Stoichiometric Inconsistency and Network Gaps: From Detection to Resolution in Metabolic Models

This article explores the critical challenge of stoichiometric inconsistencies in genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) and their role in creating network gaps that impair predictive accuracy. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how these structural errors arise, their impact on flux balance analysis, and the computational methods—from established algorithms like fastGapFill to emerging deep learning tools like CHESHIRE—used to detect and resolve them. The content further covers troubleshooting techniques for error isolation, the validation of gap-filling solutions, and the implications of robust, stoichiometrically consistent models for advancing biomedical research and therapeutic discovery.

Stoichiometric Inconsistency and Network Gaps: From Detection to Resolution in Metabolic Models

Abstract

This article explores the critical challenge of stoichiometric inconsistencies in genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) and their role in creating network gaps that impair predictive accuracy. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how these structural errors arise, their impact on flux balance analysis, and the computational methods—from established algorithms like fastGapFill to emerging deep learning tools like CHESHIRE—used to detect and resolve them. The content further covers troubleshooting techniques for error isolation, the validation of gap-filling solutions, and the implications of robust, stoichiometrically consistent models for advancing biomedical research and therapeutic discovery.

The Root of the Problem: Defining Stoichiometric Inconsistency and Network Gaps

Stoichiometric modeling is a constraint-based methodology used to analyze metabolic networks at the genome scale, relying fundamentally on mass balance principles to predict cellular behavior without requiring detailed kinetic parameters [1]. This approach has become indispensable in systems biology for studying the systemic properties of metabolic networks, providing insight into metabolic plasticity, robustness, and an organism's ability to cope with different environments [2]. The accuracy of these models depends critically on correct stoichiometric specifications, as errors can create network gaps and structural inconsistencies that compromise predictive capability and biological relevance [3] [4].

Stoichiometric models bridge the gap between genomic information and metabolic functionality, enabling researchers to predict metabolic flux distributions, identify essential genes, and pinpoint thermodynamic constraints [1]. In pharmaceutical and biomedical research, these models are particularly valuable for drug target identification, understanding disease mechanisms, and optimizing bioproduction processes [4]. The fundamental principle governing all stoichiometric modeling is mass conservation, which requires that atoms are neither created nor destroyed in biochemical reactions [2] [3].

Mathematical Foundations of Stoichiometric Modeling

The Stoichiometric Matrix and Mass Balance

The cornerstone of stoichiometric modeling is the stoichiometric matrix (denoted as N), which mathematically represents the metabolic network structure [2] [1]. This m × n matrix contains the stoichiometric coefficients of m metabolites participating in n reactions, where each element nij represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j [2].

The rate of change of metabolite concentrations is described by the system of ordinary differential equations:

dx/dt = N · v

where x is the m-dimensional metabolite concentration vector and v is the n-dimensional reaction rate vector [2]. At steady state (a fundamental assumption in most stoichiometric analyses), the time derivatives become zero, reducing the equation to:

N · v = 0

This equation represents the mass balance constraint for each metabolite in the network, indicating that the total production and consumption rates for each metabolite must be equal [2] [1].

Chemical Moisty Conservation

In addition to mass balance, metabolic networks exhibit chemical moiety conservation, where certain chemical groups (e.g., adenosine, phosphate) are conserved within the network [2]. These conservation relationships impose additional constraints on the system and can be expressed mathematically as:

L₀ · x = t

where Lâ‚€ is the moiety conservation matrix, x is the metabolite concentration vector, and t is the vector of total moiety concentrations [2]. These relationships allow for the decomposition of metabolites into dependent and independent sets, reducing the system's complexity.

Table 1: Key Mathematical Components in Stoichiometric Modeling

| Component | Symbol | Description | Role in Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix | N | m × n matrix of stoichiometric coefficients | Defines network structure and mass balance constraints |

| Flux Vector | v | n-dimensional vector of reaction rates | Represents metabolic activity state |

| Metabolite Vector | x | m-dimensional vector of metabolite concentrations | Defines metabolic pool sizes |

| Kernel Matrix | K | Null-space matrix of N | Contains all steady-state flux solutions |

| Moiety Matrix | Lâ‚€ | Conservation relationship matrix | Defines conserved chemical groups |

Methodologies and Analytical Approaches

Core Stoichiometric Modeling Techniques

Several computational methodologies have been developed within the stoichiometric modeling framework, each with distinct purposes and mathematical implementations [1].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a widely used constraint-based approach that predicts metabolic flux distributions by optimizing an objective function (e.g., biomass production, ATP synthesis) subject to stoichiometric constraints [2] [5]. FBA formulates metabolism as a linear programming problem:

Maximize cᵀ · v subject to N · v = 0 and α ≤ v ≤ β

where c is the vector of objective coefficients, and α and β are lower and upper bounds on fluxes [1] [5].

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) utilizes measured extracellular fluxes in combination with the stoichiometric model to determine intracellular fluxes that cannot be directly measured [4] [1]. The flux estimation is typically performed as a weighted least-squares problem:

Minimize ‖(rout - rin) - S · v‖² subject to α ≤ v ≤ β

where rout and rin are measured external metabolite excretion and uptake rates [4].

Network-Based Pathway Analysis identifies systemic properties of metabolic networks by analyzing the set of pathways through the network [1]. This includes methods like Elementary Flux Modes (EFMs) and Extreme Pathways (ExPas), which represent minimal sets of reactions that can operate at steady state [2].

Protocols for Metabolic Network Analysis

Protocol 1: Stoichiometric Model Construction and Validation

- Network Reconstruction: Compile all metabolic reactions from genome annotation databases and biochemical literature [4]

- Stoichiometric Matrix Assembly: Construct the N matrix with metabolites as rows and reactions as columns [2]

- Mass Balance Verification: Check that each reaction is atomically balanced using atomic mass analysis (AMA) [3]

- Moiety Conservation Analysis: Identify conserved chemical moieties using left null-space analysis of N [2]

- Gap Filling: Identify and fill network gaps using biochemical databases and computational tools like OptFill [6]

- Model Validation: Compare predictions with experimental data (e.g., gene essentiality, growth rates) [4]

Protocol 2: Flux Balance Analysis Implementation

- Objective Function Definition: Select appropriate biological objective (e.g., biomass maximization) [5]

- Constraint Specification: Define environmental conditions through exchange reaction bounds [1]

- Linear Programming Solution: Solve the optimization problem using algorithms like simplex or interior point methods [5]

- Solution Space Characterization: Use tools like CoPE-FBA to comprehensively enumerate optimal flux spaces [5]

- Flux Variability Analysis: Determine the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal objective value [2] [5]

- Validation with Experimental Data: Compare predictions with measured flux data, if available [4]

Table 2: Common Stoichiometric Modeling Methods and Applications

| Method | Mathematical Basis | Primary Application | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Linear Programming | Prediction of optimal flux distributions | Optimal flux vector and objective value |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) | Least-Squares Regression | Determination of intracellular fluxes from extracellular measurements | Complete flux map with confidence intervals |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | Linear Programming | Determination of flux ranges in optimal states | Minimum and maximum flux for each reaction |

| Elementary Flux Modes (EFM) | Convex Analysis | Identification of minimal functional pathways | Set of irreducible steady-state flux distributions |

| Comprehensive Polyhedra Enumeration (CoPE-FBA) | Polyhedral Geometry | Complete characterization of optimal flux spaces | Vertices, rays, and linealities of flux polyhedron |

Stoichiometric Inconsistency and Network Gaps

Stoichiometric inconsistencies represent a critical class of errors in metabolic models that can create network gaps and compromise predictive accuracy [3]. These inconsistencies arise when the stoichiometric constraints imply that one or more chemical species must have zero mass, indicating fundamental problems in network structure [3].

The primary types of stoichiometric inconsistencies include:

- Mass Balance Errors: Discrepancies between total mass of reactants and products in individual reactions [3]

- Moiety Balance Errors: Imbalances in chemical structures (e.g., phosphate groups) between reactants and products [3]

- Stoichiometric Inconsistencies: Structural errors where reaction network topology implies impossible mass relationships [3]

- Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycles (TICs): Cyclic reaction sets that could theoretically operate without energy input [6]

Detection and Resolution Methods

Algorithm 1: Moiety Balance Analysis Moiety analysis detects imbalances of chemical moieties using the same mathematical framework as atomic mass analysis but operates in units of moieties rather than individual atoms [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for detecting errors involving chemical groups with slightly different atomic formulas in different molecular contexts.

Algorithm 2: Graphical Analysis of Mass Equivalence Sets (GAMES) GAMES isolates stoichiometric inconsistencies by identifying small subsets of reactions and species (Reaction Isolation Set - RIS and Species Isolation Set - SIS) that explain structural errors [3]. This method simplifies error remediation by pinpointing the specific network elements requiring correction.

Structural Error Isolation Workflow

Advanced Topics and Research Directions

Gapfilling and Model Correction

Gapfilling is the process of identifying and resolving network gaps in metabolic reconstructions [6]. Current approaches use databases of biochemical functionalities to address gaps on a per-metabolite basis but often struggle with creating thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs) [6]. Advanced methods like OptFill perform holistic, TIC-avoiding whole-model gapfilling through optimization-based multi-step procedures [6].

The OptFill methodology involves:

- Identifying network gaps through connectivity analysis

- Proposing candidate reactions from biochemical databases

- Selecting minimal reaction sets that restore functionality

- Ensuring thermodynamic feasibility by avoiding TICs

- Validating added reactions against experimental data [6]

Standardization Challenges in Metabolic Models

A significant challenge in stoichiometric modeling, particularly for human metabolic networks, is the lack of standardization in reconstruction methods, representation formats, and model repositories [4]. This hinders direct comparison between models, selection of appropriate models for specific applications, and understanding of how metabolic network reconstructions evolve [4].

Standardization efforts focus on:

- Consistent annotation of genes, proteins, and reactions

- Uniform representation of compartmentalization

- Standardized formats for model exchange

- Benchmarks for model quality assessment [4]

Stoichiometric Modeling Pipeline

Table 3: Key Resources for Stoichiometric Modeling Research

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Package | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | MATLAB-based suite for FBA, MFA, and model validation [3] |

| MEMOTE | Software Tool | Model testing and validation | Automated quality assessment of genome-scale models [3] |

| OptFill | Gapfilling Algorithm | TIC-avoiding model completion | Holistic gapfilling of stoichiometric models [6] |

| BioModels | Model Repository | Curated model database | Source of validated biochemical models [3] |

| SBMLLint | Linting Tool | Structural error detection | Identification of mass balance and moiety errors [3] |

| CoPE-FBA | Analysis Method | Comprehensive flux space enumeration | Complete characterization of optimal FBA solutions [5] |

Stoichiometric modeling provides a powerful framework for analyzing metabolic networks based on fundamental mass balance principles. The accuracy of these models depends critically on avoiding stoichiometric inconsistencies, which can create network gaps and compromise predictive capability. Advanced methods for error detection, gapfilling, and solution space characterization continue to enhance the biological relevance and predictive power of stoichiometric models.

As the field advances, standardization of reconstruction methods, representation formats, and model repositories will be essential for enabling direct comparison between models and consistent integration of multi-omic data. These developments will further solidify the role of stoichiometric modeling as an indispensable tool in systems biology, metabolic engineering, and pharmaceutical research.

Stoichiometric inconsistency represents a fundamental error in the specification of biochemical reaction networks, violating the universal constraint that mass is conserved in every chemical transformation [3] [7]. In systems biology, particularly in stoichiometric modeling of metabolism, these inconsistencies arise when the total mass of atoms in the reactants does not equal the total mass of atoms in the products of a reaction [3]. This error violates the principle of conservation of mass, where molecular masses are always positive, and on each side of a reaction, mass must be conserved [7].

A single incorrectly defined reaction can lead to stoichiometric inconsistency throughout an entire model, resulting in unconserved metabolites [7]. These inconsistencies create profound problems in computational models, as they may give rise to thermodynamically infeasible cycles that either produce mass from nothing or consume mass from the model [7]. The presence of such errors undermines the predictive accuracy of metabolic models and can lead to biologically impossible predictions, such as the existence of metabolites with effectively zero mass [3].

The growing complexity of reaction-based models in systems biology necessitates early detection and resolution of these fundamental errors [3]. As biochemical networks in repositories like BioModels now range from tens to thousands of reactions, with over 800 curated models available, the correctness of these models is of particular concern since they often serve as starting points for new research [3]. Understanding and addressing stoichiometric inconsistencies is therefore essential for reliable metabolic modeling in biomedical research and drug development.

Fundamental Concepts and Biochemical Principles

Mass Balance vs. Moiety Balance

In biochemical modeling, two complementary concepts of balance must be considered:

Atomic Mass Balance: This fundamental approach compares the counts of individual atoms in reactants and products [3]. Implemented through Atomic Mass Analysis (AMA), it requires annotations of chemical species to obtain atomic formulas and looks for differences in atoms between reactants and products [3]. This method can check both charge balance and mass balance when atom ionization states are specified [3].

Moiety Balance: A moiety represents "a part or portion of a molecule, generally complex, having a characteristic chemical or pharmacological property" [3]. Unlike individual atoms, a single moiety may refer to groupings of atoms that have slightly different atomic formulas, such as the inorganic phosphate moiety found in ATP, ADP, and free Pi [3]. Moiety-preserving reactions are exceedingly common in biochemistry, particularly in transferase reactions that facilitate the transfer of chemical groups between molecules [3].

The critical distinction emerges when considering reactions like ATP hydrolysis, commonly written as ATP → ADP + Pi [3]. While this reaction is moiety balanced (one adenosine and three phosphates on both sides), it is not mass balanced due to differences in the atomic formulas of the inorganic phosphates in different molecular contexts [3]. To achieve mass balance, water must be included as a reactant, yet many modelers omit such "implicit molecules" whose concentrations remain relatively constant in solution [3].

Types of Structural Errors in Reaction Networks

Stoichiometric inconsistencies manifest through several specific structural errors in biochemical networks:

Mass Balance Errors: Discrepancies between the total mass of reactants and products [3]. These are detectable through AMA when complete atomic formulas are available [3].

Stoichiometric Inconsistency: A structural error implying that one or more chemical species have a mass of zero [3]. This type of error can propagate through networks, creating logical contradictions where a metabolite's mass must simultaneously be larger than itself [3].

Moiety Balance Errors: Imbalances of chemical structures between reactants and products that cannot be detected through atomic-level analysis alone [3]. These occur when reactions that should preserve moiety counts are incorrectly specified.

Table 1: Comparison of Balance Types in Biochemical Networks

| Balance Type | Analysis Method | Key Principle | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Mass Balance | Atomic Mass Analysis (AMA) | Conservation of individual atom counts | Complete combustion reactions; oxidation processes |

| Charge Balance | Atomic Mass Analysis with ionization states | Conservation of electrical charge | Ion transport; electron transfer chains |

| Moiety Balance | Moiety Analysis | Conservation of functional chemical groups | Phosphate transfer (kinases); methyl group transfer |

Detection Methodologies and Algorithms

Computational Frameworks for Consistency Checking

Multiple algorithmic approaches have been developed to detect stoichiometric inconsistencies in biochemical networks:

Stoichiometric Consistency Analysis: This test uses an implementation of the algorithm presented by Gevorgyan et al. (2008) to detect stoichiometric inconsistencies [7] [8]. The method identifies unconserved metabolites using the algorithm described in section 3.2 of the same publication [7]. In practical applications, this approach can reveal significant issues, with some models containing over 60% unconserved metabolites [8].

Moiety Analysis Algorithm: This approach adapts the same algorithmic framework as AMA but operates in units of moieties rather than atomic masses [3]. This enables detection of chemical structure imbalances that would be missed by atomic-level analysis alone [3].

Linear Programming Analysis: This method detects stoichiometric inconsistencies through optimization approaches that identify violations of mass conservation constraints [3].

The memote consistency test suite provides a comprehensive implementation of these methodologies, testing for stoichiometric consistency, unconserved metabolites, inconsistent minimal stoichiometries, and energy-generating cycles [7].

Error Isolation Techniques

Advanced methods have been developed not only to detect inconsistencies but to isolate their sources:

Graphical Analysis of Mass Equivalence Sets (GAMES): This algorithm provides isolation for stoichiometric inconsistencies by constructing explanations that relate errors in network structure to specific elements of the reaction network [3]. It identifies Reaction Isolation Sets (RIS) and Species Isolation Sets (SIS) that pinpoint the reactions and species causing errors [3].

Comprehensive Polyhedra Enumeration Flux Balance Analysis (CoPE-FBA): This approach characterizes the complete optimal flux space of stoichiometric models, revealing how a few subnetworks shape the geometry of optimal FBA solutions [5]. The method shows that typically only 5-10% of all reactions in a network determine the solution space [5].

The error isolation process involves identifying computationally simple explanations that show how the RIS and SIS cause the error, enabling researchers to efficiently remediate model errors [3].

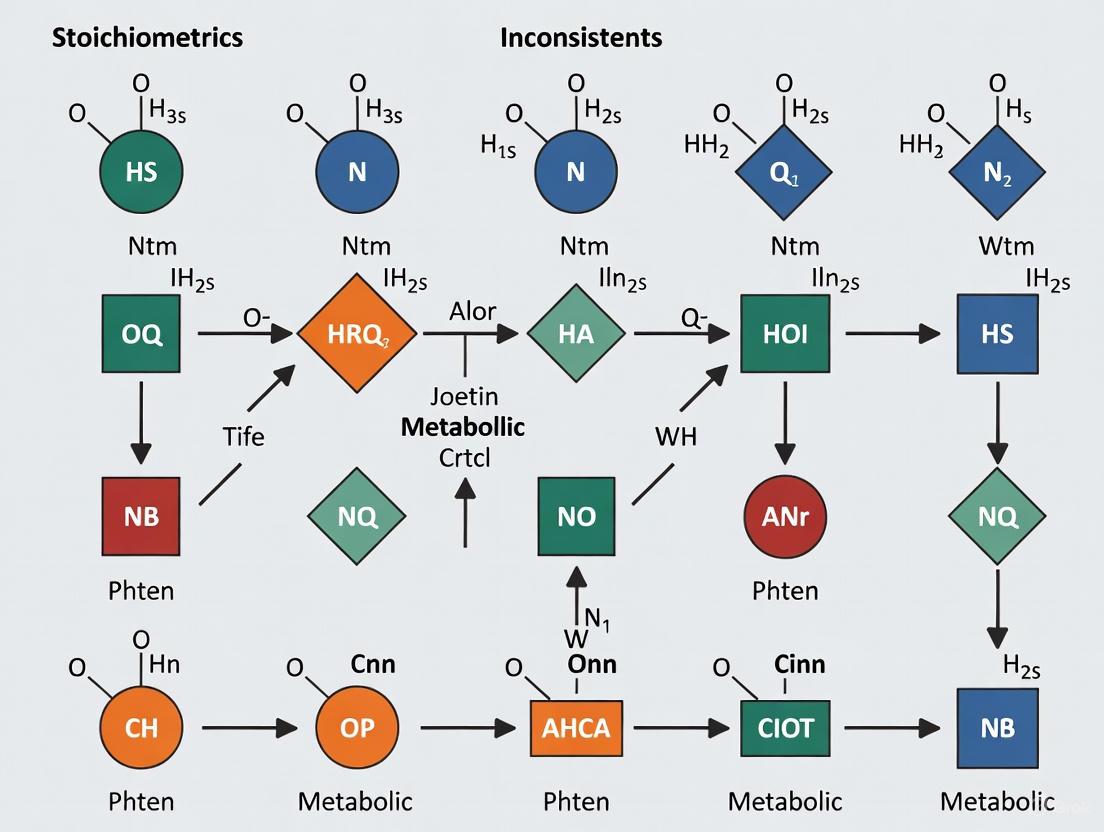

Diagram 1: Stoichiometric Consistency Checking Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process for detecting and isolating stoichiometric inconsistencies in biochemical models, incorporating multiple analysis methods and error isolation techniques.

Impact on Metabolic Network Analysis

Consequences for Metabolic Modeling

Stoichiometric inconsistencies create profound challenges for metabolic network analysis and prediction:

Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycles: Inconsistent models may give rise to cycles that either produce mass from nothing or consume mass from the model [7]. These include Energy Generating Cycles that provide reduced metabolites without requiring nutrient uptake, potentially increasing predicted growth rates by up to 25% in FBA, making growth predictions unreliable [7].

Blocked Reactions and Network Gaps: Universally blocked reactions cannot carry any flux when all model boundaries are open, typically caused by network gaps attributed to scope or knowledge limitations [7]. Orphan metabolites (only consumed) and dead-end metabolites (only produced) indicate structural network problems and knowledge gaps [7].

Flux Balance Analysis Limitations: Inconsistent models compromise FBA predictions, as the solution space becomes distorted by stoichiometric errors [5]. The presence of even a few inconsistent reactions can dramatically expand the feasible solution space with biologically impossible flux distributions.

Network-Wide Implications

The impact of stoichiometric inconsistencies extends throughout metabolic networks:

Solution Space Distortion: CoPE-FBA analysis demonstrates that optimal flux spaces of genome-scale stoichiometric models are determined by a few subnetworks [5]. When these subnetworks contain stoichiometric inconsistencies, the entire solution space becomes compromised.

Flux-Concentration Duality Breakdown: Under normal conditions, mathematical modeling of biochemical networks can be equivalently described in terms of either concentrations or unidirectional fluxes [9]. Stoichiometric inconsistencies disrupt this duality, preventing equivalent descriptions using these different perspectives.

Multi-omic Integration Challenges: Inconsistent metabolic models hinder integration with other biological data layers, such as transcriptomic and proteomic data, limiting their utility in systems biology approaches [4] [10].

Table 2: Common Structural Errors in Biochemical Networks and Their Impacts

| Error Type | Detection Method | Impact on Model Predictions | Remediation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unconserved Metabolites | Stoichiometric consistency test [7] | Mass can be created/destroyed; thermodynamic infeasibility | Add missing reactants/products; verify formulas |

| Energy Generating Cycles | Detect energy metabolite production from nothing [7] | Artificial ATP production; inflated growth predictions | Add thermodynamic constraints; verify reaction directions |

| Blocked Reactions | Flux Variability Analysis with open exchanges [7] | Limited network functionality; incomplete pathway coverage | Gap-filling algorithms; add missing transport reactions |

| Orphan Metabolites | Structural analysis of reaction equations [7] | Metabolites only consumed; accumulation impossible | Add producing reactions; verify compartmentalization |

| Dead-end Metabolites | Structural analysis of reaction equations [7] | Metabolites only produced; depletion impossible | Add consuming reactions; verify degradation pathways |

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Stoichiometric Consistency Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBMLLint [3] | Open-source linting for SBML models | Structural error detection in reaction networks | Moiety analysis; GAMES for error isolation; MIT license |

| MEMOTE [7] [8] | Test suite for stoichiometric consistency | Comprehensive model quality assessment | Implements Gevorgyan et al. algorithm; consistency scoring |

| COBRA Toolbox [3] | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | Genome-scale metabolic modeling | Atomic mass analysis with R-groups; charge balance checking |

| OptFill [6] | Optimization-based gapfilling | Holistic, infeasible cycle-free model completion | Avoids thermodynamically infeasible cycles during gapfilling |

| CoPE-FBA [5] | Comprehensive polyhedra enumeration | Complete characterization of optimal flux spaces | Identifies subnetworks determining solution space geometry |

Advanced Research Applications and Case Studies

Real-World Implications in Metabolic Research

The practical significance of stoichiometric consistency is evident across multiple research domains:

Stoichiometric Balance in Protein Networks: Research integrating protein copy numbers with interaction networks has established a Stoichiometric Balance Ratio (SBR) to quantify whether each protein in a network has abundance that is sub- or super-stoichiometric relative to global competition for binding [11]. This approach reveals how highly abundant proteins like clathrin are super-stoichiometric, while variations in both abundance and unique binding networks create widespread competition for shared binding sites [11].

Gene Expression Integration Challenges: Studies integrating gene expression profiles with metabolic pathways reveal substantial inconsistencies between expression data and anticipated network dynamics [10]. The Inconsistency Index (I) quantifies disagreement between expression data and network objectives, while Metabolic Coherence (MC) measures coordinated expression of connected reaction structures [10]. These measures show strong anticorrelation, demonstrating that inconsistencies between metabolic processes and gene expression can be understood from a network perspective [10].

Polymer Science Applications: Beyond metabolic networks, stoichiometric principles critically influence material properties in polymer science, where controlling functional group stoichiometry and crosslinking density determines reprocessability in covalent adaptable networks [12]. Precise stoichiometric design enables tuning of viscoelastic properties and mechanical behavior in polymer systems [12].

Protocol for Consistency Testing

The memote test suite provides a standardized protocol for stoichiometric consistency assessment:

Stoichiometric Consistency Test: Apply the algorithm from Gevorgyan et al. to verify overall model consistency [7].

Unconserved Metabolite Identification: Use the section 3.2 algorithm from the same paper to identify all unconserved metabolites [7].

Energy Generating Cycle Detection: Implement the Fritzemeier et al. algorithm to identify cycles that produce energy metabolites from nothing [7].

Charge and Mass Balance Verification: Check all non-boundary reactions for charge and mass balance, excluding reactions with missing formula or charge annotations [7].

Structural Network Analysis: Identify orphan metabolites, dead-ends, and disconnected metabolites through structural analysis of reaction equations [7].

Diagram 2: Model Consistency Assessment Protocol. This workflow outlines the standardized procedure for evaluating stoichiometric consistency in biochemical models, from data extraction through comprehensive testing and reporting.

Stoichiometric inconsistencies represent a critical challenge in biochemical network modeling, creating mass imbalance errors that propagate through computational models and compromise their predictive accuracy. These inconsistencies manifest as unconserved metabolites, energy-generating cycles, and stoichiometric contradictions that violate fundamental physical principles [3] [7].

Within the broader context of network gap research, stoichiometric inconsistencies create profound limitations by introducing structural errors that distort the feasible solution space of metabolic models [5]. These errors hinder the integration of multi-omic data layers [4] [10], compromise flux balance predictions [5], and create thermodynamic impossibilities that render models biologically implausible [7].

Advanced detection methodologies, including moiety analysis [3], GAMES for error isolation [3], and comprehensive consistency testing frameworks [7], provide researchers with powerful tools to identify and remediate these issues. The development of stoichiometric balance metrics across biological scales [11] and the application of stoichiometric principles in diverse fields [12] underscore the fundamental importance of mass conservation in predictive biological modeling.

As biochemical networks continue to increase in complexity and scope, maintaining stoichiometric consistency remains essential for developing accurate, predictive models that can reliably inform drug development, metabolic engineering, and biomedical research. The integration of robust consistency checking throughout the model development lifecycle represents a critical step toward realizing the full potential of systems biology in therapeutic applications.

Genome-scale Metabolic models (GEMs) are powerful computational tools that provide a mathematical representation of an organism's metabolism, mapping the complex network of biochemical reactions [13]. They are indispensable in advancing disciplines such as metabolic engineering, microbial ecology, and drug discovery. However, the presence of knowledge gaps—missing reactions due to incomplete genomic and functional annotations—represents a significant challenge to model accuracy and utility. These gaps often manifest as stoichiometric inconsistencies, disrupting the flow of metabolites through the network and creating "dead-end" metabolites that cannot be produced or consumed [13]. This article explores how these stoichiometric inconsistencies create network gaps and, consequently, how such gaps propagate through computational analyses to produce flux errors and potentially false biological insights, with a particular focus on implications for drug development and biomedical research.

Quantifying the Gap-Filling Performance of Computational Methods

The performance of different computational methods in addressing network gaps can be systematically evaluated. The following table summarizes the core abilities of various topology-based gap-filling methods, highlighting their distinct approaches and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Topology-Based Gap-Filling Methods for Metabolic Models

| Method Name | Core Methodology | Key Advantages | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHESHIRE (2023) [13] | Deep learning using Chebyshev spectral graph convolutional networks on metabolic hypergraphs. | Superior prediction accuracy; does not require phenotypic data for training; scalable to large reaction pools. | Performance may vary with network size and completeness. |

| Neural Hyperlink Predictor (NHP) [13] | Neural network that approximates hypergraphs using graphs for node feature generation. | Separates candidate reactions from training. | Loss of higher-order information due to graph approximation; less accurate than CHESHIRE. |

| C3MM [13] | Clique Closure-based Coordinated Matrix Minimization. | Integrated training-prediction process. | Limited scalability; model must be re-trained for each new reaction pool. |

| Marginal Distribution Sampling (MDS) [14] | Fills gaps using mean available values measured under similar meteorological conditions (primarily for EC data). | Standardized method used in FLUXNET and ICOS. | Systematically overestimates CO₂ emissions at northern sites (>60° latitude) due to skewed radiation distributions. |

Quantitative validation is critical for establishing the reliability of these methods. In an internal validation test designed to evaluate the ability to recover artificially removed reactions, CHESHIRE demonstrated superior performance. The test involved 108 BiGG models and 818 AGORA models, with reactions split into training and testing sets over 10 Monte Carlo runs [13].

Table 2: Internal Validation Performance on Artificial Gaps

| Performance Metric | CHESHIRE | NHP | C3MM | Node2Vec-Mean (NVM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Outperformed other methods [13] | Lower than CHESHIRE | Lower than CHESHIRE | Used as a baseline; lower than other methods |

| Key Differentiator | Exploits a sophisticated CSGCN and Frobenius norm-based pooling [13]. | Lacks higher-order information capture [13]. | Lacks scalability; requires re-training for new pools [13]. | Simple architecture without feature refinement [13]. |

Furthermore, an external validation assessed the impact of gap-filling on predicting metabolic phenotypes. Using 49 draft GEMs from CarveMe and ModelSEED pipelines, CHESHIRE improved the theoretical predictions of fermentation product and amino acid secretion [13]. This demonstrates that advanced gap-filling can directly enhance the functional utility of metabolic models.

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Internal Validation Protocol: Recovering Artificially Introduced Gaps

This protocol tests a method's ability to reconstruct a known, complete network by intentionally creating and then filling gaps [13].

- Input Preparation: Obtain a high-quality, curated GEM.

- Data Splitting: Split the metabolic reactions of the GEM into a training set (e.g., 80%) and a testing set (e.g., 20%). Perform this split over multiple (e.g., 10) Monte Carlo runs to ensure statistical robustness [13].

- Negative Sampling: Generate negative (non-existent) reactions for both training and testing sets at a 1:1 ratio to positive reactions. This is typically done by replacing half of the metabolites in a positive reaction with randomly selected metabolites from a universal metabolite pool [13].

- Model Training: Train the gap-filling method (e.g., CHESHIRE, NHP) using the combined set of positive and negative reactions in the training set.

- Performance Testing: Apply the trained model to the testing set mixed with its derived negative reactions. The model predicts a confidence score for each reaction in this test pool.

- Evaluation: Calculate performance metrics, such as Area Under the Curve (AUC), by comparing the model's predictions against the ground truth (i.e., which reactions were originally removed and which negative reactions are fake) [13].

External Validation Protocol: Predicting Metabolic Phenotypes

This protocol validates the method's real-world utility by testing its impact on the model's predictive functionality [13].

- Model Selection: Select a set of draft GEMs that have been reconstructed from genomic data using standard pipelines (e.g., CarveMe, ModelSEED).

- Gap-Filling: Apply the gap-filling method to these draft models, adding a set of candidate reactions predicted to be missing.

- Phenotypic Prediction: Use the original and the gap-filled models to simulate specific metabolic phenotypes (e.g., secretion of fermentation products, amino acid auxotrophy).

- Validation against Data: Compare the simulation results against known experimental data (e.g., from culture studies) for the organism.

- Evaluation: Quantify the improvement in prediction accuracy (e.g., increase in true positives, reduction in false negatives) in the gap-filled models compared to the original draft models [13].

Protocol for Assessing Carbon Balance Errors in Eddy Covariance Data

While not specific to GEMs, this protocol from flux measurement science exemplifies a robust validation workflow relevant to gap-filling in time-series data [14].

- Synthetic Data Generation: Create a synthetic, full time series of COâ‚‚ fluxes that corresponds to the observed fluxes at a site, ensuring a known "true" carbon balance [14].

- Introduction of Artificial Gaps: Introduce realistic artificial gaps (in both length and timing) into the synthetic data set. Common gap levels are 30%, 50%, and 70% of data [14].

- Gap-Filling: Apply the gap-filling methods (e.g., MDS, XGBoost) to the gapped synthetic data.

- Error Calculation: Calculate the annual carbon balance from the gap-filled time series. The balance error is determined as the difference between this estimated balance and the known true balance of the synthetic data [14].

Diagram 1: Internal Validation Workflow

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Databases for Metabolic Model Gap-Filling

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Gap-Filling |

|---|---|---|

| BiGG Models [13] | Knowledgebase | A repository of high-quality, curated GEMs; used as a gold-standard benchmark for testing and validating gap-filling methods. |

| AGORA Models [13] | Knowledgebase | A resource of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions for human gut microbes; provides a diverse set of models for validation. |

| CarveMe [13] | Software Tool | An automated pipeline for draft model reconstruction from genomic data; produces draft models that often require subsequent gap-filling. |

| ModelSEED [13] | Software Tool | A framework for the automated reconstruction and analysis of metabolic models; generates draft models that can be used for gap-filling validation. |

| REddyProc [14] | Software Tool | A tool for gap-filling eddy covariance data, implementing the MDS method; highlights domain-specific challenges in gap-filling. |

| Universal Metabolite Pool [13] | Data Resource | A comprehensive collection of known metabolites; used to generate plausible negative reactions during machine learning model training. |

| XGBoost [14] | Software Library | A machine learning library implementing gradient boosting; used as an advanced alternative to MDS for flux data gap-filling. |

Consequences of Inadequate Gap-Filling: From Bias to False Insights

Inadequate gap-filling methods can introduce systematic biases that compromise the validity of model predictions. A critical example comes from the field of eddy covariance, where the widely used Marginal Distribution Sampling (MDS) method has been shown to create significant carbon balance errors for northern sites (latitude >60°) [14]. The underlying cause is a skewed radiation distribution at high latitudes. During gap-filling, MDS samples more data from the lower range of the radiation distribution, which corresponds to underestimated photosynthetic uptake. This leads to a systematic overestimation of COâ‚‚ emissions from carbon sources and an underestimation of COâ‚‚ sequestration by carbon sinks [14]. The median balance error with MDS can range from 2–10 g C mâ»Â² yâ»Â¹ at a 30% gap level to 3–17 g C mâ»Â² yâ»Â¹ at a 70% gap level, with some errors exceeding 30 g C mâ»Â² yâ»Â¹ [14]. This demonstrates how a widely trusted method can produce predictable, directional errors under specific conditions.

In metabolic model analysis, gaps caused by stoichiometric inconsistencies prevent models from simulating known metabolic functions, leading to false-negative predictions. For instance, a draft model might incorrectly predict that an organism cannot synthesize an essential amino acid or produce a key fermentation product due to a missing reaction in an otherwise complete pathway [13]. Conversely, an inappropriate gap-filling technique might introduce reactions that create thermodynamically infeasible loops or bypass key regulatory steps, allowing the model to produce a metabolite without the necessary biochemical constraints and potentially leading to false-positive predictions. These inaccuracies can directly impact drug discovery efforts. For example, targeting an enzyme that is part of a pathway predicted to be essential in a pathogen—when in reality the pathway is non-functional or can be bypassed due to model gaps—could lead to failed therapeutic strategies. Thus, robust gap-filling is not merely a technical exercise but a critical step in ensuring the biological relevance and predictive power of in-silico models.

Diagram 2: Impact of Network Gaps on Predictions

The impact of gaps on model predictions is profound and far-reaching, leading to everything from quantifiable flux errors to fundamentally flawed biological insights. Stoichiometric inconsistencies create network gaps that disrupt the biochemical logic of metabolic models, while inadequate gap-filling methods can introduce systematic biases, as evidenced by the performance of MDS in environmental flux data and the limitations of early machine learning methods for GEMs. The development of advanced, topology-based methods like CHESHIRE, which leverage deep learning on hypergraph representations of metabolism, offers a promising path forward. By providing more accurate and scalable gap-filling, these tools can significantly improve the predictive fidelity of models. For researchers in drug development and biomedical science, relying on models refined by such robust methods is becoming increasingly critical to generate reliable hypotheses, identify valid therapeutic targets, and avoid the costly dead ends that stem from false biological insights.

Stoichiometric inconsistency in chemical and biological networks creates critical knowledge gaps that hinder the prediction of synthesizable materials and the understanding of metabolic processes. This whitepaper explores how imbalances in elemental composition disrupt network connectivity and functionality. We examine advanced computational methods, including machine learning and hypergraph-based approaches, that identify and rectify these stoichiometric gaps. By integrating data from materials science and metabolic network analysis, this guide provides researchers with robust protocols for predicting synthesizability and filling network gaps, ultimately accelerating discovery in drug development and materials design.

In both inorganic materials science and cellular biochemistry, the balanced representation of elemental composition—stoichiometry—is fundamental for predicting stable compounds and viable metabolic pathways. Stoichiometric inconsistency refers to imbalances in elemental representation that lead to network gaps, disrupting the connectivity and functionality of chemical reaction networks (CRNs) and genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). These gaps manifest as dead-end metabolites that cannot be produced or consumed, or as computationally predicted compounds that are experimentally unsynthesizable [15] [16].

The challenge extends beyond simple atomic mass balance to the identification of chemically plausible linkages between moieties. In metabolic engineering, incomplete genomic and functional annotations result in GEMs with missing reactions, creating unrealistic metabolic predictions [16]. Similarly, in materials science, the majority of candidate materials identified through high-performance computing are impractical to synthesize due to intricate synthesis constraints [15]. Understanding and resolving these stoichiometric inconsistencies is therefore critical for advancing predictive capabilities in both fields.

Computational Frameworks for Gap Analysis and Prediction

Machine Learning for Synthesizability Prediction

Positive-unlabeled learning represents a powerful machine learning approach for predicting the synthesizability of inorganic material stoichiometries. This method addresses the challenge where only positive (synthesizable) examples are definitively known, while unsynthesizable compounds remain unlabeled.

Experimental Protocol for Synthesizability Prediction:

- Data Collection: Compile a database of known synthesizable inorganic compositions from crystallographic databases.

- Feature Initialization: Encode each elemental stoichiometry using compositional descriptors and structural features.

- Model Training: Apply positive-unlabeled learning algorithms where known synthesizable compositions serve as positive examples, while random stoichiometries from chemical space serve as unlabeled examples.

- Validation: Assess model performance using recall and precision metrics against held-out test sets of known materials.

- Experimental Guidance: Use model predictions with high confidence scores to guide exploration of new compositional spaces, such as the discovery of the new quaternary oxide phase Cuâ‚„FeV₃Oâ‚₃ [15].

This approach has demonstrated a true positive rate of 83.4% and an estimated precision of 83.6% on test datasets, enabling the construction of continuous synthesizability phase maps that agree with available synthetic data [15].

Hypergraph Learning for Metabolic Network Gap-Filling

Metabolic networks naturally form hypergraphs where reactions (hyperedges) connect multiple metabolite nodes simultaneously. The CHESHIRE (CHEbyshev Spectral HyperlInk pREdictor) method uses deep learning on hypergraph representations of GEMs to predict missing reactions purely from network topology, without requiring experimental phenotypic data [16].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Topology-Based Gap-Filling Methods

| Method | Architecture | AUROC (Mean) | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHESHIRE | Chebyshev Spectral Graph Convolutional Network | 0.92 | Hypergraph learning with feature refinement |

| NHP | Graph-based approximation of hypergraphs | 0.85 | Neural network with mean pooling |

| C3MM | Clique Closure-based Matrix Minimization | 0.79 | Integrated training-prediction process |

| Node2Vec-mean | Random walk graph embedding | 0.74 | Simple baseline with mean pooling |

Experimental Protocol for CHESHIRE:

- Network Representation: Convert the metabolic network into a hypergraph where each reaction is a hyperlink connecting all participating metabolites.

- Feature Initialization: Generate initial feature vectors for each metabolite from the hypergraph incidence matrix using an encoder-based neural network.

- Feature Refinement: Apply Chebyshev Spectral Graph Convolutional Network (CSGCN) on a decomposed graph to refine metabolite features by incorporating information from connected metabolites.

- Pooling and Scoring: Use maximum minimum-based and Frobenius norm-based pooling functions to integrate metabolite features into reaction-level representations, then score reaction existence probability.

- Internal Validation: Test the method by artificially removing reactions from high-quality GEMs (e.g., 108 BiGG models) and measuring recovery accuracy.

- External Validation: Assess improved prediction of metabolic phenotypes (e.g., fermentation products, amino acid secretion) in 49 draft GEMs [16].

CHESHIRE's architecture enables it to outperform other topology-based methods in recovering artificially removed reactions and improves phenotypic predictions for draft metabolic models [16].

Visualization of Chemical Space and Reaction Networks

Chemical Space Networks (CSNs)

Chemical Space Networks provide powerful visualizations for exploring relationships between chemical moieties. In CSNs, compounds are represented as nodes connected by edges defined by pairwise relationships such as 2D fingerprint Tanimoto similarity or maximum common substructure similarity [17].

Experimental Protocol for CSN Creation:

- Data Curation: Load compound datasets (e.g., from ChEMBL), remove salts, check for disconnected structures using

GetMolFrags, and merge duplicate compounds by averaging activity values [17]. - Fingerprint Calculation: Generate RDKit 2D fingerprints for all compounds to encode molecular structure.

- Similarity Matrix Computation: Calculate all pairwise Tanimoto similarity coefficients between compounds.

- Network Construction: Apply a similarity threshold (e.g., 0.7) to create edges between sufficiently similar compounds.

- Visualization and Analysis: Create network visualizations using NetworkX or D3.js, implementing node coloring based on properties, and calculate network metrics including clustering coefficient and modularity [17].

Web-Based Tools for Reaction Network Analysis

Web-based graphical user interfaces, such as the Catalyst Acquisition by Data Science (CADS) platform, make network analysis accessible to researchers without programming expertise. These tools enable uploading of CSV data containing source and target nodes to generate CRN visualizations [18].

Key analytical functions include:

- Centrality Analysis: Identification of key intermediates using metrics including degree, betweenness, and closeness centrality.

- Shortest Path Search: Adaptation of Dijkstra's algorithm to find efficient routes between reactants and products.

- Clustering Algorithms: Application of Greedy, Louvain, and Girvan-Newman methods to identify network communities.

- Interactive Visualization: Features including zoom, node highlighting, and tooltips for exploring complex networks [18].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Exploring Chemical Moieties

| Item | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Compute molecular fingerprints, canonicalize SMILES, calculate molecular descriptors [17] |

| NetworkX | Python package for network analysis | Create and analyze complex networks, calculate centrality metrics, perform clustering [17] [18] |

| D3.js | JavaScript library for network visualization | Create interactive, force-directed network layouts in web interfaces [18] |

| CADS Platform | Web-based GUI for reaction network analysis | Upload CSV data, perform centrality calculations and clustering without programming [18] |

| CHESHIRE Algorithm | Hyperlink prediction for metabolic networks | Predict missing reactions in GEMs using topological features [16] |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning Model | Synthesizability prediction | Predict likelihood of synthesizing inorganic materials from stoichiometry [15] |

The exploration of chemical moieties beyond simple atomic mass balance requires integrated approaches that address stoichiometric inconsistencies across multiple domains. Computational methods including machine learning for synthesizability prediction and hypergraph learning for metabolic network gap-filling provide powerful frameworks for identifying and resolving these network gaps. Visualization techniques such as Chemical Space Networks and web-based analysis platforms enable intuitive exploration of complex chemical relationships. As these methodologies continue to mature, they hold immense potential for accelerating the discovery of synthesizable materials and elucidating complete metabolic pathways, ultimately bridging the critical gap between computational prediction and experimental reality in pharmaceutical development and materials science.

Bridging the Gaps: Computational Methods for Detection and Resolution

In systems biology, genome-scale metabolic reconstructions serve as structured knowledge bases that mathematically represent biochemical, physiological, and genomic information of target organisms [19]. These network models enable researchers to predict phenotypic behaviors, identify drug targets, and optimize biotechnological processes through computational simulations. However, incomplete knowledge and incorrect stoichiometric assumptions frequently create "gaps" that hinder model functionality, particularly the ability to produce biomass precursors or essential metabolites. Gap-filling methodologies have emerged as essential computational approaches to address these limitations by algorithmically identifying missing metabolic functions using universal biochemical reaction databases.

The foundational challenge driving gap-filling development stems from the inherent incompleteness of genome annotations and biochemical characterizations. As Thiele and Palsson noted, comprehensive metabolic network reconstructions summarize existing knowledge while simultaneously highlighting missing information through computational analysis [19]. When stoichiometric inconsistencies exist within these networks—whether through incorrect mass balances, infeasible metabolic cycles, or thermodynamically impossible reactions—they create functional gaps that prevent accurate physiological simulations. This review examines the algorithmic foundations of modern gap-filling methodologies, with particular emphasis on how stoichiometric inconsistency creates and perpetuates network gaps while presenting computational strategies for their resolution.

Stoichiometric Inconsistency: Origins and Implications for Network Gaps

Fundamental Stoichiometric Principles

Stoichiometry forms the mathematical backbone of metabolic network analysis, representing the quantitative relationships between reactants and products in biochemical transformations. In flux balance analysis (FBA), metabolic reactions are represented as a stoichiometric matrix (S), where rows correspond to metabolites and columns represent reactions [20]. The entries in each column are stoichiometric coefficients indicating the quantity of each metabolite consumed (negative coefficient) or produced (positive coefficient) in a reaction. At steady state, the system follows the mass balance equation Sv = 0, where v is the flux vector of reaction rates [20]. This equation imposes critical constraints ensuring that total metabolite production equals consumption, embodying the principle of mass conservation.

How Stoichiometric Inconsistencies Create Network Gaps

Stoichiometric inconsistencies arise when reaction equations violate mass conservation principles, creating fundamental flaws in metabolic network models. As Gevorgyan et al. identified, many biochemical databases contain reactions with stoichiometries inconsistent with conservation of mass [19]. A simple example would be the reactions A ⇌ B and A ⇌ B + C, where no positive molecular masses can be assigned to A, B, and C such that mass balances on both sides of both reactions are equal [19]. Such inconsistencies create network gaps by:

- Blocking metabolic pathways: Inconsistent stoichiometries prevent flux through connected pathways, creating "dead-end" metabolites that can be produced but not consumed, or vice versa.

- Disrupting thermodynamic feasibility: Mass conservation violations make meaningful thermodynamic analysis impossible, as energy calculations depend on balanced chemical equations.

- Generating infeasible cycles: Stoichiometric errors can create cyclic reaction patterns that generate energy without substrate input, violating thermodynamic principles.

The impact of correct stoichiometric assumptions extends beyond microbial models to biomedical applications. Recent work on monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) demonstrates that incorrect stoichiometric assumptions—specifically, modeling bivalent antibodies with 1-to-1 binding instead of correct 2-to-1 binding—can significantly distort pharmacokinetic predictions [21]. For soluble targets when the elimination rate of drug-target complexes is comparable to or lower than the drug elimination rate, the incorrect model cannot adequately describe data generated from proper stoichiometric assumptions [21].

Table 1: Types of Stoichiometric Inconsistencies and Their Impacts

| Inconsistency Type | Mathematical Representation | Network Impact | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Imbalance | A ⇌ B + C (when A has lower molecular mass than B + C) | Dead-end metabolites, blocked pathways | Hypothetical: A (100 Da) → B (60 Da) + C (60 Da) |

| Elemental Imbalance | Reaction violates conservation of key elements (C, N, O, P) | Thermodynamic infeasibility | CO₂ → CH₄ (violating oxygen balance) |

| Charge Imbalance | Total charge of reactants ≠total charge of products | Electrochemical gradient errors | ATPâ´â» + Hâ‚‚O → ADP³⻠+ PO₃⻠(charge imbalance) |

| Infeasible Cycle | Closed loop of reactions that generates energy without input | Thermodynamically impossible flux distributions | Coupled reactions producing ATP without substrate consumption |

Algorithmic Approaches to Gap-Filling

Core Mathematical Frameworks

Gap-filling algorithms primarily employ two mathematical optimization frameworks: Linear Programming (LP) and Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP). Both approaches build upon the fundamental constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) paradigm, which uses stoichiometric constraints, flux boundaries, and biological objective functions to identify feasible metabolic states [20].

The Flux Balance Analysis foundation for gap-filling can be mathematically represented as:

- Objective: Maximize/Minimize Z = cáµ€v

- Constraints: Sv = 0 (Mass balance)

- Bounds: α ≤ v ≤ b (Flux capacity constraints)

Where c is a vector of weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the biological objective, typically growth or ATP production [20].

Prominent Gap-Filling Algorithms

fastGapFill: Efficient Scalable Gap-Filling

The fastGapFill algorithm represents a computationally efficient approach specifically designed for compartmentalized genome-scale models [19]. It extends the fastcore algorithm to identify candidate missing knowledge from universal biochemical databases like KEGG. Key innovations include:

- Preprocessing for dimensionality reduction: Creates a global model by expanding the cellular compartmentalized model with a universal metabolic database placed in each compartment

- Tractable computation: Uses a modified fastcore approach with linear weightings to prioritize addition of specific reaction types

- Stoichiometric consistency checking: Incorporates scalable methods to identify stoichiometrically inconsistent reactions from gap-filling solutions

In benchmark tests across five metabolic models, fastGapFill demonstrated impressive scalability, processing models ranging from Thermotoga maritima (418 metabolites × 535 reactions) to Recon 2 (3187 metabolites × 5837 reactions) with computation times from seconds to approximately 30 minutes [19].

FastGapFilling: Linear Programming-Based Efficiency

FastGapFilling (distinct from fastGapFill) employs an LP-only approach to avoid computationally expensive MILP formulations [22]. The algorithm:

- Includes all candidate reactions alongside actual model reactions

- Uses an objective function that maximizes biomass flux (multiplied by a weight) while minimizing the sum of candidate reaction fluxes (multiplied by user-defined weights)

- Performs a binary search on the biomass reaction weight to find small reaction sets that enable growth

This approach achieved up to three orders of magnitude speed improvement compared to MILP-based methods while generating biologically plausible solutions [22].

OptFill: Holistic Infeasible Cycle-Free Gapfilling

OptFill introduces an optimization-based multi-step method that performs thermodynamically infeasible cycle (TIC)-avoiding whole-model gapfilling [6]. Unlike approaches that address gaps on a per-metabolite basis, OptFill provides holistic solutions while avoiding thermodynamically infeasible cycles that typically require extensive manual curation. When applied to the iJR904 E. coli model, OptFill generated biologically feasible, cycle-free gapfilling solutions [6].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Gap-Filling Algorithms

| Algorithm | Mathematical Approach | Key Features | Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fastGapFill [19] | LP with preprocessing | Compartmentalization support, stoichiometric consistency checking | 21-1826 seconds for benchmark models | May not find global optimum |

| FastGapFilling [22] | LP with binary search | No integer variables, rapid execution | 3 orders of magnitude faster than MILP in some cases | Does not guarantee minimal set |

| MILP Standard [23] | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming | Guarantees minimal reaction addition | Computationally intensive (hours-days) | Intractable for large candidate sets |

| OptFill [6] | Multi-step optimization | Avoids thermodynamically infeasible cycles | Validated on iJR904 E. coli model | Complex implementation |

| ModelSEED [23] | MILP with thermodynamic weights | Incorporates thermodynamic penalties, database of ~13,000 reactions | Production-quality for genome annotation | Requires extensive biochemical databases |

Workflow Visualization: FastGapFill Algorithm

Graph 1: FastGapFill algorithm workflow for metabolic network completion

Workflow Visualization: General Gap-Filling Process

Graph 2: Generalized gap-filling workflow for metabolic models

Implementation and Experimental Considerations

Computational Tools and Platforms

Multiple software platforms implement gap-filling algorithms for practical applications:

- COBRA Toolbox: MATLAB-based toolbox that includes fastGapFill implementation for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis [19] [20]

- Pathway Tools/MetaFlux: Includes FastGapFilling algorithm as part of its metabolic modeling capabilities [22]

- KBase Gapfill Metabolic Model: Web-based implementation using ModelSEED database with ~13,000 biochemical reactions [23]

- OptFill: Advanced implementation focusing on thermodynamically feasible solutions [6]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Resources for Metabolic Gap-Filling Research

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in Gap-Filling | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, ModelSEED, BiGG | Universal reaction sets for candidate solutions | Public/partially restricted |

| Stoichiometric Consistency Tools | fastGapFill consistency module | Identify mass-imbalanced reactions | COBRA Toolbox |

| Metabolic Modeling Platforms | COBRA Toolbox, Pathway Tools, KBase | Implement gap-filling algorithms | Open source/commercial |

| Thermodynamic Calculators | Group contribution methods, eQuilibrator | Estimate reaction directionality & feasibility | Public web interfaces |

| Standardized Model Repositories | BioModels, JSON Model Repository | Validate against curated models | Public access |

| 8-Br-GTP | 8-Br-GTP, MF:C10H15BrN5O14P3, MW:602.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Dot1L-IN-5 | Dot1L-IN-5, MF:C23H19ClF2N8O5S, MW:593.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Protocol: FastGapFill Implementation

Objective: Identify minimal reaction set to enable metabolic network growth under defined conditions.

Preprocessing Requirements:

- Stoichiometric matrix (S) of the metabolic reconstruction

- List of blocked reactions (B) identified through flux variability analysis

- Universal reaction database (U) such as KEGG or MetaCyc

- Compartmentalization scheme for eukaryotic models

Methodology:

- Generate Global Model:

- Expand model (S) with universal database (U) placed in each cellular compartment

- Add transport reactions (X) for non-cytosolic metabolites

- Include exchange reactions for extracellular metabolites

- Result: Global model SUX containing all flux-consistent reactions

Define Core Set:

- Combine original model reactions (S) with solvable blocked reactions (Bs)

- This forms the core reaction set for network expansion

Apply Modified Fastcore:

- Use L1-norm regularized linear programs to approximate cardinality function

- Greedily expand core set while minimizing added reactions from UX

- Apply linear weightings to prioritize biochemically preferred reactions

Validate Stoichiometric Consistency:

- Apply scalable approach for approximate cardinality maximization

- Compute maximal metabolite set involved in mass-conserving reactions

- Flag inconsistent candidate reactions [19]

Validation:

- Test gap-filled model for growth under target conditions

- Verify production of all biomass precursors

- Check for absence of thermodynamically infeasible cycles

Applications and Future Directions

Biomedical and Biotechnological Applications

Gap-filling methodologies have moved beyond theoretical exercises to practical applications in drug discovery, metabolic engineering, and biomedical research. The reconstruction of tissue-specific metabolic models—particularly human models—enables researchers to study metabolic aspects of diseases and identify potential drug targets [4]. For instance, gap-filled models of cancer metabolism have identified nutrient dependencies and potential therapeutic interventions.

In pharmaceutical development, correct stoichiometric assumptions are proving critical for accurate modeling of therapeutic agents. Recent work on monoclonal antibodies demonstrates that proper accounting for bivalent binding (2:1 antibody:antigen stoichiometry) is essential for accurate pharmacokinetic modeling, particularly for soluble targets [21]. The traditional 1:1 binding model cannot adequately describe data generated from proper stoichiometric assumptions under certain elimination conditions [21].

Emerging Challenges and Research Frontiers

Despite significant advances, gap-filling methodologies face ongoing challenges:

- Standardization: Different model repositories use varying formats, reconstruction methods, and annotation standards, complicating direct comparison and integration [4]

- Tissue-specific modeling: Reconstruction of compartmentalized eukaryotic models presents unique challenges in transport reaction identification and reaction reversibility assignment [4]

- Multi-omic integration: Incorporating transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data into gap-filling processes remains computationally challenging

- Thermodynamic feasibility: Ensuring gap-filled solutions respect energy conservation and thermodynamic principles requires sophisticated constraint formulation [6]

Future algorithmic development will likely focus on machine learning approaches to prioritize biologically relevant reactions, multi-tissue modeling for complex organisms, and dynamic gap-filling that incorporates regulatory information. As genomic annotations continue to improve, gap-filling will evolve from filling knowledge gaps to reconciling network models with experimental data, maintaining its critical role in metabolic network reconstruction and analysis.

fastGapFill represents a computationally efficient algorithm for identifying candidate missing reactions in genome-scale metabolic reconstructions. This method addresses a fundamental challenge in metabolic network analysis: the presence of network gaps arising from stoichiometric inconsistencies and incomplete biochemical knowledge. By extending the fastcore algorithm, fastGapFill enables scalable gap-filling of compartmentalized models through a series of L1-norm regularized linear programs that approximate cardinality minimization. The algorithm successfully integrates three critical aspects of model consistency—gap-filling, flux consistency, and stoichiometric consistency—within a unified framework, demonstrating practical utility across diverse organisms from Thermotoga maritima to human metabolic reconstruction Recon 2.

The fidelity of genome-scale metabolic models hinges on biochemical accuracy and comprehensiveness. Stoichiometric inconsistencies represent a primary source of network gaps, occurring when reaction stoichiometry violates mass conservation principles. For example, the reactions ( A \rightleftharpoons B ) and ( A \rightleftharpoons B + C ) are stoichiometrically inconsistent, as no positive molecular mass assignment can satisfy mass balance for both reactions simultaneously [19]. Such inconsistencies create dead-end metabolites and blocked reactions that disrupt flux flow, ultimately limiting model predictive capability.

fastGapFill addresses these challenges by providing the first scalable approach capable of efficiently handling compartmentalized genome-scale models without requiring decompartmentalization—a process that traditionally underestimated missing information by connecting reactions that normally wouldn't co-occur in the same cellular compartment [19].

Core Algorithmic Framework and Methodology

Mathematical Formulation

The fastGapFill algorithm repurposes the fastcore algorithm to compute a near-minimal set of reactions that must be added to an input metabolic model ( M ) to render it flux consistent. The algorithm takes as input model ( M ) and a core set of reactions ( C \subset M ), then greedily expands ( C ) by computing a set of modes of ( M ) whose overall support contains the entirety of ( C ) plus a minimal set from ( M \setminus C ) [19].

Preprocessing generates a global model where a cellularly compartmentalized metabolic model ( S ) without blocked reactions ( B ) is expanded by a universal metabolic database ( U ). A copy of ( U ) is placed in each cellular compartment of ( S ), and for each metabolite occurring in a non-cytosolic compartment, reversible intercompartmental transport reactions are added. For extracellular metabolites, exchange reactions are added, generating an extended global model ( SUX ) where all reactions become flux consistent [19].

The core optimization identifies a minimal set of gap-filling reactions by solving: [ \begin{aligned} & \underset{v}{\text{minimize}} & & \Vert w \circ v \Vert1 \ & \text{subject to} & & S \cdot v = 0 \ & & & v{\text{core}} \geq \epsilon \ & & & v_i \geq 0 \ \forall i \in \text{irreversible reactions} \end{aligned} ] where ( w ) represents a weighting vector that prioritizes certain reaction types, ( S ) is the stoichiometric matrix, and ( \epsilon ) is a small positive constant [19] [24].

Workflow and Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive fastGapFill workflow, from initial model preparation through to the identification and validation of gap-filling solutions:

Table: fastGapFill Function Components

| Function | Purpose | Key Inputs | Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

prepareFastGapFill |

Generate input for gap-filling | Model, compartment list, universal DB | Consistent model, SUX matrices, blocked reactions [24] |

fastGapFill |

Core gap-filling algorithm | consistMatricesSUX, epsilon, weights | AddedRxns [24] |

identifyBlockedRxns |

Detect flux-inconsistent reactions | Model, epsilon | consistModel, BlockedRxns [24] |

postProcessGapFillSolutions |

Analyze and interpret results | AddedRxns, model, BlockedRxns | AddedRxnsExtended with statistics [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Performance Benchmarking

fastGapFill was validated against five metabolic models of varying complexity and compartmentalization. The algorithm demonstrated scalable performance across models ranging from Thermotoga maritima (2 compartments) to Recon 2 (8 compartments), successfully filling hundreds of metabolic gaps with practical computation times [19].

Table: fastGapFill Performance Across Metabolic Models

| Model | Compartments | Original Reactions | Blocked Reactions (B) | Solvable Blocked (Bs) | Gap-Filling Reactions Added | fastGapFill Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. maritima | 2 | 535 | 116 | 84 | 87 | 21 |

| E. coli | 3 | 2,232 | 196 | 159 | 138 | 238 |

| Synechocystis sp. | 4 | 731 | 132 | 100 | 172 | 435 |

| sIEC | 7 | 1,260 | 22 | 17 | 14 | 194 |

| Recon 2 | 8 | 5,837 | 1,603 | 490 | 400 | 1,826 |

Advanced Applications: Community Gap-Filling

The core fastGapFill approach has been extended to microbial communities, enabling gap-filling while considering metabolic interactions between species. This community gap-filling method was validated using a synthetic community of two auxotrophic Escherichia coli strains, successfully restoring growth and predicting acetate cross-feeding interactions. The algorithm further demonstrated utility in analyzing human gut microbiota, resolving metabolic gaps in communities of Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii while identifying potential metabolic cross-feeding mechanisms [25] [26].

The community approach addresses a critical limitation of individual model gap-filling: microorganisms from complex communities often cannot be easily cultivated individually, making experimental validation and individual model curation challenging. By permitting metabolic interaction during gap-filling, this method enables more biologically realistic completion of metabolic networks [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Critical Components for fastGapFill Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Model | Base metabolic reconstruction | Model structure with reactions, metabolites, stoichiometry [19] |

| Universal Reaction Database | Source of candidate reactions | KEGG, MetaCyc, ModelSEED, BiGG [19] [25] |

| Compartment Mapping | Handle multi-compartment models | Define intracellular compartments and transport reactions [19] |

| Linear Programming Solver | Optimization core | COBRA Toolbox compatibility with LP solvers [19] [24] |

| Weighting Scheme | Prioritize reaction addition | weights.MetabolicRxns = 10, weights.TransportRxns = 10 [24] |

| Crisugabalin | Crisugabalin | Crisugabalin (HSK16149) is a potent, selective GABA analog for neuropathic pain research. This product is for research use only (RUO), not for human consumption. |

| N-Methyl Duloxetine hydrochloride | N-Methyl Duloxetine hydrochloride, MF:C19H22ClNOS, MW:347.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Evolution Beyond FastGapFill: Machine Learning Approaches

While fastGapFill remains a foundational constraint-based method, recent advances have introduced machine learning approaches that predict missing reactions purely from metabolic network topology, requiring no experimental data. CHESHIRE (CHEbyshev Spectral HyperlInk pREdictor) utilizes deep learning on hypergraph representations of metabolic networks, where metabolites represent nodes and reactions represent hyperlinks [16].

This approach demonstrates particular value for non-model organisms where experimental data may be scarce. CHESHIRE outperformed existing topology-based methods in recovering artificially removed reactions across 926 metabolic models and improved phenotypic predictions for 49 draft GEMs [16]. Further innovations like Multi-HGNN incorporate multi-modal data, including biochemical features of metabolites and metabolic directionality, achieving state-of-the-art performance in missing reaction prediction [27].

fastGapFill provides an efficient, scalable solution to the critical bioinformatics challenge of identifying candidate missing reactions in metabolic networks. By addressing stoichiometric inconsistencies through a computationally tractable framework, it enables more accurate metabolic reconstruction and predictive modeling. The algorithm's extensibility to microbial communities and compatibility with emerging machine learning approaches ensures its continued relevance in metabolic network analysis. As genomic data continues to expand, efficient gap-filling methodologies remain essential for translating sequence information into functional metabolic insights with applications across biotechnology, medicine, and microbial ecology.

In the field of systems biology and metabolic engineering, stoichiometric inconsistency presents a fundamental challenge in the development of high-quality genome-scale metabolic models (GSMs). These inconsistencies arise when the stoichiometry of biochemical reactions violates the principle of mass conservation, creating network gaps that disrupt flux balance analysis and hamper predictive accuracy [6] [19]. Unlike simple missing reactions, stoichiometric inconsistencies create thermodynamically infeasible pathways that can generate computational artifacts, including Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycles (TICs)—pathways that can generate energy without substrate input—which significantly compromise model validity [6].

The presence of these gaps and inconsistencies necessitates advanced error isolation techniques. Methods like GAMES (Gap-filling Analysis for Metabolic Model Enhancement and Stoichiometry) have emerged as sophisticated computational approaches designed to systematically identify and rectify these issues, enabling researchers to develop more biologically accurate metabolic reconstructions for applications ranging from biotechnology to drug development [6] [19].

Core Principles: Stoichiometric Consistency and Network Gaps

Fundamental Concepts