biosynthesis [18]. | Salicylic Acid (SA), Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA), Nitric Oxide donors, Sodium Fluoride (often used synergistically with MeJA) [18]. |

| Precursor Molecules | Directly feed and augment the pool of building blocks for target metabolic pathways [17]. | Amino acids (e.g., Phenylalanine, Tyrosine), Organic acids, Sugars. For vanillin production, ferulic acid is a direct precursor [17]. |

| Optimized Culture Media | Provide the foundational nutrients and optimal physicochemical environment for growth and production. | ISP2 Medium for Streptomyces [19], Expi293 Expression Medium for mammalian protein production [22]. Often requires customization of C/N sources and salts. |

| Analytical Standards | Enable identification and precise quantification of target metabolites in complex mixtures. | Certified reference standards for your target compound (e.g., harringtonine, lovastatin) are essential for calibration in HPLC and MS analysis [20]. |

| Extraction & Purification Kits | Isolate and concentrate metabolites from culture broth or cellular biomass for downstream analysis. | Solvents like ethyl acetate for liquid-liquid extraction [20]; silica gel for flash column chromatography [20]; specialized kits for nucleic acid or protein purification if working with pathway enzymes [23]. |

Practical Strategies for Precursor Supply: Feeding, Engineering, and Elicitation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental purpose of using precursor feeding in secondary metabolite production? Precursor feeding is a strategy used to increase the accumulation of valuable plant or microbial secondary metabolites, such as terpenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids. It works by supplying key building blocks (precursors) to the biosynthetic pathways, thereby enhancing the metabolic flux towards the desired compound and overcoming natural regulatory bottlenecks [1] [17].

Q2: What are the main challenges associated with direct precursor supplementation? The primary challenges include:

- Cytotoxicity: High concentrations of some precursors can be toxic to the cells or tissue culture, inhibiting growth and metabolite production [1].

- Uptake Efficiency: The biological system may not efficiently absorb the precursor from the medium [1].

- Production Stability: Ensuring consistent and stable production over time can be difficult [1].

- Foaming: In submerged microbial fermentation, direct addition can cause excessive foaming, increasing contamination risk [17].

Q3: How do volatile precursor delivery systems address these challenges? Volatile precursor delivery systems take advantage of the gas phase (e.g., oxygen supply) for the gradual introduction of volatile precursors into the solid-state fermentation system. This controlled, slow release helps to avoid the toxicity problems often encountered with a single, high-concentration dose of direct supplementation, as it prevents the precursor from accumulating to harmful levels at any one time [17].

Q4: What factors must be optimized for a successful precursor feeding experiment? Successful optimization depends on several interconnected factors [1]:

- Precursor type and concentration

- The specific plant species or microbial strain

- Culture conditions (e.g., medium composition, light, temperature)

- Timing of precursor addition during the growth cycle

Q5: In which fermentation system is volatile precursor delivery most applicable? This strategy is particularly reviewed for improving the production of secondary metabolites in Solid-State Fermentation (SSF). SSF uses a solid material (like agro-industrial residues) with low water content, which is well-suited for gaseous interactions [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Yield of Target Metabolite Despite Precursor Feeding

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| No increase in product concentration. | Precursor cannot enter the cell or is not effectively transported to the synthesis site. | ✓ Test different precursor analogs for better uptake [1].✓ Optimize the culture medium's pH and ion concentration to facilitate transport. |

| Cell growth inhibition or death after precursor addition. | Cytotoxicity from excessive precursor concentration [1]. | ✓ Conduct a dose-response curve to find the optimal, non-toxic concentration.✓ Switch to a volatile delivery system for a gradual, sustained supply [17]. |

| Metabolite production peaks and then declines rapidly. | Instability of the produced metabolite or feedback inhibition. | ✓ Optimize the harvesting timepoint.✓ Consider in-situ extraction techniques to remove the product as it is formed. |

| Inconsistent results between batches. | Unoptimized culture conditions (aeration, pH, temperature) [1]. | ✓ Strictly control and monitor all physical culture parameters.✓ Standardize the physiological state (growth phase) at which the precursor is added. |

Problem 2: Challenges Specific to Solid-State Fermentation (SSF)

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient biotransformation of precursor. | Poor distribution of the precursor within the solid matrix. | ✓ Improve mixing strategies or ensure the volatile precursor carrier gas is evenly distributed [17].✓ Moisten the solid substrate with a solution containing the precursor as part of the liquid inoculum [17]. |

| Low overall productivity. | Raw material used as solid substrate lacks essential precursor molecules. | ✓ Supplement the solid substrate with a precursor-rich material [17].✓ Select an agro-industrial residue that naturally contains the required precursor (e.g., using ferulic acid-rich bagasse for biovanillin production) [17]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Direct Precursor Feeding in Plant Tissue Culture

This protocol outlines the methodology for enhancing secondary metabolite production by adding precursors directly to the in vitro culture medium [1].

Key Reagents:

- Sterile precursor stock solution

- Plant tissue culture medium (e.g., MS medium)

- Callus or suspension cell cultures

Detailed Methodology:

- Precursor Preparation: Prepare a concentrated, sterile stock solution of the chosen precursor. Use an appropriate solvent (e.g., water, DMSO, ethanol) and sterilize by filtration (0.22 µm).

- Culture Initiation: Establish stable and rapidly growing callus or cell suspension cultures in a suitable medium.

- Precursor Addition: At the optimal growth phase (typically late exponential phase), aseptically add the sterile precursor stock to the culture medium to achieve the desired final concentration. This is determined from prior dose-response experiments.

- Incubation and Monitoring: Continue incubating the cultures under standard conditions (specific temperature, photoperiod, agitation). Monitor cell viability and growth regularly.

- Harvesting: Harvest the cultures at the predetermined optimal time point, which may be several hours or days after precursor feeding.

- Extraction and Analysis: Extract the target secondary metabolite from the biomass using an appropriate solvent (e.g., methanol, ethyl acetate). Quantify the yield using analytical techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

Protocol 2: Supplying Volatile Precursors in Solid-State Fermentation

This protocol describes a strategy for the gradual supply of volatile precursors in SSF to avoid cytotoxicity [17].

Key Reagents:

- Solid substrate (e.g., agro-industrial residue like wheat bran, sugarcane bagasse)

- Microbial inoculum (e.g., fungus or bacteria)

- Volatile precursor compound

Detailed Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: The solid substrate is selected and prepared (e.g., dried, ground, and moistened with a nutrient solution to an optimal moisture level). It is then sterilized by autoclaving.

- Inoculation: The sterile solid substrate is inoculated with a mature microbial culture under aseptic conditions.

- Volatile Precursor Delivery:

- Method A (Headspace Diffusion): Place a small, open container with the volatile precursor liquid inside the sealed fermentation bioreactor, allowing it to evaporate slowly into the headspace.

- Method B (Carrier Gas): Sparge a sterile, moistened air or oxygen stream through a vessel containing the volatile precursor, then direct this carrier gas into the SSF bioreactor. This allows for more controlled delivery.

- Fermentation Process: Incubate the SSF system at the optimal temperature for the microorganism. The volatile precursor is continuously and gradually supplied via the gas phase.

- Process Monitoring: Monitor environmental parameters like temperature and gas composition.

- Termination and Extraction: After the fermentation period, terminate the process. The entire fermented solid mass is processed with a suitable solvent to extract the target secondary metabolites for subsequent analysis.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Precursor Integration in Secondary Metabolism

Experimental Workflow for Precursor Feeding

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Precursor Feeding | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Compounds | Building blocks supplied to enhance metabolic flux toward the target compound. | Specific to pathway (e.g., phenylalanine for phenolics; mevalonic acid for terpenoids) [1] [2]. |

| Solid Substrates | Support for microbial growth and precursor delivery in SSF; can be a source of natural precursors. | Agro-industrial residues (e.g., sugarcane bagasse, wheat bran) [17]. |

| Elicitors | Signal molecules that stimulate plant defense responses and activate secondary metabolite pathways. | Jasmonic acid, methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid [2] [24]. |

| Elicitors | Signal molecules that stimulate plant defense responses and activate secondary metabolite pathways. | Jasmonic acid, methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid [2] [24]. |

| Inert Supports | Used in SSF to provide physical structure without interfering chemically, allowing precise control of nutrients. | Polyurethane foam, amberlite resin, vermiculite [17]. |

| Analytical Standards | Essential for accurate identification and quantification of secondary metabolites during analysis. | Certified reference standards for the target compound (e.g., vanillin, paclitaxel) [25] [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges in Glycerol-Based Bioprocesses

This section addresses frequent issues researchers encounter when using glycerol as a carbon source for enhancing metabolic precursor pools.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Glycerol Utilization Challenges

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions | Key Precursors Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Glycerol Assimilation | Non-optimized metabolic pathways; impurities in crude glycerol [26]. | Overexpress GUT1 (glycerol kinase) gene [26]; use fed-batch strategies to control metabolic flux [27]. |

Acetyl-CoA, Malonyl-CoA, Propionyl-CoA |

| Low Yield of Target Metabolites | Imbalanced acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA ratio; insufficient reducing power [28]. | Co-feed acetate to balance acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA ratio [28]; use metabolic models to predict NADH surplus [27]. | Odd-Chain Fatty Acids (OCFA), Polyhydroxyalkanoates |

| Toxic By-product Accumulation | Media components or metabolic by-products inhibiting growth. | Use robust chassis like Pseudomonas putida KT2440 [29]; implement in situ product removal strategies. | Various secondary metabolites |

| Inconsistent Fermentation Performance | Uncontrolled substrate feeding leading to redox imbalance. | Implement RQ (Respiratory Quotient) control between 4-5 to regulate glucose/glycerol feed [27]. | Ethanol, Glycerol (by-product) |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is glycerol considered a superior carbon source for precursor synthesis compared to glucose?

Glycerol is more reduced (degree of reduction, γ = 4.7) than glucose (γ = 4.0), meaning it carries more electrons per carbon atom [29]. This higher reduction state facilitates the synthesis of reduced biochemicals, potentially offering higher yields for products like lipids and polyhydroxyalkanoates [29]. Furthermore, it is a major, low-cost by-product of biodiesel production, making it a sustainable and economical feedstock [29] [26].

FAQ 2: How can we engineer microbial strains to more efficiently utilize crude glycerol?

A key strategy is to manipulate the glycerol assimilation pathways. For the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica, overexpression of the GUT1 gene, which codes for glycerol kinase, results in rapid glycerol assimilation [26]. This enzyme phosphorylates glycerol to glycerol-3-phosphate, funneling it directly into central metabolism. Using robust chassis strains like Pseudomonas putida KT2440, which has a high innate tolerance to physicochemical stresses and impurities in crude glycerol, is also a highly effective approach [29].

FAQ 3: What is the critical link between precursor pools and the production of odd-chain fatty acids (OCFAs)?

The synthesis of OCFAs requires a specific precursor pool of propionyl-CoA (a three-carbon unit) and acetyl-CoA (a two-carbon unit). Research in Yarrowia lipolytica has shown that simply providing propionate is not enough. Overexpressing a propionyl-CoA transferase gene (pct) from Ralstonia eutropha was necessary to efficiently activate propionate into propionyl-CoA, increasing OCFA accumulation by 3.8-fold [28]. Furthermore, balancing the ratio of acetyl-CoA to propionyl-CoA, often by co-feeding acetate, is crucial for high-level production [28].

FAQ 4: Which process control parameter can directly help minimize glycerol formation as a by-product in yeast fermentations?

The Respiratory Quotient (RQ), defined as the ratio of CO2 produced to O2 consumed, is a key indicator. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentations, glycerol is produced to re-oxidize surplus NADH. By controlling the substrate feeding rate to maintain an RQ value between 4 and 5, the formation of excess NADH is minimized, thereby successfully reducing glycerol production [27].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Enhancing OCFA Production inYarrowia lipolytica

This protocol details the methodology for engineering precursor pools to boost Odd-Chain Fatty Acid (OCFA) production, based on the work of [28].

Objective: To enhance the pool of propionyl-CoA and β-ketovaleryl-CoA precursors in Yarrowia lipolytica for increased OCFA synthesis.

Materials:

- Strain: Yarrowia lipolytica strain.

- Plasmids: For overexpression of pct (propionyl-CoA transferase) from Ralstonia eutropha and bktB (β-ketothiolase).

- Media: Defined minimal media with glycerol as the primary carbon source.

- Supplements: Sodium propionate and sodium acetate.

- Bioreactor: Fed-batch system with control for pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen.

Procedure:

- Strain Engineering:

- Construct a recombinant Y. lipolytica strain by overexpressing the pct gene.

- In a subsequent step, co-express the bktB gene in the same strain to enhance the β-ketovaleryl-CoA pool.

Fermentation Setup:

- Inoculate the engineered strain into a bioreactor containing media with pure or crude glycerol.

- Supplement the media with sodium propionate (e.g., 2-5 g/L) as a direct precursor for propionyl-CoA.

- Co-feed sodium acetate (e.g., 1-3 g/L) to maintain a critical balance between acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA pools [28].

Process Optimization:

- Conduct the fermentation in a fed-batch mode.

- Optimize the Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C/N) ratio to trigger lipid accumulation. A high C/N ratio is typically used.

- Monitor cell growth, substrate consumption, and OCFA production over time.

Expected Outcome: Following this integrated approach of strain and bioprocess engineering can lead to OCFA titers up to 1.87 g/L, representing over 60% of total lipids [28].

Visualizing Metabolic Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the key metabolic pathways and logical workflows involved in carbon source engineering.

Glycerol Assimilation and Precursor Formation in Yarrowia lipolytica

Integrated Workflow for Precursor Pool Engineering

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Precursor Engineering Experiments

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Crude Glycerol | Low-cost, renewable feedstock from biodiesel production; higher reduction state than sugars [29] [26]. | Primary carbon source for fermentative production of lipids and organic acids. |

| Propionate Salts | Direct precursor for propionyl-CoA, essential for synthesizing odd-chain fatty acids (OCFAs) and derivatives [28]. | Supplement in media for OCFA production in Yarrowia lipolytica. |

| Zirfon Diaphragm | Inexpensive and robust porous separator for electrolysis; enhances durability in carbon conversion systems [30]. | Used in electrolyzers for converting waste CO/CO₂, creating sustainable C1 carbon sources. |

| Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) | Signalling molecule that acts as an elicitor, enhancing the production of plant secondary metabolites [5] [31]. | Added to plant cell cultures to boost synthesis of terpenes, phenolics, and alkaloids. |

| Gas Diffusion Electrodes | Enable membraneless electrochemical processes, reducing cost and maintenance in carbon capture and conversion [32]. | Key component in systems for regenerating amines in carbon capture, providing a carbon source. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Yield of Target Secondary Metabolite Despite Precursor Gene Overexpression

Problem: Researchers often overexpress a key enzyme in a biosynthetic pathway, expecting increased metabolite yield, but observe no significant improvement.

Question: I overexpressed the gene encoding a key rate-limiting enzyme, but the final product titer did not increase. What could be the reason?

Solution:

- Diagnosis: The problem likely stems from a bottleneck elsewhere in the metabolic network. Overexpression of a single gene may cause metabolic imbalance, leading to the accumulation of intermediate compounds or the diversion of flux through competing pathways [33].

- Recommended Actions:

- Analyze Intermediate Metabolites: Use metabolomic profiling (e.g., via LC-MS) to check for the accumulation of pathway intermediates. This can identify the next actual bottleneck [34].

- Engineer Multiple Steps Simultaneously: Implement a multivariate modular approach. Co-overexpress several genes in the same pathway to balance flux. For example, in terpenoid engineering, overexpress not only DXS (1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase) but also other genes in the MEP pathway [34].

- Downregulate Competitive Pathways: Identify and silence genes in pathways that consume your desired precursor. For instance, when engineering flavonoid production, RNAi-mediated suppression of the competing anthocyanin pathway in Fagopyrum tataricum can redirect flux [35].

- Employ Systems Biology Tools: Use genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to simulate the entire metabolic network and predict which gene combinations, when engineered, will maximize flux toward the target metabolite without causing cellular stress [36].

Issue 2: Failure of Heterologous Expression of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)

Problem: A BGC from a native producer (e.g., an actinomycete or plant) is successfully cloned into a heterologous host like E. coli or S. cerevisiae, but the secondary metabolite is not produced.

Question: I have successfully cloned a full gene cluster into a heterologous host, but no product is detected. What are the key areas to investigate?

Solution:

- Diagnosis: Heterologous hosts often lack the specific regulatory machinery, precursor pools, or post-translational modification systems found in native producers [34] [37].

- Recommended Actions:

- Verify Precursor Supply: Ensure your heterologous host can generate sufficient precursor molecules. You may need to engineer the host's central metabolism. For example, in E. coli, enhancing the malonyl-CoA pool is critical for producing polyketides [34].

- Check Codon Usage and Promoters: Re-code the BGC using codons optimized for your host. Use synthetic biology parts (promoters, RBSs) that are well-characterized and functional in the chosen host. In cyanobacteria, this is a particularly critical step due to a lack of standardized parts [36].

- Assess Enzyme Compatibility: Ensure that all tailoring enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450s) in the cluster are functional in the host and can access their required cofactors. Co-expression of partner proteins may be necessary [37].

- Confirm Cluster Integrity and Regulation: Ensure the entire cluster is intact and that a strong, constitutive promoter is driving expression of the core biosynthetic genes, bypassing the need for the native, and often complex, regulatory system [34].

Issue 3: Host Viability and Toxicity of Pathway Intermediates

Problem: Engineered strains grow poorly or display genetic instability, especially when a heterologous pathway is introduced or a native pathway is strongly overexpressed.

Question: My engineered strain shows poor growth or plasmid loss, particularly after induction of the target pathway. How can I resolve this?

Solution:

- Diagnosis: The metabolic burden of expressing heterologous genes or the toxicity of accumulated intermediates can inhibit cell growth and lead to genetic instability [34].

- Recommended Actions:

- Use Tunable Expression Systems: Employ inducible promoters (e.g., tetracycline-inducible systems in Streptomyces) to separate the growth phase from the production phase, minimizing metabolic burden [37].

- Compartmentalization and Transport: Localize biosynthetic pathways to specific cellular compartments (e.g., plant vacuoles or microbial membrane systems) to isolate toxic intermediates from the cytosol. Alternatively, engineer transporter genes to export the toxic compound [35] [33].

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): Subject the slow-growing engineered strain to serial passaging under selective conditions to evolve mutations that restore robust growth while maintaining production capability [34].

- Genome Integration over Plasmids: Stably integrate the biosynthetic pathway into the host chromosome to avoid issues related to plasmid replication and segregation [36].

Issue 4: Inconsistent or Low Production in Scale-Up

Problem: A strain performs excellently in small-scale lab cultures (e.g., shake flasks) but fails to maintain high productivity during bioreactor scale-up.

Question: My strain produces the target compound in flasks, but the titer drops significantly in a bioreactor. What factors should I consider?

Solution:

- Diagnosis: Inconsistencies are often due to heterogeneous environmental conditions in large-scale bioreactors (e.g., gradients in nutrient concentration, dissolved oxygen, or pH) that are not present in well-mixed flasks [34].

- Recommended Actions:

- Optimize Feeding Strategies: Shift from simple batch cultures to fed-batch or continuous processes with controlled carbon and nitrogen feeding to avoid catabolite repression and maintain a metabolically active state [34].

- Fine-Tune Bioprocess Parameters: Closely monitor and control dissolved oxygen, as many secondary metabolite pathways (e.g., those in actinomycetes) are induced under oxygen limitation. Also, optimize aeration, agitation, and light conditions for photosynthetic hosts like cyanobacteria [36].

- Employ Chemical Elicitors: Add sub-lethal concentrations of antibiotics, heavy metals, or quorum-sensing molecules to the medium. These "signals" can mimic natural stress conditions and trigger the expression of silent BGCs [34] [37].

- Model-Based Scale-Up: Use systems biology tools to integrate multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, fluxomics) generated at different scales to build predictive models that can guide a more rational scale-up process [34] [36].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary strategic differences between engineering native producers versus heterologous hosts for secondary metabolite production?

The choice involves a trade-off between native capability and engineering tractability.

| Consideration | Native Producer (e.g., Streptomyces, Plants) | Heterologous Host (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Advantage | Contains native pathways, regulators, and precursors; often produces the metabolite naturally [34]. | Superior genetic tools, faster growth, often easier to scale in industrial fermentation [34]. |

| Main Challenge | Complex genetics, poor genetic tools, unknown regulatory networks, and potential for silent clusters [37]. | May lack necessary precursors, cofactors, or post-translational modifications; can be toxic to the host [34]. |

| Key Engineering Focus | Awakening silent BGCs, manipulating global regulators, and overcoming rate-limiting steps within the native context [37]. | Reconstituting the entire pathway, supplying precursors via central metabolism, and ensuring functional enzyme expression [34]. |

FAQ 2: Beyond simple gene overexpression, what are advanced strategies for manipulating metabolic flux toward my target precursor?

Advanced strategies move beyond single-gene edits to systems-level engineering.

- Multivariate Modular Engineering: This involves co-expressing multiple genes in a pathway as a single "module" to optimize the flux through a specific section of the pathway. For example, the entire MEP pathway for terpenoid precursors can be treated as one module [34].