Resolving Network Gaps in Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstructions: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Clinical Application

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are powerful computational tools that predict cellular phenotypes from genomic information, but their predictive accuracy is often hampered by network gaps—missing reactions that disrupt metabolic pathways.

Resolving Network Gaps in Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstructions: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Clinical Application

Abstract

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are powerful computational tools that predict cellular phenotypes from genomic information, but their predictive accuracy is often hampered by network gaps—missing reactions that disrupt metabolic pathways. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying, resolving, and validating these network gaps. We explore the fundamental nature of gap metabolites and blocked reactions, evaluate automated reconstruction tools and manual curation methodologies, present optimization strategies for challenging biological scenarios, and establish robust validation frameworks using experimental data. By integrating comparative analysis of current tools and their applications in biomedical research, this resource aims to enhance the reliability of GEMs for drug discovery, metabolic engineering, and understanding human disease mechanisms.

Understanding Network Gaps: The Fundamental Challenge in Metabolic Reconstruction

Defining Gap Metabolites and Blocked Reactions in Metabolic Networks

Definitions and Core Concepts

What are the fundamental definitions of gaps and blocked reactions in a metabolic network?

| Term | Definition | Type/Category |

|---|---|---|

| Gap Metabolite | A metabolite that cannot carry any steady-state flux, acting as a dead-end in the network [1]. | |

| Root Non-Produced (RNP) Metabolite | A gap metabolite that is only consumed but never produced by any reaction in the network [1] [2]. | Dead-End Metabolite |

| Root Non-Consumed (RNC) Metabolite | A gap metabolite that is only produced but never consumed by any reaction in the network [1] [2]. | Dead-End Metabolite |

| Downstream Non-Produced (DNP) Metabolite | A metabolite that becomes a gap as a consequence of a preceding RNP metabolite [1]. | Derived Gap |

| Upstream Non-Consumed (UNC) Metabolite | A metabolite that becomes a gap as a consequence of a succeeding RNC metabolite [1]. | Derived Gap |

| Blocked Reaction | A reaction that cannot carry a steady-state flux other than zero under any given uptake conditions [1] [3]. | |

| Unconnected Module (UM) | An isolated set of blocked reactions interconnected via gap metabolites [1] [3]. | Network Pathology |

What is the relationship between gap metabolites and blocked reactions? Gap metabolites and blocked reactions are interconnected inconsistencies. A dead-end metabolite (RNP or RNC) will inevitably block all reactions in which it participates. This lack of flux can then propagate through the network, turning other connected metabolites into gaps (DNP or UNC) and blocking further reactions, forming an Unconnected Module [1].

Troubleshooting and Resolution

What are the main strategies for resolving gaps and blocked reactions?

| Strategy | Mechanism Description | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Directionality Reversal | Reversing the directionality of one or more existing irreversible reactions in the model [2]. | Resolve gaps caused by thermodynamic constraints. |

| Add Missing Reactions | Incorporating new reactions from multi-species databases (e.g., MetaCyc, KEGG) to provide missing functionality [1] [2]. | Fill gaps from annotation errors or unknown enzymes. |

| Add Transport Mechanisms | Allowing import/export of the problem metabolite from the extracellular medium [2]. | Resolve gaps in cytosolic metabolites. |

| Add Intracellular Transport | Adding transport reactions between internal compartments (e.g., mitochondria) and the cytosol [2]. | Resolve gaps in multi-compartment models. |

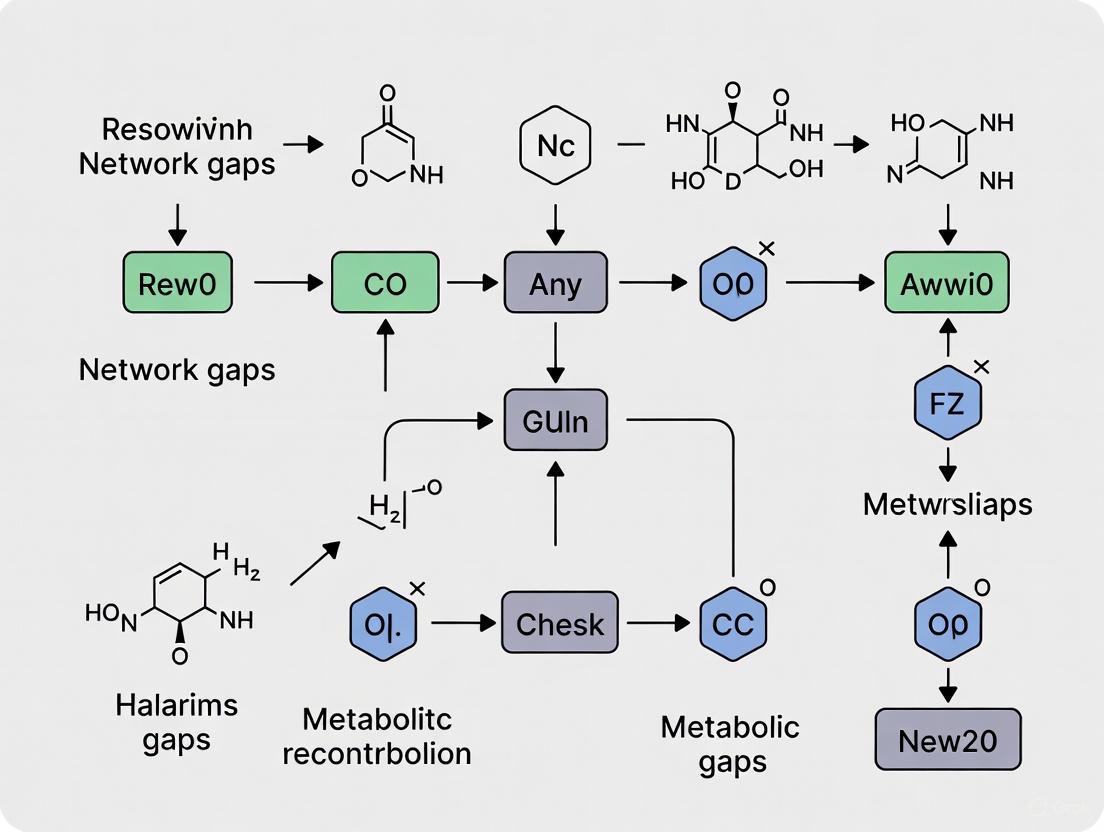

What is a standard workflow for identifying and resolving these inconsistencies? The following diagram outlines a generalized curation workflow that integrates identification and resolution steps [1] [2] [3].

Detection and Analysis Methodologies

What are the key computational methods for detecting network gaps? Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM) provides the mathematical foundation for detecting inconsistencies. The metabolic network is represented by a stoichiometric matrix (N), where rows are metabolites and columns are reactions. The flux space is defined by the steady-state assumption (N·v = 0) and capacity constraints (vlb ≤ v ≤ vub) [1] [3]. A reaction is blocked if its flux (v_j) is zero in all possible steady-state solutions [1]. Tools like COBRApy are commonly used for this analysis [3].

How can I experimentally validate predictions from a curated model? 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is a key experimental technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes. The protocol involves [4] [5]:

- Tracer Experiment: Growing cells on 13C-labeled carbon sources (e.g., [1-13C] glucose).

- Mass Spectrometry: Measuring the resulting isotopic labeling in proteinogenic amino acids and other biomass components using GC-MS.

- Flux Estimation: Using software like Metran to compute metabolic fluxes that best fit the measured labeling patterns, allowing comparison with model predictions [5].

The Researcher's Toolkit

What are the essential reagents, software, and databases for this work?

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Software | A MATLAB/Python toolbox for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis [5]. |

| Model SEED | Platform | An automated pipeline for generating genome-scale metabolic models [3]. |

| MetaCyc | Database | A curated database of metabolic pathways and enzymes used for gap-filling [1] [2] [3]. |

| KEGG | Database | A resource integrating genomic and chemical information for pathway mapping [1] [3]. |

| 13C-labeled Tracers | Reagent | Isotopically labeled substrates (e.g., glucose) for tracing metabolic flux in vivo [4] [5]. |

| GC-MS | Instrument | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry for measuring isotopic labeling in metabolites [4] [5]. |

| 2-(1-Methyl-piperidin-4-ylmethoxy)-ethanol | 2-(1-Methyl-piperidin-4-ylmethoxy)-ethanol, CAS:112391-05-6, MF:C9H19NO2, MW:173.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Formylphenyl benzenesulfonate | 4-Formylphenyl Benzenesulfonate|13493-50-0 | 4-Formylphenyl benzenesulfonate (CAS 13493-50-0) is a key synthetic intermediate for aldose reductase inhibitors and other bioactive molecules. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

What is a detailed protocol for 13C-MFA to validate network functionality? This protocol is adapted from high-resolution 13C-MFA methods [5].

Experimental Design:

- Use two or more parallel cultures with different 13C glucose tracers (e.g., [1-13C] glucose and [U-13C] glucose) for precise flux estimation.

- Ensure cultures are in metabolic steady-state during the labeling experiment.

Sample Generation and Harvesting:

- Grow the microbe in defined medium with the chosen 13C tracer.

- Quench metabolism rapidly during mid-exponential growth phase.

- Hydrolyze cellular biomass to release proteinogenic amino acids and other polymers.

Isotopic Labeling Measurement:

- Derivatize the hydrolyzed amino acids and other metabolites for GC-MS analysis.

- Analyze samples via GC-MS to obtain mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs).

- Measure labeling in glycogen-bound glucose and RNA-bound ribose for additional flux information.

Flux Computation and Statistical Analysis:

- Input the measured MIDs, network model, and extracellular fluxes into 13C-MFA software (e.g., Metran).

- Estimate intracellular fluxes by finding the best fit between simulated and measured labeling data.

- Perform comprehensive statistical analysis to determine goodness of fit and calculate confidence intervals for the estimated fluxes.

What is the optimization-based (GapFill) procedure for automatic gap-filling? This computational protocol identifies the minimal set of reactions to add from a database to restore network connectivity [2].

- Input: A metabolic model with identified gap metabolites and a reference reaction database (e.g., MetaCyc).

- Problem Formulation: A Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem is set up where binary variables represent the presence or absence of candidate reactions from the database.

- Objective Function: The objective is to minimize the number of added reactions required to allow the production of all biomass precursors or to eliminate all gap metabolites.

- Solution: The solution provides a parsimonious set of reactions that, when added to the model, resolve the structural gaps. These reactions serve as testable hypotheses for missing metabolic functions.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are network gaps and why are they a problem in metabolic models? Network gaps are inconsistencies in genome-scale metabolic reconstructions that manifest as metabolites which cannot be produced or consumed under any condition, preventing a steady-state flux. These gaps lead to erroneous predictions of gene essentiality and flawed simulations of metabolic capabilities, compromising the model's utility for research and metabolic engineering [1] [2].

2. What is the fundamental difference between a Root Non-Produced and a Root Non-Consumed metabolite? A Root Non-Produced (RNP) metabolite is one that the model can only consume but never produce. Conversely, a Root Non-Consumed (RNC) metabolite is one that the model can only produce but never consume [1] [2]. These are the primary, or "root," causes of network pathology.

3. How do root gap metabolites cause other parts of the network to become blocked? The inability to produce an RNP metabolite means no flux can pass through it. This lack of flux is propagated "downstream," blocking any reaction that consumes it and creating Downstream-Non-Produced (DNP) metabolites. Similarly, the inability to consume an RNC metabolite blocks flux "upstream," creating Upstream-Non-Consumed (UNC) metabolites [1] [2].

4. What are the main strategies for filling these network gaps? Several computational strategies exist to restore connectivity:

- Reverse Reaction Directionality: Changing the bounds of an existing reaction to allow it to operate in the reverse direction [2].

- Add Missing Reactions: Incorporating reactions from universal databases (e.g., KEGG, MetaCyc) that are supported by genomic evidence [2] [6].

- Add Transport Reactions: Allowing the import of RNP metabolites from the extracellular environment or transport between cellular compartments [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Network Gaps

Objective

To systematically identify Root Non-Produced (RNP) and Root Non-Consumed (RNC) metabolites in a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction and implement appropriate solutions to resolve them.

Experimental Protocol & Methodologies

Step 1: Detect Root Gap Metabolites The first step is to run a gap-finding algorithm on your metabolic model. Tools like GapFind can be used for this purpose [2] [7].

- Procedure: Execute the algorithm on your model, typically represented in Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) format, under a specified medium condition (defining available nutrients).

- Output: The algorithm scans the stoichiometric matrix and returns two lists: one for RNP metabolites (only consumed, never produced) and one for RNC metabolites (only produced, never consumed) [1] [2].

Step 2: Analyze the Propagation of Blocked Flux Manually or algorithmically trace the pathways connected to each root gap metabolite to identify the sets of blocked reactions and the resulting DNP and UNC metabolites. This helps visualize the full extent of the problem [1].

Step 3: Implement Gap-Filling Strategies For each root gap metabolite, apply one or more of the following solutions in an iterative manner:

Solution A: Check Reaction Reversibility

- Methodology: Query biochemical databases like EcoCyc/MetaCyc or use thermodynamic data (reaction free energy change, ΔG) to assess if an existing reaction in the model should be reversible [2].

- Example: Reversing a reaction that consumes an RNP metabolite can provide a production route, solving the gap.

Solution B: Add Missing Metabolic Reactions

- Methodology: Search multi-organism reaction databases (KEGG, BioCyc, BiGG) for reactions that produce the RNP metabolite or consume the RNC metabolite. Add the best-supported reaction to the model [2] [8].

- Genomic Evidence: Use BLAST searches to find homologous genes in your target organism that could catalyze the proposed reaction [2] [6].

Solution C: Add Transport Reactions

- Methodology: If the metabolite is available in the extracellular environment (e.g., a nutrient), add a transport reaction to allow its uptake. For multi-compartment models, adding intracellular transport between organelles can also resolve gaps [2].

Step 4: Validate the Cured Model After gap-filling, validate your updated model by testing its predictions against experimental data, such as growth phenotypes on different carbon sources or gene essentiality data [7]. This ensures that the changes improve the model's accuracy without introducing new errors.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for troubleshooting network gaps.

Key Data and Comparison

Table 1: Classification and Properties of Network Gap Metabolites

| Metabolite Type | Abbreviation | Definition | Origin in Network | Example Resolution Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root Non-Produced [1] [2] | RNP | Only consumed, never produced by any model reaction. | Primary pathology. | Add a producing reaction or a transport reaction for import. |

| Root Non-Consumed [1] [2] | RNC | Only produced, never consumed by any model reaction. | Primary pathology. | Add a consuming reaction or a secretion reaction. |

| Downstream Non-Produced [1] [2] | DNP | Becomes non-produced as a consequence of an upstream RNP metabolite blocking its production pathway. | Secondary, propagated effect. | Resolve the connected RNP metabolite. |

| Upstream Non-Consumed [1] [2] | UNC | Becomes non-consumed as a consequence of a downstream RNC metabolite blocking its consumption pathway. | Secondary, propagated effect. | Resolve the connected RNC metabolite. |

Table 2: Summary of Gap-Filling Solutions and Their Applications

| Solution Type | Mechanism | Typical Use Case | Key Tools / Databases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Directionality [2] | Changes thermodynamic constraints of an existing reaction to allow backward flux. | Fixing RNPs when a reversible reaction was incorrectly annotated as irreversible. | MetaCyc, BRENDA, thermodynamic calculations (ΔG) |

| Add Metabolic Reaction [2] [6] | Incorporates a new enzymatic reaction from a reference database into the model. | Filling knowledge gaps where a metabolic step is missing from the reconstruction. | KEGG, BioCyc, BiGG, ModelSEED |

| Add Transport Reaction [2] | Allows metabolite exchange between model compartments (e.g., cytosol & extracellular space). | Fixing RNPs for nutrients available in the growth medium. | Transport databases, literature curation |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item / Resource | Function in Gap Analysis and Resolution |

|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | The core mathematical representation of the metabolic network, where rows are metabolites and columns are reactions. Used by algorithms to identify dead-end metabolites [1]. |

| Universal Reaction Databases (KEGG, MetaCyc, BiGG) | Provide curated lists of biochemical reactions and pathways used to identify and add missing metabolic functions during gap-filling [2] [8]. |

| Genome Annotation | Provides the initial gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations. Re-evaluation of annotation is often necessary to find genes for "orphan" reactions that fill gaps [1] [6]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | A constraint-based modeling technique used to simulate network behavior and validate that gap-filling restores desired metabolic functions, such as growth [1] [8]. |

| GapFind / GapFill Algorithms | Computational procedures (e.g., from the COBRA toolbox) that automatically detect gap metabolites and propose minimal sets of reactions to resolve them [2] [7]. |

| Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) | A standard computational format for representing and exchanging metabolic models, enabling the use of various software tools for curation and analysis [6] [8]. |

| 1,4-Bis(phenoxyacetyl)piperazine | 1,4-Bis(phenoxyacetyl)piperazine|Research Chemical |

| 4-Bromo-2,6-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyridine | 4-Bromo-2,6-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyridine, CAS:134914-92-4, MF:C7H2BrF6N, MW:293.99 g/mol |

The Impact of Reductive Evolution on Metabolic Networks in Host-Associated Organisms

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Network Gaps in Metabolic Reconstructions

Common Problems & Solutions

1. Problem: My draft reconstruction has insufficient biomass production.

- Question: Why does my automatically generated draft model fail to produce biomass in simulations, even when key nutrients are provided?

- Solution: This is a classic symptom of network gaps. Implement a two-step, parsimony-based gap-filling protocol.

- Step 1: Use a tool like Reconstructor to perform gap-filling based on parsimonious Flux Balance Analysis (pFBA). This method adds a minimal set of non-gene-associated reactions that minimizes total network flux while achieving a defined objective, such as biomass production [9]. It is more biologically tractable than methods based solely on gene-reaction rules.

- Step 2: Manually inspect and validate the gap-filled reactions. Check if the added reactions are consistent with known parasite biochemistry (e.g., reliance on host-provided purines) [10].

2. Problem: My model of an obligate parasite is unrealistically large.

- Question: The automated reconstruction for my parasitic organism includes metabolic pathways that it is known to have lost. How can I correct this?

- Solution: Leverage comparative genomics to inform the reconstruction process.

- Method: Use a comparative framework like CoReCo (Comparative Reconstruction). This method simultaneously reconstructs networks for multiple related species using a phylogenetic tree. It computes enzyme probabilities for each species and assembles gapless networks, favoring reactions with high sequence evidence and adding low-probability reactions only when necessary to resolve gaps [11]. This approach is particularly useful for evolutionary distant or poorly sequenced species.

- Action: Run your parasite's genome through a comparative pipeline with both free-living and parasitic relatives. This helps the algorithm correctly identify and exclude pathways that were lost during reductive evolution.

3. Problem: I cannot analyze my model with standard tools like COBRApy.

- Question: The output from my reconstruction tool is not compatible with the COBRApy analysis suite, requiring cumbersome conversion modules.

- Solution: Select reconstruction tools that offer direct COBRApy compatibility.

- Recommendation: The Reconstructor package generates Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) models that are directly compatible with COBRApy. This allows for immediate import into Python and seamless use of flux balance analysis, gene knockout simulations, and other essential functions without additional formatting steps [9].

4. Problem: It is difficult to visualize the impact of reductive evolution.

- Question: How can I effectively visualize and communicate the differences between the metabolic network of a parasite and a free-living relative?

- Solution: Utilize modern visualization software to generate organism-scale metabolic diagrams.

- Tool: Use Pathway Tools to generate cellular overview diagrams. These diagrams are automatically laid out from a Pathway/Genome Database (PGDB) and can be customized to highlight specific pathways. The software allows for semantic zooming and can overlay omics data, making it ideal for comparative analysis [12].

- Alternative: Metaboverse provides a user-friendly interface for layering multi-omic data onto dynamic representations of metabolic networks, which can help identify regulatory patterns resulting from reductive evolution [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the typical quantitative changes in a metabolic network after reductive evolution? A1: The table below summarizes the core structural differences between parasitic and free-living metabolic networks, based on comparative genomics studies [10].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Core Metabolic Networks

| Network Property | Obligate Endoparasites | Free-Living Eukaryotes | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Nodes (Metabolites) | ~287 | ~483 | Significant loss of metabolic intermediates and diversity. |

| Number of Edges (Reactions) | ~278 | ~539 | Drastic reduction in pathway steps and overall network complexity. |

| Network Diameter | Similar to free-living | Similar to parasites | Network integrity is maintained; the core "small-world" property is preserved despite shrinkage. |

| Average Connectivity | Lower | Higher | Fewer connections per metabolite, indicating a less robust and more fragile network. |

| Key Hub Metabolites | Glycolytic intermediates (e.g., Glyceraldehyde-3-P) | Amino acids, Pyruvate, Acetyl-CoA | Shift in network hubs reflects the loss of biosynthetic capabilities (e.g., for amino acids) and increased reliance on core energy metabolism. |

Q2: Which specific metabolic pathways are commonly lost in obligate endoparasites? A2: Reductive evolution follows a convergent pattern. Commonly lost pathways include [10]:

- Purine de novo synthesis: All obligate endoparasitic protozoa lack this pathway and rely on host-purine salvage.

- Amino acid biosynthesis: Pathways for lysine, tyrosine, and tryptophan are frequently absent.

- Oxidative phosphorylation: Some parasites like Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia duodenalis lack functional mitochondria.

- Krebs cycle: Often incomplete or non-functional in energy metabolism.

Q3: Are there any functional categories of reactions that are preferentially retained? A3: Yes, analysis of core metabolic graphs shows a biased retention of certain reaction types [10].

- Retained: ATP-consuming reactions are retained at a higher percentage.

- Lost: NADH- or NADPH-requiring reactions are lost preferentially. This suggests a evolutionary pressure to maintain energy-generating and utilizing functions critical for survival inside the host, while dispensing with redox-balance and complex biosynthetic functions.

Experimental Protocols for Network Analysis

Protocol 1: Detecting Reductive Evolution with Comparative Genomics

Objective: To identify metabolic pathways lost in a host-associated organism by comparing it to a free-living relative.

Materials & Workflow:

- Input Data: Gather annotated genome sequences (amino acid FASTA files) for your target parasite and a curated, free-living reference organism (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae).

- Reconstruction: Use an automated reconstruction tool (e.g., Reconstructor or CoReCo) to generate genome-scale metabolic models (GENREs) for both organisms.

- Pathway Comparison: Use a database like KEGG to map the reactions from each GENRE to specific metabolic pathways.

- Analysis: Systematically compare the presence/absence of pathways between the two models. The absence of entire pathways (e.g., purine synthesis) in the parasite that are present in the free-living relative is a strong indicator of reductive evolution.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for this protocol:

Protocol 2: Gap-Filling a Draft Parasite Reconstruction

Objective: To add biologically plausible reactions to a draft metabolic model to enable basic metabolic functions like biomass production.

Materials & Workflow:

- Input: A draft GENRE in SBML format and a defined growth medium composition.

- Set Objective: Define the biomass reaction as the simulation objective.

- Run Gap-filling: Use the pFBA-based gap-filling algorithm in Reconstructor. This algorithm identifies a minimal set of non-gene-associated reactions from a universal database (e.g., ModelSEED) that, when added, allows the model to achieve the objective while minimizing total flux [9].

- Manual Curation: Critically evaluate the added reactions. Check the literature to confirm that the gap-filled reactions are not part of pathways known to be absent in your parasite (e.g., a purine synthesis reaction should not be added to a protozoan parasite model).

The workflow for this gap-filling process is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Metabolic Reconstruction and Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Reductive Evolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstructor [9] | Software Package | Automated, COBRApy-compatible GENRE generation and pFBA-based gap-filling. | Creates high-quality draft models from sequence data and uses a biologically tractable method to resolve network gaps. |

| CoReCo [11] | Computational Framework | Comparative, gapless metabolic reconstruction for multiple related species. | Leverages phylogenetic data to correctly infer pathway loss and resolve gaps in poorly annotated parasites. |

| Pathway Tools [12] | Bioinformatics Software | Generation of organism-scale metabolic network diagrams (Cellular Overviews). | Visualizes the shrunken metabolic network of a parasite and allows comparison with free-living organisms. |

| ModelSEED Database [9] | Biochemical Database | Universal database of balanced metabolic reactions, metabolites, and biomass equations. | Serves as the foundational biochemistry database for tools like Reconstructor during model building and gap-filling. |

| KEGG Pathway [10] | Pathway Database | Curated collection of pathway maps and associated enzymes. | Used for mapping model reactions to pathways to systematically identify which pathways are missing in parasites. |

| MEMOTE [9] | Testing Suite | Suite for evaluating and quality-checking genome-scale metabolic models. | Benchmarks the quality of a reconstructed parasite model to ensure it meets community standards. |

| 1-(5-Nitropyridin-2-yl)piperidin-4-ol | 1-(5-Nitropyridin-2-yl)piperidin-4-ol, CAS:353258-16-9, MF:C10H13N3O3, MW:223.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| N-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)benzenesulfonamide | N-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)benzenesulfonamide Research Chemical | High-purity N-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)benzenesulfonamide for research applications. Explore its properties as a sulfonamide derivative. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are "Unconnected Modules" in the context of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs)? Unconnected Modules (UMs) are isolated sets of blocked reactions within a metabolic network that are interconnected through gap metabolites [1]. They represent a structural inconsistency where a group of reactions is completely disconnected from the primary metabolic network that can carry a steady-state flux, meaning these reactions cannot function under any simulated condition [1] [14].

What is the fundamental difference between a gap metabolite and a blocked reaction? A gap metabolite is a node in the network through which no steady-state flux can occur [14]. These are often "dead-end" metabolites. A blocked reaction is a reaction that cannot carry any non-zero flux in a steady state; its flux is always zero in every possible simulation [1] [14]. UMs form when blocked reactions become connected via gap metabolites, creating an isolated sub-network [1].

Why is identifying Unconnected Modules more informative than just listing all blocked reactions? Identifying UMs groups related inconsistencies, simplifying the curation process. Instead of addressing hundreds of individual blocked reactions, a researcher can focus on correcting a few key pathways to resolve an entire module at once. This provides a clearer visual representation and helps understand the nature of the gaps, making the manual curation process more efficient [1].

My model has many blocked reactions. Does this mean the reconstruction is of poor quality? Not necessarily. While a high number of blocked reactions can indicate missing annotations or knowledge gaps, they are a common feature in draft reconstructions [14]. One large-scale analysis found that about 22% of reactions were blocked across 130 different bacterial GEMs [14]. The presence of UMs is a starting point for iterative model improvement and refinement.

Can automatic gap-filling completely resolve Unconnected Modules? Automatic gap-filling algorithms can propose solutions, but manual inspection of UMs is often still required [1]. This is especially true for specialized metabolisms, such as those in endosymbiotic bacteria, where automatic methods might suggest non-biological reactions. Manual curation guided by UM analysis ensures that the added reactions are biologically relevant to the specific organism [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: A Set of Reactions is Permanently Inactive (Blocked)

Issue During Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), you discover that a group of reactions consistently carries zero flux across all simulation conditions, indicating they are blocked.

Solution Follow this systematic protocol to identify the Unconnected Module containing these reactions and find the root cause.

Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Detect All Blocked Reactions Run a constraint-based modeling analysis to classify all reactions in your model as either blocked or functional. This can be done using algorithms that test each reaction's ability to carry a non-zero flux at steady state [1] [14]. The core constraint is the steady-state mass balance:

N.v = 0, whereNis the stoichiometric matrix andvis the flux vector [1].Step 2: Identify Gap Metabolites Scan the stoichiometric matrix to find dead-end metabolites. These are of two primary types [1]:

- Root-Non-Produced (RNP): Metabolites that are only consumed but not produced by any reaction in the model.

- Root-Non-Consumed (RNC): Metabolites that are only produced but not consumed by any reaction in the model. The absence of flux through these root metabolites can propagate through the network, creating secondary gap metabolites (DNP and UNC) [1].

Step 3: Map the Unconnected Module This is a crucial diagnostic step. Treat your network as a bipartite graph (with metabolite and reaction nodes). Using the list of blocked reactions and gap metabolites from Steps 1 and 2, apply a connected components algorithm to find isolated sub-networks. These sub-networks are your Unconnected Modules [1]. Visualizing this module, as in the diagram below, clarifies the relationships between the inconsistencies.

Step 4: Analyze the UM and Propose Solutions Inspect the visualized UM to determine the most biologically plausible gap-filling strategy.

- If the UM lacks a connection to a consumed metabolite (RNP): Identify the RNP metabolite (e.g., Metabolite A in the diagram). The solution is to add a reaction that produces this metabolite, linking it to the main network. This could be a transport reaction from the extracellular medium or a connecting biosynthetic reaction [1].

- If the UM lacks a connection to a produced metabolite (RNC): Identify the RNC metabolite (e.g., Metabolite D). The solution is to add a reaction that consumes this metabolite [1].

- Validate candidate reactions by checking genomic evidence (e.g., EC numbers, gene annotations) and biochemical databases to ensure the solution is plausible for your organism [1] [14].

Step 5: Implement and Re-test Add the proposed reactions to your model and re-run the blocked reaction analysis from Step 1. A successfully resolved UM will no longer appear as isolated, and its reactions should now be able to carry flux.

Problem: Gap-Filling Introduces Non-Biological Reactions

Issue After using an automated gap-filling algorithm, the model's predictions seem biologically implausible, suggesting the algorithm may have added reactions that are not native to the organism.

Solution Use a manually curated metamodel (a large, consistent reference network) as the source for gap-filling instead of a generic reaction database.

Experimental Protocol

- Obtain or Build a Curated Metamodel: A metamodel is created by merging multiple individual GEMs into a single, large network [14]. This metamodel must first undergo rigorous consistency analysis and manual curation to remove its own UMs and artifacts [14].

- Embed Your Model: Place your GSM within the curated metamodel.

- Run Context-Specific Gap-Filling: Use an algorithm like a modified Fastcore to activate reactions within the metamodel that are strictly necessary to connect the UMs in your model, while respecting GPR rules [14].

- Review Proposed Reactions: The algorithm will suggest a set of reactions from the metamodel to add to your model. Because the metamodel is curated, these suggestions are more likely to be biologically consistent than those from an uncurated universal database [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential tools and databases for identifying and resolving unconnected modules.

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| ModelSEED [14] [8] | Pipeline for automatic draft model reconstruction and analysis. | Provides a standardized starting point for generating models that can subsequently be analyzed for UMs. |

| Pathway Tools [8] | Software for visualizing metabolic networks and predicting pathway gaps. | Allows visual inspection of metabolic networks, which is crucial for understanding the structure of a UM. |

| BiGG Models [1] [8] | A knowledgebase of high-quality, curated genome-scale metabolic reconstructions. | Serves as an excellent source of reference reactions for manual gap-filling during UM resolution. |

| KEGG [1] [8] | Database for linking genomic information with higher-order functional meanings. | Used to map gene annotations (EC numbers) to metabolic reactions and pathways. |

| MetaCyc [1] [14] [8] | An encyclopedia of experimentally defined metabolic pathways and enzymes. | Useful for verifying the existence of biochemical pathways and finding candidate reactions for gap-filling. |

| Fastcore Algorithm [14] | An optimization-based method for context-specific model reconstruction. | Can be used to efficiently identify a minimal set of reactions from a reference database (metamodel) to resolve gaps. |

The table below summarizes quantitative findings from large-scale analyses of metabolic models, highlighting the prevalence and impact of blocked reactions.

| Metric | Value | Context & Source |

|---|---|---|

| Blocked Reactions in GSMs | ~22% | Percentage of reactions that were found to be blocked across a dataset of 130 genome-scale models of bacteria [14]. |

| First GEM (H. influenzae) | 296 genes, 488 reactions | The size and date of the first genome-scale metabolic model [15] [8]. |

| E. coli GEM (iML1515) | 1,515 genes | Number of open reading frames in a high-quality, curated model of E. coli [15]. |

| Total Reconstructed Organisms | 6,239 organisms | The scale of GEM reconstruction as of early 2019, covering bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes [15]. |

How Network Gaps Compromise Flux Balance Analysis Predictions

Troubleshooting Guide: Common FBA Errors Due to Network Gaps

This guide addresses frequent issues researchers encounter when network gaps disrupt Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) predictions in metabolic models.

FAQ 1: Why does my model fail to produce biomass even when key nutrients are present?

- Problem: Your FBA simulation predicts zero or negligible biomass production despite providing what should be sufficient nutrients in your in silico medium.

- Root Cause: This is a classic symptom of network gaps. Essential metabolic reactions are missing from the model, preventing the synthesis of one or more biomass precursors (e.g., a specific amino acid, lipid, or cofactor). The model cannot create a connected metabolic path from the available nutrients to the required biomass components [16].

- Solution:

- Identify the Blocked Metabolites: Use a tool like

GapFindto determine which biomass precursors cannot be produced [16]. - Locate the Gap: Trace the metabolic pathway of the missing precursor backwards to find where the pathway becomes disconnected.

- Fill the Gap: Use a gap-filling algorithm like

GapFillorFBA-Gapto propose a biologically plausible reaction from a universal database (e.g., MetaCyc, KEGG) that restores connectivity [16] [17]. Manually curate the proposed reaction to ensure it is supported by genomic evidence for your organism.

- Identify the Blocked Metabolites: Use a tool like

FAQ 2: Why does my model predict growth on an unrealistic or minimal medium?

- Problem: The model suggests the organism can grow in conditions that are known experimentally to be impossible, such as a medium lacking an essential nutrient.

- Root Cause: Network gaps are often masked by implausible exchange reactions. A gap-filling algorithm may have added an exchange reaction that allows the model to directly import a metabolite that it should synthesize internally, creating a "short-circuit" in the metabolic network [16].

- Solution:

- Audit Exchange Reactions: Review all exchange reactions in the model, especially those added during automated reconstruction.

- Apply Biological Constraints: Assign high metabolic costs to exchange reactions for internal metabolites and low costs for uptake from the extracellular space. Algorithms like

FBA-Gapuse this principle to propose more biologically plausible solutions [16]. - Validate with Experiments: Compare the model's predicted essential nutrients against known experimental data to identify discrepancies.

FAQ 3: Why are the predicted fluxes through a pathway illogically high or low?

- Problem: FBA predictions show metabolically unrealistic flux distributions, such as extremely high flux through a few reactions or the use of a non-native pathway over the primary one.

- Root Cause: A missing enzymatic reaction can force the model to utilize a longer, less efficient, or non-existent detour pathway to achieve the objective [16].

- Solution:

- Analyze Flux Loops: Check for thermodynamically infeasible cyclic flux patterns that can arise from network gaps and incorrect constraints.

- Inspect High-Flux Pathways: Manually examine pathways carrying abnormally high flux to see if they are compensating for a blocked reaction in a more direct pathway.

- Compare with Omics Data: Overlay transcriptomic or proteomic data to see if the model is actively using reactions that are not expressed in your organism, indicating a potential gap in the native pathway.

FAQ 4: How can I identify which specific reaction is missing?

- Problem: You know a pathway is incomplete but cannot pinpoint the exact gap.

- Root Cause: Manual identification of gaps in large, genome-scale models is time-consuming and error-prone.

- Solution:

- Use Pathway Topology Tools: Tools like

Pathway Toolscan visualize your metabolic network, allowing you to visually identify dead-ends and disconnected metabolites [8] [12]. - Perform Metabolite Tracing: Systems biology software can trace the production and consumption paths of a metabolite to find where the path is broken.

- Leverage Comparative Genomics: Compare your model with a high-quality, well-curated model of a closely related organism to identify reactions that are likely present in your organism but missing from your model [17].

- Use Pathway Topology Tools: Tools like

Experimental Protocols for Gap Resolution

Protocol 1: Systematic Gap Identification Using FBA-Gap

Objective: To identify a minimal set of biologically plausible network gaps preventing biomass production.

Methodology:

- Input: A genome-scale metabolic reconstruction that fails to produce biomass and a universal reaction database (e.g., BIGG, MetaCyc) [16] [17].

- Algorithm Setup: The

FBA-Gapalgorithm formulates a linear programming problem where the objective is to minimize the cost of added exchange reactions required to achieve a target biomass flux [16]. - Cost Assignment:

- Low cost is assigned to exchange reactions for metabolites that exist in the extracellular compartment.

- High cost is assigned to exchange reactions for internal metabolites.

- This cost structure ensures the algorithm prioritizes adding transport reactions over creating metabolically impossible shortcuts [16].

- Output Interpretation: The algorithm outputs a set of proposed exchange reactions and a flux distribution. The high-cost exchange reactions indicate internal metabolites that are stuck due to network gaps, directing the modeler to the precise location of the problem [16].

Protocol 2: Comparative Reconstruction for Gap-Filling

Objective: To fill gaps by leveraging existing knowledge from well-annotated organisms.

Methodology:

- Template Selection: Select one or more high-quality, manually curated metabolic models from phylogenetically related organisms to use as templates [17].

- Tool Application: Use a reconstruction tool like

RAVENorMetaDraftthat supports template-based reconstruction [17]. - Homology Mapping: The tool maps the template model(s) to your organism's genome using homology detection (e.g., BLAST) to identify and transfer probable reactions [8].

- Model Merging: The tool creates a draft model for your organism by merging the reactions with genetic evidence from the homology search [17].

- Curation: Manually review the added reactions to confirm their biological relevance to your organism.

The following table summarizes key software tools for metabolic reconstruction and gap-filling, as systematically assessed in [17].

| Tool | Primary Function | Database Source | Key Feature / Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | De Novo Reconstruction | BIGG | Uses a top-down approach from a universal model; prioritizes reactions with genetic evidence [17]. |

| ModelSEED | Web-based Reconstruction | RAST / ModelSEED | Fully automated pipeline from genome annotation to model simulation [17]. |

| RAVEN | Reconstruction & Curation | KEGG, MetaCyc, Template Models | MATLAB-based; integrated with COBRA Toolbox for advanced analysis [17]. |

| Pathway Tools | Reconstruction & Visualization | MetaCyc, BioCyc | Generates organism-specific databases and visualizes full metabolic networks [8] [12]. |

| AuReMe | Reconstruction | MetaCyc, BIGG | Provides excellent traceability of the entire reconstruction process [17]. |

| CoReCo | Comparative Reconstruction | KEGG | Simultaneously reconstructs models for multiple related species [17]. |

| Item | Function in Gap Resolution |

|---|---|

| Universal Reaction Database (e.g., BIGG, MetaCyc) | Provides a comprehensive set of known biochemical reactions used as a source to fill identified gaps [8] [17]. |

| High-Quality Template Models (e.g., from BioCyc) | Manually curated models of related organisms used for comparative reconstruction to transfer knowledge of conserved pathways [17]. |

| Genome Annotation Tool (e.g., RAST) | Provides the initial set of metabolic functions inferred from the organism's genome, forming the basis of the draft reconstruction [17]. |

| Gap-Filling Algorithm (e.g., FBA-Gap, GapFill) | An optimization-based procedure that automatically proposes missing reactions to restore model functionality [16]. |

| Visualization Software (e.g., Pathway Tools) | Allows researchers to visually inspect the metabolic network to identify dead-end metabolites and disconnected pathways [12]. |

Workflow Diagrams for Gap Resolution

FBA Gap Identification and Resolution

Metabolic Network Gap Visualization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the main biological causes of gaps in genome-scale metabolic reconstructions? Gaps arise from two primary biological sources: incomplete genome annotation and unknown enzyme functions. Even in well-studied organisms like Escherichia coli, approximately 35% of genes lack experimental evidence of function, creating "orphan" metabolic activities [18]. Furthermore, a significant portion of known enzyme activities (30-50%) cannot be associated with specific genes, and over 50% of genes in higher organisms are not linked to a defined protein function [19].

How do incomplete annotations lead to incorrect model predictions? When a metabolic model (GEM) lacks annotations for genes that are non-essential for growth in vivo, it results in false-negative essentiality predictions. The model incorrectly identifies a gene as essential because it is unaware of alternative biochemical pathways that can compensate for its loss in a living cell [18]. For example, in the E. coli model iML1515, 148 genes were falsely predicted as essential, linked to 152 blocked reactions [18].

What is the difference between a blocked reaction and a dead-end metabolite? A blocked reaction is a reaction that cannot carry any metabolic flux due to network connectivity issues. This is often caused by dead-end metabolites, which are compounds that are either only produced (root no-consumption) or only consumed (root no-production) in the network, preventing mass balance [19]. In the human metabolic reconstruction RECON 1, 175 blocked reactions were found across 80 such reaction cascades [19].

Can gaps reveal truly novel metabolic functions? Yes. Gaps pinpoint regions where biological components and functions are "missing," and their systematic analysis can direct hypotheses for novel metabolic functions [19]. Automatically generated solutions to fill these gaps have been shown to produce biologically realistic hypotheses, such as novel roles for iduronic acid in glycan degradation and for N-acetylglutamate in amino acid metabolism [19].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High False-Negative Essentiality Predictions in Your GEM

Symptoms: Your model predicts that a gene is essential for growth, but experimental knockout data shows the organism survives and grows.

Diagnosis: The model lacks knowledge of alternative biochemical pathways that can bypass the reaction catalyzed by the "essential" gene. This is a knowledge gap in the reconstruction [18].

Solutions:

- Apply a computational gap-filling workflow: Use tools like NICEgame, which leverages databases of known and hypothetical biochemical reactions (e.g., the ATLAS of Biochemistry) to propose alternative pathways that reconcile model predictions with experimental data [18].

- Integrate multiple types of functional evidence: For candidate genes, look beyond sequence homology. Use a combination of evidence including chromosomal clustering with known enzyme-encoding genes, similarity of phylogenetic profiles, and gene co-expression data to strengthen functional predictions [20].

Problem: Identifying Genes for Orphan Metabolic Activities

Symptoms: You have experimental evidence for a specific metabolic function (e.g., enzyme activity assay) but no gene or protein is annotated to carry out this function in the genome.

Diagnosis: This is a classic "missing gene" problem, where the gene encoding the enzyme is not identified by sequence homology to known enzymes [20].

Solutions:

- Prioritize candidates using functional associations: Evaluate non-annotated genes based on their overall functional association with the neighborhood of the missing metabolic enzyme. This network-based approach can prioritize candidates even without direct sequence homology [20].

- Leverage genome context methods: Methods that detect gene clustering on the chromosome, co-occurrence across phylogenetic lineages (phylogenetic profiles), and other functional associations have proven effective in identifying missing metabolic genes [20].

Quantitative Data on Metabolic Gaps

Table 1: Gap Statistics in Published Metabolic Reconstructions

| Organism / Model | Type of Gap | Number Identified | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (iML1515) [18] | False-Negative Essential Genes | 148 genes | Associated with 152 essential reactions in the model. 47% of these gaps were resolved using hypothetical reactions from the ATLAS of Biochemistry. |

| Human (RECON 1) [19] | Blocked Reactions | 175 reactions | Caused by 109 dead-end metabolites. Over half of the blocked reactions were due to root no-consumption metabolites. |

| Human (RECON 1) [19] | Sub-cellular Location of Gaps | Majority in cytosol | Most dead-end metabolites and blocked reactions were found in the cytosol, with others in lysosomes, mitochondria, and peroxisomes. |

Table 2: Performance of a Functional Association Method for Predicting E. coli Metabolic Enzymes [20]

| Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|

| Predictions within top 10 candidates | 60% of cases |

| Predictions as the top candidate | 43% of cases |

| Types of Functional Evidence Used | Chromosomal clustering, phylogenetic profiles, gene expression, protein fusion events. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: The NICEgame Workflow for Characterizing Metabolic Gaps

Purpose: To identify and curate non-annotated metabolic functions in genomes using known and hypothetical reactions, thereby enhancing genome annotation and metabolic model accuracy [18].

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Harmonization: Ensure metabolite identifiers in the GEM are consistent with those in the ATLAS of Biochemistry database to allow proper connectivity [18].

- Gap Identification: Preprocess the GEM by defining the growth medium and perform gene essentiality analysis. Compare in silico knockout results with experimental data (e.g., from mutant libraries) to identify false-negative predictions—these are the metabolic gaps [18].

- Model Merging: Create an "ATLAS-merged GEM" by integrating the biochemical reaction space from the ATLAS of Biochemistry into your GEM [18].

- Comparative Analysis: Re-run the essentiality analysis on the merged model. Identify reactions/genes that were essential in the original GEM but are no longer essential in the merged model. These are the "rescued" targets for gap-filling [18].

- Solution Generation: Systematically identify sets of known or hypothetical reactions from the ATLAS that can bypass the rescued reaction [18].

- Solution Ranking: Rank the proposed solution sets. Prefer solutions that maintain or improve biomass yield, do not reduce model flexibility, and do not add redundant functionality. Thermodynamic feasibility can be a key ranking criterion [18].

- Gene Proposal: Use a tool like BridgIT to map the proposed novel biochemical reactions to candidate genes in the genome, based on knowledge of substrate reactive sites [18].

Protocol 2: Identifying Missing Enzymes Using Functional Association Evidence

Purpose: To predict genes encoding for a specific metabolic function by leveraging multiple types of functional association evidence, without relying solely on sequence homology [20].

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Define the Problem: Select a metabolic reaction in your model that is missing an associated gene (the "missing enzyme") [20].

- Map the Neighborhood: Identify the local metabolic network around the missing enzyme. This typically includes:

- Layer 1 (L1): Enzymes that produce or consume the same metabolites as the missing enzyme (direct connection).

- Layer 2 (L2): Enzymes connected to the L1 enzymes.

- Layer 3 (L3): Enzymes connected to the L2 enzymes [20].

- Gather Association Evidence: For all candidate genes in the genome (e.g., genes of unknown function), compile multiple types of functional association data with the known enzyme-encoding genes in the defined neighborhood (L1, L2, L3). Key evidence includes:

- Phylogenetic Profiles: Co-occurrence of genes across different phylogenetic lineages.

- Gene Clustering: Physical proximity on the chromosome.

- Gene Co-expression: Correlation in transcriptomic data.

- Protein-Protein Interactions: Evidence from interaction screens [20].

- Calculate and Combine Scores: For each candidate gene, compute a layer association score for each neighborhood layer (L1, L2, L3) based on the strength of its functional associations with the enzymes in that layer. Combine these layer scores using a method like Annotated Decision Tree (ADT) or Direct Linear Regression (DLR) to get an overall association score [20].

- Prioritize Candidates: Rank all candidate genes based on their overall association score. The top-ranked genes are the most likely to encode the missing metabolic function [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Databases and Tools for Gap Resolution Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Gap Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| ATLAS of Biochemistry [18] | Database | A repository of over 150,000 known and hypothetical biochemical reactions between known metabolites. Used to suggest novel biochemistry to fill network gaps. |

| BridgIT [18] | Computational Tool | Maps proposed novel biochemical reactions to candidate genes and proteins by leveraging knowledge of enzyme active sites and substrate reactive sites. |

| SMILEY Algorithm [19] | Computational Tool | An algorithm used to propose reactions from universal databases (e.g., KEGG) that can be added to a model to restore flux through a blocked reaction or dead-end metabolite. |

| NICEgame Workflow [18] | Integrated Workflow | A comprehensive workflow that integrates GEM analysis, the ATLAS of Biochemistry, and BridgIT to characterize and curate metabolic gaps at the reaction and enzyme level. |

| KEGG / SSDB [20] | Database | Provides orthology data (closest homologs, best bi-directional hits) used to construct phylogenetic profiles, a key type of functional association evidence. |

Methodological Approaches and Tools for Gap Resolution and Model Reconstruction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary difference between top-down and bottom-up reconstruction approaches?

Tools like CarveMe use a top-down approach, starting with a universal, curated template model and removing reactions without genomic evidence [21]. In contrast, gapseq and ModelSEED use a bottom-up approach, building a draft model by mapping annotated genomic sequences to reactions before assembling the network [21]. The choice impacts model structure; bottom-up methods often yield larger, more reaction-dense models, while top-down methods can be faster [21].

Q2: My model has many dead-end metabolites. How can I resolve this?

Dead-end metabolites—compounds that cannot be produced or consumed by the network—are a common form of network gap. To address them:

- Review Gap-Filling: Investigate the gap-filling solutions proposed by your tool. gapseq, for instance, uses a novel Linear Programming (LP)-based algorithm that incorporates network topology and sequence homology to fill gaps more intelligently [22].

- Manual Curation: Use biochemical databases (e.g., MetaCyc, KEGG) to identify and add missing transport or metabolic reactions that consume or produce the dead-end metabolite [23] [24].

- Consensus Modeling: Consider building a consensus model by merging reconstructions of the same organism from different tools (e.g., CarveMe, gapseq, KBase). This approach has been shown to reduce the number of dead-end metabolites [21].

Q3: How accurate are these automated tools compared to manual curation?

Automated tools provide excellent starting points but vary in predictive accuracy. A large-scale validation using 10,538 experimental enzyme activities across 3,017 organisms found that gapseq had a significantly lower false negative rate (6%) compared to CarveMe (32%) and ModelSEED (28%) [22]. However, for mission-critical applications, manual refinement using literature and experimental data for your specific organism is always recommended [23] [24].

Q4: How do I validate and test the quality of my reconstructed model?

Standardized community tools are essential for quality control:

- MEMOTE (MEtabolic MOdel TEsts): This is a key tool that provides a comprehensive report evaluating a model's syntax, biochemical consistency (mass and charge balance), network topology, and annotation coverage [25] [23].

- SBML Validator: Ensures your model file is syntactically correct and machine-readable [25].

- Phenotype Comparison: Test your model's predictions against known experimental data, such as carbon source utilization or gene essentiality, to assess its biological accuracy [22] [23].

Q5: Can I use these models to simulate microbial community interactions?

Yes, GEMs are powerful tools for studying communities. You can use compartmentalized models or costless secretion approaches [21]. Be aware that the prediction of exchanged metabolites can be highly dependent on the reconstruction tool used. Consensus modeling can help mitigate this tool-specific bias and provide a more robust prediction of community interactions [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Fails to Produce Biomass

A model that cannot produce biomass under expected conditions indicates critical network gaps.

Diagnosis and Solution Workflow:

- Step 1: Verify Growth Medium Constraints. Ensure the model's exchange reactions accurately reflect the nutrients available in your in silico growth medium. An incorrect or overly restrictive medium is a common cause of failure.

- Step 2: Perform Gap Analysis. Use built-in functions (e.g.,

gapAnalysisin the COBRA Toolbox [23]) to identify metabolites that cannot be synthesized from the provided medium. This pinpoints the root cause of the blockage. - Step 3: Investigate Automated Gap-Filling. Tools like gapseq automatically perform gap-filling to enable biomass production. Examine which reactions were added during this process, as they may point to missing metabolic capabilities or annotation errors [22].

- Step 4: Manual Curation. If gaps persist, manually curate the model. Use BLAST to search for missing enzyme genes in the target genome, and add validated reactions from databases like KEGG or MetaCyc [23] [24].

Problem: Inaccurate Prediction of Gene Essentiality

The model incorrectly predicts that growth is possible when a gene is knocked out, or vice versa.

Diagnosis and Solution Workflow:

- Step 1: Inspect Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Associations. An incorrect GPR is a primary suspect. Ensure the logical relationships (AND/OR) between genes and reactions are accurate. A missing "AND" can make a gene seem non-essential.

- Step 2: Check for Undetected Isozymes. The model may lack annotation for an isozyme that can compensate for the knocked-out gene. Manual search for homologous genes can identify these missing functions [24].

- Step 3: Look for Alternative Metabolic Pathways. The organism might use a different enzymatic route not captured in the model. Consulting organism-specific literature and biochemical databases can help identify and add these pathways.

- Step 4: Validate the Biomass Reaction. An incorrect biomass composition (e.g., missing an essential biomass precursor) will lead to flawed essentiality predictions. Compare your biomass reaction with those from closely related, well-curated models [23] [24].

Platform Comparison and Performance Data

The table below summarizes key characteristics and performance metrics of the automated reconstruction platforms, based on recent comparative studies.

| Feature / Metric | CarveMe | ModelSEED | gapseq | RAVEN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction Approach | Top-Down [21] | Bottom-Up [21] | Bottom-Up [21] | Not Specified in Results |

| Core Database | Not Specified | ModelSEED [21] | Curated ModelSEED-derived [22] | Not Specified |

| False Negative Rate (Enzyme Activity) | 32% [22] | 28% [22] | 6% [22] | Data Not Available |

| True Positive Rate (Enzyme Activity) | 27% [22] | 30% [22] | 53% [22] | Data Not Available |

| Community Model Metabolite Exchange | Tool-specific bias observed [21] | Tool-specific bias observed [21] | Tool-specific bias observed [21] | Data Not Available |

| Key Strength | Fast generation of ready-to-use models [21] | Integrated RAST annotation pipeline [8] | Accurate enzyme and carbon source prediction [22] | Not Available from Search |

| Resource | Type | Function in Reconstruction & Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| MEMOTE [25] | Software Tool | Suite of tests for evaluating genome-scale metabolic model quality, including stoichiometric consistency and annotation. |

| COBRA Toolbox [23] | Software Suite | A MATLAB environment for performing constraint-based reconstruction and analysis, including simulation and gap-filling. |

| MetaNetX [25] | Database/Platform | A platform for accessing, analyzing, and manipulating genome-scale metabolic models, useful for comparing namespaces. |

| KEGG / BioCyc / MetaCyc [8] [24] | Biochemistry Databases | Encyclopedic resources of metabolic pathways, reactions, and enzymes used for manual curation and gap resolution. |

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot [23] | Protein Database | A curated protein sequence database used for functional annotation of genes via BLASTp. |

| BiGG Models [25] [8] | Database | A knowledgebase of curated, genome-scale metabolic reconstructions that can be used as high-quality references. |

| GUROBI / COBRApy [23] | Solver/Software | Optimization solvers and Python interfaces used to perform Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and other simulations. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary purpose of the MetaCyc database in gap-filling? MetaCyc serves as a curated reference database of experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways and enzymes. Its primary role in gap-filling is to provide a high-quality, evidence-based set of reactions from which algorithms can select candidates to add to draft metabolic models, enabling them to produce essential biomass metabolites. Unlike organism-specific databases, MetaCyc is a multi-organism resource that aims to include a representative example of as many experimentally determined metabolic pathways as possible, making it a comprehensive knowledge base for resolving network gaps [26] [27].

FAQ 2: My gap-filled model contains incorrect reactions. How can I improve the biological relevance of the solutions? A prevalent cause of incorrect gap-filling solutions is the existence of multiple alternative ways to fill a network gap using the same reaction database. To guide the algorithm toward more biologically relevant reactions, use a method that incorporates taxonomic weighting. This approach assigns lower costs (higher priority) to reactions that are frequently found in organisms within the same taxonomic group as your target organism. Evaluation of this method showed a significant increase in accuracy, raising the F1-score to 99.0 compared to 91.0 with a basic gap-filler on E. coli models [28].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between phenotypic and topological gap-filling methods?

- Phenotypic (Optimization-based) Methods: These methods require experimental data, such as known growth phenotypes on specific media, as input. They identify inconsistencies between model predictions and experimental data and add reactions to resolve these discrepancies [29] [30].

- Topological (Network-based) Methods: These methods, such as

FastGapFill, rely solely on the structure of the metabolic network. They identify dead-end metabolites that cannot be produced or consumed and add reactions to restore network connectivity without requiring experimental data [31] [30]. Newer machine learning methods like CHESHIRE also fall into this category, using hypergraph learning to predict missing reactions [30].

FAQ 4: How does the choice of growth media during gap-filling affect my model? The media condition specifies the metabolites available to the model and directly influences which reactions the gap-filling algorithm will add. Using "complete" media (an abstraction containing all transportable compounds in a database) will typically result in the algorithm adding many transport reactions. In contrast, using a minimal media forces the algorithm to add reactions that allow the model to biosynthesize many necessary substrates itself. It is often a good practice to perform initial gap-filling on minimal media to ensure the model develops a more complete biosynthetic capability [29].

FAQ 5: What are the limitations of current automated gap-filling algorithms? Despite their utility, gap-filling algorithms have several limitations:

- They can introduce incorrect reactions due to multiple alternative solutions [28].

- They often struggle to resolve false-positive predictions (where the model grows in simulation but not in the lab) because the issue may stem from unknown regulatory constraints rather than missing reactions [31].

- They may have difficulty accurately annotating transport reactions and their substrate specificity, which is a major source of uncertainty [32].

- The solutions provided are predictions and almost always require manual curation to ensure biological accuracy [29].

Database Comparison Tables

Table 1: Core Features of Metabolic Databases

| Feature | MetaCyc | KEGG | BRENDA | BioCyc Collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Curated metabolic pathways & enzymes | Integrated knowledge of genomes, diseases, drugs | Comprehensive enzyme functional data | Organism-specific Pathway/Genome Databases (PGDBs) |

| Curation Level | Literature-based manual curation [27] | Automated & manual | Manual curation | Varies by tier (Tier 1: heavily curated; Tier 3: computationally inferred) [26] |

| Pathway Content | 2,609 pathways (as of 2017) [26] | Not specified in results | Not a pathway database | Contains computationally predicted pathways for specific organisms [27] |

| Reaction Content | 18,819 enzymatic reactions [27] | Not specified in results | Not a reaction database | Derived from genome annotations and reference DBs like MetaCyc [26] |

| Key Application in Gap-Filling | Reference database for high-quality, experimentally backed reaction candidates | Not explicitly mentioned in results | Not explicitly mentioned in results | Used in taxonomic weighting to find reactions prevalent in related organisms [28] |

Table 2: Quantitative Overview of MetaCyc Database Content

| Entity Type | Count | Details and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Organisms | 3,443 | Represented in the database through curated pathways and enzymes [27] |

| Pathways | 3,128 | Experimentally elucidated, non-redundant pathways; involved in primary and secondary metabolism [27] |

| Enzymatic Reactions | 18,819 | Includes reactions with EC numbers and those without [27] |

| Literature Citations | 76,283 | Links to primary sources from which data was curated [27] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Taxonomic Weighting for Improved Gap-Filling

Background: This methodology enhances a standard optimization-based gap-filler by biasing it towards reactions that are phylogenetically relevant to the target organism, thereby increasing the biological accuracy of the solution [28].

Materials:

- A draft genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) with identified gaps (unproducible biomass metabolites).

- An annotated genome for the target organism.

- The MetaCyc database or another universal reaction database.

- Software: Pathway Tools with the MetaFlux gap-filler or a similar tool that allows for custom reaction weighting [28].

- Access to a set of BioCyc PGDBs or other metabolic models for related organisms.

Method:

- Identify Taxonomic Group: Determine the phylum (or other appropriate taxonomic rank) of your target organism (e.g., E. coli belongs to Proteobacteria).

- Calculate Reaction Frequencies: For each candidate reaction

Rin the universal database (e.g., MetaCyc), calculate its frequency within the target phylum. This is done by analyzing how many PGDBs for organisms in that phylum contain reactionR. - Assign Costs: Convert reaction frequencies into costs. A higher frequency in the target phylum should correspond to a lower cost for that reaction. This makes the algorithm more likely to select phylogenetically common reactions.

- Run Weighted Gap-Filling: Execute the gap-filling algorithm (e.g., MetaFlux's GenDev Technique C) using the taxonomically weighted costs. The algorithm will solve a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem to find a minimal-cost set of reactions that enables biomass production.

- Validate Solution: Verify that the gap-filled model can produce biomass on the specified media using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA).

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Based Reaction Prediction with CHESHIRE

Background: CHESHIRE (CHEbyshev Spectral HyperlInk pREdictor) is a deep learning method that predicts missing reactions in a GEM using only the topology of the existing metabolic network, without requiring experimental phenotype data [30].

Materials:

- A draft GEM in a format that can be represented as a stoichiometric matrix or a hypergraph.

- The CHESHIRE software tool.

- A universal reaction pool (e.g., from MetaCyc or BiGG) to serve as candidate reactions.

Method:

- Hypergraph Construction: Represent the draft metabolic network as a hypergraph. In this representation, each metabolite is a node, and each reaction is a hyperlink connecting all its reactant and product nodes.

- Feature Initialization: Generate an initial feature vector for each metabolite node based on its connectivity to all reactions in the network (the incidence matrix).

- Feature Refinement: Use a Chebyshev spectral graph convolutional network (CSGCN) to refine each metabolite's features by incorporating information from other metabolites it interacts with in reactions.

- Reaction-Level Pooling: For each candidate reaction from the universal pool, compute a single feature vector by pooling (combining) the refined features of all metabolites involved in that reaction.

- Scoring and Selection: Feed the pooled feature vector into a neural network to generate a confidence score for the existence of each candidate reaction in the target organism. Select reactions with high confidence scores to fill the network gaps.

- Validation: The model's performance can be validated by its ability to recover artificially removed reactions (internal validation) and by improved accuracy in predicting fermentation products and amino acid secretion (external validation) [30].

Visual Workflows

Gap-Filling Algorithm Selection Workflow

This diagram outlines a decision process for selecting an appropriate gap-filling strategy based on data availability.

CHESHIRE Hypergraph Learning Process

This diagram illustrates the four major steps of the CHESHIRE machine learning method for predicting missing reactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Tools with MetaFlux | Software for creating, curating, and analyzing PGDBs. Used for constraint-based modeling and includes a gap-filling function that supports taxonomic weighting. [28] | Essential for implementing the taxonomic weighting protocol. |

| SCIP Solver | A state-of-the-art optimization solver for mixed integer linear programming (MILP) problems. Used as the underlying engine in advanced gap-filling algorithms. [29] [28] | Critical for solving the optimization problem in MILP-based gap-filling. |

| GLPK Solver | GNU Linear Programming Kit, a solver for pure-linear optimization problems. Used in some gap-filling formulations that employ Linear Programming (LP). [29] | An alternative solver for LP-based gap-filling approaches. |

| MetaCyc Database | A curated database of experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways and enzymes. Serves as a high-quality reference set of candidate reactions for gap-filling. [26] [27] [28] | The primary source of reactions for many gap-filling algorithms. |

| Biocyc PGDB Collection | A collection of thousands of organism-specific Pathway/Genome Databases. Used to calculate the taxonomic frequency of reactions for weighted gap-filling. [28] | Provides the taxonomic data needed for context-aware gap-filling. |

| CHESHIRE Tool | A deep learning-based method for predicting missing reactions in GEMs using only network topology, requiring no experimental data. [30] | A powerful tool for gap-filling when phenotypic data is unavailable. |

| gapseq Tool | A software for predicting bacterial metabolic pathways and reconstructing models, featuring a novel LP-based gap-filling algorithm that uses homology data. [22] | An automated pipeline that integrates multiple data sources for improved gap-filling. |

| N-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)benzenesulfonamide | N-(2,3-Dichlorophenyl)benzenesulfonamide|CAS 92589-22-5 | N-(2,3-Dichlorophenyl)benzenesulfonamide (CAS 92589-22-5) is a sulfonamide research chemical for laboratory use. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| N'-butanoyl-2-methylbenzohydrazide | N'-Butanoyl-2-methylbenzohydrazide|Research Chemical | Research-use N'-butanoyl-2-methylbenzohydrazide. This benzohydrazide derivative is for lab research only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. |

Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions are powerful systems biology tools that translate genomic information into mathematical models of cellular metabolism, enabling researchers to predict physiological states and metabolic capabilities [8] [33]. The reconstruction process links metabolic and genomic data to build networks ranging from individual pathways to whole-genome representations, which can be analyzed using constraint-based methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [34] [35]. However, a significant challenge in this field is the presence of network gaps—missing reactions or pathways that create discontinuities in metabolic networks, leading to inaccurate phenotypic predictions and limiting biotechnological and biomedical applications [30] [32].

The reconstruction landscape features both manual curation approaches and automated pipelines, each with distinct advantages and limitations. While manual reconstruction remains the gold standard for model quality, it is exceptionally labor-intensive, often requiring six months to two years for completion [35]. Automated tools have emerged to address the growing gap between sequenced genomes and curated models, but they vary substantially in performance, accuracy, and suitability for different applications [22] [6]. This technical analysis provides performance benchmarks, selection criteria, and troubleshooting guidance to help researchers navigate the complex landscape of metabolic reconstruction tools, with particular emphasis on resolving network gaps that impede accurate metabolic modeling.

Performance Benchmarks of Reconstruction Tools

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Reconstruction Tool Performance Benchmarks

| Tool | Enzyme Prediction (True Positive Rate) | Carbon Source Utilization Accuracy | Key Strengths | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gapseq | 53% | High (Experimental validation) | Curated reaction database free of energy-generating cycles; informed gap-filling | Mainly bacterial focus; limited archaeal/eukaryotic reactions |

| CarveMe | 27% | Moderate | Ready-to-use FBA models; reference-based carving | Higher false negative rate (32%) |

| ModelSEED | 30% | Moderate | Automated pipeline; integrated with RAST annotation | Higher false negative rate (28%) |

| CHESHIRE | Superior topology-based gap-filling | Improves phenotypic predictions | Deep learning approach; no phenotypic data required | Limited to topology-based predictions |

| CoReCo | Accurate for poorly-sequenced species | Enables flux balance analysis | Comparative reconstruction; gapless networks | Requires multiple related genomes |

Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate significant performance variations among metabolic reconstruction tools. gapseq substantially outperforms both CarveMe and ModelSEED in enzyme activity prediction, achieving a 53% true positive rate compared to 27% and 30% respectively, based on evaluation against 10,538 experimentally determined enzyme activities across 3,017 organisms [22]. This performance advantage stems from gapseq's curated reaction database and sophisticated gap-filling algorithm that integrates sequence homology and network topology information to resolve network gaps more effectively.