Transcription Factor Engineering for Enhanced Microbial Strain Tolerance: Strategies, Applications, and Future Directions

This comprehensive review explores transcription factor (TF) engineering as a powerful strategy to enhance microbial strain tolerance, a critical bottleneck in industrial biotechnology and bioprocessing.

Transcription Factor Engineering for Enhanced Microbial Strain Tolerance: Strategies, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores transcription factor (TF) engineering as a powerful strategy to enhance microbial strain tolerance, a critical bottleneck in industrial biotechnology and bioprocessing. We examine the foundational principles of TFs as master regulators of complex stress response networks and detail cutting-edge methodological approaches for their identification and engineering. The article synthesizes recent advances in troubleshooting tolerance mechanisms and optimizing TF performance, highlighting validated applications across diverse microbial hosts. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical applications and validation frameworks, this resource provides researchers and scientists with a strategic guide for developing robust industrial microbial cell factories, with significant implications for biofuel production, pharmaceutical development, and biochemical manufacturing.

Master Regulators of Stress Response: Foundational Principles of Transcription Factors in Microbial Tolerance

Transcription Factors as Central Hubs in Stress Regulatory Networks

Transcription Factors (TFs) function as master regulators within cellular stress regulatory networks, interpreting stress signals and orchestrating complex transcriptional reprogramming to enable organismal adaptation [1] [2]. In both plant and microbial systems, TFs including WRKY, HSF (Heat Shock Transcription Factor), and specialized secondary metabolism regulators form intricate hubs that coordinate responses to abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, and nutrient deprivation [2] [3] [4]. Recent advances in TF engineering, leveraging tools from synthetic biology and computational modeling, are now enabling researchers to rewire these native networks to enhance stress tolerance phenotypes in crops and industrial production strains [5] [1]. This Application Note details practical methodologies for the identification, engineering, and deployment of TFs to bolster stress resilience, providing standardized protocols for the research community.

Application Notes

Key Transcription Factor Families in Stress Regulation

Several conserved TF families have been identified as central mediators of stress responses across diverse biological systems. Understanding their distinct roles provides a foundation for targeted engineering approaches.

WRKY Transcription Factors: WRKY TFs are prevalent in higher plants and are designated as "central regulators" of the abiotic stress response [2]. They recognize and bind to W-box cis-elements (A/TAACCA; C/TAACG/TG) in the promoters of target genes. They modulate responses to drought, salinity, and cold by regulating downstream genes involved in osmotic balance, antioxidant defense, and sugar metabolism pathways [2]. For instance,

IgWRKY50andIgWRKY32from Iris germanica enhance drought resistance in transgenic Arabidopsis, whileGmWRKY17in soybean activates drought-responsive genes likeGmDREB1DandGmABA2[2].Heat Shock Transcription Factors (HSFs): HSFs are highly conserved eukaryotic TFs that drive thermal tolerance [4]. In diatoms like Phaeodactylum tricornutum, HSFs are the most abundant TF family, with 69 genes identified. Overexpression of

PtHSF2significantly enhances heat tolerance and is associated with increased cell size and the upregulation of protective genes likeLhcx2(light-harvesting complex protein) andPtCdc45-like(cell division cycle protein) [4].Secondary Metabolism Regulators: In fungi, cluster-specific TFs regulate the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, many of which have bioactive properties [6]. These TFs are often located within biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) and remain transcriptionally silent under standard conditions. Systematic overexpression of these TFs, as demonstrated in Aspergillus nidulans, can activate cryptic BGCs, leading to the production of novel metabolites with antibacterial, antifungal, and anticancer activities [6].

Lipid Metabolism Regulators: In microalgae, specific TFs control lipid accumulation, a key trait for biofuel production that is often enhanced under stress like nitrogen deprivation [7]. In Chlamydomonas pacifica, overexpression of TFs such as

CpaLRL1(Lipid Remodeling Regulator 1),CpaNRR1(Nitrogen Response Regulator 1), andCpaPSR1(Phosphorus Starvation Response 1) significantly increases triglyceride (TAG) accumulation, even under normal growth conditions forCpaPSR1[7].

Quantitative Outcomes of Transcription Factor Engineering

Engineering transcription factors through overexpression or genome editing has yielded measurable improvements in stress tolerance and production metrics. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Transcription Factor Engineering in Various Organisms

| Organism | Transcription Factor | Engineering Approach | Stress Condition | Key Phenotypic Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus nidulans | 51 SM TFs (e.g., DbaA) |

Systematic OE with strong inducible promoter | Standard/Induced | >50% of OE strains produced novel metabolites; DbaA-OE extract showed ~90% bacterial growth inhibition |

[6] |

| Chlamydomonas pacifica | CpaPSR1 |

Overexpression | Normal Media | 2.4-fold increase in triglycerides (TAGs) vs. wild-type | [7] |

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | PtHSF2 |

Overexpression | High Temperature (30°C) | Markedly enhanced thermal tolerance and increased cell size | [4] |

| Sorghum bicolor | SbWRKY30 |

Overexpression | Drought Stress | Direct activation of drought-response gene SbRD19, improving growth and survival |

[2] |

| Zea mays | ZmWRKY104 |

Overexpression | Salt Stress | Enhanced tolerance via positive regulation of ZmSOD4, reducing ROS accumulation |

[2] |

Advanced Tools for Predicting TF Function and Interaction

The integration of computational tools and multi-omics data is revolutionizing the prediction of condition-specific TF activity, accelerating the identification of engineering targets.

CTF-BIND Framework: This novel computational framework integrates Bayesian causal networks and Graph Transformer deep learning to model TF binding across diverse abiotic stress conditions in Arabidopsis [3]. Trained on ~23TB of multi-omics data (ChIP-seq, RNA-seq, PPI), it can identify condition-specific TF binding directly from RNA-seq data with ~93% accuracy, bypassing the need for costly ChIP-seq experiments [3]. The model is available as an open-access web server, enabling researchers to predict dynamic shifts in regulatory pathways under stress.

Genome-Wide In-Silico Analysis: A computational pipeline successfully identified endogenous TFs (

CpaLRL1,CpaNRR1,CpaCHT7,CpaPSR1) for enhancing lipid accumulation in the microalga Chlamydomonas pacifica, which were subsequently validated in vivo [7]. This demonstrates the power of bioinformatic prediction for guiding metabolic engineering.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Systematic Overexpression of Transcription Factors to Activate Cryptic Metabolic Pathways

This protocol, adapted from a high-throughput study in Aspergillus nidulans, details a strategy for activating silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) by overexpressing cluster-specific transcription factors [6].

Principle: Strong, inducible overexpression of pathway-specific TFs can overcome transcriptional silencing and trigger the production of secondary metabolites.

Applications: Discovery of novel bioactive compounds (antibacterial, antifungal, anticancer) and investigation of regulatory networks governing secondary metabolism.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for TF Overexpression

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Strong Inducible Promoter | Drives high-level, conditional expression of the target TF gene. | xylP promoter from Penicillium chrysogenum [6] |

| Expression Vector | Plasmid backbone for constructing the TF overexpression cassette. | Contains selectable marker and sequences for genomic integration. |

| Host Strain | The organism harboring the silent BGCs of interest. | Aspergillus nidulans, or other fungi/microalgae [6] [7] |

| Inducing Agent | Chemical that triggers the inducible promoter. | 1% Xylose (for xylP promoter) [6] |

| Liquid Culture Medium | Supports growth and metabolite production. | ANM medium or other defined media [6] |

| Analytical Equipment | For detecting and analyzing induced metabolites. | LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) |

Procedure

TF Selection and Construct Design:

- Select TF genes located within predicted BGCs using tools like SMURF or antiSMASH, or TFs known from literature to regulate secondary metabolism [6].

- Clone the coding sequence of the selected TF downstream of a strong, inducible promoter (e.g., the

xylPpromoter) in an expression vector designed for targeted genomic integration (e.g., at a neutral locus likeyA).

Strain Transformation:

- Introduce the constructed overexpression vector into the host strain using standard transformation protocols (e.g., PEG-mediated protoplast transformation for fungi).

- Select stable transformants on appropriate selective media and confirm integration via genomic PCR.

Induction and Culture:

- Inoculate transgenic and wild-type control strains into liquid culture medium and incubate with shaking (e.g., 48 hours at 37°C for A. nidulans).

- Add the inducing agent (e.g., 1% xylose) to the culture. Continue incubation for several days to allow for metabolite production (e.g., 3 additional days) [6].

- Monitor cultures for phenotypic changes, such as pigment production in the mycelium or culture broth.

Metabolite Extraction and Analysis:

- Separate the culture broth from the biomass by filtration or centrifugation.

- Extract metabolites from both the broth and the biomass using appropriate organic solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Analyze crude extracts using LC-MS to profile metabolites and identify novel compounds. Compare chromatograms to wild-type controls.

Bioactivity Screening:

- Screen crude extracts for desired bioactivities (e.g., antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis or Staphylococcus aureus, antifungal activity, or cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines) [6].

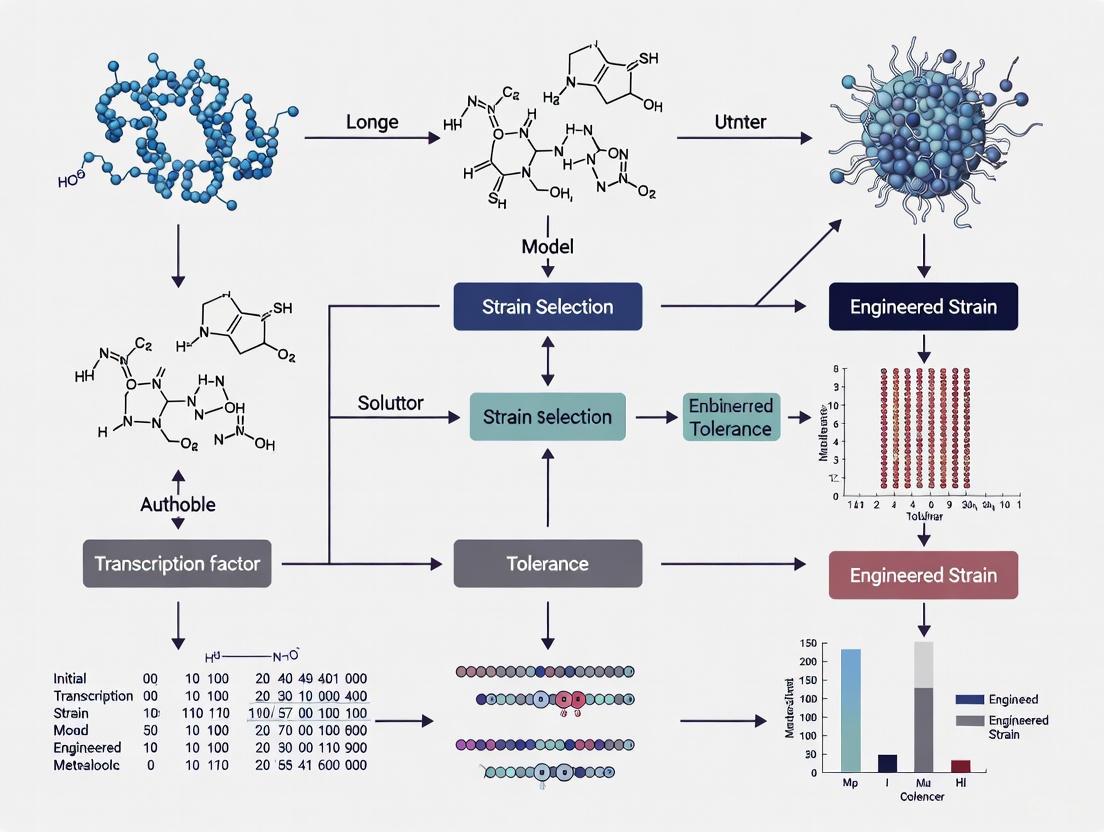

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this protocol:

Protocol: Computational Prediction of Condition-Specific TF Binding

This protocol outlines the use of the CTF-BIND deep learning framework to predict TF binding events under specific stress conditions using RNA-seq data as input [3].

Principle: A pre-trained Graph Transformer model uses RNA-seq data and protein-protein interaction networks to infer active TF-target gene relationships, eliminating the need for ChIP-seq.

Applications: Deciphering dynamic gene regulatory networks (GRNs) in response to abiotic stress; identifying key TFs and their targets for crop improvement strategies.

Materials and Software

- Input Data: RNA-seq data (from the condition of interest) and a reference genome for the organism (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana).

- Web Server Access: The CTF-BIND web server is freely available at:

https://hichicob.ihbt.res.in/ctfbind/[3]. - Computational Resources: Standard computer with internet access for using the web server.

Procedure

Data Preparation:

- Generate or obtain RNA-seq data from your organism under the specific stress condition(s) and appropriate control conditions.

- Process the raw sequencing data to obtain gene-level read counts or normalized expression values (e.g., TPM, FPKM).

Web Server Submission:

- Access the CTF-BIND web server.

- Upload the processed RNA-seq expression matrix as instructed.

- Select the TFs and stress conditions of interest from the available options (the server is pre-trained for 110 abiotic stress-related TFs in Arabidopsis).

Analysis Execution:

- Submit the job. The server will use its deep learning model to predict condition-specific TF-binding events and generate a causal regulatory network.

Result Interpretation:

- Download the results, which typically include:

- Lists of TFs predicted to be active under the queried condition.

- Their predicted target genes.

- Visualizations of the regulatory network.

- Use this output to prioritize TFs for experimental validation (e.g., overexpression) to confer stress tolerance.

- Download the results, which typically include:

The logical flow of this computational analysis is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A summary of key reagents and tools essential for transcription factor engineering projects is provided in the table below.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Transcription Factor Engineering

| Category | Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery Platforms | Cell-penetrating peptides, Extracellular vesicles, Lipid-based nanoparticles, Viral vectors | Overcoming challenges in cellular uptake and nuclear translocation for effective TF delivery [5] |

| Engineering Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing | For precise knockout or knock-in of TF genes or their regulatory elements (e.g., uORFs, miRNA sites) [1] |

| Expression Systems | Strong Inducible Promoters (e.g., xylP, alcA) |

To drive controlled, high-level expression of target TFs, crucial for activating silent gene clusters [6] |

| Computational Resources | CTF-BIND Web Server, SMURF, AntiSMASH | Predicting condition-specific TF binding; identifying secondary metabolite BGCs and their associated TFs [6] [3] |

| Analytical Methods | CUT&Tag, CUT&Tag-qPCR, RNA-seq, LC-MS | Validating direct TF targets (CUT&Tag); assessing transcriptomic changes (RNA-seq); profiling induced metabolites (LC-MS) [6] [4] |

Visualization of a Core Stress Response Signaling Pathway

The diagram below illustrates a generalized signaling pathway whereby a transcription factor, such as a WRKY or HSF, acts as a central hub to regulate a plant's or microbe's response to abiotic stress. This pathway integrates signal perception, TF activation, and the transcriptional regulation of diverse protective genes.

Transcription factors (TFs) are master regulators of gene expression that bind to specific cis-elements in the promoters of target genes, orchestrating complex transcriptional reprogramming in response to environmental stresses. In plants, several large TF families have been identified as crucial players in abiotic and biotic stress tolerance, including the NAC, AP2/ERF, bZIP, WRKY, and HSF families. These TFs function as molecular switches that integrate stress signals and activate downstream defense mechanisms, making them prime targets for genetic engineering strategies aimed at enhancing crop resilience. This article provides a comprehensive overview of these five major TF families, their structural characteristics, regulatory functions in stress responses, and practical applications in plant stress tolerance research.

Structural Features and Classification

Table 1: Characteristic features of major plant transcription factor families involved in stress tolerance

| TF Family | DNA-Binding Domain | Key Conserved Motifs | Recognized cis-Elements | Family Size in Plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAC | NAC domain (150-160 aa) at N-terminus | Subdomains A-E; A, C, D are conserved | NACRS, SNAC-specific motifs | 117 in Arabidopsis, 151 in rice [8] |

| AP2/ERF | AP2/ERF domain (60-70 aa) | YRG and RAYD elements | DRE/CRT (A/GCCGAC), GCC-box | Large family, plant-specific [9] [10] |

| bZIP | bZIP domain (60-80 aa) | Basic region + leucine zipper | ABRE (PyACGTGGC), G-box (CACGTG) | 78 in Arabidopsis, 89 in rice [11] [12] |

| WRKY | WRKY domain (~60 aa) | WRKYGQK motif + zinc finger | W-box (T/CTGACC/T) | One of the largest plant TF families [2] |

| HSF | DNA-binding domain (DBD) | Winged helix-turn-helix | HSE (nGAAn inverted repeats) | 27 in potato, 21 in Arabidopsis [13] |

The NAC family represents one of the largest plant-specific TF families, characterized by a conserved N-terminal NAC domain of approximately 150-160 amino acids that is further divided into five subdomains (A-E) [8]. The C-terminal region is highly divergent and functions as a transcriptional regulatory domain. The AP2/ERF family is defined by the AP2/ERF DNA-binding domain consisting of 60-70 amino acids that form a three-dimensional structure with three β-sheets and one α-helix [9]. This family is divided into five main groups: AP2, ERF, DREB, RAV, and Soloist [9] [10]. The bZIP family possesses a highly conserved bZIP domain comprising a basic region that facilitates DNA binding and nuclear localization, and a leucine zipper region that mediates dimerization [11]. WRKY TFs contain one or two WRKY domains characterized by the highly conserved WRKYGQK motif followed by a zinc finger structure [2]. HSF proteins feature a conserved DNA-binding domain that forms a winged helix-turn-helix structure, with class A Hsfs generally functioning as activators and class B as repressors [13].

Functional Roles in Stress Responses

Abiotic Stress Tolerance

Table 2: Documented roles of transcription factors in abiotic stress tolerance

| TF Family | Stress Response | Representative TFs | Mechanistic Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAC | Drought, salinity, cold, submergence | SNAC1, OsNAC6 | Stomatal closure, root development, antioxidant defense [8] |

| AP2/ERF | Drought, salinity, cold, heat, waterlogging | DREB2A, RAP2.12 | Osmolyte accumulation, ROS scavenging, hypoxia response [9] [10] |

| bZIP | Drought, cold, oxidative stress | OsbZIP62, BcbZIP72 | ABA signaling, CBF pathway activation, antioxidant gene regulation [11] [12] [14] |

| WRKY | Drought, salinity, heat, nutrient stress | IgWRKY50, GmWRKY17, ZmWRKY104 | ROS homeostasis, ion transport, sugar metabolism [2] |

| HSF | Heat stress | StHsfB5, HsfA3, HsfA4C | Chaperone induction, protein protection, thermomemory [13] |

NAC transcription factors function as critical regulators of drought, salinity, and cold stress responses. The SNAC subgroup, in particular, has been demonstrated to improve drought and salt tolerance when overexpressed in transgenic plants [8]. These TFs regulate various stress-adaptive mechanisms including stomatal closure, root system modification, and activation of antioxidant systems. AP2/ERF TFs, particularly the DREB subfamily, are central regulators of abiotic stress responses. DREB proteins bind to DRE/CRT elements in the promoters of stress-responsive genes, activating the expression of genes involved in osmoprotection, ROS detoxification, and cellular protection [9] [10]. The RAP2.12 TF mediates hypoxia responses during waterlogging stress [10].

bZIP TFs primarily function in ABA-dependent stress signaling pathways, with members such as OsbZIP62 playing crucial roles in drought and oxidative stress tolerance [12]. Recent research has identified BcbZIP72 as a positive regulator of cold tolerance through CBF-dependent pathways, directly activating BcCBF1 expression by binding to the G-box in its promoter [14]. WRKY TFs participate in multiple abiotic stress responses by regulating various physiological processes, including sugar metabolism, ROS scavenging, and ion homeostasis. For instance, ZmWRKY104 enhances salt tolerance by positively regulating ZmSOD4 and reducing ROS accumulation [2]. HSF transcription factors are master regulators of heat stress responses, controlling the expression of heat shock proteins (Hsps) that function as molecular chaperones to protect proteins from thermal denaturation. StHsfB5 promotes heat resistance by directly regulating the expression of sHsp17.6, sHsp21, sHsp22.7, and Hsp80 genes [13].

Biotic Stress Resistance

NAC transcription factors play crucial roles in plant immunity through multiple signaling pathways. They participate in both PTI and ETI - the two main layers of plant immune system [15]. NAC TFs regulate plant disease resistance by modulating hormone signaling pathways (SA, JA, ABA), reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and the hypersensitive response (HR) [15]. For example, rice OsNAC066, OsNAC096, OsNAC6, and OsNAC111 overexpression enhances resistance to blast disease [15]. AP2/ERF TFs, particularly those in the ERF subfamily, contribute to biotic stress resistance by binding to GCC-box elements in the promoters of pathogenesis-related (PR) genes. Similarly, certain bZIP and WRKY TFs have been implicated in defense responses against pathogens, though their roles in biotic stress are generally less prominent compared to their functions in abiotic stress adaptation.

Transcription Factor Engineering Strategies

Overexpression Approaches

Constitutive or stress-inducible overexpression of stress-responsive TFs represents a powerful strategy for enhancing crop tolerance. The coding sequence of the target TF is cloned under the control of a constitutive promoter (e.g., CaMV 35S) or stress-inducible promoter (e.g., RD29A) and transformed into plants via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or biolistic methods. For TFs lacking intrinsic transactivation activity, fusion with strong activation domains like VP64 may be necessary. For instance, OsbZIP62 fused to VP64 (OsbZIP62V) significantly enhanced drought and oxidative stress tolerance in transgenic rice, while the native protein showed limited activity [12].

Genome Editing Applications

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing enables precise modification of endogenous TF genes. This approach allows for the creation of superior alleles with enhanced transcriptional activity, altered expression patterns, or modified protein stability. The technology can also be used to generate loss-of-function mutants for functional characterization. For example, osbzip62 mutants generated via CRISPR/Cas9 showed reduced drought tolerance, confirming the gene's function in stress responses [12]. When designing editing strategies, focus on modifying regulatory domains rather than DNA-binding domains to preserve TF specificity while enhancing regulatory activity.

Experimental Protocols for TF Functional Characterization

Subcellular Localization Assay

Purpose: Determine the nuclear localization of TFs, a prerequisite for their function as transcription factors.

Procedure:

- Amplify the TF coding sequence without stop codon and clone into GFP fusion vector (e.g., pCAMBIA1302-GFP)

- Transform the construct into rice protoplasts or Arabidopsis leaf mesophyll protoplasts via PEG-mediated transfection

- Incubate transformed protoplasts for 16-24 hours at 22-25°C in darkness

- Observe GFP fluorescence using confocal microscopy with appropriate filters (excitation 488 nm, emission 505-530 nm)

- Counterstain nuclei with DAPI (excitation 358 nm, emission 461 nm) for confirmation

Expected Outcome: Nuclear localization of GFP fluorescence, as demonstrated for OsbZIP62-GFP which showed exclusive nuclear targeting [12].

Transcriptional Activation Assay

Purpose: Determine whether a TF functions as a transcriptional activator or repressor.

Yeast One-Hybrid Procedure:

- Clone full-length and truncated TF sequences into pGBKT7 or similar DNA-binding domain vector

- Transform into yeast strain (e.g., Y2HGold) and plate on SD/-Trp medium

- Transfer grown colonies to SD/-Trp/-His/-Ade medium supplemented with X-α-Gal for activity assay

- Incubate at 30°C for 3-5 days and monitor colony growth and blue color development

- Quantitative assessment can be performed using ONPG liquid assays

Expected Outcome: For activators like BcbZIP72, yeast growth on selective medium and β-galactosidase activity indicates transcriptional activation capability [14]. Note that some TFs like OsbZIP62 may require deletion analysis to identify activation domains, as the full-length protein might lack transactivation activity [12].

DNA-Binding Specificity Analysis

Purpose: Identify specific cis-elements recognized by the TF.

EMSA (Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay) Procedure:

- Express and purify recombinant TF protein from E. coli (GST or His-tagged)

- Label double-stranded oligonucleotides containing putative cis-elements with [γ-32P]ATP or biotin

- Incubate 10-20 fmol labeled probe with 100-500 ng purified protein in binding buffer (10 mM Tris, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 2.5% glycerol, 0.05% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA) with 1 μg poly(dI-dC) as nonspecific competitor

- Resolve protein-DNA complexes on 5-6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE at 100 V for 1-2 hours

- Transfer to nylon membrane (if using biotinylated probes) and detect using chemiluminescence

Expected Outcome: Shifted bands indicating protein-DNA complexes, as demonstrated for StHsfB5 which directly bound to promoters of sHsp genes [13]. For competition assays, include 100-200× molar excess of unlabeled probe.

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

The diagram illustrates the key regulatory pathways through which different TF families mediate stress responses. HSFs directly activate HSP expression under heat stress [13]. For cold stress, both ICE1-CBF and bZIP-CBF pathways converge on COR gene activation [14]. NAC and bZIP TFs respond to drought stress through both ABA-dependent and independent pathways to regulate downstream stress-responsive genes [8] [12]. These networks highlight the complexity and crosstalk between different TF families in coordinating plant stress responses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for transcription factor studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pCAMBIA1302-GFP, pGBKT7, pGEX-4T-1 | Subcellular localization, protein purification, Y2H | Gateway compatibility, various tags (GFP, GST, His) |

| Plant Transformation | Agrobacterium strains (GV3101, EHA105), CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Stable transformation, genome editing | Binary vectors, selectable markers, tissue-specific promoters |

| Yeast Systems | Y2HGold, Y187 yeast strains, SD dropout media | Protein-protein interaction, transactivation assays | Multiple reporter genes, low background |

| Antibodies | Anti-GFP, Anti-GST, Anti-His tag | Protein detection, western blot, ChIP | High specificity, various conjugates |

| Detection Kits | Chemiluminescent EMSA kit, ChIP assay kit | DNA-protein interaction, in vivo binding | High sensitivity, optimized protocols |

| Plant Growth Regulators | ABA, JA, SA, ethylene | Stress treatment, signaling studies | Hormone signaling pathway studies |

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Engineering transcription factors from the NAC, AP2/ERF, bZIP, WRKY, and HSF families represents a powerful strategy for developing stress-tolerant crops. The experimental protocols outlined provide robust methodologies for characterizing TF functions, from subcellular localization to DNA-binding specificity. Future research should focus on understanding the complex regulatory networks and crosstalk between different TF families, as well as developing tissue-specific or inducible expression systems for precise temporal and spatial control of TF activity. The integration of CRISPR-based genome editing with traditional overexpression approaches will enable more sophisticated engineering of TF-mediated stress tolerance pathways, contributing to the development of climate-resilient crops for sustainable agriculture.

Cells constantly encounter internal and external stressors that disrupt homeostasis, including proteotoxic stress, nutrient deprivation, oxidative damage, and osmotic imbalance. To survive these challenges, cells execute rapid and extensive transcriptional reprogramming, a process masterfully coordinated by a network of transcription factors (TFs). These TFs function as central processors of stress signaling, integrating diverse stress signals into coordinated genomic responses that reallocate cellular resources from growth to survival. The molecular mechanisms underlying this reprogramming involve sophisticated regulation of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) dynamics, chromatin organization, and enhancer activity across timescales ranging from minutes to hours [16].

Understanding these coordinated mechanisms provides a critical foundation for transcription factor engineering, a promising approach for enhancing cellular tolerance in industrial bioprocessing and therapeutic contexts. By harnessing the natural plasticity and regulatory capacity of stress-responsive TFs, researchers can pre-program robust adaptive responses that protect cells against diverse stressors, thereby improving productivity and resilience in manufacturing environments and addressing stress-related disease pathologies [17] [18] [19].

Molecular Mechanisms of Transcriptional Reprogramming

RNA Polymerase II Dynamics and Control Points

Stress-induced transcriptional reprogramming involves precise regulation of Pol II at multiple control points. Genome-wide studies using Precision Run-On sequencing (PRO-seq) have revealed that stress triggers rapid repression of thousands of genes while simultaneously activating hundreds of others. This reprogramming occurs through distinct mechanistic patterns:

- Promoter-Proximal Pausing: In mammalian cells, heat stress causes Pol II to accumulate at the promoter-proximal pause region of repressed genes, creating a poised state for potential recovery. In contrast, Drosophila shows decreased Pol II density across entire gene bodies [16].

- Rapid Induction Dynamics: At activated genes such as those encoding molecular chaperones, increased Pol II density along coding sequences can be detected within 2.5 minutes of stress exposure, demonstrating nearly instantaneous responsiveness [16].

- Temporal Expression Patterns: Different gene classes exhibit distinct kinetic profiles during stress response. Genes involved in translation machinery are repressed within 10 minutes, while RNA-processing complexes show more delayed repression. Some genes, like those encoding cytoskeletal components, display transient induction with expression peaks followed by decline below basal levels [16].

Table 1: Key Control Points in Stress-Responsive Transcription

| Regulatory Step | Mechanism | Impact on Gene Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter Opening | Nucleosome remodelling increases regulatory region accessibility | Enables TF binding and pre-initiation complex formation |

| Transcription Initiation | Pre-initiation complex (PIC) assembly at promoters | Determines transcription start site selection and frequency |

| Promoter-Proximal Pausing | P-TEFb kinase-mediated release of paused Pol II | Controls transition to productive elongation; rate-limiting step for many stress genes |

| Transcriptional Elongation | Pol II progression along DNA template with nascent RNA synthesis | Influences transcriptional output and co-transcriptional processing |

| Termination & Recycling | Transcription machinery recycling to transcription start sites | Maintains transcriptional capacity through chromatin looping |

Chromatin and Epigenetic Regulation

The chromatin landscape undergoes significant reorganization during stress responses, facilitating targeted gene expression:

- Pre-established TF Occupancy: ATF4 binds to hundreds of gene promoters even under non-stress conditions, particularly at genes involved in protein homeostasis. This pre-binding primes these genes for stronger and faster activation upon stress exposure, representing a "pre-wired" response system [20].

- Histone Modification Dynamics: Stress triggers changes in histone acetylation patterns, with increased H3K27 acetylation at activated genes during heat shock. However, ATF4-mediated gene activation during Integrated Stress Response (ISR) occurs independently of increased H3K27 acetylation, indicating alternative epigenetic mechanisms [16] [20].

- 3D Genome Architecture: Higher-order chromatin organization influences stress-responsive transcription. Transcriptional responses during ISR are linked to intrinsic chromatin properties, with CEBPγ preferentially targeting genomic regions exhibiting unique higher-order chromatin structures [20].

Enhancer Reprogramming

Beyond promoter regulation, enhancers undergo extensive reprogramming during stress responses. In heat-stressed human cells, thousands of enhancers show altered Pol II density, with some activated while others are repressed. These changes correlate with modifications to the local chromatin environment, including nucleosome dynamics and histone acetylation, demonstrating that stress responses involve comprehensive reshaping of both coding and regulatory elements [16].

Major Stress-Responsive Transcription Factor Families

Conserved TF Families Across Biological Systems

Multiple TF families have been identified as key regulators of stress responses across evolutionary lineages:

Table 2: Major Stress-Responsive Transcription Factor Families

| TF Family | Representative Members | Stress Signals | Regulatory Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| AP2/ERF | ERF5, ARF6, ABI3/VP1 | Drought, salinity, heat | Osmolyte production, antioxidant defense, growth regulation |

| bZIP | ATF4, ABF3, GCN4 | Nutrient deprivation, ER stress, oxidative stress | Amino acid metabolism, antioxidant response, autophagy regulation |

| NAC | NAC10, NAP | Drought, salt, cold | Senescence regulation, reactive oxygen species scavenging |

| HSF | HSF1, HSFA6a | Heat shock, proteotoxic stress | Chaperone induction, proteostasis maintenance |

| WRKY | WRKY30, WRKY53 | Pathogen response, drought | Defense gene activation, salicylic acid signaling |

| bHLH | PDR1, PDR3, ICE1 | Organic solvents, cold | Efflux pump regulation, membrane modification |

ATF4 as a Master Regulator of Integrated Stress Response

ATF4 exemplifies the sophisticated regulatory capabilities of stress-responsive TFs. As a central mediator of the Integrated Stress Response (ISR), ATF4 coordinates adaptation to diverse stressors through multiple mechanisms:

- Translational Control: ATF4 expression is primarily regulated at the translational level through phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) by stress-sensing kinases (PERK, GCN2, PKR, HRI). eIF2α phosphorylation reduces global protein synthesis while selectively promoting ATF4 translation [21] [20].

- Metabolic Reprogramming: ATF4 regulates key metabolic processes under nutrient stress, including serine synthesis through PHGDH, PSAT1, and PSPH enzymes; cystine uptake for glutathione synthesis; and mitochondrial function through asparagine-sensitive signaling [21].

- Heterodimerization Versatility: ATF4 functions as a hub TF by forming heterodimers with other bZIP proteins, particularly C/EBP family members. During ISR, transcriptional activation is linked to redistribution of CEBPγ from non-ATF4 sites to ATF4-bound regions, forming ATF4/CEBPγ heterodimers with distinct DNA-binding preferences [20].

Single-Cell Heterogeneity in Stress Responses

Single-cell RNA sequencing has revealed extensive heterogeneity in stress responses even within isogenic populations. During osmoadaptation in yeast, the osmoresponsive program exhibits highly variable expression across individual cells, organizing into combinatorial patterns that generate distinct cellular programs [22].

- Differential Gene Usage: At the peak of stress response, less than 25% of osmoresponsive genes are expressed in most cells (>75% of population), while the majority show expression in only a fraction of the population, creating cell-specific transcriptional "fingerprints" [22].

- Functional Specialization: Cluster analysis identifies distinct cellular subpopulations with specialized functional orientations. Some cells strongly induce protein folding chaperones (HSP82, SSA4), while others activate metabolic and oxidative stress genes, suggesting division of labor within the stressed population [22].

- Fitness Implications: Cells exhibiting basal expression of stress-responsive genes before stress exposure demonstrate hyper-responsiveness and increased stress resistance. This heterogeneity provides a bet-hedging strategy that maximizes population survival in fluctuating environments [22].

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing TF-Mediated Stress Responses

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Mapping of Transcription Factor Dynamics During Integrated Stress Response

Objective: To characterize temporal changes in ATF4 binding, chromatin organization, and transcriptional output during ISR activation.

Materials:

- C2C12 mouse myoblast cells or HeLa cells

- Thapsigargin (100 nM) or CCCP (ISR inducers)

- Formaldehyde for crosslinking

- Anti-ATF4 antibody (validated for ChIP)

- Proteinase K

- TRIzol reagent for RNA isolation

- Library preparation kits for sequencing

Methodology:

- ISR Induction and Time-Course Sampling:

- Treat cells with 100 nM Thapsigargin for 0, 2, 6, and 12 hours

- Collect samples at each time point for ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, Hi-C, and RNA-seq

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq):

- Crosslink cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature

- Quench crosslinking with 125 mM glycine for 5 min

- Sonicate chromatin to 200-500 bp fragments (Bioruptor Pico, 8 cycles of 30 sec ON/30 sec OFF)

- Immunoprecipitate with 5 μg anti-ATF4 antibody overnight at 4°C

- Reverse crosslinks, purify DNA, and prepare sequencing libraries

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin (ATAC-seq):

- Harvest 50,000 cells per condition

- Perform transposition reaction using Illumina Nextera DNA Library Preparation Kit (37°C for 30 min)

- Purify and amplify libraries for sequencing

RNA Sequencing:

- Extract total RNA using TRIzol reagent

- Prepare polyA-selected RNA libraries (Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA kit)

- Sequence on Illumina platform (minimum 30 million reads per sample)

Data Analysis:

- Map sequencing reads to reference genome (STAR for RNA-seq, Bowtie2 for ChIP-seq)

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DESeq2, log2FC >1, padj <0.05)

- Call ATF4 binding peaks (MACS2)

- Integrate multi-omics data to correlate ATF4 binding with transcriptional changes and chromatin accessibility

Applications: This protocol enables comprehensive characterization of ISR dynamics, revealing pre-established ATF4 occupancy that primes genes for rapid activation and identifying chromatin features that determine transcriptional responses [20].

Protocol 2: Engineering Transcription Factors for Improved Alkane Tolerance in Yeast

Objective: To enhance microbial tolerance to biofuel alkanes through engineering of PDR1 and PDR3 transcription factors.

Materials:

- S. cerevisiae BY4741 pdr1Δ pdr3Δ strain (BYL13)

- pESC-Ura expression vector

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit

- n-decane (C10) and n-undecane (C11)

- Galactose (inducer)

- Antibodies for Western blot (anti-Pdr1p, anti-Pdr3p)

- ROS detection kit (DCFH-DA)

- Membrane integrity dyes (propidium iodide)

Methodology:

- Transcription Factor Engineering:

- Introduce point mutations F815S and R821S in PDR1, and Y276H in PDR3 using site-directed mutagenesis

- Clone wild-type and mutated TF genes into pESC-Ura vector under GAL10 promoter

Strain Development and Screening:

- Transform constructs into BYL13 strain

- Induce TF expression with 0.5 g/L galactose (reduces growth inhibition)

- Challenge strains with 1% C10 or 5% C11 alkanes

- Monitor growth (OD600) and viability over 24-48 hours

Tolerance Mechanism Analysis:

- Intracellular Alkane Measurement: Extract intracellular alkanes with hexane, analyze by GC-MS

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Quantification: Stain cells with DCFH-DA, measure fluorescence by flow cytometry

- Membrane Integrity Assessment: Stain with propidium iodide, quantify fluorescence

- Gene Expression Analysis: Perform qPCR on PDR-regulated genes (ABC transporters, membrane modifiers)

Alkane Transport Assays:

- Measure alkane import and export rates using radiolabeled [14C]-alkanes

- Calculate intracellular accumulation over time

Applications: This engineering approach significantly improved yeast tolerance to medium-chain alkanes, with Pdr1mt1 + Pdr3mt expression reducing intracellular C10 alkane by 67% and ROS by 53%, while Pdr3wt reduced intracellular C11 alkane by 72% and ROS by 21% [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Transcription Factor Stress Response Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| TF Antibodies | Anti-ATF4, Anti-HSF1, Anti-phospho-eIF2α | Immunodetection, chromatin immunoprecipitation, localization studies |

| Stress Inducers | Thapsigargin (ER stress), CCCP (oxidative stress), NaCl (osmotic stress), Heat shock | Controlled induction of specific stress pathways |

| Sequencing Kits | Illumina TruSeq (RNA-seq), Nextera (ATAC-seq), ChIP-seq library prep kits | Genome-wide mapping of transcriptional and epigenetic changes |

| Expression Vectors | pESC-Ura (yeast), pcDNA3.1 (mammalian), pET-based (bacterial) | Heterologous TF expression and engineering |

| Reporter Systems | Luciferase, GFP/YFP, LacZ | Real-time monitoring of TF activity and promoter responses |

| Cell Lines/Strains | C2C12, HeLa, S. cerevisiae BY4741, E. coli KO strains | Model systems for stress response studies |

| Chemical Inhibitors | ISRIB (ISR inhibitor), KNK437 (HSF1 inhibitor), kinase inhibitors | Pathway dissection and validation |

Visualization of Key Signaling Pathways

TF-Mediated Stress Response Signaling

Applications in Strain Tolerance Engineering

The mechanistic understanding of TF-mediated stress responses enables sophisticated engineering approaches for enhancing strain tolerance:

- Core Stress Response Activation: Engineering conserved TF networks (AP2/ERF-ERF, NAC, bZIP, HSF) that regulate both universal and stress-specific pathways provides broad-spectrum tolerance. In maize, 744 core stress-responsive genes identified across six abiotic stresses were enriched for these TF families, representing key targets for engineering resilient crops [23].

- TF-Based Biosensor Development: Engineering TFs to create metabolite-responsive biosensors enables high-throughput screening of tolerant variants. Modified LuxR variants detect butanoyl-homoserine lactone at concentrations as low as 10 nM, while engineered BmoR mutants achieve 0-100 mM detection ranges for isobutanol [18].

- Pleiotropic Engineering: Manipulating master regulators like Pdr1p and Pdr3p in yeast simultaneously upregulates efflux pumps, membrane modifiers, and antioxidant systems, providing multi-mechanism tolerance against biofuel alkanes without requiring pathway-specific engineering [17].

Concluding Perspectives

Transcription factors function as the central processing units of cellular stress responses, integrating diverse signals into coordinated transcriptional programs through sophisticated regulation of Pol II dynamics, chromatin organization, and enhancer activity. The emerging paradigm reveals that stress responses are partially "pre-wired" through pre-bound TFs at primed genes, with response specificity determined by combinatorial TF expression, heterodimerization partnerships, and intrinsic chromatin properties.

Future directions in transcription factor engineering will leverage these mechanistic insights to design synthetic regulatory circuits that pre-program robust stress tolerance. Key opportunities include engineering TF promiscuity to create novel stress response circuits, designing synthetic heterodimerization pairs to rewire gene regulation, and developing dynamic control systems that automatically activate protection mechanisms before stress-induced damage occurs. These advanced engineering approaches promise to transform industrial bioprocessing and therapeutic interventions by creating cells with precisely calibrated adaptive capabilities.

The Heat Shock Transcription Factor (HSF) family represents a cornerstone of the cellular defense system, acting as master regulators of gene expression in response to proteotoxic stress caused by elevated temperatures. These evolutionarily conserved DNA-binding proteins activate a complex transcriptional program that restores cellular proteostasis by orchestrating the synthesis of molecular chaperones, facilitating protein refolding, and targeting irreparable aggregates for degradation [24] [25]. Beyond this canonical role, emerging evidence reveals that HSFs participate in diverse physiological processes, including development, metabolism, and comprehensive stress adaptation networks [25] [26].

The critical importance of HSF-mediated pathways extends across biological kingdoms, from safeguarding medicinal plants in vulnerable ecosystems to enhancing thermal resilience in marine diatoms fundamental to global carbon cycling [27] [4]. This universal conservation, coupled with functional diversification, makes the HSF family a prime target for transcription factor engineering aimed at improving stress tolerance in crops, protecting biodiversity, and understanding fundamental biological resilience mechanisms. This application note examines pivotal case studies that dissect the HSF family's role in thermal adaptation, providing detailed protocols and resources to empower research in this field.

Genome-wide studies across diverse species reveal significant variation in HSF family size and composition, reflecting evolutionary adaptations to specific environmental niches. The table below summarizes key findings from recent investigations.

Table 1: Genome-Wide Identification of HSF Gene Family Members Across Species

| Species | Total HSF Members | Class A | Class B | Class C | Notable Expansion Features | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Diatom) | 69 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Most abundant TF family; 44.2% of all TFs | [4] |

| Anisodus tanguticus (Medicinal Plant) | 20 (AntHSFs) | 3 subfamilies | 3 subfamilies | 3 subfamilies | Lineage-specific diversification | [27] |

| Ammopiptanthus mongolicus (Desert Shrub) | 24 (AmHSFs) | 5 primary classes | 5 primary classes | 5 primary classes | 13 phylogenetic subgroups | [28] |

| Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Shrub) | 25 (RtHSFs) | HSFA | HSFB | HSFC | Major expansion via gene duplication | [29] |

| Populus trichocarpa (Poplar) | 30 | A1-A9 | B1-B5 | C1-C2 | Segmental duplication as main driver | [26] |

The data demonstrates that the HSF family has undergone significant expansion in plants, particularly through duplication events, resulting in a complex repertoire that enables nuanced regulatory control over stress responses [26] [29]. The extraordinary abundance of HSFs in diatoms suggests a specialized adaptation to the highly variable marine environment, where they may function as central regulators of environmental sensing [4].

Molecular Mechanisms of HSF-Mediated Thermal Tolerance

The HSF Activation Cycle and Regulatory Complexity

HSF activation follows a multi-step cycle that transforms latent monomers into potent transcriptional activators. Under non-stress conditions, HSFs are maintained in an inactive monomeric state through intramolecular interactions and association with repressive complexes including heat shock proteins (HSPs) like HSP90 [24] [25]. Thermal stress causes widespread protein misfolding, sequestering HSP90 and relieving this repression. This allows HSF trimerization via their coiled-coil oligomerization domains (HR-A/B), leading to nuclear translocation, binding to target gene promoters at Heat Shock Elements (HSEs; consensus sequence nGAAnnTTCn), and recruitment of the transcriptional machinery [27] [24] [30].

Diagram: The HSF Activation Pathway and Cellular Stress Response

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) including phosphorylation, acetylation, and sumoylation create a sophisticated "HSF code" that fine-tunes this activation cycle, determines target gene specificity, and ultimately shapes the physiological outcome [24] [25]. For example, HSF1 phosphorylation at specific residues (e.g., Ser230) activates DNA binding, while acetylation of Lys80 dissociates HSF1 from DNA to attenuate the response [24].

Case Studies of Diverse Adaptive Mechanisms

Antioxidant System Coordination inAnisodus tanguticus

In the high-altitude medicinal plant Anisodus tanguticus, HSFs demonstrate a specialized role beyond chaperone regulation. Under heat treatment, specific AntHSF members (AntHSF7, AntHSF9) exhibit stage-specific expression patterns that closely coordinate with the activity of key antioxidant enzymes like Malondialdehyde (MDA), GSTT, GSTF, and Cu/ZnSOD [27]. This temporal regulation suggests that the AntHSF family critically manages the oxidative stress component of heat damage, directly linking proteostasis defense to redox homeostasis. Evolutionary analysis and sub-cellular localization further indicate that AntHSF7 and AntHSF9 are uniquely adapted for plateau-specific environmental challenges [27].

Cell Size Plasticity and Genome Replication in Marine Diatoms

Research on the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum reveals a novel HSF-mediated adaptive mechanism. Overexpression of PtHSF2 significantly enhanced survival at 30°C and induced a pronounced increase in cell size [4]. CUT&Tag analysis demonstrated that PtHSF2 directly targets and upregulates PtCdc45-like, a key DNA replication initiation factor. Functional studies confirmed that PtCdc45-like overexpression alone recapitulated the large-cell phenotype and improved thermal tolerance, indicating a direct regulatory axis where HSF activity modulates fundamental cell cycle processes to confer stress resistance [4].

Functional Divergence in theRhodomyrtus tomentosaHSFA2 Subfamily

In the thermotolerant shrub Rhodomyrtus tomentosa, functional divergence has occurred within the HSFA2 subfamily. While RtHSFA2a responds to drought, salt, and cold stresses, RtHSFA2b is specifically induced by heat stress [29]. Arabidopsis plants overexpressing RtHSFA2b outperformed RtHSFA2a-expressing lines under heat stress, and RtHSFA2b exhibited stronger transcription activity on specific Heat Shock Response (HSR) gene promoters. This subfunctionalization exemplifies how gene duplication and subsequent specialization can refine the stress response network, with RtHSFA2b playing a more vital role in thermotolerance [29].

Experimental Protocols for HSF Functional Analysis

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Identification and Phylogenetic Classification of HSF Genes

This foundational protocol is essential for characterizing the HSF family in any species of interest [27] [26] [29].

Materials:

- High-quality genome assembly and annotation file (FASTA, GFF/GTF)

- High-performance computing cluster or workstation

- HMMER software suite (v.3.3 or later)

- PFAM HSF DNA-binding domain profile (PF00447)

- Multiple sequence alignment software (e.g., MAFFT, MUSCLE)

- Phylogenetic tree construction software (e.g., IQ-TREE, RAxML)

Procedure:

- HMMER Search: Using the

hmmsearchcommand from the HMMER suite, search the entire proteome of the target species against the PF00447 Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile. Use an E-value cutoff of < 1 × 10⁻⁵ to identify candidate HSF proteins. - Domain Validation: Submit candidate protein sequences to the SMART and Pfam databases to confirm the presence of the characteristic HSF DNA-binding domain (DBD) and oligomerization domain (OD). Manually curate the final list to remove fragments and false positives.

- Sequence Alignment: Perform a multiple sequence alignment of the validated HSF protein sequences from the target species with reference HSF sequences from well-studied models (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa).

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Construct a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree (e.g., with 1000 bootstrap replicates) using the aligned sequences. Classify genes into subfamilies (HSFA, HSFB, HSFC) and subgroups (A1-A9, B1-B5, etc.) based on their clustering with known reference clades.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Analyze gene structure (exon-intron organization), conserved motifs (using MEME suite), and chromosomal location. Identify gene duplication events (tandem and segmental) by examining syntenic relationships within the genome and with related species.

Protocol 2: Expression Profiling Under Controlled Heat Stress

This protocol details the treatment and sampling methods for analyzing HSF transcript dynamics [27].

Materials:

- Uniform plant/microbial materials (e.g., seedlings, cell cultures)

- Precision growth chamber with temperature and light control

- Liquid nitrogen and -80°C freezer for sample preservation

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., TRIzol-based methods)

- Equipment for RNA-seq library prep and sequencing, or qRT-PCR instrumentation

Procedure:

- Plant Growth & Acclimation: Grow plants under controlled conditions (e.g., 16h light/8h dark, 22°C, 60% humidity) for a standardized period (e.g., 3 months for A. tanguticus).

- Heat Treatment Application: Subject biological replicates to a defined heat stress (e.g., 35°C for plants, 30°C for diatoms). Maintain control groups at the baseline growth temperature.

- Time-Course Sampling: Collect tissue samples at critical time points post-stress onset (e.g., 0 h, 4 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h). Immediately freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until RNA extraction.

- Transcriptional Analysis:

- For RNA-seq: Extract total RNA, check quality (RIN > 7.0), prepare libraries, and sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina). Map reads to the reference genome, calculate gene expression values (FPKM/TPM), and identify differentially expressed HSF genes.

- For qRT-PCR: Synthesize cDNA from DNase-treated RNA. Design gene-specific primers for each HSF gene and reference housekeeping genes. Perform qPCR and analyze data using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method to determine fold-change in expression.

Protocol 3: Functional Validation via Transgenesis

This protocol outlines the core steps for validating HSF function using genetic modification, a key approach demonstrated in diatoms and plants [4] [29].

Materials:

- Species-specific overexpression and/or RNA interference (RNAi) vector system

- Gateway or Golden Gate cloning reagents

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (for plants) or electroporator (for diatoms/algae)

- Selection agents (e.g., antibiotics, herbicides)

- Phenotyping equipment (e.g., growth chambers, imaging systems)

Procedure:

- Vector Construction:

- Overexpression: Clone the full-length coding sequence (CDS) of the target HSF gene into a binary expression vector downstream of a strong constitutive or inducible promoter.

- Knockdown/Knockout: For RNAi, clone an inverted repeat of a specific gene fragment into an RNAi vector. For CRISPR-Cas9, design and clone single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting the gene.

- Transformation: Introduce the constructed vector into the target organism.

- For plants: Use Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or biolistics.

- For diatoms: Use electroporation or microparticle bombardment.

- Regeneration and Selection: Regenerate transformed cells on selective media containing the appropriate agent to generate stable transgenic lines.

- Molecular Confirmation: Validate transgenic lines using genomic PCR to confirm transgene integration, qRT-PCR to measure transcript levels, and western blotting (if a specific antibody is available) to detect the protein.

- Phenotypic Assay: Subject T1 generation transgenic lines and wild-type controls to standardized heat stress assays. Evaluate key physiological parameters, including:

- Survival rate and chlorophyll content

- Photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm)

- Antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, CAT, POD)

- Marker gene expression (e.g., HSPs) via qRT-PCR

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for HSF Gene Functional Characterization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Resources for HSF Stress Research

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications & Examples | Primary Function in HSF Research |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody Reagents | Anti-HSF (species-specific); Anti-HSP70/HSP90; Anti-GFP for tagged proteins | Protein-level detection, quantification, and subcellular localization via western blot, ELISA, or immunostaining. |

| Enzyme Activity Assay Kits | SOD, CAT, POD, MDA, H₂O₂ detection kits (e.g., from Nanjing Ruiyuan Biotechnology) | Quantification of oxidative stress markers and antioxidant enzyme activity correlated with HSF activation. |

| Cloning & Expression Vectors | Gateway-compatible vectors; pCAMBIA series; species-specific overexpression/RNAi vectors | Genetic manipulation for functional studies (overexpression, knockdown, CRISPR-Cas9 knockout). |

| Live-Cell Reporting Systems | Hsp70-promoter::GFP/YFP reporter constructs (e.g., Hsp70-GFP fusion gene) | Real-time monitoring of HSF pathway activation and dynamics via fluorescence (flow cytometry, microscopy). |

| Controlled Environment Chambers | Precision growth chambers with programmable temperature, light, and humidity | Application of standardized, reproducible heat stress and other environmental challenges. |

The case studies presented herein underscore the crucial and versatile role of the HSF family in mediating thermal adaptation across diverse organisms. From coordinating antioxidant defenses in plateau plants to directly regulating cell cycle components in marine diatoms, HSFs employ a rich array of mechanisms that extend far beyond the induction of classic heat shock proteins. The intricate "HSF code" governed by post-translational modifications and isoform-specific interactions allows for precise, context-dependent regulation of transcriptional programs that are fundamental to cellular resilience [24] [25].

The experimental frameworks and resources provided offer a roadmap for deconstructing these complex networks in non-model organisms, enabling researchers to identify key HSF candidates for genetic engineering. Future efforts should prioritize CRISPR-based functional studies in planta, exploration of HSF interplay in combined stress scenarios, and the translation of these discoveries into sustainable conservation and crop improvement strategies [27] [31]. By leveraging the HSF family's inherent plasticity and central regulatory position, we can develop innovative solutions to enhance thermal tolerance in a warming world.

The Pleiotropic Drug Resistance (PDR) network in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a master regulatory system that controls cellular responses to a broad spectrum of environmental stresses and toxic compounds. This network, governed primarily by the zinc cluster transcription factors Pdr1p and its functional homolog Pdr3p, represents a paradigm for understanding multidrug resistance mechanisms with significant implications for both antifungal research and cancer biology [32] [33]. These transcription factors recognize specific DNA sequences called Pleiotropic Drug Response Elements (PDREs), with the canonical sequence 5'-TCCGCGGA-3', to activate approximately 50 target genes involved in cellular detoxification [32]. The PDR network is triggered by diverse stressors including mitochondrial damage, heat shock, membrane damage, translational stress, and exposure to cytotoxic chemicals [33]. Through their regulatory control over ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters and major facilitator superfamily transporters, Pdr1p and Pdr3p enhance cellular capacity to export toxic substances, thereby conferring resistance to multiple drugs simultaneously [32] [33]. This application note details experimental frameworks for investigating Pdr1p and Pdr3p, with direct relevance to transcription factor engineering for enhanced microbial strain tolerance in industrial biotechnology.

Quantitative Profiling of PDR Network Components

Key Regulatory Targets and Experimental Phenotypes

Systematic studies have identified numerous genes under Pdr1p/Pdr3p regulation, with distinct and overlapping functions within the PDR network. The table below summarizes quantitatively expressed targets and documented loss-of-function phenotypes.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined PDR Network Targets and Functional Phenotypes

| Gene Target | Encoded Protein Function | Regulating TF(s) | Documented Phenotype of Mutant |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDR5 | ABC transporter | Pdr1p, Pdr3p | Hypersensitivity to cycloheximide, oligomycin [32] |

| SNQ2 | ABC transporter | Pdr1p, Pdr3p, Yrr1p | Hypersensitivity to 4-nitroquinoline-N-oxide (4-NQO) [34] |

| YOR1 | ABC transporter | Pdr1p, Pdr3p, Yrr1p | Hypersensitivity to oligomycin [34] |

| PDR10 | ABC transporter | Pdr1p, Pdr3p | |

| PDR15 | ABC transporter | Pdr1p, Pdr3p | |

| FLR1 | Major Facilitator Superfamily permease | Pdr1p, Yrr1p | |

| YRR1 | Zn₂Cys₆ transcription factor | Pdr1p | Hypersensitivity to 4-NQO, oligomycin [34] |

Quantitative Analysis of Transporter Efficacy in Metabolic Engineering

The application of PDR engineering has demonstrated significant quantitative improvements in product secretion. Recent research on vitamin A production in engineered S. cerevisiae provides a clear example.

Table 2: Effect of PDR Component Overexpression on Vitamin A Production Titers

| Engineered PDR Component | Retinoid Product | Concentration (mg/L) | Secretion Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| None (Control) | Retinol/Retinal | Baseline | <95% |

| PDR3 | Retinol/Retinal | >400 mg/L | >95% [35] |

| PDR10 | Retinol/Retinal | >400 mg/L | >95% [35] |

| PDR3 + PDR10 | Retinal only | 638.12 mg/L | 98.7% [35] |

| SNQ2 | Retinol only | 430.14 mg/L | >93% [35] |

| PDR3 + PDR10 (with promoter balancing) | Retinol only | 549.79 mg/L | 94.5% [35] |

Experimental Protocols for PDR Network Analysis

Protocol 1: Genomic Occupancy Profiling Using CUT&RUN

Purpose: To identify genome-wide binding sites for Pdr1p and Pdr3p under basal and stress conditions with high resolution.

Principle: CUT&RUN (Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease) uses micrococcal nuclease tethered to specific antibodies to cleave and release target-bound DNA fragments, offering low background and high signal-to-noise ratio compared to ChIP-seq [33].

Procedure:

- Strain Development: Engineer yeast strains expressing epitope-tagged transcription factors (e.g., Pdr3p-3xMyc) in the desired genetic background (e.g., FY1679-28c).

- Nuclei Isolation: Grow yeast to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.6-0.8). Spheroplast cells using Zymolyase 100T and isolate nuclei.

- Chromatin Capture: Immobilize purified nuclei on Concanavalin A-coated magnetic beads.

- Antibody Binding: Incubate bead-bound nuclei with primary antibody (e.g., anti-c-Myc, 0.5 µg per sample) overnight at 4°C. Include control samples with non-specific IgG.

- pAG-MNase Binding: Wash beads and incubate with Protein A-MNase fusion protein (pAG-MNase) for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Chromatin Cleavage: Induce targeted chromatin cleavage by adding 100mM CaCl₂ and incubating on ice for 30 minutes.

- DNA Extraction: Stop reactions, release cleaved fragments, and extract DNA using phenol-chloroform with glycogen carrier.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries using kits such as NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina. Sequence and map reads to the reference genome to identify binding peaks [33].

Protocol 2: CRISPRi/a-Mediated TF Expression Tuning for Acetic Acid Tolerance

Purpose: To precisely modulate PDR1 or YAP1 expression levels using CRISPR interference/activation (CRISPRi/a) to investigate and enhance acetic acid tolerance.

Principle: A catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional repressor (Mxi1) or activator (VPR) domains is guided to promoter regions by specific sgRNAs to fine-tune transcription factor expression [36].

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design: Design 4-8 sgRNAs targeting regions within -400 bp to +1 of the transcription start site (TSS) of PDR1 or YAP1 using tools like CRISPR-ERA or CHOP CHOP.

- Vector Assembly: Clone sgRNA sequences into a pRS416-based vector containing TetR-dCas9-Mxi1 (for CRISPRi) or TetR-dCas9-VPR (for CRISPRa) and a URA3 selection marker.

- Yeast Transformation: Introduce assembled plasmids into the target S. cerevisiae strain (e.g., CEN.PK 113-5D) using standard lithium acetate transformation.

- Tolerance Screening: Inoculate transformants in appropriate selective medium and grow to mid-log phase. Spot serial dilutions (10-fold) onto solid YPD media containing acetic acid at inhibitory concentrations (e.g., 4-5 g/L). Incubate at 30°C for 3-5 days.

- Growth Quantification: For quantitative analysis, grow strains in liquid medium with acetic acid and monitor growth kinetics by measuring OD₆₀₀ every 2 hours for 24-48 hours. Calculate specific growth rates.

- Validation: Confirm changes in TF expression and downstream target gene activation via qRT-PCR [36].

Protocol 3: Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) for PDRE Binding

Purpose: To validate direct binding of Pdr1p or Pdr3p to candidate PDRE sequences in vitro.

Procedure:

- Probe Preparation: Amplify ~200 bp promoter regions containing putative PDREs from genomic DNA using high-fidelity polymerase. End-label purified PCR products with [γ-³²P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase.

- Protein Extraction: Express and purify DNA-binding domains of Pdr1p/Pdr3p from E. coli or prepare whole-cell extracts from yeast overexpressing the TFs.

- Binding Reaction: Incubate 1-10 fmol of labeled DNA probe with purified protein or cell extract in binding buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 5% glycerol) for 20-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Electrophoresis: Resolve protein-DNA complexes on a pre-run 4-6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5X TBE buffer at 100-150 V for 1-2 hours.

- Detection: Transfer gel to filter paper, dry, and visualize shifted bands using phosphorimaging or autoradiography.

- Specificity Controls: Include competitions with excess unlabeled wild-type (specific) or mutated (non-specific) PDRE oligonucleotides to confirm binding specificity [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PDR Network Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Epitope-Tagged TF Strains (e.g., Pdr3p-3xMyc) | Immunoprecipitation and visualization of endogenous protein | CUT&RUN, co-immunoprecipitation [33] |

| PDR-LacZ Reporter Plasmid | Measure transcriptional activation from a PDRE | Quantifying Pdr1p/Pdr3p activity under different conditions [32] |

| pCB-GAD Fusion Plasmid | Expressing DNA-binding domain fused to activation domain | Identifying direct targets via artificial transactivation [34] |

| CRISPRi/a System (dCas9-Mxi1/VPR) | Precise transcriptional repression or activation | Fine-tuning PDR1 expression for acetic acid tolerance [36] |

| PDR1/PDR3 Deletion Strains (ΔPDR1, ΔPDR3) | Loss-of-function studies | Identifying TF-specific regulons and phenotypes [32] [33] |

| Gain-of-Function Mutants (e.g., pdr1-3) | Hyperactive transcription phenotype | Studying PDR network overexpression effects [32] |

Regulatory Network and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: The Core PDR Regulatory Network and Key Engineering Strategies. This diagram illustrates the central role of Pdr1p and Pdr3p in transducing diverse stress signals into a multidrug resistance phenotype through regulation of effector genes. Dashed boxes categorize network components. Engineering strategies like CRISPRi (red 'i') and CRISPRa (green 'a') can modulate transcription factor activity to enhance desired traits like acetic acid tolerance [32] [36] [34].

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for PDR Transcription Factor Analysis and Engineering. This workflow outlines a multi-faceted approach to characterize transcription factor function, from initial genomic binding studies and expression analyses to the final engineering of strains with enhanced tolerance traits [33] [36] [37].

Engineering Strategies and Practical Applications: From TF Modification to Strain Improvement

High-Throughput Methods for Novel TF Identification and Characterization

Transcription factor (TF) engineering represents a powerful strategy for developing microbial and plant strains with enhanced tolerance to environmental stresses and industrial production conditions [38] [31]. The foundation of rational TF engineering relies on comprehensive characterization of TF-DNA binding properties, including specificity, affinity, and sequence requirements. High-throughput methodologies have dramatically accelerated our capacity to profile TFs, moving beyond traditional low-throughput approaches that were impractical for systematic analysis [39] [40]. These advanced methods enable researchers to obtain quantitative binding data for thousands of DNA sequences simultaneously, providing the rich datasets necessary to build predictive models of TF binding behavior and identify novel TFs with desirable properties for strain engineering [39] [41].

The transition to high-throughput analysis addresses critical limitations in traditional TF characterization. Conventional methods like electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) provide valuable data but are limited in throughput to approximately 10 binding sites, making comprehensive profiling impractical [40]. Similarly, Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) traditionally identified only consensus binding sites without detailed affinity information [40]. Modern high-throughput approaches overcome these constraints by leveraging microarray technology, next-generation sequencing, and microfluidic systems to generate extensive binding datasets that capture both strong and weak interactions across sequence space [39] [40].

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput TF Characterization Methods

| Method | Throughput (DNA Sequence Space) | Data Type | Key Measurements | Resolution | Materials Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Binding Microarray (PBM) | Up to 1 million sites [40] | Semi-quantitative [40] | Relative KD, PWM [40] | Nucleotide resolution feasible [40] | µg of protein [40] |

| HT-SELEX/Bind-n-Seq | >200,000 sites [40] | Semi-quantitative [40] | Relative KD, PWM [40] | Nucleotide resolution feasible [40] | mg of protein [40] |

| Mechanical Trapping (MITOMI) | 1,000 to 10,000 sites [40] | Quantitative [40] | Absolute KD, kon, koff [40] | Nucleotide resolution [40] | ng of protein [40] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Up to 100 sites [40] | Quantitative [40] | Absolute KD, kon, koff [40] | Few binding sites only [40] | µg of protein [40] |

| ChIP-seq | All genomic sites [40] | Qualitative [40] | In vivo binding sites [40] | 100-500 bp [40] | ng of DNA [40] |

Table 2: Data Type Classification for TF-DNA Interaction Methods

| Data Classification | Methods | Key Characteristics | Applications in TF Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Traditional SELEX, DNA footprinting, initial ChIP-chip [40] [41] | Identifies consensus sequences without affinity data [40] | Preliminary TF screening, consensus motif identification [41] |

| Semi-Quantitative | PBM, HT-SELEX, DIP-chip [40] | Provides relative affinity measurements [40] | Binding site characterization, specificity profiling [39] |

| Quantitative | MITOMI, SPR, EMSA, ITC, MST [40] [41] | Determines absolute binding constants (KD) [40] | Accurate affinity measurements, biophysical characterization [41] |

| Kinetic | SPR, MITOMI [40] | Measures binding rates (kon, koff) [40] | Understanding binding mechanics, residence times [40] |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protein Binding Microarray (PBM) Protocol

Principle: PBMs utilize high-density DNA microarrays to measure TF binding specificity across thousands to millions of potential DNA binding sites simultaneously [39] [40]. Double-stranded DNA probes are immobilized on glass slides, incubated with the TF of interest, and binding events are detected via fluorescently labeled antibodies [39].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Array Fabrication: Design and spot DNA oligonucleotides representing variant binding sites onto polyacrylamide-modified glass slides using appropriate surface chemistry (e.g., polyacrylamide/ester glass activation for 5'-amino-modified DNA) [39].

DNA Duplex Preparation: Prepare 34 bp oligonucleotides containing common sequences and binding site-specific regions. Anneal complementary oligonucleotides modified with 5' amino groups or biotin, then extend the complementary strand by polymerization [39].

Protein Binding Reaction: Incubate arrays with 80 μL of protein binding mixture containing:

- 6 mM HEPES (pH 7.8)

- 40 mM KCl

- 0.5 mM EDTA

- 0.5 mM EGTA

- 6% glycerol

- 0.25 μg/μl dIdC (non-specific competitor)

- 2% milk (blocking agent)

- Purified TF at 50-125 ng/μl concentration [39]

Detection and Visualization: Wash arrays to remove non-specifically bound protein, then incubate with TF-specific primary antibody followed by Cy5-conjugated secondary antibody [39].

Data Acquisition and Normalization: Scan slides using a microarray scanner (e.g., Axon 4000B), analyze with appropriate software (e.g., GenePix 4.1), and normalize protein binding signals against DNA concentration in each spot using Sybr Green or Texas Red-streptavidin [39].

High-Throughput SELEX (HT-SELEX) Protocol

Principle: HT-SELEX combines traditional SELEX methodology with next-generation sequencing to identify TF binding preferences across a pool of random DNA oligonucleotides [40]. Unlike traditional SELEX with multiple selection rounds, HT-SELEX typically uses fewer rounds coupled with deep sequencing to capture both high and moderate affinity binders [40].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Library Preparation: Synthesize a double-stranded DNA library containing random oligonucleotide sequences (typically 10-20 bp random core) flanked by constant regions for amplification.

Binding Reaction: Incubate the purified TF with the DNA library in appropriate binding buffer to allow complex formation.

Partitioning: Separate protein-bound DNA sequences from unbound sequences using methods such as:

- Nitrocellulose filter binding (retains protein-DNA complexes)

- Immunoprecipitation with tagged TFs

- Electrophoretic mobility separation

Elution and Amplification: Recover bound DNA sequences and amplify by PCR for subsequent rounds of selection or sequencing.

Sequencing and Analysis: Subject enriched pools to high-throughput sequencing after 1-3 rounds of selection. Analyze sequence enrichment patterns to determine binding specificities and generate position weight matrices (PWMs) [40].

Mechanically Induced Trapping of Molecular Interactions (MITOMI) Protocol

Principle: MITOMI is a microfluidics-based approach that enables quantitative measurements of TF-DNA binding affinity and kinetics by mechanically trapping interactions between TFs and DNA sequences [40]. This method provides absolute binding constants and can measure both association and dissociation rates [40].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Device Fabrication: Fabricate polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic devices containing:

- Flow channels for reagent delivery

- Button membrane design for mechanical trapping

- Array chambers for parallel measurements

Surface Functionalization: Activate glass substrates for DNA immobilization using appropriate chemistry (e.g., epoxy silane, aldehyde silane).

DNA Printing: Spot double-stranded DNA sequences onto activated surfaces within device chambers.

TF Binding Assay:

- Introduce purified TF through flow channels

- Allow binding equilibrium to establish

- Activate "button" membrane to mechanically trap TF-DNA complexes

- Wash away unbound material while maintaining trapped complexes

Detection and Quantification: Measure bound TF using fluorescent tags (e.g., GFP-fusions or immunofluorescence). Quantify binding levels and calculate affinity constants from concentration-dependent binding curves [40].

Data Analysis and Integration

Binding Affinity Prediction Models

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PC) Model: This statistical approach models TF binding affinity by treating variant DNA sequences as points in high-dimensional Euclidean space, with coordinates reflecting sequence composition [39]. The model offers several advantages over traditional position weight matrices:

- Incorporates effects of interactions between base pair positions

- Requires experimental data from only a subset of binding sites to generate accurate predictions for the entire sequence space

- Sensitive to subtle differences in binding specificities of homologous TFs [39]