Strategic Host Organism Selection for Microbial Cell Factories: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomanufacturing and Drug Development

Selecting the optimal microbial host is a critical, multi-factorial decision that determines the success of biomanufacturing processes for pharmaceuticals and chemicals.

Strategic Host Organism Selection for Microbial Cell Factories: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomanufacturing and Drug Development

Abstract

Selecting the optimal microbial host is a critical, multi-factorial decision that determines the success of biomanufacturing processes for pharmaceuticals and chemicals. This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of host evaluation, advanced methodological tools for engineering and application, strategies for troubleshooting the universal growth-production trade-off, and rigorous validation techniques. By integrating the latest advances in systems metabolic engineering, dynamic control, and broad-host-range synthetic biology, this guide serves as a strategic resource for developing efficient, scalable, and economically viable microbial cell factories.

The Host Selection Landscape: From Core Principles to Emerging Chassis

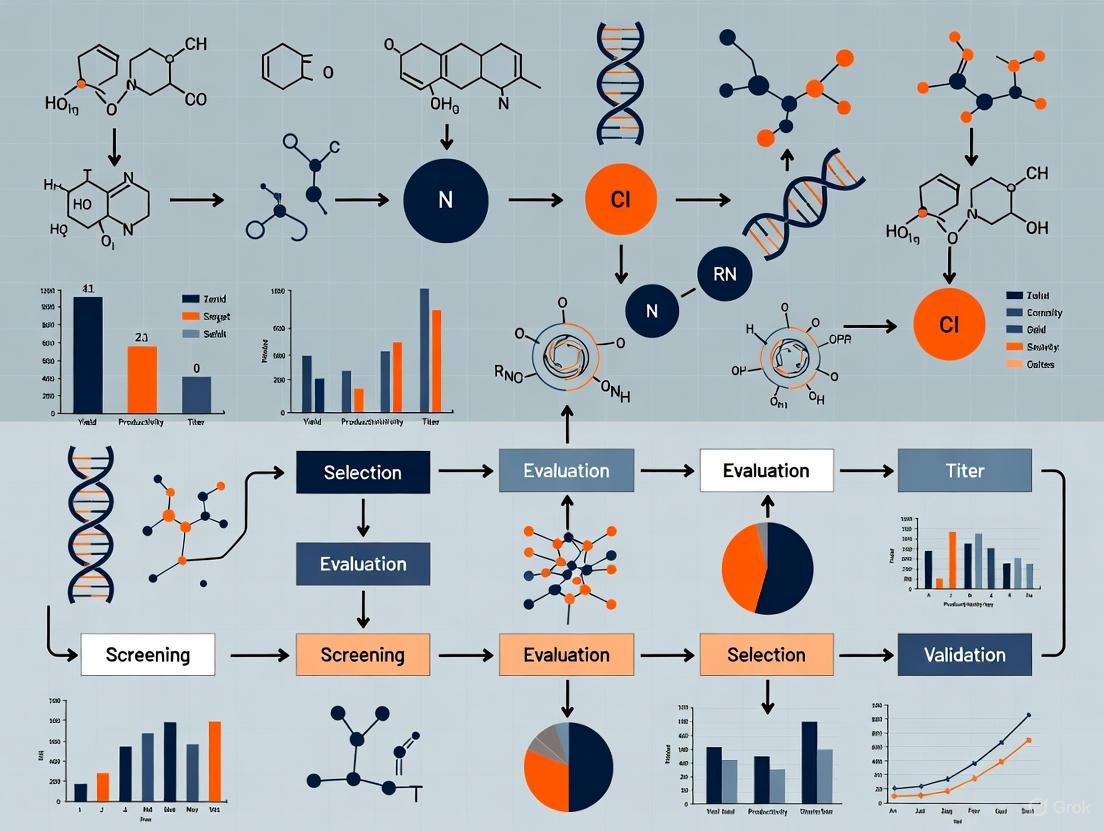

In the development of microbial cell factories (MCFs), the selection of an optimal host organism is a foundational decision that fundamentally shapes the entire bioprocess. This selection process requires rigorous quantitative evaluation based on three key performance metrics: titer, yield, and productivity. Collectively referred to as TRY, these parameters form the essential trifecta for assessing the economic viability and technical feasibility of biomanufacturing processes [1] [2]. The integration of systems metabolic engineering—which combines tools from synthetic biology, systems biology, and evolutionary engineering—has accelerated the development of high-performing microbial cell factories [3]. However, constructing an efficient microbial cell factory still requires exploring and selecting various host strains, a process demanding significant time, effort, and costs [3].

The economic implications of TRY metrics are substantial, as substrate costs alone represent 40-60% of the total production expenses in industrial biotechnology [4]. Furthermore, the shift toward second-generation feedstocks, such as lignocellulosic biomass, introduces additional complexity with inhibitor compounds and mixed sugar compositions, making the objective assessment of host performance even more critical [4]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core metrics, their interrelationships, measurement methodologies, and their pivotal role in selecting microbial production hosts within industrial bioprocess development.

Defining the Core Metrics

Quantitative Definitions and Calculations

The table below summarizes the fundamental definitions, standard units, and calculation methods for the three core bioprocess metrics.

Table 1: Core Bioprocess Evaluation Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Standard Units | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titer | Concentration of product accumulated in the bioreactor | g/L, mg/L | Measured concentration at harvest or endpoint |

| Yield | Efficiency of substrate conversion into product | g product/g substrate, mol/mol | (Total product mass)/(Total substrate consumed) |

| Productivity | Rate of product formation per unit volume | g/L/h, kg/m³/day | (Total product mass)/(Reactor volume × Time) |

Titer represents the concentration of the product accumulated in the bioreactor at the end of a fermentation process, typically measured in grams per liter (g/L) [5]. For example, in fed-batch fermentation of Pichia pastoris, a final titer of 3.7 g/L might be achieved after a 6-day campaign [5]. This metric is particularly crucial for downstream processing, as higher titers generally reduce purification costs and volume handling requirements.

Yield quantifies the efficiency of substrate conversion into the desired product [1]. It can be expressed in multiple formats, including mass yield (g product/g substrate) or molar yield (mol product/mol substrate) [3]. In metabolic engineering, two yield concepts are particularly important: the maximum theoretical yield (Yₜ), determined solely by reaction stoichiometry, and the maximum achievable yield (Yₐ), which accounts for cellular maintenance and growth requirements [3]. For instance, Saccharomyces cerevisiae shows a maximum theoretical yield of 0.8571 mol/mol glucose for l-lysine production under aerobic conditions [3].

Productivity (or volumetric productivity) measures the rate of product formation per unit reactor volume per unit time (e.g., g/L/h) [2]. A related metric, space-time yield (STY), is defined as the total mass of protein produced per bioreactor working volume per cultivation day, providing a normalized metric particularly valuable for comparing different cultivation modes [5] [6]. For example, continuous fermentation processes can achieve significantly higher space-time yields than fed-batch processes—13 grams of harvested protein over 12 days compared to 3.7 grams in 6 days for P. pastoris [5].

Advanced Yield Concepts in Metabolic Engineering

Table 2: Advanced Yield Concepts in Metabolic Engineering

| Concept | Definition | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Theoretical Yield (Yₜ) | Maximum production per carbon source when resources are fully used for target chemical production | Stoichiometric calculation ignoring metabolic fluxes toward growth and maintenance |

| Maximum Achievable Yield (Yₐ) | Maximum production per carbon source considering cell growth and maintenance | More realistic yield prediction accounting for cellular resource allocation |

| Substrate-Specific Productivity (SSP) | Productivity normalized to substrate consumption | Strain design evaluation, though limited as it doesn't fully capture volumetric productivity |

The Interrelationship of TRY Metrics

Fundamental Trade-Offs and Optimization Challenges

In practice, significant trade-offs in the TRY space must be addressed, as these metrics cannot be simultaneously maximized [1] [2]. The fundamental challenge arises from the cellular resource allocation dilemma: for a given substrate uptake rate, a higher growth yield typically leads to a higher growth rate but at the expense of product yield [1]. This creates an inherent tension between biomass production and product formation.

The development of the Dynamic Strain Scanning Optimization (DySScO) strategy specifically addresses these trade-offs by integrating dynamic flux balance analysis (dFBA) with existing strain design algorithms [2]. This approach recognizes that constrained by the yield trade-off, previous strain-design efforts often prioritized product yield optimization by restricting the growth rate to an arbitrarily low level [2]. However, this strategy can be counterproductive, as "a strain with a reduced growth rate would yield lower biomass concentration in bioreactors, which may reduce the volumetric productivity despite the increase in product yield" [2].

Diagram 1: TRY Trade-offs in Metabolism

Gene Expression Impact on TRY Space

The relationship between gene expression levels and TRY metrics reveals another critical dimension of these trade-offs. Research shows that "at low expression levels, gene transcription mainly defined TRY, and gene translation had a limited effect; whereas, at high expression levels, TRY depended on the product of both" [1]. This has significant implications for host engineering, as the optimal expression strategy varies depending on the desired production level.

Diagram 2: Multi-scale Factors Affecting TRY

Experimental Protocols for Metric Evaluation

Laboratory-Scale Bioprocess Evaluation

Accurate determination of TRY metrics requires standardized cultivation protocols and analytical methods. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive approach for evaluating host performance at laboratory scale:

Fermentation Setup: Cultivations are typically performed in bioreactors with controlled temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and feeding strategies [7]. Both batch and fed-batch fermentations are commonly carried out in fully anaerobic or controlled aerobic conditions, depending on the microbial host and metabolic pathway requirements [2]. Initial biomass is typically set to 0.01 g/L, with initial glucose concentration of 20 mM (or other carbon source) and initial liquid volume of 1L for standardized screening [2].

Process Monitoring: Regular sampling throughout the fermentation tracks biomass growth (optical density or dry cell weight), substrate consumption (HPLC, GC), and product formation (HPLC, GC, MS) [8]. Advanced microbioreactor platforms like the Biolector system enable online monitoring of biomass, dissolved oxygen, and pH in microtiter plates, allowing for high-throughput screening [8]. These systems can be fully integrated into liquid-handling platforms enclosed in laminar airflow housing for automated cultivation and sampling [8].

Analytical Measurements:

- Biomass: Dry cell weight (DCW) determined by filtering known culture volume through pre-weighed filters, drying at 80°C until constant weight [4]

- Substrate and Product Concentrations: HPLC with refractive index or UV detection for sugars, organic acids; GC-MS for volatile compounds [4] [8]

- Metabolite Analysis: Targeted metabolomics platforms for quantifying extracellular metabolites above 0.1 g/L threshold [4]

Data Analysis:

- Titer: Maximum product concentration measured at harvest

- Yield: Total product divided by total substrate consumed

- Productivity: Total product divided by (reactor volume × fermentation time)

Dynamic Strain Scanning Optimization (DySScO) Protocol

The DySScO strategy represents an advanced integrated approach for designing microbial strains with balanced TRY properties [2]. This methodology consists of three major phases broken down into nine algorithmic steps:

Table 3: DySScO Strategy Workflow

| Phase | Step | Description | Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning | 1 | Find production envelope for desired product | COBRA Toolbox, FBA |

| 2 | Create N hypothetical flux distributions | Pareto frontier sampling | |

| 3 | Perform dynamic simulations of hypothetical strains | dFBA, DyMMM framework | |

| 4 | Evaluate performance using Y, T, P | CSP = W₁·Y/Yₘₐₓ + W₂·T/Tₘₐₓ + W₃·P/Pₘₐₓ | |

| 5 | Select optimal growth rate range | Based on CSP ranking | |

| Design | 6 | Find high-yield strain designs in optimal range | OptKnock, GDLS, OptReg |

| 7 | Simulate dynamic behaviors of designed strains | dFBA | |

| 8 | Evaluate performances of designed strains | CSP calculation | |

| Selection | 9 | Select best strain design | Highest CSP |

This protocol explicitly acknowledges that "while existing algorithms can optimize the product yield of the strain, they cannot optimize the productivity and titer of the strain because they are process-level concepts and cannot be predicted using standard metabolic models" [2]. By integrating dFBA simulations with strain design algorithms, DySScO enables simultaneous optimization of all three metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for TRY Evaluation

| Category | Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioreactor Systems | Microbioreactor Platforms | High-throughput cultivation with online monitoring | Biolector system integrated with liquid-handling robotics [8] |

| Laboratory-scale Bioreactors | Controlled environment for process optimization | 1-20L systems with temperature, pH, DO control [7] | |

| Analytical Instruments | HPLC Systems | Quantification of substrates, metabolites, products | RI or UV detection, Aminex HPX-87H column for organic acids [4] |

| GC-MS Systems | Analysis of volatile compounds and gases | Suitable for fermentation inhibitors (furfural, HMF) [4] | |

| Spectrophotometer | Biomass measurement (OD600) | Integrated in microbioreactor platforms [8] | |

| Software & Databases | Constraint-Based Modeling Tools | Metabolic flux analysis and strain design | COBRA Toolbox, FBA, dFBA [2] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Host selection and pathway analysis | GEMs for E. coli, S. cerevisiae, B. subtilis, etc. [3] | |

| Strain Engineering Tools | CRISPR Systems | Genome editing for strain optimization | Cas9-based editing for gene knockouts [3] |

| Pathway Construction Tools | Heterologous pathway assembly | Golden Gate, Gibson assembly [9] |

Application in Host Organism Selection

Metabolic Capacity Evaluation Framework

Selecting the optimal microbial production host requires a systematic evaluation of metabolic capabilities relative to target products. The comprehensive evaluation of microbial cell factories involves calculating both maximum theoretical yield (Yₜ) and maximum achievable yield (Yₐ) for target chemicals across different host organisms [3]. This analysis can be performed for various carbon sources (e.g., glucose, xylose, glycerol) under different aeration conditions (aerobic, microaerobic, anaerobic) [3].

For example, when evaluating five representative industrial microorganisms (Bacillus subtilis, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas putida, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) for production of 235 different bio-based chemicals, researchers found that "while most chemicals achieve their highest yields in S. cerevisiae, a few chemicals display clear host-specific superiority" [3]. These findings highlight the necessity of evaluating each chemical individually rather than applying universal rules for host selection.

Second-Generation Feedstock Considerations

The transition from first-generation to second-generation feedstocks introduces additional complexity in host selection. Lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysates contain mixed sugars (glucose, xylose, arabinose, galactose, mannose) and various inhibitors (furfural, HMF, acetic acid, salts) that significantly impact microbial performance [4]. A comparative study of six industrially relevant microorganisms (E. coli, C. glutamicum, S. cerevisiae, Pichia stipitis, Aspergillus niger, and Trichoderma reesei) revealed "large differences in the performance" related to "carbon source versatility and inhibitor resistance" [4].

Notably, the study found that "fungi were more resistant to the tested inhibitors than the other host organisms," with P. stipitis and A. niger providing the overall best performance on renewable feedstocks [4]. This supports the conclusion that "a substrate oriented instead of the more commonly used product oriented approach towards the selection of a microbial production host will avoid the requirement for extensive metabolic engineering" [4].

The systematic evaluation of titer, yield, and productivity provides an essential framework for selecting and engineering microbial cell factories. These interdependent metrics collectively determine the economic viability of bioprocesses, with optimal host selection requiring careful consideration of the inherent trade-offs between them. The ongoing development of advanced tools—including genome-scale metabolic models, dynamic flux balance analysis, high-throughput screening platforms, and sophisticated strain design algorithms—continues to enhance our ability to rationally engineer microbial hosts with balanced TRY characteristics.

As the field progresses toward more complex second-generation feedstocks and novel bioproducts, the fundamental principles of TRY optimization remain central to successful bioprocess development. By applying the methodologies and frameworks outlined in this technical guide, researchers can make more informed decisions in host selection and strain engineering, ultimately accelerating the development of sustainable microbial cell factories for industrial applications.

The selection of an appropriate host organism is a foundational decision in microbial cell factory research, with profound implications for the success of bioproduction processes. For decades, Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Bacillus subtilis have served as the principal workhorses of industrial biotechnology. Each organism possesses a unique combination of physiological traits, genetic backgrounds, and operational advantages that make them suitable for specific applications. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical comparison of these three model systems, focusing on their respective strengths, limitations, and ideal use cases in biomanufacturing. By synthesizing current research and experimental data, we aim to equip researchers with the analytical framework necessary for informed host selection in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology projects. The growing emphasis on sustainable bioprocessing and the expansion of synthetic biology tools have further solidified the importance of these organisms, while also highlighting their specialized roles in the evolving landscape of industrial microbiology.

Organism Profiles and Key Characteristics

Core Biological Attributes

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and B. subtilis

| Characteristic | Escherichia coli | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Bacillus subtilis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomy | Gram-negative bacterium | Ascomycete fungus (Yeast) | Gram-positive bacterium |

| Native Habitat | Mammalian gastrointestinal tract | Various natural niches (e.g., fruit, plants) | Soil, plant roots, gastrointestinal tracts |

| Regulatory Status | Varies by strain; some lab strains approved for specific products | Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) | Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) [10] [11] [12] |

| Growth Rate | Very fast (doubling time ~20 min) | Moderate (doubling time ~90 min) | Fast (doubling time ~30 min) [10] |

| Oxygen Requirement | Facultative anaerobe | Facultative anaerobe | Obligate aerobe [13] |

| Secretion Capability | Limited; outer membrane barrier | Limited; primarily periplasmic | Excellent; high-capacity secretion into medium [10] [11] |

| Genome Size | ~4.6 Mbp | ~12 Mbp | ~4.2 Mbp [10] |

| Gene Number | ~4,300 (K-12) | ~6,000 | ~4,100 (strain 168) [10] |

Industrial and Biotechnological Applications

Table 2: Comparative industrial applications and product profiles

| Application Area | E. coli | S. cerevisiae | B. subtilis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Proteins | Excellent for intracellular expression; widely used for therapeutics (e.g., insulin, growth hormones) | Suitable for secreted and intracellular proteins; performs eukaryotic post-translational modifications | Ideal for secreted enzymes; dominant host for industrial enzymes (amylases, proteases) [10] [11] |

| Metabolic Engineering | Platform for organic acids, biofuels (e.g., isobutanol), polymer precursors, and complex natural products | Platform for biofuels (ethanol, advanced biofuels), organic acids, and pharmaceutical precursors (e.g., artemisinin) | Platform for vitamins (e.g., riboflavin B2), bio-based chemicals, and functional peptides [10] [13] |

| Specialty Applications | - | Surface display for biocatalysis and biosensing; food and beverage fermentation | Surface display (spores and vegetative cells) for biocatalysis, vaccines, and biosensing [11] |

| Food & Feed Products | Limited direct use | Fermented foods, baking, nutritional supplements | Probiotics, fermented foods (e.g., natto), direct-fed microbes [12] |

Genetic and Metabolic Features

Genomic Architecture and Evolutionary History

The evolutionary histories of these model organisms have significantly shaped their genomic architectures and metabolic capabilities. E. coli exhibits remarkable genomic stability, with approximately 87.0% of its genes belonging to the evolutionarily oldest phylostratum, indicating a core genome heavily enriched for essential cellular functions [14]. In contrast, B. subtilis demonstrates a more dynamic evolutionary past, with only 71.8% of its genes classified in the oldest category, reflecting a greater propensity for horizontal gene transfer and gene emergence [14]. This characteristic may contribute to B. subtilis's metabolic versatility and environmental adaptability. S. cerevisiae, with its eukaryotic genome organization, possesses a complex regulatory architecture featuring introns, extensive transcriptional regulation, and compartmentalized metabolism.

Metabolic Network Properties

The metabolic capabilities of these organisms are formally represented through Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (M-models), which have been instrumental in guiding metabolic engineering strategies. For B. subtilis, the development of next-generation Metabolism and Gene Expression models (ME-models) such as iJT964-ME has enabled more accurate predictions of proteomic responses to stress and protein overproduction capabilities [15]. This ME-model contains 964 genes, 6,282 reactions, and 4,208 metabolites, explicitly linking enzyme production costs to metabolic fluxes [15]. Similarly, sophisticated models exist for E. coli (e.g., iJL1678b-ME) and S. cerevisiae (e.g., Yeast8), allowing for comparative in silico analysis of metabolic capabilities and engineering targets.

Figure 1: Logical framework for host organism selection based on fundamental biological characteristics and application requirements.

Synthetic Biology Tools and Engineering Methodologies

Genetic Manipulation Tools

The genetic tractability of all three organisms has been significantly enhanced by the development of advanced synthetic biology tools:

CRISPR-Based Systems: CRISPR technologies have been successfully implemented in all three platforms for gene knockouts, transcriptional regulation (CRISPRi), and base editing. A modified CRISPRi system using partially mismatched sgRNAs has been applied to titrate essential gene expression in both E. coli and B. subtilis, revealing conserved expression-fitness relationships between homologous genes despite ~2 billion years of evolutionary separation [16].

Specialized Toolkits: Platform-specific genetic toolkits have been developed to standardize and accelerate engineering workflows. The SubtiToolKit (STK) provides a standardized Golden Gate assembly system for B. subtilis and other Gram-positive bacteria, enabling rapid construction of genetic circuits and pathway engineering [17]. Similar modular cloning systems exist for E. coli (e.g., EcoFlex) and S. cerevisiae (e.g., MoClo Yeast Toolkit).

Gene Editing Technologies: While CRISPR-Cas systems dominate current engineering approaches, earlier technologies like Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) continue to have specialized applications, particularly in organisms where CRISPR efficiency may be limited [18].

Surface Display Technologies

B. subtilis offers unique capabilities through its surface display technology, which utilizes both vegetative cells and spores for presenting target proteins on the cellular surface [11]. This system employs various anchor proteins, including transmembrane proteins, lipoproteins, and LPXTG-like proteins for cell surface display, and spore coat proteins (CotB, CotC, CotG, CotX) for spore display [11]. The remarkable resilience of B. subtilis spores to harsh conditions (heat, dehydration, UV exposure) enhances the stability of displayed proteins, making this platform particularly valuable for applications in biosensing, vaccine development, and biocatalysis under industrial conditions [11].

Table 3: Key research reagents and solutions for microbial cell factory engineering

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Organism |

|---|---|---|

| SubtiToolKit (STK) | Standardized Golden Gate assembly system for genetic parts | B. subtilis, Gram-positive bacteria [17] |

| Mismatch-CRISPRi Library | Titrated knockdown of essential genes using mismatched sgRNAs | E. coli, B. subtilis [16] |

| iJT964-ME Model | Metabolism and gene expression model for proteome allocation predictions | B. subtilis [15] |

| Spore Display System | Surface presentation of proteins using spore coat anchors (CotB, CotC, CotG) | B. subtilis [11] |

| Cell Surface Display | Surface presentation on vegetative cells using anchor proteins (LysM, YhcR) | B. subtilis [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: Engineering B. subtilis for Enhanced Metabolite Production

This protocol outlines the metabolic engineering workflow for enhancing production of pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (DPA) in B. subtilis, demonstrating generalizable strategies for pathway optimization [13].

Gene Disruption and Promoter Replacement:

- Design homologous recombination cassettes containing antibiotic resistance markers.

- Knock out sporulation-related genes (e.g., spo0A, spoIIE, spoIVB) to redirect metabolic flux.

- Replace native promoter of dipicolinate synthase gene (spoVF) with constitutive promoter (PyvyD) using seamless genome editing.

- Transform B. subtilis PS832 strain with editing constructs via natural competence or electroporation.

Transcriptomic Analysis:

- Culture wild-type and engineered strains in appropriate medium (e.g., LB or defined minimal medium).

- Harvest cells at mid-exponential phase (OD600 ~0.6-0.8) for RNA extraction.

- Perform RNA sequencing (Illumina platform) with triplicate biological replicates.

- Analyze differential gene expression, focusing on spore coat assembly genes and metabolic pathways.

Fermentation Optimization:

- Inoculate optimized strain (e.g., BSDYvyDVF-gerE) in shake flask cultures.

- Scale up to bioreactor (1.5 L working volume) with controlled parameters (pH 7.0, 37°C, dissolved oxygen >30%).

- Implement fed-batch strategy with carbon source feeding during stationary phase.

- Monitor biomass (OD600) and DPA production over 72-96 hours via HPLC analysis.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for engineering high-yield metabolite production in B. subtilis [13].

Protocol: Assessing Probiotic Properties of B. subtilis Strains

This methodology provides a framework for comprehensive characterization of probiotic candidates, as demonstrated for B. subtilis YZ01 [12].

Acid and Bile Salt Tolerance:

- Prepare 16-hour B. subtilis cultures in LB broth (OD600 adjusted to ~1.0, approximately 10^8 CFU/mL).

- For acid tolerance: Transfer bacterial suspension to acidic conditions (pH 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0) using HCl acidification.

- Incubate at 37°C for 3 hours with shaking (200 rpm).

- For bile salt tolerance: Transfer bacterial suspension to LB broth containing bile salt (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 1, and 2% w/v).

- Incubate at 37°C for 5 hours with shaking.

- Serially dilute and plate on LB agar to determine surviving bacteria counts.

- Calculate survival rates: (Final log CFU/mL / Initial log CFU/mL) × 100.

Uric Acid Biodegradation Assay:

- Culture B. subtilis for 24 hours in appropriate medium.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 10 minutes) and wash twice with stroke-physiological saline solution.

- Resuspend cells in phosphate buffer solution (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4) containing uric acid (1.68 g/L).

- Incubate at 37°C for 24 hours with shaking.

- Terminate reaction by adding equal volume of 0.5 M NaOH.

- Filter mixture through 0.22-μm membrane filter.

- Quantify uric acid concentration by HPLC with standard curve (0.02-0.10 g/L).

- Calculate biodegradation ratio: (C0 - Ct)/C0 × 100%, where C0 is initial concentration and Ct is residual concentration.

Whole Genome Sequencing and Safety Assessment:

- Extract genomic DNA using commercial kit (e.g., MagPure Bacterial DNA Kit).

- Sequence on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform.

- Assemble genome using SPAdes v3.15 and annotate with Prokka v1.10.

- Screen for antibiotic resistance genes using CARD database and virulence factors using VFDB.

Comparative Performance and Industrial Implementation

Production Capabilities and Limitations

Each organism demonstrates distinct performance characteristics in industrial settings:

B. subtilis achieves remarkable success in protein secretion, making it the preferred platform for industrial enzyme production. Its GRAS status and efficient secretion machinery enable production yields exceeding 20 g/L for certain enzymes [10]. The implementation of ME-models like iJT964-ME has improved prediction of protein overproduction limits and stress responses, facilitating further yield improvements [15].

E. coli remains unmatched for intracellular production of recombinant proteins and small molecules, with well-established high-cell-density fermentation processes achieving biomass concentrations exceeding 100 g/L dry cell weight. However, its endotoxin production and limited secretion capacity present challenges for certain pharmaceutical applications.

S. cerevisiae provides the critical advantage of eukaryotic post-translational modifications, making it indispensable for producing complex eukaryotic proteins. Its industrial implementation in both traditional bioprocessing (e.g., ethanol fermentation) and modern biopharmaceutical production demonstrates remarkable versatility.

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

The continuing development of synthetic biology tools is expanding the application horizons for all three platforms:

B. subtilis is seeing increased utilization in sustainable manufacturing through surface display technologies that enable whole-cell biocatalysts for environmental remediation and green chemistry applications [11]. The development of food-grade probiotic strains with specialized functions, such as B. subtilis YZ01 for uric acid degradation, demonstrates the expanding health applications [12].

E. coli engineering continues to push the boundaries of complex molecule biosynthesis, including medicinal plant compounds and advanced biomaterials.

S. cerevisiae remains at the forefront of cell factory development for plant natural products and next-generation biofuels.

The integration of systems biology approaches, including ME-models and machine learning, across all three platforms is accelerating the design-build-test-learn cycle and enabling more predictive metabolic engineering strategies.

The comparative analysis of E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and B. subtilis reveals a complementary landscape of microbial platforms for cell factory applications. E. coli provides unparalleled growth kinetics and genetic tractability for intracellular production. S. cerevisiae offers essential eukaryotic functionality and established industrial heritage. B. subtilis delivers superior protein secretion, GRAS status, and unique capabilities in spore-based applications. The optimal host selection depends critically on the target product, required post-translational modifications, secretion needs, and regulatory considerations. Future advances will likely involve further specialization of each platform through continued tool development and systems-level understanding, ultimately expanding the boundaries of microbial manufacturing across diverse sectors including therapeutics, chemicals, and sustainable materials.

Evaluating Non-Model and Non-Canonical Hosts for Specialized Applications

The strategic selection of host organisms is a cornerstone of microbial cell factories (MCFs) research, directly influencing the efficiency, scalability, and economic viability of biomanufacturing processes. While model organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have historically dominated the field due to their well-characterized genetics and extensive engineering toolkits, their inherent limitations for specialized applications are increasingly apparent [19] [20]. This has catalyzed a paradigm shift towards exploring non-model and non-canonical hosts—microbes possessing unique, innate physiological and metabolic traits that are difficult to engineer from first principles [21] [9]. These hosts represent a vast and largely untapped reservoir of biodiversity, offering natural capabilities such as robustness under industrial conditions, tolerance to inhibitory compounds, and specialized metabolic pathways [19] [20] [9]. Framing host selection within this broader context is essential for advancing the bioeconomy, as it enables the development of more sustainable processes that utilize next-generation feedstocks, including one-carbon (C1) compounds and lignocellulosic hydrolysates [19] [20].

Promising Non-Model Hosts and Their Innate Advantages

The selection of a non-model host is profoundly dictated by the specific demands of the bioprocess and the target product. The table below summarizes several prominent non-model hosts and their key native advantages for specialized applications.

Table 1: Promising Non-Model Microbial Hosts and Their Native Characteristics

| Microbial Host | Key Native Characteristics | Potential Specialized Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Zymomonas mobilis | High ethanol tolerance and yield; unique anaerobic Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway; high sugar uptake rate [20]. | Lignocellulosic bioethanol production; platform for other biochemicals like D-lactate and 2,3-butanediol [20]. |

| Bacillus subtilis | Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status; high protein secretion capacity; proficient sporulation; clear genetic background [22]. | Industrial enzyme production; heterologous protein secretion; production of vitamins and antimicrobial peptides [22]. |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | GRAS status; natural secretion of amino acids; high flux through TCA cycle; robust under industrial conditions [3]. | Amino acid production (e.g., L-glutamate, L-lysine); organic acid synthesis; metabolic engineering chassis [3]. |

| Pseudomonas putida | Metabolic versatility and broad substrate spectrum; high tolerance to solvents and toxic compounds; robust central metabolism [3]. | Bioremediation; conversion of lignin-derived aromatics; production of biopolymers [3]. |

| Methylotrophic Bacteria | Native ability to utilize C1 substrates (e.g., methanol, methane) as carbon and energy sources [19]. | Single-cell protein; valorization of greenhouse gases into chemicals and fuels [19]. |

| Acetogens | Ability to fix CO/CO2 via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway; anaerobic fermentation of syngas [19]. | Carbon capture and utilization; conversion of syngas into biofuels (e.g., ethanol) and chemicals [19]. |

Quantitative Evaluation of Host Metabolic Capacity

A rational selection process requires a quantitative comparison of the innate metabolic capabilities of potential hosts. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are indispensable tools for this purpose, allowing in silico prediction of theoretical production yields. The following table provides a comparative analysis of the calculated metabolic capacities of five industrial microorganisms for producing key chemicals, demonstrating that the optimal host is often chemical-specific.

Table 2: Metabolic Capacity Comparison for Selected Chemicals under Aerobic Conditions with Glucose [3]

| Target Chemical | Host Organism | Maximum Theoretical Yield (YT) (mol/mol Glucose) | Maximum Achievable Yield (YA)* (mol/mol Glucose) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Lysine | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 0.857 | - |

| Bacillus subtilis | 0.821 | - | |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | 0.810 | - | |

| Escherichia coli | 0.799 | - | |

| Pseudomonas putida | 0.768 | - | |

| L-Glutamate | Corynebacterium glutamicum | - | - |

| Other Hosts | - | - | |

| Sebacic Acid | Pseudomonas putida | - | - |

| Other Hosts | - | - | |

| Propan-1-ol | Escherichia coli | - | - |

| Other Hosts | - | - |

YA accounts for non-growth-associated maintenance energy and a minimum growth requirement, providing a more realistic yield estimate than YT [3].

Engineering and Optimization Strategies for Non-Model Hosts

A Roadmap for Synthetic C1 Assimilation

Engineering non-model hosts for non-native substrate utilization, such as C1 compounds, requires a systematic workflow. The following diagram outlines the key stages, from initial bioprocess design to fermentation optimization.

Genome Reduction for Chassis Streamlining

Genome reduction is a powerful top-down approach to create streamlined and robust microbial chassis from non-model hosts [21]. This process involves the systematic deletion of non-essential genomic regions, including mobile genetic elements, pathogenicity islands, and redundant metabolic functions. The benefits are multifaceted:

- Enhanced Genomic Stability: Removal of insertion sequences (IS) and prophages reduces the frequency of random, undesirable mutations. For example, constructing an IS-free E. coli strain increased recombinant protein production by 20-25% [21].

- Improved Metabolic Efficiency: Eliminating the biosynthesis of unwanted secondary metabolites (e.g., native antibiotics) simplifies the metabolic background and redirects cellular resources toward the target product. In Streptomyces albus, deleting 15 native antibiotic gene clusters doubled the production of heterologously expressed biosynthetic pathways [21].

- Increased Transformation Efficiency: A reduced genome can alleviate the cellular burden, leading to higher competency and easier genetic manipulation [21].

The Dominant-Metabolism Compromised Intermediate-Chassis (DMCI) Strategy

A significant challenge in engineering microbes with strong native pathways (e.g., ethanol production in Zymomonas mobilis) is completely redirecting carbon flux. The DMCI strategy provides a solution by creating an intermediate chassis where the dominant metabolism is intentionally compromised [20]. This is achieved not by directly engineering for the final target product, but by introducing a less toxic, cofactor-imbalanced intermediate pathway that weakens the native flux. Subsequently, this intermediate chassis serves as a more amenable platform for constructing efficient producers of the desired biochemical. This approach enabled the engineering of Z. mobilis to produce over 140 g/L of D-lactate with a yield greater than 0.97 g/g glucose, a feat unattainable in the wild-type strain due to its overwhelming ethanol production [20].

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Engineering Non-Model Hosts

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Strain Development |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico prediction of metabolic fluxes, identification of gene knockout targets, and guidance for pathway design (e.g., iZM516 for Z. mobilis) [3] [20]. |

| Enzyme-Constrained Models (ecGEMs) | Enhanced GEMs that integrate enzyme kinetics, providing more accurate simulations of proteome-limited growth and metabolic fluxes (e.g., eciZM547) [20]. |

| CRISPR-Based Genome Editing Tools | Enables precise gene knockouts, knock-ins, and multiplexed editing, even in non-model and polyploid organisms [22] [20]. |

| Native and Synthetic Promoters | Fine-tuning of gene expression; native C1-inducible promoters are particularly valuable for regulating synthetic C1 assimilation pathways [19] [22]. |

| Plasmids and Genetic Parts | Vectors for heterologous gene expression; a library of standardized parts (RBS, terminators) is crucial for reliable genetic manipulation [21] [22]. |

| Omics Analysis Tools (Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Fluxomics) | Provides systems-level data on cellular responses, guiding rational engineering and revealing metabolic bottlenecks [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing the DMCI Strategy

The following detailed methodology outlines the key steps for applying the DMCI strategy, as demonstrated in Zymomonas mobilis for D-lactate production [20].

Systematic In Silico Pathway Analysis:

- Utilize an enzyme-constrained genome-scale model (ecGEM) like eciZM547 to simulate the dynamics of flux distribution.

- Analyze the energy (ATP) and cofactor (NADH/NADPH) balances of the native dominant pathway (e.g., ethanol production) and potential intermediate pathways (e.g., 2,3-butanediol).

- Select an intermediate pathway that introduces cofactor imbalance or mild toxicity to strategically weaken the dominant metabolism without crippling cell growth.

Construction of the Intermediate Chassis:

- Genetic Tool Application: Employ a robust genome-editing system (e.g., CRISPR-Cas12a or endogenous Type I-F CRISPR-Cas for Z. mobilis) [20].

- Pathway Integration: Assemble and integrate the genes for the selected intermediate pathway (e.g., 2,3-butanediol biosynthesis) into the host chromosome under the control of a strong constitutive promoter.

- Validation: Confirm genomic integration via PCR and sequence verification. Quantify the reduction in the dominant pathway's flux (e.g., ethanol titer) and the emergence of the intermediate product.

Engineering for the Target Product:

- In the validated intermediate chassis, introduce the heterologous pathway for the final target product (e.g., D-lactate dehydrogenase).

- Simultaneously, knockout or downregulate key enzymes in the native dominant pathway (e.g., pyruvate decarboxylase) to further minimize carbon loss.

Strain Evaluation and Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE):

- Cultivate the engineered strain in a bioreactor with minimal media and the target carbon source.

- Monitor the titers, yields, and productivities of both the target product and any by-products.

- Subject the strain to ALE under selective pressure (e.g., high substrate or product concentration) to improve growth and production characteristics.

The strategic evaluation and deployment of non-model and non-canonical hosts are imperative for the next generation of microbial cell factories. By moving beyond traditional model systems, researchers can leverage a wealth of native physiological and metabolic traits that are optimally suited for specialized applications, from C1 gas valorization to lignocellulosic biorefining. Success in this endeavor hinges on an integrated approach that combines quantitative metabolic evaluation, advanced genome engineering, and strategic chassis design principles like genome reduction and the DMCI strategy. As synthetic biology tools continue to mature for a wider range of microorganisms, the systematic development of these powerful hosts will be a key driver in establishing a sustainable, circular bioeconomy.

The Role of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) in Predicting Metabolic Capacity

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have emerged as indispensable computational tools for predicting the metabolic capacity of microorganisms, providing a robust framework for rational host organism selection in microbial cell factory development. By mathematically representing gene-protein-reaction associations, GEMs enable researchers to simulate organism metabolism under various genetic and environmental conditions, predicting metabolic fluxes and phenotypic outcomes with systems-level precision. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, reconstruction methodologies, and computational applications of GEMs, with particular emphasis on their critical role in identifying optimal microbial hosts for industrial bioproduction. We further present standardized protocols for GEM-based analysis and provide a comprehensive toolkit for implementing these approaches in strain selection and metabolic engineering pipelines.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational frameworks that systematically represent the metabolic network of an organism through gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations for nearly all metabolic genes [23]. These models integrate stoichiometric, compartmentalization, biomass composition, thermodynamic, and regulatory information to enable quantitative prediction of metabolic behavior [23]. By imposing systemic constraints on the entire metabolic network, GEMs allow researchers to simulate cellular responses to genetic modifications and environmental perturbations, providing a powerful platform for metabolic engineering and host selection [23] [24].

The reconstruction of GEMs begins with genome annotation, followed by the compilation of metabolic reactions into a stoichiometric matrix (S-matrix) where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions [24]. This matrix forms the mathematical foundation for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods, primarily flux balance analysis (FBA), which uses linear programming to predict flux distributions that optimize a cellular objective (typically biomass production) under steady-state assumptions [24] [25]. The first GEM was reconstructed for Haemophilus influenzae in 1999, and since then, GEMs have been developed for an extensive range of organisms across bacteria, archaea, and eukarya [24].

Evolution and Quality Improvements in GEM Reconstruction

Historical Development of High-Quality GEMs

The development of GEMs for model organisms has undergone continuous refinement, with successive iterations incorporating expanded reaction networks, improved annotation accuracy, and additional constraints. The trajectory of Saccharomyces cerevisiae GEMs exemplifies this evolution, beginning with the first model iFF708 in 2003 [23]. The international collaboration that produced the consensus model Yeast1 addressed inconsistencies across earlier models, and this foundation has been progressively enhanced through versions Yeast4, Yeast7, Yeast8, and the most recent Yeast9 [23] [24]. Similar progression is evident in Escherichia coli GEMs, from the initial iJE660 model to the contemporary iML1515, which contains 1,515 open reading frames and demonstrates 93.4% accuracy in gene essentiality predictions across multiple carbon sources [24].

Enhancements in Model Quality and Predictive Capability

Recent GEM versions incorporate critical improvements that significantly enhance their predictive accuracy and application scope:

- Mass and charge balance corrections eliminate thermodynamically infeasible flux solutions [23]

- Refined gene associations improve mapping between genotypes and metabolic phenotypes [23]

- Incorporation of thermodynamic parameters enables more physiologically realistic flux predictions [23]

- Pan-genome models capture metabolic diversity across multiple strains of a species [23]

For example, Yeast9 includes updates to SLIME reactions and GPR associations, while pan-GEMs-1807 was developed based on the pan-genome of 1,807 S. cerevisiae isolates, enabling the generation of strain-specific GEMs (ssGEMs) that reflect niche-specific metabolic adaptations [23]. These advancements have transformed GEMs from basic metabolic networks into sophisticated, multiscale models capable of integrating diverse omics data and predicting complex phenotypic outcomes.

GEMs in Host Organism Selection for Microbial Cell Factories

Systematic Comparison of Metabolic Capacities

The selection of optimal host organisms represents a critical initial step in developing efficient microbial cell factories. GEMs enable systematic comparative analysis of metabolic capabilities across candidate organisms, calculating key performance metrics such as maximum theoretical yield (YT) and maximum achievable yield (YA) for target biochemicals [3]. A comprehensive evaluation of five major industrial microorganisms (Bacillus subtilis, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas putida, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) demonstrated the utility of this approach, calculating yields for 235 different bio-based chemicals across nine carbon sources under varying aeration conditions [3].

Table 1: Metabolic Capacity Comparison for Representative Chemicals in Selected Host Organisms [3]

| Target Chemical | Host Organism | Maximum Theoretical Yield (mol/mol glucose) | Maximum Achievable Yield (mol/mol glucose) | Required Heterologous Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-lysine | S. cerevisiae | 0.8571 | - | - |

| L-lysine | B. subtilis | 0.8214 | - | - |

| L-lysine | C. glutamicum | 0.8098 | - | - |

| L-lysine | E. coli | 0.7985 | - | - |

| L-lysine | P. putida | 0.7680 | - | - |

| L-glutamate | C. glutamicum | - | - | Native pathway |

| Sebacic acid | E. coli | - | - | 3-5 heterologous reactions |

Strain Selection Based on Metabolic Characteristics

GEM-based analysis reveals that different host organisms exhibit distinct metabolic advantages for specific product classes. For instance, S. cerevisiae achieves the highest theoretical yield for L-lysine production (0.8571 mol/mol glucose) via the L-2-aminoadipate pathway, while other strains utilize the diaminopimelate pathway with varying efficiencies [3]. This systematic approach enables researchers to:

- Identify native producers of target chemicals, minimizing the need for extensive pathway engineering

- Determine pathway length and complexity for non-native products, with most chemicals requiring fewer than five heterologous reactions [3]

- Evaluate host compatibility with available substrates and process conditions

- Predict trade-offs between biomass formation and product synthesis

Hierarchical clustering of host performance across multiple chemicals reveals that while some organisms show broad superiority (e.g., S. cerevisiae for many chemicals under aerobic conditions), specific compounds display clear host-specific advantages that may not follow conventional biosynthetic categories [3]. This underscores the importance of chemical-specific evaluation rather than applying universal host selection rules.

Methodologies and Protocols for GEM-Based Analysis

Fundamental Workflow for GEM Reconstruction and Simulation

The standard pipeline for GEM development and application involves multiple stages, from initial genome annotation to context-specific model simulation. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow:

Protocol for Host Selection Using GEMs

Objective: Systematically identify the optimal microbial host for production of a target biochemical using GEM-based analysis.

Materials and Computational Tools:

- Genome-scale metabolic models for candidate host organisms (e.g., Yeast9 for S. cerevisiae, iML1515 for E. coli, iBsu1144 for B. subtilis)

- COBRA Toolbox or RAVEN Toolbox for MATLAB for constraint-based modeling

- Python with COBRApy package for simulation environment

- Agora2 database for gut microbes or BioModels Database for curated metabolic models

- Rhea database for biochemical reaction information

Procedure:

Model Acquisition and Validation

- Obtain high-quality GEMs for candidate host organisms from curated repositories

- Verify model functionality by simulating growth on standard media and comparing with experimental data

- Ensure mass and charge balance for all reactions

Pathway Reconstruction

- For non-native products: Identify biosynthetic pathway using biochemical databases (e.g., Rhea, KEGG)

- Add necessary heterologous reactions to host GEMs, including transport reactions

- Verify pathway functionality by maximizing product formation flux

Yield Calculation

- Constrain substrate uptake rates (e.g., glucose: 10 mmol/gDW/h)

- Set non-growth associated maintenance (NGAM) based on experimental data

- For maximum theoretical yield (YT): Optimize for product formation without growth constraints

- For maximum achievable yield (YA): Implement a minimum growth constraint (e.g., 10% of maximum growth rate) and optimize for product formation [3]

Growth Condition Screening

- Test metabolic capacity across different carbon sources (e.g., glucose, xylose, glycerol)

- Evaluate performance under varying aeration conditions (aerobic, microaerobic, anaerobic)

- Identify potential nutrient limitations or toxic byproduct accumulation

Strain Ranking and Selection

- Compare yields, growth rates, and pathway efficiency across candidates

- Evaluate genetic engineering feasibility based on pathway length and complexity

- Consider additional factors: process compatibility, safety status, available genetic tools

Advanced GEM Applications in Metabolic Engineering

Multiscale and Condition-Specific Models

Beyond basic stoichiometric modeling, advanced GEM formulations incorporate additional biological constraints to enhance predictive accuracy:

- Enzyme-constrained GEMs (ecGEMs) integrate proteomic limitations and enzyme kinetic parameters, improving predictions under conditions of resource reallocation [23]

- Metabolism and gene expression models (ME-models) couple metabolic networks with macromolecular biosynthesis, enabling proteome allocation predictions [23] [26]

- Context-specific GEMs integrate omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to generate condition-relevant metabolic networks [24]

For example, ecYeast8 incorporates enzyme abundance data, while yETFL and pcYeast represent ME-models for S. cerevisiae that successfully predict flux distributions under temperature and oxidative stresses [23] [26]. These advanced models more accurately capture metabolic trade-offs between growth and production, addressing a key limitation of classical FBA.

Strain Design and Optimization

GEMs facilitate targeted metabolic engineering through systematic identification of genetic modifications:

- Gene knockout predictions using algorithms such as OptKnock identify disruption targets that couple growth with product formation [3]

- Up/down-regulation targets pinpoint reactions whose flux modulation enhances product yields

- Cofactor engineering strategies optimize redox and energy balance for improved pathway performance

In one application, GEM-based analysis identified gene knockout targets for improved L-valine production in E. coli that would have required extensive experimental screening [3]. Similarly, model-guided identification of gene editing targets enabled overproduction of the immune-modulating metabolite butyrate in probiotic strains [26].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GEM-Based Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAVEN Toolbox | Software | Automated GEM reconstruction | Reconstruction of draft GEMs for 332 yeast species [23] |

| CarveMe | Software | Automated GEM reconstruction | Building GEMs for non-model yeasts [23] |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software | Constraint-based modeling | FBA, gene knockout simulations, pathway analysis [3] |

| AGORA2 | Database | Curated GEMs for gut microbes | 7,302 strain-level GEMs for microbiome studies [26] |

| Rhea Database | Database | Biochemical reactions | Constructing mass- and charge-balanced equations [3] |

| BioModels | Database | Curated computational models | Access to validated GEMs for model organisms |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Perspectives

The continued evolution of GEMs is expanding their applications in several promising directions. The development of pan-genome scale models captures metabolic diversity across multiple strains, enabling population-level analyses and identification of strain-specific metabolic capabilities [23]. The integration of GEMs with machine learning approaches enhances pattern recognition from high-dimensional omics data, potentially accelerating strain design cycles. Furthermore, the application of GEMs to non-model organisms with innate biosynthetic capabilities for valuable compounds is broadening the repertoire of microbial cell factories [23] [27].

In therapeutic applications, GEMs are being employed to design live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) through systematic evaluation of strain functionality, host interactions, and microbiome compatibility [26]. This approach enables rational selection of microbial consortia based on predicted metabolic interactions and therapeutic metabolite production. As GEM reconstruction methodologies become more automated and accessible, their implementation is expected to expand further, ultimately contributing to the development of customized synthetic microbial cell factories for sustainable biomanufacturing [27].

Genome-scale metabolic models represent a powerful paradigm for predicting metabolic capacity and guiding host organism selection in microbial cell factory development. By integrating genomic information with biochemical knowledge, GEMs enable quantitative prediction of metabolic phenotypes under various genetic and environmental conditions. The continued refinement of model quality, coupled with advanced computational frameworks, is enhancing their predictive accuracy and expanding application scope. As the field progresses, GEMs are poised to play an increasingly central role in rational strain design, ultimately accelerating the development of efficient microbial cell factories for sustainable bioproduction in the emerging bioeconomy era.

The selection of an optimal carbon source is a foundational decision in the development of microbial cell factories, directly influencing the economic viability, sustainability, and scalability of bioprocesses. This selection is intrinsically linked to host organism choice, as the native metabolism and engineering potential of a microbe determine its capacity to utilize different feedstocks efficiently. Traditional biomanufacturing has heavily relied on sugar-based carbon sources derived from agricultural crops, raising concerns about competition with food supply and land use. The field is now undergoing a significant paradigm shift toward the use of one-carbon (C1) feedstocks such as methanol and formate, which can be derived from the hydrogenation of captured CO2 with green hydrogen [28]. This transition represents a critical strategy for decarbonizing the biomanufacturing industry and advancing toward a circular bioeconomy.

The core challenge in this transition lies in the fundamental rewiring of microbial metabolism. While the pathways for sugar assimilation are native and well-understood in many industrial workhorses, C1 assimilation often requires the introduction of synthetic pathways and extensive metabolic remodeling to achieve sufficient carbon conversion efficiency and target product yields [29]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of carbon source options, from traditional sugars to emerging C1 feedstocks, with a specific focus on their integration into host selection and engineering strategies for microbial cell factories.

A systematic evaluation of carbon sources is essential for aligning feedstock properties with process goals, including target product value, volumetric productivity, and sustainability metrics. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of prominent carbon sources.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Carbon Sources for Microbial Biomanufacturing

| Carbon Source | Degree of Reduction | Typical Origin | Key Advantages | Key Challenges | Representative Host Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Fully Reduced (C6) | Lignocellulosic biomass, crops | High uptake rates, well-understood metabolism, supports high growth rates | Food-fuel competition, price volatility, requires arable land | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, B. subtilis [3] [30] |

| Xylose | Fully Reduced (C5) | Hemicellulose in plant biomass | Abundant in agro-industrial waste, reduces process cost | CCR in many hosts, requires specific transporters and pathways | Engineered E. coli, S. cerevisiae, P. putida [30] |

| Glycerol | Reduced (C3) | Biodiesel production byproduct | Low cost, reduced state favors reduced bioproducts | May require aerobic conditions for efficient assimilation | E. coli, P. putida, Y. lipolytica |

| Methanol | Reduced (C1) | CO2 + H2 (green H2) | High energy content, avoids food-fuel competition, liquid at RT | Toxic intermediates, inefficient native pathways in most hosts, low energy efficiency | Ogataea polymorpha, Methylorubrum extorquens [28] [31] |

| Formate | Intermediate (C1) | CO2 + H2 (green H2) | High solubility, non-toxic, simple structure | High oxygen requirement for energy generation, low carbon content | Engineered E. coli, C. autoethanogenum |

| Lignin-Derived Aromatics | Varied | Lignocellulosic biomass | Valorizes underutilized stream, unique precursor for aromatics | Heterogeneous mixture, toxic to many microbes, complex catabolism | Pseudomonas putida [32] |

The "degree of reduction" of a carbon source is a critical biochemical parameter, as it influences the maximum theoretical yield of reduced target products like biofuels and biopolymers. C1 feedstocks like methanol offer a promising alternative to sugars because they can be produced independently of arable land [28]. Their utilization, however, often demands specialized methylotrophic hosts such as the yeast Ogataea polymorpha or the bacterium Methylorubrum extorquens, which possess native C1 assimilation pathways like the serine cycle or xylulose monophosphate (XuMP) pathway [28] [31]. In contrast, the robustness of platforms like E. coli and S. cerevisiae with sugars must be weighed against the sustainability limitations of sugar production.

Host Organism Selection and Metabolic Capacities

Selecting a microbial host is a decision deeply intertwined with the chosen carbon source. A comprehensive evaluation of a host's innate metabolic capacity for target chemical production is a critical first step in strain design. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are indispensable tools for this purpose, enabling in silico prediction of maximum theoretical yield (YT) and maximum achievable yield (YA), which accounts for energy diverted to growth and maintenance [3].

Table 2: Maximum Theoretical Yields (Y_T) of Selected Chemicals in Different Hosts on Glucose (mol/mol) [3]*

| Target Chemical | E. coli | S. cerevisiae | B. subtilis | C. glutamicum | P. putida |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Lysine | 0.799 | 0.857 | 0.821 | 0.810 | 0.768 |

| L-Glutamate | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source |

| Sebacic Acid | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source |

| Propan-1-ol | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source |

A study comprehensively evaluating five industrial microorganisms for the production of 235 bio-based chemicals revealed that while S. cerevisiae often achieves the highest yields for many compounds, certain chemicals display clear host-specific superiority [3]. For instance, the production of pimelic acid was highest in Bacillus subtilis. This underscores that there is no universally superior host; the optimal choice depends on the specific chemical and pathway. For lignin-derived aromatic compounds, Pseudomonas putida is a prominent chassis due to its native catabolic pathways for compounds like ferulate, p-coumarate, and vanillate [32]. Quantitative fluxomic studies of P. putida grown on these substrates have revealed extensive metabolic remodeling, including activation of the glyoxylate shunt and anaplerotic routes, to generate the necessary NADPH and ATP required for aromatic ring cleavage [32].

For C1 feedstocks, native methylotrophs are the primary candidates. Engineering these hosts often focuses on channeling central metabolites toward the target product. For example, metabolic modeling of M. extorquens predicted a superior theoretical yield of 1.0 C-mol Glycolic acid per C-mol Methanol, which surpasses theoretical yields from sugar fermentation. This high yield is facilitated by the native production of glyoxylate, a key precursor for glycolic acid, within the serine cycle of M. extorquens [31].

Engineering Strategies for C1 Feedstock Utilization

Pathway Engineering and Optimization

Engineering non-methylotrophic model organisms like E. coli and S. cerevisiae to utilize methanol is a major goal in synthetic biology, but it remains challenging. Key strategies include:

- Introduction of Heterologous C1 Assimilation Pathways: This involves the expression of modules for methanol oxidation to formaldehyde and subsequent assimilation via pathways like the ribulose monophosphate (RuMP) or XuMP cycles.

- Cofactor Balancing: Native methanol dehydrogenase enzymes often depend on specific cofactors (e.g., PQQ in bacteria). Engineering compatible cofactor systems is crucial for efficient carbon flux.

- Protein and Enzyme Engineering: Improving the kinetics of C1-assimilating enzymes, such as methanol dehydrogenases and sugar phosphate synthases, is often necessary to achieve sufficient flux [29] [31].

- Dynamic Pathway Regulation: Implementing sensors and regulators that respond to intracellular metabolite levels can help balance energy generation and carbon assimilation, preventing the buildup of toxic intermediates like formaldehyde [29].

A promising alternative is to engineer native methylotrophs, which already possess optimized C1 assimilation machinery. In Ogataea polymorpha, the production of malate from methanol was successfully demonstrated by engineering the reductive TCA cycle in the cytosol and introducing an efficient malate transporter. Through process optimization, a titer of 13 g/L malate with a production rate of 3.3 g/L/d was achieved [28]. Similarly, M. extorquens was engineered for glycolic acid production via a heterologous NADPH-dependent glyoxylate reductase, demonstrating the feasibility of producing platform chemicals from methanol [31].

Diagram 1: C1 metabolic engineering workflow.

Systems Metabolic Engineering and In Silico Tools

Advancements in systems biology provide powerful tools for engineering C1 utilization. GEMs are used to simulate metabolic fluxes and identify potential bottlenecks and engineering targets. For instance, flux balance analysis of O. polymorpha showed that minimizing flux through the TCA cycle was beneficial for malate production, guiding the choice of overexpressing the reductive TCA pathway [28]. Elementary Flux Mode analysis of M. extorquens helped identify pathway configurations that couple growth with obligate production of glycolic acid, informing long-term strain engineering strategies [31].

13C-fluxomics, which involves feeding 13C-labeled substrates and tracking the label through metabolisms, offers quantitative insights into in vivo carbon flux. Application of this technique in P. putida grown on phenolic acids revealed how the metabolism is rewired to generate reducing equivalents (NADPH) by increasing fluxes through pyruvate carboxylase and the glyoxylate shunt, providing a quantitative blueprint for cofactor balancing [32]. The integration of multi-omics data with artificial intelligence is an emerging trend to guide protein engineering, predict metabolic imbalances, and optimize system-level performance of C1-based cell factories [29].

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Carbon Utilization

Protocol: Evaluating Microbial Growth and Production on C1 Feedstocks

Objective: To assess the growth kinetics and product formation of an engineered microbial strain using methanol as the sole carbon source.

Materials:

- Strain: Engineered Ogataea polymorpha or Methylorubrum extorquens.

- Media: Defined mineral medium (e.g., Verduyn medium) [28].

- Carbon Source: Methanol, filter-sterilized.

- Bioreactor/Shake Flasks: Baffled flasks for improved aeration or bioreactors for controlled feeding.

- Analytical Instruments: HPLC for metabolite analysis (methanol, organic acids), GC-MS for volatile products, spectrophotometer for OD measurement.

Procedure:

- Pre-culture: Grow a pre-culture using a standard rich medium (e.g., YPD with glucose) to generate sufficient biomass. Note that heterologous genes under methanol-inducible promoters will not be activated at this stage.

- Cell Harvest and Induction: Harvest cells by centrifugation, wash with sterile saline or minimal medium without a carbon source to remove residual sugars. This is a critical step to ensure methanol is the sole carbon source.

- Production Phase: Resuspend the cell pellet in defined mineral medium containing methanol (e.g., 0.5-1% v/v) as the sole carbon source. Use buffered media or pH control to maintain optimal pH, as acid production can inhibit growth.

- Fed-Batch Cultivation: For extended fermentations, employ a fed-batch strategy with continuous or pulsed feeding of methanol to maintain a low, non-toxic concentration and prevent excessive evaporation.

- Monitoring and Sampling: Regularly sample the culture to measure optical density (OD600), substrate consumption (methanol), and product formation (e.g., malate, glycolate). Correlate product titers with cell growth (biomass).

- Analysis: Quantify metabolites using HPLC. Compare the experimental yield (g product / g methanol) to the theoretical yield predicted by metabolic models [28] [31].

Protocol: 13C-Fluxomics Analysis for Carbon Tracing

Objective: To quantitatively map the intracellular carbon flux distribution in a host organism utilizing a specific feedstock.

Materials:

- 13C-Labeled Substrate: e.g., 13C-Methanol or 13C-Glucose.

- Quenching Solution: Cold aqueous methanol (-40°C).

- Extraction Solvent: Methanol/chloroform/water mixture.

- Derivatization Reagents: e.g., Methoxyamine hydrochloride and N-methyl-N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MTBSTFA).

- Instrumentation: GC-MS coupled to a mass spectrometer.

Procedure:

- Cultivation and Labeling: Grow the microbial culture in a bioreactor with the unlabeled substrate until mid-exponential phase. Rapidly switch the feed to an identical medium containing the 13C-labeled substrate. This "isotope pulse" should be short (e.g., 30-60 seconds) to capture initial label incorporation or longer for metabolic steady-state.

- Rapid Sampling and Quenching: Withdraw culture samples rapidly and immediately quench in cold quenching solution to instantaneously halt metabolic activity.

- Metabolite Extraction: Extract intracellular metabolites using the extraction solvent. Centrifuge to separate phases and collect the polar (aqueous) phase for central metabolite analysis.

- Derivatization: Derivatize the metabolite extracts to make them volatile for GC-MS analysis.

- GC-MS Measurement: Inject the derivatized samples. The mass spectrometer will detect the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of each metabolite fragment, indicating the incorporation of 13C atoms.

- Flux Calculation: Use computational software (e.g., INCA, OpenFlux) to fit the experimental MID data to a metabolic network model, thereby calculating the intracellular metabolic flux map [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Carbon Source and Host Engineering Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Mineral Medium | Supports growth without interfering carbon sources; essential for C1 fermentation studies. | Cultivating O. polymorpha or M. extorquens on methanol [28]. |

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracer for fluxomics studies to quantify in vivo metabolic fluxes. | Mapping carbon flow through the TCA cycle and glyoxylate shunt in P. putida [32]. |

| Methanol-Inducible Promoters | Tightly regulates gene expression, induced only when methanol is present. | Controlling heterologous gene expression in methylotrophic yeasts like O. polymorpha [28]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | In silico prediction of metabolic capabilities, yields, and gene knockout targets. | Predicting maximum yield of glycolic acid from methanol in M. extorquens [31]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise genome editing for gene knockouts, knock-ins, and regulatory engineering. | Creating targeted mutations in potential bottleneck genes (e.g., vdh, pobA) in P. putida [3] [32]. |

| HPLC/GC-MS Systems | Quantitative analysis of substrate consumption, product formation, and metabolite pools. | Measuring malate, acetone, and isoprene titers in culture supernatants [28]. |

The strategic selection and engineering of carbon sources are pivotal for the future of sustainable biomanufacturing. While sugar-based feedstocks continue to be important, particularly for high-value products, the compelling environmental and economic potential of C1 feedstocks like methanol and formate is driving intensive research and development. The successful implementation of C1-based processes hinges on a deeply integrated approach to host selection and metabolic engineering. This involves not only introducing heterologous pathways into versatile chassis like E. coli but also expanding the product spectrum of native methylotrophs like O. polymorpha and M. extorquens through advanced genetic tools [28] [31].

Future progress will be accelerated by the convergence of systems biology, synthetic biology, and artificial intelligence. AI-assisted protein design can help evolve enzymes with higher activity for C1 conversion, while multi-omics integration will guide the rational remodeling of central metabolism for optimal cofactor balancing and carbon efficiency [29]. Furthermore, the development of robust processes that integrate upstream green methanol production with downstream fermentation will be crucial for achieving true carbon neutrality. As these technologies mature, microbial cell factories powered by C1 feedstocks will play an increasingly vital role in displacing petrochemical processes, mitigating climate change, and establishing a circular bioeconomy.

The selection of an optimal microbial host organism is a foundational step in developing efficient microbial cell factories (MCFs) for sustainable bioproduction. This decision directly impacts the maximum theoretical yield, productivity, and ultimate economic viability of the bioprocess. While model organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have historically been the primary workhorses of metabolic engineering, a systematic comparison of a broader range of industrial hosts across a wide spectrum of target chemicals has been lacking. This case study scrutinizes a comprehensive evaluation of the innate metabolic capacities of five representative industrial microorganisms for the production of 235 bio-based chemicals. The findings provide a strategic resource for researchers and scientists in the field of systems metabolic engineering, offering data-driven guidance for rational host selection and subsequent pathway optimization.

Methodology for Metabolic Capacity Evaluation

Host Strains and Target Chemicals

The analysis focused on five industrially relevant microorganisms: Bacillus subtilis, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas putida, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [3]. These strains were selected due to their prevalence in both academic research and industrial biomanufacturing. The study encompassed a total of 235 bio-based chemicals, including bulk chemicals, fine chemicals, fuels, polymers, and natural products, providing a broad overview of microbial production potential [3].

Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (GEM) and Pathway Construction

The core of the evaluation relied on Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) to mathematically represent the gene-protein-reaction associations within each organism [3].

- Model Construction: A separate GEM was constructed for each chemical biosynthetic pathway in each host, resulting in a total of 1,360 individual models [3].

- Pathway Reconstruction: For 1,092 of these models, heterologous reactions not natively present in the host strain's metabolic network were introduced to establish functional biosynthetic pathways. The remaining 268 models utilized existing native pathways [3]. Notably, for over 80% of the target chemicals, fewer than five heterologous reactions were required to construct a functional pathway across all hosts [3].

- Mass and Charge Balancing: All metabolic reactions were organized into mass- and charge-balanced equations using the Rhea database, with manual curation for reactions not present in the database [3].

Calculation of Metabolic Capacity Metrics

The metabolic capacity of each host for every chemical was quantified using two key yield metrics, calculated under varied conditions of carbon source (e.g., D-glucose, glycerol, xylose) and aeration (aerobic, microaerobic, anaerobic) [3].

- Maximum Theoretical Yield (YT): This represents the maximum production of the target chemical per given carbon source when all cellular resources are theoretically allocated toward production, ignoring metabolic fluxes required for cell growth and maintenance [3].

- Maximum Achievable Yield (YA): A more realistic metric, YA accounts for the cell's requirement for non-growth-associated maintenance energy (NGAM) and sets a lower bound for the specific growth rate (e.g., 10% of the maximum biomass production rate) to ensure minimum growth requirements are met [3].

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for constructing the metabolic models and calculating the key yield metrics.

Key Findings and Comparative Analysis of Host Performance