Quantifying Confidence in Metabolic Flux Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Bayesian Methods

Accurate quantification of confidence intervals is crucial for interpreting metabolic flux estimates derived from stable isotope labeling experiments, yet the nonlinear nature of these systems presents significant statistical challenges.

Quantifying Confidence in Metabolic Flux Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Bayesian Methods

Abstract

Accurate quantification of confidence intervals is crucial for interpreting metabolic flux estimates derived from stable isotope labeling experiments, yet the nonlinear nature of these systems presents significant statistical challenges. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists, exploring the fundamental importance of flux uncertainty analysis and contrasting traditional linearized methods with advanced approaches like Bayesian inference and Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling. We detail practical methodologies for confidence interval estimation, identify common pitfalls in experimental design and data analysis, and present robust frameworks for model and data validation. By synthesizing foundational principles with cutting-edge techniques, this guide aims to empower more reliable flux quantification in metabolic engineering and drug development.

Why Flux Confidence Intervals Matter: Foundations of Metabolic Flux Uncertainty

The Critical Role of Metabolic Fluxes in Understanding Cell Physiology and Disease

Metabolic fluxes, defined as the rates at which metabolites traverse biochemical pathways within a cell, provide a dynamic and quantitative measure of cellular physiology that transcends static molecular inventories [1] [2]. These fluxes represent the functional integration of genetic regulation, protein expression, and metabolic demands, offering unparalleled insight into how cells allocate resources for growth, energy production, and biosynthesis [3]. In fields ranging from metabolic engineering to human disease pathology, the ability to accurately measure and interpret metabolic fluxes has become indispensable for elucidating underlying mechanisms and identifying therapeutic interventions [4] [5].

The quantification of metabolic fluxes presents unique challenges, as these rates cannot be measured directly but must be inferred through sophisticated computational models integrating experimental data [2] [5]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the predominant methodologies for metabolic flux determination, with a particular emphasis on their approaches to quantifying confidence intervals and uncertainty—a critical yet often overlooked aspect of flux analysis [1] [2]. By examining experimental protocols, statistical frameworks, and emerging technologies, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to select appropriate flux analysis methods and accurately interpret their results in the context of cell physiology and disease.

Methodologies for Metabolic Flux Determination: A Comparative Analysis

Core Principles and Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Major Metabolic Flux Analysis Techniques

| Method | Core Principle | Data Inputs | Uncertainty Quantification | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) | Uses 13C-labeled substrates to trace carbon fate through metabolic networks [6] | Extracellular fluxes, 13C labeling patterns from MS/NMR [1] [6] | Confidence intervals from nonlinear regression [1] | Central carbon metabolism in controlled systems [2] [6] |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Constrains genome-scale models with exchange fluxes; assumes optimal growth [2] | Genome-scale metabolic models, exchange rates [2] | Not inherently provided; requires additional sampling [2] | Genome-scale predictions, microbial engineering [2] |

| Isotope-Assisted Metabolic Flux Analysis (iMFA) | Integrates isotope labeling data with comprehensive metabolic models [5] | 13C labeling, extracellular fluxes, multi-omics data [5] | Bayesian inference, MCMC sampling [2] | Human diseases, mammalian systems [5] |

| Bayesian Flux Analysis (BayFlux) | Uses Bayesian inference to sample flux probability distributions [2] | 13C labeling, exchange fluxes, prior knowledge [2] | Full posterior probability distributions [2] | Uncertainty-sensitive applications, knockout predictions [2] |

Statistical Approaches to Confidence Estimation

The nonlinear nature of metabolic models complicates uncertainty quantification, and different methods employ distinct statistical paradigms:

Frequentist Approaches (Traditional 13C-MFA): Traditional 13C-MFA relies on maximum likelihood estimation and local approximation of confidence intervals using sensitivity analysis [1]. This approach linearizes the system around the optimal flux values, which can produce inaccurate uncertainty bounds due to inherent nonlinearities in isotopic systems [1]. The residual sum of squares (SSR) is used to evaluate model fit, with confidence intervals typically calculated through Monte Carlo simulations [6].

Bayesian Methods (BayFlux): Bayesian approaches represent a paradigm shift in flux uncertainty quantification by treating fluxes as probability distributions rather than fixed values with simple confidence intervals [2]. These methods use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to identify the full distribution of fluxes compatible with experimental data, providing a more complete picture of uncertainty, particularly in non-Gaussian situations where multiple distinct flux regions fit the data equally well [2].

Emerging Quantum Algorithms: Recent research has demonstrated that quantum interior-point methods can solve flux balance analysis problems, potentially offering computational advantages for very large-scale metabolic models [7]. These approaches use quantum singular value transformation for matrix inversion and incorporate null-space projection to improve numerical stability [7]. While currently limited to simulations, this methodology represents a promising frontier for uncertainty quantification in massive metabolic networks.

Table 2: Comparison of Statistical Frameworks for Flux Confidence Estimation

| Framework | Philosophical Basis | Uncertainty Output | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequentist / MLE | A true flux value exists; estimate it from data [1] | Confidence intervals based on linearization [1] | Computationally efficient, well-established [1] | May misrepresent uncertainty in nonlinear systems [1] |

| Bayesian Inference | Fluxes have probability distributions [2] | Full posterior distributions [2] | Handles multi-modal solutions, incorporates prior knowledge [2] | Computationally intensive for very large models [2] |

| Monte Carlo Sampling | Repeated sampling reveals flux variability [6] | Confidence intervals from solution distributions [6] | Intuitive, model-agnostic [6] | May fail with inconsistent data [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Metabolic Flux Determination

Standard 13C-MFA Workflow

The five fundamental steps of 13C-MFA provide a structured approach to flux quantification [6]:

Experimental Design: Selection of appropriate 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose) based on the research question and metabolic pathways of interest. The choice of tracer significantly impacts flux resolution, with dual-labeled substrates generally providing superior accuracy compared to single-labeled variants [6].

Tracer Experiment: Culturing cells or organisms with the labeled substrate under metabolic steady-state conditions. The system must reach isotopic steady state, typically requiring incubation for at least five residence times to ensure complete labeling of metabolic pools [6].

Isotopic Labeling Measurement: Extraction and analysis of intracellular metabolites using techniques such as GC-MS, LC-MS/MS, or NMR to determine isotopic labeling patterns [6]. GC-MS is most commonly employed for its high precision and sensitivity [6].

Flux Estimation: Computational determination of fluxes that best fit the experimental data using nonlinear regression. Software tools such as INCA, Metran, and OpenFLUX implement the Elementary Metabolic Units (EMU) framework to decompose complex metabolic networks into tractable units for analysis [4] [6].

Statistical Analysis and Validation: Assessment of model fit through evaluation of the residual sum of squares and calculation of confidence intervals for estimated fluxes [6]. This step is crucial for determining the reliability and physiological significance of the results [1].

Application in Disease Research: Glioblastoma Case Study

Recent research exemplifies the application of metabolic flux analysis in understanding human disease. A 2025 study investigated metabolic adaptations in patient-derived glioblastoma cells under ketogenic conditions using [2H7]glucose tracing [4]. The experimental protocol involved:

- Culturing three primary human glioblastoma cell lines (CA7, CA3, L2) in both standard and ketogenic media [4].

- Administering [2H7]glucose tracer to track glucose utilization through central carbon metabolism [4].

- Measuring intracellular deuterium enrichment and metabolite pool sizes using NMR and mass spectrometry [4].

- Implementing metabolic flux analysis using Isotopomer Network Compartment Analysis (INCA) software to quantify pathway fluxes [4].

- Correlating flux distributions with cell viability to assess therapeutic potential [4].

This study revealed three distinct metabolic phenotypes among the glioblastoma cell lines, which correlated with differential cell viability in ketogenic conditions. Notably, these phenotypic differences were apparent in the flux analysis but not in metabolite pool size measurements, highlighting the unique insights provided by flux analysis [4].

Visualization of Central Carbon Metabolism and Key Fluxes

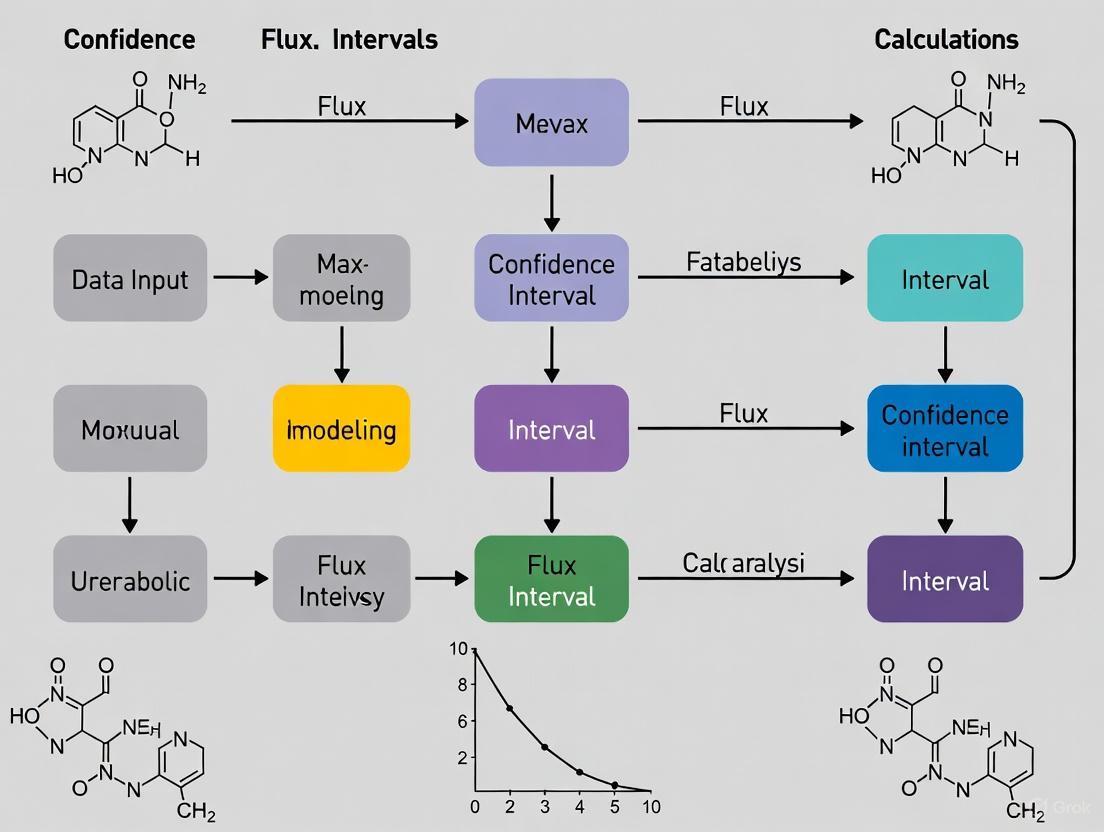

Understanding metabolic flux analysis requires familiarity with the core pathways of central carbon metabolism. The following diagram illustrates the primary metabolic routes tracked in 13C-MFA studies, particularly in the context of the glioblastoma research discussed above [4]:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Flux Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracing carbon fate through metabolic networks [6] | [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, 13C-glutamine [4] [6] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Measuring isotopic enrichment in metabolites [6] | GC-MS, LC-MS/MS for precise isotopologue distribution [6] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Alternative method for isotopic labeling detection [6] | Particularly useful for positional isotopomer analysis [6] |

| Flux Analysis Software | Computational flux estimation from labeling data [4] [6] | INCA, OpenFLUX, Metran, BayFlux [2] [4] [6] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Contextualizing fluxes within complete metabolic networks [2] | Recon (human), iJO1366 (E. coli), consensus yeast models [2] |

| Cell Culture Media | Maintaining metabolic steady-state during tracing [4] | Custom formulations for specific nutritional conditions [4] |

The field of metabolic flux analysis continues to evolve along several exciting frontiers. Bayesian approaches are increasingly being applied to genome-scale models, providing more comprehensive uncertainty quantification [2]. The integration of flux analysis with multi-omics datasets represents another promising direction, offering more complete pictures of cellular regulation [2] [5]. Perhaps most intriguingly, quantum computing algorithms have demonstrated potential for solving complex flux balance problems, potentially overcoming computational bottlenecks that currently limit analysis of massive metabolic networks such as those found in microbial communities or human metabolism [7].

As these methodological advances mature, key challenges remain. Efficient data loading onto quantum processors, management of condition numbers in large matrices, and development of standardized protocols for uncertainty reporting will be critical areas for continued development [7] [2]. Furthermore, as demonstrated by the glioblastoma study, translational applications require careful consideration of metabolic heterogeneity and context-specific flux distributions [4].

In conclusion, metabolic flux analysis provides an indispensable window into cellular physiology that static measurements cannot offer. The critical evaluation of confidence intervals and uncertainty quantification methods presented here underscores the importance of rigorous statistical frameworks for drawing meaningful biological conclusions. As these methodologies continue to advance and become more accessible, they hold tremendous promise for unlocking new insights into disease mechanisms and guiding therapeutic interventions across a wide spectrum of human pathologies.

Metabolic flux analysis (MFA) has evolved into a fundamental methodology for quantifying physiology in fields ranging from metabolic engineering to the analysis of human metabolic diseases [8]. At the core of modern flux determination lies the sophisticated use of stable isotopes and isotopomer measurements, which enable researchers to quantify metabolic reaction rates that cannot be directly observed [9]. These fluxes provide a powerful, integrated description of cellular phenotype by capturing the net interplay of the transcriptome, proteome, regulome, and metabolome [9]. The precision with which metabolic fluxes can be estimated from stable isotope measurements has become a critical metric in systems biology, requiring advanced statistical methods to determine confidence intervals and validate flux estimates [10] [8]. This guide examines the foundational technologies and methodologies that underpin flux determination, comparing experimental approaches and their applications in resolving complex metabolic networks.

Comparative Analysis of Flux Determination Methodologies

Table 1: Core Methodologies in Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Method | Isotope Tracers | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Not required | Assumed | Not applicable | Genome-scale metabolic modeling; Predictive simulations [11] |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) | Not required | Assumed | Not applicable | Central carbon metabolism studies; Constraint-based modeling [11] |

| 13C-MFA | 13C-labeled substrates | Required | Required | High-resolution flux maps; Metabolic engineering [11] [12] |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) | 13C-labeled substrates | Required | Not required | Systems with slow isotope equilibration; Plant metabolism [11] |

| Dynamic MFA (DMFA) | Optional | Not required | Not required | Transient culture conditions; Bioprocess optimization [11] |

| COMPLETE-MFA | Multiple labeled substrates | Required | Required | Maximum flux resolution; Mammalian cell systems [11] |

Table 2: Analytical Techniques for Isotopomer Measurement

| Technique | Isotopomer Information | Sensitivity | Throughput | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Positional enrichment; Limited isotopomers | Moderate | Low | Non-destructive; Provides atomic position information [11] [12] |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Mass isotopologues; No positional data | High | High | High sensitivity; Compatible with separation techniques [10] [11] |

| Gas Chromatography-MS (GC-MS) | Mass isotopomers of molecular ions and fragments | High | High | High information from fragmentation patterns [12] |

| Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS) | Mass isotopomers with minimal fragmentation | High | High | Direct measurement of molecular ions [12] |

| Tandem MS (MS/MS) | Positional enrichment for specific fragments | High | Moderate | Provides some positional information [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Flux Determination

Isotope Labeling Experiment Design

The foundation of reliable flux determination begins with carefully designed isotope labeling experiments. Prior to introducing isotopic tracers, cells are pre-cultured until they reach metabolic steady state, where metabolic fluxes remain constant over time [11]. The experimental design requires replacement of the natural abundance medium with a precisely formulated labeled substrate. For the widely used 13C-MFA approach, the system must then reach isotopic steady state, where isotopes are fully incorporated and static—a process that may require 4 hours to a full day for mammalian cell systems [11]. Optimal label design depends on four key factors: (1) the network structure, (2) the true flux values, (3) the available label measurements, and (4) commercially available substrates [13]. Parallel labeling experiments, where multiple tracer experiments are conducted under identical conditions with different labeling patterns, offer significant advantages for resolving specific fluxes with high precision and validating biochemical network models [14].

Figure 1: Workflow for Stable Isotope-Based Flux Determination. The process encompasses experimental design, cultivation, analytical measurement, and computational analysis phases, with key operational steps at each stage.

Sample Preparation and Metabolite Extraction

Sample preparation for flux analysis requires meticulous attention to maintain metabolic steady state throughout the process. The most common stable isotopes used in fluxomics are 2H, 13C, 15N, and 18O, with 13C being predominantly utilized due to its universal presence in bioorganic molecules and relatively high abundance compared to 12C [11]. Cells are rapidly quenched during mid-exponential growth phase using cold methanol or other quenching solutions to immediately halt metabolic activity [11]. Intracellular metabolites are then extracted using appropriate solvent systems—typically methanol/water or chloroform/methanol mixtures—selected based on the polarity of target metabolites and compatibility with subsequent analytical techniques. The extraction process must efficiently disrupt cells while preventing degradation or conversion of metabolites, preserving the in vivo labeling patterns for accurate analysis [11].

Data Processing and Computational Modeling

The transformation of raw isotopomer measurements into metabolic fluxes requires sophisticated computational approaches. Isotope-assisted metabolic flux analysis (iMFA) mathematically formulates the relationship between mass isotopomer distributions and metabolic fluxes into a set of mass balance equations [9]. The computational process begins with an initial guess for all metabolic fluxes in the system, which are used to generate simulated mass distribution vectors (MDVs) for each metabolite. The model then iteratively optimizes flux estimates to minimize the difference between simulated and experimental MDVs [9]. For underdetermined systems where complete flux resolution is not possible, probabilistic approaches such as the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm can generate probability distributions of metabolic flux levels consistent with observed labeling patterns [15]. The recent integration of state-of-the-art optimization tools with algebraic modeling systems has provided greater robustness in flux estimation [9].

Quantitative Framework for Flux Confidence Estimation

Table 3: Statistical Framework for Flux Confidence Estimation

| Statistical Approach | Application in Flux Analysis | Key Advantages | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Squared (χ²) Test | Validation of flux estimates against isotopic measurements | Tests statistical consistency of entire flux solution [10] | Requires sufficient measurement redundancy |

| Confidence Interval Determination | Quantification of flux precision using sensitivity analysis | Provides accurate flux uncertainty approximation [8] | Accounts for inherent system nonlinearities |

| Local Standard Deviation Estimates | Approximation of flux uncertainty from curvature of objective function | Computational efficiency | May be inappropriate due to system nonlinearities [8] |

| Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm | Probability distribution of fluxes using Markov Chain Monte Carlo | Handles underdetermined systems; Provides complete solution space [15] | Computationally intensive for large networks |

| Effect Size Analysis (Cohen's d) | Quantitative assessment of metabolic reprogramming between states | Enables detailed read-out of metabolic changes [15] | Requires careful experimental design with replicates |

The determination of confidence intervals for metabolic fluxes estimated from stable isotope measurements represents a critical advancement in flux analysis [8]. Without confidence information, interpreting flux results and expanding the physiological significance of flux studies remains challenging. Analytical expressions of flux sensitivities with respect to isotope measurements and measurement errors enable determination of local statistical properties of fluxes and the relative importance of measurements [8]. The development of efficient algorithms to determine accurate flux confidence intervals has demonstrated that confidence intervals obtained with such methods closely approximate true flux uncertainty, in contrast to confidence intervals approximated from local estimates of standard deviations, which are inappropriate due to inherent system nonlinearities [8].

Figure 2: Computational Workflow for Flux Estimation with Statistical Validation. The iterative process integrates experimental data with metabolic models, incorporating statistical validation through chi-squared testing and confidence interval determination.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Isotope-Assisted Flux Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Flux Analysis | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1-13C]glucose; [U-13C]glucose; [1,2-13C]glucose | Carbon source with specific labeling patterns for tracing metabolic pathways | Labeling position tailored to target pathways; Commercial availability [13] [14] |

| 15N-Labeled Compounds | [15N]ammonium salts; [15N]amino acids | Nitrogen source for tracing nitrogen metabolism | Compatibility with experimental system; Cost considerations [11] |

| Extraction Solvents | Cold methanol; Chloromethane/water mixtures; Acetonitrile | Metabolite quenching and extraction | Extraction efficiency for target metabolites; Compatibility with analytical platforms [11] |

| Derivatization Reagents | MSTFA (N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide); MBTSTFA | Chemical modification for GC-MS analysis | Volatility enhancement; Stability of derivatives; MS fragmentation patterns [11] |

| Internal Standards | 13C-labeled amino acids; Uniformly labeled cell extracts | Quantification normalization; Recovery monitoring | Non-interference with native metabolites; Different labeling pattern from tracers [15] |

| Cell Culture Media | Defined chemical composition; Dialyzed serum | Precise control of nutrient concentrations | Elimination of unlabeled nutrient carryover; Support for metabolic steady state [9] [11] |

Application Case Study: Lysine Biosynthesis Network Resolution

A seminal application of stable isotopes for flux determination demonstrated the systematic quantification of the lysine biosynthesis flux network in Corynebacterium glutamicum under glucose limitation in continuous culture [10]. Researchers introduced 50% [1-13C]glucose as the labeled substrate and deployed a bioreaction network analysis methodology for flux determination from mass isotopomer measurements of biomass hydrolysates. This approach thoroughly addressed critical issues of measurement accuracy, flux observability, and data reconciliation [10]. The analysis enabled resolution of anaplerotic activity using only one labeled substrate, determination of the range of most exchange fluxes, and validation of flux estimates through satisfaction of redundancies. Key findings included the determination that phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and synthase did not carry flux under the experimental conditions, and identification of a high futile cycle between oxaloacetate and pyruvate, indicating highly active in vivo oxaloacetate decarboxylase [10]. The flux estimates successfully passed the chi-squared statistical test, representing an important advancement as prior flux analyses of extensive metabolic networks from isotopic measurements had failed criteria of statistical consistency [10].

Stable isotopes and isotopomer measurements constitute the methodological foundation for modern metabolic flux determination, enabling quantitative analysis of cellular metabolic phenotypes with increasing precision and scope. The integration of sophisticated analytical techniques with advanced computational frameworks has transformed flux analysis from a qualitative tool for pathway elucidation to a rigorous quantitative methodology capable of generating statistically validated flux maps. The critical importance of determining confidence intervals for estimated fluxes has emerged as an essential component in flux studies, allowing researchers to distinguish meaningful metabolic differences from experimental uncertainty. As isotopic tracing methodologies continue to evolve—embracing more complex parallel labeling designs, dynamic flux analysis, and integration with other omics technologies—the resolution and reliability of flux determination will further advance, expanding applications in basic science, metabolic engineering, and biomedical research.

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a gold-standard technique for quantifying intracellular reaction rates in living cells, with critical applications in metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and cancer biology [16] [17]. The method leverages 13C-labeled substrates, mass spectrometry, and computational modeling to infer metabolic fluxes, providing an integrated functional phenotype of the cellular metabolic network [18] [19]. However, the transition from raw isotopic labeling data to reliable flux maps is fraught with statistical challenges. Traditional statistical methods, particularly the χ2-test of goodness-of-fit, often struggle with the nonlinear, high-dimensional, and constrained nature of 13C-MFA models [20] [21]. This article explores the inherent limitations of these traditional approaches and compares them with modern validation and model selection techniques that are reshaping best practices in the field.

The Pitfalls of Traditional Statistics in 13C-MFA

The application of traditional statistics in 13C-MFA primarily fails due to several interconnected challenges rooted in the complexity of metabolic systems and the models used to represent them.

Overreliance on the χ2-Test with Uncertain Errors: The χ2-test is the most widely used method for evaluating the goodness-of-fit of an MFA model to the experimental mass isotopomer distribution (MID) data [20] [21]. However, its correctness is highly sensitive to accurate knowledge of the measurement errors (σ). In practice, these errors are often estimated from sample standard deviations of biological replicates, which can be very low (e.g., 0.001–0.01) but may not capture all sources of experimental bias, such as instrument inaccuracies or deviations from the assumed metabolic steady-state [21]. When the magnitude of these errors is mis-specified, the χ2-test can lead to the selection of an incorrect model structure, resulting in either overfitting (an overly complex model that fits the noise in the data) or underfitting (an overly simple model that misses key metabolic features) [21]. This dependency makes the test unreliable for robust model selection.

The Model Selection Conundrum: Model development in 13C-MFA is an iterative process where researchers test different network architectures (e.g., including or excluding specific reactions or compartments) [20]. When this process is guided solely by the χ2-test on a single dataset, it can lead to a form of data dredging. The first model that passes the χ2-test might be selected, even if other, more plausible models exist [21]. Furthermore, determining the correct number of identifiable parameters (degrees of freedom) for the χ2 distribution is difficult for the nonlinear models used in 13C-MFA, further complicating the test's application [21].

Limitations of Stoichiometric Models: Methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) rely on stoichiometric models and linear optimization, predicting fluxes by assuming the cell optimizes an objective function (e.g., growth rate). Validating these predictions is challenging, and the choice of the objective function is a critical, yet often unvalidated, assumption that significantly influences the resulting flux map [20].

Computational Intractability and Identifiability: The elementary metabolite unit (EMU) framework has dramatically reduced the computational burden of simulating isotopic labeling [16] [19]. Despite this, the parameter estimation problem in 13C-MFA remains nonlinear. This can lead to issues of practical identifiability, where different combinations of flux values can produce similarly good fits to the experimental data, making it difficult to pinpoint a unique, accurate flux solution [20].

Comparison of Statistical and Validation Approaches in Metabolic Flux Analysis

The table below summarizes the core limitations of traditional statistical methods and contrasts them with emerging solutions for model validation and selection in 13C-MFA.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional vs. Improved Statistical Methods in 13C-MFA

| Feature | Traditional Approach (χ2-test based) | Modern / Improved Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Iterative model fitting and selection using a χ2-test of goodness-of-fit on a single dataset [20] [21]. | Validation-based model selection using independent data not used for model training [21]. |

| Key Assumption | Measurement errors are accurately known and follow a normal distribution [21]. | A model that generalizes well to new data is more likely to be correct, reducing the need for perfect error estimates [21]. |

| Primary Weakness | Highly sensitive to mis-specified measurement errors; can select different model structures based on believed error magnitude [21]. | Requires additional experimental effort to generate a high-quality validation dataset [21]. |

| Impact on Flux Estimates | Can lead to overfitting or underfitting, producing flux estimates with high bias or variance and poor predictive power [21]. | Promotes the selection of more robust models, leading to flux estimates that are more accurate and reliable [21]. |

| Treatment of Uncertainty | Flux uncertainty is typically quantified after a single model is selected, which can be misleading if the model is wrong [20]. | Bayesian techniques and Monte Carlo analysis can be used to characterize uncertainty in both parameters and model structure [20] [19]. |

| Role in FBA | Often limited to comparing FBA predictions against a flux map derived from 13C-MFA for a specific condition [20]. | Systematic evaluation of alternative objective functions to identify those that result in the best agreement with experimental data across conditions [20]. |

Best Practice Experimental Protocols for Robust 13C-MFA

To overcome the limitations of traditional statistics, researchers should adopt rigorous experimental and computational workflows. The following protocols are essential for generating high-quality, statistically defensible flux maps.

Protocol for Parallel Labeling Experiments

Parallel labeling experiments involve feeding cells multiple different 13C-labeled tracers (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine) in separate but identical cultures and simultaneously fitting the combined MID data to a single model [20].

- Objective: To significantly improve the precision and identifiability of flux estimates by providing more comprehensive labeling constraints [20].

- Procedure:

- Design Tracer Mixtures: Select tracers that are metabolized through different pathways to illuminate specific flux splits (e.g., oxidative vs. non-oxidative pentose phosphate pathway).

- Cell Cultivation: Cultivate cells in parallel bioreactors, each with a unique 13C-labeled substrate as the sole carbon source. Ensure cultures reach metabolic and isotopic steady state [18] [17].

- Sampling and Quenching: Rapidly collect and quench cell samples to preserve metabolic activity.

- Metabolite Extraction: Use a cold methanol-water solution to extract intracellular metabolites.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze the extracts using Liquid Chromatography coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to measure the MID of key intermediate metabolites [22] [18].

- Data Integration: The MIDs from all parallel tracer experiments are incorporated as a single dataset during the model-fitting procedure in 13C-MFA software [20].

Protocol for Validation-Based Model Selection

This method uses a separate, independent validation experiment to objectively choose the best model structure.

- Objective: To select a model structure that generalizes well to new data, avoiding overfitting and underfitting [21].

- Procedure:

- Training Experiment: Conduct a 13C-tracer experiment (e.g., using a mixture of 80% [1-13C] and 20% [U-13C] glucose) to generate a training dataset [16].

- Model Fitting: Fit a set of candidate model structures (e.g., with and without a specific reaction like pyruvate carboxylase) to the training data.

- Independent Validation Experiment: Perform a separate tracer experiment using a different labeled substrate (e.g., [U-13C]glutamine) to generate a validation dataset. This experiment must be distinct from the training data to properly test model novelty [21].

- Model Selection: Evaluate the predictive power of each candidate model by simulating the validation experiment and comparing the predictions to the actual validation data. The model with the best predictive performance is selected [21].

- Key Consideration: The validation experiment should be sufficiently different from the training experiment to be informative but not so different that no model can predict it well [21].

Visualizing the Shift from Traditional to Robust 13C-MFA Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the critical differences between the traditional, problematic workflow and the improved, validation-driven workflow for 13C-MFA.

Essential Research Reagent and Software Solutions

Successful and statistically robust 13C-MFA relies on a suite of specialized reagents and software tools. The table below details key components of the "Scientist's Toolkit."

Table 2: Key Research Reagent and Software Solutions for 13C-MFA

| Category | Item | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C]Glucose | Illuminates pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) flux and glycolysis [17]. |

| [U-13C]Glucose | Uniformly labeled tracer for comprehensive analysis of central carbon metabolism [18]. | |

| [U-13C]Glutamine | Essential for tracing glutamine metabolism, anaplerosis, and reductive TCA cycle flux in cancer cells [17]. | |

| 13C-Glucose Mixtures (e.g., 80% [1-13C] + 20% [U-13C]) | A common, well-studied mixture designed to provide high 13C abundance in various metabolites for accurate flux determination [16]. | |

| Analytical Tools | GC-MS or LC-MS | Mass spectrometry platforms for measuring Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) in metabolites. GC-MS often used for proteinogenic amino acids; LC-MS for unstable or low-abundance intermediates [16] [18]. |

| Software & Algorithms | INCA, Metran | Widely used software packages that implement the EMU framework for efficient 13C-MFA flux estimation [16] [17]. |

| OpenFLUX, 13CFLUX2 | Other established software options for stationary state 13C-MFA [16]. | |

| FluxPyt | A Python-based open-source software for 13C-MFA, increasing accessibility and customizability [19]. | |

| geoRge, HiResTEC | Software tools recommended for untargeted quantification of 13C enrichment from high-resolution LC-MS data [22]. | |

| Statistical Tools | Monte Carlo Analysis | A method used in tools like FluxPyt to estimate standard deviations and confidence intervals for calculated fluxes [19]. |

| Validation-Based Model Selection | A framework for using independent data to select the most robust model structure, as implemented in recent research [21]. |

The nonlinear and complex nature of metabolic networks makes 13C-MFA inherently resistant to the application of traditional statistical tests like the χ2-test for model selection. Reliance on these methods can lead to flux maps that are statistically acceptable but biologically misleading. The path forward requires a shift in practice: embracing parallel labeling experiments to improve data quality, adopting validation-based model selection to ensure robustness, and leveraging modern open-source software that facilitates rigorous uncertainty analysis. By moving beyond traditional statistics, researchers can quantify confidence intervals for metabolic flux estimates with greater reliability, ultimately accelerating progress in metabolic engineering and biomedical research.

Metabolic fluxes, the in vivo rates of biochemical reactions, represent a foundational functional phenotype in systems biology and metabolic engineering. For years, the primary output of metabolic flux analysis has been point estimates—single numerical values representing the most likely flux through each reaction. However, a paradigm shift is underway, moving beyond these point predictions toward probabilistic flux distributions that quantify uncertainty. This shift is critical because ignoring flux uncertainty can lead to flawed physiological interpretations, misguided metabolic engineering strategies, and incorrect biological conclusions.

The quantification of confidence intervals for metabolic flux estimates has emerged as a crucial research frontier. As Theorell and colleagues note, "Bayesian statistical methods are gaining popularity in the field of life sciences, but the use of 13C-MFA is still dominated by conventional best-fit approaches" [23]. This transition from deterministic to probabilistic frameworks represents a fundamental advancement in how researchers model, interpret, and trust metabolic fluxes.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of methodologies for flux uncertainty quantification, detailing their experimental protocols, performance characteristics, and implications for physiological interpretation in biomedical and biotechnological contexts.

Methodological Landscape for Flux Uncertainty Quantification

Comparative Analysis of Uncertainty Quantification Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Major Flux Uncertainty Quantification Methodologies

| Method | Core Principle | Uncertainty Output | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequentist 13C-MFA [1] [20] | Nonlinear parameter estimation with confidence intervals from local sensitivity | Single confidence interval per flux | Established methodology; Direct interpretation | May misrepresent uncertainty in nonlinear systems [1] |

| Bayesian 13C-MFA [23] [2] | Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling of posterior flux distribution | Full probability distribution for each flux | Captures multi-modal distributions; Natural uncertainty propagation | Computationally intensive; Steeper learning curve |

| BayFlux [2] | Bayesian inference with genome-scale models | Probability distributions for all fluxes in genome-scale model | Genome-scale coverage; Improved knockout predictions | Scaling challenges for very large models |

| Conformalized Quantile Regression [24] | Machine learning with calibrated prediction intervals | Valid prediction intervals for flux estimates | Well-calibrated uncertainty; Handles complex patterns | Requires substantial training data |

| Flux Balance Analysis with Ensemble Biomass [25] | Multiple biomass compositions to capture natural variation | Range of feasible fluxes across ensemble | Accounts for compositional uncertainty; Flexible constraints | Limited to FBA framework |

Performance Comparison Across Methods

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Uncertainty Quantification Approaches

| Method | Computational Demand | Model Scale | Experimental Data Requirements | Uncertainty Realism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequentist 13C-MFA [1] | Moderate | Core metabolism (50-100 reactions) | Labeling data + extracellular fluxes | Underestimates in nonlinear regions [1] |

| Bayesian 13C-MFA [23] [2] | High | Core metabolism | Labeling data + extracellular fluxes | High (captures complex distributions) |

| BayFlux [2] | Very High | Genome-scale (1000+ reactions) | Labeling data + extracellular fluxes | High with genome-scale constraint |

| Ensemble FBA [25] | Low-Moderate | Genome-scale | Extracellular fluxes only | Moderate (limited by FBA assumptions) |

Consequences of Ignoring Flux Uncertainty

Physiological Interpretation Errors

Ignoring flux uncertainty can severely compromise physiological interpretation in multiple ways. First, it may lead to overconfidence in flux differences between conditions. For instance, a 20% difference in flux between wild-type and mutant strains might appear significant when only considering point estimates, but proper uncertainty quantification could reveal this difference to be within the margin of error [1] [20].

Second, without uncertainty estimates, researchers cannot properly evaluate the strength of evidence for or against particular metabolic pathways or regulatory mechanisms. Anton-Sanchez and colleagues demonstrated that uncertainty quantification successfully generated valid prediction intervals to identify high-risk contamination events, with Conformalized Quantile Regression emerging as the most reliable method [24]. In physiological studies, this translates to more robust identification of truly altered metabolic states.

Third, missing uncertainty information hampers model selection and validation. As noted in a comprehensive review of model validation practices, "Despite advances in other areas of the statistical evaluation of metabolic models, such as the quantification of flux estimate uncertainty, validation and model selection methods have been underappreciated and underexplored" [20]. Without proper uncertainty quantification, researchers may select overly complex models that appear to fit data well but have poor predictive power.

Impact on Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

In applied contexts, ignoring flux uncertainty carries practical consequences. In metabolic engineering, overconfidence in flux estimates may lead to suboptimal genetic engineering strategies. For example, knocking out enzymes based on apparently high fluxes through competing pathways might prove ineffective if those flux estimates have high uncertainty [2].

The BayFlux method developers demonstrated this by creating P-13C MOMA and P-13C ROOM, novel methods that improve knockout predictions by quantifying prediction uncertainty [2]. In drug development, where metabolic fluxes are increasingly used as biomarkers or therapeutic targets, underestimating uncertainty could lead to misplaced confidence in compound efficacy or mechanism of action.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Uncertainty Quantification

Bayesian 13C-MFA Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Cultivate cells under metabolic steady-state conditions

- Administer 13C-labeled substrates (commonly [U-13C]glucose or other tracers)

- Harvest cells rapidly using quenching protocols to preserve metabolic state

- Extract intracellular metabolites

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Analyze mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) using LC-MS or GC-MS

- Quantify positional labeling where possible using tandem MS [20]

- Measure extracellular flux rates (substrate uptake, product secretion, growth rates)

Computational Analysis with BayFlux [2]:

- Define stoichiometric model with atom mappings

- Specify prior distributions for fluxes based on physiological constraints

- Run Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling to obtain posterior flux distributions

- Assess chain convergence using diagnostic statistics

- Analyze posterior distributions to determine credible intervals for all fluxes

Figure 1: Bayesian 13C-MFA Workflow for Uncertainty Quantification

Multi-Model Inference Protocol

The Bayesian model averaging (BMA) approach addresses model uncertainty, which is often overlooked in conventional 13C-MFA:

Experimental Design:

- Conduct parallel labeling experiments with multiple tracers when possible [20]

- Ensure measurements capture sufficient information for flux resolution

Model Specification:

- Define multiple candidate model structures representing alternative metabolic hypotheses

- Specify prior probabilities for each model based on biological knowledge

Bayesian Model Averaging [23]:

- Calculate marginal likelihood for each model given the experimental data

- Compute posterior model probabilities

- Average flux predictions across models, weighted by model probabilities

- Report flux distributions that account for both parameter and model uncertainty

Computational Tools and Software Solutions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Flux Uncertainty Quantification

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Uncertainty Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13CFLUX(v3) [26] | Software platform | High-performance 13C-MFA simulation | Supports Bayesian inference; Isotopically stationary/nonstationary |

| BayFlux [2] | Method implementation | Bayesian flux estimation for genome-scale models | Full posterior distributions for all fluxes |

| COBRApy [27] | Python package | Constraint-based modeling and FBA | Flux variability analysis; Sampling |

| ECMpy [27] | Python package | Enzyme-constrained metabolic modeling | Incorporates enzyme abundance uncertainty |

| BRENDA [27] | Database | Enzyme kinetic parameters | Provides Kcat ranges for uncertainty estimation |

Software Implementation Workflow

Figure 2: Computational Tool Ecosystem for Flux Uncertainty Analysis

Case Studies and Validation

Escherichia coli Flux Analysis

A re-analysis of E. coli labeling data using Bayesian methods revealed situations where conventional 13C-MFA approaches could be misleading. Theorell and colleagues demonstrated that "Bayesian model averaging (BMA) for flux inference alleviates the problem of model selection uncertainty" [23]. In their analysis, BMA assigned low probabilities to both models unsupported by data and overly complex models, functioning as a "tempered Ockham's razor."

The BayFlux developers applied their method to E. coli and made the surprising discovery that "genome-scale models of metabolism produce narrower flux distributions (reduced uncertainty) than the small core metabolic models traditionally used in 13C-MFA" [2]. This counterintuitive result highlights how proper uncertainty quantification can challenge established assumptions in the field.

Metabolic Engineering Applications

Uncertainty-aware flux analysis has demonstrated practical value in metabolic engineering. The developers of BayFlux showed that their uncertainty quantification framework enabled the creation of P-13C MOMA and P-13C ROOM, which "improve on the traditional MOMA and ROOM methods by quantifying prediction uncertainty" [2]. This allows metabolic engineers to assess the confidence in predicted outcomes of genetic modifications before conducting laborious experiments.

Future Directions and Recommendations

The field of flux uncertainty quantification is rapidly evolving, with several promising research directions:

Multi-omics Integration: Future methods will better integrate flux uncertainty with uncertainties in other omics data, creating unified probabilistic models of cellular physiology.

Improved Experimental Design: Uncertainty quantification enables model-based experimental design, where new experiments are chosen specifically to reduce uncertainty in critical fluxes.

Automated Workflows: Tools like 13CFLUX(v3) are moving toward more automated and user-friendly implementations, making robust uncertainty quantification accessible to non-specialists [26].

Community Standards: As noted in validation literature, "adopting robust validation and selection procedures can enhance confidence in constraint-based modeling as a whole and ultimately facilitate more widespread use" [20].

Researchers should adopt uncertainty quantification as a standard practice rather than an optional add-on. As the case studies demonstrate, ignoring flux uncertainty risks physiological misinterpretation, while proper uncertainty quantification leads to more robust biological insights and engineering outcomes.

Metabolic fluxes, representing the rates of biochemical reactions within a cell, are fundamental descriptors of cellular state in health, disease, and biotechnology [28]. Unlike metabolite concentrations, fluxes cannot be measured directly but must be estimated through computational modeling that integrates various types of experimental data and physiological constraints [29]. The core challenges in flux estimation involve dealing with underdetermined biological systems, where infinite flux distributions could theoretically satisfy basic cellular requirements. Researchers address this through constraint-based modeling, which applies known biological limits to narrow the solution space to physiologically relevant possibilities [27] [30]. The accuracy of flux estimates depends heavily on properly defining these constraints and understanding their impact on confidence intervals, which remains an active area of research critical for reliable metabolic engineering and drug development.

Fundamental Constraints in Flux Estimation

Stoichiometric Constraints

Stoichiometric constraints form the mathematical foundation of most flux estimation approaches. These constraints are derived from the law of mass conservation, which requires that for each internal metabolite in the network, the total production and consumption must be balanced [30]. This balance is mathematically represented using a stoichiometric matrix (S), where rows correspond to metabolites and columns represent reactions. The matrix elements are stoichiometric coefficients indicating the number of moles of each metabolite consumed (negative values) or produced (positive values) in each reaction.

Under the steady-state assumption, the system is described by the equation S·v = 0, where v is the vector of reaction fluxes. This equation defines the solution space of all possible flux distributions that satisfy mass balance constraints. For a genome-scale metabolic model like iML1515 for E. coli (containing 2,719 metabolic reactions and 1,192 metabolites), this creates a high-dimensional solution space that must be further constrained by additional biological considerations [27].

Metabolic Steady State Assumption

The steady-state assumption is a key constraint enabling flux estimation by asserting that internal metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, while fluxes can be non-zero [30]. This assumes perfect balance between metabolite production and consumption, ignoring transient concentration changes that occur in actual cellular environments. While this simplification makes genome-scale modeling tractable, it represents a significant limitation for modeling dynamic metabolic responses.

The application of these fundamental constraints defines the solution space for flux distributions. However, additional constraints are necessary to narrow this space to biologically relevant solutions and quantify the confidence in predicted fluxes.

Comparative Analysis of Flux Estimation Methods

Various computational approaches have been developed to solve the flux estimation problem, each with different strengths, limitations, and applications in metabolic research.

Methodologies and Workflows

Table 1: Comparison of Major Flux Estimation Methods

| Method | Core Approach | Data Requirements | Scale of Application | Handling of Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Linear programming to optimize an objective function under stoichiometric constraints | Stoichiometric matrix, exchange reaction bounds, objective function | Genome-scale | Solution space analysis (FVA) provides flux ranges |

| Enzyme-Constrained FBA (ecFBA) | Adds enzyme capacity constraints to FBA | Protein abundance, enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat) | Genome-scale with enzyme limitations | Incorporates enzyme allocation constraints |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) | Uses isotope labeling patterns to estimate fluxes | ¹³C labeling data, atom mapping, often absolute metabolite concentrations | Pathway-scale (central carbon metabolism) | Statistical evaluation provides confidence intervals |

| Machine Learning ML-Flux | Neural networks mapping isotope patterns to fluxes | Historical ¹³C labeling data from multiple tracers for training | Central carbon metabolism | Inherited from training data variability |

| Flux-Sum Coupling Analysis (FSCA) | Studies interdependencies between metabolite flux-sums | Stoichiometric matrix, flux distributions | Genome-scale | Identifies coupling relationships between metabolites |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Flux Estimation Methods

| Method | Computational Speed | Flux Prediction Accuracy | Application to Dynamic Systems | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ¹³C-MFA | Slow (iterative least-squares fitting) | High for core metabolism | Limited (stationary assumption) | High (requires expert knowledge) |

| ML-Flux | Rapid (once trained) | >90% accuracy vs. MFA [28] | Limited in current implementation | Medium (requires training data) |

| FBA | Fast | Variable (depends on constraints) | Possible with dFBA extension | Low to Medium |

| ecFBA | Medium | Improved realism vs. FBA [27] | Limited | High (requires enzyme parameters) |

The workflows of these methods follow different pathways from experimental data to flux estimates, as illustrated in the following diagrams:

Figure 1: FBA uses stoichiometry and optimization to predict fluxes.

Figure 2: MFA uses isotope labeling and iterative fitting.

Figure 3: ML-Flux uses neural networks to directly map labeling patterns to fluxes.

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Machine learning approaches like ML-Flux demonstrate significant advantages in computational efficiency, performing flux calculations more rapidly than traditional least-squares methods used in conventional MFA [28]. In accuracy benchmarks, ML-Flux achieved correct flux predictions >90% of the time when compared to established MFA software, with most flux predictions in central carbon metabolism falling within ±0.05 flux units of reference values [28].

For constraint-based methods like FBA, the introduction of enzyme constraints significantly improves prediction realism. For example, in modeling L-cysteine overproduction in E. coli, incorporating enzyme constraints via the ECMpy workflow prevented unrealistically high flux predictions by accounting for limited enzyme capacity and catalytic efficiency [27].

The flux-sum concept has been validated as a reliable proxy for metabolite concentrations, with flux-sum coupling analysis (FSCA) successfully capturing qualitative associations between metabolite concentrations in E. coli [31]. This approach identified that directional coupling is the most prevalent relationship in metabolic networks (16.56% in E. coli iML1515), while full coupling is the rarest (0.007%) due to its more restrictive nature [31].

Advanced Concepts: Addressing Estimation Uncertainty

Confidence Interval Quantification

Quantifying confidence intervals for metabolic flux estimates remains challenging due to the nonlinear relationship between measurements and estimated parameters. In traditional MFA, confidence intervals are typically determined through statistical evaluation such as Monte Carlo sampling or sensitivity analysis of the residual sum of squares [29]. The precision of flux estimates depends heavily on the specific tracer used, the coverage of measured labeling patterns, and the metabolic network structure.

Machine learning approaches like ML-Flux derive their uncertainty characteristics from the training data. The standard errors for individual flux predictions can be derived from the distributions of prediction errors in test data, with reported relative standard deviations of 0.10 for net fluxes and 0.68 for exchange fluxes in central carbon metabolism models [28].

Emerging Approaches and Innovations

Recent methodological advances address uncertainty in flux estimation through various innovative approaches:

Local approaches for isotopically nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA), including kinetic flux profiling (KFP) and ScalaFlux, reduce computational complexity by focusing on sub-networks, thus improving the stability of flux estimation for specific pathways [29].

Flux-sum coupling analysis (FSCA) introduces a novel way to study metabolite interdependencies by categorizing metabolite pairs as fully, partially, or directionally coupled based on their flux-sum relationships, providing additional constraints for flux estimation [31].

Quantum computing algorithms show potential for addressing computational bottlenecks in flux balance analysis, particularly for large-scale models or dynamic simulations that strain classical computational resources [7].

Experimental Protocols for Flux Analysis

Protocol 1: Enzyme-Constrained Flux Balance Analysis

The ECMpy workflow for implementing enzyme constraints in FBA involves these key steps [27]:

Model Preparation: Begin with a genome-scale metabolic model like iML1515 for E. coli. Update Gene-Protein-Reaction associations based on curated databases like EcoCyc.

Reaction Processing: Split all reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions to assign separate kcat values. Similarly, split reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into independent reactions.

Parameter Incorporation:

- Obtain enzyme molecular weights from subunit composition in EcoCyc

- Set total protein fraction constraint (typically 0.56 for E. coli)

- Acquire protein abundance data from PAXdb

- Collect kcat values from BRENDA database

Engineering Modifications: Modify kcat values and gene abundances to reflect genetic engineering. For example, in L-cysteine overproduction, the PGCD reaction kcat was increased from 20 1/s to 2000 1/s to reflect mutant enzyme activity [27].

Gap Filling: Identify and add missing reactions critical for the studied pathways through gap-filling methods.

Medium Configuration: Set uptake reaction bounds according to experimental medium composition.

Lexicographic Optimization: First optimize for biomass, then constrain growth to a percentage (e.g., 30%) of optimal before optimizing for production flux.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Flux Estimation with ML-Flux

The ML-Flux framework implements these key procedures [28]:

Training Data Generation:

- Simulate isotope labeling patterns across a physiological flux space for 26 key ¹³C-glucose, ²H-glucose, and ¹³C-glutamine tracers

- Use log-uniform flux sampling for optimal learning

- Cover multiple metabolic network scales from toy models to central carbon metabolism

Network Architecture:

- Implement artificial neural networks (ANN) with neurons transforming isotope labeling patterns into flux predictions

- Employ partial convolutional neural networks (PCNN) with convolution filters and binary masks to impute missing isotope patterns

- Train separate networks for different metabolic models

Flux Prediction:

- Input experimental isotope labeling patterns

- Impute missing patterns using PCNN

- Predict free fluxes using ANN

- Calculate remaining fluxes using null space basis of the metabolic model

Validation:

- Use reserved testing data for performance assessment

- Compare predictions with traditional MFA results

- Calculate standard errors for individual flux predictions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Flux Estimation

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| iML1515 | Metabolic Model | Genome-scale E. coli model with 1,515 genes, 2,719 reactions | Constraint-based modeling, FBA [27] |

| BRENDA Database | Kinetic Database | Enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat values) | Enzyme-constrained modeling [27] |

| PAXdb | Protein Abundance Database | Protein abundance data for multiple organisms | Enzyme allocation constraints [27] |

| EcoCyc | Metabolic Database | Curated E. coli genes and metabolism database | GPR associations, metabolic network validation [27] |

| ¹³C-labeled Tracers | Isotope Reagents | Substrates with specific positional labeling | MFA, INST-MFA, flux validation [28] [29] |

| COBRApy | Software Toolbox | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | FBA implementation, model simulation [27] |

| ECMpy | Software Workflow | Adding enzyme constraints to metabolic models | ecFBA implementation [27] |

| INCA | Software Toolbox | Isotopic non-stationary metabolic flux analysis | INST-MFA implementation [29] |

The estimation of metabolic fluxes within the constraints of stoichiometry and steady-state assumptions remains a challenging yet essential endeavor in metabolic research. While traditional methods like FBA and MFA provide established frameworks, emerging approaches including machine learning, flux-sum analysis, and quantum algorithms offer promising directions for addressing current limitations in scalability, uncertainty quantification, and dynamic application. The confidence in flux estimates varies significantly across methods, with ¹³C-MFA providing statistical confidence intervals, FBA offering solution space boundaries, and machine learning approaches deriving uncertainty from training data distributions. As the field advances, the integration of multiple constraint types and methodological innovations will continue to enhance the precision and biological relevance of metabolic flux estimates, ultimately supporting more effective drug development and metabolic engineering strategies.

From Linearized Statistics to Bayesian Inference: A Practical Guide to Flux CI Methods

In the field of 13C-based Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), quantifying the intracellular fluxes of living cells is fundamental for advancing metabolic engineering and biotechnology [32]. A critical part of this process is not only estimating the fluxes themselves but also quantifying the confidence intervals for these metabolic flux estimates, which represent their statistical reliability [32]. For years, traditional linearized statistics have been a cornerstone methodology for this purpose. This guide objectively compares the performance of this established approach against emerging alternatives, providing supporting data and detailed methodologies to inform researchers and scientists in their selection of flux analysis tools.

Understanding Traditional Linearized Statistics in MFA

In 13C-MFA, the core computational problem is a large-scale non-linear parameter estimation, where the goal is to find the set of flux parameters that minimizes the difference between experimentally observed and simulated isotope labeling patterns [32] [28]. After this optimization, assessing the uncertainty of the determined fluxes is crucial.

Traditional linearized statistics (also referred to as linearized-based search algorithms) are one of the primary methods used for this task [32]. This approach relies on linearizing the non-linear model around the optimal flux solution to approximate the confidence intervals and flux resolution [32]. Essentially, it estimates how much the fitted fluxes would vary if the experiment were repeated, under the assumption that the model behaves linearly in the immediate vicinity of the solution. This method provides an approximation of the flux covariance matrix, allowing researchers to report fluxes with associated standard errors or confidence ranges [32].

Applications and Role in the MFA Workflow

Traditional linearized statistics are deeply integrated into the standard 13C-MFA workflow. Their primary application is in the evaluation of flux statistics following the determination of a flux map that provides a good fit to the experimental data [32].

- Goodness-of-fit testing: After flux optimization, linearized statistics contribute to assessing the adequacy of the applied metabolic model [32].

- Flux identifiability: They help draw conclusions about which fluxes are reliably determined (identifiable) by the available data [32].

- Contribution matrix construction: This method can be used to construct a contribution matrix that reflects the relative impact of individual measurement variances on the overall uncertainties of the estimated fluxes [32].

This approach is implemented in several high-performance computational software suites, including 13CFLUX2 [32] and OpenFLUX [32], making it a widely accessible and utilized tool in the field.

Limitations and a Comparison with Modern Alternatives

Despite its widespread use, the linearized approach has recognized limitations, which have motivated the development and adoption of complementary and alternative methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Statistical Methods for Flux Confidence Intervals in MFA

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Linearized Statistics | Linear approximation of the model around the optimal flux solution [32]. | Computationally efficient [32]. | May produce inaccurate confidence intervals for highly non-linear problems or with large data variances [32]. |

| Monte Carlo Approach | Uses repeated random sampling to simulate the distribution of flux estimates [32]. | More precise determination of confidence intervals; robust for non-linear models [32]. | Computationally intensive and time-consuming [32]. |

| Machine Learning (ML-Flux) | Trained neural networks directly map isotope patterns to fluxes, bypassing iterative fitting [28]. | Extremely fast (>1000x faster) and accurate; can impute missing data [28]. | Requires large, pre-computed training datasets; "black box" nature may lack intuitive model interaction [28]. |

A significant limitation of the linearized method is that it may produce inaccurate confidence intervals for highly non-linear problems or in the presence of large data variances [32]. Consequently, for precise determination of flux confidence intervals, a fine-tunable and convergence-controlled Monte Carlo-based method is often recommended as a more robust, though computationally expensive, alternative [32].

More recently, a paradigm shift is emerging with machine learning frameworks like ML-Flux, which uses pre-trained neural networks to directly compute mass-balanced metabolic fluxes from isotope labeling patterns [28]. This approach bypasses the traditional iterative model-fitting and subsequent statistical analysis altogether, offering a dramatic increase in speed and the ability to handle more complex datasets [28].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MFA Flux Calculation Methods

| Performance Metric | Traditional Least-Squares Method (e.g., in 13CFLUX2, OpenFLUX) | Machine Learning Method (ML-Flux) |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Speed | Slow (iterative fitting) [28] | Rapid (direct function mapping) [28] |

| Flux Prediction Accuracy | Good, but can be limited by network size [28] | High (>90% of the time more accurate than traditional software) [28] |

| Handling of Large Networks | Becomes computationally expensive [28] | Maintains high performance [28] |

| Handling of Missing Data | Limited, may require data removal [28] | Can impute missing isotope patterns [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

To objectively compare these methods, specific experimental protocols can be employed. The following methodology outlines a approach for generating data to benchmark traditional statistics against alternatives like Monte Carlo or ML-Flux.

Protocol: Benchmarking Flux Confidence Interval Methods

1. Biological Cultivation and Labeling Experiment:

- Organism: Saccharomyces cerevisiae (or other model organism like E. coli) [33].

- Culture Media: Use both synthetic defined (SD) medium and complex media (e.g., YPD) to investigate different metabolic states [33].

- 13C Tracers: Employ a Parallel Labeling Experiment (PLE) strategy using multiple 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C2]-glucose, [U-13C]-glucose, 13C-glutamine) to generate rich, complementary labeling data [32] [28].

2. Analytical Measurement:

- Extracellular Fluxes: Measure substrate uptake and product excretion rates during cultivation [32].

- Isotope Labeling Patterns: Use Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Tandem MS (MS/MS) to detect the 13C-labeling patterns (mass isotopomer distributions) of intracellular metabolites from central carbon metabolism [32] [28].

3. Computational Flux Analysis & Confidence Interval Calculation:

- Flux Optimization: Use a software suite like OpenFLUX2 or 13CFLUX2 to compute the optimal flux parameters that best fit the experimental labeling data for a given metabolic network model [32].

- Confidence Interval Estimation: For the same optimized flux model, apply three different methods:

- A. Traditional Linearized Statistics: Use the built-in linearized covariance estimation [32].

- B. Monte Carlo Method: Implement a fine-tunable Monte Carlo simulation to determine confidence intervals [32].

- C. Machine Learning Prediction: Input the measured isotope patterns into a pre-trained model like ML-Flux to obtain flux predictions [28].

4. Comparison and Validation:

- Benchmarking: Compare the methods based on computational time, the width of the reported confidence intervals, and their robustness.

- Validation: Where possible, compare flux predictions against known or physiologically expected outcomes to assess real-world accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details essential materials and software used in advanced 13C-MFA studies, particularly those involving method comparisons.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for 13C-MFA

| Item Name | Function / Role in Experiment |

|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates (Tracers) | Carbon sources with specific 13C-atom positions (e.g., [1,2-13C2]-glucose) used to trace metabolic pathway activity and enable flux calculation [32] [28]. |

| Complex Media Components | Nutrient-rich supplements (e.g., Yeast Extract, Peptone in YPD) used to cultivate organisms under physiologically relevant conditions, requiring adapted MFA models [33]. |

| Mass Spectrometer (MS/MS) | Analytical instrument used to measure the mass isotopomer distributions of metabolites, providing the primary 13C-labeling data for flux estimation [32]. |

| OpenFLUX2 Software | Open-source computational tool for performing 13C-MFA, capable of handling both single and parallel labeling experiments and incorporating different statistical methods [32]. |

| ML-Flux Framework | A machine learning-based software that uses pre-trained neural networks to rapidly and accurately compute metabolic fluxes from isotope labeling patterns [28]. |

| 13CFLUX2 Software | A comprehensive software suite for 13C-MFA that implements iterative least-squares fitting and statistical analysis of fluxes [32]. |

Metabolic fluxes, defined as the number of metabolites traversing each biochemical reaction in a cell per unit time, are crucial for assessing and understanding cellular function [2] [34] [35]. Among various analytical techniques, 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C MFA) is widely considered the gold standard for measuring these fluxes in living systems [2] [34]. Traditional 13C MFA operates by leveraging extracellular exchange fluxes alongside data from 13C labeling experiments to calculate the flux profile that best fits the data, typically using small, central carbon metabolic models [2] [36].

However, this conventional approach faces significant limitations, primarily due to the nonlinear nature of the 13C MFA fitting procedure [2] [34]. This nonlinearity means that several flux profiles can fit the same experimental data within experimental error, yet traditional optimization methods provide only a partial or skewed representation, particularly in "non-gaussian" situations where multiple distinct flux regions fit the data equally well [2] [36]. These methods struggle to characterize the full distribution of compatible fluxes and often depend on commercial solvers that are difficult to parallelize [2].

The BayFlux method represents a paradigm shift in this field, employing Bayesian inference and Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to identify the complete distribution of fluxes compatible with experimental data for comprehensive genome-scale models [2] [37]. This approach enables researchers to accurately quantify uncertainty in calculated fluxes, moving beyond the limited confidence intervals of frequentist statistics to provide a probabilistic interpretation that systematically manages data inconsistencies [2]. This article examines how BayFlux transforms uncertainty quantification for metabolic flux estimates, comparing its performance against traditional methodologies and exploring its implications for biomedical research and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: Bayesian vs. Frequentist Approaches in Metabolic Flux Analysis

The Frequentist Paradigm in Traditional 13C MFA

Traditional 13C MFA predominantly operates within the frequentist statistical framework [2]. This approach assumes the existence of a single true vector of fluxes and utilizes Maximum Likelihood Estimators (MLE) to identify this vector [2]. Uncertainty in the resulting flux estimates is represented through confidence intervals, which can be computed through various methods that don't necessarily yield consistent outcomes [2]. This methodology encounters substantial difficulties when multiple flux distributions can equally represent the experimental data, particularly when these solutions are not adjacent in the flux space [2]. The fundamental limitation lies in its point estimation approach, which generates a single result even when numerous flux distributions could produce the same experimental observations [2].

The Bayesian Revolution: Core Principles of BayFlux

In contrast to frequentist methodology, BayFlux implements a Bayesian inference framework that introduces a fundamentally different approach to probability and inference [2]. Rather than seeking a single "true" flux value, Bayesian methods estimate a posterior probability distribution (p(v|y)) representing the probability that a particular flux value (v) is realized, given both prior knowledge and the observed experimental data (y) [2]. This paradigm shift offers several theoretical advantages:

- Probabilistic Interpretation: Systematic management of data inconsistencies through probabilistic modeling [2]

- Uncertainty Quantification: Native representation of flux uncertainty through full probability distributions rather than point estimates with confidence intervals [2]

- Information Integration: Ability to incorporate prior knowledge and update probability distributions as additional data becomes available [2]

The Bayesian approach particularly excels in characterizing complex, multi-modal solution spaces where distinct flux regions fit experimental data equally well, providing a more complete picture of metabolic network capabilities [2].

Markov Chain Monte Carlo Sampling: The Computational Engine

The practical implementation of Bayesian inference in BayFlux relies on Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods to sample the flux space [2] [37]. MCMC algorithms enable efficient exploration of high-dimensional probability distributions that would be computationally intractable through direct calculation [2]. This combination of Monte Carlo flux sampling with Bayesian statistics provides reliable flux uncertainty quantification in a manner that scales efficiently as more data becomes available [2] [37].

Table: Comparison of Statistical Paradigms in Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Feature | Traditional Frequentist 13C MFA | BayFlux Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Maximum Likelihood Estimation | Bayesian Inference |

| Uncertainty Representation | Confidence intervals | Full posterior probability distributions |

| Solution Characterization | Single optimal flux vector | Complete distribution of compatible fluxes |

| Data Inconsistency Handling | Limited, can fail with inconsistent data | Systematic probabilistic management |

| Computational Approach | Optimization algorithms | MCMC sampling |

| Model Scalability | Limited to small core models | Genome-scale models with thousands of reactions |

Methodological Framework: The BayFlux Workflow and Experimental Implementation

Core Components of the BayFlux Methodology

The BayFlux methodology integrates several advanced computational techniques to achieve its revolutionary capabilities. The complete workflow can be visualized as follows:

Experimental Protocol and Implementation