Validating Genome-Scale Metabolic Models: A Robust Framework Using 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

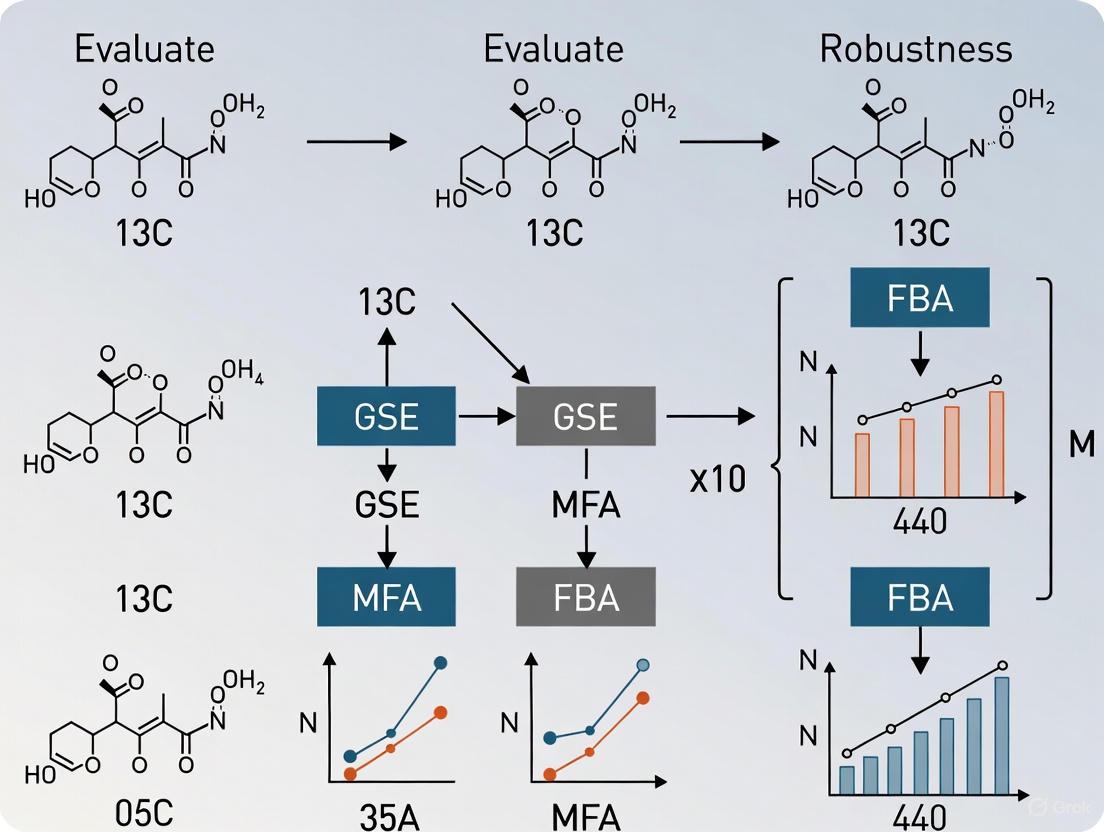

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the robustness of Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GSMM) reconstructions using 13C labeling data.

Validating Genome-Scale Metabolic Models: A Robust Framework Using 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the robustness of Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GSMM) reconstructions using 13C labeling data. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of integrating experimental 13C data with constraint-based modeling to move beyond purely theoretical predictions. The scope covers methodological advances that enable genome-scale flux constraint, systematic troubleshooting for model refinement, and rigorous validation techniques against gene essentiality and physiological data. By synthesizing these areas, this resource offers practical guidance for enhancing model predictive accuracy, with direct implications for identifying metabolic vulnerabilities and antibacterial targets in biomedical research.

The Foundation of Robust GSMMs: Principles of 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

In the fields of metabolic engineering, biomedical research, and drug development, accurately quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes is crucial for understanding cell physiology, identifying metabolic bottlenecks in production strains, and unraveling the metabolic reprogramming associated with diseases like cancer and metabolic syndromes [1]. Among the most powerful techniques for elucidating these metabolic fluxes is 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C MFA), which utilizes stable isotopic tracers, most commonly 13C-labeled nutrients, to trace the flow of carbon through metabolic networks [1] [2]. When cells metabolize these labeled substrates, the resulting distribution of heavy isotopes in intracellular metabolites provides a rich source of information about the relative activities of different metabolic pathways [1].

The interpretation of these labeling experiments relies on two fundamental computational concepts: the Mass Isotopomer Distribution Vector (MDV), which quantifies the labeling patterns, and the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework, a decompositional modeling approach that enables efficient simulation of these patterns [3] [4]. This guide explores the core concepts of MDVs and EMU decomposition, objectively comparing their performance against traditional methodologies and situating their importance within the broader thesis of evaluating the robustness of genome-scale model reconstruction constrained by 13C labeling data.

Core Concept 1: Mass Isotopomer Distribution Vectors (MDVs)

Definition and Composition

A Mass Isotopomer Distribution Vector (MDV), also referred to as a mass isotopomer distribution (MID), is a quantitative representation of the relative abundances of the different isotopologues of a metabolite [1]. An isotopologue is a variant of a molecule that differs only in its isotopic composition (e.g., 12C vs. 13C). For a metabolite containing n carbon atoms, there can be n+1 possible isotopologues, ranging from M+0 (all carbons are 12C) to M+n (all carbons are 13C).

The MDV is a vector that lists the fractional abundance of each of these isotopologues, normalized such that the sum of all fractions equals 1 or 100% [1]. The following Dot script visualizes the relationship between a metabolite's structure, its possible isotopologues, and its resulting MDV:

Measurement and Data Correction

MDVs are typically measured using Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy [5] [4]. In GC-MS, a common platform, metabolites are often chemically derivatized to improve chromatographic separation, which adds atoms from the derivatization agent to the original metabolite [1]. A critical step in data processing is the correction for naturally occurring isotopes (e.g., 13C at 1.07% natural abundance, 2H, 17O, 18O) in both the metabolite and the derivatization agent. Without this correction, the MDVs of chemically related metabolites (like glutamate and α-ketoglutarate) will not match, even though they share the same carbon backbone, due to differences in their other constituent atoms [1]. The general correction is performed using a matrix equation that relates the measured ion intensities (I) to the true, corrected MDV (M) [1].

Core Concept 2: The EMU Decomposition Framework

The Computational Challenge in 13C MFA

The ultimate goal of 13C MFA is to find the metabolic flux distribution that best explains the experimentally measured MDVs. This requires repeatedly simulating MDVs for candidate flux distributions in an iterative optimization process [3] [4]. The traditional modeling frameworks for this simulation are based on isotopomers (isomers differing only in the isotopic identity of their atoms) or cumomers (cumulative isotopomers). A fundamental limitation of these frameworks is their combinatorial explosion. For a metabolite with N atoms, there are 2^N possible isotopomers. When multiple isotopic tracers (e.g., 13C, 2H, 18O) are used, this number becomes astronomically large, making the simulation computationally prohibitive for large networks [3] [4]. For instance, modeling gluconeogenesis with 2H, 13C, and 18O tracers can generate over 2 million isotopomers.

EMU Framework as a Solution

The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework is a novel bottom-up modeling approach that dramatically reduces the computational complexity of simulating isotopic labeling without any loss of information [3] [4]. An EMU is defined as a distinct subset of a metabolite's atoms. The framework uses a decomposition algorithm that identifies the minimal set of EMUs required to simulate the MDVs of the measured metabolites. Instead of tracking all possible isotopomers, the EMU framework only tracks the labeling states of these specific, relevant subsets, which are determined by the atom transitions in the network's biochemical reactions [3].

The following diagram and table illustrate the core concept of an EMU and the dramatic efficiency improvement it offers.

Table 1: Comparison of EMUs and Isotopomers for a Three-Atom Metabolite

| Aspect | Elementary Metabolite Units (EMUs) | Isotopomers |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A moiety comprising any distinct subset of the metabolite's atoms. | Isomers that differ only in the isotopic identity of their individual atoms. |

| Basis | Defined by the needs of the simulation; a bottom-up approach. | Encompasses all possible labeling states; a top-down approach. |

| Number of Variables | 2^N - 1 (7 for a 3-atom metabolite: A1, A2, A3, A12, A13, A23, A123). | 2^N (8 for a 3-atom metabolite). |

| Example for Glucose (C6H12O6) | A typical 13C-labeling system requires 100s of EMUs. | 64 carbon isotopomers. With multiple tracers (13C, 2H), this can exceed 2.6 x 10^5. |

| Computational Efficiency | Highly efficient; reduces the number of equations by an order of magnitude. | Computationally prohibitive for large networks or multiple tracers. |

EMU Reactions and Simulation

The EMU framework operates by defining EMU reactions, which describe how EMUs are transformed by biochemical reactions. The mass isotopomer distribution of a product EMU is determined by the MIDs of the precursor EMUs. For example:

- In a condensation reaction where C is formed from A and B, the MID of EMU C~123~ is calculated from the convolution (Cauchy product) of the MIDs of EMU A~12~ and EMU B~1~: C~123~ = A~12~ × B~1~ [3].

- In a cleavage or unimolecular reaction, the MID of the product EMU is identical to the MID of the substrate EMU [3].

By setting up balance equations for all necessary EMUs, the framework generates a system of equations that is vastly smaller than the isotopomer system but yields identical MDV simulations [3] [4].

Comparative Analysis: EMU Framework vs. Traditional Methods

The transition from isotopomer-based models to the EMU framework represents a significant advancement in the technical capabilities of 13C MFA. The following table provides a structured, objective comparison of their performance.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Isotopomer vs. EMU Modeling Frameworks

| Performance Metric | Isotopomer/Cumomer Framework | EMU Framework | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Scalability | Poor; number of variables scales exponentially with network size and tracer number. | Excellent; number of variables is reduced by ~1 order of magnitude for a typical 13C system [3]. | A study of gluconeogenesis with 2H, 13C, 18O required only 354 EMUs vs. >2 million isotopomers [3] [4]. |

| Support for Multiple Tracers | Limited; computationally prohibitive, confining most studies to single tracers. | Highly efficient; specifically designed to leverage the power of multiple isotopic tracers. | The EMU framework is "most efficient for the analysis of labeling by multiple isotopic tracers" [3]. |

| Flux Resolution in Large Models | Restricted to small, core metabolic models (typically <100 reactions), potentially introducing bias. | Enables flux elucidation in genome-scale models, uncovering alternate pathways. | 13C MFA with a genome-scale model of E. coli (697 reactions) revealed wider, more realistic flux ranges for key reactions compared to a core model [6]. |

| Implementation & Adoption | Historically widespread but limited by complexity. Implemented in older MFA software. | Increasingly the standard in modern MFA software due to its efficiency. | The open-source Python package mfapy provides flexibility for 13C-MFA and supports the EMU framework [7]. |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

A Standard Workflow for 13C MFA Using MDVs and EMU

The application of MDVs and EMU decomposition follows a structured experimental and computational protocol. The following Dot script visualizes this integrated workflow.

Key Protocol Details

- Achieving Isotopic Steady State: For reliable 13C tracer analysis, the biological system should ideally be at a metabolic pseudo-steady state, and the labeling should be allowed to proceed until an isotopic steady state is reached, where the 13C enrichment in metabolites is stable over time. The time to reach this state varies; glycolytic intermediates reach it in minutes, while TCA cycle intermediates can take hours. Special attention is needed for metabolites like amino acids that may exchange with unlabeled pools in the culture medium, potentially preventing them from ever reaching an isotopic steady state [1].

- Model Selection and Flux Estimation: The choice between a core metabolic model and a genome-scale model has significant implications. While core models are computationally simpler, 13C MFA at a genome-scale avoids pre-judgment about active pathways and provides a more comprehensive view. Fluxes are estimated by solving a non-linear least-squares optimization problem, where the difference between the simulated MDVs (using the EMU framework) and the experimentally measured MDVs is minimized [7] [6]. The statistical significance of the estimated flux distribution is then evaluated, and confidence intervals for each flux are determined [6] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for 13C MFA

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | To introduce a traceable pattern into metabolism. | [U-13C]-Glucose, [1-13C]-Glucose; purity is critical for accurate interpretation. |

| Quenching Solution | To rapidly halt all metabolic activity at the time of sampling. | Cold methanol or buffered organic solutions; protocol depends on cell type. |

| Derivatization Reagents | To chemically modify metabolites for volatility and separation in GC-MS. | MSTFA (N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide) for silylation. |

| GC-MS Instrument | To separate metabolites and measure their mass isotopomer distributions. | A core analytical platform for generating high-quality MDV data. |

| NMR Spectrometer | An alternative platform that can provide positional labeling information. | Used for method validation or specific applications where positional insight is key [5]. |

| EMU-Based Software | To simulate MDVs and perform flux estimation. | mfapy (open-source Python package) [7], other commercial and academic MFA software. |

| Atom Mapping Database | To provide the carbon transition data for building the metabolic network model. | MetRxn, KEGG, MetaCyc; essential for constructing the EMU model [6]. |

| Genome-Scale Model | A comprehensive stoichiometric representation of an organism's metabolism. | iAF1260 for E. coli; used as a basis for large-scale 13C MFA [6]. |

Within the context of evaluating the robustness of genome-scale metabolic model reconstructions, the combination of experimentally measured MDVs and the computationally efficient EMU framework provides a powerful tool for validation and refinement. Unlike constraint-based methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which often rely on assumed evolutionary objectives like growth rate optimization, 13C MFA is a descriptive method that directly infers fluxes from experimental data [2]. The comparison of measured and simulated labeling patterns serves as a strong validation metric; a poor fit indicates missing or incorrect network assumptions [2].

Studies have demonstrated that applying 13C MFA at a genome-scale can reveal wider flux confidence intervals for key reactions compared to core models, as the larger network introduces alternative, feasible routes such as gluconeogenesis or arginine degradation bypasses [6]. This suggests that flux solutions thought to be unique in core models may be part of a larger solution space in genome-scale models. Furthermore, the EMU framework makes it computationally feasible to incorporate this comprehensive network detail, thereby enabling a more rigorous and unbiased test of a genome-scale model's ability to recapitulate real, measured phenotypic data. This process is crucial for identifying gaps in network reconstructions and building more accurate, predictive models for metabolic engineering and drug development.

In the field of systems biology, accurately determining intracellular metabolic fluxes—the rates at which metabolites traverse biochemical pathways—is crucial for understanding how a cell's behavior emerges from its molecular components [2] [9]. Metabolic fluxes represent the functional phenotype of metabolic networks, mapping how carbon and electrons flow through metabolism to enable essential cell functions such as energy production, biosynthesis, and growth [2]. While various computational methods have been developed to estimate these fluxes, 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as the gold standard technique for quantifying in vivo metabolic pathway activity [10] [11]. Unlike other approaches that rely on theoretical optimization principles, 13C-MFA provides direct empirical constraints on intracellular fluxes by tracing the fate of individual carbon atoms through metabolic networks [2]. This review examines why 13C labeling data provides unmatched constraints for metabolic flux analysis, particularly in the context of genome-scale model reconstruction and validation, offering cancer biologists, metabolic engineers, and pharmaceutical researchers an objective comparison of its capabilities against alternative methodologies.

Fundamental Principles of 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

Core Mechanism and Theoretical Foundation

13C-MFA operates on a fundamental principle: when cells are cultivated with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose with carbon atoms replaced by the heavier 13C isotope), the ensuing labeling patterns found in intracellular metabolites directly reflect the activities of metabolic pathways that produced them [2] [9]. The labeling pattern, expressed as a Mass Distribution Vector (MDV) or Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID), quantifies the fractions of metabolite molecules with 0, 1, 2, ... n 13C atoms incorporated [2] [1]. Since these patterns are highly dependent on the flux profile, it becomes possible to computationally infer the fluxes that best explain the observed labeling data [2].

The technique is fundamentally a nonlinear fitting problem where fluxes are parameters estimated by minimizing the difference between measured labeling patterns and those simulated by a model, subject to stoichiometric constraints resulting from mass balances for intracellular metabolites [2] [11]. This process can be formalized as an optimization problem where the algorithm adjusts flux values (v) until the simulated isotopic labeling states (X) match the experimental measurements (xM), while satisfying the system of equations determined by metabolic reaction topology and atomic transfer relationships [10].

Comparison with Alternative Flux Determination Methods

To appreciate why 13C labeling provides superior constraints, it's essential to compare it with other prevalent flux analysis methods:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Metabolic Flux Analysis Techniques

| Method | Principle | Network Scope | Constraints Used | Key Assumptions | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) | Flux calculation using stoichiometric model & extracellular flux measurements [2] | Central metabolism [2] | Measured extracellular fluxes [2] | No metabolite accumulation (steady state) [2] | System often underdetermined; limited to central metabolism [2] |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Optimization-based flux calculation using genome-scale stoichiometric model [2] [9] | Genome-scale [2] [9] | Stoichiometry, optimization objective (e.g., growth maximization) [2] | Evolution has optimized network for specific objective [2] | Relies on hypothetical optimization principles; produces solution for almost any input [2] |

| 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) | Computational inference from 13C labeling patterns of intracellular metabolites [2] [10] | Typically central carbon metabolism [2] | 13C labeling patterns, extracellular fluxes, stoichiometry [2] | Metabolic and isotopic steady state [1] [10] | Experimentally intensive; computationally complex [10] |

| Genome-scale 13C-MFA | Incorporates 13C labeling data with genome-scale models [2] | Genome-scale [2] | 13C labeling patterns, stoichiometry, flux directionality [2] | Flux flows from core to peripheral metabolism without backflow [2] | Emerging methodology; computational challenges for large networks [2] |

Why 13C Labeling Data Provides Unmatched Constraints

Direct Empirical Constraints vs. Theoretical Assumptions

The primary advantage of 13C labeling data lies in its ability to provide direct empirical constraints on intracellular fluxes, eliminating the need to assume an evolutionary optimization principle such as the growth rate optimization typically used in FBA [2] [9]. While FBA determines fluxes through linear programming by assuming metabolism is evolutionarily tuned to maximize growth rate, this assumption has been questioned—particularly for engineered strains not under long-term evolutionary pressure [2]. In contrast, 13C-MFA is a descriptive method that determines metabolic fluxes compatible with accrued experimental data without postulating general principles for predicting unperformed experiments [2].

Furthermore, the comparison of measured and fitted labeling patterns provides a degree of validation and falsifiability that FBA does not possess: an inadequate fit to experimental data indicates that the underlying model assumptions are incorrect. In contrast, FBA produces a solution for almost any input, making model validation challenging [2].

Enhanced Robustness to Model Reconstruction Errors

Research demonstrates that methods incorporating 13C labeling data are significantly more robust than FBA with respect to errors in genome-scale model reconstruction [2] [9]. This enhanced robustness stems from the additional layer of validation provided by isotopic labeling measurements. When 13C labeling data is incorporated into genome-scale models, the effective constraining is achieved by making the simple but biologically relevant assumption that flux flows from core to peripheral metabolism and does not flow back [2]. This approach provides a comprehensive picture of metabolite balancing and predictions for unmeasured extracellular fluxes while being constrained by empirical labeling data [2].

Unraveling Metabolic Network Complexity

13C labeling enables researchers to resolve parallel pathway activities and reversible reactions that are impossible to distinguish using only extracellular flux measurements [1] [11]. For example, feeding labeled glucose results in M+3 triose phosphates, where M+3 fructose bisphosphate reflects the reversibility of aldolase, while M+3 glucose-6-phosphate reflects fructose bisphosphatase activity [10]. This level of mechanistic insight is uniquely provided by 13C labeling patterns.

Experimental Design and Methodological Framework

Core Experimental Workflow

Implementing 13C-MFA requires careful experimental design and execution. The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a 13C-MFA experiment:

Key Methodological Components

Tracer Selection and Experimental Conditions

Selecting appropriate 13C-labeled tracers is crucial for targeting specific metabolic pathways. Different tracers illuminate different pathway activities—for example, [1,2-13C]glucose produces distinct labeling patterns that can reveal fluxes through glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, or TCA cycle [11]. The experiment must continue until isotopic steady state is reached, where the 13C enrichment in metabolites is stable over time. This timing varies significantly across metabolites—glycolytic intermediates may reach steady state within minutes, while TCA cycle intermediates can take several hours [1].

Analytical Techniques for Measuring Labeling Patterns

Mass spectrometry techniques (GC-MS or LC-MS) are most commonly used to measure mass isotopomer distributions due to their high sensitivity and throughput [10] [11]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides an alternative that can resolve positional isotopomer information but generally with lower sensitivity [1]. The measured data must be corrected for naturally occurring isotopes (e.g., 13C at 1.07% natural abundance) and, when applicable, derivatization agents added for chromatographic separation [1].

Computational Flux Estimation

The core of 13C-MFA involves estimating fluxes by minimizing the difference between measured and simulated labeling patterns. The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework has been instrumental in making these computations tractable by allowing efficient simulation of isotopic labeling in arbitrary biochemical networks [10] [11]. This framework has been incorporated into user-friendly software tools such as Metran and INCA, making 13C-MFA accessible to researchers without extensive computational backgrounds [11].

Advanced Applications: Integrating 13C Constraints with Genome-Scale Models

The Frontier of Metabolic Analysis

A significant advancement in the field is the integration of 13C labeling data with genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). Traditional 13C-MFA has been limited to central carbon metabolism, but new methods now enable the incorporation of 13C labeling constraints into genome-scale models [2] [9]. This integration provides flux estimates for peripheral metabolism while maintaining the accuracy of traditional 13C-MFA for central carbon metabolism [2]. The extra validation gained by matching numerous relative labeling measurements (e.g., 48 in the referenced study) helps identify where and why existing constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) flux prediction algorithms fail [2].

Enzyme-Constrained Models and Proteomic Integration

Recent developments such as the GECKO (Enhancement of GEMs with Enzymatic Constraints using Kinetic and Omics data) toolbox further expand modeling capabilities by incorporating enzyme constraints and proteomics data into genome-scale models [12]. This approach extends classical FBA by detailing enzyme demands for metabolic reactions, accounting for isoenzymes, promiscuous enzymes, and enzymatic complexes [12]. When combined with 13C labeling constraints, these models provide unprecedented resolution in mapping metabolic capabilities and limitations.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Implementing 13C-MFA requires specific reagents and computational resources. The following table catalogues essential solutions for researchers establishing 13C flux analysis capabilities:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | [U-13C] Glucose, [1-13C] Glucose, [1,2-13C] Glucose, 13C Glutamine [11] [13] | Reveal fluxes through specific pathways | Selection depends on pathways of interest; purity critical for accurate interpretation |

| Mass Spectrometry | GC-MS, LC-MS systems, Derivatization reagents (e.g., TBDMS, MSTFA) [1] [10] | Measure mass isotopomer distributions in intracellular metabolites | LC-MS preferred for underivatized metabolites; GC-MS offers higher sensitivity for certain classes |

| Cell Culture Systems | Bioreactors, Chemostat systems, Nutrient-controlled systems [1] [14] | Maintain metabolic and isotopic steady state | Chemostats ideal for steady-state; perfusion systems approximate for adherent cells |

| Computational Tools | INCA, Metran, GECKO toolbox, COBRA Toolbox [10] [11] [12] | Flux estimation, model simulation, data integration | INCA and Metran specialize in 13C-MFA; GECKO integrates enzyme constraints |

| Metabolic Models | Organism-specific genome-scale models (e.g., iJO1366 for E. coli, Yeast8 for S. cerevisiae) [14] [12] | Provide stoichiometric framework for flux estimation | Quality of reconstruction significantly impacts flux resolution |

13C labeling data remains the gold standard for constraining metabolic fluxes due to its unique ability to provide direct empirical validation of intracellular pathway activities. While methodologically more demanding than purely computational approaches, its capacity to discriminate between alternative flux states, validate model predictions, and reveal network properties in unbiased fashion makes it indispensable for rigorous metabolic analysis. Emerging methodologies that integrate 13C labeling constraints with genome-scale models and enzyme kinetics promise to further expand our ability to map and engineer metabolic networks across diverse biological systems, from microbial factories to human diseases. For researchers requiring the highest confidence in flux determination, particularly in pharmaceutical development and metabolic engineering, investment in 13C metabolic flux analysis provides returns in mechanistic insight and predictive capability that alternative methods cannot match.

Limitations of Traditional FBA and the Need for Experimental Validation

Constraint-based metabolic models, particularly those analyzed using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), have become indispensable tools in systems biology and metabolic engineering. These models enable researchers to predict cellular behavior by leveraging genomic information and biochemical constraints [15]. FBA operates on the foundational assumption that metabolic networks reach a steady state and have evolved to optimize specific biological objectives, most commonly biomass production or growth rate [16]. This optimization-based approach has successfully guided metabolic engineering efforts, including the industrial-scale production of chemicals such as 1,4-butanediol [9] [2].

However, the predictive power and biological relevance of traditional FBA are constrained by inherent methodological limitations. These limitations primarily stem from the steady-state assumption, the reliance on evolutionary optimization principles that may not apply in engineered strains or disease states, and the models' inherent underdetermination due to the scarcity of experimental data relative to the vast number of network reactions [15] [16] [2]. This article examines these critical limitations and demonstrates how experimental validation, particularly through 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), addresses these shortcomings and enhances the robustness of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions.

Key Limitations of Traditional Flux Balance Analysis

Traditional FBA suffers from several conceptual and practical weaknesses that affect the reliability and accuracy of its flux predictions. The table below summarizes these core limitations and their implications for predictive fidelity.

Table 1: Core Limitations of Traditional Flux Balance Analysis

| Limitation | Description | Impact on Predictions |

|---|---|---|

| Steady-State Assumption [16] | Assumes constant metabolite concentrations and reaction rates, an idealization rarely true in biological systems. | Models imperfect representations of dynamic, heterogeneous cell populations; fails to capture metabolic transitions. |

| Optimal Growth Assumption [9] [2] | Assumes metabolism is evolutionarily tuned to maximize growth rate, a principle questioned for engineered strains. | Leads to inaccurate flux predictions in industrial or non-native conditions where optimality principles do not hold. |

| Underdetermination [15] [9] | Genome-scale models have hundreds of degrees of freedom but are constrained by far fewer experimental measurements. | Multiple flux maps explain available data equally well, reducing confidence in any single prediction. |

| Lack of Built-in Validation [2] | FBA produces a solution for almost any input, with no inherent mechanism to validate model assumptions against independent data. | Difficult to falsify model assumptions or identify incorrect network structures and constraints. |

| Neglects Cellular Heterogeneity [16] | Treats a culture as a population of identical, optimized cells, ignoring innate heterogeneity in metabolic states. | Predictions may not align with experimental flux measurements, which are averages over heterogeneous cell populations. |

Experimental Validation with 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

The Gold Standard for Flux Estimation

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is widely regarded as the most authoritative method for experimentally determining intracellular metabolic fluxes [9] [2]. Unlike FBA, 13C-MFA is a descriptive methodology that infers fluxes from empirical data rather than relying on optimality assumptions. The core process involves:

- Feeding cells with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose with carbon-13 atoms at specific positions).

- Measuring the resulting labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites using mass spectrometry or NMR.

- Computationally identifying the flux map that best explains the observed isotopic labeling distribution [15] [17].

A key strength of 13C-MFA is that the comparison between measured and model-predicted labeling patterns provides a powerful means of model validation. A poor fit indicates that the underlying metabolic network model or its constraints are incorrect, offering a clear path for model refinement [2]. This built-in falsifiability is a critical advantage over FBA.

Protocol: 13C-MFA for Central Carbon Metabolism

The following workflow details a standard protocol for constraining a core metabolic model using 13C labeling data.

Diagram 1: 13C-MFA workflow for a core model.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Experimental Setup and Labeling: Grow the organism (e.g., E. coli) in a controlled bioreactor with a minimal medium where the primary carbon source (e.g., glucose) is replaced with a specifically 13C-labeled version (e.g., [1-13C] glucose or [U-13C] glucose). Ensure metabolic and isotopic steady-state is reached before sampling [17] [2].

Metabolite Sampling and Measurement:

- Rapidly harvest cells and quench metabolism to preserve isotopic labeling patterns.

- Extract intracellular metabolites.

- Use Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS) to measure the Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) of key metabolite fragments, typically from amino acids that reflect the labeling of central metabolic precursors [17].

Computational Flux Estimation:

- Define a stoichiometric model of core central metabolism (e.g., 75 reactions covering glycolysis, TCA cycle, pentose phosphate pathway).

- Use computational algorithms, such as the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework, to simulate the MID of measured metabolites for a given flux map.

- Perform nonlinear least-squares optimization to find the flux map that minimizes the residual difference between the simulated and experimentally measured MIDs [17] [2].

Scaling to Genome-Scale Models

A significant advancement in the field is the development of methods to integrate 13C labeling data directly with Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs). This approach, exemplified by García Martín et al. (2015), uses the rich information from 13C labeling experiments (e.g., 48 relative labeling measurements) to constrain fluxes in a comprehensive model without relying on growth optimization assumptions [9] [2]. The key innovation is the biologically relevant assumption that flux flows from core to peripheral metabolism and does not flow back, which effectively constrains the solution space.

Table 2: Comparison of 13C-MFA Applied to Core vs. Genome-Scale Models

| Aspect | Core Metabolic Model 13C-MFA | Genome-Scale Model with 13C Data |

|---|---|---|

| Model Scope | ~75 reactions, primarily central carbon metabolism [17] | ~700 reactions, encompassing core and peripheral metabolism [9] [17] |

| Flux Resolution | Provides precise fluxes for central metabolism but no information on peripheral pathways. | Provides flux estimates for both central and peripheral metabolism, offering a system-wide view [9]. |

| Impact of Scaling Up | Highly precise flux estimates for key pathways like glycolysis and TCA cycle. | Flux confidence intervals for central reactions can widen (e.g., glycolysis range may double) due to newly possible alternative routes [17]. |

| Key Advantage | Considered the gold standard for descriptive flux measurement in central metabolism. | Does not require optimal growth assumption; provides validation via labeling data fit and falsifiability [2]. |

Comparative Performance: FBA vs. Experimentally Validated Methods

Quantitative Accuracy of Flux Predictions

The integration of 13C data fundamentally changes the nature of flux prediction. A comparative study showed that FBA and a 13C-constrained genome-scale method produced similar flux results for central carbon metabolism. However, the 13C-based method provided several critical advantages [9]:

- It identified inconsistencies in COBRA (COnstraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) flux prediction algorithms, pinpointing where and why they fail.

- It offered predictions for unmeasured extracellular fluxes.

- It was significantly more robust than FBA with respect to errors in genome-scale model reconstruction.

Furthermore, alternative robust formulations like Robust Analysis of Metabolic Pathways (RAMP), which relax the strict steady-state assumption, have been shown to significantly outperform traditional FBA when benchmarked against experimentally determined fluxes [16].

Robustness and Essentiality Predictions

Another critical metric for model performance is the accurate prediction of gene essentiality. The table below compares the performance of FBA and a robust method (RAMP) on this task, demonstrating how acknowledging uncertainty can improve predictive power.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of FBA and RAMP in Predicting Gene Essentiality and Fluxes

| Validation Metric | Traditional FBA | RAMP (Robust Method) | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction of Essential Genes [16] | Demonstrates high accuracy in identifying essential genes in E. coli models. | Performance rivals FBA, with predominantly stable predictions as biomass coefficients are varied. | Robust methods maintain FBA's predictive success for gene essentiality while incorporating uncertainty. |

| Consistency with Experimental Fluxes [16] | Shows consistency with experimental flux data. | Significantly outperforms FBA for both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. | Accounting for heterogeneity and uncertainty leads to flux predictions that are more aligned with real-world measurements. |

| Tolerance to Uncertainty [16] | Single solution, potentially over-optimized and sensitive to parameter variation. | Can identify the biologically tolerable diversity of a metabolic network; individual biomass coefficients can accommodate wide-ranging uncertainty (0.42% to >100%). | Highlights the inherent flexibility of metabolic networks and the risk of over-interpreting a single FBA solution. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful experimental validation of metabolic models relies on a specific set of reagents and computational tools.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Tools for 13C-Based Flux Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Carbon sources with specific 13C labeling patterns used to trace metabolic flux. | [1-13C] glucose to resolve glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway fluxes [17] [2]. |

| GC-MS / LC-MS Instrumentation | Analytical platforms to measure the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of intracellular metabolites. | Quantifying the labeling in proteinogenic amino acids to infer fluxes in central carbon metabolism [17]. |

| Stoichiometric Model | A computational representation of the metabolic network, including reactions, metabolites, and carbon atom mappings. | A core model of E. coli central metabolism or a genome-scale model like iAF1260 [9] [17]. |

| EMU Modeling Algorithm | A decomposition method that reduces the computational complexity of simulating 13C labeling patterns. | Efficiently calculating the MID of measured metabolites from a given network and flux map for optimization [17]. |

| Nonlinear Optimization Solver | Software to find the flux values that minimize the difference between simulated and measured MIDs. | Estimating the most likely flux map and associated confidence intervals [15] [2]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | A software suite for performing constraint-based modeling, including FBA. | Implementing FBA and related algorithms on genome-scale models for comparison with 13C-MFA results [15]. |

Traditional FBA provides a powerful but inherently limited framework for predicting metabolic behavior. Its reliance on steady-state and optimality assumptions, coupled with its underdetermined nature and lack of built-in validation, undermines the robustness of its predictions. Experimental validation, particularly using 13C metabolic flux analysis, is not merely a complementary technique but a necessary step to ground truth genome-scale models. The integration of 13C labeling data directly into genome-scale analyses, along with the development of robust modeling frameworks like RAMP, provides a more reliable, falsifiable, and comprehensive path toward accurate quantification of metabolic function. This evolution from purely theoretical optimization to experimentally grounded validation is crucial for enhancing the predictive power of metabolic models in both biotechnology and biomedical research.

Constraining Genome-Scale Models: Methodological Advances and Practical Applications

The accurate prediction of intracellular metabolic fluxes is crucial for advancing metabolic engineering, enabling the production of valuable chemicals, biofuels, and pharmaceuticals [2]. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) provide a comprehensive computational representation of an organism's metabolism, detailing gene-protein-reaction associations for all metabolic genes [18]. However, a significant limitation of standard constraint-based approaches like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is their reliance on assumed evolutionary optimization principles, such as growth rate maximization, which may not hold true for engineered strains under laboratory conditions [2] [19].

The integration of 13C labeling data with GEMs has emerged as a powerful approach to overcome this limitation, providing empirical constraints that ground metabolic flux predictions in experimental measurement rather than theoretical assumptions. This integration represents a significant advancement in the field of metabolic modeling, bridging the gap between the comprehensive network coverage of GEMs and the strong flux constraints provided by 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C MFA) [2] [17]. This guide objectively compares the primary methodological frameworks for this integration, examining their underlying principles, implementation requirements, and performance characteristics within the context of evaluating genome-scale model reconstruction robustness.

Comparative Analysis of Integration Methods

The table below summarizes the core computational methodologies for incorporating 13C data into genome-scale metabolic models, highlighting their fundamental characteristics and applications.

Table 1: Core Methodologies for Integrating 13C Data with Genome-Scale Models

| Method | Core Principle | Data Requirements | Computational Approach | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Scale 13C MFA (2S-13C MFA) [20] | Uses 13C data to constrain genome-scale fluxes without requiring every carbon transition | Isotope labeling data, Genome-scale model | Nonlinear fitting, Flux balance analysis | Metabolic engineering of S. cerevisiae, Predictions of reaction knockout effects |

| Parallel Instationary 13C Fluxomics [21] | Models isotopically instationary labeling data at genome scale using parallel computing | Instationary 13C labeling data, Pool sizes | Parallelized ODE solving (EMU framework) | Photosynthetic organisms, Fed-batch conditions, One-carbon substrate metabolism |

| Enzyme-Constrained Models (GECKO) [12] | Incorporates enzyme constraints and proteomics data into GEMs | Proteomics data, Enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat) | Linear programming, Resource balance analysis | Predicting overflow metabolism, Studying protein allocation under stress |

| 13C Data-Constrained FBA [2] [19] | Uses 13C labeling data to replace optimization assumptions in FBA | 13C labeling data (~48 measurements), GEM | Flux balance analysis without objective function | Identifying flaws in COBRA methods, Robustness testing of GEM reconstructions |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Two-Scale 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (2S-13C MFA)

The 2S-13C MFA approach, implemented in the jQMM library for S. cerevisiae, provides a practical methodology for determining genome-scale fluxes without the need for exhaustive carbon transition mapping [20].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 13C Integration

| Reagent/Software | Specific Type/Version | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| JBEI jQMM Library | Open-source Python library | Provides toolbox for FBA, 13C MFA, and 2S-13C MFA |

| 13C-Labeled Substrate | e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose or [2-13C]glucose | Creates unique labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites |

| Mass Spectrometry | GC-MS or LC-MS systems | Measures mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of metabolites |

| Genome-Scale Model | e.g., iYali4, iML1515, Human1, iSM996 [12] | Provides stoichiometric representation of metabolism |

| BRENDA Database | Comprehensive enzyme kinetic database | Provides kcat values for enzyme constraints in GECKO |

Protocol Steps:

- Experimental Design: Grow the organism (e.g., S. cerevisiae) in minimal medium with a specifically chosen 13C-labeled carbon source (e.g., [1-13C]glucose or [U-13C]glucose).

- Sample Collection: Harvest cells during mid-exponential growth phase and rapidly quench metabolism.

- Metabolite Extraction: Use appropriate extraction protocols for intracellular metabolites, preserving labile compounds.

- Mass Isotopomer Measurement: Analyze metabolite extracts via GC-MS or LC-MS to determine mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) for key metabolic intermediates.

- Data Integration: Input the measured MIDs into the jQMM library along with the genome-scale model.

- Flux Estimation: Utilize the 2S-13C MFA algorithm to compute flux distributions that best fit the experimental labeling data while satisfying stoichiometric constraints.

- Validation: Compare predicted and measured extracellular fluxes to validate model predictions.

Genome-Scale 13C MFA with EMU Framework

This protocol, applied to E. coli models, expands traditional 13C MFA to genome-scale using the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework [17] [21].

Protocol Steps:

- Model Construction: Start with a genome-scale reconstruction (e.g., iAF1260 for E. coli) and eliminate reactions guaranteed not to carry flux based on growth and fermentation data.

- Labeling Experiments: Cultivate cells with specifically labeled substrate (e.g., glucose labeled at the second carbon position).

- Labeling Measurement: Obtain labeling data for amino acid fragments using mass spectrometry.

- Flux Estimation: Estimate metabolic fluxes and confidence intervals by minimizing the sum of squared differences between predicted and measured labeling patterns using the EMU decomposition algorithm.

- Statistical Analysis: Determine flux ranges for key reactions through statistical evaluation of the solution space.

- Model Comparison: Compare flux topology and values between core and genome-scale models to identify consistent and divergent pathways.

GECKO 2.0 for Enzyme-Constrained Modeling

The GECKO 2.0 method enhances GEMs with enzymatic constraints using kinetic and proteomics data [12].

Protocol Steps:

- Model Preparation: Obtain a high-quality GEM for the target organism with accurate GPR associations.

- Kinetic Data Collection: Retrieve enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat values) from the BRENDA database using the automated hierarchical matching procedure in GECKO.

- Proteomics Integration: Incorporate proteomics abundance data, if available, as constraints for individual enzyme demands.

- Model Enhancement: Add enzyme usage pseudo-reactions to represent protein allocation costs.

- Simulation: Perform constraint-based simulations (e.g., resource balance analysis) to predict flux distributions limited by enzyme availability.

- Validation: Compare predictions with experimental growth rates and metabolite secretion profiles.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized conceptual workflow for integrating 13C labeling data with genome-scale models, highlighting the common stages across different methods:

Figure 1: Generalized Workflow for 13C Data Integration with GEMs

Performance Comparison and Robustness Evaluation

Flux Prediction Accuracy

When comparing flux predictions between methods, studies have shown that 13C-constrained approaches provide results similar to traditional 13C MFA for central carbon metabolism while additionally providing flux estimates for peripheral metabolism [2] [19]. The integration of 13C labeling data provides an extra validation layer through matching numerous relative labeling measurements (e.g., 48 measurements in one study), which helps identify where and why several existing COnstraint Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) flux prediction algorithms fail [2].

Impact on Flux Inference Ranges

Scaling 13C MFA to genome-scale impacts the precision of flux estimates. Research on E. coli models demonstrates that genome-scale mapping leads to wider flux inference ranges for key reactions compared to core models [17]:

- Glycolysis flux range doubles due to the possibility of active gluconeogenesis

- TCA flux range expands by 80% due to the availability of bypasses through amino acid metabolism

- Transhydrogenase reaction flux becomes essentially unresolved due to multiple routes for NADPH/NADH interconversion

Robustness to Model Reconstruction Errors

Methods that incorporate 13C labeling data demonstrate significantly greater robustness to errors in genome-scale model reconstruction compared to standard FBA [2] [19]. The experimental validation provided by matching labeling patterns serves as a falsifiability mechanism that FBA lacks, as FBA produces a solution for almost any input without indicating model adequacy [2].

Computational Requirements

Computational demands vary significantly between methods:

- Parallel instationary 13C fluxomics achieves ~15-fold acceleration for constant-step-size modeling and ~5-fold acceleration for adaptive-step-size modeling through parallelization of the EMU framework [21].

- GECKO implementation requires comprehensive parameterization with enzyme kinetic data, with coverage varying significantly between well-studied and less-characterized organisms [12].

The integration of 13C labeling data with genome-scale metabolic models represents a significant advancement in metabolic flux prediction, providing empirically constrained solutions that reduce reliance on assumed cellular objectives. Each methodological approach offers distinct advantages: 2S-13C MFA balances experimental constraint with computational tractability; genome-scale 13C MFA with EMU framework provides comprehensive network coverage; parallel instationary fluxomics enables modeling of dynamic labeling; and GECKO incorporates enzyme capacity constraints.

The selection of an appropriate integration method depends on multiple factors, including the biological questions, available experimental data, computational resources, and target organism. For evaluating genome-scale model reconstruction robustness, 13C constraint methods provide essential validation that can identify network gaps and incorrect annotations, ultimately leading to more accurate metabolic models for engineering and research applications.

The reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) represents a cornerstone of systems biology, enabling researchers to simulate an organism's metabolism in silico. These models integrate genomic, biochemical, and phenotypic data to create a comprehensive network of metabolic reactions, facilitating the study of microbial physiology and its link to pathogenicity. For the zoonotic pathogen Streptococcus suis, a major concern in both swine husbandry and human health, the manually curated iNX525 model provides a high-quality platform for the systematic elucidation of its metabolism [22]. The construction of this model is particularly significant within the broader thesis of evaluating genome-scale model reconstruction robustness. A key challenge in the field is the independent validation of these in silico predictions using experimental data, such as 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA). While the primary validation of the iNX525 model relied on phenotypic growth data and gene essentiality studies, its creation establishes a critical foundation for future 13C data integration, a gold standard for quantifying intracellular reaction rates and rigorously testing model predictions [22] [23].

Model Reconstruction: A Detailed Methodology

Draft Construction and Curation

The reconstruction of the iNX525 model began with the hypervirulent serotype 2 strain SC19, a significant pathogen in both pigs and humans [22]. The process involved a dual-approach strategy to ensure comprehensiveness and accuracy, as outlined in the workflow below.

The initial automated draft from ModelSEED provided a foundation, but a significant part of the reconstruction involved manual curation to address metabolic gaps and enhance model quality [22]. Gaps that prevented the synthesis of essential biomacromolecules were identified using the gapAnalysis program from the COBRA Toolbox. These gaps were then filled by adding relevant reactions and proteins based on several sources: literature on S. suis metabolism, transporters annotated from the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB), and new gene functions assigned via BLASTp searches against the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database [22]. Finally, the model was refined by ensuring all reactions were mass- and charge-balanced, a critical step for thermodynamic feasibility, using the checkMassChargeBalance program [22].

Biomass Composition and Simulation Framework

A critical component of any functional GSMM is its biomass objective function, which defines the metabolic requirements for cellular growth. Since the overall biomass composition of S. suis was not fully characterized, the iNX525 model adopted the macromolecular composition from the closely related Lactococcus lactis (iAO358) model [22]. The final composition includes proteins (46%), DNA (2.3%), RNA (10.7%), lipids (3.4%), lipoteichoic acids (8%), peptidoglycan (11.8%), capsular polysaccharides (12%), and cofactors (5.8%) [22]. The compositions of DNA, RNA, and amino acids were calculated directly from the S. suis SC19 genome and protein sequences, while the compositions of free fatty acids, lipoteichoic acids, and capsular polysaccharides were incorporated from published literature [22].

All model simulations were performed using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a constraint-based modeling approach formulated as a linear programming problem [22]. The general FBA problem is defined as optimizing an objective function (typically biomass production) subject to the constraint that the system is in a pseudo-steady state: S∙v = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the vector of reaction fluxes, bounded by lower and upper limits (vj,min and vj,max) [22]. These simulations were implemented using the COBRA Toolbox in MATLAB with the GUROBI mathematical optimization solver [22].

Performance Validation: iNX525 vs. Experimental Data

Validation Against Growth Phenotypes and Gene Essentiality

The predictive performance of the iNX525 model was rigorously tested against experimental data, primarily focusing on growth capabilities under different nutrient conditions and genetic disturbances [22] [23]. The model demonstrated good agreement with empirical growth phenotypes [22]. For gene essentiality, the model's predictions were compared against three independent mutant screens, achieving strong agreement rates of 71.6%, 76.3%, and 79.6% [22] [23].

A powerful demonstration of the model's utility comes from its integration with high-throughput transposon mutagenesis data, such as Tn-seq. A separate, complementary study used Himar1-based Tn-seq to identify 150 candidate essential genes in S. suis [24]. When the iNX525 model was used to simulate gene deletions under defined conditions, it predicted 165 essential genes [24]. The integration of these two methods revealed a more robust set of 244 candidate essential genes, with 75 genes supported by both approaches, 93 predicted only by the GEM, and 76 detected exclusively by Tn-seq [24]. This synergy highlights how GSMMs can compensate for limitations in experimental techniques (e.g., competitive bias in mutant libraries) and vice-versa (e.g., incomplete pathway annotation in the model).

Quantitative Validation Data

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the iNX525 model and key quantitative results from its validation.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Validation Metrics of the iNX525 Model

| Aspect | Detail | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Model Statistics | 525 genes, 708 metabolites, 818 reactions | [22] [23] |

| Quality Score | 74% overall MEMOTE score | [22] [23] |

| Gene Essentiality Prediction | 71.6%, 76.3%, 79.6% agreement with mutant screens | [22] [23] |

| Virulence-Linked Genes | 131 identified; 79 linked to 167 model reactions | [22] [23] |

| Dual-Function Genes | 26 genes essential for both growth and virulence factor production | [22] [23] |

| Potential Drug Targets | 8 enzymes/metabolites in capsule & peptidoglycan biosynthesis | [22] [23] |

The construction and validation of the iNX525 model, along with its associated experimental validation, relied on a suite of key reagents and computational resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GSMM Reconstruction and Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Context in iNX525 Study |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB-based software suite for constraint-based modeling. | Used for gap filling, model simulation (FBA), and essentiality analysis [22]. |

| GUROBI Solver | A state-of-the-art mathematical optimization solver for linear programming problems. | Employed as the computational engine for solving FBA problems [22]. |

| ModelSEED | An automated pipeline for the reconstruction of draft genome-scale metabolic models. | Generated the initial draft model from the RAST-annotated genome [22]. |

| Chemically Defined Medium (CDM) | A growth medium with a precisely known chemical composition. | Used for in vitro growth assays to validate model predictions under different nutrient conditions [22]. |

| Himar1 Mariner Transposon | A synthetic transposon used for high-throughput, random insertional mutagenesis. | Applied in Tn-seq studies to generate genome-wide mutant libraries for experimental gene essentiality determination [24]. |

| RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology) | A fully-automated service for annotating bacterial and archaeal genomes. | Provided the foundational genome annotation for the S. suis SC19 strain [22]. |

Application in Virulence and Drug Target Discovery

A primary application of the iNX525 model was to investigate the link between S. suis metabolism and its virulence. By comparing model genes against virulence factor databases, researchers identified 131 virulence-linked genes, 79 of which were associated with 167 metabolic reactions within iNX525 [22] [23]. Furthermore, 101 metabolic genes were predicted to influence the formation of nine small molecules linked to virulence [22] [23]. This systems-level analysis enabled the identification of 26 genes that are essential for both cellular growth and the production of key virulence factors [22] [23]. From this critical set, the study pinpointed eight enzymes and metabolites involved in the biosynthesis of capsular polysaccharides and peptidoglycans as promising antibacterial drug targets [22] [23]. These targets are particularly attractive because disrupting them would simultaneously impair bacterial growth and virulence, potentially leading to more effective therapeutics against this zoonotic pathogen.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have become established tools for systematic analyses of metabolism across a wide variety of organisms, enabling quantitative exploration of genotype-phenotype relationships [12] [25]. These computational models simulate metabolic flux distributions by leveraging stoichiometric constraints of biochemical reactions and optimality principles, with applications spanning from model-driven development of efficient cell factories to understanding mechanisms underlying complex human diseases [12] [25]. However, traditional GEMs face significant limitations in predicting biologically meaningful phenotypes because they assume a linear increase in simulated growth and product yields as substrate uptake rates rise—a prediction that often diverges from experimental observations [26]. This discrepancy primarily stems from the fact that classical constraint-based methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) do not account for enzymatic limitations and the associated metabolic costs [12].

The integration of enzyme constraints into metabolic models addresses these limitations by incorporating fundamental biological realities: cells operate with finite proteomic resources and encounter physical constraints such as crowded intracellular volumes and limited membrane surface area [12] [25]. Enzyme-constrained models (ecModels) bridge this gap by incorporating enzyme kinetic parameters and proteomic constraints, enabling more accurate predictions of microbial behaviors under various genetic and environmental conditions [12] [26]. The GECKO (Enhancement of GEMs with Enzymatic Constraints using Kinetic and Omics data) toolbox, first introduced in 2017 and substantially upgraded to version 2.0 in 2022, represents a sophisticated framework for streamlining this integration [12] [25]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates GECKO 2.0's performance against alternative implementations, with particular emphasis on its utility for assessing metabolic model robustness—a crucial consideration when validating predictions with experimental 13C metabolic flux data.

Methodological Framework: How GECKO 2.0 Works

Core Mathematical Principles

Enzyme-constrained flux balance analysis extends traditional FBA by incorporating enzymatic limitations as additional constraints. The standard FBA formulation is a linear programming problem that maximizes an objective function (typically biomass production) subject to stoichiometric constraints:

Maximize (Z = c^{T}v)

Subject to (Sv = 0)

(lbj ≤ vj ≤ ub_j)

Where (S) is the stoichiometric matrix, (v) is the vector of reaction fluxes, and (lbj) and (ubj) are lower and upper bounds constraining reaction (j) [27].

GECKO 2.0 expands this formulation by incorporating enzyme demands for metabolic reactions. For each reaction, the corresponding enzyme is included as a pseudometabolite with a stoichiometric coefficient of (1/k{cat}), where (k{cat}) is the enzyme's turnover number [27]. This creates a modified stoichiometric matrix that includes both metabolic reactions and enzyme usage, with the total enzyme usage constrained by the measured or estimated total protein content available for metabolism [12] [27].

Technical Implementation and Workflow

The GECKO 2.0 toolbox is primarily implemented in MATLAB and consists of several integrated modules [12] [25]. The key enhancement in version 2.0 is its generalized structure that facilitates application to a wide variety of GEMs, not just well-studied model organisms [12]. The workflow encompasses multiple stages:

- Model Preparation: A standard genome-scale metabolic model is loaded and prepared for enhancement.

- Kinetic Parameter Retrieval: The toolbox automatically retrieves enzyme kinetic parameters from the BRENDA database using a hierarchical matching procedure [12].

- Enzyme Integration: Enzymes are incorporated into the model as pseudometabolites, with corresponding usage reactions.

- Proteomics Integration: When available, proteomics data can be incorporated as constraints for individual enzyme concentrations [12].

- Simulation and Analysis: The enhanced model can be simulated using constraint-based methods, with utilities for various analysis types.

A critical innovation in GECKO 2.0 is its improved parameterization procedure, which ensures high coverage of kinetic constraints even for poorly studied organisms [12]. This addresses a key limitation in the original GECKO implementation, where quantitative predictions were highly sensitive to the distribution of incorporated kinetic parameters [12].

Figure 1: GECKO 2.0 workflow for constructing enzyme-constrained models and validating predictions with 13C data.

Comparative Analysis of Enzyme-Constrained Modeling Tools

Toolbox Capabilities and Features

The landscape of enzyme-constrained modeling tools has expanded significantly since the introduction of the original GECKO framework. Currently, researchers have multiple options for constructing ecModels, each with distinct capabilities, strengths, and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Enzyme-Constrained Modeling Software Platforms

| Feature | GECKO 2.0 | geckopy 3.0 | ECMpy 2.0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Language | MATLAB | Python | Python |

| License | Open-source | Open-source | Open-source |

| Kinetic Parameter Source | BRENDA database | BRENDA database | BRENDA + Machine Learning prediction |

| Supported Organisms | Any with GEM reconstruction | Escherichia coli | Multiple organisms |

| Proteomics Integration | Yes, with relaxation | Yes, with suite of relaxation algorithms | Yes |

| Thermodynamic Constraints | Limited | Yes, via pytfa integration | Limited |

| Community Support | Active repository and chat room | Growing community | Documentation and examples |

| Key Innovation | Automated pipeline for ecModels | SBML-compliant protein typing | Automated construction with expanded parameter coverage |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Validation

Experimental validation of ecModel predictions typically involves comparing simulated growth rates, substrate uptake rates, byproduct secretion, and metabolic flux distributions against empirically measured values. For robustness assessment specifically, researchers often utilize 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) as a gold standard for validating intracellular flux distributions [12].

In benchmark studies, GECKO-enhanced models have demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional GEMs. For Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the ecYeast model successfully predicted the critical dilution rate at the onset of the Crabtree effect—a phenomenon traditional GEMs fail to capture accurately [12]. The enzyme-constrained model also provided quantitative predictions of exchange fluxes at fermentative conditions that aligned more closely with experimental measurements [12].

Similar improvements were observed for Escherichia coli models, where the incorporation of enzyme constraints yielded more realistic predictions of overflow metabolism and growth yields across different substrate conditions [12] [25]. The table below summarizes quantitative performance improvements reported in comparative studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Metabolic Modeling Approaches

| Organism | Prediction Type | Standard GEM Error | ecModel Error | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae | Critical dilution rate | 35-50% | 5-15% | Chemostat cultures |

| S. cerevisiae | Ethanol secretion | 40-60% | 10-20% | Metabolite measurements |

| E. coli | Acetate overflow | 50-70% | 15-25% | Metabolite measurements |

| Y. lipolytica | Growth yield | 25-40% | 10-20% | Bioreactor experiments |

| H. sapiens (cancer cells) | ATP yield | 30-50% | 15-25% | 13C flux analysis |

Robustness Analysis in Metabolic Networks

Theoretical Framework for Assessing Robustness

Robustness in metabolic systems refers to a network's intrinsic ability to maintain functionality despite perturbations—whether genetic, environmental, or stochastic [28]. In the context of GECKO 2.0 applications, robustness takes on additional dimensions: it encompasses both the structural robustness of the metabolic network itself and the predictive robustness of the model when confronted with experimental validation data like 13C flux measurements.

A rigorous mathematical framework for quantifying metabolic robustness utilizes the concept of Probability of Failure (PoF), defined as the probability that random loss-of-function mutations disable network functionality [28]. This approach leverages Minimal Cut Sets (MCSs)—minimal sets of reaction deletions that suppress growth—to compute failure frequencies:

[ F := \sum{d=1}^{r} wd f_d ]

Where (wd) is the probability that (d) mutations occur (following a binomial distribution), and (fd) is the failure frequency for exactly (d) mutations [28]. Enzyme-constrained models enhance this analysis by incorporating the additional dimension of proteomic limitations, which can reveal whether apparent robustness stems from metabolic redundancy or from enzyme capacity buffering.

13C Flux Analysis as a Validation Tool

13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a critical experimental method for validating metabolic model predictions. By tracing stable isotope labels through metabolic networks, researchers can obtain quantitative measurements of intracellular flux distributions that serve as ground truth for evaluating model accuracy [12].

When enzyme-constrained models are validated using 13C data, several advantages emerge:

- Constrained Solution Space: Enzyme constraints reduce the feasible solution space, leading to more precise flux predictions that align better with 13C measurements [12].

- Mechanistic Explanations: ecModels provide mechanistic explanations for why certain flux distributions are preferred—often relating to enzyme efficiency or abundance limitations [12].

- Condition-Specific Accuracy: ecModels maintain higher accuracy across diverse environmental conditions, as proteomic constraints change predictably with growth conditions [12].

The robustness of a metabolic model can be quantified by its ability to predict 13C-measured fluxes across multiple genetic and environmental perturbations. Models with higher robustness will show consistent accuracy despite these variations, whereas fragile models may perform well under reference conditions but diverge significantly under perturbation.

Figure 2: Framework for evaluating metabolic model robustness using 13C validation data across multiple perturbation conditions.

Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme-Constrained Modeling

Implementing enzyme-constrained models requires both computational tools and access to specialized databases and resources. The following table catalogs essential research reagents for constructing and validating ecModels.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Enzyme-Constrained Modeling

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database | Kinetic database | Source of enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat values) | https://www.brenda-enzymes.org/ |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB package | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | https://opencobra.github.io/cobratoolbox/ |

| GECKO 2.0 | MATLAB toolbox | Enhancement of GEMs with enzymatic constraints | https://github.com/SysBioChalmers/GECKO |

| ecModels Container | Model repository | Version-controlled collection of ecModels | https://github.com/SysBioChalmers/ecModels |

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot | Protein database | Protein sequences and functional information | https://www.uniprot.org/ |

| ModelSEED | Reconstruction platform | Automated metabolic model construction | https://modelseed.org/ |

| MEMOTE | Assessment tool | Quality assessment of metabolic models | https://memote.io/ |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The integration of enzyme constraints represents a significant advancement in metabolic modeling, addressing fundamental limitations of traditional GEMs while providing more biologically realistic predictions. GECKO 2.0 stands out for its comprehensive approach to enzyme constraint integration, automated pipeline for model updating, and flexibility in handling diverse organisms. When evaluated against alternatives like geckopy 3.0 and ECMpy 2.0, each platform offers distinct advantages—GECKO 2.0 for its maturity and extensive testing, geckopy 3.0 for its Python implementation and thermodynamic constraints, and ECMpy 2.0 for its machine learning-enhanced parameter prediction [27] [26].

For researchers focused on model robustness and 13C validation, GECKO 2.0 provides several critical capabilities. The incorporation of enzyme constraints naturally reduces solution space variability, leading to more robust flux predictions that align better with 13C measurements across diverse conditions [12]. Furthermore, the explicit representation of proteomic limitations offers mechanistic explanations for observed flux distributions, moving beyond phenomenological observations to principled predictions.

Future developments in enzyme-constrained modeling will likely focus on several frontiers: (1) improved parameter estimation through machine learning and multi-omics integration, (2) expansion to multi-cellular systems and community modeling, (3) dynamic extensions for capturing metabolic transitions, and (4) enhanced usability for non-specialist researchers. As these tools become more sophisticated and accessible, they will play an increasingly central role in metabolic engineering, systems biology, and drug development—enabling more reliable predictions of cellular behavior in both natural and engineered contexts.

The ongoing validation of enzyme-constrained models against 13C flux data and other experimental measurements remains crucial for refining these computational frameworks. As the field advances, the integration of enzyme constraints will likely become standard practice in metabolic modeling, much like the incorporation of gene-protein-reaction associations was in previous decades. For researchers working at the intersection of computational modeling and experimental validation, GECKO 2.0 and its alternatives offer powerful platforms for exploring the constraints that shape metabolic function across the tree of life.

Metabolic flux analysis represents a cornerstone of systems biology, providing a mathematical framework to simulate the integrated metabolic phenotype of living cells. The core challenge in this field lies in accurately estimating or predicting in vivo reaction rates (fluxes), which cannot be measured directly but must be inferred through computational models constrained by experimental data [29]. Two predominant constraint-based methodologies have emerged: 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). Both approaches rely on metabolic network models operating at steady state, where reaction rates and metabolic intermediate levels remain invariant [29]. The fidelity of these models to biological reality hinges critically on robust validation procedures and appropriate model selection criteria, particularly when integrating 13C labeling data to evaluate and enhance genome-scale model robustness [29].

This guide provides a systematic comparison of workflows for generating metabolic flux maps, with particular emphasis on validation methodologies that ensure reliable predictions for research and biotechnological applications.

Comparative Analysis of Flux Analysis Methods

Core Principles and Applications

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of 13C-MFA and FBA.

| Feature | 13C-MFA | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Input | Isotopic labeling from 13C-tracers (e.g., MID measurements) | Stoichiometric network, exchange flux constraints, objective function |

| Mathematical Foundation | Parameter estimation (non-linear optimization minimizing difference between simulated and measured labeling) | Linear programming (optimizing a biological objective) |

| Flux Output | Estimated fluxes with confidence intervals | Predicted fluxes (single solution or solution space) |

| Model Scale | Typically core metabolism | Genome-scale and core models |

| Key Applications | Quantifying in vivo pathway fluxes in central metabolism; Metabolic engineering | Predicting genotype-phenotype relationships; Systems-level analysis; Drug target identification |

| Validation Strength | Direct statistical comparison of model fit to experimental isotopic labeling data [29] | Comparison against experimental growth phenotypes, gene essentiality data, or 13C-MFA fluxes [29] [22] |

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationships and sequential steps shared and diverged in both 13C-MFA and FBA workflows, highlighting critical validation points.

Figure 1: A unified workflow for metabolic flux analysis, showing parallel pathways for 13C-MFA (left) and FBA (right). The red validation step is critical for assessing model robustness and must be tailored to each method.

Step-by-Step Workflow and Methodologies

Network Reconstruction and Curation

The initial phase involves constructing a biochemically accurate, genome-scale metabolic network. This reconstruction catalogs all known metabolic reactions, associated genes, gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules, and metabolites [30]. For 13C-MFA, this network must be augmented with atom mappings describing the positions and interconversions of carbon atoms in reactants and products [29]. For FBA, a key decision is the selection of an appropriate objective function (e.g., biomass maximization for growth simulation), which serves as the optimization target [29].

High-quality, manually curated reconstructions like AGORA2 (for human microbes) demonstrate the importance of extensive manual refinement. AGORA2 incorporates data from 732 peer-reviewed papers and two textbooks, resulting in the addition or removal of an average of 686 reactions per reconstruction compared to draft models [31]. This curation significantly improves predictive accuracy over automated drafts, achieving 72-84% accuracy against independent experimental datasets [31].

Experimental Data Acquisition and Integration

Table 2: Experimental data requirements and protocols for flux analysis.

| Data Type | Experimental Protocol Summary | Role in Constraining Models |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeling Data (for 13C-MFA) | Feed cells with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-13C]glucose); Harvest cells during isotopic steady state; Quench metabolism; Derivatize metabolites; Measure Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) via GC-MS or LC-MS [29]. | Provides internal constraint on network fluxes by requiring the simulated label distribution to match measured MIDs. |

| Exchange Flux Measurements (for FBA) | Measure substrate consumption and product secretion rates in bioreactor or culture; Quantify growth rate (biomass accumulation); Use enzymatic assays, HPLC, or optical density [22]. | Constrains the boundary of the network, defining available nutrient inputs and product outputs. |