Stoichiometric vs. Kinetic Metabolic Modeling: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

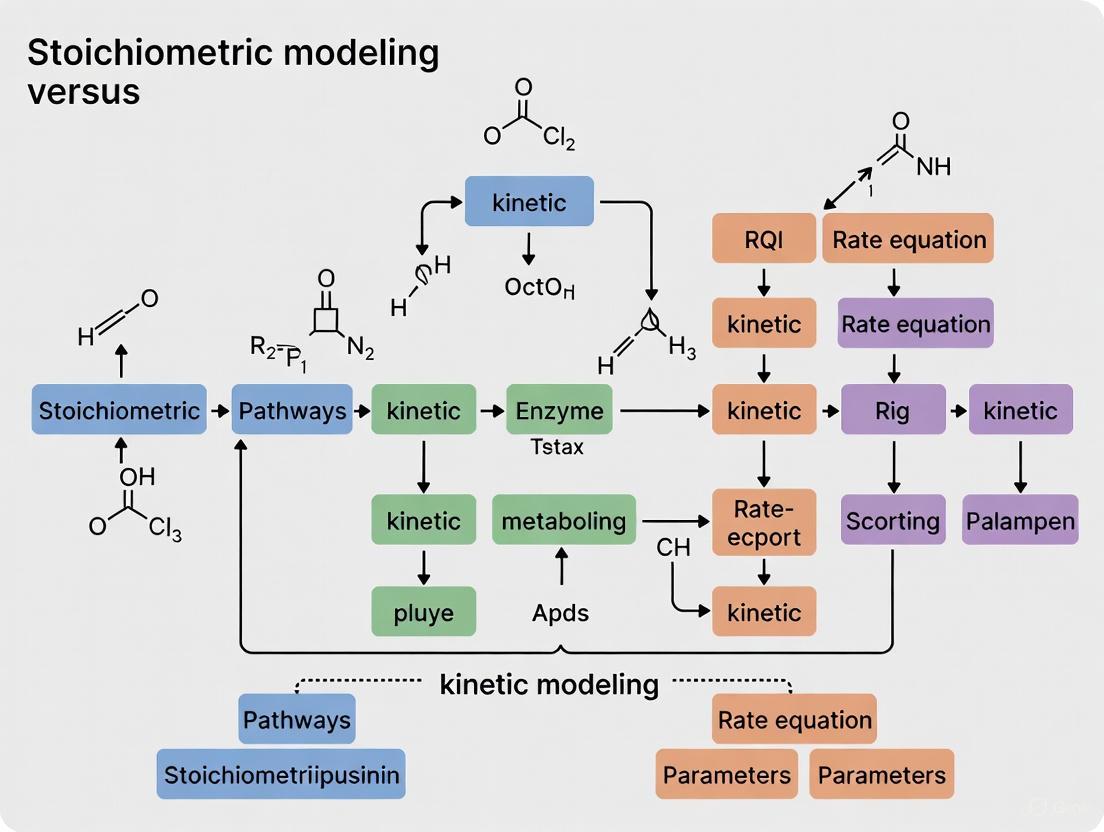

This article provides a systematic comparison of stoichiometric and kinetic modeling approaches for analyzing cellular metabolism, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Stoichiometric vs. Kinetic Metabolic Modeling: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of stoichiometric and kinetic modeling approaches for analyzing cellular metabolism, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles of both methods, from mass-balance constraints in stoichiometric models to mechanistic rate laws in kinetic frameworks. The content details specific methodologies and real-world applications in metabolic engineering and drug discovery, addressing common challenges such as parameter uncertainty, model standardization, and computational demands. Finally, we present validation strategies and a comparative analysis to guide model selection, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for leveraging these powerful tools in biomedical and clinical research.

Core Principles: Understanding the Fundamentals of Stoichiometric and Kinetic Models

Stoichiometric modeling represents a cornerstone methodology in systems biology for analyzing metabolic networks. This computational approach relies fundamentally on the principles of mass conservation and the steady-state assumption to predict metabolic fluxes within biological systems. Unlike kinetic models that require extensive parameterization of enzyme dynamics, stoichiometric models leverage the well-defined stoichiometry of biochemical reactions to constrain possible cellular behaviors. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of stoichiometric modeling frameworks, their mathematical foundations, implementation methodologies, and applications in metabolic engineering and drug discovery. Within the broader context of metabolic modeling approaches, stoichiometric modeling offers distinct advantages for genome-scale analysis and integration with multi-omic data, serving as a complementary approach to kinetic modeling in metabolism research.

Stoichiometric modeling has emerged as a powerful constraint-based approach for analyzing metabolic networks at various scales, from focused pathway analyses to genome-wide reconstructions. This methodology fundamentally relies on the stoichiometry of biochemical reactions—the quantitative relationships between reactants and products in chemical transformations—to define the constraints governing metabolic system behavior [1]. The stoichiometric matrix S, where each element Sᵢⱼ represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j, forms the mathematical foundation of these models [2]. This representation allows researchers to systematically analyze metabolic capabilities without requiring detailed kinetic parameters, which are often unavailable for entire metabolic networks [3].

In the context of metabolism research, stoichiometric modeling occupies a strategic position between purely topological network analyses and fully parameterized kinetic models. While kinetic models aim to capture the dynamic temporal behavior of metabolic systems through differential equations based on enzyme kinetics, stoichiometric models focus on predicting steady-state metabolic fluxes under various constraints [4]. This distinction makes stoichiometric modeling particularly valuable for genome-scale applications where comprehensive kinetic data remains limited, while kinetic modeling excels in detailed analyses of specific pathways where sufficient enzyme kinetic data exists [5]. The two approaches thus serve complementary roles in metabolic research, with stoichiometric models providing a platform for network-wide analyses and kinetic models offering deeper mechanistic insights for targeted pathway manipulations.

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

Mass Balances as Foundation

The principle of mass conservation provides the physical basis for stoichiometric modeling, asserting that matter cannot be created or destroyed within a closed system. In the context of metabolic networks, this translates to balancing the production and consumption of each metabolite within the system [6]. For each metabolite in the network, a mass balance equation can be written where the sum of its production rates equals the sum of its consumption rates at steady state [5]. This fundamental constraint significantly reduces the space of possible metabolic behaviors, enabling meaningful predictions about cellular physiology.

Mathematically, the mass balance constraint is expressed through the stoichiometric matrix S and the flux vector v as follows:

S ⋅ v = 0

This equation represents the system of linear equations where each row corresponds to a metabolite's mass balance and each column represents a reaction [2]. The solution to this equation defines the null space of the stoichiometric matrix, containing all flux distributions that satisfy the mass balance constraints [1]. For metabolic networks with more reactions than metabolites (a typical scenario), this system is underdetermined, allowing multiple feasible flux distributions that require additional constraints to identify biologically relevant solutions [7].

The Steady-State Assumption

The steady-state assumption is a critical simplification in stoichiometric modeling that posits metabolite concentrations remain constant over time despite ongoing metabolic activity [5]. This assumption transforms the inherently dynamic nature of metabolism into a tractable linear problem by eliminating the need to model transient concentration changes. Under steady-state conditions, the net flux through each metabolite pool equals zero, meaning the combined rates of metabolite production precisely balance the combined rates of consumption [6].

The steady-state assumption is biologically justified for many applications because metabolic networks often operate at pseudo-steady-state conditions, where intracellular metabolite concentrations stabilize much faster than environmental changes or cellular growth rates [4]. This is particularly valid when analyzing cellular growth during balanced growth conditions in continuous cultures or the exponential phase of batch cultures [7]. However, this assumption represents a key distinction from kinetic modeling, where temporal dynamics of metabolite concentrations are explicitly simulated using differential equations based on enzyme kinetic parameters [3].

Table 1: Key Constraints in Stoichiometric Modeling

| Constraint Type | Mathematical Representation | Basis/Principle | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Balance | S ⋅ v = 0 | Law of mass conservation | Universal for all stoichiometric models |

| Steady-State | dX/dt = 0 (metabolite concentrations constant) | Pseudo-steady-state in biological systems | Foundation for FBA and MFA |

| Reaction Directionality | vₗ ≤ v ≤ vᵤ (lower and upper bounds) | Thermodynamic feasibility | Constrains solution space based on reaction irreversibility |

| Energy Balance | ATP + H₂O ⇌ ADP + Pᵢ (energy conserved) | First law of thermodynamics | Incorporates energy metabolism |

| Enzyme Capacity | vᵢ ≤ kcat × [Eᵢ] | Limited enzyme resources | Organism-level constraint [5] |

Methodological Framework and Experimental Protocols

Model Reconstruction and Formulation

The construction of a stoichiometric model begins with comprehensive network reconstruction, which involves compiling all known metabolic reactions for the target organism based on genomic annotation and biochemical literature [2]. This process typically involves several methodical steps:

Genome Annotation and Reaction Identification: Using genomic data from databases such as KEGG, BRENDA, BioCyc, and UniProt to identify metabolic genes and their associated reactions [7].

Stoichiometric Matrix Assembly: Creating the S matrix where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions, with stoichiometric coefficients indicating the number of moles of each metabolite consumed (negative) or produced (positive) in each reaction [1].

Compartmentalization: Assigning reactions to specific cellular compartments (e.g., cytosol, mitochondria) when working with eukaryotic systems, which requires inclusion of transport reactions between compartments [7].

Network Gap Analysis: Identifying "dead-end" metabolites (those having only producing or only consuming reactions) and filling metabolic gaps through biochemical literature mining and experimental data integration [2].

Constraint Definition: Establishing reaction directionality constraints based on thermodynamic feasibility and adding capacity constraints based on enzyme levels or substrate uptake rates when available [5].

For mammalian systems, additional considerations include tissue-specific metabolic functions, inter-organ metabolite exchanges, and complex regulatory mechanisms that may require specialized constraints [7].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Protocol

Flux Balance Analysis represents the most widely applied computational method using stoichiometric models. The standard FBA protocol involves:

Objective Function Definition: Selecting a biologically relevant objective to optimize, most commonly biomass maximization for microbial systems or ATP production for specific tissue models [7]. The objective is represented as a linear function Z = cᵀv, where c is the vector of coefficients and v is the flux vector.

Constraint Implementation: Applying mass balance, thermodynamic, and capacity constraints to define the solution space:

- Mass balance: S ⋅ v = 0

- Flux constraints: α ≤ v ≤ β (where α and β are lower and upper bounds respectively) [2]

Linear Programming Solution: Using optimization algorithms to identify the flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes the objective function:

- Maximize Z = cᵀv

- Subject to S ⋅ v = 0 and α ≤ v ≤ β [1]

Solution Validation: Comparing predicted fluxes with experimental data such as growth rates, substrate uptake rates, or product secretion rates, and using (^{13})C-labeling experiments for intracellular flux validation when possible [7].

Sensitivity Analysis: Performing robustness analysis to determine how sensitive the optimal solution is to changes in constraints and evaluating potential alternative optimal solutions [3].

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) with Isotope Labeling

For more precise flux estimation, Metabolic Flux Analysis incorporating (^{13})C-labeling experiments provides a powerful experimental-computational hybrid approach:

Tracer Experiment Design: Selecting appropriate (^{13})C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-(^{13})C]glucose, [U-(^{13})C]glucose) based on the metabolic pathways of interest [7].

Isotope Steady-State Cultivation: Growing cells under metabolic steady-state conditions with the labeled substrate until isotope labeling in intracellular metabolites reaches isotopic steady state [8].

Metabolite Extraction and Mass Spectrometry: Quenching metabolism rapidly, extracting intracellular metabolites, and analyzing mass isotopomer distributions using GC-MS or LC-MS [8].

Stoichiometric Model Expansion: Extending the stoichiometric model to include carbon atom transitions between metabolites, creating an atom mapping matrix [7].

Isotopomer Balance Equations: Implementing isotopomer or mass isotopomer balances in addition to mass balances to constrain the system further [2].

Parameter Estimation: Using nonlinear optimization to find the flux distribution that best fits the experimental mass isotopomer distribution data, minimizing the difference between simulated and measured labeling patterns [4].

This methodology provides significantly improved flux resolution compared to conventional FBA, particularly for parallel pathways and reversible reactions [7].

Comparative Analysis: Stoichiometric vs. Kinetic Modeling

The choice between stoichiometric and kinetic modeling approaches depends on the research question, data availability, and desired predictive capabilities. The fundamental distinctions between these approaches are substantial and impact their application domains.

Table 2: Stoichiometric vs. Kinetic Modeling Approaches

| Characteristic | Stoichiometric Modeling | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Basis | Linear algebra (S ⋅ v = 0) | Differential equations (dX/dt = f(X,v)) |

| Primary Constraints | Reaction stoichiometry, steady-state assumption | Enzyme kinetics, thermodynamic laws |

| Metabolite Concentrations | Not explicitly calculated | Explicitly simulated as variables |

| Temporal Dynamics | Not captured (steady-state only) | Explicitly simulated over time |

| Parameter Requirements | Stoichiometric coefficients, flux constraints | Kinetic parameters (kcat, Km), enzyme concentrations |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale feasible | Typically pathway-scale (≤100 reactions) |

| Predictive Capabilities | Flux distributions at steady-state | Metabolic dynamics, transients, oscillations |

| Regulatory Mechanisms | Indirectly via constraints | Directly via kinetic expressions |

| Computational Complexity | Linear/quadratic programming | Nonlinear optimization, ODE integration |

| Key Applications | Strain design, gene essentiality, pathway analysis | Metabolic regulation, drug effects, dynamic responses |

Stoichiometric models excel in applications requiring genome-scale coverage, including gene knockout prediction, metabolic engineering design, and network property analysis [9]. The steady-state assumption enables the analysis of large networks with limited parameters, making these models particularly valuable when comprehensive kinetic data is unavailable [1]. Furthermore, stoichiometric models provide an ideal framework for integrating multi-omic data, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, through the imposition of additional constraints [2].

In contrast, kinetic models offer superior capabilities for analyzing metabolic regulation, predicting transient responses to perturbations, and understanding the dynamic behavior of metabolic systems [3]. The explicit incorporation of enzyme mechanisms and allosteric regulation allows kinetic models to capture complex regulatory phenomena that stoichiometric models cannot represent [4]. However, this enhanced predictive capability comes at the cost of extensive parameterization requirements, limiting kinetic models to well-characterized pathways where sufficient experimental data exists for parameter estimation [5].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

Stoichiometric modeling has found diverse applications in drug discovery and development, particularly in identifying novel drug targets and understanding disease metabolism.

Drug Target Identification

Stoichiometric models of human pathogens have been successfully employed to identify essential genes and reactions that represent potential drug targets [8]. By simulating gene knockout effects through constraint-based methods, researchers can systematically identify metabolic choke points whose inhibition would disrupt pathogen growth or virulence [9]. This approach has been applied to various pathogenic microorganisms, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Plasmodium falciparum, leading to the identification of novel targets for antibiotic and antimalarial development [8].

For cancer research, stoichiometric models of cancer cell metabolism have revealed metabolic dependencies associated with oncogenic transformations [7]. By comparing flux distributions in normal versus cancer cells, researchers have identified cancer-specific metabolic vulnerabilities that can be targeted therapeutically [8]. For instance, analyses of nucleotide biosynthesis, glutathione metabolism, and aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) have revealed potential targets for selective anticancer agents [2].

Biomarker Discovery and Toxicological Assessment

Stoichiometric modeling facilitates the identification of metabolic biomarkers for disease diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring [8]. By integrating metabolomic data with stoichiometric models, researchers can identify metabolic alterations characteristic of specific disease states or drug responses [7]. This approach has shown promise in oncology for identifying circulating metabolites associated with tumor metabolism and in metabolic diseases for detecting pathway disruptions before clinical symptoms manifest [8].

In toxicology, stoichiometric models of hepatic metabolism have been used to predict drug-induced liver injury and assess metabolite toxicity [7]. These models can simulate the flux consequences of enzyme inhibition, allowing researchers to identify potential metabolic imbalances and toxic metabolite accumulation resulting from drug exposure [5]. This application is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development for prioritizing drug candidates with lower metabolic toxicity risks.

Personalized Medicine and Multi-Omic Integration

The advent of tissue-specific and patient-specific metabolic models has opened new avenues for personalized medicine applications [2]. By constructing individualized models based on genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data, researchers can predict metabolic variations in drug responses across patient populations [7]. This approach enables the identification of patient subgroups likely to benefit from specific therapies and those at risk for adverse drug reactions based on their metabolic capacity [8].

Stoichiometric models provide an ideal framework for integrating multi-omic data through the imposition of context-specific constraints [9]. Transcriptomic and proteomic data can be incorporated to define activity levels of specific reactions, while metabolomic data can further constrain flux distributions [2]. This integrative capability allows researchers to build increasingly refined models that more accurately represent the metabolic state of specific cells, tissues, or patients under various physiological and pathological conditions [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for Stoichiometric Modeling

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Resource | Type/Function | Application in Stoichiometric Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| (^{13})C-Labeled Substrates | Isotopic tracers (e.g., [1-(^{13})C]glucose) | Experimental flux validation via MFA [7] |

| GC-MS / LC-MS Systems | Analytical instrumentation | Measurement of mass isotopomer distributions [8] |

| KEGG Database | Biochemical pathway database | Metabolic network reconstruction [7] |

| BRENDA | Enzyme kinetics database | Kinetic parameter estimation for hybrid models [3] |

| BioCyc | Metabolic pathway database | Reaction stoichiometry and pathway information [7] |

| SBML | Model representation format (Systems Biology Markup Language) | Model exchange and reproducibility [8] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based software suite | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis [9] |

| OptFlux | Open-source software platform | Metabolic engineering applications [4] |

| Human Metabolic Atlas | Tissue-specific metabolic models | Human metabolism and disease research [2] |

| ModelSeed | Web-based resource | Rapid model reconstruction from genomes [9] |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

Stoichiometric modeling continues to evolve with advancements in computational methods and experimental technologies. Several emerging trends are shaping the future of this field:

Integration with Kinetic Modeling: Hybrid approaches that combine the genome-scale coverage of stoichiometric models with the dynamic predictive power of kinetic models represent a promising direction [3]. Methods such as k-OptForce bridge this gap by integrating kinetic model predictions within stoichiometric optimization frameworks [4]. These integrated approaches leverage the respective strengths of both modeling paradigms while mitigating their individual limitations.

Single-Cell Metabolic Modeling: As single-cell technologies mature, developing approaches to construct cell-specific stoichiometric models based on single-cell omics data will enable unprecedented resolution in analyzing metabolic heterogeneity [2]. This capability is particularly relevant for understanding tumor metabolism and microbial population dynamics.

Machine Learning Integration: Combining stoichiometric modeling with machine learning approaches offers powerful opportunities for enhanced phenotype prediction and model refinement [8]. Machine learning can help identify patterns in high-dimensional flux spaces and suggest additional constraints based on experimental data.

Expanded Scope Beyond Metabolism: Future stoichiometric frameworks will increasingly integrate metabolic networks with other cellular processes, including signaling, gene regulation, and protein synthesis [9]. This expansion will provide more comprehensive models of cellular physiology with enhanced predictive capabilities for complex biological responses.

In conclusion, stoichiometric modeling founded on mass balances and steady-state assumptions provides an indispensable framework for analyzing metabolic networks across diverse applications. Its mathematical rigor, computational efficiency, and adaptability to multi-omic integration make it particularly valuable for metabolic engineering, drug discovery, and systems biology research. While kinetic modeling offers superior capabilities for analyzing dynamic metabolic regulation, stoichiometric modeling remains the method of choice for genome-scale analyses and applications requiring network-wide perspective. As the field advances, the continued refinement of stoichiometric approaches and their integration with complementary methodologies will further expand their impact on metabolism research and biomedical applications.

In the field of metabolism research, two principal computational frameworks have emerged for modeling biochemical networks: stoichiometric modeling and kinetic modeling. While stoichiometric models, particularly those used in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), have proven invaluable for predicting steady-state metabolic fluxes at genome-scale, they possess inherent limitations. These constraint-based approaches treat the metabolic network as a system of linear equations under physicochemical constraints, but they cannot capture time-dependent behaviors, metabolite concentrations, or regulation mechanisms that define cellular physiology. Kinetic modeling addresses these limitations by explicitly incorporating enzyme mechanisms and reaction dynamics, thereby providing a more comprehensive representation of metabolic systems.

Kinetic models mathematically represent the catalytic properties of enzymes and how they influence metabolic dynamics through rate equations and kinetic parameters. Unlike stoichiometric models that assume a steady state, kinetic models simulate how metabolite concentrations change over time in response to perturbations, environmental changes, or genetic modifications. This capability is crucial for both basic research and applied biotechnology, where understanding the dynamic behavior of metabolic networks is essential for predicting cellular responses, engineering optimized pathways, and developing therapeutic interventions in metabolic diseases.

Fundamental Principles of Kinetic Modeling

Core Mathematical Framework

Kinetic modeling of metabolic networks is fundamentally based on systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe the temporal evolution of metabolite concentrations. For each metabolite in the system, its rate of change is determined by the difference between the fluxes that produce it and consume it:

dX/dt = N · v(X,p)

Where X is the vector of metabolite concentrations, N represents the stoichiometric matrix (defining the network structure), and v(X,p) is the vector of kinetic rate laws that depend on both metabolite concentrations and kinetic parameters p. This formulation explicitly couples the network topology (captured in N) with the enzymatic mechanisms (encoded in v), creating a dynamic representation of metabolism that can simulate transient behaviors and multiple steady states.

Enzyme Kinetic Rate Laws

The accuracy of kinetic models depends critically on the appropriate selection of rate laws that describe how enzyme catalytic rates respond to metabolite concentrations. Several classes of rate laws are employed in practice:

- Mechanistic Rate Laws: Detailed equations derived from enzyme mechanism theories, such as Michaelis-Menten kinetics for irreversible reactions or more complex expressions for multi-substrate, cooperativity, and allosteric regulation phenomena.

- Approximative Rate Laws: Simplified representations including power-law approximations (as used in Biochemical Systems Theory), lin-log kinetics, and convenience kinetics that require fewer parameters while capturing essential kinetic features.

- Hybrid Approaches: Combining detailed mechanistic equations for key regulatory enzymes with simplified approximations for other reactions, enabling feasible modeling of large networks while maintaining biological accuracy [10].

The choice of rate law involves trade-offs between biological fidelity, parameter identifiability, and computational tractability, often guided by the available experimental data and the specific modeling objectives.

Kinetic versus Stoichiometric Modeling: A Comparative Analysis

The distinction between kinetic and stoichiometric modeling approaches represents a fundamental dichotomy in metabolic modeling, with each offering complementary strengths and limitations.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of stoichiometric versus kinetic modeling approaches

| Feature | Stoichiometric Modeling | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Basis | Linear algebra & constraint-based optimization | Nonlinear ordinary differential equations |

| Time Resolution | Steady-state only | Dynamic & transient states |

| Metabolite Concentrations | Not explicitly considered | Explicitly simulated |

| Enzyme Mechanisms | Not incorporated | Explicitly represented through rate laws |

| Parameter Requirements | Network stoichiometry only | Kinetic parameters (KM, Vmax, KI, etc.) |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale feasible | Typically pathway-scale (increasingly larger) |

| Regulatory Predictions | Limited to flux capacity constraints | Captures metabolic regulation & control |

| Key Applications | Flux prediction, strain design, gap filling | Dynamic response analysis, drug targeting, metabolic engineering |

Stoichiometric models, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), have dominated genome-scale metabolic reconstructions due to their ability to work without detailed kinetic information. However, kinetic models provide the critical link between metabolite concentrations, metabolic fluxes, and enzyme levels through mechanistic relations, enabling prediction of cellular responses to genetic and environmental perturbations that are impossible with stoichiometric approaches alone [11]. This capability makes kinetic modeling indispensable for studying complex phenomena such as metabolic reprogramming in disease states, drug metabolism dynamics, and engineering of cell factories for biotechnology.

Methodological Approaches for Kinetic Model Development

Hybrid Kinetic Modeling Strategy

Developing comprehensive kinetic models for metabolic networks faces the significant challenge of parameter uncertainty, as reliable kinetic parameters are unavailable for many enzymes. To address this, hybrid modeling approaches have been proposed that strategically combine different levels of kinetic detail within a single model framework [10].

The hybrid approach recognizes that metabolic control is often exerted by a narrow set of key regulatory enzymes. In this strategy, only these central regulatory enzymes are described by detailed mechanistic rate equations, while the majority of enzymes are approximated by simplified rate laws (e.g., mass action, LinLog, Michaelis-Menten, or power law). This hybrid method significantly reduces the number of parameters that need to be experimentally determined while maintaining the model's ability to capture essential regulatory features and dynamic behaviors.

Validation studies applying this hybrid approach to both red blood cell energy metabolism and hepatic purine metabolism have demonstrated that these models reliably calculate stationary and temporary states under various physiological challenges, performing nearly as well as comprehensive mechanistic models but with substantially reduced parameter requirements [10].

Flexible Nets: A Unifying Formalism

A novel approach to integrating stoichiometric and kinetic modeling is the concept of Flexible Nets (FNs), which provides a unifying formalism that subsumes both constraint-based models and differential equations [12]. Flexible Nets consist of two connected subnets:

- Event Net: Accounts for the stoichiometry of the system, defining how reaction occurrences modify metabolite concentrations.

- Intensity Net: Models the kinetics of the reactions, describing how metabolite concentrations modulate reaction rates.

This formalism introduces handlers as an intermediate layer between places (metabolites) and transitions (reactions), capturing both stoichiometric relationships and kinetic modulation. FNs can seamlessly incorporate uncertain parameters through inequalities associated with handlers, making them particularly valuable for modeling biological systems where precise kinetic parameters are unknown [12].

Machine Learning-Accelerated Parameterization

Recent advances have introduced generative machine learning frameworks to overcome the computational challenges of kinetic model parameterization. The RENAISSANCE framework employs feed-forward neural networks optimized with Natural Evolution Strategies (NES) to efficiently parameterize large-scale kinetic models with dynamic properties matching experimental observations [11].

The RENAISSANCE workflow involves four iterative steps:

- Initialization of generator populations with random weights

- Production of kinetic parameter sets using generator networks

- Evaluation of dynamic properties of parameterized models

- Reward-based optimization of generator weights

This approach dramatically reduces computation time compared to traditional kinetic modeling methods while maintaining biological relevance. When applied to parameterize a large-scale kinetic model of E. coli metabolism (113 ODEs, 502 kinetic parameters), RENAISSANCE achieved up to 100% incidence of valid models that correctly captured the experimentally observed doubling time and exhibited robust stability to perturbations [11].

Diagram 1: The RENAISSANCE machine learning framework for kinetic model parameterization

Computational Tools and Software Platforms

Several computational tools have been developed to facilitate kinetic modeling of metabolic systems, offering integrated environments for model construction, simulation, and analysis.

Table 2: Computational tools for kinetic modeling of metabolic systems

| Tool/Platform | Key Features | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|

| IsoSim | Stoichiometric & kinetic modeling, 13C-flux calculation, dynamic isotope propagation, parameter estimation | Metabolic systems under stationary/dynamic conditions [13] |

| Spot-On | Kinetic modeling of single particle tracking (SPT) data, accounts for finite detection volume, bias correction | Biomolecular dynamics and diffusion [14] |

| RENAISSANCE | Generative machine learning, neural network parameterization, integration of multi-omics data | Large-scale kinetic model development [11] |

| Flexible Nets | Unified stoichiometric/kinetic formalism, handles parameter uncertainty, nonlinear dynamics | Metabolic networks with incomplete data [12] |

These tools increasingly incorporate methods for handling parameter uncertainty, integrating multi-omics data, and leveraging machine learning approaches to overcome traditional limitations in kinetic model development.

Experimental Protocols and Parameter Determination

Kinetic Parameter Estimation Workflow

The development of reliable kinetic models requires careful parameter estimation through iterative cycles of computational and experimental approaches:

Initial Parameter Collection: Compile available kinetic parameters (KM, kcat, KI) from literature databases, enzyme kinetics resources, and previous studies.

Steady-State Data Integration: Incorporate experimentally determined metabolite concentrations, metabolic fluxes, and enzyme abundances from omics measurements to establish physiological baseline conditions.

Parameter Sampling and Optimization: Use computational algorithms (e.g., Monte Carlo sampling, evolutionary strategies, gradient-based optimization) to identify parameter sets consistent with experimental data.

Model Validation and Refinement: Test model predictions against independent experimental datasets not used in parameterization, particularly dynamic time-course measurements following perturbations.

Sensitivity Analysis: Perform global sensitivity analysis to identify parameters with greatest influence on model outputs, guiding targeted experimental efforts for parameter refinement.

Modern kinetic modeling frameworks increasingly leverage multiple types of omics data to constrain model parameters and reduce uncertainty:

- Metabolomics: Provides absolute or relative metabolite concentration measurements for model validation.

- Fluxomics: Delieves experimental flux measurements, typically from 13C-tracer experiments, for parameter estimation.

- Proteomics: Quantifies enzyme abundances that can inform Vmax parameter values.

- Thermodynamics: Incorporates thermodynamic constraints (reaction reversibility, energy barriers) to restrict feasible parameter space.

Tools like IsoSim specifically enable the integration of metabolomics, proteomics, and isotopic data with kinetic, thermodynamic, regulatory, and stoichiometric constraints [13], creating more biologically realistic models.

Diagram 2: Kinetic parameter estimation and model validation workflow

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational resources for kinetic modeling

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | IsoSim R Package, Spot-On, Flexible Nets framework | Kinetic model construction, simulation, and analysis [13] [14] [12] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | RENAISSANCE (TensorFlow/PyTorch implementations) | Accelerated parameterization of large-scale kinetic models [11] |

| Parameter Databases | BRENDA, SABIO-RK, MetaCyc | Kinetic parameter priors and enzyme kinetic information |

| Isotopic Tracers | 13C-glucose, 13C-glutamine, 15N-ammonia | Experimental flux determination for model validation [13] |

| Metabolomics Platforms | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR spectroscopy | Metabolite concentration measurements for model constraints |

| Enzyme Assay Systems | Spectrophotometric assays, coupled enzyme systems | Direct determination of enzyme kinetic parameters |

Kinetic modeling represents an essential methodology for advancing our understanding of cellular metabolism beyond the capabilities of stoichiometric approaches alone. By explicitly incorporating enzyme mechanisms and reaction dynamics, kinetic models provide a powerful framework for predicting metabolic behaviors under varying physiological conditions, designing metabolic engineering strategies, and identifying therapeutic targets for metabolic diseases.

The field is rapidly evolving with several promising directions:

Hybrid Multi-Scale Models: Integration of kinetic metabolic models with other cellular processes, including gene regulation, signaling networks, and physiological constraints.

Machine Learning Integration: Increased use of generative AI approaches like RENAISSANCE to overcome parameterization bottlenecks and enable genome-scale kinetic modeling.

Uncertainty-Aware Frameworks: Broader adoption of formalisms like Flexible Nets that explicitly handle parameter uncertainty and incomplete knowledge.

Automated Model Construction: Development of pipelines for semi-automated construction of kinetic models from genome-scale stoichiometric reconstructions and multi-omics datasets.

As these advancements mature, kinetic modeling is poised to become an increasingly central methodology in metabolic engineering, systems biology, and drug development, enabling more predictive and precise manipulation of cellular metabolism for biotechnology and therapeutic applications.

In the realm of metabolic modeling, two mathematical frameworks have emerged as fundamental paradigms for representing and analyzing biochemical networks: the stoichiometric matrix and systems of differential equations. These constructs form the computational backbone of distinct modeling approaches—stoichiometric (constraint-based) and kinetic (dynamic) modeling, respectively—each with unique capabilities and limitations [15] [5]. The choice between these frameworks is not merely technical but fundamentally shapes the questions a researcher can address, the data requirements, and the biological insights attainable.

Stoichiometric modeling, centered on the stoichiometric matrix, focuses on the network topology and mass balance constraints that govern possible metabolic states, typically at steady-state conditions [16]. In contrast, kinetic modeling using differential equations aims to capture the temporal dynamics of metabolic concentrations and fluxes based on reaction kinetics and regulatory mechanisms [15] [17]. This technical guide examines these core constructs within the broader thesis of stoichiometric versus kinetic modeling, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured comparison to inform methodological selection in metabolic research.

Mathematical Foundations and Formulations

The Stoichiometric Matrix: Structure and Constraints

The stoichiometric matrix (

S

*) provides a mathematical representation of a metabolic network's connectivity. This *

m × n

* matrix, where *

m

* represents metabolites and *

n

* represents reactions, encodes the stoichiometric coefficients of each metabolite in every biochemical reaction [16] [18]. The entry *

S

ij

* indicates the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite *

i

* in reaction *

j

, with conventions typically defining negative values for substrates and positive values for products [18].

The fundamental equation for stoichiometric modeling is the mass balance equation:

S · v = 0

where

v

is the vector of reaction fluxes (rates) [16]. This equation represents the steady-state assumption that internal metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, implying that for each metabolite, the sum of its production fluxes equals the sum of consumption fluxes.

The stoichiometric matrix enables the identification of key system properties:

- Conserved metabolic pools: Moieties such as ATP/ADP/AMP or NAD/NADH that are recycled within the network, identifiable through the left null space of

S

[16].

- Feasible steady-state flux distributions: The right null space of

S

* contains all possible flux vectors *

v

satisfying the mass balance constraints [16].

- Network-based pathway analysis: Elementary flux modes and extreme pathways representing minimal functional metabolic units can be derived from

S

[16].

Diagram 1: Stoichiometric modeling workflow based on matrix structure.

Differential Equations: Capturing Metabolic Dynamics

Kinetic models represent metabolic systems through ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe the temporal evolution of metabolite concentrations. For a system with

m

metabolites, the dynamics are captured by:

dx/dt = N · v(x, p)

where

x

* is the vector of metabolite concentrations, *

N

* is the stoichiometric matrix (often identical to *

S

* but emphasizing its role in dynamic systems), and *

v(x, p)

* is the vector of reaction rates that generally depends on both metabolite concentrations and kinetic parameters *

p

The rate laws

v

_i

(x, p)

can take various forms depending on the reaction mechanism:

- Mass action kinetics: $

v = k \prod [Xi]^{ni}

$

- Michaelis-Menten kinetics: $

v = \frac{V{\text{max}} [S]}{Km + [S]}

$

- Inhibitory and regulatory terms: Incorporating allosteric regulation and complex enzyme mechanisms [15] [5].

Unlike stoichiometric models that assume steady-state, kinetic models explicitly simulate the transient behavior of metabolic systems, allowing researchers to investigate how perturbations propagate through networks and how systems transition between states [17].

Diagram 2: Kinetic modeling framework using differential equations.

Comparative Analysis: Capabilities and Limitations

Table 1: Fundamental comparison between stoichiometric and kinetic modeling approaches

| Feature | Stoichiometric Matrix Approach | Differential Equations Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Basis | Linear algebra; Constraint-based optimization [16] | Ordinary differential equations; Nonlinear dynamics [17] |

| Primary Output | Steady-state flux distributions; Pathway capabilities [16] | Time-course concentrations; Dynamic responses [17] |

| Data Requirements | Stoichiometry; Network topology; Exchange fluxes [16] [19] | Kinetic parameters; Initial concentrations; Rate laws [15] [5] |

| Temporal Resolution | Steady-state (no time dimension) [16] | Explicit time dependence [17] |

| Regulatory Representation | Indirect (via constraints) [5] | Direct (via kinetic expressions) [15] |

| System Scale | Genome-scale (thousands of reactions) [19] [7] | Pathway-scale (dozens to hundreds of reactions) [5] |

| Parameter Estimation | Flux constraints; Optimality principles [16] | Nonlinear regression; Parameter fitting [15] |

| Computational Complexity | Linear programming; Convex optimization [16] | Nonlinear ODE integration; Potential stiffness [17] |

Methodological Implementation

Protocol for Stoichiometric Modeling with Flux Balance Analysis

Objective: Predict cellular phenotype from genome-scale metabolic network under specified environmental conditions.

Procedure:

- Network Reconstruction: Compile the stoichiometric matrix from genomic (KEGG, BioCyc) and biochemical (BRENDA) databases [19].

- Constraint Definition:

- Set flux bounds: $

\alphai \leq vi \leq \beta_i

$

- Define exchange fluxes based on nutrient availability

- Incorporate thermodynamic constraints (irreversibility) [5]

- Objective Specification: Define cellular objective (e.g., biomass maximization, ATP production) as linear function $

Z = c^T v

- Optimization: Solve the linear programming problem:

$

\begin{aligned} &\max_{v} c^T v \ &\text{subject to } S \cdot v = 0 \ &\alpha \leq v \leq \beta \end{aligned}

$

- Solution Analysis: Interpret flux distribution, identify key pathways, perform sensitivity analysis [16].

Validation: Compare predicted growth rates or substrate uptake with experimental measurements [19] [7].

Protocol for Kinetic Modeling with Ordinary Differential Equations

Objective: Simulate dynamic metabolic response to perturbations or changing conditions.

Procedure:

- Network Definition: Identify relevant metabolites and reactions within pathway scope [5].

- Mechanistic Formulation:

- Assign appropriate rate laws to each reaction

- Compile kinetic parameters from literature or experiments [15]

- Model Implementation:

- Code the ODE system: $

\frac{dxi}{dt} = \sumj N{ij} vj(x, p)

$

- Set initial metabolite concentrations [17]

- Parameter Estimation (if needed):

- Use steady-state metabolite concentrations as constraints

- Apply optimization algorithms to fit parameters to experimental data [15] [5]

Validation: Compare simulated dynamics with time-course concentration measurements from perturbation experiments [15].

Table 2: Data requirements and sources for metabolic modeling

| Requirement | Stoichiometric Modeling | Kinetic Modeling | Common Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Structure | Essential [19] | Essential [5] | KEGG, BioCyc, MetaCyc [19] |

| Stoichiometry | Essential [18] | Essential [16] | Biochemical literature [15] |

| Flux Measurements | Validation [7] | Parameter estimation [15] | 13C labeling, fluxomics [7] |

| Kinetic Constants | Not required | Essential [5] | BRENDA, SABIO-RK [15] [19] |

| Metabolite Concentrations | Not required | Initial conditions [17] | Metabolomics, mass spectrometry [21] |

| Enzyme Activities | Optional constraints [5] | Parameterization [5] | Proteomics, enzyme assays [5] |

Advanced Applications and Integrative Approaches

Hybrid Frameworks and Multi-Scale Modeling

Advanced metabolic modeling often combines strengths of both approaches through hybrid frameworks. For instance, dynamic flux balance analysis (dFBA) integrates the FBA framework within differential equations describing extracellular environment changes [20]. The general formulation for spatiotemporal metabolic models captures this integration:

$

\begin{aligned} &\frac{\partial Xi}{\partial t} = (\mui - \mu{di})Xi - \frac{uL}{\varepsilonL}\frac{\partial Xi}{\partial z} + D{iX}\frac{\partial^2 Xi}{\partial z^2} \ &\frac{\partial Mj}{\partial t} = \sum{i=1}^N v{ij}Xi - \frac{uL}{\varepsilonL}\frac{\partial Mj}{\partial z} + D{jL}\frac{\partial^2 Mj}{\partial z^2} + \frac{kj}{\varepsilonL}(Mj^* - Mj) \end{aligned}

$

where intracellular metabolism may be modeled using FBA while extracellular environment dynamics use differential equations [20].

Another integrative approach uses stoichiometric modeling for network validation of kinetic models. Steady-state fluxes from kinetic models can be tested for feasibility in genome-scale stoichiometric models to ensure mass and energy balance at a systems level [5]. This synergy helps overcome the scale limitations of kinetic modeling while providing dynamic insights beyond stoichiometric constraints.

Table 3: Key computational tools and databases for metabolic modeling

| Resource | Function | Applicability |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Tools | Pathway/genome database construction; Metabolic network reconstruction [19] | Both approaches |

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis [19] | Stoichiometric modeling |

| DFBAlab | Dynamic FBA simulations [20] | Hybrid approaches |

| KEGG | Reference metabolic pathways; Genomic information [19] | Both approaches |

| BRENDA | Comprehensive enzyme kinetic data [15] [19] | Kinetic modeling |

| BioCyc/MetaCyc | Curated metabolic pathway databases [15] [19] | Both approaches |

| ModelSEED | Automated metabolic reconstruction [19] | Stoichiometric modeling |

| SBML | Model representation and exchange format [21] | Both approaches |

The choice between stoichiometric matrix and differential equation frameworks represents a fundamental tradeoff in metabolic modeling. Stoichiometric approaches excel in comprehensive network coverage and minimal parameter requirements, making them invaluable for genome-scale predictions and network property analysis [16] [19]. Differential equation approaches provide temporal resolution and mechanistic detail essential for understanding dynamic responses and complex regulation [15] [17].

For drug development professionals, this distinction has practical implications. Stoichiometric modeling facilitates target identification through gene essentiality analysis and network-wide vulnerability assessment [7] [21]. Kinetic modeling enables dose-response prediction and drug perturbation analysis by simulating how interventions alter metabolic dynamics over time [5].

The evolving frontier lies in hybrid methodologies that transcend this traditional dichotomy. Approaches such as constraint-based kinetic modeling and dynamic flux balance analysis are creating intermediate paradigms that leverage the scalability of stoichiometric models while capturing essential temporal dynamics [20]. As multi-omic datasets continue to expand, the integration of both constructs will be essential for developing predictive metabolic models that address the complexity of human pathophysiology and therapeutic intervention.

Chemical Moisty Conservation and Network Topology

In metabolic network analysis, a conserved moiety is a specific chemical group or atom (such as ATP, NADH, or phosphate groups) that remains constant in total quantity within a closed biochemical system, despite being exchanged between different molecular species. The identification and analysis of these conserved moieties is fundamental to understanding the topological and dynamic properties of metabolic networks. The principles of moiety conservation create critical bridges between the two predominant modeling approaches in metabolism research: stoichiometric modeling and kinetic modeling.

Stoichiometric models, including those used in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), rely fundamentally on the stoichiometric matrix (S) that describes the quantitative relationships between metabolites in biochemical reactions. Within this framework, conserved moieties correspond to linear dependencies in the stoichiometric matrix, revealing themselves through left null space vectors that represent metabolite pools with invariant concentrations. This mathematical relationship directly influences network topology by defining functional modules and thermodynamic constraints. In contrast, kinetic models incorporate temporal dynamics through enzymatic rate equations, where conserved moieties impose algebraic constraints that reduce system dimensionality and stabilize numerical integration. The recent development of large-scale kinetic models for organisms like Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas putida demonstrates how enzyme saturation states and moiety conservation patterns interact to determine metabolic flexibility and robustness [22] [23].

This technical guide explores the fundamental principles of chemical moiety conservation, its relationship to metabolic network topology, and its critical implications for both stoichiometric and kinetic modeling frameworks in metabolic engineering and drug development research.

Fundamental Principles of Moiety Conservation

Mathematical Foundation

The mathematical description of moiety conservation originates from the fundamental mass balance equation of metabolic systems:

dX/dt = S·v

Where X is the vector of metabolite concentrations, S is the stoichiometric matrix, and v is the flux vector. A conserved moiety exists when there is a vector L such that:

L·S = 0

This relationship indicates that the linear combination of metabolite concentrations defined by L remains constant over time. The vectors L form a basis for the left null space of S, with each basis vector corresponding to a distinct conserved moiety in the system.

Table 1: Key Mathematical Properties of Conserved Moieties

| Property | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Conservation | d(L·X)/dt = 0 | Total pool size remains constant despite internal transformations |

| Stoichiometric Dependency | L·S = 0 | Linear dependence between rows of stoichiometric matrix |

| Dimensionality Reduction | System order = n - m (n metabolites, m moieties) | Reduced number of independent differential equations |

| Thermodynamic Constraints | ΔG = ΔG°' + RT·ln(Γ) | Conservation relationships affect reaction thermodynamics |

Classification of Conserved Moieties

Conserved moieties in biochemical networks can be categorized based on their chemical nature and systemic role:

- Energy Currency Moieties: ATP/ADP/AMP pools, NAD+/NADH, NADP+/NADPH

- Phosphate Moieties: Inorganic phosphate, phosphoryl groups

- Amino Group Moieties: Glutamate/glutamine, aspartate/asparagine

- One-Carbon Moieties: Tetrahydrofolate-bound single carbon units

- Charge-Balancing Moieties: Cations (Mg²⁺, K⁺) that counterbalance phosphate charges

In practical applications, the identification of conserved moieties enables significant simplification of metabolic models. For kinetic models of Pseudomonas putida metabolism, thermodynamic curation incorporating moiety conservation relationships has proven essential for predicting metabolic responses to genetic perturbations and environmental stresses [23].

Computational Implementation and Analysis

Algorithmic Identification of Conserved Moieties

The computational identification of conserved moieties begins with decomposition of the stoichiometric matrix to find its left null space. The following workflow outlines this process:

Diagram 1: Computational identification workflow for conserved moieties in metabolic networks.

The implementation of this workflow requires specific computational tools and approaches:

Table 2: Computational Methods for Moiety Conservation Analysis

| Method | Algorithm | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) | Decomposition of S to identify orthogonal basis vectors | Initial discovery of conservation relationships |

| Gaussian Elimination | Row reduction to identify linearly dependent rows | Manual analysis of small networks |

| Elementary Mode Analysis | Identification of minimal functional units | Pathway analysis in stoichiometric models |

| ORACLE Framework | Monte Carlo sampling of kinetic parameters | Integration of thermodynamics and kinetics in large-scale models [22] [23] |

Network Topology Implications

The topological structure of metabolic networks directly influences the conservation relationships present in the system. Key topological features associated with moiety conservation include:

- Cyclic Structures: Metabolic cycles (e.g., TCA cycle) often contain conserved moieties

- Highly Connected Metabolites: Hub metabolites (ATP, CoA) participate in multiple conservation relationships

- Module Boundaries: Conserved moieties define functional modules within larger networks

In genome-scale metabolic networks (GEMs), the integration of thermodynamic data with stoichiometric information enables the identification of infeasible thermodynamic cycles and elimination of flux distributions that violate energy conservation constraints [23] [2]. This integration is particularly important in the development of tissue-specific human metabolic models for biomedical applications.

Experimental Methodologies for Validation

Protocol for Experimental Verification

Experimental validation of computationally predicted moiety conservation relationships requires integration of analytical biochemistry techniques with isotope labeling approaches. The following protocol provides a generalized methodology:

Materials and Equipment

- LC-MS/MS system with electrospray ionization

- Stable isotope-labeled precursors (¹³C-glucose, ¹⁵N-glutamine)

- Quenching solution (60% methanol, 70% ethanol, or cold glycerol-saline)

- Extraction solvents (methanol, chloroform, water)

- Normalization standards (deuterated internal standards)

Procedure

- Culture Preparation: Grow cells under defined physiological conditions to mid-exponential phase

- Isotope Pulse: Rapidly introduce isotope-labeled substrate with precise timing

- Metabolite Quenching: At designated time points (0, 15, 30, 60, 120 sec), transfer aliquots to cold quenching solution (-40°C)

- Metabolite Extraction: Implement dual-phase extraction for comprehensive coverage

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Separate metabolites using HILIC or reversed-phase chromatography

- Data Processing: Extract ion intensities and correct for natural isotope abundance

- Pool Size Quantification: Calculate absolute concentrations using standard curves

- Conservation Validation: Statistically test predicted conservation relationships

This experimental approach generates time-series metabolomic data that can be visualized using tools like GEM-Vis to dynamically track moiety conservation relationships across metabolic networks [24].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Moiety Conservation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| ¹³C-labeled Glucose | Isotopic tracer for central carbon metabolism | Tracing ATP/ADP/AMP conservation through glycolytic metabolism |

| ¹⁵N-labeled Glutamine | Amino group tracking | Analysis of transamination networks and amino moiety conservation |

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Quantification normalization | Absolute concentration determination for pool size calculations |

| Acid/Base Quenching Solutions | Rapid metabolic arrest | Preservation of in vivo metabolite concentrations |

| HILIC Chromatography Columns | Polar metabolite separation | Resolution of energy charge metabolites (ATP, ADP, AMP) |

| Cellular ATP Assay Kits | Luminometric ATP quantification | Direct measurement of adenylate energy charge |

Stoichiometric vs. Kinetic Modeling Perspectives

Comparative Analysis of Modeling Approaches

The integration of moiety conservation principles differs significantly between stoichiometric and kinetic modeling frameworks, with important implications for their application in metabolic research:

Table 4: Moiety Conservation in Stoichiometric vs. Kinetic Modeling

| Aspect | Stoichiometric Modeling | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Representation | Implicit through stoichiometric matrix structure | Explicit as algebraic constraints or dynamic pools |

| Time Dimension | Steady-state assumption (dX/dt = 0) | Explicit time dependence (dX/dt = S·v) |

| Constraint Implementation | Flux balance constraints (S·v = 0) | Combined differential and algebraic equations |

| Parameter Requirements | Only stoichiometric coefficients | Kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) and initial concentrations |

| Computational Complexity | Linear programming problems | Nonlinear differential equation systems |

| Applications | Genome-scale network analysis, flux prediction | Dynamic response prediction, metabolic engineering |

Implementation in Genome-Scale Models

The practical implementation of moiety conservation in genome-scale models requires careful consideration of network topology and thermodynamic constraints. The following diagram illustrates how moiety conservation principles integrate into metabolic modeling workflows:

Diagram 2: Integration of moiety conservation in metabolic modeling frameworks.

In stoichiometric modeling approaches, conserved moieties create dependencies that reduce the rank of the stoichiometric matrix, influencing the solution space for flux balance analysis. For kinetic models, particularly those developed using the ORACLE framework for E. coli and P. putida, moiety conservation relationships reduce system dimensionality and stabilize numerical integration of differential equations [22] [23]. This enables more reliable prediction of metabolic responses to genetic modifications and environmental perturbations.

Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

Industrial Biotechnology Applications

In industrial biotechnology, moiety conservation analysis enables more robust design of microbial cell factories for biochemical production. Key applications include:

- Redox Balance Optimization: Identification of NAD(P)H conservation relationships to optimize reduced product synthesis

- Energy Management: Analysis of adenylate energy charge to engineer ATP-regenerating systems

- Pathway Thermodynamics: Elimination of thermodynamically infeasible pathways in synthetic route design

The development of large-scale kinetic models for Pseudomonas putida demonstrates how moiety conservation analysis contributes to metabolic engineering strategies for improved biochemical production [23]. These models successfully predicted metabolic responses to single-gene knockouts and identified interventions for improved robustness to increased ATP demand.

Biomedical Research Applications

In biomedical research and drug development, moiety conservation principles facilitate:

- Drug Target Identification: Essential metabolic functions with strong conservation constraints represent promising targets

- Toxicology Assessment: Detection of disrupted conservation relationships as indicators of metabolic toxicity

- Tissue-Specific Modeling: Development of accurate tissue-specific models for human metabolic diseases

The standardization of human metabolic stoichiometric models represents a critical challenge for effective application of moiety conservation analysis in biomedical research [2]. Consistent model structures and reconstruction methods are essential for comparing results across studies and identifying clinically relevant metabolic dependencies.

The analysis of chemical moiety conservation and its relationship to metabolic network topology provides a fundamental framework for understanding biochemical systems. The integration of these principles into both stoichiometric and kinetic modeling approaches enables more accurate prediction of metabolic behavior and more rational design of metabolic engineering interventions. As modeling capabilities advance toward whole-cell simulations, the consistent application of moiety conservation constraints will remain essential for maintaining thermodynamic feasibility and biological relevance in metabolic models. The continued development of computational tools and experimental methods for validating conservation relationships represents a critical frontier in systems biology and metabolic engineering.

The Critical Steady-State Assumption in Constraint-Based Analysis

Constraint-based modeling, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), has emerged as a fundamental mathematical approach for analyzing metabolic capabilities in genome-scale networks. This technical guide examines the critical steady-state assumption underpinning these methodologies, contrasting it with kinetic modeling paradigms. We explore how the steady-state condition enables computational tractability for large-scale networks by eliminating the need for kinetic parameters while maintaining stoichiometric, thermodynamic, and physiological constraints. The formalization ( N \cdot v = 0 ) provides a powerful framework for predicting metabolic behavior, optimizing bioprocesses, and identifying therapeutic targets, despite inherent limitations in capturing dynamic metabolic responses.

The genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) represents a significant achievement in systems biology, compiling all known metabolic reactions of an organism along with their genetic associations [25] [26]. These networks provide quantitative predictions of cellular phenotypes by mathematically simulating metabolite flow. Two predominant approaches have emerged for analyzing these networks: kinetic modeling and constraint-based modeling [27]. Kinetic models simulate changes in metabolite concentrations over time by incorporating biochemical network stoichiometry, mechanistic reaction rate laws, kinetic parameters, and enzyme concentrations [27]. While offering high resolution of dynamic behavior, kinetic modeling faces significant challenges in parameter estimation and computational complexity when applied to genome-scale systems [22] [27].

In contrast, constraint-based modeling employs steady-state analysis to infer metabolic flux distributions without requiring detailed kinetic information [25] [27]. This approach relies on the fundamental observation that metabolic networks rapidly achieve quasi-steady states under homeostatic conditions, wherein metabolite concentrations remain relatively constant despite ongoing metabolic activity [27]. The critical steady-state assumption formalizes this observation mathematically, enabling researchers to bypass the significant challenges associated with determining kinetic parameters while maintaining stoichiometric and thermodynamic consistency [22] [27]. This guide examines the implementation, applications, and limitations of this foundational assumption within the broader context of metabolic modeling paradigms.

Mathematical Foundation of the Steady-State Assumption

Formal Representation of Metabolic Steady-State

The core mathematical principle underlying constraint-based analysis is the steady-state mass balance, which posits that for each intracellular metabolite in the system, the rate of production equals the rate of consumption [25] [27]. This condition is formalized using the stoichiometric matrix ( N ) and flux vector ( v ):

[ N \cdot v = \frac{dx}{dt} \approx 0 ]

Where ( N ) represents the stoichiometric matrix (with metabolites as rows and reactions as columns), ( v ) denotes the flux vector (containing all reaction rates in the network), and ( \frac{dx}{dt} ) represents the change in metabolite concentrations over time [27]. The steady-state assumption reduces this to:

[ N \cdot v = 0 ]

This equation constitutes the fundamental constraint in Flux Balance Analysis, ensuring that the sum of fluxes producing each metabolite equals the sum of fluxes consuming it, thus preventing metabolite accumulation or depletion [25] [27].

The Underdetermined Nature of Metabolic Networks

The system of equations described by ( N \cdot v = 0 ) is typically underdetermined, containing more unknown fluxes (variables) than mass balance constraints (equations) [25]. The number of unknown fluxes is ( r - \text{rank}(N) ), where ( r ) represents the total number of reactions in the network. This underdetermination means that infinitely many flux distributions satisfy the steady-state condition, necessitating additional constraints and optimization criteria to identify biologically relevant solutions [25] [27].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Components in Constraint-Based Modeling

| Component | Symbol | Description | Role in Steady-State Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix | ( N ) | ( m \times r ) matrix where entries represent stoichiometric coefficients | Defines network connectivity and mass balance constraints |

| Flux Vector | ( v ) | ( r \times 1 ) vector of reaction rates | Variables to be determined subject to constraints |

| Nullspace | ( \text{Ker}(N) ) | Set of all vectors satisfying ( N \cdot v = 0 ) | Contains all feasible steady-state flux distributions |

| Exchange Fluxes | ( v_{ext} ) | Subset of ( v ) representing metabolite uptake/secretion | Connects intracellular and extracellular environments |

| Capacity Constraints | ( \alphai \leq vi \leq \beta_i ) | Lower and upper bounds for reaction fluxes | Incorporates enzyme capacity and thermodynamic constraints |

Methodological Framework for Constraint-Based Analysis

Fundamental Workflow for Steady-State Analysis

The implementation of constraint-based methods follows a systematic workflow that leverages the steady-state assumption:

Network Reconstruction: Compile all metabolic reactions, genes, enzymes, and metabolites based on genomic and biochemical data [25] [26]. This semi-automatic process involves manual refinement, including the removal of dead-end metabolites [25].

Stoichiometric Matrix Construction: Formalize the metabolic network as a stoichiometric matrix where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions [27]. Metabolites consumed in a reaction receive negative coefficients, while produced metabolites receive positive coefficients [27].

Application of Constraints: Incorporate additional physiological constraints through inequality expressions that define lower and upper boundaries for reaction fluxes [27]. These boundaries can be inferred from experimental measurements and reflect enzyme capacity or thermodynamic reversibility [27].

Objective Function Definition: Identify a biologically relevant objective to optimize, such as biomass production, ATP synthesis, or substrate uptake minimization [25] [27]. The assumption that cells evolve toward optimality provides a biological rationale for this mathematical optimization [27].

Flux Distribution Calculation: Solve the linear programming problem to find a flux distribution that satisfies all constraints while optimizing the objective function [25].

Advanced Methodologies Extending Basic FBA

The basic FBA framework has been extended with several sophisticated methodologies that maintain the steady-state assumption while enhancing analytical capabilities:

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Determines the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal or near-optimal objective function values [25] [27]. FVA identifies reactions with fixed flux values (essential reactions) and those with flexible fluxes, providing insights into network redundancy and robustness [25].

Parsimonious FBA (pFBA): Finds flux distributions that achieve optimal growth while minimizing the total sum of absolute flux values, based on the principle that cells have evolved to achieve metabolic objectives efficiently [25].

Geometric FBA: Identifies a unique optimal flux distribution positioned centrally within the range of possible fluxes, providing a representative solution from the space of alternative optima [25].

Flux Sampling: Utilizes Monte Carlo methods to uniformly sample the steady-state flux space, enabling statistical analysis of metabolic capabilities without presupposing an objective function [25].

Table 2: Advanced Constraint-Based Methods Utilizing Steady-State Assumption

| Method | Key Principle | Solution Type | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Optimization of biological objective function | Single flux distribution | Prediction of wild-type phenotypes |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | Determination of flux ranges at optimum | Minimum and maximum flux values | Identification of essential and flexible reactions |

| Parsimonious FBA (pFBA) | Minimization of total flux while maintaining objective | Single flux distribution | Prediction of evolved or efficient flux states |

| Geometric FBA | Identification of central solution in flux ranges | Single flux distribution | Representative solution from alternative optima |

| Flux Sampling | Uniform sampling of feasible flux space | Population of flux distributions | Statistical analysis of network capabilities |

| Thermodynamic-based Flux Analysis (TFA) | Integration of thermodynamic constraints | Thermally feasible flux distributions | Elimination of thermodynamically infeasible pathways |

Comparative Analysis: Constraint-Based vs. Kinetic Modeling

Fundamental Differences in Approach and Assumptions

The steady-state assumption in constraint-based modeling presents a fundamentally different approach to metabolic analysis compared to kinetic modeling:

Constraint-based modeling leverages the steady-state assumption to enable genome-scale analyses with minimal parameter requirements [27]. The methodology focuses on stoichiometric constraints, thermodynamic feasibility, and physiological boundaries to define a space of possible metabolic states [27]. Solutions are typically obtained through linear programming optimization, with the most common objective being biomass maximization to simulate growth [25] [27].

In contrast, kinetic modeling employs ordinary differential equations to describe metabolic dynamics:

[ \frac{dx}{dt} = S \cdot v(x,p) ]

Where ( S ) represents the stoichiometric matrix, ( v(x,p) ) denotes kinetic rate laws dependent on metabolite concentrations ( x ) and parameters ( p ) [27]. This approach precisely captures transient metabolic behaviors but requires extensive parameterization often unavailable for genome-scale applications [22] [27]. Kinetic models remain limited to small-scale networks due to the scarcity of kinetic parameters and computational challenges associated with integrating large sets of differential equations [27].

Practical Implications for Metabolic Research

The choice between modeling approaches involves significant trade-offs that impact research capabilities:

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Modeling Approaches in Metabolic Research

| Characteristic | Constraint-Based Modeling | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| System Scale | Genome-scale (775+ reactions demonstrated) [23] | Small to medium networks (typically <100 reactions) [27] |

| Time Resolution | Steady-state (no dynamics) | Dynamic transients and steady states |

| Parameter Requirements | Stoichiometry, flux boundaries | Kinetic constants, enzyme concentrations |

| Computational Complexity | Linear programming (tractable) | Nonlinear ODEs (computationally challenging) |

| Regulatory Integration | Limited to constraints (e.g., enzyme capacity) | Direct incorporation of mechanisms |

| Uncertainty Handling | Flux variability analysis | Parameter sensitivity analysis |

| Primary Applications | Gene essentiality, pathway analysis | Metabolic responses, enzyme engineering |

The ORACLE framework represents an advanced approach that constructs large-scale kinetic models while maintaining stoichiometric, thermodynamic, and physiological constraints [22] [23]. This methodology generates populations of kinetic models consistent with available data and constraints, addressing the uncertainty in kinetic parameters while enabling dynamic simulations [23]. Studies on Pseudomonas putida KT2440 demonstrate how this framework can predict metabolic responses to genetic perturbations and design engineering strategies for improved biochemical production [23].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol for Steady-State Flux Analysis

Implementing constraint-based analysis with steady-state assumptions involves these critical methodological steps:

Strain Cultivation and Physiological Measurements: Grow the target organism under defined conditions and measure uptake and secretion rates. For example, cultivate Pseudomonas putida in minimal media with glucose carbon source, measuring glucose uptake rate and biomass formation [23].

Metabolite Concentration Assays: Quantify intracellular metabolite concentrations using LC-MS or GC-MS platforms. Critical metabolites include ATP, NADH, and central carbon metabolism intermediates [23].

Stoichiometric Model Curation: Perform thermodynamic curation of the genome-scale model by estimating standard Gibbs energy of formation for metabolites and adjusting for physiological pH and ionic strength [23]. Eliminate thermodynamically infeasible cycles [23].

Constraint Implementation: Apply measured uptake rates as constraints on exchange fluxes. Incorporate measured metabolite concentrations to calculate transformed Gibbs free energy of reactions and set directionality constraints [23].

Flux Calculation and Validation: Perform FBA with appropriate objective function (e.g., biomass maximization). Compare predictions to experimental growth rates and byproduct secretion profiles [23].

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Constraint-Based Metabolic Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis | MATLAB | Comprehensive suite for FBA, FVA, gene deletions [25] |

| cobrapy | Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis | Python | Python implementation of COBRA methods [25] |

| Escher-FBA | Interactive Flux Balance Analysis | Web Application | Visualization of flux distributions on metabolic maps [25] |

| ORACLE Framework | Kinetic model construction | MATLAB/Python | Builds kinetic models satisfying stoichiometric/thermodynamic constraints [22] [23] |

| Group Contribution Method | Thermodynamic parameter estimation | Standalone/Web | Estimates standard Gibbs energies for metabolites [23] |

| Thermodynamics-based Flux Analysis (TFA) | Integration of thermodynamic constraints | MATLAB | Eliminates thermodynamically infeasible flux solutions [23] |

Applications and Case Studies

Predictive Phenotyping and Gene Essentiality Analysis

The steady-state assumption enables genome-scale prediction of gene essentiality and mutant phenotypes. Implementation involves:

In Silico Gene Deletion: Remove reactions associated with target genes from the model by setting their fluxes to zero [25].

Viability Assessment: Perform FBA to determine if the mutant model can achieve non-zero growth under defined conditions [25].

Flux Redistribution Analysis: Examine how the deletion forces redistribution of fluxes through alternative pathways [23].

In a study of Pseudomonas putida KT2440, kinetic models constructed with steady-state and thermodynamic constraints successfully captured metabolic responses to single-gene knockouts, validating the predictive capability of this approach [23].

Metabolic Engineering and Strain Design

Constraint-based methods with steady-state assumptions facilitate rational metabolic engineering:

Intervention Identification: Use optimization methods like OptKnock to identify gene knockout strategies that couple growth with product formation [25].