Strategies for Overcoming Metabolic Burden in Engineered Microbial Hosts: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

Metabolic burden, a major bottleneck in developing robust microbial cell factories, arises from the rewiring of host metabolism for bioproduction, leading to impaired growth and low yields.

Strategies for Overcoming Metabolic Burden in Engineered Microbial Hosts: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

Abstract

Metabolic burden, a major bottleneck in developing robust microbial cell factories, arises from the rewiring of host metabolism for bioproduction, leading to impaired growth and low yields. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of metabolic burden, advanced methodological and computational tools for its prediction and mitigation, practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance strain robustness, and finally, the frameworks for experimental validation and comparative analysis essential for translating engineered strains into scalable, clinically relevant bioprocesses.

Defining the Challenge: The Cellular Costs of Metabolic Engineering

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Reduced Microbial Growth Rates

Problem: Observed decline in cell growth and division after introducing a heterologous pathway. Root Cause: Metabolic burden is diverting essential resources (ATP, amino acids, precursors) away from cellular growth and maintenance towards the engineered function [1] [2]. Solution Steps:

- Quantify the Burden: Measure the specific growth rate (μ) of your engineered strain and compare it to the wild-type or empty vector control. A reduction of more than 20% indicates significant burden [1].

- Check Precursor Availability: Analyze intracellular levels of key metabolites like ATP and NADPH using enzymatic assays or LC-MS. Depletion confirms resource competition.

- Implement Dynamic Control: Switch from a constitutive promoter to an inducible system (e.g., arabinose-inducible pBAD) to decouple production from growth phases [3].

- Verify Construct Integrity: Sequence the plasmid to ensure no mutations have arisen that increase expression burden unnecessarily.

Guide 2: Managing Stress Responses and Genetic Instability

Problem: Culture heterogeneity, loss of plasmid, or accumulation of misfolded proteins. Root Cause: Overexpression triggers stress responses (e.g., stringent response, heat shock) due to depletion of charged tRNAs or accumulation of misfolded proteins, leading to genetic instability [1]. Solution Steps:

- Detect Stress Markers: Use qPCR to monitor transcript levels of stress response genes (e.g.,

relAfor stringent response,dnaKfor heat shock) [1]. - Optimize Codon Usage: For heterologous genes, avoid rare codons without eliminating strategic slow-translating regions crucial for proper protein folding. Use codon optimization tools with caution [1].

- Supplement Key Nutrients: Add casamino acids to the medium to supplement the amino acid pool and reduce tRNA charging pressure [1].

- Apply Evolutionary Engineering: Perform serial passaging or adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) to select for robust mutants that maintain genetic stability under production conditions [3] [4].

Guide 3: Overcoming Low Product Yields Despite High Pathway Expression

Problem: Strong pathway expression verified, but final product titer remains low. Root Cause: Imbalanced metabolic flux, intermediate metabolite toxicity, or insufficient cofactor regeneration overwhelming the host's capacity [3] [4]. Solution Steps:

- Profile Metabolites: Conduct metabolomics or use biosensors to detect accumulating toxic intermediates that may inhibit growth or product synthesis [4].

- Balance Gene Expression: Tune the expression levels of individual pathway genes using promoter libraries or ribosomal binding site (RBS) engineering to minimize flux bottlenecks and toxic intermediate accumulation [3].

- Implement Division of Labor (DoL): Distribute the metabolic pathway across a synthetic microbial consortium. Engineer one strain to convert the initial substrate to an intermediate and a second strain to convert the intermediate to the final product [4].

- Modulate Cofactor Regeneration: Overexpress enzymes involved in NADPH/NADH regeneration (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) to support cofactor-dependent biosynthesis reactions [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is "metabolic burden" in simple terms? A1: Metabolic burden is the stress placed on a microbial host when engineered genetic elements (like plasmids and heterologous pathways) compete with native processes for finite intracellular resources. This includes energy (ATP), reducing equivalents (NADPH), precursor metabolites, amino acids, and the translational machinery [2] [1]. This competition forces physiological trade-offs, often reducing cell growth and productivity.

Q2: How can I measure metabolic burden in my engineered strain? A2: You can quantify burden using several methods:

- Growth Kinetics: Compare the specific growth rate and maximum biomass yield of your engineered strain versus a control [1].

- Transcriptomics/Proteomics: Identify upregulated stress response pathways (e.g., stringent response, heat shock) [1].

- Metabolite Analysis: Measure depletion of key central metabolites or ATP.

- Plasmid Stability Assays: Monitor the rate of plasmid loss over multiple generations in selective versus non-selective media [1].

Q3: My product is toxic. Is that the same as metabolic burden? A3: No, they are distinct but often interconnected concepts. Metabolic burden arises from the cost of production (resource allocation), while product toxicity stems from the inherent properties of the final product itself, which may damage membranes or inhibit enzymes [4]. A toxic product can exacerbate burden by forcing the cell to expend more energy on efflux pumps or repair mechanisms.

Q4: What are the most effective strategies to reduce metabolic burden? A4: Strategies can be implemented at multiple levels [3]:

- Genetic Level: Use tunable promoters, optimize codon usage, and delete competing pathways.

- System Level: Implement dynamic control systems that separate growth and production phases.

- Population Level: Employ microbial consortia to divide the metabolic labor between specialized strains [4].

- Process Level: Use adaptive laboratory evolution to select for fitter, higher-producing strains.

Quantitative Data on Metabolic Burden Effects

The following table summarizes common physiological symptoms and their quantitative impact on host performance, as documented in scientific literature.

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Metabolic Burden on Engineered Microbial Hosts

| Physiological Symptom | Measurement Parameter | Typical Observation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced Growth & Biomass | Specific Growth Rate (μ) | Can decrease by 20-50% compared to wild-type | [1] [2] |

| Impaired Protein Synthesis | Global Protein Production | Reduction in total cellular protein content | [1] |

| Genetic Instability | Plasmid Loss Rate | Can exceed 50% over 50+ generations without selection | [1] |

| Stress Response Activation | Stress Gene Expression (e.g., relA, dnaK) |

Upregulation by >5-fold | [1] |

| Reduced Product Titer | Final Product Concentration | Significant drop, leading to non-viable industrial processes | [1] [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Plasmid Stability in Long-Term Cultivation

Objective: To determine the genetic instability caused by metabolic burden from an engineered plasmid. Materials: Engineered strain, control strain, selective solid medium, non-selective solid medium, liquid LB medium, shake flask, spectrophotometer. Methodology:

- Inoculation: Start a batch culture in liquid non-selective medium from a single colony.

- Serial Passage: Every 24 hours, dilute the culture in fresh non-selective medium to maintain continuous exponential growth. This removes selection pressure.

- Plating and Counting: At timepoints T=0, 24, 48, 72, etc., plate appropriate dilutions onto both selective and non-selective solid media.

- Calculation: After incubation, count the colonies. The percentage of plasmid-bearing cells = (CFU on selective media / CFU on non-selective media) × 100%.

- Analysis: Plot the percentage of plasmid-bearing cells over time. A steep decline indicates high metabolic burden and instability [1].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Synthetic Microbial Consortium for Division of Labor

Objective: To split a metabolically burdensome pathway between two microbial strains to enhance overall production. Materials: Two engineered strains (Strain A: produces intermediate; Strain B: consumes intermediate for final product), fermentation bioreactor, defined medium, OD600 spectrophotometer, product analytics (e.g., HPLC). Methodology:

- Strain Engineering: Genetically modify Strain A to overproduce and export a pathway intermediate. Engineer Strain B to efficiently import and convert this intermediate into the desired final product. Ensure nutritional divergence to avoid direct competition [4].

- Inoculation Optimization: Co-culture the two strains in a shake flask at varying initial inoculation ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:9, 9:1 of A:B). Monitor growth (OD600) and product titer.

- Bioreactor Cultivation: Scale up the optimal co-culture ratio to a controlled bioreactor. Maintain environmental conditions (pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature) constant.

- Population Monitoring: Use flow cytometry with strain-specific fluorescent markers or selective plating to monitor the population dynamics of each strain throughout the fermentation.

- Performance Assessment: Compare the final product titer and yield of the co-culture system to a monoculture of a strain engineered with the full pathway [4].

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Workflows

Metabolic Burden Cascade

Burden Mitigation Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Managing Metabolic Burden

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Promoters | Fine-control gene expression levels to balance resource demand. | pBAD (arabinose-inducible), promoter libraries of varying strength. |

| Inducible Systems | Decouple growth phase from production phase to minimize burden. | Tet-On/Off, IPTG-inducible lac/tac systems. |

| CRISPR-Cas Tools | For precise gene knockouts (competing pathways) or integration of pathways into the chromosome to avoid plasmid burden. | CRISPRi for gene repression; CRISPR-Cas9 for knock-ins. |

| Biosensors | Real-time monitoring of metabolite levels or stress response to inform dynamic control. | Transcription factor-based biosensors for key intermediates. |

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | Maintain pools of NADPH/NADH for energetically demanding biosynthesis. | Overexpression of PntAB (transhydrogenase) or G6PD (Zwf). |

| Microbial Consortia Kits | Tools for building and analyzing co-cultures. | Fluorescent reporter plasmids for tracking subpopulations. |

| Stress Reporter Plasmids | Quantify activation of specific stress responses (e.g., stringent, heat shock). | GFP reporters under control of stress-responsive promoters (e.g., dnaKp). |

FAQs: Addressing Core Challenges in Microbial Metabolic Engineering

Q1: What are the primary causes of cofactor imbalance in engineered microbial hosts, and how can they be detected?

Cofactor imbalances frequently arise when introduced metabolic pathways place unnatural demands on the cell's native cofactor regeneration systems. A common scenario is the excessive drain of NADPH in strains engineered for the production of compounds like terpenoids or fatty acids [5] [6]. Key indicators include suboptimal product titers, accumulation of toxic intermediates, and impaired cell growth. Detection relies on omics analyses (e.g., flux balance analysis) and monitoring by-product profiles; for instance, an increase in lactate formation can signal a redox imbalance where NADH is not adequately recycled [6].

Q2: How does protein overexpression become a stressor, and what are the consequences?

Overexpression of recombinant proteins, especially heterologous ones, can overwhelm the host's transcriptional and translational machinery, leading to a metabolic burden that diverts resources (energy, amino acids) from growth and maintenance [7]. This can trigger cellular stress responses, such as the unfolded protein response (UPR) in eukaryotic hosts like Komagataella phaffii, and lead to protein misfolding, inclusion body formation, or activation of proteolytic systems that degrade the target protein [7] [8]. In filamentous fungi like Aspergillus niger, high-level secretion of recombinant proteins can also saturate the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus, creating a bottleneck [7].

Q3: What genetic manipulation tools are most effective for minimizing unintended stress in industrial strains?

CRISPR/Cas9-based systems are highly effective for precise genome editing, enabling targeted gene knockouts, knock-ins, and multiplexed engineering without leaving residual marker sequences, thereby minimizing metabolic burden [7] [9]. For actinomycetes and other non-model hosts, using host-adapted genetic parts (e.g., endogenous promoters and ribosomal binding sites with high GC content) is crucial for reliable expression and reducing unintended stress caused by heterologous sequences [10]. Additionally, inducible systems and riboswitches allow for temporal control of gene expression, decoupling growth from production phases to mitigate stress [10] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides: Diagnostic Tables and Strategic Solutions

This section provides actionable strategies to diagnose and resolve common issues.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Cofactor Imbalance

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution | Exemplary Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low product yield, poor cell growth | NADPH depletion in a highly reducing pathway | Engineer NADPH regeneration: Modulate EMP/PPP/ED flux via FBA; Express heterologous transhydrogenase [5]. | D-pantothenic acid production increased from 5.65 g/L to 6.71 g/L in flask cultures after introducing a transhydrogenase from S. cerevisiae [5]. |

| Accumulation of fermentation by-products (e.g., lactate) | Redox imbalance (excess NADH) | Convert NADH to NADPH: Express a soluble transhydrogenase or NADH kinase (e.g., Pos5P) [5] [6]. | In B. subtilis, expression of pos5P enhanced NADPH availability for menaquinone-7 synthesis and reduced lactate by 9.15% [6]. |

| Inefficient one-carbon metabolism | Insufficient 5,10-MTHF supply | Enhance one-carbon units: Engineer the serine-glycine cycle to bolster 5,10-MTHF pools [5]. | Optimizing the serine-glycine system supported one‑carbon supply for record-level D-pantothenic acid production (124.3 g/L) [5]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Protein Overexpression and Secretion

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution | Exemplary Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low extracellular protein yield (eukaryotic hosts) | Saturated secretory pathway; ER stress | Engineer secretion capacity: Overexpress vesicle trafficking components (e.g., COPI component Cvc2); Use protease-deficient strains [7]. | In A. niger, overexpressing Cvc2 enhanced pectate lyase (MtPlyA) secretion by 18% [7]. |

| Low functional protein yield, inclusion body formation (prokaryotic hosts) | Improper protein folding; lack of PTMs | Optimize expression host and vector: Use hosts with enhanced chaperones (e.g., E. coli Origami); Utilize secretion systems (Sec, Tat) for folding in periplasm [12]. | Brevibacillus choshinensis is a Gram-positive host optimized for high-yield extracellular protein secretion via its Sec system [12]. |

| High background protein secretion | Host produces abundant native proteins | Create a clean chassis: Delete genes for major native secreted proteins [7]. | An A. niger chassis strain (AnN2) with 13/20 glucoamylase genes and the PepA protease gene deleted showed 61% reduced background protein [7]. |

Table 3: Troubleshooting Genetic Manipulation and Expression Control

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Solution | Exemplary Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low transformation efficiency (non-model hosts) | Restriction-modification (RM) systems degrade foreign DNA | Mimic host methylation patterns; disrupt native RM systems [10]. | Mimicking Streptomyces methylation motifs significantly improved transformation efficiency [10]. |

| Uncontrolled gene expression, metabolic burden | Constitutive, strong promoters lack temporal control | Use dynamic regulation: Implement inducible promoters or riboswitches responsive to metabolic cues [10] [11]. | A theophylline riboswitch achieved 30 to 260-fold induction with low basal expression in S. coelicolor [10]. |

| Suboptimal translation efficiency | Poorly designed 5' Untranslated Region (UTR) | Engineer UTRs: Use UTR libraries or computational design (UTR Designer) to optimize RBS strength and mRNA stability [11]. | Fine-tuning repressor genes (phlF, mcbR) with designed UTRs increased 3-HP production in E. coli by 16.5-fold [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Enhancing Cofactor Regeneration via NADPH Engineering

This protocol outlines steps to alleviate NADPH limitation, a common bottleneck.

- In Silico Flux Analysis: Perform Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) on a genome-scale model to identify optimal flux distributions through central carbon metabolism (EMP, PPP, ED pathways) that maximize NADPH regeneration [5].

- Genetic Modifications:

- Modulate Central Carbon Metabolism: Repurpose carbon flux by modulating gene expression of key enzymes (e.g., upregulating glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in the PPP).

- Introduce Heterologous Cofactor Conversion Systems: Clone and express a soluble transhydrogenase (e.g., S. cerevisiae UdhA) to interconvert NADH and NADPH [5].

- Express an NADH Kinase: Introduce a gene like pos5P from yeast to phosphorylate NADH, directly generating NADPH [6].

- Validation: Measure the intracellular NADPH/NADP+ ratio using enzymatic assays and quantify the target product titer. In a fed-batch fermenter, monitor by-products like lactate to assess redox rebalancing [6].

Protocol 2: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Multiplex Engineering in an Industrial Yeast

This protocol describes genome editing in a polyploid industrial strain for heme overproduction [9].

- Strain Selection: Select a robust industrial host (e.g., S. cerevisiae KCCM 12638) with naturally high precursor flux.

- gRNA and Donor DNA Design: Design multiple gRNAs to target the genomic loci of genes for overexpression (e.g., HEM2, HEM3, HEM12, HEM13). For each, provide a donor DNA template containing the homologous gene sequence driven by a strong constitutive promoter.

- Co-transformation: Co-transform the strain with a CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid and the pooled donor DNA fragments.

- Screening and Genotype Verification: Screen for successful integrants via antibiotic selection or fluorescence. Validate the genotype using PCR and DNA sequencing.

- Phenotype Assessment: Ferment engineered strains in controlled bioreactors and quantify heme production using HPLC or spectrophotometric methods [9].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

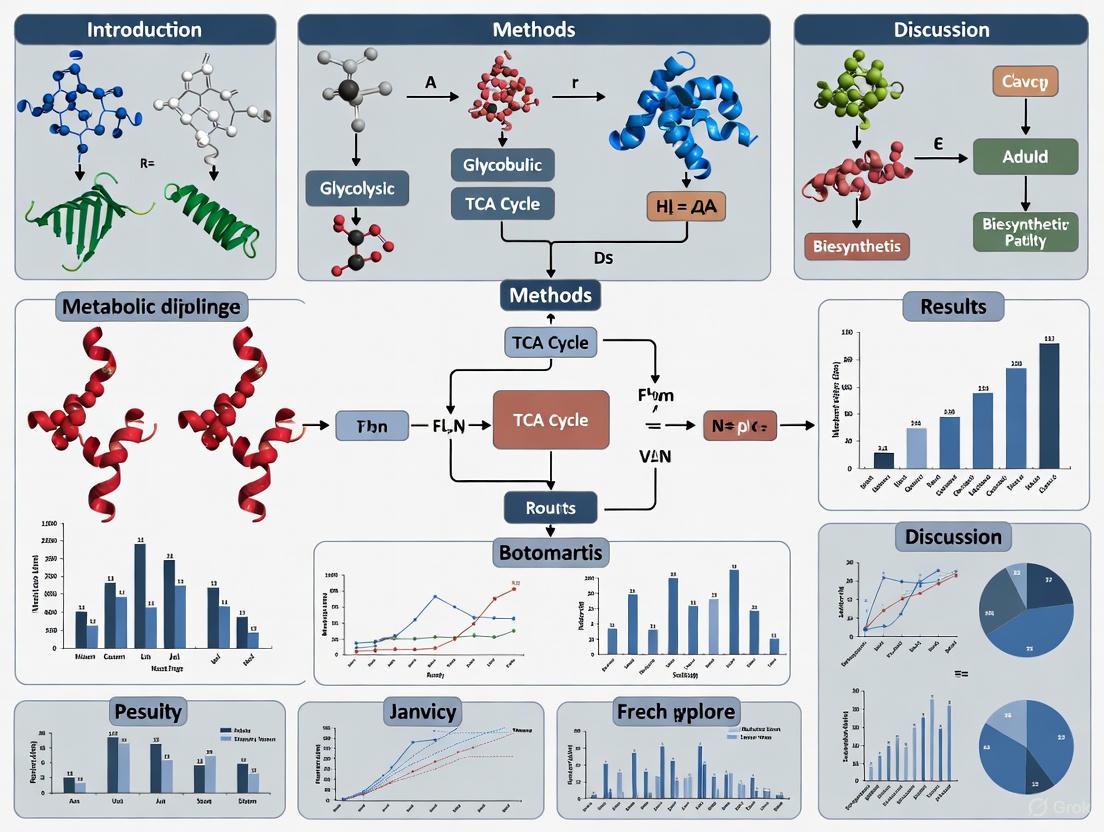

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected nature of key stressors and the engineering strategies used to overcome them, forming a central conceptual framework for this guide.

Figure 1: Logical Framework for Diagnosing and Resolving Key Stressors in Engineered Microbes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Strains

| Category / Reagent | Specific Example(s) | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Chassis Strains | E. coli W3110 [5]; Bacillus subtilis 168 [6]; Aspergillus niger AnN2 (low-backhost chassis) [7]; Komagataella phaffii GS115 (protease-deficient) [8] | Robust, well-characterized hosts with reduced background interference, optimized for metabolic engineering or recombinant protein production. |

| Genetic Toolkits | CRISPR/Cas9 systems for S. cerevisiae [9] and A. niger [7]; Plasmid systems with strong promoters (P43, Phbs) [6] | Enable precise genome editing, gene knockouts, and controlled overexpression of pathway genes. |

| Cofactor Regeneration Enzymes | Soluble transhydrogenase (UdhA from E. coli or S. cerevisiae) [5]; NADH kinase (Pos5P from S. cerevisiae) [6] | Rebalance intracellular NADPH/NADH pools to support cofactor-intensive biosynthetic pathways. |

| Secretion Pathway Components | COPI vesicle component Cvc2 [7]; Signal peptides for Sec/Tat pathways [12] | Enhance the capacity of the cellular secretory machinery to improve recombinant protein yield and fidelity. |

| Fine-Tuning Regulatory Elements | Synthetic 5' UTR libraries [11]; Theophylline riboswitch (E) [10]; Strong constitutive promoters (kasOp) [10] | Provide precise control over gene expression levels, enabling metabolic flux optimization and dynamic regulation. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why is my engineered microbial host experiencing a significantly reduced growth rate after introduction of a heterologous pathway?

A retarded growth rate is a classic symptom of metabolic burden, where the rewiring of metabolism diverts energy and resources away from cellular growth and maintenance.

- Primary Cause: The (over)expression of heterologous proteins drains the cellular pool of amino acids and charged tRNAs. This starvation triggers the stringent response, a major stress mechanism governed by the alarmone ppGpp. ppGpp massively reprograms cellular transcription, shutting down the synthesis of rRNA and tRNA to halt growth and conserve resources [13].

Additional Triggers:

- Codon Usage Mismatch: Heterologous genes may contain codons that are rare in the host organism, leading to ribosomal stalling and a further increase in uncharged tRNAs, amplifying the stringent response [13].

- Energy Drain: The synthesis of new proteins and metabolites consumes ATP and metabolic precursors (e.g., acetyl-CoA, NADPH), directly competing with the host's central metabolism for energy generation and biomass production [3].

Recommended Solutions:

- Implement Dynamic Regulation: Use inducible promoters or genetic circuits that delay the expression of the heterologous pathway until after the peak growth phase. This separates the growth phase from the production phase [3] [10].

- Fine-Tune Expression Levels: Avoid overly strong constitutive promoters. Use a library of promoters with varying strengths to find the optimal level of pathway expression that balances production and growth [10].

- Perform Codon Optimization: Optimize the gene sequence to match the codon usage bias of the host organism, but with care to preserve any native rare codon regions that might be critical for correct protein folding [13].

FAQ 2: What causes genetic instability, such as plasmid loss or chromosomal rearrangements, in my production strain over long fermentation runs?

Genetic instability is a survival mechanism whereby cells evade the metabolic burden imposed by engineered pathways, often leading to a heterogeneous population dominated by non-productive cells.

- Primary Cause: Transgene exclusion is a common mechanism to alleviate metabolic burden. Cells that spontaneously lose the plasmid or inactivate the heterologous pathway gain a growth advantage and outcompete the productive cells [14] [13].

Additional Triggers:

- Genome Plasticity and eccDNA: Inherent genome instability can lead to the formation of extrachromosomal circular DNA (eccDNA). These circular DNA elements can facilitate ultra-high gene expression and genetic heterogeneity, contributing to phenotypic drift and instability in clonal populations [14].

- Stress-Induced Mutagenesis: General cellular stress from metabolic burden can activate the SOS response (DNA damage repair) and other error-prone repair systems, increasing the mutation rate across the genome [13].

Recommended Solutions:

- Use Genetically Stable Integration: Integrate the heterologous pathway into the host chromosome at a stable "safe harbor" locus instead of using multi-copy plasmids, to prevent plasmid loss [14] [10].

- Incorporate Essential Genes in the Construct: Design plasmids where the heterologous pathway is coupled to an essential gene for cell survival, so cells cannot lose the pathway without a fitness cost [15].

- Disrupt Restriction-Modification Systems: In non-model strains, identify and disrupt native restriction-modification systems that may hamper genetic stability and transformation efficiency [10].

FAQ 3: Why am I observing low product titers despite high initial pathway expression in my robust host organism?

Low product titers can result from a combination of stress responses and imbalances within the engineered metabolic network that are not immediately apparent from growth measurements alone.

- Primary Cause: Impaired Protein Function. Stress from amino acid depletion and ribosomal stalling can lead to translation errors, producing misfolded and inactive enzymes. This places additional burden on the cell's chaperone and protease systems (heat shock response), reducing the effective concentration of functional pathway enzymes [13].

Additional Triggers:

- Redox and Metabolic Imbalances: Introducing new pathways can create cofactor imbalances (e.g., NADPH/NADP⁺) or cause the accumulation of toxic intermediates, which feedback to inhibit the pathway or cause general toxicity [3].

- Premature Pathway Shutdown: General stress responses can lead to a global downregulation of transcription and translation, effectively shutting down the very pathway you are trying to express [13].

Recommended Solutions:

- Engineer Robust Chassis: Modify the host to be more resilient by overexpressing chaperones (e.g., DnaK/DnaJ) to assist with protein folding or engineering cofactor regeneration systems to maintain redox balance [3] [13].

- Apply Microbial Consortia: Distribute the metabolic burden by engineering different pathway modules into separate specialist strains. This division of labor can prevent the overburdening of a single host [3].

- Modulate Central Metabolism: Use computational models to predict and relieve metabolic bottlenecks, such as by knocking out competing pathways or overexpressing key precursor-supplying enzymes to redirect flux toward the desired product [3] [10].

Quantitative Data on Stress Symptoms and Responses

Table 1: Common Stress Symptoms and Their Direct Links to Metabolic Burden

| Observed Symptom | Direct Cause | Underlying Activated Stress Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Retarded Growth Rate | Depletion of amino acids and energy (ATP) pools. | Stringent Response (ppGpp) [13] |

| Genetic Instability & Plasmid Loss | Selective pressure to escape burden; DNA damage. | SOS Response; Transgene Exclusion [14] [13] |

| Reduced Product Titers | Misfolded/inactive enzymes; metabolic flux imbalance. | Heat Shock Response; Resource Competition [13] |

| Aberrant Cell Morphology | Disruption of cell division and envelope synthesis. | Envelope Stress Response [13] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Mitigating Metabolic Burden

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible Promoters (e.g., tipA, nitAp) | Enables temporal control of gene expression to separate growth and production phases. | Dynamic regulation of a heterologous pathway in Streptomyces to minimize burden during rapid growth [10]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Enables precise gene knockouts, knock-ins, and chromosomal integration of pathways. | Knocking out a competing metabolic pathway or integrating a biosynthetic gene cluster into a chromosomal "safe harbor" [16]. |

| Theophylline Riboswitch (E*) | Provides post-transcriptional control of gene expression with low basal levels and tunable induction. | Fine-tuning the expression level of a toxic enzyme in S. coelicolor to find the optimal balance between production and cell fitness [10]. |

| Constitutive Promoter Library | A set of promoters with characterized and varying strengths. | Screening for the optimal promoter strength to express a heterologous gene without triggering a severe stringent response [10]. |

| Stbl2 or Stbl4 E. coli Cells | Specialized strains for improved stability of hard-to-clone sequences (e.g., repeats). | Propagating plasmids containing direct repeats or tandem repeats that are prone to recombination in standard strains [15]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Dynamic Regulation of a Heterologous Pathway Using an Inducible System

Objective: To minimize metabolic burden during the growth phase by decoupling cell proliferation from product formation.

- Vector Construction: Clone your heterologous pathway genes into a vector downstream of a tightly regulated, inducible promoter (e.g., anhydrotetracycline-inducible nitAp or thiostrepton-inducible tipA). For E. coli, the L-rhamnose inducible system is a common choice [10].

- Strain Transformation: Introduce the constructed vector into your microbial host.

- Two-Phase Fermentation:

- Growth Phase: Inoculate the production medium and allow the cells to grow to mid-exponential phase without inducer. This allows for rapid biomass accumulation.

- Production Phase: Add a defined concentration of the chemical inducer to the culture to activate transcription of the heterologous pathway.

- Monitoring and Analysis: Track cell density (OD₆₀₀), product titer (e.g., via HPLC or GC-MS), and substrate consumption throughout the fermentation. Compare with a control strain where the pathway is constitutively expressed.

Protocol 2: Chromosomal Integration of a Biosynthetic Pathway for Enhanced Genetic Stability

Objective: To mitigate genetic instability caused by plasmid loss by stably integrating the pathway into the host chromosome.

- Target Selection: Identify a genetically neutral "safe harbor" locus in the host genome (e.g., an attachment site attB for phage integrases, or a non-essential gene locus).

- Integration Construct Design: Using CRISPR/Cas9 or homologous recombination, design a construct containing your pathway genes flanked by homology arms (500-1000 bp) targeting the chosen locus.

- Delivery and Selection:

- For CRISPR, co-transform the host with a Cas9 plasmid (targeting the native locus to create a double-strand break) and a donor DNA template containing your pathway.

- For homologous recombination, introduce a non-replicating plasmid or linear DNA fragment containing the construct into the host.

- Screening and Verification: Screen for successful recombinants by antibiotic selection or PCR. Verify the loss of the original plasmid and confirm stable production over multiple generations without selection pressure [14] [10] [16].

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected stress responses triggered by the (over)expression of heterologous proteins, linking the initial engineering trigger to the final observed physiological symptoms.

This diagram shows how the initial trigger of protein overexpression leads to primary stressors like resource depletion. These stressors activate fundamental stress response mechanisms, which in turn directly cause the adverse physiological effects that hinder bioproduction. The interconnected nature of these responses means that a single trigger can lead to multiple, compounding symptoms.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs on Metabolic Burden in Engineered Microbes

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My engineered E. coli strain shows a significantly decreased growth rate after introducing a heterologous pathway. What is the primary cause?

A1: A decreased growth rate is a classic symptom of metabolic burden. The primary cause is the redirection of cellular resources away from growth and maintenance towards the synthesis and operation of your heterologous pathway [1]. This includes:

- Resource Drain: The synthesis of heterologous enzymes consumes precursors, energy (ATP), and cofactors (e.g., NADPH) that would otherwise be used for native cellular processes, including replication and biomass production [1] [17].

- Activation of Stress Responses: The high demand for specific amino acids or tRNAs can lead to their depletion, activating the stringent response via the alarmone ppGpp. This response globally shifts gene expression away from growth-related processes [1].

- Protein Misfolding: Improper codon usage or high translation rates can lead to protein misfolding, which further burdens the cell by activating the heat shock response and overloading chaperone and protease systems [1].

Q2: During scale-up, my production titer drops and the population becomes unstable. Why does this happen and how can I prevent it?

A2: This is a common issue when moving from controlled lab cultures to large-scale fermentation, where environmental fluctuations are more pronounced. The drop in titer is often due to genetic and phenotypic instability [18].

- Cause: In large-scale bioreactors, gradients in nutrient concentration, pH, and oxygen can develop. Engineered cells, already under metabolic burden, are more sensitive to these stresses. Without selective pressure (e.g., antibiotics), cells that mutate or lose the production pathway can outgrow the high-producing but burdened cells [18].

- Prevention: Implement antibiotic-free plasmid stability systems.

- Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Systems: Integrate a stable toxin gene into the genome and express the antitoxin from your plasmid. Only cells retaining the plasmid survive [18].

- Auxotrophy Complementation: Delete an essential gene (e.g.,

infA) from the chromosome and place it on the plasmid. Cells must maintain the plasmid to produce this essential protein and survive [18].

Q3: What is "overflow metabolism" and why would a cell use an inefficient metabolic pathway, wasting resources?

A3: Overflow metabolism (e.g., the Crabtree effect in yeast or aerobic acetate production in E. coli) is the seemingly wasteful use of a high-carbon flux to produce partially oxidized byproducts (like ethanol or acetate) even in the presence of oxygen [19].

- Cause from a Fitness Perspective: This is not a simple "overflow" but a strategic trade-off made by the cell to maximize the growth rate. While inefficient pathways produce less ATP per glucose molecule, they can generate ATP at a faster rate and with a lower protein synthesis cost than efficient, fully respiratory pathways [19].

- Industrial Implication: In bioproduction, this means that forcing the cell to use only the efficient pathway might actually slow down growth and overall productivity. Engineering strategies must account for this inherent economic trade-off in cellular metabolism [19] [20].

Quantitative Data on Metabolic Burden

The following tables summarize experimental data that quantify the impact of recombinant protein production on microbial hosts, linking cellular fitness to key process economic metrics.

Table 1: Impact of Recombinant Protein Production on Growth Parameters in E. coli [17]

| Host Strain | Growth Medium | Induction Point | Max Specific Growth Rate (μmax, h⁻¹) | Dry Cell Weight (g/L) | Recombinant Protein Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M15 (Control) | LB (Complex) | N/A | 0.60 | 1.80 | N/A |

| M15 (AAR Expressing) | LB (Complex) | Early-Log (OD 0.1) | 0.21 | 1.95 | High at 6h, low at 12h |

| M15 (AAR Expressing) | LB (Complex) | Mid-Log (OD 0.6) | 0.39 | 1.65 | Sustained at 12h |

| M15 (Control) | M9 (Defined) | N/A | 0.20 | 2.40 | N/A |

| M15 (AAR Expressing) | M9 (Defined) | Early-Log (OD 0.1) | 0.07 | 2.55 | High at 6h, low at 12h |

| M15 (AAR Expressing) | M9 (Defined) | Mid-Log (OD 0.6) | 0.13 | 2.10 | Sustained at 12h |

Table 2: Comparison of Strategies to Improve Robustness and Production

| Strategy | Method | Key Outcome / Titer Improvement | Key Trade-off / Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Regulation [18] [1] | Biosensor-controlled down-regulation of a toxic intermediate (FPP) in an isoprenoid pathway. | 2-fold increase in amorphadiene (1.6 g/L). | Requires a specific, well-characterized biosensor. |

| Growth-Driven Production [21] | Making L-tryptophan synthesis the only source of pyruvate. | 2.37-fold increase in L-tryptophan (1.73 g/L). | Requires extensive genome engineering and is pathway-specific. |

| Two-Stage Fermentation [18] | "Nutrition" sensor to decouple growth and vanillic acid production. | 2.4-fold lower metabolic burden; robust growth rate. | Requires identification of an appropriate sensor and induction trigger. |

| Auxotrophy Complementation [18] | Sequestration of an essential gene (e.g., infA) to a plasmid. |

Stable plasmid maintenance over >95 generations without antibiotics. | Can be burdensome if expression levels are not optimized. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Metabolic Burden via Growth Profiling and Proteomics

This protocol is used to quantitatively evaluate the impact of pathway engineering on host cell fitness [17].

- Strain Preparation: Clone your gene of interest into an appropriate expression vector (e.g., pQE30 with a T5 promoter). Transform into your production host (e.g., E. coli M15) and a control strain containing an empty vector.

- Culture Conditions: Inoculate test and control strains in both a complex medium (e.g., LB) and a defined minimal medium (e.g., M9 with a carbon source). Use multiple replicates.

- Induction Strategy: Induce recombinant protein expression at different growth phases (e.g., early-log phase at OD600 ~0.1 and mid-log phase at OD600 ~0.6).

- Data Collection:

- Growth Kinetics: Monitor OD600 periodically to plot growth curves and calculate the maximum specific growth rate (μmax).

- Biomass Yield: Measure the Dry Cell Weight (DCW) at the stationary phase.

- Proteomic Analysis: Harvest cells at specific time points (e.g., mid-log and late-log). Perform cell lysis, protein extraction, and tryptic digestion. Analyze peptides using LC-MS/MS for label-free quantification (LFQ) proteomics to identify global changes in protein expression.

- Data Analysis: Compare μmax and DCW between test and control strains to quantify burden. Analyze proteomic data to identify significantly up- or down-regulated proteins and pathways (e.g., stress responses, ribosomal proteins).

Protocol 2: Implementing a Dynamic Control System to Balance Metabolism

This protocol outlines steps to implement a biosensor-based feedback loop to avoid metabolite toxicity [18] [1].

- Identify a Critical Metabolite: Choose a pathway intermediate that is toxic or indicative of metabolic imbalance (e.g., Farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) in isoprenoid production).

- Select or Engineer a Biosensor: Identify a transcription factor that naturally responds to your target metabolite or engineer one via directed evolution.

- Circuit Design: Place the biosensor's promoter upstream of a gene whose product can relieve the bottleneck (e.g., an enzyme that consumes the toxic intermediate) or down-regulate a upstream pathway gene.

- Integration and Testing: Integrate the genetic circuit into your production host. Characterize the dynamic response by measuring the intermediate levels, product titer, and host growth with and without the control system.

- Fermentation Validation: Test the performance of the engineered strain in a bioreactor under controlled but fluctuating conditions to validate improved robustness.

Visualizing Metabolic Burden and Mitigation Strategies

The following diagrams, created using the specified color palette, illustrate the core concepts and strategies discussed.

Metabolic Burden Causes

Dynamic Regulation

Strain Stability Systems

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Analyzing and Mitigating Metabolic Burden

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Minimal Medium (e.g., M9) | Provides a controlled environment for precise metabolic flux analysis and quantifying nutrient consumption [17]. | Allows tracking of carbon fate to product vs. biomass. |

| Biosensor Transcription Factors | Core component for building dynamic regulation circuits; responds to specific metabolites [18]. | e.g., FapR for fatty acids, LysG for lysine. |

| Toxin-Antitoxin System Plasmids | Enables plasmid maintenance without antibiotics for large-scale, industrially viable processes [18]. | e.g., plasmids containing the yefM/yoeB TA pair. |

| Proteomics Kits (LC-MS/MS ready) | For sample preparation and label-free quantification (LFQ) to analyze global protein expression changes under burden [17]. | Reveals activated stress responses (e.g., stringent, heat shock). |

| Quorum Sensing Signaling Molecules | Used in layered dynamic control systems to coordinate population-level behavior and decouple growth from production [22]. | e.g., AHL (Acyl-Homoserine Lactone). |

Computational and Engineering Tools for Burden Prediction and Alleviation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and how does it help in predicting metabolic behavior? Flux Balance Analysis is a mathematical approach used to find an optimal net flow of mass through a metabolic network that follows a set of instructions defined by the user [23]. It relies on a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM), which is a stoichiometric matrix (S) of all metabolic reactions. FBA predicts growth or production rates by assuming a metabolic quasi-steady state and solving a linear programming problem [24]: [ \max \{ c(\mathbf{v}): \mathbf{Sv} = 0, \mathbf{LB} \leq \mathbf{v} \leq \mathbf{UB} \} ] where v is the vector of metabolic fluxes, and LB and UB are lower and upper flux bounds. This helps in identifying essential genes and predicting the impact of genetic perturbations on growth and chemical production, which is vital for designing strains with reduced metabolic burden [24].

Q2: Why does my metabolic model fail to produce biomass, and how can I fix it? Draft metabolic models often lack essential reactions due to missing or inconsistent annotations, particularly in transporters, preventing biomass production [25]. This is resolved via gapfilling, a process that compares your model to a reaction database to find a minimal set of reactions whose addition enables growth. KBase's gapfilling algorithm uses Linear Programming (LP) to minimize the sum of flux through added reactions, prioritizing biologically relevant reactions [25]. To perform gapfilling:

- Choose an appropriate media condition: Gapfilling on minimal media ensures the algorithm adds the necessary reactions for biosynthesizing essential substrates.

- Run the gapfilling app: The tool identifies and adds missing reactions.

- Inspect the solution: Review added reactions in the output table's "Gapfilling" column and manually curate if necessary [25].

Q3: What media condition should I use for gapfilling my model? The choice of media is critical. Using "Complete" media (an abstraction where every compound with a known transporter is available) will result in a model with maximal transport capabilities. However, for a more realistic and minimal model, it is often better to use a defined minimal media that reflects the experimental conditions. This ensures the gapfilling algorithm adds only the reactions necessary for growth on that specific media, preventing the model from becoming overly permissive [25]. Multiple gapfilling runs on different media can be stacked to create a robust model.

Q4: My model predicts growth, but my experimental results show poor cell performance. What could be the cause? This discrepancy often stems from metabolic burden, where the host's limited resources are over-diverted to engineered pathways, causing a deep drop in biosynthetic performance known as the "metabolic cliff" [4]. FBA alone may not capture these kinetic and regulatory limitations. To address this:

- Consider using Dynamic FBA (DFBA), which incorporates time-varying metabolite concentrations and fluxes [24].

- Explore a Division of Labor (DoL) strategy using microbial consortia, where different strains or species share the metabolic load to improve overall productivity and stability [4].

Q5: What are the key open-source Python tools for constraint-based modeling? The COBRA (Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) community has developed several Python packages. COBRApy is the core package for handling models and basic simulations [26]. The table below lists essential tools for various tasks.

Table 1: Key Python Packages for Constraint-Based Modeling

| Category | Method | Software Package |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling Framework | Object-oriented programming | COBRApy [26] |

| Reconstruction | Template-based, gap-filling | CarveMe [26] |

| Flux Analysis | FBA, FVA, Knockout simulations | COBRApy [26] |

| Strain Design | OptKnock, OptGene | Cameo [26] |

| Omics Integration | E-flux, iMAT, GIMME | Troppo, ReFramed [26] |

| Dynamic Modeling | Dynamic FBA | dfba [26] |

| Model Testing | Model quality and consistency | MEMOTE [26] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Gapfilling Errors and Solutions

Table 2: Common Gapfilling Issues and Resolutions

| Error Message / Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Infeasible problem" during gapfilling. | The model's constraints are too tight, leaving no solution space for biomass production. | Loosen flux bounds (especially for uptake reactions); verify the biomass reaction is correctly formulated. |

| Gapfilling adds biologically irrelevant reactions. | The algorithm's cost function may be penalizing the wrong reactions. | Manually inspect the gapfilling solution and use "Custom flux bounds" to force unwanted reactions to zero, then re-run gapfilling [25]. |

| Model grows on complete media but not on minimal media. | Missing biosynthetic pathways for essential nutrients not present in the minimal media. | Perform a new gapfilling run specifically on the minimal media condition to add the necessary biosynthesis reactions [25]. |

| Gapfilled model is too large and contains many non-specific transporters. | Using "Complete" media for gapfilling, which allows all possible compounds to be transported. | Re-gapfill the original draft model using a defined minimal media to obtain a more realistic and parsimonious model [25]. |

Simulation Errors and Solutions

| Error Message / Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Model does not contain any reactions" after import. | The model was imported without being associated with a genome, preventing reaction inference. | During model import, use the advanced options to select the associated genome in KBase [25]. |

| FBA predicts zero growth under conditions where growth is expected. | Incorrect media composition or blocked irreversible reactions. | Check the exchange fluxes to ensure nutrients are available. Use Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to identify blocked reactions. |

| Unrealistically high flux through a few reactions. | The model may lack thermodynamic or kinetic constraints. | Apply thermodynamic constraints using packages like ll-FBA or CycleFreeFlux [26] or integrate enzyme capacity constraints. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Building and Validating a Context-Specific Metabolic Model

This protocol outlines the steps for reconstructing a metabolic model from a genome annotation and validating it with experimental data.

1. Genome Annotation:

- Use annotation tools like RAST or PROKKA to identify metabolic genes. RAST is recommended for metabolic modeling as it uses a controlled vocabulary for functional roles that directly map to metabolic reactions [25].

2. Draft Reconstruction:

- Use a template-based reconstruction tool like CarveMe or the KBase Build Metabolic Model app. These tools automatically convert genome annotations into a draft metabolic network [26].

3. Model Gapfilling:

- Run the gapfilling algorithm on a defined minimal media that matches your intended cultivation condition. This adds essential reactions to allow for biomass production [25].

- Inspect the gapfilling solution and manually curate biologically questionable additions.

4. Model Validation:

- Test the model's predictive accuracy by comparing simulated growth phenotypes (on different carbon sources) with experimental data.

- Use Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to assess the flexibility of the network and identify unreachable reactions.

5. Integration of Omics Data:

- Create a context-specific model by integrating transcriptomic or proteomic data using methods like iMAT or GIMME, available in Python packages like Troppo [26]. This removes inactive reactions based on measured expression levels.

The workflow below visualizes this process.

Protocol: Simulating Metabolic Interactions in a Consortium

Microbial consortia can relieve metabolic burden through division of labor. This protocol uses FBA to simulate a two-species consortium.

1. Define Consortium Structure:

- Identify the metabolic roles for each member (e.g., Species A degrades cellulose; Species B produces the target chemical).

2. Build Individual Models:

- Reconstruct separate GEMs for each species using the protocol in 3.1.

3. Create a Compartmentalized Community Model:

- Combine the two models into a single model, keeping their metabolic networks in separate compartments but linked via a shared extracellular compartment.

- Add exchange reactions for the cross-fed metabolites (e.g., glucose from Species A to Species B).

4. Define a Community Objective:

- The objective function can be to maximize the total biomass of the consortium or the flux of a specific product secreted by one member [27].

5. Simulate and Analyze:

- Run FBA on the community model.

- Analyze the flux distribution to verify metabolic interaction (e.g., uptake of partner's byproduct) and assess the productivity gain compared to a monoculture.

The logical relationship and metabolite exchange in such a consortium is shown below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Databases for Metabolic Modeling

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| KBase | An integrated platform for systems biology. | Provides apps for building, gapfilling, and simulating metabolic models without command-line expertise [25]. |

| COBRApy | A Python package for constraint-based modeling. | The core library for creating, manipulating, and simulating metabolic models in Python [26]. |

| ModelSEED Biochemistry Database | A curated database of biochemical reactions and compounds. | Used as the underlying biochemistry for models built in KBase and CarveMe; essential for gapfilling [25]. |

| CarveMe | A tool for automated genome-scale model reconstruction. | Uses a top-down approach to carve models from a universal template, suitable for high-throughput work [26]. |

| MEMOTE | A tool for testing and evaluating genome-scale model quality. | Checks model consistency, syntax, and mass/charge balance to ensure model quality [26]. |

| Cameo | A Python-based strain design and modeling platform. | Provides methods for predicting gene knockout and overexpression targets to optimize production strains [26]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common sources of error when integrating transcriptomic data with my GEM, and how can I avoid them?

Errors often stem from mis-annotation between gene identifiers in your transcriptomic dataset and those in the GEM's gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules.

- Solution: Implement a rigorous identifier cross-mapping protocol. Use reliable bioinformatics tools and databases to ensure the genes measured in your transcriptomics experiment (e.g., from RNA-seq) correctly map to the gene IDs in the GEM. Manually curate a subset of critical genes to verify the automated mapping is accurate. Inconsistent identifier handling is a primary reason for failed integration [28].

FAQ 2: My model predictions are inconsistent with experimental fluxomics data. What should I check first?

First, verify that your GEM contains the metabolic reactions and pathways relevant to your experimental conditions.

- Solution: Perform a gap-filling analysis. Compare the fluxes measured in your fluxomics experiments (e.g., using 13C-metabolic flux analysis) against the network topology of your GEM. If certain active fluxes are not supported by your model, you may need to add missing reactions based on genomic evidence or biochemical literature. This ensures the model can accurately represent the observed metabolic phenotype [29] [30].

FAQ 3: How can I design a multi-omics experiment that is optimally suited for integration with GEMs?

A successful design ensures all omics data layers are generated from the same biological system under the same conditions.

- Solution: Carefully consider sample collection, processing, and storage from the outset. For example, blood, plasma, or tissue samples that can be rapidly processed and frozen are excellent for generating high-quality multi-omics data for genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. The experimental design must account for the specific biomass requirements and sample handling needs of each omics platform to enable direct comparison and integration [28].

FAQ 4: What strategies can I use to reduce the metabolic burden on my engineered host, as predicted by GEM simulations?

Metabolic burden arises from resource competition between the host's native functions and the introduced heterologous pathways.

- Solution: Employ dynamic pathway regulation. Use biosensors to autonomously control metabolic fluxes, decoupling cell growth from product synthesis. For instance, dynamic regulation of a toxic intermediate like farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) in isoprenoid production has been shown to double the final titer. Alternatively, growth-driven or product-addiction strategies can couple the production of the target compound with host fitness, enhancing long-term stability [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Prediction Accuracy of Gene Essentiality

Problem: Your GEM incorrectly predicts whether a gene is essential or non-essential for growth under a defined condition.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action | Reference / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Verify GPR Rules | Manually inspect the Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations for the reactions linked to the gene in question. Ensure Boolean logic (AND, OR) accurately reflects enzyme complexes and isoenzymes. | Incorrect GPR logic is a common source of error in essentiality predictions [30]. |

| Check for Missing Reactions | Investigate if a gap in the network is causing the prediction failure. Use experimental data (e.g., observed growth) to identify and add missing bypass reactions. | GEMs are based on known biochemistry; gaps lead to false essentiality predictions [29]. |

| Validate Exchange Reactions | Confirm that all necessary nutrients (carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus sources, etc.) are available to the model via the extracellular medium definition. | An essential nutrient might be missing from the growth medium in the simulation [30]. |

Issue 2: Integrating Heterogeneous Omics Data Types

Problem: Difficulty in combining data from different omics platforms (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) into a single, constrained model.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action | Reference / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Data Normalization | Apply appropriate scaling, normalization, and transformation techniques to each omics dataset individually before integration. | Omics datasets have inherent technical variations and require different pre-processing levels [29]. |

| Context-Specific Model Reconstruction | Use algorithms like INIT / MBA or iMAT to create a condition-specific model by integrating your omics data as constraints. | These methods extract the most relevant sub-network from a generic GEM, improving prediction accuracy for a specific context [30]. |

| Pathway Enrichment Analysis | First, analyze each omics dataset independently to identify significantly altered pathways, then look for consensus pathways to integrate. | A two-stage approach helps identify key biological processes before complex data integration [31]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating a Context-Specific Model using Transcriptomic Data

This protocol details how to build a tissue- or condition-specific metabolic model from a generic GEM using transcriptomics data.

1. Prepare Your Data and Model:

- Obtain a high-quality, generic GEM for your organism (e.g., Recon for human, iML1515 for E. coli).

- Prepare your transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-seq TPM or FPKM values) from the specific context of interest.

2. Pre-process Transcriptomic Data:

- Normalize the data and map gene identifiers to those used in the generic GEM.

- Convert expression values into a binary (on/off) reaction activity list or continuous scores using a thresholding method.

3. Reconstruct the Context-Specific Model:

- Use a reconstruction algorithm such as INIT (Integrative Network Inference for Tissues) or iMAT (integrative Metabolic Analysis Tool).

- These algorithms use the transcriptomic data to extract a sub-network from the generic model that is most consistent with the expression data, while maintaining network functionality (e.g., production of biomass precursors).

4. Validate and Simulate:

- Validate the resulting model by testing its predictions against known metabolic functions of the tissue or condition.

- Use the context-specific model for flux balance analysis (FBA) to make predictions.

Protocol 2: Implementing Dynamic Regulation to Alleviate Metabolic Burden

This protocol outlines the use of biosensors for dynamic metabolic control to prevent the accumulation of toxic intermediates and improve production robustness.

1. Identify Target and Biosensor:

- Identify a toxic intermediate or key metabolite in your pathway that causes metabolic imbalance.

- Select or engineer a biosensor (e.g., a transcription factor) that specifically responds to the concentration of this target metabolite.

2. Construct Dynamic Control Circuit:

- Genetically link the output of the biosensor to the regulation of a critical gene in the pathway. For example, a high concentration of a toxic intermediate should repress the expression of upstream genes.

- This creates a feedback loop that autonomously adjusts metabolic flux.

3. Test and Characterize:

- Introduce the constructed dynamic control system into your production host.

- Characterize the system's performance in lab-scale fermenters, measuring target product titer, biomass yield, and intermediate accumulation over time.

4. Compare to Static Control:

- Perform a parallel fermentation with a control strain using static, constitutive expression.

- The dynamic regulation strain should show reduced metabolic burden, evidenced by more robust growth and higher final product titers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function in GEMs & Multi-Omics Integration | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| GEM Reconstruction Tools | Automated and semi-automated construction of genome-scale metabolic models from annotated genomes. | Over 6,000 models have been generated using tools like ModelSEED and RAVEN, covering bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes [29] [30]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | A mathematical optimization technique to predict metabolic flux distributions in a GEM under steady-state assumptions. | Uses linear programming; commonly optimized for objectives like biomass maximization. Constrained by uptake/secretion rates [29] [30]. |

| Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) | A comprehensive software toolbox for performing GEM reconstruction, simulation, and analysis. | Provides functions for FBA, gene knockout analysis, and omics data integration. Available in MATLAB and Python (COBRApy) [30]. |

| Metabolomics Databases | Repositories of metabolite structures, spectral data, and metabolic pathways for compound identification and pathway mapping. | Examples include HMDB, KEGG, and MetaCyT. Essential for annotating metabolomics data and validating GEM predictions [28]. |

| Multi-Omics Integration Algorithms | Algorithms like INIT and iMAT that use omics data to create context-specific models from generic GEMs. | They transform qualitative omics data into quantitative constraints (e.g., reaction presence/absence), improving model accuracy [31] [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary causes of metabolic burden in engineered microbial hosts? Metabolic burden arises from genetic manipulation and environmental perturbations, which can divert cellular resources away from growth and product synthesis. Key factors include the metabolic load from expressing heterologous pathways, the toxicity of pathway intermediates or products, imbalance in cofactors (e.g., redox imbalance), and competition for precursors between the native metabolism and the engineered pathway [18] [3].

FAQ 2: How can I dynamically control metabolic fluxes to prevent the accumulation of toxic intermediates? You can implement dynamic pathway regulation using metabolite-responsive biosensors. For example, in isoprenoid production, a biosensor for the toxic intermediate farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) was used to dynamically regulate its levels, resulting in a two-fold increase in amorphadiene titer (1.6 g/L) [18]. Similarly, bifunctional dynamic control in cis,cis-muconic acid synthesis upregulated the product pathway and downregulated a competing pathway, leading to a 4.7-fold titer increase [18].

FAQ 3: What strategies can decouple cell growth from product formation to improve robustness? Autonomous dynamic control strategies can effectively decouple growth and production. Using nutrient sensors or quorum-sensing systems, production pathways can be activated only after a desired cell density is reached. In one case, a glucose sensor delayed vanillic acid synthesis in E. coli, which reduced metabolic burden by 2.4-fold and maintained a robust growth rate during bioconversion [18]. A layered system combining a myo-inositol biosensor and a quorum-sensing circuit for glucaric acid production also successfully decoupled growth from production, increasing the titer 5-fold [18].

FAQ 4: How can I improve the genetic stability of my engineered strain without relying on antibiotics? Several plasmid maintenance strategies can replace antibiotic selection:

- Toxin/Antitoxin (TA) System: A stable toxin gene is integrated into the genome, while the antitoxin gene is placed on the plasmid. Only cells retaining the plasmid survive. This was used in Streptomyces for stable protein production over 8 days [18].

- Auxotrophy Complementation: An essential gene for growth (e.g., infA) is deleted from the chromosome and provided in trans on the plasmid. Cells that lose the plasmid cannot grow [18].

- Operator-Repressor Titration (ORT) and RNA-based systems also offer alternative methods for maintaining plasmid stability [18].

FAQ 5: Can pathway engineering be applied to cell-free biosynthesis systems? Yes, metabolic rewiring in live cells directly enhances the performance of cell-free systems constituted from their extracts. In one study, S. cerevisiae was rewired using multiplexed CRISPR-dCas9 to downregulate competing genes (ADH1,3,5, GPD1) and upregulate a beneficial gene (BDH1) for 2,3-butanediol (BDO) production. Extracts from this rewired strain showed a 46% increase in BDO yield and a 32% reduction in ethanol byproduct compared to extracts from the unmodified strain [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Product Titer Due to Competition from Native Pathways

- Potential Cause: Essential precursor molecules are being diverted into native metabolic pathways instead of your desired product.

- Solution: Eliminate or downregulate competing native pathways.

- Protocol: Use multiplexed CRISPR-dCas9 to simultaneously downregulate multiple competing genes.

- Identify Targets: Use genome-scale models or literature to identify genes that consume your key precursor (e.g., ADH genes for acetyl-CoA diversion).

- Design sgRNAs: Design single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting the promoter or coding regions of the competing genes (e.g., ADH1, ADH3, ADH5, GPD1).

- Construct Plasmid: Clone the sgRNA sequences into a plasmid expressing dCas9 (e.g., a repressive dCas9 variant).

- Transform and Validate: Introduce the plasmid into your production host and validate transcriptional downregulation via qPCR [32].

- Protocol: Use multiplexed CRISPR-dCas9 to simultaneously downregulate multiple competing genes.

Problem: Accumulation of Toxic Intermediates or Metabolic Imbalance

- Potential Cause: The engineered pathway produces a metabolite that inhibits growth or causes redox imbalance, reducing overall host robustness.

- Solution: Implement dynamic metabolic balancing.

- Protocol: Employ a biosensor-based feedback system to regulate pathway expression.

- Select a Biosensor: Choose a transcription factor or riboswitch that responds to your toxic intermediate (e.g., a biosensor for FPP).

- Link to Output: Place the expression of a rate-limiting or detoxifying enzyme under the control of the biosensor-responsive promoter.

- Integrate System: Incorporate the biosensor system into the host chromosome or a stable plasmid.

- Test and Optimize: Characterize the dynamic response in shake flasks and monitor for reduced intermediate accumulation and improved titer [18].

- Protocol: Employ a biosensor-based feedback system to regulate pathway expression.

Problem: Genetic Instability and Loss of Production Phenotype

- Potential Cause: The engineered pathway imposes a metabolic burden, leading to a competitive advantage for cells that lose the pathway through plasmid loss or mutations.

- Solution: Couple product synthesis to host growth via a "product-addiction" system.

- Protocol: Make host survival dependent on the production of the target compound.

- Choose Essential Genes: Select one or two essential genes (e.g., folP, glmM).

- Place Under Control: Put the expression of these essential genes under the control of a biosensor that is activated by your target product.

- Delete Genomic Copies: Delete the native, constitutive copies of the essential genes from the chromosome.

- Validate Stability: Perform long-term serial passaging without selection pressure and measure the percentage of cells that retain high production capacity [18]. This strategy has been shown to maintain mevalonate production stability for over 95 generations.

- Protocol: Make host survival dependent on the production of the target compound.

Experimental Data and Protocols

Table 1: Selected Examples of Metabolically Engineered Production Strains

| Target Product | Host Organism | Key Metabolic Engineering Strategy | Maximum Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g glucose) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Hydroxypropionic Acid | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Substrate & Genome Editing Engineering | 62.6 | 0.51 | [33] |

| L-Lactic Acid | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Modular Pathway Engineering | 212 | 0.98 | [33] |

| Succinic Acid | E. coli | Modular Pathway Engineering & High-Throughput Genome Editing | 153.36 | N/A | [33] |

| Lysine | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Cofactor & Transporter Engineering | 223.4 | 0.68 | [33] |

| Pyrogallol | E. coli | Fine-tuning expression of aroL, ppsA, tktA, aroGfbr to balance flux | 0.893 | N/A | [18] |

Protocol: Enhancing Precursor Supply via Growth-Coupling

This protocol forces the cell to channel carbon flux through your production pathway to sustain growth, thereby enhancing precursor availability and genetic stability [18].

- Precursor Identification: Identify a key precursor in your pathway that is also central to the host's metabolism (e.g., pyruvate, acetyl-CoA).

- Map Alternative Routes: Use a genome-scale model to identify all native reactions that generate this precursor.

- Gene Knockouts: Systematically delete the major native pathways that generate the precursor (e.g., for a pyruvate-driven system, delete pyruvate-generating genes like ppsA).

- Implement Rescue Pathway: Ensure your heterologous production pathway contains a step that regenerates the essential precursor.

- Validate Growth-Coupling: Test the engineered strain in minimal media. Growth should be contingent on the operation of your production pathway. This approach has been used to increase L-tryptophan and cis,cis-muconic acid titers by over 2-fold [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Pathway Engineering and Rewiring

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-dCas9 System | Multiplexed transcriptional repression or activation of target genes. | Downregulation of ADH1,3,5 and GPD1; upregulation of BDH1 in S. cerevisiae [32]. |

| Metabolite-Responsive Biosensors | Dynamic monitoring and regulation of intracellular metabolite levels. | Farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) biosensor for isoprenoid production [18]. |

| Toxin/Antitoxin (TA) System | Plasmid maintenance and genetic stability without antibiotics. | yefM/yoeB TA pair used in Streptomyces for stable protein production [18]. |

| Quorum Sensing Systems | Cell-density-dependent gene expression for decoupling growth and production. | AHL-based system used in layered dynamic control for glucaric acid production [18]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico prediction of gene knockout targets and flux distributions. | Model-driven identification of gene knockouts for cubebol, L-threonine, and L-valine production [33]. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for constructing robust microbial cell factories, integrating key strategies from hierarchical metabolic engineering.

Figure 2: The five hierarchies of metabolic engineering, from fine-tuning individual components to optimizing the entire cellular system [33].

Core Concepts: Overcoming Metabolic Burden with Synthetic Circuits

What is "metabolic burden" and why is it a central challenge in engineering microbial cell factories?

Metabolic burden refers to the stress imposed on a host organism when its metabolic resources are diverted from natural growth and maintenance toward the production of a desired recombinant product [3] [1]. This rewiring of metabolism can lead to adverse physiological effects, including impaired cell growth, reduced protein synthesis, genetic instability, and low product yields [3] [1]. In an industrial context, these symptoms translate to processes that are not economically viable [1]. Synthetic biology addresses this by designing genetic circuits that can dynamically control metabolic flux, thereby balancing the trade-off between cell growth and product synthesis to minimize this burden [34].

How do dynamic regulatory circuits and CRISPR-Cas systems help mitigate metabolic burden?

Traditional, static overexpression of pathway genes often creates a significant metabolic drain. In contrast, dynamic regulatory circuits are self-contained genetic systems that can sense the intracellular metabolic state and automatically adjust pathway gene expression in response [34]. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) provides a powerful tool for building these circuits. Using a nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9) and programmable guide RNAs (sgRNAs), CRISPRi can precisely repress target genes without altering the DNA sequence [35] [36]. This allows for the construction of circuits that dynamically re-route metabolic flux, prevent the accumulation of toxic intermediates, and manage resource allocation between host and pathway, leading to more robust and efficient microbial cell factories [35] [34].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Circuit Design and Implementation

FAQ 1: My microbial host shows severe growth retardation after introducing the production pathway. How can a genetic circuit help?

Answer: Growth retardation is a classic symptom of metabolic burden, where resources like energy, amino acids, and ribosomes are hijacked for heterologous production [1]. A well-designed dynamic circuit can decouple growth from production.

- Solution: Implement a growth-switch circuit. This circuit design keeps the production pathway repressed during the active growth phase. It senses a marker of metabolic stress or a specific growth phase (e.g., oxygen depletion or entry into stationary phase) and then activates the production pathway.

- Protocol:

- Identify a Sensor: Select a native promoter that is activated by your chosen metabolic signal (e.g., a promoter responsive to ATP levels, nutrient starvation, or the stationary phase sigma factor).

- Design the Actuator: Clone the key genes of your production pathway under the control of a promoter that is repressed by dCas9-sgRNA complexes (CRISPRi).

- Build the Circuit: Express the sgRNA from the sensor promoter you identified. Thus, only when the metabolic signal is present will the sgRNA be produced, lifting dCas9-mediated repression and activating the production pathway [34].

- Expected Outcome: Higher peak cell densities are achieved because growth is not impeded by the production pathway early on, ultimately leading to higher overall product titers.

FAQ 2: My product yields are unstable, especially in long-term fermentations. What could be the issue?

Answer: Instability often arises from genetic mutations that inactivate the circuit or the production pathway, as cells evolve to alleviate the metabolic burden [1]. A circuit that reduces this burden can enhance genetic stability.

- Solution: Use CRISPRi for dynamic flux control to avoid the accumulation of toxic intermediates or extreme depletion of central metabolites, which are strong drivers of mutation.

- Protocol:

- Identify the Bottleneck: Use metabolic modeling or flux analysis to pinpoint a critical node in your pathway where flux imbalance is likely.

- Design a Sensor-Actuator System: Employ a transcription factor-based biosensor that is activated by an early intermediate in your pathway.

- Implement Feedback Repression: Have this biosensor control the expression of a sgRNA that targets a gene earlier in the pathway (e.g., the first committed step). This creates a negative feedback loop: when the intermediate accumulates, it signals the circuit to temporarily slow down the pathway's influx, preventing overload [34].

- Expected Outcome: A more stable population and consistent production over time, as the circuit maintains metabolism within a manageable range, reducing the selective pressure for mutants.

FAQ 3: My CRISPRi-based repression is leaky, leading to poor circuit performance. How can I improve it?

Answer: Leaky expression can be caused by suboptimal sgRNA design, insufficient dCas9 levels, or inappropriate binding site positioning.

- Solution: Systematically optimize the CRISPRi components.

- Protocol:

- sgRNA Design: Use validated software (e.g., CHOPCHOP, Synthego's tool) to design sgRNAs with high on-target efficiency. Ensure a GC content between 40-80% for stability [37]. Consider using truncated sgRNAs (tru-gRNAs) to potentially enhance specificity [36].

- Binding Site Placement: For transcriptional repression, place the dCas9 binding site within the promoter region or the early part of the coding sequence (CDS). The binding site should be as close as possible to the transcription start site for optimal steric hindrance [35] [36].

- dCas9 Expression: Ensure strong, constitutive expression of dCas9. Use a high-copy plasmid or genomic integration and test different ribosomal binding sites (RBS) to tune translation efficiency. Consider using hypercompact Cas proteins (e.g., CasΦ) to reduce the metabolic load of expressing the effector protein itself [35].

- Expected Outcome: A higher fold-repression (dynamic range) leading to tighter control and more predictable circuit behavior.

FAQ 4: I'm observing high variability in circuit output between individual cells. How can I improve robustness?

Answer: Cell-to-cell variability can stem from context-dependency of genetic parts, plasmid copy number variation, and insufficient transcriptional insulation.

- Solution: Apply principles of modular and orthogonal design to minimize context effects and cross-talk.

- Protocol:

- Transcriptional Insulation: Separate all transcriptional units with strong terminators. Incorporate 200 bp spacer sequences between units to further prevent read-through [36].

- mRNA Processing: Use the Csy4 ribonuclease system to cleave polycistronic transcripts. Flank sgRNAs and other functional RNA elements with Csy4 recognition sequences. This ensures independent function of each RNA component after transcription [36].

- Minimize Replication: Avoid repeated DNA sequences in your circuit design to prevent homologous recombination and plasmid instability [36].