Streamlining Cellular Factories: A CRISPR/Cas9 Guide to Genome Reduction in Microbial Chassis Strains

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of CRISPR/Cas9 for genome reduction in industrial chassis strains, a key strategy in synthetic biology for enhancing microbial production hosts.

Streamlining Cellular Factories: A CRISPR/Cas9 Guide to Genome Reduction in Microbial Chassis Strains

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of CRISPR/Cas9 for genome reduction in industrial chassis strains, a key strategy in synthetic biology for enhancing microbial production hosts. It covers the foundational principles of creating minimal genomes, details advanced methodological workflows for efficient large-scale deletion, and addresses critical troubleshooting for optimizing editing efficiency and strain fitness. Furthermore, it explores state-of-the-art validation techniques and compares CRISPR/Cas9 with alternative editing tools. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and bioprocess engineers, this content synthesizes recent advances to guide the rational design of next-generation, streamlined microbial cell factories for biomanufacturing.

The Rationale for Minimal Genomes: Foundations of Genome Reduction in Synthetic Biology

Defining Chassis Strains and the Concept of Genome Reduction

In synthetic biology, a chassis strain refers to a platform microorganism whose genome has been engineered to optimize it for specific bioindustrial applications. The core concept involves stripping the host organism of non-essential genes and disruptive genetic elements to create a streamlined, predictable, and efficient cellular factory [1]. This process of genome reduction systematically removes redundant sequences to minimize metabolic burden, reduce genetic instability, and eliminate undesirable traits that might interfere with production processes [2]. The resulting minimal genomes provide more computational resources for engineered functions, decrease survival advantages for unengineered revertants in fermenters, and enhance the efficiency of genetic manipulation [1].

Historically, synthetic biology has been biased toward using a narrow set of traditional organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae due to their well-characterized genetics and available engineering toolkits [3]. However, this approach represents a significant design constraint, as numerous other microorganisms in nature possess innate capabilities that make them superior chassis for specific applications. The emerging field of broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology seeks to overcome this limitation by reconceptualizing host selection as an active design parameter rather than a passive default choice [3]. This paradigm shift treats the chassis not merely as a passive platform but as a tunable component that can be rationally selected and optimized to enhance system functionality.

Theoretical Framework and Strategic Approaches

Dual-Track Methodology for Genome Reduction

The construction of reduced genomes follows two complementary engineering trajectories: top-down reduction and bottom-up synthesis [1]. The top-down reductionist approach starts with a naturally occurring genome and sequentially removes targeted genomic regions, debugging abnormalities as they arise. In contrast, the bottom-up synthesis approach involves the de novo chemical synthesis of a customized minimal genome based on computational design principles [1]. Each methodology offers distinct advantages: top-down reduction maintains more native biological functions initially while bottom-up synthesis enables more radical redesign unconstrained by evolutionary history.

Adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) plays multiple critical roles in both approaches, serving to debug system abnormalities, explore emergent properties of minimal genomes, and provide design principles for further genome-scale engineering [1]. This iterative process of design, construction, and testing has enabled researchers to create synthetic phenotypes with enhanced biotechnological performance, establishing genome reduction as a powerful engineering strategy rather than merely an exploratory scientific endeavor.

Rationale for Chassis Specialization

The strategic selection of microbial hosts with specialized innate capabilities represents a fundamental advance in biodesign efficiency [3]. By leveraging native biological traits, synthetic biologists can "hijack" evolved functions rather than engineering them de novo in suboptimal hosts. This host-centric design philosophy recognizes that cellular context significantly influences the behavior of engineered genetic systems through resource allocation, metabolic interactions, and regulatory crosstalk [3].

The chassis effect describes this phenomenon where identical genetic constructs exhibit different performance characteristics across host organisms due to variations in cellular environments [3]. This context dependency arises from the coupling of endogenous cellular activity with introduced genetic circuitry through direct molecular interactions or competition for finite cellular resources. Rather than treating this as an obstacle, BHR synthetic biology leverages host diversity as a tuning parameter to optimize system performance for specific applications [3].

Quantitative Assessment of Reduction Efficiency

Table 1: Efficiency Metrics for Streptomyces Chassis Development

| Automation Module | Manual Operation Time | Automated Operation Time | Time Savings | Throughput per Batch | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conjugation Transfer | ~8.5 hours | 1.7 hours | 80% | 2×96-well plates | ≥80% |

| Conjugant Picking/Subculturing | ~100 minutes | 20 minutes | 80% | 1×96-well plate | N/A |

| Conjugant Replication/Subculturing | ~15 minutes | 3 minutes | 80% | 1×96-well plate | N/A |

| Streptomyces Transfer Fermentation | ~100 minutes | 20 minutes | 80% | 1×96-well plate | N/A |

| Product Detection | ~200 minutes | 40 minutes | 80% | 1×96-well plate | N/A |

| Spore Collection | ~225 minutes | 45 minutes | 80% | 1×96-well plate | N/A |

The development of a genetic manipulation functional island for Streptomyces chassis demonstrates the substantial efficiency gains achievable through automated genome reduction workflows [2]. As shown in Table 1, each automated module saves approximately 80% of the time required for manual operations while maintaining high success rates for critical steps like conjugation transfer (≥80% success with ≥4 single colonies) [2]. This platform enables rapid genome reduction through systematic deletion of non-essential genomic regions, streamlining the host for heterologous production of valuable compounds.

Table 2: Performance Enhancement Through Chassis Engineering

| Chassis Organism | Native Capability Leveraged | Engineering Intervention | Resulting Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces spp. | Secondary metabolite biosynthesis | Introduction of PQQ biosynthesis pathway | Significant increase in natural product yield + new compounds [2] |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009 | Four-mode metabolic versatility | Development as growth-robust chassis | Potential for robust bioproduction across metabolic states [3] |

| Halomonas bluephagenesis | High-salinity tolerance | Engineering for natural product accumulation | Industrial fermentation under non-sterile conditions [3] |

| Cyanobacteria & Microalgae | Photosynthetic capability | Rewiring for biosynthetic production | Value-added compound production from CO₂ and sunlight [3] |

| Thermophiles, Psychrophiles, Halophiles | Environmental stress tolerance | Development as specialized chassis | Robust performance in harsh non-laboratory environments [3] |

CRISPR/Cas9 Toolkit for Genome Reduction

The CRISPR/Cas9 workflow depends on specialized bioinformatics tools for guide RNA design, off-target prediction, and data analysis [4] [5]. These resources form an essential foundation for effective genome reduction projects:

- CRISPOR and CHOPCHOP: Versatile platforms providing robust guide RNA design for multiple species, integrated off-target scoring, and intuitive genomic locus visualization [5].

- CRISPResso: Analysis tool for quantifying genome editing outcomes from sequencing data [4].

- Cas-OFFinder: Predicts potential off-target sites for CRISPR nucleases [4].

- CRISPRDetect: Web-based tool that automatically detects, predicts, and refines CRISPR arrays in genomes, enabling precise detection of CRISPR arrays, their orientation, and repeat-spacer boundaries [5].

- CRISPRidentify: Employs machine learning to identify and distinguish genuine CRISPR arrays from false positives with higher specificity than previous tools [5].

- CRISPR-Cas Atlas: Exhaustively mined resource containing 1,246,088 CRISPR-Cas operons from 26.2 terabases of assembled microbial genomes and metagenomes, significantly expanding known natural diversity [6].

Advanced CRISPR Systems

Recent advances have dramatically expanded the CRISPR toolbox beyond the original Cas9 system. Artificial-intelligence-enabled design has emerged as a powerful approach to generate editors with optimal properties [6]. The OpenCRISPR-1 system, designed using large language models trained on biological diversity, demonstrates comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 while being 400 mutations away in sequence [6]. This AI-generated editor exhibits compatibility with base editing and represents a significant milestone in moving beyond natural evolutionary constraints.

CRISPR Genome Reduction Workflow

Application Notes: Streptomyces Chassis Development

Protocol for High-Throughput Genome Reduction

Background: Streptomyces produces over 80% of antibiotic drugs on the market, yet over 90% of its secondary metabolic gene clusters remain undeveloped [2]. Heterologous expression represents the primary approach for exploiting these resources, creating an urgent need for streamlined Streptomyces chassis.

Methodology: The protocol utilizes a genetic manipulation functional island with automated processes including conjugation transfer, conjugant subculturing, spore collection, conjugant fermentation, and product detection [2]. Key steps include:

Identification of target genes for deletion through co-evolution analysis with polyketide synthases, identifying 597 genes across functional families including transcription, transport, cofactors, fatty acid synthesis, and metal ion transport [2].

Design of specific guide RNAs using tools such as CRISPOR or CHOPCHOP, with careful attention to avoid off-target effects in the complex Streptomyces genome [5].

Implementation of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion through the automated conjugation transfer system, achieving ≥80% success rate with generation of ≥4 single colonies [2].

Phenotypic validation of reduced strains through fermentation and product detection assays to ensure maintenance of desired production capabilities [2].

Outcome Analysis: Application of this protocol led to the identification of the pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) gene from the "cofactor" family. Introducing the PQQ biosynthesis pathway into multiple actinomycete strains significantly increased natural product yield and generated several new compounds with pharmaceutical value [2]. This demonstrates how targeted genome reduction can enhance rather than diminish functional capabilities when strategically applied.

Protocol for Enhanced Editing Efficiency in Challenging Systems

Background: Standard CRISPR editing efficiency varies dramatically across systems, complicating strain development [7]. This protocol addresses this limitation through synthetic guide sequences and intermediate entry strains.

Methodology:

Creation of entry strains using efficient, well-characterized guide RNA sequences when possible. For situations where standard markers (e.g., dpy-10) are unsuitable due to genomic linkage or other conflicts, employ synthetic guide sequences not present in the native genome [7].

Utilization of the synthetic guide sequence GCTATCAACTATCCATATCG for C. elegans, demonstrated to achieve knock-in efficiency of 1-11% - lower than optimal natural guides but sufficient for most applications [7].

Leveraging antibiotic resistance-based selection (FAB-CRISPR) for mammalian cells, using resistance cassettes for rapid selection and enrichment of gene-edited cells when working with eukaryotic chassis systems [8].

Technical Notes: This approach is particularly valuable for generating entry strains where standard guide sequences are unsuitable, expanding the range of organisms amenable to efficient genome reduction [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Mediated Genome Reduction

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Effectors | OpenCRISPR-1 (AI-designed), SpCas9, Cas12a | Core editing machinery with varying PAM requirements, sizes, and specificities [6] |

| Delivery Systems | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), Viral Vectors | Transport CRISPR components to target cells; LNPs enable redosing unlike viral vectors [9] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CRISPOR, CHOPCHOP, CRISPResso, CRISPRDetect | gRNA design, off-target prediction, data analysis, and CRISPR array detection [4] [5] |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance cassettes, dpy-10, synthetic guides | Enrichment of edited cells; synthetic guides avoid genomic conflicts [7] [8] |

| Host Organisms | Streptomyces spp., E. coli, C. elegans, Halomonas bluephagenesis | Specialized chassis with unique capabilities for different applications [3] [2] |

| Analysis Databases | CRISPR-Cas Atlas, CRISPRdb, CRISPR-Casdb | Comprehensive storage and comparison of annotated CRISPR data [6] [5] |

Chassis Selection Decision Tree

Concluding Remarks

The strategic development of chassis strains through genome reduction represents a paradigm shift in synthetic biology, moving from opportunistic use of existing microorganisms to rational design of optimized cellular platforms. The integration of CRISPR/Cas9 technologies with bioinformatics resources and automated workflows has dramatically accelerated this process, enabling researchers to create specialized hosts with enhanced performance characteristics [2]. The emerging methodology of treating host selection as an active design parameter rather than a default choice opens new possibilities for biotechnological innovation [3].

Future directions will likely see increased use of AI-designed editors like OpenCRISPR-1 [6], expanded application of BHR principles to access untapped microbial capabilities, and more sophisticated integration of top-down and bottom-up genome engineering approaches [1]. As these tools and methodologies mature, the development of highly specialized chassis strains will continue to transform biomanufacturing, therapeutic development, and sustainable production across diverse industrial sectors.

In the construction of microbial cell factories for therapeutic compound production, achieving high product titers, robust yields, and genetic stability is paramount. Genome reduction in chassis strains eliminates non-essential genes, streamlines metabolic networks, and removes competing pathways, thereby enhancing metabolic efficiency. The application of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized this process, enabling precise, multiplexed genome modifications that were previously infeasible with traditional methods. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols, framed within thesis research on CRISPR/Cas9 for genome reduction, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in constructing optimized chassis strains.

Key Quantitative Data on CRISPR-Cas9 Enhanced Strain Performance

The following table summarizes quantitative outcomes from recent studies where CRISPR/Cas9 systems were leveraged to enhance microbial production strains.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Strain Engineering

| Organism | Engineering Goal | CRISPR Tool / Strategy | Key Performance Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Enhanced biosynthesis of ergothioneine and cordycepin | IMIGE system (iterative multi-copy integration via δ and rDNA sites) | 407.39% and 222.13% yield increase vs. episomal expression; titers of 105.31 mg/L and 62.01 mg/L [10]. | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | General optimization of genome editing efficiency | SCR1-tRNA promoter for sgRNA; KU70 deletion; iCas9 (Cas9D147Y, P411T) | Gene disruption efficiency of 92.5%; dual gene disruption at 57.5%; integration efficiency boosted to 92.5% [11]. | |

| Oryza sativa (Rice) | Increased grain yield | CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis of the An-1 gene | Homozygous mutants showed >30% increased yield per plant, with 34.8% more spikelets per panicle [12]. | |

| S. cerevisiae | De novo synthesis of homogentisic acid (HGA) | YaliCraft toolkit for marker-free, multi-locus integration | Production of 373.8 mg/L HGA from glucose; characterization of a library of 137 promoters [13]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: CRISPR/Cas9-based Iterative Multi-copy Integration for Metabolite Yield Improvement

This protocol, adapted from Chen et al., describes the IMIGE system for rapidly engineering Saccharomyces cerevisiae to achieve high-level metabolite production [10].

Objective: To iteratively integrate multiple copies of key biosynthetic genes into the repetitive δ and rDNA sequences of the S. cerevisiae genome to significantly enhance the production of target metabolites like ergothioneine and cordycepin.

Materials:

- Plasmids: Cas9-sgRNA expression vector(s); donor DNA construct containing the target gene and homologous arms for δ or rDNA sites.

- Strains: E. coli for plasmid propagation; S. cerevisiae production host strain.

- Reagents: Standard yeast culture media (e.g., YPD, SC); PEG/LiAc transformation kit; reagents for PCR verification.

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design and Vector Construction: Design sgRNAs to target the specific δ or rDNA genomic loci. Clone the sgRNA expression cassette into a Cas9-expressing vector.

- Donor DNA Assembly: Assemble the donor DNA fragment containing your gene of interest (GOI) flanked by homology arms (~500 bp) specific to the chosen δ or rDNA site. The system uses a split-marker strategy for efficient in vivo assembly.

- Co-transformation: Co-transform the S. cerevisiae host strain with the Cas9-sgRNA vector and the donor DNA fragment using a standard LiAc/PEG method.

- Screening and Selection: Plate transformations on appropriate selective media. Screen for successful integrants using colony PCR with verification primers that check for the 5' and 3' junctions of the integrated DNA.

- Curing the Cas9 Plasmid: For the next integration cycle, the Cas9-sgRNA plasmid must be cured from the strain. This is achieved by growing positive clones in non-selective media for several generations and then replica-plating to confirm the loss of the plasmid marker.

- Iterative Integration: Repeat steps 1-5 for subsequent rounds of integration, either at the same locus or a different one (e.g., δ sequence followed by rDNA), using growth-related phenotypes for rapid screening. The entire process for two screening cycles can be completed in 5.5-6 days [10].

Troubleshooting:

- Low Integration Efficiency: Optimize the length and specificity of the homology arms. Ensure the Cas9-sgRNA complex has high activity by testing different sgRNA sequences.

- Failure to Cure Plasmid: Increase the number of generations in non-selective media. Consider using a counterselectable marker on the Cas9 plasmid.

Protocol: Optimizing CRISPR/Cas9 Editing Efficiency in Non-Conventional Yeasts

This protocol, based on the work in Yarrowia lipolytica, outlines strategies to overcome low homologous recombination efficiency, a common challenge in non-conventional chassis strains [11] [13].

Objective: To achieve high-efficiency gene disruption and marker-free integration in yeast strains with robust non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathways.

Materials:

- Vectors: Plasmids for expressing codon-optimized Cas9 and sgRNA.

- Strains: Target yeast strain (e.g., Y. lipolytica).

- Reagents: Components for protoplast transformation or electroporation.

Procedure:

- sgRNA Expression Optimization: Use a synthetic RNA Polymerase III promoter like SCR1-tRNA for sgRNA expression. This architecture, which processes the sgRNA via tRNA, has been shown to achieve disruption efficiencies of 92.5% and enables efficient multiplexing [11].

- Enhancing Homologous Recombination (HR):

- Employ High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Use engineered Cas9 variants like iCas9 (Cas9D147Y, P411T), which has been demonstrated to enhance both gene disruption and genome integration efficiency compared to wild-type Cas9 [11].

- Toolkit-Based Assembly: Utilize modular toolkits like YaliCraft to streamline the cloning process. This allows for easy swapping of homology arms, rapid gRNA re-encoding via E. coli recombineering, and quick transition between marker-free and marker-based integration strategies when dealing with modifications that impair growth [13].

Troubleshooting:

- Persistent NHEJ: Confirm the genotype of the KU70-deleted strain. Consider additional deletion of KU80.

- Low Cell Viability Post-Transformation: Titrate the expression level of Cas9, as high constitutive expression can be toxic. Use an inducible promoter if available.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

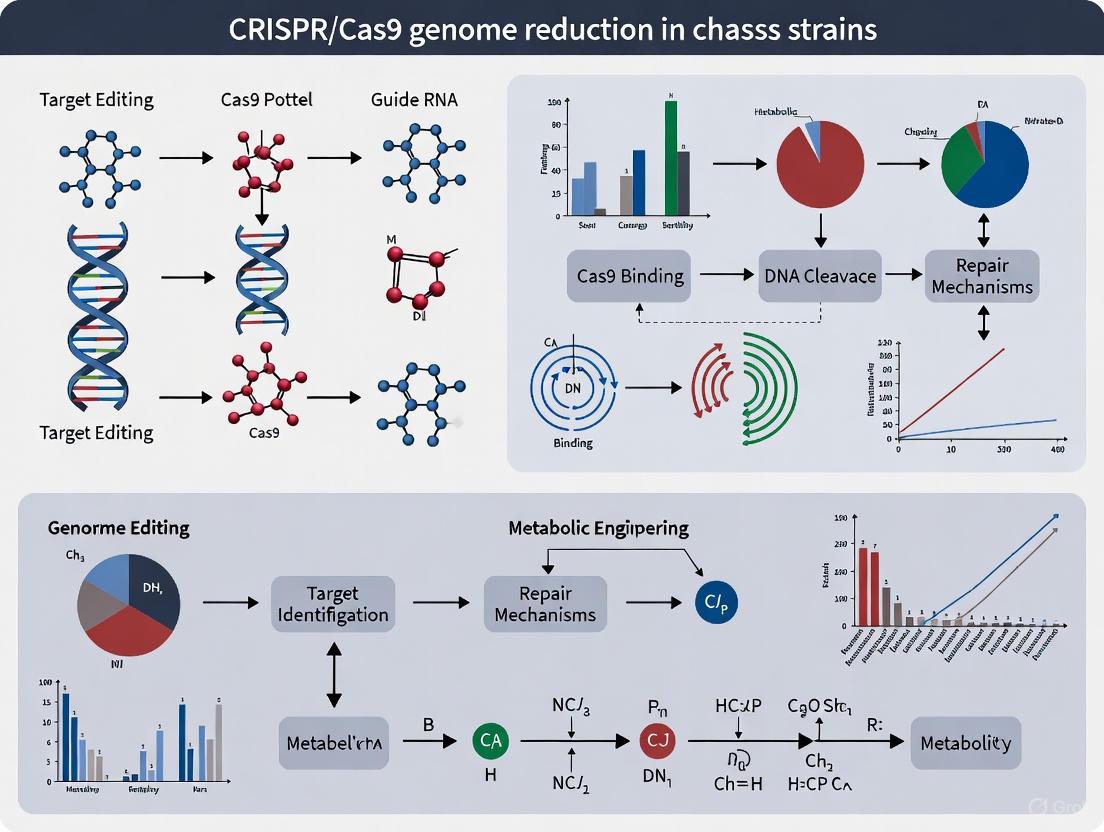

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for a genome reduction and metabolic engineering project using a CRISPR/Cas9 toolkit, highlighting the streamlined, modular process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs essential reagents and tools for implementing the described CRISPR/Cas9 workflows in chassis strain development.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR/Cas9 Strain Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants (e.g., iCas9, HypaCas9) | Engineered for reduced off-target effects and increased editing specificity and efficiency. | iCas9 (Cas9D147Y, P411T) boosted editing efficiency in Y. lipolytica [11]. HypaCas9 minimizes off-target cleavage [14]. |

| Modular DNA Assembly Toolkits (e.g., YaliCraft, MoClo) | Standardized genetic parts and protocols for rapid, one-pot Golden Gate assembly of multi-gene constructs. | YaliCraft toolkit enabled swift promoter library characterization and multi-locus integration in Y. lipolytica [13]. |

| NHEJ-Deficient Host Strains | Strains with deletions in genes like KU70 or KU80 to favor Homologous Recombination over error-prone NHEJ. | KU70 deletion in Y. lipolytica increased CRISPR-mediated integration efficiency to 92.5% [11]. |

| Specialized sgRNA Promoters | Promoters (e.g., SCR1-tRNA, U6) optimized for robust sgRNA expression in the target organism. | The SCR1-tRNA-gly promoter achieved 92.5% gene disruption efficiency in Y. lipolytica [11]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A delivery vehicle for in vivo CRISPR therapy; in microbiology, represents advanced delivery methods. | LNPs are used in clinical trials for efficient, systemic delivery of CRISPR components with potential for re-dosing [9]. |

The development of streamlined "chassis strains" is a cornerstone of modern synthetic biology, aiming to create minimal cellular factories optimized for industrial production. CRISPR/Cas9 technology has revolutionized this process, enabling precise genome reduction in microbial hosts. While E. coli and B. subtilis serve as fundamental bacterial models, yeast species—particularly Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica—offer eukaryotic complexity with industrial relevance. This Application Note provides a comparative analysis and detailed protocols for implementing CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering in these key yeast species, contextualized within genome reduction strategies for creating optimized chassis strains.

Comparative Analysis of Yeast Model Systems

The selection of an appropriate model organism is critical for successful genome reduction projects. S. cerevisiae provides a well-characterized platform with efficient homologous recombination, while Y. lipolytica offers unique metabolic capabilities for lipid and oleochemical production, despite its historically challenging genetics. The table below summarizes key characteristics relevant to CRISPR-based genome reduction.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Yeast Model Systems for CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Reduction

| Characteristic | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Yarrowia lipolytica |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Implementation | Established early (2013); highly optimized [15] | Developed later; requires specialized systems [16] [17] |

| DNA Repair Dominance | Highly efficient Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [15] | Dominant Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ); inefficient HDR [16] [17] |

| Editing Efficiency | High efficiency; enables multiplexing (up to 6 edits simultaneously) [15] | Variable; historically low success rates (≈50% in NHEJ-competent strains) [16] |

| Key Challenge | Managing multiple edits in polyploid strains [15] | Overcoming inefficient HDR without creating unfit NHEJ-deficient strains [16] |

| Key Innovation | CRISPRi/a for transcriptional control without mutagenesis [18] | Advanced tRNA-sgRNA fusions to boost editing efficiency [16] |

| Industrial Relevance | Classic biotechnology host (bioethanol, heterologous proteins) | Oleochemicals, organic acids, lipid-based biofuels [16] [17] |

Advanced CRISPR/Cas9 Methodologies

Protocol: High-Efficiency Editing in Yarrowia lipolytica Using Direct tRNA-sgRNA Fusions

The recalcitrance of Y. lipolytica to genetic manipulation, primarily due to its inefficient HDR, has been a significant bottleneck. The following protocol, adapted from Abdel-Mawgoud et al. (2020), details a method to achieve editing efficiencies close to 100% using optimized direct tRNA-sgRNA fusions, even in NHEJ-competent strains [16].

Principle: Conventional tRNA-sgRNA fusions contain an intergenic sequence that can form secondary structures, impairing sgRNA function. Direct fusions eliminate this sequence, leading to more efficient Cas9-guided editing [16].

Materials:

- Strain: Y. lipolytica Po1f (or other wild-type strain of interest) [16]

- CRISPR Plasmid: System expressing Cas9 and the direct tRNA-sgRNA fusion (e.g., pCRISPRyl derivatives) [17]

- Donor DNA: Repair template with 50-bp homology arms for HDR [16]

- Media: YPD (rich medium) and appropriate selection media (e.g., YNBD minimal medium) [17]

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design and Vector Construction:

- Design a 20-nucleotide guide sequence specific to your target locus using a design tool (see Reagent Toolkit).

- Clone the sgRNA sequence into a dedicated Y. lipolytica CRISPR vector (e.g., the Golden Gate-compatible vectors from [17]) that utilizes a direct tRNA-sgRNA fusion expression system. This system lacks the problematic 9-nucleotide intergenic sequence found in earlier designs [16].

Donor Template Design:

- For gene knock-in or precise edits, design a single-stranded or double-stranded donor DNA template.

- Critical Step: Flank the desired edit with homology arms of 50 base pairs in length. This relatively short length is sufficient when using the high-efficiency direct tRNA-sgRNA system and simplifies template synthesis [16].

Transformation:

- Co-transform the Y. lipolytica strain with the assembled CRISPR plasmid and the donor DNA fragment using a standard transformation protocol, such as lithium acetate transformation.

Selection and Screening:

- Plate transformed cells onto selection media appropriate for the CRISPR plasmid marker (e.g., media containing hygromycin or nourseothricin) [17].

- Incubate plates at 28°C for 2-3 days until colonies form.

- Screen individual colonies via colony PCR and subsequent Sanger sequencing to identify successful editing events. The high efficiency of this protocol means a high proportion of screened colonies will contain the desired edit.

Troubleshooting Note: If editing efficiency remains low, verify the secondary structure prediction of the sgRNA and ensure the target locus is accessible, as chromatin structure can influence efficiency [16].

Protocol: Multiplexed Genome Reduction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

S. cerevisiae is exceptionally suited for introducing multiple genomic deletions in a single step due to its highly efficient HDR pathway. This protocol enables simultaneous genome reduction at multiple loci.

Principle: Expressing multiple sgRNAs from a single plasmid or a set of co-transformed plasmids, along with a Cas9 nuclease, introduces several double-strand breaks. The cell's own repair machinery, using provided donor templates, executes the deletions or integrations [15].

Procedure:

- Multiplex sgRNA Cassette Design:

- Design individual sgRNAs for each target genomic locus slated for deletion.

- Assemble a multiplexed sgRNA expression cassette where each sgRNA is expressed from its own Polymerase III promoter (e.g., SNR52) or as part of a tRNA-gRNA array [15].

Donor Template Design:

- For each target gene, design a linear donor DNA fragment containing a selectable/counter-selectable marker (e.g., URA3) flanked by 40-60 bp homology arms directed to the regions upstream and downstream of the deletion site.

- Alternative: To create marker-free deletions, design a donor template that is simply a synthetic DNA fragment where the gene to be deleted is replaced by a short scar sequence or loxP site.

Co-transformation:

- Co-transform a diploid or polyploid industrial strain of S. cerevisiae with: [15]

- The plasmid expressing Cas9 and the multiplexed sgRNA cassette.

- The pool of all linear donor DNA fragments.

- Co-transform a diploid or polyploid industrial strain of S. cerevisiae with: [15]

Selection and Validation:

- Plate cells on media that selects for the integrated marker(s).

- Screen resulting colonies by multiplex colony PCR to verify all intended deletions.

- For marker recycling, induce the Cre recombinase (if using loxP sites) or perform counter-selection (e.g., on 5-FOA for URA3).

Technical Consideration: There is a practical upper limit to simultaneous edits; efficiency decreases as more DSBs are introduced, with current methods reliably achieving up to six edits at once [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of CRISPR protocols relies on specialized reagents and computational tools.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Yeast CRISPR Genome Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Golden Gate Vectors [17] | Modular CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids for Y. lipolytica | Contains different dominant markers (hygromycin, nourseothricin) for editing wild-type strains. |

| tRNA-sgRNA Fusion System [16] | Enhances sgRNA expression and function | Critical for achieving high efficiency in Y. lipolytica; prefer "direct" fusions without intergenic sequences. |

| CHOPCHOP [15] | Web-based tool for gRNA design | Identifies specific target sites and minimizes off-target effects. Supports multiple yeast genomes. |

| CRISPy [15] | Web-based tool for gRNA design in yeast | Designed for S. cerevisiae; facilitates design for reference and CEN.PK strains. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [9] | Non-viral delivery of CRISPR components | Used for in vivo delivery in therapeutics; a promising vector for future microbial delivery. |

| dCas9 Effectors (CRISPRi/a) [18] | Transcriptional repression/activation | Enables functional genomics and tuning gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. |

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow and experimental steps for a genome reduction project in yeasts, integrating the protocols and tools described above.

CRISPR/Cas9 has fundamentally transformed the engineering of yeast chassis strains, moving from single-gene edits to systematic genome reduction. While S. cerevisiae offers a streamlined path for multiplexed genome reduction, advanced tools like direct tRNA-sgRNA fusions have made the industrially promising Y. lipolytica a tractable and powerful host.

Future developments will likely focus on integrating machine learning and AI to design novel CRISPR effectors and predict optimal sgRNA targets, as demonstrated by the creation of AI-designed editors like OpenCRISPR-1 [6]. Furthermore, the move toward more sophisticated, high-content screening methods, including single-cell RNA sequencing, will provide deeper insights into the phenotypic consequences of genome reduction, enabling the rational design of next-generation microbial cell factories [19]. The continued refinement of non-viral delivery systems, such as lipid nanoparticles, may also open new avenues for CRISPR delivery in less tractable microbial systems [9] [20].

Genome reduction is a strategic approach in synthetic biology to construct streamlined microbial "chassis strains" for more efficient and predictable bioproduction. This process involves the systematic removal of genomic elements that are non-essential for a specific application, thereby reducing metabolic burden, eliminating unproductive pathways, and enhancing genetic stability. Within the context of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering, three key classes of genomic targets emerge as primary candidates for deletion: prophages, transposons, and non-essential metabolic genes.

Prophages, integrated bacteriophage genomes, can occupy significant genomic space and pose a threat to strain stability through spontaneous induction of the lytic cycle. Transposons, or "jumping genes," can cause insertional mutagenesis and genomic rearrangements, leading to unpredictable phenotypic variation. Non-essential metabolic genes encode functions redundant or unnecessary for the desired industrial application, and their deletion can channel cellular resources toward product formation. The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized the precision and efficiency with which these targets can be identified and removed, enabling the creation of minimal genomes tailored for specific biotechnological functions [1].

Target I: Prophages

Significance and Identification

Prophages are integrated viral genomes that reside within bacterial chromosomes. While they can sometimes confer beneficial traits to their host, their presence in industrial chassis strains poses significant risks, including:

- Genomic Instability: Spontaneous induction of the lytic cycle can lead to host cell lysis, compromising fermentation batches [21].

- Metabolic Burden: Maintenance and potential expression of prophage genes consume cellular resources that could otherwise be directed toward bioproduction [21].

- CRISPR Interference: Some prophages encode Anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins that can inhibit the CRISPR-Cas machinery, thereby disrupting subsequent genome engineering efforts [22] [21].

The co-evolution between bacteria and prophages is evident in the presence of CRISPR spacers within the host that target the very prophage integrated in its genome, a phenomenon known as "self-targeting." This indicates a history of immune response against the prophage and serves as a bioinformatic signature for identifying problematic prophages [22].

Table 1: Bioinformatic Tools for Prophage and CRISPR System Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Output | Application in Genome Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prophage Hunter [21] | Identifies prophage regions within bacterial genomes | Prophage sequences with a prediction score | Initial screening for potential prophage targets for deletion |

| CRISPR-Cas++ [21] | Detects and classifies CRISPR-Cas systems | Cas gene content and CRISPR subtype | Identifies self-targeting spacers and functional CRISPR systems |

| Mince [21] | Locates CRISPR arrays in genome assemblies | Spacer and repeat sequences | Reveals history of phage infection and self-targeting events |

Experimental Protocol for Prophage Deletion

Objective: To precisely remove a defined prophage region from the bacterial chromosome using CRISPR-Cas9 counterselection.

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Wild-type chassis strain harboring the target prophage.

- Plasmids: pCas9 (expresses Cas9 nuclease and λ-Red recombinase proteins), pTargetF (expresses sgRNA and contains an editing template) [23].

- Oligonucleotides: sgRNA oligonucleotides targeting the prophage sequence, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) homology templates for repair.

- Media: LB Lennox medium, antibiotics as required for plasmid maintenance.

Method:

- sgRNA Design and Cloning:

- Design two sgRNAs that target sequences near the boundaries of the prophage to be deleted. Ensure the target sites are unique in the genome to avoid off-target effects.

- Clone the sgRNA expression cassettes into the pTargetF plasmid.

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Template Design:

- Synthesize an HDR template (ssDNA or dsDNA) that contains ~500 bp homology arms flanking the entire prophage region. The sequence between the arms should be designed to either simply delete the prophage or replace it with a neutral sequence or selectable marker.

Transformation and Editing:

- Introduce the pCas9 plasmid into the target strain and culture at 30°C.

- Make the strain chemically competent and co-transform with the pTargetF-sgRNA plasmid and the HDR template.

- Incubate the recovery culture at 30°C for positive selection of transformants.

Counterselection and Curing:

- Plate transformations on media containing the appropriate antibiotic to select for cells that have incorporated the HDR template. The functional Cas9 will kill cells that retain the original prophage sequence (counterselection).

- To cure the pCas9 and pTargetF plasmids, induce the temperature-sensitive origin of replication by shifting the culture to 42°C and streak for single colonies without antibiotic pressure.

Validation:

- Screen colonies by colony PCR using primers that bind outside the deleted prophage region. Successful deletion will result in a smaller PCR product compared to the wild-type strain.

- Validate by Sanger sequencing of the edited locus.

Figure 1: Workflow for CRISPR-Cas9 mediated prophage deletion. The process involves target identification, tool design, transformation, and validation to generate a prophage-free strain.

Target II: Transposons

Significance and Harnessing CRISPR-Associated Transposases

Transposons are mobile genetic elements that can move within the genome, potentially disrupting functional genes and causing genetic instability. However, their inherent ability to insert DNA has been repurposed for genome engineering. CRISPR-associated transposases (CASTs) represent a powerful fusion of CRISPR-guided targeting and transposase-mediated integration, enabling highly efficient, targeted DNA insertion without requiring double-strand breaks or host recombination machinery [24] [25].

CAST systems, such as the Type I-F system from Vibrio cholerae (VcCAST), are particularly valuable for genome reduction as they can be programmed to disrupt or tag undesirable genes, such as those within transposons, on a large scale [24] [25]. Key features include:

- Programmable Integration: A CRISPR RNA (crRNA) guide directs the transposase complex to a specific genomic target site adjacent to a simple Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM; e.g., 5'-CN-3' for VcCAST) [24] [26].

- Large Payload Capacity: CASTs can integrate DNA payloads ranging from less than 1 kb to over 10 kb, making them suitable for inserting markers or entire functional cassettes [24].

- High Fidelity: Type I-F CAST systems exhibit remarkable specificity, with many showing >95% on-target accuracy, minimizing unintended off-target integrations [24].

Table 2: Features of Representative CRISPR-Associated Transposon Systems

| System Name | Type | Key Components | PAM Requirement | Integration Product | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VcCAST (Tn6677) [24] | I-F | TniQ-Cascade, TnsA, TnsB, TnsC | 5'-CN-3' | Simple Insertion (Cut-and-Paste) | High specificity (>95% on-target); Target immunity |

| ShCAST [25] | V-K | Cas12k, TnsB, TnsC | 5'-TN-3'? | Cointegrate (Replicative) | Single effector protein (Cas12k) |

Experimental Protocol for CAST-Mediated Gene Disruption

Objective: To use a CAST system to disrupt a target transposon or other gene by inserting a marker gene or a cassette that interrupts its coding sequence.

Materials:

- Plasmids: A three-plasmid system for VcCAST:

- pDonor: Contains the mini-transposon (mini-Tn) payload flanked by Tn7-derived left (L) and right (R) ends.

- pQCascade: Expresses the TniQ-Cascade DNA targeting complex (TniQ, Cas8, Cas7, Cas6) and a user-defined crRNA.

- pTnsABC: Expresses the heteromeric transposase (TnsA, TnsB, TnsC) [24].

- Bacterial Strain: Target chassis strain.

- Media: LB medium with appropriate antibiotics.

Method:

- crRNA and Donor Design:

- Design a crRNA with a 32-nt guide sequence that binds a 32-bp DNA target site located ~50 bp upstream of the desired integration site within the target transposon. Ensure the target is flanked by the appropriate PAM (5'-CN-3' for VcCAST).

- Clone the desired payload (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene flanked by 5-bp target site duplications) into the mini-Tn region of the pDonor plasmid.

Transformation:

- Co-transform the target bacterial strain with the three VcCAST plasmids (pDonor, pQCascade, pTnsABC).

- Plate the transformation on selective media containing antibiotics for all three plasmids and incubate for 1-2 days.

Screening and Validation:

- Screen individual colonies for the desired integration event. The payload will be integrated ~50 bp downstream of the target site defined by the crRNA.

- Perform colony PCR using one primer binding within the inserted payload and another binding in the genomic region outside the homology arm to confirm the correct integration locus and orientation.

- Sequence the junction sites to verify precise integration.

Curing and Advanced Delivery:

- The CAST plasmids can be cured from the edited strain by growing without antibiotic selection.

- For more advanced applications, the entire CAST system can be delivered via engineered bacteriophages (e.g., phage λ) for in situ editing, which is particularly useful for manipulating strains in complex microbial communities [26].

Figure 2: Workflow for transposon disruption using CAST. The system is designed, delivered to the cell, and executes precise integration to inactivate the target element.

Target III: Non-Essential Metabolic Genes

Significance and Identification via In Silico Minimisation

The identification of non-essential metabolic genes is crucial for constructing efficient chassis strains. The goal is to eliminate genes that are redundant or divert metabolic flux away from the desired product, thereby enhancing the yield of target compounds like plant-derived terpenoids [27] [23]. In silico metabolic modelling provides a powerful computational approach to systematically predict which genes can be removed.

A key methodology involves using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). An algorithm is employed to iteratively remove genes encoding enzymes and transporters from the model, maximizing the number of deletions while constraining the predicted biomass formation rate to remain above a strict threshold (e.g., no less than 90% of the wild-type value) [28]. This process reveals:

- Minimal Metabolic Networks (MMNs): The sets of genes that are collectively sufficient to maintain near-wild-type growth under specified conditions [28].

- Network Efficiency Determinants (NEDs): A class of genes that, while not strictly "essential" in a single-gene knockout sense, are almost always retained in MMNs. Their removal significantly reduces the global efficiency of the metabolic network. In S. cerevisiae, for example, the "Magnificent Seven" NED genes (including TPS1, TPS2, and ADE3) are present in all MMNs [28].

Table 3: Analysis of Minimal Metabolic Networks (MMNs) in S. cerevisiae under Different Conditions [28]

| Growth Condition | Approx. Number of Genes in MMN | Key Observations | Implication for Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic (Rich Medium) | Lowest | Smaller network sufficient with abundant nutrients. | Ideal starting point for maximal reduction. |

| Anaerobic (All Media) | Lower than Aerobic | Fewer genes required without respiratory functions. | Anaerobic processes can use highly streamlined strains. |

| Minimal Medium | Highest | More biosynthetic genes must be retained. | Strains for minimal media require more genetic capacity. |

Experimental Protocol for Multiplexed Gene Deletion

Objective: To simultaneously delete multiple non-essential metabolic genes predicted by in silico MMN analysis using CRISPR-Cas9.

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Target chassis strain.

- Plasmids: pCas9 (or a Cas9 plasmid with λ-Red recombinase), pTargetF for sgRNA expression.

- Oligonucleotides: A pool of sgRNA oligonucleotides targeting the selected non-essential genes, and a corresponding pool of HDR templates (ssDNA) for each gene, containing homology arms and a deletion sequence.

Method:

- Target Selection:

- Use the MMN and NED analysis to select a set of non-essential genes for deletion. Prioritize genes that are consistently absent from MMNs and are known to compete with the desired metabolic pathway (e.g., genes involved in byproduct formation).

Multiplexed sgRNA and HDR Template Design:

- Design 1-2 sgRNAs for each target gene, ensuring high on-target efficiency and minimal off-target effects.

- For each target gene, design an HDR template (ssDNA) that will introduce a precise deletion of the gene's coding sequence, optionally replacing it with a selectable marker if needed for screening. The markers should be different if multiple markers are used.

Multiplexed Transformation:

- Introduce the pCas9 plasmid into the target strain.

- Co-transform the strain with the pTargetF plasmid (encoding the pool of sgRNAs) and the pool of HDR templates.

- Plate the transformation on selective media if markers are used, or on non-selective media for markerless deletions.

Screening and Validation:

- Screen colonies by multiplex PCR using a set of primers designed to check for the absence of each target gene.

- For markerless deletions, high-throughput sequencing of the edited loci can be used to confirm the deletions.

- Characterize the edited strain by measuring growth rate and product yield (e.g., terpenoid production) to confirm the beneficial effect of the deletions [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Based Genome Reduction

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCas9 Plasmid [23] | Expresses Cas9 nuclease and λ-Red recombinase proteins. | Facilitates homologous recombination and counterselection in prokaryotes. | Temperature-sensitive origin for easy curing. |

| pTargetF Plasmid [23] | Expresses a user-defined sgRNA. | Targets Cas9 to a specific genomic locus for cleavage. | Compatible with pCas9 for two-plasmid editing system. |

| VcCAST 3-Plasmid System [24] | pDonor, pQCascade, pTnsABC for targeted transposition. | Programmable insertion of large DNA payloads without DSBs. | Enables kilobase-scale integrations with high fidelity. |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Template (ssDNA/dsDNA) | Provides donor DNA for precise editing via cellular repair. | Introduces specific deletions, insertions, or point mutations. | Can be designed for markerless edits. |

| Phage λ-DART [26] | Engineered phage delivering a CRISPR-transposase system. | In situ genome editing within complex microbial communities. | Bypasses the need for transformation. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) [28] | In silico model of an organism's metabolism. | Predicts essential and non-essential genes for deletion. | Guides rational design of minimal metabolic networks. |

The strategic deletion of prophages, transposons, and non-essential metabolic genes represents a cornerstone of constructing robust, efficient, and genetically stable chassis strains for industrial biotechnology. The protocols outlined herein—leveraging CRISPR-Cas9 for precise prophage excision, CRISPR-associated transposases for targeted gene disruption, and in silico modelling to guide metabolic streamlining—provide a comprehensive toolkit for achieving this goal. By applying these methods, researchers can systematically minimize bacterial genomes, reduce unproductive metabolic load, and enhance the flux toward desired products, thereby unlocking the full potential of microbial cell factories. The continued development and integration of these genome reduction technologies will be critical for advancing sustainable bioproduction.

CRISPR/Cas9 Toolkit: Practical Workflows for Efficient Genome Reduction

In the context of genome reduction for constructing minimal chassis strains, the precision of the CRISPR-Cas9 system is paramount. This precision is governed by three core components: the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) which directs the nuclease to a specific genomic locus, the Cas9 nuclease which creates the double-strand break, and the donor DNA template which facilitates the desired genetic alteration. Optimizing each of these components is critical for efficient and accurate genome engineering, enabling the systematic removal of non-essential genes to create streamlined microbial cell factories. The following sections provide detailed application notes and protocols for each component, complete with quantitative data and experimental workflows.

sgRNA Design and Synthesis

Application Notes

The design of the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) is the primary determinant of CRISPR-Cas9 efficiency and specificity. A well-designed sgRNA maximizes on-target activity while minimizing off-target effects, which is crucial when targeting multiple genomic loci for reduction.

Key design parameters include:

- On-target Efficiency: The sgRNA sequence must be chosen for high predicted activity. Computational tools use algorithms scoring GC content, position-specific nucleotides, and other features.

- Specificity: The sgRNA should have minimal similarity to other genomic sequences to prevent off-target cleavage. Guides with three or more mismatches in the seed region (PAM-proximal) are generally considered specific [29].

- Genomic Context: For genome reduction, target sites must be uniquely located within non-essential regions intended for deletion.

Synthetic sgRNA offers significant advantages over plasmid-based or in vitro-transcribed (IVT) gRNA, including faster experimental timelines, higher editing efficiency, reduced immunogenicity, and a DNA-free workflow which eliminates the risk of transgene integration [30]. Chemically synthesized sgRNAs can also include chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl and phosphorothioate at the 3' and 5' ends) that enhance stability and editing performance [30].

Protocol: sgRNA Design and Synthesis by Primer Extension

Adapted from Current Protocols [29]

This protocol describes a rapid method for sgRNA synthesis via primer extension and in vitro transcription, yielding sufficient material for multiple embryo manipulation experiments.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions)

- Oligonucleotides: Forward primer containing the T7 promoter sequence and the target-specific guide sequence, and a universal reverse primer.

- Enzymes: High-fidelity DNA polymerase, T7 RNA polymerase.

- NTPs: Solution of ATP, CTP, GTP, and UTP.

- Purification Kit: Solid-phase extraction kit for RNA cleanup (e.g., spin column-based).

- Equipment: Thermocycler, spectrophotometer or fluorometer for RNA quantitation, equipment for gel or capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer) for quality control.

Procedure

- sgRNA Design: a. Identify the target genomic sequence within the non-essential gene(s) slated for deletion. b. Select a 20-nucleotide guide sequence immediately adjacent to a 5'-NGG-3' Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM). c. Utilize design tools from [29] to assess on-target efficiency and potential off-target sites. Prefer guides with a Cutting Frequency Determination (CFD) score >66 or a high MIT specificity score. d. Incorporate the 20nt guide sequence into the forward primer design: 5'-TAATACGACTCACTATAGG + [20nt guide sequence] + GTTTAAGAGCTATGCTGGAA-3' (T7 promoter in bold, generic trailer sequence in italics).

Template Generation and IVT: a. Primer Extension: Perform a PCR reaction using the forward and reverse primers to generate a double-stranded DNA template incorporating the T7 promoter. b. In Vitro Transcription (IVT): Use the PCR product as a template in a transcription reaction with T7 RNA polymerase and NTPs. Incubate at 37°C for 2-4 hours. c. DNase Treatment: Degrade the DNA template with DNase I.

Purification and QC: a. Purify the synthesized sgRNA using a solid-phase extraction kit. b. Quantify the sgRNA concentration using a spectrophotometer. c. Assess integrity and purity by gel electrophoresis or capillary electrophoresis. A single, sharp band indicates high-quality sgRNA.

Quantitative Data: sgRNA Design Tools and Synthesis Options

Table 1: Commonly Used sgRNA Design and Off-Target Assessment Tools [29]

| Tool Name | URL | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| CHOPCHOP | https://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/ | sgRNA design and efficiency scoring |

| CRISPOR | https://crispor.tefor.net/ | sgRNA design with comprehensive off-target analysis |

| Cas-Designer | https://www.rgenome.net/cas-designer/ | Visualizes potential off-target sites |

| Cas-OFFinder | https://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/ | Searches for potential off-target sites across a genome |

Table 2: Commercial sgRNA Synthesis Services and Specifications [30]

| Service Grade | Length | Purification | Price (2 nmol) | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EasyEdit | 97-103 nt | Desalt | $79 | Cost-effective; standard modifications; ideal for early R&D |

| SafeEdit | 97-103 nt | HPLC | $119 | >90% purity; reduced off-targets & cytotoxicity; ideal for primary/stem cells |

| cGMP/INDEdit | Varies | cGMP-compliant | Quote-based | Supports IND filing and clinical trials; comprehensive QA/QC |

Diagram 1: sgRNA design and synthesis workflow.

Cas9 Nuclease Variants and Delivery

Application Notes

The choice of Cas9 variant and its delivery method significantly impacts editing outcomes, including efficiency, precision, and off-target effects, which must be carefully controlled during large-scale genome reduction.

Cas9 Variants: While wild-type Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) is widely used, engineered high-fidelity variants like eSpCas9 and hfCas9 are preferred for genome reduction projects. These mutants reduce off-target effects by weakening Cas9's interaction with non-target DNA, thereby increasing specificity without compromising on-target activity [31]. Furthermore, the size of the nuclease is a critical consideration for viral delivery; SpCas9 (1368 aa) is often too large to package with other components into size-constrained vectors like AAVs. Smaller natural variants (e.g., SaCas9) or engineered compact nucleases (e.g., hfCas12Max at 1080 aa) can circumvent this limitation [31].

Cargo Format: Cas9 can be delivered as DNA (plasmid), mRNA, or pre-complexed as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP).

- Plasmid DNA: Prolonged expression increases the risk of off-target effects and immune responses [31].

- mRNA: Offers transient expression, reducing off-target risks compared to plasmids.

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex: The pre-formed complex of Cas9 protein and sgRNA is immediately active upon delivery. RNP delivery offers the highest precision, with rapid degradation minimizing off-target effects, and is highly effective in hard-to-transfect cells [31] [30].

Protocol: Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Delivery by Electroporation

Adapted from Current Protocols [29]

Electroporation of RNP complexes into zygotes or microbial chassis strains is a highly efficient method for achieving high rates of gene editing.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions)

- Cas9 Protein: Commercial, high-purity, NLS-tagged Cas9 protein.

- Synthetic sgRNA: Chemically synthesized, HPLC-purified sgRNA from Section 2.

- Electroporation Buffer: Optimized for your cell type (e.g., zygotes, bacteria).

- Donor Template: Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) for HDR (see Section 4).

- Equipment: Electroporator and appropriate cuvettes or electrode slides.

Procedure

- RNP Complex Formation: a. Combine synthetic sgRNA (at a final concentration of 20-50 µM) with Cas9 protein (at a molar ratio of 1.2:1 to 2:1 sgRNA:Cas9) in nuclease-free electroporation buffer. b. Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to allow RNP complex formation.

Sample Preparation: a. Harvest and wash the target cells (e.g., chassis strain cells or zygotes) in electroporation buffer. b. Resuspend the cell pellet in the RNP complex mixture. If performing HDR, include the ssODN donor template (0.5-5 µM) in the mixture.

Electroporation: a. Transfer the cell-RNP suspension to an electroporation cuvette. b. Apply the pre-optimized electrical pulse(s) for your specific cell type. c. Immediately after electroporation, add recovery medium and incubate the cells under standard growth conditions.

Analysis: Screen the resulting colonies or clones for the intended genetic deletion or modification.

Quantitative Data: Cas9 Cargo and Viral Delivery Vectors

Table 3: Comparison of CRISPR Cargo Formats [31] [30]

| Cargo Format | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA (Plasmid) | Simple to construct and produce | High off-target effects; prolonged activity; cytotoxicity; immunogenicity | Low-cost screening when precision is not critical |

| mRNA | Transient expression; lower off-target than DNA | Requires cellular translation; can trigger immune response | In vivo delivery via LNPs [9] |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Immediate activity; highest precision; low off-target; DNA-free | More expensive; requires delivery optimization (e.g., electroporation) | Hard-to-transfect cells; high-fidelity genome editing |

Table 4: Viral Vectors for In Vivo CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery [31]

| Viral Vector | Payload Capacity | Genomic Integration | Key Advantages | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | ~4.7 kb | No | Mild immune response; FDA-approved for some therapies | Severely size-limited; requires small Cas9 variants |

| Adenoviral Vector (AdV) | Up to ~36 kb | No | Large cargo capacity; infects dividing & non-dividing cells | Can trigger strong immune responses |

| Lentiviral Vector (LV) | ~8 kb | Yes | Stable long-term expression; infects dividing & non-dividing cells | Safety concerns due to random integration |

Donor Template Design and Delivery

Application Notes

For genome reduction via homology-directed repair (HDR), a donor template is required to rewrite the genomic sequence following a Cas9-induced double-strand break. In the context of creating chassis strains, this template is typically designed to introduce a precise deletion or to "scarlessly" remove a genetic element.

- Template Type: Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) are ideal for introducing small deletions or point mutations. For larger deletions, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) templates with long homology arms (>500 bp) are more effective.

- Homology Arm Length: For ssODNs, homology arms of 35-90 nucleotides on each side of the Cas9 cut site are typically sufficient for efficient HDR in microbial systems and zygotes [29]. The cut site should be centrally located within the ssODN.

- Modification Strategies: To prevent re-cleavage by Cas9 after successful HDR, the donor template should be designed to incorporate silent mutations (synonymous codons) within the PAM sequence or the seed region of the protospacer. This disrupts sgRNA binding and ensures stable editing.

Protocol: Design and Use of ssODN Donor Templates

Adapted from Current Protocols [29]

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions)

- Synthesized ssODN: Commercially ordered, ultrapure, and preferably HPLC-purified.

- Cells: Prepared cells competent for electroporation or other delivery methods.

- RNP Complex: Prepared as described in Section 3.2.

Procedure

- Donor Template Design: a. Identify the Cas9 cut site within the target locus. b. Define the desired sequence change (e.g., a precise deletion of a specific gene segment). c. Design an ssODN with: - A Left Homology Arm (e.g., 40-90 nt) identical to the sequence immediately 5' to the cut site. - The Desired Edited Sequence (e.g., the deleted sequence). - A Right Homology Arm (e.g., 40-90 nt) identical to the sequence immediately 3' to the cut site. d. Critical Step: Introduce silent mutations in the PAM or seed region of the protospacer within the donor sequence to prevent re-cleavage.

Co-delivery with RNP: a. Include the designed ssODN donor template (at a final concentration of 0.5-5 µM) in the electroporation mixture with the pre-formed RNP complexes (from Section 3.2). b. Perform electroporation and cell recovery as outlined previously.

Screening and Validation: a. Screen edited clones by PCR using primers flanking the target site. b. Confirm the precise edit by Sanger sequencing of the PCR amplicon.

Diagram 2: HDR mechanism for precise genome editing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Genome Editing [30] [29] [31]

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic sgRNA | Guides Cas9 to specific genomic target | 97-103 nt length; chemically synthesized with 2'-O-methyl/phosphorothioate modifications for stability [30] |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Executes double-strand DNA break | Available as wild-type (SpCas9) or high-fidelity (eSpCas9) protein for RNP or as mRNA [30] [29] |

| Electroporation System | Delivers RNP complexes into cells | e.g., Neon (Thermo Fisher) or NEPA 21; requires optimized voltage and pulse parameters [29] |

| ssODN Donor Template | Template for precise HDR-mediated editing | Ultrapure, HPLC-purified; 35-90 nt homology arms; incorporates PAM-disrupting mutations [29] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery vehicle for mRNA/sgRNA | Particularly efficient for liver-targeted delivery; enables re-dosing [31] [9] |

| AAV Vectors | In vivo delivery vehicle for CRISPR cargo | Limited payload capacity; requires use of small Cas9 variants (e.g., SaCas9) [31] |

The development of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) technology has revolutionized functional genomics and synthetic biology, enabling precise genetic modifications across diverse biological systems [32]. A critical application of this technology involves genome reduction of microbial chassis strains, aiming to streamline cellular machinery for optimized industrial production, including biopharmaceuticals and biofuels. The success of these genome editing initiatives depends fundamentally on the efficient delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 components into target cells [33] [32].

This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for three principal delivery methods—plasmid transformation, electroporation, and conjugation—within the specific context of microbial systems. We present structured quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental methodologies, and essential reagent solutions to support researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate delivery strategy for their chassis strain engineering projects.

Comparative Analysis of Delivery Methods

Selecting an optimal delivery method requires a balanced consideration of editing efficiency, practicality, and the specific requirements of the downstream application. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of plasmid, electroporation, and conjugation-based delivery for CRISPR/Cas9 components.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery Methods in Microbial Systems

| Delivery Method | Typical Cargo | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Reported Editing Efficiency | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid Transformation | DNA plasmid encoding Cas9 and gRNA [31] | Simplicity, low-cost manipulation, stable expression [32] | Cytotoxicity, prolonged Cas9 expression increasing off-target effects, potential for plasmid DNA integration [31] [34] | High mutation efficiency in chicory; however, 30% of lines showed unwanted plasmid integration [34] | High-throughput screening in tractable strains, applications requiring sustained editing |

| Electroporation | Plasmid DNA, Cas9 mRNA with gRNA, or preassembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) [31] [32] | High efficiency for RNP delivery, immediate RNP activity reduces off-targets, avoids foreign DNA integration [31] [33] | Can cause cellular stress and alter gene expression; requires optimization of parameters [33] [35] | Up to 95% in SaB-1 fish cells; ~30% in DLB-1 fish cells with RNP [33] | Delivery of RNP complexes for precise, DNA-free editing; recalcitrant strains |

| Conjugation | Plasmid DNA (via mobilizable vectors) | Bypasses host restriction barriers, does not require specialized equipment [36] | Lower control over copy number, can be time-consuming, requires a donor strain | Information not specified in search results | Strains resistant to other transformation methods, transferring large DNA constructs |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Plasmid Transformation via Chemical Method

This standard protocol is suitable for introducing CRISPR/Cas9 expression plasmids into laboratory strains of bacteria like E. coli.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Transformation Buffer: 100 mM CaCl₂, 15% Glycerol, pH 6.5 (sterile-filtered).

- LB Growth Medium: 1% Tryptone, 0.5% Yeast Extract, 1% NaCl.

- LB Agar Plates: LB Growth Medium supplemented with 1.5% Agar and the appropriate selective antibiotic.

- CRISPR/Cas9 Plasmid: Plasmid DNA encoding Cas9 nuclease and the target-specific guide RNA, purified from a Dam⁻/Dcm⁻ E. coli strain to avoid restriction by host systems [36].

Methodology:

- Inoculate a single colony of the recipient microbial strain into 5 mL of LB broth and incubate overnight at the optimal growth temperature with shaking.

- Sub-culture the overnight culture into 50 mL of fresh LB broth and grow until the mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.4-0.6).

- Chill the culture on ice for 15 minutes and pellet the cells by centrifugation (4,000 x g, 10 min, 4°C).

- Gently resuspend the cell pellet in 10 mL of ice-cold Transformation Buffer and incubate on ice for 30 minutes to make competent cells.

- Pellet the cells again (4,000 x g, 10 min, 4°C) and resuspend in 1 mL of ice-cold Transformation Buffer.

- Aliquot 100 µL of competent cells into a pre-chilled tube. Add 1-10 µL (containing ~10-100 ng) of the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid DNA. Mix gently by flicking the tube.

- Incubate the mixture on ice for 30 minutes.

- Apply a heat shock by placing the tube in a 42°C water bath for exactly 45-60 seconds, then immediately transfer it back to ice for 2 minutes.

- Add 900 µL of pre-warmed LB broth and incubate at the optimal growth temperature for 1 hour with shaking to allow for antibiotic resistance expression.

- Spread 100-200 µL of the transformation mixture onto selective LB agar plates and incubate overnight at the appropriate temperature.

Protocol: Electroporation for RNP Delivery

This protocol is optimized for delivering pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA RNP complexes into microbial cells, minimizing off-target effects and avoiding genomic integration of foreign DNA [34] [33].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Electroporation Buffer: 1 mM HEPES, 300 mM Sucrose, pH 7.2 (sterile-filtered). Low ionic strength is critical for effective electroporation.

- Cas9 RNP Complex: Pre-assembled by incubating 3 µM of high-fidelity Cas9 protein with 3.6 µM of synthetic, chemically modified sgRNA (Synthego) for 10 minutes at room temperature [33].

- Recovery Medium: Rich growth medium (e.g., LB, BHI) without antibiotics.

Methodology:

- Grow the microbial strain to the mid-log phase as described in Protocol 3.1.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (4,000 x g, 15 min, 4°C) and wash three times with an equal volume of ice-cold Electroporation Buffer to remove all salts and ions.

- Resuspend the final cell pellet in a small volume of Electroporation Buffer to create a concentrated cell suspension (e.g., 10¹⁰ cells/mL).

- Mix 50 µL of the cell suspension with 5 µL of the pre-assembled Cas9 RNP complex. Transfer the mixture to a pre-chilled 1-mm electroporation cuvette.

- Perform electroporation using optimized parameters. Example parameters for marine fish cell lines: 1700-1800 V, 20 ms pulse length, 2 pulses [33]. Parameters must be empirically determined for different microbial species.

- Immediately add 1 mL of pre-warmed Recovery Medium to the cuvette and gently resuspend the cells.

- Transfer the cell suspension to a culture tube and incubate for 1-2 hours at the optimal growth temperature to allow for recovery and genome editing.

- Plate the cells on non-selective solid medium for single-colony isolation. Screen colonies for desired edits via PCR and sequencing.

Protocol: Intergeneric Conjugation fromE. colito Lactic Acid Bacteria

This protocol is adapted for transferring CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids from a donor E. coli strain to recipient lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that are recalcitrant to standard transformation [36].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Donor Strain: E. coli S17-1 or similar, containing the mobilizable CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid and a chromosomal copy of the RP4 tra genes.

- Recipient Strain: The target LAB strain.

- Mating Medium: Suitable rich medium for the recipient LAB (e.g., MRS for Lactobacilli).

- Selection Plates: MRS agar plates containing antibiotics selective for the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid and an antibiotic to counterselect against the E. coli donor (e.g., vancomycin for Lactobacilli).

Methodology:

- Grow the donor E. coli strain overnight in LB with appropriate selection.

- Grow the recipient LAB strain overnight in MRS broth.

- Harvest 1 mL of each culture by centrifugation (5,000 x g, 5 min). Wash cell pellets twice with 1 mL of fresh, antibiotic-free MRS broth to remove any traces of antibiotics.

- Resuspend both pellets in 100 µL of MRS broth and mix them together thoroughly.

- Spot the entire cell mixture onto a sterile filter membrane (0.45 µm) placed on a pre-warmed MRS agar plate (without antibiotics).

- Incubate the plate for 6-24 hours at the recipient strain's optimal temperature to allow for conjugation.

- After incubation, transfer the filter membrane to a tube containing 1 mL of MRS broth and vortex vigorously to resuspend the cells.

- Plate appropriate dilutions of the cell suspension onto pre-warmed Selection Plates.

- Incubate the plates anaerobically at the recipient's optimal temperature for 1-3 days until transconjugant colonies appear.

- Purify and screen the transconjugant colonies for the presence of the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid and the resulting genome edit.

Visualization of Delivery Method Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision-making workflow for selecting the most appropriate delivery method based on key experimental goals and strain characteristics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of delivery methods relies on key reagents. The table below lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery in Microbes

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 RNP Complex [31] [33] | Pre-assembled complex of Cas9 protein and sgRNA for direct delivery. Offers immediate activity, high specificity, and reduced off-target effects. | Chemically modified sgRNAs (e.g., from Synthego) can enhance stability and editing efficiency [33]. |

| Chemically Competent Cells | Cells treated to permit plasmid DNA uptake via heat shock. | Preparation requires ice-cold buffers and strict aseptic technique. Commercial kits offer high efficiency. |

| Electroporator & Cuvettes | Apparatus for creating transient pores in cell membranes via electrical pulse for RNP/DNA entry. | Cuvette gap size (e.g., 1mm, 2mm) and parameters (voltage, pulse length) must be optimized for each cell type [33]. |

| Mobilizable Shuttle Vector [36] | Plasmid containing origins of replication for both E. coli and the target species, and an origin of transfer (oriT) for conjugation. | Allows for plasmid propagation in E. coli and subsequent transfer to the target microbe via conjugation. |

| Dam⁻/Dcm⁻ Methylation-Free E. coli [36] | A host strain for plasmid propagation that lacks Dam and Dcm methylases. | Prevents restriction of the plasmid DNA by the recipient microbe's restriction-modification systems, boosting transformation efficiency. |

| Cell Wall Weakening Agents (e.g., Glycine, Lysozyme) | Agents added during growth to weaken the peptidoglycan layer of Gram-positive bacteria. | Critical for achieving transformation in recalcitrant strains like many Lactic Acid Bacteria [36]. |

Multiplexed genome editing represents a powerful advancement in genetic engineering, enabling the simultaneous modification of multiple genomic loci within a single experiment. This capability is particularly valuable for genome reduction in chassis strains, where the goal is to streamline microbial genomes by removing non-essential regions to optimize metabolic pathways, enhance genetic stability, and improve bioproduction yields. The CRISPR-Cas system, with its programmable nature and simplicity, has emerged as the premier platform for multiplexed editing, overcoming limitations of earlier technologies like ZFNs and TALENs that required complex protein engineering for each target site [37] [38].

For researchers engineering chassis strains, multiplexed CRISPR editing allows for the one-step elimination of multiple genomic regions, including non-essential genes, redundant pathways, and problematic sequences that may compete for metabolic resources or cause genetic instability. This approach significantly accelerates the strain optimization process compared to sequential gene editing methods. The core principle involves the coordinated expression of multiple guide RNAs (gRNAs) that direct Cas nucleases to specific genomic targets, inducing double-strand breaks that are repaired through cellular mechanisms resulting in targeted deletions [39] [37].

Key Strategies for Multiplexed Genomic Deletions

Guide RNA Expression and Processing Systems

The efficiency of multiplexed editing critically depends on the strategy used for expressing and processing multiple gRNAs. Several optimized systems have been developed, each with distinct advantages for different applications.

Table 1: Comparison of gRNA Processing Strategies for Multiplexed Editing

| Strategy | Mechanism | Organisms Demonstrated | Efficiency Range | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tRNA-gRNA arrays | Endogenous tRNA-processing machinery (RNase P/Z) cleaves flanking tRNA sequences | Yeast, Plants, Bacteria | Dual-gene: 57.5-100% [40] [11] | Universal processing; compatible with Pol II/III promoters |

| Ribozyme-gRNA arrays | Self-cleaving hammerhead and HDV ribozymes flank each gRNA | Mammalian cells, Plants, Yeast | Not specified | No auxiliary proteins needed; precise cleavage |

| Cas12a crRNA arrays | Cas12a processes its own pre-crRNA via recognition of hairpin structures | Human cells, Plants, Yeast, Bacteria | Not specified | Built-in processing; compact crRNAs |

| Csy4-processing system | Csy4 endoribonuclease cleaves at specific 28-nt recognition sequences | Mammalian cells, Yeast, Bacteria | 12 sgRNAs processed [39] | High precision; minimal sequence requirements |

Among these systems, tRNA-gRNA arrays have demonstrated particularly high efficiency in yeast chassis strains. In Pichia pastoris, a tRNA-sgRNA-tRNA (tgt) array achieved a remarkable 92.5% single-gene disruption efficiency and 57.5% dual-gene disruption efficiency [11]. Similarly, in Yarrowia lipolytica, the same approach enabled efficient multiplexed editing critical for metabolic engineering [11].

Optimized CRISPR Systems for Enhanced Editing

Further enhancements to CRISPR systems have significantly improved multiplexed editing efficiency in chassis strains:

- Cas9 Engineered Variants: The iCas9 variant (Cas9D147Y, P411T) demonstrated enhanced efficiency for both gene disruption and genomic integration in Yarrowia lipolytica [11].