Validating Internal Flux Predictions in Flux Balance Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedicine

Accurately validating internal flux predictions is a critical challenge in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), directly impacting its reliability in drug discovery, metabolic engineering, and systems biology.

Validating Internal Flux Predictions in Flux Balance Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedicine

Abstract

Accurately validating internal flux predictions is a critical challenge in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), directly impacting its reliability in drug discovery, metabolic engineering, and systems biology. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists, exploring the foundational principles of FBA validation, advanced methodologies like machine learning and hybrid frameworks, and robust troubleshooting techniques. It systematically compares the performance of novel approaches against traditional FBA, evaluating their accuracy in predicting gene essentiality and microbial interactions. By synthesizing the latest advancements, this resource aims to enhance confidence in flux predictions and foster their broader application in biomedical and clinical research.

The Critical Importance of Validating FBA Predictions in Biomedical Research

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has emerged as a fundamental computational tool in systems biology for predicting metabolic fluxes in microorganisms. This constraint-based modeling approach leverages genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to simulate metabolic network operations under steady-state conditions, enabling researchers to predict how microorganisms allocate resources to different biochemical reactions. However, the inherent gap between in silico predictions and in vivo biological reality represents a significant challenge in the field. Model validation serves as the critical bridge across this gap, ensuring that computational predictions reflect actual cellular behavior. Without rigorous validation procedures, FBA predictions risk remaining theoretical exercises with limited practical application in biotechnology and drug development.

The validation of metabolic models has gained increasing attention as the limitations of prediction-only approaches become apparent. As Kaste and Shachar-Hill note, "Despite advances in other areas of the statistical evaluation of metabolic models, validation and model selection methods have been underappreciated and underexplored" [1] [2]. This comprehensive review examines the current state of validation methodologies for FBA, compares traditional and emerging approaches, and provides researchers with practical frameworks for enhancing the biological relevance of their metabolic models.

Understanding Flux Balance Analysis: Principles and Predictive Limitations

Flux Balance Analysis operates on the fundamental principle of mass conservation within metabolic networks operating at steady state. The core mathematical framework involves a stoichiometric matrix (S) that encapsulates all known metabolic reactions in an organism, with constraints imposed on reaction fluxes based on physiological and biochemical considerations [3]. The solution space defined by these constraints contains all possible flux distributions, from which FBA identifies an optimal solution using biologically relevant objective functions, most commonly biomass maximization [1].

The standard FBA workflow involves several key steps: (1) reconstruction of a genome-scale metabolic model incorporating all known metabolic reactions; (2) definition of constraints based on nutrient availability, reaction thermodynamics, and enzyme capacities; (3) selection of an appropriate objective function; and (4) linear programming to identify the flux distribution that optimizes the objective function [3]. The iML1515 model for E. coli, for instance, includes "1,515 open reading frames, 2,719 metabolic reactions, and 1,192 metabolites" [3], representing the comprehensive nature of modern metabolic reconstructions.

Despite its widespread adoption, FBA faces several fundamental limitations that necessitate robust validation. First, FBA predictions are highly dependent on the selected objective function, which may not accurately reflect cellular priorities across different environmental conditions [4]. Second, standard FBA does not incorporate regulatory constraints or kinetic parameters, potentially leading to unrealistic flux predictions [3]. Third, the assumption of steady-state metabolism rarely holds in dynamic biological systems [4]. These limitations underscore why validation is not merely an optional step but an essential component of credible metabolic modeling.

Validation Methodologies: A Comparative Framework

Established Validation Techniques for FBA Predictions

Validation approaches for FBA can be categorized into several distinct methodologies, each with specific applications and limitations. The most common techniques include:

Growth Rate Comparisons: This approach validates FBA predictions by comparing computed growth rates against experimentally measured values under specific nutrient conditions [1]. While this method provides quantitative validation of overall network functionality, it offers limited insights into the accuracy of internal flux predictions. As noted in metabolic validation literature, this approach "provides quantitative information on the overall efficiency of substrate conversion to biomass, but is uninformative with respect to accuracy of internal flux predictions" [1].

Qualitative Growth/No-Growth Assessment: This binary validation method tests whether FBA models correctly predict microbial viability under different nutrient conditions [1]. By examining presence/absence of reactions necessary for substrate utilization and biomass synthesis, researchers can validate basic network functionality. However, this approach offers only qualitative insights and does not address the quantitative accuracy of flux predictions.

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) Validation: Considered the gold standard for flux validation, 13C-MFA uses isotopic labeling experiments to measure intracellular fluxes empirically [1] [2]. The method involves feeding 13C-labeled substrates to cells and using mass spectrometry or NMR to measure the resulting isotope patterns in metabolic products. The computational challenge of 13C-MFA involves "working backwards from measured label distributions to flux maps by minimizing the residuals between measured and estimated Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) values by varying flux and pool size estimates" [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Established Validation Techniques for FBA Models

| Validation Method | Measured Parameters | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate Comparison | Predicted vs. experimental growth rates | Quantitative assessment of overall network function | Does not validate internal flux distributions |

| Growth/No-Growth Assessment | Model prediction of viability under specific conditions | Validates network completeness and functionality | Qualitative only; no flux quantification |

| 13C-MFA | Internal flux distributions using isotopic labeling | Gold standard for direct flux measurement; quantitative | Experimentally complex and resource-intensive |

| Flux Variability Analysis | Range of possible fluxes for each reaction | Identifies flexible and rigid parts of metabolism | Does not provide single solution; range may be large |

Emerging Validation Approaches

Recent methodological advances have expanded the validation toolkit for metabolic models:

Machine Learning Integration: Supervised machine learning models using transcriptomics and/or proteomics data have shown promise for predicting metabolic fluxes under various conditions [5]. In comparative studies, "the proposed omics-based ML approach is promising to predict both internal and external metabolic fluxes with smaller prediction errors in comparison to the pFBA approach" [5]. This data-driven approach represents a paradigm shift from purely knowledge-driven constraint-based modeling.

Multi-Scale Validation Frameworks: Integrating FBA with higher-level physiological measurements provides systems-level validation. For instance, the TIObjFind framework "imposes Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to analyze adaptive shifts in cellular responses throughout different stages of a biological system" [4]. This approach determines Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to an objective function, aligning optimization results with experimental flux data.

Enzyme-Constrained Modeling: Approaches like ECMpy incorporate enzyme kinetic parameters into FBA models, "ensur[ing] that fluxes through pathways are capped by enzyme availability and the catalytic efficiency of the enzymes, to avoid arbitrarily high flux predictions" [3]. This method narrows the solution space and produces more biologically realistic flux distributions.

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis Protocol

13C-MFA remains the most rigorous method for validating intracellular flux predictions. The standard protocol involves:

Step 1: Tracer Selection and Experimental Design

- Select appropriate 13C-labeled substrates (typically glucose or glycerol) based on the metabolic network under investigation

- Design parallel labeling experiments using multiple tracers to enhance flux resolution [1]

- Determine optimal labeling time to ensure isotopic steady state while minimizing metabolic redistribution

Step 2: Cultivation and Sampling

- Grow microorganisms in controlled bioreactors with defined media containing 13C-labeled substrates

- Monitor growth parameters (OD600, nutrient consumption, byproduct formation)

- Harvest cells during mid-exponential growth phase for metabolic snapshot

- Quench metabolism rapidly using cold methanol or other quenching agents

Step 3: Mass Isotopomer Distribution Analysis

- Extract intracellular metabolites using appropriate extraction protocols

- Derivatize metabolites for GC-MS analysis when necessary

- Measure mass isotopomer distributions using GC-MS or LC-MS

- Correct raw MS data for natural isotope abundances and instrument drift

Step 4: Computational Flux Estimation

- Input measured MID data into flux estimation software (e.g., INCA, OpenFLUX)

- Define metabolic network model including atom transitions

- Use parameter fitting algorithms to minimize residuals between measured and simulated MIDs

- Employ statistical tests (e.g., χ2-test) to evaluate goodness-of-fit [1] [2]

- Calculate confidence intervals for estimated fluxes using Monte Carlo sampling or sensitivity analysis

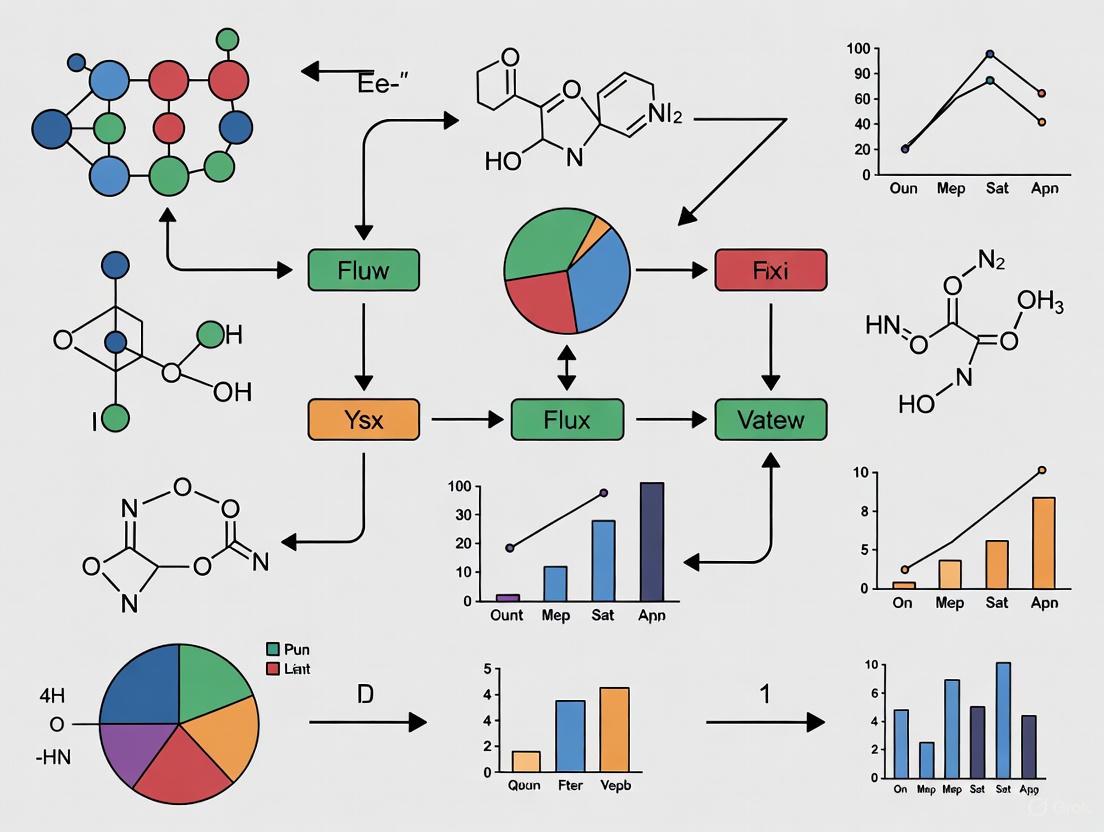

The entire workflow for 13C-MFA validation can be visualized as follows:

Machine Learning-Based Flux Prediction Protocol

For researchers interested in emerging validation approaches, the machine learning protocol for flux prediction involves:

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Collect matched multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics) and flux data (from 13C-MFA or literature) for training

- Normalize omics data using appropriate methods (TPM for transcriptomics, iBAQ for proteomics)

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets (typically 70/15/15 ratio)

Model Selection and Training

- Test multiple ML algorithms (random forests, gradient boosting, neural networks) for flux prediction

- Train models to predict metabolic fluxes from omics input features

- Optimize hyperparameters using cross-validation on the training set

- Regularize models to prevent overfitting to limited training data

Performance Evaluation

- Compare ML-predicted fluxes against experimentally determined fluxes

- Calculate error metrics (mean absolute error, root mean square error) for internal and exchange fluxes

- Benchmark against traditional FBA with pFBA or other variants

- Perform statistical testing to determine significance of performance improvements

Comparative Performance Analysis: Traditional FBA vs. Enhanced Approaches

Quantitative comparison of different modeling approaches reveals significant differences in predictive performance. Recent studies provide empirical data on the accuracy of various methods:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Metabolic Modeling and Validation Approaches

| Modeling Approach | Average Error in Central Carbon Fluxes | External Flux Prediction Accuracy | Experimental Data Requirements | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard FBA | 25-40% [5] | Moderate | Low (growth rates only) | Low |

| Parsimonious FBA | 20-35% [5] | Moderate-High | Low (growth rates only) | Low |

| Machine Learning with Omics | 10-25% [5] | High | High (transcriptomics/proteomics + flux data) | High |

| Enzyme-Constrained FBA | 15-30% [3] | High | Medium (enzyme abundance + kcat values) | Medium |

| 13C-MFA | N/A (gold standard) | N/A (gold standard) | Very High (isotopic labeling) | Very High |

The performance advantages of machine learning approaches are particularly notable. As Henriques and Costa report, "the proposed omics-based ML approach is promising to predict both internal and external metabolic fluxes with smaller prediction errors in comparison to the pFBA approach" [5]. However, this improved performance comes with substantial data requirements, as ML models need extensive training datasets of matched omics and flux measurements.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between model sophistication, data requirements, and prediction accuracy:

Successful implementation of FBA validation requires specific computational and experimental resources:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FBA Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Model Databases | BiGG Models [1], MetaCyc [3] | Curated metabolic reconstructions | Standardized nomenclature, reaction databases |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Software | COBRA Toolbox [1], cobrapy [3] | FBA implementation and simulation | Multiple algorithm options, model standardization |

| Flux Validation Software | INCA, OpenFLUX [1] | 13C-MFA computational analysis | Statistical evaluation, confidence interval calculation |

| Isotopic Tracers | 13C-Glucose, 13C-Glycerol [1] | Experimental flux determination | Specific labeling patterns for flux resolution |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS, LC-MS [1] [6] | Mass isotopomer measurement | High sensitivity, resolution of isotopic distributions |

| Enzyme Kinetic Databases | BRENDA [3] | Enzyme constraint parameters | kcat values for enzyme-limited models |

| Omics Data Resources | PAXdb [3], GEO | Protein/gene expression data | ML model training, context-specific modeling |

Validation represents the essential bridge between computational prediction and biological reality in metabolic modeling. As this comparison demonstrates, multiple validation approaches exist along a spectrum of complexity and accuracy, from simple growth rate comparisons to sophisticated 13C-MFA experiments. The selection of appropriate validation methods must balance practical constraints with the required level of confidence in model predictions.

Emerging approaches, particularly the integration of machine learning with multi-omics data and the incorporation of enzyme constraints, show significant promise for enhancing predictive accuracy while maintaining biological relevance. However, these advanced methods require substantial experimental investment and computational sophistication. Regardless of the specific techniques employed, the fundamental principle remains: rigorous validation is not an optional supplement to FBA but an essential component of biologically meaningful metabolic modeling. By embracing comprehensive validation frameworks, researchers can narrow the gap between prediction and reality, accelerating the application of metabolic models in biotechnology, drug development, and fundamental biological research.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) serves as a cornerstone computational method for predicting intracellular metabolic fluxes in systems biology and metabolic engineering. By leveraging genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), FBA simulates cellular metabolism under the assumption of steady-state and optimality toward a defined biological objective, most commonly biomass maximization [7]. The mathematical foundation of FBA relies on solving a linear programming problem that finds a flux distribution maximizing or minimizing an objective function within a solution space constrained by stoichiometry and reaction boundaries [7]. Despite its widespread adoption and computational efficiency, FBA faces two fundamental challenges that significantly impact the accuracy of its flux predictions: the selection of appropriate biological objective functions and the proper specification of metabolic network models.

Model misspecification, particularly in the form of missing reactions in the stoichiometric matrix, introduces systematic biases that can disproportionately affect flux estimates, even when the overall statistical regression appears significant [8]. Simultaneously, the assumption that cellular metabolism operates at a single optimal state represents an oversimplification of biological reality, as natural selection may tolerate suboptimal flux configurations that balance multiple competing cellular demands [9]. These challenges are particularly relevant for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on accurate flux predictions for identifying metabolic vulnerabilities in pathogens, understanding disease mechanisms, and engineering industrial microbial strains. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of emerging methodologies designed to address these core challenges, offering objective performance evaluations and detailed experimental protocols to enhance the validation of internal flux predictions in FBA research.

The Challenge of Model Misspecification: Detection and Resolution

Model misspecification in metabolic networks, especially the omission of critical biochemical reactions, represents a persistent challenge in constraint-based modeling. The problem is particularly insidious because a statistically significant regression does not guarantee high accuracy of flux estimates, and even reactions with low flux magnitude can cause disproportionately large biases when omitted [8]. Traditional goodness-of-fit tests may fail to detect these specification errors due to incorrect assumptions about data noise characteristics or underlying model structure [8].

Statistical tests adapted from linear least squares regression have demonstrated efficacy in detecting missing reactions in overdetermined MFA. Ramsey's Regression Equation Specification Error Test (RESET), the F-test, and the Lagrange multiplier test have been evaluated for this purpose, with the F-test showing particular efficiency in identifying omitted reactions [8]. An iterative procedure using the F-test has been proposed to robustly correct for such omissions, successfully applied to Chinese hamster ovary and random metabolic networks [8]. This approach enables systematic assessment, detection, and resolution of stoichiometric matrix misspecifications that would otherwise compromise flux prediction accuracy.

Table 1: Statistical Tests for Detecting Model Misspecification in Metabolic Networks

| Statistical Test | Primary Function | Performance Characteristics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-test | Detects missing reactions in stoichiometric matrix | Efficiently identifies reaction omissions; enables iterative correction | Overdetermined MFA; network validation |

| RESET Test | Identifies specification errors in regression equations | Detects misspecifications from incorrect functional form | Regression-based flux estimation |

| Lagrange Multiplier Test | Assesses constraints in optimization problems | Evaluates parameter restrictions in constrained models | Generalized least squares formulations |

Suboptimal Objective Functions: Beyond Single-Point Optimality

The conventional FBA framework assumes that cellular metabolism operates at a single optimal state, typically maximizing biomass production or ATP yield. However, this assumption represents a biological oversimplification, as natural selection must balance multiple competing objectives and may tolerate suboptimal flux configurations that enhance robustness or accommodate fluctuating environmental conditions [9]. The problem of mathematical degeneracy—where multiple flux distributions yield equally optimal objective values—further complicates flux predictions and limits their practical utility [9].

The Perturbed Solution Expected Under Degenerate Optimality (PSEUDO) approach addresses these limitations by proposing that microbial metabolism is better represented as a cloud of nearly optimal flux distributions rather than a single ideal solution [9]. This method incorporates an objective function that accounts for a region of degenerate near-optimality, where flux configurations supporting at least 90% of maximal growth rate are considered equally plausible [9]. The geometric formulation finds the minimum distance between the wild-type near-optimal region and the mutant flux space, resulting in improved prediction of flux redistribution in metabolic mutants compared to traditional FBA and MOMA approaches [9].

Diagram 1: Conceptual framework of the PSEUDO method for predicting mutant fluxes based on proximity to the wild-type near-optimal region.

Bayesian methods offer another paradigm for addressing model uncertainty in flux estimation. Bayesian 13C-metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) unifies data and model selection uncertainty within a coherent statistical framework, enabling multi-model flux inference that is more robust than single-model approaches [10]. Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) operates as a "tempered Ockham's razor," assigning low probabilities to both unsupported and overly complex models, thereby alleviating model selection uncertainty [10]. This approach is particularly valuable for modeling bidirectional reaction steps, which become statistically testable within the Bayesian framework.

Comparative Analysis of Advanced Methodologies for Flux Prediction

Recent methodological advances have introduced innovative approaches to overcome the limitations of traditional FBA. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these methodologies, highlighting their respective approaches to addressing model misspecification and objective function selection.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Advanced Flux Prediction Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Approach | Validation Results | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) [11] | Monte Carlo sampling + supervised learning | 95% accuracy in E. coli gene essentiality prediction; outperforms FBA | No optimality assumption required; applicable to diverse organisms | Computationally intensive for large-scale models |

| NEXT-FBA [12] | Neural networks relate exometabolomic data to flux constraints | Outperforms existing methods in 13C data validation | Minimal input data requirements for pre-trained models | Dependent on quality and diversity of training data |

| TIObjFind [13] | Metabolic Pathway Analysis + FBA with Coefficients of Importance | Identifies stage-specific metabolic objectives; good match with experimental data | Pathway-specific weighting improves interpretability | Requires experimental flux data for calibration |

| Bayesian 13C-MFA [10] | Multi-model inference with Bayesian Model Averaging | Robust to model uncertainty; enables bidirectional flux estimation | Unified framework for data and model uncertainty | Computational complexity; unfamiliar to many researchers |

| PSEUDO-FBA [9] | Degenerate near-optimal flux regions | Better predicts central carbon flux redistribution in E. coli mutants | Accounts for biological flexibility and robustness | Requires definition of optimality threshold (e.g., 90%) |

The integration of machine learning with constraint-based models represents a particularly promising direction. NEXT-FBA (Neural-net EXtracellular Trained Flux Balance Analysis) utilizes artificial neural networks trained with exometabolomic data to derive biologically relevant constraints for intracellular fluxes in GEMs [12]. This hybrid stoichiometric/data-driven approach has demonstrated superior performance in predicting intracellular fluxes that align closely with experimental 13C validation data [12]. Similarly, Flux Cone Learning employs Monte Carlo sampling and supervised learning to identify correlations between metabolic space geometry and experimental fitness scores, achieving best-in-class accuracy for predicting metabolic gene essentiality across organisms of varying complexity [11].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol 1: Model Misspecification Testing with Statistical Methods

The detection and correction of model misspecification requires a systematic experimental approach:

- Initial Flux Estimation: Perform ordinary least square (OLS) or generalized least square (GLS) regression to obtain initial flux estimates based on the stoichiometric model [8].

- Goodness-of-Fit Assessment: Apply standard goodness-of-fit tests to evaluate model consistency with experimental data.

- Specification Error Testing: Implement statistical tests including Ramsey's RESET test, F-test, and Lagrange multiplier test to detect potential model misspecifications [8].

- Iterative Model Correction: For significant F-test results indicating missing reactions, apply an iterative procedure to identify and incorporate omitted reactions [8].

- Bias Evaluation: Compare flux estimates before and after correction, noting that removal of reactions with low flux magnitude can cause disproportionately large biases [8].

Protocol 2: Flux Cone Learning for Gene Essentiality Prediction

The application of Flux Cone Learning for predicting metabolic gene essentiality follows a structured pipeline:

- Metabolic Space Sampling: For each gene deletion, use Monte Carlo sampling to generate a corpus of flux distributions (typically 100 samples/cone) from the modified metabolic space [11].

- Feature Matrix Construction: Create a feature matrix with k × q rows and n columns, where k is the number of gene deletions, q is the number of flux samples per deletion cone, and n is the number of reactions in the GEM [11].

- Model Training: Train a supervised learning model (e.g., random forest classifier) using flux samples alongside experimentally determined essentiality labels for each deletion [11].

- Prediction Aggregation: Apply a majority voting scheme to aggregate sample-wise predictions into deletion-wise predictions [11].

- Validation: Evaluate model performance using held-out genes, comparing predictions against experimental essentiality data and benchmarking against FBA predictions [11].

Diagram 2: Flux Cone Learning workflow for predicting gene deletion phenotypes from metabolic space geometry.

Protocol 3: PSEUDO-FBA for Mutant Flux Prediction

Implementation of the PSEUDO method for predicting metabolic behavior in mutants involves:

- Wild-Type Near-Optimal Region Definition: Solve a standard FBA problem to determine maximum growth rate (f̂GROWTH), then define a region (p) containing flux configurations with nearly optimal growth (typically ≥90% of maximum) [9].

- Mutant Constraint Application: Introduce additional flux bounds (b'L, b'U) representing the metabolic gene deletion or reaction knockout [9].

- Distance Minimization: Solve the optimization problem to find the minimum Euclidean distance between the wild-type near-optimal region (p) and the mutant flux space (q) [9].

- Solution Interpretation: A minimum distance of zero indicates overlapping regions (degenerate case), while non-zero distances identify the most biologically plausible flux configuration [9].

- Validation: Compare PSEUDO predictions against experimental flux measurements in mutants, demonstrating improved accuracy over FBA and MOMA for central carbon metabolism [9].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Flux Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Modeling | COBRA Toolbox [1], cobrapy [1] | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | FBA, variant simulation, model quality control |

| Model Validation | MEMOTE [1] | Metabolic model tests | Stoichiometric consistency, biomass precursor synthesis validation |

| Pathway Analysis | TIObjFind [13] | Topology-informed objective identification | Pathway-specific weighting, metabolic shift identification |

| Bayesian Flux Estimation | Bayesian 13C-MFA [10] | Multi-model flux inference | Robust flux estimation, bidirectional reaction testing |

| Machine Learning Integration | NEXT-FBA [12], FCL [11] | Data-driven constraint definition | Exometabolomic data integration, phenotypic prediction |

The accurate prediction of intracellular metabolic fluxes requires careful attention to both model specification and objective function selection. Statistical approaches for detecting missing reactions in stoichiometric models provide a systematic framework for addressing network incompleteness, while methods that account for degenerate optimality regions offer more biologically realistic representations of cellular metabolic states. The integration of machine learning with constraint-based models, as demonstrated by Flux Cone Learning and NEXT-FBA, represents a promising direction for enhancing predictive accuracy without relying on strong optimality assumptions.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advanced methodologies offer improved capabilities for identifying essential metabolic functions, predicting genetic intervention outcomes, and understanding metabolic adaptations in disease states. The experimental protocols and resources outlined in this guide provide a foundation for implementing these approaches, with appropriate validation against experimental data remaining essential for establishing predictive confidence. As the field continues to evolve, the development of standardized validation frameworks and benchmark datasets will be crucial for advancing the reliability and application of flux prediction methods across diverse biological contexts.

The constraint-based modeling of cellular metabolism relies on a core mathematical framework that predicts how metabolic networks behave under defined conditions. This framework is built upon three foundational concepts: the steady-state assumption, which posits that intracellular metabolites are balanced; the flux cone, which geometrically defines all possible metabolic states; and the solution space, which represents the set of all feasible flux distributions satisfying model constraints [7]. The validation of internal flux predictions in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) research depends critically on accurately characterizing and navigating this solution space [12].

The steady-state assumption provides the physiological justification for converting a dynamic system into a tractable algebraic problem, forming the equation S ∙ v = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the flux vector [7]. This equation defines the flux cone as a high-dimensional convex polyhedral cone in flux space [14] [11]. In practical applications with additional constraints, this cone becomes a more complex solution space polytope. Understanding the geometry of these structures is crucial for improving the biological relevance of flux predictions, driving the development of advanced methods that move beyond single-point FBA solutions to explore the entire space of possible metabolic behaviors [15].

Theoretical Foundations: From Stoichiometry to Solution Spaces

The Steady-State Assumption: Mathematical and Physiological Justification

The steady-state assumption is a cornerstone of constraint-based modeling, mathematically expressed as the requirement that production and consumption rates for each metabolite balance, resulting in no net accumulation over time [7]. This is formalized as:

Input - Output = 0 or more precisely as the matrix equation: S ∙ v = 0 [7]

This assumption can be justified from two complementary perspectives:

- Timescales Perspective: Metabolic reactions occur much faster than genetic regulation or cellular growth, making metabolism able to rapidly adapt to changing conditions [16].

- Averaging Perspective: Over sufficiently long time periods, no metabolite can accumulate or deplete indefinitely, making the assumption applicable even to oscillating and growing systems without requiring quasi-steady-state at every time point [16].

This mathematical foundation enables the analysis of metabolic networks without requiring difficult-to-measure kinetic parameters, instead focusing on network stoichiometry and topology [16] [3].

The Flux Cone: Geometric Representation of Metabolic Capabilities

The flux cone represents the set of all possible steady-state flux distributions through a metabolic network, defined mathematically by:

S ∙ v = 0, with vᵢ ≤ v ≤ vₘₐₓ [11]

Geometrically, this forms a convex polyhedral cone in high-dimensional flux space (with dimensionality equal to the null space of S), where each dimension corresponds to a reaction flux and each point in the cone represents a possible metabolic state [14] [11]. For genome-scale models, this cone can exist in several thousand dimensions [11]. The cone's geometry is fundamentally determined by the network stoichiometry, with edges representing metabolic pathways that are non-decomposable into simpler routes [14].

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts in Metabolic Network Analysis

| Concept | Mathematical Definition | Biological Interpretation | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-State Assumption | S ∙ v = 0 | Metabolic concentrations remain constant as production and consumption fluxes balance | [16] [7] |

| Flux Cone | {v ∈ ℝⁿ : S ∙ v = 0, vᵢ ≤ v ≤ vₘₐₓ} | All thermodynamically feasible flux distributions through the network | [14] [11] |

| Extreme Pathways/Elementary Modes | Convex basis vectors of the flux cone | Non-decomposable metabolic pathways that represent network capabilities | [14] [15] |

| Solution Space | Feasible region defined by stoichiometric and capacity constraints | All possible metabolic states available to the cell under given conditions | [15] [7] |

Methodological Approaches: Analyzing and Reducing Metabolic Solution Spaces

Traditional Methods: From FBA to Extreme Pathway Analysis

Traditional approaches to analyzing metabolic solution spaces fall into two main categories:

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): Applies an optimality principle (e.g., biomass maximization) to identify a single flux distribution from the solution space using linear programming. While computationally efficient, FBA only identifies one extreme point of the solution space and depends critically on the chosen objective function [15] [7].

Extreme Pathway/Elementary Mode Analysis: Identifies a complete set of convex basis vectors that span the entire flux cone, providing a comprehensive mathematical description of all network capabilities. However, these methods suffer from combinatorial explosion in large networks, generating "overwhelmingly large" sets of basis vectors that become computationally intractable for genome-scale models [14] [15].

Advanced Approaches: Navigating High-Dimensional Solution Spaces

Recent methodological advances address the limitations of traditional approaches by providing more manageable characterizations of metabolic solution spaces:

Solution Space Kernel (SSK): This approach identifies a bounded, low-dimensional kernel within the flux solution space that contains the most biologically relevant flux variations. The SSK methodology separates fixed fluxes, identifies unbounded directions (ray vectors), and constructs capping constraints to define a compact polytope representing physically plausible flux ranges [15]. The kernel emphasizes "the realistic range of flux variation allowed in the interconnected biochemical network" and provides an intermediate description between single-point FBA solutions and the intractable proliferation of extreme pathways [15].

Flux Cone Learning (FCL): This machine learning framework uses Monte Carlo sampling of the flux cone to generate training data, then applies supervised learning to correlate geometric changes in the flux cone with phenotypic outcomes. By sampling deletion cones and training predictors on experimental fitness data, FCL can predict gene essentiality and other phenotypes without requiring an optimality assumption [11].

NEXT-FBA: A hybrid approach that uses neural networks trained on exometabolomic data to derive biologically relevant constraints for intracellular fluxes in genome-scale models, improving flux prediction accuracy by relating extracellular measurements to intracellular flux boundaries [12].

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual relationship between these different approaches to solution space analysis:

Figure 1: Methodological landscape for metabolic solution space analysis, showing the relationship between different approaches and their key characteristics.

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Assessment of Solution Space Methods

Performance Comparison Across Methodologies

Recent advances in solution space analysis have been quantitatively evaluated against traditional approaches, with particularly comprehensive assessment in the domain of gene essentiality prediction:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Metabolic Analysis Methods for Gene Essentiality Prediction

| Method | Key Principle | E. coli Accuracy | Key Advantages | Computational Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Biomass maximization via linear programming | 93.5% [11] | Fast computation; Clear biological objective | Objective function dependency; Single-point solution |

| Extreme Pathway Analysis | Complete convex basis of flux cone | Not quantitatively reported | Comprehensive network description | Combinatorial explosion in large networks [15] |

| Solution Space Kernel (SSK) | Bounded low-dimensional flux kernel | Not quantitatively reported | Intermediate complexity; Physical plausibility | Complex computation of bounded faces [15] |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) | Machine learning on flux cone geometry | 95% [11] | No optimality assumption; Best-in-class accuracy | Large training data requirements; Sampling complexity |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

The validation of internal flux predictions employs several key experimental methodologies:

Gene Essentiality Screening: Experimental determination of lethal gene deletions through CRISPR-Cas9 or RNAi screens provides gold-standard data for validating predictive methods like FCL and FBA [11].

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis: Isotopic labeling experiments provide direct measurements of intracellular fluxes for validating NEXT-FBA predictions and other constraint-based modeling approaches [12].

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Computational determination of minimum and maximum possible fluxes for each reaction within model constraints, though this approach has limitations as the "solution space polytope occupies a negligible fraction of the bounding box" in high-dimensional spaces [15].

The experimental workflow for validating flux prediction methods typically follows a structured approach:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for developing and validating flux prediction methods, showing the iterative cycle between computational modeling and experimental validation.

Software and Computational Tools

The experimental and computational analysis of flux cones and solution spaces relies on specialized software tools:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSKernel | Software package | Solution Space Kernel analysis | Characterizes bounded flux kernels; Predicts intervention effects | [15] |

| Fluxer | Web application | Flux visualization | Interactive flux graphs; k-shortest paths; ~1,000 curated models | [17] |

| Pathway Tools/MetaFlux | Software suite | Metabolic reconstruction and FBA | Genome-informed pathway prediction; Flux modeling | [18] |

| COBRApy | Python package | Constraint-based modeling | FBA, FVA, gene deletion studies; Ecosystem integration | [3] |

| ECMpy | Python package | Enzyme-constrained modeling | Adds enzyme capacity constraints to GEMs | [3] |

Critical to effective flux analysis are curated databases containing biochemical information:

- BRENDA Database: Comprehensive enzyme kinetic data, including Kcat values for enzyme-constrained modeling [3].

- EcoCyc/BioCyc: Encyclopedia of E. coli genes and metabolism, providing validated GPR relationships and metabolic pathways [3] [18].

- PAXdb: Protein abundance database used to constrain enzyme allocation in metabolic models [3].

The foundational concepts of flux cones, solution spaces, and steady-state assumptions provide the mathematical framework for understanding and predicting metabolic behavior. Traditional methods like FBA and extreme pathway analysis have established the field but face significant limitations in either oversimplifying the solution space (FBA) or generating computationally intractable descriptions (extreme pathways).

Advanced approaches including the Solution Space Kernel, Flux Cone Learning, and NEXT-FBA represent promising directions for improving the validation of internal flux predictions. These methods provide more nuanced characterizations of metabolic capabilities—SSK by identifying biologically relevant flux ranges, FCL by leveraging machine learning to correlate flux cone geometry with phenotypes, and NEXT-FBA by integrating exometabolomic data to constrain intracellular fluxes.

The continuing development of these methodologies, coupled with standardized experimental validation protocols and accessible research tools, is gradually addressing the fundamental challenge in flux balance analysis research: bridging the gap between computational predictions and biological reality in the complex internal workings of cellular metabolism.

Validating the predictions of metabolic models, especially the internal flux distributions, is a cornerstone of reliable Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) research. FBA is a constraint-based computational method that predicts the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, enabling researchers to simulate organism growth, predict essential genes, and identify potential drug targets [19]. However, the utility of these predictions hinges on the quality and correctness of the underlying metabolic model. Errors in stoichiometry, mass balance, or network connectivity can lead to biologically infeasible flux predictions, such as the generation of energy from nothing, thereby compromising the model's predictive value [20] [1]. This guide objectively compares two foundational toolkits used for model validation and analysis: MEMOTE (MEtabolic MOdel TEsts) and the COBRA (COnstraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) framework. MEMOTE serves primarily as a quality control suite that assesses the structural and semantic integrity of a model [20] [21], while COBRA provides a comprehensive set of functions for simulating phenotypes and validating the model's functional predictions [1] [22]. Together, they form a critical pipeline for ensuring that models are both well-constructed and produce biologically realistic flux predictions.

MEMOTE: The Metabolic Model Test Suite

Core Philosophy and Functionality

MEMOTE is an open-source, community-developed test suite designed to provide standardized quality control for genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) [20] [21]. Its primary goal is to promote model reproducibility, reuse, and collaboration by ensuring that models live up to certain standards and possess minimal functionality [21]. It accepts models encoded in the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML), particularly the level 3 flux balance constraints (SBML3FBC) package, which provides structured descriptions for domain-specific components like flux bounds, gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules, and metabolite annotations [20]. MEMOTE's approach is to run a battery of consensus tests that benchmark a model across several key areas, generating a report that details the model's strengths and weaknesses, often condensed into an overall score [20].

Key Validation Tests and Experimental Protocols

MEMOTE's tests are categorized into annotation, basic structure, biomass, and stoichiometric consistency checks. The table below summarizes the key quantitative tests MEMOTE performs, which are crucial for establishing a model's foundational quality [23] [20].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Validation Tests Performed by MEMOTE

| Test Category | Specific Test | Measurement Principle | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Presence | Reactions, Metabolites, Genes | Counts the number of defined elements in the model [23]. | At least one of each element should be present [23]. |

| Metabolite Quality | Formula & Charge Presence | Checks each metabolite for the presence of a chemical formula and charge information [23]. | All metabolites should have these attributes for mass and charge balance [23]. |

| Gene-Protein-Reaction | GPR Rule Presence | Checks that non-exchange reactions have an associated GPR rule [23]. | All non-exchange reactions should have a GPR rule, with exceptions for spontaneous reactions [23]. |

| Network Properties | Metabolic Coverage | Calculated as the ratio of total reactions to total genes [23]. | A ratio >= 1 indicates a high level of modeling detail [23]. |

| Network Properties | Compartment Presence | Counts the number of distinct compartments defined [23]. | At least two compartments (e.g., cytosol and extracellular environment) [23]. |

| Stoichiometry | Stoichiometric Consistency | Uses linear programming to check if the network can produce energy or cofactors from nothing [20]. | A stoichiometrically consistent model should not contain such cycles [20]. |

The experimental protocol for running MEMOTE is straightforward. After installation via Python's pip package manager, a user can generate a snapshot report for a single model with a single command in the terminal: memote report snapshot path/to/model.xml [24]. This command executes the entire test suite and produces an HTML report (index.html by default) that details the model's performance on all the tests listed above, providing a comprehensive health check [24].

COBRA: Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis

Core Philosophy and Functionality

The COBRA framework provides a wide array of computational methods for analyzing genome-scale metabolic models. While MEMOTE focuses on the model's structure, COBRA tools are designed to simulate and validate the model's function [1] [19]. Implemented in toolboxes like the COBRA Toolbox for MATLAB and cobrapy for Python, these methods use linear programming to find a flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes a biological objective function (e.g., biomass production) under steady-state and capacity constraints [22] [19]. This functionality allows researchers to predict phenotypic outcomes, such as growth rates or metabolite production, under various genetic and environmental conditions, and then to validate these predictions against experimental data [1].

Key Validation Analyses and Experimental Protocols

COBRA provides several specific functions for testing a model's functional capabilities and the reliability of its flux predictions. The following table outlines key validation analyses that can be performed using COBRA tools like cobrapy.

Table 2: Key Functional Validation Analyses in the COBRA Framework

| Analysis Type | Methodology | Key Output | Interpretation for Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | For each reaction, computes the minimum and maximum possible flux while maintaining optimal objective value (e.g., maximal growth) [22]. | Minimum and maximum flux for each reaction. | Identifies reactions with no flexibility (essential reactions) and validates if fixed constraints are realistic [22]. |

| Gene/Reaction Deletion | Systematically knocks out single or pairs of genes/reactions and simulates the resulting growth phenotype [22]. | Growth rate for each knockout strain. | Validates model against experimental knockout data; essential genes/reactions should predict zero growth [22]. |

| Robustness Analysis | Varies the bound of a single reaction (e.g., a substrate uptake rate) and observes the effect on the objective function [19]. | Objective value (e.g., growth rate) as a function of reaction flux. | Determines the sensitivity of growth to nutrient availability and identifies optimal yields [19]. |

| Loopless FBA | Adds thermodynamic constraints to the FBA problem to eliminate thermodynamically infeasible cyclic flux loops [22]. | A flux distribution devoid of internal cycles. | Ensures that flux predictions are not skewed by metabolically impossible energy generation [22]. |

| Find Blocked Reactions | Identifies reactions that cannot carry any flux under the given constraints [22]. | A list of reactions with zero flux. | Highlights gaps in the network or reactions that require specific conditions to be active [22]. |

The protocol for performing a single gene deletion analysis in cobrapy, for example, involves using the single_gene_deletion function. This function takes the model and a list of genes as input. It then simulates the knockout of each gene and returns a DataFrame containing the predicted growth rate and solution status for each deletion [22]. The results can be compared to experimental gene essentiality data to validate the model's predictive accuracy for internal flux essentiality.

The Integrated Validation Workflow: MEMOTE and COBRA in Practice

MEMOTE and COBRA are not mutually exclusive but are profoundly complementary. They should be used in a sequential workflow to ensure a model is both structurally sound and functionally predictive. The following diagram illustrates this integrated validation pipeline.

Figure 1: The Integrated Model Validation Workflow Combining MEMOTE and COBRA

As shown in Figure 1, the process begins with a structural assessment using MEMOTE. Researchers run the test suite to identify and fix fundamental issues, such as missing metabolite formulas, charge imbalances, or incorrect stoichiometries [23] [20]. Once the model passes these basic quality checks, it proceeds to the functional validation stage with COBRA. Here, the model's dynamic predictions—such as growth capabilities on different substrates or the outcome of gene knockouts—are simulated and compared against experimental data [1]. A significant discrepancy between predictions and data at this stage necessitates iterative refinement of the model (e.g., through gap-filling algorithms [22]), after which the model should be re-checked with MEMOTE to ensure the new changes did not introduce structural errors. This cycle continues until the model achieves satisfactory predictive performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table details the key software tools and resources essential for performing robust model validation with MEMOTE and COBRA.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions for Model Validation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| MEMOTE Software | Python Software Package | Runs a standardized suite of tests to generate a quality report on model structure and annotation [21] [24]. |

| COBRApy | Python Library | Provides functions for simulating, analyzing, and validating model phenotypes (FBA, FVA, gene deletion, etc.) [22]. |

| SBML Model File | Data Format | The standardized model file format (SBML3FBC) that serves as the input for both MEMOTE and COBRApy [20]. |

| Git / GitHub | Version Control System | Tracks incremental changes to the model during reconstruction and validation, enabling collaboration and reproducibility [21]. |

| Continuous Integration (e.g., Travis CI) | Software Service | Automatically runs MEMOTE tests whenever the model is updated in the repository, ensuring continuous quality assurance [21]. |

| Experimental Growth/Knockout Data | Empirical Dataset | Serves as the ground-truth benchmark against which COBRA-based phenotypic predictions are validated [1]. |

The validation of internal flux predictions in FBA research is a multi-layered process that requires rigorous checks of both model structure and function. MEMOTE and the COBRA framework serve distinct yet deeply interconnected roles in this process. MEMOTE acts as a foundational quality gatekeeper, ensuring the model is stoichiometrically sound, well-annotated, and free from basic formal errors. Subsequently, COBRA provides the analytical machinery to stress-test the model's phenotypic predictions against empirical evidence. An objective comparison reveals that neither tool is a substitute for the other; rather, they are sequential and complementary. The most robust validation strategy employs MEMOTE to build a structurally solid model and then leverages COBRA's simulation power to refine and validate the model's predictive accuracy for internal fluxes. Adopting this integrated workflow, supported by version control and continuous integration, is paramount for developing metabolic models that are not only computationally functional but also biologically trustworthy.

Advanced Frameworks and Techniques for Robust Flux Validation

Quantitatively predicting intracellular metabolic fluxes is a fundamental goal in systems biology and metabolic engineering. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a widely used constraint-based modeling approach that predicts flux distributions in genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) [25]. However, a significant challenge in FBA research is validating the accuracy of its internal flux predictions, which are inherently dependent on the selected biological objective function [4] [26]. Without experimental validation, FBA predictions remain theoretical. 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as the gold-standard experimental method for quantifying in vivo metabolic fluxes, providing a rigorous benchmark for validating and constraining FBA models [25] [27] [28]. The integration of 13C-MFA with multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics) represents a powerful frontier for enhancing the predictive accuracy of genome-scale models. This guide objectively compares current methodologies that leverage these data types, providing experimental protocols and performance comparisons to inform research practices in drug development and biotechnology.

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis: The Experimental Benchmark

13C-MFA is a model-based approach that quantifies intracellular metabolic fluxes by integrating data from isotopic tracer experiments [27]. When cells are cultured with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose), the label is distributed through metabolic pathways in a flux-dependent manner [27]. The measured mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of metabolites, typically obtained via mass spectrometry (GC-MS, LC-MS) or NMR, are then used to compute the most statistically probable flux map [29] [27]. The core of 13C-MFA is a least-squares parameter estimation problem, where fluxes are estimated by minimizing the difference between measured and simulated labeling data [27]. For a network at metabolic steady-state, the sum of fluxes producing a metabolite must equal the sum of fluxes consuming it, forming the stoichiometric constraints that underlie the flux calculation [25].

A Workflow for Data Integration and Model Validation

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for integrating experimental data to constrain and validate metabolic model predictions, a process central to the methods discussed in this guide.

Comparative Analysis of Integration Approaches

Different computational strategies have been developed to integrate 13C-MFA and omics data, each with distinct strengths and performance characteristics. The table below summarizes the core methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Data Integration Methodologies for Metabolic Flux Prediction

| Method | Core Approach | Data Types Integrated | Primary Use Case | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p13CMFA [26] | Parsimonious flux minimization within the 13C-MFA solution space. | 13C labeling data, optionally transcriptomics (as weights). | Refining 13C-MFA solutions in large networks or with limited measurements. | Selects biologically relevant fluxes; integrates gene expression to weight minimization. |

| MINN (Metabolic-Informed Neural Network) [30] | Hybrid neural network embedding GEMs as mechanistic layers. | Multi-omics (transcriptomics, proteomics), GEM structure. | Predicting metabolic fluxes under genetic/ environmental perturbations. | Outperformed pFBA and Random Forest on E. coli KO dataset; handles trade-off between constraints and accuracy. |

| Omics-based ML (Machine Learning) [5] | Supervised machine learning models trained on omics data. | Transcriptomics, proteomics. | Predicting internal and external metabolic fluxes across conditions. | Showed smaller prediction errors for internal/external fluxes compared to standard pFBA. |

| TIObjFind [4] | Optimization framework combining FBA and Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA). | Experimental flux data (e.g., from 13C-MFA), network topology. | Identifying context-specific metabolic objective functions for FBA. | Quantifies reaction importance (Coefficients of Importance); improves interpretability and aligns predictions with data. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for 13C-MFA to Generate Validation Data

13C-MFA is considered the most reliable method for generating experimental flux maps to validate FBA predictions [27] [28]. The following protocol details the key steps for generating a 13C-MFA flux map for mammalian cells, such as cancer cell lines.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for 13C-MFA

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracer | A substrate with one or more carbon atoms replaced with 13C. | [1,2-13C]Glucose to trace glycolytic and TCA cycle fluxes [27]. |

| Cell Culture Medium | Chemically defined medium without unlabeled carbon sources that interfere with tracing. | DMEM without glucose, glutamine, or pyruvate, supplemented with dialyzed serum [27]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Instrument to measure the Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) of metabolites. | GC-MS or LC-MS for measuring labeling in proteinogenic amino acids or intracellular metabolites [29] [27]. |

| 13C-MFA Software | Computational tool to estimate fluxes from labeling data and external rates. | INCA, Metran, mfapy, or Iso2Flux [27] [26] [31]. |

Experimental Design and Cell Culture:

- Select an appropriate tracer. For central carbon metabolism, [1,2-13C]glucose or [U-13C]glutamine are common choices [27].

- Culture cells in a medium where the tracer is the sole or primary carbon source. Ensure cells are at metabolic steady-state (exponential growth) throughout the labeling period [28].

- Harvest cells and medium during mid-exponential growth. A typical labeling duration is the time required for 2-3 cell doublings to ensure isotopic steady-state [27].

Measurement of External Fluxes:

- Growth Rate: Calculate the specific growth rate (µ, 1/h) from cell counts over time using: ( \mu = \frac{\ln(N{x,t2}) - \ln(N{x,t1})}{\Delta t} ) where ( N_x ) is the cell count [27].

- Nutrient Uptake and Product Secretion: Measure metabolite concentrations (e.g., glucose, glutamine, lactate, ammonia) in the medium at multiple time points. Calculate external fluxes (ri, nmol/10^6 cells/h) for exponentially growing cells using: ( ri = 1000 \cdot \frac{\mu \cdot V \cdot \Delta Ci}{\Delta Nx} ) where ( \Delta Ci ) is the concentration change and V is culture volume [27]. Correct for glutamine degradation in control experiments without cells [27].

Measurement of Isotopic Labeling:

- Quench metabolism rapidly (e.g., cold methanol).

- Extract intracellular metabolites.

- Derivatize metabolites if required for analysis (e.g., for GC-MS).

- Measure mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) using GC-MS or LC-MS. Report raw, uncorrected MIDs for reproducibility [28].

Computational Flux Estimation:

- Model Definition: Use a stoichiometric model of central carbon metabolism including atom transitions for each reaction [28].

- Flux Fitting: Input the measured external fluxes and MIDs into 13C-MFA software. Estimate fluxes by minimizing the residual sum of squares (RSS) between measured and simulated labeling data [27] [31].

- Statistical Validation: Perform a χ²-test for goodness-of-fit to validate the model [25]. Calculate confidence intervals for all estimated fluxes (e.g., via Monte Carlo sampling) [28].

Protocol for Integrating Omics Data via Parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA)

The p13CMFA method is an extension of traditional 13C-MFA that is particularly useful when the solution space is large [26].

- Perform Standard 13C-MFA: Conduct the experiment and flux estimation as described in Section 4.1. This identifies the set of all flux distributions that are statistically consistent with the 13C labeling data.

- Secondary Optimization: From the set of valid solutions, select the flux distribution that minimizes the total overall flux (a parsimony objective) [26]. This is formulated as a second optimization problem solved after the initial 13C-MFA fit.

- Optional Integration of Transcriptomics: The parsimony objective can be weighted by gene expression data. In this approach, the flux through a reaction catalyzed by a lowly expressed enzyme is penalized more heavily during minimization, ensuring the selected solution is both metabolically and transcriptionally parsimonious [26].

- Validation: The final p13CMFA solution should still be checked for goodness-of-fit to ensure it explains the original 13C labeling data within acceptable statistical limits [25] [26].

Performance and Validation Metrics

Robust statistical assessment is critical for evaluating the success of any data integration strategy. The following table outlines key metrics and their interpretation.

Table 3: Key Metrics for Validating Integrated Flux Predictions

| Metric | Description | Interpretation and Target |

|---|---|---|

| Goodness-of-fit (χ²-test) [25] [28] | Tests if the difference between measured and model-simulated labeling data is statistically significant. | A p-value > 0.05 indicates the model fits the data adequately. A low p-value suggests an invalid model or poor-quality data. |

| Flux Confidence Intervals [25] [28] | The range of possible values for a flux, calculated at a specific confidence level (e.g., 95%). | Narrow intervals indicate the flux is well-resolved by the data. Wide intervals suggest more data is needed. |

| Sum of Squared Residuals (SSR) [27] [26] | The total squared difference between measured and simulated data points. | Used as the objective for flux fitting. A lower SSR indicates a better fit. The absolute value is evaluated via the χ²-test. |

| Comparison with 13C-MFA Benchmark [25] | Calculates the error (e.g., Mean Absolute Error) between predicted fluxes and 13C-MFA measured fluxes. | A lower error indicates higher predictive accuracy. This is the most direct validation for FBA predictions. |

Integrating experimental data is no longer optional for rigorous metabolic flux prediction in FBA research. As the comparisons and protocols in this guide demonstrate, 13C-MFA provides an essential experimental benchmark for validating internal flux predictions, while omics data offer powerful constraints to refine models and improve their biological fidelity. The choice of integration method depends on the research goal: p13CMFA is ideal for refining 13C-MFA solutions with transcriptomics, hybrid models like MINN leverage deep learning for complex genotype-phenotype predictions, and frameworks like TIObjFind help uncover the fundamental objectives driving cellular metabolism. By adopting these validated practices and robust statistical reporting, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of metabolic models, accelerating progress in drug development and metabolic engineering.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has served as the gold standard for predicting metabolic phenotypes, operating by combining genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) with an optimality principle to predict flux distributions [32]. This mechanism-based approach simulates metabolism at steady-state and has been particularly effective at predicting gene essentiality in microbes. However, a significant validation challenge exists: FBA's predictive power substantially decreases when applied to higher-order organisms where the optimality objective is unknown or nonexistent [11]. This limitation has prompted the development of new methods that can better validate internal flux predictions against experimental data.

Flux Cone Learning (FCL) represents a novel framework designed to address these validation challenges. Introduced by Merzbacher et al. in 2025, FCL is a general machine learning framework that predicts the effects of metabolic gene deletions on cellular phenotypes by identifying correlations between the geometry of the metabolic space and experimental fitness scores from deletion screens [11] [33]. Unlike traditional FBA, FCL does not require encoding cellular objectives as an optimization task, making it applicable to a broader range of organisms and phenotypes where optimality assumptions may not hold [33]. This approach leverages mechanistic information encoded in GEMs but uses Monte Carlo sampling and supervised learning to build predictive models that can be validated against experimental fitness data, thereby providing a more robust validation framework for internal flux predictions in metabolic research.

Theoretical Foundation and Methodological Framework

Core Components of Flux Cone Learning

The FCL framework rests on four fundamental components that work in sequence to generate predictive models of phenotypic outcomes. First, a Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) provides the mechanistic foundation, defined by the stoichiometric equation Sv = 0 and flux bounds Vi^min ≤ vi ≤ V_i^max that constrain reaction rates [11]. This GEM defines a convex polytope in high-dimensional space known as the flux cone of an organism. Second, a Monte Carlo sampler generates numerous random flux samples within this cone, capturing its geometric properties. Third, a supervised learning algorithm trains on these flux samples alongside experimentally measured phenotypic fitness labels. Finally, a score aggregation step employs majority voting to generate deletion-wise predictions from sample-wise classifications [11].

The mathematical innovation of FCL lies in its treatment of gene deletions as perturbations to the shape of the flux cone. When a gene is deleted, the gene-protein-reaction (GPR) map determines which flux bounds must be set to zero in the GEM, thereby altering the boundaries of the polytope [11]. FCL leverages the correlation between these geometric changes and phenotypic outcomes, which can be learned through supervised algorithms without presupposing cellular objectives. This contrasts sharply with FBA, which depends on predefined optimization goals (typically biomass maximization) that may not accurately reflect cellular behavior in all contexts, particularly in higher organisms [11].

Workflow Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of Flux Cone Learning, from metabolic model preparation to phenotypic prediction:

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Benchmarking Experimental Design

To validate FCL's predictive performance, Merzbacher et al. designed comprehensive experiments comparing FCL against FBA for metabolic gene essentiality prediction across organisms of varying complexity [11]. The experimental protocol began with the iML1515 model of Escherichia coli, which represents the best-curated GEM in the literature, thereby minimizing the potential confounder of model quality [11]. Researchers employed FCL with N = 1202 gene deletions (80% of the total) for training a binary classifier of gene essentiality, with q = 100 samples per flux cone for training. Critically, the biomass reaction was intentionally removed from training data to prevent the model from learning the correlation between biomass and essentiality that underpins FBA predictions [11].

The training dataset comprised N = 120,285 samples and n = 2,712 features (reactions). The researchers selected a random forest classifier as an optimal balance between model complexity and interpretability. Testing was performed on a randomly selected hold-out set of N = 300 genes (20% of the total) across multiple training repeats to ensure statistical robustness [11]. This experimental design enabled direct comparison with state-of-the-art FBA predictions, which achieve maximal accuracy of 93.5% correctly predicted genes for E. coli growing aerobically in glucose with biomass synthesis as the optimization objective [11].

Extended Organism Validation

To demonstrate broad applicability beyond E. coli, the researchers extended validation experiments to additional organisms of varied complexity, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells [11]. This multi-organism approach tested FCL's performance across different biological systems and GEM qualities. For each organism, researchers gathered existing experimental fitness data from deletion screens, which served as ground truth labels for training and validation. The consistent application of FCL across diverse biological systems highlighted its versatility compared to organism-specific optimization objectives required by FBA [11].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Gene Essentiality Prediction Accuracy

Flux Cone Learning demonstrates superior performance compared to traditional Flux Balance Analysis across multiple organisms and evaluation metrics. The following table summarizes the quantitative performance comparison between FCL and FBA for metabolic gene essentiality prediction:

Table 1: Performance comparison of FCL versus FBA for gene essentiality prediction

| Organism | Method | Overall Accuracy | Nonessential Gene Prediction | Essential Gene Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | FBA | 93.5% | Baseline | Baseline |

| Escherichia coli | FCL | 95.0% | +1% improvement | +6% improvement |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | FBA | Not Reported | Lower than FCL | Lower than FCL |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | FCL | Best-in-class | Superior to FBA | Superior to FBA |

| Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) Cells | FBA | Limited efficacy | Limited efficacy | Limited efficacy |

| Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) Cells | FCL | Best-in-class | Superior to FBA | Superior to FBA |

The experimental results from E. coli demonstrate that FCL achieves an average of 95% accuracy for all test genes across training repeats, outperforming FBA's 93.5% accuracy [11]. More notably, FCL shows particular strength in identifying essential genes, with a 6% improvement over FBA, while also achieving a 1% improvement for nonessential genes [11]. This enhanced performance for essential gene detection is particularly valuable for biomedical applications such as identifying lethal deletions for cancer therapy development or antimicrobial treatments that avoid drug resistance [11].

Performance Under Suboptimal Conditions

Further experiments investigated FCL's robustness under various challenging conditions. When trained with sparser sampling data and fewer gene deletions, FCL's predictive accuracy decreased but remained competitive – models trained with as few as 10 samples per flux cone already matched state-of-the-art FBA accuracy [11]. Additionally, when retrained with earlier and less complete GEMs for E. coli, only the smallest GEM (iJR904) showed a statistically significant performance drop [11]. This demonstrates FCL's resilience to variations in model quality and data completeness.

Surprisingly, feature reduction via Principal Component Analysis consistently resulted in lower accuracy across all tested cases, suggesting that correlations between essentiality and subtle changes in flux cone geometry require high-dimensional feature spaces to capture effectively [11]. The researchers also explored deep learning models, including feedforward and convolutional neural networks, but these did not improve performance even with larger training datasets (q > 5000 samples/cone), likely because flux samples are linearly correlated through the stoichiometric constraint [11].

Implementation and Research Applications

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing Flux Cone Learning requires specific computational tools and data resources. The following table outlines essential research reagents for FCL implementation:

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for FCL implementation

| Research Reagent | Function in FCL Workflow | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | Provides mechanistic metabolic network structure | Organism-specific curation quality significantly impacts predictions |

| Monte Carlo Sampler | Generates random flux distributions within metabolic space | Must efficiently handle high-dimensional constraints |

| Experimental Fitness Data | Serves as labeled training data | Can include gene essentiality screens or molecule production data |

| Random Forest Classifier | Supervised learning algorithm for prediction | Provides balance between performance and interpretability |

| High-Performance Computing Resources | Handles computational intensity of sampling and training | Dataset with 1502 deletions × 100 samples reaches ~3GB size |

Versatility Beyond Gene Essentiality

The FCL framework demonstrates remarkable versatility for diverse prediction tasks beyond gene essentiality. Researchers successfully trained an FCL predictor of small molecule production using data from a large deletion screen, showcasing its applicability to biotechnological optimization [11]. This flexibility stems from FCL's ability to correlate flux cone geometry with any metabolic phenotype, provided that fitness scores correlate with metabolic activity [11]. This includes both metabolic signals already encoded in GEMs (growth rate, pathway activity) and non-metabolic readouts absent from the model but associated with metabolic activity.

The methodology also supports the development of metabolic foundation models across diverse species. In proof-of-concept experiments, researchers trained a variational autoencoder on Monte Carlo samples from five metabolically diverse pathogens, resulting in well-separated low-dimensional representations of each species' flux cone despite using only reactions shared across all species [11]. This suggests FCL's potential for building generalizable metabolic models across the tree of life.

Comparative Workflow Analysis

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual differences between traditional FBA and the FCL approach, highlighting how FCL integrates machine learning with mechanistic modeling:

Flux Cone Learning represents a significant advancement in metabolic phenotype prediction, consistently outperforming traditional FBA across organisms of varying complexity while eliminating the need for potentially problematic optimality assumptions. By integrating Monte Carlo sampling of mechanistic models with supervised machine learning trained on experimental data, FCL achieves best-in-class accuracy for metabolic gene essentiality prediction and demonstrates versatility for diverse applications including small molecule production prediction. For researchers and drug development professionals, FCL offers a robust validation framework for internal flux predictions, particularly valuable for higher organisms where FBA's optimality principles falter. As the field moves toward metabolic foundation models spanning diverse species, FCL provides a principled framework for leveraging existing screening data to build predictive models that more accurately reflect biological reality.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has established itself as a cornerstone of constraint-based metabolic modeling, enabling researchers to predict organism phenotypes from genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). However, a critical challenge persists in the field: the accurate prediction and validation of intracellular metabolic fluxes. The inherent underdetermination of metabolic networks, combined with the scarcity of reliable experimental data to constrain these models, often limits the biological relevance of flux predictions [12] [1]. This validation gap is particularly problematic for applications in drug development and metabolic engineering, where inaccurate flux predictions can lead to costly experimental dead-ends.