Validating Constraint-Based Metabolic Models: A Comprehensive Guide to 13C Labeling Data Integration and Best Practices

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of validating constraint-based metabolic model predictions using 13C labeling data, a cornerstone of metabolic flux analysis.

Validating Constraint-Based Metabolic Models: A Comprehensive Guide to 13C Labeling Data Integration and Best Practices

Abstract

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of validating constraint-based metabolic model predictions using 13C labeling data, a cornerstone of metabolic flux analysis. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we systematically explore the foundational principles of 13C tracer studies, methodological frameworks for data integration, troubleshooting strategies for analytical challenges, and robust validation protocols. The article synthesizes current best practices from recent research, including quality control schemes for mass spectrometry analysis, comparative assessment of validation methodologies, and practical approaches for optimizing model accuracy. By bridging the gap between computational predictions and experimental validation, this resource aims to enhance reliability in metabolic flux quantification and support advancements in biotherapeutic development, systems pharmacology, and precision medicine applications.

Foundations of 13C Tracer Studies and Metabolic Flux Analysis

Core Concepts and Methodological Landscape

Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM) is a computational approach in systems biology that uses genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to simulate cellular metabolism. A foundational technique within CBM is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which predicts steady-state metabolic flux distributions by assuming organisms have evolved to optimize objectives like growth rate or metabolite production [1]. FBA operates on the mass-balance assumption that metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, meaning the production and consumption of each metabolite are balanced [1].

A significant challenge in CBM is model validation—ensuring model predictions accurately reflect biological reality. The integration of 13C labeling data provides a powerful method for validation and constraint. Unlike FBA, which predicts fluxes based on hypothesized objectives, 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is a descriptive method that infers fluxes from experimental data, offering a high degree of validation [1] [2]. Combining these approaches integrates the comprehensive network coverage of GEMs with the empirical validation provided by isotopic labeling experiments [2].

Validating Predictions with 13C Labeling Data

The Validation Challenge

FBA predictions are inherently underdetermined; many flux distributions can satisfy the steady-state mass-balance constraints. Selecting a single solution requires assuming an objective function, the biological relevance of which may be uncertain [1] [2]. 13C labeling experiments provide a solution by delivering empirical data that dramatically constrain the possible flux solutions. The labeling patterns of intracellular metabolites serve as a fingerprint for the in vivo flux map, making the comparison between simulated and measured labels a strong indicator of model accuracy [2].

Integrated Workflow for 13C Validation

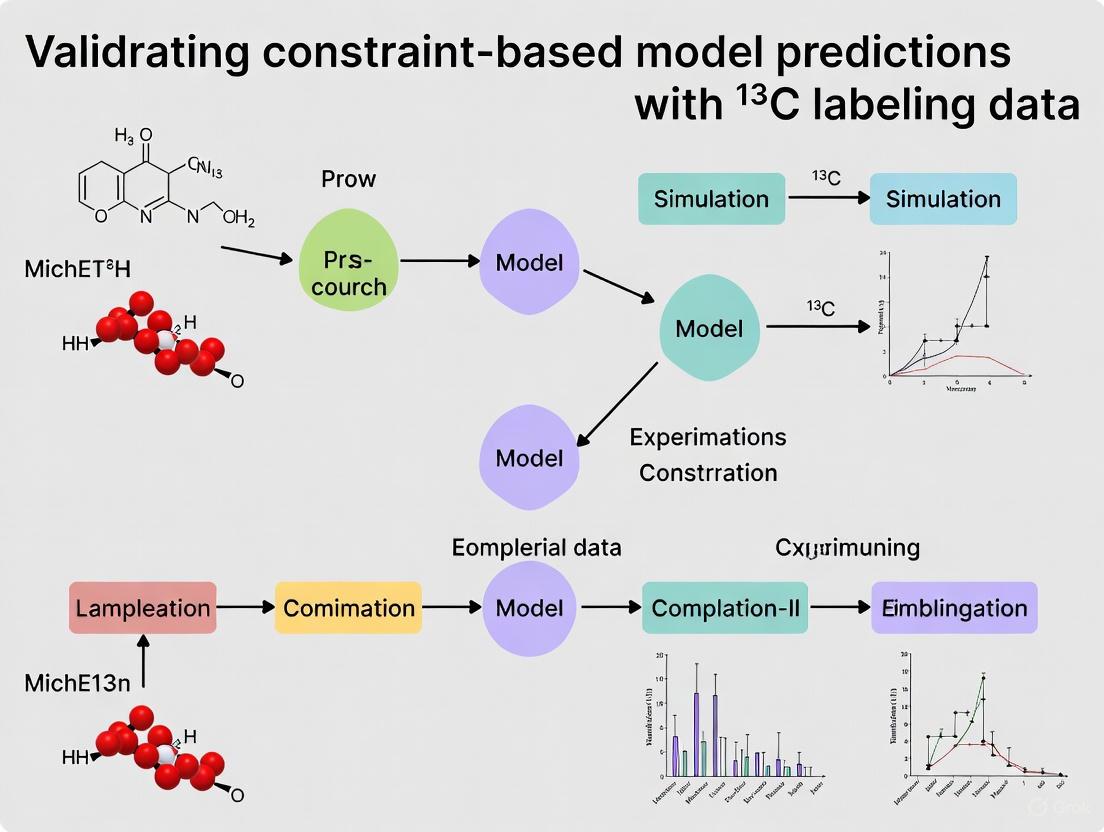

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow for integrating 13C labeling data to validate and improve constraint-based model predictions:

Comparison of Flux Estimation and Validation Techniques

Different computational techniques leverage 13C data, each with distinct strengths and applications as summarized in the table below.

| Technique | Core Methodology | Model Scale | Use of 13C Data | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-MFA [1] [2] | Non-linear fitting of fluxes to match measured Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs). | Core metabolism (typically ~100 reactions). | Directly used as the primary data for flux estimation. | Authoritative flux determination for central carbon metabolism. |

| FBA [1] | Linear programming to optimize a biological objective function (e.g., growth). | Genome-scale (1000+ reactions). | Not used in standard form; validated against 13C-MFA results. | Full-network prediction of flux distributions based on optimization principles. |

| 13C-constrained GEM [2] | Uses 13C-derived flux constraints to reduce solution space in a GEM without assuming an objective. | Genome-scale. | Used to tightly constrain possible flux distributions in a large network. | Providing comprehensive, data-driven flux maps for entire metabolism. |

| INST-MFA [3] | Fitting time-course labeling data to estimate fluxes and metabolite pool sizes. | Core metabolism or sub-networks. | Uses non-stationary (time-resolved) labeling data as primary input. | Flux estimation in autotrophic systems or where stationarity is not reached. |

| Local INST-MFA [3] | Solves ODEs for a sub-network to fit time-course MIDs. | Local sub-networks (e.g., a few reactions). | Uses a subset of non-stationary MIDs for local flux estimation. | Targeted flux estimation when global data is insufficient or computationally prohibitive. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Integrating 13C Data with Genome-Scale Models

This protocol is adapted from a method designed to use 13C labeling data to constrain genome-scale models effectively [2].

Experimental Setup and Data Generation:

- Tracer Selection: Choose an appropriate 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., [1-13C]glucose).

- Cultivation: Grow the organism in a controlled bioreactor with the labeled substrate.

- Sampling and Quenching: Rapidly sample cells during steady-state growth and quench metabolism.

- Metabolite Extraction: Perform intracellular metabolite extraction.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Measure the Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) of key intracellular metabolites using GC-MS or LC-MS.

Computational Integration:

- Network Reconstruction: Use a curated genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli) [4].

- Flux Constraint: Apply the fundamental assumption that "flux flows from core to peripheral metabolism and does not flow back" to resolve the underdetermined system using the 13C data [2].

- Flux Calculation: Solve the model to find the flux distribution that satisfies the stoichiometric constraints and is most consistent with the experimental MIDs. This step eliminates the reliance on a pre-defined optimization objective [2].

- Validation: The goodness-of-fit between the simulated MIDs from the model and the experimentally measured MIDs serves as a direct validation metric [2].

Protocol: Enzyme-Constrained Flux Balance Analysis

This protocol details the process of adding enzyme usage constraints to a standard FBA model, enhancing its biological realism by preventing predictions of unrealistically high fluxes [4].

Model and Data Preparation:

- Base GEM: Start with a well-curated GEM, such as iML1515 for E. coli [4].

- Enzyme Kinetic Data: Collect enzyme turnover numbers (k~cat~ values) from databases like BRENDA. Add k~cat~ values for transport reactions, which are often missing and require estimation [4].

- Proteome Data: Obtain the total protein fraction available for metabolism and enzyme abundance data (e.g., from PAXdb) [4].

- Modify GEM: Split reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions and split reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes to assign unique k~cat~ values [4].

Model Implementation and Simulation:

- Apply Constraints: Use a workflow like ECMpy to impose an overall enzyme mass balance constraint, capping the total flux through an enzyme by its abundance and catalytic capacity [4].

- Parameter Modification: Update model parameters (k~cat~, gene abundance) to reflect genetic engineering (e.g., mutations that remove feedback inhibition or enhance promoter strength) [4].

- Medium Definition: Set uptake reaction bounds to reflect the experimental medium composition [4].

- Lexicographic Optimization: Perform FBA first to optimize for biomass. Then, constrain the model to maintain a percentage of this optimal growth (e.g., 30%) while optimizing for a production objective like L-cysteine export [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below lists key resources for conducting research at the intersection of constraint-based modeling and 13C validation.

| Category | Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Sources / Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | COBRApy [4] | A Python package for performing constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) of metabolic models. | COBRA Toolbox [1] |

| ECMpy [4] | A workflow for incorporating enzyme constraints into GEMs without altering the core stoichiometric matrix. | INCA [3] | |

| INCA [3] | A widely used software for performing 13C-MFA and INST-MFA. | ||

| Databases & Models | Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | A mathematical representation of all known metabolic reactions in an organism. | iML1515 (E. coli) [4], BiGG Models [1] |

| BRENDA Database [4] | A comprehensive enzyme kinetic database, used for sourcing k~cat~ values. | ||

| EcoCyc Database [4] | A bioinformatics database for E. coli, used for GPR relationships and metabolic pathway information. | ||

| Experimental Reagents | 13C-Labeled Substrate | A nutrient source with specific carbon atoms replaced by the 13C isotope for tracing metabolic flux. | [1-13C] Glucose, [U-13C] Glutamine |

| Quenching Solution | Rapidly halts metabolic activity to preserve the in vivo labeling state of metabolites. | Cold methanol solution | |

| Extraction Solvent | Efficiently extracts intracellular metabolites for subsequent MS analysis. | Methanol/chloroform/water |

The Role of Stable Isotope Labeling in Resolving Intracellular Fluxes

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) methods, including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), have become fundamental tools in systems biology for predicting metabolic behavior in various organisms [5]. These genome-scale models use stoichiometric constraints and optimization principles (e.g., growth rate maximization) to predict flux distributions through metabolic networks. However, a significant limitation persists: these predictions often rely on theoretical objectives rather than experimental validation and struggle to accurately resolve parallel pathways, cyclic fluxes, and reversible reactions [6]. The incorporation of stable isotope labeling, particularly 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), addresses these limitations by providing an empirical basis for validating and refining constraint-based model predictions [5] [7]. This guide compares the performance of 13C-MFA against other flux analysis methods and details its critical role in creating rigorously validated, predictive metabolic models.

Comparative Analysis of Metabolic Flux Determination Methods

Methodologies and Workflows

Table 1: Comparison of Major Flux Analysis Techniques

| Feature | Stoichiometric MFA (SFA) | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Input | Extracellular uptake/secretion rates [6] | Genome-scale stoichiometric model [5] | Isotope labeling patterns & extracellular fluxes [5] [6] |

| Core Principle | Stoichiometric mass balances [6] | Optimization of an objective function [5] [6] | Fitting to isotopic steady-state or transients [8] [6] |

| Network Scope | Simplified, central metabolism [6] | Comprehensive, genome-scale [5] | Traditionally core metabolism; can be integrated with genome-scale models [5] |

| Key Assumptions | Metabolic steady state (no accumulation) [6] | Evolutionarily optimized objective [5] | Metabolic & isotopic steady state (for steady-state MFA) [6] |

| Ability to Resolve | Net fluxes | Potential fluxes | True in vivo fluxes, including reversibility & parallel pathways [6] |

Performance and Validation Capabilities

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Application Scope

| Aspect | Stoichiometric MFA | Flux Balance Analysis | 13C-MFA |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Determinacy | Often underdetermined [6] | Grossly underdetermined [5] | Well-constrained by labeling data [5] |

| Flux Resolution | Limited for reversible & parallel pathways [6] | Limited for reversible & parallel pathways [6] | High, directly quantifies reversibility & pathway contributions [6] |

| Validation Strength | Limited, relies on external measurements | Low, produces solution for almost any input [5] | High, mismatch between model fit and data indicates flawed assumptions [5] |

| Primary Application | Basic flux estimation | Full-system predictions, strain design [5] | Authoritative flux determination, model validation [5] [7] |

13C-MFA is considered the "gold standard" for flux measurement [5]. Its principal advantage lies in validation. The comparison of measured and fitted labeling patterns provides a direct check on the model's correctness, a feature lacking in FBA, which can produce a solution for almost any input [5]. Furthermore, 13C-MFA does not presume a cellular objective function, the applicability of which can be questionable, especially in engineered biological systems [5].

Experimental Protocols for 13C-MFA

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a 13C-MFA experiment, integrating wet-lab and computational phases.

Detailed Methodologies

Tracer Selection and Experimental Design

The choice of isotopic tracer is paramount and depends on the specific metabolic pathways under investigation [8]. The fundamental principle is that MFA can only discern the relative contributions of converging pathways when these pathways generate the target metabolite with different isotopic labeling patterns [6].

- Common Tracers: U-13C-glucose (hypothesis-free studies), 1,2-13C-glucose (delineating pentose phosphate pathway from glycolysis), U-13C-glutamine (TCA cycle anaplerosis), U-13C,15N-glutamine (carbon and nitrogen assimilation), 13C-bicarbonate (CO2 incorporation) [8].

- Labeling Kinetics: For steady-state MFA, the system must reach an isotopic steady state, where the labeling pattern no longer changes over time. The time to reach this state varies; central carbon metabolites may reach it in seconds, while secondary metabolites and macromolecules can take several cell cycles [8]. As an alternative, isotopically nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA) can be used to study isotope incorporation before it reaches steady state, providing enhanced flux resolution [8].

Cultivation, Sampling, and Quenching

Biological systems are cultivated in precisely controlled environments (e.g., chemostats) with the labeled substrate. A critical step is the rapid quenching of metabolic activity to capture the instantaneous metabolic state [8]. This is typically achieved using cold methanol or other cryogenic methods to instantly halt enzyme activity. Subsequent metabolite extraction must ensure high recovery and stability of a broad range of metabolites [8].

Mass Spectrometry Measurement and Data Processing

Extracted metabolites are analyzed using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). The mass spectrometer detects the Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID)—the fractional abundance of molecules with 0, 1, 2, ... 13C atoms incorporated [8] [5].

The raw MID data must be corrected for natural abundance of 13C and other heavy isotopes, which is present even in unlabeled samples [8]. This is crucial for accurate flux estimation, especially for small molecules analyzed on unit-resolution mass spectrometers.

Integrating 13C-MFA with Constraint-Based Models

A Hybrid Approach for Genome-Scale Validation

A powerful advancement in the field is the direct use of 13C labeling data to constrain genome-scale models, eliminating the sole reliance on hypothetical optimization objectives [5]. This hybrid approach leverages the comprehensive network coverage of COBRA models and the strong, empirical flux constraints provided by 13C-MFA.

Table 3: Software Tools for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Software | Main Features | Supported Data | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13CFLUX2 | Multi-platform compatibility | MS, NMR | [6] |

| INCA | Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA | MS, NMR | [6] |

| OpenFLUX | Steady-state 13C MFA, supports experimental design | MS | [6] |

| FiatFlux | User-friendly, focused on 13C glucose tracers and flux ratios | GC-MS | [6] |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework of this integration, showing how 13C-labeling data provides a critical constraint to reduce the solution space of a genome-scale model.

Application Case Study: Stress Response inClostridium acetobutylicum

A study on C. acetobutylicum under butanol stress demonstrates the practical power of this integrated approach [9]. Researchers performed 13C-MFA to obtain precise flux measurements for central carbon metabolism in chemostat cultures under stress. These experimentally determined fluxes were then used as additional constraints in a genome-scale COBRA model.

The hybrid model revealed how butanol stress altered cellular metabolism, pinpointing specific effects on the TCA cycle and serine/glycine pathway that were not apparent from transcriptomic or proteomic data alone [9]. This provided a quantitative, systems-level understanding of the organism's stress response, which is valuable for bioengineering more robust industrial strains.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA Experiments

| Item | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracer | To introduce a measurable label into the metabolic network. | U-13C-Glucose, 1,2-13C-Glucose. Purity is critical. Cost can be a factor for large-scale studies [8]. |

| Quenching Solution | To instantaneously halt metabolic activity at the time of sampling. | Cold methanol buffer (-40°C to -48°C). Must rapidly penetrate cells without causing metabolite leakage [8]. |

| Extraction Solvent | To liberate intracellular metabolites for analysis. | Chloroform-methanol-water mixtures or boiling ethanol. Choice depends on metabolite classes of interest [8]. |

| Internal Standards | To account for analyte loss during sample preparation. | Stable isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., 13C/15N-amino acids) added immediately upon extraction [8]. |

| Derivatization Agent | To make metabolites volatile for GC-MS analysis. | MSTFA (N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide) for silylation. |

| Mass Spectrometer | To measure the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of metabolites. | GC-MS or LC-MS. High-resolution instruments provide better separation of overlapping mass peaks [8]. |

| MFA Software | To computationally estimate fluxes from labeling data. | INCA, 13CFLUX2. Implements the model-fitting algorithms [6]. |

Stable isotope labeling, particularly through 13C-MFA, has transformed our ability to resolve intracellular fluxes with high precision. It moves metabolic research beyond static stoichiometric models and hypothetical optimization principles, providing a robust, empirical tool for directly measuring in vivo reaction rates. The integration of 13C-derived flux constraints with genome-scale models represents the state of the art, creating powerful, validated frameworks for predicting cellular behavior. This approach is indispensable for advancing fields from industrial biotechnology, where it guides the engineering of high-yield microbial cell factories [9], to biomedical research, where it helps uncover the altered metabolic pathways underlying diseases like cancer [7] [6].

Principles of 13C Isotope Incorporation and Metabolic Tracing

Stable isotope tracing using 13C-labeled substrates has emerged as a cornerstone technique for investigating intracellular metabolic fluxes in living systems. This methodology enables researchers to move beyond static metabolic snapshots toward dynamic, quantitative assessments of pathway activities. Within the field of constraint-based metabolic modeling, 13C labeling data provides an essential experimental constraint for validating and refining model predictions, bridging the gap between theoretical flux distributions and empirical biological behavior. This guide examines the core principles of 13C incorporation, compares key analytical approaches, and details protocols for implementing these techniques to strengthen metabolic model validation.

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) represents the gold standard for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes—the rates at which metabolites flow through biochemical pathways in living cells [10]. Cellular metabolism serves four fundamental functions in proliferating cells: supplying anabolic building blocks for growth, generating ATP, producing redox equivalents like NADPH, and maintaining redox homeostasis [10]. While metabolomics provides valuable information about metabolite concentrations, and extracellular flux measurements reveal nutrient consumption and waste secretion, these data alone cannot elucidate the complex network of intracellular pathway activities due to extensive redundancies in metabolic pathways [11] [10].

The fundamental principle underlying 13C-MFA involves introducing a 13C-labeled substrate (tracer) to a biological system, allowing it to be metabolized, and then measuring the resulting labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites [11] [10]. As the tracer flows through metabolic networks, enzymatic reactions rearrange carbon atoms, creating specific isotopic labeling patterns in downstream metabolites that serve as fingerprints for the activity of various metabolic pathways [10]. For a well-selected tracer, different metabolic pathways produce distinctly different labeling patterns from which fluxes can be inferred through computational modeling [10].

Table 1: Key Terminology in 13C Metabolic Tracing

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Metabolic Flux | The rate at which metabolites flow through biochemical reactions (nmol/10⁶ cells/h) [10] |

| Isotopologue | Molecules that differ only in their isotopic composition (e.g., number of 13C atoms) [11] |

| Isotopomer | Molecules with the same isotopic composition but differing in the position of the isotopes [11] |

| Mass Distribution Vector (MDV) | The fractional abundance of each isotopologue for a metabolite, from M+0 to M+n [11] |

| Metabolic Steady State | Condition where intracellular metabolite levels and metabolic fluxes are constant [11] |

| Isotopic Steady State | Condition where 13C enrichment in metabolites is stable over time [11] |

A critical distinction in 13C-MFA is between metabolic steady state (constant metabolite levels and fluxes) and isotopic steady state (stable 13C enrichment over time) [11]. Metabolic steady state is often assumed during exponential growth phase when nutrient supply is non-limiting, while the time to reach isotopic steady state varies significantly depending on the tracer used and the metabolites analyzed—from minutes for glycolytic intermediates to hours for TCA cycle intermediates [11]. Proper interpretation of labeling data requires careful assessment of both metabolic and isotopic steady states [11].

Core Methodologies and Comparative Analysis

Analytical Frameworks for Flux Determination

Several computational frameworks have been developed to interpret 13C labeling data and calculate metabolic fluxes, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The key methodologies include:

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA): This approach uses data from 13C labeling experiments with a limited reaction stoichiometry (typically central carbon metabolism) and measured extracellular fluxes to calculate intracellular fluxes [2] [5]. It involves solving a nonlinear fitting problem where fluxes are parameters estimated by minimizing differences between measured and simulated labeling patterns [2]. 13C-MFA is considered highly authoritative for flux determination but is generally limited to core metabolic pathways [2].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): FBA utilizes genome-scale metabolic models reconstructed from genomic data and assumes metabolism has been evolutionarily tuned to optimize an objective function, typically growth rate [2] [5]. While FBA provides comprehensive system-wide coverage, it relies heavily on optimization assumptions that may not hold true in all biological contexts, particularly engineered strains not under long-term evolutionary pressure [2].

Hybrid Methods: Recent approaches aim to combine the complementary strengths of 13C-MFA and FBA by incorporating 13C labeling data as constraints for genome-scale models, eliminating the need for assumption-based optimization principles [2] [5]. These methods leverage the strong flux constraints provided by labeling data while maintaining the comprehensive coverage of genome-scale models [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Flux Analysis Methods

| Method | Model Scope | Key Inputs | Key Assumptions | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-MFA | Core metabolism (50-100 reactions) [2] | Extracellular fluxes, 13C labeling patterns [10] | Metabolic and isotopic steady state [11] | Authoritative flux determination in central carbon metabolism [2] |

| FBA | Genome-scale (1000+ reactions) [2] | Genome-scale model, optimization objective | Evolution optimizes objective function (e.g., growth) [2] | System-wide prediction, strain design, community modeling [2] |

| Constrained FBA | Genome-scale [5] | 13C labeling data, extracellular fluxes | Flux flows from core to peripheral metabolism without backflow [5] | Integrating experimental data with genome-scale models [5] |

Essential Software Tools

Several software packages have been developed to perform 13C-MFA calculations, implementing sophisticated algorithms to simulate isotopic labeling and estimate fluxes:

METRAN: Based on the Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU) framework developed at MIT, this software facilitates 13C-MFA, tracer experiment design, and statistical analysis [12]. The EMU framework dramatically improves computational efficiency for simulating isotopic labeling in complex metabolic networks [10].

13CFLUX2: A high-performance software suite implementing both Cumomer and EMU algorithms, capable of handling large metabolic networks (e.g., 313 metabolites, 359 reactions) [13]. It provides tools for network modeling, isotope labeling simulation, parameter estimation, and statistical analysis [13].

INCA: Another user-friendly software tool that incorporates the EMU framework, making 13C-MFA accessible to researchers without extensive mathematical backgrounds [10].

These tools have been instrumental in democratizing 13C-MFA, enabling cancer biologists and other researchers to apply these powerful techniques without requiring deep expertise in computational modeling [10].

Figure 1: 13C-MFA Workflow. The process begins with tracer selection and progresses through experimental and computational phases to flux interpretation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Tracer Selection and Experimental Design

The precision of fluxes determined by 13C-MFA depends significantly on the choice of isotopic tracers and specific labeling measurements [14]. Optimal tracer selection has evolved with the advent of parallel labeling experiments, where multiple complementary tracers are used simultaneously to improve flux resolution [14].

Optimal Tracer Strategies:

Single Tracer Experiments: Doubly 13C-labeled glucose tracers, including [1,6-13C]glucose, [5,6-13C]glucose, and [1,2-13C]glucose, consistently produce the highest flux precision across different metabolic flux maps [14]. Pure glucose tracers generally outperform glucose tracer mixtures [14].

Parallel Labeling Experiments: The optimal combination for parallel labeling is [1,6-13C]glucose and [1,2-13C]glucose, which improves flux precision by nearly 20-fold compared to the commonly used tracer mixture 80% [1-13C]glucose + 20% [U-13C]glucose [14].

Precision and Synergy Scoring: To evaluate tracer performance, researchers use two key metrics:

- Precision Score (P): Quantifies the improvement in flux confidence intervals compared to a reference tracer experiment [14].

- Synergy Score (S): Measures the additional information gained from combining multiple tracers beyond what would be expected from simple additive effects [14].

Determination of External Rates

Accurate quantification of extracellular fluxes is essential for constraining 13C-MFA models [10]. These measurements capture the cross-talk between cells and their environment:

For exponentially growing cells: Nutrient uptake and waste secretion rates (ri, in nmol/10⁶ cells/h) are calculated using: [ ri = 1000 \cdot \frac{\mu \cdot V \cdot \Delta Ci}{\Delta N_x} ] where μ is growth rate (1/h), V is culture volume (mL), ΔCi is metabolite concentration change (mmol/L), and ΔNx is change in cell number (millions of cells) [10].

For non-proliferating cells: [ ri = 1000 \cdot \frac{V \cdot \Delta Ci}{\Delta t \cdot N_x} ] where Δt is time interval and Nx is cell number [10].

Key Considerations:

- Correct for glutamine degradation in culture media (approximately 0.003/h degradation constant) [10].

- For extended experiments (>24 hours), perform control experiments without cells to correct for evaporation effects [10].

- Typical values for proliferating cancer cells: glucose uptake 100-400, lactate secretion 200-700, glutamine uptake 30-100 nmol/10⁶ cells/h [10].

Measurement of Isotopic Labeling

Mass spectrometry (MS) is the primary analytical technique for measuring isotopic labeling, with two main approaches:

Gas Chromatography-MS (GC-MS): Requires chemical derivatization to enable metabolite separation and detection. This adds additional atoms (C, H, N, O, Si) that must be accounted for during natural isotope correction [11].

Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS): Enables analysis of underivatized metabolites, where naturally occurring 13C (1.07% natural abundance) has the most significant effect and must be corrected [11].

Data Correction: The measured mass isotopomer distributions must be corrected for naturally occurring isotopes using a correction matrix [11]: [ \begin{pmatrix} I0 \ I1 \ I2 \ \vdots \ I{n+u}

\end{pmatrix}

\begin{pmatrix} L0M0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \ L1M0 & L0M1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \ L2M0 & L1M1 & L0M2 & \cdots & 0 \ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \ L{n+u}M0 & L{n+u-1}M1 & L{n+u-2}M2 & \cdots & LuMn \end{pmatrix} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} M0 \ M1 \ M2 \ \vdots \ Mn \end{pmatrix} ] Where vector I represents measured fractional abundances, M is the MDV corrected for natural isotopes, and L is the correction matrix [11].

Figure 2: Central Carbon Metabolic Network. Key pathways include glycolysis, TCA cycle, and branching points for biosynthetic precursors. Dashed lines represent anaplerotic/cataplerotic reactions.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 13C Tracing Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1,2-13C]glucose, [1,6-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine [14] [15] | Metabolic tracers for elucidating pathway fluxes; optimal tracers identified through systematic evaluation [14] |

| Analytical Standards | 13C-labeled internal standards for GC-MS/LC-MS | Quantification of metabolite concentrations and correction for instrumental variance |

| Enzymatic Assay Kits | Metabolite detection kits (lactate, glutamate, etc.) | Validation of extracellular flux measurements |

| Cell Culture Media | Custom formulations without unlabeled components that would dilute tracer | Maintain effective isotopic enrichment throughout experiments |

| Derivatization Reagents | MSTFA, TBDMS for GC-MS analysis | Chemical modification of metabolites for chromatographic separation and detection [11] |

| Quality Controls | Natural abundance standards, process blanks | Verification of instrument performance and data quality |

Cost Considerations: The expense of 13C-labeled compounds has decreased significantly with improved synthesis methods and increased demand. For example, D-glucose-13C6 has dropped from approximately $500/g fifteen years ago to under $100/g currently [16].

Applications in Constraint-Based Model Validation

The integration of 13C labeling data with constraint-based models represents a significant advancement in metabolic engineering and systems biology. This hybrid approach addresses fundamental limitations in both traditional methodologies:

Validating FBA Predictions: 13C-MFA derived fluxes serve as an authoritative reference for testing FBA-based methods [2]. Studies have used 13C-MFA to validate various algorithms including MOMA and IOMA, and to compare predictions using different biological objectives [2].

Constraining Genome-Scale Models: Novel methods now enable the use of 13C labeling data to constrain fluxes in genome-scale models without assuming evolutionary optimization principles [2] [5]. This approach:

- Provides more robust flux predictions than FBA alone, especially regarding errors in model reconstruction [5]

- Enables comprehensive metabolite balancing and predictions for unmeasured extracellular fluxes [5]

- Offers validation through comparison of measured and simulated labeling patterns [2]

Enhancing Cancer Metabolism Research: 13C-MFA has revealed critical pathway alterations in cancer cells, including:

- Aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) [10] [16]

- Reductive glutamine metabolism [10]

- Altered serine, glycine, and one-carbon metabolism [10]

- Transketolase-like 1 (TKTL1) pathway activity [10]

- Acetate metabolism [10]

Clinical Diagnostic Applications: 13C tracing has found clinical utility in non-invasive diagnostics:

- 13C-urea breath test: Detection of Helicobacter pylori infection [15]

- Hyperpolarized 13C MR spectroscopic imaging: Emerging technique for monitoring metabolic fluxes in prostate cancer and other diseases using dynamically polarized 13C-labeled substrates that provide >10,000-fold signal enhancement [16]

13C isotope incorporation and metabolic tracing provide powerful methodologies for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes and validating constraint-based model predictions. The core strength of this approach lies in its ability to translate measured isotopic labeling patterns into quantitative flux maps that reflect the integrated activity of metabolic networks under physiological conditions. As the field advances, key developments including optimized tracer strategies, parallel labeling experiments, improved computational frameworks, and integration with genome-scale models are enhancing the resolution and scope of flux analysis. For researchers seeking to validate metabolic model predictions, 13C labeling data provides an essential experimental constraint that bridges the gap between theoretical flux distributions and actual cellular physiology, enabling more accurate modeling of biological systems for both basic research and applied metabolic engineering.

Key Metabolic Pathways Amenable to 13C Flux Analysis

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as the gold standard technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells. By tracing the fate of 13C-labeled atoms through metabolic networks, researchers can obtain quantitative maps of carbon flow that provide unprecedented insights into cellular physiology. This capability is particularly valuable for validating and refining constraint-based metabolic models, as 13C labeling data provides independent experimental constraints that eliminate reliance solely on optimization principles like growth rate maximization [5]. The integration of 13C-MFA with computational modeling has become indispensable for understanding metabolic adaptations in cancer, engineering microbial cell factories, and unraveling complex metabolic diseases.

Core Pathways for 13C Flux Analysis

Table 1: Key Metabolic Pathways Quantifiable by 13C-MFA

| Metabolic Pathway | Key Fluxes Measured | Biological Significance | Common Tracers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis & Warburg Effect | Glucose uptake, lactate secretion, pyruvate kinase flux [10] | Aerobic glycolysis in cancer; energy production [10] | [1,2-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose |

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) | Oxidative vs. non-oxidative PPP flux, NADPH production [17] | Ribose-5P for nucleotides; NADPH for biosynthesis/redox [10] | [1,2-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose |

| Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle | Citrate synthase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, malic enzyme flux [10] [17] | ATP generation; precursor supply (e.g., for lipids) [10] | [U-13C]Glutamine, [1,2-13C]Glucose |

| Glutamine Metabolism | Glutamine uptake, reductive carboxylation [10] | Nitrogen/carbon source; alternative to glucose for acetyl-CoA [10] | [U-13C]Glutamine |

| Serine & Glycine Metabolism | Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase flux, one-carbon metabolism [10] | Biosynthetic precursors; nucleotides and redox balance [10] | [U-13C]Glucose, [3-13C]Serine |

| Transketolase-like 1 (TKTL1) Pathway | Non-oxidative PPP flux via TKTL1 [10] | Proposed role in cancer metabolism [10] | [1,2-13C]Glucose |

| Acetate Metabolism | Acetate uptake, acetyl-CoA synthetase flux [10] | Lipid synthesis; energy source when glucose is low [10] | [1,2-13C]Acetate, [U-13C]Acetate |

Experimental Protocol for 13C-MFA

A standardized workflow is crucial for generating reliable, reproducible flux data that can robustly constrain metabolic models.

Tracer Experiment Design and Culture

The foundation of 13C-MFA is a carefully designed tracer experiment. Cells are cultivated in a strictly minimal medium where the sole carbon source is replaced with a specifically chosen 13C-labeled substrate [18].

- Tracer Selection: The choice of tracer is paramount. A well-studied glucose mixture of 80% [1-13C] and 20% [U-13C] glucose is often used to ensure high-resolution flux elucidation [18]. For pathway discovery, singly labeled substrates like [1-13C]glucose can be easier to interpret [18].

- Culture Modes: To reach a metabolic and isotopic steady state—where both metabolite concentrations and their isotopic labeling are constant—two primary culture modes are employed:

- Duration: The labeling duration must be sufficient for isotopes to distribute fully, typically more than five residence times, to ensure isotopic steady state is reached [19].

Measurement of Isotopic Labeling

After cultivation, the isotopic labeling of intracellular metabolites is accurately measured.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Gas Chromatography-MS (GC-MS) and Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS) are the most common platforms. GC-MS often requires chemical derivatization of metabolites (e.g., using TBDMS) for volatility [18]. LC-MS is suitable for unstable or trace metabolites and avoids derivatization [18] [19].

- Data Correction: Raw MS data must be corrected for natural abundance of heavy isotopes (e.g., 13C, 15N, 18O) present in the metabolite itself and any derivatization agents. This yields the Mass Distribution Vector (MDV) or Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID), which describes the fractional abundance of each isotopologue for a metabolite [18] [11].

Model-Based Flux Estimation

The core of 13C-MFA is a computational parameter estimation problem that infers fluxes from MDV/MID data.

- Inputs: The analysis requires three key inputs: 1) measured external rates (nutrient uptake, product secretion, growth rate), 2) the MDV/MID data, and 3) a stoichiometric model of the metabolic network [10].

- Mathematical Framework: The problem is formulated as a least-squares optimization, where fluxes are estimated by minimizing the difference between measured and model-simulated labeling patterns [10] [20]. The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework is a core computational method that decomposes the network for efficient simulation of isotopic labeling [10] [18].

- Software: User-friendly software packages like INCA and Metran, which implement the EMU framework, have made 13C-MFA accessible to non-experts [10] [18].

Model Selection and Statistical Validation

Choosing the correct metabolic network model is critical for obtaining accurate fluxes.

- Goodness-of-Fit: The model fit is typically evaluated using a χ2-test, where the minimized sum of squared residuals (SSR) between measured and simulated data is compared to a statistical threshold [21] [22].

- Validation-Based Model Selection: A robust approach involves using independent validation data (e.g., from a different tracer) not used for model fitting. The model that best predicts this validation data is selected, which is more reliable than methods relying solely on the χ2-test, especially when measurement errors are uncertain [21] [22].

- Confidence Intervals: Sensitivity analysis and Monte Carlo simulations are used to quantify the uncertainty and establish confidence intervals for each estimated flux [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for 13C-MFA

| Category | Specific Item / Software | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glutamine | Carbon source for tracing; reveals different pathway activities [18] [19] |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS, LC-MS/MS, NMR | Measures isotopic labeling in metabolites (MDV/MID) [18] [19] [11] |

| Derivatization Reagents | TBDMS, BSTFA | Renders metabolites volatile for GC-MS analysis [18] |

| Cell Culture Media | Custom minimal medium | Ensures the labeled substrate is the sole carbon source [18] |

| 13C-MFA Software | INCA, Metran, 13CFLUX2, OpenFLUX2 | Performs computational flux estimation using the EMU framework [10] [18] |

Case Study: Guiding Metabolic Engineering with 13C-MFA

A compelling application of 13C-MFA is in metabolic engineering. In a study aimed at improving acetol production in E. coli from glycerol, 13C-MFA was performed on a first-generation producer strain [17]. The flux map revealed a critical bottleneck: a shortage of NADPH supply, evidenced by a reversal of transhydrogenase flux (NADH → NADPH) to meet the demand for acetol biosynthesis [17]. This insight directly guided subsequent engineering. The authors overexpressed nadK (NAD kinase) and pntAB (transhydrogenase) to enhance NADPH regeneration. The resulting strain showed a 3-fold increase in acetol titer, and follow-up 13C-MFA confirmed the predicted rewiring: increased carbon flux toward acetol and enhanced transhydrogenation flux [17]. This exemplifies the power of 13C-MFA in a design-build-test-learn cycle for strain development.

13C-MFA provides an unparalleled, quantitative view of active metabolic pathways, moving beyond static omics measurements to reveal the functional state of cellular metabolism. The pathways detailed in this guide—from core carbon metabolism to specialized pathways like reductive glutamine metabolism—are central to understanding physiology in contexts ranging from cancer to bioproduction. The rigorous experimental and computational framework of 13C-MFA generates the high-quality data essential for validating and refining genome-scale constraint-based models, moving them from theoretical constructs to accurate predictors of cellular behavior. As both analytical technologies and modeling software continue to advance, the resolution and scope of 13C-MFA will further expand, solidifying its role as a cornerstone technique in metabolic research.

Comparison of Qualitative vs. Quantitative Flux Evaluation Approaches

Metabolic fluxes represent the in vivo conversion rates of metabolites through biochemical pathways, forming an integrated functional phenotype that emerges from multiple layers of biological organization and regulation [23] [24]. Investigating cellular metabolism through flux analysis has a long-standing history across biochemistry, biotechnology, and biomedical research, with increasing recognition that altered cellular metabolism contributes to many diseases including cancer, metabolic syndromes, and neurodegenerative disorders [11]. In the context of validating constraint-based model predictions, 13C labeling data provide crucial experimental constraints that either corroborate or challenge model-derived fluxes, creating an essential feedback loop for model refinement and validation [2] [24].

Flux evaluation approaches span a spectrum from qualitative interpretation of isotope labeling patterns to fully quantitative computational flux estimation. The choice between qualitative and quantitative approaches depends on research goals, available resources, and the required level of precision [23]. Qualitative fluxomics (isotope tracing) enables rapid assessment of pathway activities, while quantitative methods like 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) provide rigorous quantification of intracellular reaction rates [23] [10]. This guide objectively compares these approaches, focusing on their application in validating constraint-based model predictions with 13C labeling data.

Classification Framework for Flux Evaluation Methods

Stable isotope-based flux analysis methods have evolved into a diverse family of techniques with varying capabilities and applications [23]. The classification spans from purely qualitative approaches to increasingly sophisticated quantitative frameworks, with key methodological branches distinguished by their data requirements, computational complexity, and analytical output.

This classification framework illustrates the hierarchical relationship between major flux analysis approaches, with color coding indicating the progression from qualitative (green) to implementation-level methods (red). The diagram shows how broader categories branch into specific technical implementations, each with distinct methodological characteristics.

Comparative Analysis of Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches

Methodological Comparison

The choice between qualitative and quantitative flux evaluation approaches involves significant trade-offs in analytical depth, experimental requirements, and interpretative power. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each major approach:

| Feature | Qualitative Fluxomics (Isotope Tracing) | 13C Flux Ratios Analysis | Kinetic Flux Profiling (KFP) | 13C-MFA (Stationary & Instationary) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Scope | Local pathway activity assessment | Relative fluxes at metabolic branch points | Local subnetworks with linear kinetics | Comprehensive network flux quantification |

| Quantitative Rigor | Qualitative (present/absent, increased/decreased) | Semi-quantitative (relative proportions) | Semi-quantitative (absolute fluxes for linear pathways) | Fully quantitative (absolute flux values) |

| Data Requirements | Single tracer, endpoint labeling measurements | Single tracer, positional labeling preferred | Time-course labeling + metabolite pool sizes | Multiple tracers, extensive labeling measurements |

| Computational Complexity | Low (intuitive interpretation) | Medium (direct calculation from labeling differences) | Medium (exponential fitting of labeling kinetics) | High (nonlinear regression, parameter estimation) |

| Key Assumptions | Pathway activity correlates with labeling incorporation | Metabolic and isotopic steady state | Metabolic steady state, first-order kinetics | Metabolic steady state (SS-MFA) or metabolic + isotopic steady state (INST-MFA) |

| Limitations | No flux quantification, prone to misinterpretation | Limited to converging pathways, requires specific atom transitions | Restricted to linear pathways or simple subnetworks | Computationally intensive, requires careful experimental design |

| Applications | Rapid pathway screening, hypothesis generation | Analysis of metabolic bifurcations, relative pathway contributions | Metabolic channeling, pathway linear sections | Comprehensive metabolic phenotyping, systems biology |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The statistical rigor and reliability of flux estimates vary significantly across approaches, with formal quantitative methods providing measurable confidence intervals and uncertainty assessments:

| Performance Metric | Qualitative Fluxomics | 13C Flux Ratios | 13C-MFA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Resolution | None | Relative percentages only | Absolute values (nmol/10^6 cells/h or similar) |

| Precision Assessment | Not applicable | Limited to specific branch points | Confidence intervals, statistical goodness-of-fit tests |

| Experimental Validation | Indirect, through pathway inference | Internal consistency checks | χ²-test of goodness-of-fit, residual analysis |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Not available | Not typically performed | Flux uncertainty estimation, sensitivity analysis |

| Information Content | Low (binary: active/inactive) | Medium (local flux relationships) | High (comprehensive flux map) |

| Typical Flux Uncertainty | N/A | ~10-30% for major branches | ~5-15% for central carbon metabolism |

Quantitative 13C-MFA typically achieves flux uncertainties of 5-15% for central carbon metabolism when using optimal experimental designs [24] [10]. The precision can be further improved to under 5% uncertainty through parallel labeling experiments employing multiple tracers simultaneously [24] [25]. This level of precision enables detection of physiologically relevant flux changes in response to genetic and environmental perturbations.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Qualitative Flux Analysis Protocol

Objective: Rapid identification of active metabolic pathways and qualitative assessment of pathway contributions.

Tracer Selection and Experimental Design:

- Tracer Choice: Single labeled substrate sufficient (e.g., [1-13C]glucose or [U-13C]glutamine)

- Experimental Setup: Cells are cultured with the labeled tracer until isotopic steady state is reached for target metabolites

- Duration: Typically 2-3 cell doublings to ensure sufficient labeling incorporation

- Controls: Unlabeled control for natural abundance correction

Sample Processing and Data Acquisition:

- Metabolite Extraction: Use cold methanol-water extraction for intracellular metabolites

- Analysis Platform: GC-MS or LC-MS for mass isotopomer distribution (MID) analysis

- Data Collection: Measure M+0, M+1, M+2, ... M+n isotopologue fractions for target metabolites

- Data Correction: Apply natural abundance correction using standard algorithms [11]

Data Interpretation:

- Identify presence of specific labeling patterns indicative of pathway activities

- Compare relative enrichment across conditions (increased/decreased)

- Map labeling patterns onto metabolic pathways to infer route utilization

Quantitative 13C-MFA Protocol

Objective: Precise quantification of intracellular metabolic fluxes with statistical confidence assessment.

Comprehensive Tracer Design:

- Tracer Strategy: Parallel labeling with multiple tracers recommended (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, [1-13C]glutamine)

- Experimental Setup: Metabolic and isotopic steady state required

- Culture Conditions: Controlled bioreactors or carefully monitored culture systems

- Validation: Time-course labeling to verify isotopic steady state [11] [10]

Multi-Omics Data Collection:

- External Flux Measurements:

- Growth rate determination via cell counting or biomass measurement

- Nutrient uptake rates (glucose, glutamine, etc.)

- Product secretion rates (lactate, ammonium, etc.)

- Calculation using established formulas [10]

Isotopic Labeling Analysis:

- Comprehensive MID measurements for intracellular metabolites

- Positional labeling via NMR or tandem MS where possible

- Multiple analytical platforms (GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR) for cross-validation

Additional Constraints:

- Metabolite pool sizes for INST-MFA

- Enzyme activity assays where available

- Thermodynamic constraints

Computational Flux Estimation:

- Metabolic Network Reconstruction:

- Define stoichiometric matrix including atom transitions

- Include all major central carbon metabolic pathways

- Define system boundaries and exchange fluxes

Flux Parameter Estimation:

- Apply computational fitting using specialized software (INCA, Metran, OpenFLUX)

- Minimize difference between measured and simulated labeling patterns

- Implement statistical evaluation of fit quality

Validation and Uncertainty Analysis:

- Perform χ²-test for goodness-of-fit

- Calculate confidence intervals for all estimated fluxes

- Conduct sensitivity analysis to identify most influential measurements [24]

The experimental workflow for quantitative flux analysis shows the sequential steps from experimental design through model validation, highlighting the integration of multiple data sources (green nodes) with computational modeling steps (red nodes) and foundational elements (yellow nodes).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of flux analysis methods requires specific reagents, tools, and computational resources. The following table details essential components of the metabolic flux analysis toolkit:

| Category | Item | Specification/Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | 13C-labeled substrates | [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, [1-13C]glutamine | Purity >99%; cost ranges $100-$600/g; selection depends on pathways of interest |

| Cell Culture Supplies | Defined culture media | Glucose-free, glutamine-free formulations | Custom formulation required for specific tracer studies |

| Bioreactors/Culture systems | Controlled environment systems | Essential for maintaining metabolic steady state | |

| Analytical Instruments | Mass Spectrometers | GC-MS, LC-MS, GC-MS/MS | GC-MS most common for derivatized metabolites |

| NMR Spectrometers | 1H, 13C capabilities | Provides positional labeling information | |

| Sample Preparation | Metabolite extraction kits | Methanol:water:chloroform systems | Maintain metabolite stability during processing |

| Derivatization reagents | MSTFA, TBDMS for GC-MS | Enhance volatility for GC-MS analysis | |

| Computational Tools | 13C-MFA Software | INCA, Metran, OpenFLUX | Require stoichiometric model and carbon transitions |

| Statistical analysis packages | MATLAB, R with custom scripts | For data preprocessing, natural abundance correction | |

| Reference Materials | Natural abundance standards | Unlabeled metabolite standards | Essential for correction algorithms |

| Isotopic standards | Fully labeled metabolite standards | Method validation and quality control |

Applications in Constraint-Based Model Validation

The integration of 13C labeling data with constraint-based models represents a powerful approach for validating and refining metabolic predictions. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and related constraint-based methods generate flux predictions based on optimization principles, but these require experimental validation to ensure biological relevance [2] [24].

13C-MFA serves as a gold standard for validating FBA predictions, particularly for central carbon metabolism. The comparison of MFA-derived fluxes with FBA predictions enables identification of inconsistencies in model structure, objective function formulation, or constraint specification [2]. This validation is crucial for improving model accuracy and predictive capability, especially in biomedical applications where metabolic dysregulation plays a key pathophysiological role [10].

Recent methodological advances enable direct integration of 13C labeling data as constraints in genome-scale models, bridging the gap between detailed 13C-MFA studies and comprehensive genome-scale simulations [2]. This integration provides a mechanism for using the rich information content of isotopic labeling to refine flux predictions throughout the metabolic network, not just in central carbon metabolism.

Qualitative and quantitative flux evaluation approaches offer complementary capabilities for investigating cellular metabolism. Qualitative fluxomics provides rapid, accessible assessment of pathway activities with minimal computational requirements, making it ideal for initial screening and hypothesis generation. In contrast, quantitative 13C-MFA delivers comprehensive, statistically rigorous flux quantification at the cost of greater experimental and computational complexity.

The selection between these approaches should be guided by research objectives, with qualitative methods sufficient for identifying pathway activation states, and quantitative methods necessary for precise flux quantification and detailed metabolic phenotyping. For constraint-based model validation, quantitative 13C-MFA provides the gold standard for flux validation, while qualitative approaches can rapidly screen multiple conditions to identify optimal scenarios for detailed quantitative analysis.

As flux analysis methodologies continue to evolve, ongoing developments in parallel labeling experiments, tandem MS for positional labeling, and integration with genome-scale models will further enhance the resolution and scope of both qualitative and quantitative flux evaluation approaches.

Experimental Design Considerations for Tracer Selection

A critical challenge in 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) is the selection of an appropriate isotopic tracer to observe fluxes within a proposed network model [26]. The choice of tracer fundamentally determines the information content of an experiment, as metabolic conversion of labeled substrates generates molecules with distinct labeling patterns (isotopomers) that can be measured to infer intracellular reaction rates [26] [10]. Despite the importance of 13C-MFA in metabolic engineering and biomedical research, approaches for tracer experiment design have historically relied on trial-and-error rather than rational methodology [26]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of tracer selection strategies and their performance, with particular emphasis on validating constraint-based model predictions with experimental 13C labeling data. We present systematic design principles, quantitative performance comparisons, and detailed experimental protocols to enable researchers to make informed decisions when selecting tracers for metabolic flux studies.

Fundamental Principles of Tracer Selection

The Role of Tracers in Metabolic Flux Analysis

13C-MFA functions as a powerful technique for elucidating in vivo fluxes in microbial and mammalian systems by combining stable-isotope tracing with computational modeling [26] [10]. When a labeled substrate (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose) is metabolized by cells, enzymatic reactions rearrange carbon atoms, creating specific labeling patterns in downstream metabolites [10]. These patterns are measured using analytical techniques such as mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [26]. The core principle of 13C-MFA involves formulating fluxes as unknown model parameters that are estimated by minimizing the difference between measured labeling data and model-simulated labeling patterns, subject to stoichiometric constraints [10]. The tracer selection directly influences which isotopomers can form within a network and determines the sensitivity of isotopomer measurements to flux changes, thereby fundamentally constraining which fluxes can be observed and with what precision [26] [27].

EMU Framework and Rational Tracer Design

The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework provides a mathematical foundation for rational tracer design [26] [28]. This approach decomposes any metabolite in a network model into a linear combination of EMU basis vectors, where coefficients indicate the fractional contribution of each basis vector to the product metabolite [26]. The strength of this methodology lies in its decoupling of substrate labeling (EMU basis vectors) from dependence on free fluxes (coefficients) [26]. Flux observability depends fundamentally on both the number of independent EMU basis vectors and the sensitivities of coefficients with respect to free fluxes [26]. This theoretical framework establishes that the number of independent EMU basis vectors places hard limits on how many free fluxes can be determined, providing crucial guidance for selecting feasible substrate labeling [26] [28].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Rational Tracer Design

| Concept | Description | Application in Tracer Design |

|---|---|---|

| EMU Basis Vectors | Independent labeling units that contribute to product metabolite labeling | Maximizing independent vectors improves system observability [26] |

| Coefficient Sensitivities | Responsiveness of EMU coefficients to changes in free fluxes | High sensitivity enables better flux resolution [26] [28] |

| Flux Observability | The ability to determine specific fluxes from labeling data | Constrained by tracer selection and measurement set [26] |

| Precision Scoring | Quantitative metric for evaluating tracer performance | Enables systematic comparison of different tracers [29] |

Quantitative Comparison of Tracer Performance

Performance Evaluation of Glucose Tracers

Different glucose tracers yield substantially varying precision in flux estimates due to their distinct carbon labeling patterns and how these patterns propagate through metabolic networks. A systematic evaluation of 19 commercially available glucose tracers revealed that [1,2-13C]glucose provided the most precise estimates for glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and the overall network [27]. Notably, tracers such as [2-13C]glucose and [3-13C]glucose also outperformed the more commonly used [1-13C]glucose [27]. In mammalian cell systems, [2,3,4,5,6-13C]glucose has been identified as optimal for elucidating oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (oxPPP) flux, while [3,4-13C]glucose performs best for quantifying pyruvate carboxylase (PC) flux [28]. These findings demonstrate that conventional tracer choices may be suboptimal for specific metabolic pathways and highlight the importance of rational tracer design.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected Glucose Tracers in Mammalian Systems

| Tracer | OxPPP Flux Precision | PC Flux Precision | Overall Network Precision | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C]glucose | High | Medium | High | Overall network analysis, PPP studies [27] [28] |

| [1-13C]glucose | Low | Low | Low | Reference tracer, mixed with other tracers [29] |

| [U-13C]glucose | Medium | Medium | Medium | Broad coverage, standard initial approach [29] |

| [2,3,4,5,6-13C]glucose | Very High | Low | Medium | Specific oxPPP flux determination [28] |

| [3,4-13C]glucose | Low | Very High | Medium | Specific PC flux determination [28] |

Glutamine and Multi-Substrate Tracer Strategies

In mammalian systems that utilize multiple carbon sources, glutamine tracers provide complementary information to glucose tracers. [U-13C5]glutamine has been identified as the preferred isotopic tracer for analysis of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [27]. However, rational design approaches have demonstrated that 13C-glutamine tracers generally perform poorly compared to optimal glucose tracers for resolving fluxes in central carbon metabolism when lactate is the measured metabolite [28]. For parallel labeling experiments, which represent the state-of-the-art in high-resolution 13C-MFA, careful selection of complementary tracers is essential to maximize information gain [29]. Precision and synergy scoring systems have been developed to identify optimal tracer combinations, with studies showing that parallel experiments with [1,2-13C]glucose and [1,6-13C]glucose can significantly improve flux precision compared to single tracer experiments [29].

Performance Scoring Metrics

The evaluation of tracer performance requires robust quantitative metrics. The precision score (P) is calculated as the average of individual flux precision scores (pi) for n fluxes of interest:

[ P=\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n}p{i} \quad \text{with} \quad p{i}=\left(\frac{(UB{95,i}-LB{95,i}){ref}}{(UB{95,i}-LB{95,i})_{exp}}\right)^{2} ]

where UB95,i and LB95,i represent the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals for flux i [29]. This metric captures the nonlinear behavior of flux confidence intervals without bias from flux value normalization [29]. For parallel labeling experiments, a synergy score (S) quantifies the improvement from combining multiple tracers:

[ S=\frac{P{comb}-\max(P{A},P{B})}{\max(P{A},P_{B})} ]

where Pcomb is the precision score of the combined tracer experiment, and PA and PB are the precision scores of tracers A and B individually [29].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Workflow for Rational Tracer Selection

The tracer selection process should follow a systematic approach that aligns with specific research objectives and network topology. The diagram below illustrates the key decision points in designing optimal tracer experiments:

Cell Culture and Labeling Protocol

For mammalian cell studies, the following protocol provides a standardized approach for tracer experiments:

Cell Culture Preparation: Culture cells in appropriate medium (e.g., high-glucose DMEM for cancer cell lines) supplemented with serum and antibiotics [27]. Grow cells to semi-confluent density in standard culture conditions.

Tracer Medium Formulation: Prepare glucose-free base medium supplemented with the chosen 13C-labeled tracer. For [1,2-13C]glucose experiments, use a concentration of 25 mM [27]. Supplement with 4 mM glutamine (labeled or unlabeled depending on experimental design) and 10% dialyzed FBS to eliminate unlabeled carbon sources that could dilute the tracer [27] [10].

Labeling Period: Replace standard medium with tracer medium and incubate for a duration sufficient to reach isotopic steady state (typically 6 hours for rapidly metabolizing cancer cells, but up to 24 hours for primary cells) [27]. Maintain consistent environmental conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) throughout the labeling period.

Metabolite Extraction: Quench metabolism by removing medium and immediately adding ice-cold methanol [27]. Add water and chloroform (4:1:4 ratio methanol:water:chloroform) for deproteinization [27]. Vortex and hold on ice for 30 minutes, then centrifuge at 3000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C. Collect aqueous phase containing polar metabolites and evaporate under airflow at room temperature [27].

Mass Isotopomer Distribution Measurement

Chemical Derivatization: Dissolve dried polar metabolites in 60 µl of 2% methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine, sonicate for 30 minutes, and incubate at 37°C for 2 hours [27]. Add 90 µl MBTSTFA + 1% TBDMCS and incubate at 55°C for 60 minutes to form tert-butyldimethylsilyl derivatives [27].

GC-MS Analysis: Perform analysis using a GC system equipped with a 30m DB-35MS capillary column connected to a mass spectrometer operating under electron impact ionization at 70 eV [27]. Use the following temperature program: hold at 100°C for 3 minutes, increase to 300°C at 3.5°C/min [27]. Operate the MS in selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode to enhance sensitivity for specific metabolite fragments [27].

MID Calculation: Extract ion chromatograms for specific metabolite fragments and calculate mass isotopomer distributions by integrating peak areas for M+0, M+1, M+2, etc. isotopomers [27] [10]. Correct for natural abundance of 13C and other isotopes using appropriate algorithms [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for 13C Tracer Experiments

| Item | Specification | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled Glucose | Various labeling patterns ([1-13C], [1,2-13C], [U-13C], etc.) | Primary tracer substrate for central carbon metabolism | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories [27] [29] |

| 13C-labeled Glutamine | [U-13C5]glutamine, [3-13C]glutamine etc. | Tracer for TCA cycle and amino acid metabolism | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories [27] |

| Mass Spectrometer | GC-MS or LC-MS capability | Measurement of mass isotopomer distributions | Agilent, Thermo Fisher [27] |

| Metabolic Flux Software | EMU-based algorithms | Computational flux estimation | Metran, INCA [26] [10] |

| Dialyzed FBS | Low molecular weight contaminants removed | Eliminates unlabeled carbon sources that dilute tracer | Various suppliers [27] |

Advanced Tracer Strategies

Parallel Labeling Experiments

Parallel labeling experiments represent the current state-of-the-art in 13C-MFA, where multiple tracer experiments are conducted separately and data are combined for flux estimation [29]. This approach requires careful selection of complementary tracers that collectively provide more information than any single tracer alone. The synergy scoring system enables quantitative evaluation of tracer combinations, with studies demonstrating that optimal pairs such as [1,2-13C]glucose and [1,6-13C]glucose can significantly improve flux resolution compared to single tracer experiments [29]. The key advantage of parallel labeling is the ability to tailor specific isotopic tracers to different parts of metabolism, thereby overcoming inherent limitations of single tracer approaches in complex networks [29].

Isotopically Instationary MFA

Instationary 13C-MFA represents an advanced approach that utilizes repeated sampling during the transient phase of 13C labeling before isotopic steady state is reached [30]. This method can provide additional information about pool sizes and reduce experiment duration, but requires more complex computational methods to solve large systems of differential equations [30]. Optimal experimental design for instationary experiments must account for sampling timepoints, measurement selection, and the significant computational demands of the associated statistical analysis [30]. While powerful, this approach is methodologically complex and typically requires specialized expertise.

Model Selection and Validation

A critical aspect of 13C-MFA is the selection of an appropriate metabolic network model, as an incorrect model structure will yield invalid flux estimates regardless of tracer choice. Validation-based model selection approaches have been developed that use independent validation data (e.g., from distinct tracers) to select the correct model structure [21]. This method protects against both overfitting (too complex models) and underfitting (too simple models) by choosing the model that best predicts new, independent data [21]. This approach is particularly valuable as it remains robust even when measurement uncertainty estimates are inaccurate, a common challenge in MFA studies [21].

Tracer selection fundamentally constrains the information that can be extracted from 13C-MFA experiments. Rational design approaches based on EMU decomposition and precision scoring outperform traditional trial-and-error methods by systematically identifying tracers that maximize information content for specific fluxes or pathways. For mammalian systems, [1,2-13C]glucose emerges as the optimal single tracer for overall network analysis, while specialized tracers like [2,3,4,5,6-13C]glucose and [3,4-13C]glucose provide superior resolution for specific pathways. Parallel labeling experiments with complementary tracers currently represent the gold standard, offering enhanced flux precision through synergistic information gain. As 13C-MFA continues to evolve as a core technology in metabolic engineering and biomedical research, rational tracer design will play an increasingly critical role in validating constraint-based model predictions and elucidating metabolic phenotypes in health and disease.

Analytical Methods and Integration Approaches for 13C Data

Mass Spectrometry Platforms for 13C Isotopologue Measurement

13C-metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) serves as the empirical cornerstone for validating predictions generated by constraint-based metabolic models. These genome-scale models often rely on optimization principles, such as growth rate maximization used in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), producing solution spaces that require experimental validation [2] [5]. 13C-labeling data provides powerful, system-level constraints that directly map how carbon flows through metabolic networks, offering a rigorous benchmark for model predictions [2] [9]. The measurement of 13C isotopologues—molecules of the same metabolite that differ in the number of 13C atoms—is technically challenging, and the choice of mass spectrometry platform profoundly impacts data quality, influencing the reliability of the resulting flux constraints [31] [32]. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading mass spectrometry platforms, providing the experimental data necessary for selecting the optimal technology to bridge computational modeling and empirical measurement.

Key Mass Spectrometry Platforms and Technologies

The accurate measurement of 13C-isotopologue distributions requires sophisticated separation and detection strategies. The following platforms represent the most common and effective technologies employed in modern fluxomics studies.

Chromatographic Separation Techniques

- Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC): This technique is increasingly favored for 13C-MFA as it enables the direct, simultaneous separation of polar central carbon metabolites without prior derivatization. HILIC exhibits wide compatibility with electrospray ionization (ESI), making it ideal for LC-MS analysis of key intermediates from glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and amino acid biosynthesis [32].

- Gas Chromatography (GC): Often coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS), this method requires chemical derivatization (e.g., forming TMS-derivatives) to make metabolites volatile. While this can introduce isotopic backgrounds and multiple chromatographic peaks, it remains a routine and robust method for analyzing organic and amino acids [31] [32].

Mass Analyzer Platforms

- Triple Quadrupole (QQQ) Mass Spectrometry: Operated in Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) or Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) modes, QQQ systems offer exceptional sensitivity and specificity for targeted quantification. However, they are limited by unit mass resolution [32].

- Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (QTOF) High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS): QTOF instruments provide excellent mass accuracies (up to ±5 ppm) and high resolution, enabling interference-free measurement of the full isotopologue space in complex sample matrices [32].

- Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI)-MS Imaging (MSI): This specialized technique combines MS with spatial information, mapping the distributions of metabolites and their isotopologues directly in tissue sections. This is powerful for investigating metabolic heterogeneity, such as in plant embryos [33].

Table 1: Core Performance Comparison of QQQ and QTOF Platforms for 13C-Metabolomics [32]

| Performance Metric | LC-QQQ (MRM/SIM) | LC-QTOF (High-Res MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Linear Dynamic Range | 3-5 orders of magnitude | 3-5 orders of magnitude |

| Average Lower Linearity Limit | 10-50 nM (most metabolites) | Generally higher than QQQ |

| In-Column Detection Limits | 6.8 – 304.7 fmol | 28.7 – 881.5 fmol |

| Spectral Accuracy (Dev. from Theory) | 4.01 ± 3.01% | 3.89 ± 3.54% |

| Key Advantage | Superior sensitivity & precision for quantification | Full isotopologue coverage without mass interferences |

| Principal Limitation | Unit mass resolution; cannot resolve all interferences | Lower sensitivity compared to QQQ-MRM |

Quantitative Comparison of Platform Performance

Sensitivity and Linearity

In a systematic comparative study of 17 central carbon metabolites in Corynebacterium glutamicum extracts, QQQ-MS/MS demonstrated superior sensitivity. Its lower detection limits (6.8–304.7 fmol) and broader linearity at low concentrations make it the platform of choice for absolute quantification of low-abundance metabolites [32]. While QTOF-HRMS also showed wide linearity (3-5 orders of magnitude), its lower sensitivity resulted in higher detection limits for most compounds analyzed [32]. The quantitative precision of QQQ, particularly in MRM mode, was also found to be higher, with relative deviations for internal standards below 5% compared to below 10% for QTOF [32].

Spectral Accuracy and Isotopologue Measurement

Spectral accuracy—the precision in measuring an analyte's natural isotopic distribution—is paramount for reliable 13C-flux determination. Both QQQ and QTOF platforms demonstrated competent performance, with QQQ showing a mean deviation of 4.01 ± 3.01% and QTOF 3.89 ± 3.54% from theoretical values in non-labeled extracts [32]. The critical distinction emerges in complex matrices: QTOF-HRMS ensures determination of the full isotopologue space without mass interferences, a capability that is intrinsically limited in unit-mass-resolution QQQ instruments [32]. This makes QTOF essential for experiments where isobaric overlaps are likely.

Experimental Protocols for 13C-Isotopologue Analysis

A Standard Workflow for LC-MS Based 13C-MFA

The following protocol, adapted from HILIC-enabled metabolomics strategies [32], outlines a robust pipeline for generating high-quality isotopologue data suitable for model validation.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for 13C-isotopologue analysis.

Step 1: Cell Culture and 13C-Labeling.